Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Climate Change and Ethics

Climate Change and Ethics

Uploaded by

Ivica KelamCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- 100 Great Sales IdeasDocument8 pages100 Great Sales IdeasKommawar Shiva kumarNo ratings yet

- Bequest Giving - Revisiting Donor Motivation With Dimensional Qualitative ResearchDocument18 pagesBequest Giving - Revisiting Donor Motivation With Dimensional Qualitative ResearchIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- The New Persian Kitchen by Louisa Shafia - RecipesDocument16 pagesThe New Persian Kitchen by Louisa Shafia - RecipesThe Recipe Club83% (12)

- The Use of BondsDocument8 pagesThe Use of BondsDarius Rashaud86% (7)

- Global JusticeDocument40 pagesGlobal JusticeAbraham Paulsen BilbaoNo ratings yet

- Special Section Safeguarding Fairness inDocument17 pagesSpecial Section Safeguarding Fairness inAbbass ButtNo ratings yet

- 180014e !! PDFDocument2 pages180014e !! PDFAntoneoNo ratings yet

- Global Justice and Climate Change: How Should Responsibilities Be Distributed?Document40 pagesGlobal Justice and Climate Change: How Should Responsibilities Be Distributed?faignacioNo ratings yet

- Clla Article p266 - 266Document16 pagesClla Article p266 - 266jb6whg5jjcNo ratings yet

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Climate JusticeDocument33 pagesStanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Climate JusticeJohnNo ratings yet

- BK Climate Change Liability 2 p1 Legal Scientific Policy 031211 enDocument64 pagesBK Climate Change Liability 2 p1 Legal Scientific Policy 031211 enAzizrahman AbubakarNo ratings yet

- 2021 - Lenzi - Virtue Ethics and Aggregation ProblemsDocument16 pages2021 - Lenzi - Virtue Ethics and Aggregation ProblemsTheologos PardalidisNo ratings yet

- Cosmopolitan Justice, Responsibility, and Global Climate ChangeDocument30 pagesCosmopolitan Justice, Responsibility, and Global Climate Changegargantua09No ratings yet

- Ostrom A Multi-Scale Approach To C..Document13 pagesOstrom A Multi-Scale Approach To C..dominikakw780No ratings yet

- Global Justice ApproachesDocument3 pagesGlobal Justice ApproachesDennis MariitaNo ratings yet

- A Multiscale Approach To Coping With Climatre Change Anf Other Collective Action ProblemsDocument12 pagesA Multiscale Approach To Coping With Climatre Change Anf Other Collective Action ProblemsMaria Giuliana Quezada GarciaNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument2 pagesResearchCá XinhNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Moral IssuesDocument5 pagesContemporary Moral IssuesKaushal PrabhudevNo ratings yet

- Climate Literacy Aff - Berkeley 2017Document139 pagesClimate Literacy Aff - Berkeley 2017Andrew GrazianoNo ratings yet

- Bowman On The Alleged Insufficiency of The Polluter Pays PrincipleDocument26 pagesBowman On The Alleged Insufficiency of The Polluter Pays PrincipleManvi YadavNo ratings yet

- Hartz EllDocument28 pagesHartz Ellutkarsh130896No ratings yet

- Climate Justice Meaning Challenges and Way Forward Explained PointwiseDocument6 pagesClimate Justice Meaning Challenges and Way Forward Explained Pointwisesrk99096362No ratings yet

- Environmental Politics: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationDocument21 pagesEnvironmental Politics: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationLudovic FanstenNo ratings yet

- Women, E-Waste, and Technological Solutions To Climate Change.Document13 pagesWomen, E-Waste, and Technological Solutions To Climate Change.qfttch2g9hNo ratings yet

- Climate JusticeDocument26 pagesClimate JusticeKaab RanaNo ratings yet

- Climate Change PaperDocument7 pagesClimate Change PaperGabriela Zitlalic Morales GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Focus 1 - Session 1Document30 pagesFocus 1 - Session 1trankhanhquynh1126No ratings yet

- The Ethics of Carbon Neutrality: A Critical Examination of Voluntary Carbon Offset ProvidersDocument31 pagesThe Ethics of Carbon Neutrality: A Critical Examination of Voluntary Carbon Offset ProviderslucyNo ratings yet

- Global TrendLab 2012 SustainabilityDocument32 pagesGlobal TrendLab 2012 SustainabilityMauricoNo ratings yet

- Gardiner, S.M. 2010. Ethics and Climate Change. An Introduction. WIREs, 1, 1, 54-66.Document13 pagesGardiner, S.M. 2010. Ethics and Climate Change. An Introduction. WIREs, 1, 1, 54-66.ANA TOSSIGENo ratings yet

- Co-Benefits of Addressing Climate Change Can Motivate Action Around The WorldDocument13 pagesCo-Benefits of Addressing Climate Change Can Motivate Action Around The WorldVictor OuruNo ratings yet

- Quantum Social Theory y Cambio ClimaticoDocument9 pagesQuantum Social Theory y Cambio ClimaticoIgnacio PisanoNo ratings yet

- Environmental Justice and Sustainable Development: Integrating Local Communities in Environmental ManagementDocument14 pagesEnvironmental Justice and Sustainable Development: Integrating Local Communities in Environmental ManagementAries MatibagNo ratings yet

- A Perfect Moral StormDocument33 pagesA Perfect Moral StormPaula Pinilla100% (1)

- Book - Pearman Et Al-324-374Document51 pagesBook - Pearman Et Al-324-374Nadila mudeaNo ratings yet

- Socsci 08 00024 v2Document18 pagesSocsci 08 00024 v2Abbass ButtNo ratings yet

- COP15 Field Study ReflectionDocument6 pagesCOP15 Field Study ReflectionKatie Paulson-SmithNo ratings yet

- Climate JusticeDocument10 pagesClimate JusticePriYanuj HanDiqueNo ratings yet

- Sustain 97Document41 pagesSustain 97deny_herinNo ratings yet

- Mckinnon, Catriona - Climate Justice in A Carbon BudgetDocument10 pagesMckinnon, Catriona - Climate Justice in A Carbon BudgetManuel SerranoNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics CIA-3: Submitted To M. Abraham MathewDocument4 pagesBusiness Ethics CIA-3: Submitted To M. Abraham MathewSayon DasNo ratings yet

- Climate ChangeDocument9 pagesClimate ChangeJesús Paz GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Bain, P.G. and Bongiorno, R. (2019) It's Not Too Late To Do The Right Thing MoralDocument22 pagesBain, P.G. and Bongiorno, R. (2019) It's Not Too Late To Do The Right Thing MoralRoberto LorenzoNo ratings yet

- Accepting Collective Responsibility For PDFDocument31 pagesAccepting Collective Responsibility For PDFSilvino González MoralesNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Political Theory: NPT EL IitgDocument8 pagesIntroduction To Political Theory: NPT EL Iitgyuvraj.n2021No ratings yet

- International Climate Change Negotiations Nothing More Than Sounding Brass or Tinkling CymbalsDocument55 pagesInternational Climate Change Negotiations Nothing More Than Sounding Brass or Tinkling CymbalsNatalia Torres ZunigaNo ratings yet

- 10.7 - VT - Writing Advanced 28-07-2023-09-29-57Document1 page10.7 - VT - Writing Advanced 28-07-2023-09-29-57nhatdz2403No ratings yet

- Climate JusticeDocument19 pagesClimate JusticeAli HamzaNo ratings yet

- Notes - Seminar 8 Environmental EthicsDocument8 pagesNotes - Seminar 8 Environmental Ethicsmunibaasghar13No ratings yet

- Otto Et Al., 2022Document15 pagesOtto Et Al., 2022Hugo MüllerNo ratings yet

- Principles of Climate JusticeDocument3 pagesPrinciples of Climate Justicefer gaboliNo ratings yet

- Characteristics, Potentials, and Challenges of Transdisciplinary ResearchDocument18 pagesCharacteristics, Potentials, and Challenges of Transdisciplinary ResearchDr Hussein ShararaNo ratings yet

- Too Late For Indigenous Climate JusticeDocument7 pagesToo Late For Indigenous Climate JusticeHernán Suárez HurevichNo ratings yet

- Amir TortDocument8 pagesAmir Tortma6096271No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2352250X21000373 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S2352250X21000373 MainLaiza May LampadNo ratings yet

- Can Capitalist Economic (Bell) .Document9 pagesCan Capitalist Economic (Bell) .Arago, Kathrina Julien S.No ratings yet

- Climate Justice in International Environmental Law: A New Paradigm in The Face of Crisis?Document5 pagesClimate Justice in International Environmental Law: A New Paradigm in The Face of Crisis?Juan QuintanaNo ratings yet

- Ethics, Morality, and The Psychology of Climate Justice: SciencedirectDocument7 pagesEthics, Morality, and The Psychology of Climate Justice: SciencedirectRema SafitriNo ratings yet

- Chapter Commentary: Polity Press D Must Not Be Otherwise Stored, DuplicatedDocument6 pagesChapter Commentary: Polity Press D Must Not Be Otherwise Stored, DuplicatedSam JoNo ratings yet

- Climate Change, Growth and Sustainability: The Ideological ContextDocument7 pagesClimate Change, Growth and Sustainability: The Ideological ContextTyndall Centre for Climate Change ResearchNo ratings yet

- Ostrom - Polycentric Approach For Coping With Climate Change PDFDocument38 pagesOstrom - Polycentric Approach For Coping With Climate Change PDFMichelle Midori MorimuraNo ratings yet

- Climate Change As A Business and Human Rights Issue A Proposal For A Moral TypologyDocument27 pagesClimate Change As A Business and Human Rights Issue A Proposal For A Moral TypologyNabil IqbalNo ratings yet

- Ethics in Electrical and Computer Engineering: Lecture #12Document4 pagesEthics in Electrical and Computer Engineering: Lecture #12Nethaji BKNo ratings yet

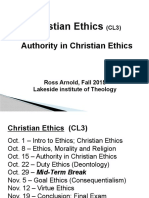

- Christian Ethics Power Point PresentationDocument2 pagesChristian Ethics Power Point PresentationIvica Kelam100% (1)

- Guidance For Transgender Inclusion in Domestic Sport 2021Document15 pagesGuidance For Transgender Inclusion in Domestic Sport 2021Ivica KelamNo ratings yet

- Lahm Advises Homosexual Players To Not Come Out - Who Would Accept It - MarcaDocument1 pageLahm Advises Homosexual Players To Not Come Out - Who Would Accept It - MarcaIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Aristotle EthicsDocument27 pagesAristotle EthicsIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- 15 10 15 CL3 Authority in Christian EthicsDocument15 pages15 10 15 CL3 Authority in Christian EthicsIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- 2021 106 European Soy Supply WNF 2201 Final 1Document30 pages2021 106 European Soy Supply WNF 2201 Final 1Ivica KelamNo ratings yet

- 15 11 05 CL3 Deontology Duty EthicsDocument20 pages15 11 05 CL3 Deontology Duty EthicsIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Personality and Social Media Addiction Among College StudentsDocument4 pagesPersonality and Social Media Addiction Among College StudentsIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- 15 10 22 CL3 Teleology Goals EthicsDocument17 pages15 10 22 CL3 Teleology Goals EthicsIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Atos Atd Benchmark enDocument14 pagesAtos Atd Benchmark enIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- 15 10 8 CL3 Ethics Morality and ReligionDocument9 pages15 10 8 CL3 Ethics Morality and ReligionIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- 15 10 1 CL3 Christian Ethics IntroductionDocument18 pages15 10 1 CL3 Christian Ethics IntroductionIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Development of School and Sport Burnout in AdolescentDocument19 pagesDevelopment of School and Sport Burnout in AdolescentIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- The Office of The Auditor General of Norway's Investigation of Norway's International Climate and Forest InitiativeDocument149 pagesThe Office of The Auditor General of Norway's Investigation of Norway's International Climate and Forest InitiativeIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Oxfam Net Zero TargetDocument42 pagesOxfam Net Zero TargetIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Pnas 2004334117Document7 pagesPnas 2004334117Ivica KelamNo ratings yet

- Comparing Burnout in Sport-SpecializingDocument7 pagesComparing Burnout in Sport-SpecializingIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Appleton & Hill (2012) JCSPDocument18 pagesAppleton & Hill (2012) JCSPIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Avoidance of Burnout in The Young Athlete: Cora Collette Breuner, MD, MPH, FAAPDocument5 pagesAvoidance of Burnout in The Young Athlete: Cora Collette Breuner, MD, MPH, FAAPIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- J Public Health 2015 Weiss 367 9Document3 pagesJ Public Health 2015 Weiss 367 9Ivica KelamNo ratings yet

- Role of Sport in International Relations: National Rebirth and RenewalDocument17 pagesRole of Sport in International Relations: National Rebirth and RenewalIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: Food ChemistryDocument26 pagesAccepted Manuscript: Food ChemistryIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- 2nd ICEBS 2019 - ScheduleDocument3 pages2nd ICEBS 2019 - ScheduleIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Genome Editing An Ethical ReviewDocument136 pagesGenome Editing An Ethical ReviewIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Parry, Jim - E-Sports Are Not SportsDocument17 pagesParry, Jim - E-Sports Are Not SportsIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- GE Trees, Cellulosic Ethanol, and The Destruction of Forest Biological DiversityDocument14 pagesGE Trees, Cellulosic Ethanol, and The Destruction of Forest Biological DiversityIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- A Greener Potemkin VillageDocument12 pagesA Greener Potemkin VillageIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Dndaf Security Views Vince Quesnel 19 March 2013Document47 pagesDndaf Security Views Vince Quesnel 19 March 2013Isaac jebaduraiNo ratings yet

- Group A (Philippines Shift To K To 12 Curriculum)Document2 pagesGroup A (Philippines Shift To K To 12 Curriculum)krisha chiu100% (1)

- AMS News in The AustralianDocument4 pagesAMS News in The AustralianandrewsaisaiNo ratings yet

- 51-Delfin v. Billones G.R. No. 146550 March 17, 2006Document7 pages51-Delfin v. Billones G.R. No. 146550 March 17, 2006Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- Daedalus and IcarusDocument8 pagesDaedalus and IcarusMuhammad AnsarNo ratings yet

- NOA Sociology 01Document39 pagesNOA Sociology 01Nazrat AnemNo ratings yet

- Gap Filling Exercise IELTS AcademicDocument4 pagesGap Filling Exercise IELTS AcademicJyothiNo ratings yet

- Crate Escape ScenarioDocument1 pageCrate Escape ScenarioBladiebla84No ratings yet

- WEEK 13 - Written Plan - Vietnam LiteratureDocument13 pagesWEEK 13 - Written Plan - Vietnam LiteratureDhavid James ObtinaNo ratings yet

- Kelompok 10 PronounsDocument19 pagesKelompok 10 PronounssariNo ratings yet

- 01 20Document488 pages01 20Steve Barrow100% (1)

- Capital Budgeting NotesDocument5 pagesCapital Budgeting NotesDipin LohiyaNo ratings yet

- Understand: Bohol BoholDocument5 pagesUnderstand: Bohol BoholRamil GofredoNo ratings yet

- Pioneer Texturizing Corp Vs NLRCDocument1 pagePioneer Texturizing Corp Vs NLRCVin LacsieNo ratings yet

- 17 Atci Overseas Corporation v. Ma Josefa Echin GR No 178551Document3 pages17 Atci Overseas Corporation v. Ma Josefa Echin GR No 178551Paula TorobaNo ratings yet

- Scholaro GPA CalculatorDocument1 pageScholaro GPA CalculatorTanvirNo ratings yet

- Intercultural Communication Globalization and Social Justice 2nd Edition Sorrells Test Bank 1Document25 pagesIntercultural Communication Globalization and Social Justice 2nd Edition Sorrells Test Bank 1erinbartlettcbrsgawejx100% (34)

- Maricalum Mining Corp. vs. FlorentinodocxDocument6 pagesMaricalum Mining Corp. vs. FlorentinodocxMichelle Marie TablizoNo ratings yet

- 5yr Prog Case Digests PDFDocument346 pages5yr Prog Case Digests PDFMary Neil GalvisoNo ratings yet

- TH 95Document81 pagesTH 95Rock LeeNo ratings yet

- Exxon Mobil Butyl Polymers GradeDocument2 pagesExxon Mobil Butyl Polymers GradeAd HesiveNo ratings yet

- Transkrip Sementara Universitas Wahid Hasyim: (Certificate of Establishment)Document3 pagesTranskrip Sementara Universitas Wahid Hasyim: (Certificate of Establishment)Lailatuz ZakiyahNo ratings yet

- Borehole and Water Pans Nakurio Lorus and Urum 002 240203 231428Document151 pagesBorehole and Water Pans Nakurio Lorus and Urum 002 240203 231428vincent mugendiNo ratings yet

- Aatma Nirbhar: BharatDocument17 pagesAatma Nirbhar: Bharatrashi agrawalNo ratings yet

- Effect of Digitalization and Impact of Employee's PerformanceDocument9 pagesEffect of Digitalization and Impact of Employee's PerformanceAMNA KHAN FITNESSSNo ratings yet

- Murder in ParadiseDocument5 pagesMurder in ParadiseJamaica BilanoNo ratings yet

- Nabard (National Bank For Agriculture and Rural Development)Document21 pagesNabard (National Bank For Agriculture and Rural Development)ds_frnship4235No ratings yet

Climate Change and Ethics

Climate Change and Ethics

Uploaded by

Ivica KelamOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Climate Change and Ethics

Climate Change and Ethics

Uploaded by

Ivica KelamCopyright:

Available Formats

REVIEW ARTICLE

PUBLISHED ONLINE: 14 OCTOBER 2012 | DOI: 10.1038/NCLIMATE1615

Climate change and ethics

Tim Hayward

What does it matter if the climate changes? This kind of question does not admit of a scientific answer. Natural science can tell

us what some of its biophysical effects are likely to be; social scientists can estimate what consequences such effects could

have for human lives and livelihoods. But how should we respond? The question is, at root, about how we think we should live—

and different people have myriad different ideas about this. The distinctive task of ethics is to bring some clarity and order to

these ideas.

C

limate change is a matter of concern because, according to Where debate has been more intense is on the question of the

various prognoses offered by scientists, its effects are likely ‘who’—who has a responsibility to shoulder the burdens. Regarding

to be detrimental to human—and not only human—life on the range of potential bearers of responsibility, which could be

this planet: “human beings are transforming Earth in ways that are individuals, corporations or states, for instance, the allocation of

devastating for other forms of life, future human beings, and many responsibilities has so far focused in practice at the level of nation-

of our human contemporaries”1. Given that premise, the central role states, and there has been international agreement to the principle

of ethics is to organize thought about what humans ought to do in of common but differentiated responsibilities among them9. It has

response to the threats they face, and to some extent are creating. generally been assumed, as Grubb noted in 1995, that the main

People engage practically in ethics whenever they make or assess question is justice of allocation of emissions as between states10. This

particular proposals about what should be done; but academics par- assumption is not without its critics11, but the relevance of focusing

ticularly focus on clarifying the structure of moral considerations on states is that they still have main political decision-making pow-

that are brought to bear on a problem, along with elucidating the ers in the world today.

assumptions being borne upon. In practice and in theory, then, eth- Most attention has focused on the criteria for differentiation of

ics reflects on the human goods that climate change can undermine, responsibilities. Because responsibilities imply costs or burdens to

and examines questions such as what actions are right or wrong be borne, and because people have a general preference to shift these

in relation to climate change, who has what duties, and how these whenever possible onto others, there is the most argument here (see

relate to others’ rights, for example, to be protected against effects Table 1). The issues involved have been brought into particular focus

of climate change. The relevant range of problems has come into in connection with debate around international climate change

focus only relatively recently, with most literature appearing during agreements. The Kyoto Protocol adopted the ‘grandfathering prin-

the past 20 years or so, but with considerable acceleration since the ciple’: the developed (Annex-I) countries were required to reduce

time of Gardiner’s seminal review in 20042, and as witnessed by two emissions by an average of 5% compared with 1990 levels. Hence

noteworthy collections of influential articles appearing in the past those already heavily polluting in 1990 could continue emitting

two years3,4. more GHGs than lower-emitting countries. In post-Kyoto negotia-

In what follows, I show first how the greater part of debate about tions, which envisage developing countries also being included in

the ethics of climate change focuses on questions about who has what the emissions reduction programme, the richer countries continue

responsibility to bear the burdens of mitigating it or adapting to it. to press for application of the principle12. Philosophers assessing the

These questions are frequently in practice inflected in the language principle’s rationale, however, have generally regarded it as a prag-

of rights, and the various connections between human rights and matic accommodation rather than a moral argument13: if it is the

climate change are examined next. If some questions concern justice only politically feasible way to get major polluters to accept emis-

in the present, others regard our responsibilities to the future, as sions reductions, it is better than forgoing agreement altogether14.

examined in the third section. The fourth main area of inquiry con- Recent attempts to tease out what more, morally, might be said for

cerns the relation between individual and collective responsibilities. it have not claimed to defeat the main ethical objections15. These

include concerns that the ‘grandfathering’ of emissions rights will

Responsibilities entrench existing inequalities by preventing those who are worse

If humankind were a unitary agent, it could pursue clear objectives off from having the same opportunities and life chances enjoyed

for reducing or capturing carbon emissions, where necessary also by affluent citizens of more heavily polluting countries16; and it

implementing measures for assisting those of the body of human- would effectively prevent less economically developed countries

ity having to adapt to consequences of climate change. But human- from tackling energy poverty, thereby locking them into a state

kind is not a unitary agent. So a prominent debate in climate ethics of underdevelopment17.

concerns who has a responsibility to do what. The ‘what’ is usually A stronger ethical argument can be made for the principle, found

discussed under two headings: mitigation and adaptation. Ethical intuitively persuasive by many, that those who have been causally

evaluation can apply both to the decisions that cause climate change responsible for overburdening the atmosphere have moral respon-

and to its effects. Some philosophers emphasize the distinction sibility for dealing with the consequences. Nevertheless, there are

between the two kinds of responsibility 5, and there are those who considerations of both justice and practicability that tell against the

focus attention primarily on mitigation6 or adaptation7; but there principle that moral responsibility should track causal responsibil-

are also reasons to think an integrated theory appropriate8. ity. One such consideration regards applying it to present or future

Politics and International Relations, School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh, 4.09 Chrystal Macmillan Building, 15a George Square,

Edinburgh EH8 9LD, UK. e-mail: thayward@staffmail.ed.ac.uk

NATURE OLOGY | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | www.nature.com/natureology 1

© 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

REVIEW ARTICLE NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE DOI: 10.1038/NCLIMATE1615

Table 1 | Differentiating common responsibilities: who should bear the costs of dealing with climate change?

Principles Differentiation criteria Pros Cons

Causal responsibility Those who have caused the It seems fair that those who cause a Those who emitted in the past may not have realized

(‘polluter pays’) build-up of CO2 in the atmosphere problem should deal with it they were doing anything wrong, and now are dead

should bear the costs anyway; so while requiring future polluters to pay

may be fair, we cannot impose costs on

past polluters

‘Beneficiary pays’ Those who have benefited from This principle maintains connection with Because it assumes that strict liability can apply

excess emissions should pay causal responsibility by allowing that retrospectively and can be inherited, present

past polluters can be deemed to have beneficiaries can complain that it is unfair on them

bequeathed liabilities to those who have

been advantaged today by past emissions

Ability to pay Those who are able to should pay This recognizes that past emissions may Disconnecting responsibility from causation can

not have yielded present benefits for a given have perverse incentives if the ecologically efficient

country and places costs on those least are effectively required to subsidize polluters

harmed by having to bear them

actions as opposed to applying it retrospectively. Retrospective of public goods such as modern medicine or better technologies

application of the principle can be challenged on the general that have also raised living standards in developing countries28. But

grounds that this is presumptively illegitimate for any principle18. Shue’s rejoinder is that whatever benefits less developed countries

More particularly, the ‘polluter pays’ principle—which is a specific have received, these have mostly been charged for, the recipients

application of causal responsibility (and sometimes misleadingly being “left with an enormous burden of debt, much of it incurred

conflated with it)—is normally not deployed as a principle of his- precisely in the effort to purchase the good things produced by

torical accountability but as a practical device for ‘internalizing’ industrialization”29. Finally, another possibility is that past emis-

the externalized environmental ‘costs’ of economic activities19. So sions may not have yielded appreciable benefits to the present gen-

understood, it is a future-orientated principle that allows rational eration at all, but here Smith’s suggestion of applying thresholds of

decision-making about the acceptability of costs in advance of ability to pay 30 seems a sensible solution.

incurring them. The imputation of obligations and costs retrospec- In fact, one further principle frequently invoked in the climate

tively, which is anyway questionable ethically and legally, is the justice literature is that those with the ability to pay should shoulder

more so if the emitters of previous generations were ignorant of the the burden. This has pragmatic advantages over the previous two

detrimental consequences of their actions20. Furthermore, there is in that it does not require investigations of causality, or other prob-

the evident practicality that principles of liability cannot apply to lematic historical considerations. It is not usually commended as a

members of deceased generations themselves. Thus some people sole or primary principle for allocating responsibilities, however, as

argue that the causal responsibility principle can be amended so that that could support injustice or perverse incentives in cases where

if we inherit assets from our grandparents, then we should also be an ability to pay has been achieved through particular efficiency or

prepared to accept any liabilities that are attendant on those assets. ecological frugality. But it is arguably appropriate to apply where the

Simon Caney suggests that to adopt this stance is not to amend but other principles fail or cannot apply 13.

to abandon the causal responsibility principle21; it is certainly to take In any debate about distributing responsibilities, to define them

a distinct position. is also to delimit them, and the flipside of the question concerns the

This line of reasoning supports a second principle discussed in rights that people have. For instance, determining a responsibility

the climate justice literature, the ‘beneficiary pays’ principle: those not to emit more than a certain amount of carbon dioxide is, in

who enjoy benefits generated by past activities that also cause effect, to license emissions up to that amount, and it is this amount

harms to others have responsibility to shoulder a burden of alleviat- that negotiators want to know about in practice.

ing those harms22. On an approach sometimes referred to as ‘the

Brazilian proposal’ in Kyoto discussions, we should take account of Debates about rights

countries’ historical emissions because countries that have polluted The language of rights has figured prominently in climate ethics

heavily have benefited considerably therefrom in terms of increased debates. In particular, there is debate about whether climate change

wealth and more developed infrastructure23. Such countries have an can be regarded as a human rights issue, and if so how31. Two prom-

‘ecological debt’ to repay 24. inent lines of argument can be distinguished: one treats the use of

One objection, noted by Caney, is that it is unfair to hold cur- the planet’s carbon absorption capacity as a necessary good that

rent members of more affluent nations responsible for over-use of humans have a right to share; the other focuses on how harms to the

the atmospheric commons by their predecessors when there is little planet’s capacities can undermine goods that humans have a right

that they could have done to alter the energy choices of their ances- to see protected.

tors25. Others, however, point to the many advantages those living The idea that there is a human right to a certain amount of green-

in developed countries enjoy over their counterparts in developing house-gas emissions has emerged with the idea that an appropri-

countries today as a result of their nations’ historical emissions26. ate benchmark for international agreements should be an equal per

Neumayer suggests that “the current developed countries readily capita entitlement. Some have argued that there is an entitlement

accept the benefits from past emissions in the form of their high to equal or minimum emissions32, and the idea of a human right

standard of living and should therefore not be exempted from being to ‘subsistence emissions’ has been influential in debates about the

held accountable for the detrimental side-effects with which their ethics of climate change since it was first proposed by Henry Shue,

living standards were achieved”27. albeit then in the different context of ozone emissions33. Other phi-

Another objection, though, is that some of the benefits of past losophers, however, have entered sceptical considerations. As David

emissions are not confined to the emitting countries. Grubb et al., for Miller says: “People have human rights to whatever is necessary to

example, argue that past emissions made possible the development meet their basic needs as human beings, but they cannot claim a

2 NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | www.nature.com/natureclimatechange

© 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE DOI: 10.1038/NCLIMATE1615 REVIEW ARTICLE

right to whatever means they themselves prefer to use to meet those

needs”34. And as I have elsewhere argued, carbon emissions should Box 1 | Taking decisions regarding the future.

not be the object of a human right because a decent human life does

not inherently depend on them: subsistence needs can be (and for How to act against climate change cannot be decided on the

much of human history have been) met without fossil-fuelled eco- basis of ‘hard numbers’ because there are no ‘hard numbers’

nomic development35. A right to minimum emissions risks exac- when it comes to climate change. To outsiders, the cost–ben-

erbating rather than resolving the problem of excessive emissions. efit analyses (CBA) of economists may suggest otherwise.

What the rich owe to the poor should be seen not as ‘more emis- But those who understand what the studies do, also know

sions’ but as an equitable share of the benefits that they have derived two things. First, many effects of climate change simply can-

from their own excess use of the atmosphere—and, indeed, other not be adequately valued in monetary terms. Second, what

environmental services and natural resources, or ‘ecological space’36. can be valued needs to be transformed from values in the dis-

A different way in which human rights are brought into climate tant future to present values; any CBA recommendation is

ethics debates is through a focus on how the harms brought about therefore crucially dependent on the discount rate used, and

through climate change can have an adverse impact on the inter- there is no such thing as the ‘right’ discount rate, for the rate

ests that human rights are intended to protect. Derek Bell makes the chosen is in turn inextricably linked to normative value judge-

striking claim that “anthropogenic climate change violates human ments. It follows that, one way or the other, the decision-making

rights”37; Caney offers the more circumspect argument that there is towards climate change is heavily influenced by ethical choices.

a human right “not to be exposed to dangerous climate change”38. (Adapted from Neumayer 96.)

But these arguments are not always as clear as they might be on

the relationship between interests and rights: not all philosophers

agree that rights necessarily protect people’s interests39; and, even adopted51. Yet the broader point remains that some indeterminacy is

allowing that they can do so, the mere existence of an interest is not always likely to affect our thinking about the ethical claims on us of

itself sufficient for there to be a right. For the positing of a right to future generations. For instance, if we think about assigning rights

be meaningful, it must imply that there is some duty on someone to future generations, and non-individualistically, we face the dif-

to bring about the outcome specified as the content of the right40. ficulty that it is not straightforward to speak of groups having rights

Certainly, to speak of a right being violated implies a strong claim even in the present, and it is problematic to speak of rights of beings

that someone is doing something direct and pernicious. Yet the real- who do not even exist yet. Nor are such difficulties surmounted by

ity is that responsibility is more diffused and complex41. speaking instead of our duties regarding them, because the same

Nevertheless, this general issue also affects rights other than sorts of questions arise.

those relating to climate change, and still the human rights dis- Nevertheless, we are accustomed to the idea that although much

course has real traction. Recent years have seen developments about the future is uncertain, we still have to make decisions now.

towards international recognition of environmental human rights42, There is a very basic and quite simple principle articulated by pro-

with procedural rights having the firmest footing 43, but with grow- ponents of a stewardship approach to environmental ethics that

ing acknowledgement too of an underlying substantive right to we should treat the world as if held by us in trust, which means

an adequate environment44. Vanderheiden has suggested that as a leaving it in no worse condition for future generations than we find

corollary such a right includes a claim to climatic stability6; Hiskes it 52. This principle is reflected in the concept, influential since the

argues that environmental human rights can serve as the basis for Brundtland report for the World Commission on Environment and

intergenerational environmental justice45. Yet although the impetus Development 25 years ago, of sustainable development: “develop-

to use human rights discourse and instruments has a clear moti- ment that meets the needs of the present without compromising the

vation, there remain issues and uncertainties around using human ability of future generations to meet their own needs”53. This con-

rights for environmental ends or the pursuit of environmental jus- cept has met little resistance, even if questions have been voiced,

tice46. Those difficulties are all the more marked when we think such as why we should take ‘now’ as the baseline for future genera-

about climate change having future effects. tions when past generations did not always inherit as much as we

did54. But it is notoriously susceptible of different interpretations55.

Ethics for the future One key area of debate in environmental values has always focused

Although we now take a view of climate change as having effects on the question of how much of nature’s ‘capital’ can be substituted

already in the present, the future horizon remains a focus of concern by manufactured goods or other kinds of technological capacity,

(see Box 1), with questions about justice between generations and with the concept of ‘strong’ sustainability allowing much less substi-

our obligations to future generations looming large47. tution than ‘weak’ sustainability 56. Depending on the interpretation

Concerns about climate change are premised on the idea that adopted, the difference in the degree of constraint implied for eco-

there is something wrong in allowing the environment to deteri- nomic ‘business as usual’ is considerable. The weaker the constraints

orate for future generations of humans. Yet when we think more are taken to be, the more latitude there is for thinking that human-

closely what this might mean we encounter certain conundrums. kind will be able to develop its way out of environmental problems,

One much discussed in the climate change literature is the notori- through the application of innovation and technology. The latitude

ous ‘non-identity problem’ formulated by Derek Parfit48. The puzzle of this conception is consistent with economists’ assumptions about

is that if an act is wrong, this is because it harms future persons the possibility of economic growth continuing indefinitely into

or makes things worse for them than otherwise they would have the future.

been; but a person’s identity depends on the time at which he or she Much of the debate about what to do regarding climate change

is conceived, and different patterns of behaviour in this generation relates to economic considerations, but its terms are not ethically

will result in different individuals being born into future genera- neutral. Often it is framed in terms of a perceived trade-off between

tions; therefore we cannot be said to have harmed, or made worse economic benefits and environmental costs. But a case can also be

off, any future person through climate change damage by a policy made for the positive economic value of tackling climate change.

without which they would not have existed at all49. While some phi- This follows in a tradition of environmental economics that seeks

losophers attempt to find ways of dealing with this conundrum50, to attach value or price to unpriced or undervalued environmental

others doubt that it really captures what we need to be concerned ‘services’57. The influential report prepared by the British econo-

about, particularly if a less individualistic framing of the problem is mist Nicholas Stern is a noteworthy case58. Specifically regarding

NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | www.nature.com/natureclimatechange 3

© 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

REVIEW ARTICLE NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE DOI: 10.1038/NCLIMATE1615

the future dimension, Stern gave serious attention to the ethical plight of the worst off today, then the better off have to make greater

issues involved in the choice of the discount rate—that is to say, commitments to both equality and reduction of environmental

the rate at which the value of assets and welfare, as well as costs demands. From this perspective, climate ethics is seen as part and

and economic damages, including as a result of climate change, is parcel of global justice more widely construed72. Those who already

assumed to diminish over time, from the standpoint of the present. suffer most from socioeconomic disadvantage globally are generally

Stern arrived at a significantly lower rate of discount in determin- most at risk of having their suffering compounded by the effects

ing the current ‘correct’ price for carbon emissions than the influ- of climate change. The international institutional order arguably

ential position of William Nordhaus: the overall social discount rate provides structural support for this ‘radical inequality’73. These are

employed by Stern was only 1.4%, compared with Nordhaus’s 5.5% institutions in which we—individuals in affluent societies—are all

(ref. 59). This led Stern to support immediate emissions reductions implicated, according to some influential theorists of justice, nota-

consistent with a US$300 per tonne tax on carbon emissions. By bly Thomas Pogge. But Pogge has been challenged on how individu-

contrast Nordhaus supports a carbon tax of only around US$30 per als can be held responsible74. This question of connection between

tonne, rising to US$85 per tonne by 2050. This difference is almost individuals and wider associations and institutions is the final main

entirely the result of the different assumptions made when calcu- topic area.

lating the social discount rate60. The high rate implies a very low

level of concern for our descendents61. So the economics of climate Individual obligation and collective action

change cannot be separated out from the ethics: it implicitly relies Much of the literature on climate ethics addresses what govern-

on ethical judgments regarding the nature of our obligations regard- ments or policymakers should do. But what about what each of us

ing future generations62. ought to do ourselves? Some, like Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, main-

Stern himself has been criticized from both sides about the tain that the problem is primarily political, and should be dealt

assumptions he allows. Not only the more conservative mainstream with at that level75. Jamieson, by contrast, argues that although the

economists but also more radical thinkers63 have identified in nation-state is a level of social organization relevant to addressing

Stern’s work a politically loaded vision of a tamed capitalism—not climate change because it is causally efficacious, it is not the pri-

unrestrained, but not seriously challenged—persisting indefinitely mary bearer of ethical responsibilities76. He advocates inculcating

into the future. A similar vision seems to be assumed also by lib- green virtues at the individual level. Others, like Gardiner 77 and

eral political theorists who suggest that an appropriate approach to Cripps78, emphasize that the key question is how to understand the

our future-oriented obligations is to adopt John Rawls’s idea of a relationship between individual and collective responsibilities. This

‘just savings principle’64, although it is questionable what exactly we is not straightforward, because what one ought to do can some-

can be saving for the future if we are already overusing the planet’s times depend on what others do, and different individuals can have

resources and environmental capacities65. different views on what should be done, as well as different degrees

The nature and shape of the ethical problem facing us becomes of commitment to actually doing it. Moreover, to address a prob-

quite different if, instead of anticipating a context of gradual envi- lem like climate change requires collective action; how is this to be

ronmental deterioration and incremental hardships as a likely achieved when individuals and groups are motivated by conflict-

result, we expect sudden and catastrophic changes66. With the pros- ing interests? Furthermore, even if an individual wants to do the

pect of runaway climate change precipitated by passing various right thing, how may their ethical obligations be affected by fail-

‘tipping points’ of abrupt change, questions arise, in particular, of ure of others to comply with theirs? This is the classic kind of col-

whether and when a precautionary approach ought to be adopted lective action problem, which has a particular salience in climate

by policy-makers. The ‘precautionary principle’ has neither a com- debates. If some people fail to do their bit, can others be reasonably

monly accepted definition nor a set of criteria to guide its imple- expected to pick up a share of the load that has been left by the

mentation67, but attempts to elicit a core idea for it have been made defaulters? To expect the morally conscientious to take up the slack

in debates about precaution in relation to climate change68. The could not only be unfairly demanding on them, it could create a

general idea is that if there is a potential for harm from an activity, perverse incentive for others to do even less79. Hence it could be

and uncertainty about the magnitude of impacts or causality, then counterproductive, or even wrong, for one to do what one believes

anticipatory action should be taken to avoid the harm. But the pre- we all ought to do. As Cripps observes, it remains a major philo-

cautionary principle admits of stronger and weaker interpretations, sophical challenge to outline individual climate duties, or to devise

and if a strong interpretation is too demanding in most policy areas, suitable rules to apply in all circumstances.

Catriona McKinnon argues, it could nevertheless be defensible with One can therefore appreciate why Jamieson believes we need

respect to climate change: if the consequences of failing to take to inculcate a new, greener, ethos. I have argued something simi-

precautionary action could be such extreme scarcity of resources lar in relation to the idea of ‘ecological citizenship’, where an ethos

as to render the pursuit of justice itself impossible, then we cannot of resourceful restraint is contrasted with the expansionist ideals

choose not to be precautionary 69. The question then is what kinds of immanent in liberal political visions80. A focus on the virtues—as

precaution are at issue. a complement to ethics of duty, rights or utility, and proposals such

The argument that climate change might undermine the very as carbon allowances81, or allowances even against a wider range of

circumstances that make justice possible relates to the literature on ecological services82—would seem to be a necessary factor in think-

environmental security 70. The range of views on the implications of ing about what individuals should do83. It is possible to generate a

environmental insecurities for ethical life is extremely wide, but one vision of living a life that is rich in ends and simple in means84, where

general insight to have emerged is that, whatever the future may the focus is on being rather than having 85, where one treads more

hold, the insecurities that already afflict people today are amplified lightly on the planet and shows kindness to one’s fellows, humans

by environmental changes71. For many people in many parts of the and non-humans alike. If everyone did this, the problem of climate

world, the circumstances that make justice possible have already change might be diffused entirely.

been undermined through processes of ecological marginalization Obstacles to the fulfilment of this green vision, however, are sev-

that are permitted and even encouraged by the institutions support- eral. One is that not everyone will find it attractive. Another is that

ing globalization today. even those who find it attractive are locked into more consumerist

It seems not unreasonable to suggest that a prerequisite of jus- lifestyles. Indeed, it is not only a question of what agents want or do:

tice for the future is a real commitment to justice now. The implica- there are institutional structures that maintain the incentives and

tion is that if we are not to discount the future, nor to disregard the motives for continuing, as far as possible, the current development

4 NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | www.nature.com/natureclimatechange

© 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE DOI: 10.1038/NCLIMATE1615 REVIEW ARTICLE

trajectory. And, not least, different individuals in the world today ways that the well-off can learn to live well but with less pressure

find themselves in some vastly different situations: for some, it is on the ecological services that support our hitherto commodious

not a case of reining in their demands on the planet, but achiev- climate, while at the same time ensuring that the poorer are not pre-

ing an adequate foothold at all. A meaningful green vision would cluded from decent life chances.

have to be one that included engagement with the structures of

global inequality 86. Received 14 February 2012; accepted 7 June 2012; published

Climate change presents collective action problems, then, not 14 October 2012

only for individuals, but also for the collectivities that are nation

states. Moreover, there are other kinds of collectivities—notably

References

those of transnational enterprise and finance—that are not under 1. Jamieson, D. When utilitarians should be virtue ethicists. Utilitas

the control of states. Given the vital difference it makes to a person’s 19, 160–183 (2007).

life whether they command some capital, or are employed by capi- 2. Gardiner, S. Ethics and global climate change. Ethics 114, 555–600 (2004).

tal, or are entirely marginalized by the global flows of capital, one 3. Arnold, D. G. (ed.) The Ethics of Global Climate Change (Cambridge Univ.

would expect a relevant ethics today to attend also to the relation- Press, 2011).

4. Gardiner, S., Caney, S., Jamieson, D. & Shue, H. (eds) Climate Ethics: Essential

ships between these classes of individuals as classes.

Readings (Oxford Univ. Press, 2010).

5. Caney, S. in The Ethics of Global Climate Change (ed. Arnold, D. G.) 77–103

Conclusion (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2011).

Ethics encompasses evaluative thought that extends from noble 6. Vanderheiden, S. Atmospheric Justice (Oxford Univ. Press, 2008).

visions and high ideals to the more immediate and constrained 7. Paavola, J. & Adger, N. Fair adaptation to climate change. Ecol. Econ.

assessment of options that face people in the here and now. There 56, 594–609 (2006).

8. Vanderheiden, S. Globalizing responsibility for climate change. Ethics Int. Aff.

are those who advocate forsaking ideal theory altogether in favour

25, 65–84 (2011).

of more pragmatic policymaking and ‘realistic’ politics87; but 9. Stone, C. D. Common but differentiated responsibilities in international law.

this risks neglecting how real people—and, indeed, history—are Am. J. Int. Law 98, 276–301 (2004).

moved by ideals. Visions of a world liberated from indiscriminate 10. Grubb, M. Seeking fair weather: ethics and the international debate on climate

consumerism among the affluent and destitution among the poor change. Int. Aff. 71, 463–496 (1995).

are not at the cutting edge of research, but they can help to give 11. Harris, P. G. & Symons, J. Justice in adaptation to climate change:

cosmopolitan implications for international institutions. Environ. Polit.

it orientation88.

19, 617–636 (2010).

So it is of course important to engage with policy ideas that 12. Moss, J. et al. Energy Equity and Environmental Security (UNESCO, 2012).

are driven by prevailing economic interests, including proposals 13. Caney, S. Justice and the distribution of greenhouse gas emissions. J. Glob.

intended to mitigate climate change by developing rather than inhib- Ethics 5, 125–146 (2009).

iting economic activity. Some have a directly physical dimension: for 14. Gosseries, A. Historical emissions and free-riding. Ethical Persp.

instance, geoengineering, “the deliberate large-scale manipulation 11, 36–60 (2004).

15. Bovens, L. in The Ethics of Global Climate Change (ed. Arnold, D. G.) 124–144

of the planetary environment to counteract anthropogenic climate

(Cambridge Univ. Press, 2011).

change”89, is receiving increased attention from scientists and poli- 16. Baer, P., Athanasiou, T., Kartha, S. & Kemp-Benedict, E. in Climate Ethics:

cymakers, and it raises important ethical questions that need to be Essential Readings (eds Gardiner, S. M., Caney, S., Jamieson, D. & Shue, H.)

monitored90. Others have more indirect impacts—for instance the 215–230 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2010).

issues surrounding carbon trading 91. In such debates it is important 17. Roberts, J. T & Parks, B. C. Fuelling injustice: globalization, ecologically

to keep alive an active questioning of the ethical assumptions made unequal exchange and climate change. Globalizations 4, 193–210 (2007).

18. Hart, H. L. A. Positivism and the separation of law and morals. Harvard Law

when costings of environmental harms are conducted, or when Rev. 71, 593–629 (1958).

debating energy policy and the cost of various alternative renewable 19. Stevens, C. Interpreting the polluter pays principle in the trade and

energy sources. environment context. Cornell Int. Law J. 27, 577–590 (1994).

Security issues, too, are likely to loom larger as the effects of cli- 20. Weisbach, D. Negligence, strict liability, and responsibility for climate change.

mate change become more serious, and I would expect academic Iowa Law Rev. 97, 521–565 (2012).

collaboration between ethics and environmental security to inten- 21. Caney, S. Cosmopolitan justice, responsibility, and global climate change.

Leiden J. Int. Law 18, 1–29 (2005).

sify, particularly with regard to issues arising when circumstances of 22. Shukla, P. R. in Fairness Concerns in Climate Change (ed. Toth, F.) 145–148

justice break down in a region. Questions emerging include whether (Earthscan, 1999).

there should be a distinct category of rights for ‘environmental refu- 23. Bode, S. Equal emissions per capita over time—a proposal to combine

gees’ or for other endangered communities92. More generally, with responsibility and equity of rights for post-2012 GHG emission entitlement

the status in international law of environmental rights gradually allocation. Environ. Policy Gov. 14, 300–316 (2004).

developing, questions remain live about whether —and how—we 24. Simms, A. Ecological Debt: The Health of the Planet and the Wealth of Nations

(Pluto, 2005).

might think of protection against climate change as a human right. 25. Caney, S. Environmental degradation, reparations, and the moral significance

A question that has not been prominent in climate ethics dis- of history. J. Soc. Phil. 37, 464–482 (2006).

cussions is: what about non-humans? But as the issues here are 26. Halme, P. Carbon debt and the (in-)significance of history. Trames

somewhat unclear 93, I suspect that concern will remain limited to 11, 346–365 (2007).

considerations of other species’ role in maintaining our ecological 27. Neumayer, E. In defence of historical accountability for greenhouse gas

life-support systems. emissions. Ecol. Econ. 33, 185–192 (2000).

28. Grubb, M., Sebenius, I., Magalhaes, A. & Subak, S. in Confronting Climate

Finally, there are two overarching factors that will continue to Change: Risks, Implications, and Responses (ed. Mintzer, I. M.) 305–322

require ethical attention. Academic debates of recent years have to a (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1992).

great extent shied away from the contribution to the problem made 29. Shue, H. Global environment and international inequity. Int. Aff.

by the planet’s expanding human population, but there are signs of a 75, 531–545 (1999).

renewed attempt to grapple with it94. The other factor is the similarly 30. Smith, K. R. in Climate Change: Developing Southern Hemisphere Perspectives

inescapable fact that the underlying problem of climate change—the (eds Giambelluca, T. W. & Henderson-Sellers, A.) 425–444 (Wiley, 1996).

31. Humphreys, S. (ed.) Human Rights and Climate Change (Cambridge Univ.

cause of continued excess emissions and the competitive struggles Press, 2009).

impeding their abatement—is the development trajectory we are 32. Singer, P. One World (Yale Univ. Press, 2004).

on, globally: the “treadmill of accumulation”, John Bellamy Foster 33. Shue, H. Subsistence emissions and luxury emissions. Law Policy,

calls it 95. The most immediate and pervasive challenge is to find 15, 39–59 (1993).

NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | www.nature.com/natureclimatechange 5

© 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

REVIEW ARTICLE NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE DOI: 10.1038/NCLIMATE1615

34. Miller, D. Global justice and climate change: How should responsibilities be 67. Fitzmaurice, M. Contemporary Issues in International Environmental Law

distributed? The Tanner Lectures on Human Values (Tsinghua Univ., 2008). (Edward Elgar, 2009).

35. Hayward, T. Human rights versus emissions rights: Climate justice and the 68. Gardiner, S. M. A core precautionary principle. J. Polit. Phil. 14, 33–60 (2006).

equitable distribution of ecological space. Ethics Int. Aff. 21, 431–450 (2007). 69. McKinnon, C. Runaway climate change: A justice-based case for precautions.

36. Sachs, W., Santarius, T. & Camiller, P. Fair Future: Resource Conflicts, Security J. Soc. Phil. 40, 187–203 (2009).

and Global Justice: A Report of the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment 70. Matthew, R. A. et al. Global Environmental Change and Human Security (MIT

and Energy (Zed Books, 2007). Press, 2009).

37. Bell, D. Does anthropogenic climate change violate human rights? Crit. Rev. Int. 71. O’Brien, K. et al. Climate Change, Ethics and Human Security (Cambridge Univ.

Soc. Polit. Phil. 14, 99–124 (2011). Press, 2010).

38. Caney, S. in Climate Change, Ethics, and Human Security (eds O’Brien, K. & St 72. Roberts, J. T. & Parks, B. C. A Climate of Injustice: Global Inequality, North–

Clair, A. L.) 113–130 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2009) South Politics, and Climate Policy (MIT Press, 2007).

39. Kramer, M., Simmonds, N. & Steiner, H. A Debate over Rights: Philosophical 73. Pogge, T. World Poverty and Human Rights (Polity, 2008).

Enquiries (Oxford Univ. Press, 1998). 74. Hayward, T. On the nature of our debt to the global poor. J. Soc. Phil.

40. O’Neill, O. Bounds of Justice (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2000). 19, 1–19 (2008).

41. Attfield, R. Mediated responsibilities, global warming, and the scope of ethics. 75. Sinnott-Armstrong, W. in Perspectives on Climate Change: Science, Economics,

J. Soc. Phil. 40, 225–236 (2009). Politics, Ethics Advances in the Economics of Environmental Research Vol. 5 (eds

42. Boyd, D. R. The Environmental Rights Revolution (UBC, 2012). Sinnott-Armstrong, W. & Howarth. R. B) 285–307 (Elsevier, 2005).

43. Boyle, A. Human rights or environmental rights? A reassessment. Fordham 76. Jamieson, D. Climate change, responsibility, and justice. Sci. Eng. Ethics

Environ. Law Rev. 18, 471–511 (2007). 16, 431–445 (2010).

44. Hayward, T. Constitutional Environmental Rights (Oxford Univ. Press, 2005). 77. Gardiner, S. M. in The Ethics of Global Climate Change (ed. Arnold, D. G.)

45. Hiskes, R. P. The Human Right to a Green Future: Environmental Rights and 38–59 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2011).

Intergenerational Justice (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2009). 78. Cripps, E. Climate change, collective harm and legitimate coercion. Crit. Rev.

46. Woods, K. Human Rights and Environmental Sustainability Int. Soc. Polit. Phil. 14, 171–193 (2011).

(Edward Elgar, 2010). 79. Miller, D. in Responsibility and Distributive Justice (eds Knight, C. &

47. Beckerman, W. & Hepburn, C. Ethics of the discount rate in the Stern review Stemplowska, Z.) 230–245 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2011).

on the economics of climate change. World Econ. 8, 187–210 (2007). 80. Hayward, T. Ecological citizenship: Justice, rights and the virtue of

48. Parfit, D. Reasons and Persons (Oxford Univ. Press, 1986). resourcefulness. Environ. Polit. 15, 435–446 (2006).

49. Cripps, E. Where we are now: Climate ethics and future challenges. Clim. Law 81. Hyams, K. A just response to climate change: Personal carbon allowances and

2, 117–133 (2011). the normal-functioning approach. J. Soc. Phil. 40, 237–256 (2009).

50. Moellendorf, D. Justice and the intergenerational assignment of the costs of 82. Corbera, E., Brown, K. & Adger, N. W. The equity and legitimacy of markets for

climate change. J. Soc. Phil. 40, 204–224 (2009). ecosystem services. Dev. Change 38, 587–613 (2007).

51. Page, E. A. Climate Change, Justice and Future Generations (Edward 83. Barry, J. in Environmental Citizenship (eds Dobson, A. & Bell, D.) 21–48 (MIT

Elgar, 2006). Press, 2005).

52. Northcott, M. The Environment and Christian Ethics (Cambridge Univ. 84. Devall, B. Simple in Means, Rich in Ends (Peregrine Smith, 1988).

Press, 1996). 85. Fromm, E. To Have or To Be? (Continuum, 2005).

53. WCED. Our Common Future (Oxford Univ. Press, 1987). 86. Dobson, A. Thick cosmopolitanism. Polit. Stud. 54, 165–184 (2006).

54. Beckerman, W. in Fairness and Futurity (ed. Dobson, A.) 71–92 (Oxford Univ. 87. Posner, E. A. & Weisbach, D. Climate Change Justice (Princeton Univ.

Press, 1998). Press, 2010).

55. Redclift, M. Sustainable development (1987–2005): An oxymoron comes of age. 88. Dean Moore, K & Nelson, M. P. (eds) Moral Ground: Ethical Action for a Planet

Sustain. Dev. 13, 212–227 (2005). in Peril (Trinity Univ. Press, 2010).

56. Neumayer, E. Weak Versus Strong Sustainability: Exploring the Limits of Two 89. Shepherd, K. et al. Geoengineering the Climate: Science, Governance and

Opposing Paradigms (Edward Elgar, 2004). Uncertainty (Royal Society, 2009).

57. Costanza, R. et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural 90. Gardiner, S. M. Some early ethics of geoengineering the climate: A commentary

capital. Nature 387, 253–260 (1997). on the values of the Royal Society Report. Environ. Values 20, 163–188 (2011).

58. Stern, N. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review (Cambridge Univ. 91. Caney, S. & Hepburn, C. Emissions trading: unethical, ineffective and unjust?

Press, 2007). R. Inst. Phil. Suppl. 69, 201–234 (2011).

59. Nordhaus, W. D. A review of the Stern review on the economics of climate 92. Biermann, F. & Boas, I. Preparing for a warmer world: towards a global

change. J. Econ. Lit. 45, 686–702 (2007). governance system to protect climate refugees. Glob. Environ. Polit.

60. Broome, J. The ethics of climate change. Sci. Am. 298, 96–102 (2008). 10, 60–88 (2010).

61. Quiggin, J. Stern and his critics on discounting and climate change: An 93. Palmer, C. in The Ethics of Global Climate Change (ed. Arnold, D. G.) 272–291

editorial essay. Clim. Change, 89, 195–205 (2008). (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2011).

62. Caney, S. Climate change and the future: Time, wealth and risk. J. Soc. Phil. 94. Cafaro, P. Climate ethics and population policy. WIREs Clim. Change

40, 163–186 (2009). 3,45–61 (2012).

63. Bellamy Foster, J., Brett Clark, B. & York, R. The Ecological Rift (Monthly 95. Bellamy Foster, J. The Ecological Revolution: Making Peace with the Planet

Review Press, 2010). (Monthly Review, 2009).

64. Langhelle, O. Sustainable development and social justice: Expanding the 96. Neumayer, E. A missed opportunity: The Stern review on climate change fails

Rawlsian framework of global justice. Environ. Values 9, 295–323 (2000). to tackle the issue of non-substitutable loss of natural capital. Glob. Environ.

65. Hayward, T. International political theory and the global environment: Some Change 17, 297–391 (2007).

critical questions for liberal cosmopolitans. J. Soc. Phil.

40, 276–295 (2009).

66. Gardiner, S. M. A Perfect Moral Storm: The Ethical Tragedy of Climate Change Competing financial interests

(Oxford Univ. Press, 2011). The author declares no competing financial interests.

6 NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE | ADVANCE ONLINE PUBLICATION | www.nature.com/natureclimatechange

© 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved

You might also like

- 100 Great Sales IdeasDocument8 pages100 Great Sales IdeasKommawar Shiva kumarNo ratings yet

- Bequest Giving - Revisiting Donor Motivation With Dimensional Qualitative ResearchDocument18 pagesBequest Giving - Revisiting Donor Motivation With Dimensional Qualitative ResearchIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- The New Persian Kitchen by Louisa Shafia - RecipesDocument16 pagesThe New Persian Kitchen by Louisa Shafia - RecipesThe Recipe Club83% (12)

- The Use of BondsDocument8 pagesThe Use of BondsDarius Rashaud86% (7)

- Global JusticeDocument40 pagesGlobal JusticeAbraham Paulsen BilbaoNo ratings yet

- Special Section Safeguarding Fairness inDocument17 pagesSpecial Section Safeguarding Fairness inAbbass ButtNo ratings yet

- 180014e !! PDFDocument2 pages180014e !! PDFAntoneoNo ratings yet

- Global Justice and Climate Change: How Should Responsibilities Be Distributed?Document40 pagesGlobal Justice and Climate Change: How Should Responsibilities Be Distributed?faignacioNo ratings yet

- Clla Article p266 - 266Document16 pagesClla Article p266 - 266jb6whg5jjcNo ratings yet

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Climate JusticeDocument33 pagesStanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Climate JusticeJohnNo ratings yet

- BK Climate Change Liability 2 p1 Legal Scientific Policy 031211 enDocument64 pagesBK Climate Change Liability 2 p1 Legal Scientific Policy 031211 enAzizrahman AbubakarNo ratings yet

- 2021 - Lenzi - Virtue Ethics and Aggregation ProblemsDocument16 pages2021 - Lenzi - Virtue Ethics and Aggregation ProblemsTheologos PardalidisNo ratings yet

- Cosmopolitan Justice, Responsibility, and Global Climate ChangeDocument30 pagesCosmopolitan Justice, Responsibility, and Global Climate Changegargantua09No ratings yet

- Ostrom A Multi-Scale Approach To C..Document13 pagesOstrom A Multi-Scale Approach To C..dominikakw780No ratings yet

- Global Justice ApproachesDocument3 pagesGlobal Justice ApproachesDennis MariitaNo ratings yet

- A Multiscale Approach To Coping With Climatre Change Anf Other Collective Action ProblemsDocument12 pagesA Multiscale Approach To Coping With Climatre Change Anf Other Collective Action ProblemsMaria Giuliana Quezada GarciaNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument2 pagesResearchCá XinhNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Moral IssuesDocument5 pagesContemporary Moral IssuesKaushal PrabhudevNo ratings yet

- Climate Literacy Aff - Berkeley 2017Document139 pagesClimate Literacy Aff - Berkeley 2017Andrew GrazianoNo ratings yet

- Bowman On The Alleged Insufficiency of The Polluter Pays PrincipleDocument26 pagesBowman On The Alleged Insufficiency of The Polluter Pays PrincipleManvi YadavNo ratings yet

- Hartz EllDocument28 pagesHartz Ellutkarsh130896No ratings yet

- Climate Justice Meaning Challenges and Way Forward Explained PointwiseDocument6 pagesClimate Justice Meaning Challenges and Way Forward Explained Pointwisesrk99096362No ratings yet

- Environmental Politics: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationDocument21 pagesEnvironmental Politics: Publication Details, Including Instructions For Authors and Subscription InformationLudovic FanstenNo ratings yet

- Women, E-Waste, and Technological Solutions To Climate Change.Document13 pagesWomen, E-Waste, and Technological Solutions To Climate Change.qfttch2g9hNo ratings yet

- Climate JusticeDocument26 pagesClimate JusticeKaab RanaNo ratings yet

- Climate Change PaperDocument7 pagesClimate Change PaperGabriela Zitlalic Morales GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Focus 1 - Session 1Document30 pagesFocus 1 - Session 1trankhanhquynh1126No ratings yet

- The Ethics of Carbon Neutrality: A Critical Examination of Voluntary Carbon Offset ProvidersDocument31 pagesThe Ethics of Carbon Neutrality: A Critical Examination of Voluntary Carbon Offset ProviderslucyNo ratings yet

- Global TrendLab 2012 SustainabilityDocument32 pagesGlobal TrendLab 2012 SustainabilityMauricoNo ratings yet

- Gardiner, S.M. 2010. Ethics and Climate Change. An Introduction. WIREs, 1, 1, 54-66.Document13 pagesGardiner, S.M. 2010. Ethics and Climate Change. An Introduction. WIREs, 1, 1, 54-66.ANA TOSSIGENo ratings yet

- Co-Benefits of Addressing Climate Change Can Motivate Action Around The WorldDocument13 pagesCo-Benefits of Addressing Climate Change Can Motivate Action Around The WorldVictor OuruNo ratings yet

- Quantum Social Theory y Cambio ClimaticoDocument9 pagesQuantum Social Theory y Cambio ClimaticoIgnacio PisanoNo ratings yet

- Environmental Justice and Sustainable Development: Integrating Local Communities in Environmental ManagementDocument14 pagesEnvironmental Justice and Sustainable Development: Integrating Local Communities in Environmental ManagementAries MatibagNo ratings yet

- A Perfect Moral StormDocument33 pagesA Perfect Moral StormPaula Pinilla100% (1)

- Book - Pearman Et Al-324-374Document51 pagesBook - Pearman Et Al-324-374Nadila mudeaNo ratings yet

- Socsci 08 00024 v2Document18 pagesSocsci 08 00024 v2Abbass ButtNo ratings yet

- COP15 Field Study ReflectionDocument6 pagesCOP15 Field Study ReflectionKatie Paulson-SmithNo ratings yet

- Climate JusticeDocument10 pagesClimate JusticePriYanuj HanDiqueNo ratings yet

- Sustain 97Document41 pagesSustain 97deny_herinNo ratings yet

- Mckinnon, Catriona - Climate Justice in A Carbon BudgetDocument10 pagesMckinnon, Catriona - Climate Justice in A Carbon BudgetManuel SerranoNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics CIA-3: Submitted To M. Abraham MathewDocument4 pagesBusiness Ethics CIA-3: Submitted To M. Abraham MathewSayon DasNo ratings yet

- Climate ChangeDocument9 pagesClimate ChangeJesús Paz GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Bain, P.G. and Bongiorno, R. (2019) It's Not Too Late To Do The Right Thing MoralDocument22 pagesBain, P.G. and Bongiorno, R. (2019) It's Not Too Late To Do The Right Thing MoralRoberto LorenzoNo ratings yet

- Accepting Collective Responsibility For PDFDocument31 pagesAccepting Collective Responsibility For PDFSilvino González MoralesNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Political Theory: NPT EL IitgDocument8 pagesIntroduction To Political Theory: NPT EL Iitgyuvraj.n2021No ratings yet

- International Climate Change Negotiations Nothing More Than Sounding Brass or Tinkling CymbalsDocument55 pagesInternational Climate Change Negotiations Nothing More Than Sounding Brass or Tinkling CymbalsNatalia Torres ZunigaNo ratings yet

- 10.7 - VT - Writing Advanced 28-07-2023-09-29-57Document1 page10.7 - VT - Writing Advanced 28-07-2023-09-29-57nhatdz2403No ratings yet

- Climate JusticeDocument19 pagesClimate JusticeAli HamzaNo ratings yet

- Notes - Seminar 8 Environmental EthicsDocument8 pagesNotes - Seminar 8 Environmental Ethicsmunibaasghar13No ratings yet

- Otto Et Al., 2022Document15 pagesOtto Et Al., 2022Hugo MüllerNo ratings yet

- Principles of Climate JusticeDocument3 pagesPrinciples of Climate Justicefer gaboliNo ratings yet

- Characteristics, Potentials, and Challenges of Transdisciplinary ResearchDocument18 pagesCharacteristics, Potentials, and Challenges of Transdisciplinary ResearchDr Hussein ShararaNo ratings yet

- Too Late For Indigenous Climate JusticeDocument7 pagesToo Late For Indigenous Climate JusticeHernán Suárez HurevichNo ratings yet

- Amir TortDocument8 pagesAmir Tortma6096271No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2352250X21000373 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S2352250X21000373 MainLaiza May LampadNo ratings yet

- Can Capitalist Economic (Bell) .Document9 pagesCan Capitalist Economic (Bell) .Arago, Kathrina Julien S.No ratings yet

- Climate Justice in International Environmental Law: A New Paradigm in The Face of Crisis?Document5 pagesClimate Justice in International Environmental Law: A New Paradigm in The Face of Crisis?Juan QuintanaNo ratings yet

- Ethics, Morality, and The Psychology of Climate Justice: SciencedirectDocument7 pagesEthics, Morality, and The Psychology of Climate Justice: SciencedirectRema SafitriNo ratings yet

- Chapter Commentary: Polity Press D Must Not Be Otherwise Stored, DuplicatedDocument6 pagesChapter Commentary: Polity Press D Must Not Be Otherwise Stored, DuplicatedSam JoNo ratings yet

- Climate Change, Growth and Sustainability: The Ideological ContextDocument7 pagesClimate Change, Growth and Sustainability: The Ideological ContextTyndall Centre for Climate Change ResearchNo ratings yet

- Ostrom - Polycentric Approach For Coping With Climate Change PDFDocument38 pagesOstrom - Polycentric Approach For Coping With Climate Change PDFMichelle Midori MorimuraNo ratings yet

- Climate Change As A Business and Human Rights Issue A Proposal For A Moral TypologyDocument27 pagesClimate Change As A Business and Human Rights Issue A Proposal For A Moral TypologyNabil IqbalNo ratings yet

- Ethics in Electrical and Computer Engineering: Lecture #12Document4 pagesEthics in Electrical and Computer Engineering: Lecture #12Nethaji BKNo ratings yet

- Christian Ethics Power Point PresentationDocument2 pagesChristian Ethics Power Point PresentationIvica Kelam100% (1)

- Guidance For Transgender Inclusion in Domestic Sport 2021Document15 pagesGuidance For Transgender Inclusion in Domestic Sport 2021Ivica KelamNo ratings yet

- Lahm Advises Homosexual Players To Not Come Out - Who Would Accept It - MarcaDocument1 pageLahm Advises Homosexual Players To Not Come Out - Who Would Accept It - MarcaIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Aristotle EthicsDocument27 pagesAristotle EthicsIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- 15 10 15 CL3 Authority in Christian EthicsDocument15 pages15 10 15 CL3 Authority in Christian EthicsIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- 2021 106 European Soy Supply WNF 2201 Final 1Document30 pages2021 106 European Soy Supply WNF 2201 Final 1Ivica KelamNo ratings yet

- 15 11 05 CL3 Deontology Duty EthicsDocument20 pages15 11 05 CL3 Deontology Duty EthicsIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Personality and Social Media Addiction Among College StudentsDocument4 pagesPersonality and Social Media Addiction Among College StudentsIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- 15 10 22 CL3 Teleology Goals EthicsDocument17 pages15 10 22 CL3 Teleology Goals EthicsIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Atos Atd Benchmark enDocument14 pagesAtos Atd Benchmark enIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- 15 10 8 CL3 Ethics Morality and ReligionDocument9 pages15 10 8 CL3 Ethics Morality and ReligionIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- 15 10 1 CL3 Christian Ethics IntroductionDocument18 pages15 10 1 CL3 Christian Ethics IntroductionIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Development of School and Sport Burnout in AdolescentDocument19 pagesDevelopment of School and Sport Burnout in AdolescentIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- The Office of The Auditor General of Norway's Investigation of Norway's International Climate and Forest InitiativeDocument149 pagesThe Office of The Auditor General of Norway's Investigation of Norway's International Climate and Forest InitiativeIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Oxfam Net Zero TargetDocument42 pagesOxfam Net Zero TargetIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Pnas 2004334117Document7 pagesPnas 2004334117Ivica KelamNo ratings yet

- Comparing Burnout in Sport-SpecializingDocument7 pagesComparing Burnout in Sport-SpecializingIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Appleton & Hill (2012) JCSPDocument18 pagesAppleton & Hill (2012) JCSPIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Avoidance of Burnout in The Young Athlete: Cora Collette Breuner, MD, MPH, FAAPDocument5 pagesAvoidance of Burnout in The Young Athlete: Cora Collette Breuner, MD, MPH, FAAPIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- J Public Health 2015 Weiss 367 9Document3 pagesJ Public Health 2015 Weiss 367 9Ivica KelamNo ratings yet

- Role of Sport in International Relations: National Rebirth and RenewalDocument17 pagesRole of Sport in International Relations: National Rebirth and RenewalIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: Food ChemistryDocument26 pagesAccepted Manuscript: Food ChemistryIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- 2nd ICEBS 2019 - ScheduleDocument3 pages2nd ICEBS 2019 - ScheduleIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Genome Editing An Ethical ReviewDocument136 pagesGenome Editing An Ethical ReviewIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Parry, Jim - E-Sports Are Not SportsDocument17 pagesParry, Jim - E-Sports Are Not SportsIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- GE Trees, Cellulosic Ethanol, and The Destruction of Forest Biological DiversityDocument14 pagesGE Trees, Cellulosic Ethanol, and The Destruction of Forest Biological DiversityIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- A Greener Potemkin VillageDocument12 pagesA Greener Potemkin VillageIvica KelamNo ratings yet

- Dndaf Security Views Vince Quesnel 19 March 2013Document47 pagesDndaf Security Views Vince Quesnel 19 March 2013Isaac jebaduraiNo ratings yet

- Group A (Philippines Shift To K To 12 Curriculum)Document2 pagesGroup A (Philippines Shift To K To 12 Curriculum)krisha chiu100% (1)

- AMS News in The AustralianDocument4 pagesAMS News in The AustralianandrewsaisaiNo ratings yet