Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pedi 2019 33 425

Pedi 2019 33 425

Uploaded by

Adisty DokiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pedi 2019 33 425

Pedi 2019 33 425

Uploaded by

Adisty DokiCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Personality Disorders, 34, Supplement B , 17–24, 2020

© 2020 The Guilford Press

RISK FACTORS FOR BORDERLINE

PERSONALITY DISORDER IN ADOLESCENTS

Mary C. Zanarini, EdD, Christina M. Temes, PhD,

Laura R. Magni, PhD, Blaise A. Aguirre, MD,

Katherine E. Hein, MHS, and Marianne Goodman, MD

The objective of this study was to assess the association between variables

reflecting childhood adversity, protective childhood experiences, and the

five-factor model of personality and BPD in adolescents. Two groups

of adolescents were studied: 104 met criteria for BPD and 60 were

psychiatrically healthy. Adverse and protective childhood experiences

were assessed using a semistructured interview. The five-factor model

of personality was assessed using the NEO-FFI. Eight of nine variables

indicating severity of abuse and neglect, positive childhood relationships,

childhood competence, and the personality factors studied were found

to be significant bivariate risk factors for adolescent BPD. However, in a

multivariate model, severity of neglect, higher levels of neuroticism, and

lower levels of childhood competence were found to be the best risk factor

model. Taken together, the results of this study suggest that all three types

of risk factors studied are significantly associated with BPD in adolescents.

Keywords: borderline personality disorder, childhood abuse, childhood

neglect, positive relationships, competence, personality traits, risk factors,

adolescents

Research regarding the etiology of borderline personality disorder (BPD) in

adults has primarily focused on the role of adverse childhood experiences.

Both multiple forms of abuse (Herman, Perry, & van der Kolk, 1989; Links,

Steiner, Offord, & Eppel, 1988; Ogata et al., 1990; Paris, Zweig-Frank, &

Guzder, 1994a; Paris, Zweig-Frank, & Guzder, 1994b; Salzman et al., 1993;

Shearer, Peters, Quaytman, & Ogden, 1990; Zanarini, Gunderson, Franken-

burg, & Chauncey, 1989; Zanarini et al., 1997) and emotional neglect (Links

et al., 1988; Zanarini et al., 1989; Zanarini et al., 1997) have been found to

be more common among adults with BPD than comparison subjects with a

variety of diagnoses (e.g., depression, personality disorders other than BPD). A

smaller number of studies found the same pattern in adolescents (Atlas, 1995;

From McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

(M. C. Z., C. M. T., B. A. A.); McLean Hospital (K. E. H.); St. John of God Research Centre, Brescia, Italy

(L. R. M.); and James J. Peters Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Bronx, New York, and Icahn School of

Medicine at Mt. Sinai, New York, New York (M. G.).

This research was supported by NIMH grants MH47588 and MH62169 (Dr. Zanarini).

Address correspondence to Dr. Mary C. Zanarini, McLean Hospital, 115 Mill St., Belmont, MA 02478.

E-mail: zanarini@mclean.harvard.edu

G4884.indd 17 9/23/2020 12:32:46 PM

18 ZANARINI ET AL.

Horesh, Ratner, Laor, & Toren, 2008; Horesh, Sever, & Apter, 2003; Infurna

et al., 2016; James, Berelowitz, & Vereker, 1996; Stepp, Whalen et al., 2014;

Westen, Ludolph, Misle, Ruffins, & Block, 1990).

In contrast, little research has been conducted on competence and other

protective factors that may serve to lessen the severity of these symptoms in

both adults (Skodol et al., 2007) and adolescents with BPD (Borkum et al.,

2017). In addition to these studies of adverse childhood experiences and pro-

tective childhood experiences, numerous studies have found a strong associa-

tion between five factor traits, particularly Neuroticism, and the presence of

BPD or BPD symptoms in adults (e.g., Hopwood et al., 2009). In addition, a

smaller body of research has found this same association in adolescents (Stepp,

Keenan, Hipwell, & Krueger, 2014).

Most of the studies mentioned above are descriptive in nature. However,

studies in the field of child development suggest a more complicated model

between these adverse and protective factors and aspects of temperament.

More specifically, they suggest that temperament moderates the effects of

parenting efforts, particularly for children with a highly reactive phenotype

(Boyce & Ellis, 2005; Pluess & Belsky, 2010).

The current study has two main aims, the results of which will fill a gap

in the literature concerning the risk factors for BPD in adolescents. First, it will

assess the risk associated with the severity of two adverse childhood factors

(abuse and neglect), two protective childhood factors (number of emotionally

sustaining relationships and childhood competence), and the five factors of

personality in adolescents with BPD and a psychiatrically healthy comparison

group. These analyses will be both bivariate and multivariate in nature. Second,

this study will assess the role of temperament in moderating the effects of child-

hood adversity and protective factors in the development of BPD in adolescents.

METHOD

The methodology of this study has been presented before in detail (Zanarini

et al., 2017). All study procedures were approved by the institutional review

boards at the participating institutions.

Adolescents (aged 13–17) with presumptive BPD were recruited from four

units at McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts, and one unit at Mount

Sinai Medical Center, Bronx, New York, between August 2007 and September

2012. During the same time frame, same-aged adolescents without a history

of any psychiatric disorder were recruited using online advertisements. Parents

provided consent and adolescents provided assent. The adolescents were then

interviewed using the following diagnostic interviews: (1) the Structured Clini-

cal Interview for DSM-IV Childhood Diagnoses (KID-SCID; Matzner, Silva,

Silvan, Chowdhury, & Nastari, 1997); (2) the Revised Diagnostic Interview

for Borderlines (DIB-R; Zanarini, Gunderson, Frankenburg, & Chauncey,

1989); and (3) the Childhood Interview for DSM-IV Borderline Personality

Disorder (CI-BPD; Sharp, Ha, Michonski, Venta, & Carbone, 2012).

Inclusion in the borderline group of adolescents required meeting DIB-R

and DSM-IV criteria for BPD. In addition, all forms of comorbidity were

G4884.indd 18 9/23/2020 12:32:46 PM

RISK FACTORS FOR BPD IN ADOLESCENTS 19

allowed except for schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar I dis-

order. The psychiatric comparison subjects were only included in the study if

they did not meet lifetime criteria for any psychiatric disorder.

To assess adverse and protective childhood experiences reported to have

occurred before age 18, all participants were administered the Revised Child-

hood Experiences Questionnaire (CEQ-R). The CEQ-R is a semistructured

interview whose psychometric properties have been described elsewhere

(Zanarini, Gunderson, Marino et al., 1989). This instrument assesses four

forms of abuse and seven forms of neglect by full-time caretakers of both

genders (typically parents) and additionally, sexual abuse by non-caretakers

of both genders (e.g., siblings, neighbors). It also assesses five types of emo-

tionally supportive relationships (e.g., male and female friends and siblings)

and eight types of childhood competence, such as academic success, athletic

success, and popularity. For each type of experience, interviewers record a

dichotomous rating to indicate the presence or absence of the experience

during three periods in the participants’ childhood: 0–5 years of age, 6–12

years of age, and 13–17 years of age. For an item to be given a positive (pres-

ent) rating, participants must provide detailed information about the event.

This instrument also yields two continuous scores for childhood adversity

(abuse and neglect) and two continuous scores for protective childhood

experiences (positive relationships and childhood competence). These scores

are derived by summing the total number of affirmative ratings for each type

of experience across each age period and emotionally important adult (for

childhood adversity). For example, the maximum severity score for neglect

is 42, because the presence/absence of seven different neglect experiences

is assessed for three age periods and two caretakers, typically a subject’s

mother and father. A similar scoring system was used for the five forms

of emotionally supportive relationships and the eight types of childhood

competence studied.

Participants then took the NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI; Costa

& McCrae, 1992), a 60-item self-report measure with proven psychometric

properties. Each of the five factors was assessed with 12 items scored on a

five-point Likert rating scale. Reported t scores generally range from 20 to

80, with 50 being the median score.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Between-group differences in demographic variables were assessed using Stu-

dent’s t test for continuous variables and Pearson chi-square for binary variables.

Analyses of the severity of childhood adversity, childhood protective factors,

and NEO scores were conducted using logistic regression controlling for age,

and significance was adjusted for multiple comparisons to p < .006 (.05/9).

We also conducted exploratory logistic regression analyses to assess the

role of neuroticism as a moderator of the effects of the two childhood adversity

variables and two childhood protective factors on risk of developing BPD.

We hypothesized that higher levels of neuroticism will magnify the effects of

adverse life experiences and attenuate the effects of protective life experiences.

G4884.indd 19 9/23/2020 12:32:46 PM

20 ZANARINI ET AL.

RESULTS

PARTICIPANTS

One hundred and four participants were adolescents between the ages of 13

and 17 who met DIB-R and DSM-IV criteria for BPD. Sixty were psychiatri-

cally healthy comparison subjects in the same age range. We chose to study

these groups, as many clinicians do not believe that BPD can be fully present in

adolescence and many mental health professionals believe that BPD symptoms

in adolescence are only a manifestation of normal adolescence.

Demographic characteristics have also been described previously

(Zanarini et al., 2017). Briefly, adolescents with BPD were significantly more

likely to be female than psychiatrically healthy adolescents. However, ado-

lescents with BPD were very similar to psychiatrically healthy adolescents

in terms of race (about a third non-white) and socioeconomic background

(mean of about 2.3/2.4 on a 1 = highest and 5 = lowest scale). In addition,

adolescents with BPD were significantly older than psychiatrically healthy

adolescents (by about a year—15 vs. 14).

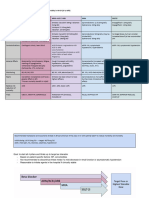

Table 1 details the mean scores on nine variables as well as their stan-

dard deviations in logistic regression models taking each variable in turn. All

between-group differences were significant at the p < .05 level. More specifi-

cally, borderline adolescents had significantly higher scores on the severity of

childhood abuse and neglect as well as the Neuroticism and Openness factors

from the NEO. They also had significantly lower scores on the NEO’s Extra-

version factor, Agreeableness factor, and Conscientiousness factor as well as

TABLE 1. Bivariate Risk Factors for the Development of BPD in Adolescents

Psychiatrically

Adolescent BPD Healthy Adolescents Adolescent BPD vs. Healthy Adolescents

Mean SD Mean SD Odds Ratio z value p value 95% CI

Childhood Adversity

Severity of Abuse (0–30) 2.4 3.3 0.2 0.8 2.74 3.91 < .001 1.65, 4.53

Severity of Neglect (0–42) 5.6 6.7 0.4 1.3 1.84 4.32 < .001 1.40, 2.44

NEO Five Factors

Neuroticism Factor 68.9 7.2 48.6 9.2 1.27 6.21 < .001 1.18, 1.37

Extraversion Factor 46.6 12.2 56.9 9.2 0.97 -4.17 < .001 0.90, 0.96

Openness Factor 54.2 11.2 49.4 10.2 1.03 2.06 .039 1.00, 1.07

Agreeableness Factor 39.9 11.9 52.3 11.7 0.91 -5.27 < .001 0.88, 0.94

Consciousness Factor 34.5 10.9 45.9 10.9 0.92 -4.96 < .001 0.89, 0.95

Positive Childhood

Experiences

Number of Supportive 11.5 5.4 17.1 5.6 0.82 -5.00 < .001 0.77, 0.89

Relationships (0–30)

Degree of Childhood 8.6 4.0 13.8 3.9 0.72 -5.86 < .001 0.64, 0.80

Competence (0–24)

Note. Analyses controlled for age and significance were p < .006.

G4884.indd 20 9/23/2020 12:32:46 PM

RISK FACTORS FOR BPD IN ADOLESCENTS 21

significantly lower scores on the number of positive childhood relationships

and the degree of childhood competence. However, at the Bonferroni corrected

level of p < .006, Openness was no longer significant.

We next tested the significance of the mean scores of the eight variables

that were significant in bivariate analyses. Three of these variables were found

to be significant as a model of risk factors for BPD in adolescents (see Table 2).

These variables are: severity of childhood neglect, higher Neuroticism score,

and lower level of childhood competence.

Our exploratory analyses of the moderating effects of neuroticism did

yield a significant interaction between neuroticism and severity of neglect but

no significant interactions with the other three risk-protective factors. How-

ever, counter-intuitively and not supportive of our hypothesis, this interaction

indicated that higher levels of neuroticism attenuate the effect of adverse

life experiences. Specifically, the odds ratio for severity of neglect was 1.85

(z = 3.42, p = .001, 95% CI [1.30, 2.63]) for those with higher levels of neu-

roticism (1 SD above the t score mean for levels of Neuroticism) whereas the

odds ratio was 4.34 (z = 3.27, p = .001, 95% CI [1.80, 10.47]) for those with

lower levels of Neuroticism (1 SD below the t score mean).

DISCUSSION

Three main findings emerge from the results of this cross-sectional study. First,

the severity of childhood neglect (mostly emotional in nature) has been found

to be a significant multivariate risk factor for the development of adolescent

BPD. This finding is consistent with the results of adult studies of childhood

adversity, which have found that emotional neglect is more strongly associ-

ated with BPD in adults than the severity of childhood abuse (Zanarini et al.,

1997). However, many clinicians believe that childhood abuse, particularly

sexual abuse, is the most important factor in the etiology of BPD. The severity

of abuse was significant in bivariate but not multivariate analyses, suggesting

that clinicians would be wise to consider a broader array of possible etiologi-

cal factors than childhood sexual abuse.

Second, heightened neuroticism was found to be a significant multivariate

risk factor for BPD in adolescents. Previous studies of adults and adolescents

with BPD have also found this relationship between the personality trait of

negative emotions and BPD (Hopwood et al., 2009; Stepp et al., 2014). This

TABLE 2. Significant Multivariate Risk Factors for the Development of BPD in Adolescents

Risk Factor Odds Ratio z score p value 95% CI

Severity of Childhood Neglect 1.71 3.00 .003 1.21, 2.44

Level of Neuroticism 1.30 4.28 < .001 1.15, 1.46

Degree of Childhood Competence 0.67 -3.74 < .001 0.54, 0.83

Note. Analyses controlled for age and significance were p < .006.

G4884.indd 21 9/23/2020 12:32:46 PM

22 ZANARINI ET AL.

association is not surprising given the multiple dysphoric states (inappropriate

anger and chronic feelings of emptiness) that are part of the DSM-IV criteria

set for BPD. It is also not surprising given the fact that this criteria set includes

affective instability (i.e., the rapid movement from one dysphoric affective state

to another). As for the other factors, they confirm the results of earlier studies

in adults (Morey et al., 2002). More specifically, Extraversion, Agreeableness,

and Conscientiousness were found to be relatively low in those with BPD and

Openness was found to be relatively high.

Third, the results of this study indicate that a more limited degree of

childhood competence spanning eight factors is also a significant multivariate

risk factor for BPD in adolescents. It may be that emotional neglect by parents

and a high degree of trait negative emotionality join to affect the degree of

childhood competence that those with BPD as adolescents manifest. It may

also be that being less competent than psychiatrically healthy adolescents joins

with trait neuroticism to make adolescents with BPD more susceptible to the

effects of parental emotional neglect.

Taken together, the results of this study are consistent with studies of child

development, which suggest that temperament moderates the effects of parenting

efforts (Boyce & Ellis, 2005; Pluess & Belsky, 2010). However, the significant

moderating effect of Neuroticism that we found is in the opposite direction to

what was hypothesized; as a result, we strongly caution against overinterpreting

this result until it has been replicated in another study or independent dataset.

LIMITATIONS

One limitation of the current study is that all adolescents with BPD were

inpatients. Thus, our results may not generalize to adolescents with less severe

psychopathology. Another is that our healthy adolescents had no history of

any psychiatric disorder. Thus, our results may not generalize to community-

dwelling adolescents with one or more lifetime psychiatric disorders.

CONCLUSIONS

Taken together, the results of this study suggest that all three types of risk

factors studied are significantly associated with BPD in adolescents. They also

suggest that the severity of childhood neglect, the personality trait of Neuroti-

cism, and lower levels of childhood competence are more strongly associated

with BPD in adolescence than the severity of childhood abuse.

REFERENCES

Atlas, J. A. (1995). Association between history of Zanarini, M. C. (2017). Prevalence rates of

abuse and borderline personality disorder for childhood protective factors in adolescents

hospitalized adolescent girls. Psychological with BPD, psychiatrically healthy adoles-

Reports, 77(Suppl. 3), 1346. https://doi. cents, and adults with BPD. Personal Mental

org/10.2466/pr0.1995.77.3f.1346 Health, 11, 189–194.

Borkum, D. B., Temes, C. M., Magni, L. R., Fitzmau- Boyce, W. T., & Ellis, B. J. (2005). Biological sensitivity

rice, G. M., Aguirre, B. A., Goodman, M., & to context: I. An evolutionary-developmental

G4884.indd 22 9/23/2020 12:32:46 PM

RISK FACTORS FOR BPD IN ADOLESCENTS 23

theory of the origins and functions of stress sexual and physical abuse in adult patients

reactivity. Development and Psychopathol- with borderline personality disorder. Amer-

ogy, 17, 271–301. ican Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 1008–

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO 1013. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.147.8

Personality Inventory and NEO Five-Factor .1008

Inventory Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Paris, J., Zweig-Frank, H., & Guzder, J. (1994a).

Psychological Assessment Resources. Psychological risk factors for borderline per-

Herman, J. L., Perry, J. C., & van der Kolk, B. A. sonality disorder in female patients. Compre-

(1989). Childhood trauma in borderline hensive Psychiatry, 35, 301–305.

personality disorder. American Journal of Paris, J., Zweig-Frank, H., & Guzder, J. (1994b).

Psychiatry, 146, 490–495. https://doi.org/ Risk factors for borderline personality in

10.1176/ajp.146.4.490 male outpatients. Journal of Nervous and

Hopwood, C. J., Newman, D. A., Donnellan, M. Mental Disease, 182, 375–380.

B., Markowitz, J. C., Grilo, C. M., Sanislow, Pluess, M., & Belsky, J. (2010). Differential suscep-

C. A., . . . Morey, L. C. (2009). The stabil- tibility to parenting and quality child care.

ity of personality traits in individuals with Developmental Psychology, 46, 379–390.

borderline personality disorder. Journal of Salzman, J. P., Salzman, C., Wolfson, A. N., Albanese,

Abnormal Psychology, 118(4), 806–815. M., Looper, J., Ostacher, M., . . . Miyawaki,

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016954. E. (1993). Association between borderline

Horesh, N., Ratner, S., Laor, N., & Toren, P. (2008). personality structure and history of child-

A comparison of life events in adolescents hood abuse in adult volunteers. Comprehen-

with major depression, borderline person- sive Psychiatry, 34, 254–257.

ality disorder and matched controls: A Sharp, C., Ha, C., Michonski, J., Venta, A., & Car-

pilot study. Psychopathology, 41, 300–306. bone, C. (2012). Borderline personality dis-

https://doi.org/10.1159/000141925 order in adolescents: Evidence in support of

Horesh, N., Sever, J., & Apter, A. (2003). A compari- the Childhood Interview for DSM-IV Bor-

son of life events between suicidal adoles- derline Personality Disorder in a sample of

cents with major depression and borderline adolescent inpatients. Comprehensive Psy-

personality disorder. Comprehensive Psychi- chiatry, 53, 765–774.

atry, 44, 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/ Shearer, S. L., Peters, C. P., Quaytman, M. S., &

S0010-440X(03)00091-9 Ogden, R. L. (1990). Frequency and cor-

Infurna, M. R., Brunner, R., Holz, B., Parzer, P., relates of childhood sexual and physical

Giannone, F., Reichl, C., . . . Kaess, M. abuse histories in adult female borderline

(2016). The specific role of childhood abuse, patients. American Journal of Psychiatry,

parental bonding, and family functioning in 147, 214–216.

female adolescents with borderline person- Skodol, A. E., Bender, D. S., Pagano, M. E., Shea,

ality disorder. Journal of Personality Disor- M. T., Yen, S., Sanislow, C. A., . . . Gunderson,

ders, 30, 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1521/ J. G. (2007). Positive childhood experiences:

pedi_2015_29_186 Resilience and recovery from personality dis-

James, A., Berelowitz, M., & Vereker, M. (1996). order in early adulthood. Journal of Clinical

Borderline personality disorder: A study in Psychiatry, 68, 1102–1108.

adolescence. European Child & Adolescent Stepp, S. D., Keenan, K., Hipwell, A. E., & Krueger,

Psychiatry, 5, 11–17. R. F. (2014). The impact of childhood temper-

Links, P. S., Steiner, M., Offord, D. R., & Eppel, A. ament on the development of borderline per-

(1988). Characteristics of borderline person- sonality disorder symptoms over the course of

ality disorder: A Canadian study. Canadian adolescence. Borderline Personality Disorder

Journal of Psychiatry, 33, 336–340. and Emotional Dysregulation, 1(1), 18.

Matzner, F., Silva, R., Silvan, M., Chowdhury, M., Stepp, S., Whalen, D., Scott, L., Zalewski, M.,

& Nastari, L. (1997). Preliminary test-retest Loeber, R., & Hipwell, A. (2014). Recip-

reliability of the KID-SCID. Paper presented rocal effects of parenting and borderline

at the annual meeting of the American Psy- personality disorder symptoms in adoles-

chiatric Association. cent girls. Development and Psychopathol-

Morey, L. C., Gunderson, J. G., Quigley, B. D., ogy, 26, 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1017/

Shea, M. T., Skodol, A. E., McGlashan, T. H., S0954579413001041

. . . Zanarini, M. C. (2002). The representa- Westen, D., Ludolph, P., Misle, B., Ruffins, S., &

tion of borderline, avoidant, obsessive-com- Block, J. (1990). Physical and sexual abuse in

pulsive, and schizotypal personality disorders adolescent girls with borderline personality

by the five-factor model. Journal of Personal- disorder. American Journal of Orthopsychia-

ity Disorders, 16(3), 215–234. try, 60, 55–66.

Ogata, S. N., Silk, K. R., Goodrich, S., Lohr, N. E., Zanarini, M. C., Gunderson, J. G., Frankenburg,

Westen, D., & Hill, E. M. (1990). Childhood F. R., & Chauncey, D. L. (1989). The Revised

G4884.indd 23 9/23/2020 12:32:46 PM

24 ZANARINI ET AL.

Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines: Dis- borderline symptoms reported by adolescent

criminating BPD from other Axis II disor- inpatients with BPD, psychiatrically healthy

ders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 3, adolescents and adult inpatients with BPD.

10–18. Personal Mental Health, 11(3), 150–156.

Zanarini, M. C., Gunderson, J. G., Marino, M. F., Zanarini, M. C., Williams, A. A., Lewis, R. E., Reich,

Schwartz, E. O., & Frankenburg, F. R. (1989). R. B., Vera, S. C., Marino, M. F., . . . Fran-

Childhood experiences of borderline patients. kenburg, F. R. (1997). Reported pathological

Comprehensive Psychiatry, 30(1), 18–25. childhood experiences associated with the

Zanarini, M. C., Temes, C. M., Magni, L. R., development of borderline personality dis-

Fitzmaurice, G. M., Aguirre, B. A., & order. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154,

Goodman, M. (2017). Prevalence rates of 1101–1106.

G4884.indd 24 9/23/2020 12:32:46 PM

You might also like

- Self-Reporting Booklet - Am I An ADHDerDocument73 pagesSelf-Reporting Booklet - Am I An ADHDerOmayra Sánchez González100% (2)

- Sports PhysicalDocument6 pagesSports Physicalapi-671085061No ratings yet

- Poultry Disease MCQs - Veterinary Online QuizzesDocument4 pagesPoultry Disease MCQs - Veterinary Online Quizzesbasit abdulNo ratings yet

- 2022 ART Revised Kenyan GuidelinesDocument39 pages2022 ART Revised Kenyan GuidelinesJOHN KAMAUNo ratings yet

- Reported Pathological ChildhoodDocument7 pagesReported Pathological ChildhoodMartha Lucía Triviño LuengasNo ratings yet

- Associations Between Four Types of Childhood Neglect and Personality Disorder Symptoms During Adolescence and Early Adulthood: Findings of A Community-Based Longitudinal StudyDocument17 pagesAssociations Between Four Types of Childhood Neglect and Personality Disorder Symptoms During Adolescence and Early Adulthood: Findings of A Community-Based Longitudinal StudyUmer FarooqNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting The Diagnosis and Prediction of PTSD PDFDocument8 pagesFactors Affecting The Diagnosis and Prediction of PTSD PDFAGRANo ratings yet

- (PERSONALIDADE) Childhood Maltreatment Increases Risk For Personality Disorders During Early Adulthood (JAMA 1999)Document7 pages(PERSONALIDADE) Childhood Maltreatment Increases Risk For Personality Disorders During Early Adulthood (JAMA 1999)dilsohNo ratings yet

- Construct Validity of TPAADocument11 pagesConstruct Validity of TPAAponchossNo ratings yet

- Lister, 2015Document7 pagesLister, 2015Bianca HlepcoNo ratings yet

- RESUMEN ANALÍTICO ESPECIALIZADO (RAE) PsicopatologíaDocument7 pagesRESUMEN ANALÍTICO ESPECIALIZADO (RAE) PsicopatologíaCamila GuevaraNo ratings yet

- BulliedDocument13 pagesBulliedBarry BurijonNo ratings yet

- Fruzzetti 2005 OptionalDocument24 pagesFruzzetti 2005 OptionalMacovei Anca0% (1)

- Dating Violence Perpetration and Victimization Among U.S. Adolescents: Prevalence, Patterns, and Associations With Health Complaints and Substance UseDocument8 pagesDating Violence Perpetration and Victimization Among U.S. Adolescents: Prevalence, Patterns, and Associations With Health Complaints and Substance UseAlba EneaNo ratings yet

- Lee, Z,2003 Validez APSDDocument16 pagesLee, Z,2003 Validez APSDSonia FernandezNo ratings yet

- Early Risk and Protective Factors and Young Adult Outcomes in A Longitudinal Sample ofDocument22 pagesEarly Risk and Protective Factors and Young Adult Outcomes in A Longitudinal Sample ofNhon NhonNo ratings yet

- Fonseca-Pedrero, Et Al., 2011Document15 pagesFonseca-Pedrero, Et Al., 2011Diana StrambeiNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Personality Disorders Associated With Violence and Criminal Behavior During Adolescence and Early AdulthoodDocument7 pagesAdolescent Personality Disorders Associated With Violence and Criminal Behavior During Adolescence and Early AdulthoodIoana Duminicel100% (1)

- Child Maltreatment and Mental Health Problems in Adulthood Birth Cohort StudyDocument6 pagesChild Maltreatment and Mental Health Problems in Adulthood Birth Cohort Studyfotosiphone 8No ratings yet

- Psychopathics Traits in Adolescent OffendersDocument25 pagesPsychopathics Traits in Adolescent OffendersТеодора ДелићNo ratings yet

- Violencia en La Pareja1 PDFDocument13 pagesViolencia en La Pareja1 PDFNata ParraNo ratings yet

- Childhood Adversity and TLPDocument15 pagesChildhood Adversity and TLPPaula Ardila100% (1)

- Gri Zenko 1994Document11 pagesGri Zenko 1994Alex BoncuNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography On Childhood Risk Factors To Criminal BehaviorDocument8 pagesAnnotated Bibliography On Childhood Risk Factors To Criminal Behaviorapi-667528548No ratings yet

- Edwards Et Al, 2021Document18 pagesEdwards Et Al, 2021fq8h6d87t4No ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument35 pagesNIH Public Access: Author Manuscriptalfath akbarNo ratings yet

- (2013) - ExnerDocument10 pages(2013) - Exnerbeatriz.l.oliveira.2300No ratings yet

- Personality Disorders in AdolescenceDocument2 pagesPersonality Disorders in AdolescenceMale BajoNo ratings yet

- Associations Between Childhood Trauma, Bullying and Psychotic Symptoms Among A School-Based Adolescent SampleDocument6 pagesAssociations Between Childhood Trauma, Bullying and Psychotic Symptoms Among A School-Based Adolescent SampleChRist LumingkewasNo ratings yet

- The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in ADocument15 pagesThe Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in ATuấn KhangNo ratings yet

- T K9 Ogxr LGUDocument7 pagesT K9 Ogxr LGUs.ullah janNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood Predictors of Boys' Antisocial and Violent Behavior in Early AdulthoodDocument15 pagesEarly Childhood Predictors of Boys' Antisocial and Violent Behavior in Early AdulthoodVictoria ZorzopulosNo ratings yet

- Childhood Adversity and Associated Psychosocial Function inDocument19 pagesChildhood Adversity and Associated Psychosocial Function inAraceli del PilarNo ratings yet

- Child and Adolescent Maltreatment Patterns and Risk of Eating Disorder Behaviors Developing in Young AdulthoodDocument9 pagesChild and Adolescent Maltreatment Patterns and Risk of Eating Disorder Behaviors Developing in Young AdulthoodVivian BandeiraNo ratings yet

- Child Abuse & Neglect: SciencedirectDocument19 pagesChild Abuse & Neglect: Sciencedirectana raquelNo ratings yet

- Childhood Adversity and Personality Disorders Results From A Nationallyrepresentative Population-Based Study - Afifi 2016 PDFDocument9 pagesChildhood Adversity and Personality Disorders Results From A Nationallyrepresentative Population-Based Study - Afifi 2016 PDFRodrigo Romo MuñozNo ratings yet

- A Risk Calculator For Bipolar Spectrum DisorderDocument2 pagesA Risk Calculator For Bipolar Spectrum DisorderDavidNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Reciprocal-Effects of Parenting and Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms in Adolescent GirlsDocument35 pagesNIH Public Access: Reciprocal-Effects of Parenting and Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms in Adolescent Girlsalfath akbarNo ratings yet

- Child Personality Facets and Overreactive Parenting As PredictorsDocument15 pagesChild Personality Facets and Overreactive Parenting As Predictorsmary grace bialenNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0165178123000124 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S0165178123000124 MainDwi HandayaniNo ratings yet

- 1 Sem 2 ModerationDocument18 pages1 Sem 2 ModerationalbertoNo ratings yet

- Vonderlin, 2018Document10 pagesVonderlin, 2018Zeynep ÖzmeydanNo ratings yet

- Jamapediatrics Moreno 2023 Ed 220035 1673637425.56866Document2 pagesJamapediatrics Moreno 2023 Ed 220035 1673637425.56866Lili CarrizalesNo ratings yet

- Callous-Unemotional Traits and Their Implication For Understanding and Treating Aggressive and Violent YouthsDocument20 pagesCallous-Unemotional Traits and Their Implication For Understanding and Treating Aggressive and Violent YouthsMaría Teresa Carrasco OjedaNo ratings yet

- Running Head: MENTAL DISORDERS 1Document12 pagesRunning Head: MENTAL DISORDERS 1api-532509198No ratings yet

- The Behavior of Anxious Parents Examining Mechanisms of Transmission of Anxiety From Parent To ChildDocument12 pagesThe Behavior of Anxious Parents Examining Mechanisms of Transmission of Anxiety From Parent To Child方科惠No ratings yet

- Talking About Sexuality With YouthDocument9 pagesTalking About Sexuality With YouthMariana AzevedoNo ratings yet

- Peer Selection and Socialization Effects On Adolescent Intercourse Without A Condom and Attitudes About The Costs of SexDocument14 pagesPeer Selection and Socialization Effects On Adolescent Intercourse Without A Condom and Attitudes About The Costs of SexTwradioNo ratings yet

- Kugler 2018Document8 pagesKugler 2018Andra IvanNo ratings yet

- Reactive Attachment Disorder Following Early Maltreatment: Systematic Evidence Beyond The InstitutionDocument11 pagesReactive Attachment Disorder Following Early Maltreatment: Systematic Evidence Beyond The Institution874328No ratings yet

- Prevalence of Mental Disorders - Children and AdolescentsDocument17 pagesPrevalence of Mental Disorders - Children and Adolescentsisabellabatista.psiNo ratings yet

- Children of Mothers With BPDDocument16 pagesChildren of Mothers With BPDapi-252946468100% (1)

- Nihms-July 22 - Early Timing and Determinants of The Sexual Orientation DisparityDocument22 pagesNihms-July 22 - Early Timing and Determinants of The Sexual Orientation DisparityArdaNo ratings yet

- Nihms 923786Document12 pagesNihms 923786FARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- 1-S2.0-S1053810016300629-Main Intimate Partner ViolenceDocument10 pages1-S2.0-S1053810016300629-Main Intimate Partner ViolenceVissente TapiaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Childhood Traumatization in The Development of Borderline Personality Disorder in HungaryDocument14 pagesThe Role of Childhood Traumatization in The Development of Borderline Personality Disorder in HungaryrahafNo ratings yet

- Predictive Factors For Juvenile Delinquency: The Role of Family Structure, Parental Monitoring and Delinquent PeersDocument9 pagesPredictive Factors For Juvenile Delinquency: The Role of Family Structure, Parental Monitoring and Delinquent PeersYogi setiawanNo ratings yet

- Rates of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in YouthDocument9 pagesRates of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury in YouthWilson Javier Dominguez PerezNo ratings yet

- Gender Identity Disorder in Children and AdolescentsDocument27 pagesGender Identity Disorder in Children and AdolescentsGender Spectrum100% (3)

- From Emotional Abuse in Childhood To Psy PDFDocument24 pagesFrom Emotional Abuse in Childhood To Psy PDFNicoleta VasiliuNo ratings yet

- When Nowhere Is Safe: Interpersonal Trauma and Attachment Adversity As Antecedents of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Developmental Trauma DisorderDocument12 pagesWhen Nowhere Is Safe: Interpersonal Trauma and Attachment Adversity As Antecedents of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Developmental Trauma DisorderNerea F GNo ratings yet

- Foster Care IrrDocument7 pagesFoster Care Irrapi-530384945100% (1)

- Collishaw Et Al. (2007)Document49 pagesCollishaw Et Al. (2007)voooNo ratings yet

- Washignton ReportDocument8 pagesWashignton ReportSaim AliNo ratings yet

- Nurs 401 Case Study 5Document4 pagesNurs 401 Case Study 5Aliza SaddalNo ratings yet

- Block 4 Renal Lecture 1 MCQDocument5 pagesBlock 4 Renal Lecture 1 MCQMahmoud ElshrkawyNo ratings yet

- HEPAB Vax DSDocument3 pagesHEPAB Vax DSSheena Marie M. TarleNo ratings yet

- SepticemiaDocument1 pageSepticemiaomarwalidalhussaini2005No ratings yet

- Folliculitis and TrichomycosisDocument4 pagesFolliculitis and TrichomycosisYolisNo ratings yet

- C6.1clasificare LimfoameDocument10 pagesC6.1clasificare LimfoameRădulescu AndreeaNo ratings yet

- Typhoid PresentationDocument40 pagesTyphoid PresentationmakioedesemiNo ratings yet

- Atualização NeuromuscularDocument5 pagesAtualização NeuromuscularRodrigo VanzelliNo ratings yet

- Amir + Lev-Wiesel - 2007 - Dissociation As Depicted in Traumatic DrawingsDocument10 pagesAmir + Lev-Wiesel - 2007 - Dissociation As Depicted in Traumatic DrawingsAlejandra IsabelNo ratings yet

- DS SalbutamolDocument1 pageDS SalbutamolLarr SumalpongNo ratings yet

- ATPL08HumanPerformanceNPA29 2Document100 pagesATPL08HumanPerformanceNPA29 2André Luiz BragaNo ratings yet

- GDMTDocument2 pagesGDMTapi-690342013No ratings yet

- NN 2Document10 pagesNN 2Thành ĐinhNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmology Set 1Document6 pagesOphthalmology Set 1ajay khadeNo ratings yet

- Liver Cirrhosis 2020Document27 pagesLiver Cirrhosis 2020Gabriela SalasNo ratings yet

- EAU Guidelines 2023 PDFDocument2,012 pagesEAU Guidelines 2023 PDFEncep SetiawanNo ratings yet

- A Case Study On MalariaDocument10 pagesA Case Study On MalariaAnant KumarNo ratings yet

- Practical Aspects of IVUS-Guided Percutaneous Coronary InterventionDocument7 pagesPractical Aspects of IVUS-Guided Percutaneous Coronary InterventionRajesh JayakumarNo ratings yet

- 311 Topotecan Monotherapy 5 DayDocument4 pages311 Topotecan Monotherapy 5 DayRuxandra BănicăNo ratings yet

- Progress Report National Cancer Registry in IndonesiaDocument47 pagesProgress Report National Cancer Registry in IndonesiaIndonesian Journal of Cancer100% (1)

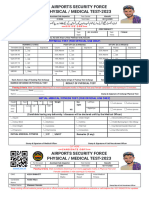

- Airport Security ForcesDocument2 pagesAirport Security ForcesJamsher BalochNo ratings yet

- LeptospirosisDocument26 pagesLeptospirosisDinesh KumarNo ratings yet

- DebateDocument12 pagesDebate•Kai yiii•No ratings yet

- 1 - VSD (Part 2) - Hatem HosnyDocument28 pages1 - VSD (Part 2) - Hatem Hosnyrami ibrahiemNo ratings yet

- Glimmers of Hope For Targeting Oncogenic KRAS-G12D: Cancer Gene TherapyDocument3 pagesGlimmers of Hope For Targeting Oncogenic KRAS-G12D: Cancer Gene Therapychato law officeNo ratings yet