Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lost in Thought - Duane Hanson

Lost in Thought - Duane Hanson

Uploaded by

Yasmin WattsCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Francis Ponge - The Voice of ThingsDocument94 pagesFrancis Ponge - The Voice of ThingsKatten Katt100% (8)

- What Is Research and It's CharacteristicsDocument2 pagesWhat Is Research and It's CharacteristicsNirvana Nircis94% (18)

- English Learners Academic Literacy and Thinking For Princ MeetingDocument30 pagesEnglish Learners Academic Literacy and Thinking For Princ MeetingAntonio HernandezNo ratings yet

- Day Three Madeline Hunter Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesDay Three Madeline Hunter Lesson Planapi-269729950No ratings yet

- Dreamed Up Reality: Diving into the Mind to Uncover the Astonishing Hidden Tale of NatureFrom EverandDreamed Up Reality: Diving into the Mind to Uncover the Astonishing Hidden Tale of NatureRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Marcia S Cavalcante Schuback - Time in Exile - in Conversation With Heidegger, Blanchot, and Lispector (Suny Series, Intersections - Philosophy and Critical Theory) - State Univ of New York PR (2020)Document184 pagesMarcia S Cavalcante Schuback - Time in Exile - in Conversation With Heidegger, Blanchot, and Lispector (Suny Series, Intersections - Philosophy and Critical Theory) - State Univ of New York PR (2020)rubia_siqueira_3No ratings yet

- Dismantling Art and Literature - by Subroto MukerjiDocument9 pagesDismantling Art and Literature - by Subroto MukerjiSubroto MukerjiNo ratings yet

- Cixous Lertxundi and The Fruits of The FeminineDocument16 pagesCixous Lertxundi and The Fruits of The FeminineNadiaNo ratings yet

- 39-1 3thackerDocument3 pages39-1 3thackerscottpilgrimNo ratings yet

- Ana Baraga Diploma Postajam Zival BranjeDocument58 pagesAna Baraga Diploma Postajam Zival BranjeAna BaragaNo ratings yet

- 2017 Article 629Document6 pages2017 Article 629Maria Fernanda HiguitaNo ratings yet

- Palimpsestic Veils of Desire in Jeanette Winterson's Written On The BodyDocument109 pagesPalimpsestic Veils of Desire in Jeanette Winterson's Written On The BodyRaouia ZouariNo ratings yet

- 1 Kilometro en La Ciudad!: Framework!Document8 pages1 Kilometro en La Ciudad!: Framework!Camila Come CarameloNo ratings yet

- FranzDocument9 pagesFranzNguyễn Vân QuỳnhhNo ratings yet

- Still Life: A User's Manual: Narrative May 2002Document17 pagesStill Life: A User's Manual: Narrative May 2002Daisy BogdaniNo ratings yet

- TH e Anthropology of Empty SpacesDocument9 pagesTH e Anthropology of Empty SpacesmadNo ratings yet

- Taussig, Venkatesh, Rev de Pe NetDocument21 pagesTaussig, Venkatesh, Rev de Pe NetChrista GNo ratings yet

- The Lesser Existences Étienne Souriau, An Aesthetics For The Virtual (David Lapoujade, Erik Beranek) (Z-Library)Document132 pagesThe Lesser Existences Étienne Souriau, An Aesthetics For The Virtual (David Lapoujade, Erik Beranek) (Z-Library)MAGDALENA MASTROMARINONo ratings yet

- Natural and Manufactured Post-Ex EssayDocument4 pagesNatural and Manufactured Post-Ex Essayapi-681078879No ratings yet

- NostalgiaDocument4 pagesNostalgiaNadezda CacinovicNo ratings yet

- Interview With T.J. Clark PDFDocument8 pagesInterview With T.J. Clark PDFmarcusdannyNo ratings yet

- The Imagination Muscle: Where Good Ideas Come From (And How to Have More of Them)From EverandThe Imagination Muscle: Where Good Ideas Come From (And How to Have More of Them)No ratings yet

- CreaseDocument38 pagesCreasegaothanhxuan1987No ratings yet

- Kociatkiewicz 1999Document14 pagesKociatkiewicz 1999Київські лекціїNo ratings yet

- Bell - The Prophet of SincerityDocument18 pagesBell - The Prophet of SincerityCarlos UlloaNo ratings yet

- The Genuine Alacrity of ThingsDocument210 pagesThe Genuine Alacrity of ThingsCarmen C.E.No ratings yet

- Zen and The Art of Photography 67Document8 pagesZen and The Art of Photography 67George TanayaNo ratings yet

- Centaur Mind A Glimpse Into An Integrative Structure ofDocument19 pagesCentaur Mind A Glimpse Into An Integrative Structure ofLeon BosnjakNo ratings yet

- Husserl Natural Attitude and Its Exclusion SelectionDocument7 pagesHusserl Natural Attitude and Its Exclusion SelectionÂnderson MartinsNo ratings yet

- An Aesthetic of The UnknownDocument20 pagesAn Aesthetic of The UnknowndtndhmtNo ratings yet

- Modernism Lecture 1Document6 pagesModernism Lecture 1KamlouneNo ratings yet

- Butterfly Template - Endah ListaDocument7 pagesButterfly Template - Endah Listamaria cruzNo ratings yet

- Zahurska - From Narcissism To Autism: A Digimodernist Version of Post-PostmodernDocument8 pagesZahurska - From Narcissism To Autism: A Digimodernist Version of Post-PostmodernNataliia ZahurskaNo ratings yet

- Reading Bruno Latour in Bahia.: Anthropology?. London: Berghahn BooksDocument20 pagesReading Bruno Latour in Bahia.: Anthropology?. London: Berghahn BooksClaudia FonsecaNo ratings yet

- AutismDocument7 pagesAutismNataliia ZahurskaNo ratings yet

- Writing and Shaping Creative NonfictionDocument40 pagesWriting and Shaping Creative NonfictionJoel Igno TadeoNo ratings yet

- ACV TatianaLosik10turmaDocument14 pagesACV TatianaLosik10turmaTânia LosikNo ratings yet

- Metapsychology of the Creative Process: Continuous Novelty as the Ground of Creative AdvanceFrom EverandMetapsychology of the Creative Process: Continuous Novelty as the Ground of Creative AdvanceNo ratings yet

- Stoller StorytellingConstructionRealities 2018Document7 pagesStoller StorytellingConstructionRealities 2018untuk sembarang dunia mayaNo ratings yet

- Reading's Residue EditDocument12 pagesReading's Residue EditPeter SchwengerNo ratings yet

- García Agustín Eduardo - Gótico en La Obra de Louise WelshDocument383 pagesGarcía Agustín Eduardo - Gótico en La Obra de Louise WelshLuc GagNo ratings yet

- Juani Pallasmaa - The Eyes of The SkinDocument11 pagesJuani Pallasmaa - The Eyes of The SkinBotánica Aplicada CEONo ratings yet

- Deleuze Through Wittgenstein Essays in Transcendental EmpiricismDocument107 pagesDeleuze Through Wittgenstein Essays in Transcendental EmpiricismNico PernigottiNo ratings yet

- The Early Evolutionary Imagination Literature and Human Nature 1St Edition Emelie Jonsson Full ChapterDocument67 pagesThe Early Evolutionary Imagination Literature and Human Nature 1St Edition Emelie Jonsson Full Chapterjohn.staten431100% (6)

- Amor Fati Love Thyself by Becoming WhatDocument24 pagesAmor Fati Love Thyself by Becoming WhatSoleim VegaNo ratings yet

- Narrative PhotographyDocument55 pagesNarrative Photographythanhducvo2104No ratings yet

- Semiotics and Hermeneutics of The EverydayDocument319 pagesSemiotics and Hermeneutics of The EverydayTension ExtensionNo ratings yet

- Cave The Literary ArchiveDocument20 pagesCave The Literary ArchiveLuis Martínez-Falero GalindoNo ratings yet

- CJMan IndivDocument181 pagesCJMan IndivFAAMA - Coordenação SALTNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 43.251.89.56 On Mon, 08 Aug 2022 15:57:00 UTCDocument27 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 43.251.89.56 On Mon, 08 Aug 2022 15:57:00 UTCdhiman chakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Chapter SummariesDocument17 pagesChapter SummariesDivesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Uvod PDFDocument13 pagesUvod PDFbarbara5153No ratings yet

- Absurd StructureDocument3 pagesAbsurd StructureChloe SoleNo ratings yet

- Anthropology After LevinasDocument21 pagesAnthropology After LevinascambronkhalilNo ratings yet

- KishikDocument181 pagesKishiktoriqbachmidNo ratings yet

- These Trajanka KortovaDocument514 pagesThese Trajanka KortovaAndrea MorabitoNo ratings yet

- Samplenominationletter PDFDocument2 pagesSamplenominationletter PDFGul O GulzaarNo ratings yet

- 1 16 CompiledDocument38 pages1 16 CompiledAlma PadrigoNo ratings yet

- Resonance and Wonder, Stephen J. GreenblattDocument12 pagesResonance and Wonder, Stephen J. GreenblattMélNo ratings yet

- Chanting - Standard Zen PDFDocument54 pagesChanting - Standard Zen PDFAdo ParakranabahuNo ratings yet

- 05-Roshaniyya by Fakhar+ShahbazDocument11 pages05-Roshaniyya by Fakhar+ShahbazShep SmithNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal ElementsDocument17 pagesResearch Proposal ElementsKgomotso SehlapeloNo ratings yet

- What Makes Listening So DifficultDocument2 pagesWhat Makes Listening So DifficultYoo ChenchenNo ratings yet

- Celebbrite PDFDocument6 pagesCelebbrite PDFSaber KhezamiNo ratings yet

- Clinical Leadership Doc by MckinseyAug08Document32 pagesClinical Leadership Doc by MckinseyAug08Tyka Asta AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Effective Interview PDFDocument2 pagesGuidelines For Effective Interview PDFMaria VisitacionNo ratings yet

- Epistemology and PsychoanalysisDocument6 pagesEpistemology and PsychoanalysisDaniel Costa SimoesNo ratings yet

- DLL Math 5Document8 pagesDLL Math 5YolydeBelenNo ratings yet

- The Foundations: Logic and Proofs: Chapter 1, Part I: Propositional LogicDocument148 pagesThe Foundations: Logic and Proofs: Chapter 1, Part I: Propositional LogicIrfan FazailNo ratings yet

- Project Assignment Topics Ps 1Document3 pagesProject Assignment Topics Ps 1Rupesh 1312100% (1)

- Fundamentals of Cognitive Psychology 3Rd Edition Kellogg Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument31 pagesFundamentals of Cognitive Psychology 3Rd Edition Kellogg Test Bank Full Chapter PDFadelehuu9y4100% (14)

- Literary AnalysisDocument15 pagesLiterary AnalysisPakistan PerspectivesNo ratings yet

- The Magic of BelievingDocument8 pagesThe Magic of BelievingSabelo ZwaneNo ratings yet

- Dasam Granth Da Likhari Kaun - 2Document22 pagesDasam Granth Da Likhari Kaun - 2banda singhNo ratings yet

- COT Watch MaterialDocument6 pagesCOT Watch MaterialRay PatriarcaNo ratings yet

- The Self in Western and Eastern Thought ReflectionDocument5 pagesThe Self in Western and Eastern Thought ReflectionRinchel ObusanNo ratings yet

- I Want To Kill MyselfDocument5 pagesI Want To Kill MyselfDaenielle MagnayeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Shear Force and Bending MomentDocument56 pagesChapter 2 - Shear Force and Bending MomentAmeerul Azmie100% (1)

- Siobhan Judge Multimodal LearningDocument4 pagesSiobhan Judge Multimodal Learningapi-265915778No ratings yet

- Makalah Speech RecognitionDocument15 pagesMakalah Speech RecognitionWulan SimbolonNo ratings yet

- The Power of Cell VisionDocument36 pagesThe Power of Cell VisionChrist4ro100% (1)

- ACT and RFT in Relationships Helping Clients Deepen Intimacy and Maintain Healthy Commitments Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Relational Frame Theory by JoAnne Dahl PhD, Ian Stewart PhD, C (Z-lib.o (1Document298 pagesACT and RFT in Relationships Helping Clients Deepen Intimacy and Maintain Healthy Commitments Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Relational Frame Theory by JoAnne Dahl PhD, Ian Stewart PhD, C (Z-lib.o (1Víctor CaparrósNo ratings yet

Lost in Thought - Duane Hanson

Lost in Thought - Duane Hanson

Uploaded by

Yasmin WattsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lost in Thought - Duane Hanson

Lost in Thought - Duane Hanson

Uploaded by

Yasmin WattsCopyright:

Available Formats

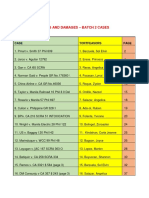

Lost in Thought: The Blurring of Life and Art in the Visual Realism and Superrealism

of Gustave Courbet, Duane Hanson, and Karl Ove Knausgaard

Author(s): Jenessa Kenway

Source: Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal , Vol. 102, No. 1 (2019), pp. 61-88

Published by: Penn State University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/soundings.102.1.0061

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Penn State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lost in Thought

soundings sgnidnuos

The Blurring of Life and Art in the

Visual Realism and Superrealism of

Gustave Courbet, Duane Hanson,

and Karl Ove Knausgaard

Jenessa KENWAY, UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA

LAS VEGAS

Abstract

The blurring of life and art is at the center of Karl Ove

Knausgaard's explorations in his memoir, My Struggle, Book 1.

Like life, Knausgaard’s book is filled with boring tasks, objects,

and events, through which he sifts attempting to locate intrin-

sic significance. Rendering in hyperreal detail aestheticizing

mundane domestic moments positions him as the literary

inheritor of the visual art movements of realism and superre-

alism, alongside artists Gustave Courbet and Duane Hanson.

Superrealist art nudges us into examination of life and peers

over the edge for a glimpse of what lies beyond the nothing-

ness of the mundane.

Keywords: visual realism, superrealism, Karl Ove Knausgaard,

Duane Hanson, Gustave Courbet, Woolf, Wittgenstein, aes-

thetics, mundane, non-being

The relentless slew of boring, repetitive chores and

activities to which we brusquely attend generally merit

Soundings,

Vol. 102, No. 1, 2019 little thought. The experience of performing such tasks

Copyright © 2019

as driving, brewing tea, washing dishes, showering,

The Pennsylvania

State University, and folding laundry quite often induces a sensation of

University Park, PA

auto-pilot in which we are simultaneously aware and

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

62

controlling what we are doing and absent, our mind wandering between

soundings sgnidnuos

present activities and thoughts of other places, people, and things. Perhaps

Virginia Woolf best describes this sensation in her memoir Moments of Being,

calling it the “cotton wool” of “non-being,”1 identifying the light packing that

muffles the mundane. “A great part of every day,” she writes, “is not lived con-

sciously” as if it is “embedded in a kind of non-descript cotton-wool. . . . One

walks, eats, sees things, deals with what has to be done; the broken vacuum

cleaner . . . washing, cooking dinner” (emphasis added) all performed and

minutes later forgotten.2 While we may not be fully aware of it, or remember

it later, a great deal of thinking, remembering, and complex mental process-

ing transpires during these banal moments of existence, blending the silvered

threads of active thought with the cotton fibers of inattentive junctures. In the

performance of mundane tasks one’s mental state is divided between the task

at hand and cerebral musings about what is to come, what happened earlier,

current strivings and failings, dinner plans, to-do lists, conversation snippets,

and so on. During these moments we occasionally step outside ourselves and

watch ourselves perform, contemplating the nature of our own thoughts.

We might wrinkle our brow or laugh involuntarily at a peculiar idea passing

through our mind. In these moments of self-reflection we inadvertently per-

form what Ludwig Wittgenstein describes as capturing “the way of thought,

which as it were flies above the world and leaves it the way it is, contemplat-

ing it from above in its flight.”3 In Wittgenstein’s description we hover above

our absorbed self, not touching, but simply observing the traffic of our mind.

While we occasionally do this ourselves, we fail to perceive these moments in

an aesthetic manner on our own. As Wittgenstein explains, “only an artist can

so represent an individual thing as to make it appear to us like a work of art.”4

It is this habitual layered self-awareness that Norwegian author Karl Ove

Knausgaard taps into in his memoir, My Struggle, Book 1. His work partici-

pates in a sustained flight of self-observation, attempting to portray moments

of self-absorption. Knausgaard puts his finger on this point of separation,

attempting to record the hum of the brain on auto-pilot, to spot, as we some-

times do, the thoughts that involuntarily pass through our minds when we

are not aware of thinking and depict the inattentive layer of consciousness

that often goes unnoticed. He attempts to bring into focus fuzzy moments of

non-being, to pin down the appearance and content of everyday thought of

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

63

average moments to gesture toward the void beyond the pale of such idling

k en way Lo st in Thou ght

thoughts. Knausgaard seeds major life events such as a marriage proposal,

a teenage crush, and the death of his father throughout the novel like pills

in a cotton-packed bottle so that they are nearly lost, overwhelmed by great

swathes of trivial details. This approach risks boring the reader and yet pro-

vides content that is perversely relatable, mimicking the typical life ratio of

periodic highlights weighed against a bulk of predominantly average days.

The mundane activities of life provide a natural stage for Knausgaard’s

work, pulling him into the artistic tradition of aestheticization of the mun-

dane. His interest in absorption also connects him with the visual arts in

which this is a commonplace theme among works that portray the mundane.

Such themes are often discussed under the label of “literary realism.” Due to

Knausgaard’s affinity with visual art and his disconnect from specific agendas

of previous works of literature in this vein, I have chosen to approach the work

of Knausgaard by focusing on the visual art lineage from realism to superre-

alism. His decision to pull from his life experience for content, combined

with his emphasis on mundane details, links him both to the movement of

realism, originating in the eighteenth century and best exemplified in the

work of Gustave Courbet, and also the superrealist sculptural works of the

1960s through 1980s, especially those of Duane Hanson. My discussion of

superrealism and Hanson demonstrates the continued trend in visual arts of

making work that turns toward life for content, a focus of Knausgaard as well.

Comparing Knausgaard with Hanson highlights visual similarities in the social

types each depict and a shared dedication, at times morbid, to documenting

the surface. Each pays attention to mundane objects and people in order to

view them aesthetically. Lastly, they both demonstrate an interest in the placid

states of mind during inattentive moments. In the work of Knausgaard and

Hanson, the “theatrical stage” of art, which creates the contextual change, is

downplayed and intentionally minimized, tamping down the elevating effect

that automatically occurs when something is made into “art.” Aligned with the

cannon of realism, yet participating like visual superrealist works in the hyper-

real amplification of mundane subject-matter, Knausgaard positions himself

as a literary inheritor of the superrealist art movement. By pausing to observe

his own thoughts, Knausgaard’s work provides a glimpse of the thought-stream

running through non-being in a way that is unavailable to us in visual works.

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

64

His efforts provide a compelling contemporary specimen of literary art giv-

soundings sgnidnuos

ing voice to mute superrealist works portraying mundane mental absorption.

Examining the work of Knausgaard, therefore, allows us to assess superreal-

ism’s function within literature.

The theme of consciousness and the commonplace is encountered in lit-

erature in the work of Marcel Proust, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Anaïs Nin,

and Emile Zola—all writers who attempted to penetrate the physiognomic

surface and access the simmering current of absorptive thought beneath.

Knausgaard’s work is inspired by these earlier works, especially Proust, and his

work can be viewed, in some ways, as continuing this literary tradition. These

earlier works, and arguably that of Knausgaard as well, engage in a project

of “aesthetic autobiography” as defined by Suzanne Nalbantian.5 However,

Knausgaard’s work is not interested in the limitations of Victorian literature

to which his modernist predecessors were responding nor is his outward real-

ity refracted through stream of consciousness. Instead, Knausgaard’s aesthetic

aligns more closely with that of “near documentary”6 that attempts to portray

moments, persons, and, as with Knausgaard, interior thoughts as well—an art

of artlessness. Therefore, the term of visual realism, rather than literary real-

ism, better assists us in making sense of the highly visual project of Knausgaard

and what it seeks to accomplish. Comparing Knausgaard to works of visual art

brings the visual strategies present in his work to the foreground. Due to the

immediacy and primacy of sight, any work of literature that strives to capture

mundane experiences is also, at some level, about the visuals that compose it.

The cognitive experience of moments of nonbeing, during which we

happen to observe our thoughts and actions, is intimately connected with

the aesthetic experience of perceiving art. Observation of mundane acts and

works of art alike entail thoughtful assimilation and digestion of minute details

and qualities. This cognitive similarity translates into the ability to perceive an

aesthetic experience within mundane occurrences which, ultimately, throws

into question the distinction between life and art. The use of the mundane

within art elevates commonplace experiences in which the change of context

results in a fundamental shift in our understanding. Devoting equal attention

to mundane acts of cleaning, cooking, and eating as to observing a work of art

blurs the distinction—a distinction that has been increasingly blurred ever

since the subject matter entered artistic depiction in the first century CE in

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

65

the form of murals depicting fruit, baskets, pitchers, platters of fish, and loaves

k en way Lo st in Thou ght

of bread.7 Food on the table moves from a position of consumption to visual

admiration. From Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting of The Peasant Wedding

in 1568 to Robert Rauschenberg’s 1955 paint-soaked, unmade Bed, artists have

pulled the material of life inexorably into art. Initially, it may seem superreal-

ism is the culminating coup de grace completing the long transformation of

life into art, and it is possible to view it in this way. As the barrier grows still

more thin, there is, however, as I shall discuss, another way of conceiving this

transformation of art into life. Interrogating the mundane within art theory is

what defines the limits of what we perceive as art. Literature can reconceive

the mundane as art within life. This blurring of life and art is at the center of

Knausgaard’s explorations. In the inversion of life and art, art becomes subor-

dinated to life.

The Disinterested Intellectual and the Turn Toward Life

The observation of figures suspended in absorption in the visual arts first

gained prominence in the eighteenth century. Moments of heightened men-

tal absorption while preforming mundane tasks are characterized by a cer-

tain negligence an, “oubli de soi or self-forgetting” as Michael Fried defines

in his seminal book, Absorption and Theatricality. In this state the individ-

ual is “oblivious to their appearance and surroundings.”8 Fried explains that

visual representations of this state of being are a common occurrence in

eighteenth-century French paintings of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, Jean-

Baptiste Greuze, Gustave Courbet, to name a few. These works consist of

images of people reading, playing cards, blowing bubbles, or lost in thought.

Visually projecting unawareness of being observed, these works satisfy Fried’s

argument that absorption is fundamentally “antitheatrical” and aim to provide

a glimpse of genuine life. Yet perversely, as Fried acknowledges, because all

works of art are created with the expectation a viewer will look at them, they are

inherently artificial. Fried expounds on this idea by turning to Wittgenstein’s

thought experiment in which Wittgenstein relates the “uncanny and won-

derful” experience of catching someone “who thinks himself unobserved

engaged in some quite simple everyday activity.”9 The figure of the thought

experiments is “walking up and down, lighting a cigarette” on a theater

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

66

stage: “Suddenly we are observing a human being from the outside in a way

soundings sgnidnuos

that ordinarily we can never observe ourselves,” Wittgenstein observes adding,

“But then we do see this every day & it makes not the slightest impression on

us! True enough, but we do not see it from that point of view.”10 Ultimately,

the attempt to catch a glimpse of the mundane act of absorption, therefore, is

paradoxical for we fail to appreciate it unless the artist pulls it out for display.

At the very moment this is done, though, we risk losing the very authenticity of

that which we sought to observe. Likewise, the moment we catch our thoughts

wandering we risk impressing active thought upon the unconscious stream.

This makes the project of Knausgaard a nuanced act alternating between

detachment and self-awareness. Depicting mundane absorption is an inher-

ently problematic endeavor. Wittgenstein’s point of putting the everyday on

the stage is what allows us to see the everyday with a refreshed perspective and

this is what art that takes the commonplace as its subject strives to accomplish.

Early realist paintings set the precedent and tone for visual representations

mining the mundane. Later artists will continue this tradition, ultimately, far

exceeding their predecessors in the appearance of the reality achieved.

Rejecting classical subject matter such as frolicking nymphs, satyrs, and

goddesses that populated the work of academic painters so out of step with

ordinary life and the French working class, Courbet instead controversially

portrayed everyday people in mundane contexts absorbed in acts of work or

leisure. Art critic Linda Nochlin explains, “Courbet was accused of painting

objects just as one might encounter them, without any compositional linkage,

and of reducing art to the indiscriminate reproduction of the first subject to

come along.”11 Declining to use “compositional linkage” suggests that Courbet

painted the subject with no attempt to re-situate the person or object into a

more pleasing visual arrangement, which hints at the earlier idea of “near doc-

umentation.” His painting The Wheat Sifters of two female workers situated

atop a pile of grain spilling out over a tarp demonstrates his rejection of classi-

cal elegance and contrived arrangement—the general mess of their profession

further accentuated by the numerous bowls and spoons scattered about them

along with a sleeping cat and young boy snooping in the adjacent tarare.12

The absorptive state of the figures is also an example of Fried’s assertion that

Courbet’s art is antitheatrical. The viewer’s position behind the lead sifter who

is absorbed in the performance and observation of her mundane task means

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

67

that both viewer and subject are directed toward the disarray of life. While

k en way Lo st in Thou ght

the subject matter of the work is commonplace labor, as Fried notes there

is an inherently creative act embedded within the task; the particles of grain

cascading upon the white tarp invoke the painterly act of mark-making upon

a canvas, drawing a clear parallel between mundane and artistic labor.13 In

this way, Courbet affirms that the creative process of art, like life, is messy and

laborious and emphasizes the similarly absorbed state of mind shared across

manual labor, making art, and viewing art. Rather than elevating it, Courbet

situates creative labor on par with other typical forms of manual labor.

The objective, as Nochlin goes on to say, is to stress that “the ordinariness

of the artistic statement, or even its ugliness, is precisely the result of trying

to get at how things actually are in a specific time and place, rather than how

they might or should be.”14 The struggle of getting at how things are logically

leads to ordinary and, at times, unattractive material, involving the working,

resting, eating, and sleeping that comprises the bulk of human existence. The

attempt to portray visually how things are begins the work that Wittgenstein

defines as “getting at how we look at things.”

The effort in Courbet’s work to represent without interference, which

increases still more in the work of Knausgaard and Hanson that I will discuss

later, aligns with Wittgenstein’s definition of philosophy. He writes “perspicu-

ous representation is of fundamental significance for us. It earmarks the form

of account we give, the way we look at things. . . . Philosophy may in no way

interfere with the actual use of language; it can in the end only describe it”

(emphasis added).15 Describing or identifying “the way” we look at things is

a first step toward evaluating “that way” of looking and, thus, conferring sig-

nificance upon it, even if that significance is simply acknowledgment. This

brings to mind Fried’s allusion to a secular spirituality present in paintings of

absorption, what he calls a “‘positive mental, or indeed, spiritual state” that

has been referred to as “mindedness.”16 Rather than a distraction from more

important ideas (e.g., eighteenth-century thoughts of a Christian life) reading,

card playing, or just musing while working may instead be productive chan-

nels for thought that, as Fried remarks, “we have yet to fathom.”17 This concept

applied to the mundane may then reclaim it for a higher purpose.

There are numerous creative parallels between this discussion of the work

of Courbet and Knausgaard’s novel.18 Nochlin’s critical commentary about

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

68

Courbet is easily transposed to Knausgaard as we find in his work that “ordi-

soundings sgnidnuos

nariness . . . or even . . . ugliness” is also one of his central points. Knausgaard

shares in Courbet’s struggle to “get at how things are” and the need to turn

toward unappealing, banal material. Both writer and artist connect creative

labor to the drudgery of manual labor and the messiness of life. Courbet and

Knausgaard each question philosophical traditions that place art on a pedestal

and turn it into something sacred, fragile, and separate from life.

While Knausgaard’s style has more in common with the hyperrealism of

later artists, early on in his memoir he establishes himself within the canon

of realism. Knausgaard’s first portrait of the father is reminiscent of Courbet’s

Stone Breakers,19 placing the parental figure in the “vegetable plot” of the

author’s childhood home and “lunging at a boulder with a sledgehammer.”

Knausgaard further describes “the hollow” as “only a few meters deep, the

black soil he has dug up and is standing on together with the dense clump

of rowan trees growing beyond the fence behind him cause the twilight to

deepen. As he straightens up and turns to me, his face is almost completely

shrouded in darkness.”20 Face, landscape, and action are therefore grasped as

a singular whole. The lumping together of boulder-breaking and father in this

segment also brings to mind the outraged remarks of an eighteenth-century

critic, cited by Nochlin, who complained Courbet “makes his stones as import-

ant as his stone breakers.”21 Likewise, Knausgaard’s trivial “stones” share equal

importance with his principle protagonist and the landscape. Knausgaard

spends a great deal of time railing against the trivial “stones” of domesticity

and in doing so increases their importance. He expresses his frustration with

the seemingly inconsequential aspects of life and tries to find the “solitude” he

needs to satisfy his stated goal of “writing something exceptional,” but instead

finds himself overwhelmed by the “superior force” of caring and cleaning up

after his children.22 We find similar circumstances in the casual untidiness of

Courbet’s Portrait of P.-J. Proudhon of 1865,23 which depicts the distracted phi-

losopher, in rumpled clothing, sitting with books and papers and turned away

from his two daughters at play, Madame Proudhon’s absence indicated by a

basket of mending on a nearby chair. Within this scene, as in Knausgaard, we

find the disinterest of the intellectual in domesticity, yet also the performance,

albeit reluctantly, of domestic duties for Proudhon’s supervision of the two

girls is through his physical proximity alone as his mind is clearly elsewhere.

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

69

The portrait of Proudhon is similar yet pales in comparison to the hectic por-

k en way Lo st in Thou ght

trait Knausgaard provides of himself and his children absorbed in the chaos

of morning preparations for the day, sans maternal assistance. Mentally dis-

tracted like Proudhon, Knausgaard is eager to shuttle his two daughters off to

daycare to allow him to return to his intellectual pursuits:

It is a question of getting through the morning, the three hours of dia-

pers that have to be changed, clothes that have to be put on, breakfast

that has to be served, faces that have to be washed, hair that has to be

combed and pinned up, teeth that have to be brushed, squabbles that

have to be averted, rompers and boots that have to be wriggled into,

before I, with the collapsible double stroller, in one hand and nudg-

ing the two small girls forward with the other, step into the elevator,

which as often as not resounds to the noise of shoving and shouting

on its descent, and into the hall, where I ease them into the stroller,

put on their hats and mittens . . . and deliver them to the nursery ten

minutes later, whereupon I have the next five hours for writing until

the mandatory routines for the children resume (emphasis added).24

Comparatively, Courbet’s portrait of the burdens of fatherhood on the intel-

lectual is idealistic next to this exhausting itemized representation. While

Proudhon sits lost in intellectual reverie, two well-behaved daughters at play

nearby, Knausgaard is entirely occupied with grooming, dressing, feeding,

scolding and transporting two small girls and does not have the luxury of

musing. But, of course, this portrait of Knausgaard and his two daughters is

created after the fact, when they are not around, meaning the content of his

intellectual labor has been given over to thoughts of the two girls. Even during

his “five hours” of reprieve the two daughters are mentally still present, the

recollections of the chaos of caring for them hindering his ability to mentally

transition to other thoughts.

The seeming peaceful equilibrium represented between work and family

found in the portrait of Proudhon is something Knausgaard claims to long

for but cannot seem to achieve: “Time is slipping away from me, running

through my fingers like sand while I . . . do what? Clean floors, wash clothes,

make dinner, wash up, go shopping, play with the children in play areas, bring

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

70

them home, undress them, bathe them, . . . tidy up. . . . It is a struggle.”25

soundings sgnidnuos

Knausgaard’s dilemma resonates with the question embedded within the pen-

sive gaze of Proudhon as he sits on the front porch steps and is a question

Knausgaard identifies as “the question of meaning.” Why “isn’t it enough?”

he wonders.26 Why is the “meaning [his children] produce insufficient to ful-

fill a whole life”?27 To find the answer, Knausgaard like Courbet turns to the

unembellished jumble of life for answers. Submitting to the “chaos” of life,

Knausgaard embraces the reality “of three hours of diapers,” “paying bills,”

and “howling” children, along with rest of his assorted life experiences, as a

source for content. By grafting his writing onto his life, Knausgaard exhibits

the same disinterest of Courbet in art for the sake of art and instead turns

his art upon life. Unpacking the pill bottle metaphor mentioned above,

Knausgaard examines the cotton to see what it consists of, seeking to uncover

latent meaning behind the chores of life. Even if they are not meaningful in

some way in and of themselves, his approach makes us recognize that the way

we look at them, our attitude toward them, reveals something about ourselves.

It is Knausgaard’s excessive documentation of mundane details that ultimately

move him beyond realism and connects him to the hyper-realism of the super-

realist art movement.

Superrealism and Similarities Between Knausgaard and Hanson

Critics in the 1960s and 1970s originally referred to superrealism works as “new

realism” as they endeavored to account for the more visually “real” quality, far

exceeding previous works of realism.28 Grappling with the super “real” sculp-

tural works, before settling upon “hyper-realism,” critic Joseph Masheck writes

“with an ostensibly styleless and baldly descriptive art upon us, we seem uncer-

tain how to apply the term realism.”29 Figurative sculptures by Duane Hanson

made of life-cast polyester and fiber glass have polychromed figures, luminous

skin, and hair and features so convincing one almost expects to catch them

in a breath30. “Pygmalion is back in business,” critic Kim Levin commented

regarding the works, referring to the Greek myth in which a sculptor’s cre-

ation came to life.31 To Masheck, superrealist works seem “designed to frus-

trate criticism,” because “hyper-realist sculptures couldn’t care less whether

we find them bad art or not even art at all.”32 Masheck’s dilemma resonates

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

71

with the reaction of some critics to Knausgaard’s work. “It is peculiarly diffi-

k en way Lo st in Thou ght

cult to get a grip on what makes the book so compelling,” writes book critic

Hari Kunzru, “because much of it appears painfully banal. It is boring, in the

way life is boring, and somehow, almost perversely, that is a surprising thing

to see on the page.”33 But, at bottom, concludes Masheck in words that apply

to Knausgaard’s work as well, “no matter how ‘real’” superrealist works are,

they are “still art and, hence, somehow different from the reality of life.”34 This

distancing between the super real re-creation of reality and reality itself corre-

sponds with the natural cognitive distancing that occurs between individual

consciousness and the apprehension of life experience. Like realism before

it, superrealist works examine the undistorted, unembellished forms of life.

This dynamic accounts for the “more direct access to the world” accorded

superrealism by Masheck. He writes, “[i]n true realism, art is released from its

limit as a mere analogue to reality and is permitted to regain continuity with

the live concerns of mankind.”35 In the context of realism, I take “live con-

cerns” to mean the day-to-day concerns and activities of a lived existence. As

Knausgaard illuminates, discussion of higher order philosophical and political

concerns must inevitably give way to the ordinary “needs of the moment . . .

trump[ing] promises of the future.”36 He demonstrates this with a poignant

childhood memory of his inability to conserve a glass of milk till the end of

the meal, requiring copious sips to swallow the disliked sardine sandwich,

emphasizing purpose over pleasure. This resonates with the day-to-day strug-

gle of driving to work, paying bills, sitting in traffic, cooking dinner, washing

up, vacuuming, attending children’s school plays or soccer matches, the “live

concerns” of just getting through the day consuming all our time, very little

left for leisurely reflection or enjoyment. By approximating reality as closely

as possible, artists such as Hanson and Knausgaard attempt to penetrate and

peel back the cotton veil of the mundane and offer a sustained, detailed view

that is unavailable to us in any other way. Our own sporadic outsider moments

are brief intermittent flickers. Lit up and put on Wittgenstein’s “uncanny and

wonderful” stage, they allow us to confront and question the mundane cotton

of life in a way we generally reserve for peak life moments.

While there are other superrealist artists that resonate with the work

of Knausgaard, Duane Hanson’s work in particular shares a special affinity

with it.37 The two share an obsession with crafting meticulous records of

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

72

ordinary lived experience and each strives to minimize the gap separating life

soundings sgnidnuos

and art. Hanson’s work has been displayed on busy streets and in airports,

and Knausgaard features visual art moments within ordinary settings. In

experiencing their art, our vision slides disturbingly easily back and forth

between life and record. For Hanson, explains critic Kirk Varnedoe, “the

figure must seem to embody life.” “Whole ensembles of personal clothing,”

he continues, are acquired to “incorporate the model’s identities into the

final figure.”38 Using clothing worn by the actual model adds the essence of

personal choice, sweat, and fabric stretch, lending an otherwise unobtainable

authenticity. Socks slipping, trousers taut with stride, stained shirts, rumpled

blouses—each bespeak the kinetic energy of arrested motion—of life paused.

Hanson captures a cast of familiar unidealized “middle or lower-class people”

in the midst of “blue collar service jobs, small business and diner eating,”

all of them “neither grotesque nor picturesque.”39 These are ordinary people

with ordinary jobs: a construction worker at lunch, janitors, athletes, elderly

shoppers, obese tourists in clashing patterns. Their act of simply existing offers

sufficient cause for distilling their likeness.

The figures of both Knausgaard and Hanson inspire uncanny revulsion

and morbid fascination. In his novel, the image of Knausgaard’s father sitting

dead in a chair in the living room occurs several times. “He died in the chair

in the room next door, it’s still there40” remarks Knausgaard during a telephone

conversation. This correlates directly with Hanson’s sculpture Man in Chair

with Beer.41 While not identical, the figure has a compelling visual compan-

ionship with Knausgaard’s description of his alcoholic father’s final years and

moment of death. He writes, “Dad, now fat and bloated, with an enormous

gut drank nonstop. . . . he was fat as a barrel, and even though his skin was

still tanned it had a kind of matte tone, there was a matte membrane cover-

ing him, and with all the hair on his face and head and his messy clothes he

looked like some kind of wild man.”42 The swarthy, ill-kempt figure in stained

white T-shirt of Hanson fluctuates between drunken stupor and death. The

position of sitting, presumably watching television, hovers over the narrow

gap between life and death, a fact Knausgaard comments upon: “That Dad

had been here only three days ago was hard to believe. That he had the same

view three days ago, walked around the same house . . . thought his thoughts

only three days ago was hard to grasp.”43 The essence of life permeates the site

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

73

of death to such an extent that, for a time, the protagonist perceives him as

k en way Lo st in Thou ght

inhabiting both states of being.

Likewise, in Hanson’s sculpture Self-portrait with Model, one easily

deposits Knausgaard’s brooding grandmother sitting, as she had when we left

her a few hours before, at the kitchen table:44

In front of her was a cup of coffee, an ashtray and a plate full of

crumbs from the rolls she had eaten. . . . Something happened to

her, and it was not old age that had her in its grip, nor illness, it was

something else. Her detachment had nothing to do with the gentle

other-worldliness or contentedness of old people, her detachment

was . . . hard and lean.45

We identify in this description of the grandmother’s detachment the same

vacant facial expression of the Hanson sculpture. There is a sense that

Knausgaard’s grandmother and the sculpture of the woman seated at the diner

table with a liquefied fudge sundae are undergoing an involuntary separa-

tion from life. Both are figures who are habitually overlooked and in that act

stripped of purpose and cast adrift in the sea of invisible mundane individuals.

The grandmother, benumbed by the routine passage of years, the habitual

disappointments of life (such as marriage to the wrong brother and the col-

lapse of her son into alcoholism), has gradually withdrawn into herself, slip-

ping into auto-pilot mode. Her routine intonation (“life’s a pitch, as the old

woman said. She couldn’t pronounce her ‘b’s”) has become a perverse mantra

summing up her life; the pre-recorded phrase is inserted repeatedly as if to

attempt to fill a blank space of an existence perceived as increasingly point-

less.46 Like pulling the string on a wind-up doll, she utters the phrase, interior

lights flicker, but this is then followed by silence. As Knausgaard writes, “she

withdrew into herself as she had done so many times . . . she sat with her

arms crossed, staring into the distance.”47 Lost in thought, the grandmother’s

body rests, like a sculptural shell, at a table in a state of blank detachment.

Similarly, the elderly woman who sits across from the figure of Hanson in the

self-portrait absentmindedly thumbs the pages of her magazine in a state of

listless detached contemplation, her partially consumed ice cream melting

unheeded. The figure of Hanson thoughtfully regards her just as Knausgaard

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

74

observes his grandmother during kitchen table conversations. In their depic-

soundings sgnidnuos

tion of ordinary, overlooked people, both Hanson and Knausgaard identify

within the mundane a blind spot in the eye of humanity.

In addition to their use of a similar cast of figures, Hanson and Knausgaard

share in their dedication to rigorous documentation of mundane surfaces, a

fact other critics have recognized. “To satisfy only his own intense . . . desire

to be faithful to the idea of the character at hand,” writes Varnedoe, Hanson

“puts painstaking labor into whole areas of skin and hair that will never be

seen (for they will lie beneath layers of clothing).”48 Hanson “lavished a great

deal of attention” upon the surface of the skin, writes critic Robert Hobbs,

for “the skin is a record of human existence. . . . It records the life a person

has lived.”49 Discussing Hanson’s sculpture Security Guard, Hobbs comments

how the skin “is an accumulated memory of collisions, poor diet, little exer-

cise, and lack of exposure to sunlight.”50 Hanson patiently duplicates the signs

of aging, sagging jowls, dry skin, traces of old scars, and liver spots, treating

the skin like a manuscript to be copied. This act is in direct conflict with the

inclinations of a society preoccupied with removing and erasing these same

signs and responding to them with rejection and disgust. Lavishing attention

upon flawed surfaces, therefore, suggests a reverence for the storied physical

experiences encoded upon the skin. “Unlike wax figures that appear amaz-

ingly real at an intermediate distance,” continues Hobbs, “Hanson’s figures

become most real when inspected closely.”51

In the same way Hanson’s sculptures increase in reality upon close exam-

ination, Knausgaard’s exacting level of detail likewise invites close scrutiny.

Hermione Hoby writes, “throughout, innumerable quotidian tasks are ren-

dered as meticulously and exhaustively as autopsies.”52 As Hanson does with

the surface of skin, Knausgaard documents the surface of place and the mass

of thoughts that pile atop it with intense detail. Following the passing of his

alcoholic father, the house of Knausgaard’s grandmother has fallen into squa-

lor and disrepair. The task of cleaning it in preparation for the wake falls upon

Knausgaard and his brother, and he meticulously describes this process in

several passages.

Domestic labor functions like a washboard upon which Knausgaard vig-

orously scrubs his thoughts. With a “bottle of green soap and a bottle of Jif

scouring cream” he tackles the bannister’s “stair-rods” covered in “all sorts

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

75

of filth . . . disintegrated leaves, pebbles, dried-up insects, old spiderwebs . . .

k en way Lo st in Thou ght

in some places almost completely black, here and there sticky.”53 Having

recorded the condition of the railing, he then describes how he “sprayed the

Jif, wrung the cloth and scrubbed every centimeter thoroughly. Once a sec-

tion was clean and had regained something of its old, dark, golden color I

dunked another cloth in Klorin and kept scrubbing.” While engaged in the

monotonous task, stimulated by the “smell of Klorin,” his mind wanders back

to the “1970’s” and his childhood memory of the “cupboard under the kitchen

sink where the detergents were kept.”54 Little effort is required by the reader to

invoke this cupboard, as many have a personal connection in both present and

past with just such a cupboard, so we readily supply our own images alongside

Knausgaard’s. He applies detail with intention to correspond with the natural

tides of the mind:

Jif didn’t exist then. Ajax washing powder did though, in a cardboard

container, red, white and blue. . . . It was a green soap. Klorin did

too. . . . There was also a brand called OMO. And there was a packet

of washing powder with a picture of a child holding the identical

packet, and on that, of course, there was a picture of the same boy

holding the same packet, and so on, and so on. . . . I often racked my

brains over mise en abyme, which in principle of course was end-

less and also existed elsewhere, such as in the bathroom mirror by

holding a mirror behind your head so that the images of the mirrors

were projected to and fro while going farther and farther back and

becoming smaller and smaller as far as the eye could see. But what

happened behind what the eye could see? Did the images carry on

getting smaller and smaller?55

This passage addresses the texture of the moment and memory. Engaged in

the task, Knausgaard watches himself scrub and polish for a few moments. As

is natural with laborious mindless tasks, it is not long before mental auto-pilot

kicks in and his mind wanders and, dutifully, he records the thoughts that

wander in, crafting a heightened reality to capture the unedited progression of

his thoughts and making connections prompted by what is in front of him. He

flies above, as Wittgenstein suggests, capturing the ways of his thoughts. The

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

76

random remembered detail of a particular soap label surfaces for no particular

soundings sgnidnuos

reason articulating the inexplicably capricious nature of memory. Out of the

repetition of scrubbing and the smell of soap, within a dim recollection of a

cleaning label, he lands upon the complexity of mise en abyme (a technique

in which an image contains a smaller copy of itself recurring in a seemingly

infinite sequence). In so doing he creates his own instance of mise en abyme

by nesting memories of cleaning powders within the present act of cleaning.

Performing housework tasks—which have a tendency to feel never-ending—

he contemplates the puzzle of infinite images. Here, and in many other pas-

sages, the mundane platform is central to developing the ensuing aesthetic

intrigue. The task complete, he pauses to admire “the gleam” returning to

the “varnish . . . although there was still a scattering of dark dirt stains.”56 Like

the skin of Hanson’s figures, Knaussgaard meticulously records the blemishes

in the skin of reality. Not only are imperfections noteworthy, but the banal

beauty of the everyday is also of immense interest to Knausgaard.

Knausgaard not only makes a point of aestheticizing mundane moments

and actions, he, on occasion, directly articulates his intentions to locate an

aesthetic experience within the mundane. Noticing a construction crane near

his grandmother’s house, for instance, he remarks on the beauty of this com-

monplace piece of building equipment: “There were few things I found more

beautiful than cranes, the skeletal nature of their construction, the steel wires

running along the top and bottom . . . the way heavy objects dangled when

being slowly transported through the air, the sky that formed a backdrop to

this mechanical provisorium.”57 He perceives silhouetted “objects dangl[ing]”

against the “backdrop” of the sky as a spontaneous landscape painting. He

describes the crane with the attentive reverence of a work of sculpture.

Presenting readymade objects as works of art is a well-established practice

within the art world—the critical difference here is this readymade has not

been transformed through recontextualization. Placed upon the pedestal

within the museum the mundane object is forcibly pulled up to be recon-

ceived as art. Skipping this step entirely, Knausgaard receives the crane as art,

no contextual alteration required. All that is required is the ability to perceive

an aesthetic quality distinct from its functionality.

Hanson shares in this sentiment of perceiving in life readymade art.

His sculptures, presented without pedestal, are placed on equal footing with

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

77

visitors, which instantly diminishes the separation between art and viewer.

k en way Lo st in Thou ght

Frequently, Hanson’s works have been presented outside the bounds of

museum walls in airports, cafeterias, and shopping districts, making the only

difference between viewer and sculpture the presence of a spiritus animus

within the former. Viewers gazing upon such extremely life-like works are

actively forced to question the distinction between themselves and what they

are looking at, pondering what exactly is it that makes one of them art?

Both artists also apply the same level of observation given to place and

objects to food. Knausgaard cooks and eats with the comportment of a painter.

Cooking dinner, he observes the food colors (“pink, light-green, white, dark-

green, golden-brown”) of a meal of salmon, green beans, and potatoes.58 On

another occasion, he makes a meal and proclaims it “a little sculpture . . . it’s

called Beer and Rissole in the Garden.” Drolly translating his impromptu title

into French, “Or des boulettes et da la bierre dans le jardin,”59 he links his

meal with the long history of French paintings of la nature morte depicting

arrangements of food and meals as art. Knausgaard’s “little sculpture” probes

the difference between art and life. Before brush was ever put to canvas, the

images portrayed in still life paintings were actual food on the table, mundane

objects deemed worthy of capturing for posterity. It has now become common-

place to attend the mundane fare of our meal tables with aesthetic apprecia-

tion with thousands snapping photos of their comestible creations and posting

them online. Does “beer and rissole” become art the moment we conceive of

it as such? Like Knausgaard, the diner tables of Hanson are populated with

Ketchup bottles, coffee cups, half-eaten sundaes, chips, and Coca Cola—

all objects which, if lifted away from the sculpture, would quickly resume

regular meal functions. The barrier separating life and art, that Hanson and

Knausgaard expose, is thin and transient.

Not only does Knausgaard contemplate food on the table, but those gath-

ering around it also become part of the composition. Inane details of cooking

and sitting down at the table with his brother Yngve and family are recounted

moment by moment:

The coffee pot light was on. The extractor hood hummed, the eggs

bubbled and spat . . . Radio blared out the traffic news jingle . . . Kari

Anne [Ygnve’s wife] shuttled back and forth between the table and

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

78

cupboards, setting the table. . . . Ygnve slipped the spatula under the

soundings sgnidnuos

eggs and transferred them, one by one, onto a broad dish, put it on

the table, beside the bread basket, fetched the pot of coffee, and filled

three cups. . . . I generally drank tea at breakfast and had since I was

fourteen, but I didn’t have the heart to point this out.60

The mundane fanfare of table setting and serving food to a guest who is

also a family member, captures the loosely formal, semi-awkward vibrations

of Knausgaard’s family breakfast. The outwardly solicitous response of accept-

ing the coffee as well as Knausgaard’s privately critical and semi-ungrateful

thoughts renders an ordinary breakfast experience filtered through his interior

perception. He draws out the experience still further including “scour[ing]

the table for salt, but there was none to be found,” followed by the mundane

dialogue requesting “Any salt?” responded to with a clipped “here” by Ygnve’s

wife.61 No detail is deemed too small to include.

It is precisely the inconsequential details of universally familiar exchanges,

such as asking for salt, discussion of sports, and his niece Ylva’s request to sit

by her uncle, that make this breakfast at once recognizable yet specific to

the individuals involved. His description of eggs reveals and observes another

superrealist quality. He writes:

Flipping open the little plastic cap watching the tiny grains sink into

the yellow yolk, barely puncturing the surface, as the butter melted

and seeped into the bread. . . . The fried egg-white was crispy under-

neath, large brownish-black pieces crunched between palate and

tongue as I chewed. . . . I bit into the yolk and it ran, yellow and

lukewarm, into my mouth.62

Knausgaard uses the buildup of insignificant details as a platform to indulge

in an equally detailed still-life of consuming fried eggs. Reference to palate,

tongue and mouth establishes overt self-observation of the mundane act of

eating, bringing to the forefront the fleeting sensory pleasures of eating that

are usually forgotten in the space of the same moment in which they achieve

notice. Observed in rich surface detail, the level of detail surpassing in super-

realist fashion the typical level of observation bestowed upon cooked yellow

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

79

orbs and toast, this plate of eggs becomes acutely real. As we pause to look at

k en way Lo st in Thou ght

Knausgaard’s breakfast table and eggs, we see the toast and eggs of countless

yestermorns. The result is a tableaux vivant of a specific yet generic breakfast

we can see, hear, and taste. The heightened experience of this breakfast from

food to family members applies the superrealist detail of a Hanson sculpture

but also does what a sculpture never could. It provides the hyper-real con-

sciousness behind the scene as Knausgaard attempts to record the myriad of

details he notices and the thoughts traveling through his mind, resulting in a

nearly too real meal. Deprived of the mist of typical inattention afforded the

mundane, and being confronted with the thoughts and details we all have but

cannot possibly take note of every time, makes the breakfast almost strange

and foreign for the reader.

It is during solitary nonmoments of thinking that the concerns of

Knausgaard and Hanson are most alike. For instance, during a mundane

morning in his office, Knausgaard happens to glance at the floor and for

seemingly no particular reason proceeds to describe it: “It was parquet and

relatively new, the reddish-brown tone at odds with the flat’s otherwise fin-

de-siècle style. I noticed that the knots and grain, perhaps two meters from

the chair where I was sitting formed an image of Christ wearing a crown of

thorns.”63 Observations such as this offer an example of the unfocused think-

ing, of oubli de soi (self-forgetting). Procrastinating, daydreaming, spacing-out,

like a cat we reflexively knit our mental claws upon the fabric of our surround-

ings. Knausgaard records the idling purr of the mind. In these moments of

thinking about nothing we absently pluck upon the thread of our life running

from past to present.

Moments lost in thought are also a central characteristic of the figures of

Hanson. He continues the theme of absorption and wandering internal reverie

that marked the work of Courbet and other French realist painters. Portraying

ordinary people engaged in ordinary activities and tasks, Hanson avoids the

more fleeting states of laughter, smiling, and affectionate interpersonal com-

munication, viewing them according to Varnedoe as “secondary, temporary

adjuncts to the more fundamental human conditions of passive self-enclosure

and isolation.”64 “As opposed to extraordinary revelation,” Varnedoe continues,

Hanson “wants to depict states of indeterminate duration, when the ephem-

eral or eccentric fades in the face of the habitual, and the characteristic truths

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

80

stand more clearly exposed.”65 Like particles settling in a glass of water, the

soundings sgnidnuos

undiluted essence of the individual reveals itself in the unagitated state of

neutral calm.

Fried classifies works like those of Hanson as literalist due to the theatrical

quality that incorporates the beholder into the work. This would seem to pre-

clude Hanson from being considered absorptive.66 The beholder is included

by being placed on equal footing and sharing physical space and proportion-

ate size with the work, yet Hanson’s sculptures also convey the attitude of oubli

de soi Fried defines, which ignores the beholder. This creates an enclosed

cerebral space within the work that is oblivious to the beholder’s presence. Just

as we find in paintings by Courbet or Chardin, Hanson’s figures stare off, or

down at the floor, or forward with blank expression, with the air of mental pre-

occupation that comes with thoughts that are engaged elsewhere. I argue that

the absorbed state of the figures makes Hanson’s work antitheatrical and thus

better aligned with Fried’s discussions of absorption in eighteenth-century

paintings rather than Fried’s literalist argument in “Art and Objecthood.”67

There is no denying Hanson’s work also participates in the discussion of

objecthood and the “condition of non-art,”68 insisting on being what it is,

which is something it shares in common with Knausgaard whose work like-

wise asserts a condition of non-art. However, the absorbed facial expressions

of Hanson’s figures resist definitive placement within the category of purely

literal art. Hanson’s sculptures perform the role of the young man smoking

in Wittgenstein’s thought experiment and the eighteenth-century paintings

ignoring their viewer, both of which inadvertently step into the theater of the

ordinary. The only thing separating the viewer from Hanson’s sculptures is the

translucent membrane of distracted thought.

Although Hanson and Knausgaard share many qualities, however,

they are not identical. Encountering the bulk of life’s mundane tasks and

moments we quite often find ourselves engaged in solitary thought staring

blankly into the recesses of our own mind. Highpoints of ecstasy, pleasure,

and happiness are the exception, not the norm. The attempt to pin down the

essence of existence falls upon the inattentive wool-carding of idling minds.

Eating lunch, scanning the horizon, reading, waiting with luggage, the fig-

ures of Hanson are locked in the contemplative indeterminacy of mundane

moments. Inscrutable, the precise thoughts of Hanson’s figures are forever

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

81

denied us. Knausgaard begins to fill this superrealist gap, gathering the wool of

k en way Lo st in Thou ght

his thoughts and attempting to locate a thread of continuity running through

the fabric of thought.

Consider again Knausgaard’s contemplation of the seemingly random

face-knot in the floor. In the act of staring at it, Knausgaard suddenly makes

a connection recalling a distant memory of discovering a face shaped in the

foamy sea of a news broadcast he watched as a child: “I suddenly remembered

something . . . deep in my childhood, a similar image on the water in a news

item about a missing fishing vessel . . . the remarkable thing was not that the

face should be visible here [in the floor’s surface], nor that I had once seen a

face in the sea in the mid 1970’s, the remarkable thing was that I had forgot-

ten it and now remembered.”69 During a moment of non-being, two dispa-

rate details, spread across time, are suddenly drawn together and pulled tight

revealing a glimpse of the whole of being woven over the course of a life. The

face in the floor links with the face in the sea revealing a cord of continuity

in which the present draws upon the past to depict the curious interconnect-

edness of memories and the quirky functionality of the mind. The “minded-

ness” of absorption relies on the slow churn of the unconscious above which

active thought hovers, in stand-by mode, ready to pluck relevant flotsam that

surfaces. During these moments of unconscious thought the unfettered brain

interlaces past and present, playing with loose memory strands until the per-

ceptive individual gliding over the top snaps them up upon resuming con-

scious control.

Restoration of the Mundane

Recording mundane actions of an idling brain serves to conjoin the two

halves—physical and intangible—of the mundane, accounting for and aes-

theticizing mundanity in its entirety. From one perspective this can be seen

as the totalizing exploitation of life for artistic purposes. There is another per-

spective, however, from which superrealism can be viewed as an attempt to

restore the inherent significance of people and objects appropriated by art.

In her 1964 article, “Against Interpretation,” Susan Sontag complains of the

refusal of critics to leave works alone, citing the dangers of interpretation: “By

reducing the work of art to the content and then interpreting that, one tames

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

82

the work of art. Interpretations makes the work manageable, comfortable.”70

soundings sgnidnuos

Once boiled down through interpretation, even the most controversial art can

be rendered quite approachable, provided with handles for gripping it so to

speak. Knausgaard shares Sontag’s concern over the over-intellectualizing and

resultant taming of art. He laments, “the situation we have arrived at now

whereby the props of art no longer have any significance, [and] all the empha-

sis is placed on what the art expresses, in other words, not what it is but what

it thinks. . . . Everything has become intellect, even our bodies, they aren’t

bodies anymore, but ideas of bodies.”71 He decries the conceptual Saran Wrap

that neatly packages and labels the parts of life.

Sontag’s suggestion to leave art alone seems impossible to implement as

looking at art objects is naturally followed by acts of thinking, comparison,

and interpretation. Sontag is not suggesting a halt to artistic contemplation,

however, but rather an end to intellectually buffering art. Rather than dull-

ing down the edge of art with protective interpretive coating, the solution,

both Knausgaard and Sontag find, is to sharpen the edge still further with

hyper realistic art that is so close to life that we must turn toward life to make

sense of it. Sontag corroborates this notion stating, “the aim of all commen-

tary on art now should be to make works of art—and, by analogy, our own

experience—more, rather than less, real to us. The function of criticism should

be to show how it is what it is, even that it is what it is, rather than to show what

it means” (emphasis added).72

Providing art that fulfills Sontag’s demands, Knausgaard’s work strives

to transcend intellectualizing and simply be “what it is.” His work embodies

what Fried explains is literalist art’s preoccupation with “objecthood,”73 in

which objects resist art status and insist upon their preexisting object iden-

tity, forcing every attempt to approach them critically into an endless con-

ceptual loop. Knausgaard insists that the “situation we have arrived at” is

one “whereby the props of art no longer have any meaning, all emphasis is

placed on what the art expresses . . . not what it is but what it thinks, what

ideas it carries.”74 He takes the “unmade bed” of art he complains of and

wheels it out of the museum. Regardless of the lofty ideals we may bring to

bear, explains French novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet, “gestures and objects

will be ‘there’ before being ‘something’. . . and they will still be there after-

ward, hard, unalterable, externally present, mocking their own meaning.”75

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

83

Significations we pin upon gestures and objects are tried on like a coat and

k en way Lo st in Thou ght

just as easily shrugged off. The action of scrubbing a bannister or sitting at

a diner table are already thick with unquantified substance, which is why

we intuitively respond and have the urge to explain the meaning of the

seemingly meaningless, as if, perhaps, some hidden cosmic explanation lies

within.

As the work of Courbet and Hanson show, documenting “ordinariness,”

even “ugliness,” is the point, the means to get at how things are. As Nochlin

notes, “it is exactly this sort of accuracy of ‘meaningless’ detail that is essen-

tial to realism for this is what nails its productions down so firmly to a specific

time and a specific place and anchors realist works in a concrete rather than

an ideal or a poetic reality.”76 Realism supposes intrinsic significance, an

intrinsic beauty, within ordinariness. Distillation of apparent dross reveals

surprising intrinsic substance. For lying just beyond the periphery of the

most ordinary postures of life lies the inverse—death. The “cotton wool” of

nonbeing is the outer rim before crossing over into true nothingness. “The

most acute records of life,” remarks Varnedoe, “are often intimately con-

nected with the threat of death.”77 Drinking coffee in his office, looking out

the window, Knausgaard muses, “I saw life; I thought about death.”78 Like

the sepulchral effigies lying in cemeteries capturing the living image of a

deceased, the work of Hanson and Knausgaard perform the role of vivid

memento mori.

The superrealism of Knausgaard and Hanson redirects our attention

through art toward life, urging close examination of the people and things

around us, and ourselves. In doing so, these works recall the realism of

Courbet and the dangers of art straying too far from life, but also (as do all

superrealism works) expand beyond it, breaking boundaries and raising the

level of realism to still greater heights. We move from the absorbed super-

realist figures of Hanson and pass through to a second stage in the writings

of Knausgaard—observation of the way of thoughts within the mind. The

musings of the mundane idling brain attached to chores and reverie com-

pletes the circle of superrealism, supplying the final link and expanding the

circumference still farther. The knife-edge of superrealism forces us to actively

look for the barrier separating life and art, which ultimately causes us to look

longer and harder at the composition of each. As Wittgenstein asserts, the

This content downloaded from

86.20.68.110 on Thu, 20 Apr 2023 10:26:02 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

84

disinterested observation of the artist leaves these actions and thoughts the

soundings sgnidnuos

way they are, without revising or correcting them; if there are any changes

to be made it is up to us to make decisions and act on them within our own

lived experience. The application of mindedness to the mundane within

Knausgaard demonstrates fruitful results. Tapping into the innate layer of

meditative self-awareness, Knausgaard’s work packs the doldrums of life with

rich content that competes with so-called main events. Superrealism in liter-

ature thus offers new prospects with no set limitations—its success is entirely