Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Modelo Pleno Empleo KK

Modelo Pleno Empleo KK

Uploaded by

Juan ToapantaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Modelo Pleno Empleo KK

Modelo Pleno Empleo KK

Uploaded by

Juan ToapantaCopyright:

Available Formats

A Model of Full-Employment Growth for Developing Economies

Author(s): KENNETH K. KURIHARA

Source: Pakistan Economic and Social Review, Vol. 10, No. 1 (JUNE 1972), pp. 1-7

Published by: Department of Economics, University of the Punjab

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25824724 .

Accessed: 22/06/2014 20:50

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Department of Economics, University of the Punjab is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Pakistan Economic and Social Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.129 on Sun, 22 Jun 2014 20:50:02 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A Model of Full-Employment Growth for

Economies

Developing

L Preliminary Observations

Underemployment and underdevelopment are the twin problems

confronting all developing economies. And yet economic development

per se does not make for full employment, even as many advanced econo

mies are observably confronted with chronic underemployment. As far

as developing economies are concerned, it is not the growth of effective

demand but the growth of productive capacity that fundamentally makes

for or against continuous full employment. To be more specific, it is the

growth of output and capital relative to that of population that determines

whether or not a developing economy is to be persistently underemployed.

Thus such trendforces as population growth, technological advance, and

capital accumulation must be explicitly introduced into any employment

theory that purports to provide a causally significant explanation of secular

underemployment especially in an underdeveloped economy.

Keynes' General Theory lacks generality and applicability in that it

precludes such trend forces as mentioned above. As a consequence,

various post-Keynesian attempts have been made to secularize and

dynamize Keynes' short-run static theory of employment.1 Thus, for

example, Harrod complained : "To secure full employment in the short

period without regard to what may be necessary for securing a steady rate

of progress is short-sighted."2 The essence of Harrod's argument is that

the "warranted" rate of growth of effective demand associated with

"involuntary unemployment" must be made to equal the "natural" rate of

growth of productive capacity determined by population growth and

technological progress. Like Keynes, Harrod considers employment

largely as a function of effective demand, although effective demand is

transformable into capital accumulation via the acceleration principle.3

Unlike Harrod, Domar makes no reference to population and technology

as co-determinants of

employment.4 Both Harrod and Domar are

obviously concerned with the unemployment problem of advanced market

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.129 on Sun, 22 Jun 2014 20:50:02 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2 PAKISTAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL REVIEW

economics with their characteristic deficiency of effective demand.

Joan Robinson gave Harrod credit for having "led us toMarx's theory

of the reserve labour, which expands and contracts as the growth of

population runs faster or slower than the rate of capital accumulation."5

She distinguished "Marxian unemployment." as such, from "Keynesian

unemployment" arising from insufficientdemand, but failed to recognize

that part of "Marxian unemployment" which Paul Sweezy attributed to

technological change.* Her subsequent model showed that profits and

capital must be accumulated at such a rate as to equip a given labor popu

lation.7 Joan Robinson's smashing emphasis on the profit rate seems to

make her growth model more applicable to historical capitalism than to

present-day developing economies which are capital-poor yet not somarket

oriented as some advanced economies.*

These and other writers have offered capital accumulation (in one

form or another) as the panacea for the problem of chronic underemploy

ment, and also suffer from their constancy assumption about demographi

cal and technological coefficients. Accordingly, I propose in this paper

to construct a rather more

comprehensive model of full-employment

growth for developing economies on flexible assumptions about trend forces

than those built in other post-Keynesian writings (including my earlier

ones).

II. Population Growth and A Controllable Labor Force

Let us begin with the supply side of employment in a developing

economy. The total labor force to be fully employed is functionally re

lated to total population via

(1.1) L=i+aP, (a=dL/dP^:const.,cUo)

where L is the aggregate supply of labor or simply the labor force, P the

size of population, a the average-marginal manpower coefficient, and a a

zero intercept. The labor-population ratio a reflects the community's

choice between work and leisure, and is usually regarded as a culturally

given parameter. However, we shall assume this manpower coefficient

to be independently variable in the interest of greater generality, as the

.The prefix"some" here implies thatother advanced economies are so comple

telyplanned or Committed to full-employmentpublic policy as to rendertheproblem

ofmass unemploymentnonexistentor insignificant.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.129 on Sun, 22 Jun 2014 20:50:02 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

KURIHARA :MODEL OF FULL-EMPLOYMENT GROWTH 3

indicator accompanying equation (1.1) specifies. We shall bring out the

policy implications of this assumption later.

In the general case where a is independently variable, the differential

of equation (1.1) becomes

(1.2) dL=9-^d

da +^dP<**

= Pda + adP.

From (1.1) and (1.2) we can derive the rate of growth of the labor

force :

K } L a + P

which shows that the total labor force is capable of growing at a rate

equal to the sum of the rate of change in themanpower coefficient (da/a

and the rateof growthof population (dP/P). Equation (1.3) suggeststhe

additional possibility of manipulating the rate of change in themanpower

coefficient, as well as the rate of growth of population.

To be more specific, equation (1.3) indicates the practical desirability

of reducingtherateof growthof the laborforce (dL/L) througheugenic

programs, contraception clinics, individual family planning, liberal abor

tion laws, and other measures affecting the rate of growth of population

(dP/P)* and/or through lower retirement ceilings, longer schooling,

stringent child-woman labor legislation, selective emigration, and other

ways affecting the rate of change in the manpower coefficient (da/a)**

as far as overpopulated underdeveloped economies are concerned. In

clusion of the independently variable rate of change in the manpower

in thisrespect,to recall Keynes* observation : "The time has

?It is interesting,

already come when each countryneeds a considerednational policy about what size of

Population, whether largeror smaller then at presentor the same, ismost expedient.

And having settledthispolicy,we must take steps to carry it intooperation. The time

may arrivea littlelaterwhen thecommunityas a whole must pay attentionto the innate

quality as well as to themere numbersof its futuremembers," (J.M.Keynes, Essays

inPersuasion, p. 319).

when he talks about his "natural"

**Harrod alludes to themanpower coefficient

rate of growthof output as being indicativeof "a correctbalance betweenwork and

leisure." (Towards a Dynamic Economics, p. 87). But he does not incorporateany

explicitmanpower coefficientintohis analysis.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.129 on Sun, 22 Jun 2014 20:50:02 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

4 PAKISTAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL REVIEW

coefficient

(dafa) inequation (1.3) enlargesthepolicy scopeforthedelibe

rate control of the labor force to be fully employed, especially in those

developing economies which cannot readily decrease the rate of growth

of population for religious, sociological, and other extra-economic reasons.

It should be added that population control, however difficult, is consistent

also with a developing economy's ardent desire to increase itsper capita

income.

Therate of growth of the labor force given by equation (1.3) must

be juxtaposed with an independently determined rate of growth of employ

ment. Let us, therefore, turn to the demand side of employment.

III. Output Growth, Technological Change, and Employment

We shall in this section assume that effective demand is always kept

equal to productive capacity through familiar Keynesian fiscal-monetary

policies. This assumption seems plausible to make in the present context

of a developing economy confronted with secular underemployment largely

for lack of capital to equip a large and growing labor population. How

ever, as mentioned at the outset, we shall deal not only with flexible capital

requirements but also with variable labor intensity in the subsequent dis

cussion of the employment function.

Labor-input and capital-input are combined in the overall production

function via the technological-structural relation of the form

(2.1)N/K=A ^ const.,

where N is the total amount of labor demanded or simply employment,

K the total amount of capital demanded as an input, and A the variable

labor-capital ratio which measures the degree of labor intensity for the

economy as a whole. The labor-capital ratio reflects both the labor-in

tensive or capital-intensive structure of the economy and the labor-saving

or labor-using nature of technological progress. If the economy happens

to be market oriented, the variability of the labor-capital ratio may be due

partly to a unitary or greater than unitary elasticity of substitution of labor

for capital with respect to factor prices.

Capital requirements are measured by the capital-output ratio :

(2.2) K/Y=b^ const.,

which variable ratio also reflects the nature of technological change and

the structure of industry as well as market conditions.8

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.129 on Sun, 22 Jun 2014 20:50:02 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

KURIHARA :MODEL OF FULL-EMPLOYMENT GROWTH 5

From (2.1) and (2.2) wc can derive the employment function of the

form

(2.3) N = A bY

which shows that the total amount of labor-input demanded depends on the

variable labor-capital ratio and the variable capital-output ratio as well

as productive capacity.

In the general case where A and b are independently variable, the

differential of equation (2.3) comes to

(2.4) dN=3C|bY)d,+

dA ^>dY 3Y

a(|bY)db+

aO

=bYdA + AYdb+AbdY.

From (2.3) and (2.4; wc can derive the rate of growth of employment :

OKI dN^dX , db , dY

which suggests the theoretical possibility and the practical desirability

of increasing the rate of growth of employment through the deliberate

manipulation of the rate of change in the labor-capital ratio (dA/A), and

the rate of change in the capital-output ratio (db/b), and the rate

of growth of output (dY/Y). Thus, when the independent variables

of equation (2.5) are regarded as manipulative policy parameters,

we come that much closer to our goal of continuous full employment.

For the policy scope is greatly enlarged by the explicit introduction of the

flexible labor-capital ratio and the flexible capital-output ratio into equation

(2.5), that is, in addition to the variable rate of growth of output.

To be moreconcrete, the developing economy in question may

endeavor to increase the rate of growth of employment via the selective

encouragement of labor-intensive techniques and industries and other

measures affecting dA/A and via appropriate saving-investment programs,

capital imports, capital-requiring industrialization, and other ways affect

ing db/b as well as via various output-expanding measures affecting

dY/Y. Thus viewed, the moderate expansion of labor-intensive "cottage

industries" along with the gradual expansion of service industries is help

ful to employment growth in the course of generally capital-intensive

economic development.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.129 on Sun, 22 Jun 2014 20:50:02 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

6 PAKISTAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL REVIEW

IV. Full-Employment Dynamic Equilibrium Conditions

foregoing analysis leads us to the following

The full-employment

:

equilibrium condition to be satisfied formally

/i 11 dL dN = n . d* , dP <U , db , dY

(3.1) +

X-_ Q,-+T=T T+T,

-

which implies that if an unemployment gap, dL/L dN/N>0, develops,

it can be wiped out by influencing the independent variables involved.

But equation (3.1) is devoid of any explicit policy parameters.

So let us contemplate two downward shift parameters to be imposed

on the supply side of employment :

v, p = 1. (f= 0, ...,W;TJ, p= lat/ = 0)

(3.2) vt, pt <

Contrariwise, let us contemplate three upward shift parameters to be

:

imposed on the demand side of employment

= ? , fr, H > !. (t

=

0, ..., n ; ?, fr j*- 1at t= 0)

(3.3)

Taking (3.2) and (3.3) into account,

we can rewrite equation (3.1) as

< > + (-0.">

*n^-<r^ r$-

which is the explicitly policy-ariented condition of full-employment dyna

mic equilibrium to be satisfied practically. The policy makers in each

developing economy would have to decide how much less than unity the

downward shiftparameters should be and how much more than unity the

upward shift parameters should be-for the overall purpose of achieving

and maintaining full employment at time t.

The model described by equations (1.1)-(3.4) is meant to be an

alternative to theHarrodian-Robinsonian extension of Keynes' short-run

static theory of employment. That model may have helped to dispel mis

givings about Malthus' dismal "overpopulation" principle and Marx's

pessimistic "reserve army of labor" doctrine. Be that as itmay, I hope

my model will be useful to all the developing economies concerned with

the serious and onerous problem of chronic underemployment.

StateUniversityofNew York KENNETH K. KURIHARA

Binghamton

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.129 on Sun, 22 Jun 2014 20:50:02 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

KURIHARA :MODEL OF FULL-EMPLOYMENT GROWTH 7

REFERENCES

1. Cf. R.F. Harrod, Towards a Dynamic Economics, 1948 ; Joan Robinson, The

Accumulation of Capital, 1956 ; E.D. Domar, Essays in the Theory of Economic Growth,

1957 ; andmy TheKeynesianTheoryofEconomic Development,1959.

2. Harrod, ibid, p. 74.

method see my "The Gap between Actual and

3. For such a transformation

Potential Output in Growing Advanced Economies," inW.A. Eltis, M. F.G. Scott and

J.N.Wolfe (eds.), Induction,Growthand Trade :Essays inHonour of Sir Roy Harrod,

1970.

4. Domar, "Expansion and Employment." American Economic Review, March

1947.

5. Robinson, "Mr. Harrod's Dynamics," Economic Journal, March 1949.

6. Sweezy, "John Maynard Keynes," Science and Society, Fall ; reprinted in

S.E. Harris (ed.), The New Economics, 1948. For one answer to Paul Sweezy's com

plaint that "Keynes ignores technological change and technologicalunemployment"

(ibid) see my "The Antinomic Impact of Automation on Employment and Growth,"

Econom a Internazionale, August, 1969.

7. Robinson, The Accumulationof Capital, 1956 (esp, Book II). For a mathe

matization and interpretation of her verbal model see "Notes on the Robinson Model,"

inmy Keynesian Theory of Economic Development, pp. 73-80.

8. For a detailed discussion of the determinants of the capital-output ratio see

my "Technological Flexibilityand 'Golden age', EquilibriumGrowth," IndianEconomic

Journal, January-March 1967. The variabilityassumption involved in equation (2.2)

above is in sharp contrast with the constancy assumption involved in the Harrod-Domar

model.

This content downloaded from 185.44.78.129 on Sun, 22 Jun 2014 20:50:02 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Juan Negosyante Blank Worksheets by Chinkee TanDocument9 pagesJuan Negosyante Blank Worksheets by Chinkee TanAbby Balendo100% (4)

- Ansoff MatrixDocument4 pagesAnsoff MatrixThrowsdloh83% (6)

- Advac Guerero Chapter 15Document18 pagesAdvac Guerero Chapter 15Drew BanlutaNo ratings yet

- A Domar Model 1946 EconometricaDocument12 pagesA Domar Model 1946 EconometricagkpNo ratings yet

- The Econometric Society Econometrica: This Content Downloaded From 189.6.19.245 On Fri, 04 May 2018 01:29:57 UTCDocument12 pagesThe Econometric Society Econometrica: This Content Downloaded From 189.6.19.245 On Fri, 04 May 2018 01:29:57 UTCAlexander Cotte PovedaNo ratings yet

- The Econometric SocietyDocument12 pagesThe Econometric SocietyTeisu IftiNo ratings yet

- Article 5 PDGS6102Document27 pagesArticle 5 PDGS6102ainul murizaNo ratings yet

- Paper 9ErB6T49Document38 pagesPaper 9ErB6T49Betel Ge UseNo ratings yet

- Capital Expansion, Rate of Growth, and Employment - Evsey D. DomarDocument12 pagesCapital Expansion, Rate of Growth, and Employment - Evsey D. DomarAzzahraNo ratings yet

- Capital Expansion, Rate of Growth, and Employment' Evsey DDocument11 pagesCapital Expansion, Rate of Growth, and Employment' Evsey Djuan camilo clavijoNo ratings yet

- Literature Review UnemploymentDocument6 pagesLiterature Review Unemploymentqdvtairif100% (1)

- Thesis Statement On Economic GrowthDocument5 pagesThesis Statement On Economic Growthvictoriathompsonaustin100% (2)

- Module 3-1 - Campos, Grace R.Document3 pagesModule 3-1 - Campos, Grace R.Grace Revilla CamposNo ratings yet

- Todaro 1969Document12 pagesTodaro 1969sharpie_123No ratings yet

- Kelley 1991Document11 pagesKelley 1991Andrea Katherine Daza CubillosNo ratings yet

- CH - 5 - Theories of Economic DevelopmentDocument16 pagesCH - 5 - Theories of Economic DevelopmentFàrhàt HossainNo ratings yet

- Barro Government SpendingDocument24 pagesBarro Government Spendinging_jlcarrillo8784No ratings yet

- Determinants of Economic Growth Implications of The Global Evidence For ChileDocument37 pagesDeterminants of Economic Growth Implications of The Global Evidence For ChileDavid C. SantaNo ratings yet

- Chapter II. Classic Theories of Economic Growth and DevelopmentDocument3 pagesChapter II. Classic Theories of Economic Growth and DevelopmentJoy DeocarisNo ratings yet

- Economics of Growth and Development, III B.A EconomicsDocument19 pagesEconomics of Growth and Development, III B.A EconomicsArun SubramanianNo ratings yet

- Fellowship. Rodrik's Work Was Supported by An NBER Olin Fellowship. We Thank Naury Obstfeld, Roberto Perotti, TorstenDocument54 pagesFellowship. Rodrik's Work Was Supported by An NBER Olin Fellowship. We Thank Naury Obstfeld, Roberto Perotti, TorstenStéphane Villagómez CharbonneauNo ratings yet

- Plotting The Contours For India's Development FINAL FINAL FINAL FINAL FINALDocument89 pagesPlotting The Contours For India's Development FINAL FINAL FINAL FINAL FINALSujay Rao MandavilliNo ratings yet

- (Kaldor) Productivity and GrowthDocument8 pages(Kaldor) Productivity and GrowthPal SaruzNo ratings yet

- A Microfoundation For Social Increasing Returns in Human Capital AccumulationDocument26 pagesA Microfoundation For Social Increasing Returns in Human Capital AccumulationDevin SantosoNo ratings yet

- Monetary CircuitDocument12 pagesMonetary CircuitiarrasyiNo ratings yet

- The Growth of Nations.Document53 pagesThe Growth of Nations.skywardsword43No ratings yet

- Pas in Etti 1962Document14 pagesPas in Etti 1962Dawn HarrisNo ratings yet

- BOMBACH, G. Manpower Forecasting and Educational PolicyDocument33 pagesBOMBACH, G. Manpower Forecasting and Educational PolicyAndré MartinsNo ratings yet

- Oxford University PressDocument24 pagesOxford University PressCristhian ValladaresNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 - Economic ModelsDocument6 pagesChapter 4 - Economic ModelsSherilyn LozanoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On GDPDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On GDPuyqzyprhf100% (1)

- Chapter 3Document8 pagesChapter 3Jimmy LojaNo ratings yet

- Is Fiscal Policy Contracyclical in India: An Empirical AnalysisDocument14 pagesIs Fiscal Policy Contracyclical in India: An Empirical AnalysisSwastik GroverNo ratings yet

- (IMF Staff Papers) "Human Capital Flight" - Impact of Migration On Income and GrowthDocument31 pages(IMF Staff Papers) "Human Capital Flight" - Impact of Migration On Income and GrowthnurmerlyndajipaNo ratings yet

- Unemployment Insurance in Macroeconomic Stabilization: Rohan Kekre September 2017Document89 pagesUnemployment Insurance in Macroeconomic Stabilization: Rohan Kekre September 2017Fajar NugrahantoNo ratings yet

- Author(s) Amartya K. Sen - Economic Approaches To Education and Manpower PlanningDocument22 pagesAuthor(s) Amartya K. Sen - Economic Approaches To Education and Manpower PlanningRohan AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Baumol 1967Document13 pagesBaumol 1967Juani TroveroNo ratings yet

- Optimal Capital Accumulation and Balanced Growth Paths WAIFEMDocument26 pagesOptimal Capital Accumulation and Balanced Growth Paths WAIFEMErnest OdiorNo ratings yet

- The Contribution of Human Capital To Growth: Some EstimatesDocument38 pagesThe Contribution of Human Capital To Growth: Some EstimatesNico TulaliNo ratings yet

- Health - and - economic - growth (1) -مفتوحDocument62 pagesHealth - and - economic - growth (1) -مفتوحASSIANo ratings yet

- Dual Economy ThesisDocument6 pagesDual Economy Thesisafjvbpvce100% (2)

- The Logic of Economic Development: A Definition and Model For InvestmentDocument17 pagesThe Logic of Economic Development: A Definition and Model For InvestmentAli Nizar Al-AghaNo ratings yet

- MPRA Paper 107787Document22 pagesMPRA Paper 107787SadaticloNo ratings yet

- Human Capital and Economic GrowrthDocument28 pagesHuman Capital and Economic GrowrthJuniebe ManganohoyNo ratings yet

- Transitional Dynamics in Two-Sector Models of Endogenous Growth.Document36 pagesTransitional Dynamics in Two-Sector Models of Endogenous Growth.skywardsword43No ratings yet

- Cuarta MacroDocument30 pagesCuarta MacropeprluchoNo ratings yet

- Mankiw (1995) - The Growth of NationsDocument53 pagesMankiw (1995) - The Growth of NationsAnonymous WFjMFHQ100% (1)

- I. Production Possibility Curve (PPC)Document8 pagesI. Production Possibility Curve (PPC)chetanNo ratings yet

- Development Economics Chapter 3Document11 pagesDevelopment Economics Chapter 3JENISH NEUPANENo ratings yet

- Beinhocker Comment On KLMDS v9 15 20Document15 pagesBeinhocker Comment On KLMDS v9 15 20robertNo ratings yet

- Optimum Theory of Population: An Assignment OnDocument10 pagesOptimum Theory of Population: An Assignment OnHarsh SenNo ratings yet

- Learning InsightsDocument2 pagesLearning Insightsriza utboNo ratings yet

- The Role of InfrastructureDocument11 pagesThe Role of InfrastructureAyey DyNo ratings yet

- 2020desarrollo MundialDocument20 pages2020desarrollo MundialLupita VásconezNo ratings yet

- LiberalArtsAndScienceAcademy LoMe Neg Hendrickson Round 4Document41 pagesLiberalArtsAndScienceAcademy LoMe Neg Hendrickson Round 4EmronNo ratings yet

- Growth and ModelsDocument23 pagesGrowth and ModelsFekadu DuferaNo ratings yet

- Q. What Do You Understands by Effective Demand? Will The Level of Effective Demand Be Always Associated With Full Employment?Document7 pagesQ. What Do You Understands by Effective Demand? Will The Level of Effective Demand Be Always Associated With Full Employment?Rachit GuptaNo ratings yet

- Full Employment Hayek PDFDocument11 pagesFull Employment Hayek PDFAlexandreNo ratings yet

- Og Literature ReviewDocument17 pagesOg Literature ReviewInnocent escoNo ratings yet

- Slide 15: Report 15-17 SlidesDocument4 pagesSlide 15: Report 15-17 SlidesWonwoo JeonNo ratings yet

- Economic DevelopmentDocument7 pagesEconomic DevelopmentMin MyanmarNo ratings yet

- Wiley The Scandinavian Journal of EconomicsDocument20 pagesWiley The Scandinavian Journal of EconomicsAadi RulexNo ratings yet

- Eur28767en 2017-10-06 Km-Report OnlineDocument56 pagesEur28767en 2017-10-06 Km-Report OnlineJuan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- Stata Mini-Course - Session 1Document21 pagesStata Mini-Course - Session 1Juan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- Kjna31169enn 2Document43 pagesKjna31169enn 2Juan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- PSMatchingDocument55 pagesPSMatchingJuan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 11 01682Document18 pagesSustainability 11 01682Juan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- 11 1085 Guidance Evaluating Interventions On BusinessDocument95 pages11 1085 Guidance Evaluating Interventions On BusinessJuan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- StatabasicsDocument16 pagesStatabasicsJuan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- Becker Ichino Pscore SJ 2002Document20 pagesBecker Ichino Pscore SJ 2002Juan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- RECSM wp044Document38 pagesRECSM wp044Juan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- Premere F9 Per Visualizzare Altri Dati: A' B' C' Colum NMDocument9 pagesPremere F9 Per Visualizzare Altri Dati: A' B' C' Colum NMJuan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- Chemometrics in Excel: Alexey Pomerantsev, Oxana RodionovaDocument25 pagesChemometrics in Excel: Alexey Pomerantsev, Oxana RodionovaJuan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- Can 2017Document33 pagesCan 2017Juan ToapantaNo ratings yet

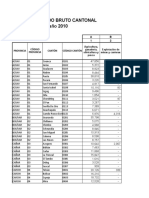

- Valor Agregado Bruto Cantonal Miles de Dólares, Año 2010: A B 1 2 Código ProvinciaDocument48 pagesValor Agregado Bruto Cantonal Miles de Dólares, Año 2010: A B 1 2 Código ProvinciaJuan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- SocNet TheoryAppDocument116 pagesSocNet TheoryAppJosesio Jose Jose Josesio100% (2)

- DW CriticalvaluesDocument95 pagesDW CriticalvaluesJuan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- Can 2007Document31 pagesCan 2007Juan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- Cantidad Demandada: 40 Demanda OfertaDocument4 pagesCantidad Demandada: 40 Demanda OfertaJuan ToapantaNo ratings yet

- Statement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceDocument2 pagesStatement of Account: Date Narration Chq./Ref - No. Value DT Withdrawal Amt. Deposit Amt. Closing BalanceLoan LoanNo ratings yet

- Mini Du Fee PDFDocument1 pageMini Du Fee PDFRajat GuptaNo ratings yet

- Finance and Economics For Engineers MME-308 Kris Harihara Class 4 - Elasticity of DemandDocument7 pagesFinance and Economics For Engineers MME-308 Kris Harihara Class 4 - Elasticity of DemandMadhujya SaikiaNo ratings yet

- Anava Hoyt (Lama)Document7 pagesAnava Hoyt (Lama)Diana Putri AriniNo ratings yet

- DCSL SBD 04-2024 Tender Document Supply and Install 14 High Mask Lighting For KZNDocument78 pagesDCSL SBD 04-2024 Tender Document Supply and Install 14 High Mask Lighting For KZNdavid selekaNo ratings yet

- FABM 2 Learning LogDocument2 pagesFABM 2 Learning LogRea Angela DealcaNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of EconomicsDocument59 pagesFundamentals of EconomicsUwuigbe UwalomwaNo ratings yet

- PRB M3Document4 pagesPRB M3John Alejandro Rangel RetaviscaNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Finance Applications and Theory 5th Edition by Cornett DownloadDocument54 pagesTest Bank For Finance Applications and Theory 5th Edition by Cornett Downloadtammiedavilaifomqycpes100% (29)

- ANOVADocument33 pagesANOVABhatara Ayi MeataNo ratings yet

- DSC1520 2013 S1 Students Assignment 2 PDFDocument3 pagesDSC1520 2013 S1 Students Assignment 2 PDFKhathutshelo KharivheNo ratings yet

- Sandvik: Special Strip SteelDocument18 pagesSandvik: Special Strip SteelKonstruktor d.o.o. FočaNo ratings yet

- Country Dry SinkDocument4 pagesCountry Dry SinkjcpolicarpiNo ratings yet

- Ashford MGT 330 Week 2 Assignment Starbucks StructureDocument2 pagesAshford MGT 330 Week 2 Assignment Starbucks StructureCharlotteNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Working Capital Management at BCCL (Bharat Coking Coal LTD.) A Subsidary of CIL (Coal India LTD)Document29 pagesPresentation On Working Capital Management at BCCL (Bharat Coking Coal LTD.) A Subsidary of CIL (Coal India LTD)Raj VermaNo ratings yet

- Byelaws of The Staff Socials of GTC EnyohDocument4 pagesByelaws of The Staff Socials of GTC EnyohTeghen LesleyNo ratings yet

- 03 Maxilift 17 WsDocument25 pages03 Maxilift 17 WsYhaneNo ratings yet

- Worksheet 10: Probability Grade 11 MathematicsDocument4 pagesWorksheet 10: Probability Grade 11 MathematicsHashim RashidNo ratings yet

- Komatsu Bulldozer d31 d37 Ex PX 21 Shop ManualDocument20 pagesKomatsu Bulldozer d31 d37 Ex PX 21 Shop Manualbilly100% (55)

- Role of Micro-Financing in Women Empowerment: An Empirical Study of Urban PunjabDocument16 pagesRole of Micro-Financing in Women Empowerment: An Empirical Study of Urban PunjabAnum ZubairNo ratings yet

- Excercise IntegrationDocument2 pagesExcercise IntegrationVan Anh PhamNo ratings yet

- Chap 3 Resource Based View of FirmDocument34 pagesChap 3 Resource Based View of FirmAnshuNo ratings yet

- Differentiation StrategyDocument12 pagesDifferentiation StrategyTedtenor75% (4)

- Procuratio: Jurnal Ilmiah ManajemenDocument10 pagesProcuratio: Jurnal Ilmiah ManajemenAndi WidyaNo ratings yet

- Tugas 1 - Elvia Nepina - 120104170093Document6 pagesTugas 1 - Elvia Nepina - 120104170093Angelica Sladica Selvia NevinaNo ratings yet

- 00 Readings For Tut 3Document3 pages00 Readings For Tut 3PeiWen TanNo ratings yet

- Audit Plan ISCC - FGP & Oil Mill - PT Adei Plantation - Nilo 1 POM - To Client - Rev0Document5 pagesAudit Plan ISCC - FGP & Oil Mill - PT Adei Plantation - Nilo 1 POM - To Client - Rev0Teddy KusumaNo ratings yet