Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Murdock y List On

Murdock y List On

Uploaded by

JOSE DAMIAN LOPEZ VASQUEZCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Murdock y List On

Murdock y List On

Uploaded by

JOSE DAMIAN LOPEZ VASQUEZCopyright:

Available Formats

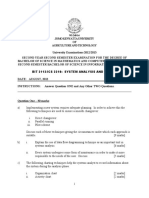

A General Model of Information Transfer:

Theme Paper 1968 Annual Convention

A general model of information transfer establishes a and information centers. Suggested areas for response

conceptual framework for contributed papers for in the form of contributed papers Include costs, per-

the 1968 ADI Convention in Columbus, Ohio, October formance, benefits, functions, application of scientific

20-24, 1968. The general model is an elaboration and technical disciplines, research, vocabulary con-

on the classic sender/channel/receiver model and trol, and language processing associated with in-

presents a variety of alternative channels for informa- formation systems, science, and technology. A call

tion transfer including direct transfer, primary re- for papers for the 1968 ADI Convention is included.

corded media, archives, secondary recorded media,

JOHN W. MURDOCK and

DAVID M. LISTON, JR.

fiallelle Mcmnnnl Institute

Columbu.9 Laboratories

Columbus, Ohio

• Prologue related with the theme will become the convention con-

tributed papers. Other papers of high quality judged to

Inrormatiun Tnm.^fcir!!—That's the theme of the 1968 be of interest to ADI members will provide the content

Convention of the American Documentation Institute to for the author forums. Thus, the following theme paper

be IK'UI in Columbus, Ohio, Octoljcr 2()-'24, liKW. heralds the call for papers for the 1968 ADI Conven-

The tcchiiiral roniniiftee of the convention believes that tion. Speeific suggestions appearing throughout the text

most authors r('])ortiug on information work and research for responding papers are set in italics to bring them

iiclirve (hat their olTorts will in some way improve the bi to the reader'? attention.

transfer of inl'ormation. Thi^ committee jilaus to use this

common interest to give a special coherence to both the

convention and the published proceedings. The plan is • Introfluction

to establish a conceptual structure for the technical pro-

gram in the form of a general model presented in the Inherent in at least one set of definitions of the

following "theme paper" ou inforniatiou transfer. It is words "knowledge" and "information" is the concept

conceived that authors will be able to respond within that an item of knowledge becomes an item of informa-

their own specifi<- areas 10 the broail structure ('stal.)lishf'd tion when it is "set in motion"—when it enters the

by the general nKxlel. To foster this process, the theme active ])rocess of being communicated or transferred

l)aper presents the general model and poses questions from one or more persons, groups, or organizations

about many of the specific problem areas contained there- (sender) to one or more other persons, groups, or or-

in. Its purpose is to promote thought and response ganizations (receiver). Many people will argue that

ill the form of contributed papers which will provide knowledge as defined here has no intrinsic value—that

the backbone of the technical program and be logically only when it is .successfully transferred is its value to be

interrelated by the structure of the general model. Each realized. Others go further, arguing that the value of

contributing author will be requested to introthice his infoiTOation cannot be realized until it is actively ap-

paper with a de.seription of the correlation between the plied in decision making. Either of these viewpoints

model and his specific sulijeet area. Papers highly cor- must necessarily concede that vdtie is dependent upon

American Documentation — Oetolier 1967 107

transjer. Thus, information transfer i^ ;in imi)ortant and '•i. Frecjuent acceptability of vague generalization.^*

appropriate theme for the 1968 American Documentation which would not be permitted in a recorded

Institute Convention. Thi.s theme paper presents a jien- mes.sage.

eralized model of infonnation transfer to >iet the stajje Progressing from the point of facc-to-face discussion

for the convention's technical program. The initial eaii along the communication continuum toward situations

for papers is included as the final section. Some person.^ involving less directness, less dynamic transfer, and more

may uni^h to respojid to the call for papers by explorvui time delay, one can visualize situations such as phone

the idea oj value being dependent 07i transfer. conversations, television liroadcasting, and radio broad-

casting. All of these types of transfer are signified by

the direct channel from the firiginator to user depicted

• The General Model in the general model.

The Primary Recorded Media Channel. Eventually

Figure 1 presents graphically the general model of the point is reached where the originator feels that what

infomiation transfer. It is immediately obvious that the he has to say should be recorded as part of the body

model is based on the clns,*ic sender channel receiver of literature of his di.'^cipline. This publication is usually

concept. In this case, there is a variety of alternative thought of as the primary literature dealing with current

channels. topics. Until the paat 5 years, little was done to package

priinar\' literature for retrospective searching other than

T H E V.Mtit'iT OK providing periodic indexes. Probal)ly much more could

AND THE C O M MX" NIC ATI ON CoNTINITM be done to make it readily retrievable. It is hoped that

Commiinicntion lictween sender and receiver can occur someone will consider writing on this snbject in response

at a number of levels along what is referred to as the to this -paper. Other examples of primary recorded

"communication continuum." This also was called the metlia are letters, newspa])ers, conference notes, technical

'•feedback dimension" liy Lawrence Berul (1). The au- reports, handbook.^, monographs, texts, patents, and

thors belie\'e the general model in Fig. 1 includes every tapes. Each of these media is vorthy of papers on

type of rommunication channel for information transfer. information transfer.

The value of the model is in the jjos^r^ible orientation or The Archival Channel. Because the user is not always

perspective that it provides for authors to say "Here is sensitized to the fiow of messages through the more

where my specialty lielp.s in the information transfer." current channels, the archival channel has developed to

For example, in the .situation of an individual who writes store information for subse(iuent delayed u.sage when the

himself a note, the note is the primary recorded medium user becomes aware of a need for it. Document depots,

and his file of notes (or desk top or drawer) is the libraries, special libraries, and corporate files are all

archive. He becomes the user when he wishes to retrieve forms of archival .storage. Continued reporting of re-

the note. Sophistication is added when .several people search on improvement of archives ia hoped for an i)iput

prepare reports or write memos and the archives become to the lOGS Convention.

a central file. Further, complexity is added when the The Secondary Recorded Media Channel. The next

media include reports from outside the organization channel for the transfer of information involves the

such as published literature. The archives now comprise secondary sources or media. It feeds from iioth the

a library or its equivalent. It is possible similarly to primary recorded media and archives and also becomes

relate other information work to the model. archival when collected into libraries and other holdings.

The Direct Channel. One extreme of the communica- The piirpo.se of the seeondary recorded media channel

tion continuum (included in the direct, nonrecorded is to assist people to search, more easily, an ever increas-

transfer channel of the model) is face-to-face discu.-if^ioii ing volume of current anil stored information for itein.s

in which communication is: of interest. Secondary media such as abstract journals,

1. Very direct. accessions liulletins, indexes, and bibliographies are faced

2. Very dynamic, jiermitting the utilization of: with increasing volumes of literature and with pressure

• words, phrasK-, sentences, etc. )lan[>;uaKel ; to reduce the time period for funnelling information

• gesticulations: from the other channels into the secondary media chan-

• inflections of the voice; nel. This has increased costs sufficiently to make people

• interruptability, allowing the receiver to inter- ([uestion whether value received is worth the cost. This

nipt the sender requesting clarification of or

c'luboration on the message being sjioken; controrer.-iii could lead to nmny iritcrt'sting papers.

• feedl)ack, allowing the receiver to become t!ic The Information Center Channels. Infonnation cen-

sender with rever.Hi flow of information transfer: ters have increased in importance in the past 10 years.

3. Very ra[)id, with virtually no delay time involved. They represent an attempt to provide a sen'ice to es-

Disadvantages primarily relate to: sentially a known group of users upon demand. The

information analysis center, in particular, attempts to

1. Faulty memory: utilize all infonnation transfer channels to provide tech-

2. Little chance f'or study of what is transferred;

.American DocumiMitation — October 1967

ORIGINATOR

PEOPLE DIRECT NONRECORDED TRANSFER

SENSORS SENSORS

MACHINES MACHINES

PRIMARY

RECORDED MEDIA

SECONDARY

RECORDED MEDIA

INFORMATION

CENTERS

INFORMATION

CENTERS

FIG. 1. Cieneml model of information triiii.^

American Domnirntation — Ortohnr 1007 109

nical an.swcr!; to technical questions po^cd by users. to future. This jirobiem is es])ecially important to the

Thinking in terms of an electrical analogy to the model, individual as he promises himself to return eventually

information centers act as "switching centers" utilizing to an item oiiserved in the current literature which

the "circuitry" of the channels in the most appropriate cannot be read currently for any of a number of reasons.

combination of series and parallel arrangements. In a generalized model of information systems, M. C.

The concept of analysis centers ha? been applied pri- Yovits and Ii. L. Ernst of The Ohio State University also

marily to technical disciplines and mission-oriented depict a. cyclic flow. (4) In the Yovits/Ernst model

projects. Heports oj applications of the analysis center (Fig. 2) the decision making fimction is analogous to

concept to the social, political, and economic fields would the originator/user elements of the model in Fig. 1. The

be of interest for the 19(^8 Convention. The finictioii.'^ types of originators/users represented in the Fig. 1 model

and servicfip of analysis centers were first described by include:

G. S. Simpson {'3) at the 1061 Boston ADI Annual Meet-

lndi\'idual i)eople Nonprofit?

ing. The symbol used in Fig. 1 to represent information Individual .censors Universities

centers was presented at that time and has been used hidi\'idual machines Professional societies

in several conierenccs and pai^ers since 1001. The three Industrial corporation^ Federal Government

parallel segments of the symbol represent the jirimary Nor-for-protits State Clovernment

functions of the analysis center as described l.>y Simpson.

The top segment rejiresents the acquisition function; the K RKSTRTCTIONS

middle segment represent? the storage and retrieval func-

tion; and the liottom segment represents the primary Regardless of the type of channel utilized in trans-

function, analysis. In analysis centers as much as SQ^/i ferring a message, there are certain release restrictions

of the budget is spent for the analysis of informatiou by which will impe(ie the "fre*;" transfer of information

experts. The Special Interest C>roup of ADI on Analysis from originator to user. Returning to our electrical

Centers is another recognition of the analysis center as analogy, these release restrictions would be much like

an established activity in information transfer. Dr. resistances or impedances in the circuits connecting the

Chalmers Shorwin said at the National Symposium on originators to the users. Furthermore, the total resistance

"Putting Information Retrieval to Work in the OlHce'' to fiow would probably vary according to whether the

on May 9, 19(i7, and in a ]iaper (.J) discussed at that resistances in the channels were applied in series or in

mceliug that he felt that the analysis center concept parallel or in combinations of both.

would provide the answer to the national information Everyone seems willing to grant that release restric-

problem for at least the next generation. This statement tions are real phenomena. Even at the level of face-to-

might prompt some responses which would be of interest face comnumicatioiis, they exist in such forms as lan-

at the 1968 Convention. guage difficulties, personal reluctances to divulge facts,

The more often used expression, "information center." and personal incapabilities of expression. Release re-

also has as its main characteristic the response to a strictions become more noticeable as the contact be-

customer on demand. However, the information center tween sender and receiver becomes jirogressively less

i? distinguished from the information anahjsis center (lirect—less face-to-face. One often iloes not write in a

primarily by the lesser degree of analy.'^is performed. letter or say on the phone what he would say face-to-

Information centers respond to inquiries more sjjecifically face. Thus, even though the release restrictions are not

than librarie.--. For example, information centers often overtly a]jplied, there is tacit adoption of restrictions

repackage information and often publish the new ]iack- as the contact between sender and receiver becomes

age. The primary functions of information centers are more remote. But, there is nuich we do not under-

acquisition, storage/retrieval, and direct responses to stand about tliis impedance:

customer's retjuests resulting in some publishing of

special reports. Many hardware and system designers 1. What is the magnitude of the impedance?

have worked on ]irol.>lems associated with improving What percentage of valual)le information is not

information centers. Papers on all facets of methods

and mechanisms to improve the operations of informa-

tion renters are encouraged by the Committee.

CYCLIC N.ATUIU: OV TI{.ANSFKK mou

ORIGINATOR TO USER I..-

'•/.., n^

In a gross sense at least, the entire information trans-

fer model is cyclic in that users (as a group) are the

same people, sensors, or machines as the originators (as

a group). Even an individual has the ])roblem of com-

municating with himself across the time span of present FIG. 2. Generalized information system model i4)

2(10 American Documentation — October 1967

available to certain people because of security total field of information which apphes to the scope

classifications, for example ? and mission of a system. Performance includes a

2. How critical is the impedance? To what extent measure of the completeness of coverage of that portion

does it really impair progress and understanding? of information.

3. What possibilities are there for reducing or com- 2. Usage—the extent to which the system sen-es all

pensating for the impedance? the information needs existing within its scope and

4. How justifiable are these impedances in view of the mission. There is inherently defined a theoretical finite

value of information—or do they exist because of portion of the total need for information which is

the value of information? able to be satisfied by the system. Performance in-

cludes a measure of the completeness of satisfaction

Improved insight on these and related topics wovld he of that portion of the total information need.

very worthwhile. Consideration might be given to the 3. Accuracy—the degree of perfection with which

follomng different levels of restrictions (5) .• the system can fit applicable information to specific ex-

(1) Unclassified/Public Domain, (2) Unclassified/ pressions of need. This factor involves the familiar

Copyrighted, (3) Personally Confidential, (4) Proprie- measures of relevance and recall.

tary, (5) Security Cla.ssified, (6) Natural Language Dis- 4. Speed—the speed with which the system can

perform its functions.

crepancy, (7) Personal limitations in written or verbal 5. Output Quality—quality of products and/or ser-

expression. (8) Expen.^e {costs). vices offered to the system users.

Benefits. The term "benefits," is expressible in tenns

such as:

• Some Specific Areas for Rei^ponse

1. The extent to which all inadvertent duplication of

With the general model of information transfer serving effort can he prevented.

as the underlying logical structure, a great many areas 2. The extent to which the planning and decision-

making functions of any organization can be

are made available for consideration. This section of the improved.

theme paper attempts to provide some preliminary in- 3. The extent to which synthesis of new ideas can

roads to some of these subject areas with the objective be fostered through the niani]")iilation and ob-

of promoting development of a full spectrum of papers servation of information contained in an informa-

on specific topics within this general framework. Such tion system.

papers will be the heart of the technical program of the From the above definitions we see that performance

1968 ADI Convention. The following discussions are not of a sy.^tem is a function of factors internal to, or con-

primarily to inform but rather to prompt thought and trollable by, the system. This is in contrast to the factors

to invoke response. Authors may wish to discuss con-

bearing on benefits. These are external to or beyond the

cepts that can apply at any point or combination of

control of the information system.

points in the transfer spectrum. A host of ideas for

papers is inherent in our previous presentation of the Cost-Performance Relationship. Figure 3 depicts the

general model of information. Some areas worthy of relationship between cost and performance. Our

additional specific mention are:

Cost/Performance/Benefit Interrelationships

Functions Performed Within the Channels

Scientific and Technical Disciplines Involved in In-

formation Science and Technology

Current Areas of Research

\'ofabulary Control/Language Processing

Optimum Channel Utilization.

COST/PEHFOKMANCE/BENEFIT INTERRELATIONSHIPS

.As a sounding board for further discussion, we offer the

foUomng hypotheses concerning the interrelationships

between costs, performaitce, and benefits of information

systems. The term, costs, in this discussion simply refers

to the costs involved in operating an infonnation system.

However, the clear definition of the other two terms is

more critical to a clear understanding of the following

discussion.

Performance. Tlie term, performance, comprises the

comi)ination of five factors:

100

1. Coverage—the extent to which an information Percentage of Maximum Possible Perfoimance Level

system covers all applicable information. There is

inherently specified a theoretical finite portion of the FIC. 3. Cost-performance relationship

American Documentation — October 1067 201

,-ents the relalioni^hip between all three variables by

plotting the benefit to cost ratio against performance.

The benefit to cost ratio is similar in concept to return

on investment. The shaded area represents conditions

under which no information syi^Ieni shouiil operate, lie-

cause in this area it always costs more to operate the

system than can be derived from it in the form of bene-

fits. Curve C depicts an information system in a situation

where there is no level of performance at which it can

ojjerate to prothice a positive return on investment. Such

a system would be completely unjustifiable. To operate

optimally would be to operate at that level of perform-

ance (Point R) at whicli the sy^^tem nchicves the maxi-

mum benefit to cost ratio (Point X).

Cost-Performance Optimization. I n Fig;, fi, if C u r v e A

represents the cost-performance relationship of an exist-

ing system, attempts at improving the system design

toward optimum conditions (or de.^igning the optimum

system) can l)e represented as trying to "dent-in" the

Percentage of Maximum Possible Perfotmance Level

curve to arrive at a curve more like Curve B. This

FIG. 4. Bcucfit-pfjiforuiance relationship "denting-in" of the cost/performance curve can be ac-

comphshed by; 1. Devising ways to decrease costs with-

esis (Iffinr? two basic pharaftrrifitics of the interreia- out decreasing; performance (as in moving from Point 1

tionship: to Point 2) in Fig. 6. 2. Devising ways to improve

performance without increasing costs (as in moving from

1. At zero performance level, the cost of operatinf; Point 1 to Point 3) 3. Devisin<r improvements which

the sy.-^tpm is also zero.

2. As the ])erformance level approaches lOO^t, the combine Items fl) and (2), above la.-^ in moving from

cost of operating the system approaches in- Point 1 to Point 4).

finity.

Benefit-Cost-Performance Optitnizntion. In Fig. 7, if

Benefit-Performance Relatiotiship. The relationship Cur\'e A represents the relationships for an existing sys-

between benefits and performance \^ yliown in Fig. 4. tem, then attempts at improvitiif; thn system toward

Af; the performance level increases, there will be a

optimum conditions can be represented Ha trying to in-

diminishing increment of benefit to be derived from each

crease the value of the maximum lienefit to cost ratio,

addition.'il increment of performance—a tendency to ap-

regardless of the performance level at which the maxi-

projH'li a ]KMnt of dimini.shing returns.

mum ratio would occur. Examiile> of such impn>vement.s

Bcncfit-Cost-Pcrformance Relationship. Figure .i pre-

Percentaee of Maximum Possible Performance Level Percentage of Maximum Possible Performance Level

FIG. 5. Benefit-cost-perfornaance relationship FIG. 6. Cost-performance optimization

202 American Documentation — October 1P67

case the cost of not operating a system is 7iot zero

because the costs to the user of not having a system

would have to be accounted for. The curve in Fig. 3

mif;;ht, in.-itead, lie "U" shaped. Additional mrasurcment

problems include:

1. How do you measure the parameters of perform-

ance, coverage, u,sage, accuracy, speed, and

quahty of products?

2. How are benefits to be detected if they occur

externally to the system?

•i. How are benefits to be measured if they can be

iletected?

Papers on cost/effectiveness are heartily en-conraged.

Convincing management to spend increa.sini^ i^ums of

money for information systems will become increasingly

difficult without means for tangible dollar justification.

FUNCTIONS PERFORMED AVITHIN THK CHANNELS

Percentage of Maximum Possible Petfotmance Level

Within each channel, there is a variety of functions

FIG. 7. Benefit-cost-performance optimization performed to make the channel operative. The com-

parison offered in Table 1 seems to indicate a fairly

are depicted in the figure as increasing the maximum high degree of agreement between Wall {f^\, Simp.-^on

ratio from Point 1 to any of the Points 2, 3, or 4. [7), and Berul [1] in identifying the nature of these

The prime diliiculty with making the above hypotheses functions. A much more generalized expression of func-

a working tool is the elusive nature of the measurability tions was suggested by Ben-Ami Lipetz in a lecture

of the factors invoh'ed. Take, for cxjtmple, the cost before an ADI seminar in Columbus, Ohio, early in

factors. It seems a .straightforward problem to measure 1967. He offered the view that all of these functions

costs of an information system. However, if the concept can he categorized into three general types: (1) Matching

of "system" is extended (as it probably .•should be) to of records, (2) Movement or physical displacement of

include the users and their costs of "doing business,"' the records, (3) Creation of new records l'rom old records.

measurement of costs becomes verv difficuit. In that All the aspects of system functions including those served

TABLE 1. Functions performed witliio information transfer channels;

Wall (6) Simpson (7) Berul (J) Lipetz

Acquisition Acquisition (Origination) Physical comparison of

Acquisition records (matching)

Snrrogation Abstract preparation and Surrogation

dissemination • (Cataloging

• Abstracting

• Indexing

Announcement Accession list preparation Announcement Movement or physical

and dissemination displacement of

Index operation Index preparation and Index operation recortls

dissemination

Document, munageme:nt Storage Document management

Retrieval Retrieval

An.swering teclmical Creation of new records

questions from old records

Analytical studies

\'o(;ibiilary control Reference searching

Referral j^

American Documentation — October 1967 203

TABLE 2. Scientific and technical disciplines involved in information science aii(I tochnolog>'

Disciplines

Type of Endeavor ^ 2

L Theory Development. This field involves efforts toward X X X X X

hiiildini; theory under the wide viiriety of practices that

have empirically d<-veloped as a re.-^ult of the pressing neces-

sity for opei-alinR information systems.

2. Syj'lem Design. Research in thi.'; field would be directed to X X X

makiiifi the design of information sj^stems a systematic

process.

3. Human Rcpiai'ement. The intellectual effort hy humans X X X X X X X

i-ontinue.s to be the major cost factor in information transfer

systems. This field encompasses all of the efforts to develop

automatic techniques to replace human intellectual processes.

4. Language Accommodation. This field covers all sorts of X X X X

technitiues and devices recjuired to accommodate the fact

that langnageH are very inexact-—and to make information

transfer sv'stems work in ypite of that fact.

5. System Operation. Research in this field would encompass X X X

all efforts toward improved efficiency and effectiveness of

the O])eration of information systems.

6. Phildsophiciil Drvi'tojjment. Efforts in this field would be X X X X X X X X X

diri'clrd six'ciliriilly at the frontiers of information scienct—

tlimijiht transmission, profirammed learning, bionic ajiiilica-

tions. For example, an '"informafion transfer philosopher'"

might ask such provocative questions as "Isn't it jiossible

that the teclini(iues of I'eading and writing arc becoming

obsolete as information transfer techniques?'" Literally any

and all disciplines will likely come into play in exploring th<'

philosophical frontiers.

7. Economics. Knipliasis in ihis field would be on (he cost/ X X X X X

benefit aspects of information transfer.

S. Lant^uage Redesign. This field is directed towanl tlie'evolu- X

iion of an exact language to serve at least as the system

language of information transfer systems and, perhaps, for

extended use l)y authors ;)nd in other a.'jpects of scientific

communication.

9. Human Factors. Information transfer systems will remain X X X X

man-machine systems for many years to come despite efforts

in Fiehi (3) above. This field will encompass efforts to im-

]irove llie understanding antl efficiency of the human aspects

of and contributions to information handling.

204 Atnerican Documentation — October 1967

by hardware and software continue to provide im- CURRENT

portajit areas for research and development and thiis,

From many corners are heard coinnients deploring

fruitful topics for discussion within the framework of

the wide gap between research efforts nnd practice in

information transfer for the 1968 ADI Convention.

the field of information science and technology. Man>'

people find it very difficult to foresee how the products

SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL DIBCIPUNKS INVOLVED of current research in the field will find their way into

IN iNFOHM.VriON SriKXCE .-^ND TKrHNOLOdY real-life applications of a practical nature. For such

•people, any efforts to close the breach between researchers

The variety of efforts involveii in research, develop- and practitioners would he welcome contributions. Fig-

ment, technical services, consulting, ami operations con- ure S pre.<ents an example of .such an efi'iirt. It attempts

cerned with information transfer require inputs from a to show how teclun(!ues such as;

number of different scientific diticii)lines. As examples,

Automatic Abstracting

nine areas of consideration serve to iUustrate the diverse Automatic Indexins

disciplinary contributions needed to attack the prob- Character (pattern) recognition

lems. Table 2 presents nine areas of endeavor and their Machine tran^^lation

associatal disciplines. Papers discussing any oj the myriad Autonuilic .'speech analysis

aspects oj the applications oj scientific and technical dis- (presently in various phases of research) may tit inio

ciplines to tiie problems of injormation transfer would the fundanicntjil document handling iunction of proces-

he valuable contribtuions. sing documents to produce indexes. Figure S also in-

INDEXES

HACHINE

PRODUCED.

STORED & SEARCHED

INDEXES

CONVENTIONAL

I

INPUT

EXTRACT

-.

t

I

INFORMATIVE

ABSTRACT

INDICATIVE

MACHINE

BACHINE PROCESSING OF STORED AND

ABSTRACT INTELLECTUALLY PRODUCED SEARCHED

NOTATION OF

INDEX DATA INDEXES

CONTENT

INDEX, SIANUAL PROCESSING •VISUAL-

DATA OF INTELLECTUALLY INDEXES

t PRODUCED INDEX

DATA

FOR "MANUAL"

SEARCHING

CURRENT STATE OF THE ART

NEARING PRACTICAL APPLICATION

"BLUE-SKV RESEARCH

FIG. S. Current research applications

American Documentation — Ocfoher 10fi7 205

dicates tho.se techniques which are now ()]H'r;itiuii;ii. conversion from one natural language to another. How-

those which are nearing practical application, and those ever, even when channel input and output are expressed

which have more or less "bine-sky" status at the present in the same natural language, the correct matching of

time. Not i-overed hy Fip. N are all ol' the various type?: in])nt and output ideas is plagued b>' a number ol'

of research inetliods which will be coiitriiiutory to pro- language problems:

ducing \vorkal)!f tei-hni(]ue^; of thc-^e type:^. For the 1068

ADI Convfiitimi, papers on current research uill be • Semantics—the proi.)lem of word meanings includ-

ing iKith synonyms (groujis of words all having

very much in order especially in two areas: (1) Papers the .-^anie meaning) and homografthri (single wonis

presenting specific current research efforts; (2) Papers each having more than one meaning)

correlating such research efforts with eventual practical • (ienerics—the ])roblem of hierarchical word families

application as exemplified by Fig. S. • Viewpoint—the ])ro!ileni of varying contexts as a

result of varying viewpoints

• Term preconjunetion^exemplified liy the choice be-

VoCABin-AltV CONrilOI./L.^NfiU.ACiE PllOCEaSINti tween the separate terms FLOW and RATE or

All of rlie channels illut^trated in our (general model uf the preconjoined term FLOW RATE as means for

indexing a concept.

information transfer nre troubled with lansuasie dif-

ficulties. The language of the items of int'omiation These language problems, it is claimed, ]troduce ail-

ctit-ering any of the channels is nut hkely to provide a verse effects on the recall/relevance characteristics of

high level of similarity to tho nser's language to which information .systems unless properly controlled. In many

the outi)Ut from the channel mu.-;t attemjit to resjjond. systems, the means of control ha.s lieen the intellectually

Thus, there is u.-;nally a tran.slation ])robk'm between proiluced thesaurus. Rule? for the intellectvial con-

input to and output from any of the channels. struction o!' thesauri have been published by the Engi-

At its wursi. Tlie translation problem will in\()i\'r the neers Joint Council (S). Figure 9 depicts the parallel

(DOCUMENTS)

ACTUAL INDEXING

DOCUMENT (PRODUCES WORK

SHEET)(AUTHOR S

(AUTHOR'S

LANGUAGE AND

LANGUAGE)

INDEXER'S LANGUAGE)

SEARCH

STRATEGY

FORMULATION CONVERSION

STATEMENT OF TO

INFORMATION (ASKER'S SYSTEM

NEEDED LANGUAGE

LANGUAGE

AND SEARCHERS

(ASKERS

LANGUAGE)

LANGUAGE)

Fill. 0. 'riie intei!i(*tioii.-i bcfween vocabulary coiilrol ;ind the ini)ut./outii\it flements of an infornuition storage and retrieval

system.

200 American Documentation — October 1!H.17

nature of the relationships between vocabulary control OPTIM.\L CHAN'KEI, UTU-IZATIOX

function.s and the input and output functions of a typical

information storage and retrieval system. In essence, Figure 1 illustrates well that the user of information

the thesaurus creates a "sy.stem language" which is may have several options available to him when he has

capable of translating or "understanding" both the the need to obtain information. His choice may be

language of the input items an<l the language of the limited by his resotirces or those of his organization.

users which is required for efficient output. Often, however, the options are limited by the lack of

But. is the expensive process of intellectual thesaurus awareness of the individual or his organization of the

construction really necessary for obtaining good system options available. There is also the pos.-'ihility that the

performance? The second phase of the Cranfield Project individnal or his organization desires to improve the

(0) provides some evidence (and it is possible we may availability of information but hesitates to invest the

be ovfT.-^implifying our interpretation of the results) that capital into the deveiopment of this capability because

the .simpler the indexing language, the better the recall/ of uncertainties in the value of the results to l:)e obtained

relevance performance of a system as shown in Fig. 10. or in the choice of what system is best.

If the Cranfield ref^ults may lie extrapolated to apply For example, most organizations when choosing to

generally to all information .systems, the need for elabo- supply their members with assistance often estaltlish

rate thesauri may evaporate. libraries phis several service,= or specialized activities in

addition to the library. Assume that, for dealing with

The tenn "language ]>rocessing" seems to represent a

imblished (or report) literature, an organization decides

much broader sco])e of consideration than the concept of

to provide additional specializefl ser-\-ices to its nienilier.'^.

vocabulary control discussed above. Robert F. Simmons

The library, to meet this requirement, u.^ually will ]>ro-

(10), in tlu^ 1960 Annual Review of Information Science

cure hardware or services to deal with the ])ublished

and Technology, organized his discussion of automated

literature in an overall sense, sueh as classifying journal.-*

language processing as follows:

instead of articles in journals. To i)rovide in-depth in-

• Comjiutntional Linguistics dexing, tho library will likely increase its subscription to

(1) Linguistic Theory commercially available .secondary journals and indexes.

{2} Semantic Theory When a member of the organization de^'elojis a need

(3) Psycholinguistics beyond the commercially available services, then spe-

(4) Automated Syntactic Analysis Systems eialized storage and retrieval mechanisms are procured.

• Ajiplications Studies In many cases, members of special programs and projects

(1) Mechanical Translation with extensive information requirements develop their

(2) Antomated Question Answering

own systems. In other cases, the management of the

(;^| Stylistic ami Content Analysis

organization will authorize the development of large-

We feel that rontributionji in these areas and other scale mechanized information programs using computers,

areas dealing unth language mill provide many oj the microimaging services, or other mechanisms. The mul-

fundamental stepping stones to future improved methods tiple channels that may be used, and the variation of ap-

for expressing ideas and concepts, for converting such proaches within each channel, coupletl with the iiiability

e.rpre.s-sion,'i into storable/manipulable form, and for to show (in (]uantative terms) return on investment,

analyzing, ami correlating elements of information and pose some interesting Cjue.stions on optimizing channel

thus synthesizing them- into new usable intelligence. utilization. The problem of choosing the optimum means

These are ('unctions which ])ro\'ide the underlying frame- within each channel is also a serious systems .«tudy. The

work for improved infonnation transfer. committee encourages the preparation of papers on the

problem of optimal channel selection and the associated

problems of choice irithin cJmnnels.

• Epilu«;ue—^Call for P a p e r s

This paper has set the theme and procedure of the

1908 .VDI Annual Meeting in (.'olumbus, Ohio, October

20-24, !9(iS. Those ]);'r.-'ons who intend to submit papers

should notify David M. Liston, Jr., Battelle Memorial

Institute, 505 King Avenue, Columbus, Ohio 48201 of

their intent hy March 1, ]96S. It would be helpful if

the subject of the intended pajier could be siven at this

Relevance time and if ]iossible the specific area of the general model

Fit;. 10. Recall-re lev ance-performance characteristics of information transfer to wliich it will relate. .\ guide

.American Documentation ^ October I!t'i7 207

for ;nithor.« will lie sent to these pcr^on;^ immediately sented at the Second Coiifcn'ni'p on Electronic In-

upon retieipt of the notification of intent. Minuispripts formation Handling, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1967.

must be rereived by J). M. Liyton by May 1, 1968. 5. MuKDOOK, J. W., and G. S. SIMPSON, JR., S'S and Secrets,

Each person submitting a paper will be notified by July Ameriran Documentation, 18 (No. 2): 110 (1967),

1,196S whether his paper has been accepted. 6. WALL, E., A Rationale for Attacking Information Prob-

lems, American Ddcumentation. 18 ( X o . 2 ) : 97-103

(1967).

7. SIMPSON, G . S., JR., and C. FL.^N.AGAN, Infonnation

Referenres Centers and Services, m C. A. Cuadra. ed.. Annual

Review of Information and Technology, Interscience

1. BKRI'I-, L., Information Storage and Retrieval—A State Publishers. New York. 1966. pp. 305-335.

of the Art Report, Auerbach Corporation, Philadel- 8. SPRIOHT, F . Y., ed.. Guide for Source Indexing and Ab-

phia, Pa., 1964. stracting of the Enginee'iing Literature, Engineers

2. SIMPSON, G. S., JH., Scientific Information Centers in the Joint Council, New York, 1967.

United States, American Documentation, 13 (No. 1): 9. CLEVERDON, C , and M. KEEN, Factors Determining

1962. the Performance of Indexing Systems, Vol. II, ASLIB

3. SHERWIN, C. W., Evaluating and Compressing Scientific Cranfield Research Project, Wharley End, Bedford,

and Technical Information, National Symposium on England, 1966.

I'utliug IrtformnliiiH lietrii'vaJ in Work in the Office 10. SIMMONS, R . F . , Automated Language Processing, in

(1967). C. A. Cuadra, ed.. Annual Revieiv of Information Sci-

4. YoviTS, M. C , and R. L. ERNST, Generalized Informa- ence and Technology, Interscience Publishers, New

tion Systems, The Ohio State University, paper pre- York, 1966, pp. 137-169.

208 American Documentation — October 1967

You might also like

- Packt R Machine Learning Projects 1789807948Document262 pagesPackt R Machine Learning Projects 1789807948telaNo ratings yet

- Humanities Data in RDocument218 pagesHumanities Data in REdwin Wang100% (1)

- BardinDocument25 pagesBardinmarcelhubertNo ratings yet

- ECE 723 - Information Theory and CodingDocument23 pagesECE 723 - Information Theory and CodingHrishikesh VpNo ratings yet

- Communication Nets: Stochastic Message Flow and DelayFrom EverandCommunication Nets: Stochastic Message Flow and DelayRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Information Theory - Spring 2015Document14 pagesInformation Theory - Spring 2015naseebNo ratings yet

- Herner 1984Document7 pagesHerner 1984Edward TaichiNo ratings yet

- Persistent Conversation: A Dialog Between Design and ResearchDocument2 pagesPersistent Conversation: A Dialog Between Design and ResearchdasdsasadNo ratings yet

- Mapping Conversations About New MediaDocument30 pagesMapping Conversations About New MediaTerim ErdemlierNo ratings yet

- Alis 67 (3) 164-172Document9 pagesAlis 67 (3) 164-172Sougata ChattopadhyayNo ratings yet

- Brief History of Information Science HERNER, 1984.Document12 pagesBrief History of Information Science HERNER, 1984.Márcio FinamorNo ratings yet

- Digital Libraries: A Conceptual Framework: I R D BDocument11 pagesDigital Libraries: A Conceptual Framework: I R D BPeter SevillaNo ratings yet

- La Conservation A Long Terme Des DocumenDocument14 pagesLa Conservation A Long Terme Des DocumenAdrian PelivanNo ratings yet

- Mayr2016 Article RecentApplicationsOfKnowledgeODocument4 pagesMayr2016 Article RecentApplicationsOfKnowledgeOEmailNo ratings yet

- 25 Centuries of MathDocument10 pages25 Centuries of MathNandang Arif SaefulohNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Discovery in Digital Libraries of Electronic Theses and Dissertations: An NDLTD Case StudyDocument9 pagesKnowledge Discovery in Digital Libraries of Electronic Theses and Dissertations: An NDLTD Case StudyMihaela BarbulescuNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Discovery in Digital Libraries of Electronic Theses and Dissertations: An NDLTD Case StudyDocument10 pagesKnowledge Discovery in Digital Libraries of Electronic Theses and Dissertations: An NDLTD Case StudyVikanhnguyenNo ratings yet

- The Owl and The Electric Encyclopedia : Brian Cantwell SmithDocument38 pagesThe Owl and The Electric Encyclopedia : Brian Cantwell Smithjorthwein1No ratings yet

- Lecture Notes in Computer Science 3360: Editorial BoardDocument232 pagesLecture Notes in Computer Science 3360: Editorial BoardLeandro CamargoNo ratings yet

- Bilingual Subject-Based Information Retrieval in NECLIB2 Digital LibraryDocument5 pagesBilingual Subject-Based Information Retrieval in NECLIB2 Digital Librarysurendiran123No ratings yet

- Theoretical Field of Digital CommDocument23 pagesTheoretical Field of Digital CommAndromeda MartinezNo ratings yet

- Michael S. MahoneyDocument13 pagesMichael S. MahoneyakyNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Research ADocument11 pagesInterdisciplinary Research AGrațiela GraceNo ratings yet

- NT&T WPS 5 LamsDocument20 pagesNT&T WPS 5 LamsTom Van HoutNo ratings yet

- Project On ICTDocument59 pagesProject On ICTVinayPawarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document6 pagesChapter 3Temam MohammedNo ratings yet

- 38 JensenDocument20 pages38 JensenJoanna CaysNo ratings yet

- Media Convergence Holliman 2010Document12 pagesMedia Convergence Holliman 2010Narejo KashifNo ratings yet

- The Bibliographic Chain Model, Doyle and GrimesDocument9 pagesThe Bibliographic Chain Model, Doyle and GrimesMichelle RadebeNo ratings yet

- 1st Week Technical Communication OverviewDocument42 pages1st Week Technical Communication OverviewBishnu Tcit Kathmandu AmericaNo ratings yet

- Processing of Visible Language PDFDocument530 pagesProcessing of Visible Language PDFlazut273No ratings yet

- GESIS - Leibniz Institute For The Social Sciences Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung. SupplementDocument14 pagesGESIS - Leibniz Institute For The Social Sciences Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung. Supplementsamon sumulongNo ratings yet

- Archival Principles Respect Des Fonds and Principe de ProvenanceDocument2 pagesArchival Principles Respect Des Fonds and Principe de ProvenanceṦAi Dį100% (1)

- Davis Foulger-Communication ProcessDocument13 pagesDavis Foulger-Communication ProcessArum Sari50% (2)

- Research Project: A Taxonomy of "Interactive Art"Document17 pagesResearch Project: A Taxonomy of "Interactive Art"fedoerigoNo ratings yet

- MIL MODULE Week 6Document9 pagesMIL MODULE Week 6Ginalyn QuimsonNo ratings yet

- 1st Week Technical Communication OverviewDocument44 pages1st Week Technical Communication OverviewBishnu Tcit Kathmandu AmericaNo ratings yet

- ContentServer PDFDocument15 pagesContentServer PDFlaureanofgNo ratings yet

- Mku ThesisDocument7 pagesMku Thesisjessicahillnewyork100% (1)

- 1 s2.0 S221169582300048X MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S221169582300048X MainPaula LiendoNo ratings yet

- Portals, Blogs and Co.: The Role of The Internet As A Medium of Science CommunicationDocument12 pagesPortals, Blogs and Co.: The Role of The Internet As A Medium of Science CommunicationNatália FloresNo ratings yet

- Digital Scholarly EditingDocument21 pagesDigital Scholarly EditingNatalie Kiely100% (1)

- Historical Reflections: Five Lessons From Really Good HistoryDocument4 pagesHistorical Reflections: Five Lessons From Really Good HistoryMarios NtoulasNo ratings yet

- Informationa RetrivalDocument22 pagesInformationa RetrivalOrnellas JotamoNo ratings yet

- NSF 2005 CI in The HumanitiesDocument24 pagesNSF 2005 CI in The HumanitiesRohnWoodNo ratings yet

- Center For The Study of Digital LibrariesDocument12 pagesCenter For The Study of Digital LibrariesIrene Garcia BlancoNo ratings yet

- A New Direction For Bibliographic Records? The Development of Functional Requirements For Bibliographic RecordsDocument5 pagesA New Direction For Bibliographic Records? The Development of Functional Requirements For Bibliographic RecordstudorbiliboiNo ratings yet

- Portable Documents: Problems and (Partial) Solutions: ELECTRONIC PUBLISHING, VOL. 8 (4), 343-367 (MARCH 1996)Document25 pagesPortable Documents: Problems and (Partial) Solutions: ELECTRONIC PUBLISHING, VOL. 8 (4), 343-367 (MARCH 1996)Sumit DattanNo ratings yet

- Glosario TICS 17-18Document13 pagesGlosario TICS 17-18Seabiscuit NygmaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Online Journalism: Nashariya BamcDocument21 pagesIntroduction To Online Journalism: Nashariya BamcBiji ThottungalNo ratings yet

- @XXX - Lanl.gov: First Steps Toward Electronic Research CommunicationDocument10 pages@XXX - Lanl.gov: First Steps Toward Electronic Research CommunicationMitser VegasNo ratings yet

- MediaSync: Handbook on Multimedia SynchronizationFrom EverandMediaSync: Handbook on Multimedia SynchronizationMario MontagudNo ratings yet

- Interactive MultimediaDocument19 pagesInteractive Multimedias160818035No ratings yet

- Harvesting Wiki Consensus - Using Wikipedia Entries As Ontology ElementsDocument15 pagesHarvesting Wiki Consensus - Using Wikipedia Entries As Ontology ElementsUberalchemyNo ratings yet

- Impact of Information & Communication Technology On Library & Information CentresDocument40 pagesImpact of Information & Communication Technology On Library & Information CentresBhavyata MalikNo ratings yet

- Henning 2008Document2 pagesHenning 2008Daniel VegaNo ratings yet

- s13688-023-00418-1Document16 pagess13688-023-00418-1margottincyNo ratings yet

- Heim y Tymowski - 2006 - Guidelines For The Translation of Social Science Texts PDFDocument30 pagesHeim y Tymowski - 2006 - Guidelines For The Translation of Social Science Texts PDFJosé SilvaNo ratings yet

- Master Thesis VPNDocument8 pagesMaster Thesis VPNppxohvhkd100% (2)

- Archives, Access and Artificial Intelligence: Working with Born-Digital and Digitized Archival CollectionsFrom EverandArchives, Access and Artificial Intelligence: Working with Born-Digital and Digitized Archival CollectionsLise JaillantNo ratings yet

- Applications of Digital Image Processing in Real Time WorldDocument4 pagesApplications of Digital Image Processing in Real Time Worldmaneesh sNo ratings yet

- Ics 2210, Bit 2112 Kisii Olive 2Document2 pagesIcs 2210, Bit 2112 Kisii Olive 2123 321No ratings yet

- Tao2018 - Digital Twin in Industry SoADocument11 pagesTao2018 - Digital Twin in Industry SoAbmdeonNo ratings yet

- C# DocsDocument2,288 pagesC# DocsKomal GawaiNo ratings yet

- Évaluation Certificative - CESS - 2014 - Histoire - Dossier de L'enseignant Et Guide de Correctio (Ressource 10701)Document16 pagesÉvaluation Certificative - CESS - 2014 - Histoire - Dossier de L'enseignant Et Guide de Correctio (Ressource 10701)KamizuNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence Applications For Improved Software Engineering Development by Farid Meziane & Sunil VaderaDocument371 pagesArtificial Intelligence Applications For Improved Software Engineering Development by Farid Meziane & Sunil Vaderasathi007No ratings yet

- Microsoft Research's RF Program 2023 - Candidate Interest FormDocument11 pagesMicrosoft Research's RF Program 2023 - Candidate Interest FormAravind PalanivelNo ratings yet

- Pds Question BankDocument5 pagesPds Question Bankpatelom1320No ratings yet

- Assignment 2 EmergingDocument3 pagesAssignment 2 Emergingaldrichgonzales512No ratings yet

- Unit 3 - Telehealth Technology Anna UniversityDocument36 pagesUnit 3 - Telehealth Technology Anna UniversitySuraj PradeepkumarNo ratings yet

- DBMS Bal Krishna Nyaupane PDFDocument166 pagesDBMS Bal Krishna Nyaupane PDFPrabin123No ratings yet

- BSC Iiyr IV Sem Dbms Total NotesDocument110 pagesBSC Iiyr IV Sem Dbms Total NotesVistasNo ratings yet

- Bekele WorkuDocument101 pagesBekele Workuengidaw awokeNo ratings yet

- Computer Science ProjectDocument37 pagesComputer Science Projectpradeeshsivakumar2006No ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document6 pagesAssignment 2Abdul Ahad SaeedNo ratings yet

- Computer Science Option A DatabaseDocument9 pagesComputer Science Option A DatabaseKrish Madhav ShethNo ratings yet

- 2 - Data Science ToolsDocument21 pages2 - Data Science ToolsDaniel VasconcellosNo ratings yet

- Application Permutation in CryptographyDocument3 pagesApplication Permutation in CryptographyBasyirah Mohd ZawawiNo ratings yet

- DBMS Assignment Supriya SinghDocument6 pagesDBMS Assignment Supriya SinghSupriya SinghNo ratings yet

- 14th ICCCNT 2023 Paper 988Document6 pages14th ICCCNT 2023 Paper 988miniature testNo ratings yet

- Earthquake Rubric SDocument5 pagesEarthquake Rubric SEchavez Mark AnthonyNo ratings yet

- File Handling IntroductionDocument2 pagesFile Handling Introductionsamrudhi50% (4)

- A.8.1.2 Ownership of Assets A.8.1.3 Acceptable Use of AssetsDocument2 pagesA.8.1.2 Ownership of Assets A.8.1.3 Acceptable Use of AssetsSara CruzNo ratings yet

- Semantc Web and Social NetworksDocument63 pagesSemantc Web and Social NetworksANCY THOMASNo ratings yet

- Solidity CheatSheetDocument35 pagesSolidity CheatSheetKillian DroumartNo ratings yet

- 3 Hours / 70 Marks: Seat NoDocument2 pages3 Hours / 70 Marks: Seat NoasddfNo ratings yet

- Online SourcesDocument7 pagesOnline SourcesTeo PhiriNo ratings yet

- Resume 1Document1 pageResume 1saur1No ratings yet

- Sec Attacks in CCDocument575 pagesSec Attacks in CCsimranNo ratings yet