Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nejmoa 011699

Nejmoa 011699

Uploaded by

Adriano MeyerCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- AWS Vs Azure Vs Google Cloud - A Detailed Comparison of The Cloud Services Giants PDFDocument10 pagesAWS Vs Azure Vs Google Cloud - A Detailed Comparison of The Cloud Services Giants PDFSakthivel PNo ratings yet

- 04 Sci Pub MosquitoDocument64 pages04 Sci Pub Mosquitoraja_martaNo ratings yet

- Do Wrist Bands Impregnated With Botanical Extracts Assist in Repelling Mosquitoes?Document5 pagesDo Wrist Bands Impregnated With Botanical Extracts Assist in Repelling Mosquitoes?27051977No ratings yet

- RRL: Tomato Leaves Extract As Insect RepellantDocument7 pagesRRL: Tomato Leaves Extract As Insect RepellantDanica Bondoc83% (6)

- Recomendaciones Aep Sobre Alimentacio N Complementaria Nov2018 v3 FinalDocument6 pagesRecomendaciones Aep Sobre Alimentacio N Complementaria Nov2018 v3 FinalMatìas GamarraNo ratings yet

- New Mosquitocide Derived From Volcanic Rock ClohertyDocument8 pagesNew Mosquitocide Derived From Volcanic Rock ClohertyAboubakar SidickNo ratings yet

- Figure 2. Chinese Bell Flower Abutilon Indicum LinnDocument8 pagesFigure 2. Chinese Bell Flower Abutilon Indicum LinnJohnNo ratings yet

- Investigatory Project in PHYSICSDocument3 pagesInvestigatory Project in PHYSICSbarolajaymeljoy100% (4)

- Development of Melaleuca Oils As Effective Natural-Based Personal Insect RepellentsDocument9 pagesDevelopment of Melaleuca Oils As Effective Natural-Based Personal Insect RepellentsDianna Joy Reyes SorianoNo ratings yet

- Hussein2016 PesticidaDocument7 pagesHussein2016 PesticidaHelena Ribeiro SouzaNo ratings yet

- 16 - Entomo eDocument12 pages16 - Entomo eMitha Dan MithaNo ratings yet

- The Efficacy of Some Commercially Available InsectDocument5 pagesThe Efficacy of Some Commercially Available InsectHaitao GuanNo ratings yet

- Mason R PDFDocument11 pagesMason R PDFReynaldo Caballero QuirozNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Plant-Based Repellents Against Anopheles Mosquitoes: A Systematic ReviewDocument8 pagesEfficacy of Plant-Based Repellents Against Anopheles Mosquitoes: A Systematic ReviewSitti XairahNo ratings yet

- Deet & DebaDocument5 pagesDeet & DebaDeepak MadhraniNo ratings yet

- Antifungal Susceptibility Pattern Against Dermatophytic Strains Isolated From Humans in Anambra State, NigeriaDocument8 pagesAntifungal Susceptibility Pattern Against Dermatophytic Strains Isolated From Humans in Anambra State, NigeriaIJAERS JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Articulo Deet Consecuencias de Su UsoDocument7 pagesArticulo Deet Consecuencias de Su UsoMIGUEL ANGEL VANEGAS RODRIGUEZNo ratings yet

- Essential Oils of Melaleuca, Citrus, Cupressus, and Litsea For The Management of Infections Caused by Candida Species - A SysRevDocument18 pagesEssential Oils of Melaleuca, Citrus, Cupressus, and Litsea For The Management of Infections Caused by Candida Species - A SysRevDidi Nurhadi IllianNo ratings yet

- In Vitro Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of 5 AnDocument5 pagesIn Vitro Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of 5 AnWendy VargasNo ratings yet

- Mosquito Repellent Activity of Phytochemical ExtractsDocument6 pagesMosquito Repellent Activity of Phytochemical ExtractsYutaNo ratings yet

- TMP 5 DA1Document13 pagesTMP 5 DA1FrontiersNo ratings yet

- Insects 13 01077Document13 pagesInsects 13 01077japoru hanNo ratings yet

- Mosquito Repellent Property of Ylang YlangDocument9 pagesMosquito Repellent Property of Ylang Ylangaeno751No ratings yet

- B108598KDocument3 pagesB108598KRAJKAMKAMALNo ratings yet

- Vol17-N1-2 Efectividad de Repelentes Comerciales y Esencias Botánicas Contra LaDocument8 pagesVol17-N1-2 Efectividad de Repelentes Comerciales y Esencias Botánicas Contra Lafabritziomiguel4No ratings yet

- Review: Nanovaccines: Recent Developments in VaccinationDocument9 pagesReview: Nanovaccines: Recent Developments in VaccinationGina CubillasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 2 3Document9 pagesChapter 1 2 3Gio Nhel LachicaNo ratings yet

- PNAS 2008 Katritzky 7359 64Document6 pagesPNAS 2008 Katritzky 7359 64KevinMegoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 2019 Final DefenseDocument8 pagesChapter 1 2019 Final DefenseHidayaNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument7 pagesChapter IPhantom ThiefNo ratings yet

- 8ebc PDFDocument5 pages8ebc PDFFammy SajorgaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of The Most Commonly Used Mosquitoes Repellent in Households in Niameycity (Niger)Document10 pagesEffectiveness of The Most Commonly Used Mosquitoes Repellent in Households in Niameycity (Niger)IJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Natural Products Against Sand Fly Vectors of Leishmaniosis: A Systematic ReviewDocument15 pagesNatural Products Against Sand Fly Vectors of Leishmaniosis: A Systematic ReviewDerrick Scott FullerNo ratings yet

- Formulation and Evaluation of Home Made Poly HerbaDocument9 pagesFormulation and Evaluation of Home Made Poly Herbasajeel ur rahmanNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Mosquito RepellentsDocument11 pagesEffectiveness of Mosquito RepellentsZeth Lachica100% (1)

- 28 13v3i1 4 PDFDocument4 pages28 13v3i1 4 PDFariaNo ratings yet

- Citronella Oil: Its Properties and UsesDocument7 pagesCitronella Oil: Its Properties and UsesJemrei AlbertoNo ratings yet

- 3is Chap 1 5Document37 pages3is Chap 1 5yawa koNo ratings yet

- Potential Test of Ethanol Extract From Onion (Allium Cepa L) Leaves As A Repellent To Aedes AegyptiDocument11 pagesPotential Test of Ethanol Extract From Onion (Allium Cepa L) Leaves As A Repellent To Aedes AegyptiNeli OlivNo ratings yet

- Antibacterial Activity (P. Angulata) 2015.01 OPEMDocument10 pagesAntibacterial Activity (P. Angulata) 2015.01 OPEMoscarbio2009No ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Orange Peel As An Mosquito Repellent PDFDocument17 pagesThe Effectiveness of Orange Peel As An Mosquito Repellent PDFXander JaniolaNo ratings yet

- Probing Into The Edible Vaccines: Newer Paradigms, Scope and RelevanceDocument13 pagesProbing Into The Edible Vaccines: Newer Paradigms, Scope and Relevanceنوره نورNo ratings yet

- Roduction of Mosquito Repellent Using Orange PeelsDocument16 pagesRoduction of Mosquito Repellent Using Orange PeelsSamuel UdoemaNo ratings yet

- ThePrimaryMechanisms of Pesticide Action (MoA)Document11 pagesThePrimaryMechanisms of Pesticide Action (MoA)Catherine TangNo ratings yet

- Ivermectin: Enigmatic Multifaceted Wonder' Drug Continues To Surprise and Exceed ExpectationsDocument11 pagesIvermectin: Enigmatic Multifaceted Wonder' Drug Continues To Surprise and Exceed ExpectationsnemoNo ratings yet

- Antibacterial Activity of Two Common Garden WeedsDocument16 pagesAntibacterial Activity of Two Common Garden WeedsMay LacdaoNo ratings yet

- I R I V H D: Nsecticide Esistance in Nsect EctorsDocument22 pagesI R I V H D: Nsecticide Esistance in Nsect EctorsNemay AnggadewiNo ratings yet

- Bermuda Grass (Cynodon Dactylon) As An Alternative Antibacterial Agent Against Staphylococcus AureusDocument8 pagesBermuda Grass (Cynodon Dactylon) As An Alternative Antibacterial Agent Against Staphylococcus AureusIOER International Multidisciplinary Research Journal ( IIMRJ)No ratings yet

- Lecture Notes IPDMDocument82 pagesLecture Notes IPDMApoorva Ashu100% (1)

- 43874PDFDocument12 pages43874PDFFarm MagazineNo ratings yet

- 2 Acylamino 5 Nitro 1,3 Thiazoles PDFDocument8 pages2 Acylamino 5 Nitro 1,3 Thiazoles PDFJulianaRinconLopezNo ratings yet

- Madrid 2009Document4 pagesMadrid 2009Alexandre MatiasNo ratings yet

- Crespo2011 PDFDocument6 pagesCrespo2011 PDFDANIELA MALAGÓN MONTAÑONo ratings yet

- EUCALEM O Chapter 1 4 1 2 AutosavedDocument20 pagesEUCALEM O Chapter 1 4 1 2 AutosavedDiosario SubiateNo ratings yet

- Vaccination Against Coccidial Parasites. The Method of Choice?Document10 pagesVaccination Against Coccidial Parasites. The Method of Choice?Gopi MarappanNo ratings yet

- NeemDocument26 pagesNeemRafael Reyes RamirezNo ratings yet

- Minutes From The WINSA Meeting - Final 29.08.2023Document27 pagesMinutes From The WINSA Meeting - Final 29.08.2023JOSE FRANCISCO FLORES LOZANONo ratings yet

- Exploration of Phytochemicals Found in Terminalia Sp. and Their - 113129Document11 pagesExploration of Phytochemicals Found in Terminalia Sp. and Their - 113129M gozariNo ratings yet

- Modelo de CarrageninaDocument8 pagesModelo de CarrageninaSandra RiveraNo ratings yet

- Learning Action Cell Implementation Plan (Tle Department)Document4 pagesLearning Action Cell Implementation Plan (Tle Department)AlmaRoxanneFriginal-TevesNo ratings yet

- Tda 7419Document30 pagesTda 7419heviandriasNo ratings yet

- COOKERY 9 Q3.Mod1Document5 pagesCOOKERY 9 Q3.Mod1Jessel Mejia Onza100% (4)

- 2intro To LLMDDocument2 pages2intro To LLMDKristal ManriqueNo ratings yet

- Tesa-60150 MSDSDocument11 pagesTesa-60150 MSDSBalagopal U RNo ratings yet

- NO Memo No. 21 S. 2018 Adherence To Training Policy PDFDocument10 pagesNO Memo No. 21 S. 2018 Adherence To Training Policy PDFKemberly Semaña PentonNo ratings yet

- CHEMEXCILDocument28 pagesCHEMEXCILAmal JerryNo ratings yet

- Manual Tesa Portable ProgrammerDocument39 pagesManual Tesa Portable ProgrammeritmNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions Grade 12 ModuleDocument25 pagesContemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions Grade 12 ModuleFaye Corazon GaurinoNo ratings yet

- Question 5 (Right Form of Verbs)Document4 pagesQuestion 5 (Right Form of Verbs)E TreatmentNo ratings yet

- Activity-2-White. Gadfrey Jahn PDocument2 pagesActivity-2-White. Gadfrey Jahn PGadfrey jahn WhiteNo ratings yet

- Coast Artillery Journal - Oct 1946Document84 pagesCoast Artillery Journal - Oct 1946CAP History LibraryNo ratings yet

- Clear Codes List-NokiaDocument8 pagesClear Codes List-NokiaocuavasNo ratings yet

- Project MarketingDocument88 pagesProject MarketingAnkita DhimanNo ratings yet

- Interest InventoriesDocument7 pagesInterest Inventoriesandrewwilliampalileo@yahoocomNo ratings yet

- Irda Jun10Document96 pagesIrda Jun10ManiNo ratings yet

- BenfordDocument9 pagesBenfordAlex MireniucNo ratings yet

- MTA uniVAL Technical Data Sheet v00Document1 pageMTA uniVAL Technical Data Sheet v00muhammetNo ratings yet

- Soal BAHASA INGGRIS XIIDocument5 pagesSoal BAHASA INGGRIS XIIZiyad Frnandaa SyamsNo ratings yet

- 3987 SDS (GHS) - I-ChemDocument4 pages3987 SDS (GHS) - I-ChemAmirHakimRusliNo ratings yet

- Versatile, Efficient and Easy-To-Use Visual Imu-Rtk: Surveying & EngineeringDocument4 pagesVersatile, Efficient and Easy-To-Use Visual Imu-Rtk: Surveying & EngineeringMohanad MHPSNo ratings yet

- wst03 01 Que 20220611 1Document28 pageswst03 01 Que 20220611 1Rehan RagibNo ratings yet

- Pioneering Urban Practices in Transition SpacesDocument10 pagesPioneering Urban Practices in Transition SpacesFloorin OlariuNo ratings yet

- Lab Manual (Text)Document41 pagesLab Manual (Text)tuan nguyenNo ratings yet

- Turbine Gas G.T.G. 1Document17 pagesTurbine Gas G.T.G. 1wilsonNo ratings yet

- Denman - On FortificationDocument17 pagesDenman - On FortificationkontarexNo ratings yet

- Tabel PeriodikDocument2 pagesTabel PeriodikNisrina KalyaNo ratings yet

- Global Wine IndustryDocument134 pagesGlobal Wine IndustrySaifur Rahman Steve100% (2)

- Weebly Homework Article Review Standard 2Document11 pagesWeebly Homework Article Review Standard 2api-289106854No ratings yet

Nejmoa 011699

Nejmoa 011699

Uploaded by

Adriano MeyerOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Nejmoa 011699

Nejmoa 011699

Uploaded by

Adriano MeyerCopyright:

Available Formats

INSEC T REPELLENTS A ND MOS QUITO B ITES

COMPARATIVE EFFICACY OF INSECT REPELLENTS AGAINST MOSQUITO BITES

MARK S. FRADIN, M.D., AND JOHN F. DAY, PH.D.

ABSTRACT breaks of eastern equine encephalitis, western equine

Background The worldwide threat of arthropod- encephalitis, St. Louis encephalitis, and La Crosse

transmitted diseases, with their associated morbidity encephalitis.4,5 In the fall of 1999, West Nile virus,

and mortality, underscores the need for effective in- transmitted by mosquitoes, was detected for the first

sect repellents. Multiple chemical, botanical, and “al- time in the Western Hemisphere. In the New York

ternative” repellent products are marketed to consum- City area, 62 persons infected with West Nile virus

ers. We sought to determine which products available were hospitalized, and 7 persons died.6-8 The Centers

in the United States provide reliable and prolonged for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that

complete protection from mosquito bites.

more than 2000 persons were infected with West Nile

Methods We conducted studies involving 15 volun-

teers to test the relative efficacy of seven botanical

virus in the year 2000.9 The virus has now been de-

insect repellents; four products containing N,N-diethyl- tected in 27 states, and it is anticipated that it will

m-toluamide, now called N,N-diethyl-3-methylben- continue to spread unabated across the United States

zamide (DEET); a repellent containing IR3535 (ethyl during the next few years.9,10

butylacetylaminopropionate); three repellent-impreg- Protection from arthropod bites is best achieved

nated wristbands; and a moisturizer that is commonly by avoiding infested habitats, wearing protective cloth-

claimed to have repellent effects. These products were ing, and using insect repellent.11,12 In many circum-

tested in a controlled laboratory environment in which stances, applying repellent to the skin may be the only

the species of the mosquitoes, their age, their degree feasible way to protect against insect bites. Given that

of hunger, the humidity, the temperature, and the a single bite from an infected arthropod can result in

light–dark cycle were all kept constant.

transmission of disease, it is important to know which

Results DEET-based products provided complete

protection for the longest duration. Higher concentra- repellent products can be relied on to provide predict-

tions of DEET provided longer-lasting protection. A able and prolonged protection from insect bites. Com-

formulation containing 23.8 percent DEET had a mean mercially available insect repellents can be divided

complete-protection time of 301.5 minutes. A soybean- into two categories — synthetic chemicals and plant-

oil–based repellent protected against mosquito bites derived essential oils. The best-known chemical insect

for an average of 94.6 minutes. The IR3535-based re- repellent is N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide, now called

pellent protected for an average of 22.9 minutes. All N,N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide (DEET). Many con-

other botanical repellents we tested provided protec- sumers, reluctant to apply DEET to their skin, delib-

tion for a mean duration of less than 20 minutes. Re- erately seek out other repellent products. We com-

pellent-impregnated wristbands offered no protection.

pared the efficacy of readily available alternatives to

Conclusions Currently available non-DEET repel- DEET-based repellents in a controlled laboratory en-

lents do not provide protection for durations similar

to those of DEET-based repellents and cannot be relied vironment.

on to provide prolonged protection in environments METHODS

where mosquito-borne diseases are a substantial

threat. (N Engl J Med 2002;347:13-8.) Product Selection

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. In January 2001, we purchased a total of 16 products for testing,

choosing repellents with national, rather than local, distribution

(Table 1). Seven widely available botanical repellents were included

in the study. Multiple concentrations and formulations of DEET

are readily available. We chose and tested three DEET-based repel-

lents (ranging from 4.75 to 23.8 percent DEET) that we believe

I

NSECT-TRANSMITTED disease remains a ma- represented the range of commonly purchased repellents in the

jor source of illness and death worldwide. Mos- United States. We also tested a controlled-release 20 percent DEET

formulation to determine whether it had a longer duration of action.

quitoes alone transmit disease to more than 700 The only synthetic repellent containing IR3535 (ethyl butylacetyl-

million persons annually.1 Malaria kills 3 mil- aminopropionate) that is available in the United States and three

lion persons each year, including 1 child every 30

seconds.2,3 Although insect-borne diseases currently

represent a greater health problem in tropical and From Chapel Hill Dermatology, Chapel Hill, N.C. (M.S.F.); and the

subtropical climates, no part of the world is immune Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory, University of Florida, Vero

Beach (J.F.D.). Address reprint requests to Dr. Fradin at Chapel Hill Der-

to their risks. In the United States, arboviruses trans- matology, 891 Willow Dr., Suite 1, Chapel Hill, NC 27514, or at

mitted by mosquitoes continue to cause sporadic out- mark_fradin@med.unc.edu.

N Engl J Med, Vol. 347, No. 1 · July 4, 2002 · www.nejm.org · 13

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on February 4, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The Ne w E n g l a nd Jo u r n a l o f Me d ic i ne

wristbands impregnated with either DEET or citronella were also arm was reinserted for 1 full minute every 15 minutes, until the

tested. Finally, we tested the efficacy of a proprietary moisturizer first bite occurred. On the basis of this initial complete-protection

that is commonly believed to have repellent effects. time, the subject’s next two tests of that particular repellent were

conducted as follows: if the repellent had initially worked for less

Testing Methods than 20 minutes, the subject placed his or her arm in the cage for

The duration of protection provided by each product was tested 1 minute every 5 minutes; if the repellent had initially worked for

by means of arm-in-cage studies, in which volunteers insert their 20 minutes to 4 hours, the subject placed his or her arm in the

repellent-treated arms into a cage with a fixed number of unfed cage for 1 minute every 15 minutes; and if the repellent had initially

mosquitoes, and the elapsed time to the first bite is recorded. Test- worked for more than 4 hours, the subject placed his or her arm

ing of repellents is usually conducted either in a laboratory or at in the cage for 1 minute every hour (up to 4 hours). If a repellent

outdoor field sites.14 Conducting such studies indoors makes it was still working after 4 hours, then the subject continued to

possible to reduce potential confounding variables, such as wind place his or her arm in the cage every 15 minutes thereafter, until

speed, temperature, humidity, density of the mosquito popula- the first bite occurred. If at any point during testing, subjects

tion, the level of the mosquitoes’ hunger, and the species of the noted mosquitoes landing but not biting (a behavior that typical-

mosquitoes, that can make it difficult to interpret comparisons ly occurs when the efficacy of a repellent begins to wane), then

among products made in outdoor-field trials. We conducted our the intervals between insertions were decreased to five minutes.

tests with a low density of mosquitoes per cage rather than a high Discretionary funds from the State of Florida were used to sup-

density (some studies use more than 250 mosquitoes per cage) port this study. We received no financial support from industry,

because the low-density environment more accurately reflects the including the manufacturers whose products were tested in the

typical biting pressures that are encountered during most out- study. Data analysis was performed within the Florida Medical

door activities. Entomology Laboratory at the University of Florida, without in-

For each test, 10 disease-free, laboratory-reared Aedes aegypti put from any outside sources.

female mosquitoes that were between 7 and 24 days old were placed

Statistical Analysis

into separate laboratory cages measuring 30 cm by 22 cm by 22 cm.

A batch of 10 mosquitoes that had not been exposed to the repel- Two-way analysis of variance (involving two factors, subject

lent being tested was used for each arm insertion. Mosquitoes were and repellent) followed by Tukey’s tests13 was used to compare

provided with a constant supply of 5 percent sucrose solution. the mean complete-protection time for the 16 tested repellents.

Cages were placed in a walk-in incubator measuring 2.2 m by 2.2 m All P values are two-sided; a P value of less than 0.05 was con-

by 2.2 m, in which the temperature was maintained at 24 to 32°C, sidered to indicate statistical significance.

the relative humidity at 60 to 70 percent, and the light–dark cycle

at 12 hours of light followed by 12 hours of darkness. RESULTS

Fifteen volunteers (5 men and 10 women) were recruited from

the staff of the Medical Entomology Laboratory at the University

Of the products tested, those containing DEET

of Florida. The study was reviewed and approved by the institu- provided the longest-lasting protection (Table 1). The

tional review board of the University of Florida, and subjects gave complete-protection times of DEET-based repel-

written informed consent before participating. lents correlated positively with the concentration of

As repellents were purchased, they were labeled sequentially from DEET in the repellent. The formulation containing

1 to 16. A random-number generator was then used to determine

the order in which the products would be tested on each subject. 4.75 percent DEET provided an average of 88.4 min-

A total of 720 individual tests were conducted, with each repel- utes of complete protection; the formulation contain-

lent being tested three times on each subject. Most subjects only ing 23.8 percent DEET protected for an average of

completed one test per day. The average time to completion of 301.5 minutes. There was a statistically significant dif-

all three tests was 10.2 days. In the case of repellents that were

identified as very short-acting in the initial test, subjects were per-

ference in complete-protection time between each

mitted to conduct all three tests of the repellent in a single day, DEET-based repellent and the product with the next

washing the skin with an unscented soap before each application higher concentration of DEET (P<0.001 for all com-

of the repellent. Subjects did not test more than one repellent parisons). The controlled-release formulation we test-

product on a single day. No information on the likely duration of ed did not prolong the duration of action of DEET.

action of each repellent was provided to subjects before they be-

gan their tests. The alcohol-based product containing 23.8 percent

Before each test, the readiness of the mosquitoes to bite was DEET protected significantly longer than the con-

confirmed by having subjects insert their untreated forearm into trolled-release formulation containing 20 percent

the test cage. Once subjects observed five mosquito landings on DEET (P<0.001).

the untreated arm, they removed their arm from the cage and ap-

plied the repellent being tested from the elbow to the fingertips,

No non-DEET repellent fully evaluated in this study

following the instructions on the product’s label. After the appli- was able to provide protection that lasted more than

cation of the repellent, subjects were instructed not to rub, touch, 1.5 hours. Only the soybean-oil–based repellent was

or wet the treated arm. Repellent-impregnated wristbands were able to provide protection for a period similar to that

worn on the wrist of the arm being inserted into the cage. Sub- of the lowest-concentration DEET product we tested

jects were provided with a standardized log sheet to ensure accu-

rate documentation of the duration of exposure and the time of (94.6 and 88.4 minutes, respectively).

the first bite. The elapsed time to the first bite was then calculated The IR3535-based repellent protected against mos-

and recorded as the “complete-protection time” for that subject quito bites for an average of 22.9 minutes. The cit-

in that particular test. ronella-based repellents we tested protected for 20

Subjects were asked to follow the testing protocol shown in

Figure 1. Subjects conducted their first test of each repellent by

minutes or less. There was no significant difference in

inserting the treated arm into a test cage for one full minute every protection time between the slow-release formulation

five minutes. If they were not bitten within 20 minutes, then the containing 12 percent citronella and the formulation

14 · N Engl J Med, Vol. 347, No. 1 · July 4, 2002 · www.nejm.org

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on February 4, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

INSEC T REPELLENTS A ND MOS QUITO B ITES

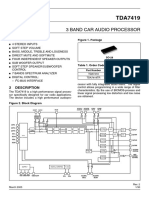

Initial Test 2nd and 3rd Tests

(performed by each (performed by each

subject for each repellent) subject for each repellent)

Apply repellent

Insert arm for 1 min every

Insert arm in cage

If bitten 5 min, recording time to

for 1 min If <20 min

first bite for each test

If not bitten

Record Insert arm for 1 min every

Insert arm for elapsed If 20 min to 4 hr 15 min, recording time to

1 min every 5 min, If bitten time until first bite for each test

up to 20 min first bite

If not bitten

Insert arm for 1 min every hr,

Insert arm for for 4 hr, then 1 min every

If >4 hr

1 min every 15 min, 15 min thereafter, recording

until first bite time to first bite for each test

Figure 1. Study Design.

If at any time during testing, mosquitoes were seen to land on the skin but not bite (a sign of imminent failure of the

repellent), then the interval between insertions was decreased to five minutes until the first bite was confirmed.

containing 5 percent citronella (P=0.07) or the two risk of overestimation of complete-protection times

formulations containing 10 percent citronella (P=0.16 would affect the repellents that were tested with

and P=0.80). The repellent containing only 0.05 once-hourly insertions into the cage. According to

percent citronella provided less protection than the our protocol, however, hourly insertions were only

Skin-So-Soft mineral-oil–based moisturizer (Avon) used by subjects who found that a repellent initially

(P<0.001). Repellent-impregnated wristbands, con- protected them for more than four hours. Only the

taining either 9.5 percent DEET or 25 percent cit- two highest-concentration DEET-based repellents

ronella (by weight), protected the wearer for only 12 in our study (20 percent and 23.8 percent DEET)

to 18 seconds, on average. qualified for once-hourly insertions by some of the

In arm-in-cage studies, testing must be conducted subjects, and the range of protection these repellents

with insertions at limited intervals, with a new batch afforded (180 to 360 minutes) is consistent with pre-

of mosquitoes for each test, because continuous ex- viously published reports of the efficacy of DEET.15,16

posure may cause mosquitoes to fatigue or may in- Any rounding errors resulting from the intervals be-

duce prolonged blockage of their antennal chemore- tween insertions into the cage would also tend to

ceptors, both of which will prevent further biting. overestimate the efficacy of the other repellents we

Conducting tests of a repellent in which the arm is tested, and 11 of the 12 non-DEET products still

inserted into the cage at fixed intervals, however, has had mean complete-protection times of less than 23

some obvious limitations. A repellent might stop minutes.

working between the removal of the arm and the After the original studies for this article were com-

subsequent insertion, but the failure would not be pleted, a new botanical repellent was introduced in

detected until the next scheduled insertion, causing the United States. The repellent contains oil of eu-

an inflated measure of the duration of protection calyptus and is marketed under two names: Repel

provided by that repellent. In our study, the greatest Lemon Eucalyptus Insect Repellent (WPC Brands)

N Engl J Med, Vol. 347, No. 1 · July 4, 2002 · www.nejm.org · 15

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on February 4, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The Ne w E n g l a nd Jo u r n a l o f Me d ic i ne

TABLE 1. PROTECTION TIMES OF INSECT REPELLENTS.*

ACTIVE INGREDIENT CATEGORY OF

PRODUCT AND CONCENTRATION COMPLETE-PROTECTION TIME PROTECTION†

MEAN RANGE

min

OFF! Deep Woods (SC Johnson) DEET, 23.8% 301.5±37.6 200–360 A

Sawyer Controlled Release (Sawyer) DEET, 20% 234.4±31.8 180–325 B

OFF! Skintastic (SC Johnson) DEET, 6.65% 112.4±20.3 90–170 C

Bite Blocker for Kids (HOMS) Soybean oil, 2% 94.6±42.0 16–195 D

OFF! Skintastic for Kids (SC Johnson) DEET, 4.75% 88.4±21.4 45–120 D

Skin-So-Soft Bug Guard Plus (Avon) IR3535, 7.5% 22.9±11.2 10–60 E‡

Natrapel (Tender) Citronella, 10% 19.7±10.6 7–60 E‡

Herbal Armor (microencapsulated) Citronella, 12%; peppermint 18.9±13.3 1–55 E§

(All Terrain) oil, 2.5%; cedar oil, 2%;

lemongrass oil, 1%; gera-

nium oil, 0.05%

Green Ban for People (Mulgum Hollow Citronella, 10%; peppermint 14.0±11.3 1–45 E

Farm) oil, 2%

Buzz Away (Quantum) Citronella, 5% 13.5±7.5 5–30 E

Skin-So-Soft Bug Guard (Avon) Citronella, 0.1% 10.3±7.9 1–30 E

Skin-So-Soft Bath Oil (Avon) Uncertain¶ 9.6±8.8 1–30 E

Skin-So-Soft Moisturizing Suncare (Avon) Citronella, 0.05% 2.8±3.4 1–15 F

Gone Original Wristband (Solar DEET, 9.5% 0.3±0.2 0.17–1.33 G

Gloooow)

Repello Wristband (Repello Products) DEET, 9.5% 0.2±0.08 0.17–0.63 H

Gone Plus Repelling Wristband (Solar Citronella, 25% 0.2±0.09 0.17–0.48 H

Gloooow)

*Plus–minus values are the means ±SD of the times to the first bite in the tests of all 15 subjects. DEET denotes

N,N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide (formerly known as N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide), HOMS Home Operations and Manage-

ment Systems, and IR3535 ethyl butylacetylaminopropionate.

†The mean complete-protection time of each repellent was significantly different (P<0.05 by analysis of variance and

Tukey’s tests13) from those of all repellents in different categories of protection (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H).

‡The complete-protection time also differed significantly from those of Buzz Away, Skin-So-Soft Bug Guard, and Skin-

So-Soft Bath Oil.

§The complete-protection time also differed significantly from those of Skin-So-Soft Bug Guard and Skin-So-Soft

Bath Oil.

¶This product contains mineral oil, isopropyl palmitate, dicapryl adipate, fragrance, dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate, bu-

tylated hydroxytoluene, and carrot oil.

and Fite Bite Plant-Based Insect Repellent (Travel either synthetic chemicals or are derived from plants.

Medicine). We evaluated this type of repellent using The most widely marketed chemical-based insect re-

the same testing methods in six subjects (five men and pellent is DEET, which has been used worldwide since

one woman). In one subject, a localized cutaneous re- 1957. DEET is a broad-spectrum repellent that is ef-

action developed after the first test, and the subject fective against many species of mosquitoes, biting flies,

discontinued the study. All other subjects completed chiggers, fleas, and ticks.17 The protection provided

three tests each of the repellent. The repellent had a by DEET is proportional to the logarithm of the dose;

mean (±SD) complete-protection time of 120.1±44.8 higher concentrations of DEET provide longer-lasting

minutes, with a range of 60 to 217 minutes. protection, but the duration of action tends to plateau

at a concentration of about 50 percent.18 Most com-

DISCUSSION mercially available formulations now contain 40 per-

Protection against arthropod bites is best achieved cent DEET or less, and the higher concentrations are

by avoiding infested habitats, wearing protective cloth- most appropriate to use under circumstances in which

ing, and applying insect repellent.11,12 The insect re- the biting pressures are intense, the risk of arthropod-

pellents that are currently available to consumers are transmitted disease is great, or environmental condi-

16 · N Engl J Med, Vol. 347, No. 1 · July 4, 2002 · www.nejm.org

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on February 4, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

INSEC T REPELLENTS A ND MOS QUITO B ITES

tions promote the rapid loss of repellent from the age, sex, level of activity, and biochemical attractive-

surface of the skin.19 In our study, a formulation con- ness to biting arthropods; and the ambient temper-

taining 23.8 percent DEET provided an average of ature, humidity, and wind speed.31-34 As a result, a

five hours of complete protection against A. aegypti given repellent will not protect all users equally. Ex-

bites after a single application. Depending on the for- amination of the ranges of complete-protection times

mulation and concentration tested, DEET-based re- in Table 1 shows variation in the ability of each repel-

pellents have been shown in other studies to provide lent to protect different subjects. Thus, these times

complete protection against arthropod bites for as should be taken not as absolute values but, rather, as

long as 12 hours, even under harsh climatic condi- an indication of the relative effectiveness of the tested

tions.20,21 repellent products.

The most recent addition to the synthetic insect Our study shows that only products containing

repellents on the market in the United States is DEET offer long-lasting protection after a single ap-

IR3535,22 which is classified by the Environmental plication. Certain plant-derived repellents may pro-

Protection Agency as a biopesticide because of its vide short-lived efficacy, which may be sufficient when

structural similarity to the amino acid alanine. This arthropod bites are primarily a nuisance. Frequent re-

repellent has been used in Europe for more than 20 application of these repellents would partially com-

years and was approved for use in the United States pensate for their short duration of action. However,

in 1999. In our tests, this repellent fared poorly, yield- when one is traveling to an area with prevalent mos-

ing a mean complete-protection time that was one quito-borne disease that could be transmitted through

quarter that of the lowest-concentration DEET prod- a single bite, the use of non-DEET repellents would

uct we tested (22.9 vs. 88.4 minutes). seem to be ill-advised. Given our findings, we cannot

Skin-So-Soft Bath Oil, which consumers commonly recommend the use of any currently available non-

claim has a repellent effect on insects, provided only DEET repellent to provide complete protection from

a mean of 9.6 minutes of protection against aedes bites arthropod bites for any sustained outdoor activity.

in our study. This extremely limited repellent effect Although this study shows that DEET-based prod-

has previously been documented in other studies.15 ucts can be depended on for long-lasting repellent

Thousands of plants have been tested as potential effect, they are not perfect repellents. DEET may be

botanical sources of insect repellent.23-25 Most plant- washed off by perspiration or rain, and its efficacy

based insect repellents currently on the market contain decreases dramatically with rising outdoor tempera-

essential oils from one or more of the following plants: tures.19,30,34 DEET is also a plasticizer, capable of dis-

citronella, cedar, eucalyptus, peppermint, lemongrass, solving watch crystals, the frames of glasses, and cer-

geranium, and soybean. Of the products we tested, tain synthetic fabrics.

the soybean-oil–based repellent was able to protect Despite the substantial attention paid by the lay

from mosquito bites for about 1.5 hours. All other press every year to the safety of DEET, this repellent

botanical repellents that we tested in our initial stud- has been subjected to more scientific and toxicologic

ies, regardless of their active ingredients and formu- scrutiny than any other repellent substance. The ex-

lations, gave very short-lived protection, ranging from tensive accumulated toxicologic data on DEET have

a mean of about 3 to 20 minutes. Preliminary studies been reviewed elsewhere.17,35-39 DEET has a remark-

suggest that the oil-of-eucalyptus products will confer able safety profile after 40 years of use and nearly 8 bil-

longer-lasting protection than other available plant- lion human applications.35 Fewer than 50 cases of

based repellents. serious toxic effects have been documented in the

Most alternatives to topically applied repellents have medical literature since 1960, and three quarters of

proved to be ineffective. No ingested compound, in- them resolved without sequelae.35,37 Many of these

cluding garlic and thiamine (vitamin B1), has been cases of toxic effects involved long-term, heavy, fre-

found to be capable of repelling biting arthropods.26-28 quent, or whole-body application of DEET. No cor-

Small, wearable devices that emit sounds that are pur- relation has been found between the concentration

ported to be abhorrent to biting mosquitoes have of DEET used and the risk of toxic effects. As part

also been proved to be ineffective.29 In our study, of the Reregistration Eligibility Decision on DEET,

wristbands impregnated with either DEET or citronel- released in 1998, the Environmental Protection Agen-

la similarly provided no protection from bites, con- cy reviewed the accumulated data on the toxicity of

sistent with the known inability of repellents to pro- DEET and concluded that “normal use of DEET

tect beyond 4 cm from the site of application.30 does not present a health concern to the general U.S.

Multiple factors play a part in determining how ef- population.”40 When applied with common sense,

fective any repellent will be; these factors include the DEET-based repellents can be expected to provide a

species of the biting organisms and the density of safe as well as a long-lasting repellent effect. Until a

organisms in the immediate surroundings; the user’s better repellent becomes available, DEET-based re-

N Engl J Med, Vol. 347, No. 1 · July 4, 2002 · www.nejm.org · 17

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on February 4, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The Ne w E n g l a nd Jo u r n a l o f Me d ic i ne

pellents remain the gold standard of protection un- 21. Idem. Controlled release repellent formulations on human volunteers

under three climatic regimens. J Am Mosq Control Assoc 1991;7:490-3.

der circumstances in which it is crucial to be protected 22. Biopesticide technical document: 3-[N-butyl-N-acetyl]-aminopropi-

against arthropod bites that might transmit disease. onic acid, ethyl ester. Washington, D.C.: Environmental Protection Agen-

cy, 1999. (Accessed May 3, 2002, at http://www.epa.gov/pesticides/

REFERENCES biopesticides/factsheets/fs113509t.htm.)

23. Quarles W. Botanical mosquito repellents. Common Sense Pest Con-

1. Taubes G. A mosquito bites back. New York Times Magazine. August trol 1996;12(4):12-9.

24, 1997:40-6. 24. King WV. Chemicals evaluated as insecticides and repellents at Orlan-

2. Shell ER. Resurgence of a deadly disease. Atlantic Monthly. August do, Fla. Agriculture Handbook no. 69. Washington, D.C.: Entomology

1997:45-60. Research Branch, Department of Agriculture, 1954.

3. Malaria. Fact sheet. No. 94. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1999. 25. Tawatsin A, Wratten SD, Scott RR, Thavara U, Techadamrongsin Y.

(Accessed May 3, 2002, at http://www.who.int/inf-fs/en/fact094.html.) Repellency of volatile oils from plants against three mosquito vectors.

4. McHugh CP. Arthropods: vectors of disease agents. Lab Med 1994;25: J Vector Ecol 2001;26:76-82.

429-37. 26. Khan AA, Maibach HI, Strauss WG, Fenley WR. Vitamin B1 is not a

5. Goddard J. Physician’s guide to arthropods of medical importance. 3rd systemic mosquito repellent in man. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc

ed. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press, 2000. 1969;55:99-102.

6. Guidelines for surveillance, prevention, and control of West Nile virus 27. Strauss WG, Maibach HI, Khan AA. Drugs and disease as mosquito

infection — United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2000;49:25- repellents in man. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1968;17:461-4.

8. 28. Food and Drug Administration. Drug products containing active in-

7. Human West Nile virus surveillance — Connecticut, New Jersey, and gredients offered over-the-counter (OTC) for oral use as insect repellents.

New York, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50:265-8. Fed Regist 1983;48:26987.

8. Nash D, Mostashari F, Fine A, et al. The outbreak of West Nile virus 29. Coro F, Suarez S. Review and history of electronic mosquito repellers.

infection in the New York City area in 1999. N Engl J Med 2001;344: Wing Beats 2000;11:(2)6-7, 30-2.

1807-14. 30. Maibach HI, Akers WA, Johnson HL, Khan AA, Skinner WA. Insects:

9. Update: West Nile virus activity — eastern United States, 2000. topical insect repellents. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1974;16:970-3.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2000;49:1044-7. 31. Golenda CF, Solberg VB, Burge R, Gambel JM, Wirtz RA. Gender-

10. Environmental Risk Analysis Program. What’s going on with the West related efficacy difference to an extended duration formulation of topical

Nile virus. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Center for the Environment, N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET). Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999;60:654-7.

2001. (Accessed May 3, 2002, at http://www.cfe.cornell.edu/risk/WNV/ 32. Maibach HI, Skinner WA, Strauss WG, Khan AA. Factors that attract

index.html.) and repel mosquitoes in human skin. JAMA 1966;196:263-6.

11. Curtis CF. Personal protection methods against vectors of disease. Rev 33. Muirhead-Thomson RC. The distribution of anopheline mosquito

Med Vet Entomol 1992;80:543-53. bites among different age groups: a new factor in malaria epidemiology.

12. Fradin MS. Protection from blood-feeding arthropods. In: Auerbach BMJ 1951;1:1114-7.

PS, ed. Wilderness medicine. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 2001:754-68. 34. Fradin MS. Insect repellents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive

13. Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ. Biometry, the principles and practice of statistics dermatologic drug therapy. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 2001:717-34.

in biological research. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman, 1981. 35. Idem. Mosquitoes and mosquito repellents: a clinician’s guide. Ann In-

14. Schreck CE. Techniques for the evaluation of insect repellents: a crit- tern Med 1998;128:931-40.

ical review. Annu Rev Entomol 1977;22:101-19. 36. Selim S, Hartnagel RE Jr, Osimitz TG, Gabriel KL, Schoenig GP. Ab-

15. Chou JT, Rossignol PA, Ayres JW. Evaluation of commercial insect re- sorption, metabolism, and excretion of N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide follow-

pellents on human skin against Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med ing dermal application to human volunteers. Fundam Appl Toxicol 1995;

Entomol 1997;34:624-30. 25:95-100.

16. Buzz off ! Consumer Reports. June 2000:14-7. 37. Osimitz TG, Grothaus RH. The present safety assessment of deet.

17. Office of Pesticides and Toxic Substances, Special Pesticide Review Di- J Am Mosq Control Assoc 1995;11:274-8.

vision. N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) pesticide registration standard. 38. Veltri JC, Osimitz TG, Bradford DC, Page BC. Retrospective analysis

Washington, D.C.: Environmental Protection Agency, 1980. (EPA 540/ of calls to poison control centers resulting from exposure to the insect re-

RS-81-004.) pellent N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) from 1985-1989. J Toxicol Clin

18. Buescher MD, Rutledge LC, Wirtz RA, Nelson JH. The dose-persist- Toxicol 1994;32:1-16.

ence relationship of DEET against Aedes aegypti. Mosq News 1983;43: 39. Goodyer L, Behrens RH. The safety and toxicity of insect repellents.

364-6. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998;59:323-4.

19. Maibach HI, Khan AA, Akers WA. Use of insect repellents for maxi- 40. Office of Pesticide Programs, Prevention, Pesticides and Toxic Sub-

mum efficacy. Arch Dermatol 1974;109:32-5. stances. Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED): DEET. Washington,

20. Gupta RK, Rutledge LC. Laboratory evaluation of controlled-release D.C.: Environmental Protection Agency, 1998. (EPA 738-R-98-010.)

repellent formulations on human volunteers under three climatic regimens.

J Am Mosq Control Assoc 1989;5:52-5. Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society.

18 · N Engl J Med, Vol. 347, No. 1 · July 4, 2002 · www.nejm.org

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on February 4, 2016. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2002 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- AWS Vs Azure Vs Google Cloud - A Detailed Comparison of The Cloud Services Giants PDFDocument10 pagesAWS Vs Azure Vs Google Cloud - A Detailed Comparison of The Cloud Services Giants PDFSakthivel PNo ratings yet

- 04 Sci Pub MosquitoDocument64 pages04 Sci Pub Mosquitoraja_martaNo ratings yet

- Do Wrist Bands Impregnated With Botanical Extracts Assist in Repelling Mosquitoes?Document5 pagesDo Wrist Bands Impregnated With Botanical Extracts Assist in Repelling Mosquitoes?27051977No ratings yet

- RRL: Tomato Leaves Extract As Insect RepellantDocument7 pagesRRL: Tomato Leaves Extract As Insect RepellantDanica Bondoc83% (6)

- Recomendaciones Aep Sobre Alimentacio N Complementaria Nov2018 v3 FinalDocument6 pagesRecomendaciones Aep Sobre Alimentacio N Complementaria Nov2018 v3 FinalMatìas GamarraNo ratings yet

- New Mosquitocide Derived From Volcanic Rock ClohertyDocument8 pagesNew Mosquitocide Derived From Volcanic Rock ClohertyAboubakar SidickNo ratings yet

- Figure 2. Chinese Bell Flower Abutilon Indicum LinnDocument8 pagesFigure 2. Chinese Bell Flower Abutilon Indicum LinnJohnNo ratings yet

- Investigatory Project in PHYSICSDocument3 pagesInvestigatory Project in PHYSICSbarolajaymeljoy100% (4)

- Development of Melaleuca Oils As Effective Natural-Based Personal Insect RepellentsDocument9 pagesDevelopment of Melaleuca Oils As Effective Natural-Based Personal Insect RepellentsDianna Joy Reyes SorianoNo ratings yet

- Hussein2016 PesticidaDocument7 pagesHussein2016 PesticidaHelena Ribeiro SouzaNo ratings yet

- 16 - Entomo eDocument12 pages16 - Entomo eMitha Dan MithaNo ratings yet

- The Efficacy of Some Commercially Available InsectDocument5 pagesThe Efficacy of Some Commercially Available InsectHaitao GuanNo ratings yet

- Mason R PDFDocument11 pagesMason R PDFReynaldo Caballero QuirozNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Plant-Based Repellents Against Anopheles Mosquitoes: A Systematic ReviewDocument8 pagesEfficacy of Plant-Based Repellents Against Anopheles Mosquitoes: A Systematic ReviewSitti XairahNo ratings yet

- Deet & DebaDocument5 pagesDeet & DebaDeepak MadhraniNo ratings yet

- Antifungal Susceptibility Pattern Against Dermatophytic Strains Isolated From Humans in Anambra State, NigeriaDocument8 pagesAntifungal Susceptibility Pattern Against Dermatophytic Strains Isolated From Humans in Anambra State, NigeriaIJAERS JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Articulo Deet Consecuencias de Su UsoDocument7 pagesArticulo Deet Consecuencias de Su UsoMIGUEL ANGEL VANEGAS RODRIGUEZNo ratings yet

- Essential Oils of Melaleuca, Citrus, Cupressus, and Litsea For The Management of Infections Caused by Candida Species - A SysRevDocument18 pagesEssential Oils of Melaleuca, Citrus, Cupressus, and Litsea For The Management of Infections Caused by Candida Species - A SysRevDidi Nurhadi IllianNo ratings yet

- In Vitro Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of 5 AnDocument5 pagesIn Vitro Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of 5 AnWendy VargasNo ratings yet

- Mosquito Repellent Activity of Phytochemical ExtractsDocument6 pagesMosquito Repellent Activity of Phytochemical ExtractsYutaNo ratings yet

- TMP 5 DA1Document13 pagesTMP 5 DA1FrontiersNo ratings yet

- Insects 13 01077Document13 pagesInsects 13 01077japoru hanNo ratings yet

- Mosquito Repellent Property of Ylang YlangDocument9 pagesMosquito Repellent Property of Ylang Ylangaeno751No ratings yet

- B108598KDocument3 pagesB108598KRAJKAMKAMALNo ratings yet

- Vol17-N1-2 Efectividad de Repelentes Comerciales y Esencias Botánicas Contra LaDocument8 pagesVol17-N1-2 Efectividad de Repelentes Comerciales y Esencias Botánicas Contra Lafabritziomiguel4No ratings yet

- Review: Nanovaccines: Recent Developments in VaccinationDocument9 pagesReview: Nanovaccines: Recent Developments in VaccinationGina CubillasNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 2 3Document9 pagesChapter 1 2 3Gio Nhel LachicaNo ratings yet

- PNAS 2008 Katritzky 7359 64Document6 pagesPNAS 2008 Katritzky 7359 64KevinMegoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 2019 Final DefenseDocument8 pagesChapter 1 2019 Final DefenseHidayaNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument7 pagesChapter IPhantom ThiefNo ratings yet

- 8ebc PDFDocument5 pages8ebc PDFFammy SajorgaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of The Most Commonly Used Mosquitoes Repellent in Households in Niameycity (Niger)Document10 pagesEffectiveness of The Most Commonly Used Mosquitoes Repellent in Households in Niameycity (Niger)IJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Natural Products Against Sand Fly Vectors of Leishmaniosis: A Systematic ReviewDocument15 pagesNatural Products Against Sand Fly Vectors of Leishmaniosis: A Systematic ReviewDerrick Scott FullerNo ratings yet

- Formulation and Evaluation of Home Made Poly HerbaDocument9 pagesFormulation and Evaluation of Home Made Poly Herbasajeel ur rahmanNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Mosquito RepellentsDocument11 pagesEffectiveness of Mosquito RepellentsZeth Lachica100% (1)

- 28 13v3i1 4 PDFDocument4 pages28 13v3i1 4 PDFariaNo ratings yet

- Citronella Oil: Its Properties and UsesDocument7 pagesCitronella Oil: Its Properties and UsesJemrei AlbertoNo ratings yet

- 3is Chap 1 5Document37 pages3is Chap 1 5yawa koNo ratings yet

- Potential Test of Ethanol Extract From Onion (Allium Cepa L) Leaves As A Repellent To Aedes AegyptiDocument11 pagesPotential Test of Ethanol Extract From Onion (Allium Cepa L) Leaves As A Repellent To Aedes AegyptiNeli OlivNo ratings yet

- Antibacterial Activity (P. Angulata) 2015.01 OPEMDocument10 pagesAntibacterial Activity (P. Angulata) 2015.01 OPEMoscarbio2009No ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Orange Peel As An Mosquito Repellent PDFDocument17 pagesThe Effectiveness of Orange Peel As An Mosquito Repellent PDFXander JaniolaNo ratings yet

- Probing Into The Edible Vaccines: Newer Paradigms, Scope and RelevanceDocument13 pagesProbing Into The Edible Vaccines: Newer Paradigms, Scope and Relevanceنوره نورNo ratings yet

- Roduction of Mosquito Repellent Using Orange PeelsDocument16 pagesRoduction of Mosquito Repellent Using Orange PeelsSamuel UdoemaNo ratings yet

- ThePrimaryMechanisms of Pesticide Action (MoA)Document11 pagesThePrimaryMechanisms of Pesticide Action (MoA)Catherine TangNo ratings yet

- Ivermectin: Enigmatic Multifaceted Wonder' Drug Continues To Surprise and Exceed ExpectationsDocument11 pagesIvermectin: Enigmatic Multifaceted Wonder' Drug Continues To Surprise and Exceed ExpectationsnemoNo ratings yet

- Antibacterial Activity of Two Common Garden WeedsDocument16 pagesAntibacterial Activity of Two Common Garden WeedsMay LacdaoNo ratings yet

- I R I V H D: Nsecticide Esistance in Nsect EctorsDocument22 pagesI R I V H D: Nsecticide Esistance in Nsect EctorsNemay AnggadewiNo ratings yet

- Bermuda Grass (Cynodon Dactylon) As An Alternative Antibacterial Agent Against Staphylococcus AureusDocument8 pagesBermuda Grass (Cynodon Dactylon) As An Alternative Antibacterial Agent Against Staphylococcus AureusIOER International Multidisciplinary Research Journal ( IIMRJ)No ratings yet

- Lecture Notes IPDMDocument82 pagesLecture Notes IPDMApoorva Ashu100% (1)

- 43874PDFDocument12 pages43874PDFFarm MagazineNo ratings yet

- 2 Acylamino 5 Nitro 1,3 Thiazoles PDFDocument8 pages2 Acylamino 5 Nitro 1,3 Thiazoles PDFJulianaRinconLopezNo ratings yet

- Madrid 2009Document4 pagesMadrid 2009Alexandre MatiasNo ratings yet

- Crespo2011 PDFDocument6 pagesCrespo2011 PDFDANIELA MALAGÓN MONTAÑONo ratings yet

- EUCALEM O Chapter 1 4 1 2 AutosavedDocument20 pagesEUCALEM O Chapter 1 4 1 2 AutosavedDiosario SubiateNo ratings yet

- Vaccination Against Coccidial Parasites. The Method of Choice?Document10 pagesVaccination Against Coccidial Parasites. The Method of Choice?Gopi MarappanNo ratings yet

- NeemDocument26 pagesNeemRafael Reyes RamirezNo ratings yet

- Minutes From The WINSA Meeting - Final 29.08.2023Document27 pagesMinutes From The WINSA Meeting - Final 29.08.2023JOSE FRANCISCO FLORES LOZANONo ratings yet

- Exploration of Phytochemicals Found in Terminalia Sp. and Their - 113129Document11 pagesExploration of Phytochemicals Found in Terminalia Sp. and Their - 113129M gozariNo ratings yet

- Modelo de CarrageninaDocument8 pagesModelo de CarrageninaSandra RiveraNo ratings yet

- Learning Action Cell Implementation Plan (Tle Department)Document4 pagesLearning Action Cell Implementation Plan (Tle Department)AlmaRoxanneFriginal-TevesNo ratings yet

- Tda 7419Document30 pagesTda 7419heviandriasNo ratings yet

- COOKERY 9 Q3.Mod1Document5 pagesCOOKERY 9 Q3.Mod1Jessel Mejia Onza100% (4)

- 2intro To LLMDDocument2 pages2intro To LLMDKristal ManriqueNo ratings yet

- Tesa-60150 MSDSDocument11 pagesTesa-60150 MSDSBalagopal U RNo ratings yet

- NO Memo No. 21 S. 2018 Adherence To Training Policy PDFDocument10 pagesNO Memo No. 21 S. 2018 Adherence To Training Policy PDFKemberly Semaña PentonNo ratings yet

- CHEMEXCILDocument28 pagesCHEMEXCILAmal JerryNo ratings yet

- Manual Tesa Portable ProgrammerDocument39 pagesManual Tesa Portable ProgrammeritmNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions Grade 12 ModuleDocument25 pagesContemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions Grade 12 ModuleFaye Corazon GaurinoNo ratings yet

- Question 5 (Right Form of Verbs)Document4 pagesQuestion 5 (Right Form of Verbs)E TreatmentNo ratings yet

- Activity-2-White. Gadfrey Jahn PDocument2 pagesActivity-2-White. Gadfrey Jahn PGadfrey jahn WhiteNo ratings yet

- Coast Artillery Journal - Oct 1946Document84 pagesCoast Artillery Journal - Oct 1946CAP History LibraryNo ratings yet

- Clear Codes List-NokiaDocument8 pagesClear Codes List-NokiaocuavasNo ratings yet

- Project MarketingDocument88 pagesProject MarketingAnkita DhimanNo ratings yet

- Interest InventoriesDocument7 pagesInterest Inventoriesandrewwilliampalileo@yahoocomNo ratings yet

- Irda Jun10Document96 pagesIrda Jun10ManiNo ratings yet

- BenfordDocument9 pagesBenfordAlex MireniucNo ratings yet

- MTA uniVAL Technical Data Sheet v00Document1 pageMTA uniVAL Technical Data Sheet v00muhammetNo ratings yet

- Soal BAHASA INGGRIS XIIDocument5 pagesSoal BAHASA INGGRIS XIIZiyad Frnandaa SyamsNo ratings yet

- 3987 SDS (GHS) - I-ChemDocument4 pages3987 SDS (GHS) - I-ChemAmirHakimRusliNo ratings yet

- Versatile, Efficient and Easy-To-Use Visual Imu-Rtk: Surveying & EngineeringDocument4 pagesVersatile, Efficient and Easy-To-Use Visual Imu-Rtk: Surveying & EngineeringMohanad MHPSNo ratings yet

- wst03 01 Que 20220611 1Document28 pageswst03 01 Que 20220611 1Rehan RagibNo ratings yet

- Pioneering Urban Practices in Transition SpacesDocument10 pagesPioneering Urban Practices in Transition SpacesFloorin OlariuNo ratings yet

- Lab Manual (Text)Document41 pagesLab Manual (Text)tuan nguyenNo ratings yet

- Turbine Gas G.T.G. 1Document17 pagesTurbine Gas G.T.G. 1wilsonNo ratings yet

- Denman - On FortificationDocument17 pagesDenman - On FortificationkontarexNo ratings yet

- Tabel PeriodikDocument2 pagesTabel PeriodikNisrina KalyaNo ratings yet

- Global Wine IndustryDocument134 pagesGlobal Wine IndustrySaifur Rahman Steve100% (2)

- Weebly Homework Article Review Standard 2Document11 pagesWeebly Homework Article Review Standard 2api-289106854No ratings yet