Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Uclg-gold-Vi en Libro Print

Uclg-gold-Vi en Libro Print

Uploaded by

Edgardo BilskyCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- ALLEN - Sustainable Engineering Concepts, Design, and Case StudiesDocument228 pagesALLEN - Sustainable Engineering Concepts, Design, and Case Studiesadam100% (1)

- Investing in Early Childhood Development: Review of the World Bank's Recent ExperienceFrom EverandInvesting in Early Childhood Development: Review of the World Bank's Recent ExperienceNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Human Settlements within the Global Urban Agenda: Formulating and Implementing SDG 11From EverandSustainable Human Settlements within the Global Urban Agenda: Formulating and Implementing SDG 11No ratings yet

- Integrating Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Management: A Practitioner's GuideFrom EverandIntegrating Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Management: A Practitioner's GuideNo ratings yet

- Crowdsourced Geographic Information Use in GovernmentFrom EverandCrowdsourced Geographic Information Use in GovernmentNo ratings yet

- Highlights of ADB’s Cooperation with Civil Society Organizations 2020From EverandHighlights of ADB’s Cooperation with Civil Society Organizations 2020No ratings yet

- COVID-19 and Livable Cities in Asia and the Pacific: Guidance NoteFrom EverandCOVID-19 and Livable Cities in Asia and the Pacific: Guidance NoteNo ratings yet

- Uniquely Urban: Case Studies in Innovative Urban DevelopmentFrom EverandUniquely Urban: Case Studies in Innovative Urban DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- World Public Sector Report 2021: National Institutional Arrangements for Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals – A Five-year StocktakingFrom EverandWorld Public Sector Report 2021: National Institutional Arrangements for Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals – A Five-year StocktakingNo ratings yet

- Enabling Inclusive Cities: Tool Kit for Inclusive Urban DevelopmentFrom EverandEnabling Inclusive Cities: Tool Kit for Inclusive Urban DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Fair Shared City: Guidelines for Socially Inclusive and Gender-Responsive Residential DevelopmentFrom EverandFair Shared City: Guidelines for Socially Inclusive and Gender-Responsive Residential DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- The Integrated Disaster Risk Management Fund: Sharing Lessons and AchievementsFrom EverandThe Integrated Disaster Risk Management Fund: Sharing Lessons and AchievementsNo ratings yet

- GTF 6th Report To The HLPF FinalDocument179 pagesGTF 6th Report To The HLPF FinalEdgardo BilskyNo ratings yet

- Gold Vi ReportDocument47 pagesGold Vi ReportEdgardo BilskyNo ratings yet

- Democratizing: Gold Vi ReportDocument68 pagesDemocratizing: Gold Vi ReportEdgardo BilskyNo ratings yet

- Gold Vi ReportDocument54 pagesGold Vi ReportEdgardo BilskyNo ratings yet

- Gold Vi ReportDocument47 pagesGold Vi ReportEdgardo BilskyNo ratings yet

- Design and Construction of A Low Cost Plastic Shredding MachineDocument13 pagesDesign and Construction of A Low Cost Plastic Shredding MachineBINIYAM ALAMREWNo ratings yet

- Proclaiming Value Via Sustainable Pricing StrategiesDocument2 pagesProclaiming Value Via Sustainable Pricing StrategieskimberlyocampojmaNo ratings yet

- Relaciones Tamaño-DensidadDocument32 pagesRelaciones Tamaño-DensidadjvenegasNo ratings yet

- SUSTAINABLE TOURISM PrefinalsDocument4 pagesSUSTAINABLE TOURISM PrefinalsNicole SarmientoNo ratings yet

- Uso Del Modelo Random Forest Cuenca SibinacochaDocument147 pagesUso Del Modelo Random Forest Cuenca SibinacochaMarcelo CarreñoNo ratings yet

- La Teoría Del Desarrollo Organizacional ExposicionDocument4 pagesLa Teoría Del Desarrollo Organizacional Exposicionjavierki isturizNo ratings yet

- Observa El Entorno Donde Vives y Describe en Tu Cuaderno Que Elementos Naturales Se Encuentran PresentesDocument4 pagesObserva El Entorno Donde Vives y Describe en Tu Cuaderno Que Elementos Naturales Se Encuentran Presentesluis100% (1)

- Cycle SédimentaireDocument24 pagesCycle SédimentaireFatima MEHDIOUINo ratings yet

- Chapter - 3 Drainage SystemDocument5 pagesChapter - 3 Drainage SystemAjay JangraNo ratings yet

- Nature PowerPoint Backgrounds-PlayfulDocument14 pagesNature PowerPoint Backgrounds-Playfuljeanette caagoyNo ratings yet

- Fase 1 Manejo de Sustancias PeligrosasDocument9 pagesFase 1 Manejo de Sustancias PeligrosasSistema De Gestion TRANSCONT SASNo ratings yet

- Ordenanzas 1997-2018Document268 pagesOrdenanzas 1997-2018Lucia NarvaezNo ratings yet

- Oraciones IncompletasDocument1 pageOraciones IncompletasAlan Yataco TasaycoNo ratings yet

- DESMALEZARDocument6 pagesDESMALEZARGaston GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Triptico Tema 3.3.1Document2 pagesTriptico Tema 3.3.1MARIA DANIELA MAYORGA GARCIANo ratings yet

- Reflexiones, Oracion y Desfile Izada 2Document4 pagesReflexiones, Oracion y Desfile Izada 2Miguel SanchezNo ratings yet

- Anexo 1 - Ficha de Lectura para El Desarrollo de La Fase 2Document5 pagesAnexo 1 - Ficha de Lectura para El Desarrollo de La Fase 2luis15No ratings yet

- PDF Guia Atropellamiento de Fauna Itm Version Final 21042021 - CompressDocument99 pagesPDF Guia Atropellamiento de Fauna Itm Version Final 21042021 - Compresszaritffe florez100% (1)

- PMPT-018-Plan de Gestión de Riesgos MalecónDocument44 pagesPMPT-018-Plan de Gestión de Riesgos MalecónCARLOS RAMIREZNo ratings yet

- Cape Chemistry Module 3Document7 pagesCape Chemistry Module 3Giselle Williams-VachéNo ratings yet

- Planos de Ação - 3 ETAPAS - Teorias Neoclássica, Estruturalista e Hawthorne.Document4 pagesPlanos de Ação - 3 ETAPAS - Teorias Neoclássica, Estruturalista e Hawthorne.Nathália DiasNo ratings yet

- Una Carta Abierta A Los Niños Del MundoDocument3 pagesUna Carta Abierta A Los Niños Del Mundomartha_valencia_6No ratings yet

- "THEORISTS and Its Metaparadigm": Person HealthDocument4 pages"THEORISTS and Its Metaparadigm": Person HealthJyrhene Crizzma ZepedaNo ratings yet

- Plantilla 3.3 ApropiaciónDocument16 pagesPlantilla 3.3 ApropiaciónEsteban Zapata CaroNo ratings yet

- Informe Trasferencia de OxigenoDocument10 pagesInforme Trasferencia de OxigenoAleja OlivaresNo ratings yet

- Building Construction ItemsDocument39 pagesBuilding Construction ItemsMetre SNo ratings yet

- President Yoweri .K.museveni Opens The 6 TH Oil and Gas ConventionDocument8 pagesPresident Yoweri .K.museveni Opens The 6 TH Oil and Gas ConventionGCICNo ratings yet

- Especificaciones Tecn. Linea de Impulsion 1Document91 pagesEspecificaciones Tecn. Linea de Impulsion 1Joel Villarreal ChinchayNo ratings yet

- Higiene y Seguridad Unefa 1-2018Document55 pagesHigiene y Seguridad Unefa 1-2018lilibeth Suarez reyes100% (1)

Uclg-gold-Vi en Libro Print

Uclg-gold-Vi en Libro Print

Uploaded by

Edgardo BilskyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Uclg-gold-Vi en Libro Print

Uclg-gold-Vi en Libro Print

Uploaded by

Edgardo BilskyCopyright:

Available Formats

Addressing inequalities through

local transformation strategies 2022

In partnership with:

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 1 20-09-22 17:43

© 2022 UCLG Co-funded by:

Published in October 2022 by United Cities and

Local Governments. This work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO

This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its

License unless otherwise stated.

contents are the sole responsibility of UCLG and UCL and do not necessarily reflect the

views of the European Union.

United Cities and Local Governments

Cités et Gouvernements Locaux Unis

Ciudades y Gobiernos Locales Unidos

This document has been financed by the Swedish International Development Cooperation

Avinyó, 15

Agency, Sida. Sida does not necessarily share the views expressed in this material.

08002 Barcelona

Responsibility for its content rests entirely with the authors.

www.uclg.org

DISCLAIMERS

The terms used concerning the legal status of any

country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, This document was produced with the financial support of the Barcelona Provincial

or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or Council. Its contents are the sole responsibility of UCLG and UCL and do not necessarily

boundaries, or regarding its economic system or reflect the views of the Barcelona Provincial Council.

degree of development do not necessarily reflect

the opinion of United Cities and Local Governments.

The analysis, conclusions and recommendations

of this report do not necessarily reflect the views

of all the members of United Cities and Local

Governments. This document was produced with the financial support of the Conseil départemental des

Yvelines. Its contents are the sole responsibility of UCLG and UCL and do not necessarily

reflect the views of the Conseil départemental des Yvelines.

This document was produced by UCLG and the ‘‘Knowledge in Action for Urban Equality”

(KNOW) programme. KNOW is led by the Bartlett Development Planning Unit, UCL, and

funded by UKRI through the Global Challenges Research Fund GROW Call. Grant Ref:

ES/P011225/1

Supported by:

This document was produced by UCLG and the

Knowledge in Action for Urban Equality (KNOW)

programme, with the support of the Bartlett

Development Planning Unit, University College

London (DPU-UCL), and the International Institute

for Environment and Development (IIED).

Graphic design and layout:

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 2 20-09-22 17:43

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 3 20-09-22 17:43

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 4 20-09-22 17:43

Addressinginequalities through

localt ransformation strategies 2022

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 5 20-09-22 17:43

Contents

Editorial board

page 07

Foreword

page 08

Acronyms

page 10

Chapter 01 Chapter 06

Introduction Connecting

page 14 page 208

Chapter 02 Chapter 07

State of inequalities Renaturing

page 32 page 264

Chapter 03 Chapter 08

Governance and Prospering

pathways to urban

page 312

and territorial Chapter 09

equality Democratizing

page 92 page 370

Chapter 04 Chapter 10

Commoning Conclusions

and final

page 120

Chapter 05 recommendations

Caring

page 432

page 164

Bibliography

page 132

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 6 20-09-22 17:43

Editorial board

Editorial board

We extend a special acknowledgement

Editorial team to all members of academia, civil society

organizations, international networks, UCLG

GOLD VI Steering Committee committees and working groups, and local

and regional governments that participated

Edgardo Bilsky

in the production of this Report. Individual

Coordinator of Research, United Cities and Local Governments. GOLD VI UCLG lead

contributors are specifically acknowledged

Caren Levy in the chapter(s) they supported. Particular

Professor of Transformative Urban Planning, The Bartlett Development Planning Unit, acknowledgement is due to Susan Parnell

University College London. GOLD VI KNOW lead (Global Challenges Research Professor in the

School of Geography at the University of Bristol

Anna Calvete Moreno and Emeritus Professor at the African Centre

Research Officer, United Cities and Local Governments for Cities at the University of Cape Town) and

Camila Cociña Aromar Revi (Director of the Indian Institute for

Research Fellow, The Bartlett Development Planning Unit, University College London Human Settlements) for their contribution about

Transforming Change at Scale.

Ainara Fernández Tortosa

Research Officer, United Cities and Local Governments

We would also like to extend a special

Amanda Fléty acknowledgement to David Satterthwaite

Coordinator of the Committee on Social Inclusion, Participatory Democracy and Human (Senior Associate at the IIED and Visiting

Rights, United Cities and Local Governments Professor at the Bartlett Development Planning

Alexandre Apsan Frediani Unit, UCL) for his participation in the production

Principal Researcher, Human Settlements Group, International Institute for Environment of several GOLD Reports, including GOLD

and Development VI. GOLD has benefitted from his invaluable

contributions to the urban field and his tireless

Cécile Roth work to give community knowledge and action

Research Officer, United Cities and Local Governments a public platform. This inspiring work has

deepened understandings of urban poverty

and inequality, and the collective responses to

Support address it.

Camille Tallon

Research Intern, United Cities and Local Governments

Nicola Sorsby

Coordinator, Human Settlements Group, International Institute for Environment and

Development

Jaume Puigpinós

Former Officer of the Committee on Social Inclusion, Participatory Democracy and Human

Rights, United Cities and Local Governments

Policy advisory

Emilia Saiz

Secretary General, United Cities and Local Governments

UCLG Policy Councils 2019-2022

UCLG World Secretariat

Serge Allou, José Álvarez, Saul Baldeh, Pere Ballester, Federico Batista Poitier, Jean-

Baptiste Buffet, Xavier Castellanos, Benedetta Cosco, Edoardo De Santis, Adrià Duarte,

Glòria Escoruela, Pablo Mariani, Pablo Fernández Marmissolle, Fátima Fernández, Claudia

García, Sara Hoeflich, Paloma Labbé, Albert Lladó, Marta Llobet, Mireia Lozano, Prachi

Metawala, Carole Morillon, Julia Munroe, Carolina Osorio, Jordi Pascual, Massimo Perrino,

Samuel Rabaté, Claudia Ribosa, María Alejandra Rico, Agnès Ruiz, Alessandra Rutigliano,

Antònia Sabartés, Fátima Santiago, Fernando Santomauro, Elisabeth Silva, Juan Carlos

Uribe, Sarah Vieux, Rosa Vroom

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 7 20-09-22 17:43

Foreword

Foreword

For decades, many public policies around the world have aimed at reducing

inequalities and guaranteeing inclusion. In spite of this, great gaps still persist

and can even been described as systemic. Addressing them will be critical not

only to handle the many overlapping crises facing our world today, but also to

define a sustainable and more equal path forward.

As we approach the mid-term review of 2030 Agenda implementation and follow-up,

we will need to be more ambitious in bridging these systemic gaps by reforming

our governance systems and our production and consumption models, not only to

satisfy the current needs of our communities but also to safeguard the aspirations

of generations to come. Inequalities are embedded in the places where people live

and which are governed by local and regional governments. Inequalities manifest

themselves in the urban and territorial fabric: growing between neighbourhoods, urban

systems and territories – between globalized metropolises and regions, intermediary

cities and marginalized rural regions and towns.

The international municipal movement led by United Cities and Local Governments is

convinced that the provision of strong local public services, accessible to all, in cities

that facilitate social inclusion, proximity and the ecological transition, are critical

to generate caring societies that have equality and justice at their core. A local,

feminist way of governing, leading through empathy, which addresses the needs of

populations that have been historically marginalized; an ecological transformation

that makes our relationship with nature sustainable; and a renewed governance

culture and fiscal architecture are the pillars of the sustainable future we imagine

being built from the bottom up.

This sixth GOLD Report builds on these premises, as well as on the grounded

experiences of UCLG’s membership around the world and the transformative vision

that drives their actions. Building on localization efforts to achieve the universal

development agendas and considering them as a framework, the Report has been

coproduced through broad multistakeholder dialogue involving civil society coalitions,

academia, UCLG committees and partners, as well as local and regional governments.

Aware of the complex nature of the responses needed, the Report innovates by

introducing the notion of “pathways to urban and territorial equality”, which can

be understood as trajectories of change, capable of supporting decision-making

processes, policies, actions and planning systems that actively seek to improve

urban and territorial equality. The Report proposes six such pathways that local

and regional governments, in addition to all other stakeholders, need to advance

to achieve equality: Commoning, Caring, Connecting, Renaturing, Prospering and

Democratizing. Combined, they form the vision that the Report is advancing: a radical

revision of urban and territorial development strategies and policies to safeguard

the future of people and the planet through better governance.

8 GOLD VI REPORT

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 8 20-09-22 17:43

Foreword

Acknowledging that no single level of government nor any single actor can tackle

these challenges alone, the Report calls for adopting a rights-based approach,

effective subnational governance and a reviewed financial architecture. It also

encourages alternative ways of conceiving and managing space and time in cities and

territories to support incremental practices for localizing sustainable development

and addressing inequalities. This calls for enhancing local and regional governments’

capacities to lead and support transformative initiatives that stem from alliances at

the local level. By going beyond their usual powers and responsibilities, they ensure

a new governance that is multilevel and collaborative, promoting ecosystems and

partnerships for mutual support in ways that boost cocreation with our communities.

Most importantly, shaping a more equal, just and sustainable future requires

transformative action from local and regional governments. The pathways described

above and the content of this Report are essential contributions to UCLG policy

initiatives and to its Pact for the Future, which will be presented during UCLG’s

7th World Congress in Daejeon in October 2022. Built in accordance with its three

pillars – people, planet and government – GOLD VI identifies equality as an essential

building block of a transformed relationship between people and nature, which

requires responsive and accountable governments.

As we head towards the Summit of the Future, it is our hope that our work will be a

source of inspiration to our membership around the world. We hope that it will foster

renewed leadership practices and governance systems that will continue to shape

partnerships and trigger actions contributing to sustainable peace and developing

a universal shared agenda for years to come.

Emilia Saiz Carrancedo

UCLG Secretary General

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 9 20-09-22 17:43

Acronyms

Acronyms

ACHR Asian Coalition for Housing Rights

BRICS Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa

BRT Bus rapid transit

CAAP Community Action Area Planning

CASE-LSE London School of Economics – Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion Research

CBC Case-based contribution

CCTV Closed-circuit television

CITU Concrete Industry Trade Union (Hong Kong)

CLH Community-led housing

CLT Community land trust

COP Conference of the Parties

COVID-19 Coronavirus disease, originated by SARS-CoV-2 virus

CSO Civil society organization

e.g. Exempli gratia

etc. Et cetera

EU European Union

EUR Euro

FEDURP Federation of the Rural and Urban Poor of Sierra Leone

GBP British pound sterling

GDP Gross domestic product

GHG Greenhouse gas

GIS Geographic information system

GOLD VI 6th report of the Global Observatory on Local Democracy and Decentralization

GNI Gross national income

GPR2C Global Platform for the Right to the City

HDI Human Development Index

HIC Habitat International Coalition

10 GOLD VI REPORT

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 10 20-09-22 17:43

Acronyms

HIV/AIDS Human Immunodeficiency Virus / Acquired immunodeficiency Syndrome

HKD Hong Kong dollar

HLPF High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development

HRC Human Rights City

IBC Issue-based contribution

ICLEI International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives

ICT Information and communication technologies

i.e. Id est

IGP The University College London’s Institute of Global Prosperity

ILO International Labour Organization

IMF International Monetary Fund

IOM International Organization for Migration

IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

IT Information technologies

ITU International Telecommunication Union

KNOW Knowledge in Action for Urban Equality

KRW South Korean won

LGA Local and regional government association

LED Local economic development

LEDA Local economic development agency

LGBTQIA+ Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual+

LIS Luxembourg Income Study Database

LRG Local and regional government

LSE London School of Economics

MDG Millennium Development Goal

MENA Middle East and North Africa

MIF Multidimensional Inequality Framework

MPI Multidimensional Poverty Index

MPPN Multidimensional Poverty Peer Network

MRTC Mass Transit Railway Corporation (Hong Kong)

NGO Non-governmental organization

NHAG Namibia Housing Action Group

11

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 11 20-09-22 17:43

Acronyms

NIP Neighbourhood improvement programme

NUA New Urban Agenda

NUP National urban policy

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

PB Participatory budgeting

PM10, PM2.5 Particulate matter with a diameter smaller than respectively 10 and 2.5 µm

PPP Purchasing power parity

PWD Person with disabilities

SDFN Shack Dwellers Federation of Namibia

SDG Sustainable Development Goal

SDI Shack/Slum Dwellers International

SLURC Sierra Leone Urban Research Centre

SME Small and medium-sized enterprise

SNG Subnational government

SNG-WOFI World Observatory on Subnational Government Finance and Spending

SSA Sub-Saharan Africa

SSE Social and solidarity economy

SSEOE Social and solidarity economy organization and enterprise

THN Thailand Homeless Network

TOD Transit-oriented development

UCLG United Cities and Local Governments

UK United Kingdom

UN United Nations

UNDESA UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

UNICEF United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund

USA United States of America

USD United States dollar

V-dem Varieties of Democracy Institute

VLR Voluntary Local Review

12 GOLD VI REPORT

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 12 20-09-22 17:43

Acronyms

VSR Voluntary Subnational Review

WHO World Health Organization

WID World Inequality Database

WIEGO Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing

WIID World Income Inequality Database

WRI World Resources Institute

ZAR South African rand

Symbols

m (unpreceded by space) Million

bn Billion

m (preceded by space) Metre

km Kilometre

m² Square metre

m-3 Cubic metre

μg Microgram

kWh Kilowatt-hour

CO2 Carbon dioxide

NO2 Nitrogen dioxide

°C Celsius degree

% Percent

+ Over

13

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 13 20-09-22 17:43

01

Introduction

Pathways to urban and territorial

equality: Addressing inequalities through

local transformation strategies

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 14 20-09-22 17:43

Source: Bryan Martinez.

“A world of peace”. Quito, Ecuador. From the intiative “Metropolis through Children’s Eyes” by Metropolis. See more: https://imaginemetropolis.org

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 15 20-09-22 17:43

Abstract

Abstract

For UCLG, as an equality-driven movement, addressing

inequalities is a key priority for promoting the central

role of local and regional governments (LRGs): leaving

no one and no place behind. This chapter introduces

the aims, objectives, scope and structure of the GOLD

VI Report, which focuses on pathways to urban and

territorial equality and examines different ways in which

LRGs can address inequalities through local transfor-

mation strategies. This introductory chapter presents

the approach adopted by GOLD VI to combat urban and

territorial equality. It is organized in a series of sections.

Section 1 introduces the central focus on equality, as

well as the important role that local action and LRGs

have to play in this challenge. It also presents the

strategic objectives of the Report. Section 2 provides

a definition of urban and territorial equality and reflects

on the multidimensional nature of inequalities and the

intertwined relationship between inequality and other

challenges to development and crises: equal distribution,

reciprocal recognition, parity political participation, and

solidarity and mutual care. It then introduces the notion

of pathways as a framework in which to discuss LRG

responses to inequalities within the Report. Section 3

briefly explains the process behind the coproduction

of GOLD VI, which assumes that a transformative

agenda for equality needs to be shaped by a collective

process that relies on the experiences and knowledges

of multiple actors. Section 4 describes the structure

and elements of the Report. It explains how to read it,

provides a review of the different sections, and offers a

brief introduction to the six pathways that structure the

Report and to the principles derived from the exploration

of these pathways and the resulting recommendations.

16 GOLD VI REPORT

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 16 20-09-22 17:43

1 Urban and territorial inequalities

1 Urban and territorial

inequalities: An

urgent challenge

for humanity and

the critical role of

local and regional

governments

The last three years have been a challenging time for that this had occurred since the concept was developed

cities and territories across the globe. While local and in 1990.1 According to projections by the International

regional governments (LRGs), national governments, Labour Organization (ILO), the total number of global

organized civil society and international agencies have hours worked in 2021 was 4.3% below pre-pandemic

mobilized their capacities to the limit to respond to the levels; this was equivalent to 125 million full-time jobs

unprecedented demands of the COVID-19 crisis, old and and there was a disproportionate impact on self-em-

new territorial challenges have become more acute and ployed and informal workers.2 The World Bank estimates

have continued to undermine the human rights of large

parts of the population. The United Nations Develop-

ment Programme (UNDP) estimates that global human 1 UNDP, “Coronavirus vs. Inequality,” 2020, https://bit.ly/3qahXP8.

development declined in 2020; that was the first time 2 ILO, “ILO Monitor: COVID-19 and the World of Work. Eighth Edition.”

(Geneva, 2021), https://bit.ly/364fYFp.

01 INTRODUCTION 17

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 17 20-09-22 17:43

1 Urban and territorial inequalities

that COVID-19 could have subjected as many as 150 in protecting people from exacerbated vulnerability

million people to extreme poverty in 2021.3 We know that and eviction.5 These local actions have been combined

the impact of this global historical juncture has been with efforts to coordinate common global agendas and

unevenly distributed and that it has been experienced international solidarity, understanding the importance of

differently across populations, regions and cities. It coordinated action to respond to structural constraints.

has, in turn, exacerbated the plight of those who were It is through these efforts that GOLD VI seeks to add a

already suffering from multiple, intersectional social collective “urban and territorial equality” perspective.

disadvantages. At the centre of this lies an undeniable It acknowledges that, to achieve the 2030 Agenda

challenge: inequalities. Three-quarters of cities were for Sustainable Development objective of “leaving

more unequal in 2016 than in 1996.4 Inequalities are no-one and no place behind”, it is crucial to promote

perpetuated by structures inherited from longstanding equality when localizing the Sustainable Development

trajectories of injustice, but also exacerbated by other Goals (SDGs).6

adverse phenomena such as wars, the climate emer-

gency, forced migration, and – of course – COVID-19.

This Report is a collective effort to put inequalities GOLD VI has three

strategic objectives:

at the centre of urban and territorial questions and to

actively look for ways to address them through local

transformation strategies. ° Firstly, GOLD VI seeks to reframe the ways that

inequalities are understood in order to capture

Although inequalities have been increasingly acknowl- the complexity and drivers of current disparities,

edged as a global challenge, shaped by structural condi- moving beyond narrowly monetarized definitions of

tions at multiple scales, coordinated actions at the local equality to include principles related to distribution,

level are indispensable to tackle their territorial manifes- recognition, participation and solidarity.

tations, as well as many of their underlying causes. The

° Secondly, as an action-oriented report, GOLD VI

Durban Declaration of 2017 reconfirmed United Cities

seeks to highlight the challenges and alternatives

and Local Governments (UCLG) as an equality-driven

facing urban and territorial governance in the

movement, recognizing local action as being at the front

democratic pursuit of urban and territorial equality.

line in the fight to address inequalities. Local knowledge

Governance-related questions are central and will

and practices are crucial for articulating meaningful

be approached by identifying current policy and

and effective responses to inequalities that are locally

planning actions and through joint interventions

experienced. Addressing inequalities therefore requires

that recognize the agency of LRGs in consolidating

collaboration at multiple scales, and the actions of LRGs

pathways to equality at different scales.

are a key place to start.

° Thirdly, GOLD VI seeks to highlight inequalities within

The role of LRGs in reframing and responding to debates about the role of LRGs in the accomplish-

inequalities is fundamental for at least three main ment of global development agendas, including

reasons. Firstly, local authorities are at the forefront equality and justice in agendas such as the SDGs,

of the territorial manifestations of global phenomena the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, the New

and therefore tend to have better knowledge about how Urban Agenda, the Sendai framework, the Addis

people experience inequalities on a day-to-day basis. Ababa Action Agenda for Financing Sustainable

Secondly, LRGs have the capacity to act and mobilize Development, the United Nations Convention on

efforts and collaboration between the public, private and the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against

civil society actors with a presence in their territories, Women, and the International Convention on the

working at different scales. Thirdly, they also have the Elimination of all Forms of Racial Discrimination.

potential to sustain action overtime and to ensure more

direct accountability in the long term. The COVID-19

crisis has highlighted the critical role played by LRGs

in promoting and guaranteeing local well-being, food

5 For a compilation of LRG responses to the pandemic, see Metropolis,

security, and the continuity of public services, and also

UCLG, and AL-LAs’ “Cities for Global Health” platform, 2022, https://bit.

ly/3wcIm2E; and the “Beyond the Outbreak” knowledge hub co-led by UCLG,

3 World Bank, “COVID-19 to Add as Many as 150 Million Extreme Poor by 2021,” Metropolis, and UN-Habitat, 2020, https://bit.ly/3MP1f1A.

2020, https://bit.ly/3qbpoWu. 6 Stephanie Butcher et al., “Localising the Sustainable Development Goals:

4 UN-Habitat, “World Cities Report 2016: Urbanization and Development - An Urban Equality Perspective,” International Engagement Brief #2 (London,

Emerging Futures,” 2016, https://bit.ly/3qaczeY. 2021), https://bit.ly/3u47cz3.

18 GOLD VI REPORT

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 18 20-09-22 17:43

1 Urban and territorial inequalities

GOLD VI seeks to advance these strategic objectives readers to embrace a multidimensional understanding

by promoting a participatory and collaborative meth- of inequalities, and to reflect upon the intertwined

odology that has been essential for the coproduction relationship between inequality and other develop-

of this Report. In this process, there has been space ment challenges. Section 3 then briefly introduces

for the voices, experiences and knowledges of a the concept of “pathway”, which is the key structuring

diverse range of actors – including local and regional notion for GOLD VI. Section 4 describes the process

government representatives, civil society networks, behind the production of GOLD VI, which was shaped

international agencies and academics. by a collective process of coproduction that relied on

the experiences and knowledges of multiple actors.

This introductory chapter sets the scene for the journey Finally, Section 5 of this chapter explains to the reader

through GOLD VI. In Section 2, the chapter discusses how to navigate through this Report and its different

the meaning of “urban and territorial equality”, inviting pathways and chapters.

Source: Sam Okechukwu, Nigeria Slum / Informal Settlement Media Team, Know your City TV.

A peaceful protest is held by persons living with disabilities at The Lagos State House of Assembly

following the sudden blanket ban on keke and okada (tricycles and motorbikes).

01 INTRODUCTION 19

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 19 20-09-22 17:43

2 Defining “urban and territorial equality”

2 Defining “urban

and territorial

equality”

Urban and territorial inequalities are widening. This The COVID-19 pandemic has made the long-term crisis

is depriving vast sectors of the population of their of care more visible than ever, exposing the weaknesses

basic rights and a decent standard of living, while of “widening and persistent inequality” in almost every

creating collective risks and also social, economic and society.10 In terms of democracy, researchers have

environmental obstacles to development. Inequalities shown that “the higher the inequality, the more likely we

are growing almost everywhere. As Oxfam highlighted are to move away from democracy”.11 Understanding this

in 2020 in its examination of the profound injustice intertwined relationship between inequality and other

in the global distribution of wealth: “inequality is not development-related challenges, GOLD VI specifically

inevitable – it is a political choice”.7 The world’s richest examines inequalities that are urban and territorial

1% have more than twice the wealth of 6.9 billion people, in nature.

or 90% of the world population; this situation is also

mirrored in urban and territorial contexts.

Inequality is not only an urgent problem and an ethical

and political challenge in itself; it is also a driver of

several other global challenges. Addressing inequalities

is an urgent task if we are to tackle most of the chal-

lenges that humanity is currently facing in a sustainable

way. For example, in dealing with the climate emergency,

the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate

Change (UNFCCC) has argued that the “combination of

climate change and inequality increasingly drives risk”.8

In the case of migration-related challenges, the Organ-

isation for Economic Co-operation and Development

(OECD) has acknowledged that “migration is a highly Source: Jason Leung, Unsplash.

visible reflection of global inequalities whether in terms San Francisco, CA, USA.

of wages, labour market opportunities, or lifestyles”.9

7 Oxfam International, “A Deadly Virus: 5 Shocking Facts about Global 10 UNDP, “Coronavirus vs. Inequality.”

Extreme Inequality,” 2020, https://bit.ly/3ifdciY.

11 Branko Milanovic, “The Higher the Inequality, the More Likely We Are to

8 UNFCCC, “Combination of Climate Change and Inequality Increasingly Move Away from Democracy,” The Guardian, 2017,

Drives Risk,” News, 2018, https://bit.ly/3CLCij9. https://bit.ly/36lAWiQ.

9 Heaven Crawley, “Why Understanding the Relationship between Migration

and Inequality May Be the Key to Africa’s Development,” OECD Development

Matters, 2018, https://bit.ly/3JkypE9.

20 GOLD VI REPORT

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 20 20-09-22 17:43

2 Defining “urban and territorial equality”

Box 1.1

Equality and equity

It is important to clarify the much-discussed differences between the concepts of “equality” and “equity”. In the urban

field, “inequality” is generally used as a descriptive term to refer to differences in people’s capabilities for achieving

well-being; these differences stem from unevenness in their access to the opportunities required to fulfil their

needs and aspirations. On the other hand, “inequity” refers to a lack of fairness and therefore to questions of social

justice.12 GOLD VI uses the term “equality” as a way to embrace both descriptive and justice-related orientations and

to reinforce the pursuit of equality as a common aspiration. Equality is understood as a vision that should always be on

the horizon of actions undertaken by LRGs and which should serve to advance the collective efforts of “equality-driven

movements”, such as UCLG. In GOLD VI, the notion of equality also enables us to discuss reforms and distributive

responses that can help address actual disparities experienced by people. GOLD VI understands that it is only by

tackling the discursive, relational and material inequalities associated with both processes and outcomes that the

cause of social justice can be advanced.

What do we mean The first principle concerns the distribution dimen-

sion of equality; it refers to equitable access to the

by urban and material conditions that ensure a dignified quality

territorial equality? of life for all, including equitable access to income,

decent work, health, housing, basic and social services,

connectivity, safety and security for all citizens in a

Although most definitions of equality tend to focus on sustainable manner. Equitable distribution is not,

the distribution of wealth and income, over the last however, sufficient to achieve urban equality unless it is

few decades, several voices have called for a more accompanied by the reciprocal recognition of multiple

multidimensional understanding of equality, based intersecting social identities across class, gender, age,

on the principle of justice. Drawing on these debates, race, ethnicity, religion, ability, and sexuality, among

GOLD VI proposes a shift in the understanding of others. As, historically speaking, populations with

equality that could help build pathways for action for certain identities have been misrecognized, oppressed

LRGs: from a singular focus on measuring (in)equality or rendered invisible, promoting reciprocal recognition

to one based on capturing the drivers that perpetuate it; means that citizens and governance structures must

from a universal definition of inequality to one that also recognize this diversity when collectively organizing,

recognizes the context-specificity of how equality and coproducing knowledge, and planning and managing

inequality are locally experienced; and from sectorial urban and territorial activities. This recognition is of

delivery approaches to cross-sectorial performance particular importance when populations are affected

principles. GOLD VI works with a definition of urban by socio-economic and ecological processes, political

and territorial equality that has four key, inter-related, conflict or environmental disasters that may result in

performance principles: equitable distribution; recip- migration, displacement and/or other forms of margin-

rocal recognition; parity political participation; and alization. The third principle of urban and territorial

solidarity and mutual care (Figure 1.1). equality is parity political participation. This refers

to creating equitable conditions that: allow the demo-

12 Carolyn Stephens, “Urban Inequities; Urban Rights: A Conceptual Analysis and Review of Impacts on Children, and Policies to Address Them,” Journal of Urban

Health 89, no. 3 (2012): 464–85; Alexandre Apsan Frediani, Cities for Human Development: A Capability Approach to City-Making (Rugby: Practical Action Publishing,

2021).

01 INTRODUCTION 21

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 21 20-09-22 17:43

2 Defining “urban and territorial equality”

Figure 1.1

Principles of urban and territorial equality

Guaranteeing the provision Equitable access to

of care, prioritizing mutual the material conditions

support and relational that ensure a dignified

responsibilities between quality of life for all,

citizens, and between including equitable

citizens and nature, access to income,

actively nurturing civic life decent work, health,

Solidarity and Equal housing, basic and social

mutual care distribution services, connectivity,

safety and security

Citizens and governance Equitable conditions that

structures recognizing allow the democratic,

multiple claims and

Reciprocal Parity political inclusive and active

intersecting social

recognition participation engagement of citizens

identities, regardless and their representatives

of class, gender, age, in processes of urban and

race, ethnicity, religion, territorial governance, and

ability and sexuality, in thinking up, deliberating

amongst others upon and taking decisions

about current and

future trajectories

Source: authors, based on the KNOW proposal

cratic, inclusive and active engagement of citizens Rights-based approaches lie at the heart of these four

and their representatives in processes of urban and principles of urban and territorial equality; these are

territorial governance; help to address conflict; and approaches that challenge and seek to transform power

fully encompass and promote the collective imagination, relations in order to guarantee human rights for all.

deliberations and decisions about current and future Likewise, applying these principles relies on recognizing

urban and territorial trajectories. Finally, the fourth a diverse knowledge base of personal and collective

principle refers to fostering solidarity and mutual care. experiences of inequalities and acknowledging different

This entails moving towards cities and territories that voices and sources of knowledge relating to the promo-

guarantee the provision of care and that prioritize tion of equality.

promoting mutual support and relational responsibil-

ities between citizens, and between citizens and the

natural environment, by actively nurturing the civic life

of cities and territories.13

13 For further reflections on these four principles, see Christopher Yap,

Camila Cociña, and Caren Levy, “The Urban Dimensions of Inequality and

Equality,” GOLD VI Working Paper Series (Barcelona, 2021).

22 GOLD VI REPORT

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 22 20-09-22 17:43

3 Pathways as trajectories of change

3 Pathways as

trajectories

of change

Understanding equality in this multidimensional divide, Connecting has become a pathway to help

perspective invites LRGs to find different ways to tackle ensure adequate physical and digital connectivity for

inequalities. LRGs act through different institutional everyone. In the face of an undeniable climate emer-

mechanisms, through which they galvanize policies, gency, Renaturing has emerged as an approach for

programmes, planning, finance, organizational tools creating a renewed and sustainable relationship with

and local alliances. These instruments allow them to the ecosystem and natural resources. As urban and

find ways to advance in one or more dimensions to territorial economies have become more precarious

make cities and territories more equitable for everyone. and inequalities between territories have increased,

GOLD VI understands these different routes as pathways Prospering can help to create decent and sustainable

to urban and territorial equality. These pathways are livelihoods that are appropriate for diverse conditions

trajectories for change. Creating pathways that promote and different social identities. As we encounter global

more equitable futures involves taking strategic and local threats to democracy, and growing calls

decisions that include both material and discursive to improve existing mechanisms of representation,

practices. Pathways help define the collective criteria Democratizing is a vehicle that will ensure more inclu-

required for decision making and working towards a sive governance that recognizes all voices, and espe-

common vision. cially those that have been historically marginalized.

Finally, the incremental and cumulative effect of joint

The focus on pathways in GOLD VI acknowledges that action coordinated between these different agendas

addressing structural inequalities and current unsus- will produce pathways to equality. Together, they can

tainable development trends requires the collective reach tipping points for radical positive transformations.

construction of alternative channels of action. Faced This will be only possible through appropriate policies

by the housing crisis and the financialization of capable of upscaling and expanding these transfor-

housing, land and services, Commoning has emerged mative changes.

as a pathway for enhancing collective practices and

guaranteeing everyone access to decent housing and These trends are framed and further discussed in

basic services. As we have witnessed a generalized Chapter 2 of this Report. Thereafter, these pathways

crisis in social protection, Caring has become a have been used as a structuring element in GOLD

response through which to prioritize the provision of VI. The current Report provides concrete examples,

care for different groups and also for those who care highlights ongoing debates and examines the experi-

for others. By bridging evident gaps in mobility and ences of LRGs working closely with other stakeholders,

access to infrastructure, as well as a growing digital such as organized civil society. The pathways seek to

01 INTRODUCTION 23

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 23 20-09-22 17:43

3 Pathways as trajectories of change

provide concrete tools to help LRGs when they are use these pathways to promote the different principles

looking to define their own routes to change. The of equality. Above all, the pathways and their cocon-

pathways discussed in GOLD VI do not seek to provide struction lead us to think more about the question of

all the answers, but rather to present alternative ways governance. With this in mind, the discussion about

of jointly constructing the conditions necessary to pathways will be expanded in Chapter 3 of this Report,

make cities and territories more equal. In this way, the where urban and territorial equality as a question of

pathways can become collective vehicles for promoting governance will also be considered.

transformative action. By creating capabilities and

mechanisms that work at multiple scales, LRGs can

Source: Alan Veas, Unsplash.

Santiago, Chile.

24 GOLD VI REPORT

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 24 20-09-22 17:44

4 GOLD VI coproduction: An engaged international process

4 GOLD VI

coproduction:

An engaged

international process

A multidimensional understanding of equality involves 1.2). The structure has been created by the GOLD VI

questioning how knowledge is produced, whose voices Steering Committee, which is composed of members

are considered, and the ways in which global agendas of UCLG and the Knowledge in Action for Urban Equality

can be collectively coproduced, considering the experi- (KNOW) team.14 From the beginning, the Steering

ences of different actors through just and accountable Committee envisaged a Report that could offer more

processes. Acknowledging the production of knowl- than just a snapshot of current inequalities. Instead,

edge as an equality challenge in itself, the method- building on an understanding of the structural drivers

ology behind GOLD VI has sought not only to produce of inequality and their manifestations in urban and

rigorous and relevant output, but also to facilitate territorial areas, the Report seeks to propose routes

a rich process of exchange and collective agenda for transformative action. In order to discuss these

setting. Through a series of workshops, meetings, different routes, or pathways, each chapter of GOLD VI

and coproduction mechanisms, GOLD VI has sought has been produced by specific chapter curators, with

to support and strengthen multistakeholder dialogues recognized experience in their respective fields, from

and to ensure the fullest possible participation and different countries, disciplines and institutions. We

involvement of the UCLG network and its members, have called these colleagues “chapter curators”, rather

civil society coalitions, and researchers and academics. than just “authors”, because each of them has brought

From the beginning of this process, this approach has their own approach and experience to the Report. In

been regarded as being as relevant as the output itself.

GOLD VI has sought to bring a perspective of equality

14 Knowledge in Action for Urban Equality (KNOW) is a four-year programme

to a process aimed at strengthening local learning and

funded by ESRC under the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) of the

alliances for action, facilitating translocal learning, and United Kingdom. Led by Professor Caren Levy, of the Bartlett Development

collaborating within international networks. Planning Unit (DPU) of University College London, KNOW is a global

consortium of researchers and partners which includes 13 institutions

from nine different countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The GOLD

In order to enable this process, GOLD VI has established VI Steering Committee includes three members of the KNOW team: Prof

a specific governance structure that facilitates this Caren Levy, Dr Alexandre Apsan Frediani and Dr Camila Cociña. More

cross-learning and coproduction experience (Figure information at

https://www.urban-know.com.

01 INTRODUCTION 25

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 25 20-09-22 17:44

4 GOLD VI coproduction: An engaged international process

writing up the chapters, they have collaborated with,

and coordinated the work of, a constellation of actors

who have contributed to building the central arguments

of the chapters.

These contributions constitute a key element of the

Report, as they not only provide information about

grounded experiences, but also key insights that help

shape future pathways towards equality. Each chapter

includes contributions from four different kinds of

sources:

° the UCLG Network, with contributions from 17

teams, committees, fora, communities of practice

and partner networks and the direct participation of

its members. These draw on grounded experiences

from local and regional governments that ensure a

good balance of different geographies and territories;

° civil society networks, which draw on the experi-

ences of the members of mainly six global coalitions:

Asian Coalition for Housing Rights (ACHR), CoHabitat

Network, Global Platform for the Right to the City

(GPR2C), Habitat International Coalition (HIC), Slum/

Shack Dwellers International (SDI), and Women in

Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing

(WIEGO);

° KNOW partners, from 12 research institutions, which

draw on the collective experiences and lessons

learned from their activities in cities in Africa, Asia

and Latin America; and

° other academics and researchers working on

issues relevant to the Report, from several different

universities and research institutions.

Over the last two years, GOLD VI organized several

collective workshops, which were held online due to

the restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, Source: Jack Prommel, Unsplash.

La Paz, Bolivia.

and various feedback and exchange sessions. They

allowed the collective crafting of key messages, topics

and cases, in which each set of participants contributed

to the final product that you are now reading. The virtual

workshops were spaces for discussing and exchanging a Pathways to Equality Cases Repository where the CBCs

views, validating key messages, and agreeing the are also available.15 Through this process, we hope that

content and focus of the 66 case-based contributions the legacy of GOLD VI will transcend the content of

(CBCs) and 22 thematic or issue-based contributions this Report. This legacy will also lie in strengthening

(IBCs) which were produced for inclusion in GOLD VI. relationships between organizations that act locally

The chapters of this Report draw directly on the wealth and which have generated knowledge and responses

of knowledge and experience included in these contri- to urban and territorial equality in different territories.

butions. Being aware that some of these contributions

could be of interest to the general public, UCLG and

KNOW launched a GOLD VI Working Paper Series that 15 To review the full content of the GOLD VI Working Papers Series and the

enables access to these IBCs in their full versions, and Pathways to Equality Cases Repository, visit

https://gold.uclg.org/reports/gold-vi.

26 GOLD VI REPORT

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 26 20-09-22 17:44

4 GOLD VI coproduction: An engaged international process

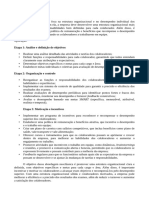

Figure 1.2

Organization of the GOLD VI process

GOLD VI Steering Committee UCLG NETWORK, ITS MEMBERSHIP AND PARTNERS

Commission on Local Metropolis

Economic Development UCLG Accessibility

Committee on Culture UCLG Digital Cities

Committee on Social Inclusion, UCLG Ecological Transition

Edgardo Bilsky [UCLG GOLD] Participatory Democracy

UCLG Learning

Caren Levy [KNOW-DPU] and Human Rights

UCLG Migration

Anna Calvete Moreno [UCLG GOLD] Global Fund for Cities Development (FMDV)

UCLG Peripheral Cities

Camila Cociña [KNOW-DPU] Global Social Economy Forum

UCLG Regions

Intermediary Cities

Ainara Fernández Tortosa [UCLG GOLD] UCLG Global Observatory on Local

International Association

Amanda Fléty Martínez [UCLG-CSIPDHR] of Educating Cities Democracy and Decentralization (GOLD)

Alexandre Apsan Frediani [KNOW-IIED] International Observatory on UCLG Women

Cécile Roth [UCLG GOLD] Participatory Democracy

SUPPORT:

Camille Tallon [UCLG GOLD]

CIVIL SOCIETY NETWORKS

Nicola Sorsby [KNOW-IIED]

Asian Coalition for Housing Rights (ACHR) UrbaMonde, Co-Habitat network

Jaume Puigpinós [UCLG-CSIPDHR]

CoHabitat Network Cultural Occupation's Bloc - Culture

Movement of the Peripheries

Chapter Curators Global Platform for the Right

to the City (GPR2C) World Enabled

STATE OF INEQUALITIES Habitat International Coalition (HIC) CISCSA Ciudades Feministas

José Manuel Roche

Slum/Shack Dwellers International (SDI) Asiye eTafuleni

COMMONING Women in Informal Employment:

Barbara Lipietz [DPU] Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO)

Gautam Bhan [IIHS]

CARING

KNOW PARTNERS

Olga Segovia [SUR]

María Ángeles Durán [Consejo Superior ACHR, Thailand Makerere University, Uganda

de Investigaciones Científicas] Ardhi University, Tanzania PUCP, Peru

Centre for Community Sierra Leone Urban Research

CONNECTING

Initiatives, Tanzania Center (SLURC)

Julio Dávila [DPU]

Regina Amoako-Sakyi [U. of Cape Coast] CUJAE, Cuba The Bartlett Development

Indian Institute for Human Planning Unit (DPU), UCL

RENATURING Settlements (IIHS), India The University of Melbourne

Adriana Allen [DPU] Institute of Global Prosperity (IGP), UCL The University of Sheffield

Mark Swilling [U. of Stellenbosch]

Isabelle Anguelovski [Barcelona

Lab for Urban Environmental OTHER ACADEMIC AND RESEARCH INSTITUTIONS

Justice and Sustainability]

International Institute for Environment Institut de Recherche pour

PROSPERING and Development (IIED) le Développement (IRD)

Edmundo Werna PEAK Urban Da Nang Architecture University

Stephen Gelb [Overseas

Universidad Central de Venezuela

Development Institute]

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

DEMOCRATIZING University of Greenwich

Alice Sverdlik [IIED] Raoul Wallenberg Institute

Diana Mitlin [U. of Manchester]

01 INTRODUCTION 27

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 27 20-09-22 17:44

5 How to read this Report

5 How to read

this Report

The GOLD VI Report provides action-oriented reflec- The subsequent chapters are organized around six

tions. It explores the conditions and instruments that pathways:

can be used for the cocreation of pathways to equality.

° Chapter 4 focuses on the Commoning pathway. This

Seeking to avoid the reproduction of sectoral and siloed

relates to the governance, planning and provision

approaches to equality, the chapters are structured to

of access to housing, land and basic services, and

capture different sets of strategies that LRGs and local

to ways in which LRGs can promote approaches

partners are adopting to tackle inequalities. The titles

that focus on collective action and promote greater

of the chapters refer to verbs or actions that LRGs are

urban equality.

taking in this direction: pathways to address different,

but interconnected, agendas. Table 1.1 shows the ° Chapter 5 centres on the Caring pathway. This refers

diversity of themes that can be found in each chapter. to the multiple actions that can be used to promote

the provision of care to different groups within

Chapter 2 gives an overview of the current State of society. This can be achieved through providing

inequalities, including a discussion about trends safety nets and building solidarity bonds. It also

regarding inequality and the challenges they pose examines the ways in which LRGs can promote caring

to LRGs. practices through social policies, in fields such as

education and health, which provide support both to

Chapter 3 focuses on Governance and pathways to those in need of it and to those who have historically

urban and territorial equality and explains why equality “taken care” of others.

should be framed as a question of governance. It also ° Chapter 6 discusses the Connecting pathway.

focuses on the importance of understanding local These pathways include multiple interventions and

government institutional frameworks, decentralization, programmes that increase linkages both between

and multilevel governance structures, and proposes and within cities and among their citizens. The

a rights-based approach as the basis for governance chapter also examines the role of LRGs in the gover-

to promote equality. This chapter also explains the nance and planning of more equitable transport,

notion of pathways and institutional capabilities and infrastructure and digital connectivity.

their value as practical approaches that enable LRGs

° Chapter 7 presents the Renaturing pathway. This

to tackle inequalities.

refers to the governance and planning of a renewed

28 GOLD VI REPORT

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 28 20-09-22 17:44

5 How to read this Report

and more sustainable relationship between natural

and urban systems. It places specific emphasis on

decoupling economic development from resource

use and promoting more just ecological transitions

to net zero carbon systems, risk reduction and urban

resilience.

° Chapter 8 discusses the Prospering pathway. This

chapter focuses on such issues as: livelihoods,

decent work and worker skills, enterprise develop-

ment and resilience, and the spatial concentration

of productive activities. It looks at the role of LRGs

in the governance and expansion of productive,

income-generating activities carried out in the urban

space and recognizes the formal and informal systems

that contribute to urban and territorial equality.

° Finally, Chapter 9 discusses the Democratizing

pathway. It focuses on the challenges and oppor-

Source: Programa de Mejoramiento Integral de Barrios, Secretaría de Medio

tunities facing LRGs as they seek to implement Ambiente, Vivienda y Desarrollo Rural.

meaningful participatory processes, to democratize Alcaldía de Bello, Colombia.

decision-making and to unpack the asymmetries of

power. In doing so, it also looks at the underpinning

trends that affect processes of democratization.

Finally, Chapter 10 presents the Conclusions and the conjunction of LRGs with other actors, including civil

final recommendations of GOLD VI and its quest to society, which have worked together to plan pathways

promote urban and territorial equality. It discusses that can advance equality. The boxes in each chapter

the cross-cutting challenges related to upscaling the provide concrete examples, definitions of concepts,

different pathways, and the importance of establishing and key information about financial mechanisms related

partnerships and financial mechanisms that draw on to these pathways. These boxes, alongside the GOLD

collaboration between different levels of government, VI Working Papers Series and Pathways to Equality

including the national, regional and local levels. The Cases Repository, provide further information which

conclusions propose that LRGs should consider five is complementary to the Report content.

key principles in their quest for equality:

GOLD VI is a collective attempt to define the role of

° a rights-based approach, undertaken from an inter-

LRGs within the global challenge of addressing inequal-

sectional perspective;

ities and recognizes the commitment of UCLG to the

° the recognition of the spatial dimension of inequalities; cause of promoting greater equality. It also highlights

° a new culture of subnational governance for deep- the potential offered by interconnected local trans-

ening democracy; formation strategies, and the opportunities that they

bring for building pathways to change at different scales.

° adequate fiscal and investment architecture; and

Global sustainability agendas need the full commitment

° practical and transformational engagement with of LRGs if they are to be delivered. As the different chap-

the past, present and future. ters of this Report outline, a focus on equality calls for

a rethinking of urban and territorial governance, both

These principles, and their interactions within the in terms of its vision and its procedures. At a time at

different pathways discussed in GOLD VI, provide the which the challenges associated with ongoing global

framework for the political recommendations that close and local crises are likely to grow and intensify in their

the Report. complexity, the principles of equality and human rights

offer guiding values for the action of institutions and

Each of the chapters of GOLD VI presents a combination actors at different scales. LRGs, working in tandem

of debates, reflections and concrete experiences that with other levels of government and with civil society,

examine how different spheres of governance can help have both the opportunity and ethical responsibility

promote greater equality. Central to these efforts are to become active and leading voices in this endeavour.

01 INTRODUCTION 29

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 29 20-09-22 17:44

5 How to read this Report

Table 1.1

How to read this Report: The sectorial agendas discussed in the different chapters

Sectors/themes Pathway chapters

Housing and land Commoning | Caring | Renaturing | Prospering

Infrastructure Commoning | Connecting | Renaturing

Health Caring | Renaturing

Education Caring | Prospering

Service delivery Commoning | Caring | Connecting | Democratizing

Transport and mobility Connecting | Renaturing

Discrimination and inclusion Commoning | Caring | Connecting | Renaturing | Prospering | Democratizing

Culture Commoning | Democratizing

Migration Caring | Democratizing

Food security Caring | Renaturing | Prospering

Urban economy Connecting | Prospering

Income generation, decent Renaturing | Prospering

work and livelihoods

Participation and democracy Commoning | Democratizing

Data collection and management Commoning | Connecting | Democratizing

Public spaces Commoning | Caring | Connecting

Urban and territorial finance Commoning | Caring | Connecting | Renaturing | Prospering | Democratizing

Source: authors

30 GOLD VI REPORT

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 30 20-09-22 17:44

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 31 20-09-22 17:44

02

State of

inequalities

32 GOLD VI REPORT

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 32 20-09-22 17:44

Source: Donatas Dabravolskas,Shutterstock.

Aerial view of Favela da Rocinha, the biggest informal settlment in Brazil, on the mountain in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

02 STATE OF INEQUALITIES 33

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 33 20-09-22 17:44

Chapter Curator José Manuel Roche

(Independent consultant)

Contributors

This chapter has been produced based on the following valuable contributions, which are available

as part of the GOLD VI Working Paper Series and the Pathways to Equality Cases Repository:

The Urban Dimensions of Christopher Yap

Inequality and Equality Camila Cociña

Caren Levy

(The Bartlett Development Planning

Unit, University College London)

The State of Inequalities in Sub- Wilbard J. Kombe

Saharan African and Asian Cities Neethi P.

Keerthana Jagadeesh

Athira Raj

(Ardhi University and IIHS Bangalore)

The Differential Economic Geography Philip McCann

of Regional and Urban Growth and (Sheffield University Management School)

Prosperity in Industrialised Countries

34 GOLD VI REPORT

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 34 20-09-22 17:44

abstract

Abstract

The world has experienced incredible transformations an increase in territorial inequalities in some countries.

in the decades straddling the new millennium. Although The financialization of urban infrastructure and ghet-

these include the reduction of extreme poverty, toization of parts of some cities are good examples of

concerns remain that progress has not been evenly how circulatory flows of capital are boosting certain

distributed and that inequalities are increasing. Recent urban inequalities.

shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, have made this

problem worse. This chapter provides an overview of the Today, there is wide consensus that well-being, poverty

state of inequalities in cities and regions, contextualizing and inequalities are multidimensional in nature. The

other chapters in the GOLD VI Report. dynamics behind inequalities in those non-monetary

dimensions have their own specificities which, in

Growing concern over the state of global inequalities led turn, call for different policy responses at the national

the UN Member States to specifically agree to reducing and local levels. This chapter provides an overview of

inequalities as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable inequalities within a set of SDG dimensions that are

Development. One explicit goal, to “reduce inequality most relevant to the local context. These include: (a)

within and among countries”, was incorporated as basic infrastructure and services; (b) spatial planning,

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 10. The 2030 land management and housing; (c) education, health

Agenda also makes a pledge to “leave no one behind” and social services; (d) transport, mobility and public

which, in practice, implies reducing inequalities between space; and (e) employment and decent work.

different social groups. These agreements have been

ratified by the New Urban Agenda (NUA). Through its Inequalities compound and exacerbate one another,

emphasis on localization, the 2030 Agenda advocates especially for those belonging to more than one margin-

an inclusive and localized approach to development. alized group; this often intensifies the severity of their

impacts and how they are experienced. Intersecting

The relationships between urbanization and inequal- inequalities are relational, and it is essential to under-

ities are not straightforward. While generalizing is stand the power structures that reproduce them. The

difficult, the overall pattern is that cities tend to be pledge to leave no one behind, made in the 2030 Agenda,

more prosperous and unequal, while at the same time calls for societies to reduce inequalities in outcomes

concentrate a large share of national poverty. Urban across different dichotomies and social groups.

inequalities manifest themselves differently in each city

and world region. Income inequalities are (re)produced

through interactions between global and local processes,

shaped by local socio-cultural identities, institutional

differences at the national level, and local social and

economic histories.

The picture is far from homogenous, as countries,

territories and cities across the world have notably

different levels of inequalities. While income inequality

between countries has been closing, inequalities within

countries have been on the rise since the 1980s. Some

metropolitan cities and territories have also dispropor-

tionately benefited from globalization, which has led to

35

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 35 20-09-22 17:44

o

Source: AsiaTravel, Shutterstock.

Inequalities in exposure to flooding risks between Jakarta_s poorer and richer households, Indonesia.

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 36 20-09-22 17:44

The richest 10% 52% Due to the COVID-19 pandemic: Globalization has come at the expense of increased territorial inequalities. The Income inequalities rangeg

absolute gap between the mean per capita income of high- and low-income

of the global population of global income a

countries increased from:e 100 (more unequal)

100m people

have fallen into extreme poverty. 42,800 USD in 2018

earns

This number is projected to remain well above

27,600 USD in 1990

South Africa | 63

90

Namibia | 59.1 80

pre-pandemic levels, especially in Africa and Brazil | 53.4

Latin America.b $ $ Zambia | 57.1

70

Colombia | 51.3

Chile | 44.4

Whereas 150m people in 2019 690m people While the top 1%’s share of income was close to 10% in Western Europe and

In high-income countries,

60

have insufficient food the USA in 1980, it has since risen to 12% and 20%, respectively, in 2016.

consumption. c in early 2022 840m people Globally, income inequalities are on the rise, with inequalities within countries

such as the USA | 41.4 50

The poorest 50% 8% now even greater than inequalities between countries.f 40

of the global population of global income a Denmark | 28.2

Gender inequalities remain considerable at the global level, and progress within The % of total income share held by the richest 1%: 30 Norway | 27.6

countries is too slow. The share of total labour income by gender is:d 2016 Finland | 27.3

20% Japan | 32.9 20

earns Czech Republic

31% 69% 1990 TOP 12%

Pakistan & Bangladesh | 31.6 & Slovakia | 25

1% $

Republic of Korea | 31.4 10

$ Slovenia | 24.6

35% 65% 2015-2020

1980 10% 10%

0 (less unequal)

Gini

coefficient

Global inequalities have significantly increased during the past years Countries experience inequalities differently

State of inequalities

Cities and the urban population are growing fast, creating complex inequality challenges

Gini indexes at the city level Growing inequalities

55% Inequalities do not manifest themselves in the same way everywhere. Oftentimes, they result from political

(4.2bn people) 2018 50

Cities with Gini indexes of 50 and above have choices, in which LRGs have a strategic role. Although there is a correlation between growing urbanization

been identified in cities in Southern Africa, and growing inequalities within cities, causation between the two has not yet been determined.j

of the world’s population lived in cities in 2018.h Latin America and North America.i

90% Brazil, from 55.6 to 51.9:

of this new urban Asian cities appear to be less unequal, Between 2006 and 2016, urban inequalities in Brazil (Gini index) fell but increased

population is expected to 40 with Gini indexes below 40, as do European again after a change in national policies. In 2021: j

live in Asia and Africa.h cities, with values normally below 40 (except

27 TIMES

68% London, which is above 50).i The poorest 50% LESS than the richest 10%

of the population earned of the population.

(6.7bn people) 2050

of the world’s population is expected to live in cities by 2050.h ! Typically, the greatest inequalities are found

in the largest cities.i

UCLG-GOLD-VI_EN_LIBRO_v3.indd 37 20-09-22 17:44

1 Introduction

1 Introduction

The world has experienced an incredible transforma- Unfortunately, concerns remain that progress has

tion over the decades straddling the new millennium. not been evenly distributed and inequalities are still

Positive stories include the rise of emerging economies rising. It is important to note that inequalities within

and the progress made in reducing extreme poverty countries have significantly increased since the 1980s.6

in most countries around the world. China alone lifted In particular, the accumulation of wealth by global

74.5 billion people out of extreme poverty between multimillionaires has grown to extraordinary levels,

1990 and 2016.1 Rwanda saw a sharp fall in under-five with the 1% having captured 38% of all the additional

child mortality between 1990 and 2019, from 150 to 34 wealth accumulated since the mid-1990s, whereas

under-five deaths per 1,000 live births.2 The number the bottom 50% of the world’s population has accrued

of child marriages has reduced considerably, partic- only 2%.7 In many countries, globalization has come