Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Conflict Managemnt in Groups

Conflict Managemnt in Groups

Uploaded by

poarogirlOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Conflict Managemnt in Groups

Conflict Managemnt in Groups

Uploaded by

poarogirlCopyright:

Available Formats

SMALL et

10.1177/104649602237167

Zornoza GROUP

al. / CONFLICT

RESEARCHMANAGEMENT

/ October 2002 IN GROUPS

CONFLICT MANAGEMENT

IN GROUPS THAT WORK

IN TWO DIFFERENT

COMMUNICATION CONTEXTS

Face-To-Face and

Computer-Mediated Communication

ANA ZORNOZA

PILAR RIPOLL

JOSÉ M. PEIRÓ

University of Valencia, Spain

The aim of this study is to test the differences in quality and frequency of conflict management

behavior as a function of the interaction between task and communication medium, and

practice time in continuing groups that work over two different media: computer mediated

communication (CMC) and face to face communication (FTF). Conflict management

behavior is studied through observed behavior and categorized by experts. Two conflict

management behavior categories are differentiated: positive and negative conflict manage-

ment behavior. A laboratory experiment was carried out comparing 12 groups of 4 members

each, working over two communication media (6 groups FTF and 6 groups over CMC).

Groups performed three types of tasks (idea-generation tasks, intellective tasks, and mixed-

motive tasks) during weekly sessions over a 2-month period. Results obtained for the idea-

generation task show that negative conflict management is significantly higher in CMC than

in FTF. For the groups working on intellective tasks, positive conflict management is signifi-

cantly higher in FTF than in CMC. Conversely, negative conflict management is signifi-

cantly higher in CMC than in FTF. No significant differences appear in positive or in nega-

tive conflict management on the mixed-motive task. The effect of time on conflict

management behaviors in both communication media, and for intellective tasks, does not

follow the hypothesized direction. In fact, in CMC, positive conflict management decreases

AUTHORS’ NOTE: We gratefully acknowledge the help of Gloria Gonzalez in performing

the statistical analyses and the useful comments from the anonymous referees who reviewed

a previous version of this article. Correspondence concerning this article should be

addressed to Ana Zornoza, Area de Psicología Social, Facultad de Psicología, Av. Blasco

Ibáñez, 21, 46010 Valencia, Spain; e-mail: ana.zornoza@uv.es.

SMALL GROUP RESEARCH, Vol. 33 No. 5, October 2002 481-508

DOI: 10.1177/104649602237167

© 2002 Sage Publications

481

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

482 SMALL GROUP RESEARCH / October 2002

over time, and there are no significant differences in FTF. Implications of these results for

future research and practice are discussed.

A key trend in organizational life during the past decade has been

an ongoing evolution in organizational forms. These forms have

evolved away from corporate bureaucratic hierarchy and divisional

arrangements toward flatter, more streamlined management and

networked structures (DeSanctis & Poole, 1997). Teams are the

fundamental substructures of network organizations. Individuals

within teams operate as network nodes, communicating in multiple

directions with other team members. To the extent that individual

team members coordinate with members of other teams or with

individuals outside the organization, interteam relationships com-

bine to form the networked organization.

In the networked organization, coordination needs to intensify,

and reliance on technology tends to increase dramatically, particu-

larly in large firms or in firms with extensive external linkages.

Indeed, computer-based communications systems are often viewed

as making possible the shift from old to new organizational forms

(DeSanctis & Poole, 1997).

Since the 1980s, a considerable amount of research has focused

on new ways of communicating using new technologies. There

already exist numerous studies analyzing the influence of these

new media on groups’ work (Hollingshead & McGrath, 1994;

Kiesler, Siegel, & McGuire, 1984; Lea & Spears, 1992; Siegel,

Dubrowsky, Kiesler, & McGuire, 1986). Findings from

psychosocial studies suggest that the use of computers for commu-

nication changes group processes and outcomes. However, much

attention has been paid to the outcomes, whereas processes have

hardly been studied. In fact, little research has focused on conflict

and conflict management in groups whose work is mediated by new

information technologies.

Generally, there is agreement among group theorists that groups

develop in stages and conflict occurs naturally as the group strives

to reach a productive or problem-solving stage (McGrath, 1990). In

groups working together over time, conflict arises in a variety of

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

Zornoza et al. / CONFLICT MANAGEMENT IN GROUPS 483

forms and contexts, and without it, conflict development into a pro-

ductive group may be impaired (Corey & Corey, 1992).

Conflict has been defined as disagreements between people

regarding their preferences and positions due to their systemati-

cally different preference structures (McGrath, 1984).

Schmidt and Kochan (1972) pointed out that functions and out-

comes of conflict can be either positive or negative, destructive or

constructive. Some of the positive functions include arriving at

important issues, creating new ideas, releasing tension, reevaluat-

ing and clarifying goals, and so on. Negative functions may include

prolonging and escalating conflict, inflexibility, and hostility. The

goal of conflict management is to keep conflicts productive rather

than destructive (Deutsch, 1973).

Conflict resolution and conflict management represent current

differing viewpoints of the preferred outcomes of any conflict.

Conflict resolution is based on the underlying notion that conflict is

essentially negative and destructive and has the primary focus of

ending a specific conflict (Kottler, 1994). Conflict management

operates on the basis that conflict can be positive and thus focuses

on directing conflict toward constructive dialogue (Nemeth &

Owens, 1996; Rybak & Brown, 1997; Tjosvold, 1991).

In keeping conflicts constructive, the management of conflict

interaction has emerged as an important strategy. Putnam (1986)

argued that a conflict managed effectively can improve decision

making by “expanding the range of alternatives, increasing close

scrutiny of decision options, fostering calculated risks and enhanc-

ing cohesiveness. When managed ineffectively, conflict results in

dysfunctional behaviors and low group productivity” (p. 177).

Several researchers in the past have developed models of con-

flict behavior interaction (Blake & Mouton, 1964; Munduate &

Dorado, 1998; Thomas, 1976). These categories include avoidance

(passive, denial), distributive (confrontational, competitive), and

integrative (analytic, supportive). Bottger and Yetton (1988) sug-

gested that the quality of conflict management during group discus-

sion influences group performance. They differentiate between

positive and negative conflict management behaviors. Positive con-

flict management involves examination of competing knowledge

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

484 SMALL GROUP RESEARCH / October 2002

bases, exploration of alternatives, and the willingness of partici-

pants to argue for their points of view. Emphasis is on knowledge,

logical argument, and explanation. By contrast, negative conflict

management includes voting or coin tossing to resolve opinion dif-

ferences, “I-win-you-lose” dominance games, and the reluctance

of some participants to argue for their opinions. However, studies

focusing on conflict management behavior are rare, whereas the

consideration of the experience of conflict measured by question-

naires predominates.

Furthermore, when studying the occurrence of conflict in

groups, the distinction between the expression and the experience

of conflict has been formulated. Expressed conflict is studied

through behavior observation and categorization by experts. Expe-

rienced conflict is studied based on the appraisal carried out by the

members after a work group session.

Most of the studies on conflict in groups have used measures of

experienced conflict by group members, pointing out that different

conflict experiences may have implications for the expression of

conflict and for the strategies that a group uses to resolve or manage

it (O’Connor, Gruenfeld, & McGrath, 1993; Torres, Zornoza,

Prieto, & Peiró, 1998). In these studies, some antecedents of expe-

rienced conflict in continuing work groups have been identified.

Three variables especially affect the level of conflict that group

members experience and express: the type of task (O’Connor et al.,

1993; Torres et al., 1998), the communication medium

(Chidambaram, Bostrom, & Whynne, 1990; Poole, Holmes, & De

Sanctis, 1991; Zornoza, Prieto, Martí, & Peiró, 1993), and changes

over time in group development (Lebbie, Rhoades, & McGrath,

1996; McGrath & Hollingshead, 1994). However, group members’

interactions, with the objective of examining the actual expressions

of conflict and their antecedents, have hardly been researched.

The aim of this study is to test differences in quality and fre-

quency of conflict management behavior (expressed conflict man-

agement) in ongoing groups that work over two different communi-

cation media as a function of the following antecedents:

interactions between task and medium, and practice time.

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

Zornoza et al. / CONFLICT MANAGEMENT IN GROUPS 485

BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

MEDIA RICHNESS AND TASK

INTERACTIONS IN GROUP PERFORMANCE

Communication media vary in their “richness” (Daft & Lengel,

1986), “social presence” (Short, Williams, & Christie, 1976), and

“psychological proximity.” These qualities indicate the medium’s

capacity to convey shared meaning and to enable sociable, sensi-

tive, warm, immediate, and personal interaction. They decrease as

one moves, in order, from face-to-face (FTF) interaction (the rich-

est medium), to video, to audio, and to text communication.

Prior research on “lean” communication support systems has

revealed two robust effects on the group interaction process. First,

lean media promote more equal participation and influence among

group members (Kiesler et al., 1984; Siegel et al., 1986). Second,

by restricting the exchange of interpersonal cues, lean media exert a

depersonalizing, task-orientating, “cooling” effect on group inter-

action compared to FTF meetings. On the other hand, the frequency

of conflict that commonly occurs in a rich, intimate medium like

FTF interaction (especially for groups untrained or inexperienced

in managing conflict) often creates an “intimacy disequilibrium”;

that is, the amount of intimacy experienced exceeds the amount

desired. The lean, coding nature of electronic communication can

reduce conflict to a more moderate level by focusing on ideas and

issues rather than on personalities (Poole et al., 1991).

There are theoretical and empirical grounds for predicting two

alternative effects of different communication media on levels of

experienced conflict (McGrath & Hollingshead, 1994; Sproull &

Kiesler, 1991). One position (the media richness or filtered cues

approach) predicts that computer groups will experience higher

levels of conflict than FTF groups because electronic media tend to

foster feelings of anonymity and to depersonalize relationships

between users. Additionally, many mechanisms for regulating con-

flict among group members involve the use of nonverbal cues that

are more easily and more precisely communicated face to face.

Thus, computer groups will experience and express higher levels of

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

486 SMALL GROUP RESEARCH / October 2002

conflict than FTF groups (Daft & Lengel, 1984; Kiesler & Sproull,

1992). Poole et al. (1991) found that conflict in computer-mediated

communication (CMC) groups reached higher levels than in FTF

groups. A few studies have focused on the expression of conflict or

conflict management. Their results also show that FTF groups pres-

ent higher levels of positive conflict management and lower levels

of negative conflict management than CMC groups (Chidambaram

et al., 1990; Zornoza et al., 1993).

Strauss (1997) found a higher frequency of behaviors such as

explicit disagreements, exclamations, and superlatives in CMC

than in FTF, probably due to the need to compensate for the loss of

emphasis provided by nonverbal and paraverbal cues (Orengo,

Zornoza, Prieto, & Peirí, 2000). The findings obtained by Harmon

(1998) also suggest that audio’s “leanness” can benefit high-conflict

interaction.

However, in another study, Harmon, Schneer, and Hoffman

(1995) showed that audio communication was as good as FTF

interaction for building interpersonal agreement and support for

group decisions. The fact that audio groups built consensus around

a highly equivocal, value-laden task thought to be problematic for

lean media, and did so with greater participant satisfaction than in a

rich medium like FTF interaction, reinforces the findings of other

studies that have failed to support the media richness theory

(Kinney & Dennis, 1994; Valacich, Dennis, & Connelly, 1994).

Thus, the alternative perspective predicts that computer groups will

experience less negative conflict than FTF groups because elec-

tronic media tend to produce a more intense focus on the task and a

concomitant lack of attention to interpersonal aspects of the group.

Moreover, research on negotiation suggests that when parties can-

not see one another, contentious tactics are less likely to be used

(Carnevale, Pruitt, & Seilheimer, 1981; McGrath & Hollingshead,

1994). A number of studies show that a higher proportion of group

communications deals with instrumental versus expressive func-

tions in CMC interactions or in other lean media as compared to

FTF discussions (Hiltz, Johnson, & Turoff, 1986; Siegel et al.,

1986). Task focus in CMC discussions may also occur due to the

physical and cognitive effort required in communication. McGrath

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

Zornoza et al. / CONFLICT MANAGEMENT IN GROUPS 487

and Hollingshead (1994) pointed out that the high level of task

focus often found in computer-mediated groups reflects an

overconcentration on the production function at the expense of

group well-being and member support functions. However,

O’Connor et al. (1993) and Torres et al. (1998) did not find signifi-

cant differences on the level of experienced group conflict as a

function of the communication medium.

Faced with these inconclusive results, some authors have sug-

gested that the type of task should also be taken into consideration.

Several task taxonomies have been proposed (McLaughlin,

1980; Shaw, 1976; Steiner, 1972). McGrath (1984) presented a

circumplex model to try to synthesize research on tasks. The two

dimensions defining the space of that circumplex are (a) the kind

and degree of interdependence (from collaboration, to cooperation

or coordination, to conflict mixed-motive tasks or competition) and

(b) the degree to which the processes involve cognitive versus

behavioral activities. Therefore, this circumplex distinguishes four

main task types, which are related to each other as the four quad-

rants identified by the main performance process that each entails:

I, to generate (ideas or plans); II, to choose (a correct answer,

intellective tasks, or a preferred solution); III, to negotiate (conflict-

ing views or conflicting interests); and IV, to execute (in competi-

tion with an opponent or competing against external performance

standards). These types of tasks differ in terms of the degree to

which effective performance on them depends only on the trans-

mission of information among members of the group and collabo-

ration (Quadrant I); or requires cooperation and coordination

(Quadrant II); or also requires the transmission of values, interests,

personal commitment, and the like (Quadrant III).

Thus, as tasks differ in their complexity (Wood, 1986), they will

require different degrees of media richness (Daft & Lengel, 1986)

for their accomplishment. In fact, some authors have suggested a

contingency approach to deal with this issue. More specifically,

McGrath and Hollingshead (1994) formulated the task-media fit

hypothesis.

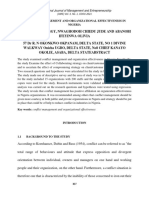

This model presents a four-by-four space defined in terms of the

four task types on the cognitive hemisphere of the circumplex (gen-

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

488 SMALL GROUP RESEARCH / October 2002

erate tasks, intellective tasks, judgment tasks, and mixed-motive

tasks) and the four media forms (CMC systems, audio systems,

video systems, and FTF systems) (see Figure 1). The best-fitting

combinations of information richness of task and media lie near the

main diagonal of the space (generating tasks–computer systems,

intellective tasks–audio and video systems, judgement tasks–audio

and video systems, and mixed-motive tasks–FTF systems). Con-

tours successively distant from that diagonal represent gradually

less well-fitting combinations.

Therefore, the effectiveness of a media system on a task will vary

with the fit between the richness of information that can be trans-

mitted via that system’s technology and the information richness

requirements for the task’s performance. A group process will be

effective in performing a task when the group expresses more posi-

tive than negative conflict management (Bottger & Yetton, 1988).

Tasks requiring groups to generate ideas (collaborative tasks)

involve the transmission of specific information; evaluative and

emotional connotations about message and source are hardly

required and are often considered a hindrance. So a low-richness

medium (like electronic mail) will be more effective than a high-

richness medium (like FTF) (Valacich et al., 1994). Tasks requiring

groups to solve intellective problems (cooperative tasks that

require collaboration and convergence) lie between the two

extremes of the richness continuum (computer systems and FTF)

but would be nearer to the computer system than to FTF. The fit will

be marginal at two extremes (in CMC to default and in FTF to

excess of media richness); however, it will be better in CMC, the

richness level of which is rather similar to that of the audio system.

On the other hand, tasks requiring groups to negotiate and solve

conflicts of interest (mixed-motive tasks) may require the transmis-

sion of maximally rich information, including not only facts but

also attitudes, affective messages, expectations, commitments, and

so on. Thus, for this type of task, a higher richness medium like FTF

will be more effective than CMC.

Many of the hypotheses presented in the task-media fit model

found support in the literature (Valacich et al., 1994). However,

only recently a systematic study of the model was reported by

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

Zornoza et al. / CONFLICT MANAGEMENT IN GROUPS 489

Computer-Mediated Face-

Communication Audio Video to-Face

Systems Systems Systems Systems

Generate tasks Good fit Marginal fit Poor fit Poor fit

Intellective tasks Marginal fit Good fit Good fit Poor fit

Judgment tasks Poor fit Good fit Good fit Marginal fit

Mixed-motive tasks Poor fit Poor fit Marginal fit Good fit

Increased potential richness of information transmitted

Figure 1: Task-Media Fit on Information Richness

SOURCE: McGrath and Hollingshead (1994).

Menecke, Valacich, and Wheeler (2000). These authors have inves-

tigated the full continuum of media proposed by the model for

intellective and negotiation tasks. The results obtained provide lim-

ited support for the task-media fit hypothesis. In fact,

for the intellective tasks the overall pattern of results does not sup-

port the task media fit hypothesis and in one instance contradicts its

predictions. On the other hand, when addressing negotiation tasks,

the pattern of results was largely consistent with the predictions of

the task media fit hypothesis. (p. 521)

In the discussion of this mixed evidence, the authors suggested that

“the richness construct must be considered in light of more than the

task; the process required to complete the task must also be consid-

ered” (p. 523).

One of the critical processes that contribute to effective team

performance is positive conflict management because it expands

the range of alternatives considered, increases close scrutiny of

decision options, fosters calculated risks, and enhances cohesive-

ness of the team (Putnam, 1986). In contrast, negative conflict man-

agement will hamper the results of the group.

This study analyzes whether the task-media fit will facilitate

positive conflict management and poor fit will promote negative

conflict management. The study will focus on expressed (behav-

ioral) conflict instead of experienced conflict as reported by the

team members to grasp the process of conflict management. The

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

490 SMALL GROUP RESEARCH / October 2002

CMC medium, the poorest in the media richness continuum, and

the FTF medium, the richest, have been considered in our study.

Furthermore, three tasks were used: a generating idea task that

would present a good fit in the CMC medium; a negotiating conflict

of interest task that, in turn, would present a good fit to the FTF

medium; and an intellective task that, according to the model, will

present a marginal fit to the CMC medium and a poor fit to the FTF

medium.

On the basis of the task-media fit model and the assumption that

a good fit will promote positive conflict management processes

whereas a poor fit will lead to negative conflict management pro-

cess, the following hypotheses are formulated:

Hypothesis 1a: For groups working on idea-generation tasks, more

positive conflict management is expected from CMC groups than

from FTF groups.

Hypothesis 1b: For groups working on idea-generation tasks, more

negative conflict management is expected from FTF groups than

from CMC groups

Hypothesis 2a: For groups working on intellective tasks, more positive

conflict management is expected from CMC groups than from FTF

groups.

Hypothesis 2b: For groups working on intellective tasks, more nega-

tive conflict management is expected from FTF groups than from

CMC groups.

Hypothesis 3a: For groups working on mixed-motive tasks, more posi-

tive conflict management is expected from FTF groups than from

CMC groups.

Hypothesis 3b: For groups working on mixed-motive tasks, more neg-

ative conflict management is expected from CMC groups than from

FTF groups

TIME AS ANTECEDENT OF POSITIVE

AND NEGATIVE CONFLICT MANAGEMENT

Most of the research on technology effects on group interaction

is cross-sectional. Very few studies have examined the interactions

of groups in multiple meetings over extensive periods of time

(McGrath & Hollingshead, 1994). Differences found between dif-

ferent communication technologies in group processes, like con-

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

Zornoza et al. / CONFLICT MANAGEMENT IN GROUPS 491

flict, can be explained by the novelty of the technology. Over time,

groups adapt the technology to perform their tasks, and differences

between media could disappear or change after a certain period of

time working with the new technology. Groups learn to use the

technology (McGrath & Hollingshead, 1994; Poole et al., 1991),

and thus, it is possible for experienced groups to use lean media to

convey rich communication. Furthermore, over time, the members

of the group can become better acquainted with each other and

develop shared work procedures so that they do not need to discuss

relational issues as much. This would enable a richer communica-

tion to take place over a lean medium (Lee, 1994; Walther, 1992,

1995).

Therefore, it is important to develop longitudinal studies for ana-

lyzing the changes in the use of the technology as a function of time

and the effects of these changes on group functioning (McGrath &

Berdahl, 1998).

It can be expected that the time group members interact over a

medium will be a significant antecedent of the level and type of

conflict that group members express. Results obtained by Lebbie et

al. (1996) suggest that most groups in each medium (FTF and

CMC) tend to decrease their communication in every interaction

category analyzed except off-task activity (7 weeks and seven ses-

sions). A majority of groups in both media showed a decrease in

their communication about the production functions of their groups

(planning, composition, and mechanics). In the same vein, Walther

(1994, 1996) also confirmed that the relational communication

increases with time, and this increase becomes more evident in

CMC. This suggests that as group members become better

acquainted with one another, with the task, and with the technol-

ogy, they need to focus less energy on production functions and are

free to focus more on off-task functions (well-being and member

support functions) or to reduce interaction time. Focusing on con-

flict management, Chidambaram et al. (1990) found that FTF

groups had higher positive conflict management than CMC groups,

initially, on decision-making tasks with no right answer. However,

this pattern was reversed in the third of four sessions, when CMC

groups managed conflict in a more positive way than FTF groups.

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

492 SMALL GROUP RESEARCH / October 2002

The novelty of the technology used by groups may require the

creation of standard operating procedure or rules for their interac-

tion to reduce uncertainty. Furthermore, the relative difficulty of

communicating large amounts of information quickly in CMC may

decrease the total amount of communication in which the groups

can engage in a given period of time in any type of communication

(including off-task or interpersonal interaction), hindering effec-

tive conflict management. But this problem could decrease over

time because of the improved mastery in using technology. In this

sense, Poole (1991) developed the Adaptive Structuration Theory

(AST). This theory stresses the importance of group interaction

processes in mediating the effects of any given technology. The

group actively adapts the technology to its own ends, resulting in a

restructuring of the technology as it is meshed with the group’s own

interaction system. The structure of a group is a patterning of group

activities that results from a continuing process called adaptive

structuration.

These results and rationale suggest the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4a: Over time, groups that work in the CMC medium will

develop more positive conflict management behavior to perform

the task.

Hypothesis 4b: Over time, groups that work in the CMC medium will

develop less negative conflict management behavior to perform the

task.

Hypothesis 5a: Over time, groups that work in the FTF medium will

develop more positive conflict management behavior to perform

the task.

Hypothesis 5b: Over time, groups that work in the FTF medium will

develop less negative conflict management behavior to perform the

task.

METHOD

DESIGN

To test the hypotheses, a laboratory experiment was carried out.

The experiment was a mixed, two-factor design; the first factor was

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

Zornoza et al. / CONFLICT MANAGEMENT IN GROUPS 493

task type (within factor) and the second was a communication

medium (between factor). Four independent tasks—one idea gen-

eration, two intellective, and one mixed motive—were used in each

of two synchronous communication media: FTF and CMC.

Descriptions of the tasks and media are provided below.

The design of this laboratory experiment tried to control some

“strange” variables to minimize potential threats to internal valid-

ity. All participants were randomly assigned to form the groups,

and those groups were randomly assigned to the media. Each group

completed four tasks in only one communication medium. Group

members remained the same in all sessions. Task-order effects

were also controlled.

TASKS

In accordance with the circumplex model (McGrath, 1984), this

study focuses on the axis that reflects levels of interdependence

(collaboration–conflict resolution). Tasks used represent three dif-

ferent categories of interdependence: collaborative or idea genera-

tion (group performance results from the aggregations of individ-

ual contributions from their members with low levels of conflict or

trade-offs required), cooperative or intellective tasks (in which the

members must combine their contributions under various con-

straints or trade-offs and are required to integrate members’ indi-

vidual products or efforts), and mixed-motive tasks (in which the

members must combine their individual contributions when they

have reasons both to cooperate and to compete with one another

with regard to the outcome). Mixed-motive tasks yield the most

conflict, whereas collaborative tasks yield the least conflict.

The specific tasks used in this study are as follows. In the idea-

generation task, each group was required to generate 10 proposals

of cultural activities to be organized during a cultural week in their

department or school. This task called for a period of individual

work prior to group work on the task.

In the intellective tasks, each member of the group was given a

part of the information necessary for carrying out the task, which

made it necessary to exchange the information to reach the solu-

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

494 SMALL GROUP RESEARCH / October 2002

tion. These tasks were logic problems with only one correct solu-

tion. In the first task, they had to choose, among several areas, the

best one in which to place a restaurant according to different crite-

ria. These criteria were known to all group members. Each partici-

pant received information about one geographical area and its

scores on the criteria. In the second task, the participants had to find

the first name and surname of one person who had been contracted

by a certain company. Each group member received the informa-

tion about one person, his or her name or surname, and information

about his or her contract conditions. The correct answer was

demonstrable and obvious when the complete information was

available for the group.

In the mixed-motive task, each group was divided into two sub-

groups. Each represented a company interested in buying 3,000 kg

of oranges. There was not more than 3,000 kg in stock, so groups

had to divide this amount. Each company had €18,000 to pay for

the oranges. Each had to choose the strategy that would allow it to

obtain as much profit as possible (this task was adapted from

Lewicki, Bowen, Hall, & Hall [1988]). In this case, the best strategy

was cooperative.

The tasks always required the group to develop a joint product.

Sometimes, this product was simply the aggregation of individual

ideas (idea-generation task), whereas others required some integra-

tion of the resources.

COMMUNICATION MEDIA

The research design employed two communication environ-

ments: FTF and CMC. FTF interaction is the richest medium from a

normative perspective, as it can convey both verbal and nonverbal

cues. CMC is the poorest medium. It eliminates all visual and ver-

bal cues from the sender and displays only text-based symbols to

convey information.

In the FTF condition, members of the group were put together in

the same room and could use a computer only to perform the task.

The FTF work sessions were recorded on video.

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

Zornoza et al. / CONFLICT MANAGEMENT IN GROUPS 495

CMC occurred through QUICKMAIL software for Apple.

QUICKMAIL was installed in a local network. It supported syn-

chronous communication and was very easy to use. However, prior

to the sessions, groups that worked in CMC received experimental

training to acquire competent use of the technology. This software

splits a user screen into a message-receiving area at the right por-

tion of the screen and a message-sending area at the left portion.

Each member of the group was located in a different room and used

his or her own workstation. Every member could only communi-

cate with the rest of the group through the computer. Group mem-

bers had been previously introduced, and they knew who was in

every other workstation. Each participant decided to whom to send

messages. The CMC messages exchanged were registered and

printed for analysis.

PARTICIPANTS

In this study, 48 participants were placed in 12 groups of 4. Six

groups worked in an FTF condition and another 6 in a CMC condi-

tion. Participants were students of psychology from the University

of Valencia, Spain, who volunteered for the study. They were all

from the same course (so they were acquainted each other). An

incentive existed for their participation, as it was one way to satisfy

a course requirement.

The ages of the participants ranged from 21 to 28 years. The

average age was 21.81 with a standard deviation of 1.86. More than

90% were between 21 and 23.

The gender composition of the sample was 12 men (25%) and 36

women (75%). The proportion of men to women was similar to that

among the students in the School of Psychology, and the composi-

tion of every group had a similar proportion.

MEASURES

Our measure of conflict management is the one used by Bottger

and Yetton (1988), based on Hall and Watson’s (1970) intervention

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

496 SMALL GROUP RESEARCH / October 2002

instructions. We measured expressed conflict and its quality (posi-

tive vs. negative) through the analysis of verbal group interaction.

Positive conflict management behavior is defined by these authors

using the following examples: He or she presents clear logical argu-

ments, encourages conflicting parties to share information that

underpins their beliefs, encourages a wider range of ideas than is

currently available, suggests alternatives that might be acceptable

to both conflicting parties, challenges early agreements by explor-

ing underlying beliefs, and withstands pressure to change that is not

supported by logical or knowledge-based arguments. Negative

conflict management behavior is characterized by the following

behaviors: He or she suggests voting, attempts to suppress differ-

ences in opinion, states preferences without offering a logical or

knowledge-based argument, takes an “I-must-win-you-must-lose”

approach, encourages or accepts early agreement without explor-

ing underlying beliefs or knowledge, seems to change his or her

mind only to avoid conflict or maintain harmony, and the like.

We added an “other” category to include some messages that

could not be classified in the previous ones.

Thus, the data analyzed in the present study are verbal interac-

tions of these groups during the work sessions. Two trained coders

analyzed the transcriptions of all the messages exchanged during

the FTF and CMC sessions. A message was defined as meaningful

when typed in the CMC or spoken aloud in the FTF groups. They

used the same observational categories for both conditions.

These judges codified the entire work sessions for both commu-

nication media. Interrater agreement between each pair of coding

messages using kappa (Cohen, 1960), as suggested by Weider-Hat-

field and Hatfield (1984), was calculated for the specific categories

used. The agreement rate between two raters was .75, a value that

fits in the upper part of the range characterized by Cohen (1960) as

a strong level (.61 to .80). In cases where disagreement occurred, a

third judge resolved the differences.

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

Zornoza et al. / CONFLICT MANAGEMENT IN GROUPS 497

SETTING

The experiment was conducted in a laboratory from the

Research Unit of Work and Organizational Psychology located on

the campus of the University of Valencia. The facility contained

five rooms and a technical control room. The biggest room was

used for the FTF condition. Participants in this condition were

seated around the table and could use a computer to obtain task

information. The use of the computer was voluntary because the

groups had the task information on paper too. Two cameras

recorded all sessions.

Each of the other rooms (four workstations) contained computer

terminals used in the CMC condition. In this condition, each partic-

ipant was placed in a room without having direct contact with the

other participants.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

When participants arrived at the experimental laboratory, they

were welcomed by two researchers, who gave them the general

instructions for the session. The description of the task that the par-

ticipants had to perform during the session and the specific rules for

performing it were delivered on paper to each member of the group.

The participants also had access to an electronic document shared

in the computer with the same information. Then the groups

worked on the task; when finished, they filled out several question-

naires using a computer.

The average duration of the sessions was 32.20 minutes (SD =

15.68, range = 24.38 to 36.20). The sessions carried out in the FTF

condition were significantly shorter (M = 21.58, SD = 8.18) than

those in the CMC condition (M = 42.79, SD = 13.79).

The groups met weekly, participating in 8 sessions during a 2-

month period. Groups performed task types in the following

sequence, which was held constant for every group in every condi-

tion: Session 1, intellective; 2, intellective; 3, idea generation; 4,

mixed motive; 5, idea generation; 6, mixed motive; 7, intellective;

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

498 SMALL GROUP RESEARCH / October 2002

and 8, intellective. To be able to assess the effects of experience

over time independently of the task type, we placed intellective

tasks early and late in the sequence. Two other types were alter-

nated in the intermediate sessions.

For testing Hypotheses 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b, 3a, and 3b, we used the last

session in each task type (Session 5 for idea generation, 6 for mixed

motive, and 7 for intellective). To guarantee the familiarity of the

participants with the medium and the task, we had to test the longi-

tudinal (learning) effect. We used data from the 2nd and 7th ses-

sions, which were both devoted to intellective tasks, to prove the

effects of time after 5 weeks. We were not able to use the 1st and 8th

sessions because of technical problems produced by video

recording.

Participants were highly involved in all cases. Previously, it was

announced that the attendance at the experimental sessions and the

quality of the results would be used to grade the practical course on

group psychology. Moreover, the groups competed against each

other for a cash prize (€120 for each communication condition)

awarded to those that obtained the best results on the tasks carried

out.

RESULTS

Because the hypotheses predicted a directional trend among the

treatments, planned comparisons were used to test the hypothe-

sized relationships. However, the data do not follow a normal distri-

bution, so we used nonparametric tests. Our sample was small, and

its variances differed significantly. To prove Hypotheses 1 (a and

b), 2 (a and b), and 3 (a and b), we used Mann-Whitney U for two

independent samples (FTF and CMC). In these cases, we used rela-

tive frequencies because we compared communication media, and

the total number of messages was higher in the FTF condition than

in the CMC condition.

To prove Hypotheses 4 (a and b) and 5 (a and b), we used

Wilcoxon Z for two dependent samples. In this case, we compared

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

Zornoza et al. / CONFLICT MANAGEMENT IN GROUPS 499

Session 2 with Session 7, so they were the same groups at two dif-

ferent moments.

The means and standard deviations of all conflict management

measures are presented in Table 1.

COMMUNICATION MEDIA

MODERATED BY TYPE OF TASK

Several comparisons were performed to test the differences in

positive conflict management and negative conflict management

between different media for each type of task separately (see

Table 2).

Results obtained for the idea-generation task show that the dif-

ference in positive conflict management between the two media is

not significant (U = 8.00, p = .132), whereas negative conflict man-

agement is significantly higher in CMC than in FTF (U = 3.00, p =

.015). Thus, Hypothesis 1a has not been supported and Hypothesis

1b has been contradicted. Although significant differences

appeared in the case of negative conflict management, they are not

in the direction hypothesized.

For the groups working on the intellective task, results show that

positive conflict management is significantly higher in FTF than in

CMC (U = 0.00, p = .002). Conversely, negative conflict manage-

ment is significantly higher in CMC than in FTF (U = 0.00, p =

.002). Thus, Hypotheses 2a and 2b have been contradicted.

Hypothesis 3a predicted that groups working in the FTF condi-

tion experience more positive conflict management on a mixed-

motive task compared with those using CMC. Hypothesis 3b pre-

dicted that groups working in the CMC condition experience more

negative conflict management than those using CMC on the same

type of task. Neither the hypothesis for positive nor the one for neg-

ative conflict management was supported. Thus, Hypotheses 3a (U =

14.00, p = .589) and 3b (U = 16.00, p = .818) were not supported.

There were no significant differences between FTF and CMC on

mixed-motive tasks.

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

500 SMALL GROUP RESEARCH / October 2002

TABLE 1: Sample Sizes, Means, and Standard Deviations for Positive and Negative

Conflict Management

Dependent Measure, Task Type n M SD

Positive conflict management, idea generation task

FTF 6 66.75 23.12

CMC 6 47.15 17.90

Negative conflict management, idea generation task

FTF 6 9.27 12.82

CMC 6 31.31 16.87

Positive conflict management, intellective task (Session 2, Time 1)

FTF 6 79.65 7.82

CMC 6 53.06 11.49

Negative conflict management, intellective task (Session 2, Time 1)

FTF 6 7.52 4.51

CMC 6 27.70 11.42

Positive conflict management, intellective task (Session 7, Time 2)

FTF 6 83.42 3.67

CMC 6 51.05 12.34

Negative conflict management, intellective task (Session 7, Time 2)

FTF 6 9.17 3.05

CMC 6 33.46 8.16

Positive conflict management, mixed-motive task

FTF 6 60.77 14.43

CMC 6 51.95 24.35

Negative conflict management, mixed-motive task

FTF 6 21.45 6.92

CMC 6 25.47 15.79

NOTE: FTF = face-to-face communication medium; CMC = computer-mediated communi-

cation medium.

CONFLICT MANAGEMENT

BEHAVIOR OVER TIME

To examine whether groups in the two media develop different

conflict management patterns over time, we examined the total

number of messages in the categories studied in intellective tasks

by medium over two group work sessions.

The CMC groups displayed significantly more positive conflict

management in Time 2 than in Time 1 (Z = –2.20, p = .028). Thus,

Hypothesis 4a was contradicted. However, there were no signifi-

cant differences in negative conflict management between Time 1

and Time 2 (Z = –1.15, p = .248). So Hypothesis 4b was not

supported.

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

Zornoza et al. / CONFLICT MANAGEMENT IN GROUPS 501

TABLE 2: Summary of Hypothesis Testing for Positive and Negative Conflict

Management

Dependent Measure—Hypothesis Hypothesis Support Test Result

Idea generation task

Positive CM—H1a: CMC > FTF Not supported U = 8.00, p = .132

Negative CM—H1b: FTF > CMC Contradicted U = 3.00, p = .015

Intellective task

Positive CM—H2a: CMC > FTF Contradicted U = 0.00, p = .002

Negative CM—H2b: FTF > CMC Contradicted U = 0.00, p = .002

Mixed-motive task

Positive CM—H3a: FTF > CMC Not supported U = 14.00, p = .589

Negative CM—H3b: CMC > FTF Not supported U = 16.00, p = .818

Time as antecedent of positive and

negative conflict management

Computer-mediated communication

Positive CM—H4a: Time 1 < Time 2 Contradicted Z = –2.20, p = .028

Negative CM—H4b: Time 1 > Time 2 Not supported Z = –1.15, p = .248

Face-to-face communication

Positive CM—H5a: Time 1 < Time 2 Not supported Z = –1.68, p = .093

Negative CM—H5b: Time 1 > Time 2 Not supported Z = –1.57, p = .115

NOTE: CMC = computer-mediated communication; FTF = face-to-face communication;

CM = conflict management.

On the other hand, no significant differences were found

between Time 1 and Time 2 in positive conflict management (Z = –

1.68, p = .093) or in negative conflict management (Z = –1.57, p =

.115) in FTF groups. Thus, the hypotheses formulated (5a and 5b)

were not supported.

DISCUSSION

This article studies the conflict in groups that work mediated by

new information technologies. It presents two innovations with

respect to the previous literature: (a) It considers expressed conflict

instead of experienced conflict and (b) it distinguishes two qualita-

tively different types of conflict (positive and negative conflict

management) and not just its frequency.

The aim of this study is to test differences in frequency and qual-

ity of conflict management behavior in ongoing groups that work

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

502 SMALL GROUP RESEARCH / October 2002

over two different communication media as a function of the inter-

actions between task and medium and the length of time of practice.

To clarify the media-task contingency fit model (task by medium

interaction) and its implications for conflict management behavior,

we formulated Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3. Our results do not support

the implications of the media-tasks contingency fit model for con-

flict management behavior. They follow the same direction as those

of Mennecke et al. (2000) and show a more complex pattern than

the one predicted by the model. On intellective tasks (medium-

moderated richness required), results show that FTF produces sig-

nificantly higher levels of positive conflict management and lower

levels of negative conflict management than CMC. However, on

idea-generation tasks (low richness required), FTF produces less

negative conflict management than CMC, and there are no signifi-

cant differences in positive conflict management. These results

suggest that the “assumed” overrichness of media for the task

requirements does not produce a hampering effect on conflict man-

agement behavior.

In any case, results suggest that CMC is not the most suitable

medium for idea-generation tasks or for intellective tasks. Perhaps

another medium richer than CMC, but less rich than FTF (e.g.,

audio or video), could show a better fit and could present higher lev-

els of positive conflict management and lower levels of negative

conflict management than those obtained in groups that work with

alternative media.

Contrary to the approach that the medium-task fit facilitates

group interaction processes (positive conflict management), it

could be considered that the processes could counteract the misfit

to achieve good results, even in misfit situations. We could consider

an inverted causality when task and medium do not fit. According

to the AST (Poole, 1991; Poole et al., 1990), groups could make an

effort to improve the management of divergence to compensate. If

this were the case, future research should consider the interactions

between group processes and media-task fit, avoiding mechanical

predictions from media and task fit or misfit.

Finally, no differences were found between FTF and CMC, in

either positive or in negative conflict management, in the groups

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

Zornoza et al. / CONFLICT MANAGEMENT IN GROUPS 503

that worked in mixed-motive tasks. Conflict management is one

mode by which groups structure this work, and it plays both a task

and maintenance function in groups (Kuhn & Poole, 2000). It may

be that the group in this type of task first needs to define its way of

managing and structuring the work before the influence of the tech-

nology used appears.

On the other hand, the effect of time (experience with the task

and with the use of the communication medium) on conflict man-

agement behaviors in both communication media, and for

intellective tasks, does not follow the hypothesized direction.

Results obtained do not support Hypotheses 4 and 5. In fact, in

CMC, positive conflict management decreases over time, and there

are no significant differences in FTF. These results do not support

those obtained by Lebbie et al. (1996), who suggested that in FTF,

as well as in CMC, groups tended to decrease their communication

in every interaction category analyzed except the off-task activity.

In their study, the period of time elapsed between the first and the

last sessions was 7 weeks, whereas in our study, it was 5 weeks (for

this analysis, we used the tasks performed in the 2nd and 7th

weeks). Results obtained by Chidambaram et al. (1990), showing

that the initial pattern of FTF groups (higher positive conflict man-

agement than CMC groups) was reversed over time (CMC groups

managed conflict in a more positive way than FTF groups), were

not supported by our results. Their groups worked for 1 month in

four sessions.

The interval of time of practice is not the only factor that influ-

ences how groups develop shared methodologies for the manage-

ment of the medium in the solution of complex tasks. Other pro-

cesses influence the direction and speed of the emergence of

procedures for sharing and integrating information and conflict.

More research is needed to identify the time period required for

these processes to emerge under different conditions.

Nevertheless, McGrath and Berdahl (1998) have highlighted

that the study of the use of technology by groups over time must

take “great care” to distinguish between two kinds of effects on

group functioning. On one hand, there are effects of any new tech-

nology, just because it is new, for the group, and these are likely to

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

504 SMALL GROUP RESEARCH / October 2002

be attenuated over time. On the other hand, there are specific effects

on process and performance of important group functions that arise

from specific features of this technology, and these may persist or

even increase over time. The study of different intervals is needed

to differentiate these two effects in CMC.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY AND

IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

In summary, when performance of work groups working with

different media is operationalized as expressed positive and nega-

tive conflict management, the predictions based on the task-media

fit hypothesis are not supported. Our results instead show that when

there are differences depending on the medium, FTF is a more suit-

able medium for conflict management than CMC, although it is

interesting to note that in more complex tasks, differences do not

appear. These results suggest that the impact of media-task fit on

conflict management is probably moderated by other group pro-

cesses and is not produced mechanically by it.

There are some limitations to our work, and so our results must

be interpreted in light of the particular tasks, subjects, conditions,

and communication technologies employed. First, we need to point

out the small size of the sample. Drawing on data from 12 groups

restricts our ability to generalize. Second, only two communication

media were used, and they are located at the extremes of the rich-

ness continuum. It would be necessary to use a medium with a mod-

erated richness level, such as video conference, to explore in more

detail the intermediate values of media richness. Third, the tempo-

ral period used may not be enough to allow the groups to develop

more suitable procedures in CMC for complex tasks.

The results of this study also show that more research is needed

in several directions. First, it is necessary to test the model with

other media (like audio or video) that can be located in more central

positions on the richness continuum, with the objective of seeing

whether there is a linear or a nonlinear function to describe the rela-

tionships between the amount of richness and the frequency and

quality of conflict (see Harmon et al., 1995).

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

Zornoza et al. / CONFLICT MANAGEMENT IN GROUPS 505

Second, group processes need to be explicitly considered in the

theoretical models, as AST points out. However, dynamic interac-

tion processes between media tasks and groups’behaviors display a

large array of possible combinations, and theoretical development

is needed to formulate models useful for clarifying the dynamic

processes of eventual adaptation to the new media.

Thus, future studies will have to analyze in depth the antecedents

of conflict with the aim of better understanding their dynamics and

efficacy. This is especially important for the distributed teams that

are more and more frequent in modern organizations.

REFERENCES

Blake, R. R., & Mouton, J. S. (1964). The managerial grid. Houston, TX: Gulf.

Bottger, P. C., & Yetton, P. W. (1988). An integration of process and decision schemes expla-

nations of group problem solving performance. Organizational Behavior and Human

Decision Processes, 42, 234-249.

Carnevale, P., Pruitt, D., & Seilheimer, S. (1981). The influence of positive affect and visual

access on the discovery of integrative solutions in bilateral negotiations. Organizational

Behavior and Human Decisions Processes, 1, 11-120.

Chidambaram, L., Bostrom, R., & Wynne, B. (1990). A longitudinal study of the impact of

group decision support systems on group development. Journal of Management Infor-

mation Systems, 7, 7-25.

Cohen, J. A. (1960). Coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Education and Psycholog-

ical Measurement, 20, 37-46.

Corey, M., & Corey, G. (1992). Group, process and practice. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/

Cole.

Daft, R. L., & Lengel, R. H. (1984). Information richness: A new approach to managerial

behavior and organizational design. Research in Organizational Behavior, 6, 191-233.

Daft, R. L., & Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media rich-

ness and structural design. Management Science, 32, 554-571.

Daft, R. L., Lengel, R. H., & Trevino, L. K. (1987). Message equivocality media selection

and manager performance: Implications for information systems. MIS Quarterly, 355-

366.

De Sanctis, G., & Poole, M. S. (1997). Transitions in teamwork in new organizational forms.

Advances in Group Processes, 14, 157-176.

Deutsch, M. (1973). The resolution of conflict. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hall, J., & Watson, W. H. (1970). The effects of a normative intervention on group decision

making performance. Human Relations, 23, 299-317.

Harmon, J. (1998). Electronic meeting and intense group conflict: Effects of a policy-modeling

performance support system and an audio communication support system on satisfaction

and agreement. Group Decision and Negotiations, 7, 131-155.

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

506 SMALL GROUP RESEARCH / October 2002

Harmon, J., Schneer, J., & Hoffman, L. R. (1995). Electronic meetings and established

groups: Audioconferencing effects on group structure and performance. Organizational

Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 61, 138-147.

Hiltz, S. R., Johnson, K., & Turoff, M. (1986). Experiments in group decision making, 1:

Communication process and outcome in face to face vs. computerized conferences.

Human Communication Research, 13, 225-252.

Hollingshead, A. B., & McGrath, J. E. (1995). Computer assisted groups: A critical review of

the empirical research. In R. A. Guzzo & E. Salas (Eds.), Team effectiveness and decision

making in organizations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kiesler, S., Siegel, J., & McGuire, T. W. (1984). Social psychological aspects of computer-

mediated communication. American Psychologist, 39, 1123-1134.

Kiesler, S., & Sproull, L. S. (1992). Group decision making and communication technology.

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 52, 96-123.

Kinney, S., & Dennis, A. (1994). Reevaluating media richness: Cues, feedback and task. In

Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh Annual Hawaii International Conference on System

Sciences, pp. 21-30.

Kottler, J. A. (1994). Beyond blame: A new way of resolving conflict in relationships. San

Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Kuhn, T., & Poole, M. S. (2000). Do conflict management styles affect group decision mak-

ing? Evidence from a longitudinal field study. Human Communication Research, 26,

558-590.

Lea, A. S. (1994). Electronic mail as a medium for rich communication: An empirical inves-

tigation using hermeneutic interpretation. MIS Quarterly, 18(2), 143-157.

Lea, M., & Spears, R. (1992). The social contexts of computer-mediated communication.

Hemmel Hampstead, UK: Harvester-Wheatsheaf.

Lebbie, L., Rhoades, J., & McGrath, J. E. (1996). Interaction process in computer mediated

and face to face groups. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 4, 127-152.

Lewicki, R. J., Bowen, D. D., Hall, D., & Hall, F. S. (1988). Experiences in management and

organizational behavior. New York: John Wiley.

McGrath, J. E. (1984). Groups: Interaction and performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall.

McGrath, J. E. (1990). Time matters in groups. In J. Galegher, R. Kraut, & C. Egido (Eds.),

Intellectual teamwork: Social and technological foundations of cooperative work.

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

McGrath, J. E. (1993). Time, task and technology in work groups: The JEMCO workshop

study. Small Group Research, 24, 283-421.

McGrath, J. E., & Berdahl, J. L. (1998). Groups, technology and time. Use of computers for

collaborative work. In R. Scott Tindale et al. (Eds.), Theory and research on small

groups. New York: Plenum.

McGrath, J. E., & Hollingshead, A. B. (1994). Groups interacting with technology. London:

Sage.

McLaughlin, P. R. (1980). Social combination processes of cooperative problem solving

groups on verbal intellective tasks. In M. Fishbein (Ed.), Progress in social psychology.

Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Mennecke, B. E., Valacich, J. S., & Wheeler, B. C. (2000). The effects of media and task on

user performance: A test of the task-media fit hypothesis. Group Decision and Negotia-

tions, 9, 507-529.

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

Zornoza et al. / CONFLICT MANAGEMENT IN GROUPS 507

Munduate, L., & Dorado, M. A. (1998). Supervisor power bases, cooperative behavior and

organizational commitment. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology,

7, 163-179.

Nemeth, C., & Owens, P. (1996). Making work groups more effective: The value of minority

dissent. In M. West (Ed.), Handbook of work group psychology. London: John Wiley.

O’Connor, K., Gruenfeld, D., & MacGrath, J. E. (1993). The experience effects of conflict in

continuing groups. Small Group Research, 24, 362-382.

Orengo, V., Zornoza, A., Prieto, F., & Peirí, J. M. (2000). The influence of familiarity among

group members, group atmosphere and assertiveness on uninhibited behavior through

three different communication media. Computers in Human Behavior, 16, 141-159.

Poole, M. S. (1991). Procedures for managing meetings: Social and technological innova-

tion. In R. Swanson & B. Knapp (Eds.), Innovation meeting management. Austin, TX:

3M Meeting Management Institute.

Poole, M. S., Holmes, M., & De Sanctis, G. (1991). Conflict management in a computer sup-

ported meeting environment. Management Science, 37, 926-953.

Putnam, L. L. (1986). Conflict in group decision making. In R. Y. Hirokawa & M. S. Poole

(Eds.), Communication and group decision making (2nd ed., pp. 114-146). Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rybak, C. J., & Brown, B. M. (1997). Group conflict: Communication patterns and group

development. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 22, 31-42.

Schmidt, S. M., & Kochan, T. A. (1972). Conflict: Toward conceptual clarity. Administrative

Science Quarterly, 17, 359-370.

Shaw, M. E. (1976). Group dynamics: The psychology of small groups. New York: McGraw-

Hill.

Short, J. A., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunica-

tion. London: Wiley.

Siegel, J., Dubrowsky, V., Kiesler, S., & McGuire, T. W. (1986). Group processes in com-

puter mediated communication. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Pro-

cesses, 37, 157-187.

Sproull, L. S., & Kiesler, S. (1991). Computers, networks & work. Scientific American, 265,

116-123.

Steiner, L. D. (1972). Group processes and productivity. New York: Academic Press.

Strauss, S. G. (1997). Technology, group process and group outcomes: Testing the connec-

tions in computer-mediated and face to face groups. Human Computer Interaction, 12,

227-266.

Thomas, K. W. (1976). Conflict and conflict management. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Hand-

book of industrial and organizational psychology. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Tjosvold, D. (1991). Conflict positive organization: Stimulate diversity and create unity.

Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Torres, M. J., Zornoza, A., Prieto, F., & Peiró, J. M. (1998). Análisis del funcionamiento de

grupos cooperativos y su incidencia sobre los resultados obtenidos en contexto de

groupware [Analysis of the functioning of cooperative groups and its implications on the

results obtained in a groupware context]. Paper presented at the IV Congreso Nacional de

Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, Valladolid, Spain.

Trevino, L. K., Lengel, R. H., & Daft, R. L. (1987). Media symbolism, media richness and

media choice in organizations: A symbolic interactions perspective. Communication

Research, 14, 553-574.

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

508 SMALL GROUP RESEARCH / October 2002

Valacich, J. S., Dennis, A. R., & Connelly, T. (1994). Idea generation in computer based

groups: A new ending to an old story. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision

Processes, 57, 448-467.

Walther, J. B. (1992). Interpersonal effects in computer mediated interaction: A relational

perspective. Communication Research, 19, 52-90.

Walther, J. B. (1994). Anticipated ongoing interaction vs. channel effects on relational com-

munication in computer mediated interaction. Human Communication Research, 40,

473-501.

Walther, J. B. (1995). Relational aspects of computer mediated communication: Experimen-

tal observations over time. Organization Science, 6, 186-203.

Walther, J. B. (1996). Computer mediated communication: Impersonal, interpersonal and

hyperpersonal interaction. Communication Research, 23, 3-43.

Wieder-Halfied, D., & Hatfied, J. D. (1984). Reliability estimation in interaction analysis.

Communication Quarterly, 32, 287-292.

Wood, R. E. (1986). Task complexity: Definition and construct. Organizational Behavior

and Human Decision Processes, 37, 60-82.

Zornoza, A., Prieto, F., Martí, C., & Peiró, J. M. (1993). Group productivity and telematic

communication. European Work and Organizational Psychologist, 3, 117-127.

Ana Zornoza is at the University of Valencia, Spain.

Pilar Ripoll is at the University of Valencia, Spain.

José M. Peiró is at the University of Valencia, Spain.

Downloaded from sgr.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 11, 2015

You might also like

- AWS Certified SysOps Administrator Practice Tests 2021 AWS Exam Difficulty Practice Questions With A - 1Document353 pagesAWS Certified SysOps Administrator Practice Tests 2021 AWS Exam Difficulty Practice Questions With A - 1dawagotNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 2 Review of LiteratureDocument38 pagesChapter - 2 Review of Literaturecity9848835243 cyber100% (2)

- B2 TestDocument18 pagesB2 TestTamara Cruz100% (1)

- Variables Associated With Negotiation Effectiveness: The Role of MindfulnessDocument13 pagesVariables Associated With Negotiation Effectiveness: The Role of MindfulnessgdelsiNo ratings yet

- PDF CommunicationDocument7 pagesPDF CommunicationScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- Jehn (1995)Document28 pagesJehn (1995)Ileana MarcuNo ratings yet

- CommunicationDocument1 pageCommunicationtwumNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Sharing in Context: The in Uence of Organizational Commitment, Communication Climate and CMC Use On Knowledge SharingDocument14 pagesKnowledge Sharing in Context: The in Uence of Organizational Commitment, Communication Climate and CMC Use On Knowledge SharingMuhammad SarfrazNo ratings yet

- Self-Concept, Interpersonal Relationship and Anger Management of City Transport and Traffic Management Office Personnel in Davao CityDocument11 pagesSelf-Concept, Interpersonal Relationship and Anger Management of City Transport and Traffic Management Office Personnel in Davao CityInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Rumor As Group Problem Solving DevelopmeDocument21 pagesRumor As Group Problem Solving DevelopmeKatia PerezNo ratings yet

- Behfar 202008Document21 pagesBehfar 202008ÏmñVâMPNo ratings yet

- Breaking The Sound of Silence Explication in The Use of Strategic Silence in Crisis CommunicationDocument24 pagesBreaking The Sound of Silence Explication in The Use of Strategic Silence in Crisis CommunicationgrupotripaNo ratings yet

- 352-Article Text-676-1-10-20171230Document11 pages352-Article Text-676-1-10-20171230andrianNo ratings yet

- Internal Communication in The Small and Medium Sized EnterprisesDocument14 pagesInternal Communication in The Small and Medium Sized EnterprisesMaulana Malik TambunanNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Communication in Sustainability & Sustainable StrategiesDocument6 pagesThe Importance of Communication in Sustainability & Sustainable StrategiesLimi LokajNo ratings yet

- Recognizing Dysfunctional Communications A Means of Improving Organizational PracticeDocument21 pagesRecognizing Dysfunctional Communications A Means of Improving Organizational Practicebhavikakhurana73No ratings yet

- Jehn.1997.A - Qualitative Analysis of Conflict Types PDFDocument29 pagesJehn.1997.A - Qualitative Analysis of Conflict Types PDFsavintoNo ratings yet

- S.no Topics NameDocument20 pagesS.no Topics NameranisultanNo ratings yet

- Informal Communication in OrganizationsDocument16 pagesInformal Communication in OrganizationsEmmaNo ratings yet

- ConflictDocument15 pagesConflictKeith OchoaNo ratings yet

- Dti Executive Summary Website VersionDocument21 pagesDti Executive Summary Website VersionFranco PisanoNo ratings yet

- Informs Organization Science: This Content Downloaded From 137.111.226.20 On Tue, 19 Jul 2016 13:01:29 UTCDocument21 pagesInforms Organization Science: This Content Downloaded From 137.111.226.20 On Tue, 19 Jul 2016 13:01:29 UTCJakub Albert FerencNo ratings yet

- The Role of Effective Communication in Strategic Management of OrganizationsDocument7 pagesThe Role of Effective Communication in Strategic Management of OrganizationsewrerwrewNo ratings yet

- 182 Wannenmacher 14 Management of Innovative CollaborativeDocument11 pages182 Wannenmacher 14 Management of Innovative CollaborativeDavid PereiraNo ratings yet

- Paper - Gestion Del CambioDocument12 pagesPaper - Gestion Del CambioJhonny ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Emotion in NegotiationDocument23 pagesEmotion in NegotiationvalmarNo ratings yet

- Ob FinalDocument9 pagesOb FinalUttu AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Managing Multicultural Teams: Bachelor of Business BX2051 - Managing PeopleDocument7 pagesManaging Multicultural Teams: Bachelor of Business BX2051 - Managing PeopleTara CurrinNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13Document3 pagesChapter 13alliahc.vergaraNo ratings yet

- A Contingence Perspective On The Study of The Consequences of Conflict Types The Role of Organizational CultureDocument25 pagesA Contingence Perspective On The Study of The Consequences of Conflict Types The Role of Organizational CultureMustafa Emin PalazNo ratings yet

- Conflict Management, A New Challenge - Id.enDocument8 pagesConflict Management, A New Challenge - Id.enOPickAndPlaceNo ratings yet

- Chidambaran 2005Document21 pagesChidambaran 2005rizki prahmanaNo ratings yet

- Application of Game Theory in Organisational Conflict Resolution: The Case of NegotiationDocument6 pagesApplication of Game Theory in Organisational Conflict Resolution: The Case of NegotiationMiguel MazaNo ratings yet

- 47-Article Text-116-1-10-20211109Document25 pages47-Article Text-116-1-10-20211109Nur AfifaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Human Relation in Solving Conflicts in An OrganizationDocument7 pagesThe Effect of Human Relation in Solving Conflicts in An OrganizationThirsha VNo ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Journal of AdvertisingDocument19 pagesTaylor & Francis, Ltd. Journal of Advertisingsunny nasaNo ratings yet

- Critical - Theory - of - Communication - in - Organizations: A - Meticulous - Discussion PDFDocument14 pagesCritical - Theory - of - Communication - in - Organizations: A - Meticulous - Discussion PDFAmeyu Etana KaloNo ratings yet

- Conflict Management, Efficacy, and Performance in Organizational TeamsDocument32 pagesConflict Management, Efficacy, and Performance in Organizational TeamsEmilia SorescuNo ratings yet

- Y and Z Generations at WorkplacesDocument18 pagesY and Z Generations at Workplaceslethikimoanh.ulisNo ratings yet

- 1990JAP LautenschlagerFlaherty ComputerAdmin Apl753310Document6 pages1990JAP LautenschlagerFlaherty ComputerAdmin Apl753310carolsolangebbNo ratings yet

- 2022 - The Influence of Cultural Intelligence and Emotional IntelligenceDocument20 pages2022 - The Influence of Cultural Intelligence and Emotional IntelligenceBaby CheahNo ratings yet

- The Vigilance Case StudyDocument4 pagesThe Vigilance Case StudymariaNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument28 pagesRetrievearturbaran.akNo ratings yet

- The Role of Emotions in Advertising A Call To ActionDocument11 pagesThe Role of Emotions in Advertising A Call To ActioneliNo ratings yet

- Uzzi 1997 Social Structure & EmbeddednessDocument34 pagesUzzi 1997 Social Structure & EmbeddednessPaola RaffaelliNo ratings yet

- Challenges of Growth at ProtegraDocument10 pagesChallenges of Growth at ProtegraLaz TrasaNo ratings yet

- Crisis Communication: How To Deal With ItDocument11 pagesCrisis Communication: How To Deal With ItamyostNo ratings yet

- Organziational CommunicationDocument15 pagesOrganziational CommunicationsyedtahamahmoodNo ratings yet

- A. Journal: The Role of Tacit Knowledge Management in ERP Systems Implementation.Document4 pagesA. Journal: The Role of Tacit Knowledge Management in ERP Systems Implementation.miri ardiansyahNo ratings yet

- Bechky SharingMeaning OrgSciDocument19 pagesBechky SharingMeaning OrgSciBruno Luiz AmericoNo ratings yet

- 7983 ArticleText 42567 1 10 20211218Document25 pages7983 ArticleText 42567 1 10 20211218Julia WojciechowskaNo ratings yet

- Coordinación de Conocimiento en Equipos de Alto RendimientoDocument32 pagesCoordinación de Conocimiento en Equipos de Alto Rendimientopatinpe_860802262No ratings yet

- Types of Conflict and Personal and OrganDocument18 pagesTypes of Conflict and Personal and OrganYayew MaruNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13Document12 pagesChapter 13Himangini SinghNo ratings yet

- Conflict Management As An Organizational Capacity: Survey of Hospital Managers in Healthcare OrganizationsDocument17 pagesConflict Management As An Organizational Capacity: Survey of Hospital Managers in Healthcare OrganizationsLejandra MNo ratings yet

- The Psychosocial Costs of Conflict Management Styles PDFDocument18 pagesThe Psychosocial Costs of Conflict Management Styles PDFElianaNo ratings yet

- I Nte rc0mm Unity, Bou ND A Ry-Spa N Nin G Knowledge ProcessesDocument13 pagesI Nte rc0mm Unity, Bou ND A Ry-Spa N Nin G Knowledge ProcessesabhishekvaidhavNo ratings yet

- Annottated Biblography 1500Document9 pagesAnnottated Biblography 1500JOSEPHNo ratings yet

- Reseach Proposal FinalDocument11 pagesReseach Proposal FinalTayebwa Duncan100% (1)