Professional Documents

Culture Documents

No Bodys Perfect Renee Green Satch Hoyt

No Bodys Perfect Renee Green Satch Hoyt

Uploaded by

Aarón ReyesCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Mediated: How the Media Shapes Your World and the Way You Live in ItFrom EverandMediated: How the Media Shapes Your World and the Way You Live in ItRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (55)

- (De) Cypher: Black Notes On Culture & C R I T I C I S M (Spring 2022)Document63 pages(De) Cypher: Black Notes On Culture & C R I T I C I S M (Spring 2022)decypher blackNo ratings yet

- The Nude - A New Perspective, Gill Saunders PDFDocument148 pagesThe Nude - A New Perspective, Gill Saunders PDFRenata Lima100% (7)

- Fred Moten Blackness and NothingnessDocument22 pagesFred Moten Blackness and NothingnessRaphaelNo ratings yet

- Woman As Temptress The Way To (BR) Otherhood in Feminist DystopiasDocument12 pagesWoman As Temptress The Way To (BR) Otherhood in Feminist DystopiasDerouiche MariemNo ratings yet

- "Jewels Brought From Bondage": Black Music and The Politics of AuthenticityDocument20 pages"Jewels Brought From Bondage": Black Music and The Politics of AuthenticityJess and MariaNo ratings yet

- Gender Portrayals in Classical Greek Statuary - Melissa Huang - Musings On Art and GenderDocument8 pagesGender Portrayals in Classical Greek Statuary - Melissa Huang - Musings On Art and GenderMerlinNo ratings yet

- Myerhoff B Life History Among The ElderlyDocument10 pagesMyerhoff B Life History Among The ElderlyRodrigo MurguíaNo ratings yet

- Bell Hooks - The Oppositional GazeDocument11 pagesBell Hooks - The Oppositional GazeMARINA PEREIRA100% (1)

- Hall Culture, Comunity, NationDocument8 pagesHall Culture, Comunity, NationHerrSergio SergioNo ratings yet

- Bending and Torqueing Into A "Willful Subject"Document4 pagesBending and Torqueing Into A "Willful Subject"Hayv KahramanNo ratings yet

- Fernard Deligny - The Arachnean and Other Texts PDFDocument245 pagesFernard Deligny - The Arachnean and Other Texts PDFlucasNo ratings yet

- No White Picket Fence: A Verbatim Play about Young Women’s Resilience through Foster CareFrom EverandNo White Picket Fence: A Verbatim Play about Young Women’s Resilience through Foster CareNo ratings yet

- 9853 1287 01d Overhaul Instructions DHR6 H Ver. B PDFDocument68 pages9853 1287 01d Overhaul Instructions DHR6 H Ver. B PDFMiguel CastroNo ratings yet

- Thomas F. DeFrantz, Anita Gonzalez - Black Performance Theory-Duke University Press (2014)Document292 pagesThomas F. DeFrantz, Anita Gonzalez - Black Performance Theory-Duke University Press (2014)Bruno De Orleans Bragança ReisNo ratings yet

- Black Performance Theory Edited by Thomas F. DeFrantz and Anita GonzalezDocument26 pagesBlack Performance Theory Edited by Thomas F. DeFrantz and Anita GonzalezDuke University Press100% (4)

- DEFRANTZ-GONZALEZ - Black Performance Thoery (Intro)Document26 pagesDEFRANTZ-GONZALEZ - Black Performance Thoery (Intro)IvaaliveNo ratings yet

- From Day Fred MotenDocument16 pagesFrom Day Fred MotenAriana ShapiroNo ratings yet

- Howard Barker InterviewDocument4 pagesHoward Barker InterviewMike PugsleyNo ratings yet

- WARK, Mckenzie. The Cis Gaze and It's OthersDocument15 pagesWARK, Mckenzie. The Cis Gaze and It's OthersBruno De Orleans Bragança ReisNo ratings yet

- Reflections On Echo-Sound by Women Artists in Britain Jean FisherDocument7 pagesReflections On Echo-Sound by Women Artists in Britain Jean FisherNicole HewittNo ratings yet

- Incorporeal BlacknessDocument38 pagesIncorporeal BlacknessMíša SteklNo ratings yet

- Fred Moten - Black-OpDocument5 pagesFred Moten - Black-OpNorman AjariNo ratings yet

- 10 - The Gendered Subject TaraDocument31 pages10 - The Gendered Subject TaraPremNo ratings yet

- Paris Is Burning - Bell HookDocument8 pagesParis Is Burning - Bell Hookgasparinflor100% (1)

- Morehshin AllahyariDocument3 pagesMorehshin AllahyariIkram Rhy NNo ratings yet

- Deiure-Vcdb-1 FeedbackDocument3 pagesDeiure-Vcdb-1 Feedbackapi-711324507No ratings yet

- Conflicting Identities in The Euripidean Chorus: Laura SwiftDocument25 pagesConflicting Identities in The Euripidean Chorus: Laura SwiftLuka RomanovNo ratings yet

- Moten in The Break I Resistance of The ObjectDocument25 pagesMoten in The Break I Resistance of The ObjectDaniel Aguirre Oteiza100% (1)

- Understanding Blackness through Performance: Contemporary Arts and the Representation of IdentityFrom EverandUnderstanding Blackness through Performance: Contemporary Arts and the Representation of IdentityNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 213.55.95.215 On Mon, 05 Dec 2022 11:10:38 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 213.55.95.215 On Mon, 05 Dec 2022 11:10:38 UTCAmsalu GetachewNo ratings yet

- The Sadien Sphinx and The Riddle of Black Female IdentityDocument9 pagesThe Sadien Sphinx and The Riddle of Black Female Identityapi-317483746No ratings yet

- Tormented Torsos, The Pornographic Imagination, and Articulated Minors: The Works of Hans Bellmer and Cindy ShermanDocument15 pagesTormented Torsos, The Pornographic Imagination, and Articulated Minors: The Works of Hans Bellmer and Cindy Shermanjeff tehNo ratings yet

- Jared Sexton, "All Black Everything"Document10 pagesJared Sexton, "All Black Everything"Christoph CoxNo ratings yet

- Minor Vices - Observing DisdainDocument8 pagesMinor Vices - Observing DisdainstavrianakisNo ratings yet

- Interview - Jared SextonDocument16 pagesInterview - Jared SextonBen CrossanNo ratings yet

- The Green Studies Reader From Romanticism To Ecocriticism (Laurence Coupe) (Z-Library) (1) - 158-162Document5 pagesThe Green Studies Reader From Romanticism To Ecocriticism (Laurence Coupe) (Z-Library) (1) - 158-162beatrice ciucchiNo ratings yet

- Epistemology and Simulacra in Tarkovsky's SolarisDocument32 pagesEpistemology and Simulacra in Tarkovsky's SolarisAnshuman FotedarNo ratings yet

- Maroon Choreography by Fahima IfeDocument145 pagesMaroon Choreography by Fahima Ifemlaure445No ratings yet

- Drama Notes 2020Document7 pagesDrama Notes 2020TiaNo ratings yet

- Mac Interviews WhitleyDocument5 pagesMac Interviews Whitleymikeclelland100% (2)

- 777320Document9 pages777320Cal DeaNo ratings yet

- After Blackness, Then BlacknesDocument19 pagesAfter Blackness, Then BlacknesNicholas BradyNo ratings yet

- RICHARD DE UTSCH ReviewDocument1 pageRICHARD DE UTSCH ReviewΚλήμης ΠλεξίδαςNo ratings yet

- Selling Hot Pussy - Representations of Black Female Sexuality in The Cultural Marketplace. Bell Hooks PDFDocument13 pagesSelling Hot Pussy - Representations of Black Female Sexuality in The Cultural Marketplace. Bell Hooks PDFGiovanna BoscoNo ratings yet

- Marie Thompson - Feminised Noise and The Dotted Line' of Sonic ExperimentalismDocument18 pagesMarie Thompson - Feminised Noise and The Dotted Line' of Sonic ExperimentalismLucas SantosNo ratings yet

- William S. Haney II - Postmodern Theater & The Void of Conceptions-Cambridge Scholars Publishing (2006) PDFDocument169 pagesWilliam S. Haney II - Postmodern Theater & The Void of Conceptions-Cambridge Scholars Publishing (2006) PDF-No ratings yet

- Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man and Female StereotypesDocument4 pagesRalph Ellison's Invisible Man and Female StereotypesanachronousNo ratings yet

- When A Woman Is Nude: A Critical Visual Analysis of "Harlem" PhotographDocument5 pagesWhen A Woman Is Nude: A Critical Visual Analysis of "Harlem" PhotographFady SamyNo ratings yet

- Afrofuturism and Post-Soul Possibility in Black Popular MusicDocument14 pagesAfrofuturism and Post-Soul Possibility in Black Popular Musicmafefil18No ratings yet

- Let's Conjure Some GhostsDocument12 pagesLet's Conjure Some GhostsIanNo ratings yet

- Core Program Critic-In-Residence (Glassell School of Art / Museum of Fine Arts, Houston)Document23 pagesCore Program Critic-In-Residence (Glassell School of Art / Museum of Fine Arts, Houston)AndyNo ratings yet

- Cinema From Within InterrogatiDocument110 pagesCinema From Within InterrogatiAkhona NkumaneNo ratings yet

- Chasing Rainbows - Black Cracker and Queer, Trans AfrofuturityDocument11 pagesChasing Rainbows - Black Cracker and Queer, Trans AfrofuturitymilaNo ratings yet

- The Acteon Complex: Gaze, Body, and Rites of Passage in Hedda Gabler'Document22 pagesThe Acteon Complex: Gaze, Body, and Rites of Passage in Hedda Gabler'ipekNo ratings yet

- (Perverse Modernities) Christina Sharpe - Monstrous Intimacies - Making Post-Slavery Subjects-Duke University Press (2010)Document267 pages(Perverse Modernities) Christina Sharpe - Monstrous Intimacies - Making Post-Slavery Subjects-Duke University Press (2010)mlaure445No ratings yet

- Hes D6501-03 General Test Methods For CoatingDocument28 pagesHes D6501-03 General Test Methods For CoatingPreetam KumarNo ratings yet

- Types of MicroscopeDocument19 pagesTypes of Microscopesantosh s uNo ratings yet

- Math 252: Eastern Mediterranean UniversityDocument4 pagesMath 252: Eastern Mediterranean UniversityDoğu ManalıNo ratings yet

- Developing The Internal Audit Strategic Plan: - Practice GuideDocument20 pagesDeveloping The Internal Audit Strategic Plan: - Practice GuideMike NicolasNo ratings yet

- I. Pesticide Use in The Philippines: Assessing The Contribution of IRRI's Research To Reduced Health CostsDocument15 pagesI. Pesticide Use in The Philippines: Assessing The Contribution of IRRI's Research To Reduced Health CostsLorevy AnnNo ratings yet

- B.Sc. Quantitative BiologyDocument2 pagesB.Sc. Quantitative BiologyHarshit NirwalNo ratings yet

- Footstep Power Generation Using Piezoelectric SensorDocument6 pagesFootstep Power Generation Using Piezoelectric SensorJeet DattaNo ratings yet

- LISA (VA131 2019) IFU ENG Instructions For Use Rev06Document140 pagesLISA (VA131 2019) IFU ENG Instructions For Use Rev06Ahmed AliNo ratings yet

- Interview Arne Naess 1995Document42 pagesInterview Arne Naess 1995Simone KotvaNo ratings yet

- Public Spaces - Public Life 2013 Scan - Design Interdisciplinary Master Studio University of Washington College of Built EnvironmentsDocument107 pagesPublic Spaces - Public Life 2013 Scan - Design Interdisciplinary Master Studio University of Washington College of Built EnvironmentsSerra AtesNo ratings yet

- 2% L-Leucin 3% PEG 6000Document10 pages2% L-Leucin 3% PEG 6000Con Sóng Âm ThầmNo ratings yet

- P Blockelements 1608Document51 pagesP Blockelements 1608د.حاتممرقهNo ratings yet

- ZSTU 2020 Fall Semester Attendance Record Sheet For Master International Students Outside ChinaDocument3 pagesZSTU 2020 Fall Semester Attendance Record Sheet For Master International Students Outside ChinaAjaz BannaNo ratings yet

- Artificial Neural Networks Bidirectional Associative Memory: Computer Science and EngineeringDocument3 pagesArtificial Neural Networks Bidirectional Associative Memory: Computer Science and EngineeringSohail AnsariNo ratings yet

- Nou-Ab Initio Investigations For The Role of Compositional Complexities in Affecting Hydrogen Trapping and Hydrogen Embrittlement A ReviewDocument14 pagesNou-Ab Initio Investigations For The Role of Compositional Complexities in Affecting Hydrogen Trapping and Hydrogen Embrittlement A ReviewDumitru PascuNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document2 pagesAssignment 1Biru SontakkeNo ratings yet

- Lab Manual MeterologyDocument10 pagesLab Manual MeterologyWaris Nawaz KhanNo ratings yet

- ES-102 Basic Electrical Engineering LTP 3 1 2Document1 pageES-102 Basic Electrical Engineering LTP 3 1 2Doggyman Doggyman DoggymanNo ratings yet

- Romania Approves Neptun Deep ProjectDocument2 pagesRomania Approves Neptun Deep ProjectFloyd BurgessNo ratings yet

- Operator ExamDocument11 pagesOperator ExamFazeel A'zamNo ratings yet

- English Syntax - Andrew RadfordDocument40 pagesEnglish Syntax - Andrew RadfordlarrysaligaNo ratings yet

- Skewness KurtosisDocument26 pagesSkewness KurtosisRahul SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Resiliency Continuum: N. Placer and A.F. SnyderDocument17 pagesThe Resiliency Continuum: N. Placer and A.F. SnyderSudhir RavipudiNo ratings yet

- Learn JAVASCRIPT in Arabic 2021 (41 To 80)Document57 pagesLearn JAVASCRIPT in Arabic 2021 (41 To 80)osama mohamedNo ratings yet

- SOAL PAT Bing Kls 7 2024Document12 pagesSOAL PAT Bing Kls 7 2024Andry GunawanNo ratings yet

- Emerging Themes SheilaDocument8 pagesEmerging Themes SheilaJhon AlbadosNo ratings yet

- Donnie Darko Explanation of What, How and WhyDocument3 pagesDonnie Darko Explanation of What, How and WhyAuric GoldfingerNo ratings yet

- Siw 4Document4 pagesSiw 4Zhuldyz AbilgaisanovaNo ratings yet

- National Park PirinDocument11 pagesNational Park PirinTeodor KrustevNo ratings yet

No Bodys Perfect Renee Green Satch Hoyt

No Bodys Perfect Renee Green Satch Hoyt

Uploaded by

Aarón ReyesOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

No Bodys Perfect Renee Green Satch Hoyt

No Bodys Perfect Renee Green Satch Hoyt

Uploaded by

Aarón ReyesCopyright:

Available Formats

Nka

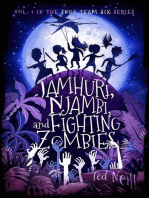

NO BODY’S PERFECT

Kanitra Fletcher

Renée Green, Seen, 1990. Wooden platform, rubber, stamped ink, screen, motorized winking glasses, magnifying glass, spotlight, sound, 81.5 x 81.5 x 53.5 in.

Courtesy the artist and Free Agent Media

Journal of Contemporary African Art • 38–39 • November 2016

142 • Nka DOI 10.1215/10757163-3641788 © 2016 by Nka Publications

Published by Duke University Press

Nka

H

ow do you see blackness? What does it look most fetishized black women in European history.

like? Can it be shown? In seeming response As Lisa Gail Collins also observes, “Contemporary

to such uncertainties, artists Renée Green, artists frequently point to the saga of ‘the Hottentot

Satch Hoyt, and Sheila Pree Bright forwent repre- Venus’ as a deining moment in the representation

sentation of the black body altogether. In installa- of black women in visual culture”—conditions that

tion and photographic works—Seen (1990), Say It Baker’s persona extended beyond the stage to ilm

Loud (2004), and Suburbia (2005–7), respectively— and song. Accordingly, a sound loop of Baker sing-

they instead presented spaces for any body, black ing “Voulez-vous de la canne à sucre?” (“Would

or otherwise, within contexts that signify black you like some sugar cane?”) complements the writ-

lives, histories, and experiences. he works airm ings that are mostly demeaning and lascivious in

that the nature of blackness is not a given, while nature.

they demonstrate ways in which it has come to be Critically, to examine the text, one must climb

regarded as such. Via texts, sounds, and objects the onto the stage and consequently become trapped in

artists challenge us to see not bodies but the cul- the display. Green positioned a loodlight to shine

tural constructions of and around them. Moreover, onto the stage and a white screen at the opposite

Green, Hoyt, and Bright demonstrate that blackness end of the platform to project a silhouette of the

cannot be seen or shown by any body, or, rather, no person’s igure for other gallery visitors to observe.

body is perfect. Further compounding the senses of voyeurism and

heir elimination of bodies serves as a refusal vulnerability, while walking up and down the stage

to perpetuate the simultaneous overexposure and one encounters motorized winking blue eyes peer-

simpliication to which black bodies have been ing up at her from a hole in a loorboard.

historically subjected. Green, Hoyt, and Bright’s he fear and discomfort generated by these

unpeopled scenarios also allow us to recognize how imbalanced relations of the gaze speak to the wider

particular signs prompt the sight of blackness sans social context of power and its relation to sight and

the body or how items might be used as its represen- seeing. Moreover, rather than objectifying black

tation. he exchange of black bodies with objects or female bodies, Green turns the tables on specta-

other igures invites viewers to physically and psy- tors and subjects them to treatment partially echo-

chically identify with black subjects or assess their ing that endured by Baker and Baartman. In fact,

own identiication and expectation of them. he Baartman was “deceitfully promised a rapid and

works ask what might happen and what it means wealthy return to southern Africa ater a short stint

when a nonblack person inhabits a putatively black of public displays in Europe.”1 hus, the tricking

space or experience. Although blackness is oten of viewers to enter the display of Seen evokes her

seen ahead and outside of works of art, is it opaque experience.

or does it have multiple signiications? What are the Jennifer González also airms that “while the

means and meanings of objects that represent black experience of racial objectiication could never be

identities? he absences or exchanges in the works, replicated by the installation, the artist provided the

therefore, reject the equation of and airm the dif- phenomenological conditions for the mechanism of

ference between concepts and bodies of blackness. this objectiication.”2 Green, therefore, inverts and

American artist Renée Green’s installation Seen deconstructs the construction of the black female

speciically turns the tables of past mistreatment of body in visual culture. he apparatuses that typi-

black women’s bodies onto the viewer. One person cally create representations are represented instead,

at a time climbs onto a crude wooden platform inviting us to consider, like Michele Wallace does,

resembling a slave auction block, which serves “what some have called the spectatorial imagina-

as a stage. Across the surface of the loor Green tion of the West, the gaze, the need to study and

stamped extracts from past accounts of Saartjie examine the ‘other,’ fueled by the popularity of such

Baartman and Josephine Baker. Otherwise known inventions and developments as photography, the

as the “Hottentot Venus” and the “Black Venus,” electric light bulb, popular journalism and ilm.”3

respectively, Baartman and Baker were two of the Baker and Baartman’s igures were not viewed

Fletcher Nka • 143

Published by Duke University Press

Nka

loodlights the viewer produces a dark distorted

igure on the screen. In efect, the study of Baker

and Baartman entails the projection of one’s own

fears and desires onto a black body.

Moreover, as the viewer faces the eyes looking

up at her and the light glaring down on her, she

most likely self-consciously comports herself within

this environment. In this sense, her actions relect

the way such circumstances put forward crated

portrayals and coerced performances rather than

genuine personalities. Nonetheless, the continual

incorporation of individuals into the artwork to

Detail from Seen assume the roles of Baker or Baartman heeds

Chandra Mohanty’s call to “look upward . . . [from]

simply on stage and screen; particular devices the particular standpoint of poor indigenous and

mediated their appearances and the public’s views hird World/South women, [which] provides the

of them. most inclusive viewing of systemic power. . . . his

In the absence of black female bodies, Green particular marginalized location makes the politics

presents the ways in which sight, sound, language, of knowledge and the power investments that go

and technology reify historical (mis)perceptions along with it visible.”5

of them. Seen illustrates González’s assertion that Indeed, the writings on the loorboards are not

“race discourse, in all its historical complexity, is proof of black female alterity. but rather evidence of

not reducible to visuality; visual representation a historical power imbalance. Accordingly, within

is merely one of the most powerful techniques by Seen one steps on and stands over them to structur-

which it operates.”4 One encounters multiple per- ally overpower distortions of Baker and Baartman.

spectives on and of black women within the work, Although the viewer is still aware of the myths and

yet no actual black female body is on display. he fallacies that lie beneath her feet, upon Green’s stage

absences of Baker and Baartman highlight the func- she is able to move around and beyond them.

tions of the text, stage, screen, and lights that gen- Individuals also ascend a platform in Afro-

erate impressions and supersede actual presences. British artist Satch Hoyt’s installation Say It Loud,

hus, to reinterpret the title of the work, Baker’s and a monumental stack of approximately ive hundred

Baartman’s bodies were “seen,” not just optically, but books. Relating to black diaspora art, history, and

also mentally. hey were understood in particular culture, the texts appear in a pyramidal shape that

ways based on factors beyond their corporeality. surrounds a stepladder and supports a microphone.

Consequently, they bear meanings (such as those Playing in the background is a sound loop of James

stamped upon the stage) not of their own making. Brown’s famous chorus “Say it loud! I’m black and

Furthermore, the initial encounter with the I’m proud!” However, the recording mutes the word

work prompts the surprise and disorientation of black to allow for others’ speeches.

the viewer who does not expect to go on display but Prompted by the pause in the music, speakers can

must do so to appreciate Green’s arrangement fully. say what makes them “proud” or express themselves

he viewer’s experience of the artwork moves from in any way they choose and thereby translate “black”

typical observation to a performative dimension. into ininite meanings. As Fred Moten stated, “he

his shit alludes to the ways in which Baker and phrase, the broken sentence, holds (everything). . . .

Baartman had to enter speciic, contrived scenarios he quickened disruption of the irreducible phonic

to play roles for onlookers. herefore, images and substance . . . is where universality lies. Here lies

recordings of the women igure more as portrayals universality: in this break, this cut, this rupture.

of others’ desires than their actual personalities. Song cutting speech. Scream cutting song.”6 It is in

To underscore these circumstances, opposite the the “break” of Brown’s lyrics that blackness becomes

144 • Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art • 38–39 • November 2016

Published by Duke University Press

Nka

limitless and transformable. he interruption of the

song with speakers’ statements generates boundless

unpredictability that also speaks to a fundamental

paradox of racial identiication.

On the one hand, countless critics and scholars

have developed theories of blackness. he mag-

nitude of their output is conveyed by the tower-

ing presence of the stacked books that form the

artwork. On the other hand, the numerous texts

indicate the indeiniteness of the subject. hat there

have been so many approaches to blackness airms

the improbability of any stable or essential mean-

ing. Say It Loud’s format, therefore, encourages the

reinterpretation, if not the rejection, of established

concepts. Rather than being ofered for perusal, the

books are closed and repurposed as a podium to

invite the new ideas and words of others.

In this way the closures and omissions are not

denials of blackness; rather, Say It Loud denies

acquiescence to blackness, particularly the mono-

lithic notions popularized in 1968, the year Brown

released his recording and the height of the Black

Power movement. he various speakers’ individual

statements not only indicate the temporality and

variability of blackness, but also allude to the silences

Satch Hoyt, Say It Loud, 2004. Books, metal staircase, microphone, and omissions within black nationalist discourses.

speakers, sound. Dimensions variable. Installation view in Radical Presence:

Black Performance in Contemporary Art at the Contemporary Arts Museum

Hoyt’s eloquent description of his own back-

Houston, 2012. Photo: Jerry Jones ground further underscores the contention that

Detail from Say It Loud

Fletcher Nka • 145

Published by Duke University Press

Nka

Sheila Pree Bright, Untitled 11 (Suburbia), 2005–7. Chromogenic color print, 58 x 48 in. Courtesy the artist

Say It Loud aims less at deining than personalizing Hoyt’s statement speaks to the ways people

blackness. He states: contradict and individualize social classiications.

hus, he efectively collaborates with the speakers

I was born in London to an Afro-Jamaican father and in a way that reconstitutes this process as it mirrors

a white English mother in the late 1950s. . . . As a his past. he altar becomes an “imaginary island,”

hybrid, one learns to navigate the marginal seas of and the igure of the speaker “shape-shits” as one

diference, to remain intact while loating between replaces the next. hroughout these changes, the

the two poles. . . . In efect, we were deconstructing work becomes an ongoing demonstration of the

race and class, inventing our own imaginary islands. performative dimension of blackness.

We, the disenfranchised, fragmented, and marginal- As Maurice Berger attests, “he ‘performative’

ized youth—the black, brown, and beige vanguard encompasses the broader range of human enact-

learning the ancient codes, speaking a new patois: ments and interactions—the performances of our

racialized shape-shiters, reinventing a new black everyday lives, the things we do to survive, to com-

identity.7 municate.”8 Accordingly, Hoyt’s personal statement,

146 • Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art • 38–39 • November 2016

Published by Duke University Press

Nka

as well as that of each speaker in Say It Loud, suggests

that translations of blackness are not only normal,

but also necessary. hey are performative strategies

for inding one’s way through life. Furthermore,

they demonstrate that reinterpretations of black-

ness ultimately make it less restrictive and increase

its potentiality ater 1968 and for the future.

In Suburbia American photographer Sheila Pree

Bright shows how objects also play roles in the

performative dimension of blackness. he series

comprises forty 58-by-48-inch photographs of well-

appointed homes in suburban Atlanta, Georgia, a

city with a large aluent black population. Mostly

due to post–World War II “white light,” however,

Sheila Pree Bright, Untitled 13 (Suburbia), 2005–7. Chromogenic color print,

the popular notion of suburbia is a residential area 58 x 48 in. Courtesy the artist

composed of middle- and upper-class white families.

Bright’s series, therefore, points to the intersection

of race and class as it pertains to geographical space level. However, she must do so without observing

in the United States. Moreover, the impact of her the appearance or behavior of the residents.

series is not derived from any activity in the scenes. For instance, in Untitled 13, the entrance of a

She thwarts viewers’ expectations with rare glimpses home features a casual yet conscious display of

of unidentiiable occupants and the notable yet tacit belongings. Chanel accessories are framed by a

racialization of household objects. large, elegant portrait of a black girl in the back-

he framework of Suburbia emphasizes the fear ground and a sizable vase encircled by an African-

and paranoia that lie at the basis of white light. inspired motif in the foreground. hese elements

he scenes have a voyeuristic feel that comes from of tasteful decoration function as racial signiiers

their formal composition. For instance, it appears as to subtly indicate black ownership. hroughout the

though Bright “cased” the home featured in Untitled series, the viewer receives other occasional clues to

11. She shows the exterior of the house on a rainy the racial identity of the occupants, thereby airm-

day from afar and partially behind a bush. In other ing Jennifer González’s contention:

scenes, the occupants are blurred, concealed, or

fragmented in surreptitious shots that were taken Material culture of everyday life, such as . . . forms

behind a door or a counter and in the relection of of commodity production and consumption, partici-

a mirror. Bright’s camera igures as a tool of surveil- pate in the construction of race discourse. . . . Objects

lance, capturing a realm of American society that come to stand in for subjects not merely in the form

has been largely invisible in mainstream media. of commodity fetish, but as a part of a larger system

As if taken by a private investigator, many of of material and image culture that circulates as a

the images igure as snapshots—photographs taken prosthesis of race discourse through practices of col-

quickly and informally—to be used as evidence of lection, exchange, and exhibition . . . Objects in other

this seemingly foreign territory. he large scale of words can become epidermalized.9

the photographs also heightens the sense of voy-

eurism and gives the viewer the impression that Bright’s series thus critically analyzes how one

she is a detective entering these domestic spaces. reads race through toys (such as black dolls in

Lacking the returned gaze of protagonists, the Untitled 3 and Untitled 6), publications (like a set

design of the scenes in Suburbia enhances their of magazines featuring Barack Obama on the covers

realism. he viewer can imagine she has gained in Untitled 40), or novelties (including the black

access to a restricted area to investigate the nature Americana igurines displayed on a kitchen counter

of middle-class black domesticity on an intimate in Untitled 34). he imagery raises questions about

Fletcher Nka • 147

Published by Duke University Press

Nka

Sheila Pree Bright, Untitled 34 (Suburbia), 2005–7. Chromogenic color print, 58 x 48 in. Courtesy

the artist

Sheila Pree Bright, Untitled 12 (Suburbia), 2005–7. Chromogenic color print, 58 x 48 in. Courtesy the artist

148 • Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art • 38–39 • November 2016

Published by Duke University Press

Nka

how and why the viewer might infer the racial iden- others’ discomfort with the portrayal of her home

tity of the occupants without sight of their bodies, or her presence in Suburbia, she is at peace.

and furthermore, how and why that assumption Bright’s minimization of black corporeality in

afects reception of the images. As Susan Richmond Suburbia further suggests that bodies would not

explains, the series “demonstrates that attempts reveal any inherent truths about blackness. She

to wrest narratives of identity—racial, familial or visualizes how the subjects represent themselves,

otherwise—from photographs require extradiegetic not their race. In scenes of everyday objects, Bright

leaps. Resorting to knowledge and experience demonstrates the diiculty in depicting something

beyond the image, some of these leaps jarringly distinctively or essentially black. In this sense, the

expose the viewer’s unconscious recourse to racial photographs ultimately represent the failure of their

assumptions.”10 implied investigation. he imagined voyeur who

What efect do the occasional blurred or frag- searches through these homes to ind evidence of

mented appearances of bodies have on the viewer? an essential blackness comes up short.

Is the sight of an occupant’s skin the efective culmi- As blackness remains unresolved in Suburbia,

nation of an image? Does it serve as a conirmation this failure and the aforementioned criticism of the

of or an inquiry into blackness? Suburbia suggests series beg questions: Had Bright aimed to represent

that the black body does not answer questions; it a distinct black identity through these homes, what

raises them. Similar to Lorna Simpson’s “anti-por- would that project entail? What would it look like?

traits” of the 1990s, which depicted black subjects Would the depiction of more black bodies and cer-

turned away from the viewer, Bright refuses iden- tain items or symbols suice? Moreover, had Bright

tiications or visual consumption of the residents. “blackened” Suburbia, what would the series com-

In so doing, we might (re)consider our desires for municate? Would it deine blackness for viewers,

subjects to perform or elicit some expression of deceive them, or simply lead them nowhere?

blackness. Ultimately, in all these works Green, Hoyt, and

hus, the objects perform rather than the Bright demonstrate the shiting, dialectical nature

bodies. Despite the inference of social and psy- of blackness—its social, political construction and

chological tensions, as Bridget Cooks explains, its personal, psychological dimension—the under-

“there is little evidence of the drama of daily life. standings of which depend upon context and are

. . . Figures are not performing . . . [and the pho- never inal. Nonetheless, despite this similarity,

tographs] do not solicit empathy from viewers. . . . they do take divergent approaches to matters of

Instead, the banality of suburban life is pictured.”11 black subjectivity that relate to the cultural contexts

In other words, the unremarkableness of Suburbia in which the works were created. For instance, in

makes the series remarkable. Consequently, some Seen, while one identiies with past and present

black viewers have complained that there are too black female igures whose historical experiences

few indications of African American heritage or are recuperated in the process, these subjects also

identity in the work.12 Suburbia also might perplex appear passive. he work hardly suggests black

white viewers who assume or feel secure in notions female agency or resistance. Lorraine O’Grady also

of their diference from black families.13 argues that in terms of “the establishment of sub-

Nonetheless, the inhabitants of these homes, jectivity . . . because [Seen] is addressed more to the

when they are visible, appear comfortable in their other than to the self and seems to deconstruct the

surroundings. In Untitled 12, a partially concealed subject just before it expresses it, it may not unearth

black woman lies on her bed to read an issue of enough new information.”15 In this sense, the activ-

Business Week. Although the diagonals of her igure ity within the piece does not alter, but rather repro-

visually counter the horizontal lines of the furni- duces ongoing historical conditions.

ture, she literally and iguratively appears at ease Rather than a shortcoming, this aspect relects

as the deep red and gold fabrics envelop her.14 his how the beginning of Green’s artistic career in the

enfolding of her body visually airms her belong- late 1980s and early 1990s was inluenced heavily

ing to this lifestyle and environment. Regardless of by cultural and postcolonial theory in the writings

Fletcher Nka • 149

Published by Duke University Press

Nka

of Edward Said, Homi Bhabha, Stuart Hall, Gayatri the aluence and advancement of black people than

Spivak, and other critics.16 In the making of Seen, to their repression.

Green asked, “Who can speak? Where can they Also in the early 2000s, helma Golden popular-

speak . . . How is a ‘whom’ ever identiied . . . What is ized the term post-black. She aimed to classify what

given respect where? What is believed in where?”17 she observed as an emergence of artists “who were

In other words, how does power relate to knowl- adamant about not being labeled as ‘black’ artists,

edge? Further, how do we understand our subjective though their work was steeped, in fact deeply inter-

positions in relation to these circumstances?18 ested, in redeining complex notions of blackness.”19

In the early 2000s, rather than visualize difer- Older approaches to blackness usually assumed a

ence and marginality or “talk back” to others, artists stable black subject, culture, or personality; how-

oten refused or questioned identities. Hoyt’s work ever, in the twenty-irst century, there is a wide-

does not assume a white participant, as opposed to spread sense that racial conditions have changed in

Green’s installation, which arguably expects one. ways that make blackness no longer a foundation,

he tables do not appear to turn that much on a but rather “a question, an object of scrutiny, a pro-

black person within Seen, whereas all raced bodies visional resource at best, and, for some, a burden.”20

equally are consequential in Say It Loud, which calls As Paul Taylor airms, “For post-black thinkers,

for diverse translations of blackness and personal nationalist ideas about cultural self-determination

concepts of pride. Suburbia also poses questions to and about a unique African personality have been

any viewer of any race about whether or not and supplanted by individualist and oten apolitical

how she identiies blackness beyond the body. aspirations, and by appeals to intra-racial diversity

Speakers in Hoyt’s work loudly express their and interracial commonalities.”21

opinions and personalities as well. Say It Loud Say It Loud its in well with this movement.

requires them to take command of the situation and While Hoyt formally and conceptually structures

actively deine themselves. By upsetting the status the entire piece around identiications of black-

quo in the redeinition of blackness, the participants ness, he eliminates the explicit statement of “black”

enact change. While their speeches are addressed and invites us to question and create associations.

to others, their actions are in service of personal Suburbia also avoids overt declarations of race.

expression and cultural transformation, and not While the series presents an underrecognized divi-

just that of black participants, but all who enter sion of the black population, it also suggests many

and consider the space of blackness that the paused commonalities between its residences and other

recording creates. suburban homes of nonblack families.

Suburbia also allows its subjects to express Consequently, these artworks represent diferent

themselves. Rather than being visually consumed, contexts of and approaches to the discursive

they are in fact the consumers, as evidenced by formation of black pasts and peoples. However,

the displays of their wealth throughout the series. they are not at odds. In a sense, Seen is the irst step

Returning to Untitled 13, the subtle hues of beige in a process that Say It Loud and Suburbia advance.

and tan in the foyer are interrupted by a bright pink Seen alerts individuals to historical circumstances,

Chanel bag hanging from the banister of a staircase which the vocal and visual performances of Say It

above a pair of matching high heels. In Untitled 5, Loud and Suburbia defy. Together the works show

luxurious, carefully arranged possessions—jew- processes of deconstruction and reconstruction,

elry, perfumes, and crystal containers—sit on a which are necessary to forestall and complicate the

vanity table. In these images and others, Bright’s signiications of black bodies. Green, Hoyt, and

representation of her secreted subjects via objects, Bright deploy the absence and alteration of bodies in

apparel, and furnishings comprises not only racial, order to encourage the contemplation of our fears,

but also socioeconomic signiiers. he interiors desires, fantasies, and expectations of blackness.

constitute self-conscious performances of class, he artists thus put the onus on the viewers to

which broaden identiications of blackness. Further, substantiate ideas perceived ahead and outside of

Suburbia does so in a manner that speaks more to the black body. In so doing, Seen, Say It Loud, and

150 • Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art • 38–39 • November 2016

Published by Duke University Press

Nka

Suburbia demonstrate that in the representation of responded,] “hat’s the point! To show our commonality. . . . If we

could get past the stereotypes, we could see that.” Bentley, “Sheila

mythic, monolithic blackness, no body’s perfect. Pree Bright’s Look.”

14 Richmond, “Sheila Pree Bright’s Suburbia,” 19.

Kanitra Fletcher is a doctoral candidate in the De- 15 Lorraine O’Grady, “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female

Subjectivity,” in Art, Activism, and Oppositionality: Essays from

partment of History of Art and Visual Studies at Cor-

Aterimage, ed. Grant H. Kester (Durham, NC: Duke University

nell University. She is currently based in Houston, Press, 1994), 272.

Texas, and serves as curator of video art for Land- 16 Elvan Zabunyan, “We Are Here = Nous sommes l̀,” in Renée

marks, the public art program of the University of Green and Nicole Schweizer, Reńe Green: Ongoing Becomings:

Retrospective 1989–2009 (Lausanne, Switzerland: Musée cantonal

Texas at Austin. des Beaux-Arts, 2009), 7–10.

17 Renée Green quoted in Alex Alberro, “he Fragment and

Notes the Flow,” in Reńe Green: Sombras y sẽales / Shadows and Signals

A signiicant portion of this essay was presented at the 2015 College (Barcelona, Spain: Fundací Antoni T̀pies, 2000), 26.

Art Association Conference in New York City. hanks to Professors 18 Ibid., 27.

Margo Crawford and Jessica Santone and the Nka editorial team 19 helma Golden, “Introduction,” in helma Golden et al.,

for their feedback and assistance with earlier versions. Freestyle (New York: Studio Museum in Harlem, 2001), 14.

1 Lisa Gail Collins, he Art of History: African American 20 Paul Taylor, “Black Aesthetics,” Philosophy Compass 5, vol. 1

Women Artists Engage the Past (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers (2010): 10.

University Press, 2002), 25. 21 Ibid.

2 Jennifer A. González, Subject to Display: Reframing Race in

Contemporary Installation Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008),

216. Her emphasis.

3 Michele Wallace, Dark Designs and Visual Culture (Durham,

NC: Duke University Press, 2004), 428.

4 González, Subject to Display, 5.

5 Chandra Talpade Mohanty, “‘Under Western Eyes’ Revisited:

Feminist Solidarity through Anticapitalist Struggles,” Signs 28, no.

2 (2003): 511.

6 Fred Moten, In the Break: he Aesthetics of the Black Radical

Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 39,

43.

7 Satch Hoyt, “Hybrid Navigator,” Small Axe 32 (2010): 151–52.

8 Maurice Berger and Hans Haacke, Minimal Politics:

Performativity and Minimalism in Recent American Art (Baltimore:

Fine Arts Gallery, University of Maryland, 1997), 15.

9 González, Subject to Display, 5–6.

10 Susan Richmond, “Sheila Pree Bright’s Suburbia: Where

Nothing Is Ever Wanting,” Art Papers 31, no. 4 (2007): 20.

11 Bridget Cooks, “Pictures of Home: he Work of Sheila Pree

Bright,” Aterimage 36, no. 2 (2008): 17.

12 Richmond, “Sheila Pree Bright’s Suburbia,” 21. Bridget Cooks

also quotes Bright: “[A book publisher] explained to me that he

grew up during the Civil Rights Movement with Martin Luther

King, Jr. and that I did not have enough signiiers or clues about

African American culture in the work to show that these were

African American homes.” Cooks, “Pictures of Home.” 17. An

interview with Bright also mentions how, during the Santa Fe

Prize Photography Awards, “respected curators, consultants and

photo editor . . . ‘loved the pictures, but they said they didn’t have

enough signiiers in them to show that they were black homes.

What those comments showed me is how seriously a stereotype

is ingrained in a person’s mind. . . . hey expected certain things

to be there and they weren’t.’” Rosalind Bentley, “Sheila Pree

Bright’s Look at ‘Suburbia’ in an Unlikely Place,” Atlanta Journal-

Constitution, February 4, 2014, www.ajc.com/news/entertainment

/sheila-pree-brights-look-at-suburbia-in-an-unlikel/ndBtF/

(accessed August 1, 2015).

13 he aforementioned interview with Bright recounts, “Back

when Suburbia was shown in Santa Fe, one consultant . . . was white

and told the artist that he didn’t understand its point. he homes

pictured didn’t look any diferent from his home, he told her.” [Bright

Fletcher Nka • 151

Published by Duke University Press

You might also like

- Mediated: How the Media Shapes Your World and the Way You Live in ItFrom EverandMediated: How the Media Shapes Your World and the Way You Live in ItRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (55)

- (De) Cypher: Black Notes On Culture & C R I T I C I S M (Spring 2022)Document63 pages(De) Cypher: Black Notes On Culture & C R I T I C I S M (Spring 2022)decypher blackNo ratings yet

- The Nude - A New Perspective, Gill Saunders PDFDocument148 pagesThe Nude - A New Perspective, Gill Saunders PDFRenata Lima100% (7)

- Fred Moten Blackness and NothingnessDocument22 pagesFred Moten Blackness and NothingnessRaphaelNo ratings yet

- Woman As Temptress The Way To (BR) Otherhood in Feminist DystopiasDocument12 pagesWoman As Temptress The Way To (BR) Otherhood in Feminist DystopiasDerouiche MariemNo ratings yet

- "Jewels Brought From Bondage": Black Music and The Politics of AuthenticityDocument20 pages"Jewels Brought From Bondage": Black Music and The Politics of AuthenticityJess and MariaNo ratings yet

- Gender Portrayals in Classical Greek Statuary - Melissa Huang - Musings On Art and GenderDocument8 pagesGender Portrayals in Classical Greek Statuary - Melissa Huang - Musings On Art and GenderMerlinNo ratings yet

- Myerhoff B Life History Among The ElderlyDocument10 pagesMyerhoff B Life History Among The ElderlyRodrigo MurguíaNo ratings yet

- Bell Hooks - The Oppositional GazeDocument11 pagesBell Hooks - The Oppositional GazeMARINA PEREIRA100% (1)

- Hall Culture, Comunity, NationDocument8 pagesHall Culture, Comunity, NationHerrSergio SergioNo ratings yet

- Bending and Torqueing Into A "Willful Subject"Document4 pagesBending and Torqueing Into A "Willful Subject"Hayv KahramanNo ratings yet

- Fernard Deligny - The Arachnean and Other Texts PDFDocument245 pagesFernard Deligny - The Arachnean and Other Texts PDFlucasNo ratings yet

- No White Picket Fence: A Verbatim Play about Young Women’s Resilience through Foster CareFrom EverandNo White Picket Fence: A Verbatim Play about Young Women’s Resilience through Foster CareNo ratings yet

- 9853 1287 01d Overhaul Instructions DHR6 H Ver. B PDFDocument68 pages9853 1287 01d Overhaul Instructions DHR6 H Ver. B PDFMiguel CastroNo ratings yet

- Thomas F. DeFrantz, Anita Gonzalez - Black Performance Theory-Duke University Press (2014)Document292 pagesThomas F. DeFrantz, Anita Gonzalez - Black Performance Theory-Duke University Press (2014)Bruno De Orleans Bragança ReisNo ratings yet

- Black Performance Theory Edited by Thomas F. DeFrantz and Anita GonzalezDocument26 pagesBlack Performance Theory Edited by Thomas F. DeFrantz and Anita GonzalezDuke University Press100% (4)

- DEFRANTZ-GONZALEZ - Black Performance Thoery (Intro)Document26 pagesDEFRANTZ-GONZALEZ - Black Performance Thoery (Intro)IvaaliveNo ratings yet

- From Day Fred MotenDocument16 pagesFrom Day Fred MotenAriana ShapiroNo ratings yet

- Howard Barker InterviewDocument4 pagesHoward Barker InterviewMike PugsleyNo ratings yet

- WARK, Mckenzie. The Cis Gaze and It's OthersDocument15 pagesWARK, Mckenzie. The Cis Gaze and It's OthersBruno De Orleans Bragança ReisNo ratings yet

- Reflections On Echo-Sound by Women Artists in Britain Jean FisherDocument7 pagesReflections On Echo-Sound by Women Artists in Britain Jean FisherNicole HewittNo ratings yet

- Incorporeal BlacknessDocument38 pagesIncorporeal BlacknessMíša SteklNo ratings yet

- Fred Moten - Black-OpDocument5 pagesFred Moten - Black-OpNorman AjariNo ratings yet

- 10 - The Gendered Subject TaraDocument31 pages10 - The Gendered Subject TaraPremNo ratings yet

- Paris Is Burning - Bell HookDocument8 pagesParis Is Burning - Bell Hookgasparinflor100% (1)

- Morehshin AllahyariDocument3 pagesMorehshin AllahyariIkram Rhy NNo ratings yet

- Deiure-Vcdb-1 FeedbackDocument3 pagesDeiure-Vcdb-1 Feedbackapi-711324507No ratings yet

- Conflicting Identities in The Euripidean Chorus: Laura SwiftDocument25 pagesConflicting Identities in The Euripidean Chorus: Laura SwiftLuka RomanovNo ratings yet

- Moten in The Break I Resistance of The ObjectDocument25 pagesMoten in The Break I Resistance of The ObjectDaniel Aguirre Oteiza100% (1)

- Understanding Blackness through Performance: Contemporary Arts and the Representation of IdentityFrom EverandUnderstanding Blackness through Performance: Contemporary Arts and the Representation of IdentityNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 213.55.95.215 On Mon, 05 Dec 2022 11:10:38 UTCDocument13 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 213.55.95.215 On Mon, 05 Dec 2022 11:10:38 UTCAmsalu GetachewNo ratings yet

- The Sadien Sphinx and The Riddle of Black Female IdentityDocument9 pagesThe Sadien Sphinx and The Riddle of Black Female Identityapi-317483746No ratings yet

- Tormented Torsos, The Pornographic Imagination, and Articulated Minors: The Works of Hans Bellmer and Cindy ShermanDocument15 pagesTormented Torsos, The Pornographic Imagination, and Articulated Minors: The Works of Hans Bellmer and Cindy Shermanjeff tehNo ratings yet

- Jared Sexton, "All Black Everything"Document10 pagesJared Sexton, "All Black Everything"Christoph CoxNo ratings yet

- Minor Vices - Observing DisdainDocument8 pagesMinor Vices - Observing DisdainstavrianakisNo ratings yet

- Interview - Jared SextonDocument16 pagesInterview - Jared SextonBen CrossanNo ratings yet

- The Green Studies Reader From Romanticism To Ecocriticism (Laurence Coupe) (Z-Library) (1) - 158-162Document5 pagesThe Green Studies Reader From Romanticism To Ecocriticism (Laurence Coupe) (Z-Library) (1) - 158-162beatrice ciucchiNo ratings yet

- Epistemology and Simulacra in Tarkovsky's SolarisDocument32 pagesEpistemology and Simulacra in Tarkovsky's SolarisAnshuman FotedarNo ratings yet

- Maroon Choreography by Fahima IfeDocument145 pagesMaroon Choreography by Fahima Ifemlaure445No ratings yet

- Drama Notes 2020Document7 pagesDrama Notes 2020TiaNo ratings yet

- Mac Interviews WhitleyDocument5 pagesMac Interviews Whitleymikeclelland100% (2)

- 777320Document9 pages777320Cal DeaNo ratings yet

- After Blackness, Then BlacknesDocument19 pagesAfter Blackness, Then BlacknesNicholas BradyNo ratings yet

- RICHARD DE UTSCH ReviewDocument1 pageRICHARD DE UTSCH ReviewΚλήμης ΠλεξίδαςNo ratings yet

- Selling Hot Pussy - Representations of Black Female Sexuality in The Cultural Marketplace. Bell Hooks PDFDocument13 pagesSelling Hot Pussy - Representations of Black Female Sexuality in The Cultural Marketplace. Bell Hooks PDFGiovanna BoscoNo ratings yet

- Marie Thompson - Feminised Noise and The Dotted Line' of Sonic ExperimentalismDocument18 pagesMarie Thompson - Feminised Noise and The Dotted Line' of Sonic ExperimentalismLucas SantosNo ratings yet

- William S. Haney II - Postmodern Theater & The Void of Conceptions-Cambridge Scholars Publishing (2006) PDFDocument169 pagesWilliam S. Haney II - Postmodern Theater & The Void of Conceptions-Cambridge Scholars Publishing (2006) PDF-No ratings yet

- Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man and Female StereotypesDocument4 pagesRalph Ellison's Invisible Man and Female StereotypesanachronousNo ratings yet

- When A Woman Is Nude: A Critical Visual Analysis of "Harlem" PhotographDocument5 pagesWhen A Woman Is Nude: A Critical Visual Analysis of "Harlem" PhotographFady SamyNo ratings yet

- Afrofuturism and Post-Soul Possibility in Black Popular MusicDocument14 pagesAfrofuturism and Post-Soul Possibility in Black Popular Musicmafefil18No ratings yet

- Let's Conjure Some GhostsDocument12 pagesLet's Conjure Some GhostsIanNo ratings yet

- Core Program Critic-In-Residence (Glassell School of Art / Museum of Fine Arts, Houston)Document23 pagesCore Program Critic-In-Residence (Glassell School of Art / Museum of Fine Arts, Houston)AndyNo ratings yet

- Cinema From Within InterrogatiDocument110 pagesCinema From Within InterrogatiAkhona NkumaneNo ratings yet

- Chasing Rainbows - Black Cracker and Queer, Trans AfrofuturityDocument11 pagesChasing Rainbows - Black Cracker and Queer, Trans AfrofuturitymilaNo ratings yet

- The Acteon Complex: Gaze, Body, and Rites of Passage in Hedda Gabler'Document22 pagesThe Acteon Complex: Gaze, Body, and Rites of Passage in Hedda Gabler'ipekNo ratings yet

- (Perverse Modernities) Christina Sharpe - Monstrous Intimacies - Making Post-Slavery Subjects-Duke University Press (2010)Document267 pages(Perverse Modernities) Christina Sharpe - Monstrous Intimacies - Making Post-Slavery Subjects-Duke University Press (2010)mlaure445No ratings yet

- Hes D6501-03 General Test Methods For CoatingDocument28 pagesHes D6501-03 General Test Methods For CoatingPreetam KumarNo ratings yet

- Types of MicroscopeDocument19 pagesTypes of Microscopesantosh s uNo ratings yet

- Math 252: Eastern Mediterranean UniversityDocument4 pagesMath 252: Eastern Mediterranean UniversityDoğu ManalıNo ratings yet

- Developing The Internal Audit Strategic Plan: - Practice GuideDocument20 pagesDeveloping The Internal Audit Strategic Plan: - Practice GuideMike NicolasNo ratings yet

- I. Pesticide Use in The Philippines: Assessing The Contribution of IRRI's Research To Reduced Health CostsDocument15 pagesI. Pesticide Use in The Philippines: Assessing The Contribution of IRRI's Research To Reduced Health CostsLorevy AnnNo ratings yet

- B.Sc. Quantitative BiologyDocument2 pagesB.Sc. Quantitative BiologyHarshit NirwalNo ratings yet

- Footstep Power Generation Using Piezoelectric SensorDocument6 pagesFootstep Power Generation Using Piezoelectric SensorJeet DattaNo ratings yet

- LISA (VA131 2019) IFU ENG Instructions For Use Rev06Document140 pagesLISA (VA131 2019) IFU ENG Instructions For Use Rev06Ahmed AliNo ratings yet

- Interview Arne Naess 1995Document42 pagesInterview Arne Naess 1995Simone KotvaNo ratings yet

- Public Spaces - Public Life 2013 Scan - Design Interdisciplinary Master Studio University of Washington College of Built EnvironmentsDocument107 pagesPublic Spaces - Public Life 2013 Scan - Design Interdisciplinary Master Studio University of Washington College of Built EnvironmentsSerra AtesNo ratings yet

- 2% L-Leucin 3% PEG 6000Document10 pages2% L-Leucin 3% PEG 6000Con Sóng Âm ThầmNo ratings yet

- P Blockelements 1608Document51 pagesP Blockelements 1608د.حاتممرقهNo ratings yet

- ZSTU 2020 Fall Semester Attendance Record Sheet For Master International Students Outside ChinaDocument3 pagesZSTU 2020 Fall Semester Attendance Record Sheet For Master International Students Outside ChinaAjaz BannaNo ratings yet

- Artificial Neural Networks Bidirectional Associative Memory: Computer Science and EngineeringDocument3 pagesArtificial Neural Networks Bidirectional Associative Memory: Computer Science and EngineeringSohail AnsariNo ratings yet

- Nou-Ab Initio Investigations For The Role of Compositional Complexities in Affecting Hydrogen Trapping and Hydrogen Embrittlement A ReviewDocument14 pagesNou-Ab Initio Investigations For The Role of Compositional Complexities in Affecting Hydrogen Trapping and Hydrogen Embrittlement A ReviewDumitru PascuNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document2 pagesAssignment 1Biru SontakkeNo ratings yet

- Lab Manual MeterologyDocument10 pagesLab Manual MeterologyWaris Nawaz KhanNo ratings yet

- ES-102 Basic Electrical Engineering LTP 3 1 2Document1 pageES-102 Basic Electrical Engineering LTP 3 1 2Doggyman Doggyman DoggymanNo ratings yet

- Romania Approves Neptun Deep ProjectDocument2 pagesRomania Approves Neptun Deep ProjectFloyd BurgessNo ratings yet

- Operator ExamDocument11 pagesOperator ExamFazeel A'zamNo ratings yet

- English Syntax - Andrew RadfordDocument40 pagesEnglish Syntax - Andrew RadfordlarrysaligaNo ratings yet

- Skewness KurtosisDocument26 pagesSkewness KurtosisRahul SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Resiliency Continuum: N. Placer and A.F. SnyderDocument17 pagesThe Resiliency Continuum: N. Placer and A.F. SnyderSudhir RavipudiNo ratings yet

- Learn JAVASCRIPT in Arabic 2021 (41 To 80)Document57 pagesLearn JAVASCRIPT in Arabic 2021 (41 To 80)osama mohamedNo ratings yet

- SOAL PAT Bing Kls 7 2024Document12 pagesSOAL PAT Bing Kls 7 2024Andry GunawanNo ratings yet

- Emerging Themes SheilaDocument8 pagesEmerging Themes SheilaJhon AlbadosNo ratings yet

- Donnie Darko Explanation of What, How and WhyDocument3 pagesDonnie Darko Explanation of What, How and WhyAuric GoldfingerNo ratings yet

- Siw 4Document4 pagesSiw 4Zhuldyz AbilgaisanovaNo ratings yet

- National Park PirinDocument11 pagesNational Park PirinTeodor KrustevNo ratings yet