Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MUNRO The Emptiness

MUNRO The Emptiness

Uploaded by

SarahCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Being Happy - Andrew MatthewsDocument242 pagesBeing Happy - Andrew MatthewsLioe Stanley100% (4)

- Every Day Is The LotteryDocument7 pagesEvery Day Is The LotteryFedeNo ratings yet

- TM 11398Document592 pagesTM 11398krill.copco50% (2)

- AS1530.7 1998 Part 7 Smoke Control Door and Shutter Assemblies - Ambient and Medium Temperature Leakage Test ProcedureDocument18 pagesAS1530.7 1998 Part 7 Smoke Control Door and Shutter Assemblies - Ambient and Medium Temperature Leakage Test Procedureluke hainesNo ratings yet

- Yamaha CLP 170 Service ManualDocument122 pagesYamaha CLP 170 Service ManualicaroheartNo ratings yet

- Mamaoui PassagesDocument21 pagesMamaoui PassagesSennahNo ratings yet

- The Representation of Children and The Subject of Poverty in Mark Twains WritingDocument5 pagesThe Representation of Children and The Subject of Poverty in Mark Twains WritingIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Symbolical Language in TROTAMDocument8 pagesSymbolical Language in TROTAMHanae ELBOUCHTINo ratings yet

- Alice Munro and Alternate RealitiesDocument16 pagesAlice Munro and Alternate RealitiesSimone Buffon ScuottoNo ratings yet

- Irony and Isolation in A Rose For EmilyDocument11 pagesIrony and Isolation in A Rose For EmilyyooliuliNo ratings yet

- Aquel Micromundo PoéticoDocument8 pagesAquel Micromundo PoéticoNatalia WolfgangNo ratings yet

- Reassembling The FragmentsDocument24 pagesReassembling The FragmentsFrederic LefrancoisNo ratings yet

- Juxtaposing The Realistic and The Speculative Elements in Haruki Murakami's Kafka On The ShoreDocument4 pagesJuxtaposing The Realistic and The Speculative Elements in Haruki Murakami's Kafka On The ShoreIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Golden Chalice Good To House A God - Still Life in The RoadDocument27 pagesGolden Chalice Good To House A God - Still Life in The RoadsafiyaburnerNo ratings yet

- Example Essay Feb 2002Document4 pagesExample Essay Feb 2002Mandy LiNo ratings yet

- Desert PlaceDocument6 pagesDesert PlacedikaNo ratings yet

- Isle of IDocument18 pagesIsle of ITudor RomanNo ratings yet

- The Johns Hopkins University Press Theatre JournalDocument5 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University Press Theatre JournalSophie FelgentreuNo ratings yet

- Modelling From Well-Known Local and Foreign Poetry Writers: A. Examples of Symbolism in LiteratureDocument6 pagesModelling From Well-Known Local and Foreign Poetry Writers: A. Examples of Symbolism in LiteratureLoisBornillaNo ratings yet

- 2nd ReferenceDocument21 pages2nd ReferenceKellyNo ratings yet

- Symbolism in Frost's Poetry: Dr. Shyam Kumar ThakurDocument3 pagesSymbolism in Frost's Poetry: Dr. Shyam Kumar Thakurmonalisa.thesis2024No ratings yet

- Sample MLA PaperDocument8 pagesSample MLA PaperAllysonLee17281No ratings yet

- Waiting For The Barbarians by J. M. Coetzee, First Published in 1980 and Republished inDocument4 pagesWaiting For The Barbarians by J. M. Coetzee, First Published in 1980 and Republished indavid236635No ratings yet

- 6240-Besedilo Prispevka-15664-1-10-20171026Document16 pages6240-Besedilo Prispevka-15664-1-10-20171026Andra BaleaNo ratings yet

- Anti-Realism and The Pastoral ModeDocument8 pagesAnti-Realism and The Pastoral ModeLuke IsaacsonNo ratings yet

- Rogue Games Tabbloid - February 12, 2010 EditionDocument2 pagesRogue Games Tabbloid - February 12, 2010 EditionRogue GamesNo ratings yet

- wjec_a_level_hughes_plathDocument12 pageswjec_a_level_hughes_plathValeriaNo ratings yet

- 9: Spatial Perspectives in Alice Munro's "Passion": Giuseppina BottaDocument12 pages9: Spatial Perspectives in Alice Munro's "Passion": Giuseppina BottaenviNo ratings yet

- SS23 Catalog Copper Canyon PressDocument12 pagesSS23 Catalog Copper Canyon PresshoneromarNo ratings yet

- Metaphor and Metonymy in Joyce A Little CloudDocument10 pagesMetaphor and Metonymy in Joyce A Little CloudNeelam NepalNo ratings yet

- American Association of Teachers of French The French ReviewDocument9 pagesAmerican Association of Teachers of French The French ReviewahorrorizadaNo ratings yet

- Dialnet AgingMemoryAndIdentity 8259786Document10 pagesDialnet AgingMemoryAndIdentity 8259786Priyanka RoutNo ratings yet

- Baudelaires "Le Voyage"Document13 pagesBaudelaires "Le Voyage"Trifun StojoskiNo ratings yet

- “Who was the woman_”_ Feminine Space and the Shaping of Identity in The Sound and the FuryDocument15 pages“Who was the woman_”_ Feminine Space and the Shaping of Identity in The Sound and the FuryJosé Vilian MangueiraNo ratings yet

- Esslin Theatre of The AbsurdDocument14 pagesEsslin Theatre of The AbsurdEthan VerNo ratings yet

- Point of ViewDocument3 pagesPoint of ViewLung DănuţNo ratings yet

- Lawrence E. Bowling: College English, Vol. 12, No. 4. (Jan., 1951), Pp. 203-209Document8 pagesLawrence E. Bowling: College English, Vol. 12, No. 4. (Jan., 1951), Pp. 203-209Laura MinadeoNo ratings yet

- Learning Guide: EnglishDocument5 pagesLearning Guide: EnglishMary Kristine Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Fatum and Fortuna in Lucan's Bellum CivileDocument9 pagesFatum and Fortuna in Lucan's Bellum CivileElena OchoaNo ratings yet

- Absurdtheatre 1124873Document14 pagesAbsurdtheatre 1124873haydar severgeNo ratings yet

- Modelling From Well Known Fictions PDFDocument4 pagesModelling From Well Known Fictions PDFLoisBornilla100% (1)

- 10 30794-Pausbed 1259704-2987695Document9 pages10 30794-Pausbed 1259704-2987695Ahmet Gökhan BiçerNo ratings yet

- John Beverley, Soledad PrimeraDocument17 pagesJohn Beverley, Soledad PrimeraEdu J.GNo ratings yet

- Kara WalkerDocument29 pagesKara Walkerpapasmurf63No ratings yet

- Fox VoidDocument9 pagesFox VoidggrozsaNo ratings yet

- The Voyage of The Argonauts - Janet Ruth BaconDocument97 pagesThe Voyage of The Argonauts - Janet Ruth BaconFrederic LecutNo ratings yet

- Parody IslandDocument8 pagesParody IslandRaul A. BurneoNo ratings yet

- Sheldon W. Liebman - Robert Frost, RomanticDocument22 pagesSheldon W. Liebman - Robert Frost, RomanticPratyusha BhaskarNo ratings yet

- Lovecraft's Dream CycleDocument15 pagesLovecraft's Dream CycleScott RassbachNo ratings yet

- AURYLAITE, Kristina. Margaret Atwood's Alternative Spaces. Wilderness Tips and Death by Landscape.Document9 pagesAURYLAITE, Kristina. Margaret Atwood's Alternative Spaces. Wilderness Tips and Death by Landscape.GuilhermeCopatiNo ratings yet

- Great Gatsby Symbols ChartDocument3 pagesGreat Gatsby Symbols ChartWilliam ImhoffNo ratings yet

- Eisenstein TheTimeMachine 1976Document6 pagesEisenstein TheTimeMachine 1976Annu singhNo ratings yet

- Sartre on William Faulkner's Metaphysics of Time in The Sound and the Fury Justin SkirryDocument30 pagesSartre on William Faulkner's Metaphysics of Time in The Sound and the Fury Justin SkirryShadragon XxXNo ratings yet

- Alice Munro Narrative HistoricismDocument13 pagesAlice Munro Narrative HistoricismSimone Buffon ScuottoNo ratings yet

- Class and Comedy EssayDocument6 pagesClass and Comedy EssayEmma ShardlowNo ratings yet

- DAWSON, Joanna - 2009 - A Moon Without Metaphors - 65-75Document11 pagesDAWSON, Joanna - 2009 - A Moon Without Metaphors - 65-75dvm1010No ratings yet

- Death by Depiction: Absence in The Landscapes of The Group of Seven and in Margaret Atwood's Death by Landscape, Lara Lee MeintjesDocument12 pagesDeath by Depiction: Absence in The Landscapes of The Group of Seven and in Margaret Atwood's Death by Landscape, Lara Lee MeintjesLara MeintjesNo ratings yet

- Dream Analysis in Ancient MesopotamiaDocument12 pagesDream Analysis in Ancient Mesopotamiale_09876hotmailcomNo ratings yet

- Some Trick of The Moonlight Seduction and The Moving Image in Bram Stokers DraculaDocument25 pagesSome Trick of The Moonlight Seduction and The Moving Image in Bram Stokers DraculaabelNo ratings yet

- Simulated Environments: Successive Phases of The Image in Tarkovsky's SolarisDocument12 pagesSimulated Environments: Successive Phases of The Image in Tarkovsky's SolarisIvy RobertsNo ratings yet

- Structural Identification & Poc-1: Topic Page NoDocument35 pagesStructural Identification & Poc-1: Topic Page Nosiddansh100% (1)

- 5 25 17 Migraines PowerPointDocument40 pages5 25 17 Migraines PowerPointSaifi AlamNo ratings yet

- TSB-1139 8SC Wiring DiagramDocument2 pagesTSB-1139 8SC Wiring Diagramxavier marsNo ratings yet

- Data Sheet USB5 II 2019 05 ENDocument1 pageData Sheet USB5 II 2019 05 ENJanne LaineNo ratings yet

- Manual Epson L555Document92 pagesManual Epson L555Asesorias Académicas En CaliNo ratings yet

- Md. Rizwanur Rahman - CVDocument4 pagesMd. Rizwanur Rahman - CVHimelNo ratings yet

- James Coleman (October Files) by George BakerDocument226 pagesJames Coleman (October Files) by George Bakersaknjdasdjlk100% (1)

- Stages of SleepDocument2 pagesStages of SleepCamilia Hilmy FaidahNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitleddwky KrnwnNo ratings yet

- Yuxi CatalogueDocument16 pagesYuxi CatalogueSoltani AliNo ratings yet

- HDR10+ System Whitepaper: September 4, 2019 HDR10+ Technologies, LLCDocument14 pagesHDR10+ System Whitepaper: September 4, 2019 HDR10+ Technologies, LLCDragomir ConstantinNo ratings yet

- Schiavi Enc Met Page015Document1 pageSchiavi Enc Met Page015Adel AdelNo ratings yet

- Toro Homelite 3354-726Document8 pagesToro Homelite 3354-726Cameron ScottNo ratings yet

- Understanding Your Electricity Bill in PakistanDocument13 pagesUnderstanding Your Electricity Bill in PakistanGhayas Ud-din DarNo ratings yet

- Is-Cal01 Design Carbon Accounting On Site Rev.02Document6 pagesIs-Cal01 Design Carbon Accounting On Site Rev.02shoba9945No ratings yet

- Snag SummmariesDocument171 pagesSnag Summmarieslaltu adgiriNo ratings yet

- How To Keep Your Brain HealthyDocument3 pagesHow To Keep Your Brain HealthySyahidah IzzatiNo ratings yet

- Anthropological Thought Session by DR G. VivekanandaDocument277 pagesAnthropological Thought Session by DR G. Vivekanandahamtum7861No ratings yet

- 9701 s02 ErDocument14 pages9701 s02 ErHubbak KhanNo ratings yet

- Bristol Comp Catalog 4Document102 pagesBristol Comp Catalog 4Popica ClaudiuNo ratings yet

- EVM TechmaxDocument96 pagesEVM Techmaxnikhileshdhuri97No ratings yet

- Contoh Form Rko Obat PRB Per ApotekDocument19 pagesContoh Form Rko Obat PRB Per ApoteksaddamNo ratings yet

- Oil & Chemical Tanker Summer 7 - Prepurchase Survey Report - S&a 230098 PpsDocument62 pagesOil & Chemical Tanker Summer 7 - Prepurchase Survey Report - S&a 230098 Ppsp_k_sahuNo ratings yet

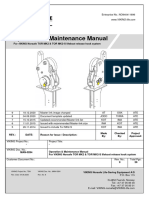

- SOM016 - Hook Release System For Life Boats. Norsafe TOR mk2.Document20 pagesSOM016 - Hook Release System For Life Boats. Norsafe TOR mk2.arfaoui salimNo ratings yet

- New WITTMANN Robots For Large and Small Injection Molding MachinesDocument4 pagesNew WITTMANN Robots For Large and Small Injection Molding MachinesMonark HunyNo ratings yet

- (12942) Sheet Chemical Bonding 4 Theory eDocument8 pages(12942) Sheet Chemical Bonding 4 Theory eAnurag SinghNo ratings yet

MUNRO The Emptiness

MUNRO The Emptiness

Uploaded by

SarahOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

MUNRO The Emptiness

MUNRO The Emptiness

Uploaded by

SarahCopyright:

Available Formats

Camden House

Chapter Title: “The Emptiness in Place of Her”: Space, Absence, and Memory in Alice

Munro’s Dear Life

Chapter Author(s): Ailsa Cox

Book Title: Space and Place in Alice Munro's Fiction

Book Subtitle: "A Book with Maps in It"

Book Editor(s): Christine Lorre-Johnston and Eleonora Rao

Published by: Boydell & Brewer; Camden House

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7722/j.ctt1wx934v.12

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Boydell & Brewer and Camden House are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Space and Place in Alice Munro's Fiction

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6: “The Emptiness in Place of Her”:

Space, Absence, and Memory in

Alice Munro’s Dear Life

Ailsa Cox

A LICE MUNRO’S 2012 COLLECTION, Dear Life, revisits many places

familiar from her previous work—mapping both domestic space and

the semi-rural landscapes of small town Canada. “In Sight of the Lake,”

“Amundsen,” and “Gravel” return to the key image of the lake, while

other stories (“To Reach Japan,” “Train”) echo her use of the transitional

space of the train in “Wild Swans” (Who Do You Think You Are? / The

Beggar Maid, 1978) and “Chance” (Runaway, 2004).1 Munro territory

is by its nature ambiguous and multidimensional. But these later stories

are especially marked by silence and absence, evoked by wintry land-

scapes, empty streets; or the fractured narrative viewpoint associated with

memory loss or repression. Munro has declared Dear Life to be her final

collection; it is a book that summarizes her career in many ways and, with

the autobiographical sequence, “Finale,” closes with a statement of its

origins in personal experience.

Bakhtin’s well-known concept of the chronotope, the configuration of

space and time that characterizes a specific text or genre, both symbolically

and structurally, helps us to understand the resonance of landscape and archi-

tecture in these stories. Munro uses her characters’ perception of external

space to map subjective experience, often locating her characters very pre-

cisely in relation to their immediate environment in order to register that

which is not seen or not understood or placed at the periphery of the con-

scious mind. In this chapter I shall focus on the relationship between space,

absence, and memory in two stories—“Train” and “Gravel”—the former an

example of third-person narration and free indirect discourse, while the latter

mimics autobiographical discourse through first-person narration.

Train

“Train,” the story of a drifter in rural Ontario, is a reminder of Munro’s

debt to Southern Gothic writers, so evident in her first collection, Dance

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lorre-Johnston.indd 119 4/18/2018 5:55:21 PM

120 AILSA COX

of the Happy Shades (1968). The relationship between the protagonist,

Jackson, and Belle, the isolated spinster whose farm he takes over, is espe-

cially reminiscent of Flannery O’Connor. Newly returned from the war,

Jackson jumps from the train just ahead of his stop:

Jumping off the train was supposed to be a cancellation. You roused

your body, readied your knees, to enter a different block of air. You

looked forward to emptiness. And instead, what did you get? An

immediate flock of new surroundings, asking for your attention in

a way they never did when you were sitting on the train and just

looking out the window. What are you doing here? Where are you

going? A sense of being watched by things you didn’t know about.

Of being a disturbance. Life around coming to some conclusions

about you from vantage points you couldn’t see. (DL, 176–77)

This is one of Munro’s most elliptical stories, constructed as a series of

loosely connected passages, shifting abruptly in time and space. This dis-

continuity is literalized in the passage above. Jackson’s physical disorien-

tation is also represented by the destabilization of narrative viewpoint; the

exchange of positions between spectator and observed and the invocation

of “vantage points you couldn’t see.” This paragraph does not appear

in the version published in the April 2012 issue of Harper’s Magazine;

its inclusion indicates the significance of spectatorship in the story as a

whole. The brief digression into second-person narration contributes to

this instability of viewpoint, and accentuates the sense of detachment.

Munro employs free indirect discourse throughout the story, focalized

mostly through Jackson, but also interweaving the speech of other char-

acters, especially Belle, making those voices vivid and immediate through

fragmented sentence structures.

In “Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel,” Bakhtin

discusses the significance of the chronotope of the road in works of fic-

tion, especially those where events may be governed by chance:

Time, as it were, fuses together with space and flows with it (form-

ing the road); this is the source of the rich metaphorical expansion

on the image of the road as a course: “the course of a life,” “to set

out on a new course,” “the course of history” and so on; varied and

multi-leveled are the ways in which a road turns into a metaphor,

but its fundamental pivot is the flow of time.2

Jackson is on course “to where he’s supposed to be” (DL, 177); we are

not told why he abandons his predetermined course for the open road,

the site of random encounters. He launches himself into a space which,

for him, represents contingency, but in fact consists of a different kind

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lorre-Johnston.indd 120 4/18/2018 5:55:21 PM

“THE EMPTINESS IN PLACE OF HER” 121

of order, an untamed natural world encroaching on the man-made—“a

railway track that seemed to have reverted from its normal purpose of

carrying people and freight to become a province of wild apple trees and

thorny berry bushes and trailing grapevines and crows” (DL, 177), and

other, unseen, birds, and trees he is unable to put a name to.

The linear road of narrative progression is also disrupted by unex-

pected changes of direction. At this point, the focalization changes briefly

to Belle, whose cow, Margaret Rose, discovers Jackson lurking on the

tracks near her land. Belle shelters Jackson, and then takes him on to run

the dilapidated farm. Jackson has found himself in a liminal space which

seems disconnected from modernity. This estrangement is heightened

when he hears “a peculiar sound . . . a clip-clop, clip-clop. Along with the

clip-clop some little tinkle or whistling” (DL, 180):

Over the hill came a box on wheels, being pulled by two quite small

horses. Smaller than the one in the field but no end livelier. And in

the box sat a half dozen or so little men. All dressed in black, with

proper black hats on their heads.

The sound was coming from them. It was singing. Discreet high-

pitched little voices, as sweet as could be. They never looked at him

as they went by. (DL, 180)

At first the singers are invisible to Jackson; and then he is invisible to

them. These figures are in fact Mennonite children on their way to

church, and later Jackson will help their families during harvest time.

Belle is also “a grown-up child” (DL, 189): “And her talk re-inforced this

impression, jumping back and forth into the past and out again, so that

it seemed she made no difference between their last trip to town and the

last movie she had seen with her mother and father, or the comical occa-

sion when Margaret Rose—now dead—had tipped her horns at a worried

Jackson” (DL, 189). Belle’s account of her childhood brings incongrui-

ties of its own, thwarting expectations the reader might have imported

from its Southern Gothic antecedents. Belle is no more a country per-

son than Jackson himself; the farm was originally bought as a summer

retreat by her family in Toronto. Like Jackson, Belle has found herself

here through circumstance, nursing her invalid mother after her journalist

father is killed on the railway line, presumably on the same track, where,

we have been told, the train slows down.

Belle’s name suggests the fairy tale “Beauty and the Beast.” Cocteau’s

dreamlike film, La belle et la bête, was released in 1946,3 around the time

when Jackson ventures onto the enchanted territory of Belle’s farm. In

most traditional versions, Beauty’s father has relocated to the country

under financial pressure, eventually journeying out in search of another

fortune. We might also remember that it is the affection between father

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lorre-Johnston.indd 121 4/18/2018 5:55:21 PM

122 AILSA COX

and daughter that prompts the father’s theft of the rose and her sub-

sequent atonement in his place. Belle’s father fictionalizes Belle as

“Pussycat” in his Toronto column, reserving for his wife the nickname

“Princess Casamassima, out of a book whose name, she said, meant noth-

ing anymore” (DL, 184). There are other princesses in this story, fan-

tasized figures from the English royal family. The cow, Margaret Rose,

is named after the younger of the British princesses, Elizabeth and

Margaret Rose (the adult Princess Margaret abandoned the second part

of her name). Belle’s father has been working on a historical novel about

another royal figure, Matilda. Nonetheless, it is Jackson who plays the

role of Beauty, lingering in a realm where time seems to be suspended;

and it is Belle who, like the Beast, makes a startling revelation when she is

close to death.

As we have seen in the opening section of the story, much is with-

held from the reader. Although we are granted access to Jackson’s interior

consciousness, aspects of his thoughts and memories are excluded. The

story frequently alludes to that which is unknown or forgotten, from the

names of the trees to the book “whose name . . . meant nothing any-

more” (DL, 184). Charles E. May’s chapter on Munro in his recent vol-

ume of criticism, I Am Your Brother, restates his long-held view that in

the short story reality is ineffable, and motivation inherently obscure.4 In

an article on Richard Ford’s story “Optimists,” Joe Frank takes this point

a little further, arguing that the mysterious and indeterminate aspects of

the modern short story may be related to nescience, “the human condi-

tion of being bound by limited and imperfect knowledge.”5 The gaps in

Jackson’s knowledge are linked to its willful suppression, and also a failure

to recognize that which is at least partially familiar.

In his discussion of the chronotope of the open road in novels by

Petronius, Cervantes, Gogol, and other writers, Bakhtin argues that in

these examples “the road is always one that passes through familiar ter-

ritory, and not through some exotic alien world.”6 As we have seen, the

anachronistic rural world Jackson experiences when he jumps from the

train does, indeed, appear as alien as the forest where Beauty’s father finds

himself lost “within thirty miles of his own house.”7 When he drives Belle

to a medical appointment in Toronto, she is struck by the changes she

sees on the way: “Are you so sure we are still in Canada?” (DL, 190).

Yet she also maps her own memories onto the city, identifying her old

school and the church where her parents were married, and imagining

her father’s newspaper just as it was, with his photograph at the head of

the column. Despite the length of his sojourn, stretching into the 1960s,

Jackson has never intended to stay with Belle on a permanent basis. His

sudden resumption of his journey appears, at first sight, to be a random

decision, but is in fact linked to the impossibility of escape from the famil-

iar territory he has tried to leave behind.

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lorre-Johnston.indd 122 4/18/2018 5:55:21 PM

“THE EMPTINESS IN PLACE OF HER” 123

At the hospital, Belle reveals more about her father’s death in a

lengthy analeptic passage, narrated entirely in direct speech. She describes

him looking at her naked body in the bathroom on the evening before

the accident that, in this version, is implicitly recast as suicide. Like

Jackson’s meeting with the Mennonite children, Belle’s account of her

father’s voyeurism is carefully staged. She gives an exact account of where

the bathroom was situated and how she carried the water up the stairs

and undressed:

There was a big mirror over the sink, you see it had a sink like a real

bathroom, only you had to pull out the plug and let the water back

into the pail when you were finished. . . . It must have been around

nine o’clock at night so there was plenty of light. It was summer, did

I say? That little room facing the west?

Then I heard steps and of course it was Daddy. My father. (DL,

195)

Once again, the sounds are heard from beyond a character’s imme-

diate proximity—offstage, as it were—announcing the imminent arrival

of something unseen, mysterious and disturbing. The steps are “not like

usual. Very deliberate” (DL, 196). The door opens and the father gazes

at her with a stare that is not “in any sense a normal look” and then says

“Excuse me . . . in a funny kind of voice” (DL, 196).

Belle’s exact reconstruction strains for the accuracy of a witness state-

ment, but it is also infused with a profound ambivalence. Traumatic or

violent incidents often occur in Munro’s stories, especially in the later

collections, but their significance lies not so much as plot devices as in

the way they are perceived or recollected. Belle herself downplays these

events: “It was nobody’s fault”; “It is just the mistakes of humanity” (DL,

198). Her motive for sharing her secret with Jackson is to communicate

something else, indirectly, as we shall see.

Belle’s description of “my face looking into the mirror and him look-

ing at me in the mirror and also what was behind me and I couldn’t

see” (DL, 196) leaves the reader to imagine what her father might be

doing, partially glimpsed on the threshold—perhaps masturbating.

Bakhtin ascribes an especially potent emotion charge to the threshold, as

“the chronotope of crisis and break in a life.”8 This charge is channeled

through the mutual gaze, caught in multiple reflections and refractions.

In the tale of Cupid and Psyche, which is an antecedent of “Beauty and

the Beast,” Psyche is banished by her husband, Cupid, when she defies his

order not to look at him. I am also reminded of Beauty’s magic mirror

in Cocteau’s film, which functions as a type of surveillance camera, keep-

ing Beauty informed of events in her absence. To look is to know, and to

exchange glances necessitates acknowledgment.

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lorre-Johnston.indd 123 4/18/2018 5:55:22 PM

124 AILSA COX

However the young Belle does not understand what she sees; she

is blind to a crucial element in this whole scenario, the word the older

Belle pronounces for Jackson’s benefit. The word is “sex” (DL, 198).

Munro displays the utterance as a single sentence paragraph, creating a

dramatic pause in Belle’s lengthy speech, and foregrounding the break-

ing of taboos. Her revelation, dramatic yet also banal, is intended to sig-

nal complicity in male sexual needs: “There should be acknowledgement,

that’s all I mean, places where people can go if they are in a situation. And

not be all ashamed and guilty about it. If you think I mean brothels, you

are right. If you think prostitutes, right again. Do you understand?” (DL,

198). Jackson says he does, but significantly does not meet her gaze.

Bakhtin emphasizes the subtlety of the threshold chronotope as the site

of sudden breaks and crises, which may operate implicitly through imagery.

The causal link between Belle’s uncalled for intimacy and Jackson’s depar-

ture is underplayed. Once again he embraces contingency, allowing random

events to carry him once more along the open road. Taking a walk from the

hospital, he wanders the streets of Toronto, finally joining a small crowd

gathered outside an apartment block whose caretaker is being taken away

by ambulance: “Jackson was one of those who didn’t bother to walk away.

He wouldn’t have said he was curious about any of this, more that he was

just waiting for the inevitable turn he had been expecting, to take him back

to where he’d come from” (DL, 200–201).

He takes on the caretaker’s job, once again seeming to settle down

into a routine existence until another seemingly random event brings even

more narrative disruption. This event parallels the incident between Belle

and her father, in that much of it takes place “offstage.” Jackson overhears

a woman enquiring after her runaway daughter, who has been staying in

the apartment block. He is outside his office, where the conversation is

taking place, but recognizes her just by her voice as his wartime sweet-

heart, Ileane Bishop. It was Ileane he was supposed to be meeting before

he jumped the train. Further analeptic passages chart their romance and

his failed attempt at sexual consummation while on leave. That failure

explains Jackson’s first disappearance, and its memory triggers his next

departure on a train heading north.

The chronotope of the threshold is invoked symbolically through the

many references to doors opening and closing during Ileane’s fruitless

visit to the apartment block as Jackson keeps himself out of sight. In an

interview with the New Yorker, Munro has said that this story is “all about

the man who is confident and satisfied as long as no sex gets in the way.

I think a rowdy woman tormented him when he was young.”9 In the

Harper’s version the form these torments take at the hands of Jackson’s

stepmother is more explicitly sexual than in the final version: “what she

called her fooling or her teasing when she gave him a bath” (emphasis

added). This final clause is removed from the Dear Life version.

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lorre-Johnston.indd 124 4/18/2018 5:55:22 PM

“THE EMPTINESS IN PLACE OF HER” 125

The critic Nicholas Royle refers specifically to Alice Munro when he

claims that “the space of the short story is closed, and in crucial ways,

blind.”10 This “blindness” is related to an instability of viewpoint, which

typically manifests itself in her work through the layering of voices and

the sudden shifts in time and space. Ellipses, silences, and omissions are all

aspects of this fundamental blindness. In “Train,” the protagonist’s iden-

tity is poised on a threshold between internal and external space, self and

other. In one of the story’s final analeptic passages, Munro describes the

night before Jackson leaves for the war, the night of his failed love-mak-

ing with Ileane, the minister’s daughter. A picture of George VI hangs on

the kitchen wall, with the excerpt of religious poetry he included in his

Christmas broadcast to the Empire in 1939:

And I said to the man who stood at the gate of the year,

“Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown.”

And he replied, “Go out into the darkness and put your hand into

the hand of God. That shall be to you better than light and safer

than a known way.” (DL, 213)

In the context of Jackson’s story, the morale-boosting symbolism of the

threshold and the poem’s journey into “darkness” is given a different,

personal, meaning, divested of its religious connotations. When, faced by

the prospect of reunion, made still more dreadful by the unmissable lime

green outfit Ileane has been making, Jackson chooses to remove himself:

“A person could just not be there” (DL, 214). The impersonal construc-

tion—“a person” rather than “he” or even “you”—blurs the viewpoint

between spectator and spectacle.

On the eve of his final departure, Jackson dreams about the

Mennonite boys singing in the cart. The image is uncanny, and made even

more so by its recapitulation, since, as Freud points out, the Unheimlich

is compounded by repetition. The Unheimlich is, of course, in dialogue

with the notion of “home,” and in these closing pages we may feel that

every new direction circles back on itself, returning Jackson to the very

place where he began.

Elizabeth Bowen claims that the short story’s “poetic tautness and

clarity” brings the form “to the edge of prose; in its use of action it is

nearer to drama than to the novel.”11 In his article “Theatricality in the

Short Story: Staging the Word?” Laurent Lepaludier comments on the

frequency of theatrical effects in a range of texts, identifying passages

where the dramatic mode appears to overcome the narrative modal-

ity.12 In “Train” and in “Gravel,” which I discuss next, events are often

“staged” in the telling, and this “staging” effect positions characters care-

fully in relation to a mise-en-scène.

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lorre-Johnston.indd 125 4/18/2018 5:55:22 PM

126 AILSA COX

Bowen goes on to say that “the story should be as composed, in the

plastic sense, and as visual as a picture.”13 There could not be a stronger

example of this “plasticity” than Munro’s work. She arranges her words

precisely on the page, sometimes revising superficially minor details of

layout between magazine publication and a story’s appearance in a col-

lection. That truncated line, “Sex” (DL, 198), demonstrates her deploy-

ment of fractured paragraphs as a rhythmic and dramatic device. (See also

the jagged intensity of the closing pages of “Dolly,” where the abbre-

viated paragraphs speed up narrative pace; and the slower unfurling of

thoughts at the close of “Leaving Maverley”). The chronotopic proper-

ties of the short story genre in general, and Munro’s work in particular,

are grounded in fluid concepts of time and space, and in a special affinity

with the present moment. The dislocations and displacements of “Train”

are made possible by this inherent fluidity. Bakhtin says that “the chro-

notope, functioning as the primary means for materializing time in space,

emerges as a center for concretizing representation.”14 His analysis of

the representational significance of the chronotope stresses an increased

density of temporal markers, but we might also consider heightened

awareness of the spaces the characters inhabit, both in their fictional envi-

ronments and in the material spaces on the page, as a function of a short-

story chronotope.

Gravel

Coral Ann Howells begins her 1998 study of Alice Munro with an invi-

tation to study a map of Canada, homing in on Southwestern Ontario,

where most of the stories are set. Howells points out that while these fic-

tional mappings include social observation, they transcend external docu-

mentation, explaining that their narrators “are fascinated by dark holes

and by unscripted spaces.”15 A later Munro story is even entitled “Deep-

Holes” (TMH). “Gravel” takes its title from the unremarkable gravel pit

that serves as the closest thing to a landmark for a homodiegetic narrator

reminiscing about childhood, beginning with the simple statement: “At

that time we were living beside a gravel pit” (DL, 91). Dear Life is full of

such temporal indeterminacies: the previous story, “Leaving Maverley,”

begins with an allusion to “the old days” (DL, 67). Brief references in this

story to the atom bomb, Vietnam, dope-smoking, and Cuba suggest the

nineteen sixties or seventies. Other details, notably the narrator’s name

and gender, are also withheld in a story that is so much concerned with

secrecy, estrangement, and the unfathomable nature of another’s subjec-

tivity—including our own younger selves, concealed within an irretriev-

able past.

“The old gravel pit out the service-station road” (DL, 91) embodies

the notion of a marginal territory at the edge of town, a space that figures

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lorre-Johnston.indd 126 4/18/2018 5:55:22 PM

“THE EMPTINESS IN PLACE OF HER” 127

often in Munro’s fiction. “Voices,” along with the other autobiographi-

cal pieces in the “Finale” section of Dear Life, revisits this in-between

space: “Our family was out of town but not really in the country” (DL,

287). For the characters in “Gravel” the movement out of town involves

a decline in social status. Rather like the lady in the border ballad, “The

Raggle Taggle Gypsy,” the mother has gladly forsaken her silver and her

china and her books and her silk nightdresses and her diamond ring and

her decorating scheme for a life at the margins with a feckless lover. Unlike

the fine lady in the ballad, she has taken her two children with her to live

in a trailer with Neal, a university dropout who has taken up acting.

The gravel pit stands for a life at the margins; its origins and purpose

not entirely clear. This deep hole also stands for vacancy and absence,

marking the erasure of what we might call the narrator’s pre-history,

the time before the move. “I barely remember that life,” the narrator

observes, perhaps not surprisingly as she was the younger child, not yet

old enough for school (DL, 91). Here the adult narrator is remember-

ing the act of recollection, at the prompting of the older child, Caro.

Differentiating between what he calls “pure recollection” and “habit

memory” (usually practical skills and knowledge), Henri Bergson refers

to the “radical powerlessness of pure memory.”16 Recollection of a par-

ticular event, or of a place, is involuntary, partial, and subject to change.

It cannot be willed into existence. For the narrator as a child, memories

of the old house consist of little more than the pattern of the wallpaper—

a source of frustration for Caro. The adult narrator is piecing together

fragments of involuntary memory that may also be conditioned by the

passing of time.

For the reader, the gravel pit may be a source of anxiety; despite an

emphasis on its relatively shallow depth, the careful description in the

opening paragraph seems to foreshadow disaster. We may also be unset-

tled by the attention Munro pays to the family dog, Blitzee, whose new-

found country lifestyle includes hunting for squirrels and groundhogs,

much to the distress of the older child, Caro. While the other members

of the family are displaced from their origins, Blitzee has found her true

element. When Neal chides Caro, telling her that predation is a natural

instinct, Caro responds:

“She gets her dog food,” Caro argued, but Neal said, “Suppose she

didn’t? Suppose some day we all disappeared and she had to fend for

herself?”

“I’m not going to,” Caro said. “I’m not going to disappear, and

I’m always going to look after her.” (DL, 92)

Neal is alluding to a post-apocalyptic future, after “the bomb”; the use

of the iterative in the account of this particular conversation—“Caro

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lorre-Johnston.indd 127 4/18/2018 5:55:22 PM

128 AILSA COX

was quite upset by this, and Neal would have a talk with her” (DL,

92)—suggests that this is an ongoing exchange, endlessly replayed by

the two of them.

The irony of Caro’s words will be revealed at the story’s climax,

when she misguidedly stages an attempt to rescue Blitzee from the water-

filled pit. Caro does, indeed, most tragically “disappear,” and our misgiv-

ings about this pit are fulfilled by that denouement. This is far from the

first reference to drowning in Munro’s oeuvre, other examples includ-

ing “Miles City, Montana” (The Progress of Love, 1986), “Pictures of the

Ice” (Friend of My Youth, 1990) and “Child’s Play” (Too Much Happiness,

2009). In “Gravel,” the drowning completes a pattern of disappearances,

both symbolic and real. Neal is himself a spectral figure,17 his acting role

as Banquo’s ghost well suited to his penchant for “giving yourself over,

blending with others” (DL, 95).

Acting and play-acting are also favorite tropes in Munro’s fiction. In

an article on theatricality as distantiation in her earlier work, Lee Garner

and Jennifer Murray note that acting or the recasting of real life as perfor-

mance facilitates an internal split between observer and participant: “The

ironic observing distance is one from which the character/reader may feel

protected from the potential violence of certain moments of excess, but

it is equally one from which the fantastic complexity of the business of

being human may be glimpsed.”18 Neal retreats into the role of observer,

remaining entirely passive, making no effort to save Caro when the alarm

is raised; staying away from her funeral, because he “didn’t believe in

funerals” (DL, 105), and abdicating the role of father when his son is

born shortly after the child’s death. Fittingly, the family snowman is nick-

named “Neal”; we all know that snowmen inevitably melt into nothing.

Before Caro’s last, fatal act of make-believe, she stages several other inci-

dents with the dog, hiding Blitzee under her coat on the school bus and

leaving her on the porch of the old house, as if she had made her way back

of her own accord. Blitzee makes a genuine, if short-lived, disappearance,

when “another dog,” perhaps a wolf, is glimpsed by the mailbox (DL,

98); this phantom wolf also vanishes, and, according to Neal, probably

never existed. Curiously, the name originally chosen for the unborn child

the mother is carrying is rather like a dog’s name—“Brandy” (DL, 98).

This child will make its entry into the world soon after Caro has disap-

peared from it.

The ambiguities, invisibilities, and absences of the story are height-

ened by the winter landscape: “Those short winter days must have

seemed strange to me—in town, the lights came on at dusk. But children

get used to changes. Sometimes I wondered about our other house. I

didn’t exactly miss it or want to live there again—I just wondered where

it had gone” (DL, 96). Landscape, weather, and the seasons evoke a lim-

inal state, in which time is suspended and actions become play-acting,

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lorre-Johnston.indd 128 4/18/2018 5:55:22 PM

“THE EMPTINESS IN PLACE OF HER” 129

without serious consequences. As winter reaches its end, the pit fills with

melted snow; it has now become a lake, “still and dazzling under the clear

sky” (DL, 100). The spectacle fascinates Caro. The children’s Saturday

activities with their father have included going to the movies, eating out,

and looking at Lake Huron. Looking at this artificial lake provides the

children with an alternative source of entertainment.

As I have suggested in my analysis of “Train,” Munro often uses land-

scape to enact the erasure of memory and the absence of knowledge—or

even its suppression. Caro and Neal contest each other’s factual accuracy;

she corrects his claim that wolves hibernate and ignores his other false

assumption, that dogs are immune from drowning. Toward the end of

the story, the narrator’s crucial failure to act is recounted, along with the

various unsatisfactory explanations supplied, much later, in counseling.

Caro orders her sibling to tell the adults “that the dog had fallen into the

water and Caro was afraid she’d be drowned” (DL, 102). But there is

a delay. The moment is reconstructed through that most involuntary of

memories, the dream:

When I dream of this, I am always running. And in my dreams I am

running not towards the trailer but back towards the gravel pit. I

can see Blitzee floundering around and Caro swimming towards her,

swimming strongly, on the way to rescue her. I see her light-brown

checked coat and her plaid scarf and her proud successful face and

reddish hair darkened at the end of its curls by the water. All I have

to do is watch and be happy—nothing required of me, after all.

What I really did was make my way up the little incline towards

the trailer. And when I got there I just sat down. Just as if there had

been a porch or a bench, though in fact the trailer had neither of

these things. I sat down and waited for the next thing to happen.

(DL, 102–3)

This last phrase, “waited for the next thing to happen,” echoes the final

line of “To Reach Japan,” where another child of an adulterous mother

“just stood waiting for whatever had to come next” (DL, 30). Both

lines imply that the child is a spectator, rather than a participant, in the

events of the story; they suggest disempowerment and fatalism. I am also

reminded of a much earlier story from Munro’s first collection, Dance of

the Happy Shades. In “Boys and Girls,” the narrator recollects disobeying

her father’s instructions to close a gate to stop a horse escaping, opening

it wider instead: “I did not make any decision to do this, it was just what I

did” (DHS, 125). Here too, no rational explanation can be made for the

child’s perverse behavior.

These events are, of course, interpreted through hindsight at some

undetermined point in time, long after their original occurrence. Despite

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lorre-Johnston.indd 129 4/18/2018 5:55:22 PM

130 AILSA COX

those counseling sessions, exploring various possible scenarios to account

for her silence, the anonymous narrator expresses a degree of ambiva-

lence toward “all the eviscerating that is done in families these days”; “My

mother cannot be made to recall any of those times” (DL, 106), any more

than the narrator’s younger self was able to remember the old house. But

unlike Caro, the narrator does not attempt to force those memories.

As we have seen, “pure memory” cannot be summoned at will, sup-

plying the missing links in a chain of events. According to Bergson, there

is no such thing as a self-contained present moment within the flow of

time. What we think of as the present disappears into the past as it arises,

and should be conceptualized as the intersection of memory and percep-

tion. If that is the case, then perhaps the “radical powerlessness of pure

memory”19 overlaps with the gaps in decision-making.

Once again, the threshold of the chronotope is invoked, the chro-

notope of crisis and life change, as the child lingers by the trailer before

knocking. Meeting Neal again, the narrator asks him, “What do you think

Caro had in mind?” (DL, 108). He offers some suggestions, but no con-

clusive answer, telling her not to waste her time, to just get on with her

life. The “ironic observing distance” described by Lee and Garner does

offer the potential for survival. He says: “Accept everything and then

tragedy disappears. Or tragedy lightens, anyway, and you’re just there,

going along easy in the world” (DL, 109).

But his are not the story’s final words. It closes by returning to that

moment reconstructed, or partially reconstructed from memory and

recurring in dreams: “. . . in my mind, Caro keeps running at the water

and throwing herself in, as if in triumph, and I’m still caught, waiting for

her to explain to me, waiting for the splash” (DL, 109). The gravel pit,

we have been told, is filled in now, with a house on top of it (the narrator

speculates that the pit might have been intended for the foundations of a

house when it is first described). We might interpret the pit’s disappear-

ance as the negation of memory; and yet every absence is in dialogue with

presence, just as silence is in dialogue with speech.

Many of the other stories in Dear Life deal with absence and bereave-

ment, marking these absences through spatial metaphors or the per-

ception of space. In “Leaving Maverley,” which immediately precedes

“Gravel” in the collection, the protagonist’s sick wife spends several years

in hospital before dying in the story’s closing pages:

Isabel was finally gone. They said “gone,” as if she had got up and

left. When some one had checked her about an hour ago, she had

been the same as ever, and now she was gone.

He had often wondered what difference it would make.

But the emptiness in place of her was astounding. (DL, 89–90)

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lorre-Johnston.indd 130 4/18/2018 5:55:22 PM

“THE EMPTINESS IN PLACE OF HER” 131

The stories in Dear Life have titles as cryptic as any in the late collec-

tions—most of them consisting of a single word. If we had to choose an

alternative title for “Gravel,” “the emptiness in place of her” would serve.

Many of the stories in this collection, and in Munro’s work as a whole, are

haunted by the dead, or by characters who, like Jackson, withhold them-

selves from others. Silences and absences are made palpable, and although

the past is irretrievable, memory strives to fill both the psychic and the

spatial void.

Notes

1 The following editions of Alice Munro’s works are cited in this chapter: Dance

of the Happy Shades (London: Penguin, 1983), hereafter cited as DHS; Dear Life

(London: Chatto & Windus, 2012), hereafter cited as DL; Friend of My Youth

(New York: Knopf, 1990), hereafter cited as FY; The Progress of Love (New York:

Knopf, 1986), hereafter cited as PL; and Too Much Happiness (London: Chatto &

Windus, 2009), hereafter cited as TMH.

2M. M. Bakhtin, “Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel,” in The

Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by M. M. Bakhtin, ed. Michael Holquist, trans.

Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992),

244.

3 Jean Cocteau, dir. La belle et la bête, DVD, Discina, 1946.

4 Charles E. May, “The Short Story Way of Meaning: Munro,” in I Am Your

Brother: Short Story Studies (Long Beach, CA: CreateSpace Independent Publish-

ing Platform, 2013), 235–57.

5 Joseph Frank, “American Laconic: Nescience and Realism in Richard Ford’s

‘Optimists,’” Short Fiction in Theory and Practice 4, no. 1 (2014): 25.

6 Bakhtin, “Forms of Time,” 245 (original emphasis).

7 Iona Opie and Peter Opie, eds., The Classic Fairy Tales (London: Oxford Uni-

versity Press, 1974), 140.

8 Bakhtin, “Forms of Time,” 248 (original emphasis).

9 Deborah Treisman, “On ‘Dear Life’: An Interview with Alice Munro,” New

Yorker, 20 November 2012, http://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/

on-dear-life-an-interview-with-alice-munro.

10 Nicholas Royle, “Spooking Forms,” Oxford Literary Review 26, no. 1 (2004):

156.

11 Elizabeth Bowen, “The Faber Book of Modern Short Stories,” in The New Short

Story Theories, ed. Charles E. May, 256 (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1994).

12 Laurent Lepaludier, “Theatricality in the Short Story: Staging the Word?”

Journal of the Short Story in English 51 (Autumn 2008): 17–28.

13 Bowen, “The Faber Book of Modern Short Stories,” 260.

14 Bakhtin, “Forms of Time,” 250.

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lorre-Johnston.indd 131 4/18/2018 5:55:22 PM

132 AILSA COX

15Coral Ann Howells, Alice Munro (Manchester: Manchester University Press,

1998), 3.

16Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory, trans. Nancy Margaret Paul and W. Scott

Palmer (New York: Zone Books, 1988), 141.

17 In my chapter “‘Almost Like a Ghost’: Spectral Figures in Alice Munro’s Short

Fiction,” in Liminality and the Short Story: Boundary Crossings in American,

Canadian, and British Writing, ed. Jochen Achilles and Ina Bergmann (London:

Routledge, 2015), I discuss Munro’s use of ghost-like figures in more detail.

18 Jennifer Murray and Lee Garner, “From Participant to Observer: Theatrical-

ity as Distantiation in ‘Royal Beatings’ and ‘Lives of Girls and Women’ by Alice

Munro,” Journal of the Short Story in English 51 (Autumn 2008): 155.

19 Bergson, Matter and Memory, 141.

This content downloaded from

213.181.237.234 on Mon, 27 Feb 2023 08:00:34 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Lorre-Johnston.indd 132 4/18/2018 5:55:22 PM

You might also like

- Being Happy - Andrew MatthewsDocument242 pagesBeing Happy - Andrew MatthewsLioe Stanley100% (4)

- Every Day Is The LotteryDocument7 pagesEvery Day Is The LotteryFedeNo ratings yet

- TM 11398Document592 pagesTM 11398krill.copco50% (2)

- AS1530.7 1998 Part 7 Smoke Control Door and Shutter Assemblies - Ambient and Medium Temperature Leakage Test ProcedureDocument18 pagesAS1530.7 1998 Part 7 Smoke Control Door and Shutter Assemblies - Ambient and Medium Temperature Leakage Test Procedureluke hainesNo ratings yet

- Yamaha CLP 170 Service ManualDocument122 pagesYamaha CLP 170 Service ManualicaroheartNo ratings yet

- Mamaoui PassagesDocument21 pagesMamaoui PassagesSennahNo ratings yet

- The Representation of Children and The Subject of Poverty in Mark Twains WritingDocument5 pagesThe Representation of Children and The Subject of Poverty in Mark Twains WritingIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Symbolical Language in TROTAMDocument8 pagesSymbolical Language in TROTAMHanae ELBOUCHTINo ratings yet

- Alice Munro and Alternate RealitiesDocument16 pagesAlice Munro and Alternate RealitiesSimone Buffon ScuottoNo ratings yet

- Irony and Isolation in A Rose For EmilyDocument11 pagesIrony and Isolation in A Rose For EmilyyooliuliNo ratings yet

- Aquel Micromundo PoéticoDocument8 pagesAquel Micromundo PoéticoNatalia WolfgangNo ratings yet

- Reassembling The FragmentsDocument24 pagesReassembling The FragmentsFrederic LefrancoisNo ratings yet

- Juxtaposing The Realistic and The Speculative Elements in Haruki Murakami's Kafka On The ShoreDocument4 pagesJuxtaposing The Realistic and The Speculative Elements in Haruki Murakami's Kafka On The ShoreIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Golden Chalice Good To House A God - Still Life in The RoadDocument27 pagesGolden Chalice Good To House A God - Still Life in The RoadsafiyaburnerNo ratings yet

- Example Essay Feb 2002Document4 pagesExample Essay Feb 2002Mandy LiNo ratings yet

- Desert PlaceDocument6 pagesDesert PlacedikaNo ratings yet

- Isle of IDocument18 pagesIsle of ITudor RomanNo ratings yet

- The Johns Hopkins University Press Theatre JournalDocument5 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University Press Theatre JournalSophie FelgentreuNo ratings yet

- Modelling From Well-Known Local and Foreign Poetry Writers: A. Examples of Symbolism in LiteratureDocument6 pagesModelling From Well-Known Local and Foreign Poetry Writers: A. Examples of Symbolism in LiteratureLoisBornillaNo ratings yet

- 2nd ReferenceDocument21 pages2nd ReferenceKellyNo ratings yet

- Symbolism in Frost's Poetry: Dr. Shyam Kumar ThakurDocument3 pagesSymbolism in Frost's Poetry: Dr. Shyam Kumar Thakurmonalisa.thesis2024No ratings yet

- Sample MLA PaperDocument8 pagesSample MLA PaperAllysonLee17281No ratings yet

- Waiting For The Barbarians by J. M. Coetzee, First Published in 1980 and Republished inDocument4 pagesWaiting For The Barbarians by J. M. Coetzee, First Published in 1980 and Republished indavid236635No ratings yet

- 6240-Besedilo Prispevka-15664-1-10-20171026Document16 pages6240-Besedilo Prispevka-15664-1-10-20171026Andra BaleaNo ratings yet

- Anti-Realism and The Pastoral ModeDocument8 pagesAnti-Realism and The Pastoral ModeLuke IsaacsonNo ratings yet

- Rogue Games Tabbloid - February 12, 2010 EditionDocument2 pagesRogue Games Tabbloid - February 12, 2010 EditionRogue GamesNo ratings yet

- wjec_a_level_hughes_plathDocument12 pageswjec_a_level_hughes_plathValeriaNo ratings yet

- 9: Spatial Perspectives in Alice Munro's "Passion": Giuseppina BottaDocument12 pages9: Spatial Perspectives in Alice Munro's "Passion": Giuseppina BottaenviNo ratings yet

- SS23 Catalog Copper Canyon PressDocument12 pagesSS23 Catalog Copper Canyon PresshoneromarNo ratings yet

- Metaphor and Metonymy in Joyce A Little CloudDocument10 pagesMetaphor and Metonymy in Joyce A Little CloudNeelam NepalNo ratings yet

- American Association of Teachers of French The French ReviewDocument9 pagesAmerican Association of Teachers of French The French ReviewahorrorizadaNo ratings yet

- Dialnet AgingMemoryAndIdentity 8259786Document10 pagesDialnet AgingMemoryAndIdentity 8259786Priyanka RoutNo ratings yet

- Baudelaires "Le Voyage"Document13 pagesBaudelaires "Le Voyage"Trifun StojoskiNo ratings yet

- “Who was the woman_”_ Feminine Space and the Shaping of Identity in The Sound and the FuryDocument15 pages“Who was the woman_”_ Feminine Space and the Shaping of Identity in The Sound and the FuryJosé Vilian MangueiraNo ratings yet

- Esslin Theatre of The AbsurdDocument14 pagesEsslin Theatre of The AbsurdEthan VerNo ratings yet

- Point of ViewDocument3 pagesPoint of ViewLung DănuţNo ratings yet

- Lawrence E. Bowling: College English, Vol. 12, No. 4. (Jan., 1951), Pp. 203-209Document8 pagesLawrence E. Bowling: College English, Vol. 12, No. 4. (Jan., 1951), Pp. 203-209Laura MinadeoNo ratings yet

- Learning Guide: EnglishDocument5 pagesLearning Guide: EnglishMary Kristine Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Fatum and Fortuna in Lucan's Bellum CivileDocument9 pagesFatum and Fortuna in Lucan's Bellum CivileElena OchoaNo ratings yet

- Absurdtheatre 1124873Document14 pagesAbsurdtheatre 1124873haydar severgeNo ratings yet

- Modelling From Well Known Fictions PDFDocument4 pagesModelling From Well Known Fictions PDFLoisBornilla100% (1)

- 10 30794-Pausbed 1259704-2987695Document9 pages10 30794-Pausbed 1259704-2987695Ahmet Gökhan BiçerNo ratings yet

- John Beverley, Soledad PrimeraDocument17 pagesJohn Beverley, Soledad PrimeraEdu J.GNo ratings yet

- Kara WalkerDocument29 pagesKara Walkerpapasmurf63No ratings yet

- Fox VoidDocument9 pagesFox VoidggrozsaNo ratings yet

- The Voyage of The Argonauts - Janet Ruth BaconDocument97 pagesThe Voyage of The Argonauts - Janet Ruth BaconFrederic LecutNo ratings yet

- Parody IslandDocument8 pagesParody IslandRaul A. BurneoNo ratings yet

- Sheldon W. Liebman - Robert Frost, RomanticDocument22 pagesSheldon W. Liebman - Robert Frost, RomanticPratyusha BhaskarNo ratings yet

- Lovecraft's Dream CycleDocument15 pagesLovecraft's Dream CycleScott RassbachNo ratings yet

- AURYLAITE, Kristina. Margaret Atwood's Alternative Spaces. Wilderness Tips and Death by Landscape.Document9 pagesAURYLAITE, Kristina. Margaret Atwood's Alternative Spaces. Wilderness Tips and Death by Landscape.GuilhermeCopatiNo ratings yet

- Great Gatsby Symbols ChartDocument3 pagesGreat Gatsby Symbols ChartWilliam ImhoffNo ratings yet

- Eisenstein TheTimeMachine 1976Document6 pagesEisenstein TheTimeMachine 1976Annu singhNo ratings yet

- Sartre on William Faulkner's Metaphysics of Time in The Sound and the Fury Justin SkirryDocument30 pagesSartre on William Faulkner's Metaphysics of Time in The Sound and the Fury Justin SkirryShadragon XxXNo ratings yet

- Alice Munro Narrative HistoricismDocument13 pagesAlice Munro Narrative HistoricismSimone Buffon ScuottoNo ratings yet

- Class and Comedy EssayDocument6 pagesClass and Comedy EssayEmma ShardlowNo ratings yet

- DAWSON, Joanna - 2009 - A Moon Without Metaphors - 65-75Document11 pagesDAWSON, Joanna - 2009 - A Moon Without Metaphors - 65-75dvm1010No ratings yet

- Death by Depiction: Absence in The Landscapes of The Group of Seven and in Margaret Atwood's Death by Landscape, Lara Lee MeintjesDocument12 pagesDeath by Depiction: Absence in The Landscapes of The Group of Seven and in Margaret Atwood's Death by Landscape, Lara Lee MeintjesLara MeintjesNo ratings yet

- Dream Analysis in Ancient MesopotamiaDocument12 pagesDream Analysis in Ancient Mesopotamiale_09876hotmailcomNo ratings yet

- Some Trick of The Moonlight Seduction and The Moving Image in Bram Stokers DraculaDocument25 pagesSome Trick of The Moonlight Seduction and The Moving Image in Bram Stokers DraculaabelNo ratings yet

- Simulated Environments: Successive Phases of The Image in Tarkovsky's SolarisDocument12 pagesSimulated Environments: Successive Phases of The Image in Tarkovsky's SolarisIvy RobertsNo ratings yet

- Structural Identification & Poc-1: Topic Page NoDocument35 pagesStructural Identification & Poc-1: Topic Page Nosiddansh100% (1)

- 5 25 17 Migraines PowerPointDocument40 pages5 25 17 Migraines PowerPointSaifi AlamNo ratings yet

- TSB-1139 8SC Wiring DiagramDocument2 pagesTSB-1139 8SC Wiring Diagramxavier marsNo ratings yet

- Data Sheet USB5 II 2019 05 ENDocument1 pageData Sheet USB5 II 2019 05 ENJanne LaineNo ratings yet

- Manual Epson L555Document92 pagesManual Epson L555Asesorias Académicas En CaliNo ratings yet

- Md. Rizwanur Rahman - CVDocument4 pagesMd. Rizwanur Rahman - CVHimelNo ratings yet

- James Coleman (October Files) by George BakerDocument226 pagesJames Coleman (October Files) by George Bakersaknjdasdjlk100% (1)

- Stages of SleepDocument2 pagesStages of SleepCamilia Hilmy FaidahNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitleddwky KrnwnNo ratings yet

- Yuxi CatalogueDocument16 pagesYuxi CatalogueSoltani AliNo ratings yet

- HDR10+ System Whitepaper: September 4, 2019 HDR10+ Technologies, LLCDocument14 pagesHDR10+ System Whitepaper: September 4, 2019 HDR10+ Technologies, LLCDragomir ConstantinNo ratings yet

- Schiavi Enc Met Page015Document1 pageSchiavi Enc Met Page015Adel AdelNo ratings yet

- Toro Homelite 3354-726Document8 pagesToro Homelite 3354-726Cameron ScottNo ratings yet

- Understanding Your Electricity Bill in PakistanDocument13 pagesUnderstanding Your Electricity Bill in PakistanGhayas Ud-din DarNo ratings yet

- Is-Cal01 Design Carbon Accounting On Site Rev.02Document6 pagesIs-Cal01 Design Carbon Accounting On Site Rev.02shoba9945No ratings yet

- Snag SummmariesDocument171 pagesSnag Summmarieslaltu adgiriNo ratings yet

- How To Keep Your Brain HealthyDocument3 pagesHow To Keep Your Brain HealthySyahidah IzzatiNo ratings yet

- Anthropological Thought Session by DR G. VivekanandaDocument277 pagesAnthropological Thought Session by DR G. Vivekanandahamtum7861No ratings yet

- 9701 s02 ErDocument14 pages9701 s02 ErHubbak KhanNo ratings yet

- Bristol Comp Catalog 4Document102 pagesBristol Comp Catalog 4Popica ClaudiuNo ratings yet

- EVM TechmaxDocument96 pagesEVM Techmaxnikhileshdhuri97No ratings yet

- Contoh Form Rko Obat PRB Per ApotekDocument19 pagesContoh Form Rko Obat PRB Per ApoteksaddamNo ratings yet

- Oil & Chemical Tanker Summer 7 - Prepurchase Survey Report - S&a 230098 PpsDocument62 pagesOil & Chemical Tanker Summer 7 - Prepurchase Survey Report - S&a 230098 Ppsp_k_sahuNo ratings yet

- SOM016 - Hook Release System For Life Boats. Norsafe TOR mk2.Document20 pagesSOM016 - Hook Release System For Life Boats. Norsafe TOR mk2.arfaoui salimNo ratings yet

- New WITTMANN Robots For Large and Small Injection Molding MachinesDocument4 pagesNew WITTMANN Robots For Large and Small Injection Molding MachinesMonark HunyNo ratings yet

- (12942) Sheet Chemical Bonding 4 Theory eDocument8 pages(12942) Sheet Chemical Bonding 4 Theory eAnurag SinghNo ratings yet