Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Semiconstrained Total Elbow Arthroplasty-1

Semiconstrained Total Elbow Arthroplasty-1

Uploaded by

Ευαγγελια ΚιμπαρηCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Semiconstrained Total Elbow Arthroplasty-1

Semiconstrained Total Elbow Arthroplasty-1

Uploaded by

Ευαγγελια ΚιμπαρηCopyright:

Available Formats

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Semiconstrained Total Elbow Arthroplasty for

Posttraumatic Arthritis or Deformities of the Elbow:

A Prospective Study

Izaäk F. Kodde, MD, Roger P. van Riet, MD, PhD, Denise Eygendaal, MD, PhD

Purpose To report the short-term results for posttraumatic total elbow arthroplasty.

Methods We included patients presenting to our hospital with symptomatic chronic posttrau-

matic arthritis or deformities of the elbow, aged 55 to 90 years. All patients had reconstruc-

tion with a Coonrad-Morrey prosthesis. We performed clinical follow-up after 2, 6, 12, 24,

and 36 months, consisting of physical examination, standard radiographs, and calculation of

the Mayo elbow performance index.

Results A total of 17 patients were enrolled in this study and had a mean follow-up of 32

months. Mean preoperative flexion arc was 67° and 105° postoperatively. The mean

preoperative Mayo elbow performance index score was 54 (range, 30 – 80) and improved to

a postoperative score of 93 (range, 60 –100). We encountered 6 complications in 5 patients.

Four complications required surgical intervention and 2 minor complications were treated

noninvasively.

Conclusions Short-term functional outcomes after total elbow arthroplasty in this prospective

cohort of patients with posttraumatic arthritis or deformities of the elbow were good

according to mean postoperative measurements. (J Hand Surg 2013;38A:1377–1382. Copy-

right © 2013 by the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. All rights reserved.)

Level of evidence/type of study Therapeutic IV.

Key words Elbow, functional outcome, posttraumatic, total elbow arthroplasty.

T

HE ELBOW IS INVOLVED IN 7% of all adult frac- failure, and/or posttraumatic osteoarthritis are reported

tures, and it is predicted that the number of in up to 20% of cases.3,4

fractures of the distal humerus in the elderly The sequelae of these complications and of posttrau-

will increase.1,2 The reference standard for the treat- matic elbow arthritis can be treated by arthrodesis,

ment of fractures of the distal humerus is open reduc- interposition arthroplasty, or total elbow arthroplasty

tion and internal fixation (ORIF). Despite advances in (TEA). Generally, arthrodesis of the elbow relieves pain

elbow fracture fixation systems, the complication rates and restores strength, but it is accompanied by a major

remain high because malunion, nonunion, hardware functional impairment. Interposition arthroplasty re-

lieves pain as well and improves motion, but results are

From the Department of Orthopaedics, Upper Limb Unit, Amphia Hospital, Breda, The Netherlands;

and the Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Monica Hospital, Deurne, Belgium. unpredictable. Persistent instability is often found,

Received for publication January 28, 2012; accepted in revised form March 26, 2013. which results in poor functional outcomes.5–7 Good

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received related directly or indirectly to the

results of TEA for a broad variety of chronic posttrau-

subject of this article. matic elbow disorders are reported in numerous retro-

Corresponding author: Izaäk F. Kodde, MD, Department of Orthopaedics, Amphia Hospital, spective studies.8 –17

Post-box 90158, 4800 RK Breda, The Netherlands; e-mail: if.kodde@hotmail.com. However, most reports on TEA for posttraumatic

0363-5023/13/38A07-0014$36.00/0 conditions originate from authors who were involved in

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.03.051

the design of the implant, and a systematic review by

© ASSH 䉬 Published by Elsevier, Inc. All rights reserved. 䉬 1377

1378 TEA IN POSTTRAUMATIC ELBOW ARTHRITIS

Voloshin et al18 revealed complications in 38% of wear was recognized as an asymmetric angle of more

TEAs placed for posttraumatic sequelae. These high than 7° of the CM implant at the bearing surface, as a

complication rates and concerns about the implant du- result of deterioration of the ulnohumeral polyethylene-

rability in this population have limited the widespread bearing surface.20 Radiolucent lines were classified and

use of TEA for posttraumatic disorders. subdivided into 5 types: type 0, no radiolucent lines or

The purpose of this study was to prospectively eval- lines involving less than 1 mm and less than 50% of

uate the complication rate and effect of complications interface; type 1, lines involving greater than 1 mm and

on the early functional outcome of the Coonrad-Morrey less than 50% of interface; type 2, lines involving

(CM) TEA (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) for chronic posttrau- greater than 1 mm and greater than 50% of interface;

matic elbow arthritis. type 3, lines involving greater than 2 mm and complete

interface; and type 4, clear radiographic signs of loos-

PATIENTS AND METHODS ening, such as shifting of the components.13

We designed a prospective cohort study to evaluate

clinical results of the CM TEA for symptomatic post- Surgical technique

traumatic arthritis or deformities. Chronic conditions We administered prophylactic antibiotics (1,000 mg

such as nonunion, malunion, persistent dislocation, cephazolin intravenously) 30 minutes preoperatively.

and/or painful arthritis of the elbow were included. We We made a posterior midline skin incision and used a

treated 17 consecutive patients (ages 55– 82 y; 4 men triceps-splitting approach. The ulnar nerve was identi-

and 13 women) between 2006 and 2011. Patients with fied, released, not transposed, and protected throughout

nontraumatic degenerative changes, acute elbow the procedure. We identified the medial and lateral

trauma, active infection or history of deep infection, collateral ligaments when possible and released them at

poor compliance with regard to after-treatment, or up- their humeral attachments. The distal humerus and

per extremity paralysis, and patients with a nonrestor- proximal ulna were prepared for a CM prosthesis. We

able triceps function were excluded from the study. We implanted prostheses using tobramycin-impregnated

obtained informed consent from all patients. Exemption bone cement (Simplex Bone Cement Powder; Stryker,

of institutional review board approval was granted, be- Hamilton, Ontario, Canada). Postoperatively, antibiot-

cause the protocol used in this study is the current ics were continued for 48 hours, and oral meloxicam

standard of care in our hospital. was routinely prescribed for 1 week.

All patients underwent a preoperative clinical assess- The elbow was placed in 90° flexion with neural

ment by the surgeon, consisting of range of motion rotation in a plaster splint. After 48 hours, a removable

(ROM), assessment of stability, and calculation of the splint was applied in 30° flexion and physical therapy

Mayo elbow performance index (MEPI). The MEPI is was started. During the first 6 weeks, active extension

based on 4 items (pain, range of motion, stability, and was avoided. Patients were advised to not lift objects

elbow function). A total score between 95 and the over 5 kg.

maximum 100 points is considered excellent; 80 to 94 We performed statistical analysis using paired t-test,

is good; 60 to 79 is fair, and less than 60 points is poor. sign test, and Wilcoxon signed-ranks test to compare

We obtained standard calibrated radiographs (antero- preoperative and postoperative changes in numerical

posterior and lateral) of the elbow before surgery. A data. We used the independent t-test to compare numer-

single surgeon (D.E.) performed all procedures. ical data between groups of patients in this cohort.

Postoperative clinical evaluation by an orthopedic Results were considered statistically significant at

nurse practitioner took place at 8 weeks, 6 months, and P ⬍ .05.

1, 2, 3, and 4 years, and consisted of range of motion,

strength, stability, neurological status, and standard an-

RESULTS

teroposterior and lateral radiographs. The MEPI ques-

tionnaire was completed. Radiographs were assessed Initial clinical data

for periprosthetic fractures, heterotopic ossifications, A total of 17 patients with a minimum follow-up of 12

bushing wear, and radiolucent lines. We classified het- months were enrolled in the study. One patient died 4

erotopic ossification according to Hastings and Gra- years after surgery of causes unrelated to the TEA.

ham.19 Class I lesions are subclinical. Class IIA lesions There was no further loss to follow-up. The average age

limit flexion-extension. Class IIB lesions limit prona- of patients at time of surgery was 70 years (range,

tion-supination. Class IIC lesions limit motion in both 55– 82 y). The dominant elbow was affected in 47% of

planes. Class III describes complete ankylosis. Bushing patients. Mean time of follow-up was 32 months (range,

JHS 䉬 Vol A, July

TEA IN POSTTRAUMATIC ELBOW ARTHRITIS 1379

TABLE 1. Comparison of Elbow Function, Heterotopic Ossifications, Complications, and MEPI Score

Between Patients With and Without Previous Operations

Patients Preoperative Postoperative Preoperative Postoperative Heterotopic

(%) FE FE Prosup Prosup Ossification Complications MEPI

Previous 14 (82%) 74° 107° 114° 134° 6 4 93

operation

No previous 3 (18%) 35° 93° 113° 90° 2 1 97

operation

FE, flexion-extension arc; Prosup, prosupination arc.

TABLE 2. Preoperative and Postoperative Range of Motion

Flexion Extension Flexion Arc Pronation Supination Prosupination Arc

Preoperative 100 33 67 57 57 114

Postoperative 126 21 105 66 60 126

P value .001 .112 .002 .076 .579 .215

12– 69 mo), and the average time from injury to surgery Radiographic outcome

was 100 months (range, 2 mo to 56 y). At the latest follow-up, we found signs of hetero-

There was severe posttraumatic arthritis of the elbow topic ossifications in 8 patients (47%), 7 of whom

joint in 11 patients. Four patients had a malunion after were classified as Hastings and Graham class I and

an intra-articular fracture of the distal humerus, 1 had 1 of whom was classified as class IIA. We saw

nonunion after an intra-articular fracture of the distal radiolucent lines on the radiographs of 4 patients,

humerus, and 1 had nonunion of an extra-articular frac- 1 of whom was graded as type 1 and 3 of whom

ture of the distal humerus. These injuries also resulted were type 4. One patient had a loose humeral

in 2 flail elbows, 1 ankylosis, and 1 ulnar nerve dys- component after a deep infection, 1 had a loose

function. Initial injuries included 1 or more fractures in humeral component after a fall on the arm with a

16 patients, consisting of humerus fractures in 10 pa- subsequent periprosthetic fracture, and another pa-

tients, radius fractures in 6, and ulna fractures in 3. Six tient had aseptic loosening of the ulnar component.

of these had fracture-dislocations. One patient had post- There were no signs of bushing wear in any of

traumatic arthritis resulting from a chronic posterolat- these patients at latest follow-up. Figures 1 and 2

eral dislocation. show an example of failed ORIF followed by TEA.

A total of 14 patients (82%) had previous surgery on

the elbow before implantation of the TEA. Previous Complications

surgery consisted of ORIF in 9 patients, radial head In 5 patients (29%) there were a total of 6 complica-

resection in 2 patients, implantation of a radial head tions. These complications consisted of 2 minor com-

prosthesis in 2 patients, and a medial epicondyle resec- plications not requiring reoperation and 4 major com-

tion in 1 patient. Table 1 compares the groups of pa- plications requiring surgical management. We found

tients with and without previous surgery on the elbow. severe stiffness in 1 patient. Arc of motion improved

from 30° to 80° with intensive physiotherapy and use of

Functional outcome a continuous passive motion machine. The other minor

The mean preoperative MEPI score was 54 (range, complication was a superficial skin infection that re-

30 – 80) and improved to a postoperative score of 93 solved within a week using oral antibiotics.

(range, 60 –100) (P ⬍ .001). One patient had a fair With regard to the major complications, 1 patient

result; the other 16 (94%) had a good or excellent MEPI had persisting ulnar nerve dysesthesia, which resolved

score. Table 2 lists preoperative and postoperative mo- after an ulnar nerve decompression. Three patients had

tions. loosening of a prosthetic component, as described in the

JHS 䉬 Vol A, July

1380 TEA IN POSTTRAUMATIC ELBOW ARTHRITIS

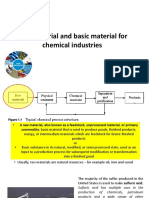

FIGURE 1: Example of unsuccessful ORIF. This patient had ORIF after a fracture of the distal humerus and subsequently a

second operation with autologous bone substitution and new fixation after an olecranon osteotomy because of a nonunion.

A Anteroposterior view. B Lateral view.

FIGURE 2: The same elbow after removal of hardware during a first operation and implantation of a Coonrad-Morrey prosthesis

during a second operation. A Anteroposterior view. B Lateral view.

section on radiographic outcome. The patient with a maintained. The patient with a deep infection developed a

periprosthetic fracture was treated with a plate osteosyn- chronic draining synovio-cutaneous fistula but accepted

thesis of the humerus, while the humeral component was this situation and refused further surgical intervention. The

JHS 䉬 Vol A, July

TEA IN POSTTRAUMATIC ELBOW ARTHRITIS 1381

patient with aseptic loosening has been scheduled for a TABLE 3. Comparison of Complications Between

revision of the loose implant. This Study and the Literature, According to the

Final MEPI scores were 83 for the 5 patients with Systematic Review by Voloshin et al18

complications, compared with 98 for patients without

complications (P ⫽ .09). The ROM was 87°, compared This study, no. Literature,

Complication (%) %

with 112° in favor of patients without complications

(P ⫽ .05). Deep infection (and loosening 1 (6) 3

component)

DISCUSSION Superficial infection 1 (6) *

Aseptic loosening component 1 (6) 14

The results of TEA for posttraumatic elbow disorders

Periprosthetic fracture (and 1 (6) 2

have been reported to be good in most retrospective

loosening component)

studies.8 –17 In this prospective study, functional out-

Ulnar nerve dysesthesia 1 (6) 3

comes after TEA in patients with posttraumatic arthritis (without nerve

or deformities of the elbow were good according to the transposition)

mean postoperative MEPI score (93). One patient Limited range of motion 1 (6) *

with loosening of the humeral component and a Triceps tendon dissection 0 2

malunion of the humerus after a traumatic (triceps split approach)

periprosthetic fracture had a fair result. These re- Overall 6 (35) 38

sults are slightly better than results reported by

others (64% to 83% of patients with a good or *No information in systematic review.

excellent result and mean MEPI scores of 75– 82

points for posttraumatic prosthesis place-

ment).8,13,15,17,21 However, some of these studies al23 reported on 10 patients who had a CM revision

were based on earlier generations of implants or had because of bushing wear or C-ring failure after an

a longer patient follow-up and therefore reported average of 60 months (range, 9 mo to 12 y).23 In the

more implant-related complications.17,20 current study, there were no radiographic signs of bush-

There were 14 patients (82%) with previous surgery ing wear at follow-up, although 1 case of early aseptic

on the elbow, which is similar to 90% in a series by loosening occurred.

Throckmorton et al.17 Prior surgery increases perioper- Complication rates after TEA are higher than those

ative risks because of possible altered anatomy, loss of after replacement surgery of other large joints.24 Until

bone stock, heterotopic ossification, wound problems, 1993, the complication rate after TEA was up to 43%,

and infections. In the current study, there were no decreasing to 22% to 38% in recent literature, according

significant differences in motion, MEPI scores, and to a systematic review by Voloshin and colleagues.18

complications between patients with and without pre- They found a complication rate of 38% for posttrau-

vious operations. However, this comparison is under- matic TEA, compared with 22% and 24% for TEA in

powered, because there were only 3 patients without acute distal humerus fractures and rheumatoid arthritis,

prior surgery. respectively, with a significant difference between the

The semiconstrained linked design of the CM pros- acute fractures and chronic posttraumatic arthritis. The

thesis is well suited for posttraumatic reconstruction most frequent reported complications were aseptic

because its function does not depend on the integrity of component loosening (5% based on clinical examina-

the epicondyles, collateral ligaments, or radial head. tion; 14% based on clinical examination and radio-

This may account for the relatively good results in our graphic radiolucency), instability (5%), and deep infec-

cohort. However, it has also been suggested that this tion (3%). There were significantly fewer reports of

design may be at risk for early bushing wear in this instability in patients who had a linked device18; how-

population.22 Cil et al22 observed evident bushing wear ever, this may be at the cost of component loosening. In

in all 5 study patients who had deficiency of the epi- our series, there were 3 patients with component loos-

condyles and were aged younger than 65 years, within ening. A deep infection occurred in 1 patient. These

5 years.22 This phenomenon can be explained by the results are in accord with the numbers of Voloshin et al

fact that the increased constraint offered by a linked (Table 3). The minor complications (limitation of mo-

design places greater stress on the bushing and implant– tion and superficial skin infection) we report are not

bone interfaces, which may lead to increased rates of described in their systematic review. With inclusion of

bushing wear and/or component loosening. Wright et these minor complications, our overall complication

JHS 䉬 Vol A, July

1382 TEA IN POSTTRAUMATIC ELBOW ARTHRITIS

rate of 35% is comparable to other studies. However, if 7. McAuliffe JA, Burkhalter WE, Ouellette EA, Carneiro RS. Com-

pression plate arthrodesis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br.

temporary postoperative stiffness of the elbow were 1992;74(2):300 –304.

discarded, the complication rate would be 29%. 8. Hildebrand KA, Patterson SD, Regan WD, MacDermid JC, King GJ.

This study is limited by the short-term follow-up. In Functional outcome of semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty.

particular, implant-related complications may be under- J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(10):1379 –1386.

9. Inglis AE, Inglis AE, Jr., Figgie MM, Asnis L. Total elbow arthro-

rated because complications tend to occur with time. plasty for flail and unstable elbows. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;

Continuation of follow-up is therefore necessary to 6(1):29 –36.

evaluate implant-related long-term complications. An- 10. Lee DH. Post-traumatic elbow arthritis and arthroplasty. Orthop Clin

North Am. 1999;30(1):141–162.

other limitation is the relatively small number of pa- 11. Mansat P, Morrey BF. Semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty for

tients included in this cohort. Further prospective stud- ankylosed and stiff elbows. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(9):1260 –

ies based on larger groups of patients are needed to 1268.

12. Moro JK, King GJ. Total elbow arthroplasty in the treatment of

compare posttraumatic subgroups. post-traumatic conditions of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res.

Most of the current literature on CM TEA for post- 2000;(370):102–114.

traumatic elbow trauma is authored by the implant 13. Morrey BF, Adams RA, Bryan RS. Total replacement for post-

developers and might therefore be at risk for systematic traumatic arthritis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(4):

607– 612.

bias.25 The current study addresses TEA for posttrau- 14. Ramsey ML, Adams RA, Morrey BF. Instability of the elbow treated

matic elbow arthritis in a prospective fashion, in a with semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am.

European institution, which was independent from the 1999;81(1):38 – 47.

15. Schneeberger AG, Adams R, Morrey BF. Semiconstrained total

development of the implant. The functional outcomes elbow replacement for the treatment of post-traumatic osteoarthrosis.

after TEA in this cohort of patients with posttraumatic J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(8):1211–1222.

arthritis of the elbow were good according to the mean 16. Schneeberger AG, Meyer DC, Yian EH. Coonrad-Morrey total el-

bow replacement for primary and revision surgery: a 2- to 7.5-year

postoperative MEPI score of 93. Despite the advances

follow-up study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16(3 Suppl):S47–

in TEA designs, the complication rate of 35% in the S54.

current study remains high. Although the differences 17. Throckmorton T, Zarkadas P, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Morrey B. Failure

were not significant, there is a tendency for these com- patterns after linked semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty for

post-traumatic arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(6):1432–

plications to adversely affect MEPI scores and motion 1441.

in these patients. In general, TEA can still be considered 18. Voloshin I, Schippert DW, Kakar S, Kaye EK, Morrey BF. Com-

as the salvage procedure of choice for posttraumatic plications of total elbow replacement: a systematic review. J Shoul-

der Elbow Surg. 2011;20(1):158 –168.

elbow disorders. 19. Hastings H II, Graham TJ. The classification and treatment of

heterotopic ossification about the elbow and forearm. Hand Clin.

REFERENCES 1994;10(3):417– 437.

1. Bernardino S. Total elbow arthroplasty: history, current concepts, 20. Lee BP, Adams RA, Morrey BF. Polyethylene wear after total elbow

and future. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(11):1217–1221. arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(5):1080 –1087.

2. Palvanen M, Kannus P, Niemi S, Parkkari J. Secular trends in distal 21. Amirfeyz R, Blewitt N. Mid-term outcome of GSB-III total elbow

humeral fractures of elderly women: nationwide statistics in Finland arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and patients with

between 1970 and 2007. Bone. 2010;46(5):1355–1358. post-traumatic arthritis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129(11):

3. Hastings H II, Theng CS. Total elbow replacement for distal hu- 1505–1510.

merus fractures and traumatic deformity: results and complications 22. Cil A, An KN, O’Driscoll SW. Custom triflange outrigger ulnar

of semiconstrained implants and design rationale for the Discovery component in revision total elbow arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow

Elbow System. Am J Orthop. 2003;32(9 Suppl):20 –28. Surg. 2011;20(2):192–198.

4. Chalidis B, Dimitriou C, Papadopoulos P, Petsatodis G, Giannoudis 23. Wright TW, Hastings H. Total elbow arthroplasty failure due to

PV. Total elbow arthroplasty for the treatment of insufficient distal overuse, C-ring failure, and/or bushing wear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg.

humeral fractures: a retrospective clinical study and review of the 2005;14(1):65–72.

literature. Injury. 2009;40(6):582–590. 24. Gschwend N, Simmen BR, Matejovsky Z. Late complications in

5. Nolla J, Ring D, Lozano-Calderon S, Jupiter JB. Interposition ar- elbow arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5(2):86 –96.

throplasty of the elbow with hinged external fixation for post- 25. Labek G, Neumann D, Agreiter M, Schuh R, Böhler N. Impact of

traumatic arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(3):459 – 464. implant developers on published outcome and reproducibility of

6. Larson AN, Adams RA, Morrey BF. Revision interposition arthro- cohort-based clinical studies in arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am.

plasty of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(9):1273–1277. 2011;93(suppl 3):55– 61.

JHS 䉬 Vol A, July

You might also like

- 7E1 OperatingManualDocument2 pages7E1 OperatingManualSanjib Nath100% (1)

- Keto Breads - Digital PDFDocument118 pagesKeto Breads - Digital PDFPP043100% (18)

- Philadelphia Distilling Cocktail MenuDocument1 pagePhiladelphia Distilling Cocktail MenuEaterNo ratings yet

- Surgical Treatment of Chronic Elbow Dislocation Allowing For Early Range of Motion: Operative Technique and Clinical ResultsDocument8 pagesSurgical Treatment of Chronic Elbow Dislocation Allowing For Early Range of Motion: Operative Technique and Clinical ResultsLuis Carlos HernandezNo ratings yet

- Stabilization of Distal Humerus Fractures by Precontoured Bi-Condylar Plating in A 90-90 PatternDocument5 pagesStabilization of Distal Humerus Fractures by Precontoured Bi-Condylar Plating in A 90-90 PatternmayNo ratings yet

- Elmoumni2012 Long-Term Functional Outcome Following Intramedullary Nailing ofDocument5 pagesElmoumni2012 Long-Term Functional Outcome Following Intramedullary Nailing ofJian Wei LowNo ratings yet

- 2023 JOT Radiological and Long Term Functional Outcomes of Displaced Distal Clavicle FracturesDocument7 pages2023 JOT Radiological and Long Term Functional Outcomes of Displaced Distal Clavicle FracturesjcmarecauxlNo ratings yet

- Functional Outcome After The Conservative Management of A Fracture of The Distal HumerusDocument7 pagesFunctional Outcome After The Conservative Management of A Fracture of The Distal HumerusnireguiNo ratings yet

- Paper 38Document6 pagesPaper 38Dr Vineet KumarNo ratings yet

- Brief Resume of Intended WorkDocument7 pagesBrief Resume of Intended WorkNavin ChandarNo ratings yet

- A Study of Functional Outcome in Three Column Fixation of Complex Tibial Plateau FracturesDocument5 pagesA Study of Functional Outcome in Three Column Fixation of Complex Tibial Plateau FracturesIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Surgical Management of Proximal Humeral FracturesDocument5 pagesAnalysis of Surgical Management of Proximal Humeral FracturesRhizka djitmauNo ratings yet

- Functiuonal Out5come After Sugical Tratment of Ankle Fracture Using Baird Jackon ScoreDocument4 pagesFunctiuonal Out5come After Sugical Tratment of Ankle Fracture Using Baird Jackon ScoreAxell C MtzNo ratings yet

- Jurnal PfnaDocument10 pagesJurnal PfnaDhea Amalia WibowoNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Jse 2019 10 013Document12 pages10 1016@j Jse 2019 10 013Gustavo BECERRA PERDOMONo ratings yet

- Outcome Assesment of Proximal Fibular Osteotomy in Medial Compartment Knee OsteoarthritisDocument3 pagesOutcome Assesment of Proximal Fibular Osteotomy in Medial Compartment Knee OsteoarthritisPrashant GuptaNo ratings yet

- Intra-Articular Fractures of Distal Humerus Managed With Anatomic Pre-Contoured Plates Via Olecranon Osteotomy ApproachDocument7 pagesIntra-Articular Fractures of Distal Humerus Managed With Anatomic Pre-Contoured Plates Via Olecranon Osteotomy ApproachIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Paper 1 Vinothkumar-1Document5 pagesPaper 1 Vinothkumar-1SK BONE & JOINT CARE DPINo ratings yet

- Operative Treatment of Terrible Triad of TheDocument8 pagesOperative Treatment of Terrible Triad of TheAndrea OsborneNo ratings yet

- Raccourcissement Cubitus - Acta Ortho BelgicaDocument6 pagesRaccourcissement Cubitus - Acta Ortho BelgicaLedouxNo ratings yet

- Case Series of All-Arthroscopic Treatment For Terrible Triad of The Elbow: Indications and Clinical OutcomesDocument10 pagesCase Series of All-Arthroscopic Treatment For Terrible Triad of The Elbow: Indications and Clinical OutcomesdorfynatorNo ratings yet

- Bryan MorreyDocument5 pagesBryan MorreyokisutartoNo ratings yet

- Taylor Spatial Frame Fixation in PatientDocument9 pagesTaylor Spatial Frame Fixation in PatientPriscilla PriscillaNo ratings yet

- A Study On Management of Bothbones Forearm Fractures With Dynamic Compression PlateDocument5 pagesA Study On Management of Bothbones Forearm Fractures With Dynamic Compression PlateIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Closed Intra - Articular Fractures of The Distal End of Humerus Surgically Treated by Trans - Olecranon Approach Using The Chevron OsteotomyDocument4 pagesClosed Intra - Articular Fractures of The Distal End of Humerus Surgically Treated by Trans - Olecranon Approach Using The Chevron OsteotomyIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Tur CicaDocument8 pagesTur CicazubayetarkoNo ratings yet

- Syndesmotic Screw Removed Verusus Retained: A Comparative Functional AnalysisDocument4 pagesSyndesmotic Screw Removed Verusus Retained: A Comparative Functional AnalysisSarath KumarNo ratings yet

- Seguimiento A 5 Años PTGH ReversaDocument7 pagesSeguimiento A 5 Años PTGH Reversamarcelogascon.oNo ratings yet

- Current Treatment Strategies For Patella FracturesDocument8 pagesCurrent Treatment Strategies For Patella FracturesAldrovando JrNo ratings yet

- J Clin Orthop Trauma 2021 20 101480Document8 pagesJ Clin Orthop Trauma 2021 20 101480Lucas SanchezNo ratings yet

- 4 03000605221103974Document13 pages4 03000605221103974Teuku FadhliNo ratings yet

- Anterior Tibial Spine ACL Avulsion Fracture TreateDocument5 pagesAnterior Tibial Spine ACL Avulsion Fracture TreateDyah PurwitaNo ratings yet

- 2004 Stiffness After TKADocument9 pages2004 Stiffness After TKAK49B Y sỹ đa khoaNo ratings yet

- Elbow Hemiarthroplasty and Total Elbow ArthroplastDocument13 pagesElbow Hemiarthroplasty and Total Elbow ArthroplastRafael HaraNo ratings yet

- Two-Stage Bone Lengthening With Reuse of A Single Intramedullary Telescopic Nail in Patients With AchondroplasiaDocument7 pagesTwo-Stage Bone Lengthening With Reuse of A Single Intramedullary Telescopic Nail in Patients With AchondroplasiaLizza Mora RNo ratings yet

- Mallet Finger Suturing TechniqueDocument5 pagesMallet Finger Suturing TechniqueSivaprasath JaganathanNo ratings yet

- 223654-Article Text-546414-1-10-20220403Document6 pages223654-Article Text-546414-1-10-20220403Christopher Freddy Bermeo RiveraNo ratings yet

- Colin 2014Document6 pagesColin 2014Negru TeodorNo ratings yet

- Lberaçao Capsular Posteror CrurgcaDocument7 pagesLberaçao Capsular Posteror CrurgcaEduardo FilhoNo ratings yet

- 2023 TrungluDocument9 pages2023 Trungludr.speleologNo ratings yet

- Intertan Nail Vs PFN ADocument7 pagesIntertan Nail Vs PFN AzubayetarkoNo ratings yet

- Functional Outcome of Operative Management of Humeral Shaft FracturesDocument5 pagesFunctional Outcome of Operative Management of Humeral Shaft FracturesDr JunaidNo ratings yet

- Injury: Jérôme Pierrart, Thierry Bégué, Pierre Mansat, GeecDocument5 pagesInjury: Jérôme Pierrart, Thierry Bégué, Pierre Mansat, GeecJair FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading: Dr. Firdaus RamliDocument22 pagesJournal Reading: Dr. Firdaus RamliBell SwanNo ratings yet

- Injury: Kiran C. Mahabier, Lucas M.M. Vogels, Bas J. Punt, Gert R. Roukema, Peter Patka, Esther M.M. Van LieshoutDocument4 pagesInjury: Kiran C. Mahabier, Lucas M.M. Vogels, Bas J. Punt, Gert R. Roukema, Peter Patka, Esther M.M. Van LieshoutGabriel GolesteanuNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Distal Humerus FracturedDocument10 pagesTreatment of Distal Humerus Fracturedauliya ningsihNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Arthro 2006 07 006Document8 pages10 1016@j Arthro 2006 07 006YoshitaNo ratings yet

- HTTPS://WWW Mendeley Com/reference-Manager/readerDocument6 pagesHTTPS://WWW Mendeley Com/reference-Manager/readerIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Gyaneshwar Tonk-Anatomical and Functional EvaluationDocument11 pagesGyaneshwar Tonk-Anatomical and Functional EvaluationchinmayghaisasNo ratings yet

- Intramedullary Nailing of Distal Metaphyseal.5Document9 pagesIntramedullary Nailing of Distal Metaphyseal.5Joël Clarck EkowongNo ratings yet

- Clinicoradiological and Functional Outcomes of Lisfranc Injuries Managed by Different Treatment Modalities in A Tertiary Care CentreDocument7 pagesClinicoradiological and Functional Outcomes of Lisfranc Injuries Managed by Different Treatment Modalities in A Tertiary Care CentreIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Functional Outcome After Plate Fixation of Midshaft Fracture of ClavicleDocument4 pagesEvaluation of Functional Outcome After Plate Fixation of Midshaft Fracture of ClavicleSonendra SharmaNo ratings yet

- Open Reduction and Internal Fixation in Proximal Humerus Fractures by Proximal Humerus Locking Plate: A Study of 60 CasesDocument6 pagesOpen Reduction and Internal Fixation in Proximal Humerus Fractures by Proximal Humerus Locking Plate: A Study of 60 CasesDian Putri NingsihNo ratings yet

- Acta Orthopaedica Et Traumatologica Turcica: C. Sahin, Y. Oc, N. Ediz, M. Alt Inay, A.H. BayrakDocument6 pagesActa Orthopaedica Et Traumatologica Turcica: C. Sahin, Y. Oc, N. Ediz, M. Alt Inay, A.H. BayrakPoji RazaliNo ratings yet

- TotalHip PDFDocument11 pagesTotalHip PDFLoredanaNovacNo ratings yet

- Complications and Outcomes of The Transfibular Approach For Posterolateral Fractures of The Tibial Plateau PDFDocument19 pagesComplications and Outcomes of The Transfibular Approach For Posterolateral Fractures of The Tibial Plateau PDFSergio Tomas Cortés MoralesNo ratings yet

- Clinical and Radiological Outcomes of Osteoarth 2019 Orthopaedics TraumatoDocument6 pagesClinical and Radiological Outcomes of Osteoarth 2019 Orthopaedics TraumatodrelvNo ratings yet

- MontotenniselbowDocument7 pagesMontotenniselbowPURVA THAKURNo ratings yet

- Lessons Learned: Trapeziectomy and Suture Suspension Arthroplasty For Thumb Carpometacarpal OsteoarthritisDocument7 pagesLessons Learned: Trapeziectomy and Suture Suspension Arthroplasty For Thumb Carpometacarpal Osteoarthritiszakaria ramdaniNo ratings yet

- Hip Dislocation Are Hip Precautions Necessary in Anterior ApproachesDocument6 pagesHip Dislocation Are Hip Precautions Necessary in Anterior Approaches阿欧有怪兽No ratings yet

- Nrutik Paper 22Document6 pagesNrutik Paper 22Nrutik PatelNo ratings yet

- Acetabular Fractures in Older Patients: Assessment and ManagementFrom EverandAcetabular Fractures in Older Patients: Assessment and ManagementTheodore T. MansonNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Williams Basic Nutrition and Diet Therapy 14th Edition Staci NixDocument24 pagesTest Bank For Williams Basic Nutrition and Diet Therapy 14th Edition Staci Nixdavidjonescrjeagtnwp100% (38)

- HFGHFGHDocument5 pagesHFGHFGHcredo99No ratings yet

- 11 JMSCRDocument6 pages11 JMSCRWuppuluri Jayanth Kumar SharmaNo ratings yet

- 38 Fault Codes Tachograph MID 220Document34 pages38 Fault Codes Tachograph MID 220Lazuardhitya oktananda100% (1)

- Experiment #02 To Verify The Theoretical Expression For The Force Exerted by Jet Striking Normally On The Flat Plate (Impact of Jet)Document2 pagesExperiment #02 To Verify The Theoretical Expression For The Force Exerted by Jet Striking Normally On The Flat Plate (Impact of Jet)Mir Masood ShahNo ratings yet

- 9137-AN/898: Airport Services ManualDocument170 pages9137-AN/898: Airport Services ManualAndry NapitupuluNo ratings yet

- Screening Test-EngDocument17 pagesScreening Test-EngJeffrey VallenteNo ratings yet

- Patella TendonitisDocument43 pagesPatella Tendonitisvijkris1985100% (2)

- Torque Values RTJ (B16.5)Document3 pagesTorque Values RTJ (B16.5)ariyamanjulaNo ratings yet

- Voucher (Pre-Paid Booking) : ST - Havel ResidenceDocument2 pagesVoucher (Pre-Paid Booking) : ST - Havel ResidenceAlena KolesnykNo ratings yet

- PUPHA GYOGYSZER UJAK 20161001 v3Document10 pagesPUPHA GYOGYSZER UJAK 20161001 v3rusgal8992No ratings yet

- SR.20.00269 - Testing Engine Lubricants For Heavy Duty Biodeisel Applications AgarwalDocument5 pagesSR.20.00269 - Testing Engine Lubricants For Heavy Duty Biodeisel Applications AgarwalDanielNo ratings yet

- May 2014Document48 pagesMay 2014debtwiggNo ratings yet

- Class Code Description Revision: Numerical Index of Inspection CodesDocument8 pagesClass Code Description Revision: Numerical Index of Inspection CodesRaheleh JavidNo ratings yet

- So Too Either NeitherDocument4 pagesSo Too Either NeitherJos Nguyễn Công DươngNo ratings yet

- Central Venous Pressure Monitoring.: DR Jyothsna Chairperson DR Sunil ChhabriaDocument24 pagesCentral Venous Pressure Monitoring.: DR Jyothsna Chairperson DR Sunil ChhabriaPriyanka MaiyaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 16 Amino Acids, Proteins, and EnzymesDocument92 pagesChapter 16 Amino Acids, Proteins, and EnzymesDennis ZhouNo ratings yet

- Collocation With Common VerbsDocument2 pagesCollocation With Common VerbsKat_23No ratings yet

- MJMHS 0034Document3 pagesMJMHS 0034Alan MarshallNo ratings yet

- CMPC Pulp: Insulation Requirement: Heat Conservation (For Personnel Protection, See Notes 3 & 4) ServiceDocument3 pagesCMPC Pulp: Insulation Requirement: Heat Conservation (For Personnel Protection, See Notes 3 & 4) ServiceCesar Eugenio Sanhueza ValdebenitoNo ratings yet

- Raw Material and Basic Material For Chemical IndustriesDocument20 pagesRaw Material and Basic Material For Chemical Industrieslaila nurul qodryNo ratings yet

- Tipe A - Test Admin Shopee ExpressDocument6 pagesTipe A - Test Admin Shopee ExpressHapsyah MarniNo ratings yet

- Details of Waste PaperDocument3 pagesDetails of Waste PapershivleeaggarwalNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ir. Sutopo Teknik Perminyakan FTTM ITBDocument26 pagesDr. Ir. Sutopo Teknik Perminyakan FTTM ITBKevin Lijaya LukmanNo ratings yet

- JL Components Blower LubricationDocument4 pagesJL Components Blower LubricationMAZENNo ratings yet

- Nonverbal Learning DisabilitiesDocument2 pagesNonverbal Learning DisabilitiesEr_Sakura_8428No ratings yet

- Action Research On Students Misbehavior in ClassDocument4 pagesAction Research On Students Misbehavior in ClassAnalyn Girasol86% (7)