Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Suskind 2013 Aa

Suskind 2013 Aa

Uploaded by

Lucky Ade SessianiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Suskind 2013 Aa

Suskind 2013 Aa

Uploaded by

Lucky Ade SessianiCopyright:

Available Formats

473146

mmunication Disorders QuarterlySuskind et al.

© Hammill Institute on Disabilities 2013

Reprints and permissions: http://www.

CDQ34410.1177/1525740112473146Co

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Research

Communication Disorders Quarterly

An Exploratory Study of “Quantitative

34(4) 199–209

© Hammill Institute on Disabilities 2013

Reprints and permissions:

Linguistic Feedback”: Effect of LENA sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1525740112473146

cdq.sagepub.com

Feedback on Adult Language Production

Dana Suskind, MD1, Kristin R. Leffel, BS1, Marc W. Hernandez, PhD1,

Shannon G. Sapolich, BA1, Elizabeth Suskind, BS1, Erin Kirkham, MD2,

and Patrick Meehan, MSW3

Abstract

A child’s early language environment is critical to his or her life-course trajectory. Quantitative linguistic feedback utilizes

the Language ENvironment Analysis (LENA) technology as a tool to analyze verbal interactions and reinforce behavior

change. This exploratory pilot study evaluates the feasibility and efficacy of a novel behavior-change strategy, quantitative

linguistic feedback, to influence adult linguistic behavior and, as a result, a child’s early language environment. Baseline LENA

outcome measures (i.e., adult word count [AWC] and conversational turn count [CTC]) were obtained from a diverse

sample of 17 nonparental caregivers and their typically developing children (charges) ages 10 to 40 months. Caregivers

participated in a one-time educational intervention focusing on enriching a child’s home language environment, interpreting

feedback from the baseline LENA recordings, and setting language goals for the following session. Post-intervention, six

additional LENA recordings were obtained weekly to measure linguistic behavior. Caregivers showed a significant and

prolonged increase from mean baseline to mean postintervention AWC and CTC as measured by LENA–AWC: mean

difference = 395 words per hour, 31.6% increase, t = 3.29, p < .01; CTC: mean difference = 14 turns per hour, 24.9% increase,

t = 3.54, p < .01. Preliminary results indicate that a one-time educational intervention combined with quantitative linguistic

feedback may have a positive effect on caregiver language output, thus enhancing the child’s language environment. This

study represents an initial step in the development and evaluation of a novel behavior-change strategy. We propose that

quantitative linguistic feedback will add significantly to the arsenal of clinical and research tools used to evaluate and enrich

a child’s early language environment.

Keywords

speech and language therapy, parent education, specific language impairment (SLI)

Background Selzer, & Lyons, 1991; Kaiser & Hancock, 2003a, 2003b;

Landry, Smith, Swank, & Guttentag, 2008; Landry, Smith,

A child’s early language environment is critical to his or her Swank, & Miller-Loncar, 2000; Reilly et al., 2010; Snow,

life-course trajectory (Forget-Dubois & Dionne, 2009; Law 1972). This research demonstrates clearly that a qualita-

& Rush, 2009; Phillips, 2011). Language exposure not only tively and quantitatively rich early language environment is

bears an obvious relationship to a child’s linguistic devel- paramount for a child to realize his or her linguistic poten-

opment but also significantly influences a child’s overall tial and, ultimately, life-course potential as well.

cognitive and educational achievement (Hart & Risley, Disparities in early language environments, along with

1992, 1995; Huttenlocher, Vasilyeva, Cymerman, & Levine, their profound lifelong consequences, have been

2002; Kashinath, Woods, & Goldstein, 2006). Hart & demonstrated in children with developmental disabilities

Risley’s landmark study demonstrated a significant correla-

tion between the number of words a child hears by age 3 1

University of Chicago, IL, USA

and his or her ultimate IQ and academic success. Equally 2

University of Washington, Seattle, USA

compelling is the literature linking the qualitative aspects 3

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA

of language exposure, including complexity of speech,

Corresponding author:

adult-to-child interaction and responsive caregiving, with a

Dana L. Suskind, Department of Pediatrics and Otolaryngology,

child’s ultimate educational outcome (Bornstein, Tamis- University of Chicago, 5841 S Maryland Ave., mc 1035, Chicago, IL, USA.

LeMonda, Hahn, & Haynes, 2008; Huttenlocher, Haight, Email: dsuskind@surgery.bsd.uchicago.edu

Downloaded from cdq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 8, 2015

200 Communication Disorders Quarterly 34(4)

such as autism, children with intellectual disabilities, chil- varied approaches, philosophies, and target populations,

dren with hearing loss whose parents are hearing, and chil- overall Roberts and Kaiser found that, with relatively mod-

dren with specific language impairments (SLI), as well as est training, parents successfully implemented language

children of low socioeconomic status (SES; DesJardin & interventions, which in turn positively affected children’s

Eisenberg, 2007; Hammer, Tomblin, Zhang, & Weiss, 2001; receptive and expressive language. Most interventional

Hoff & Tian, 2005; Huttenlocher et al., 1991; Meadow- approaches that Roberts and Kaiser reviewed included a

Orlans, 1997; Reilly et al., 2010; Rowe, 2008; Spencer & broad “social communication focus,” with linguistic strate-

Gutfreund, 1990). These populations have been demon- gies designed to be integrated into daily routines (Roberts

strated to have significantly reduced quantitative and quali- & Kaiser, 2011). The two most common linguistic

tative parental linguistic input. As such, it has been estimated approaches aimed to affect “what the parents say” and

that children living in poverty will have heard 30 million “how much the parents say” (Roberts & Kaiser, 2011).

fewer words by age 3 compared with their more affluent Interventions also sought to enhance parent–child interac-

peers (Hart & Risley, 1995). This gap in linguistic input tion via increased parental responsiveness to the child’s

mirrors an academic achievement gap that is evident from attempts to communicate.

the first day of school and persists throughout adulthood Despite the generally positive outcomes, Roberts and

(Phillips, 2011). Children with hearing loss in particular, Kaiser (2011) identified a number of weaknesses in the

regardless of SES, have been shown to have significant dis- interventions reviewed. They found a lack of detailed

parities in language experiences when compared with nor- descriptions of the interventions, resulting in an inability to

mal-hearing peers. In low-SES children, language disparities pinpoint the intervention components that correlated with

are most often associated with less exposure to and facility specific language improvement (Roberts & Kaiser, 2011).

with academic language (Snow, 1972). For children with In addition, many studies failed to accurately assess care-

hearing loss, however, it is the fundamental development of giver intervention uptake, sustainability of caregiver lan-

listening and spoken language that is at risk. guage behavior change, or the necessary child intervention

Clinical interventions for children who have speech and dosage, for example, frequency and length of intervention

language delays often target the adult caregiver as the cata- program (Roberts & Kaiser, 2011). Furthermore, the pri-

lyst for improving the child’s language development (Kaiser marily middle-class study participants raised the question

& Hancock, 2003a; Kashinath et al., 2006; McWilliam, of external validity and generalizability of results.

2001; Pickston, Golbart, Marshall, Rees, & Roulstone, These shortcomings mirror a similar concern in the over-

2009; Reese, Sparks, & Leyva, 2010; Roberts & Kaiser, all health promotions literature, where studies of complex

2011). As the primary contributors to their child’s language behavioral interventions often lack clarity in descriptions of

environment, adult caregivers are able to enrich their child’s behavioral strategies used (Michie, Johnston, Francis,

home language environment throughout the child’s day. Hardeman, & Eccles, 2008). It has been suggested that the

This family-centered approach is fundamental to the feder- modest behavioral effects often found in interventions are

ally funded early intervention programs for young children linked to this lack of transparency and well-defined behavior-

with disabilities (Individuals With Disabilities Education change strategies used in these interventions (Michie,

Improvement Act of 2004, 2003). While the intervention Fixsen, Grimshaw, & Eccles, 2009). In response to these

literature focuses primarily on parental caregivers, the lit- limitations, the health promotions field has advanced a tax-

erature also supports the incorporation of nonparental care- onomy of theoretically based behavior-change techniques

givers (NPCs; Giurolametto, Weltzman, & Greenberg, (Michie et al., 2011). Michie et al. have proposed a compre-

2003, 2004; Milburn, 2011). Intervening with NPCs is an hensive group of 40 discrete evidence-based behavior-

important method for improving the child’s language envi- change techniques, which they term CALO-RE1 taxonomy.

ronment as NPCs care for the majority of 0- to 4-year-old The CALO-RE taxonomy of strategies is not specific to a

American children; 77% of children of employed mothers particular behavioral intervention type (e.g., smoking or

received care from NPCs in 2010 (Table FAM3.A. Child weight loss) but is, rather, a methodological tool that can be

care: Primary child care arrangements for children 0–4 with generalized to any health promotion intervention. The ulti-

employed mothers by selected characteristics, selected mate goal is to eliminate the ambiguities of interventional

years 1985–2010). strategies so the specific factors and their specific effects in

The literature strongly supports the potential for improv- an intervention are understood. The literature provides

ing the child’s language outcome via the adult caregiver compelling evidence that incorporating these theoretically

(Roberts & Kaiser, 2011). In a meta-analysis of 18 parent- based behavior change techniques into health promotion

implemented language interventions, Roberts and Kaiser interventions is essential to stimulating sustainable behavior-

found significant improvements in receptive and expres- change and advancing the science of behavior change

sive language skills of children 18 to 60 months of age (Abraham & Michie, 2008; Michie et al., 2005; Michie,

(Roberts & Kaiser, 2011). Although the interventions had Jochelson, Markham, & Bridle, 2009).

Downloaded from cdq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 8, 2015

Suskind et al. 201

Aims Bandura writes that a sense of self-efficacy is essential any

time a parent is to take action on behalf of a child’s educa-

It is with appreciation for the critical need for theoretically tion or health status, or act as a child’s teacher and advocate.

based behavior-change strategies in caregiver-directed lan- DesJardin and Eisenberg (2007) also found that caregiver

guage interventions that we describe our preliminary pilot self-efficacy is strongly related to the linguistic skills of

testing of a novel, multifaceted behavior-change strategy young children with hearing loss. Self-efficacy is also asso-

we call quantitative linguistic feedback. This strategy has ciated with more sophisticated language strategies, such as

been developed to facilitate changes in language behavior open-ended questioning and parallel talk, which are in turn

of adult caretakers and to quantify the impact and sustain- correlated with improved language outcomes (Hughes &

ability of intervention in adult linguistic behavior. It is Demo, 1989; Johnston-Brooks, Lewis, & Garg, 2002;

designed to be incorporated into and enhance any existing Raikes & Thompson, 2005; Wolf et al., 2007).

caregiver-directed interventions. Given these theoretical foundations, the parent-directed

The theoretical underpinnings of quantitative linguistic educational intervention was designed to (a) review the

feedback are Bandura’s social cognitive theory (SCT), the importance of a child’s early language environment in rela-

theory of planned behavior (TPB), self-determination the- tion to later language proficiency, (b) understand how the

ory (SDT), and the health belief model (HBM; Ajzen, LENA measures certain critical aspects of this environment

2001; Ajzen, Brown, & Carvajal, 2004; Bandura, 1997; (i.e., adult word count [AWC], conversational turn count

Vansteenkiste & Sheldon, 2006). These theories of behavior [CTC], TV Time [TVT]), and (c) discuss strategies to help

change must be factored into the development of successful parents enrich their child’s language environment.

behavioral intervention techniques (Michie et al., 2008). The technological centerpiece of quantitative linguistic

Guided by such theories, we developed quantitative linguis- feedback’s behavior-change intervention is the LENA

tic feedback with a multifaceted approach that includes a System. The LENA is an innovative recording device that,

mechanism by which adults can set and respond to goals along with its accompanying computer software, can be used

(TPB and goal setting), utilize cues for action or external to automatically capture and analyze a child’s home language

prompts for behavior change (HBM), recognize the environment (Oller, 2010). The LENA quantifies the number

improved language environment they are providing for of words to which a child is exposed and the number of con-

their child, and develop a sense of competency and auton- versational turns the child takes with adult(s) over a continu-

omy in facilitating their child’s development (SCT). ous 16-hr period (Gilkerson & Richards, 2008). The LENA’s

TPB describes “intention” as a critical determinant of quantitative outcome measures are then presented to caregiv-

behavior. Health intention is, itself, determined by beliefs ers, providing them with concrete feedback about where need

and attitudes about treatment (e.g., medication efficacy and for greater language exposure exists and where improvement

adverse effects), subjective social norms (e.g., concern with has been made. Thus, the LENA’s value is not simply for

the opinions of others), past experience (e.g., previous scientific quantification but for providing feedback to the

experience with similar programs), and perceived behav- adult caregivers. In collaboration with a therapist, caregivers

ioral control and self-efficacy (Hagger, Chatzisarantis, & can clearly see a snapshot of the home language environ-

Biddle, 2001). Attitudes, both favorable and unfavorable, ment, consider their role within it, discuss opportunities to

will affect intention and, ultimately, action and adherence, enrich that environment, and importantly, chart and track

or the lack thereof (Ajzen, 1996; Hagger, et al., 2001; White progress toward enrichment. In other words, the quantitative

& Wellington, 2009). Quantitative linguistic feedback outcome measures are utilized as a type of “biofeedback”

encompasses intention by incorporating goals to be set and used for goal setting and measuring progress toward those

accomplished, and, most critically, engages caregivers as goals. Thus, this quantitative linguistic feedback can be used

goal setters. to reinforce traditional approaches used in a wide variety of

HBM maintains that “readiness” to change behaviors is language-development focused interventions.

“activated” by motivational feedback and “cues to action” Quantitative linguistic feedback is a multifaceted tech-

(Janz, Champion, & Stretcher, 2002). External prompts are nique for behavior change that may work through a number

cues to action, which in turn stimulate behavior change. In of different mechanisms as described in the CALO-RE tax-

quantitative linguistic feedback, “cues to action” are the onomy (Michie et al., 2011). For adult caretakers, quantita-

Language ENvironment Analysis (LENA) data that provide tive linguistic feedback offers a mechanism by which they

concrete evidence of a child’s language environment and can set and respond to goals, utilize cues for action or exter-

patterns of change. nal prompts for behavior change (e.g., reviewing LENA

Finally, Bandura’s SCT recognizes self-efficacy―the outcome measures), and recognize the improved language

“belief in one’s capacity to organize and execute the courses environment they are providing for their child. It also instills

of action required to produce given attainments”―as criti- a sense of competency and autonomy in facilitating their

cal for the success of all interventions (Bandura, 1997). child’s development.

Downloaded from cdq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 8, 2015

202 Communication Disorders Quarterly 34(4)

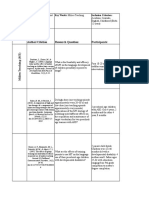

Our initial work evaluating quantitative linguistic feed- Table 1. Nonparental Caregiver Characteristics.

back’s feasibility and efficacy in improving adult quantitative

Nonparental caregiver n %

language behavior is presented here. We hypothesized that

quantitative linguistic feedback would result in a significant Education 17 –

increase in AWC and CTC as measured by the LENA. GED 2 12

Subsequent efforts will focus on demonstrating a correspond- High school diploma 2 12

ing qualitative improvement, sustained linguistic change, as Some college 4 23

well as methods for incorporating this novel strategy into Four year college degree 9 53

existing interventions. Ultimately, the technique of caregiver- Nanny school 2 12

directed, quantitative linguistic feedback holds the promise Race/Ethnicity 17 –

for significantly improving child language outcomes. African American 2 12

Asian 1 6

Hispanic 3 19

Method and Procedures Caucasian 10 63

Did not state 1 6

Design

Primary language 17 –

English 12 71

The study used a prospective case-crossover design involv-

Other 5 29

ing two baseline recordings followed by a single educa- Language spoken with child 17 –

tional intervention and six postintervention LENA feedback English 12 71

recordings. This exploratory pilot study was conducted Other 5 29

with a group of NPCs who were chosen because of their Other language spoken 3 to 6 hours/day 1 20

extensive, focused, and consistent periods of time with the Other language spoken 1 to 3 hours/day 2 40

children in their care. Other language spoken <1 hour/day 2 40

Participants

NPCs. Nineteen English-speaking NPCs caring for typi- Eight children (47%) had one sibling, with four of the sib-

cally developing children were recruited for this study. Of lings younger and one older. One child (6%) had two sib-

the 19 recruited NPCs, 17 (90%) completed the study and lings, with one younger and one older (see Table 2). Five

are included in the present analysis. One NPC dropped out children received primary care from their mothers (9%),

secondary to pregnancy, and another withdrew due to 1 child from his or her NPC (6%), 10 from their mothers and

scheduling difficulties prior to obtaining baseline record- NPCs (9%), and 1 from his or her mother and father (6%).

ings. A table of NPC demographics is shown in Table 1. All All children were from two-parent households with

NPCs were women and ranged in age from 23 to 53 years annual incomes of US$100,000 or more. One parent had

(M = 33.1, SD = 10.1). Their education levels ranged from an associate’s degree, whereas the rest of the parents in

GED to 4-year college degree, with approximately half the study had a 4-year college degree or higher. Forty-one

having a 4-year degree (n = 9; 53%). Two NPCs (12%) percent of parents (n = 14) had attained doctorate degrees.

received specialized child care training (i.e., nanny school). Eleven families responded as Caucasian (65%), three as

Ten NPCs (59%) were Caucasian, with the other 6 repre- Asian (18%), two as multiethnic (12%), and one family

senting a range of races and ethnicities, including African declined to state (6%). All families spoke English as the

American (n = 2; 12%), Asian (n = 1; 6%), and Hispanic (n primary language at home. Five were bilingual, but

= 3; 18%). Nearly one third of the NPCs (n = 5; 29%) reported that they spoke their second language less than

spoke English as a second language. On average, NPCs 1 hr per day.

had 9 years of experience caring for children (SD = 7,

range = 2–28) and a range of 2 months to 3 years caring for

the child in this study (M = 1 year, SD = 9 months). Five of Materials and Procedures

the NPCs (n = 5/17, 29%) cared for at least one other child Recruitment. English-speaking NPCs caring for typically

simultaneously with the child in the study. developing children were recruited through professionals at

the University of Chicago and the surrounding area via

Children and families. Seventeen families participated in this email, online postings, and word of mouth. NPCs were paid

study: 10 girls (n = 10; 59%) and 7 boys (n = 7; 41%). Ages US$100 for completion of the study. Informed consent was

ranged from 10.5 to 40.3 months (M = 20.4 months). In obtained from parents and NPCs. The consent forms

families with multiple children, 1 child between the ages of included an agreement that parents would not know or ask

10 and 42 months was eligible for inclusion in the study. for their NPC’s results or feedback.

Downloaded from cdq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 8, 2015

Suskind et al. 203

Table 2. Family Characteristics. the shirt containing the LENA device. The LENA device

records up to 16 hr of audio, and requires a minimum of

Child n %

12 hr of data for complete and accurate processing. Because

Sex 17 the NPCs all worked less than 12 hr per day, they were

Male 7 41 instructed to keep the device turned on for the maximum

Female 10 59 recording duration and to write down the timestamp present

Number of siblings 17 on the digital display when their interaction with the child

0 8 47 ended for the day (i.e., when they left the child’s home or

1 8 47 when the child was put to bed). NPCs each made a total of

2 1 6 eight recordings during the course of the study: two base-

Level of education line recordings prior to intervention and six postbaseline

Mother 16 – recordings. We used the average of the two baseline record-

Four-year college degree 6 37.5 ings as their baseline measure.

Master’s degree 4 25

Doctorate degree 6 37.5

Educational intervention. After baseline recordings were

Father 16 –

completed, each NPC participated in a language-focused

Associate’s degree 1 6

educational intervention lasting approximately 1 hr at the

Four-year college degree 5 31

Master’s degree 2 13

child’s home. This session included information on child

Doctorate degree 8 50 language development, along with tips for increasing their

Race/Ethnicity 17 – talk and conversational turn-taking with the child. The edu-

Asian 3 18 cational session was conveyed via a short PowerPoint pre-

Caucasian 11 65 sentation, and included the following core components: (a)

Multiethnic 2 11 review of the importance of a child’s early language envi-

Did not state 1 6 ronment (i.e., connection between caregiver linguistic input

Mother employed 16 – and a child’s language and educational success), (b) discus-

At home 1 6 sion of LENA and its target measures (i.e., AWC and CTC),

Outside home 15 94 (c) review of caregiver baseline LENA recordings, and (d)

Primary caregiver 17 – discussion of strategies to enrich a child’s early language

Mother 5 29 environment and raise LENA measures through talking

Nonparental caregiver 1 6 more and increasing conversational turns with a child.

Mother and nonparental caregiver 10 59

Mother and father 1 6 Quantitative linguistic feedback. The research assistant then

provided the NPCs with their individual LENA linguistic

feedback from the baseline recordings, and facilitated the

Demographic and home language survey. NPCs and one par- NPCs’ understanding of the LENA feedback reports and

ent from each family completed a demographic survey, goal setting for the following recordings. LENA feedback

which included items about race, ethnicity, education, and reports included raw numbers, percentiles, and graphic rep-

household income. The instrument also included a home resentations of mean hourly AWC and CTC. Intervention-

language survey, which included questions about typical ists discussed with NPCs specific results, methods for

daily schedules, the amount that the child talked, the amount increasing AWC and CTC, and goal setting for upcoming

that NPCs and parents spoke to the child, and the amount of recordings. In addition, NPCs demonstrated ability to accu-

time children were exposed to TV during a typical day. rately interpret and understand feedback at the end of the

interventional session.

Interventionists. Two graduate-level research assistants After the educational intervention, NPCs made record-

involved in the development of the 1-hr educational inter- ings once weekly for 6 weeks and received their LENA

vention performed all interventions. Training and practice feedback results halfway between each recording session.

occurred with the principal investigator (Suskind) prior to No active discussion or goal setting was performed by the

commencement of interventions. interventionist beyond providing the results in paper form.

Recording procedure. At the start of the study, NPCs were

each given a LENA digital language processor designed to Data Processing

be worn by the child in the front pocket of a specially made Data were uploaded from the LENA recorders into a study

t-shirt. At the beginning of each recording day, NPCs wrote computer. All data were then processed into counts by

down the recording start time and then placed on the child LENA ADEX software. Audio recordings were discarded

Downloaded from cdq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 8, 2015

204 Communication Disorders Quarterly 34(4)

to protect the privacy of the participants per IRB-approved Table 3. Family and Nonparental Caregiver Language

research protocol. Language-related outcomes were Characteristics.

assessed on three main measures: AWC, CTC, and child

Self-reported language behaviors n %

vocalization count (CVC). Naptime as well as NPC-child

interaction start and end time parameters were set using the Estimation of time spent conversing with child

information NPCs provided in their initial surveys and on Parent 15 –

their daily recording time sheets. A computer script was Less than average 0 0

written to filter recordings during nap periods. Once fil- Average 1 7

tered, all counts were then standardized by total relevant More than average 11 73

interaction time and were expressed as either words per Much more than average 3 20

hour (wph) or turns per hour (tph). Nonparental caregiver 17 –

Less than average 0 0

Average 7 41

Statistical Analysis More than average 5 29

Much more than average 5 29

Repeated measures ANOVAs were conducted for each of

Estimation of volume of child speech

the four LENA measures (i.e., AWC, CTC, CVC, and TVT),

Parent 16 –

with Time (postintervention Sessions 1, 2, 3 to 6) as the

Less than average 2 12

within-subject variable, to determine whether there were

Average 3 19

significant differences among postintervention recording More than average 7 44

time points. No significant differences were found for any of Much more than average 4 25

the four LENA measures. As such, the counts for each of the Nonparental caregiver 17 –

six postintervention time points were averaged to create a Less than average 0 0

single postintervention score for each of the four LENA Average 7 41

measures. Paired t tests were then carried out to compare the More than average 5 29

pre- and postintervention mean standardized counts. Much more than average 5 29

Estimation of 50 word vocabulary

Parent 16 –

Outcomes and Results Yes 9 56

Home Language Survey No 7 44

Nonparental caregiver 17 –

NPCs and parents were asked to rate the amount that the Yes 12 71

child talked on a 5-point scale from much less than average No 5 29

to much more than average. Their responses are shown in

Table 3, with 10 NPCs (59%) and 11 parents (65%) rating

their children as above-average talkers. When asked how

much they conversed with their child, a majority of parents recordings were made 4.8 days apart on average (SD = 7.5,

(n = 11; 73%) stated they talked to their child more than range = 1–33). Because of the Hawthorne effect, the aver-

average. One parent (7%) rated herself as average. Three age of the two baseline measures was to make pre- and

parents (20%) rated themselves as talking to their child postintervention comparisons (Wolfe & Michaud, 2010).

much more than average. In response to the same question, Indeed, AWC was marginally significantly higher for the

7 NPCs (41%) responded that they talked to the child an first baseline session than for the second (M difference =

average amount, whereas 5 (29%) thought they talked more 413 wph, 28.4%, t = 2.25, p < .04). In contrast, the CTC

than average, and the remaining 5 (29%) reported talking baselines did not differ significantly (M difference = 12

much more than average. tph, 19%, t = 1.64, p < .12) nor did the CVC baselines (M

Overall, NPCs and parents reported low amounts of child difference = 26 vph, 10.4%, t = 1.71, p < .11). The six

television exposure. NPCs reported that the television was on postbaseline recordings were made from 1 to 89 days post-

from 0 to 3 hr per day while they were with the child (M = 0.8 intervention (M = 25 days, SD = 19 days). The average

hr, SD = 0.9 hr). Similarly, parents reported watching 0 to 3 interval between postintervention recordings was 8 days

hr of television per day at home (M = 1.24, SD = 1.02). (SD = 6 days).

TVT overall. The TVT recorded in the child’s aural environ-

LENA Outcome Measures ment during waking hours was low for all children in the

Caregivers contributed two recordings at baseline prior to study, with an average of 22.8 min at baseline (range =

intervention and six postbaseline recordings. Baseline 1–63 min, SD = 16.1 min). Mean amount of TVT did not

Downloaded from cdq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 8, 2015

Suskind et al. 205

Figure 1. Adult word count baseline and postintervention Figure 3. Conversational turn count baseline and

averages in words per hour. postintervention averages in turns per hour.

Figure 2. Adult word count in words per hour at baseline and Figure 4. Conversational turn count in turns per hour at

6 weeks post-intervention. baseline and 6 weeks post-intervention.

differ significantly between baseline and postintervention Conclusion and Implications

recordings (M difference = 0.57 min, 2.5% decrease, t =

0.14, p < .89).

Discussion

The primary goal of our exploratory pilot was to evaluate

AWC overall. As seen in Figure 1, mean AWC from postint- the novel behavior-change strategy of quantitative lin-

ervention recordings was significantly higher than mean guistic feedback and its effect on adult linguistic behav-

AWC at baseline (M difference = 395 wph, 31.6% increase, ior. Our study comprised an initial 1-hr educational

t = 3.29, p < .01). Figure 2 shows AWCs at baseline and at session, six weekly LENA recordings, and the use of

each of the six postintervention sessions. quantitative feedback from those recordings to improve

language outcomes. The significant increases seen in

CTC overall. The mean postintervention CTC was signifi- adult quantitative language output for AWC and CTC

cantly greater than the baseline average, shown in Figure 3 indicate the potential of the quantitative linguistic feed-

(M difference = 14 tph, 24.9% increase, t = 3.54, p < .01). back technique to inform adults to motivate them to

Figure 4 graphs CTCs at baseline and at each of the six modify their interactions with children and provide a

postintervention sessions. richer language environment.

Downloaded from cdq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 8, 2015

206 Communication Disorders Quarterly 34(4)

Pedometers offer a useful analogy for understanding the therapists to gain greater understanding of a family’s base-

quantitative linguistic feedback technique and clarifying its line linguistic style so they can personalize their clinical

impact. Pedometers provide a quantified, easily grasped approach. In addition, the LENA provides ongoing infor-

conceptual framework for behavior change; hence, the mation to therapists with regard to their clients’ therapeutic

health promotion concept of “10,000 steps a day” (Shape uptake. Just as personalized medicine lets oncologists indi-

Up America, Get Up and Go! 10,000 Steps a Day, 1994). vidually adapt therapeutic regimens to specific cancer char-

Behavior-change literature evaluating the pedometer as a acteristics, so also does quantitative linguistic feedback

form of quantitative feedback shows that pedometers have provide insights that help therapists provide the appropriate

been very successful in encouraging sustained physical therapy to each patient.

exercise and movement in all populations, including low- Quantitative linguistic feedback may also be a valuable

income individuals (Clarke et al., 2007; Duru, Sarkisian, tool for the greater scientific community. As Roberts and

Leng, & Mangione, 2010; Strath et al., 2011). Adults are Kaiser (2011) noted, advancing the science of evidence-

rarely conscious of their own “word count,” even if they based behavioral interventions requires transparency of

understand its impact on their children’s development. With strategies used and quantifiable outcome measures of

LENA feedback technology, as with pedometers, they can parental behavioral uptake to quantify intervention dosage.

see the language environment they provide for their child, Quantitative linguistic feedback is a concrete behavioral

begin to understand their critical role, and make appropriate strategy that corroborates fidelity of implementation of

behavioral changes. Although the LENA feedback is not interventional strategies as well as gauges parental behav-

instantaneous like the pedometer, it gives adults unprece- ioral uptake. Although a current limitation of the linguistic

dented insight into and concrete appreciation of their child’s feedback is its lack of qualitative measurement, in future

language environment and overall development. studies, the LENA’s audio recordings may be analyzed for

However, an enriched early language environment qualitative changes as well. This pilot represents only the

requires more than a purely quantitative measure. It is a beginning in the iterative development and testing of this

complex interplay of rich qualitative language and respon- novel multifaceted approach. The results of this study sug-

sive behaviors. Linguistic feedback is designed to signifi- gest that the LENA has the potential to be a valuable addi-

cantly increase adult language quantity to provide a tion to the world of speech and language intervention.

foundation on which qualitative behavioral strategies may

be layered. It is the combination of quantity and quality in a

child’s early language environment that will lead to optimal Considerations

cognitive and educational outcomes. The study was limited in three areas: participant sample,

We view quantitative linguistic feedback not as a “silver potential Hawthorne effect, and variance accounted by the

bullet” but rather as a strategy to increase the effectiveness educational intervention. Although our sample size was

of behavioral interventions. As an effective addition to clin- small, we were encouraged by the ability to demonstrate a

ical therapy sessions, it can provide parents and therapists statistically significant increase in our selected adult lan-

additional proof of behavioral change. Analyses of LENA guage parameters. In addition, caregivers with and without

audio recordings can also provide greater insight into the a college education appeared responsive to the behavioral

qualitative changes. The LENA technology’s ease of use strategy. We plan to investigate with a larger sample size

and automated software processing make it ideal for inclu- the issues of external validity related to the inclusion of

sion in all caregiver-directed interventions involving lan- NPCs as opposed to parents. We hypothesize that parents

guage feedback. Although privacy protections maintained will be more invested and motivated for behavioral change

under IRB protocols for this pilot precluded qualitative when it is their own child who benefits.

analysis by requiring the deletion of audio recordings, An important issue to consider is that of overall linguis-

future projects will include such evaluation. tic implications, in terms of the sustainability of the linguis-

This pilot study has demonstrated the potential of quan- tic behavior change and the true nature of this effect on a

titative linguistic feedback, laying the groundwork for its child’s early language environment. There is the issue of the

continued iterative development as an evidence-based “Hawthorne effect,” which states that individuals positively

behavioral approach. Quantitative linguistic feedback may modify their behavior when they are knowingly being

also have an even greater role in areas such as individual observed. An individual’s knowledge that one is being

therapy. Because of the wide diversity of client populations recorded and will be receiving feedback may result in care-

and the limited insight therapists may have into individual givers increasing linguistic input only during the recording

home environments, they are often forced to use a general- times. Quantitative linguistic feedback will never entirely

ized therapeutic approach rather than one tailored to the avoid this issue, although sustaining increased talk for a

specific family. This is especially true regarding the child’s 10-hr recording day is much less likely than being on best

early home language environment. The LENA may allow behavior during the 1-hr videotaped session typical in most

Downloaded from cdq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 8, 2015

Suskind et al. 207

intervention studies. In addition, the NPCs in our study Ajzen, I. (1996). The directive influence of attitudes on behav-

knew that their employers would not have access to their ior. In P. M. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychol-

results. To address this limitation, future studies will include ogy of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior

greater number of LENA recordings to habituate caregiver (pp. 385–403). New York, NY: Guilford.

response as well as LENA recordings without feedback to Ajzen, I. (2001). Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual Review

assess sustainability of behavioral change. of Psychology, 52, 27–58.

Finally, the 1-hr educational intervention and initial Ajzen, I., Brown, T. C., & Carvajal, F. (2004). Explaining the dis-

baseline LENA feedback were inseparable in this study. We crepancy between intentions and actions: The case of hypo-

are unable to isolate the impact of the LENA feedback from thetical bias in contingent valuation. Personality and Social

the educational session on NPC behavior recorded over the Psychology bulletin, 30, 1108–1121. doi:10.1177/014616720

six remaining recordings. However, the behavioral litera- 426407930/9/1108[pii]

ture has shown that lack of continued feedback results in Bandura, A. (1997). The anatomy of stages of changes. American

attenuation of effect. We suspect that quantitative linguistic Journal of Health Promotion, 12, 8–10.

feedback was responsible for the sustained changes in the Bornstein, M. H., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Hahn, C. S., & Haynes,

AWC and CTC. To address this limitation, in future studies, O. M. (2008). Maternal responsiveness to young children at

we will experimentally manipulate the number of times three ages: Longitudinal analysis of a multidimensional, mod-

caregivers are provided with quantitative linguistic feed- ular, and specific parenting construct. Developmental Psychol-

back after the educational intervention. Future embedding ogy, 44, 867–874. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.867

of quantitative linguistic feedback into established interven- Clarke, K. K., Freeland-Graves, J., Klohe-Lehman, D. M., Milani,

tions, inclusion of a control group and analyses of child out- T. J., Nuss, H. J., & Laffrey, S. (2007). Promotion of physi-

comes will also help address these limitations and confirm cal activity in low-income mothers using pedometers. Jour-

the effects of intervention. nal of the American Dietetic Association, 107, 962–967.

doi:10.1016/j.jada.2007.03.010

DesJardin, J., & Eisenberg, L. S. (2007). Maternal contributions:

Conclusion Supporting language development in young children with

Enhancing a child’s early language environment represents cochlear implants. Ear and Hearing, 28, 456–469. doi:10.1097/

an extraordinary opportunity to affect the life trajectory of AUD.0b013e31806dc1ab00003446-200708000-00004[pii]

a child. Pilot testing of the innovative behavioral strategy— Duru, O. K., Sarkisian, C. A., Leng, M., & Mangione, C. M.

quantitative linguistic feedback—demonstrates its potential (2010). Sisters in motion: A randomized controlled trial of

for stimulating changes in adult language behavior. Because a faith-based physical activity intervention. Journal of the

of these encouraging results, we will continue the develop- American Geriatrics Society, 58, 1863–1869. doi:10.1111/

ment and study of this promising strategy. j.1532-5415.2010.03082.x

Forget-Dubois, N., & Dionne, G. (2009). Early child language

Declaration of Conflicting Interests mediates the relationship between home environment and

The author(s) declared the following potential conflict of interest school readiness. Child Development, 80, 736–749.

with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this Gilkerson, J., & Richards, J. A. (2008). The LENA foundation

article: The LENA recorders used in this study were on loan from natural language study (Tech. Rep). Boulder, CO: The LENA

the LENA Foundation. Foundation.

Giurolametto, L., Weltzman, E., & Greenberg, J. (2003). Training

Funding daycare staff to facilitate children’s language. American Jour-

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support nal of Speech-Language Pathology, 12, 299–311.

for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Giurolametto, L., Weltzman, E., & Greenberg, J. (2004). The effects

authors received internal funding from the Department of Surgery of verbal support strategies on small-group peer interactions. Lan-

at the University of Chicago as well as funding from the Hemera guage, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 35, 254–268.

Foundation. Hagger, M. S., Chatzisarantis, N., & Biddle, S. J. (2001). The

influence of self-efficacy and past behaviour on the physical

Note activity intentions of young people. Journal of Sports Sci-

1. CALO-RE is an acronym for “Coventry, Aberdeen and London ences, 19, 711–725. doi:10.1080/02640410152475847

Refined.” Hammer, J., Tomblin, B., Zhang, X., & Weiss, A. (2001). Rela-

tionship between parenting behaviours and specific language

References impairment in children. International Journal of Language &

Abraham, C., & Michie, S. (2008). A taxonomy of behavior change Communication Disorders, 36, 185–205.

techniques used in interventions. Health Psychology, 27, 379–387. Hart, B., & Risley, T. (1992). American parenting of language

doi:2008-08834-010[pii]10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379 learning children: Persisting differences in family-child inter-

Downloaded from cdq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 8, 2015

208 Communication Disorders Quarterly 34(4)

actions observed in natural home environments. Developmen- Michie, S., Ashford, S., Sniehotta, F. F., Dombrowski, S. U.,

tal Psychology, 28, 1096–1105. Bishop, A., & French, D. P. (2011). A refined taxonomy of

Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the behaviour change techniques to help people change their phys-

everyday experience of young American children. Baltimore, ical activity and healthy eating behaviours: The CALO-RE

MD: Paul H. Brookes. taxonomy. Psychology & Health, 26, 1479–1498. doi:938640

Hoff, E., & Tian, C. (2005). Socioeconomic status and cultural 058[pii]10.1080/08870446.2010.540664

influences on language. Journal of Communication Disorders, Michie, S., Fixsen, D., Grimshaw, J. M., & Eccles, M. P. (2009).

38, 271–278. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2005.02.003 Specifying and reporting complex behaviour change interven-

Hughes, M., & Demo, D. (1989). Self perceptions of black Ameri- tions: The need for a scientific method. Implementation Sci-

cans: Self-esteem and personal efficacy. American Journal of ence, 4, 40. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-4-40

Sociology, 95, 132–159. Michie, S., Jochelson, K., Markham, W. A., & Bridle, C. (2009).

Huttenlocher, J., Haight, W., Selzer, B. A., & Lyons, T. (1991). Low-income groups and behaviour change interventions: A

Early vocabulary growth: Relation to language input and gen- review of intervention content, effectiveness and theoretical

der. Developmental Psychology, 27, 236–248. frameworks. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health,

Huttenlocher, J., Vasilyeva, M., Cymerman, E., & Levine, S. 63, 610–622.

(2002). Language input and child syntax (Research Support, Michie, S., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Lawton, R., Parker, D., &

Non-U.S. Gov’t). Cognitive Psychololgy, 45, 337–374. Walker, A. (2005). Making psychological theory useful for

Individuals With Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004, implementing evidence based practice: A consensus approach.

H.R. 1350, 108th Cong. (2003). BMJ Quality & Safety, 14, 26–33. doi:10.1136/qshc.2004.011155

Janz, N. K., Champion, V. L., & Stretcher, V. J. (2002). The health Michie, S., Johnston, M., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., & Eccles,

belief model. In K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, & F. M. Lewis (Eds.), M. (2008). From theory to intervention: Mapping theoretically

Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change tech-

practice (pp. 45–66). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. niques. Applied Psychology, 57, 660–680. doi:10.1111/j.1464-

Johnston-Brooks, C. H., Lewis, M. A., & Garg, S. (2002). Self- 0597.2008.00341.x

efficacy impacts self-care and HbA1c in young adults with Milburn, T. (2011). The efficacy of a professional development

Type I diabetes. Psychosomatic Medicine Journals, 64, 43–51. program to enhance preschool educators’ ability to facili-

Kaiser, A., & Hancock, T. (2003a). Teaching parents new skills to tate conversation during shared book reading (Master’s the-

support their young children’s development. Infant & young sis). University of Toronto. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.

children, 16, 9–21. net/1807/31341

Kaiser, A., & Hancock, T. (2003b). Teaching parents new skills to Oller, D. K. (2010). All-day recordings to investigate vocabu-

support their young children’s development. Infants & Young lary development: A case study of a trilingual toddler. Com-

Children, 16, 9–21. munication Disorders Quarterly, 31, 213–222. doi:10.1177/

Kashinath, S., Woods, J., & Goldstein, H. (2006). Enhancing gen- 1525740109358628

eralized teaching strategy use in daily routines by parents of Phillips, M. (2011). Parenting, time use, and disparities in aca-

children with autism. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hear- demic outcomes. In G. Duncan & R. Murnane (Eds.), Whither

ing Research, 49, 466–485. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2006/036) opportunity?: Rising inequality schools, and children’s life

Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E., Swank, P. R., & Guttentag, C. chances (pp. 207–228). New York, NY: Russell Sage.

(2008). A responsive parenting intervention: The opti- Pickston, C., Golbart, J., Marshall, J., Rees, A., & Roulstone, S.

mal timing across early childhood for impacting maternal (2009). A systematic review of environmental interventions to

behaviors and child outcomes. Developmental Psychology, improve child language for children with or at risk of primary

44, 1335–1353. language impairment. Journal of Research in Special Educa-

Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E., Swank, P. R., & Miller-Loncar, C. L. tional Needs, 9, 66–79.

(2000). Early maternal and child influences on children’s later Raikes, H., & Thompson, R. A. (2005). Efficacy and social sup-

independent cognitive and social functioning. Child Develop- port as predictors of parenting stress among families in pov-

ment, 71, 358–375. erty. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26, 177–190.

Law, J., & Rush, R. (2009). Modeling developmental language Reese, E., Sparks, A., & Leyva, D. (2010). A review of parent

difficulties from school entry into adulthood: Literacy, mental interventions for preschool children’s language and emergent

health, and employment outcomes. Journal of Speech, Lan- literacy. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 10, 97–117.

guage, and Hearing Research, 52, 1044–1092. Reilly, S., Wake, M., Ukoumunne, O. C., Bavin, E., Prior, M.,

McWilliam, R. A. (2001). Functional intervention planning: The Cini, E., & Bretherton, L. (2010). Predicting language out-

routines-based interview. Retrieved from http://www.wais- comes at 4 years of age: Findings from early language in Victo-

man.wisc.edu/birthto3/WPDP/rbi.pdf ria study. Pediatrics, 126, e1530–e1537. doi:peds.2010-0254

Meadow-Orlans, K. (1997). Effects of mother and infant hearing [pii]10.1542/peds.2010-0254

status on interactions at twelve and eighteen months. Journal Roberts, M. Y., & Kaiser, A. P. (2011). The effectiveness of parent-

of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 2, 26–36. implemented language interventions: A meta-analysis. Ameri-

Downloaded from cdq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 8, 2015

Suskind et al. 209

can Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 180–199. characteristics, selected years 1985-2010. In American’s Chil-

doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0055)1058-0360_2011_10- dren: Key National Indicators of Well-Being 2011. Retrieved

0055[pii] May 3, 2012 from http://childstats.gov/americaschildren/

Rowe, M. L. (2008). Child-directed speech: Relation to socio- tables/fam3a.asp

economic status, knowledge of child development and child Vansteenkiste, M., & Sheldon, K. M. (2006). There’s nothing

vocabulary skill. Journal of Child Language, 35, 185–205. more practical than a good theory: Integrating motivational

Shape up America, Get up and go! 10,000 steps a day. (1994). interviewing and self-determination theory. British Journal of

Retrieved from http://www.shapeup.org/resources/10ksteps.html Clinical Psychology, 45, 63–82.

Snow, C. (1972). Mothers’ speech to children learning language. White, K. M., & Wellington, L. (2009). Predicting participation in

Child Development, 43, 549–565. group parenting education in an Australian sample: The role

Spencer, P., & Gutfreund, M. (1990). Oxford handbook of deaf of attitudes, norms, and control factors. Journal of Primary

studies, language, and education. Washington, DC: Gallaudet Prevention, 30, 173–189.

University Press. Wolf, M., Davis, T., Osborn, C., Skripkauskas, S., Bennett, C.,

Strath, S. J., Swartz, A. M., Parker, S. J., Miller, N. E., Grimm, E. K., & Makoul, G. (2007). Literacy, self-efficacy, and HIV medi-

& Cashin, S. E. (2011). A pilot randomized controlled trial cation adherence. Patient Education and Counseling, 65,

evaluating motivationally matched pedometer feedback to 253–260.

increase physical activity behavior in older adults. Journal of Wolfe, F., & Michaud, K. (2010). The Hawthorne effect, spon-

Physical Activity & Health, 8(Suppl. 2), S267–S274. sored trials, and the overestimation of treatment effectiveness.

Table FAM3.A. Child care: Primary child care arrange- Journal of Rheumatology, 37, 2216–2220. doi:10.3899/jrh

ments for children 0-4 with employed mothers by selected eum.100497

Downloaded from cdq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF WISCONSIN OSHKOSH on June 8, 2015

You might also like

- Case Study 1 Mrs. Hogan AsthmaDocument4 pagesCase Study 1 Mrs. Hogan Asthmaissaiahnicolle100% (2)

- 1622052531342the Life Coachs Content Bible - Sneak PeekDocument14 pages1622052531342the Life Coachs Content Bible - Sneak Peekdawn T100% (4)

- The Empathy Exams Eng 383Document9 pagesThe Empathy Exams Eng 383api-241483370No ratings yet

- McLaughlin Manual ViewDocument88 pagesMcLaughlin Manual Viewnadia Tovar GarciaNo ratings yet

- Comparación de La Efectividad Entre Telepractica y Terapia Presencial en EscolaresDocument6 pagesComparación de La Efectividad Entre Telepractica y Terapia Presencial en EscolaressdanobeitiaNo ratings yet

- Iranian Re v19n3p315 enDocument10 pagesIranian Re v19n3p315 enEmeraldamrNo ratings yet

- Language Intervention Practices For School-Age Children With Spoken Language Disorders: A Systematic ReviewDocument29 pagesLanguage Intervention Practices For School-Age Children With Spoken Language Disorders: A Systematic ReviewCamNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Early Intervention On Awareness and Communication Behaviors of Mothers of Toddlers With Repaired Cleft Lip and PalateDocument6 pagesEffectiveness of Early Intervention On Awareness and Communication Behaviors of Mothers of Toddlers With Repaired Cleft Lip and Palatepico 24No ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of CF en Niños LatinosDocument26 pagesA Systematic Review of CF en Niños LatinosCarmen MirandaNo ratings yet

- Responsivity Education/prelinguistic Milieu Teaching: January 2006Document21 pagesResponsivity Education/prelinguistic Milieu Teaching: January 2006Ana Marta AnastácioNo ratings yet

- Longitudinal Impacts of Print-Focused Read-Alouds For Children With Language ImpairmentDocument14 pagesLongitudinal Impacts of Print-Focused Read-Alouds For Children With Language ImpairmentLuis.fernando. GarciaNo ratings yet

- Colaboración Fono y EducadoresDocument17 pagesColaboración Fono y EducadoresCamii MVNo ratings yet

- J Jfludis 2021 105843Document21 pagesJ Jfludis 2021 105843ANDREA MIRANDA MEZA GARNICANo ratings yet

- Sistema PecDocument13 pagesSistema PecGrethell UrcielNo ratings yet

- OSF FinalDocument38 pagesOSF Finalinas zahraNo ratings yet

- Buschmann2015 PDFDocument15 pagesBuschmann2015 PDFLeisa GviasdeckiNo ratings yet

- Effective Word Reading Instruction What Does The Evidence Tell UsDocument9 pagesEffective Word Reading Instruction What Does The Evidence Tell UsDaniel AlanNo ratings yet

- Functional Communication Abilities in Youth With Cerebral Palsy: Association With Impairment Profiles and School-Based Therapy GoalsDocument17 pagesFunctional Communication Abilities in Youth With Cerebral Palsy: Association With Impairment Profiles and School-Based Therapy Goalskitten 25No ratings yet

- Dennis Et Al 2023 The Effects of Practice Based Coaching On The Implementation of Shared Book Reading Strategies ForDocument16 pagesDennis Et Al 2023 The Effects of Practice Based Coaching On The Implementation of Shared Book Reading Strategies ForxxshellybellxxNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1Document13 pagesJurnal 1deddyNo ratings yet

- Dynamic AssessmentDocument19 pagesDynamic AssessmentbizmutensorceleNo ratings yet

- Teaching by Listening: The Importance of Adult-Child Conversations To Language DevelopmentDocument10 pagesTeaching by Listening: The Importance of Adult-Child Conversations To Language DevelopmentBárbara Mejías MagnaNo ratings yet

- Card On 2017Document20 pagesCard On 2017Andreea Popovici - IşfanNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Intervention For Grammar in School-Aged Children With Primary Language Impairments: A Review of The EvidenceDocument34 pagesEffectiveness of Intervention For Grammar in School-Aged Children With Primary Language Impairments: A Review of The EvidencePaul AsturbiarisNo ratings yet

- Are Communication Interventions Effective ForDocument4 pagesAre Communication Interventions Effective ForvalentinaNo ratings yet

- Safwat-Sheikhany2014 Article EffectOfParentInteractionOnLanDocument9 pagesSafwat-Sheikhany2014 Article EffectOfParentInteractionOnLanAndini PutriNo ratings yet

- 2017 Wales THE EFFICACY OF TELEHEALTH DELIVERED SPEECHDocument16 pages2017 Wales THE EFFICACY OF TELEHEALTH DELIVERED SPEECHpaulinaovNo ratings yet

- Randomized Controlled Trial of An Oral Inferential Comprehension Intervention For DLD - Dawes I Sur - 2019 2Document16 pagesRandomized Controlled Trial of An Oral Inferential Comprehension Intervention For DLD - Dawes I Sur - 2019 2Ana BrankovićNo ratings yet

- Uso Del PECS en AutismoDocument22 pagesUso Del PECS en AutismoPsicoterapia InfantilNo ratings yet

- Chorna Et Al-2017-Developmental Medicine & Child NeurologyDocument6 pagesChorna Et Al-2017-Developmental Medicine & Child NeurologyAnonymous tSBP5QNo ratings yet

- Progress in Understanding Adolescent Language DisordersDocument10 pagesProgress in Understanding Adolescent Language DisordersGabriela Mosqueda CisternaNo ratings yet

- Child Language Assessment Tools: Applicability To HandicappedDocument13 pagesChild Language Assessment Tools: Applicability To Handicappedalibaba1888No ratings yet

- Effects of Collaboration On Language PerformanceDocument8 pagesEffects of Collaboration On Language PerformanceCamila Muñoz VergaraNo ratings yet

- Development of A Parent Report Measure For Profiling The Conversational Skills of Preschool ChildrenDocument9 pagesDevelopment of A Parent Report Measure For Profiling The Conversational Skills of Preschool ChildrenwaakemeupNo ratings yet

- 10.1055@s 0039 1677758Document2 pages10.1055@s 0039 1677758Verónica Gómez LópezNo ratings yet

- PublicationDocument10 pagesPublicationMaggy AstudilloNo ratings yet

- CurtisDocument17 pagesCurtisMarko CrivaroNo ratings yet

- Articulo 3Document35 pagesArticulo 3Daniela Rojas ramirezNo ratings yet

- Language Outcomes in Late-Talkers: Kindergarten: Digitalcommons@ShuDocument7 pagesLanguage Outcomes in Late-Talkers: Kindergarten: Digitalcommons@ShuCeleste StefanoloNo ratings yet

- 14 - Kasari Et Al. (2023)Document11 pages14 - Kasari Et Al. (2023)johnappleseedsmith23No ratings yet

- Training Day Care Staff To Facilitate Children's Language: ResearchDocument13 pagesTraining Day Care Staff To Facilitate Children's Language: ResearchCătălina OlteanuNo ratings yet

- Ashley Drungil - 4-30-17 - MT Synthesis TableDocument6 pagesAshley Drungil - 4-30-17 - MT Synthesis Tableapi-356144133No ratings yet

- Nihms597091 PDFDocument16 pagesNihms597091 PDFHanna RikaswaniNo ratings yet

- A Mis IdolosDocument57 pagesA Mis IdolosAnonymous n3lrZ0gtLNo ratings yet

- Dosen NingDocument21 pagesDosen NingHari HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Intervención Basada en El Juego para Aumentar El VocabularioDocument14 pagesIntervención Basada en El Juego para Aumentar El VocabularioPsicoterapia InfantilNo ratings yet

- Speech-Language Pathologist Interventions For Communication in Moderate-Severe Dementia - A Systematic ReviewDocument17 pagesSpeech-Language Pathologist Interventions For Communication in Moderate-Severe Dementia - A Systematic ReviewCarol TibaduizaNo ratings yet

- A Preliminary Evaluation of Fast ForWord-LanguageDocument30 pagesA Preliminary Evaluation of Fast ForWord-LanguageJavi MoranteNo ratings yet

- Effects in Language Development of Young Children With LanguageDocument12 pagesEffects in Language Development of Young Children With LanguageGautam BehlNo ratings yet

- Hood 2017Document28 pagesHood 2017Leonardo BuenoNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Student Communicative Competence (TASCC) For Grades 1Document10 pagesAssessment of Student Communicative Competence (TASCC) For Grades 1Dwayne Dela VegaNo ratings yet

- Jaba Mand Traning Con SegnoDocument5 pagesJaba Mand Traning Con SegnocassatellaangelaNo ratings yet

- Heilmann, 2014Document15 pagesHeilmann, 2014ClaudiaNo ratings yet

- Retrieve Study PeabodyDocument11 pagesRetrieve Study PeabodyDebbie BenolielNo ratings yet

- Child Care & Early Education: Research ConnectionsDocument17 pagesChild Care & Early Education: Research ConnectionsMasniary HapsariNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Classroom Vocabulary Intervention For Adolescents With Language DisorderDocument24 pagesThe Effectiveness of Classroom Vocabulary Intervention For Adolescents With Language DisorderGabriela Mosqueda CisternaNo ratings yet

- Factores Determinantes en El Desarrollo de Habilidades Auditivas en Ninos HipoacusicosDocument7 pagesFactores Determinantes en El Desarrollo de Habilidades Auditivas en Ninos HipoacusicosRocío AcostaNo ratings yet

- 3 - 2015 Terapia Semantica Lexica NiñosDocument12 pages3 - 2015 Terapia Semantica Lexica Niñosroberthjonathan5No ratings yet

- D.deveney PeterkinDocument16 pagesD.deveney PeterkinJulia Maria Machado RibeiroNo ratings yet

- The Proportion of Minimally Verbal Children With AutismDocument14 pagesThe Proportion of Minimally Verbal Children With AutismLucas De Almeida MedeirosNo ratings yet

- M. Hardin Jones - K. Chapman - 2008Document9 pagesM. Hardin Jones - K. Chapman - 2008guflorencia8No ratings yet

- Language Screening For Infants and Toddlers - A Literature Review of Four Commercially Available Tools (Communication Disorders Quarterly) (2016) PDFDocument10 pagesLanguage Screening For Infants and Toddlers - A Literature Review of Four Commercially Available Tools (Communication Disorders Quarterly) (2016) PDFgangudangNo ratings yet

- Reza Sitinjak CJR COLSDocument5 pagesReza Sitinjak CJR COLSReza Enjelika SitinjakNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Comprehension and Meaning in LanguageFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Comprehension and Meaning in LanguageNo ratings yet

- The PERMA ProfilerDocument48 pagesThe PERMA ProfilerLucky Ade SessianiNo ratings yet

- How Does Gen Z See Its Place in The Working World With TrepidationDocument11 pagesHow Does Gen Z See Its Place in The Working World With TrepidationLucky Ade SessianiNo ratings yet

- Associations Between Child Mobile Use and Digital Parennbdhsbdting Style in Hungarian FamiliesDocument20 pagesAssociations Between Child Mobile Use and Digital Parennbdhsbdting Style in Hungarian FamiliesLucky Ade SessianiNo ratings yet

- What Do Children Think of Their Own Bilingualism? Exploring Bilingual Children's Attitudes and PerceptionsDocument17 pagesWhat Do Children Think of Their Own Bilingualism? Exploring Bilingual Children's Attitudes and PerceptionsLucky Ade SessianiNo ratings yet

- Manolitsi 2011Document18 pagesManolitsi 2011Lucky Ade SessianiNo ratings yet

- Digital Parenting During The COVID-19 Lockdowns: How Chinese Parents Viewed and Mediated Young Children's Digital UseDocument5 pagesDigital Parenting During The COVID-19 Lockdowns: How Chinese Parents Viewed and Mediated Young Children's Digital UseLucky Ade SessianiNo ratings yet

- NG 2020Document26 pagesNG 2020Lucky Ade SessianiNo ratings yet

- Early Language Development and The Emergence of Theory of MindDocument17 pagesEarly Language Development and The Emergence of Theory of MindLucky Ade SessianiNo ratings yet

- 1 Ergonomics Notes 1Document39 pages1 Ergonomics Notes 1musiomi2005No ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Intradialytic Stretching Exercise On Pain Due To Muscle Cramps Among Patients Undergoing HaemodialysisDocument7 pagesEffectiveness of Intradialytic Stretching Exercise On Pain Due To Muscle Cramps Among Patients Undergoing HaemodialysisAhmad IsmailNo ratings yet

- Antiemetic DrugsDocument18 pagesAntiemetic DrugsSuraj VermaNo ratings yet

- Juvenile Delinquency PreventionDocument6 pagesJuvenile Delinquency PreventionJoseph GratilNo ratings yet

- BCKS Tra Vinh - Anh Dau EngDocument4 pagesBCKS Tra Vinh - Anh Dau EngNQTNo ratings yet

- Adv 2020 - PurwantyastutiDocument39 pagesAdv 2020 - PurwantyastutiAsriNurulNo ratings yet

- Engleza Cls A 9 A BDocument4 pagesEngleza Cls A 9 A BAna MariaNo ratings yet

- Optic Disc CuppingDocument14 pagesOptic Disc CuppingAsri Kartika AnggraeniNo ratings yet

- Water Sealed Drainage PDFDocument9 pagesWater Sealed Drainage PDFUlfa FirmaniyahNo ratings yet

- Miller Electric XMT 456CV, XMT 456 CC 280712Document44 pagesMiller Electric XMT 456CV, XMT 456 CC 280712Abdallah MiidouneNo ratings yet

- English 7: Quarter 3 - Module 3Document32 pagesEnglish 7: Quarter 3 - Module 3Monaliza Pawilan100% (4)

- 3 Pressure Ulcer (Bedsores) Nursing Care Plans - NurseslabsDocument12 pages3 Pressure Ulcer (Bedsores) Nursing Care Plans - NurseslabsJOSHUA DICHOSONo ratings yet

- Designing Randomized, Controlled Trials Aimed at Preventing or Delaying Functional Decline and Disability in Frail, Older Persons: A Consensus ReportDocument10 pagesDesigning Randomized, Controlled Trials Aimed at Preventing or Delaying Functional Decline and Disability in Frail, Older Persons: A Consensus ReportLara Correa BarretoNo ratings yet

- World's Most Influential Leaders Inspiring The Business World, 2023 by World's Leaders MagazineDocument48 pagesWorld's Most Influential Leaders Inspiring The Business World, 2023 by World's Leaders MagazineWorlds Leaders MagazineNo ratings yet

- 33conv Inabsentia Reg21Document448 pages33conv Inabsentia Reg21Solo CreatorsNo ratings yet

- JOGCan 2018 Fetal Surveillance A AntepartumDocument21 pagesJOGCan 2018 Fetal Surveillance A AntepartumMiguel Guillermo Salazar ClavijoNo ratings yet

- 3RD-QUARTER-BDC-FINAL (4) (AutoRecovered)Document21 pages3RD-QUARTER-BDC-FINAL (4) (AutoRecovered)Mhelds ParagsNo ratings yet

- Module 9 Personal RelationshipDocument13 pagesModule 9 Personal Relationshipprincess3canlasNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Kesehatan Masyarakat: Relationship Between Smoking and Hereditary With HypertensionDocument7 pagesJurnal Kesehatan Masyarakat: Relationship Between Smoking and Hereditary With HypertensionMade Hendra Satria Nugraha, S.FtNo ratings yet

- Seasonal Variation of Drinking Water Quality in Urban Water Bodies (UWBs) of ChittagongDocument17 pagesSeasonal Variation of Drinking Water Quality in Urban Water Bodies (UWBs) of Chittagongp20190416No ratings yet

- Pornografía en República ChecaDocument7 pagesPornografía en República ChecaCamilo BohórquezNo ratings yet

- Sample Outline of A Case ReportDocument1 pageSample Outline of A Case ReportJAMMENo ratings yet

- PRACTICAL# - 16 Exercise and Breathing RateDocument6 pagesPRACTICAL# - 16 Exercise and Breathing RatetmaddengamingNo ratings yet

- DR Fathema Djan - Materi PERSI V3.1 Final - CompressedDocument40 pagesDR Fathema Djan - Materi PERSI V3.1 Final - CompressedcandraferdianhandriNo ratings yet

- UNIT 2 Module - GE ELEC 7Document20 pagesUNIT 2 Module - GE ELEC 7Brgy Buhang Jaro Iloilo CityNo ratings yet

- CAREvent EMT ManualDocument7 pagesCAREvent EMT ManualMariusz SaskoNo ratings yet