Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Guide To Risk Assessment in Ship Operations

A Guide To Risk Assessment in Ship Operations

Uploaded by

Dmytro OparivskyCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Baybutt-2018-Process Safety Progress PDFDocument7 pagesBaybutt-2018-Process Safety Progress PDFfzegarra1088100% (1)

- Marketing Test Bank Chap 11Document51 pagesMarketing Test Bank Chap 11Ta Thi Minh ChauNo ratings yet

- Rio Tinto - Procedure For Compliance Risk AssessmentDocument24 pagesRio Tinto - Procedure For Compliance Risk AssessmentHer Huw100% (1)

- Risk Assessment Procedure: Daqing Petroleum Iraq BranchDocument10 pagesRisk Assessment Procedure: Daqing Petroleum Iraq Branchkhurram100% (1)

- Koh Kiar Sing Wpa (Paper 4)Document32 pagesKoh Kiar Sing Wpa (Paper 4)Muhamad HarizNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 Risk Management PlanDocument23 pagesChapter 10 Risk Management PlanPrabath Nilan Gunasekara100% (1)

- 4risk ManagementDocument8 pages4risk ManagementSomar SafatlyNo ratings yet

- SAF-6-1 Identification & Mitigation of Critical HazardsDocument7 pagesSAF-6-1 Identification & Mitigation of Critical HazardsCyprian AendeNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment Proc - 1Document35 pagesRisk Assessment Proc - 1bilo1984No ratings yet

- Risk Management ModelDocument11 pagesRisk Management ModelmariuscernicaNo ratings yet

- Prediction and Assessment of LHD Machine Breakdowns Using Failure Mode Effect Analysis (Fmea)Document8 pagesPrediction and Assessment of LHD Machine Breakdowns Using Failure Mode Effect Analysis (Fmea)julio beniscelliNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment & Control Module 3Document38 pagesRisk Assessment & Control Module 3Marvin ReggieNo ratings yet

- METHODOLOGYDocument3 pagesMETHODOLOGYSyakirin Spears100% (1)

- Guide To Risk Assessment in Ship OperationsDocument7 pagesGuide To Risk Assessment in Ship OperationsearthanskyfriendsNo ratings yet

- 02.00MSHEM - Specific Awareness 02.00Document209 pages02.00MSHEM - Specific Awareness 02.00ShadifNo ratings yet

- Hazard Assessment and Risk ControlDocument15 pagesHazard Assessment and Risk ControlAnisNo ratings yet

- wcms_184162Document34 pageswcms_184162Engr. Saruar J. ShourovNo ratings yet

- Risk AssessmentDocument5 pagesRisk AssessmentJalilalawame AliNo ratings yet

- MINE5551 Risk AssessmentDocument54 pagesMINE5551 Risk AssessmentJoshNo ratings yet

- Procedure - Risk Management - 2021Document7 pagesProcedure - Risk Management - 2021Charly MNNo ratings yet

- Generic Risk Assessment FormDocument2 pagesGeneric Risk Assessment Formblackiceman100% (2)

- Lecture Notes:: Risk Assessment & Risk ManagementDocument25 pagesLecture Notes:: Risk Assessment & Risk Managementeladio30No ratings yet

- Identifying and Categorizing Risks: WHO / Fredrik NaumannDocument26 pagesIdentifying and Categorizing Risks: WHO / Fredrik NaumannDiegoNo ratings yet

- 2-HEMP-Hazards and Effects ManagementDocument17 pages2-HEMP-Hazards and Effects ManagementShahid IqbalNo ratings yet

- Trex 05475Document144 pagesTrex 05475OSDocs2012No ratings yet

- Quality Risk ManagementDocument5 pagesQuality Risk ManagementA VegaNo ratings yet

- INDEX 1 Risk ManagementDocument13 pagesINDEX 1 Risk ManagementAhmed Adel El-NweryNo ratings yet

- RA - (LPG System)Document26 pagesRA - (LPG System)Md ShahinNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment & Risk Management: Topic FiveDocument25 pagesRisk Assessment & Risk Management: Topic FiveParth RavalNo ratings yet

- Guidance On Carrying Out Hazid and Risk Assessment ActivitiesDocument6 pagesGuidance On Carrying Out Hazid and Risk Assessment Activitiesmac1677No ratings yet

- Risk Assessment and Management ISM PapersDocument14 pagesRisk Assessment and Management ISM Papersfredy2212No ratings yet

- AV-SWP-08 Risk Assessment Iss 1Document4 pagesAV-SWP-08 Risk Assessment Iss 1Kevin DeLimaNo ratings yet

- 1.1 Risk AssessmentsDocument3 pages1.1 Risk AssessmentsHATEMNo ratings yet

- VIU Risk Management FrameworkDocument9 pagesVIU Risk Management FrameworkkharistiaNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment For Maintenance - Ricky Smith - LceDocument4 pagesRisk Assessment For Maintenance - Ricky Smith - LceFernando AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Training Module 2 FINALDocument75 pagesTraining Module 2 FINALmolla fentayeNo ratings yet

- Risk Management SopDocument8 pagesRisk Management SopLi QiNo ratings yet

- Risk Management SopDocument8 pagesRisk Management SopLi QiNo ratings yet

- Presentation For Partial Fulfillment of The Diploma in Occupational Safety and HealthDocument16 pagesPresentation For Partial Fulfillment of The Diploma in Occupational Safety and HealthmarinaNo ratings yet

- Step-By-Step Explanation of ISO 27001/ISO 27005 Risk ManagementDocument15 pagesStep-By-Step Explanation of ISO 27001/ISO 27005 Risk ManagementLyubomir Gekov100% (1)

- Assessment Task 2Document12 pagesAssessment Task 2Bui AnNo ratings yet

- Risk Management Worksheets Risk Assessment WorksheetDocument4 pagesRisk Management Worksheets Risk Assessment Worksheetkapil ajmaniNo ratings yet

- Step by Step Explanation of ISO 27001 Risk Management enDocument15 pagesStep by Step Explanation of ISO 27001 Risk Management enNilesh RoyNo ratings yet

- Step by Step Explanation of ISO 27001 Risk Management enDocument15 pagesStep by Step Explanation of ISO 27001 Risk Management enAllan BellucciNo ratings yet

- Topic 4 Relevant Notes Part 2 - FireExtinguisherDocument18 pagesTopic 4 Relevant Notes Part 2 - FireExtinguisherNazrina RinaNo ratings yet

- Safe Practice and EnvironmentDocument8 pagesSafe Practice and EnvironmentPaolocute11 BalongNo ratings yet

- Risk Management Chapter 2Document25 pagesRisk Management Chapter 2Nayle aldrinn LuceroNo ratings yet

- Scandizzo 2005 Economic NotesDocument26 pagesScandizzo 2005 Economic NotesFaisal Rehman100% (1)

- Introduction To Risk ManagementDocument44 pagesIntroduction To Risk Managementpikamau100% (1)

- Step-By-Step Explanation of ISO 27001/ISO 27005 Risk ManagementDocument15 pagesStep-By-Step Explanation of ISO 27001/ISO 27005 Risk ManagementMarisela RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Bowtie Pro MethodologyDocument13 pagesBowtie Pro MethodologyBrenda Velez AlemanNo ratings yet

- Managing Major Accident Hazards Through Sce Management ProcessDocument4 pagesManaging Major Accident Hazards Through Sce Management ProcessLi QiNo ratings yet

- M0010 Risk Assessment ManualDocument51 pagesM0010 Risk Assessment ManualnivasmarineNo ratings yet

- HSE Environmental Hazard Control Procedure 1674601317Document6 pagesHSE Environmental Hazard Control Procedure 1674601317hoangmtbNo ratings yet

- Nepal EHA Final Report 2016-003Document15 pagesNepal EHA Final Report 2016-003mardiradNo ratings yet

- Hazard IdentificationDocument6 pagesHazard IdentificationM. MagnoNo ratings yet

- Procedure For Hazard Identification, Risk Assessment, and Determining ControlsDocument8 pagesProcedure For Hazard Identification, Risk Assessment, and Determining Controlsdhir.ankur100% (1)

- Risk CH 2 SUNLearnDocument48 pagesRisk CH 2 SUNLearnyondelamakubaloNo ratings yet

- 5 Critical Steps To Successful ISO 27001 Risk Assessments: October 2018Document10 pages5 Critical Steps To Successful ISO 27001 Risk Assessments: October 2018Dinesh O BarejaNo ratings yet

- Risk Management and Information Systems ControlFrom EverandRisk Management and Information Systems ControlRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Foundations of Quality Risk Management: A Practical Approach to Effective Risk-Based ThinkingFrom EverandFoundations of Quality Risk Management: A Practical Approach to Effective Risk-Based ThinkingNo ratings yet

- MRP SampleDocument115 pagesMRP SampleAbu AlAnda Gate for metal industries and Equipment.No ratings yet

- Partnership Accounting by Principles of Accounting, Volume 1 - Financial AccountingDocument30 pagesPartnership Accounting by Principles of Accounting, Volume 1 - Financial AccountingLeilyn Mae D. AbellarNo ratings yet

- "Shop Safe" Act (2023)Document14 pages"Shop Safe" Act (2023)Sarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- NMIMS Sem 2 Assignment Solution June 2020Document9 pagesNMIMS Sem 2 Assignment Solution June 2020Palaniappan NNo ratings yet

- JKUAT 1.2 Lecture 5 Levels and Skills of ManagementDocument14 pagesJKUAT 1.2 Lecture 5 Levels and Skills of ManagementPrashansa JaahnwiNo ratings yet

- Entrep ReviewerDocument15 pagesEntrep ReviewerAmber BlodduweddNo ratings yet

- Job Person MatchDocument100 pagesJob Person MatchDitha MardianiNo ratings yet

- Strategic Facility ManagementDocument14 pagesStrategic Facility ManagementdaisyNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management Module 4Document21 pagesStrategic Management Module 4Rafols AnnabelleNo ratings yet

- The Role of Strategic Planning in Implementing A Total Quality Management Framework An Empirical ViewDocument14 pagesThe Role of Strategic Planning in Implementing A Total Quality Management Framework An Empirical Viewফারুক সাদিকNo ratings yet

- A Study of Behavioral Finance Biases and Its Impact On Investment Decisions of Individual InvestorsDocument64 pagesA Study of Behavioral Finance Biases and Its Impact On Investment Decisions of Individual InvestorsSHUKLA YOGESHNo ratings yet

- Audit Evidence SequenceDocument32 pagesAudit Evidence SequenceParbati AcharyaNo ratings yet

- On Line Class With 11 Abm Las Quarter 2 Week 3Document50 pagesOn Line Class With 11 Abm Las Quarter 2 Week 3Mirian De OcampoNo ratings yet

- 02-RA For Panel InstallationDocument5 pages02-RA For Panel Installation287100% (1)

- JO - 10 - Egis Group Safety EngineerDocument3 pagesJO - 10 - Egis Group Safety EngineerudbarryNo ratings yet

- Tender and ContractsDocument15 pagesTender and ContractsSiddhrajsinh ZalaNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management Accounting ThesisDocument4 pagesStrategic Management Accounting Thesisfjda52j0100% (2)

- Template Journal TB Interia 2023Document233 pagesTemplate Journal TB Interia 2023Rifky FebriantoNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Management 5Th Edition Chopra Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument24 pagesSupply Chain Management 5Th Edition Chopra Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFedward.kibler915100% (11)

- It Realeted GoalsDocument9 pagesIt Realeted GoalsMario ValladaresNo ratings yet

- IPQCDocument2 pagesIPQCStephen Lim Kean JinNo ratings yet

- NEA Account Officer Level 7 SyllabusDocument5 pagesNEA Account Officer Level 7 Syllabusbadaladhikari12345No ratings yet

- Maintenance Performance Measurement (MPM) : Issues and ChallengesDocument14 pagesMaintenance Performance Measurement (MPM) : Issues and ChallengesMitt JohnNo ratings yet

- District Wise Target Change RSODocument5 pagesDistrict Wise Target Change RSODevesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Supplier Quality Manual: Sundram Fasteners LimitedDocument21 pagesSupplier Quality Manual: Sundram Fasteners LimitedR.BALASUBRAMANINo ratings yet

- Auditing Info System - Case StudyDocument8 pagesAuditing Info System - Case StudyLloyd OgabangNo ratings yet

- A Study On Inventory Management With Reference To Delta Paper MillsDocument94 pagesA Study On Inventory Management With Reference To Delta Paper MillsVajra Tejo67% (3)

- Project Plan For Implementation of The Quality Management System in LaboratoryDocument6 pagesProject Plan For Implementation of The Quality Management System in LaboratoryMansi Thaker100% (1)

- Investments An Introduction 11Th Edition Mayo Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument38 pagesInvestments An Introduction 11Th Edition Mayo Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFninhletitiaqt3100% (12)

A Guide To Risk Assessment in Ship Operations

A Guide To Risk Assessment in Ship Operations

Uploaded by

Dmytro OparivskyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Guide To Risk Assessment in Ship Operations

A Guide To Risk Assessment in Ship Operations

Uploaded by

Dmytro OparivskyCopyright:

Available Formats

No.

127

No.

No. A Guide to Risk Assessment in Ship Operations

127

127 INTRODUCTION

(June 2012)

(cont)

(Rev.1 Although it is not often referred to as such, the development and implementation of a

Nov 2021) documented safety management system is an exercise in risk management. The drafting or

amendment of written procedures involves looking at the company’s activities and operations,

identifying what could go wrong, and deciding what should be done to try to prevent it. The

documented procedures are the means by which the controls are applied.

There is no universally accepted definition of risk, but the one commonly applied and regarded

as authoritative in most industrial contexts is:

“Effect of uncertainty on objectives”

(ISO 31000:2018 definition 2.1 and ISO Guide 73:2009, definition 1.1)

IMO defines risk as:

“The combination of the frequency and the severity of the consequence.”

(MSC-MEPC.2/Circ.12/Rev.2)

In other words, risk has two components: likelihood of occurrence and severity of the

consequences.

A hazard is a substance, situation or practice that has the potential to cause harm. Briefly,

what we are concerned with, therefore, is:

- the identification of hazards

- the assessment of the risks associated with those hazards

- the application of controls to reduce the risks that are deemed intolerable

- the monitoring of the effectiveness of the controls

The controls may be applied either to reduce the likelihood of occurrence of an adverse event

and/or to reduce the severity of the consequences. The risks we are concerned with are those

that are reasonably foreseeable, and relate to:

- the health and safety of all those who are directly or indirectly involved in the activity, or

who may be otherwise affected

- the property of the company and others

- the environment

Page 1 of 6 IACS Rec. 2012/Rev.1 2021

No. 127

1. WHAT THE CODE SAYS ABOUT RISK ASSESSMENT

No.

Paragraph 1.2.2.2 of the ISM Code states: "Safety management objectives of the Company

127 should... assess all identified risks to its ships, personnel and the environment and establish

(cont) appropriate safeguards". Although there is no further, explicit reference to this general

requirement in the remainder of the Code, risk assessment of one form or another is essential

to compliance with most of its clauses.

It is important to recognize that the company is responsible for identifying the risks associated

with its particular ships, operations and trade. It is not sufficient to rely on compliance with

generic statutory and class requirements, and with general industry guidance. These should

be seen as a starting point for ensuring the safe operation of the ship.

The ISM Code does not specify any particular approach to the management of risk, and it is

for the company to choose methods appropriate to its organizational structure, its ships and its

trades. The methods may be more or less formal, but they must be systematic if assessment

and response are to be complete and effective, and the entire exercise should be documented

so as to provide evidence of the decision-making process.

2. THE RISK ASSESSMENT PROCESS

Risk assessment may be defined as:

“Overall process of risk identification, risk analysis and risk evaluation”

(ISO 31000:2018 definition 2.16 and ISO Guide 73:2009, definition 3.4.1)

The risk assessment process may be summarized by the flowchart below.

Page 2 of 6 IACS Rec. 2012/Rev.1 2021

No. 127

The identification of hazards is the first and most important step in risk assessment process

No. since all that follows depends on it. It must be complete and accurate, and should be based,

as far as possible, on observation of the activity. But hazard identification is not as easy as it

127 may first appear.

(cont)

Completeness and accuracy can be achieved only if the process is systematic. Those charged

with the task must have sufficient training and guidance to ensure that it is conducted in a

thorough and consistent manner. The terms used should be clearly defined and the process

must be fully described; for example, hazards must not be confused with incidents, and

incidents must not be confused with consequences.

There are many methods and tools used for risk assessment available and the Company is

free to use the most suitable one. Some of these most used methods of risk assessment

include:

- Checklists

- Preliminary hazard analysis

- Job safety analysis

- Quantitative risk analysis

- Qualitative risk analysis (Preliminary Hazard Analysis)

- SWIFT

- What if analysis

- 5 Whys analysis

- Fault tree analysis (FTA)

- Event tree analysis (ETA)

- Bow tie analysis (BTA)

- Failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA)

- Hazard and operational analysis (HAZOP)

Guidance on selection and application of risk assessment techniques is available, for example

in the international standard IEC 31010:2019 - Risk management – Risk assessment

techniques.

In the example of Qualitative Risk Analysis (Preliminary Hazard Analysis) method the risks

associated with each hazard are evaluated in terms of the likelihood of harm and the potential

consequences. This, in turn, enables the organization to establish priorities and to decide

where its scarce resources may be used to greatest effect.

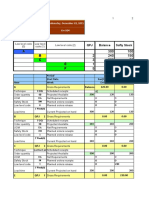

The combination of likelihood and consequence is normally illustrated as follows:

RISK ESTIMATOR

5 x 5 RISK MATRIX

Highly 5 10 15 20 25

Probable Moderate Major Major Severe Severe

4 8 12 16 20

Probable

Moderate Moderate Major Major Severe

LIKELIHOOD

3 6 9 12 15

Possible

Minor Moderate Moderate Major Major

2 4 6 8 10

Unlikely

Minor Moderate Moderate Moderate Major

1 2 3 4 5

Rare

Minor Minor Minor Moderate Moderate

Very Low Low Medium High Very High

CONSEQUENCES

Page 3 of 6 IACS Rec. 2012/Rev.1 2021

No. 127

The table below indicates the recommended response in each case.

No.

No additional controls are required.

127 Minor

Monitoring is required to ensure control is maintained.

(cont) Efforts are required to reduce risk.

Moderate

Controls are to be implemented within a specified time.

New work not to start until risk reduced.

Major If work in progress, urgent action to be taken. Considerable resources

may be required.

Work shall not be started or continued until the risk has been

Severe

reduced. If reduction is not possible, the activity shall be prohibited.

The tables above are for illustrative purposes and are not mandatory. The risk matrix may be

expanded to include more rows and columns, depending on how finely the company wishes to

distinguish the categories. The terms used for likelihood and consequence may be changed to

assist understanding. For example, likelihood may be expressed in terms of “once per trip”,

“once per ship year” or “once per fleet year”, and consequence may be made more specific by

the use of “first aid injury”, “serious injury” or “death”, not forgetting the consequences for

property and the environment.

When deciding on priorities for the application of controls, the frequency of the activity should

also be taken into account; for example, it may be more urgent to address a “moderate” level

of risk in a process that occurs every day than to impose controls over an activity that involves

“substantial” risk, but will not be carried out in the near future.

Furthermore, the terms applied to the levels of risk in the table above should not be interpreted

too rigidly. Risk should be reduced to a level that is as low as is reasonably practicable

(ALARP). If a “tolerable” level of risk can be reduced still further for a reasonable cost and with

little effort, then it should be. Standards of tolerability tend to be far stricter after an accident

than before. The ALARP concept is often illustrated thus

RISK

Unacceptable The risk is justifiable only in

region. exceptional circumstances.

Tolerable region. Tolerable only when risk

(The risk is acceptable reduction is not practicable or

only if there is a benefit). is disproportionate to the

benefits achieved (when the

cost of the reduction exceeds

the benefits).

Generally acceptable

region.

Insignificant Risk

THE “ALARP” TRIANGLE

Page 4 of 6 IACS Rec. 2012/Rev.1 2021

No. 127

The people chosen to undertake risk assessments should be those most familiar with the area,

No. and who have most experience of the task to be assessed. The process must be systematic,

and in order to make it so, it may help to categorize areas and activities as in the following

127 example.

(cont)

Assessment Unit : Deck

Activity : Tank cleaning

Hazard : Toxic atmosphere or lack of oxygen

Risk (before controls) : Intolerable (likely and extremely harmful)

Recommended Controls : Atmospheric testing, ventilation, use or availability of

breathing apparatus

3. ENSURING CONTINUITY AND FLEXIBILITY

All too often, companies carry out risk assessment exercises as separate, isolated activities.

The process is regarded as complete once the forms are filled in and filed away. But if new or

enhanced controls have been identified, they must be implemented, usually by inclusion in the

company’s documented procedures.

If it is to make a real, practical contribution to improving safety and preventing pollution, the

management of risks must be continual and flexible. A risk assessment is nothing more than a

“snapshot”. The organization, the technology, working practices, the regulatory environment

and other factors are constantly changing, and subsequently arising hazards may not be

included. Assessments must be reviewed regularly and in the light of experience; for example,

an increase in the number of accidents or hazardous occurrences may indicate that previously

implemented controls are no longer effective. Additional risk assessments will be needed for

infrequent activities or those being undertaken for the first time.

The formal risk assessment exercise is only one of many contributions to risk management.

Much more important are flexibility and responsiveness to a dynamic environment and its

dangers. The organization must ensure that it is sensitive to the signals provided by internal

audits, routine reporting, company and masters’ reviews, accident reports, etc., and that it

responds promptly and effectively.

4. PEOPLE

It is important to remember the subjective nature of risk perception; for example, one person

swinging 30m above the deck in a bosun’s chair may have a very different view of the risks

involved from that of another person in the same situation. This divergence in responses to

risk arises from differences in experience, training and temperament, and it can be

considerable. Who decides what is tolerable and what is acceptable? Because the judgements

of the people engaged in an activity may not coincide with those of the assessors, it is

essential that operational staff be involved in the assessment process. They have knowledge

of the activities and experience in their conduct, and they have to live with the consequences

of the decisions that are taken.

Furthermore, different levels of experience and training mean that the hazards and risks

associated with an activity can vary greatly with the people who carry it out, and conditions

may be very different from those prevailing at the time of the assessment.

Page 5 of 6 IACS Rec. 2012/Rev.1 2021

No. 127

Risk is not a constant, measurable, concrete entity. Quantitative assessments of risk must be

No. understood as estimates that are made at particular moments and are subject to considerable

degrees of uncertainty. They are not precise measurements, and the rarer (and usually more

127 catastrophic) the event, the less reliable the historical data and the estimates based on them

(cont) will be.

The best safeguard against accidents is a genuine safety culture - awareness and

constant vigilance on the part of all those involved, and the establishment of safety as a

permanent and natural feature of organizational decision-making.

End of

Document

Page 6 of 6 IACS Rec. 2012/Rev.1 2021

You might also like

- Baybutt-2018-Process Safety Progress PDFDocument7 pagesBaybutt-2018-Process Safety Progress PDFfzegarra1088100% (1)

- Marketing Test Bank Chap 11Document51 pagesMarketing Test Bank Chap 11Ta Thi Minh ChauNo ratings yet

- Rio Tinto - Procedure For Compliance Risk AssessmentDocument24 pagesRio Tinto - Procedure For Compliance Risk AssessmentHer Huw100% (1)

- Risk Assessment Procedure: Daqing Petroleum Iraq BranchDocument10 pagesRisk Assessment Procedure: Daqing Petroleum Iraq Branchkhurram100% (1)

- Koh Kiar Sing Wpa (Paper 4)Document32 pagesKoh Kiar Sing Wpa (Paper 4)Muhamad HarizNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 Risk Management PlanDocument23 pagesChapter 10 Risk Management PlanPrabath Nilan Gunasekara100% (1)

- 4risk ManagementDocument8 pages4risk ManagementSomar SafatlyNo ratings yet

- SAF-6-1 Identification & Mitigation of Critical HazardsDocument7 pagesSAF-6-1 Identification & Mitigation of Critical HazardsCyprian AendeNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment Proc - 1Document35 pagesRisk Assessment Proc - 1bilo1984No ratings yet

- Risk Management ModelDocument11 pagesRisk Management ModelmariuscernicaNo ratings yet

- Prediction and Assessment of LHD Machine Breakdowns Using Failure Mode Effect Analysis (Fmea)Document8 pagesPrediction and Assessment of LHD Machine Breakdowns Using Failure Mode Effect Analysis (Fmea)julio beniscelliNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment & Control Module 3Document38 pagesRisk Assessment & Control Module 3Marvin ReggieNo ratings yet

- METHODOLOGYDocument3 pagesMETHODOLOGYSyakirin Spears100% (1)

- Guide To Risk Assessment in Ship OperationsDocument7 pagesGuide To Risk Assessment in Ship OperationsearthanskyfriendsNo ratings yet

- 02.00MSHEM - Specific Awareness 02.00Document209 pages02.00MSHEM - Specific Awareness 02.00ShadifNo ratings yet

- Hazard Assessment and Risk ControlDocument15 pagesHazard Assessment and Risk ControlAnisNo ratings yet

- wcms_184162Document34 pageswcms_184162Engr. Saruar J. ShourovNo ratings yet

- Risk AssessmentDocument5 pagesRisk AssessmentJalilalawame AliNo ratings yet

- MINE5551 Risk AssessmentDocument54 pagesMINE5551 Risk AssessmentJoshNo ratings yet

- Procedure - Risk Management - 2021Document7 pagesProcedure - Risk Management - 2021Charly MNNo ratings yet

- Generic Risk Assessment FormDocument2 pagesGeneric Risk Assessment Formblackiceman100% (2)

- Lecture Notes:: Risk Assessment & Risk ManagementDocument25 pagesLecture Notes:: Risk Assessment & Risk Managementeladio30No ratings yet

- Identifying and Categorizing Risks: WHO / Fredrik NaumannDocument26 pagesIdentifying and Categorizing Risks: WHO / Fredrik NaumannDiegoNo ratings yet

- 2-HEMP-Hazards and Effects ManagementDocument17 pages2-HEMP-Hazards and Effects ManagementShahid IqbalNo ratings yet

- Trex 05475Document144 pagesTrex 05475OSDocs2012No ratings yet

- Quality Risk ManagementDocument5 pagesQuality Risk ManagementA VegaNo ratings yet

- INDEX 1 Risk ManagementDocument13 pagesINDEX 1 Risk ManagementAhmed Adel El-NweryNo ratings yet

- RA - (LPG System)Document26 pagesRA - (LPG System)Md ShahinNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment & Risk Management: Topic FiveDocument25 pagesRisk Assessment & Risk Management: Topic FiveParth RavalNo ratings yet

- Guidance On Carrying Out Hazid and Risk Assessment ActivitiesDocument6 pagesGuidance On Carrying Out Hazid and Risk Assessment Activitiesmac1677No ratings yet

- Risk Assessment and Management ISM PapersDocument14 pagesRisk Assessment and Management ISM Papersfredy2212No ratings yet

- AV-SWP-08 Risk Assessment Iss 1Document4 pagesAV-SWP-08 Risk Assessment Iss 1Kevin DeLimaNo ratings yet

- 1.1 Risk AssessmentsDocument3 pages1.1 Risk AssessmentsHATEMNo ratings yet

- VIU Risk Management FrameworkDocument9 pagesVIU Risk Management FrameworkkharistiaNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment For Maintenance - Ricky Smith - LceDocument4 pagesRisk Assessment For Maintenance - Ricky Smith - LceFernando AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Training Module 2 FINALDocument75 pagesTraining Module 2 FINALmolla fentayeNo ratings yet

- Risk Management SopDocument8 pagesRisk Management SopLi QiNo ratings yet

- Risk Management SopDocument8 pagesRisk Management SopLi QiNo ratings yet

- Presentation For Partial Fulfillment of The Diploma in Occupational Safety and HealthDocument16 pagesPresentation For Partial Fulfillment of The Diploma in Occupational Safety and HealthmarinaNo ratings yet

- Step-By-Step Explanation of ISO 27001/ISO 27005 Risk ManagementDocument15 pagesStep-By-Step Explanation of ISO 27001/ISO 27005 Risk ManagementLyubomir Gekov100% (1)

- Assessment Task 2Document12 pagesAssessment Task 2Bui AnNo ratings yet

- Risk Management Worksheets Risk Assessment WorksheetDocument4 pagesRisk Management Worksheets Risk Assessment Worksheetkapil ajmaniNo ratings yet

- Step by Step Explanation of ISO 27001 Risk Management enDocument15 pagesStep by Step Explanation of ISO 27001 Risk Management enNilesh RoyNo ratings yet

- Step by Step Explanation of ISO 27001 Risk Management enDocument15 pagesStep by Step Explanation of ISO 27001 Risk Management enAllan BellucciNo ratings yet

- Topic 4 Relevant Notes Part 2 - FireExtinguisherDocument18 pagesTopic 4 Relevant Notes Part 2 - FireExtinguisherNazrina RinaNo ratings yet

- Safe Practice and EnvironmentDocument8 pagesSafe Practice and EnvironmentPaolocute11 BalongNo ratings yet

- Risk Management Chapter 2Document25 pagesRisk Management Chapter 2Nayle aldrinn LuceroNo ratings yet

- Scandizzo 2005 Economic NotesDocument26 pagesScandizzo 2005 Economic NotesFaisal Rehman100% (1)

- Introduction To Risk ManagementDocument44 pagesIntroduction To Risk Managementpikamau100% (1)

- Step-By-Step Explanation of ISO 27001/ISO 27005 Risk ManagementDocument15 pagesStep-By-Step Explanation of ISO 27001/ISO 27005 Risk ManagementMarisela RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Bowtie Pro MethodologyDocument13 pagesBowtie Pro MethodologyBrenda Velez AlemanNo ratings yet

- Managing Major Accident Hazards Through Sce Management ProcessDocument4 pagesManaging Major Accident Hazards Through Sce Management ProcessLi QiNo ratings yet

- M0010 Risk Assessment ManualDocument51 pagesM0010 Risk Assessment ManualnivasmarineNo ratings yet

- HSE Environmental Hazard Control Procedure 1674601317Document6 pagesHSE Environmental Hazard Control Procedure 1674601317hoangmtbNo ratings yet

- Nepal EHA Final Report 2016-003Document15 pagesNepal EHA Final Report 2016-003mardiradNo ratings yet

- Hazard IdentificationDocument6 pagesHazard IdentificationM. MagnoNo ratings yet

- Procedure For Hazard Identification, Risk Assessment, and Determining ControlsDocument8 pagesProcedure For Hazard Identification, Risk Assessment, and Determining Controlsdhir.ankur100% (1)

- Risk CH 2 SUNLearnDocument48 pagesRisk CH 2 SUNLearnyondelamakubaloNo ratings yet

- 5 Critical Steps To Successful ISO 27001 Risk Assessments: October 2018Document10 pages5 Critical Steps To Successful ISO 27001 Risk Assessments: October 2018Dinesh O BarejaNo ratings yet

- Risk Management and Information Systems ControlFrom EverandRisk Management and Information Systems ControlRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Foundations of Quality Risk Management: A Practical Approach to Effective Risk-Based ThinkingFrom EverandFoundations of Quality Risk Management: A Practical Approach to Effective Risk-Based ThinkingNo ratings yet

- MRP SampleDocument115 pagesMRP SampleAbu AlAnda Gate for metal industries and Equipment.No ratings yet

- Partnership Accounting by Principles of Accounting, Volume 1 - Financial AccountingDocument30 pagesPartnership Accounting by Principles of Accounting, Volume 1 - Financial AccountingLeilyn Mae D. AbellarNo ratings yet

- "Shop Safe" Act (2023)Document14 pages"Shop Safe" Act (2023)Sarah BursteinNo ratings yet

- NMIMS Sem 2 Assignment Solution June 2020Document9 pagesNMIMS Sem 2 Assignment Solution June 2020Palaniappan NNo ratings yet

- JKUAT 1.2 Lecture 5 Levels and Skills of ManagementDocument14 pagesJKUAT 1.2 Lecture 5 Levels and Skills of ManagementPrashansa JaahnwiNo ratings yet

- Entrep ReviewerDocument15 pagesEntrep ReviewerAmber BlodduweddNo ratings yet

- Job Person MatchDocument100 pagesJob Person MatchDitha MardianiNo ratings yet

- Strategic Facility ManagementDocument14 pagesStrategic Facility ManagementdaisyNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management Module 4Document21 pagesStrategic Management Module 4Rafols AnnabelleNo ratings yet

- The Role of Strategic Planning in Implementing A Total Quality Management Framework An Empirical ViewDocument14 pagesThe Role of Strategic Planning in Implementing A Total Quality Management Framework An Empirical Viewফারুক সাদিকNo ratings yet

- A Study of Behavioral Finance Biases and Its Impact On Investment Decisions of Individual InvestorsDocument64 pagesA Study of Behavioral Finance Biases and Its Impact On Investment Decisions of Individual InvestorsSHUKLA YOGESHNo ratings yet

- Audit Evidence SequenceDocument32 pagesAudit Evidence SequenceParbati AcharyaNo ratings yet

- On Line Class With 11 Abm Las Quarter 2 Week 3Document50 pagesOn Line Class With 11 Abm Las Quarter 2 Week 3Mirian De OcampoNo ratings yet

- 02-RA For Panel InstallationDocument5 pages02-RA For Panel Installation287100% (1)

- JO - 10 - Egis Group Safety EngineerDocument3 pagesJO - 10 - Egis Group Safety EngineerudbarryNo ratings yet

- Tender and ContractsDocument15 pagesTender and ContractsSiddhrajsinh ZalaNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management Accounting ThesisDocument4 pagesStrategic Management Accounting Thesisfjda52j0100% (2)

- Template Journal TB Interia 2023Document233 pagesTemplate Journal TB Interia 2023Rifky FebriantoNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Management 5Th Edition Chopra Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument24 pagesSupply Chain Management 5Th Edition Chopra Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFedward.kibler915100% (11)

- It Realeted GoalsDocument9 pagesIt Realeted GoalsMario ValladaresNo ratings yet

- IPQCDocument2 pagesIPQCStephen Lim Kean JinNo ratings yet

- NEA Account Officer Level 7 SyllabusDocument5 pagesNEA Account Officer Level 7 Syllabusbadaladhikari12345No ratings yet

- Maintenance Performance Measurement (MPM) : Issues and ChallengesDocument14 pagesMaintenance Performance Measurement (MPM) : Issues and ChallengesMitt JohnNo ratings yet

- District Wise Target Change RSODocument5 pagesDistrict Wise Target Change RSODevesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Supplier Quality Manual: Sundram Fasteners LimitedDocument21 pagesSupplier Quality Manual: Sundram Fasteners LimitedR.BALASUBRAMANINo ratings yet

- Auditing Info System - Case StudyDocument8 pagesAuditing Info System - Case StudyLloyd OgabangNo ratings yet

- A Study On Inventory Management With Reference To Delta Paper MillsDocument94 pagesA Study On Inventory Management With Reference To Delta Paper MillsVajra Tejo67% (3)

- Project Plan For Implementation of The Quality Management System in LaboratoryDocument6 pagesProject Plan For Implementation of The Quality Management System in LaboratoryMansi Thaker100% (1)

- Investments An Introduction 11Th Edition Mayo Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument38 pagesInvestments An Introduction 11Th Edition Mayo Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFninhletitiaqt3100% (12)