Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Heisman 16

Heisman 16

Uploaded by

TeeemeeeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Heisman 16

Heisman 16

Uploaded by

TeeemeeeCopyright:

Available Formats

Novice Nook

The Road to Carnegie Hall

Dan’s Quote of the Month: "Playing chess is primarily a series of

puzzles, move after move, where you have to take your time and solve

the puzzle: 'What is the best move?’ "

An old joke:

A young man is walking up Broadway and stops an elderly gentleman

to ask: “What is the best way to get to Carnegie Hall?” The old

gentleman does not hesitate; he raises his cane and says, “Practice,

practice!”

Novice Nook The overwhelming majority of chess literature is about theory:

opening theory, improvement theory, tactical ideas, how to think, etc.

Good stuff.

Dan Heisman

But the flip side to theory is practice. How good would you be at golf

if you only took lessons and never played? Just about as good as you

would be if you only played golf and you did not get any golf

“theory”: no one gave you any advice on how to play, you never read

any golf books, nor watched any golf videos. You need both theory

and practice in tennis, golf, chess, math, or just about anything else.

That is why people coming out of college are not as good at their

profession as they will become with experience – they only have the

theory.

So just playing chess is not sufficient; you have practice well. But

what does that mean? Here are some tips about playing and practicing

that will help you improve.

Slow Chess is Necessary Chess

Let’s start with the most notable “problem”: with the proliferation of

internet-based chess, more and more people play primarily on-line and

not over-the-board. But a slow on-line game is often considered to be

30 5 (30 minutes with a five second increment added each move), a

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (1 of 12) [05/12/2002 10:05:26 PM]

Novice Nook

time limit which is considered pretty fast over-the-board!

I always ask, “Who are the best fast chess players in the world?”

Answer: “The best slow players.”

So how did Kasparov, Kramnik, Anand, etc. get to be the best fast

players in the world, by playing slow or playing fast? The answer is by

playing slow, so you should, too if you really wish to improve. Only

by playing slow do you have time on each move to:

1) think about specific types of positions and candidate ideas really

deeply, so that you learn and, when you encounter similar patterns

again, you will be able to both recognize them and also apply what you

have learned. This builds up your mental chess “database” in a

important way fast chess never can, and

2) consider which previous positions (or aspects of a position) you

know that are similar to the one you have now, and whether those

similarities are pertinent to the current position. You can then use your

knowledge to both save calculation time and also feel more confident

that your observations are correct. For example, if you see the pin on

the e-file in this position:

…you can say to yourself, “In

similar positions in the past I have

played Re1 followed by d3

winning the knight for a pawn.

Does that work here?”

So you want your learning to

extend backward (to apply what

you have learned) and forward (to

learn something to apply in the

future). This is one essence of what

experiential learning is all about.

Therefore you need to play slow enough to be able to implement this

learning. The above example could easily be applied even in faster

games, but more complex patterns need time to resolve. Even on-line

you should try to play as slow as your available time allows; not just

30 5, but real games of G/90 or slower.

Not convinced? Then consider that chess is a thinking game, and if

you don’t learn how to think correctly, then you will never be a good

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (2 of 12) [05/12/2002 10:05:26 PM]

Novice Nook

player. Most players learn better thinking methods by taking lessons

from strong players who know how to correct thinking deficiencies.

To think “correctly” (see my archived ChessCafe articles that appeared

in the Skittles Room The Secrets to Real Chess and Applying Steinitz’

Laws, and the Novice Nook Analysis and Evaluation and A Generic

Thought Process), like anything else, requires theory and practice: you

learn what to do, and then practice it every move you ever play. The

point is that thinking correctly in most positions takes time. Playing

almost exclusively fast games obviously precludes practicing

correctly, and so you will never get very good! Sure, fast games are

fine for practicing openings (not the most important part of the game

for most players) and possibly developing decent board vision and

tactical “shots”, but the kind of thinking it takes to plan, evaluate, play

long endgames, and find deep combinations is just not possible in

quick chess. So why study planning, evaluation, endgames, and deep

combinations if you primarily play fast games and can never get to

properly use that knowledge? Yet so many do!

This is worth repeating: While fast games are fun and not completely

worthless, the one requirement for serious improvement is to learn

how to think correctly, and to consistently play many slow games to

practice good thinking habits.

As I originally wrote in my The Secrets to Real Chess article, thinking

correctly (or at least something close to it) is necessary, but not

sufficient for great improvement. In other words, if you don’t learn to

think correctly, you likely never will get a lot better, but just doing that

and ignoring everything else (like time management, and learning

basic tactics and guidelines/principles cold) is not enough in itself.

Now that we have established that the best practice is to play slow

games, you also need to know:

● Whom should you play?

● How often should you play?

● What are some good things to do during play that will enhance

your play and later review of the game?

Whom to Play?

It is usually better to play opponents who are enough better than you to

push you hard, but not so difficult that you have no chance. This

generally means playing those about 100-200 Elo points above you.

The question then becomes, is it best to play only those in that range

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (3 of 12) [05/12/2002 10:05:26 PM]

Novice Nook

and, if so, isn’t that impossible because then no one who is following

the same guideline would ever play you?

Luckily, the answer is that playing only players 100-200 points above

you is not optimum. It is also important to occasionally but

consistently play those 100-200 points below you so that you can learn

“how to win.” Those techniques that work when you are ahead a piece

or even a pawn against the lower rated players are the same techniques

you are supposed to use in those situations against stronger players.

But if you are only competing against players rated above you and not

often playing for a win, then you will not get enough chance to

develop your “technique”.

Only seeking out players rated above you is also not good for your

chess psychology. While the object of each move is to find the best

move, the object of the game is usually to win. But if you only play

those above you, you sometimes change your objective to just holding

on for a draw, and in the long run this kind of mentality is self-

defeating. So I would recommend playing about 70% of your games

against competition that is 100-200 points above you and 30% equal

to or below you. If you are playing in large, open, over-the-board

(OTB) tournaments this would translate to playing “up” a section two

times out of three and playing in your own section one time out of

three. Players should especially play in their own section in

championship tournaments, where it is possible to win titles you will

cherish for the rest of your career. In addition, if your rating is toward

the lower side of your section (say you are rated 1405 in a section that

is Under 1600), then even two times out of three in the U1600 section

and once in the U1800 section is plenty since you are playing mostly

“up” in the U1600 anyway.

Internet players should be patient and wait for reasonably rated

opponents who will play a slow game. I tell my students that if they

put out a challenge they should limit the lower rating of potential

opponents to no more than about 50 points below theirs. It is better to

play one 60+5 game against a player around your rating than four

15+0 games against players 50-200 points below you, even though

those type of games are easier to find. There are also internet slow

leagues and tournaments at many servers, both of which guarantee you

at least one good slow game each week.

Where and How Often?

If staring at the screen for long games is bothersome, consider using a

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (4 of 12) [05/12/2002 10:05:26 PM]

Novice Nook

regular chessboard, and only resorting to the monitor to input your

moves and receive your opponent’s.

I know that a large percentage of my readers almost exclusively play

on the internet – after all, you are reading this on the internet, right!?

But there is a strong case for at least augmenting internet play with

some OTB play, whether in a club or, better yet, a tournament.

Tournament play gives you the kind of concentrated, slow chess that

often helps improve your game, especially if you are inexperienced at

slow play. I would guess that players who have never played OTB

usually gain 50-100 points of playing strength just from competing in

their first long weekend tournament, assuming they play five or more

rounds of very slow chess. Socially there is no comparison; the players

on a server might be friendly and chatty, but being in a live OTB event

is just much better unless you are the shy type who can chat on-line

but never says a peep to those same people when they are standing

there! Sure, an occasional weekend event takes a lot more of your

time, but the benefits are comparatively greater if improvement is your

ultimate goal. Don’t have two day? Try a one-day quad (a round-robin

among four similarly rated players).

How often should you play? If you are trying to improve that means as

often as you can, but playing lots of slow games can be tiring and time

consuming, so most people are not able to play an OTB tournament

every weekend even if one was available down the block. A minimum

of 8 OTB tournaments and about 100 slow games a year is a

reasonable foundation for ongoing improvement. So if you join a local

club and play one slow game a week, then 10 additional 5-round

tournaments would give you that 100. Of course, many good players

improve rapidly by playing much more than that, so additional play

will likely help even more.

Can’t make 100? Then try for 60. If you only play three or fewer

tournaments a year and do not play slow chess regularly at a club (or

on-line, where G/90 and slower play is relatively rare), then do not be

surprised that you are not really improving. After all, if you wanted to

be really good at basketball, would you only play full-court, games a

few times a year and the rest of the time just shoot in your back yard?

That would not make any sense, and neither does the expectation that

playing only a few slow games each year would be sufficient for

dramatic improvement. More likely you will find yourself “rusty” at

each event and be lucky to play yourself into shape before the final

round!

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (5 of 12) [05/12/2002 10:05:26 PM]

Novice Nook

Of course, there is a limit you can tolerate. Even when I was younger

if I played a tournament two weekends in a row I didn’t even want to

look at a chessboard the third week. Some players can play seriously

every week, but they are certainly the exception.

Other Helpful Hints

Suppose you are at a tournament (Note: If you are not playing in a

formal environment, you should still play as if you were: record your

game, play with a clock, follow all tournament rules, etc. No sense in

practicing one way and then playing “for real” another way). What

can you do to enhance your experience? I will not get into the “non-

chess” factors that could take up an entire column, like get plenty of

sleep, eat during long games, etc. Instead I will concentrate on “chess-

stuff”.

Before you play a game, fill in all the information at the top of your

scoresheet. This accomplishes several things, not the least of which is

to get you mentally prepared in the same way to play each game,

somewhat like a foul shooter taking the same number of dribbles

before a foul shot in a basketball game.

During the game write down how much time you - and your opponent,

if you wish - have left after each move, with the possible exception of

“book” opening moves. Most good players record these times. The

idea is to be able to study your time management during the game (see

my earlier ChessCafe article, Time Management During a Chess

Game).

The two principal ways to lose are 1) get outplayed and resign or be

checkmated, or 2) going over on time. Each kind of loss counts equally

– some players would “rather” lose on a time forfeit to save face, but

the scoreboard looks the same. Going over on time is obviously related

to time management, but so is making big blunders by either initially

playing too fast or so slow that you get into time trouble and then have

to play too fast. The type of enormous mistakes that result from fast

play show that you should need to manage your time wisely. Most

players could use a lot of improvement in this area, and recording the

time left after each move is a good way to start.

Should you walk around or not while you are playing? While it is

probably not good for your back or bladder to sit in your chair for

several hours, excessive strolling is not good, either. The old adage is

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (6 of 12) [05/12/2002 10:05:26 PM]

Novice Nook

to think about tactics (analysis) on your time and to think about

strategy (planning) on your opponent’s time. Of course, if the position

is sharp and your opponent only has one or two dangerous moves, you

may as well start analyzing them while he is thinking.

When I worked at the Kasparov-Deep Blue matches for the

International Computer Chess Association, a member of the Deep Blue

team told me that they had installed the following algorithm for the

second match: After its move, while Kasparov was thinking, Deep

Blue was programmed to assume that Kasparov would make the move

that it calculated as best for him during its previous move, and it would

start analyzing that move as if Kasparov was going to make it. If

Kasparov did then make that move, and if Deep Blue had already

exceeded its “nominal” thinking time of 90 seconds per move during

Kasparov’s turn, then Deep Blue would make its reply immediately.

The reason was that in 90 seconds Deep Blue could think 12-13 ply,

but in an additional 90 seconds it was only likely to get to 13 full ply

(approximately). The chances that it would play a different move with

the additional 90 seconds were very low, but the savings in time and

the fact that Kasparov would have to move again immediately

(something not normal with a human opponent) made it a worthwhile

strategy. The moral of the story? It is possible to do some good

analysis on your opponent’s time, so don’t walk around too much!

What openings should you play? When you first begin serious

competition, play sharp openings so that you can strengthen your

tactics. Several weaker students have told me they play “dull”

openings because they are not very good at tactics. Bad strategy! Since

tactics are such an integral part of the game, getting better at them

means improving overall, so work on your weaknesses and see if you

can minimize them! Gambits are great to play when you and your

opponents are not advanced players. The reason is clear: you often get

a “free” attack and your opponents probably don’t have the technique

to win up a pawn anyway if you misplay the position and lose the

initiative.

More experienced players should play the openings that they either

know best or are attempting to learn. The key is that you should look

up your game in an opening book later so that you can confidently

answer the question: “What, if anything, would I do differently next

time if an opponent made all the same moves?”

This is an excellent way to strengthen your mental “opening database”,

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (7 of 12) [05/12/2002 10:05:26 PM]

Novice Nook

especially if you play frequently. It even works with fast games(!)

Instead, suppose your opponent played a move that was not in any of

your books. In that case, try giving the position to ChessMaster 8000

or Fritz 7 and see what it would have done. If the move was not in a

book, it was not likely to be a lot better than the book move and it may

have been a lot worse. In any case, if your opponent takes you “out of

your book” don’t panic, but see if the move is either a possible mistake

or, more likely, a move that will cause you no problems and you can

just develop without any pressure. Once you learn and follow

rigorously all of the important opening principles, you will understand

all kinds of openings even if you don’t know the lines and are very

likely to be fine even in somewhat deep water.

Draws? Think of a draw offer as an offer to remain ignorant about

anything you might have learned during the rest of the game. The

more you are in “learning” mode the more you don’t want a draw.

Only consider a draw under the following circumstances:

1. You are very tired or ill and cannot play your best,

2. The position is so dead drawn that you cannot learn anything,

and playing on would waste everyone’s time, insult your

opponent, and result in a bad reputation for you,

3. It is the final round and a draw ensures you of a prize or a

“goal” you need for the tournament, or

4. Your position is so lost that you cannot understand why your

opponent offered the draw. It is considered rude for you to offer

a draw in this case!

It is probably good advice to follow Bobby Fischer’s example and say

“No” to any draw offer without even considering it. He seemed to be

able to benefit from that extra experience (!) and he also gained the

reputation of a fearless opponent, which in turn ended up enhancing

his results in the long run.

So in most cases it is better to play on, lose, and learn something than

draw and learn nothing. Learning is what will make you a better

player, not getting the extra ½ point.

More practical advice? Learn the more common rules. Most players

don’t know that a three-fold draw by repetition of position has nothing

to do with what moves were made or that the repeated positions do not

have to be consecutive. One common misconception of the rules

involves a player trying to invoke the the "Draw by Insufficient Losing

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (8 of 12) [05/12/2002 10:05:26 PM]

Novice Nook

Chances (ILC) Rule" in OTB play. Since one of the TD's options is to

give the players a time-delay clock, many players confuse these issues

and, instead of claiming a draw by ILC, just ask for a time delay clock.

But there is no rule to allow them to do make this request.

Another example: if your OTB opponent offers you a draw while his

clock is running, he cannot rescind it if you ask to see his move, so

you have nothing to lose by politely saying, “Make your move and I

will consider it.” You should also know that in OTB play a draw

cannot be offered twice in a row by a player unless the position has

changed substantially, so if your opponent illegally offers a draw

multiple times (“begging for a draw”), it is correct to ask him to stop

and, if he does not do so, you should notify the TD.

If you are playing OTB, you should stop keeping score when there is

less than five minutes left in a time control but, if you have more than

five, continue to keep score even if your opponent has less although

you are allowed to stop. The reason? If you stop keeping score you

will have a tendency to play too fast and to lose the advantage of

having more time. There is one exception: when your opponent is

short on time you should stop keeping score too even though you have

lots more: if you are losing badly then it is silly to give your opponent

extra time to figure out how to avoid large blunders, so just in this one

case it is correct to stop keeping score and play quickly. However, if

you are not clearly losing, wait until you have five minutes left and

then write “5” next to your move - remembering to write how much

time you have remaining next to your moves - and that should be the

last thing you write on your scoresheet until after the game. Turn your

scoresheet over to remind you that you have to start moving quickly!

Should you play the man or the board? Players who participate in

open, Swiss events often do not know their opponents as well as

international and club players do, so playing the board is always safer.

On the other hand, if you know your opponent has a strong

predilection toward something, like enjoying tactics or endgames or

the Sicilian, avoiding those might be beneficial. Even then, going

against what position requires may not be correct; let me relate a story

from my book The Improving Annotator:

I was a C player paired with an 1800 player whom in the previous

round had stated, “I live for the endgame.” During the game I had a

choice of going for a slightly better endgame or staying in the

middlegame. Normally I would have, without hesitation, simplified to

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (9 of 12) [05/12/2002 10:05:26 PM]

Novice Nook

the endgame, but I on this occasion I did hesitate because of my

opponent’s statement. Nevertheless, I finally decided it was the correct

strategy and traded down into the endgame anyway. The result was

that I greatly outplayed my opponent in the endgame, winning nicely.

Moral: playing the man can sometimes be overdone.

When you are finished an OTB game, after you and your opponent

mark your result on the pairing sheet and if you have the time go over

the game (possibly with a coach or stronger player) in the skittles

room. This post-mortem is not only friendly, but also gives you insight

into what your opponents were thinking and helps you review ideas

both players considered during the game. You should even practice

this on-line if your opponent is amenable.

What are good books for practical, rather than theoretical advice? One

that comes to mind is Chess for Tigers 2nd Edition, by Simon Webb.

There is also quite a bit of “practical” advice contained in many fine

books, such as the very advanced The Seven Deadly Chess Sins by

Rowson or many of John Nunn’s non-opening books. Besides

Everyone’s Second Chess Book, which offers both practical and

theoretical advice, my sixth book, A Parent’s Guide to Chess is full of

practical advice for – you guessed it – parents of young chess players.

Reading good advice on practical play often gives you a better “bang

for the buck” than studying ten new opening books.

Counting Redux:

Last month’s Novice Nook was “A Counting Primer”. Shortly after

publication two of my students played the following practice game:

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 Nf6 5.d3 Be7 (? - a common

mistake, overlooking the Removal of the Guard tactic 6.Bxc6 and

7.Nxe5) 6.O-O (?-ditto) O-O (?) 7.Re1 (?) Bc5? 8.Bxc6 Ng4? What

should White do?

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (10 of 12) [05/12/2002 10:05:26 PM]

Novice Nook

First you must recognize that

Black’s “threat” to win the

exchange and a pawn with

9…Bxf2+ and 10…Bxe1 wins less

material than the recapture

8…dxc6! If you did not realize

this, then you really should take

some time to review the value of

the pieces and make sure not to

confuse “losing the exchange” with

“losing a rook”, a common but

egregious error. In other words,

don’t think “I am losing a rook” – the rook is guarded, so you are only

losing the exchange, plus a pawn, which is worth less than a piece in

most positions.

However, bonus points if you saw that 9…Nxf2 is better and more

complicated than 9…Bxf2+, so ignoring the threat completely and just

saving the bishop on c6 with 9.Ba4 or 9.Bd5, while decent, is still not

best.

Highest grades if you found the correct 9.d4! when, no matter how

Black wriggles, he is losing a piece.

Copyright 2002 Dan Heisman. All rights reserved.

Dan teaches on the ICC as Phillytutor.

Order Dan's new book A Parent's Guide to Chess

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (11 of 12) [05/12/2002 10:05:26 PM]

Novice Nook

[The Chess Cafe Home Page] [Book Reviews] [Bulletin Board] [Columnists]

[Endgame Studies] [The Skittles Room] [Archives]

[Links] [Online Bookstore] [About The Chess Cafe] [Contact Us]

Copyright 2002 CyberCafes, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

"The Chess Cafe®" is a registered trademark of Russell Enterprises, Inc.

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (12 of 12) [05/12/2002 10:05:26 PM]

You might also like

- How to Study Chess on Your Own: Creating a Plan that Works… and Sticking to it!From EverandHow to Study Chess on Your Own: Creating a Plan that Works… and Sticking to it!Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Iossif Dorfman The Method in Chess PDFDocument210 pagesIossif Dorfman The Method in Chess PDFPetko Petkov100% (14)

- Step 3 Thinking AheadDocument12 pagesStep 3 Thinking AheadNapek KhoNo ratings yet

- #9 The Grandmaster's Openings Laboratory 2 by Igor SmirnovDocument146 pages#9 The Grandmaster's Openings Laboratory 2 by Igor SmirnovHari Haran100% (1)

- Fake Chess Book of Champions - SPC - SinglesDocument95 pagesFake Chess Book of Champions - SPC - Singlesadesso napoliNo ratings yet

- Grivas Opening Laboratory - Vol 1 - Efstratios GrivasDocument441 pagesGrivas Opening Laboratory - Vol 1 - Efstratios GrivasJesus100% (3)

- Game of Coaching EbookDocument97 pagesGame of Coaching EbookasklorraineNo ratings yet

- Chess Calculation Training For Kids and Club Players EdouardDocument282 pagesChess Calculation Training For Kids and Club Players Edouard109eh100% (2)

- How To Succeed Ebook PDFDocument41 pagesHow To Succeed Ebook PDFregistermail100% (4)

- Jeremy Silman - The Reassess Your Chess Workbook - 2001Document220 pagesJeremy Silman - The Reassess Your Chess Workbook - 2001bross100No ratings yet

- Book Reviews: The New ReinfeldDocument5 pagesBook Reviews: The New ReinfeldruturajbarikNo ratings yet

- Novice Nook: Hand-Waving Is Worse Than Hope ChessDocument7 pagesNovice Nook: Hand-Waving Is Worse Than Hope ChessPera PericNo ratings yet

- Feel The Blearn 6-16-2016 RevisionDocument8 pagesFeel The Blearn 6-16-2016 RevisionAlex RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Tactics - Effectiveness of A Spaced Repetition System (SRS) For Memorizing Tactical Patterns For Long-Term Skill Gain - Chess Stack Exchange PDFDocument3 pagesTactics - Effectiveness of A Spaced Repetition System (SRS) For Memorizing Tactical Patterns For Long-Term Skill Gain - Chess Stack Exchange PDFthierry100% (1)

- Lesson - 1Document4 pagesLesson - 1Dinut CatalinNo ratings yet

- 35 Off Felt TrainingDocument3 pages35 Off Felt TrainingSergio GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Novice NookDocument9 pagesNovice NookAbhishek Vyas100% (1)

- Read This First! - How To Play... : The Basic RuleDocument2 pagesRead This First! - How To Play... : The Basic RuleJoséDianaNo ratings yet

- How To Read Jacob's Books - Quality Chess BlogDocument1 pageHow To Read Jacob's Books - Quality Chess BlogrcmartinezcamposNo ratings yet

- Build Your Opening RepertoireDocument3 pagesBuild Your Opening RepertoireMaestro JayNo ratings yet

- Improving Endgame Technique 1Document103 pagesImproving Endgame Technique 1William Alberto Caballero RoncalloNo ratings yet

- 5 Power-sciViveDocument16 pages5 Power-sciViveishanka sankalpaNo ratings yet

- What Are Escape Rooms - (PDFDrive)Document22 pagesWhat Are Escape Rooms - (PDFDrive)João Paulo da MataNo ratings yet

- Novice Nook: Tactical Sets and GoalsDocument6 pagesNovice Nook: Tactical Sets and GoalsPera PericNo ratings yet

- The Chess Tutor John KtejikDocument8 pagesThe Chess Tutor John KtejikFrancesco Rosseti0% (1)

- 10 Steps To LearningDocument8 pages10 Steps To LearningSteveNo ratings yet

- Zenith Solo: Peter Rudin-BurgessDocument10 pagesZenith Solo: Peter Rudin-BurgessGašper SambolecNo ratings yet

- Homebrew World 1.5.1Document24 pagesHomebrew World 1.5.1Marcin CiekalskiNo ratings yet

- Homebrew World PDFDocument26 pagesHomebrew World PDFRPGERNo ratings yet

- Extracted Pages From Silman, Jeremy - The Reassess Your Chess WorkbookDocument8 pagesExtracted Pages From Silman, Jeremy - The Reassess Your Chess WorkbookNicolás Riquelme AbuffonNo ratings yet

- Woodpacker Method DivididoDocument17 pagesWoodpacker Method DivididoLeandro OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Algunas Nuevas Ideas AjedrecisticasDocument2 pagesAlgunas Nuevas Ideas AjedrecisticasKaos AquariusNo ratings yet

- 42 Thinking Skills You Can Learn From Doing Jigsaw PuzzlesDocument10 pages42 Thinking Skills You Can Learn From Doing Jigsaw PuzzlesKathryahnna OsceanayahNo ratings yet

- Nptel BookDocument282 pagesNptel BookShubhay TripathiNo ratings yet

- Chueca - The Secrets To Progress in ChessDocument14 pagesChueca - The Secrets To Progress in ChessPaul Samson Topacio75% (4)

- Ruling Not Rules Is InsufficientDocument4 pagesRuling Not Rules Is Insufficientfreepdf11062023No ratings yet

- Writing: A Great Way To Keep FitDocument2 pagesWriting: A Great Way To Keep FitNo Creo Que A NadieNo ratings yet

- Perfect Practice: No Waste. 100% EffectiveDocument16 pagesPerfect Practice: No Waste. 100% EffectiveJtony Gills100% (1)

- THE WELLDocument3 pagesTHE WELLhannahnguyen140205No ratings yet

- Rrtyu 324download - Mobile (Fj15)Document6 pagesRrtyu 324download - Mobile (Fj15)behzad parsiNo ratings yet

- Dave Riker - SS Technical Manual - Web Site PDFDocument6 pagesDave Riker - SS Technical Manual - Web Site PDFJohannes Hansen0% (1)

- How To Study & Improve at ChessDocument16 pagesHow To Study & Improve at ChessCerebral007100% (1)

- Tool Kits: Strate Ies For LearnersDocument10 pagesTool Kits: Strate Ies For LearnersChungNo ratings yet

- Attack and Win by Gm Igor SmirnovDocument104 pagesAttack and Win by Gm Igor Smirnovabcgm123No ratings yet

- Grade 8 - Learners Module pp.3-6.: Goodmorning Class! Good Morning Sir Coloma in The Name of The Father AmenDocument9 pagesGrade 8 - Learners Module pp.3-6.: Goodmorning Class! Good Morning Sir Coloma in The Name of The Father AmenGELLIE BETH SALOMONNo ratings yet

- Jeremy Silman - The Reassess Your Chess - Workbook 1st Ed 2001Document220 pagesJeremy Silman - The Reassess Your Chess - Workbook 1st Ed 2001Axente AlexandruNo ratings yet

- EN5ider 020 - Those Who CrawlDocument5 pagesEN5ider 020 - Those Who CrawlfelixhasspamNo ratings yet

- Best Chess Openings For Beginners at PDFDocument1 pageBest Chess Openings For Beginners at PDFDavid OspinaNo ratings yet

- The Reassess Your Chess Workbook PDFDocument220 pagesThe Reassess Your Chess Workbook PDFOscar Iván Bahamón83% (6)

- Chess BookDocument169 pagesChess Bookblue2eye100% (10)

- Does Playing Correspondence Chess Improve Your GameDocument5 pagesDoes Playing Correspondence Chess Improve Your GamePalpakNo ratings yet

- Reznick - One Introduction To Mathematical ResearchDocument4 pagesReznick - One Introduction To Mathematical Researchgrajojohndave1No ratings yet

- 2264571-Downtime Charges v1.1Document3 pages2264571-Downtime Charges v1.1MariaNo ratings yet

- The Engaging DM: A Guide For Dungeon Master's On How To Create A More Engaging Environment For Their PlayersDocument7 pagesThe Engaging DM: A Guide For Dungeon Master's On How To Create A More Engaging Environment For Their PlayersRodrigo Tenorio0% (1)

- Materials and Equipment:: (1) Yellow Tiles: "VARIOUS EXERCISES"Document2 pagesMaterials and Equipment:: (1) Yellow Tiles: "VARIOUS EXERCISES"Juan AlexandroNo ratings yet

- Master Player ReflectionDocument9 pagesMaster Player ReflectionEddie Resurreccion Jr.No ratings yet

- Mapeh 8 Q3 - Scrabble DLPDocument13 pagesMapeh 8 Q3 - Scrabble DLPBetty Mae De JesusNo ratings yet

- Chesskid'S Parent Survival Ebook: The Ultimate Guide To Scholastic ChessDocument11 pagesChesskid'S Parent Survival Ebook: The Ultimate Guide To Scholastic ChesspongNo ratings yet

- Creativity ExercisesDocument15 pagesCreativity ExercisesBartosz KosińskiNo ratings yet

- Novice Nook: The Goal Each MoveDocument10 pagesNovice Nook: The Goal Each Moveinitiative1972No ratings yet

- 10 Ways To Improve in Chess Remote Chess AcademyDocument6 pages10 Ways To Improve in Chess Remote Chess AcademyTamalNo ratings yet

- Science 6 Quarter 2 Week 1-Day 1Document36 pagesScience 6 Quarter 2 Week 1-Day 1Analy RoseteNo ratings yet

- Q&A With Aurtur Yusupov (Quality Chess August 2013)Document10 pagesQ&A With Aurtur Yusupov (Quality Chess August 2013)dues babaoNo ratings yet

- Extracted Pages From Kosikov - Elements of Chess StrategyDocument3 pagesExtracted Pages From Kosikov - Elements of Chess StrategyNicolás Riquelme AbuffonNo ratings yet

- Carlsen: at WijkDocument64 pagesCarlsen: at WijkTeeemeeeNo ratings yet

- Modern Chess Magazine - SampleDocument6 pagesModern Chess Magazine - SampleTeeemeeeNo ratings yet

- Ilovepdf MergedDocument24 pagesIlovepdf MergedTeeemeeeNo ratings yet

- The 2012 Canadian Survey On Disability (CSD) and The 2006 Participation and Activity Limitation Survey (PALS)Document5 pagesThe 2012 Canadian Survey On Disability (CSD) and The 2006 Participation and Activity Limitation Survey (PALS)TeeemeeeNo ratings yet

- 1984 12 LDocument60 pages1984 12 LOscar Estay T.100% (1)

- All About ChessDocument3 pagesAll About ChessEugene RiashiroNo ratings yet

- ChessDocument52 pagesChessFactura Neil100% (1)

- Draw 2Document52 pagesDraw 2ha heNo ratings yet

- ChxbuyDocument27 pagesChxbuyrahulNo ratings yet

- Alexey Suetin & Ilya Odessky - Soviet Chess Strategy PDFDocument242 pagesAlexey Suetin & Ilya Odessky - Soviet Chess Strategy PDFCelestinoAnabelaCarvalho100% (20)

- 11 05 2023Document4 pages11 05 2023Mounir YousfiNo ratings yet

- 2011 - Chess Life 07Document84 pages2011 - Chess Life 07KurokreNo ratings yet

- Carpeta Tributaria - 08062023 - 230608 - 121443Document30 pagesCarpeta Tributaria - 08062023 - 230608 - 121443MilenaNo ratings yet

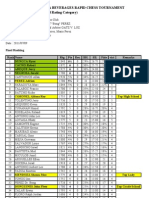

- 1st Saturday July 9 Final Standing - ListDocument3 pages1st Saturday July 9 Final Standing - ListFrancis A. BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- Smerdons Scandinavian Extract PDFDocument28 pagesSmerdons Scandinavian Extract PDFAmo LupoxNo ratings yet

- 10 Proven Strategies To Avoid BlundersDocument8 pages10 Proven Strategies To Avoid BlundersQuake FreshNo ratings yet

- ChessDocument11 pagesChessjap japNo ratings yet

- Belgrade Gambit MarinDocument4 pagesBelgrade Gambit MarinVictor CiocalteaNo ratings yet

- Summary - PetroffDocument41 pagesSummary - PetroffArman SiddiqueNo ratings yet

- Gufeld - Improve Your Chess Tactics - 111 Chess Tactics Puzzles TO SOLVE - BWC PDFDocument19 pagesGufeld - Improve Your Chess Tactics - 111 Chess Tactics Puzzles TO SOLVE - BWC PDFpablomatusNo ratings yet

- The Problemist 012Document8 pagesThe Problemist 012mutiseusNo ratings yet

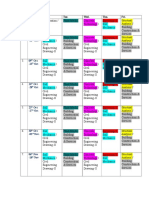

- Timetable Year II Day Semester I RevisedDocument3 pagesTimetable Year II Day Semester I RevisedSimaoNo ratings yet

- New Chess CatalogDocument27 pagesNew Chess CatalogPriya AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Eastern Asia Juniors & Girls Chess Championship 2023Document4 pagesEastern Asia Juniors & Girls Chess Championship 2023prima NursinggihNo ratings yet

- BANGKAL NM Interim Ranking ListDocument4 pagesBANGKAL NM Interim Ranking ListFrancis A. BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- Albin Counter GambitDocument88 pagesAlbin Counter GambitTúlio FernandesNo ratings yet

- In Tro Duc TionDocument8 pagesIn Tro Duc Tionroy.vanderwelkNo ratings yet

- (Pe) g6 - Board GamesDocument11 pages(Pe) g6 - Board Gamesastraeax pandaNo ratings yet

- Holtzhausen Louis. 40 Positional Tactics. Volume 1Document86 pagesHoltzhausen Louis. 40 Positional Tactics. Volume 1Leonid Stein100% (1)

- Kasparov,.Gary. .My - Great.predecessors - Part.1 Ocred 041 060Document20 pagesKasparov,.Gary. .My - Great.predecessors - Part.1 Ocred 041 060kangchuanqiNo ratings yet

- AJEDREZ The Kalashnikov Sicilian (B32)Document9 pagesAJEDREZ The Kalashnikov Sicilian (B32)jogonNo ratings yet