Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Personalized Genetic Risk Counseling To Motivate Diabetes Prevention

Personalized Genetic Risk Counseling To Motivate Diabetes Prevention

Uploaded by

Joban PhulkaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Personalized Genetic Risk Counseling To Motivate Diabetes Prevention

Personalized Genetic Risk Counseling To Motivate Diabetes Prevention

Uploaded by

Joban PhulkaCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Care/Education/Nutrition/Psychosocial Research

O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E

Personalized Genetic Risk Counseling

to Motivate Diabetes Prevention

A randomized trial

RICHARD W. GRANT, MD, MPH1 ROBERT C. GREEN, MD, MPH4,6,7 diabetes (3–5). Despite the relative cost-

KELSEY E. O’BRIEN, BA2 KATHERINE G. STEMBER, BA2 effectiveness of nonpharmacologic ap-

JESSICA L. WAXLER, CGC3 CANDACE GUIDUCCI, BS8 proaches to diabetes prevention (6,7),

JASON L. VASSY, MD, MPH, SM2,4 ELYSE R. PARK, PHD, MPH4,9 efforts to translate the intensive behavioral

LINDA M. DELAHANTY, MS, RD4,5 JOSE C. FLOREZ, MD, PHD4,5,8,10

LAURIE G. BISSETT, MS5 JAMES B. MEIGS, MD, MPH2,4 change interventions of clinical trials into

the community setting have had only mod-

est success (8–11).

OBJECTIVEdTo examine whether diabetes genetic risk testing and counseling can improve

New approaches to conveying per-

diabetes prevention behaviors. sonal risk, such as individualized diabetes

Downloaded from http://diabetesjournals.org/care/article-pdf/36/1/13/613510/13.pdf by guest on 12 March 2023

genetic risk testing, may enable more

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODSdWe conducted a randomized trial of diabetes effective diabetes prevention (12). One

genetic risk counseling among overweight patients at increased phenotypic risk for type 2 di- promise of genome-based “personalized

abetes. Participants were randomly allocated to genetic testing versus no testing. Genetic risk was medicine” has been the potential to moti-

calculated by summing 36 single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with type 2 diabetes. vate individuals to make lifestyle changes

Participants in the top and bottom score quartiles received individual genetic counseling before that ameliorate their disease risk (13,14).

being enrolled with untested control participants in a 12-week, validated, diabetes prevention

program. Middle-risk quartile participants were not studied further. We examined the effect of

Type 2 diabetes is an ideal clinical para-

this genetic counseling intervention on patient self-reported attitudes, program attendance, and digm for testing this assumption given the

weight loss, separately comparing higher-risk and lower-risk result recipients with control high prevalence of an easily identified pre-

participants. disease phenotype, the strong evidence

linking behavior change to risk reduction,

RESULTSdThe 108 participants enrolled in the diabetes prevention program included 42 par- suboptimal translation of proven behav-

ticipants at higher diabetes genetic risk, 32 at lower diabetes genetic risk, and 34 untested control ioral change interventions into clinical

subjects. Mean age was 57.9 6 10.6 years, 61% were men, and average BMI was 34.8 kg/m2, with practice, and recent rapid progress in dia-

no differences among randomization groups. Participants attended 6.8 6 4.3 group sessions and

lost 8.5 6 10.1 pounds, with 33 of 108 (30.6%) losing $5% body weight. There were few

betes genetic epidemiology.

statistically significant differences in self-reported motivation, program attendance, or mean Patients and providers have both in-

weight loss when higher-risk recipients and lower-risk recipients were compared with control dicated that learning about higher genetic

subjects (P . 0.05 for all but one comparison). risk results would likely motivate individ-

uals to change their behavior to prevent

CONCLUSIONSdDiabetes genetic risk counseling with currently available variants does not diabetes (15,16). This prediction has not

significantly alter self-reported motivation or prevention program adherence for overweight yet been convincingly demonstrated in

individuals at risk for diabetes. controlled trials (17). In addition, genetic

Diabetes Care 36:13–19, 2013

testing that reveals a decreased genetic risk

could provide false reassurance to individ-

uals with a high phenotypic risk (18). This

N

early 80 million Americans are cur- 2030 (1,2). Robust clinical trial evidence concern has also not yet been rigorously

rently at increased risk for diabetes, has demonstrated that lifestyle changes examined. Therefore, we conducted a ran-

with worldwide diabetes preva- leading to increased exercise and weight domized, controlled trial to test the hy-

lence projected to reach 440 million by loss can substantially reduce the risk for pothesis that diabetes genetic risk testing

c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c c and counseling can motivate the behavior

changes necessary to prevent diabetes.

From the 1Division of Research, Kaiser Permanente Northern California, Oakland, California; the 2Division of

General Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; the 3Department of Pediatrics, Given the potential for false reassurance

Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; the 4Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massa- with lower-risk results, we separately inves-

chusetts; the 5Diabetes Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; the 6Partners tigated the effect of disclosing increased or

Center for Personalized Genetic Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; the 7Division of Genetics, Brigham and decreased diabetes genetic risk compared

Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; the 8Program in Medical and Population Genetics, Broad In-

stitute, Cambridge, Massachusetts; the 9Mongan Institute for Health Policy, Massachusetts General Hos-

with untested control participants.

pital, Boston, Massachusetts; and the 10Center for Human Genetic Research, Massachusetts General

Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts.

Corresponding author: Richard W. Grant, richard.w.grant@kp.org. RESEARCH DESIGN AND

Received 7 May 2012 and accepted 28 June 2012. METHODS

DOI: 10.2337/dc12-0884. Clinical trial reg. no. NCT01034319, clinicaltrials.gov.

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://care.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10 Study design

.2337/dc12-0884/-/DC1.

© 2013 by the American Diabetes Association. Readers may use this article as long as the work is properly The Genetic Counseling/Lifestyle Change

cited, the use is educational and not for profit, and the work is not altered. See http://creativecommons.org/ for Diabetes Prevention (GC/LC) Study

licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ for details. was a prospective, three-arm parallel

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 36, JANUARY 2013 13

Genetic risk counseling for diabetes prevention

group, randomized, controlled clinical trial San Diego, CA). A summary genetic risk Center who was masked to the genetic

conducted among individuals at increased score was calculated from 36 successfully results. The diabetes prevention groups

phenotypic risk for type 2 diabetes that genotyped risk alleles previously associ- combined intervention and control par-

tested two hypotheses: 1) receiving a higher ated with type 2 diabetes (21). ticipants to eliminate any group-based in-

diabetes genetic risk result would improve tervention effects. Participants were asked

motivation and participation in a 12-session Calculation of relative and absolute to refrain from discussing their genetic

weekly diabetes prevention program diabetes genetic risk testing status and results. Masking was

compared with untested control subjects; Individualized genetic risk assessment well preserved, with the correct predic-

and 2) receiving a lower diabetes genetic was performed by multiplying the relative tion of participant testing status by the

risk result would decrease motivation and genetic risk, as determined using diabetes dietitian after completion of the 12-week

participation compared with untested con- incidence data from the Framingham program no better than chance (33.2%).

trol subjects. This study was investigator- Offspring Study (FOS) (22), by the abso-

initiated, funded by the National Institute lute phenotypic risk of the study popula- Outcome measures

of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Dis- tion. In FOS, 17.9% patients in the top We posited a causal pathway for diabetes

eases, and conducted at Massachusetts quartile of genetic risk score distribution prevention by which changes in patient

General Hospital in Boston. (.38) developed diabetes (46% relative motivation would lead to changes in the

Details of the study design have been increase compared with middle two aver- health-related behaviors that in turn would

published previously (19). Briefly, eligi- age quartiles), whereas 9.9% in the bot- induce the physiologic changes necessary

Downloaded from http://diabetesjournals.org/care/article-pdf/36/1/13/613510/13.pdf by guest on 12 March 2023

ble individuals were randomly allocated tom quartile (scores ,34) developed to prevent diabetes. To capture changes in

using random numbers in concealed diabetes (18% relative decrease compared motivation, we assessed self-reported con-

envelopes in a four-to-one ratio to diabe- with “average” risk). We estimated the ab- fidence and motivation to make diabetes-

tes genetic risk testing versus no testing. solute diabetes incidence for participants related lifestyle changes (exercise, weight

Investigators implemented the random meeting our study eligibility criteria as loss, and adoption of a low-fat diet) and

allocation, enrollment, and assignment. ;11% over 3 years using previously pub- stage of change for achieving these behav-

Participants with top and bottom quartile lished data from within our hospital net- iors (25–27). To assess behavioral changes,

of diabetes genetic risk were enrolled with work (23). Multiplying relative genetic we measured number of sessions attended

untested control subjects into a 12-week risk by this absolute phenotypic-based risk for the 12-week Lifestyle Balance program

group-based Lifestyle Balance diabetes resulted in posttest absolute 3-year risk because prior research has demonstrated

prevention program modeled after the estimates of 17% (higher genetic risk re- a positive dose–response relationship be-

Diabetes Prevention Program protocol cipients), 11% (untested control subjects), tween attendance and diabetes prevention

and previously validated in patients with and 9% (lower genetic risk recipients) for (28). Finally, we also assessed weight change

metabolic syndrome (9). Participants de- type 2 diabetes. from baseline to program completion.

termined to have average diabetes genetic

risk received their results but were not Intervention implementation Statistical analyses

studied further. This study was approved Participants with results showing higher For our primary analyses, we examined

by the Partners Human Research Com- and lower diabetes genetic risk each changes in self-reported responses from

mittee Institutional Review Board. All received a 15-min structured, individual baseline to study end, separately compar-

participants provided written informed genetic counseling session conducted ing higher-risk and lower-risk recipients

consent before enrollment. by a certified genetic counselor. Details with untested control participants. The

of the session have published previously study was designed to have sufficient

Study participants (24). Each participant received a detailed power for assessing 1) the difference be-

Participants were recruited from primary diabetes genetic risk report listing results tween comparison arms from baseline to

care practices within our institution, with for each successfully tested single nucleo- study completion in self-reported stages

the permission of their primary care physi- tide polymorphisms and the individual’s of change, and 2) differences in program

cians, between January 2010 and March overall diabetes genetic risk category attendance. We estimated that with 30 in-

2011. Patients were eligible to participate in (Supplementary Data). The one-on-one tervention participants in each arm and

the study if they were aged 21 years or genetic counseling sessions explained 30 control participants, we had 97% power

older, overweight (defined as BMI $29.1 the genetic test results, discussed the rel- to detect a 90% increase in higher-risk in-

kg/m2 in men, $27.2 kg/m2 in women), ative contributions of genetic versus life- tervention patients versus a 50% increase in

met one other criterion for metabolic syn- style factors to the development of control participants regarding stage of

drome without an existing diagnosis of diabetes, and placed the recipient’s ge- change at 0.05 two-sided significance and

type 2 diabetes (20), and were physically netic risk results within the context of 78% power to show a 21% decrease in mo-

able and willing to participate in a 12-week his or her overall risk for diabetes. A pri- tivation comparing lower-risk intervention

group session program designed to achieve mary goal of the counseling session was to patients with control participants. For at-

weight loss through dietary change and in- use the genetic test result as an opportu- tendance, we estimated that the study sam-

creased physical activity. nity to encourage overall diabetes risk re- ple size would provide 96% power to

Blood samples for individuals random- duction through behavioral changes. detect a 20% difference in number of dia-

ized to genetic testing were drawn for Counseled intervention participants betes prevention sessions attended (i.e., dif-

diabetes genetic risk assessment and and untested control subjects partici- ference of 1.7 visits assuming that control

genotyped at the Broad Institute (Cambridge, pated in a 12-week diabetes prevention participants attended 8.5 of 12 visits).

MA) using the Sequenom MassARRAY program conducted by an experienced For stages of change, we dichotomized

iPLEXGold platform (Sequenom, Inc., dietitian from our institution’s Diabetes the results into percentage of participants

14 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 36, JANUARY 2013 care.diabetesjournals.org

Grant and Associates

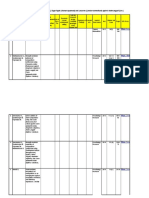

who improved or increased versus all Table 1dBaseline characteristics of the 116 participants by intervention allocation

others. Changes from baseline in 10-point

scales for motivation and confidence were Higher Lower

analyzed as continuous data using t tests Control genetic genetic

and dichotomized data (increase vs. no in- subjects risk risk

crease) using x2 tests. Program attendance n = 38 n = 44 P n = 34 P

was analyzed as a continuous variable

(using t tests and Wilcoxon rank sum to Age (years), mean 6 SD 59.6 6 10.8 56.2 6 8.9 0.12 61.0 6 12.0 0.61

compare means and medians) and also di- Male sex, n (%) 25 (65.8) 25 (56.8) 0.41 19 (55.9) 0.39

chotomized as proportion of participants Race, n (%)

attending at least seven sessions (a thresh- Black 1 (2.6) 3 (6.8) 0.63 0 1.0

old consistent with the Centers for Disease White 32 (84.2) 33 (75.0) 30 (88.2)

Control and Prevention’s attendance crite- Other 5 (13.2) 8 (18.2) 4 (11.8)

ria for diabetes prevention recognition pro- BMI (kg/m2), mean 6 SD 34.7 6 3.6 34.8 6 5.5 0.96 36.1 6 6.2 0.27

grams) (29) as the goal for group-based Annual household income, n (%)

diabetes prevention programs. All analyses ,$50,000 13 (36.1) 12 (27.9) 0.55 12 (37.5) 0.39

were intention-to-treat. $50,000–99,000 9 (25.0) 9 (20.9) 12 (37.5)

In a planned secondary analysis, we .$100,000 14 (38.9) 22 (51.2) 8 (25.0)

Downloaded from http://diabetesjournals.org/care/article-pdf/36/1/13/613510/13.pdf by guest on 12 March 2023

also compared the relative effect and Education, n (%)

durability of the genetic counseling #12th grade or General

intervention between higher- versus Educational Development test 4 (10.5) 8 (18.2) 0.5 12 (35.3) 0.05

lower-risk intervention recipients after 1–3 years of college 13 (34.2) 11 (25.0) 9 (26.5)

completion of the 12-week program. $ 4 years of college 21 (55.3) 25 (56.8) 13 (38.2)

Family history of diabetes, n (%) 19 (50.0) 25 (56.8) 0.54 21 (61.8) 0.32

RESULTS Current health, n (%)

Poor 0 0 0.73 1 (2.9) 0.72

Study participants Fairly poor 4 (10.5) 3 (6.8) 4 (11.8)

We contacted 687 potentially eligible Average 14 (36.8) 16 (36.4) 9 (26.5)

participants by telephone. After exclud- Good 14 (36.8) 14 (31.8) 16 (47.1)

ing ineligible 83 individuals, 177 of 604 Very good 6 (15.8) 11 (25.0) 4 (11.8)

participants (29.3%) consented to partic- Diabetes risk perception

ipate. Study allocation arms were well (% reporting “moderate/high” risk) 73.5 65.6* 0.47 68.8 0.69

balanced (Table 1). All participants Motivation (10-point scale) for

reported high motivation (9.4 on a scale Weight loss 8.0 8.3 0.44 8.1 0.80

of 0–10) to prevent diabetes, although Dietary change 7.8 8.3 0.16 8.1 0.38

motivation and confidence for making Exercise increase 8.2 8.4 0.54 8.0 0.70

specific changes involving weight loss, Diabetes prevention 9.4 9.5 0.84 9.5 0.85

diet, and increasing exercise were lower, Confidence (10-point scale) for

ranging from 6.8 to 8.4. Weight loss 7.0 7.6 0.19 6.8 0.69

Dietary change 7.3 8.0 0.15 7.0 0.58

Changes in self-reported attitudes Exercise increase 7.8 7.9 0.74 7.0 0.13

Enrollment in the 12-week diabetes pre- Diabetes prevention 8.2 8.1 0.86 7.7 0.33

vention program led to small, generally Stage of change

favorable changes in risk perception, mo- (% in action/maintenance)

tivation (with the exception of exercise), Weight loss 12 (35.2) 15 (35.7) 0.97 9 (28.1) 0.53

and confidence that were not statistically Diet 5 (15.2) 10 (23.8)* 0.35 4 (12.5)* 0.76

different comparing higher- or lower-risk Exercise 8 (23.5) 13 (31.0) 0.47 5 (15.6) 0.41

result recipients with control participants P values compare higher-risk recipients vs. control participants and lower-risk recipients vs. control par-

(Table 2). There was some evidence that ticipants. Race, income, education, and family history of diabetes are self-reported. Motivation and confi-

dence questions are based on 10-point Likert scales ranging from 0 (not at all) to 10 (highest motivation/very

lower-risk result recipients had less intent confident). Prochaska stages of change progress from precontemplative to contemplative, preparation, ac-

to exercise, with 37.5% of these partici- tion, and maintenance (25–27). *One missing response.

pants increasing their stage of change for

exercise compared with 64.7% of control

participants (P = 0.03). pounds (P , 0.001) and 33 of 108 partic- of higher-risk results attended 0.4 more ses-

ipants (30.6%) losing $5% body weight. sions (95% CI 21.6 to 2.5; P = 0.67)

Differences in program attendance However, despite clear room for improve- and lost more weight (BMI difference 20.2

and weight loss ment in program attendance and goal kg/m2 [20.5 to 0.9]; P = 0.52) compared

Study participants attended a mean of weight achievement, receipt of personal ge- with control participants. Lower-risk recipi-

6.8 6 4.3 of 12 diabetes prevention group netic risk information and counseling had ents attended 0.3 fewer sessions (21.9 to 2.4;

sessions. The 12-week Lifestyle Change no statistically significant effect on measured P = 0.82) and also lost more weight (BMI

program had a beneficial overall effect, behaviors compared with untested control difference 20.3 kg/m2 [20.5 to 1.1]; P =

with enrollees losing a mean of 8.5 6 10.1 participants (Table 3 and Fig. 1). Recipients 0.48) compared with control participants.

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 36, JANUARY 2013 15

Genetic risk counseling for diabetes prevention

Table 2dChanges from baseline in self-reported measures of risk perception, motivation, to adopt diabetes prevention behaviors or

confidence, and stage of change for diabetes prevention behaviors, comparing recipients significantly increase program atten-

of higher and lower genetic risk results with untested control subjects dance or weight loss compared with un-

tested control patients. Conversely,

Control Higher Lower receiving a lower genetic risk result did

n = 34 n = 42 P n = 32 P not appear to significantly detract from

motivation or attendance.

Increased diabetes risk perception 4 (11.8) 9 (22.0)* 0.25 1 (3.1) 0.18 The GC/LC Study is one of the first

Increased motivation rigorous, controlled trials to directly ad-

Weight loss 17 (50.0) 12 (28.6) 0.056 13 (40.6) 0.44 dress the effect of diabetes genetic risk

Dietary change 15 (44.1) 16 (38.1) 0.60 12 (37.5) 0.58 information on patient behavior. Our

Exercise increase 11 (32.4) 10 (23.8) 0.41 8 (25.0) 0.51 study has several important strengths.

Diabetes prevention 3 (8.8) 7 (16.7) 0.31 5 (15.6) 0.40 We designed our genetic counseling in-

Increased confidence tervention to be intensive yet relatively

Weight loss 18 (52.9) 15 (35.7) 0.13 18 (52.9) 0.21 brief to maximize the translatability to the

Dietary change 16 (47.1) 20 (47.6) 0.96 11 (35.5)* 0.34 real-world clinical setting. Delivered by

Exercise increase 14 (41.2) 17 (40.5) 0.95 11 (34.4) 0.57 an experienced genetic counselor, the

Diabetes prevention 11 (32.4) 17 (40.5) 0.47 13 (41.9)* 0.42 counseling intervention was designed to

Downloaded from http://diabetesjournals.org/care/article-pdf/36/1/13/613510/13.pdf by guest on 12 March 2023

Increased in stage of change educate recipients about the relative con-

Weight loss 20 (58.8) 22 (53.7) 0.65 19 (59.4) 0.96 tributions of both genetic and behavioral

Diet 17 (51.5) 21 (50.0) 0.90 12 (40.0) 0.36 risk and to emphasize that changing their

Exercise 22 (64.7) 19 (45.2) 0.09 12 (37.5) 0.03 behavior could reduce their overall di-

Data are shown as n (%). P values compare higher-risk recipients vs. control participants and lower-risk abetes risk. This approach received pos-

recipients vs. control participants. Number (%) with increased motivation and confidence based on im- itive preliminary feedback by study

provement from baseline in response to 10-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 10 (very confident/

highest motivation). Prochaska stages of change progress from precontemplative to contemplative, preparation,

participants for its effect on perceived

action, and maintenance (25–27). *One missing response. control and general satisfaction with the

genetic counseling process (24). Cru-

cially, all study participants were then en-

rolled in an evidence-based and validated

Secondary analysis of higher- versus participants, P = 0.008). A significant

diabetes prevention program designed to

lower-risk intervention arms proportion of lower-risk result recipi-

provide them with the tools and skills

After completing the 12-week prevention ents reported that they had not thought

necessary to achieve the required behav-

program, 74 intervention participants about their genetic risk results in the

ior changes for diabetes prevention. We

(96% ) recalled their diabetes genetic prior 3 months (43.8% vs. 16.7% of

believe that using the genetic test disclo-

risk status (e.g., “higher” or “lower”), al- higher result recipients, P = 0.02). De-

sure as a “teachable moment” to engage

though only 2 (3%) could accurately re- spite these self-reported differences,

patients in risk-reducing behavior change

call their numeric genetic risk score. In program attendance and weight loss

represents a powerful model for how ge-

an exploratory analysis, we found that were not statistically different when the

netic testing for common chronic diseases

higher-risk result recipients more often two intervention arms were compared

can be implemented into primary care

reported that the initial genetic counseling (P . 0.05).

practice. By coupling information (ge-

intervention had made them “much more/

netic test results and counseling) to a

somewhat more” motivated to participate CONCLUSIONSdAmong overweight

mechanism for participants to act on the

in the 12-week program (78.6% vs. 43.8% primary care patients at increased pheno-

information (diabetes prevention pro-

for lower-risk participants, P = 0.003) typic risk for type 2 diabetes, receiving a

gram), the GC/LC Study created an ideal

and to make lifestyle changes to prevent higher genetic risk result and counseling

context for genetic testing to succeed as a

diabetes (85.7% vs. 56.3% for lower-risk did not significantly improve motivation

motivator.

Our study was also designed to di-

rectly address the potential for false

Table 3dDifferences in program attendance and weight loss, comparing recipients of reassurance from receiving results

higher and lower genetic risk results with untested control subjects showing a lower genetic risk, particularly

among patients with increased risk based

Control Higher Lower on family history or validated phenotypic

n = 34 n = 42 P n = 32 P measures. We did not uncover a strong

negative influence of receiving a “lower”

Classes attended of 12 scheduled risk result, with the possible exception of

Mean 6 SD 6.6 6 4.7 7.0 6 4.0 0.67 6.8 6 4.2 0.82 one exercise measure. From our exit sur-

Median (interquartile range) 9 (1–11) 8 (3–11) 0.84 8 (3.5–10) 0.97 veys, it appears that many lower-risk re-

Attended $7 classes, n (%) 20 (58.8) 26 (61.9) 0.78 20 (62.5) 0.76 cipients underemphasized their genetic

Weigh loss (pounds), mean 6 SD 7.52 6 9.59 8.74 6 9.60 0.58 9.18 6 11.6 0.53 test results. We suspect that most of the

BMI reduction (kg/m2), mean 6 SD 1.02 6 1.45 1.23 6 1.47 0.52 1.30 6 1.80 0.48 genetically tested patients with average

Lost 7% body weight, n (%) 6 (17.7) 10 (23.8) 0.51 6 (18.8) 0.91 results would have had a similar response,

P values compare higher-risk recipients vs. control subjects and lower-risk recipients vs. control subjects. indicating that diabetes genetic risk

16 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 36, JANUARY 2013 care.diabetesjournals.org

Grant and Associates

distribution in which the vast majority

of individuals fall within a relatively nar-

row middle range. In addition, creating

more extreme cut points, such as the top

decile of risk, would have resulted in

higher relative risk differences at the ex-

pense of identifying an increasingly

smaller number of participants, which

would have diminished the clinical rele-

vance of our results.

Focusing as we did on phenotypically

high-risk participants might have limited

the effect of the genetic risk results because

these participants might already have been

maximally motivated. The paradox of this

limitation is that less motivated individuals

are also less likely to be interested in genetic

testing. Given the modest success rate

Downloaded from http://diabetesjournals.org/care/article-pdf/36/1/13/613510/13.pdf by guest on 12 March 2023

among control participants in our study

and among other community-based pro-

grams described in the literature (8–11),

Figure 1dProportion of participants attending each week of the 12-week Diabetes Prevention new tools to achieve enduring behavior

Program. change are clearly needed. One challenge

for the future is to identify the subset of

patients for whom genetic test results rep-

testing and counseling, even if it ulti- focused on unique gene-environment in- resent the tipping point from inaction

mately provides greater predictive power, teractions may help to further tailor inter- to action.

will likely have little benefit but will do ventions (e.g., some patients may benefit Our findings build on an emerging

little harm for most tested patients who preferentially from caloric restriction or literature in translational genomics and

do not have higher results. certain dietary plans, others from aero- health outcomes (33–35) and have im-

Despite these study strengths, several bic exercise or resistance training) (31) plications for current direct-to-consumer

limitations must be considered. Perhaps and therefore lead to truly personalized home genetic testing (36). Such tests may

foremost of these is the limited predictive behavioral treatments. Finally, although benefit self-selected individuals but may

value of current diabetes genetic risk test- we cannot exclude small differences also have negative consequences in

ing, which required us to focus on the in self-reported measures that did not patient-borne costs and the potential for

highest-risk patients to maximize the re- reach statistical significance, we have triggering expensive diagnostic cascades

sulting contrast between tested and un- good confidence that any difference in (37). Without further evidence of efficacy

tested participants. Even in this group, with self-reported measures did not translate from controlled clinical trials, such testing

an estimated 3-year risk for diabetes of into significant changes in attendance cannot yet be recommended in routine

11%, the recalculated risk based on relative behavior. clinical care for diabetes prevention. Other

genetic risk results resulted in only modest Our results must be considered important applications of personalized ge-

changes. Thus, we do not know whether within the context of the study design. netic testing deserve further study, includ-

greater genetic predictive ability in the We randomized in two stages to provide a ing clinically applied pharmacogenomic

future will have a bigger impact on chang- clinically relevant test of genetic testing profiling (38) and evaluation of phenotyp-

ing behavior. However, given that 96% of versus no testing on preventive behavior, ically lower-risk younger patients who

our intervention patients remembered their while also efficiently focusing on the have yet to manifest diabetes-related phe-

qualitative genetic risk (i.e., “higher” or genetic risk extremes among tested par- notypic traits.

“lower”) but not their quantitative risk ticipants. For the second-stage allocation In summary, a diabetes genetic risk

score (provided as a hand-out during the of intervention participants, we relied on assessment and counseling intervention

counseling session), we suspect that mar- the concept of Mendelian randomization for overweight individuals based on 36

ginal improvements in risk prediction will (e.g., the random allocation of parental single nucleotide polymorphisms neither

not lead to substantially greater impact on alleles during gametogenesis) to identify improved nor substantially detracted

patient behavior. top and bottom quartiles of genetic risk from an evidence-based behavioral inter-

Another limitation of current genetic score distribution (32). A strategy of using vention to prevent diabetes.

knowledge is that results do not alter the the lowest quartile of score as “normal”

actual behavioral intervention; thus, al- would have increased the effect size in

though the risk information is personal- the highest quartile and would have elim- AcknowledgmentsdThis study received

ized, the intervention itself is not. The inated the problem of presenting “lower” funding support from National Institute of

Diabetes Prevention Program recently genetic risk results to otherwise pheno- Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

showed that an intensive lifestyle inter- typically high-risk individuals. However, Grants R21-DK84527 and K24-DK080140.

vention benefits participants regardless of it seemed unethical to portray low-score No potential conflicts of interest relevant to

overall genetic risk (30), but future research outliers as normal given the population this article were reported.

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 36, JANUARY 2013 17

Genetic risk counseling for diabetes prevention

R.W.G. obtained funding, oversaw the clini- community. The DEPLOY pilot study. Am 21. de Miguel-Yanes JM, Shrader P, Pencina

cal trial, researched data, and wrote the manu- J Prev Med 2008;35:357–363 MJ, et al.; MAGIC Investigators; DIAGRAM

script. K.E.O., J.L.W., and K.G.S. contributed 9. Seidel MC, Powell RO, Zgibor JC, Siminerio + Investigators. Genetic risk reclassification

to the conduct of the clinical trial, researched LM, Piatt GA. Translating the Diabetes Pre- for type 2 diabetes by age below or above 50

data, and reviewed and edited the manu- vention Program into an urban medically years using 40 type 2 diabetes risk single

script. J.L.V. researched data and reviewed underserved community: a nonrandomized nucleotide polymorphisms. Diabetes Care

and edited the manuscript. L.M.D., L.G.B., prospective intervention study. Diabetes 2011;34:121–125

R.C.G., C.G., E.R.P., J.C.F., and J.B.M. con- Care 2008;31:684–689 22. Meigs JB, Shrader P, Sullivan LM, et al.

tributed to the conduct of the clinical trial and 10. Absetz P, Oldenburg B, Hankonen N, Genotype score in addition to common

reviewed and edited the manuscript. R.W.G. is et al. Type 2 diabetes prevention in the risk factors for prediction of type 2 di-

the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full real world: three-year results of the GOAL abetes. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2208–

access to all the data in the study and takes Lifestyle Implementation Trial. Diabetes 2219

responsibility for the integrity of the data and Care 2009;32:1418–1420 23. Hivert MF, Grant RW, Shrader P, Meigs

the accuracy of the data analysis. 11. Kramer MK, Kriska AM, Venditti EM, et al. JB. Identifying primary care patients at

The results of this study, titled “Can Genetic Translating the Diabetes Prevention Pro- risk for future diabetes and cardiovascular

Testing Motivate Behavior Change and Weight gram: a comprehensive model for pre- disease using electronic health records.

Loss?” were presented at the “New Frontiers in vention training and program delivery. Am BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:170

Weight Management” symposium at the 72nd J Prev Med 2009;37:505–511 24. Waxler JL, O’Brien KE, Delahanty LM,

Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes 12. McBride CM, Bowen D, Brody LC, et al. et al. Genetic counseling as a tool for type

Downloaded from http://diabetesjournals.org/care/article-pdf/36/1/13/613510/13.pdf by guest on 12 March 2023

Association, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 8–12 Future health applications of genomics: 2 diabetes prevention: a new genetic

June 2012. priorities for communication, behavioral, counseling framework for common poly-

The authors acknowledge the Diabetes and social sciences research. Am J Prev genetic disorders. J Genet Couns 2012

Prevention Support Center of the University of Med 2010;38:556–565 Feb 3 [Epub ahead of print]

Pittsburgh for providing the written materials 13. Hamburg MA, Collins FS. The path to 25. Greene GW, Rossi SR, Reed GR, Willey C,

for the Group Lifestyle Balance program. personalized medicine. N Engl J Med Prochaska JO. Stages of change for re-

2010;363:301–304 ducing dietary fat to 30% of energy or less.

14. McBride CM, Koehly LM, Sanderson SC, J Am Diet Assoc 1994;94:1105–1110;

References Kaphingst KA. The behavioral response to quiz 1111–1112

1. Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin personalized genetic information: will 26. Marcus BH, Selby VC, Niaura RS, Rossi JS.

LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among genetic risk profiles motivate individuals Self-efficacy and the stages of exercise

US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA 2010;303: and families to choose more healthful behavior change. Res Q Exerc Sport 1992;

235–241 behaviors? Annu Rev Public Health 2010; 63:60–66

2. Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. 31:89–103 27. O’Connell D, Velicer WF. A decisional

Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for 15. Grant RW, Hivert M, Pandiscio JC, Florez balance measure and the stages of change

the year 2000 and projections for 2030. JC, Nathan DM, Meigs JB. The clinical model for weight loss. Int J Addict 1988;

Diabetes Care 2004;27:1047–1053 application of genetic testing in type 2 23:729–750

3. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, diabetes: a patient and physician survey. 28. Lindström J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen

et al.; Diabetes Prevention Program Re- Diabetologia 2009;52:2299–2305 M, et al.; Finnish Diabetes Prevention

search Group. Reduction in the incidence 16. Markowitz SM, Park ER, Delahanty LM, Study Group. Sustained reduction in the

of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention O’Brien KE, Grant RW. Perceived impact incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle

or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346: of diabetes genetic risk testing among intervention: follow-up of the Finnish

393–403 patients at high phenotypic risk for type Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet 2006;

4. Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG, 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34:568– 368:1673–1679

et al.; Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study 573 29. Williamson DF, Marrero DG. Scaling up

Group. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mel- 17. Marteau TM, French DP, Griffin SJ, et al. type 2 diabetes prevention programs

litus by changes in lifestyle among subjects Effects of communicating DNA-based dis- for high risk persons: progress and

with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J ease risk estimates on risk-reducing be- challenges in the United States. In Di-

Med 2001;344:1343–1350 haviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev abetes Prevention in Practice. Schwarz P,

5. Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, et al. Effects of 2010:CD007275 Reddy P, Greaves C, Dunbar JA, Schwarz

diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in 18. Evans JP, Meslin EM, Marteau TM, J, Eds. Dresden, TUMAINI Institute for

people with impaired glucose tolerance. Caulfield T. Genomics. Deflating the ge- Prevention Management, 2010, p. 69–

The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. nomic bubble. Science 2011;331:861– 82

Diabetes Care 1997;20:537–544 862 30. Hivert MF, Jablonski KA, Perreault L,

6. Jacobs-van der Bruggen MA, van Baal PH, 19. Grant RW, Meigs JB, Florez JC, et al. et al.; DIAGRAM Consortium; Diabetes

Hoogenveen RT, et al. Cost-effectiveness Design of a randomized trial of diabetes Prevention Program Research Group.

of lifestyle modification in diabetic genetic risk testing to motivate behav- Updated genetic score based on 34 con-

patients. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1453– ior change: the Genetic Counseling/ firmed type 2 diabetes loci is associated

1458 Lifestyle Change (GC/LC) Study for Di- with diabetes incidence and regression

7. Herman WH, Hoerger TJ, Brandle M, et al.; abetes Prevention. Clin Trials 2011;8: to normoglycemia in the Diabetes Pre-

Diabetes Prevention Program Research 609–615 vention Program. Diabetes 2011;60:

Group. The cost-effectiveness of lifestyle 20. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al.; 1340–1348

modification or metformin in preventing American Heart Association; National 31. Rosado EL, Bressan J, Martins MF, Cecon

type 2 diabetes in adults with impaired Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Di- PR, Martínez JA. Polymorphism in the

glucose tolerance. Ann Intern Med 2005; agnosis and management of the metabolic PPARgamma2 and beta2-adrenergic genes

142:323–332 syndrome: an American Heart Associa- and diet lipid effects on body composi-

8. Ackermann RT, Finch EA, Brizendine E, tion/National Heart, Lung, and Blood In- tion, energy expenditure and eating be-

Zhou H, Marrero DG. Translating the stitute Scientific Statement. Circulation havior of obese women. Appetite 2007;

diabetes prevention program into the 2005;112:2735–2752 49:635–643

18 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 36, JANUARY 2013 care.diabetesjournals.org

Grant and Associates

32. Thanassoulis G, O’Donnell CJ. Mendelian genotype for risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N to assess disease risk. N Engl J Med 2011;

randomization: nature’s randomized trial Engl J Med 2009;361:245–254 364:524–534

in the post-genome era. JAMA 2009;301: 35. Scheuner MT, Sieverding P, Shekelle PG. 37. Verrilli DW, Welch HG. The impact of

2386–2388 Delivery of genomic medicine for common diagnostic testing on therapeutic inter-

33. Collins F. Has the revolution arrived? chronic adult diseases: a systematic review. ventions. JAMA 1996;275:1189–1191

Nature 2010;464:674–675 JAMA 2008;299:1320–1334 38. Wang L, McLeod HL, Weinshilboum RM.

34. Green RC, Roberts JS, Cupples LA, et al.; 36. Bloss CS, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Effect Genomics and drug response. N Engl J

REVEAL Study Group. Disclosure of APOE of direct-to-consumer genomewide profiling Med 2011;364:1144–1153

Downloaded from http://diabetesjournals.org/care/article-pdf/36/1/13/613510/13.pdf by guest on 12 March 2023

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 36, JANUARY 2013 19

You might also like

- WARR, Mark. Fear of Crime in The United States. Avenues For Research and Policy PDFDocument39 pagesWARR, Mark. Fear of Crime in The United States. Avenues For Research and Policy PDFCarol ColombaroliNo ratings yet

- Handwriting Without TearsDocument63 pagesHandwriting Without TearsEllen Aquino100% (8)

- Topics in Type 2 Diabetes and Insulin Resistance: Achary Loomgarden MDDocument7 pagesTopics in Type 2 Diabetes and Insulin Resistance: Achary Loomgarden MDShivpartap SinghNo ratings yet

- By Guest On 26 April 2018Document8 pagesBy Guest On 26 April 2018silvanaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Diet and Exercise in Preventing NIDDM in People With Impaired Glucose ToleranceDocument8 pagesEffects of Diet and Exercise in Preventing NIDDM in People With Impaired Glucose ToleranceAzielNo ratings yet

- 10.1038@s41598 017 10775 3 PDFDocument8 pages10.1038@s41598 017 10775 3 PDFAlyssa LeuenbergerNo ratings yet

- Applying The Health Belief Model in Identifying Individual Understanding Towards Prevention of Type 2 DiabetesDocument6 pagesApplying The Health Belief Model in Identifying Individual Understanding Towards Prevention of Type 2 DiabetesIJPHSNo ratings yet

- Vitamin D Supplementation and Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes: Original ArticleDocument11 pagesVitamin D Supplementation and Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes: Original ArticleChristine BelindaNo ratings yet

- Pone 0052963Document7 pagesPone 0052963SelyfebNo ratings yet

- Dibetes Risk Score - Findrisc - Jaana Lindstrom - ArticleDocument7 pagesDibetes Risk Score - Findrisc - Jaana Lindstrom - ArticleShayekh M ArifNo ratings yet

- Preventing Chronic DiseaseDocument11 pagesPreventing Chronic DiseaseGuillermos RiveraNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Obesity and Diabetes in Pregnancy: Is It An Impossible Dream?Document9 pagesPrevention of Obesity and Diabetes in Pregnancy: Is It An Impossible Dream?Anonymous P5efHbeNo ratings yet

- In The Clinic 2010Document16 pagesIn The Clinic 2010Alex GomezNo ratings yet

- Artikel Nutrigenetik 23043Document10 pagesArtikel Nutrigenetik 23043mutiara fajriatiNo ratings yet

- DM Type 2Document8 pagesDM Type 2dana putraNo ratings yet

- Cky 098Document8 pagesCky 098Thiago SartiNo ratings yet

- ECV y Genetica RiesgoDocument9 pagesECV y Genetica RiesgoLic. Monica Bamonde NutricionistaNo ratings yet

- Nutrigenetics-Personalized Nutrition in The Genetic Age: Review ArticleDocument8 pagesNutrigenetics-Personalized Nutrition in The Genetic Age: Review Articleravenwatch1No ratings yet

- Treatments For Gestational Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument14 pagesTreatments For Gestational Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisSofía Simpértigue CubillosNo ratings yet

- Breakfast Skipping and CADDocument5 pagesBreakfast Skipping and CADadip royNo ratings yet

- Breakfast Frequency and Development of Metabolic RiskDocument7 pagesBreakfast Frequency and Development of Metabolic Riskpriyanka sharmaNo ratings yet

- BMJ I1102 FullDocument11 pagesBMJ I1102 FullTalitha NandhikaNo ratings yet

- Risks of Specific Congenital Anomalies in Offspring of Women With Diabetes - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Studies Including Over 80 Million Births - PLOS MedicineDocument16 pagesRisks of Specific Congenital Anomalies in Offspring of Women With Diabetes - A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Population-Based Studies Including Over 80 Million Births - PLOS MedicinedmidananNo ratings yet

- Spruijt Metz2014Document10 pagesSpruijt Metz2014indah puspitaNo ratings yet

- Comparative Effectiveness of SGLT2 Inhibitors, GLP-1 Receptor Agonists, DPP-4 Inhibitors, and Sulfonylureas On Risk of Kidney Outcomes Emulation of A Target Trial Using Health Care DatabasesDocument11 pagesComparative Effectiveness of SGLT2 Inhibitors, GLP-1 Receptor Agonists, DPP-4 Inhibitors, and Sulfonylureas On Risk of Kidney Outcomes Emulation of A Target Trial Using Health Care DatabasesW Antonio Rivera MartínezNo ratings yet

- Effects of Diet and Exercise in Preventing NIDDM in People With Impaired Glucose ToleranceDocument8 pagesEffects of Diet and Exercise in Preventing NIDDM in People With Impaired Glucose ToleranceOzan OcakNo ratings yet

- From Nutrigenomics To Personalizing Diets: Are We Ready For Precision Medicine?Document2 pagesFrom Nutrigenomics To Personalizing Diets: Are We Ready For Precision Medicine?joeNo ratings yet

- From Genetic Risk Assessment To Diabetes Clinical InterventionDocument2 pagesFrom Genetic Risk Assessment To Diabetes Clinical InterventionBoo omNo ratings yet

- SJ Ijo 0800495Document23 pagesSJ Ijo 0800495Mohammad shaabanNo ratings yet

- Llewellyn 2015Document12 pagesLlewellyn 2015PriscaArfinesKoesnoNo ratings yet

- 2018 A Global Overview of Precision Medicine in Type 2 DiabetesDocument12 pages2018 A Global Overview of Precision Medicine in Type 2 Diabetesguanyulin01No ratings yet

- Siegel 2018Document8 pagesSiegel 2018indah puspitaNo ratings yet

- Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and GynaecologyDocument13 pagesBest Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecologymauricio espinelNo ratings yet

- BMJ k2396 FullDocument6 pagesBMJ k2396 FullKatNo ratings yet

- Differentiation of Diabetes by Pathophysiology, Natural History, and Prognosis PDFDocument15 pagesDifferentiation of Diabetes by Pathophysiology, Natural History, and Prognosis PDFHadi PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Obesity JamaDocument16 pagesObesity JamaSrinivas PingaliNo ratings yet

- Journal Appraisa 3Document11 pagesJournal Appraisa 3Norjetalexis Maningo CabreraNo ratings yet

- PA and CM Risk Factor Young AdultDocument14 pagesPA and CM Risk Factor Young AdultMumtaz MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Aisyah GDM ArticleDocument18 pagesAisyah GDM ArticleBesari Md DaudNo ratings yet

- Dysglycemia and A History of Reproductive Risk Factors: S D. M D, S Y, P S, S S. A, H C. G, Dream T IDocument4 pagesDysglycemia and A History of Reproductive Risk Factors: S D. M D, S Y, P S, S S. A, H C. G, Dream T IKevin WewengkangNo ratings yet

- Tsuyuki 2002Document7 pagesTsuyuki 2002Basilharbi HammadNo ratings yet

- 1999-The Diabetes Prevention Program- Design and methods for a clinical trial in the prevention of type 2 diabetesDocument23 pages1999-The Diabetes Prevention Program- Design and methods for a clinical trial in the prevention of type 2 diabetesluizfernandosellaNo ratings yet

- Sand 2019Document9 pagesSand 2019isragelNo ratings yet

- Chung2020 Article PrecisionMedicineInDiabetesACoDocument23 pagesChung2020 Article PrecisionMedicineInDiabetesACoFilipa Figueiredo100% (1)

- Articles: BackgroundDocument9 pagesArticles: Backgroundjoe tibayNo ratings yet

- Gestational Diabetes - On Broadening The DiagnosisDocument2 pagesGestational Diabetes - On Broadening The DiagnosisWillians ReyesNo ratings yet

- Format PengkajianDocument8 pagesFormat PengkajianHandiniNo ratings yet

- Jaliliana Et Al, 2019Document6 pagesJaliliana Et Al, 2019larissa matosNo ratings yet

- Davenport 2018Document12 pagesDavenport 2018Marcos AlvesNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2475299123260862 MainDocument1 page1 s2.0 S2475299123260862 MainYULISSA FLORES RONDONNo ratings yet

- Disclosing Genetic Risk For Coronary Heart Disease: Effects On Perceived Personal Control and Genetic Counseling SatisfactionDocument7 pagesDisclosing Genetic Risk For Coronary Heart Disease: Effects On Perceived Personal Control and Genetic Counseling SatisfactionJoban PhulkaNo ratings yet

- Precision Medicine of Obesity As An Integral Part of Type 2 Diabetes Management - Past, Present, and FutureDocument18 pagesPrecision Medicine of Obesity As An Integral Part of Type 2 Diabetes Management - Past, Present, and FutureAlexandra IstrateNo ratings yet

- Gestational Diabetes Literature ReviewDocument12 pagesGestational Diabetes Literature Reviewc5rfkq8n100% (1)

- 11 Emerging Technology in Medicine PDFDocument8 pages11 Emerging Technology in Medicine PDFArj NaingueNo ratings yet

- Nejmoa SEMAGLUTIDEDocument13 pagesNejmoa SEMAGLUTIDEraymundo lopez silvaNo ratings yet

- E001680 FullDocument9 pagesE001680 FullHem BhattNo ratings yet

- Mind Diet TrialDocument10 pagesMind Diet TrialAhmed Imran KhanNo ratings yet

- FARLAND 2021 A Prospective Study of Endometriosis and Risk of Type 2 DiabetesDocument9 pagesFARLAND 2021 A Prospective Study of Endometriosis and Risk of Type 2 DiabetesCristiane HermesNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Referat 2Document7 pagesJurnal Referat 2nunki aprillitaNo ratings yet

- DM 2Document8 pagesDM 2Roberto AlexiNo ratings yet

- Eating Disorders in Boys and MenFrom EverandEating Disorders in Boys and MenJason M. NagataNo ratings yet

- Prediabetes: A Fundamental Text: Pathophysiology, Complications, Management & ReversalFrom EverandPrediabetes: A Fundamental Text: Pathophysiology, Complications, Management & ReversalNo ratings yet

- Automatic Aquarium Fish FeederDocument41 pagesAutomatic Aquarium Fish FeedergovjeffNo ratings yet

- Print Ko BukasDocument3 pagesPrint Ko BukasKatrina CaveNo ratings yet

- Cleaning and Sanitizing in The Milk Processing Industry 2010Document28 pagesCleaning and Sanitizing in The Milk Processing Industry 2010John WaweruNo ratings yet

- BP and The Deepwater Horizon DisasterDocument5 pagesBP and The Deepwater Horizon DisasterjacobNo ratings yet

- MTS For Mechanical (Tanks) Premixing - Rev001Document6 pagesMTS For Mechanical (Tanks) Premixing - Rev001Jona Marie FormelozaNo ratings yet

- Hbo Chapter 4Document13 pagesHbo Chapter 4132345usdfghjNo ratings yet

- Civil Engineering Material Lecture NotesDocument4 pagesCivil Engineering Material Lecture Notes11520035No ratings yet

- LIT Equipment - Catalogue A4 en VLRDocument56 pagesLIT Equipment - Catalogue A4 en VLREkaluck JongprasithpornNo ratings yet

- Serie-6-Ttv Brochure enDocument16 pagesSerie-6-Ttv Brochure envaneaNo ratings yet

- Fire Safety Management AND Fire Emergency PlanDocument25 pagesFire Safety Management AND Fire Emergency Plankenoly123100% (5)

- Rossignol Racefolder 2016/17Document12 pagesRossignol Racefolder 2016/17Hermann Knabl100% (1)

- Figure 03 - CV - Sea Staff Application FormDocument6 pagesFigure 03 - CV - Sea Staff Application FormManoj PatilNo ratings yet

- 8 Nasopharyngeal AngiofibromaDocument51 pages8 Nasopharyngeal AngiofibromaAbhishek ShahNo ratings yet

- RRLDocument5 pagesRRLAyen Alecksandra CadaNo ratings yet

- Co-Trimoxazole Drug StudyDocument1 pageCo-Trimoxazole Drug Studyjonelo123100% (1)

- 10 PROWAG Proposed Accessibility GuidelinesDocument114 pages10 PROWAG Proposed Accessibility Guidelinesvmi_dudeNo ratings yet

- Manufacturing Process Lab 01 DoneDocument4 pagesManufacturing Process Lab 01 DoneRk RanaNo ratings yet

- Product Catalogue: BD Diagnostics - Preanalytical SystemsDocument44 pagesProduct Catalogue: BD Diagnostics - Preanalytical SystemsajibagNo ratings yet

- Approval Document ASSET DOC LOC 537Document4 pagesApproval Document ASSET DOC LOC 537aNo ratings yet

- United Arab EmiratesDocument44 pagesUnited Arab EmiratesReymund Dela Cruz CabaisNo ratings yet

- My Courses: Eastern GripDocument6 pagesMy Courses: Eastern GripNiño Jose A. Flores (Onin)100% (1)

- Awwa C 200 Specifications: " Steel Water Pipe - 6 Diameter and More "Document1 pageAwwa C 200 Specifications: " Steel Water Pipe - 6 Diameter and More "joseNo ratings yet

- Account Summary: Krystle Broom Account Name Account Number 721132604 Phone Number Multiple ServicesDocument3 pagesAccount Summary: Krystle Broom Account Name Account Number 721132604 Phone Number Multiple ServicesKrystle FenterNo ratings yet

- Datasheets For LuminairesDocument5 pagesDatasheets For Luminairesronniee287No ratings yet

- How To Make Kimchi at HomeDocument1 pageHow To Make Kimchi at Homenmmng2011No ratings yet

- Neurology SlidesDocument38 pagesNeurology Slidesdrmalsharrakhi_32794100% (1)

- 01-04-2023 - Incoming Sr.C-120 - JEE MAIN - UNIT TEST-01 - Question PaperDocument13 pages01-04-2023 - Incoming Sr.C-120 - JEE MAIN - UNIT TEST-01 - Question PaperMurari Marupu100% (1)

- StockSummaryReport 29-02-24Document31 pagesStockSummaryReport 29-02-24meerut.saverabooksNo ratings yet