Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Anti-Jewish Policy in Ussr

Anti-Jewish Policy in Ussr

Uploaded by

by chanceOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Anti-Jewish Policy in Ussr

Anti-Jewish Policy in Ussr

Uploaded by

by chanceCopyright:

Available Formats

THE ANTI-JEWISH POLICY OF THE USSR IN THE LAST DECADE OF STALIN'S RULE AND

ITS IMPACT ON THE EAST EUROPEAN COUNTRIES WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO

POLAND

Author(s): BOŻENA SZAYNOK

Source: Russian History , SUMMER-FALL-WINTER 2002 / ÉTÉ-AUTOMNE-HIVER 2002,

Vol. 29, No. 2/4, THE SOVIET GLOBAL IMPACT: 1945-1991 (SUMMER-FALL-WINTER 2002

/ ÉTÉ-AUTOMNE-HIVER 2002), pp. 301-315

Published by: Brill

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24660789

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Brill is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Russian History

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Oct 2022 02:51:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Russian History/Histoire Russe, 29, Nos. 2-4 (Summer-Fall-Winter 2002), 301-15.

BOZENA SZAYNOK (Wroclaw, Poland)

THE ANTI-JEWISH POLICY OF THE USSR IN THE

LAST DECADE OF STALIN'S R ULE AND ITS

IMPACT ON THE EAST EUROPEAN COUNTRIES

WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO POLAND

In the context of our conference the anti-Jewish policy of the USSR is only a

pretext for reflection on aspects of the subordination of the East European states to

the USSR after the Second World War. This policy of the USSR well illustrates

the dependence of Eastern Europe on the Soviet Union after 1945, one of the most

interesting issues in the postwar history of the region. We see here the interaction

between one particular Soviet policy and countries with different historical

experiences, economic structures, attitudes towards Russia and attitudes towards

the Jewish community.

In this issue we can see the origins of certain political activities, their

consequences and their transfer to other countries. Moreover, it is interesting to

observe the behavior of "local communists" in a situation not of their choosing:

from attitudes of total subordination to attempts to preserve some margin of their

own independence. It is also important to observe what was the reaction of

different societies to this policy. In this regard, it should be noted that this policy

did not concern society as whole but only a small part of it. We have to remember

that the East European societies had a variety of attitudes towards Jews, including

anti-Semitic attitudes.

After the Second World War the Jewish issue appeared in the Stalin's policies

in a new context. Internally, it was a significant part of the preparation for a new

purge. Internationally, the Jewish question became an aspect of the question of

Soviet influence in the Middle East. One should stress the circumstances that

made the Jewish issue dominant in Soviet policies in some periods. On the one

hand, we can see reasons that originated in the postwar political situation: the

growth of tension between Western countries, the US and the USSR or the con

flict over influence in the Middle East, where the creation of a Jewish state was

increasingly becoming a reality. On the other hand, anti-Jewish activities had their

basis in the essence of the communist state: looking for enemies to solve political

and other problems. One should emphasize that Jews were better suited to the role

of scapegoats than other nationalities because of their connections with Jewish or

ganizations in Western countries, the US and the Middle East. We also have to re

call that some Soviet policy makers were anti-Semites or were conscious of the

anti-Semitic mood in some groups of Soviet society.

A separate problem of anti-Semitism in Russia after the Second World War is

connected with Stalin. The manifestation of anti-Semitism in his activities had

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Oct 2022 02:51:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

302 Russian History/Histoire Russe

several sources. It is rather difficult to separa

Semitism and what was simple political calcula

alliances, Stalin's policies took into account th

world war. In this situation all "disloyal an

moved from political life. Society also had to

by capitalism was real and that it was only m

new enemies would commence.

The anti-Jewish policy included various elements: the liquidation of Jewish

institutions and organizations, persecution of the Jewish intellectual elite, purges

of some state institutions, reprisals against some Jewish activists. These elements

created a consistently anti-Jewish approach by the Soviet authorities. In every case

these activities were accompanied by virulent anti-Zionist propaganda, which in

its essence was simply anti-Semitic.

There were several fundamental political actions after the Second World War

in the USSR in which the Jewish issue played a significant role. And the policy

connected with them was played out on several levels: from direct persecution of

Jews and the Jewish community as whole to treating the Jewish issue as a pretext

for the achievement of certain political aims.

One of the first activities connected with Soviet Jews undertaken after the war

was the case of Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. Creation of this institution in

1942 was part of the Soviet effort to gain American military assistance. From the

beginning there were questions about the Committee's independence. The war

prevented actions directed against the Committee, but after 1945 they were

quickly initiated. They were also intensified by postwar political situation. Step by

step signals of changes became more apparent. At the end of 1946 the suggestion

appeared that the connections between the Committee and Zionism and world

Jewry were a threat to the USSR. Many accusations were leveled at the

Committee's activists, some of them as serious as charges of espionage or anti

state activity. The Committee was defined as "a center of anti-Soviet propaganda."

The accusations also included the absurd. A good example was the accusation that

leaders of the Committee were attempting to separate the Crimea from the USSR

to create an independent Jewish state.

The liquidation of Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was preceded by the arrest

of some of its members and the murder of its head, Solomon Michoels in January

1948. The Committee was dissolved in November 1948, and four years later the

main trial of its members took place. There were thirteen death sentences

announced at trial but the number of victims of this political action was higher

(according to some estimates there were over then twenty death sentences and

almost a hundred were sent to labor camps). It has been confirmed that Stalin

personally supervised the all activities directed against JAC. Also the

investigation and the trial were carried out under his direction

Various other institutions connected with Jews were liquidated along with the

Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. At the end of 1948, the press organ of the Com

mittee, the Yiddish language newspaper Eynikeyt, was closed down.

The next attack was directed against Jewish intellectuals. A significant part of

the campaign called "the struggle against cosmopolitans" was to destroy the Jew

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Oct 2022 02:51:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Stalin's Post-World War П Anti-Jewish Policy with Special Reference to Poland 303

ish elite. It started in early 1949 as an anti-intellectual action but it gradually took

on an anti-Semitic character. As the Polish writer Andrzej Drawicz wrote in an es

say that "among [the guilty] were some who were more guilty ... a group of

names . . . clearly marked by their race."1 The basis of activities undertaken

against Jewish writers, scientists, and artists was the belief that they expressed

Jewish nationalism in their cultural endeavors. As 1 mentioned above, the anti

Semitic activities were only part of this campaign. Nevertheless the consequences

were significant. Once again anti-Semitism infiltrated political, cultural and social

life and created and reinforced nationalistic attitudes. And some practices used

during the "struggle against cosmopolitans," such as giving Jewish names in

brackets next to Russian names [skobariej], were repeated many times later.

Another Anti-Jewish action was the persecution conducted in the Jewish

Autonomous Region [JAR] in Birobidzhan. The repression of Birobidzhan activ

ists and the liquidation Jewish organizations took place parallel with the prepara

tion of the JAC trial. Except for one paper [Birobidzaner Stern] all Yiddish lan

guage papers and institutions were closed. In the Birobidzhan case as in the "Cri

mean affair" there was the accusation of attempting to separate the region from the

USSR. The purge of JAR leaders preceded trials against some of them. There

were death sentences and long terms in prison. The same accusations were re

peated in almost every case connected with the "Jewish issue": anti-state activity,

espionage and attempts to create a Jewish state in the USSR either in Birobidzhan

or in Crimea. The liquidation of the Jewish elite was only part of Stalin's anti

Semitic campaign. All signs of Jewish culture were destroyed as well. During the

campaign in Birobidzhan even Jewish letters in typewriters became the object of

hatred. The best illustration of this process is the changes introduced into Biro

bidzhan postmark. In the first from 1935 we can see some Yiddish inscriptions. In

1947 the name Birobdzhan still appeared in Yiddish, but in the center of the post

mark the Soviet star with the hammer and sickle appeared as if announcing further

changes. In the postmark from 1955 there are no Yiddish letters, only the Soviet

star and an inscription in Russian.

Anti-Jewish activities affected some state officials as well. Arrests and persecu

tion of the Party's Jewish activists and even people connected with Stalin's anti

Jewish policy constituted further steps in the purge. On July 12, 1951 Viktor Aba

kumov, the Security Minister was arrested. Nicolas Werth wrote in the Black Book

of Communism that the former minister was charged with "preventing the disclo

sure of a criminal group of Jewish nationalists who penetrated into the highest cir

cles of the Security Ministry (MGB)," and "several months later Abakumov him

self was presented as the 'brains' of a Jewish nationalistic plot."2 It is a paradox

that Abakumov was nominated by Stalin to begin the action against the Jewish

Anti-Fascist Committee at the end of 1947. As Vladimir Naumow wrote in his

1. Andrzej Drawicz, A/Kos czyli szkota podloici, in lysenko i kosmopolici (Warszawa: Niezaleina

Oficyna Wydawnicza, 1989), 40-41.

2. Stephane Courtois, Nicolas Werth, Jean Louis Panne, Andrzej Paczkowski, Karel Bartosek, Jean

Louis Margolin, Czarna ksiçga kominizmu. Zbrodnie, terror, przesladowania (Warszawa: Proszynski i

Sk-a., 1999), 237.

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Oct 2022 02:51:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

304 Russian History/Histoire Russe

book: "Instructions were issued that forme

were to be considered members of bourge

investigators were particularly tireless in a

that allegedly existed in the MGB between

zations and the JAC."3

Ihe anti-Jewish campaign occurred in o

book on the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee

members of "the organization of Jewish bo

ample, the Stalin Automobile Plant in Mo

Combine), in the mass media and in public

to prove that a "nationalistic Jewish plot" e

Israel occupied a separate place in the ant

titude of Russia towards the Jewish state c

for Israel, 1947-1948. Just after the war in

East was "not clear." But in May 1947, Gr

establishment of a Jewish state at the Un

policy the Soviet Union was the first to rec

iure and to establish mutual representation

Middle East by this means ended in failure.

ish state did not want to declare solely fo

the article of Il'ia Ehrenburg in Pravda the

Israel became clear. He wrote that Israel has

cording to him the Jewish problem concer

not exist in the Soviet Union. Ehrenburg's

was a signal of a new approach towards the

the Israeli diplomatic representation wrot

Jews of Moscow read this article. And like

between the lines, they understood what it

were being warned to keep away from us!"

recognize this political twist. They openly d

writings on this topic, mainy authors recal

festivities in Moscow in the autumn of 1

part in the celebration. Golda Meir was ent

to a synagogue. She described the event in

cle: "I couldn't talk, or smile, or wave my

without moving, with those thousands of e

Jewish people, Ehrenburg had written. Th

Jews of the USSR! But his warning had f

Soviet Jews towards Israel openly expressed

ened the impression of the disloyalty of thi

3. Stalin's Secret Pogrom: The Postwar Inquisition o

Joshua Rubenstein, and Vladimir P. Naumov (New H

XV.

4. Ibid.

5. Golda Meir, My life (Jerusalem, Tel-Aviv: Stematzky's Agency Ltd., 1975), 203.

6. Ibid., 206.

This content downloaded from

ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Stalin's Post-World War II Anti-Jewish Policy with Special Reference to Poland 305

The winter of 1953 started with a new anti-Jewish and anti-Israeli campaign.

The best known was the announcement of "the discovery of the Kremlin doctors'

plot." On January 13, 1953 Pravda published a state communique "unmasking a

terroristic group of doctors." It was written that the activities of the accused led to

the death of high state officials, among others of Zhdanov and Sherbakov. Among

the charges were spying for Great Britain and the US. The Jewish nationality of

some of the accused reflected the Jewish aspect of the accusations. Also coopera

tion with Joint, the organization of American Jews, was interpreted as espionage.

The article in Pravda initiated a purge and a persecution of the Jews. Ewa Zarzy

cka-Berard mentions in her biography of Il'a Ehrenburg that even in March 1953

Stalin's envoys brought the writer a letter to sign, in which "the undersigned . . .

demand exemplary punishment of their ignominious people, who are responsible

for the crimes of the doctor-murderers, and the punishment should be collective

deportation to the Far East."7

On February 12, 1953 the Soviet Union broke diplomatic relations with Israel.

According to the Soviet government note, this was in response to an assault on the

Soviet embassy in Tel-Aviv. Undoubtedly, the event of February 9 was a pretext

to take action against the Jewish state. Today it is impossible to give a clear inter

pretation of that aspect of Soviet policy. However, we can state that a new purge

was being prepared and the Jewish population would play a part in it, and this ac

tion prevented the intervention of the Jewish state. We cannot today fully recon

struct these events, especially since their main actor - Stalin - died two months

after the publication of the communiqué in Pravda, on March 5, 1953.

As we can see the anti-Jewish actions took place according to various scenar

ios. But their basis and aims were the same. It is worth mentioning some of them:

getting rid of some politicians, maintaining an atmosphere of fear even in closest

circle of Stalin and among East European communists, pursuing influence in the

Middle East, destroying the Jewish community, but also preparing the ground for

a situation in which a war would seem to be the only political solution.

In keeping with the reality of the divided postwar world, the anti-Jewish cam

paign initiated by Stalin spread to the East European countries subordinated to the

Soviet Union after 1945. However, we have to remember that the policy of com

munist states towards the Jews in Hungary, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Roma

nia and Poland differed. On the one hand, there were anti-Jewish activities in line

with the processes inspired by Moscow. Jews were the objects of political actions

precisely because of their nationality. On the other hand, restrictions,- repression,

and persecution affected the Jewish community without reference to its national

ity. During the political, economic and social changes carried out according to the

communist scenario, Jews were treated like other nationalities. It happened, how

ever, that some changes hit the Jewish population harder, e.g., due to their eco

nomic position, in some countries. But it should be noted that these changes had a

communist and not an anti-Jewish character. This happened, for example, in Hun

7. Ewa Zarzycka-Berard, Burzliwe zycie llii Ehrenburga (Warszawa: Iskry. 2002), 256.

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Oct 2022 02:51:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

306 Russian History/Histoire Russe

gary, where the chief victim of radical ec

tion,8 but nationalization was implemented

The policy against the Jews in Eastern Eu

executed in two stages. The first, which beg

erations, lasted until 1948. The next stage -

policy - was inspired by the Kremlin. To u

mode of the changes after 1948 we must ex

towards the Jews in this first period, influen

ent degree by the opposition. The main feat

build the political, economic and religious li

states allowed the establishment of Jewis

crucial place in the policy of those states

For most of the Jews who had survived

stay in the countries they had lived in bef

prevailed that "being simply a Jew" was

Holocaust experience shattered the possibili

first period the governments of Eastern Eu

Palestine. It was connected with Stalin's pol

war we can observe a new position of Stalin

Jewish state. Seeing in the unstable situat

Soviet influence there, Stalin decided to s

lishment a Jewish state in this territory. Dur

in the United Nations, the Soviet Union acc

and then, as noted above, recognized the

(Poland, Czechoslovakia) took a similar pos

ine acceptance 01 a policy 01 reouitaing me jewisn communities in Eastern

Europe after the war and the support for this activity, despite its compulsory char

acter as the official policy of the Eastern bloc, reflected the prevailing belief that

the Jews had the right to their own state. Even anti-Jewish outbursts in some states

did not change the general support for the idea of establishing a Jewish state.

The policy of East European governments towards the Jews in the years 1945

1948 was in line with the position of Moscow, but we have to remember that it did

not run counter to the tendency which originated in the tradition or history of Jew

ish communities in those countries. In my view the same is true of anti-Semitism.

It has been suggested that this phenomenon was inspired by Soviet advisers. There

is not sufficient evidence to support this thesis, although in several cases there is

room for such an explanation. Nevertheless, anti-Semitism resulted also from the

character of relations of a given society with Jews and their experience of living in

that country.

Interesting for our consideration is not only the process of the changes signaled

by Moscow. We should take a closer look at the manner of its implementation and

the reaction of political decision makers. The actions took different forms in each

country, depending on the history of relations with the Jewish population in those

8. Peter Meyer, and Bernard D. Weinryb, Eugene Duschinsky, Nicolas Sylvian, The Jews in Soviet

Satellites (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse Univ. Press, 1953), 453.

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Oct 2022 02:51:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Stalin's Post-World War П Anti-Jewish Policy with Special Reference to Poland 307

countries, the size of the Jewish population, anti-Semitism, the degree of engage

ment in the problem of the Jewish State in the years 1945-1948, the positions held

by Jewish communists, and the readiness of local leaders to carry out a purge.

In the East European countries - Hungary, Romania, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria

and the German Democratic Republic (DDR) - the anti-Jewish policy took differ

ent forms. The realization of this policy in Poland will be examined separately.

The turning point was the liquidation of existing Jewish institutions that had been

allowed to function for several years. The subsidy to the Jewish community was

decreased and the Jewish political scene consolidated. Jewish activists who coop

erated with the Zionist movement or international Jewish organizations suffered

repression.

The next step was the liquidation of foreign representation of Jewish organiza

tions that organized emigration or supported local communities in rebuilding their

lives after the Holocaust. The representatives of Joint and the Jewish Agency in

Czechoslovakia and Hungary were expelled and their offices closed down.

Important in those activities was the change of attitude towards Jewish emigra

tion. In some countries, for example in Hungary, emigration to Israel was prohib

ited, in others drastically limited. Another action was travel restrictions on indi

viduals involved in religious life or the Zionist movement.

An important element was also a new approach towards the Jewish State. The

establishment of Israel was seen as the victory of anti-imperialism - this referred

above all to the fight of the Jews against the British in Palestine. In this way the

significance of Zionism or its contribution to the establishment of the Jewish State

was minimized.

These activities were accompanied by propaganda. The article on Slansky in

Rude Pravo is a good illustration. We find here such statements as "mortal ene

mies of our country . . . corrupt monsters ... a whole gallery of criminals . . .

Trotskyites, Zionists, bourgeois nationalists." An article entitled "Judas" stated:

"Under the red crop of hair in a network of wrinkles the restless eyes of a villain .

. . emotionless ... he starts to speak about his horrible crimes, which the scoun

drel committed, alone doing more evil than hundreds of great villains."9

Another problem was the use of the Jewish issue to carry out political purges in

each country. The pretext for such purges was defined not as a Jewish problem but

portrayed as a "struggle against the Zionism." Already during the trial of Laszlo

Rajk in September 1949 a new approach to Zionism turned up. Christopher An

drew and Oleg Gordijewski wrote in their book about the KGB: . . the an

nouncement of a new, anti-Zionist line at first caused some trouble at Headquar

ters. When colonel Otraszczenko instructed the Middle and Far East personnel at a

meeting in KI10 that Zionism is linked with imperialism, some officers obviously

did not understand what it was about. A deserter from the KGB Ilja Dzhirkvelov

9. Josefa Slanska, "Raport о moim mçzu," Kwarlalnik Polityczny Krytyka, 16 (1983): 190-91.

10. Information Committee - the Soviet Intelligence service was created by combining the foreign

intelligence section of the Ministry of State Security and the Intelligence Administration of the Army

General Staff ( Glavnoe razvedyvatel'noe upravlenie or GRU) in the years 1947-1951. Christopher

Andrew, and Oleg Gordijewski, KGB (Warszawa: Bellona, 1997), 8,9.

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Oct 2022 02:51:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

308 Russian History/Histoire Russe

was one of the first who found the right key

fit into Marxism-Leninism, thus it must be cl

an enemy."11

The policy reached its apogee in Eastern Eu

namely the purge in the Czech Communist Pa

members and their trials. The most significan

Among the accused were the Secretary Gen

Rudolf Slansky; his deputies Bedrich Gemind

eral of the Czech Communist Party in Brno

fairs Vladimir dementis; vice-ministers of For

Hajdu), Foreign Trade (Rudolf Margolius, E

Defense (Bedrich Reicin), National Security

Economic Department in the President's Offic

A Jewish note appeared in all aspects of the

accused, among whom eleven had Jewish ro

tude of the leaders of the investigation left no d

anti-Jewish policy of Stalin. One of the accuse

oirs I Was a Member of the Slansky Gang:

In the beginning of my imprisonment, f

Semitism, I could think that it was a questio

individuals. . . . Now I know that this spiri

radically during the hearings - is a manifest

[party] line. Whenever a new name is men

ately want to know if he is not a Jew.... If t

origin, they look for any pretext to put his o

he or she has nothing to do with the case. Be

ual epithet: "Zionist". They want to include

possible.. .. one has the impression that the

with Jews or at least with a great number of

Jews. . . . whenever I mention a name the

know if her or she is a Jew. But, every time

He was just ordered to write. The term "Z

men and women who had never in their li

12

ism.

Similar attitudes were manifested during a trial that started on November 20

1952: the Jewish origin of several of the accused was pointed out; they were

cused of spying for the Zionist movement and the state of Israel.

The Slansky trial, which ended on November 27, 1952, did not terminate t

purge within the communist parties in Eastern Europe. With the publication

11. Ilya Dzhirkvelov, Secret Servant: My Life with the KGB and the Soviet Elite ( London: Collins,

1987), 250, quoted ibid., 366.

12. Arthur London, Bylem czlonkiem bandy Slanskiego (Warszawa: Niezalezna Oficyn

Wydawnicza, 1987), 95.

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Oct 2022 02:51:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Stalin's Post-World War П Anti-Jewish Policy with Special Reference to Poland 309

Pravda in January 1953 of discovery of the Kremlin "doctors' plot," the "struggle

against Zionism" entered a new stage. Gabor Peter - Chief of the National Secu

rity in Hungary - was arrested and imprisoned "as a Zionist conspirator."13 Simi

lar actions were also undertaken in Romania and Poland. In the DDR persecution

of Jews, members of the SED, took place in the winter of 1952/1953, clearly in

imitation of what had happened in the Soviet Union. Some of the endangered es

caped to the West, but the others were arrested.14 Slansky's case and the trials

prepared in other East European countries were in line with the character of com

munist states, but to fill them with the anti-Semitic content needed a decision from

Stalin.

The policy, composed to a high degree of anti-Semitic actions, was imple

mented in countries where Jews constituted a relatively low percentage of the

whole population. But it has to be remembered that Jewish communist activists

were quite visible in the power structure. There are several reasons for this. One of

them was that during heated discussions about the future of the diaspora at the

turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, part of the Jewish population was

convinced that only Communism was able to solve the Jewish problem. However,

we should remember that Jewish communists in high positions in Communist par

ties were a minority in their community, outcasts from traditional Jewish institu

tions.

One of the aspects of the issue difficult to reconstruct is the activities of Soviet

special forces and their agents in Eastern Europe. Karel Bartosek wrote in The

Black Book of Communism: "Events happening in Moscow at that time - a deep

restructuring of security forces, the arrest of their chief Abakumov in 1951 - led to

the formulation of... a hypothesis. It proposes that in-fighting inside the Soviet

security forces most probably decided both the final selection of victims, who un

til then had cooperated with those forces, and the level of punishment."15 Abaku

mov's successor, Semën Denisovich Ignat'ev, and his deputy M. D. Riumin, were

to be the guarantors of the execution of Stalin's policy.

The implementation of decisions taken in Moscow was carried out by Soviet

advisors in communist countries. The policy was to be executed by functionaries

known for their anti-Semitism: Viktor Komarov, Mikhail Likhachev, Vladimir

Boiarskii, Aleksiej Dymitriewicz Bieszczastnow. In some countries anti-Semitic

sympathies were a criterion for nomination to some positions. It was, e.g., in

Czechoslovakia, where the director of the StB [Czech security forces] responsible

for the pursuit of enemies of the state was Andriej Keppert, a known anti

Semite.16

Interesting is the reaction of communist leaders in East European countries to

the unleashing of a new campaign (at first, anti-Tito and then anti-Zionist). In

Czechoslovakia the future victims of the most famous show trial, for example,

13. Courtois, Werth, Panne, Paczkowski, Bartosek, Margolin, Czarna ksiçga komunizmu, 405.

14. Andrzej Matkiewicz, and KrzysztofRuchniewicz, Pierwszy znak solidarno&ci. Polskie odglosy

powslania ludowego wNRD w 1953 r. (Wroclaw: Arboretum, 1998), 53.

15. Courtois, Werth, Panne, Paczkowski, Bartosek, Margolin, Czarna ksiçga komunizmu, 406.

16. Andrew, and Gordijewski, KGB, 366.

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Oct 2022 02:51:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

310 Russian History/Histoire Russe

Rudolf Slansky, were still in positions of

Czech Rajk." When the victims had bee

supposedly resisted the arrest of Slansky

that Stalin insisted on the imprisonment of

At the beginning of Moscow's anti-Je

Poland. It was a mere handful of the 3,00

of Eastern Europe, Poland had a special p

land for centuries, organizing there one o

cultural Jewish communities in the world. Before the Second World War Jews liv

ing in Poland constituted the largest Jewish community in Europe. The war also

saw the writing of several important chapters in Polish-Jewish history with the

Nazis organizing the Holocaust on Polish territory. The best illustration of what

had happened with Polish Jews during the war is a comparison of the number of

Jews living in Poland before 1939 and after 1945. From a community of almost

3,000,000, only 10 percent survived the Holocaust.

Those who survived were divided into three different tendencies. The first and

also the smallest was the group that decided to rebuild Jewish life in the postwar

Polish reality. The second group preferred assimilation and this was a strong trend

in the postwar Jewish community in Poland. The third and largest group was made

up of Zionists demanding emigration to Palestine from a country that was seen as

a huge Jewish cemetery. All three tendencies were supported by communist deci

sion-makers but at different times and to different degrees.

The communist policy in Poland towards the Jewish problem from 1948 to

1953 consisted of several elements. There were activities directed against Jews in

Poland, their organizations and institutions; fights within the party due to "interna

tional plot of Trotskyite-Tito-Zionists"; relations with the Jewish state and its rep

resentatives in Warsaw; and propaganda accompanying each of these activities.

Signals of a change were visible already in the summer of 1948. A new attitude

toward the Jewish issue showed up not only in the activities of the leadership but

also in the acceptance as the dominant force in the Jewish political scene of Jew

ish communists gathered in the Frakcja Polskiej Partii Robotniczej. The influence

of other parties in the Jewish community was drastically reduced. Jewish socialists

from the Bund and Zionists were suppressed. Bund and Zionist activists were re

moved from Jewish institutions and organizations, and the social and educational

centers run by the parties were closed or nationalized; In early 1949 the Bund,

which had existed in Poland for over fifty years, was dissolved. Zionists from dif

ferent parties were forced to stop their activity at the turn of 1949/1950.

Although these actions were fully in conformity with Moscow's policy, Jewish

communists saw this as an opportunity to realize their own policies, for example,

to restrict the emigration of the Jewish population.

The changes also affected religious life. In 1952 the rabbinate of the Polish

Armed Forces was liquidated, and the representatives of religious Jews were

forced to make servile declarations to the authorities or to protest against Israel's

policies.

As in other East European countries, the representatives of foreign Jewish or

ganizations Joint and the Jewish Agency were forced to end their activities.

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Oct 2022 02:51:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Stalin's Post-World War П Anti-Jewish Policy with Special Reference to Poland 311

The liquidation of the diversified political, social and cultural scene of the Jews

in Poland was only an introduction to more radical actions. The Jewish issue be

came the object of the activity of the security forces. In September 1949 an in

struction of the MBP (Ministry of Public Security) recommended surveillance of

those Zionists who decided to go to Israel and as well as those staying in Poland.

Apart from the Zionists the MBP intended to focus on the Jewish community and

the diplomatic representatives of Israel in Poland.

The next stages of Stalin's anti-Jewish policy also found reflection in the ac

tivities of the Polish security forces. At the beginning of 1952 suggestions of es

pionage on the part of Zionists and the diplomatic representatives of Israel became

more and more frequent.

As in the soviet union, tne campaign against Zionism in roiana oecame an in

strument of political struggle. This is apparent in the purge of the Ministry of For

eign Affairs and of the Polish army.

One of the elements of the Soviet policy towards the Jews was the earlier accu

sation against members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee and activists in Bi

robidzhan of attempting to secede some territories from the Soviet Union. It

seemed that it would not be possible to transfer such absurd accusations to Eastern

Europe. But it turned out that a "Polish version of the Crimea case" was prepared.

The role of Crimea was to be played by Lower Silesia, where almost half of the

Jews who survived the Holocaust lived. Here among Jewish activists was bom the

idea of establishing "an autonomous district" or "Jewish Region"17 in this area.

In the autumn of 1949 the chairman of the local Jewish Committee - Jakub

Egit was accused of "building and organizing a national Jewish settlement."18 In

February 1953 he was arrested and accused of "trying to separate Lower Silesia

from Poland with the help of Joint and other American organizations. He was

supposed to plan to hand over Lower Silesia to the Israeli government and build a

Jewish nationalist state in this region."19 He was also accused of organizing a Jew

ish army in Lower Silesia, which had the support of Israel. This was a reference to

the camp of Haganah volunteers that existed in one of the towns.

The arrest of Egit was supposed to initiate the repression of Jewish activists. It

was only a matter of time before the arrest of members of the Central Jewish

Committee, which after the war was the basic organization of the Jewish popula

tion in Poland and represented it inside and outside the country.20 The scope of the

planned repression of the Jewish community must have been quite large because

the authorities were thinking of establishing a camp for cosmopolitans, Zionists

and other hostile elements.21

As in other East European countries "the struggle against Zionism" was a pre

text for a party purge. According to some documents "Hungarian and Polish func

17. Archiwum Paristwowe we Wroctawiu, zespol: Wojewôdzki Komitet Zydôw na Dolnym Sl^sku,

1, p. 22. Archiwum Diaspory w Tel-Avivie, Diaspora Center. 255.3. II, 24.

18. Jakub Egit, Grand Illusion (Toronto: Lugus production Ltd., 1991), 98-99.

19. Ibid., 108.

20. Ibid, 111.

21. Michat Chçciriski, Poland. Communism. Nationalism. Anti-Semitism (New York: Karz-Cohl

Publishing, 1982), 41-42; Teresa Toranska, Oni (Warszawa: Agencja Omnipress, 1989), 140.

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Oct 2022 02:51:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

312 Russian History/Histoire Russe

tionaries of the party and security insi

mutual interest, to arrest suspects as

bring danger not only for Czechoslov

gary. They pointed out that there is n

the goal is to be reached through inves

quickly as possible."22

Among the Polish comrades mention

high security functionaries - colonels J

ister of Public Security Stanistaw Rad

secretaries of the Central Committeee of PZPR Roman Zambrowski and Jakub

Berman. Among them Jakub Berman was the most likely candidate for a "Polish

Slansky." Apart from him there was the former party secretary Wladyslaw

Gomulka, removed from power in the autumn of 1948. But Jakub Berman was in

greater danger because of his Jewish origins. In the early 1950s he had many func

tions in the party's apparatus, and he also belonged to the highest leadership to

gether with President Boleslaw Bierut and Minister of Economy Hilary Mine. He

was regarded as a "gray eminence" of the political life in that period. But he was

the target of a comment of the Minister of Defence Konstanty Rokossowski: "the

time is over when all Jews were treated as reliable people."23 Berman himself

stated clearly in an interview given in the 1980s: "I became an ideal candidate to

be Slansky and all preparations were aimed at this. Nobody knows how it would

have ended if Stalin had not died. The direct link was the case of the Fields. Bierut

then showed his true character, toughness and loyalty towards me. He did not give

in to pressure and defended me against the accusation to the end, although Stalin

tried to break him."24

It is impossible to reconstruct today all the elements of this diabolical puzzle,

the more so that the witnesses also provide contradictory information, for exam

ple, about Bierut's behavior. However, it is a fact that the trial of a "Polish

Slansky" did not take place. It is difficult to state clearly how the activities of the

security forces would have ended, who was to play the role of the principal ac

cused. One of the high security functionaries involved in the investigation men

tioned that a plan was prepared which included all the necessary elements from

"American intelligence through Jewish organizations, ... the Field case and the

problem of Jewish nationalism."25 The project was rejected by Bierut. The key

person in this plot was too closely tied to Bierut. The behavior of the key decision

makers in this case, and Bierut was certainly among them, was connected with a

sense of their own jeopardy. The Slansky trial had shown that anyone could be

charged.

The situation I have described lacks one element that was especially apparent

in the preparations of the Slansky trial. There is no information about the influ

22. Zatajony dokument. Raport Komisji КС KPCz о procesach politycznych i rehabilitacjach, ed.

by Pawet Hartman (Warszawa: Krytyka, 1984), 24.

23. Tadeusz Marczak, Granica zachodnia w pohkiej polityce zagranicznej w latach 1944-1950

(Wroclaw: Uniwersytet Wroctawski, 1995), 213.

24. Toranska, Oni, 41.

25. Zbigniew Btaiyriski, Mowi Jozef Swiatlo (Londyn: Polska Fundacja Kulturalna, 1986), 146.

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Ocn Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Stalin's Post-World War H Anti-Jewish Policy with Special Reference to Poland 313

ence of Soviet advisers in the Polish reports. They only mention the pressure from

Moscow and Soviet advisers to conduct trials in Poland similar to those that took

place in Hungary and Czechoslovakia, but those who carried out the actions were

officials of the Ministry of Public Security [MBP] in Poland. Among the Polish

functionaries involved in the above mentioned preparations were Radkiewicz,

Romkowski, Swiatlo and Fejgin, the last three of whom had Jewish roots. A ques

tion arises if the people working on the case were aware of the danger, as in the

Soviet Union, that the purges would also swallow those who carried out the

purges? I mentioned before that it is impossible today to reconstruct all the mo

ments of the reality of that time, including the Jewish aspect. Fragmentary mem

oirs and incomplete documents from that period mean we are often confined to the

realms of interpretation and speculation.

The Jewish state played an important role in the activities portrayed here. As

with the Soviet Union, Poland was among the first to recognize Israel de iure.

During the declaration about the future of Palestine at the United Nations, the Pol

ish delegation supported the establishment of a Jewish State. One can find per

sonal engagement in the statements of the Polish representatives, independent of

Moscow's simultaneously executed instructions. In articles on this issue we find a

tone of understanding for Jewish demands. Poland's position was certainly influ

enced to some degree by the common history of Poles and Jews throughout the

centuries. Important also was the fact that the Poles like the Jews historically ex

perienced the lack of their own state.

Diplomatic relations inaugurated with the recognition of Israel in May 1948

and the establishment of Israel's representation in Warsaw in September 1948

were initially correct. But early in 1949 the first signals came of a change of War

saw's attitude towards Israel: the postponement of raising Polish diplomatic repre

sentation in Israel to the rank of an embassy as well as the government's position

on emigration. At the same time the security forces began undercover operations

against representatives of the Jewish State. The best information about the direc

tion of these activities comes from a fragment of a note from the Public Security

Ministry in 1950 dealing with counter-espionage: "There are probably few socie

ties in the world, which by their character, origins, international ties, knowledge of

different countries and languages and connections with those countries, as suitable

to be used by foreign intelligence as the society of the state of Israel."26

Specific operations followed the suggestion to direct activity against the Israeli

Embassy in Warsaw to prove that Arie Kubovy, the ambassador of Israel in Po

land, engaged in espionage. In November 1952 an employee of the Israeli Em

bassy in Warsaw was arrested. During the investigation agents tried to collect evi

dence of espionage activity on the part of members of the Israeli Embassy in Po

land. It should be pointed out that security officers took an interest in Jewish

communists as well. No doubt these activities were a prelude to next the anti

Semitic campaign, initiated officially by Pravda in the communiqué of January

1953.

26. Ibid., 7-9.

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Oct 2022 02:51:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

314 Russian History/Histoire Russe

Apart from the Israeli diplomats in Po

focused on persons maintaining any con

ish state. In 1952 there were arrests of p

Warsaw. People who applied for emigr

ment of Polish citizens of Jewish origin

in a complaint of one employee of th

abused .. . with the epithet 'rotten Jew

raeli representative, that bandit, that t

cent women stay in Poland, only pros

was kicked by the head of the Foreign P

Apart from the atmosphere of unfriend

or actions undertaken by the security f

State also took shape in the diplomati

Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued four

saw, expressing its disapproval of its "e

removal of Arie Kubovy as extraordin

cause his misuse of diplomatic privilege

An anti-Israel campaign in the Polish

formed the backdrop of these activities

to show how they were ordered to "se

the Pattern of the SS" [February 195

strengthen racial hatred in the Middle E

catastrophe" [September 1950]; "The M

Wall Street, Марат dances around Map

people gets worse" [September 1950]; "

Nazism" [October 1950]; "Poverty, spec

tion" [November 1950]; "Kinship of th

temlvr 1QS91 28

As in other East European countries,

fact anti-Semitic campaign was halted a

ion the new leadership quickly manifest

ready in April a communiqué about lega

doctor's issue" was published, and some

found themselves on trial. In July 1953,

Soviet Union were reestablished.

After Stalin's death a new policy towards the Jewish community and Israel was

initiated in Eastern Europe. However, the dynamics of moving away from anti

Jewish activities differed. In Poland the case of the employee of the Israeli diplo

matic representation arrested in November 1952 continued until the beginning of

1955. Although most of the mentioned activities stopped, the consequences of the

anti-Jewish policy in the years 1948-1953 had a significant impact on the societies

that endured it. Several years of intensive actions against the Jewish population

27. Archiwum Ministerstwa Spraw Zagranicznych w Warszawie, 11. 328.18, 28.

28. Bozena Szaynok, Walka z syjonizmem w Polsce, in Komunizm. Ideologia, System, Ludzie, ed.

byTomasz Szarota (Warszawa: Neriton, 2001), 269-70.

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Oct 2022 02:51:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Stalin's Post-World War П Anti-Jewish Policy with Special Reference to Poland 315

and virulent anti-Israeli or anti-Semitic propaganda had a certain long-term im

pact. Despite the thaw and correct relations with communist countries in the sec

ond half of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s, the Jews and the Israeli state

remained suspect in the eyes of the special forces. But for some party decision

makers, e.g., in Poland, the lesson of solving party problems through reference to

anti-Semitism turned out helpful later as well. The repetition of "the struggle

against Zionism" would take place in the Soviet Union and other communist

countries in the summer of 1967; in Poland it would also used to solve a political

crisis a year later, in March 1968.

University of Wroclaw

This content downloaded from

220.241.214.251 on Tue, 11 Oct 2022 02:51:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Little Pilgrim Study GuidePDFDocument18 pagesLittle Pilgrim Study GuidePDFDongkae100% (4)

- Dmitri Trenin - Russia-Polity (2019)Document196 pagesDmitri Trenin - Russia-Polity (2019)Serenas GroupNo ratings yet

- A Specter Haunting Europe: The Myth of Judeo-BolshevismFrom EverandA Specter Haunting Europe: The Myth of Judeo-BolshevismRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Summary of The Book of GenesisDocument4 pagesSummary of The Book of Genesisnoka780% (1)

- A Collection of Quotes From Jewish Periodicals On BolshevismDocument5 pagesA Collection of Quotes From Jewish Periodicals On BolshevismΚαταρα του Χαμ100% (1)

- Levitsky, Sergei, ''The Ideology of NTS (Народно-трудовой союз российских солидаристов) '', 1972.Document8 pagesLevitsky, Sergei, ''The Ideology of NTS (Народно-трудовой союз российских солидаристов) '', 1972.Stefan_Jankovic_83No ratings yet

- He Loved Me - Tom Fettke (SSAA)Document3 pagesHe Loved Me - Tom Fettke (SSAA)Eva Manullang50% (2)

- Zionism and ArabismDocument267 pagesZionism and ArabismEllis Weintraub100% (2)

- High Magick ClassDocument210 pagesHigh Magick ClassJoy Phillip80% (5)

- Jewish Lives under Communism: New PerspectivesFrom EverandJewish Lives under Communism: New PerspectivesKaterina CapkováNo ratings yet

- The Holocaust of Soviet JewryDocument47 pagesThe Holocaust of Soviet JewryLovmysr100% (1)

- Communism Judaica EncyclopediaDocument11 pagesCommunism Judaica EncyclopediaMadrasah Darul-ErkamNo ratings yet

- YIVO - The BundDocument6 pagesYIVO - The BundgbabeufNo ratings yet

- Kevin MacDonald - A Revisionist View of Antisemitism - Esau's TearsDocument6 pagesKevin MacDonald - A Revisionist View of Antisemitism - Esau's TearswhitemaleandproudNo ratings yet

- Denouncing Stalin But Practicing StalinismDocument29 pagesDenouncing Stalin But Practicing StalinismTitiana MiritaNo ratings yet

- Soviet UnionDocument4 pagesSoviet UnionSANG AMNo ratings yet

- Jewish Influence On The Russian RevolutionDocument28 pagesJewish Influence On The Russian RevolutionDean TorresNo ratings yet

- Canadian Slavonic Papers (C. 20, No. 2, Haziran 1978, The Anti-Zionist Campaign in Poland, June-December 1967Document8 pagesCanadian Slavonic Papers (C. 20, No. 2, Haziran 1978, The Anti-Zionist Campaign in Poland, June-December 1967ayazan2006No ratings yet

- History HomeworkDocument11 pagesHistory HomeworkAbood AzharNo ratings yet

- 2-Week 2-BékésDocument38 pages2-Week 2-BékésВалентинка ВершлерNo ratings yet

- Bundism and Zionism in Eastern EuropeDocument286 pagesBundism and Zionism in Eastern EuropeAnca FilipoviciNo ratings yet

- Yasuhiro Matsui - Youth Attitudes Towards Stalin's Revolution and The Stalinist Regime 1929-1941Document15 pagesYasuhiro Matsui - Youth Attitudes Towards Stalin's Revolution and The Stalinist Regime 1929-1941Nadina PanaNo ratings yet

- When Zionist' Meant Jew': Revisiting The 1968 Events in PolandDocument9 pagesWhen Zionist' Meant Jew': Revisiting The 1968 Events in PolandZ Word100% (1)

- Ryan, J. - The Sacralization of Violence: Bolshevik Justifications For Violence and Terror During The Civil WarDocument25 pagesRyan, J. - The Sacralization of Violence: Bolshevik Justifications For Violence and Terror During The Civil WarNiccolò CavagnolaNo ratings yet

- Perun Vs Jesus Christ Communism and EmerDocument13 pagesPerun Vs Jesus Christ Communism and EmerSofia IvanoffNo ratings yet

- 1985 新政治家和每日先驱报中 俄国流亡者的形象Document23 pages1985 新政治家和每日先驱报中 俄国流亡者的形象Idea HistNo ratings yet

- The Long Retreat: Strategies to Reverse the Decline of the LeftFrom EverandThe Long Retreat: Strategies to Reverse the Decline of the LeftNo ratings yet

- Communist Ideology in ChinaDocument10 pagesCommunist Ideology in ChinacharleneNo ratings yet

- Communism - National or InternationalDocument13 pagesCommunism - National or InternationalHugãoNo ratings yet

- In The 1930s Chapter 19 of Alexandr Solzhenitsyn S 200 Years TogetherDocument40 pagesIn The 1930s Chapter 19 of Alexandr Solzhenitsyn S 200 Years TogethercasandraentroyaNo ratings yet

- "Gorbachev's Actions Were The Most Important Factor Leading To The End of The Cold War." DiscussDocument8 pages"Gorbachev's Actions Were The Most Important Factor Leading To The End of The Cold War." DiscussBalnur KorganbekovaNo ratings yet

- In Terms of Foreign Policy Was Khrushchev A Reformer?: March 2016Document11 pagesIn Terms of Foreign Policy Was Khrushchev A Reformer?: March 2016RIshu ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Origins and Development of Soviet Antisemitism An AnalysisDocument25 pagesOrigins and Development of Soviet Antisemitism An AnalysisASK De OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Interventionism in Angola, The Role of IdeologyDocument13 pagesInterventionism in Angola, The Role of IdeologyAlexandre ReisNo ratings yet

- History IA Phoebe SinoSovietSplit FINALDocument10 pagesHistory IA Phoebe SinoSovietSplit FINALphoebeNo ratings yet

- Sheila Fitzpatrick - Celebrating (Or Not) The Russian Revolution.Document26 pagesSheila Fitzpatrick - Celebrating (Or Not) The Russian Revolution.hrundiNo ratings yet

- The Sacralization of Violence BolshevikDocument24 pagesThe Sacralization of Violence BolshevikrepublicadosilencioNo ratings yet

- The Bund in Russia Between Class and NationDocument0 pagesThe Bund in Russia Between Class and NationSylvia NerinaNo ratings yet

- The Use and Abuse of The Holocaust: Historiography and Politics in MoldovaDocument25 pagesThe Use and Abuse of The Holocaust: Historiography and Politics in Moldovai CristianNo ratings yet

- Book 9789004384767 BP000007-previewDocument2 pagesBook 9789004384767 BP000007-previewMoraru Maria SorinaNo ratings yet

- Behavior Unbecoming A Communist - Religious Practice in Soviet MinskDocument32 pagesBehavior Unbecoming A Communist - Religious Practice in Soviet MinskAvitalNo ratings yet

- The Fraud of Soviet Anti-SemitismDocument27 pagesThe Fraud of Soviet Anti-Semitism_the_bridge_No ratings yet

- The Evolution of Sino-Soviet Relations From The 20th Congress of The CPSU To The End of The 1960sDocument9 pagesThe Evolution of Sino-Soviet Relations From The 20th Congress of The CPSU To The End of The 1960sGeorge KatimertzisNo ratings yet

- Soviet Russia-The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia (1943) Vol. IxDocument4 pagesSoviet Russia-The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia (1943) Vol. IxΚαταρα του ΧαμNo ratings yet

- Divide and Conquer The KGB DisinformDocument7 pagesDivide and Conquer The KGB DisinformkabudNo ratings yet

- Asgar Asgarov - Reporting From The Frontlines of The First Cold WarDocument359 pagesAsgar Asgarov - Reporting From The Frontlines of The First Cold War10131No ratings yet

- Communist Readings 2Document7 pagesCommunist Readings 2Ian kang CHOONo ratings yet

- Dissidents Among Dissidents - A5240Document5 pagesDissidents Among Dissidents - A5240Anonymous NupZv2nAGlNo ratings yet

- Controversies of US-USSR Cultural Contac PDFDocument27 pagesControversies of US-USSR Cultural Contac PDFgladio67No ratings yet

- From Repression To Appropriation - Soviet Religious Policy andDocument79 pagesFrom Repression To Appropriation - Soviet Religious Policy andxashesxdianexNo ratings yet

- The Russian Revolution: A Beginner's GuideFrom EverandThe Russian Revolution: A Beginner's GuideRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Holocaust in The East Local Perpetrators and Soviet Responses (Michael David-Fox, Peter Holquist & Alexander M. Martin, 2014)Document281 pagesHolocaust in The East Local Perpetrators and Soviet Responses (Michael David-Fox, Peter Holquist & Alexander M. Martin, 2014)ghalia lounge100% (3)

- The Assassination of KirovDocument24 pagesThe Assassination of KirovbardiaNo ratings yet

- The End of BipolarityDocument9 pagesThe End of BipolarityAayushi JhaNo ratings yet

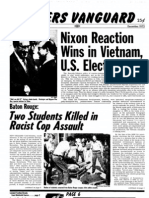

- Workers Vanguard No 14 - December 1972Document12 pagesWorkers Vanguard No 14 - December 1972Workers VanguardNo ratings yet

- Ssoar Annoradea 2011 3 Oltean Considerations - On - The - Situation - ofDocument10 pagesSsoar Annoradea 2011 3 Oltean Considerations - On - The - Situation - ofSiscu Livesin DetroitNo ratings yet

- Ragna Boden The E28098gestapu - Events of 1965 in Indonesia PDFDocument22 pagesRagna Boden The E28098gestapu - Events of 1965 in Indonesia PDFDian Rijal AsyrofNo ratings yet

- Putin's BrainDocument5 pagesPutin's BrainzzankoNo ratings yet

- The Rôle of The Jews in The Russian Revolutionary MovementDocument21 pagesThe Rôle of The Jews in The Russian Revolutionary MovementSam KuruvillaNo ratings yet

- Collapse of Ussr and End of Cold War Collapse of Ussr and End of Cold WarDocument9 pagesCollapse of Ussr and End of Cold War Collapse of Ussr and End of Cold WarHarsheen SidanaNo ratings yet

- New Perspectives On Stalinism Author(s) - Sheila FitzpatrickDocument18 pagesNew Perspectives On Stalinism Author(s) - Sheila FitzpatrickClara FigueiredoNo ratings yet

- The Torah in E-Prime With Interlinear Hebrew in IPADocument1,466 pagesThe Torah in E-Prime With Interlinear Hebrew in IPADavid F Maas100% (3)

- Claude Cohen-Matlofsky - Flavius Josephus, The Man and His Ambitions: A Prosopographic StudyDocument10 pagesClaude Cohen-Matlofsky - Flavius Josephus, The Man and His Ambitions: A Prosopographic StudyJorj98No ratings yet

- The "Staurogram": Correcting ErrorsDocument2 pagesThe "Staurogram": Correcting ErrorsDaniel GhrossNo ratings yet

- Chance. The Cursing of The Temple and The Tearing of The VeilDocument24 pagesChance. The Cursing of The Temple and The Tearing of The VeilJoaquín MestreNo ratings yet

- Formation of The Early Christian Theology of Arithmetic Number Symbolism in The Late Second and Early Third Century PDFDocument480 pagesFormation of The Early Christian Theology of Arithmetic Number Symbolism in The Late Second and Early Third Century PDFjufercrazNo ratings yet

- 2019 - 15 June - Vespers - Saturday of The SoulsDocument8 pages2019 - 15 June - Vespers - Saturday of The SoulsMarguerite PaizisNo ratings yet

- Just A Final Word of The Trinity For NowDocument2 pagesJust A Final Word of The Trinity For NowOng Hui GenNo ratings yet

- Hebrew WordsDocument316 pagesHebrew WordsBud Mann100% (2)

- Chymical Wedding of Christian RosenkreutzDocument4 pagesChymical Wedding of Christian RosenkreutzDayaNo ratings yet

- Prester John Legend - Where Was The "Exotic" Land of This Christian King?Document3 pagesPrester John Legend - Where Was The "Exotic" Land of This Christian King?Dan Costea100% (1)

- Inspired by Living Inspired - Parshat Vaeira (With Help From Rav Akiva Tatz)Document1 pageInspired by Living Inspired - Parshat Vaeira (With Help From Rav Akiva Tatz)TiferetcenterNo ratings yet

- Healing Anointing 4 P.TDocument14 pagesHealing Anointing 4 P.TGoran Jovanović100% (1)

- Angels in America Audience GuideDocument30 pagesAngels in America Audience Guidedurkin44100% (2)

- La Smorfia - Dream Number AnalysisDocument5 pagesLa Smorfia - Dream Number AnalysisDusan Kirovski100% (1)

- Merchant of Venice HWDocument5 pagesMerchant of Venice HWAnonymous mZKmEzK7No ratings yet

- Names of God in ScriptureDocument7 pagesNames of God in ScriptureHeru SungkonoNo ratings yet

- Shoftim - Writing A Sefer TorahDocument7 pagesShoftim - Writing A Sefer TorahSalehSalehNo ratings yet

- Assignment of Cross Cultural UnderstandingDocument5 pagesAssignment of Cross Cultural UnderstandingVindy Virgine GucciNo ratings yet

- Plan de Citire CanonicDocument2 pagesPlan de Citire CanonicdarabafloNo ratings yet

- Colossians CommentaryDocument75 pagesColossians CommentaryLawrence Garner100% (4)

- Tarot and Kabbalistic Sacred Geometry - J.SDocument20 pagesTarot and Kabbalistic Sacred Geometry - J.SBodibodi100% (2)

- HazratDawood KhalifatullahDocument1 pageHazratDawood KhalifatullahAbdul Ajees abdul SalamNo ratings yet

- The Aaronic Priesthood in The Epistle To The HebrewsDocument29 pagesThe Aaronic Priesthood in The Epistle To The HebrewsJoshuaJoshua100% (1)

- Manual For Worship LeadersDocument97 pagesManual For Worship LeadersNessie67% (3)

- Anna's Characterization in Luke 2,36-38. A Case of Conceptual AllusionDocument18 pagesAnna's Characterization in Luke 2,36-38. A Case of Conceptual Allusionelverefur3587100% (1)