Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

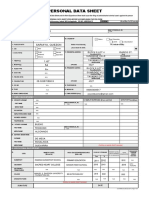

63 viewsStii B 00440 - 314055

Stii B 00440 - 314055

Uploaded by

Joyce BuenoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5835)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- PDF PDS 2017Document4 pagesPDF PDS 2017Joyce BuenoNo ratings yet

- MA Clinical CurriculumDocument2 pagesMA Clinical CurriculumJoyce BuenoNo ratings yet

- 4 ACE Review Center Exam Reviewer Around 900 Items With AnswersDocument162 pages4 ACE Review Center Exam Reviewer Around 900 Items With AnswersJoyce BuenoNo ratings yet

- 1 READ FIRST - Application Procedure 2023-2024Document4 pages1 READ FIRST - Application Procedure 2023-2024Joyce BuenoNo ratings yet

Stii B 00440 - 314055

Stii B 00440 - 314055

Uploaded by

Joyce Bueno0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

63 views230 pagesOriginal Title

STII-B-00440_314055

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

63 views230 pagesStii B 00440 - 314055

Stii B 00440 - 314055

Uploaded by

Joyce BuenoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 230

FIELD)

peo.

w79

2906

ATENEO DE MANILA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Bellarmine Hall, Katipunan Avenue

Loyola Heights, Quezon City

P.O. Box 154, 1099 Manila, Philippines

Tel.: (632) 426-59-84 / Fax: (632) 426-59-09

E-mail: unipress@admu. edu.ph

Copyright 2005 by Ateneo de Manila University and

Ma. Regina M. Hechanova and Edna P. Franco

Book and cover design by JB de la Pefia

The editors and publisher wish to thank Dr. Leo Fores, owner of

Popo San Pascual’s painting reproduced in the cover.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the written permission of the Publisher.

The National Library of the Philippines CIP Data

Recommended entry:

The way we work : research and best practices

in Philippine organizations / edited by

Ma. Regina M. Hechanova and Edna P, Franco. -

Quezon City : ADMU Press, c2005

iv

1, Personnel management - Philippines.

2. Management - Philippines. I. Hechanova,

Ma. Regina M. II. Franco, Edna P.

HF5549.2.P5 658.3 2005 P044000648

ISBN 971-550-476-0

Table of Contents

Foreword

Preface .

The Psychology of the Filipino Worker

Who is the Filipino Worker? ....

Ma. Regina M. Hechanova, Marilyn A. Uy, and Alfredo Presbitero Jr.

Are there Generational Differences in Work Values? ........... 18

Ma. Valerie Vanessa Claudio-Pascua

The Stress of Juggling Work and Family

Ma. Regina M. Hechanova

Rewards that Matter:

What Motivates the Filipino Employee?

Karen L. Yao, Edna P. Franco, and Ma. Regina M. Hechanova

». 63

Ramon A. Alampay, Ma. Regina M. Hechanova, and Edna P. Franco

Empowering the Service Worker

Transformational Leadership and

Its Impact on Employee Attitudes ................cccccssecseseneeee 77

Ma. Josephine C. Francisco

The Paradoxes of Leadership:

A Profile of Successful Filipino Business Leaders ............... 86

Godofredo A. Lanuza and Zarina Yvette Xenelle S. Wells

Ninn sexnune nme CONtENts

Human Resource Management

in Philippine Organizations ..................0.ccseseeeeseeeeens 107

Facing the Future in HR: Current Trends and Issues ........ 109

Edna P. Franco

Competency Management in Philippine

Organizations: A Multicase Study

Mendiola Teng-Calleja, Angielyn Lee-Tan Riosa,

Mary Lisette Villanueva, and Zarina Yvette Xenelle S. Wells

Do Work-Life Balance Programs Work?

The Petron Experience ..

Jennifer Marie Aguirre-Mateo and Petron HRM Department

Flexible Benefits: The Soluziona Experience .................... 162

Peter Paul V. Cauton

Managing a Factory Closure:

The Nestlé Experience ...

Marcelino C. Pineda, Ma. ery ‘A Alipao,

Renee Fajardo-Valdez, and Mendiola Teng-Calleja

Managing Computer Resistance ...

Ma. Regina E. Estuar, Ma. Regina M. Hechanova,

Elizabeth Patricia M. Grozman, and John Benedict C. Que

Index...

About the ‘Editors and Contributors .

Foreword

TODAY, MORETHAN EVER, practitioners/professionals in the field

of human resource development and management—referred to

here as HR practitioners—have been inundated by the sheer

number of feature articles, essays, journals, researches, books

written by Western and Asian academics and professionals. Most

of the authors agree that HR plays a major role as organizations

come to grips with the myriad challenges confronting them.

However, as one author says, in the absence of clear, quanti-

fied measures of what HR actually contributes (unlike revenues

and production) the real value of HR has yet to be defined.

Still, contemporary experts all highlight the strategic engage-

ment of people as a major source of organizational success.

At this point one might well ask what the authors of this

book have to contribute to already well-discussed and lively

debated topics. For one, as the title and even a cursory review

of the table of contents of the book indicate, the authors present

data and messages that are both provocative and evocative, par-

ticularly for Philippine organizations and for all levels of Filipino

workers. Appropriately, it is suggested here that Filipino HR

professionals use cautious judgment in the application of for-

eign-developed technology. This caution is supported by research

findings which show that Western technology, implemented as

designed, has minimum impact on improving the performance

of Filipino workers.

It becomes an ethical imperative then that HR practitioners

subject foreign technology to a systematic process of adaptation

which is suited to the Filipino worker and the Philippine organi-

vii

viii = _The Way We Work

zational culture. Subsequently evaluation and measurement of

the effectiveness of the technical intervention will again be the

responsibility of the HR professional.

All the studies in this book lead the reader to an increased

understanding and a deeper appreciation of many aspects of HR

concerns and issues. Noteworthy is the article, “Who is the

Filipino Worker?” by Hechanova et al. This might well evolve

into a solidly integrated formulation of the Psychology of the

Filipino Worker. Particularly stimulating is the study by Franco,

“Facing the Future of HR: Current Trends and Issues.” The

study looks at the present and future of HR, asking precisely

where it must go to meet competitive challenges such as global-

ization, technology, profitability, growth, and capacity to change.

The image of HR now, as mere personnel departments that deal

only in policy making, policing, and transacting is outdated. If

organizations in the Philippines are to be competitive, HR pro-

fessionals must shift from a “what I do” to “what I deliver”

mentality; they must fulfill both operational and strategic roles,

must become both police and partners, and must take responsi-

bility for both qualitative and quantitative goals over the short

and long term.

The other articles deal with both employee and: human

resource management in the Philippine context, among many

others: what motivates/empowers Filipino workers; what com-

petency models are suited for Filipino business leaders; how is

one to go about developing “consumer-intimacy” in Philippine

organizations. The preface of this book gives a brief review of

each of the case studies. Accordingly, this expanded knowledge

of the “human/intellectual capital” of organizations should fa-

cilitate the planning and designing of greatly enhanced, and

therefore of more effective performance management programs.

Another unique contribution of this book is that it goes

beyond providing recommendations which are usually a litany of

“shoulds” and “musts,” just short of perfect, perfect, perfect!

Interested but perplexed readers may comment: Great advice,

but how do you make it work? To countermand this, Psyke 2

Foreword

offers research utilization schemes in specific, doable interven-

tions appropriate to the findings of each study.

Furthermore, teachers, trainers, and all facilitators of learn-

ing are expected to integrate or synthesize life’s experiences

within overarching conceptual frameworks, theories, and orga-

nized principles applicable to Filipino learners. The research-based

studies in this book of industrial-organizational concerns and

issues eminently qualify it for this important role in the learning

process.

Psyke volumes are intended to reflect the Ateneo Depart-

ment of Psychology’s areas of concentration. Psyke 2 focuses on

the applied field of industrial and organizational psychology-

human resource and organizational development and

management. The volume has been very ably edited by Edna P.

Franco and Regina M. Hechanova, whose own researches and

case studies are vital inclusions in this book.

A Psyke 2 must have a Psyke 1, and indeed it has. Psyke 1 is

composed of creative works of selected thesis-dissertation writ-

ers, covering topics in Clinical and Counseling Psychology. An

academic paradox reveals whole sets of beautifully bound vol-

umes, which earned for the writers their M.A. and Ph.D. degrees,

ultimately finding rest on the venerable shelves of the Rizal

Library and the Ateneo Department of Psychology where they

stay mainly unread. Psyke 1 recalled them to “active duty” by

translating the technical language into reader-friendly versions

to serve the educated reading public.

The charge of writing a foreword for this book, Psyke 2:

Research and Best Practices in Philippine Organizations, has been

a most delightful experience. I wish to applaud Bopeep Franco

and Gina Hechanova for successfully continuing and even ex-

panding the pioneering tradition of the Department of Psychology.

This innovative spirit is now embodied in the Center for Organi-

zational Research and Development (CORD). Started thirty years

ago as a two-desk, two-person office, boldly named Human

Resources Center (HRC), it envisioned itself as the practicum

arm of the graduate students of psychology who satisfy their

requirements as apprentices to consultancy programs of the Ateneo

faculty and to the Center’s training and development projects.

Escalating its research component, it exceeded its original vision

in various creative ways. Three years ago HRC was renamed

CORD. Its research involvements gave birth to the publication

of this book, Psyke 2.

All of us, the faculty, graduate students, graduates of de-

gree programs and certificate courses, our multisectoral clientele,

are truly grateful beneficiaries of the inspired human transfor-

mation labors of the discipline of psychology.

Carmela D. Ortigas, Ph.D.

Professor of Psychology

Cofounder of HRC and Coeditor of Psyke1

June 2004

Preface

INA DEVELOPING COUNTRY such as the Philippines, and amidst

an increasingly global and competitive business environment,

the quality of human resources is key to our nation’s progress.

Yet what do we know about Filipino workers and how do we

harness their capabilities in order to make our organizations

successful?

Perhaps due to our country’s affinity to the West, it has

been fairly easy to transport Western management practices to

the Philippine setting. But these practices have been transplanted

with little data on whether or not they really work in our cul-

ture. Worse, there is a dearth of researches that attempt to

create indigenous theories and models on how to manage the

Filipino worker and organization. This concern provides the im-

petus for this book.

When we joined Ateneo de Manila University three years

ago as faculty members and as practitioners in what is now

Ateneo Center for Organization Research and Development

(Ateneo CORD), we realized how little information was available

about the psychology of Filipino workers. Our recent review of

researches in industrial and organizational psychology reveals

that only a quarter of research conducted has been published,

mostly in scientific journals that rarely find their way outside

academe. That means there is a wealth of knowledge that is not

shared with the general public or even with the professionals

who could best benefit from them. Thus, we made it our mis-

sion to bridge this gap. Last year, we began the Ateneo CORD

Trendwatcher Series, a venue for academe to share researches

with human resources (HR) practitioners. We received overwhelm-

xi

xii = x The Way We Work

ing response and discovered that people were thirsty for knowl-

edge, and that a partnership could blossom between academe

and industry. We thus decided to put together this book to

showcase recent researches about Filipino workers and organi-

zations.

This book builds upon previous work done by our col-

leagues at the Department of Psychology. The first Psyke edition

was published in 1993 and was titled Essence of Wellness. Coed-

ited by Dr. Carmela D. Ortigas and Dr. Ma. Lourdes Carandang,

the book features researches in Clinical and Counseling Psychol-

ogy. The dream then was that more researches in other fields of

psychology would be featured in subsequent editions. Although

more than ten years hence, we are happy to finally be able to

continue the endeavor—but this time focusing on researches in

industrial and organizational psychology.

In the first section of the book, we present researches that

examine the psychology of the Filipino workers—their values,

motivations, sources of well-being, and others. In the second

half, we take an organizational perspective by presenting re-

search and case studies in human resource management. We

hope that through these articles, heads of organizations, line

managers, and HR professionals may be better informed, have a

broader understanding of the Filipino workers, and be able to

more effectively engage human resources in the Philippines.

Acknowledgments

We believe there is still much to know about how people and

organizations can be managed better. Some of this knowledge is

already there and only needs a voice. Other aspects of this

knowledge are still waiting to be uncovered. When we first

started this project almost two years ago, we just knew there

‘was a vacuum that needed to be filled. We decided to take on

the challenge, not realizing how Herculean the task would be.

Putting together thirteen articles from various groups of authors

‘was quite a feat. There were many months of just waiting for

Preface

aS

revisions because most of our authors held full- or part-time

jobs and had to squeeze in writing of the articles in their already

busy schedules. There were times when we were tempted to just

let the project go. Yet once we embarked on this journey, there

were many whose support and encouragement kept us going.

We are grateful to the companies who opened their doors

for us to do research. We are also thankful for the handful of

organizations who allowed us to document their best practices

so these may be shared with others. We were also blessed to

have graduate students and colleagues who agreed to accom-

pany us on this journey. We are hopeful that this will open the

door to more collaboration and knowledge generation in the

future.

We wish to thank Chin Wong who served as our style edi-

tor, giving us valuable feedback on the articles despite working

under a very tight schedule. We are grateful to the management

board of Ateneo CORD and to our colleagues at the Ateneo de

Manila University, especially those in the Department of Psy-

chology, for their support. We also wish to acknowledge the

visionaries who laid the foundation of the Ateneo Human Re-

sources Center thirty years ago, as well as our predecessors who

built up what we now call Ateneo Center for Organization Re-

search and Development. We are grateful to our mentors who

inspired, honed, and challenged us. Many thanks, too, to our

friends who supported and cheered us on. This book would not

have been possible without the love and support of our fami-

lies—Randi, Kai, Laya, and Andre Alampay, and the Francos.

Thank you for allowing us the space to pursue our dreams.

Finally, we lift this humble contribution to nation building to

Him who is the source of all knowledge.

Ma. Regina M. Hechanova

Edna P. Franco

Ateneo CORD

C@

The Psychology

of the Filipino Worker

INDIVIDUALS ARE THE BUILDING BLOCKS of organizations. Because

they are an organization’s most important resource, it is essen-

tial that we understand their needs, values, and motivations.

“Who is the Filipino Worker?” uses national survey data to ex-

amine the motivations, needs, and wants of a broad spectrum of

workers. In the second essay, we answer the question “Are There

Generational Differences in Work Values? ,” comparing the work

values of parents and their children. “The Stress of Juggling

Work and Family” focuses on the plight of working parents and

how they cope with their dual roles. What rewards matter to the

Filipino worker? This question is answered in a study on what

internal and external rewards are valued by employees. The

issue of whether empowerment works for the Filipino service

worker is tackled in the essay, “Empowering the Service Worker.”

The final two essays in this section focus on Filipino leadership.

“Transformational Leadership and Its Impact on Employee Atti-

tudes” examines how leadership behaviors can influence the

commitment of their subordinates. Finally, “The Paradoxes of

Leadership: A Profile of Successful Filipino Business Leaders”

presents a personality profile of successful business leaders.

A ho is the Filipino Worker?

Ma. Regina M. Hechanova, Marilyn A. Uy, and Alfredo Presbitero jr.

IN A TIME OF UNRELENTING CHANGE and extremely tough com-

petition, companies face the daunting task of determining

sustainable strategic advantages. However, there are very few

competitive advantages that can be maintained for a long time.

Strategies can be copied, resources bought, technology created.

Hence, more and more organizations are looking at human capi-

tal as the true source of sustainable competitive advantage.

After all, people are the creators of strategy, the caretakers of

resources as well as the designers and implementers of technol-

ogy. Thus, in a developing country such as ours—where natural

resources are dwindling, economic resources are scarce, and

technology is lagging—our redemption will be in the wealth of

resources that exists within the Filipino worker.

There are more than 35 million Filipinos in our work force

today. They represent half of the country’s population and two-

thirds of the adult population (Philippine Labor Statistics 2003).

If our country is to grow economically, we need to harness

3

Accom moacan nw The Way We Work

these workers to participate and become truly productive

members of organizations. How do we do this? The first requi-

site is to know who Filipino workers are. What is their

demography? What are their values? What do they look for ina

job? These are the questions we have attempted to answer in

this essay.

The Studies

We have tried to answer these three questions through second-

ary analysis of the existing data. Specifically, we looked at two

recent studies of Filipino workers. The first data set we used

was the 2001 Philippine Round of the World Values Survey

(WVS) conducted by the Social Weather Stations (SWS) for the

Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research.

The Philippine survey had a sample size of 1,200 adult respon-

dents (eighteen years old and above). Respondents were evenly

divided into four major study areas: National Capital Region

(NCR), Luzon (areas outside of the NCR but within Luzon), Visayas,

and Mindanao. From this sample, we extracted the data on only

those who were working. Thus, a total of 608 working respon-

dents were included in our study.

The second data set analyzed was the 1997 Work Orienta-

tion Study, also conducted by the SWS, this time for the

International Social Survey Program (ISSP). As with the WVS,

the original data had a sample size of 1,200 adults evenly drawn

from NCR, Luzon (areas outside of the NCR but within Luzon),

Visayas, and Mindanao. We again used responses only from

those who were currently working. This resulted in an effective

sample size of 636, two-thirds of whom were male. These re-

spondents represented 113 classifications of occupations.

In addition to these surveys, additional information was

obtained from the Bureau of Labor and Employment Statistics,

National Statistics Coordination Board, National Commission on

the Role of Filipino Women, and the Securities and Exchange

Commission.

Who is the Filipino Worker? sneer,

The Profile of the Filipino Worker

According to the October 2003 Bureau of Labor and Employ-

ment Statistics, a quarter of the workforce is twenty-four years

old and below. Most of the workers are found in the NCR,

Cavite, Batangas, Laguna, Rizal, Quezon, and Central Luzon.

Most are in retail and trade (16 percent), manufacturing (9

percent), and transportation, storage, and communication (6

percent). Although literacy rates are high, only half of our work-

ers are high school graduates and only about one of five workers

has completed college education.

Based on data from the 1997 Work Orientation Survey,

majority (78 percent) of workers are married with an average of

three kids. More than one-third (37 percent) of our workers are

in dual-career families where both father and mother work.

However, males are still the chief wage earners in four of five

families.

Although majority (65 percent) of workers are employed

full-time, there are around 5 million workers who can be con-

sidered underemployed, or people who desire to work more

hours but typically work less than forty hours a week. As of

August 2003, the median monthly pay of a worker in the non-

agricultural setting was P6,764. Workers in unionized

organizations receive 29 percent higher pay than those in

nonunionized companies. Workers in multinational corporations

also receive 54 percent higher pay than those in nonmultinational

corporations (Bureau of Labor and Statistics 2003).

However, poverty remains a pressing issue in the country.

Sadly, more than one-third, or a total of 26.5 million Filipinos,

live below the poverty line (National Statistics Coordination Board

2002). Not surprisingly, more than half of workers in the 1997

Work Orientations Survey consider themselves poor.

The Meaning of Work

Why do people work? For most respondents in the 1997 Work

Orientation Survey, work is seen as a person’s most important

& : oop eWay We Work

activity (88 percent). However, three-fourths also agree that a

job is just a way of earning money. Given the high incidence of

poverty, work is primarily seen as a means of meeting basic

needs.

Other than a means to survive, however, work also pro-

vides a venue for individual growth. Majority of respondents in

the 2001 World Values Survey agree that one needs to have a

job to fully develop one’s talents (94 percent). In fact, 65 per-

cent also believe that people who don’t work become lazy. In a

focus group discussion (FGD) conducted by the Personnel Man-

agement Association of the Philippines (2000) one FGD

participant stated, “Work is core to my existence as an indi-

vidual because I have tested myself. I tried staying at home . . .

parang something was missing. . . . I was always a working wife

. so for me work is a vehicle for fulfillment in terms of

talents and abilities coming out.”

What Workers Look for in a Job

When asked about things that are of primary importance in

looking for a job, 78 percent of workers in World Values Survey

said that the most important element was good job security, that

is, the company has very minimal risk of closing down. With the

increasing incidence of mergers, acquisitions, downsizing, and

closures, the value for job security is understandable. In fact,

only 28 percent of respondents in the Work Orientation Survey

did not worry about the possibility of losing their jobs. Disturb-

ingly, one-third of respondents also reported that they do not

have written contracts with their employers.

Other than job security, 38 percent of the World Values

Survey respondents mentioned “good pay” as a primary consid-

eration. Indeed, having a job with handsome pay is extremely

important for most Filipino workers, as most are concerned

with making both ends meet. This reality is clearly supported by

the 1.06 million overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) all over the

world (National Statistics Office 2003).

Who is the Filipino Worker? _ I

Beyond pay and job security, workers listed many other

characteristics that are important for them. These are summa-

rized in table 1 below.

Table 1. What Filipino Workers Look for in a Job

E

Factor

Good pay

Job security

A job that meets one’s abilities

A position of responsibility

A job respected by people in general

A job in which you can achieve something

A job that is interesting

Good hours

Not too much pressure

An opportunity to use initiative

Generous holidays

OONDOAAONHE

a

oO

Although workers appear to be quite clear on what they

want in a job, it seems that many do not have the jobs they

want. Although 87 percent of the Work Orientation Survey re-

spondents affirm that they are proud of the work they do, more

than half (54 percent) also agree with the statement, “Given the

chance, I would change my present type of work for something

different.” The reasons for such an attitude are evidently due to

the discrepancy between the factors they think are important

and what they actually have. Although workers agree that their

current jobs allow them to help others and are useful to society,

they perceive job security, income, and career opportunities as

limited. In fact, 40 percent of workers in the Work Orientation

Survey reported that their jobs use little or almost none of their

skills or experiences. Such discrepancies are perhaps the driving

force in the increase in migration and overseas workers.

De Way We Wark

If given a choice, three of four respondents in the Work

Orientation Survey prefer to be self-employed rather than be an

employee. The lure of self-employment is perhaps explained by

a twenty-three-country study which shows that the self-employed

are more satisfied with their work compared to employed per-

sons because of the autonomy that being one’s own boss affords

(Benz and Frey 2003).

When asked about where they would rather work, majority

of the Work Orientation Survey respondents said they prefer to

work in a large firm (72 percent) than in a small firm (28

percent). This is quite understandable because large firms are

perceived to be more stable than small ones. Compensation and

benefits also tend to be higher in larger firms. In addition,

opportunities for advancement tend to increase with organiza-

tion size. Interestingly, work in government or civil service is

preferred (52 percent) over working in a private business (38

percent). One explanation for this is that the increasing

downsizing among private firms has made workers perceive the

government as the most stable employer in the country.

Happiness and Satisfaction

Despite the grim economic picture, the positive spirit of the

Filipino still shines through. Based on the Work Orientation

Survey, Filipino workers are generally happy with their situa-

tion. However, level of happiness is significantly correlated with

their income, and satisfaction with their financial condition.

That is, happy workers are those who are satisfied with their

financial situation and their earnings.

The results also reveal that happiness is a function of job

level. Those who are in the higher ranks are happier than those

in lower-level jobs. This is understandable because higher-level

jobs often mean greater autonomy, challenge, and compensa-

tion—factors that Filipinos look for in a job. Perhaps this also

explains why one-third of OFWs are laborers and unskilled work-

ers—individuals who would typically hold low-level jobs (National

Statistics Office 2002). On the other hand, there are some

differences between gender and industries. Females in the agri-

cultural sector register the lowest happiness scores. Perhaps it is

in this group of workers that we find the widest gap between

work preferences and actual working conditions.

In terms of job satisfaction, workers appear to be some-

what satisfied with their current jobs. Workers in urban areas

report greater satisfaction than those in rural areas. Why is this

so? One possible explanation is that work tends to be concen-

trated in urban areas, so that workers in cities have a much

wider choice in terms of jobs. Indeed, the Work Orientation

Survey results reveal that urban workers have higher incomes

and report more opportunities for advancement in their jobs.

Urban workers—compared to rural workers—rate their jobs as

more interesting, meaningful, and useful to society.

What is Important for Filipino Workers?

The family holds a very significant place in the Filipino culture

as reflected in the World Values Survey where 99 percent of par-

ticipants rated family as “very important.” Work comes in a close

second with almost 96 percent of the respondents rating it as a

very important element in their life. The crucial role of religion

in the lives of most Filipinos is evident as it was rated “very impor-

tant” and “rather important” by 96 percent of the respondents.

Service to others is also rated quite highly, garnering 93 percent

for the “very important” and “rather important” responses com-

bined. Only 38 percent of the participants of this study consider

their friends as “very important,” whereas half of them rate

friends as “rather important.” Leisure and politics are least im-

portant to workers. These findings validate a research study

conducted by the Resources and Inner Strategies for Excellence,

Inc. (RISE, Inc.) for the Personnel Management Association of

the Philippines (PMAP) which reveals that the common priorities

of Filipino workers are family, relationships and friends, work

and career, personal development, spirituality, and health.

Le Way We Wor

Although the value for family and work is true across all

workers, certain differences did emerge by age. In the PMAP

study one respondent remarked, “When I was younger, work

would be on top. Now family is at the top.” Relationships or

friends are also mentioned as a priority. Younger workers, how-

ever, value friends more than older workers do. Service to others

is valued more by older workers than younger ones. All these

findings are consistent with individual development theories that

explain how people’s values change with life stages.

Work vs. Leisure

Filipinos, in general, place a substantial premium on work com-

pared to leisure or recreation. Both females and males agree

that it is work, not leisure, that makes life worth living. Indeed,

82 percent of respondents to the World Values Survey agree that

work should always come first even if it means less spare time.

Attitudes toward leisure, however, appear to be influenced

by educational attainment and income level. The World Values

Survey reveals that workers with more education and higher

incomes place a higher value on leisure than those with less

education and income. One explanation for this is that educa-

tion and income are related; generally, the more educated have

higher paying jobs. Consequently, the higher the income, the

more likely they are to have discretionary funds for leisure. On

the other hand, the relationship between educational attainment

and value for leisure may also be attributed to the liberal educa-

tion received in college that espouses a holistic understanding of

quality of life, which includes noneconomic pursuits such as

arts and recreation.

Yet another way of looking at this is through the lenses of

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Maslow (1970) proposed that

people’s needs fall into a hierarchy with the most basic being

physiological needs (food, shelter, relief from pain). This is fol-

lowed by safety and security needs (freedom from threats or

surroundings), belonging (friendship, affiliation, love), esteem

is the Filipino Worker?

(self-esteem and respect from others), and self-actualization (ful-

filling oneself by maximizing use of abilities, skills, and potentials).

Maslow says lower-order needs must be satisfied before higher-

order needs. Although there have been questions about whether

this is true for all individuals, the results do suggest that for

lower-income workers, survival takes priority over leisure.

Well-being and Work-Life Balance

Given the amount of time work occupies in our lives, it is not

surprising that it is a major source of stress. A quarter of the

workers in the Work Orientation Survey report that they always

come home from work exhausted. Twenty-two percent report

that this often happens to them, too. Stress level and exhaustion

are highest among lower-income workers. Workers in rural ar-

eas are more stressed and likely to feel exhausted at the day’s

end compared to those in urban areas. This is likely since these

workers tend to have jobs that entail manual labor and not have as

much flexibility in terms of work hours. There is also a positive

correlation between work stress and number of hours worked.

The World Values Survey asked workers about the frequency

of activities outside work. Results show that workers spend

time with friends, work colleagues, and parents or relatives.

When asked about their membership in voluntary organizations,

34 percent of workers say they belonged to and volunteer in a

religious organization. However, beyond that, a great majority

of workers do not belong to any voluntary organization. Only

11 percent of workers are members of unions (Bureau of Labor

and Employment Statistics 2003). When asked what they wish

they could spend more time on, 77 percent of the respondents

wanted to spend more time with family.

Gender Roles

The past decades have seen an increasing number of women in

the workplace. In the 1960s, less than a third of the women

12 oo __.The Way We Work

worked; today, more than 50 percent of female adults work

(Bureau of Labor and Employment Statistics 2003). Perhaps

this has led to a change in gender roles. Although males are

predominantly the chief wage earners, nine out of ten workers

in the World Values Survey agree that both husband and wife

should contribute to the household income.

With such a change, it is not surprising that there is

more openness toward working women. Although majority

(85 percent) of respondents in the Work Orientation Survey

believe that being a housewife is just as fulfilling as working for

pay, most (72 percent) respondents agree that working mothers

can establish a warm and secure relationship with their children

as those who do not work.

Despite the openness to women joining the workforce, how-

ever, there is still gender inequality in the workplace. Women in

the Work Orientation Survey report less job satisfaction than

men. They agree less than male workers that their work pro-

vides them with high income and opportunities for advancement,

and allows them to work independently.

Although females slightly outpace males in terms of lit-

eracy rate, there still appears to be a “glass ceiling” or an

invisible barrier for women vis-a-vis important positions in many

organizations. The latest data from Securities and Exchange Com-

mission (SEC) show that only 5 percent of chief executive officers

of the top 500 Philippine corporations are women (SEC 2003).

In addition, according to the National Commission on the Role

of Filipino Women, or NCRFW (1995), women, on the average,

make less than half of what men make even in female-domi-

nated industries.

Aside from a glass ceiling, there is evidence of “glass walls”

that limit women to certain specific sectors or occupations. In the

Philippines, women workers dominate service as well as educa-

tion organizations and tend to be in traditional occupations such

as teachers, nurses, social workers, and sales clerks (Ilo 1997).

Moreover, there appears to be gender stereotyping inside

the household. Two of three female workers who responded to

Who is the Filipino Worker? ___ 7 ; somal 3,

the Work Orientation Survey said they are mainly responsible

for domestic duties, 24 percent say they share duties with their

partners and 10 percent report that others are responsible for

domestic duties. Interestingly, among male workers, only 9 per-

cent report that they are mainly responsible for domestic duties,

whereas 35 percent claim they share domestic duties. Not sur-

prisingly, although majority, or 65 percent, of workers would

prefer full-time work, there is a gender difference, nevertheless.

Seventy percent of male workers, but only 54 percent of women,

want a full-time job.

HR Implications

The findings from the various studies suggest a number of impli-

cations on how best to manage the Filipino worker. In a business

environment where closures and downsizing happen everyday, it

is not surprising that job security has become an important issue

among workers. Organizations that are able to assure stability

will have an advantage in attracting and retaining talent. Yet the

paradox is that in the dynamic world of business, the key to

organizational survival is flexibility. Gone are the days of life-

time employment and more organizations are seeking to prepare

workers for change. How does one reconcile these two appar-

ent contradictions? The secret might just be in being able to

strike a balance in doing both—making sure that workers’ wel-

fare is considered and that downsizing is done only as a last

resort. At the same time, it is important that organizations help

workers change their paradigm of the company as a source of

security in equipping themselves to ensure their marketability as

individuals.

The various studies show that money still does matter.

With more than one-third of the people living below the pov-

erty line, the first priority among Filipino workers is to meet

their basic needs. Offering enticing compensation and benefits

is still a valid means of attracting, retaining, and motivating

workers.

dh esas cmc Ne Way. We Work

Beyond job security and compensation, however, Filipino

workers are clearly looking for jobs that are interesting and

meaningful. In the best of worlds, people get the jobs they

want. In reality, this is not always possible. Nevertheless, find-

ing a good job-person fit is one of the responsibilities of human

resource management, implying the need for effective recruit-

ment and placement practices.

This likewise suggests that organizations should effectively

design jobs because the job itself can be a source of motivation.

According to Hackman and Oldham’s Job Characteristics Theory

(1980), high internal work motivation is a function of the extent

to which workers feel that their work is meaningful; that they

are responsible for the outcome of their work; and that they can

see the results of their work. These psychological states are

created by jobs that allow workers to practice a variety of skills.

Workers find it more meaningful and fulfilling if a job is as-

signed in its entirety compared to piecemeal or assembly type of

work. Tasks that are significant are more motivating than me-

nial jobs. Jobs that provide workers autonomy and discretion in

decision making and work processes make workers feel more

responsible and will, therefore, be more motivated.

Yet all of these are dependent on the growth needs of an

individual. That is, work that has challenge, autonomy, skill

variety, task significance, and identity will work best for work-

ers who are motivated by the individual’s growth needs. This

implies that managers need to get to know their workers on a

more personal level in order to determine their needs and find

effective ways to motivate them.

Workers cited the need for career growth and learning on

the job. Employers are thus challenged to provide mechanisms

and venues for this. Providing training programs, facilitating

career planning, communicating career paths and promotion

criteria, and creating structures for career growth are some

ways that organizations can meet this need.

Beyond career growth and learning on the job, education

in itself is a vital element in our efforts toward economic progress.

Who is the Filipino Worker? As

Education expands one’s opportunities for earning good income.

Sadly, only half of our workers are high school graduates. If our

country is to compete with the world for investments and jobs,

we need to upgrade our workers’ competencies through voca-

tional or formal education. Employers can help by providing

educational assistance and scholarships for those who wish to

finish their studies or pursue higher education.

Despite the increasing number of women in the work force,

gender inequality in the workplace appears to remain. Women’s

incomes are generally less than men’s in similar positions. Men,

moreover, tend to have higher-level jobs than women even if

literacy and educational levels are about the same across gen-

ders, suggesting the need to promote and ensure greater gender

equality in the workplace. Organizations need to look closer

into their recruitment, selection, compensation, and career de-

velopment systems to determine the source of this inequality.

That women tend to congregate in specific sectors (service and

education) and traditional jobs indicates that the discrimination

may be coming from a culture that propagates traditional gen-

der roles. Such gender roles are often created early in an

individual’s life, suggesting that change needs to start in families

and schools. However, organizations can propagate such culture,

too, with the presence of an “old boys’ club” network among their

leaders. Organizations need to realize the impact of such prac-

tices, and create structures and systems to ensure gender equality.

The increasing number of women entering the workplace

and the rise in dual-career couples call organizations to imple-

ment systems and structures to aid working parents. The recent

decade has seen the rise of family-oriented programs such as

flexitime, family leaves, and flexible benefits. The ability of or-

ganizations to provide these will not only address the unique

needs of working parents but also convey the message that the

organization cares about the worker. Because Filipino workers

are very family-oriented, organizations that support this value

will be able to gain the commitment of not just their workers

but of their families as well.

a — eee he Way We Work

The results moreover suggest the need for greater attention

to the plight of workers in rural areas. These workers have half

the income of workers in the urban areas and report greater

stress and less-motivating jobs. The problem of congestion in

urban areas will continue unless development reaches the coun-

tryside and rural workers get more employment choices.

Special attention should be paid to workers in lower-level

jobs. These are the workers who typically earn less and are likely

to feel more stressed. Sadly, these are also the same workers who

do not feel the need for leisure. Is leisure then a luxury only for

those who can afford it? Our answer is no. Stephen Covey

(1989) calls it “sharpening the saw.” He says that renewing

ourselves physically, spiritually, mentally, and socioemotionally

is the single most powerful investment we can ever make in our

life. Toward this end, organizations can help workers with training

programs and work-life balance programs to help sharpen their

physical, spiritual, mental, and socioemotional selves and become

happier, more productive individuals with better quality of lives.

All in all, the results of the various studies show that the

plight of Filipino workers leaves much to be desired. Lack of job

security, long work hours, low wages, and lack of job fit are but

some of the typical issues that the typical Filipino worker faces.

Despite this, we see a picture of the Filipino worker as a gener-

ally happy, family-oriented individual who values work that will

provide both economic rewards and growth. To this end, there

are many things organizations can do not only to improve work-

ing conditions but also to harness the Filipino workers’ motivations

and competencies. Many other countries have benefited from

the capabilities and work ethic of the Filipino worker. It is high

time that we did the same.

References

Benz, M. and B. S. Frey. 2003. The value of autonomy: Evidence from

self-employed in 23 countries. Working Paper No. 173. Institute

for Empirical Research in Economics, University of Zurich.

he Filipino Worker?

Bureau of Labor and Employment Statistics. 2004. The 2003 employ-

ment situationer: The year in review. Labstat updates 8, no. 1

(January). Manila, Philippines.

Covey, 8. 1989. The seven habits of highly effective people. NY: Simon

and Schuster.

Hackman, J. R. and G. Oldham. 1980. Work redesign. Reading, MA:

Addison-Wesley.

Ilo, J. F. 1997. Women in the Philippines. Asian Development Bank.

Maslow, A. H. 1970. Motivation and personality. NY: Harper and

Row.

National Commission on the Role of Filipino Women (NCRFW). 1995.

Filipino women: Issues and trends. Manila, Philippines.

National Statistics Coordination Board Fact Sheet. 2003. 4.3 million

Filipino families are living below the poverty line (October).

National Statistics Office. 2002. 2002 survey on overseas Filipinos.

Manila, Philippines (April).

Personnel Management Association of the Philippines (PMAP). 2002.

A study on perspectives of work-life balance: Its meaning and pro-

cess. Manila, Philippines.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). 2003. Philippines top 5000

corporations. Manila, Philippines.

fre there

Generational Differences

in Work Values?

Ma. Valerie Vanessa Claudio-Pascua

COMPANIES HAVEALWAYS HAD to deal with change. Innovative ones

have continuously adopted new “best practices” in management to

achieve organizational excellence. However, the breakdown of

geographical barriers in the last decade has changed the focus of

organizational change, making it broader in scope and more

fundamental. With competition shifting from merely local to

global, companies are starting to realize that to remain in the

game, they must revisit their core mission and business strate-

gies, and completely reinvent themselves.

One outcome of this process is that companies have flattened

out their organizations to become more flexible, enabling them to

respond more quickly to business changes and customer de-

mands. As a result of this evening out, boundaries that used to

separate older workers from younger workers have dissolved and

workers of different generations are finding themselves working

side by side. On the one hand, such diversity can bring together

wisdom with innovation, balance idealism and pragmatism, and

Are. > there Generational Differences _ in Work Values? . 19

combine risk-taking with stability. On the other hand, differences

between the generations may also. cause conflict and misunder-

standing. Clearly, companies need to identify and understand the

differences between older and younger workers to maximize the

value of diversity in generations.

Why are Work Values Important?

Generational diversity can be defined in a number of worker

attributes—communication style, need for achievement, job sat-

isfaction, or preferences in the work environment, to name a

few. This study focuses on work values because they form a

basic and central part of an individual’s personality. Work val-

ues are enduring beliefs about what is personally desirable,

independent of the unique circumstances of a particular work

situation (Rokeach 1973).

When any employee joins a company he or she carries a

“psychological contract,” or a set of expectations about what he

or she will do for the company, and what the company should

do in return. These expectations are, to a large extent, shaped

by the employee’s work values. Organizations also have unwrit-

ten expectations of their employees and assumptions about how

they should be treated. These are normally manifestations of an

organization’s values and culture. Research has shown that em-

ployees are most productive, satisfied with their jobs, and

committed to a company when their own values are compatible

with those of the organization’s (Acufia 1998). This indicates

that employees first need to recognize some connection between

their company’s value system and their personal beliefs before

they can fully commit themselves at work.

How Values are Formed

There are a number of theories of how work values are formed.

Three major theories will be presented here: generational dif-

ferences, life-cycle model, and occupational perspective.

One school of thought states that the years from secondary

to college education are formative years for the development

and establishment of values and world values. As young people

are socialized into the world and exposed to various ideals

and behavioral norms, they assimilate and test these beliefs and

standards. Throughout their formative years, members of a

certain generation hear the same messages from the family,

school, media, and religious institutions, resulting in a shared

ideology that sets them apart from other generations. Genera-

tions have ideological differences because the social context in

which each generation grew up is different. Thus, every era is

usually marked by dominant societal values that shift with

changes in the political and economic environment. The char-

acteristics of each generation have been linked to their unique

socialization experiences as adolescents and young adults (Pine

and Innis 1987).

Whereas the previous models argue that value orientations

are “locked in” at a particular stage in a person’s development,

others contend that our values continue to change even after

early adulthood. Changes typically occur at particular phases in

our life, which also correspond to certain ages. The life-cycle

model challenges cross-sectional research that rely on a genera-

tional explanation when accounting for differences in young and

older employees’ work values because the variation can be equally

explained by life-stage differences (Rokeach 1973). In other

words, value differences may be more a matter of age than

generation.

Like the life-cycle model, the occupational perspective be-

lieves that our values do not remain stable after a critical period.

The main premise of this perspective is that work values can be

shaped by work experiences. Job positions, for example, carry

corresponding role expectations to which we might align our

values (Super 1957). For example, a rank-and-file employee may

value equality and feel that everyone should get the same re-

wards. However, a manager whose responsibility is to manage

performance may value equity where better performers are re-

Are there Generational

warded more than nonperformers. Thus, the occupational per-

spective provides an alternative explanation for differences in

work values between generations because individuals belonging

to different generations are likely to differ in job positions as

well. This is especially true in societies, like the Philippines,

where age is closely tied to position.

Both the life-cycle and the occupational perspectives main-

tain that values may continue to change in time. However, these

arguments cannot completely dismiss the existence of real gen-

eration-based differences because there is evidence from research

showing qualitative changes in values every decade, even after

age has been taken into account (Smith 2000).

Generational Differences in the West

In the United States, many comparative studies have focused on

generations that have been labeled Baby Boomers and Gen Xers.

Although researchers do not share the exact same definition,

Baby Boomers are individuals who were born between the late

1940s and early 1950s, while Gen Xers are those born be-

tween the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Both generations have been shown to value a balance be-

tween work and personal life, but Baby Boomers have been

found to place higher importance on work. Baby Boomers have

also been described as being more people-oriented. A study on

organizational leadership showed that younger leaders put more

importance on developing their own abilities and careers, whereas

older leaders are more concerned with developing people under

them. Gen Xers’ leadership approach has been described as

more self-focused, less open to compromise, and more strongly

results-oriented. Conversely, the Baby Boomers’ approach is

characterized as calmer and more democratic, and conscious of

organizational traditions (Kabacoff and Stoffey 2000).

Researchers explain these differences along two lines. First,

in terms of experiences while growing up, Gen Xers had more

solitary experiences as a result of having Baby Boomer parents

. ne The Way We Work

who both worked (the so-called “latchkey kids”). Having grown

accustomed to doing things on their own, they tend to seek

some amount of independence at work. Gen Xers were also

more frequently exposed to modern ideas such as those that

challenge authority and that emphasize individual over group

achievement. They were raised during a period of greater and

faster change and hence, they have a stronger bias for action

and quick decisions. Second, the two generations entered the

workforce at different times and under different expectations. If

Baby Boomers believe that the company will take care of them

throughout their careers, Gen Xers see their job as secure so

long as they continue to produce. This may be why some re-

searchers have labeled Gen Xers as “competitive pragmatists”

who perceive the world as having limited opportunities yet are

determined to get their share (Boyatzis and Skelly 1995).

Generational Differences among Filipino Workers?

The main objective of this study was to determine if there are

generational differences in the work values of Filipino employ-

ees. Although many studies have been conducted on Filipino

work values, none has set out to compare work values of Fili-

pino employees belonging to different generations.

Evidence that generational differences might exist was found

in a study on value orientations of two generations of Filipino

student activists. The study found that student activists of the

martial Jaw era and those involved in the 1986 EDSA Revolu-

tion differed in the relative importance they placed on central

life values (Montiel 1992). Although Montiel did not look into

work values per se, we can assume that differences in life val-

ues reflect differences in work values as well.

The Study

In this study, an individual’s generation was determined by his

or her classification as either the parent or the child for every

Are there Generational Differences in Work Values? 23

parent-child pair of respondents. Because both parent and child

had to be working to participate in the study, the “parent”

generation was largely in their fifties and their children in their

twenties.

The sample was selected through convenience and pur-

posive sampling. The sample size was eighty pairs of parents

and children. All were residents of Davao City and worked in

various industries as employees, professionals, or entrepre-

neurs. The ages of parents ranged from 40-66 years and

children’s ages ranged from 16-37 years. About 70 percent

of the parents and 27 percent of the children held manage-

rial or supervisory positions, while the rest held nonsupervisory

positions (i.e., no reporting subordinates). Sixty-three percent

and 52 percent of the parents and children, respectively, re-

ported monthly family incomes between P30,000 and P100,000,

which means that the sample belonged to the middle income

classes.

Work values were measured using a modified version of

Buchholz’s Beliefs about Work (1981) survey questionnaire. Re-

visions were necessary because factor analysis and reliability

analysis using the Filipino sample produced only four meaning-

ful and reliable subscales. This analysis was based on thirty

work-related value statements, which were organized into four

value systems:

° Humanistic Belief System, consisting of statements about

how a job can and should be intrinsically rewarding;

° Marxist-Related Beliefs, measuring egalitarian orienta-

tions with statements about how workers are being

exploited and alienated by the way work is currently

organized;

* Leisure Ethic, referring to beliefs about the importance

of leisure time in relation to work;

* Collectivist Belief System, composed of statements about

the importance of teamwork.

D4 mn - The Way We Work

& - eeceueccmeccamen Ne Way. k

Findings: Managing the Generations

The results of the study reveal that Filipino workers in their

mid-twenties and those in their mid-fifties are more alike than

different. Both generations believe that work should promote

personal growth and development, and that contributing to and

cooperating with the work group is desirable. Results indicate

that parents and children disagree only when it came to Marxist-

related beliefs. The younger generation more strongly agrees

with Marxist statements, an indication that they favor greater

worker participation and empowerment.

The results have implications on how the Filipino workers

expect to be managed. For example, there is no difference in

how much young and more senior workers value learning and

challenges on the job. This indicates that both generations are

willing to try out new things. Companies that are committed to

innovation can capitalize on this enthusiasm and may only need

to make sure that training formats are aligned with the unique

learning styles of young and older workers.

Also, the importance placed on individual growth and de-

velopment justifies the need to restructure jobs and tasks so

that they become steady sources of challenge and stimulation

for workers. Job rotations and formation of special committees

or task forces where workers can be involved are some ways of

making jobs more interesting.

The moderate stance of the two generations regarding lei-

sure suggests that organizations can count on a strong Filipino

work ethic so long as employees feel that their personal lives are

not being sidelined. It is still important for them to achieve a

work-life balance.

Companies can make the most of workers’ commitment by

rewarding exceptional performance with incentives that appeal

to personal concerns and interests, while keeping in mind that

young and older workers have different lifestyles and priorities.

For instance, employees could be offered time off to pursue

their own interests. They might get tickets to concerts or sports

Are there Generational Differences in Work Values? ____ 25

events, gift certificates to restaurants and stores, family vaca-

tion packages, or even contributions to charitable institutions.

This approach communicates the message that the organization,

too, recognizes and supports the importance workers lay on

their personal lives outside work.

No differences were found between generations in terms

of collectivist orientation. This means that group-oriented

motivational techniques, such as organizing work around

teams, can be effective for both groups of workers. This is

because a team-based work structure addresses the need to

be part of a collective. A collectivist orientation emphasizes

personal relationships and nonmaterial rewards (Acufia 1998).

Management and leadership styles that have a “personal touch”

have a good chance of successfully motivating people, as do

fellowship activities that allow coworkers to interact with

each other nonprofessionally.

Praise and recognition for a job well done are just some

examples of nonmaterial rewards. Companies may hold peri-

odic recognition programs or give internal media coverage

for notable performers. Nonmaterial rewards are especially

effective since they bond people to the company and not to

financial rewards, which might heighten their sense of freedom

and mobility.

It should be pointed out, however, that even as there are

no differences in collectivism in terms of generation, there is a

difference in orientation according to age. Younger workers are

less collectivistic (and more individualistic) than older workers.

In fact, the strength of collectivist beliefs is correlated with age.

These findings imply that group-oriented motivational techniques

may work for the younger generation as a general rule, but

companies may want to handle them a little differently by pay-

ing more attention to their need for autonomy.

The only area where the two generations differ is in Marx-

ist-related beliefs. Younger workers tend to favor greater

participation and decision making in the work place. An egalitar-

ian orientation often comes with a tendency to relate with

ne coe The Way We Work

authority figures less formally. Thus, organizational leaders may

have to adjust their communication style when dealing with the

new generation of workers. More frequent feedback and per-

sonal communication as opposed to signed letters or memos

might be more appropriate for this generation of workers.

An egalitarian orientation likewise implies a desire for mean-

ingful participation and involvement in organizational matters.

This suggests that younger workers will be happier in organiza-

tions that are participative and empowering. To address these

sentiments, managers and supervisors may want to regularly

invite their subordinates to be part of decision making on mat-

ters that affect them. Moreover, participation in decision making

usually creates a shared commitment to the work that follows.

Another option is to hold mentoring sessions where work-

ers can have more personal dialogue with their superiors.

Discussion topics can range from career issues to information

about the business and the company’s plans. Aside from ad-

dressing workers’ need to participate and be involved, mentoring

creates the opportunity for fresh ideas and wisdom from years

of working experience to come together. This convergence be-

comes a potential source of initiatives that could help improve

the organization and its business.

All in all, the study shows that the generations are alike as

much as they are different. The key to managing generations is

to collectively harness similar values as well as employ different

approaches when necessary.

References

Acuiia, J. E, 1998. Is there a Filipino way of achieving productivity?

In Readings in human behavior in organizations, ed. J. E. Acuiia,

R. A. Rodriguez, and N. N. Pilar, 157-65. Mandaluyong, Metro

Manila: Diwa Publishing.

Boyatzis, R. E. and F, R. Skelly. 1995. The impact of changing values

on organizational life. In The organizational behavior reader, ed.

Are there Generational Differences in Work Values? aT

D. A. Kolb, J. S. Osland, and I. M. Rubin, 1-17. 6th ed. New

Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Kabacoff, R. I. and R. W. Stoffey. 2000. Age differences in organiza-

tional leadership (Management Research Group Report). Retrieved

February 28, 2002, from http://www.mrg.com/articles/

Age_and_Leadership.pdf

Montiel, C. J. 1992. Factor analysis of ideological and generational

differences in value orientation among Filipino student activ-

ists. Philippine Journal of Psychology 2.4:12-21.

Pine, G. J. and G. Innis. 1987. Culture and individual work values.

Career Development Quarterly 35:279-87.

Rokeach, M. 1973. The nature of human values. New York: The Free

Press.

Smith, T. W. 2000. Changes in the generation gap, 1972-1998. Uni-

versity of Chicago GSS Social Change Report No. 43. Retrieved

March 7, 2002, from http://www.norc.uchicago.edu/online/

gengap.pdf

Super, D. 1957. The psychology of careers. New York: Harper & Row

Publishers.

‘\/he Stress of Juggling

Work and Family

Ma. Regina M. Hechanova

IFYOU ASK ADULTS WHAT THEIR LIVES revolve around, most would

probably give you two answers: work and family. A great major-

ity (78 percent) of Filipino workers are married. In addition,

‘women’s participation in the workforce has greatly increased in

the past decades. In the 1960s, less than a third of Filipinas

worked. Today, one of two women works. Not surprisingly, there

has been a rise in dual-career couples. Currently, both father

and mother work outside the home in 37 percent of Filipino

families (Hechanova, Uy, and Presbitero; see pp. 3-17, this

vol.). With all these developments, it is understandable that

establishing a balance between work and family is becoming

harder for more Filipinos.

As the country adapts to industrialization and the global

economy, individuals are often faced with new demands, expec-

tations, and roles. Work occupies an increasing portion of people’s

lives such that family and social life often revolves around it.

With the dynamism and instability of many businesses, workers

28

The Stress of Juggling W

today are barraged with many sources of stress in the workplace.

Job loss is a reality that more and more workers face. Major

career transitions due to mergers and acquisitions are another

source of anxiety. Beyond these major changes, certain charac-

teristics in organizations such as work pressure, poor work

climate, office politics, problems with supervisors and peers,

and bureaucracy have been shown to affect occupational health.

Aside from work-related stress, the average adult faces other

forms of stress that emanate from their roles as parent and

spouse. Financial concerns, marital strains, childbearing and preg-

nancy difficulties, difficulty in managing children, conflict among

children, and conflict between parents and children are but some

of the sources of stress in families.

Given that both work and family are potent sources of

stress, this study sought to look at the impact of stress on

working parents who must juggle demands of both work and

family. Specifically, it examined the sources of stress, stress

symptoms, and coping behavior of working parents.

rk_and Family :

The Study

A total of 371 Filipino working parents responded to this

household interview/survey conducted in various locations in

Metro Manila. The average age of respondents was forty-

three and the average number of children was three. Most of

the respondents (58 percent) were women, married (87 per-

cent), and had college degrees (57 percent). Sixty-nine percent

of the respondents belonged to two-income families and the

composition of the sample in terms of high, middle, and low

income was 38 percent, 25 percent, and 37 percent, respec-

tively.

A list of work and nonwork sources of stress was provided

and respondents were asked to check which among the identi-

fied conditions they, their spouse, children, or important family

members experienced in the last six months. Respondents

were also asked to indicate which of the stress symptoms they

experienced within the past six months as a result of the stress

they underwent.

To measure coping behavior, a scale was constructed based

on the F-COPES Scale (Olson et al. 1983). The resulting scale

measured six coping strategies: problem-focused, reframing, seek-

ing spiritual support, seeking social support, passive coping,

and seeking formal support. Items used a Likert scale where

respondents indicated the extent to which they engage in a

particular strategy whenever faced with a stressful situation (4,

all of the time; 3, most of the time; 2, some of the time; 1, not

at all). Internal consistency reliability estimates ranged from

-65 to .75.

Study Results

Sources of Stress of Filipino Working Parents

Working parents report a variety of sources of stress. As seen in

table 1, majority of respondents report work as a predominant

source of stress. The most common work-related sources of

stress are difficulty with boss, increasing time at work and away

from family, demotion, and starting a new business or job. Fi-

nancial concerns include increasing expenses without increase

in income, debt, and major expenditures (car, house, appliances,

education). Family and children are also potent sources of stress.

The most common family-related sources of stress are marriage,

pregnancy, death in the family, sickness, building or moving

residence, children’s school problems, returning to school, marital

problems, and relationship problems with children.