Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Writing Skills Part Lynes

Writing Skills Part Lynes

Uploaded by

Lynes HarefaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Writing Skills Part Lynes

Writing Skills Part Lynes

Uploaded by

Lynes HarefaCopyright:

Available Formats

Writing Skills

Reasons for Writing

At this point it would be helpful to note down your reasons for needing – or wishing

– to write in the course of a typical week, and the form that your writing takes. Try to

think of all possible contexts. Can the kinds of writing you do be grouped together

in any way?

How do you think your own list might compare with that of other people you know:

perhaps a friend who is not a teacher, or your students?

Moreover, in some cases, we ourselves initiate the need to write – different kinds of letters, a

shopping list, or a short story, perhaps – whereas in other cases, the writing is a response to

someone else’s initiation, as when we respond to an invitation or a letter. The final point to

make here is that our writing has different addressees: family, colleagues, friends, ourselves,

officials, students and many more.

Reasons for writing, then, differ along several dimensions, especially those of

language, topic and audience.

Types of writing

Personal writing

Public writing

Creative writing

Social writing

Study writing

Institutional writing

Writing Materials in the Language Class

We have seen in previous chapters that some attention to ‘real-world’ language and

behaviour is regarded as increasingly important in the current English language teaching

climate. It would be difficult to argue the case that writing in the language class should only

mirror the educational function (writing essays and examination answers, taking notes from

textbooks etc.) except perhaps in certain ‘specific-purpose’ programmes such as English for

Specific Purposes (ESP) (e.g. nursing, business) or English for Academic Purposes (EAP). At

the same time, it is not immediately obvious how the notion of ‘authenticity’ and the

opportunities for transfer from real world to classroom can be maintained to the extent that

this can be done for speaking and listening skills.

This brief and generalized summary indicates several trends in the ‘traditional’

teaching of writing from which current views have both developed and moved away:

• There is an emphasis on accuracy.

• The focus of attention is the finished product, whether a sentence or a whole composition.

• The teacher’s role is to be judge of the finished work.

• Writing often has a consolidating function.

Teaching Language Skills

We have listed addressees along with a few suggested topics, but of course the possibilities

are considerably greater than this. Our students, then, can write.

• to other students: invitations, instructions, directions

• for the whole class: a magazine, poster information, a cookbook with recipes from different

countries

• for new students: information on the school and its locality

• to the teacher (not only for the teacher) about themselves and the teacher can reply or

indeed initiate (Hedge, 2005, for example, suggests an exchange of letters with a new class to

get to know them)

• for themselves: lists, notes, diaries (for a fuller discussion of diary writing see Chapter 12)

• to penfriends

• to other people in the school: asking about interests and hobbies, conducting a survey

• to people and organizations outside the school: writing for information, answering

advertisements

• If the school has access to a network of computers, many of these activities can be carried

out electronically as well.

The Writing Process

Hedge (2005) provides a comprehensive range of process-oriented classroom procedures

teachers can make use of. Her book on teaching writing consists of four sections:

Communicating,

Composing,

Crafting and

Improving.

Writing in the classroom

Writing, like reading, is in many ways an individual, solitary activity: the writing

triangle of ‘communicating’, ‘composing’ and ‘crafting’ is usually carried out for an absent

readership.

A few typical examples, all involving oral skills, must suffice:

• ‘Brainstorming’ a topic by talking with other students to collect ideas.

• Co-operating at the planning stage, sometimes in pairs/groups, before agreeing a plan

for the class to work from.

• ‘Jigsaw’ writing, for example, using a picture stimulus for different sections of the

class to create a different part of the story (Hedge, 2005: 40–2).

• Editing another student’s draft.

• Preparing interview questions, perhaps for a collaborative project.

You might also like

- The Writing InstructionDocument4 pagesThe Writing InstructionQuennieNo ratings yet

- TILS Week5WritingDocument37 pagesTILS Week5WritingelaltmskrNo ratings yet

- Language Learning Materials DevelopmentDocument22 pagesLanguage Learning Materials DevelopmentPRINCESS JOY BUSTILLO100% (1)

- TFCDocument8 pagesTFCCut Balqis PutriNo ratings yet

- Product and Process WritingDocument4 pagesProduct and Process WritingStella María Caramuti PiccaNo ratings yet

- Teaching WritingDocument4 pagesTeaching Writingdiazjanice.fNo ratings yet

- Jeremy Harmer - Teaching Writing ETpDocument3 pagesJeremy Harmer - Teaching Writing ETpFatima Abdallah Fiore100% (2)

- Effective Writing Assignments: Write To Learn ActivitiesDocument11 pagesEffective Writing Assignments: Write To Learn Activitiesashok kumarNo ratings yet

- Writing: "Writing Is Its Own Reward."Document9 pagesWriting: "Writing Is Its Own Reward."Froilan J. AguringNo ratings yet

- Narratives About Teaching WritingDocument41 pagesNarratives About Teaching WritingBlas BigattiNo ratings yet

- Friese LLED 4120 Sp11 8amDocument7 pagesFriese LLED 4120 Sp11 8amelizfrieseNo ratings yet

- Writing HandoutDocument2 pagesWriting HandoutWan MaisarahNo ratings yet

- T A MacroskillDocument36 pagesT A Macroskillengkeechangrapen12No ratings yet

- Developing Writing Skills in Teaching Foreign LanguagesDocument3 pagesDeveloping Writing Skills in Teaching Foreign Languagesakenjayev2No ratings yet

- A Lesson Plan For Teaching Writing SkillsDocument4 pagesA Lesson Plan For Teaching Writing SkillsLuanaNo ratings yet

- Planning A Writing Lesson - TeachingEnglish - British Council - BBCDocument4 pagesPlanning A Writing Lesson - TeachingEnglish - British Council - BBCHanif MohammadNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3Document10 pagesLesson 3Robs Tuella DelacruzNo ratings yet

- WritingDocument3 pagesWritingعماد عبد السلامNo ratings yet

- The Writing Difficulties Faced by L2 Learners and How To Minimize ThemDocument8 pagesThe Writing Difficulties Faced by L2 Learners and How To Minimize ThemNuru JannahNo ratings yet

- Teaching WritingDocument72 pagesTeaching Writingmari100% (2)

- Teaching Writing Through LiteratureDocument9 pagesTeaching Writing Through LiteratureSamori Camara100% (1)

- Take Five! for Language Arts: Writing that builds critical-thinking skills (K-2)From EverandTake Five! for Language Arts: Writing that builds critical-thinking skills (K-2)No ratings yet

- Writing For Specific Purposes.1Document26 pagesWriting For Specific Purposes.1Ricardo Sage2 HarrisNo ratings yet

- Planning A Writing LessonDocument9 pagesPlanning A Writing LessonZaleha AzizNo ratings yet

- AP SyllabusDocument3 pagesAP SyllabusMichael EdlerNo ratings yet

- 06 Teaching WritingDocument29 pages06 Teaching WritingGab Gapas100% (1)

- Teaching Writing and ReadingDocument14 pagesTeaching Writing and Readinganon_577116493No ratings yet

- Communicative Language TeachingDocument8 pagesCommunicative Language TeachingNgoc YenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Teaching Writing in The Elementary GradesDocument8 pagesChapter 3 Teaching Writing in The Elementary GradesMedz Legaspi BilaroNo ratings yet

- Ed 579064Document34 pagesEd 579064Denzel WhataNo ratings yet

- Study Writing Introduction StudentDocument2 pagesStudy Writing Introduction StudentDimitrije Bujakovic100% (1)

- Planning A Writing LessonDocument3 pagesPlanning A Writing LessonDina MylonaNo ratings yet

- Writing Skills AssignmentDocument10 pagesWriting Skills Assignmentpandreop100% (2)

- Academic WritingDocument9 pagesAcademic Writingmaricel ubaldoNo ratings yet

- How To Teach Writing Skills To ESL and EFL StudentsDocument7 pagesHow To Teach Writing Skills To ESL and EFL StudentsMaria Elena Mora MejiaNo ratings yet

- Product and Process WritingDocument5 pagesProduct and Process WritingAmna iqbalNo ratings yet

- What Is Writing?: Considerations For Teaching WritingDocument2 pagesWhat Is Writing?: Considerations For Teaching WritingІринаNo ratings yet

- Writing PresentationDocument33 pagesWriting Presentationشادي صابرNo ratings yet

- Week 6 Approaches For Teaching Writing - Week 6 - 2018 - TSLB 3073 FRM Kak RuziahDocument38 pagesWeek 6 Approaches For Teaching Writing - Week 6 - 2018 - TSLB 3073 FRM Kak RuziahXin EnNo ratings yet

- ROLE OF TEACHER IN WRITING SKILLS (Nimra Ishfaq 1316)Document9 pagesROLE OF TEACHER IN WRITING SKILLS (Nimra Ishfaq 1316)GoharAwan100% (1)

- Insight Paper. TRENDS in WRitingDocument5 pagesInsight Paper. TRENDS in WRitingMa CorNo ratings yet

- Coursework BooksDocument7 pagesCoursework Bookstvanfdifg100% (2)

- How To Teach Writing in EFL and ESL ClassroomsDocument8 pagesHow To Teach Writing in EFL and ESL ClassroomsMayra MartinezNo ratings yet

- 540 SyllabusDocument8 pages540 Syllabusapi-310543789No ratings yet

- Methodology 8writingDocument17 pagesMethodology 8writingogasofotiniNo ratings yet

- Week 1Document32 pagesWeek 1Codds 45No ratings yet

- Teaching Academic English Writing SkillsDocument5 pagesTeaching Academic English Writing SkillsSevan Arzrouny GhazarianNo ratings yet

- PPP Week 1Document24 pagesPPP Week 1api-649700352No ratings yet

- WRITINGDocument2 pagesWRITINGsnowpieceNo ratings yet

- Click Icon To Add Picture: How To Teach Writing Skill To Young Learners Burcu Mali 21494711Document16 pagesClick Icon To Add Picture: How To Teach Writing Skill To Young Learners Burcu Mali 21494711Burcu MaliNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Process Writing - Teachingenglish - Org.ukDocument4 pagesApproaches To Process Writing - Teachingenglish - Org.ukciorapelaNo ratings yet

- 3 Process WritingDocument8 pages3 Process WritingOzjosh Torres VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Teachingwritingtoyounglearners 150403112327 Conversion Gate01Document12 pagesTeachingwritingtoyounglearners 150403112327 Conversion Gate01samrand aminiNo ratings yet

- 09 20writing Assessment 20v001 20 (Full)Document45 pages09 20writing Assessment 20v001 20 (Full)Sivarasu Siddhan100% (1)

- Reconsidering ReadingDocument9 pagesReconsidering ReadingCram Xap OrtilepNo ratings yet

- Article 02Document10 pagesArticle 02Felipe TótoraNo ratings yet

- Module 14 Teaching WritingDocument12 pagesModule 14 Teaching WritingJana VenterNo ratings yet

- ELTC PPT by Group 4Document31 pagesELTC PPT by Group 4Lynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- B-Iv Lynes Andika Harefa-Cjr EltmmDocument8 pagesB-Iv Lynes Andika Harefa-Cjr EltmmLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- Writing TEFL Lynes Andika HarefaDocument6 pagesWriting TEFL Lynes Andika HarefaLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

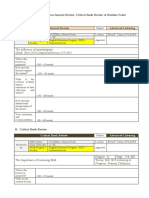

- The Form of Critical Journal Review and Critical Book ReviewDocument3 pagesThe Form of Critical Journal Review and Critical Book ReviewLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- B-3 Lynes Andika Harefa - Adavanced ReadingDocument20 pagesB-3 Lynes Andika Harefa - Adavanced ReadingLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- CJR LISTENING-Lynes Andika HarefaDocument2 pagesCJR LISTENING-Lynes Andika HarefaLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- CJR PUBLIC SPEAKING-Lynes Andika HarefaDocument4 pagesCJR PUBLIC SPEAKING-Lynes Andika HarefaLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- A Game lynes-WPS Office-1Document2 pagesA Game lynes-WPS Office-1Lynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- CJR Translation LynesDocument7 pagesCJR Translation LynesLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- ContentDocument4 pagesContentLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- Content-1Document10 pagesContent-1Lynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- CBR Translation LynessDocument6 pagesCBR Translation LynessLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- Lynes HarDocument2 pagesLynes HarLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- Isbd Bab ViiiDocument12 pagesIsbd Bab ViiiLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- Adjective ClausesDocument15 pagesAdjective ClausesLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- CJR Translation RiattaDocument8 pagesCJR Translation RiattaLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- CBR Translation LynessDocument6 pagesCBR Translation LynessLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- A Game lynes-WPS OfficeDocument2 pagesA Game lynes-WPS OfficeLynes HarefaNo ratings yet

- Tom Is From Berlin. His Nationality Is - A. Germany B. German C. Dutch 2. Anna Is From Leningrad. Her Nationality Is - A. France B. French C. RussianDocument5 pagesTom Is From Berlin. His Nationality Is - A. Germany B. German C. Dutch 2. Anna Is From Leningrad. Her Nationality Is - A. France B. French C. RussianFátima MartinsNo ratings yet

- L3 - As4 Eng 103Document5 pagesL3 - As4 Eng 103gt211No ratings yet

- Gold Experience A2 Exam 3 A21Document3 pagesGold Experience A2 Exam 3 A21Esther Rivero RamírezNo ratings yet

- PC The 4 Group 7 ReportDocument75 pagesPC The 4 Group 7 ReportPrincess Mae BaldoNo ratings yet

- The Fifth Meeting Online, Passive VoiceDocument7 pagesThe Fifth Meeting Online, Passive VoiceAnnisa Farah DhibaNo ratings yet

- Guide On Composition WritingDocument9 pagesGuide On Composition WritingSjr RushNo ratings yet

- How To Speak English Well: 10 Simple Tips To Extraordinary FluencyDocument3 pagesHow To Speak English Well: 10 Simple Tips To Extraordinary FluencyRifNo ratings yet

- (FA1FORMATIVE) Introduction To Database DesignDocument5 pages(FA1FORMATIVE) Introduction To Database Designwikan onalanNo ratings yet

- A-Parts-Of-Speech PDCS1Document26 pagesA-Parts-Of-Speech PDCS1kunalsingh12340% (1)

- Body Language: Lingua House Lingua HouseDocument4 pagesBody Language: Lingua House Lingua HousediogofffNo ratings yet

- Forensic Discourse AnalysisDocument7 pagesForensic Discourse AnalysisBensalem ImeneNo ratings yet

- Pronoun NounDocument21 pagesPronoun NounSabil SabilNo ratings yet

- Transitional Words Worksheet PDFDocument1 pageTransitional Words Worksheet PDFPaula RamirezNo ratings yet

- FullDocument338 pagesFullBrittney ShazierNo ratings yet

- Chuyên Đề 5: Thể Giả ĐịnhDocument10 pagesChuyên Đề 5: Thể Giả ĐịnhThy AnhNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan SituationalDocument2 pagesLesson Plan Situationalafrasayab mubeenaliNo ratings yet

- St. Louis College of Bulanao: General Intruction/SDocument34 pagesSt. Louis College of Bulanao: General Intruction/SJonalyn AcobNo ratings yet

- Tugas Kelompok 8 (Tugas Akhir Semester) DI EDITDocument54 pagesTugas Kelompok 8 (Tugas Akhir Semester) DI EDITHazmi SidiqNo ratings yet

- Danae Coetzees Quiz History Quiz 3Document4 pagesDanae Coetzees Quiz History Quiz 3api-327895548No ratings yet

- T3. Gerunds and InfinitivesDocument4 pagesT3. Gerunds and InfinitivesalejandraNo ratings yet

- Pragmatics 7 Outline: A. Recap B. Conceptual Metaphors C. Classification of Metaphors A. RecapDocument6 pagesPragmatics 7 Outline: A. Recap B. Conceptual Metaphors C. Classification of Metaphors A. RecapIvona TudoseNo ratings yet

- Module 7 Stylistics and Discourse AnalysisDocument41 pagesModule 7 Stylistics and Discourse AnalysisPrincess PortezaNo ratings yet

- OutlineDocument35 pagesOutlineShanaNo ratings yet

- BC AnswersDocument12 pagesBC AnswersJe RomeNo ratings yet

- English Grammar - EllipsisDocument2 pagesEnglish Grammar - EllipsisChiby MirikitufuNo ratings yet

- SJK Year 5 CEFR Unit 7 GROWING UPDocument16 pagesSJK Year 5 CEFR Unit 7 GROWING UPKARPAGAM A/P NAGAPPAN MoeNo ratings yet

- Adverb Hard PDFDocument3 pagesAdverb Hard PDFBustami Muhammad Sidik100% (1)

- The Continuous AspectDocument2 pagesThe Continuous Aspectetna26No ratings yet

- W 24 Test Units 13-16Document3 pagesW 24 Test Units 13-16Mada TuicaNo ratings yet

- The SemicolonDocument5 pagesThe SemicolonPiyush HarlalkaNo ratings yet