Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mediumnic Lights, X Rays, and The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

Mediumnic Lights, X Rays, and The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

Uploaded by

Juliana BoldrinCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Mass and Heat Transfer Analysis of Mass Cont Actors and Heat Ex Changers (Cambridge Series in Chemical Engineering)Document405 pagesMass and Heat Transfer Analysis of Mass Cont Actors and Heat Ex Changers (Cambridge Series in Chemical Engineering)Kaliyaram Viswambaram100% (1)

- Thinking With A FeministDocument27 pagesThinking With A FeministJuliana BoldrinNo ratings yet

- Sensing The Airs The Cultural Context For Breathing and Breathlessness in UruguayDocument17 pagesSensing The Airs The Cultural Context For Breathing and Breathlessness in UruguayJuliana BoldrinNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Perspectives On Breath Body andDocument27 pagesInterdisciplinary Perspectives On Breath Body andJuliana BoldrinNo ratings yet

- Breathing SpacesDocument24 pagesBreathing SpacesJuliana BoldrinNo ratings yet

- 1st and Scond Kalma SharifDocument20 pages1st and Scond Kalma SharifQamarManzoorNo ratings yet

- Read Aloud I Am GoldenDocument4 pagesRead Aloud I Am Goldenapi-605538818No ratings yet

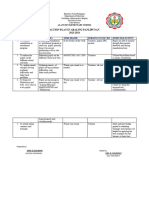

- Action Plan in ARALING PANLIPUNANDocument2 pagesAction Plan in ARALING PANLIPUNANgina.guliman100% (1)

- PSQT Assignment-IDocument1 pagePSQT Assignment-IJhanuNo ratings yet

- Trichomonas - WikipediaDocument9 pagesTrichomonas - WikipediaMuhammad AminNo ratings yet

- 1 Vkip 113Document595 pages1 Vkip 113flopo72No ratings yet

- Under World Religions PDFDocument31 pagesUnder World Religions PDFSwami GurunandNo ratings yet

- Ranjan Bose Information Theory Coding and Cryptography Solution ManualDocument61 pagesRanjan Bose Information Theory Coding and Cryptography Solution ManualANURAG CHAKRABORTY89% (38)

- 2020 A New Frontier in Pelvic Fracture Pain Control in The ED Successful Use of The Pericapsular Nerve Group (PENG) BlockDocument5 pages2020 A New Frontier in Pelvic Fracture Pain Control in The ED Successful Use of The Pericapsular Nerve Group (PENG) Block林煒No ratings yet

- Chapter 10 - Engineers As Managers/Leaders: Dr. C. M. ChangDocument54 pagesChapter 10 - Engineers As Managers/Leaders: Dr. C. M. Changbawardia100% (2)

- Romeo and Juliet (Death Scene - Last Scene) : Modern EnglishDocument6 pagesRomeo and Juliet (Death Scene - Last Scene) : Modern EnglishAnn AeriNo ratings yet

- Višegrad Genocide, What Is?Document1 pageVišegrad Genocide, What Is?Visegrad GenocideNo ratings yet

- Monte Carlo MethodDocument23 pagesMonte Carlo MethodCHINGZU212No ratings yet

- Worksheet: Dihybrid CrossesDocument4 pagesWorksheet: Dihybrid CrossesLovie AlfonsoNo ratings yet

- Report Card Grade11-2018-2019Document7 pagesReport Card Grade11-2018-2019Whilmark Tican MucaNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law I Cases (Long Full Text)Document186 pagesCriminal Law I Cases (Long Full Text)afro99No ratings yet

- Gaugler W - Manuel de Escrime 1908Document14 pagesGaugler W - Manuel de Escrime 1908bunzlauNo ratings yet

- Life Insurance Fraud and Its PreventionDocument16 pagesLife Insurance Fraud and Its PreventionswetaNo ratings yet

- Science Subject For Elementary 2nd Grade BiologyDocument55 pagesScience Subject For Elementary 2nd Grade BiologyClaudia Sari BerlianNo ratings yet

- Rubric For Informative Writing 6-11 (Pearson MyPerspectives)Document1 pageRubric For Informative Writing 6-11 (Pearson MyPerspectives)Junaid GNo ratings yet

- Presente Progresivo o Continuo (Inglés)Document6 pagesPresente Progresivo o Continuo (Inglés)GerarNo ratings yet

- Iwe Awon AlujonnuDocument84 pagesIwe Awon AlujonnuRaphael AsegunNo ratings yet

- Growth of Indian NewspapersDocument14 pagesGrowth of Indian NewspapersDilara Afroj RipaNo ratings yet

- Atisha WarriorDocument3 pagesAtisha WarriortantravidyaNo ratings yet

- Physical Education 8 ModulesDocument4 pagesPhysical Education 8 ModulesWizza Mae L. Coralat50% (2)

- Group 9 - Dental FluorosisDocument37 pagesGroup 9 - Dental Fluorosis2050586No ratings yet

- 2 Faktor-Faktor-Yang-Berhubungan-Dengan-TiDocument9 pages2 Faktor-Faktor-Yang-Berhubungan-Dengan-TiofislinNo ratings yet

- Essay Topics For IliadDocument14 pagesEssay Topics For IliadJennifer Garcia EreseNo ratings yet

- Waldorf Schools: Jack PetrashDocument17 pagesWaldorf Schools: Jack PetrashmarselyagNo ratings yet

Mediumnic Lights, X Rays, and The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

Mediumnic Lights, X Rays, and The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

Uploaded by

Juliana BoldrinOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mediumnic Lights, X Rays, and The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

Mediumnic Lights, X Rays, and The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

Uploaded by

Juliana BoldrinCopyright:

Available Formats

Mediumnic Lights, Xx Rays, and the Spirit Who

Photographed Herself

Jeremy Stolow

In Paris, starting in March 1909, Julien Ochorowicz, codirector of the

Institut Général Psychologique de Paris, organized a series of séances to

be conducted with Stanislava Tomczyk, a medium whom Ochorowicz

had “discovered” in Poland and had brought to Paris for further study.

Tomczyk had already gained a reputation for her telekinetic abilities to

levitate small objects, to stop the movement of clocks, and to influence

the outcome of a spinning roulette wheel, among other powers. The me-

dium’s abilities were attributed to Little Stasia, a control spirit who com-

municated with and through Tomczyk by means of alphabetic rapping,

automatic writing, and direct speech during the medium’s somnambu-

lant states. Tomczyk was hardly the first spirit medium to attract both

scientific attention and public curiosity; by the time of Tomczyk’s arrival

in France, psychic and occult phenomena had been firmly established as

objects of legitimate scientific investigation, endorsed by such luminaries

as the astronomer Camille Flammarion, the Nobel Prize-winning physiol-

ogist Charles Richet, and his fellow Nobel laureates Marie and Paul Curie.1

Research for this paper was conducted with the financial support of the Social Sciences and

Humanities Research Council of Canada. I also wish to thank Linda Henderson, Robert Brain,

Ghislain Thibault, Maria José de Abreu, and especially Bernard Geoghegan for their incisive

comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Unless otherwise noted, all translations into English

are my own.

1. Even better known than Tomczyk were the spirit mediums Eusapia Palladino, Eva

Carrière, and Mme. D’Esperance (née Elizabeth Hope), each the subject of extended study in

France and elsewhere during this formative period of psychic research. On the development

of psychic research and its relationship with spiritualism and the occult, see Ian Hacking,

Critical Inquiry 42 (Summer 2016)

© 2016 by The University of Chicago. 00093-1896/16/4204-0011$10.00. All rights reserved.

923

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

924 Jeremy Stolow / The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

Ochorowicz’s study of Tomczyk would have merited little more than a

few lines in the annals of psychic research had it not been for a dramatic

turning point occurring on 29 March. On that evening, after a series of

unsuccessful séances that had led Ochorowicz to despair of convincing

his scientific peers of the authenticity of Tomczyk’s powers, the medium

announced to Ochorowicz that Little Stasia wished to speak to him. As

she communicated by rapping the alphabet, the following conversation

ensued: “ ‘I wish to photograph myself,’ Little Stasia announced. ‘Prepare the

instruments.’ Both of us [Ochorowicz and Tomcyzk] laughed, believing

this to be another of Little Stasia’s farces. ‘Should we also set up a magne-

sium lamp?’ ‘I don’t need any magnesium.’ ‘And where should the medium

be placed?’ ‘I don’t need her either.’ ” Little Stasia further explained how

the photographic session should be organized: “ ‘Place a camera using a

9x12cm plate on the table near the window. Fix the focus at a half-meter

distance and place a chair at that point. And give me something to cover my-

self. ’ ” Ochorowicz followed Little Stasia’s instructions, and then inquired,

“ ‘What next needs to be done?’ ‘Nothing,’ replied Little Stasia. ‘Please leave

now and close the door.’ ” Having ensured that the room was completely

obscured from external light sources, Ochorowicz opened the shutter of

the camera, and both he and the medium departed. After roughly one

hour, Little Stasia announced through the medium: “ ‘It’s done. You can

develop the plate.’ ” 2

This is the photograph Ochorowicz developed, after what he describes

as an inordinately long immersion in the developing bath (fig. 1). The

“Telepathy: Origins of Randomization in Experimental Design,” Isis 79 (Sept. 1988): 427–51;

Sophie Lachapelle, Investigating the Supernatural: From Spiritism and Occultism to Psychical

Research and Metaphysics in France, 1853–1931 (Baltimore, 2011); Roger Luckhurst, The Invention

of Telepathy, 1870–1901 (Oxford, 2002); John Warne Monroe, Laboratories of Faith: Mesmerism,

Spiritism, and Occultism in Modern France (Ithaca, N.Y., 2008); and Janet Oppenheim, The

Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850–1914 (Cambridge, 1985).

2. Julien Ochorowicz, “Les Phénomènes lumineux et la photographie de l’invisible,”

Annales des Sciences Psychiques 19 (July 1909): 194–95; hereafter abbreviated “PL.” This article

ran from July through November.

J eremy S tolow is an associate professor in communication studies at

Concordia University (Montreal). His principal area of research is religion

and technology. His current project, “Picturing Aura,” investigates the history

of efforts to photograph the human aura and the lives of such images among

psychic researchers, occultists, artists, and New Age health practitioners. Among

his publications are Orthodox by Design: Judaism, Print Politics, and the ArtScroll

Revolution (2010) and Deus in Machina: Religion, Technology, and the Things in

Between (2013).

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

FIGURE 1 . Self-Portrait of Little Stasia. Reproduction courtesy of Harvard University

Library.

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

926 Jeremy Stolow / The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

picture was submitted to the Annales des Sciences Psychiques, the leading

French-language periodical for psychic research, where it was published

in July 1909 alongside Ochorowicz’s report.3 Its publication caused quite

a sensation among psychic researchers, generating heated debate about

the authenticity of the photograph, the plausibility of Ochorowicz’s ac-

count of its provenance, and, more broadly, the limits of possibility for

photographic instruments when it came to the visualization of normally

invisible entities, such as spirits.4 Spirit photography was itself nothing

new to psychic researchers and their reading publics; its practice dated

back to the mid-nineteenth century, pioneered by studio photographers

such as William Mumler (in the US) and Edouard Isidore Buguet (in

France).5 But this spiritual self-portrait seemed quite novel and pointed

3. See ibid., pp. 193–201. On the role of the Annales as a key forum of reportage and

debate over the science of psychic research, see Lachapelle, Investigating the Supernatural,

pp. 86–91, and Carlos Alvarado and Renaud Evrard, “The Psychic Sciences in France: Historical

Notes on the Annales des Sciences Psychiques,” Journal of Scientific Exploration 26, no. 1 (2012):

117–40. France was not the only country where psychic research was reported and discussed,

both in professional journals and in nonexpert fora, including the many fin-de-siècle occult

publications in which news about advances in psychic research was frequently reproduced. See,

for instance, the insightful discussion of the history and influence of the German periodical

Psychische Studien on Adrian Sommer’s blog “Forbidden Histories,” forbiddenhistories

.wordpress.com/2013/12/17/spirits-science-and-the-mind-the-journal-psychische-studien-1874

-1925/. For an instructive study of the role of occult periodicals within the English-speaking

world, see Mark S. Morrisson, “The Periodical Culture of the Occult Revival: Esoteric Wisdom,

Modernity, and Counter-Public Spheres,” Journal of Modern Literature 31 (Winter 2008): 1–22.

4. One of Ochorowicz’s sharpest critics was Guillaume de Fontenay, a photographic

authority otherwise known to be sympathetic to psychic research. See Guillaume de Fontenay,

“Le Portrait de Stasia: Quelques reflexions photographiques,” Annales des Sciences Psychiques 19

(Sept. 1909): 267–75. For Ochorowicz’s reply, see Ochorowicz, “Une Réponse du Dr. Ochorowicz

aux critiques de M. de Fontenay sur la photographie de la petite Stasia,” Annales des Sciences

Psychiques 19 (Nov. 1909): 339–41. A detailed account of the public debate between Fontenay and

Ochorowicz as regards the meaning and authenticity of Ochorowicz’s photographs is found

in Rolf H. Krauss, Beyond Light and Shadow: The Role of Photography in Certain Paranormal

Phenomena—An Historical Survey (Munich, 1995), pp. 74–90.

5. On spirit photography in the nineteenth century, see The Perfect Medium: Photography

and the Occult, ed. Clément Chéroux et al. (exhibition catalog, Metropolitan Museum of Art,

N.Y., 26 Sept.–31 Dec. 2005); Tom Gunning, “Phantom Images and Modern Manifestations:

Spirit Photography, Magic Theater, Trick Films, and Photography’s Uncanny,” in Fugitive Images:

From Photography to Video, ed. Patrice Petro (Bloomington, Ind., 1995), pp. 42–71 and “Uncanny

Reflections, Modern Illusions: Sighting the Modern Optical Uncanny,” in Uncanny Modernity:

Cultural Theories, Modern Anxieties, ed. Jo Collins and John Jervis (London, 2008), pp. 68–90;

John Harvey, Photography and Spirit (London, 2007); Louis Kaplan, The Strange Case of William

Mumler, Spirit Photographer (Minneapolis, 2008); John Warne Monroe, “Cartes de visite from

the Other World: Spiritism and the Discourse of Laïcisme in the Early Third Republic,” French

Historical Studies 26 (Winter 2003): 119–53; and Sarah Willburn, “Viewing History and Fantasy

through Victorian Spirit Photography,” in The Ashgate Research Companion to Nineteenth-

Century Spiritualism and the Occult, ed. Tatiana Kontou and Sarah Willburn (Surrey, 2012),

pp. 359–81.

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Critical Inquiry / Summer 2016 927

to an entirely distinct order of things—one at odds with many reigning

assumptions about agency, materiality, and visual representation. Indeed,

how, precisely, could Little Stasia, an immaterial creature, interact with

the camera in order to photograph herself ? What was the source of energy

that had opened and shut the camera’s shutter without the aid of a human

hand? And what could have been the source of light that had enabled the

image to be registered on the photosensitive plate? Were all these forces

somehow connected with one another?

Such questions were at the heart of debates surrounding Little Stasia’s

photograph and the subsequent investigations Ochorowicz conducted.

But these questions also signal the relevance of this episode for much larger

and ongoing concerns about visual representation, the mediating power

of instruments, and the “reality” we ascribe to phenomena that exceed

both ordinary perception and ordained scientific postulates. As I hope to

demonstrate in the coming pages using the example of Ochorowicz’s pho-

tography, psychic research in the early twentieth century is not easily rel-

egated to the margins of what we might presume to call proper scientific

work, as if it were merely an embarrassing flight of fancy that the scien-

tific community has thankfully repudiated in favor of other topics more

clearly deserving of serious investigation. On the contrary, Ochorowicz’s

published reports of his work with Tomczyk and her control spirit pro-

vide us with an opportunity to revisit this very history of rejection and re

pression of psychic research. In particular, they invite us to ask, What do

we suppose lies on the far side of any visualization and recording in-

strument, and on what basis do we distinguish among such “occulted”

phenomena, granting some entities entry into the order of the real and

declaring others to be mere figments of the imagination or products of

fraudulence, equipment failure, or tainted powers of observation?

For quite some time, thanks to the tremendous powers of instrumented

observation at its disposal, modern scientific reasoning has concerned it-

self with the business of searching for, describing, and thereby according

ontological status to a wide range of phenomena that are normally invis-

ible or nonvisual or that can only be postulated or inferred from other

sources of knowledge, whether these be atomic particles, distant stars, elec

tromagnetic currents, sound waves, black holes, or events that are so eva-

nescent or slow moving they elude ordinary perception. However, psychic

research in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries provided a

context in which other candidates for scientific scrutiny—spirits, ghosts,

miraculous powers of perception and action—could be presented on a

level playing field and in which claims about evidence of such things could

be taken seriously among even some of the most established authorities.

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

928 Jeremy Stolow / The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

Most remarkable, in Ochorowicz’s case, was the scientist’s ability to enter

into sustained discussion with his peers about evidence that he claimed

could only have been generated by Little Stasia herself. Whereas we today

might be tempted to assume there could only have been three actors pres-

ent at the scene of this photographic event—Ochorowicz, Tomczyk, and

the camera—Ochorowicz (and many others who granted him the benefit

of the doubt) could find no justifiable grounds for excluding the presence

of a fourth actor: Little Stasia, an impish, normally invisible creature of

the spirit world.

If we are willing, at least temporarily, to accept, as Ochorowicz did, the

possibility that Little Stasia was both the progenitor and the subject of this

seemingly incredible photographic document, we might find ourselves in

a rather unsettling situation. The cosmic order of things that has long

been familiar to clairvoyants, spiritual healers, and other adepts steeped

in traditions of esoteric vision is now proclaimed to fall within the remit

of instruments of visualization and representation that serve as the very

hallmark of scientific standards of observation and evidence gathering.

Indeed, for Ochorowicz and his supporters, the evidence produced during

his séances with Tomczyk was not so different from that pertaining to any

other nonvisible object of science. The only added condition was that the

particular realities in question could only be observed in the presence of a

spirit medium, since it was only in the circuit conjoining photographic ap-

paratus and spirit, and scientist and medium, that these mysterious forces

could manifest and make themselves available for visual detection and

inscription. By adopting a stance that some call ontologically pluralist, we

would have to suspend here our rush to judgment that there cannot exist

such things as spirits or other occult forces that defy available explanatory

frameworks. We would equally require ourselves to leave open the possi-

bility for certain uniquely endowed (or carefully trained) individuals to

perceive and conjure such entities and forces and thereby make them visi-

ble (if only ephemerally) in our mundane world, such as in the work per-

formed by photographic and other instruments of scientific observation.

I suggest we have good reasons to hold in check our most instinctive as-

sumptions about the authenticity of Ochorowicz’s photographic evidence

of the spirit world; among other things this episode throws into relief some

troubling questions about indexicality and realism that lie at the heart of

all practices of observing and knowing the world through the mediation

of instruments. What indeed is the reality to which a visual medium such

as photography points? What are the assumptions about indexical refer-

ence that lie behind efforts to render the invisible world visible, and on

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Critical Inquiry / Summer 2016 929

what terms can judgment about such matters be pronounced? These are

the key questions I shall take up at the end of this essay.

For Ochorowicz, as we shall see in more detail presently, new answers

to these very questions emerged in a program of research dedicated to

documenting and explaining the mysterious powers that had enabled

Little Stasia’s self-portrait to emerge. His experimental procedure began

from an initial observation that the very figure of Little Stasia seemed to be

composed of even subtler distributions of an unknown energy source, and

it thus became his task to break down those patterns into their elemen-

tal forms. Part navigating instrument, part inscription machine, Ochoro-

wicz’s photographic apparatus plumbed the depths of this occulted reality,

documenting hitherto invisible sources of latent energy that, under pro-

pitious conditions, could take visible form as streaks or flashes of light,

dull glowing orbs, or even the shape of human body parts, as intimated

by the inaugural event of Little Stasia’s self-portrait and later confirmed,

to Ochorowicz’s great satisfaction, in a startling series of images of astrally

projected human hands. This mise en abyme of hidden forces within hid-

den forces demanded of Ochorowicz the coining of a new vocabulary,

including mediumnic lights (lumières mediumniques), rigid rays (rayons

rigides), and Xx-Rays (rayons Xx). Their study, Ochorowicz was convinced,

promised to help unlock some deep secrets of a radiant universe that was

only beginning to be documented, let alone understood. But even more

important, for our purposes here, was the very manner of Ochorowicz’s

investigative procedure by virtue of which the spirit world became instru-

mentally detectable, navigable, and visible in new ways.

To appreciate how a document such as Little Stasia’s self-portrait could

have served as the basis of a scientific research program we must attend to

the context of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century metropolitan

fascinations with psychic and occult phenomena. It was a period in which

the frontiers demarcating mind, body, and environment were far from

fixed, and objects readily moved among the discursive registers of energy

physics, psychology, biology, medicine, spiritualist performance, esoteric

philosophy, and mystical practice. Such permeabilities were present in the

voluminous outpouring of reported experiments, theoretical speculations,

and notes from the field detailing the existence of invisible emanations, vi-

tal energies, mental projections, and other radiant forces that defied both

commonsense experience and accepted scientific explanation. As a focal

point of debate among professional scientists and also a subject of interest

to esoteric writers and audiences, Ochorowicz’s submissions to the An-

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

930 Jeremy Stolow / The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

nales typified what was in fact a widespread fin-de-siècle preoccupation

with the detection and visualization of phenomena that one might best

call occult in the most literal sense of that word, meaning “hidden from

view” or “not manifest to direct observation.”6

Efforts to define, detect, depict, and intervene into occult objects—in-

cluding radiant energies, subtle vibrations, and vital forces—are of course

nothing new; they belong to a much longer history in which physicists,

mystics, folk healers, doctors, artists, and philosophers encountered one

another at different moments in and across diverse regions of the world.

The genealogy of such phenomena is thus complexly overlaid by diverse

vocabularies and frames of interpretation, from theories of magnetism

and electrostatic energy familiar to ancient Greek and Persian philoso-

phers to notions of an all-encompassing, life-giving force said to bind

body with spirit and the heavens above with the earth below, such as ‘qi in

classical Chinese medicine, prana in the Vedic tradition, and the principle

of archaeus in the cosmology of the Renaissance alchemist Paracelsus. 7

Representations of such occult phenomena enjoyed wide circulation in

nineteenth-century metropolitan society in large measure thanks to the

growth of popular science writing and public demonstrations but also

on account of the work of esotericists such as Eliphas Lévi and Helena

Petrovna Blavatsky (the founder of the Theosophical Society). Lévi and

Blavatsky were only two members of a growing cohort of commentators

from an occult perspective on advances in medicine, biology, psychology,

and energy physics, treating each scientific discovery as a modern-day

confirmation of cosmological knowledge and wisdom derived from an-

cient Greek, Hebrew, Indian, and Chinese sources.8 Indeed, according to a

6. Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “occult.” For a history of the term occult, from the

qualitates occultae of mediaeval Scholasticism to the modern definition that emphasizes

secrecy, see Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Esotericism and the Academy: Rejected Knowledge in Western

Culture (Cambridge, 2012), p. 179; Keith Hutchison, “What Happened to Occult Qualities in

the Scientific Revolution?” Isis 73 (June 1982): 233–53; and Florian Sprenger, “Insensible and

Inexplicable: On the Two Meanings of Occult,” Communication+1 4 (2015): scholarworks.umass

.edu/cpo/vol4/iss1/2.

7. On Indian and Chinese medical systems, and their (quite long) history of connections

with the development of Western allopathic medicine, see Roberta Bivins, Alternative Medicine?

A History (Oxford, 2007). On Paracelsus, see Walter Pagel, Paracelsus: An Introduction to

Philosophical Medicine in the Era of the Renaissance (Basel, 1982). Compare Alvarado, “Human

Radiations: Concepts of Force in Mesmerism, Spiritualism, and Psychical Research,” Journal of

the Society for Psychical Research 70 (July 2006): 138–62.

8. See Eliphas Lévi, Dogme et rituel de la haute magie (Paris, 1861); Helena Petrovna

Blavatsky, Science, vol. 1 of Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern

Science and Theology (New York, 1877). On Lévi’s influence on Theosophy and connections with

late nineteenth-century energy physics, see Egil Asprem, “Pondering Imponderables: Occultism

in the Mirror of Late Classical Physics,” Aries 11, no. 2 (2011): 129–65. On the close alliance

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Critical Inquiry / Summer 2016 931

recurring theme in occult literature of the late nineteenth century, mod-

ern scientific paradigms—such as the luminiferous ether theory of Victo-

rian physics or theories of vitalism and neo-Lamarkism in biology—were

merely latecomers to a long-standing esoteric tradition that understood the

universe to be composed of a complex of overlapping energies and forces

joining the material world with higher, more subtle, or life-sustaining

planes of existence.9

Nevertheless, by the closing of the nineteenth century, esoteric writers

found themselves in a context quite unlike that of their forebears and in

the company of a new generation of interlocutors dedicated to the en-

terprise of psychical science research. This terrain of exchange between

esotericism and psychic science had been developing for a couple decades,

but it was dramatically reshaped in the aftermath of Wilhelm Röntgen’s

discovery of X-rays in 1895, Antoine Becquerel’s discovery of spontaneous

radioactivity in 1896, and the Curies’ discovery of radium and polonium

in 1898. That rapid succession of breakthroughs was decisive for the gen-

eration of entirely unprecedented scientific as well as cultural representa-

tions of an invisible universe beyond the reach of ordinary perception but

that now seemed to fall within the grasp of rapidly evolving instruments

and procedures of technologically mediated observation. New methods of

scientific visualization involving the use of equipment such as Crookes tubes,

fluorescent screens, precision-timed electrical charges, and cutting-edge

photographic apparatuses thus stood at the heart of an emerging epistemo

logical and cultural framework that Linda Henderson incisively labeled

“vibratory modernism”—a term that highlights the period’s intense pre-

occupation and imaginative engagement with new forms of radiant energy

located beyond the spectrum of visible light, the precise nature of which

remained a subject of considerable debate as different methods of inves-

tigation produced apparently contradictory observations and pointed to-

ward divergent theoretical conclusions.10 Ochorowicz’s engagements with

between occultism and modernism in fin-de-siècle Britain, not least as demonstrated by the

relationship by Theosophy and science, see especially Alex Owen, The Place of Enchantment:

British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern (Chicago, 2004).

9. A related history, beyond the scope of this article, would trace the influence of

mesmerism; on that topic, see both Emily Ogden and John Tresch, this issue.

10. See Linda Dalrymple Henderson, “Vibratory Modernism: Boccioni, Kupka, and the

Ether of Space,” in From Energy to Information: Representation in Science, Technology, Art,

and Literature, ed. Bruce Clarke and Henderson (Stanford, Calif., 2002), pp. 126–49. See also

Henderson, “X-Rays and the Quest for Invisible Reality in the Art of Kupka, Duchamp, and

the Cubists,” Art Journal 47 (Winter 1988): 323–40. On the cultural impact of the discovery of

X-rays, see also Allen W. Grove, “Röntgen’s Ghosts: Photography, X-Rays, and the Victorian

Imagination,” Literature and Medicine 16 (Fall 1997): 141–73, and Simone Natale, “The Invisible

Made Visible: X-Rays as Attraction and Visual Medium at the End of the Nineteenth Century,”

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

932 Jeremy Stolow / The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

Tomczyk and Little Stasia took place in the midst of this proliferation of

investigations, claims of discovery, and theoretical accounts of hitherto

undocumented sources of radiant energy, alongside Prosper-René Blond-

lot’s N-rays, Gustave Le Bon’s lumière noire (“black light”), and other rays

of mysterious provenance that vied for the attention and consecration of

established scientific bodies such as the Académie de Sciences.11

As far as the French occultist reading public was concerned, the discov-

ery of X-radiation and related research seemed to confirm a long-standing

esoteric claim that the universe was composed of a plethora of subtle

vibrations and hidden energies and forces. So, for instance, the newly

discovered powers of radioactive substances to change the chemical com-

position of objects that fell within their range of emission readily called to

mind the long-familiar notion of alchemical transmutation. But the visual

culture of radiography also opened up new frontiers of possibility for the

occultist imagination. Among other things, X-rays could now be aligned

with paranormal phenomena such as telekinesis or clairvoyant percep

tion insofar as they all referenced a common level of reality located be-

yond the visible light spectrum but capable of being pictured—provided

that one had access to the right instruments or special powers. So it was

possible to phrase new versions of old questions, as did French fin-de-

siècle occultist Henri Antoine Jules-Bois: “Couldn’t there also exist X-gazes,

just as there exist X-rays?”12 That question was answered in the affirmative

by a succession of esoteric writers and psychic researchers who shared

the hypothesis that clairvoyants and spirit mediums were distinguished

by their peculiarly enhanced faculties of perception. Such humans, it was

proposed, possessed unique biological equipment comparable to that of

advanced scientific visualization equipment, such as Crookes tubes, high-

speed camera shutters, and orthochromatic photographic plates that were

insensitive to visible light.13 Second-generation Theosophists Charles

Media History 17, no. 4 (2011): 345–58. On the impact of radiography on the history of medicine,

see Monika Dommann, Durchsicht, Einsicht, Vorsicht: Eine Geschichte der Röntgenstrahlen,

1896–1963 (Zürich, 2003).

11. See, among others, Mary Jo Nye, “N-Rays: An Episode in the History and Psychology of

Science,” Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 11, no. 1 (1980): 125–56 and “Gustave Le Bon’s

Black Light: A Study in Physics and Philosophy in France at the Turn of the Century,” Historical

Studies in the Physical Sciences 4 (Jan. 1974): 163–95.

12. Henri Antoine Jules-Bois, “L’Âme scientifique,” La Revue Spirite 39 (June 1896): 355;

quoted in Sabine Flach, “Thinking about/on Thinking: Observations on the Thought

Photography of the Early Twentieth Century,” Configurations 18 (Fall 2010): 451.

13. See, for instance, P. Bloche, “Les Rayons cathodiques et la lumière astrale,” La Revue

Spirite 4 (Nov. 1897): 669. Speculation about the difference between the optical capacities

of spirit mediums and those of “ordinary” eyes was a recurring topic in both psychical and

occultist literature of the period. See, for instance, M. F-J Pillet, “Les Erreurs de l’œil,” Annales

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Critical Inquiry / Summer 2016 933

Leadbeater and Annie Besant (whose work was widely familiar to early

twentieth-century French occultists) similarly took advantage of the con-

ceptual resources of new wave and ray discoveries to buttress their own ef-

forts to visualize and record information about “the subtle forces by which

the soul . . . expresses itself,” although, they hastened to add, the work of

their scientific contemporaries was “necessarily imperfect . . ., a physical

photographic camera and sensitive plates not being ideal instruments for

astral research.”14

With these words, Leadbeater and Besant gave voice to what was in fact

a widespread ambivalence among occultists regarding scientific evidence

and especially the instrumental mediation of invisible dimensions of the

universe. In agreement with “mainstream” science researchers, esoteric

writers understood X-radiation to point to a new frontier of visualiza-

tion—one defined by what Kelley Wilder has called the power of “pene-

trative observation”15—that raised serious ontological questions about the

relationship between instrumentation and the occult. Among both psy-

chic researchers and esoteric occultists the photographic medium in par-

ticular seemed key to this emerging terrain of possibility for rendering

visible the invisible. If some, like Leadbeater and Besant, were hesitant to

endorse photography as a viable tool of esoteric revelation, preferring in-

stead to trust only their native powers of clairvoyant perception, others

saw an important opportunity to produce visible evidence that would

confirm long-held understandings of occult phenomena. “Occultism de-

mands photographs!” cried one article published in a 1908 edition of the

spiritist journal La Paix Universelle.16

From their very beginnings, it should be recalled, photographic instru-

ments performed a range of functions: to represent, to detect, to measure,

to archive, and to extend the range of the visible in order to produce new

types of observables. These hybrid functions informed the use of pho-

tography in a wide range of social and cultural domains, not least in the

des Sciences Psychiques 11 (May–June 1901): 129–47, and anon., “Les Yeux des mediums,” Annales

des Sciences Psychiques 15 (Jan. 1905): 46–47.

14. Annie Besant and Charles W. Leadbeater, Thought-Forms (London, 1901), pp. 2–3.

Compare Leadbeater, Man Visible and Invisible: Examples of Different Types of Men as Seen by

Means of Trained Clairvoyance (London, 1902). On the connection between Leadbeater and

Besant and French psychical research, see Flach, “Thinking about/on Thinking,” pp. 449–51.

15. Kelley Wilder, Photography and Science (London, 2009), p. 50.

16. A. Bouvier, “L’Occultisme demande des photographes,” La Paix Universelle, 15–31

Mar. 1908, pp. 1–4. Occult endorsements of photography had already been in circulation for some

time. See, for instance, the extensive discussion of the merits of photography for manifesting

pictorially occult phenomena by the influential fin-de-siècle French occultist, Papus [Gérard

Encausse], Les Rayons invisibles et les dernières expériences d’Eusapia devant l’occultisme (Tours,

1896).

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

934 Jeremy Stolow / The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

incorporation of the photographic apparatus into the work of scientific

visualization. Historians of science have established in detail how, from

its inception in the mid-nineteenth century, the photographic camera was

hailed as a medium uniquely suited to free scientifically minded observers

from artistic contamination, replacing the subjective vision of the human

eye with a mechanical means of documenting visible and even normally

invisible things.17 In William Henry Fox Talbot’s prescient formulation,

“the eye of the camera would see plainly where the human eye would find

nothing but darkness.”18 This propensity for seeing plainly would place the

photographic camera among a larger class of inscription instruments that

appeared to speak “nature’s own language” and thereby served as guaran-

tors of objective truth.19

As the century progressed the assumption that the photographic ap-

paratus constituted an ideal observer and that its medium of inscription,

the photosensitive plate, could provide a direct index of external reality

became ever more firmly tied to a growing appreciation that the reality

to which photography pointed was inaccessible to even the most highly

trained observers. Thanks to improvements in photosensitive plates (such

as the innovation of the gelatin silver bromide process), ever-faster shutter

speeds, and magnesium-based flash lighting, it had become possible to

photographically capture an expanding universe of phenomena that radi-

cally transcended the visual terrain of “ordinary” perception: the minutiae

of a pedestrian’s gait; the bodily agitations of a hysterical patient in a state

of crisis; a sequence of solar protuberances; the precise moment when

a lightning bolt strikes; the invisibly slow movement of certain physical

bodies over extended periods of time; and so on.20 New precision instru-

17. See, for instance, Beauty of Another Order: Photography in Science, ed. Ann Thomas

(New Haven, Conn., 1997), and Jennifer Tucker, Nature Exposed: Photography as Eyewitness in

Victorian Science (Baltimore, 2005).

18. William Henry Fox Talbot, The Pencil of Nature (London, 1844), p. 30; quoted in Wilder,

Photography and Science, p. 19.

19. Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, “The Image of Objectivity,” Representations, no. 40

(Fall 1992): 116.

20. See Eadweard Muybridge, Animal Locomotion: An Electro-Photographic Investigation

of Connective Phases of Animal Movements (Philadelphia, 1887); Iconographie photographique

de la Salpêtrière, ed. Paul Regnard Bourneville and Jean Martin Charcot (Paris, 1878); and

Étienne-Jules Marey, La Machine animale: Locomotion terrestre et sérienne (Paris, 1878). A rich

secondary literature has explored this topic. See especially Georges Didi-Huberman, Invention

de l’hystérie: Charcot et l’iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière (Paris, 1982); Marta Braun

and Elizabeth Whitcombe, “Marey, Muybridge, and Londe: The Photography of Pathological

Locomotion,” History of Photography 23, no. 3 (1999): 218–24; Braun, Picturing Time: The Work

of Étienne-Jules Marey, 1830–1904 (Chicago, 1994); Joel Snyder, “Visualization and Visibility,” in

Picturing Science, Producing Art, ed. Caroline A. Jones and Galison (New York, 1998), pp. 379–97;

Ulrich Baer, “Photography and Hysteria: Toward a Poetics of the Flash,” Spectral Evidence:

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Critical Inquiry / Summer 2016 935

ments were thus capable of generating visualizations of operations that

occurred outside the sensory realm in the form of photographs, curvilin-

ear transcriptions, and other graphic representations that did not simply

extend or improve upon what could otherwise be seen by trained observ-

ers. Rather, they manifested pictorially a reality that was otherwise impos-

sible to perceive.21 As Joel Snyder has put it, the reliability of mechanically

generated visualizations could no longer be established with recourse to

“a human arbitrator, no matter how exquisitely sensitive or impartial. Ques

tions about the accuracy of these data [could] be resolved only by ap-

pealing to other, perhaps even more refined mechanical instruments.”22

Scientific photographs thus increasingly came to be understood not as

documents of things already available to (trained) observers but rather as

technologically mediated conditions of vision itself—images that cannot

be detached from the apparatus that generates them.

The promise of instruments to register a reality that could not other-

wise be known was central to the enterprise of psychic research in this

period. In fact, Ochorowicz’s study of Little Stasia’s self-portrait and the

subsequent experiments he designed in order to document and explain

the conditions of possibility for spirits to interact with the world known

to ordinary perception rested on what by the second decade of the twen-

tieth century had already developed into a vibrant tradition of psychical

research incorporating all the latest available technical instruments and

procedures for registering the insensible world of spirits and their atten-

dant sources of mysterious energy. Alongside innovations in photographic

apparatus, psychic researchers developed and came to depend on a wide

range of graphing and recording instruments, such as the biomètre, first

introduced in the mid-1890s by Hippolyte Baraduc, a medical specialist in

The Photography of Trauma (Cambridge, Mass., 2002), pp. 25–60; Jimena Canales, A Tenth

of a Second: A History (Chicago, 2009); Phillip Prodger, Time Stands Still: Muybridge and the

Instantaneous Photography Movement (Oxford, 2003); Peter Geimer, “Picturing the Black Box:

On Blanks in Nineteenth-Century Paintings and Photographs,” Science in Context 17 (Dec. 2004):

467–501; and Wilder, “Visualizing Radiation: The Photographs of Henri Becquerel,” in Histories

of Scientific Observation, ed. Daston and Elizabeth Lunbeck (Chicago, 2011), pp. 349–68. On

advances in photographic chemistry during this period, which were equally crucial for the

development of “instantaneous photography,” see Wilder, Photography and Science, p. 53.

21. On the scientific visualization of normally invisible or nonvisual phenomena,

see, among others, Representation in Scientific Practice Revisited, ed. Catelijne Coopmans

(Cambridge, Mass., 2014), and Visual Cultures of Science: Rethinking Representational Practices

in Knowledge Building and Science Communication, ed. Luc Pauwels (Hanover, N.H., 2006). On

the relationship between instrumented observation and psychic research in the early twentieth

century, see also Richard Noakes, “The ‘World of the Infinitely Little’: Connecting Physical

and Psychical Realities Circa 1900,” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 39 (Sept. 2008):

323–34.

22. Snyder, “Visualization and Visibility,” p. 380.

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

936 Jeremy Stolow / The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

nervous disorders at Salpêtrière hospital in Paris and a key figure strad-

dling the worlds of occultism and psychic science in France. The biomètre

was a relatively simple device consisting of a needle suspended by a thread

within a glass jar, the movements of which, Baraduc contended, indexed

a subject’s “vital state”; as the subject’s hands approached the region of

the jar, the needle was noted to react to the atmospheric redistribution of

“primordial fluidic perturbations of the vital body.”23 Baraduc’s biomètre

was in fact only one of several measuring devices proclaimed to be ca-

pable of detecting hitherto unknown subtle energy forces. For his part,

long before his experiments with Tomczyk, Ochorowicz had invented the

hypnoscope, an instrument consisting of a tubular magnet that could be

placed around the finger of a person in order to detect varying degrees of

susceptibility to hypnosis; in his view, the hypnoscope registered effects

that could not be accounted for by the work of hypnotic suggestion itself,

thereby pointing to the existence of “the substratum of another action,

which is so weak . . . that it hides itself from our instruments, and exhib-

its itself only through the intermedium of exceptionally sensitive nervous

systems.”24

But for Ochorowicz, Baraduc, and many other researchers of this pe-

riod, the most promising technologies for detecting and recording fluid

energies were photographic and photoemulsive in nature. The photo-

graphic apparatus seemed uniquely capable of generating both an iconic

and an indexical relationship with its referent and thus offered a source

of reliable visual information with a richness of detail unparalleled by

other instruments and procedures of scientific observation (this is a mat

ter to which I shall return at the end of the essay). Baraduc himself was

widely celebrated for having photographically captured a range of in-

visible radiations surrounding botanical specimens, human fingertips,

and other materials. Experimental photographic techniques (such as the

application of electrical discharges directly onto photosensitive plates)

were developed and incorporated into the work of a number of research-

ers devoted to the study of psychic and occult phenomena, including

Albert de Rochas, Louis Darget, Jules Bernard Luys, Émile David, Ja-

kob von Narkiewicz-Jodko, Fernand Girod, and Emmanuel-Napoléon

23. Hippolyte Baraduc, La Force vitale: Notre Corps vital fluidique et sa formule biomètrique

(Paris, 1893), p. 162. See also Baraduc, Les Vibrations de la vitalité humaine: Méthode biométrique

appliquée aux sensitifs et aux névrosés (Paris, 1904).

24. Ochorowicz, “A New Hypnoscope,” Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 1

(Feb. 1885): 281. For discussion of Ochorowicz’s use of this apparatus, see Alvarado, “Modern

Animal Magnetism: The Work of Alexandre Baréty, Émile Boirac, and Julien Ochorowicz,”

Australian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis 37 (Nov. 2009): 75–89.

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Critical Inquiry / Summer 2016 937

Santini; collectively, they were responsible for producing a genre of

photographically mediated visualizations that came to be known as ef-

fluviographie, or photographie de la pensée, which purported to reveal

the radiant exteriorizations of diverse vital energies, dreams, conscious

thoughts, fluctuations in emotional and nervous states, and even—as Ba

raduc proclaimed to have achieved—photographic evidence of the flight

of the soul from the body at the precise moment of death.25 By the early

twentieth century, such efforts to document photographically extraor-

dinary psychic phenomena reached one significant apogee with the pro-

duction of widely reported pictures of ectoplasms: remarkable and, to

many observers, shocking and outlandish excretions discharged from

the orifices of mediums during moments of spirit possession. Ecto-

plasms were said to take various shapes and could even bear the imprint

of human faces, but their materialization was so evanescent they could

only be properly witnessed, examined, and preserved photographically,

as Charles Richet had proclaimed to have achieved in his pioneering

1905 study of the ectoplasmic projections of the medium Eva Carrière

and as Albert von Schrenck-Notzing further developed in his magnum

opus on the topic, Phenomena of Materialization (1914).26 As all these

25. See, among others, Baraduc, Méthode de radiographie humaine: La Courbe cosmique:

Photographie des vibrations de l’éther (Paris, 1897) and L’Âme Humaine: Ses Mouvements, ses

lumières, et l’iconographie de l’invisible fluidique, nouvelle édition (Paris, 1911); Jules Bernard

Luys and Émile David, “Photographie des étincelles électriques dérivant soit de l’électricité

dynamique (bobine de Ruhmkorff), soit de l’électricité statique (machine de Wimshurst),”

Société de Biologie, 8 May 1897, pp. 449–53; Jules Bernard Luys and Émile David, “Note sur

l’enregistrement photographique des effluves qui se dégagent des extrémités des doigts et du

fond de l’oeil de l’être vivant, à l’état physiologique et à l’état pathologique,” Société de Biologie,

29 May 1897, pp. 515–19; Albert de Rochas, L’Extériorisation de la sensibilité: Étude expérimentale

et historique (Paris, 1895); Emmanuel-Napoléon Santini, Photographie des effluves humains:

historique, discussion, etc. (Paris, 1898); and Fernand Girod, Pour photographier les rayons

humains: Exposé historique et pratique de toutes les méthodes concourant à la mise en valeur du

rayonnement fluidique humain (Paris, 1912). A vibrant secondary literature has documented

the development of effluviography in fin-de-siècle France. See Flach, “Thinking about/on

Thinking,” pp. 441–58, and Chéroux, “Photographs of Fluids: An Alphabet of Invisible Rays,” in

The Perfect Medium, pp. 114–25. On Narkiewicz-Jodko’s photographic experiments, see Krauss,

Beyond Light and Shadow, pp. 31–34.

26. See Charles Richet, Les Phénomènes dits de matérialisation (Paris, 1906); Charles Richet

Traité de métapsychique (Paris, 1922), p. 581; and Albert von Schrenck-Notzing, Materialisations-

Phaenomene: Ein Beitrag zur Erforschung der mediumistischen Teleplastie (Munich, 1914).

Another key figure in the study of ectoplasm was Gustave Geley, who participated in many

of the early séances with Eva C. and who went on to found the Institut Métaphysique

International, the key French organization for psychic research in the 1920s. See Gustave Geley,

L’Ectoplasmie et la clairvoyance (Paris, 1924). For a brilliant analysis of ectoplasm research and

its connections with late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century biology and art, see Robert

Michael Brain, “Materialising the Medium: Ectoplasm and the Quest for Supra-Normal Biology

in Fin-de-Siècle Science and Art,” in Vibratory Modernism, ed. Anthony Enns and Shelley

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

938 Jeremy Stolow / The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

examples indicate, as an instrument of documentation, visualization,

and pictorial manifestation of occult forces, the photographic apparatus

stood at the very heart of psychic sciences and their exchanges with es-

oteric thought and practice, making it seem impossible in this historical

moment to encounter the occult without instrumentation. The inverse,

it seems, is also true; it was impossible to conceive of instrumental me-

diation without reference to the occult.

Let us return to the research Ochorowicz conducted in the aftermath

of Little Stasia’s momentous, if controversial, photographic self-portrait.

As Little Satia had explained to the doctor, “ ‘I photographed myself . . .

in order to give you proof that I am not just some sort of “force” ema-

nating from the medium, but indeed that I am an independent entity’ ”

(“PL,” p. 198). But what sort of entity was she? Ochorowicz’s first step

consisted of inspecting the photograph with a magnifying glass, upon

which he made a curious discovery. He noticed that the figure of Lit-

tle Stasia was bordered by “a series of tiny, corpuscular spheres of light,

juxtaposed to one another, some brighter than others, some seemingly

glowing by their own light or by reflection of another light source. . . .

What could these be?” he asked (“PL,” p. 198). Upon questioning Little

Stasia, he learned that the spirit was herself a medium in and through

which other, even subtler distributions of energy might come into view.

“ ‘What is this bright border surrounding your figure?’ ” Ochorowicz

asked. “ ‘I don’t know how to explain that,’ ” Little Stasia replied. “ ‘They

are like small balls, without which I cannot take form. I am composed of a

sort of vapor, which is condensed in my form and which also surrounds

me; the more rarefied the vapor, the more I remain invisible, the more

condensed, the more my figure takes shape, and also the more I can in-

teract with material objects.’ ” “ ‘So you are also the source of the light

that enabled this photograph? Was this light simply an act of your own

willpower?’ ” “ ‘Yes, in a way, by a willpower that produces a sort of phos-

phorescence in the air’ ” (“PL,” p. 199). Ochorowicz pressed Little Stasia

for further details about this mysterious light source, to which the spirit

responded, “ ‘I cannot explain it according to your wishes, but I could

demonstrate this light for you. Would you like me to?’ ” “ ‘I couldn’t ask

for more!’ ” (“PL,” p. 235).

Trower (New York, 2013), pp. 115–44. On the relationship between ectoplasms and the history

of photography, see also Karl Schoonover, “Ectoplasms, Evanescence, and Photography,” Art

Journal 62 (Autumn 2003): 30–43.

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Critical Inquiry / Summer 2016 939

Thus began a research program that would preoccupy Ochorowicz for

nearly two years, reports of which dominated the pages of the Annales and

were discussed more widely among nonexpert followers of psychic re-

search, including many commentators and readers of esoteric and occult

journals in which news of scientific discoveries was frequently reported

and debated. During this time, Ochorowicz reported having borne wit-

ness to a number of luminescent spectacles orchestrated by Little Stasia,

including bright flashes of light, tiny threads of energy emanating from

the medium’s fingertips, and dull glowing orbs of a mysterious energy

that floated gently around the room during séances. Some of these phe-

nomena were witnessed directly by Ochorowicz, while others came to be

known only when registered as actinic effects on photographic plates. In

one experiment conducted on 9 April 1909,

three cameras were set up in the middle of the room, near where

we were seated, without a table, in a circle forming a chain with the

medium. Given the position of the cameras and the poor lighting,

I did not believe that it would be possible to find any traces on the

photo plates. But when I developed them, a strange result obtained:

on all three plates, the effect of a flash of light is more or less visible.

In particular, what was unexpected was a bright curved line of light,

accompanied by a large irregularly shaped light and two smaller

points. But this line and these points, so brightly illuminated on the

plate, we did not see! None of those present remarked observing any

points or lines of light while we sat in the presence of Mlle Tomczyk.

[“PL,” p. 301]

A series of efforts ensued to capture these lights photographically, to

classify them, and to assign them meaning and purpose (fig. 2). Each ex-

periment seemed to evince new elemental properties, suggesting the need

for further investigation of a phenomenon that had initially seemed indi-

visible. One category of forces seemed to relate to Tomczyk’s telekinetic

powers, which seemed to involve the emanation of mysterious bands of

energy in straight lines that the medium could leverage in order to levitate

objects. Ochorowicz labeled these “rigid rays.” Albert von Schrenck Not-

zing, one of the witnesses to Ochorowicz’s experimental work, describes

these rigid rays as:

thread-like connections, which are formed between the fingers of the

medium when she brings her hands together. These may remain invis-

ible, and yet exert mechanical effects, as, for instance, by the motion

and raising of small objects without contact. When condensed, they

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

940 Jeremy Stolow / The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

FIGURE 2 . Mediumnic lights. Reproduction courtesy of Harvard University Library.

are visible and can be photographed. The author was present in Paris

at such a sitting and can vouch for the accuracy of this observation.

Besides, it was successfully tested by several Commissions, composed

of photographic experts and savants.27

27. Albert von Schrenck Notzing, Phenomena of Materialisation: A Contribution to the

Investigation of Mediumistic Teleplastics, trans. Edmund Edward Fournier D’Albe (London,

1923), p. 32. Schrenck Notzing was not the only enthusiastic supporter of Ochorowicz’s

photographic work; the Annales des Sciences Psychiques served as a forum for numerous letters

to the editor claiming to reproduce similar results utilizing techniques outlined in Ochorowicz’s

articles. See, for instance, Fernand Girod, Pour photographier les rayons humains, pp. 128–32, and

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Critical Inquiry / Summer 2016 941

Tomczyk’s ability to transform this mysterious energy source from

a state of latent invisibility to one of active, visible force became one of

the central preoccupations of Ochorowicz’s research agenda. “What was

especially interesting for us,” he writes, “is the fact that [Tomczyk’s per-

formance of] levitation is accompanied by certain, absolutely novel lu-

minescent phenomena, which remain completely invisible to the eye but

which are perfectly capable of being registered photographically” (“PL,”

p. 305).28 Moreover, once they had been enlarged, the photographs revealed

swellings and nodes along the threads, like the waves of a vibrating cord,

further convincing Ochorowicz that he had truly discovered an entirely

new and as yet undocumented source of energy in the form of “a light

which we have given the name ‘mediumnic’ although we have no knowl-

edge of it and cannot place it in any category of known light sources.”29

In another experiment, conducted on 14 April 1909, Ochorowicz re-

ports having “obtained one of the most important photographs, long de-

sired on my part, showing a ‘current’ of light between the thumbs of the

medium” (“PL,” p. 337). The opportunity to photograph this evasive phe-

nomenon occurred without warning in the midst of another experiment.

As Ochorowicz recounts, “I had prepared a 13 X 18 cm plate, and placed on

top of it a metal grill, which I supposed would allow us to see more clearly

the rigid rays emanating from the medium’s hand.” But at the moment

when the medium placed her hands on either side of the plate, Little Sta-

sia interjected: “ ‘I can’t guarantee any current will appear, because there

is not enough force present at this moment. However, I could show you

anon., “Les Dernières Experiences avec Mlle Stanislawa Tomczyk,” Annales des Sciences Psychiques

19 (Sept. 1909): 287–88.

28. The existence of invisible lines of force was also widely familiar to psychic researchers

and séance attendees long before Ochorowicz began his experiments with Tomczyk. Numerous

reports were made of mediums, including (but not only) Eusapia Palladino, who, like Tomczyk,

was capable of producing near invisible, spiderlike threads that could reach distant objects in

the room and set them in motion. Explanations had been offered to account for the ability of

such mediums to “exteriorize motricity” and thus perform their remarkable acts of telekinesis;

see Rochas, L’Extériorisation de la motricité (Paris, 1906). As early as 1875, Francis Gerry Fairfield

had proposed the theory that spirit mediums were uniquely empowered to harness what he

called a “nerve-aura” that surrounds all organic structures, through which they could receive

otherwise inaccessible sensory impressions and which they were able to manipulate into desired

shapes (Francis Gerry Fairfield, Ten Years with Spiritual Mediums: An Inquiry Concerning

the Etiology of Certain Phenomena Called Spiritual [New York, 1875], p. 120). Also similar to

Ochorowicz’s study of Tomczyk was the report of Karl Blacher of Riga, who had studied the

medium, Frau Ideler, who was likewise capable of spinning threads in order to accomplish

her telekinetic feats, pulling on these nearly invisible lines of force from the inner side of her

hand with her fingertips; see Nandor Fodor, These Mysterious People (London, 1934), p. 238.

For comparison, see Michael Faraday’s engagement with spiritual phenomena, as discussed by

Bernard Geoghegan in this issue.

29. Quoted in Rolf H. Krauss, Beyond Light and Shadow (Munich, 1995), p. 78.

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

942 Jeremy Stolow / The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

FIGURE 3 . Photograph of the mediumnic field, revealing a metal grill and the fingertips of

the medium Stanislava Tomczyk. Reproduction courtesy of Harvard University Library.

something else quite pretty.’ ” “ ‘What, then?’ ” “ ‘An invisible flash. Maybe

it will also reveal some traces of the current you seek, but I can’t be sure’ ”

(“PL,” p. 338). Ochorowicz took up Little Stasia’s invitation and conducted

an extended photographic session, setting up his instruments according

to the spirit’s instruction. Upon developing the plates after the session was

concluded, Ochorowicz bore witness to the trace of a current whose ra-

diant pattern set into relief the outlines of figures representing the medi-

um’s fingertips, as well as the metal grill that had been placed between her

hands (fig. 3).

Further investigations were devoted to breaking down these various

rays, chains, and gaseous masses of energy in order to isolate their com-

ponent elements. The avenue Ochorowicz most energetically pursued was

related to Tomoczyk’s apparent ability, in cooperation with her control

spirit, to produce dull glowing orbs of light—presumably similar in na-

ture to those tiny spheres that Ochorowicz had first observed in Little Sta-

sia’s photograph, which by 1910 he had designated by the name Xx-rays.

As Ochorowicz explained, these rays possessed unique properties; in con-

trast with the rigid rays, Xx-rays seemed to “have no mechanical effect, but

a very strong chemical, actinic one, and a power of penetration exceed-

ing not only that of Röntgen’s X-rays but also that of gamma rays from

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Critical Inquiry / Summer 2016 943

F I G U R E 4 . Variously sized spherical formations produced by Xx-rays. Reproduction

Courtesy of Harvard University Library.

radioactive substances. They are always invisible, though they emerge

clearly on photographic plates in the form of geometric spheres”(fig. 4).30

Over the course of the following year and a half, Ochorowicz conducted

a great number of experiments designed to confirm the existence of these

manifestations and to continue to document their characteristics. Some of

these involved the use of a gold-leaf electroscope to determine whether any

of the medium’s currents were capable of traveling through diverse media,

including ones known to be poor conductors, such as rubber, hard wood,

and resin. Such tests, Ochorowicz was convinced, confirmed that the me-

dium’s powers could not be explained in terms of what was then known

about the properties of electromagnetic radiation.31 In other experiments,

he compared the effects of placing the medium’s hands directly on the

photographic plates or holding them at varying distances. He placed the

plates in boxes composed of different materials, including black or white

cardboard, wood, and even lead, a material already well established to be

of sufficient density to fully shield the plates from radioactive effects. But

Tomczyk’s rays seemed able to penetrate even the lead shield in order to

produce actinic effects on the photosensitive plates.32

Over the course of 1911, Ochorowicz produced a series of photographs

that he considered among his crowning achievements. They purported

to register the medium’s astral double, an ethereal force that could leave

30. Ochorowicz, “Les Rayons rigides et les rayons Xx: Etudes expérimentales,” Annales des

Sciences Psychiques 20 (Apr. 1910): 98.

31. See ibid., p. 339.

32. See ibid., pp. 338, 358–62.

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

944 Jeremy Stolow / The Spirit Who Photographed Herself

FIGURE 5 . A “fluidic hand” of the medium Stanislava Tomczyk ‘s double. Reproduction

Courtesy of Harvard University Library.

the medium’s body and materialize itself sufficiently to leave its image

on a photographic plate. Such a partial materialization, in the form of a

“fluidic hand,” first took place during a séance held on 4 April 1911 (fig. 5).33

33. Ochorowicz, “Radiographie des mains,” Annales des Sciences Psychiques 21 (Oct. 1911): 296.

This content downloaded from 128.252.067.066 on July 26, 2016 09:48:55 AM

All use subject to University of Chicago Press Terms and Conditions (http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/t-and-c).

Critical Inquiry / Summer 2016 945

It happened unexpectedly during an attempt to capture Xx-rays when the

somnambulant had suggested that a plate be held in front of her. “ ‘What

fun,’ ” Little Stasia interjected in the middle of this experiment. “ ‘I see a

shadow of my hand there.’ ”34 To Ochorowicz’s amazement, the developed

plate showed a misshapen hand with a blurred shadow. Through suc-

cessive attempts, a series of well-materialized, visible hands were photo-

graphed by these astral projections directly onto the photographic plates.

Whether these astral projections were a product of Tomczyk’s native

willpower or emerged with the added help of Little Stasia remained un-

clear to Ochorowicz. But the photo documentation of this ethereal phe-

nomenon did provide what he considered to be incontestable evidence

that the material world as we normally see it constitutes only a pale surface

covering a vast universe of invisible fluids and forces that defied mechan-

ical conceptions of location, movement, and interactivity. Indeed, despite

the distance between Tomczyk and the photographic plate, the manifes-

tation of an astrally projected hand was treated by Ochorowicz as the

making of a photogram: an image produced through direct contact be-

tween the object represented and the sensitive emulsions lying on the sur-

face of the plate. Ochorowicz had thus produced in a single picture a visual

manifestation of the mysterious Xx-rays and at the same time rendered an

image through this same radiant medium. Formed without the work of

human eyes or even their mechanical corollary, a camera lens, this picture

was treated by Ochorowicz not as a representation of Tomczyk’s hand but

rather as an indexical sign: a chemical reaction produced directly on the

surface of a photoemulsive plate that bore the traces of a hidden universe

of fluid energies defying the known mechanical laws governing of the lo-

cation, movement, and interactivity of material objects.

Not unlike Becquerel’s famous photographs of radioactive emissions

from uranium salts that had been produced to much fanfare in the late

1890s, Ochorowicz’s photographs seemed to manifest themselves spon-

taneously—hidden powers that appeared suddenly out of the dark.35 But

unlike Bequerel’s images and many other scientific documents of nor-

mally invisible phenomena, Ochorowicz’s photographs seemed far from

spontaneous; their manifestation depended on the copresence and col-

laborative work of a spirit agent, photographic (and other) instruments,

and conditions of controlled observation managed by the scientist him-

self. For Ochorowicz, the most compelling grounds for accepting Little

Stasia’s role in the making of these images may very well have been the

34. Ibid., p. 301.

35. On Becquerel’s photography, see Wilder, “Visualizing Radiation,” pp. 355–61.