Professional Documents

Culture Documents

TOK Extract Indigenous Societies

TOK Extract Indigenous Societies

Uploaded by

Ahmad OmarOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

TOK Extract Indigenous Societies

TOK Extract Indigenous Societies

Uploaded by

Ahmad OmarCopyright:

Available Formats

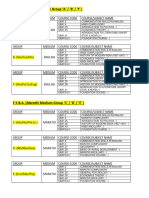

EExtract from Theory of Knowledge, Fourth edition by Carolin P.

Henly and John Sprague

(Hodder Education) ISBN:9781510474314

www.hoddereducation.co.uk/tok

5 Knowledge and Indigenous Societies

OBJECTIVES Learner profile

After reading this chapter, students will: Caring

understand the practical and ethical challenges of attempting to define the word Can we empathize

‘Indigenous’ with other cultures

understand common features of Indigenous knowledge systems and remain

recognize the impact of these features on the methods and tools used to develop objective?

knowledge

understand the role of myth and ritual in establishing relationships between individuals

and communities

recognize the threat to Indigenous knowledge systems and the importance of

education to protect these systems.

Introduction

In October 1882, a 22-year-old Navajo man arrived in southern Pennsylvania, transported there

from his native homelands in the southwest of the United States. He was joining the Carlisle

Indian Industrial School, established in 1879, and was given a new haircut, new clothes and a

new name: Tom Torlino, a poor approximation of his Native name: Hastiin To’Haali (Yurth). He

was forbidden from then on to speak his native language. Students like Tom would have learned

English, maths and world history, as well as how to march, and how to play American football,

baseball and musical instruments. Instead of living free with his people, he now took his exercise

in the school’s gymnasium, ‘where liberal provision is made for exercising the muscles and

fortifying the constitution against sickness’ (‘Description of the grounds’). He was there, in the

words of the school’s founder Richard Henry Pratt, in order to gain ‘a civilized language, life, and

purpose’ (‘Ephemera relating to Tom Torlino’). The idea was that this school, and all it offered the

boy, was ultimately for his own good.

ACTIVITY

1 Look at the two pictures of Tom

Torlino and list the ways in which his

appearance has changed.

2 Why do you think Richard Henry

Pratt and the staff of the Carlisle

Indian Industrial School were so keen

to change their students’ physical

■■ Left: A young man from the Navajo Nation, known as Tom Torlino aged 22 in 1882.

appearances?

Right: Tom three years later. Tom was with the school for five years

5 Knowledge and Indigenous Societies 147

474314_05_TK_IBD_4TH_ED_147-181.indd 147 2/29/20 12:43 PM

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the United States’ expansion into the Great Plains of

the North American continent was nearly complete. California and Oregon on the west coast of

the continent had already become states, leaving only the Rocky Mountain territories and the

western plains to be incorporated into the Union. The number of Indigenous people that had been

living in what would become the United States had been steadily diminishing since the arrival

of Europeans in the sixteenth century, and at the close of the nineteenth century it was a widely-

held belief that the Native Americans and their cultures would ultimately disappear. While not a

solution to the diminishing numbers, assimilation into the dominant culture was considered at

the time the only opportunity to support individual Indigenous peoples; to save the individual,

they would need to stop being part of their Native tribe and become a fully enculturated ◆◆Enculturated: To

citizen of the United States. Towards this goal, Richard Henry Pratt, a United States Civil War learn the basic rules,

beliefs and practices of

commander, working in conjunction with the United States government, opened The Carlisle

a culture. Most of us are

Indian Industrial School in 1879. His goal was one he believed to be charitable: enculturated to our native

culture just by growing up

When we cease to teach the Indian that he is less than a man; when we recognize

in it. Some of us move to

fully that he is capable in all respects as we are, and that he only needs the a new culture and have

opportunities and privileges which we possess to enable him to assert his to learn the basic beliefs

humanity and manhood; when we act consistently towards him in accordance and practices of that new

culture.

with that recognition; when we cease to fetter him to conditions which keep him in

bondage, surrounded by retrogressive influences; when we allow him the freedom

of association and the developing influences of social contact – then the Indian

will quickly demonstrate that he can be truly civilized, and he himself will solve

the question of what to do with the Indian. (‘Excerpt from Pratt’s speech’)

For 30 years, the school took young Native Americans away from their lands, their homes and

their families and sent them to the Carlisle School in southern Pennsylvania. Over the duration

of the school’s life, nearly 10 000 Indigenous boys and girls were made to be less like what they

were at birth and more like what the new country thought they should be. They were forced to

abandon their language and their religions and, under harsh military discipline, learn English,

Christianity and everything it meant to be a US citizen at the close of the nineteenth century.

■■ Richard Pratt (seated

on the bandstand) with a

class of Carlisle students.

Tom Torlino is seated in

the front row, first on

the left

148 Optional themes

474314_05_TK_IBD_4TH_ED_147-181.indd 148 2/29/20 12:43 PM

Pratt’s falsely charitable belief that he was improving their lives was built on a deeper assumption

that the people needed improving. Despite the fact that their cultures were getting on happily KNOWLEDGE

QUESTION

with life for thousands of years before the Europeans arrived, there was the pervading notion that

they needed to be ‘civilized’. How have

Pratt argued that: government

education policies

it is a great mistake to think that the Indian is born an inevitable savage. He is born a and systems

blank, like all the rest of us. Left in the surroundings of savagery, he grows to possess compromised

a savage language, superstition, and life. We, left in the surroundings of civilization, the transmission

grow to possess a civilized language, life, and purpose. Transfer the infant white to of Indigenous

knowledge?

the savage surroundings, he will grow to possess a savage language, superstition,

and habit. Transfer the savage-born infant to the surroundings of civilization, and he

will grow to possess a civilized language and habit. (‘Excerpt from Pratt’s speech’)

Pratt’s attitude towards the Indigenous populations, their cultures and their individual capacities

was not uncommon; it is a view shared by colonizing cultures the world over.

The United Nations estimates that there are currently over 370 million Indigenous peoples

living across 70 countries worldwide, or between 15 and 20 per cent of the world’s population.

This may seem like more than you would expect, but consider this: in 1492, Columbus arrived

from Spain at the island of Hispaniola where Haiti and the Dominican Republic are today. It

is estimated that at the time there were about 3 million Native people living there. Within a

generation, because of disease and violence, there remained about 11 000 (Lord). This, again, is

the story of colonization’s impact on Native populations around the world. As the cultures fade

away, so too do their languages, their rituals, their traditions and their unique way of life.

There is a huge diversity across the groups who are recognized as Indigenous, but there is

one common theme to their stories, that of being part of a group which is under threat by

some other dominant society and culture. Caught in the pervasive power of a ‘global society’,

the Indigenous cultures in every corner of the world are struggling to survive. As the world

becomes more and more similar, the links to specific geographical regions and traditions

become harder and harder to maintain. Aside from Antarctica, each of the planet’s continents

has been witness to the process of colonial expansion and the weakening of Indigenous

societies’ ties to their own lands. The histories and challenges faced by Indigenous cultures

have become more well-known over the last half century and the aim of this chapter is to

further explore what have been called ‘Indigenous knowledge systems’. Unfortunately, the

Carlisle School’s founder, Richard Henry Pratt, was not alone in his assumption that the

Indigenous systems were simply a poor shadow of the ‘right’ way to know the world, but this

chapter hopes to provide a framework and an understanding of Indigenous knowledge systems

in a way that brings out their value for the future.

ACTIVITY

Identify and research an Indigenous culture. It could be one in your own country or on the other

side of the world. Perhaps you belong to an Indigenous culture.

1 In what ways do you think that culture is under threat by a dominant culture?

2 How has the threatened culture tried to reassert itself in the face of the dominant culture?

3 Can you articulate the struggle for survival in terms of knowledge?

4 Keep in mind what you find out as you read through the rest of the chapter. Does what we

discuss have relevance to the culture you’ve studied?

5 Knowledge and Indigenous Societies 149

474314_05_TK_IBD_4TH_ED_147-181.indd 149 2/29/20 12:43 PM

You might also like

- The Thomas Indian School and the "Irredeemable" Children of New YorkFrom EverandThe Thomas Indian School and the "Irredeemable" Children of New YorkNo ratings yet

- Foundations of Education Chapter 1Document94 pagesFoundations of Education Chapter 1Sheilla Mae Baclor Bacudo100% (4)

- Module-3 CLMD4AUCSPSHSDocument8 pagesModule-3 CLMD4AUCSPSHSJemina PocheNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Culture, Elements of Culture and CharacteriticsDocument32 pagesMeaning of Culture, Elements of Culture and CharacteriticsMuhammad WaseemNo ratings yet

- What Is CultureDocument7 pagesWhat Is CultureVarun TomarNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society and Politics: Quarter 1 - Module 3: Cultural Relativism and EthnocentrismDocument19 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society and Politics: Quarter 1 - Module 3: Cultural Relativism and EthnocentrismDaisy OrbonNo ratings yet

- Pak Handi General American ValuesDocument5 pagesPak Handi General American ValuesRival DheanNo ratings yet

- MeetsDocument6 pagesMeetsapi-667026662No ratings yet

- ReviewerDocument12 pagesReviewerUnoNo ratings yet

- Finale Term PaperDocument6 pagesFinale Term Paperapi-275660593No ratings yet

- Q1 Ucsp Notes (Done)Document12 pagesQ1 Ucsp Notes (Done)ericka khimNo ratings yet

- 3.2 - Taking ActionDocument4 pages3.2 - Taking ActionjoshrupertNo ratings yet

- ExceedsDocument5 pagesExceedsapi-667026662No ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society, and Politics: Vinz Oliver A. Pedrano Grade 12 - STEM 1Document6 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society, and Politics: Vinz Oliver A. Pedrano Grade 12 - STEM 1Oliver pedranoNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society, and Politics: Vinz Oliver A. Pedrano Grade 12 - STEM 1Document6 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society, and Politics: Vinz Oliver A. Pedrano Grade 12 - STEM 1Oliver pedranoNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society and Politics: Quarter 1 - Module 3: Cultural Relativism and EthnocentrismDocument19 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society and Politics: Quarter 1 - Module 3: Cultural Relativism and EthnocentrismGrace06 Labin100% (1)

- Kartilya NG KatipunanDocument13 pagesKartilya NG KatipunanAra Mae BordeosNo ratings yet

- 1st Quarter Exam UcspDocument5 pages1st Quarter Exam UcspJoanna Mae BalandayNo ratings yet

- 1st Long Exam in UcspDocument6 pages1st Long Exam in UcspKristine AnnNo ratings yet

- 1st Long Exam in UcspDocument6 pages1st Long Exam in UcspKristine AnnNo ratings yet

- Native American Thesis TopicsDocument5 pagesNative American Thesis TopicsWritingServicesForCollegePapersAlbuquerque100% (2)

- Types of EditorialDocument7 pagesTypes of EditorialMark David Abin ValgunaNo ratings yet

- Pre-Colonial Cultures and Communications in The PhilippinesDocument10 pagesPre-Colonial Cultures and Communications in The PhilippinesFrost TreantNo ratings yet

- Cajete 1994-Look To The Mountains, SelectionsDocument70 pagesCajete 1994-Look To The Mountains, SelectionsAstrid PickenpackNo ratings yet

- Rizal Module1Document4 pagesRizal Module1Ralph AuxNo ratings yet

- Textbook 2 - Chapter 1Document54 pagesTextbook 2 - Chapter 1Trần Lê Quỳnh NhưNo ratings yet

- UCSP - Society 1st Quarter - QCDocument44 pagesUCSP - Society 1st Quarter - QCYvonne John PuspusNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture Society and PoliticsDocument29 pagesUnderstanding Culture Society and PoliticsHaden HinayNo ratings yet

- Colonial EducationDocument12 pagesColonial EducationNauman ZafarNo ratings yet

- Week 2 - First Nations EducationDocument4 pagesWeek 2 - First Nations EducationVivian PNo ratings yet

- Paulo Freire and His Pedagogy of The OpressedDocument9 pagesPaulo Freire and His Pedagogy of The OpressedApril Ann Krizel GalangNo ratings yet

- Colonial Genocide in Indigenous North America Edited by Woolford, Benvenuto, and HintonDocument34 pagesColonial Genocide in Indigenous North America Edited by Woolford, Benvenuto, and HintonDuke University Press100% (2)

- Chapter 2 World Roots of American EduDocument9 pagesChapter 2 World Roots of American EduhonglylayNo ratings yet

- Chapter 16 LajimodiereDocument7 pagesChapter 16 LajimodiereXenna McDougall (2024)No ratings yet

- Part 2 Group Work (Group11)Document30 pagesPart 2 Group Work (Group11)Nguyễn Thanh ThảoNo ratings yet

- Special Interest: Empathy Mapping in Social StudiesDocument7 pagesSpecial Interest: Empathy Mapping in Social StudiesscottmpetriNo ratings yet

- 21st FinalDocument6 pages21st FinalSeth SusasNo ratings yet

- The Indian To-day The Past and Future of the First AmericanFrom EverandThe Indian To-day The Past and Future of the First AmericanNo ratings yet

- Foundation of Education 1Document3 pagesFoundation of Education 1Mai MejiaNo ratings yet

- The Historical Foundation of Education General ObjectivesDocument13 pagesThe Historical Foundation of Education General ObjectivesJuvy Mae Delos Santos - DinaluanNo ratings yet

- Native American Education and Boarding SchoolsDocument5 pagesNative American Education and Boarding SchoolsDiana CorbuNo ratings yet

- Module 4Document3 pagesModule 4Phobelyn ZamudioNo ratings yet

- Claudine ActivitiesDocument36 pagesClaudine ActivitiesClaudine LeonorasNo ratings yet

- An Indigenous History of Education in Japan and AustraliaDocument41 pagesAn Indigenous History of Education in Japan and AustraliaguillerminaespositoNo ratings yet

- Hill 1995Document9 pagesHill 1995Sahir JamalNo ratings yet

- Native American Culture Thesis StatementDocument5 pagesNative American Culture Thesis Statementafkodpexy100% (2)

- Understanding Culture, Society and Politics: Quarter 3 - Module 2Document9 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society and Politics: Quarter 3 - Module 2Roberto Dequillo0% (1)

- The Spiritual Legacy of The American Indian (Joseph Epes Brown) PDFDocument8 pagesThe Spiritual Legacy of The American Indian (Joseph Epes Brown) PDFIsrael100% (1)

- Residential Schools Canada - EditedDocument6 pagesResidential Schools Canada - EditedJohn Muthama MbathiNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of EducationDocument43 pagesPhilosophy of EducationRyan J. BermundoNo ratings yet

- Residentialschools EnglishDocument7 pagesResidentialschools Englishapi-299934384100% (1)

- Thailand-A Loosely Structured Social System: Race, Siam. SiamDocument13 pagesThailand-A Loosely Structured Social System: Race, Siam. SiamYe Kyaw AungNo ratings yet

- GE ENG 1 (430-600 PM) Week 2Document12 pagesGE ENG 1 (430-600 PM) Week 2Danica Patricia SeguerraNo ratings yet

- American CultureDocument7 pagesAmerican CultureJoseph SephNo ratings yet

- RIzal AssessmentsDocument17 pagesRIzal AssessmentsKaren Joy DaloraNo ratings yet

- Campasas Module 7Document6 pagesCampasas Module 7Pat RiciaaNo ratings yet

- Rizal ChildhoodDocument2 pagesRizal ChildhoodKenneth MallariNo ratings yet

- Grade 11 Module HistoryDocument5 pagesGrade 11 Module HistoryDulce Amor Christi LangreoNo ratings yet

- Understanding Society and Culture Through LiteratureDocument49 pagesUnderstanding Society and Culture Through Literaturemithunarjun10108No ratings yet

- Graphing Strategies in PhysicsDocument4 pagesGraphing Strategies in PhysicsAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- A2. Fluids and Fluid Dynamics1 MSDocument11 pagesA2. Fluids and Fluid Dynamics1 MSAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- HackingSTEM Wavemachine InstructsDocument5 pagesHackingSTEM Wavemachine InstructsAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- IB Physics Formula Booklet 2025Document8 pagesIB Physics Formula Booklet 2025Ahmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Pythagorean Theorem H.WDocument2 pagesPythagorean Theorem H.WAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- G10 Research Equations of UA MotionDocument2 pagesG10 Research Equations of UA MotionAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Projectile Motion and Vectors-10-1-Quiz2Document2 pagesProjectile Motion and Vectors-10-1-Quiz2Ahmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Types of ForcesDocument2 pagesTypes of ForcesAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- 1617 SI Physics SL ExamDocument23 pages1617 SI Physics SL ExamAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Paper 3Document17 pagesPaper 3Ahmad OmarNo ratings yet

- TB MSDocument13 pagesTB MSAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Option D AKDocument2 pagesOption D AKAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- 1617 SI Physics SL Exam MSDocument6 pages1617 SI Physics SL Exam MSAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Topic I MCQ HL OldDocument27 pagesTopic I MCQ HL OldAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- 7.3 Formative TZ1Document13 pages7.3 Formative TZ1Ahmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Topics 1,2,6 Summative SLDocument14 pagesTopics 1,2,6 Summative SLAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Topic 12.2 Formative MSDocument7 pagesTopic 12.2 Formative MSAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Word Games in MechanicsDocument4 pagesWord Games in MechanicsAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Topic 12.2 FormativeDocument10 pagesTopic 12.2 FormativeAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Topic 6 Test 2022Document15 pagesTopic 6 Test 2022Ahmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Forces and Motion 2022Document43 pagesForces and Motion 2022Ahmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Topic 2.1 FormativeDocument3 pagesTopic 2.1 FormativeAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- BoyleDocument8 pagesBoyleAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Topic 6 TestDocument9 pagesTopic 6 TestAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Facts Vs OpinionDocument7 pagesFacts Vs OpinionAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Markscheme: November 2011Document16 pagesMarkscheme: November 2011Ahmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 MCQ HLDocument7 pagesTopic 1 MCQ HLAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Atom An of Diameter Nucleus A of DiameterDocument11 pagesAtom An of Diameter Nucleus A of DiameterAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Answer All Questions. Write Your Answers in The Boxes ProvidedDocument3 pagesAnswer All Questions. Write Your Answers in The Boxes ProvidedAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Answer All Questions. Write Your Answers in The Boxes ProvidedDocument4 pagesAnswer All Questions. Write Your Answers in The Boxes ProvidedAhmad OmarNo ratings yet

- Gerund/Infinitive A. Put The Verbs in Brackets Into The Correct Form: Gerund or InfinitiveDocument2 pagesGerund/Infinitive A. Put The Verbs in Brackets Into The Correct Form: Gerund or InfinitiveΕυρύκλεια ΦιλιππίδηNo ratings yet

- Claribel Amor M. Juromay Grade 8 March 4, 2020 English First QuarterDocument5 pagesClaribel Amor M. Juromay Grade 8 March 4, 2020 English First QuarterClaribel Amor Maguate - JuromayNo ratings yet

- Worksheet N 04 Passive VoiceDocument3 pagesWorksheet N 04 Passive VoiceSergio SilvpvNo ratings yet

- Fyba Bcom BSC Subject Group Course CodeDocument3 pagesFyba Bcom BSC Subject Group Course CodeSTARK GAMING YTNo ratings yet

- 1 - Who's CountingDocument1 page1 - Who's CountingDee WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Merchant of VeniceDocument124 pagesMerchant of VeniceYadnesh BhosaleNo ratings yet

- Conditional Sentences ExercisesDocument2 pagesConditional Sentences ExercisesCrisNo ratings yet

- Informator 1 2007 UkDocument4 pagesInformator 1 2007 UksiviigiNo ratings yet

- Base Form Simple Past Past ParticipleDocument9 pagesBase Form Simple Past Past ParticipleAna PoleoNo ratings yet

- Ma LinguisticsDocument24 pagesMa Linguisticstariq314No ratings yet

- Jadwal Dapodik GSL SMK Mutu Ta 2020-2021Document16 pagesJadwal Dapodik GSL SMK Mutu Ta 2020-2021Wahyu RetnoningsihNo ratings yet

- Classroom Interaction and Second Language AcquisitionDocument38 pagesClassroom Interaction and Second Language AcquisitionDesfianurardhi DesfianurardhiNo ratings yet

- FCE Use of English Part 2, Test 1 - Christmas FlightDocument2 pagesFCE Use of English Part 2, Test 1 - Christmas FlightSTUARNo ratings yet

- Has To and Have ToDocument4 pagesHas To and Have Torian ripcurlNo ratings yet

- b1 Diagnostic Test Tests - 81423Document9 pagesb1 Diagnostic Test Tests - 81423Thu Hà Nguyễn100% (1)

- DLP LO4 Various Dimensions of Philippine Literary History (S)Document28 pagesDLP LO4 Various Dimensions of Philippine Literary History (S)Juliana ChristineNo ratings yet

- Typing Speed (AutoRecovered)Document8 pagesTyping Speed (AutoRecovered)Mufizul islam NirobNo ratings yet

- 现代汉越语声调对比初探 bao gồm bản check đạo văn Phạm Thu Phương Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Huyền 2T20 Tiểu luận Ngữ Âm T20Document35 pages现代汉越语声调对比初探 bao gồm bản check đạo văn Phạm Thu Phương Nguyễn Thị Ngọc Huyền 2T20 Tiểu luận Ngữ Âm T20phương anh nguyễnNo ratings yet

- Contoh Narative Text (Timun Mas)Document16 pagesContoh Narative Text (Timun Mas)rusli_ok0% (1)

- Baslp Annual09Document84 pagesBaslp Annual09Ðèépü BäghêlNo ratings yet

- Enfeites 2Document67 pagesEnfeites 2Rose MoonNo ratings yet

- KOMDocument248 pagesKOMmedy mahasenaNo ratings yet

- Spotlight 2014 01Document80 pagesSpotlight 2014 01ym maNo ratings yet

- CatalogoDigital PDFDocument47 pagesCatalogoDigital PDFFelipe Friz SotoNo ratings yet

- Zarmina CV 111Document3 pagesZarmina CV 111Zarmina AziziNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Psycholinguistics Week 5: Teacher: Zeineb AyachiDocument16 pagesAn Introduction To Psycholinguistics Week 5: Teacher: Zeineb AyachiZeineb AyachiNo ratings yet

- Dialog Prestasi 2 SMK Bandau - JPN 21.10.2020Document40 pagesDialog Prestasi 2 SMK Bandau - JPN 21.10.2020azizhasNo ratings yet

- The Present PerfectDocument17 pagesThe Present PerfectErly ChavezNo ratings yet

- 10th Activity Sheet 2021Document8 pages10th Activity Sheet 2021Pooja KoreNo ratings yet

- Crossword Puzzle RubricsDocument1 pageCrossword Puzzle Rubricsapi-361774825No ratings yet