Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 38 - Relationships Between Principal and Agent

Chapter 38 - Relationships Between Principal and Agent

Uploaded by

Deaa Gee0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views22 pagesThis document summarizes agency law and the relationships between principals and agents. It discusses how agency relationships are created through agreement or operation of law. It outlines the fiduciary duties agents owe to principals, including duties of skill/care, good conduct, keeping accounts, and acting within authorization. It also discusses implied agency and apparent authority. Finally, it summarizes the duties principals owe to agents, such as contractual duties and the duty to indemnify agents against losses.

Original Description:

Original Title

Chapter 38 - Relationships between Principal and Agent

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document summarizes agency law and the relationships between principals and agents. It discusses how agency relationships are created through agreement or operation of law. It outlines the fiduciary duties agents owe to principals, including duties of skill/care, good conduct, keeping accounts, and acting within authorization. It also discusses implied agency and apparent authority. Finally, it summarizes the duties principals owe to agents, such as contractual duties and the duty to indemnify agents against losses.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views22 pagesChapter 38 - Relationships Between Principal and Agent

Chapter 38 - Relationships Between Principal and Agent

Uploaded by

Deaa GeeThis document summarizes agency law and the relationships between principals and agents. It discusses how agency relationships are created through agreement or operation of law. It outlines the fiduciary duties agents owe to principals, including duties of skill/care, good conduct, keeping accounts, and acting within authorization. It also discusses implied agency and apparent authority. Finally, it summarizes the duties principals owe to agents, such as contractual duties and the duty to indemnify agents against losses.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 22

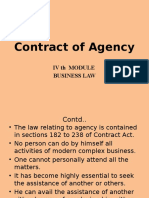

CHAPTER 38

Relationships between Principal and Agent

Introduction

■ An agent is a person who acts in the name of and on behalf of another, having been given and

assumed some degree of authority to do so.

■ Most organized human activity and virtually all commercial activity is carried on through

agency.

■ Corporations could not operate without agency.

■ Partnerships and other business organizations also rely extensively on agents to conduct their

business.

■ In a partnership each partner is a general agent, while in a corporation, officers and

employees are agents of the corporation.

■ The existence of agents does not require a whole new law of torts or contracts.

– A tort is no less harmful when committed by an agent, so agents are liable for their own

torts.

– A contract is no less binding when made by an agent, so principals are liable for

contracts formed by their agents on their behalf.

■ The questions are whether a principal is also liable for an agent’s torts, and whether an agent

is also liable for the contracts they make on behalf of their principals.

Agency

■ Agency law often involves three parties:

– The principal,

– The agent, and,

– A third party.

■ It therefore deals with three different relationships:

– Between principal and agent,

– Between principal and third party, and,

– Between agent and third party.

■ In this chapter, we will consider the principal-agent aspects of the relationships.

Agency Creation

■ The agency relationship can be created by two ways:

– By agreement (expressly), or,

– By operation of law (constructively or impliedly).

Agency Created by Agreement

■ Agencies created by consent are not necessarily contractual. It is not uncommon for one

person to act as an agent for another without consideration.

■ Gratuitous agency gives rise to no different results than the more common contractual

agency, except that the agent has a restricted duty to perform with skill and care.

■ Most oral agency contracts are legally binding – the law does not require that they be

reduced to writing.

■ In practice, many agency contracts are written to avoid problems of proof.

■ A contract is void or voidable when one of the parties lacks capacity to make one.

– If both principal and agent lack capacity, there can be no question as to the

contract’s voidability.

– But suppose only one or the other lacks capacity. Generally, the law focuses on the

principal.

■ If the principal is a minor or otherwise lacks capacity, the contract can be avoided even

if the agent is fully competent; however when the principal has capacity, the contract is

likely enforceable, even if the agent lacks it.

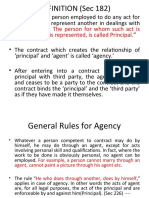

Agency Created by Operation of Law

■ Most agencies are created by contract, but agency can also arise impliedly or apparently.

■ Implied or Apparent Agency:

– In areas of social need, courts have declared an agency to exist in the absence of an

agreement.

– The agency relationship is said to have been implied by operation of law.

– Children in most states may purchase necessary items on the parent’s account, for

example.

■ Long standing social policy deems it desirable for the head of the family to support his

dependents, and the court will put the expense on the family head in order to provide for the

dependents’ welfare.

■ The courts achieve this result by supposing the dependent to be the family head’s agent, thus

allowing creditors to sue the family head for debt.

– Implied agencies also arise when one person behaves as an agent would and the

principal, knowing that the person is behaving as an agent, acquiesces, allowing the

person to hold himself out as an agent.

– The principal will be liable on a contract made by an agent if it appeared to the third

party that the agent was an authorized agent, and the principal somehow contributed to

that appearance of agent authority.

Duties between Agent and Principal

■ Agent’s duty to principal:

– The agent owes the principal duties in two categories:

■ The fiduciary duty, and,

■ The general duties imposed by agency law.

Fiduciary Duty

■ The agency relationship is more than a contractual one, and the agent’s responsibilities

go beyond the border of the contract.

■ Agency imposes a fiduciary duty – the duty of an agent to always act in the best interest

of the principal and to avoid self-dealing.

■ As a fiduciary of the principal, the agent stands in a position of special trust. His

responsibility is to subordinate his self-interest to that of his principal.

■ The fiduciary responsibility is imposed by law. The absence of any clause in the contract

detailing the agent’s fiduciary duty does not relieve him from it. Instead, the contract

would have to specify exceptions to the general fiduciary duty in order to relieve the

agent of them.

Fiduciary duty

■ The duty contains several aspects:

– Duty to avoid self-dealing:

■ A fiduciary may not lawfully profit from a conflict between his personal interest in a

transaction and his principal’s interest in that same transaction.

■ The penalty for breach of fiduciary duty is loss of compensation and profit and possible

damages for breach of trust.

– Duty to preserve confidential information:

■ To further his objectives, a principal will usually need to reveal a number of secrets to

his agent.

■ Such information can be easily turned to the disadvantage of the principal if the agent

were to compete with the principal or were to sell the information to those who do so.

■ The law thus prohibits an agent from using for his own purposes or in ways that would

injure the interests of the principal, information confidentially given or acquired.

■ The agent may not use confidential information after resigning his agency. Though he

is free, in the absence of a contract, to compete with his former principal, he may not

use information learned in the course of his agency, such as trade secrets or customer

lists.

Duty of Skill and Care

■ An agent is usually taken on because he has special knowledge or skills that the

principal wishes to use.

■ The agent is under a legal duty to perform his work with the skill and care that is

standard in the locality for the kind of work which he is employed to perform and to

exercise any special skills, if these are greater or more refined than those prevalent

among those normally employed in the community.

■ In short, the agent may not lawfully fail to do the work, or do a bad job.

■ However, if the Agency is gratuitous, that is, the agent is not paid, then the agent can

lawfully refrain from taking any action on behalf of the principal.

Duty of Good Conduct

■ In the absence of an agreement, a principal may not ordinarily dictate how an agent must

live his private life.

■ There are some jobs on which the personal habits of the agent may have an effect. The

agent is not at liberty to act with impropriety or notoriety, so as to bring disrepute to the

business in which the principal is engaged.

Duty to Keep and Render Accounts

■ The agent must keep accurate financial records, take receipts, and otherwise act in

conformity to standard business practices.

Duty to Act Only as Authorized

■ However, only conduct which is contrary to the principal’s clear instructions to him,

interpreted in light of what he has reason to know at the time when he acts, subjects the

agent to liability to the principal.

No Duty to Attempt the Impossible or

Impracticable

■ The principal may wish the agent to keep working until the job is done, but the agent is

not obligated to go without food or sleep because the principal misapprehended how

long it would take to complete the job.

■ Nor should the agent continue to expend the principal’s funds in a quixotic (hopeless)

attempt to gain business, sign up customers, or produce inventory when it is reasonably

clear that such efforts would be in vain.

Duty to Obey

■ The agent must obey reasonable directions concerning the manner of performance.

■ What is reasonable depends on:

– The customs of the industry or trade,

– Prior dealings between agent and principal, and

– The nature of the agreement creating the agency.

Duty to Give Information

■ Because the principal cannot be every place at once, much that is vital to the principal’s

business first comes to the attention of agents.

■ If the agent has actual notice or reason to know of information that is relevant to matters

entrusted to him, he has a duty to inform the principal.

■ This duty is especially critical because information in the hands of an agent is, under

most circumstances, imputed to the principal, whose legal liabilities to third persons may

hinge on receiving information in a timely manner.

■ The imputation to the principal of knowledge possessed by the agent is strict – even

where the agent is acting adversely to the principal’s interests, a third party may still rely

on notification to the agent, unless the third party knows the agent is acting adversely.

Principal’s Duties to Agent

■ The principal owes the agent duties in contract, tort, and statutorily, workers’

compensation law.

■ Contract duties:

– The fiduciary relationship of agent to principal does not run in reverse – the

principal is not the agent’s fiduciary.

– Nevertheless, the principal has a number of contractually related obligations toward

his agent.

– General contract duties:

■ A principal has a duty to refrain from unreasonably interfering in an agent’s work.

■ The principal is allowed, however, to compete with the agent unless the agreement

specifically prohibits it.

■ The principal has a duty to inform his agent of risks of physical harm or pecuniary loss

that inhere in the agent’s performance of assigned tasks. Failure to do so can subject

the principal to liability for damages in case of the agent’s harm.

Principal’s Duties to Agent

– General contract duties (cont’d):

■ A principal is obliged to render accounts of monies due to agents, with the obligation

depending on a variety of factors, including:

– The degree of independence of the agent,

– The method of compensation, and,

– The customs of the particular business.

■ An agent’s reputation is no less important than a principal’s, and thus, the agent is

under no obligation to continue working for one who damages it.

■ Employment at will:

– Under the traditional employment at will doctrine, an employee who is not hired

for a specific period can be fired at any time and for any reason.

Principal’s Duties to Agent

■ Duty to reimburse:

– Agents commonly spend money pursuing the principal’s business.

– Unless the agreement explicitly provides otherwise, the principal has a duty to

reimburse the agent for money outlaid in pursuit of the goals of the agency.

■ Tort and workers’ compensation duties for employees:

– The employer owes the employee – any employee, not just an agent – certain statutorily

imposed tort and workers’ compensation duties.

– Historically, workers who were injured or killed on the job found themselves or their

families without recompense due to three common law rules:

■ The fellow servant rule states that an employer is not held to be responsible for torts

committed by one employee against another.

■ Contributory negligence bars recovery when an employee is also negligent.

■ Assumption of risk indicates that if an employee is aware of the dangers and still takes an

action, it would be unfair to saddle the employer with the burden of the employee’s actions.

– Union pressure and grass roots lobbying led to workers’ compensation acts – statutory

enactments that dramatically overhauled the law of torts as it affected employees.

• Workers Compensation

– Workers’ compensation is a no fault system. The employee gives up the right to sue the

employer (and in some states, other employees) and receives in exchange

predetermined compensation for a job-related injury, regardless of who caused it.

– This trade-off was felt to be equitable to employer and employee.

– The employee loses the right to seek damages for pain and suffering but in return can

avoid the time-consuming and uncertain judicial process and assure himself that his

medical costs and a portion of his salary will be paid promptly.

– The employer must pay for all injuries, even those for which he is blameless, but in

return he avoids the risk of losing a big lawsuit, can calculate his costs actuarially, and

can spread the risks through insurance.

– Most workers’ compensation acts provide 100% of the cost of a worker’s

hospitalization and medical care necessary to cure the injury and relieve him from its

effects.

– They also provide for payment of lost wages and death benefits.

– Even an employee who is able to work may be eligible to receive compensation for

specific injuries.

– The injured worker is typically entitled to two-thirds his or her average pay, not to

exceed some specified maximum, for 200 weeks. If the loss is partial, the recovery is

decreased by the percentage still usable.

Compliance with Workers’ Compensation

Laws

■ There are three general methods by which employers may comply with workers’

compensation laws:

– They may purchase employer’s liability and workers’ compensation policies through

private commercial insurance companies.

■ The policies consist of two major provisions:

– Payment by the insurer of all claims filed under workers’ compensation and related

laws, and,

– Coverage of the costs of defending any suits filed against the employer, including any

judgments awarded.

■ Since workers’ compensation statutes cut off the employee’s right to sue, how can such a

lawsuit be filed? This is because there are exceptions to the ban, such as if the employer

deliberately injures an employee.

– The may insure through a state fund established for the purpose.

– They may self-insure.

■ The laws specify conditions under which companies may resort to self-insurance, and

generally only the largest corporations qualify to do so.

You might also like

- SC3 SSP Declaration 230821 124728Document2 pagesSC3 SSP Declaration 230821 124728FlAko Hernandez VillegasNo ratings yet

- Essential Elements of AgencyDocument20 pagesEssential Elements of AgencyMichelle Gozon100% (3)

- RMIPA Port Master PlanDocument362 pagesRMIPA Port Master Planjoncpasierb100% (6)

- Business Studies Wiley and SonsDocument534 pagesBusiness Studies Wiley and SonsNate100% (1)

- Termination of Employment PolicyDocument9 pagesTermination of Employment PolicyKirubakaran ShanmugamNo ratings yet

- Business Law Chapter 5Document34 pagesBusiness Law Chapter 5ماياأمال100% (1)

- Law of Agency in Malaysia (Lecture 14) (Autosaved)Document25 pagesLaw of Agency in Malaysia (Lecture 14) (Autosaved)Kenneth Wen Xuan TiongNo ratings yet

- Agency NotesDocument32 pagesAgency NotesPRAKHAR GUPTANo ratings yet

- Law of AgencyDocument51 pagesLaw of AgencybulihNo ratings yet

- L3 - Law of AgencyDocument17 pagesL3 - Law of AgencyaseliNo ratings yet

- Chapter 32Document6 pagesChapter 32softplay12No ratings yet

- Contract of Agency: Rights and Duties of Agent and PrincipalDocument12 pagesContract of Agency: Rights and Duties of Agent and PrincipalGarvitNo ratings yet

- The Law of Agency & Elements of The Law of E-CommerceDocument76 pagesThe Law of Agency & Elements of The Law of E-CommerceKatrina EustaceNo ratings yet

- Lecture No. 4 Agency: Meaning of Agency Definition of "Agent"Document42 pagesLecture No. 4 Agency: Meaning of Agency Definition of "Agent"AlviNo ratings yet

- Special Contracts-5Document18 pagesSpecial Contracts-5Sachin DhoniNo ratings yet

- AGENCYDocument86 pagesAGENCYKarla Mari Orduña GabatNo ratings yet

- Agency What Is An Agency?Document7 pagesAgency What Is An Agency?Vasanthi DonthiNo ratings yet

- Authority of The AgentsDocument27 pagesAuthority of The AgentsLulwa Alsheikh100% (1)

- ASSIGNMENT VI ContractDocument6 pagesASSIGNMENT VI ContractRiya SinghNo ratings yet

- LAW AssignmentDocument5 pagesLAW AssignmentPrasanna KumarNo ratings yet

- Agencies Under Indian Contract Act by AnjuDocument15 pagesAgencies Under Indian Contract Act by AnjuQueenNo ratings yet

- Module IV Contract of AgencyDocument30 pagesModule IV Contract of AgencyAnish IyerNo ratings yet

- Agency Contacts: by S.Bharathwaj Deepika SrinivasanDocument10 pagesAgency Contacts: by S.Bharathwaj Deepika Srinivasanloverboyremo100% (1)

- Agency - Finer Details in The Indian ContextDocument6 pagesAgency - Finer Details in The Indian ContextKumar NaveenNo ratings yet

- Contract of AgencyDocument5 pagesContract of AgencylavinNo ratings yet

- Week 10 - Agency Guiding QuestionsDocument6 pagesWeek 10 - Agency Guiding QuestionsNathalie ChahrourNo ratings yet

- AGENCYDocument154 pagesAGENCYAdityaSharmaNo ratings yet

- Question Bank Answer: UNIT 3: Contract of AgencyDocument6 pagesQuestion Bank Answer: UNIT 3: Contract of Agencyameyk89100% (2)

- The Law of Agency and Elements of The Law of Electronic CommerceDocument76 pagesThe Law of Agency and Elements of The Law of Electronic CommerceShirdah Agiste100% (1)

- AgencyDocument5 pagesAgencySha MatNo ratings yet

- Chapter One: Amanze Donatus UchechukwuDocument11 pagesChapter One: Amanze Donatus UchechukwuAmanze Donatus UcheNo ratings yet

- Mercy 2 ReportDocument6 pagesMercy 2 Reportmercy babaNo ratings yet

- DEFINITION (Sec 182) : The Person For Whom Such Act Is Done, or Who Is Represented, Is Called PrincipalDocument36 pagesDEFINITION (Sec 182) : The Person For Whom Such Act Is Done, or Who Is Represented, Is Called PrincipalUtkarsh SethiNo ratings yet

- Notes Chapter 7 REGDocument9 pagesNotes Chapter 7 REGcpacfa100% (6)

- Business Law Exam 3 ReviewDocument13 pagesBusiness Law Exam 3 ReviewShoma GhoshNo ratings yet

- Unit 2: Law Relating To Special ContractsDocument23 pagesUnit 2: Law Relating To Special ContractsAyesha AzharNo ratings yet

- Agency LawDocument7 pagesAgency LawCarol MemsNo ratings yet

- AgencyDocument5 pagesAgencyPepa JuarezNo ratings yet

- DixitDocument10 pagesDixitDixiT SharmANo ratings yet

- HW 20501Document17 pagesHW 20501Harshita AndaniNo ratings yet

- Agency LawDocument37 pagesAgency LawsoniegayeNo ratings yet

- Nov 14. Chapter 13 - AgencyDocument5 pagesNov 14. Chapter 13 - Agencyzachiechan3No ratings yet

- Short Report On Contract of Agency: Course Code: BUS 361 Section: 1Document3 pagesShort Report On Contract of Agency: Course Code: BUS 361 Section: 1Saief AhmedNo ratings yet

- Contract Agency-Employee: LAB PresentationDocument24 pagesContract Agency-Employee: LAB PresentationMohan Singh SikarwarNo ratings yet

- Agent, Agency & Agreement: By: Ahsan Naeem Lone Anaa Rafique M.Zubair Nasir Sobia Sarwar Urooj ZawwarDocument17 pagesAgent, Agency & Agreement: By: Ahsan Naeem Lone Anaa Rafique M.Zubair Nasir Sobia Sarwar Urooj ZawwarahsanloneNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Contract of AgencyDocument46 pagesUnit 1 Contract of AgencyDeborahNo ratings yet

- Contract of AgencyDocument30 pagesContract of AgencyRiyaNo ratings yet

- THC 107 - Finals 3Document2 pagesTHC 107 - Finals 3KIAN ANGELA LACSONNo ratings yet

- BBA170-FPD-5-2018-1.pptLAW OF AGENCYDocument59 pagesBBA170-FPD-5-2018-1.pptLAW OF AGENCYdanielNo ratings yet

- ASSIGNMENT VI Contracts MehulDocument4 pagesASSIGNMENT VI Contracts MehulRiya SinghNo ratings yet

- Contract of AgencyDocument90 pagesContract of AgencyAadhitya NarayananNo ratings yet

- Law of AgencyDocument11 pagesLaw of Agencyprabharun18No ratings yet

- Law of Agency.Document19 pagesLaw of Agency.Latha Dona VenkatesanNo ratings yet

- Rache AlDocument11 pagesRache AlStephanie Ewurabena AidooNo ratings yet

- Agency: Discretion in Accomplishing The Objectives of TheDocument36 pagesAgency: Discretion in Accomplishing The Objectives of TheAnkit MrCub PatelNo ratings yet

- Agency RelationshipDocument11 pagesAgency RelationshipHärîsh KûmärNo ratings yet

- Contract of Agency: EssentialsDocument7 pagesContract of Agency: EssentialsDevasish PandaNo ratings yet

- Duties and Authority of PrincipalDocument9 pagesDuties and Authority of Principalfadilahmuhidi0% (1)

- Unit 1 - Part 2Document29 pagesUnit 1 - Part 2sourabhdangarhNo ratings yet

- 6 Agency Summary 2Document4 pages6 Agency Summary 2maria fernNo ratings yet

- Agency, ContractsDocument154 pagesAgency, ContractsKahmishKhanNo ratings yet

- Law of AgencyDocument28 pagesLaw of AgencyBenjamin EliasNo ratings yet

- Agency NotesDocument6 pagesAgency NotesFrancis Njihia Kaburu100% (1)

- Seasonal Job Vacancy Notice: City of New York Parks & RecreationDocument7 pagesSeasonal Job Vacancy Notice: City of New York Parks & RecreationAndyTomasNo ratings yet

- Ba8202 Business Research MethodsDocument5 pagesBa8202 Business Research MethodsAnbuoli ParthasarathyNo ratings yet

- Associate Attorney ResumeDocument4 pagesAssociate Attorney Resumef1vijokeheg3100% (2)

- Key Result AreasDocument7 pagesKey Result AreasAasif MansuriNo ratings yet

- OSH Legislation Part 1 8 Mac 2014Document78 pagesOSH Legislation Part 1 8 Mac 2014soqhNo ratings yet

- Administrative Tribunals in IndiaDocument19 pagesAdministrative Tribunals in Indiapermanika100% (2)

- Objectives of Performance ManagementDocument8 pagesObjectives of Performance ManagementMUHAMMED YASIRNo ratings yet

- Case Study AnwerDocument25 pagesCase Study AnwerMabvuto PhiriNo ratings yet

- Job Interview Preparation Info-Graphic Directions: © 2020 Career and Employment PrepDocument4 pagesJob Interview Preparation Info-Graphic Directions: © 2020 Career and Employment PreppatriciaNo ratings yet

- Final-EDMAN204-CN9040 (Group 1 - Report)Document131 pagesFinal-EDMAN204-CN9040 (Group 1 - Report)Edilberto PantaleonNo ratings yet

- Hvac Technician Cover Letter ExamplesDocument5 pagesHvac Technician Cover Letter Examplesf633f8cz100% (2)

- Bsci Audit Questionnire PDFDocument38 pagesBsci Audit Questionnire PDFSama88823100% (1)

- Salesforce Brochure India 2020Document14 pagesSalesforce Brochure India 2020TestNo ratings yet

- BibliographyDocument473 pagesBibliographyMr M100% (2)

- VP Director Operations Manufacturing in Chicago IL Resume Erik PetersonDocument2 pagesVP Director Operations Manufacturing in Chicago IL Resume Erik PetersonErikPeterson1No ratings yet

- February 9, 2015Document12 pagesFebruary 9, 2015The Delphos HeraldNo ratings yet

- Business Case TemplateDocument6 pagesBusiness Case TemplateAbdul Wajid Nazeer CheemaNo ratings yet

- Nebosh National Certificate: Consultation With EmployeesDocument13 pagesNebosh National Certificate: Consultation With EmployeesFidelis BasseyNo ratings yet

- Consulting Report Template 03Document16 pagesConsulting Report Template 03DragNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Organizational Behavior Bridging Science and Practice Version 3 0Document28 pagesTest Bank For Organizational Behavior Bridging Science and Practice Version 3 0Jesus Carter100% (39)

- Warehouse Supervisor Resume SampleDocument7 pagesWarehouse Supervisor Resume Samplesyn0wok0pym3100% (2)

- Labor II Full Cases LastDocument158 pagesLabor II Full Cases LastDanica Irish RevillaNo ratings yet

- Excercise 7 EmpDocument3 pagesExcercise 7 EmpTorchbearer 143No ratings yet

- Batch After Midterm 2015 Labor RelationDocument76 pagesBatch After Midterm 2015 Labor RelationAtty JV AbuelNo ratings yet

- 4 MsDocument19 pages4 MsMaryrose VasquezNo ratings yet

- ESL Roleplay Cards Advanced Intermediate 1Document2 pagesESL Roleplay Cards Advanced Intermediate 1Wessam D. ElshatawyNo ratings yet