Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Take Marinescu by Karl Hans Strobl

Take Marinescu by Karl Hans Strobl

Uploaded by

Joe Bandel0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

54 views21 pagesTake Marinescu by Karl Hans Strobl and translated into English by Joe E. Bandel. This story is in Lemuria Book 2.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

RTF, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentTake Marinescu by Karl Hans Strobl and translated into English by Joe E. Bandel. This story is in Lemuria Book 2.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as RTF, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as rtf, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

54 views21 pagesTake Marinescu by Karl Hans Strobl

Take Marinescu by Karl Hans Strobl

Uploaded by

Joe BandelTake Marinescu by Karl Hans Strobl and translated into English by Joe E. Bandel. This story is in Lemuria Book 2.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as RTF, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as rtf, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 21

Take Marinescu I met Professor Gerngruber under the dragon lanterns at a

Japanese festival. It was in the garden of our ambassador's country house, a

multicolored paper monster gaping at the professor's head made goggle eyes,

spat colors on his bald head, the gypsy music from the dance floor threw itself

whirling into the night. We bumped into each other and he said, "Pardon!" I

knew he was German because I had stepped on his toes and he said,

"Pardon." Incidentally, it turned out later that he was extremely strong, he had

attended all sports schools, the ribs on his chest were made of steel, his

thighs were like bulging car tires, the books had in no way rendered him

incapable of pounding down the stomach walls with messengers. Still, he said

"Pardon" when someone stepped on his toes. You couldn't dissuade him from

that, it was a hereditary defect. He was born in the Passau area. Later we

drank Pilsner together and a couple of glasses of sparkling wine, got a little

friendly, our souls became porous. It turned out that Professor Gerngruber

was in Romania on a scientific assignment. His university had sent him to

collect material for his great work on the gypsy language. This work was to

become the most thorough and learned that had ever been written on the

subject. I later saw a couple of thick books, which Gerngruber called his

sketchy preparatory work, and since I know that boredom and

incomprehensibility are undoubtedly signs of great erudition, after these

rehearsals I only dare to think of the planned monumental work with

reverence. It goes without saying that Gerngruber chose the used the latest

methods and that he was also equipped with gramophones and records to

make phonographic recordings of Gypsy idioms. It was at a time when it was

considered good manners in Romanian society to take an interest in playing

the harp. The harp played the same role at the Romanian court as the flute

did in Sanssouci. As the queen loved to sit at the harp in flowing robes and to

strum the silver strings, the imitation of Carmen Sylva was soon to be seen in

every society, down to the tea-evenings of the better bourgeois salons in

Bucharest. Everywhere the chaste folds of robes flowed on steeply stretched

harp floors, slender fingers trembled sobbing over their nerves and the purest

soul swam ethereally sounding to the stars. They found us in our champagne

corner, we had to go out and listen to Frau von M.'s male well-known

unabashedness denied by sphere sounds. Afterwards I said to Professor

Gerngruber: 'I saw what you were thinking. To forests and to your gypsies.'

'Yes!' he said, surprised, but it hadn't been that hard to guess, because

everything the professor was thinking played in shadow and light on his face.

Since we had shared our joys and sorrows so comradely that evening, and

when we discussed our next plans we discovered that we both intended to

roam the same region in the Romanian forest mountains, it was natural for us

to form an association. Such alliances based on two hours of sparkling wine

and a common escape from the sounds of the harp tend to have no lasting

existence and are not given any particular meaning in life be. The next

morning they are mostly in the shadow of more important matters and only in

later chance encounters does a confidential grin remind you that you once

swore something like eternal friendship to each other. But Professor

Gerngruber was the man to detest such levity and to take oaths after midnight

very seriously. So in the next few days I had to take note of all the details of

the equipment and get some things myself for our future common household

in the wilderness; and I was not allowed to leave Bucharest before the exact

date and time of our meeting had been agreed. A week later, touched by so

much quickly and undeservedly acquired attachment, I was actually at the

small train station in the middle of the wild mountain forest at the appointed

hour. Professor Gerngruber filled in a window of the train and happily clasped

his hands, then he lunged at me and pulled me into a bear hug. He looked

very good, almost trapper-like, his high gaiters reminded one of the brave

leather stocking, and if his strength had corresponded to such a wild

disposition, one would have believed that these gaiters would soon be

trimmed with fringes of human hair. Three men carried the baggage, scientific

and personal, two of them were intended for the professor and me as

servants, the third was Take Marinescu. Although he was actually in a higher

capacity than that of a porter, he dragged more than either of the other two, he

was panting with industriousness, the zeal ran like sweat on his forehead, his

entire strength seemed in unconditional devotion to us and wasted our duties.

He was a handsome young fellow, of slim build, with a real Roman profile. If

he this Profile, then one really had to think of those legionnaires who had once

crushed the insubordinate Transylvania and had gradually been transformed

from soldiers into peasants. But if he turned his face fully towards you, then

the Dacians appeared, the Scythians, Slavs, cousins of the Huns, what do I

know, with the racial characteristics of the eastern peoples, square cheeks,

foreheads laid back, eyes blinking merrily with bent axes. We drove on a

small, narrow-gauge forest railway, on which some boyar turned the jungle

into champagne, theater, and silk petticoats, and meanwhile my friend

instructed me about the division of labor and the order of our day. I was to

hunt and he was to do research. Take Marinescu was caretaker, warden,

confidant in dealing with the local residents, factotum; a Bucharest university

professor had urgently recommended him to take along, this splendid one

splendid fellow who would certainly render us invaluable services. It was

necessary to have an intermediary in order to overcome the shyness of the

forest people, who would not readily understand a European. From the end of

the forest railway we rumbled another day on a farmer's cart along narrow

forest paths. The settlement in which we settled permanently was a lump of

difficult huts crammed into a valley head, as if the world of cleanliness and

civility could not be pushed far enough away from it. In these immense forests

on the southern slopes of the Transylvanian Alps dwelt a degraded and

depraved race, who subsisted on loathsome food in a loathsome manner and

had perished in unspeakable poverty. It must be noted that these forest areas

south of the Hungarian border are among the most unknown parts of Europe

and the maps show the same white spots and the same helpless

schematizing and generalizing of the drawing as the maps of the Albanian

mountains. It is enough for rich gentlemen to know that trees grow there, one

on top of the other, one on top of the other, primeval forests in which you can

let them be felled for a long time before they are completely devastated; and

to know that there is a hunting lodge there where you can spend two weeks in

the autumn chatting with friends. Then those forest people, who because of

their laziness are unsuitable for woodwork, come into consideration as

beaters. That's what the professor told me during our ride in the rattling farm

wagon, and three times he nearly bit his tongue off. I was not a little curious to

see these primitive people, of whom I had an idea, which I later found as an

image of the engravings of an old edition of Cook's world travel recognized.

But in reality I felt the same way with these pictures as ideals of an original

state always do. Instead of being surrounded by a tribe of savages in leaf

aprons or animal skins and shell necklaces, we found ourselves surrounded

on arrival by a mob of tattered men and women. They were just ragged and

greasy, that's all. Countless hands, like monkey hands, much lighter on the

inside than on the outside and just as wrinkled, were stretched out begging. I

believe the gypsies of these forests must come out of the womb with this

beggar's gesture, all reflexes, all impulses of will flow into it, they fall asleep

with it, and if they should be buried seemingly dead and wake up in the grave,

then they first stretch out their hand begging out of. They possess of the

whole culture, of the rich interrelationships of human society nothing but this

single, miserable and shameful gesture. Otherwise there was no sign of

shyness, her nature was rather a cheeky curiosity that groped and groped for

everything, her behavior showed a kind of stupid arrogance, which was

justified by nothing but an unsurpassable excess of dirt and mange. So Tale

Marinescu had less to do to draw them in than to keep them away, and he did

so with such vigor, slamming his pizzle into the pile that we thought there must

be cracked skulls and crushed bones. That was also the only language in

which one could make oneself understood with the people, because

Gerngruber's knowledge of the gypsy languages was not sufficient in this

corner of the world, here they spoke a very strange and highly bizarre

gibberish, made up of a thousand linguistic rubbish. One can imagine the zeal

with which a man whose life was devoted to the exploration of this field went

to work. We hadn't even settled into our tents when he set about capturing this

gibberish with notebook and gramophone as if it were one of the most

blossoming manifestations of the human spirit. We could gauge how culture-

alien our forest people were from the fact that they seemed completely

unfamiliar with the gramophone. They knew nothing of this cultural toy that

can be heard rattling in the tents of the Bedouin sheiks and in the snow huts

of the Eskimo chiefs, but they were also too dull or too haughty to properly

wonder or fear it, like a true primitive people would have done. When their

own voices came out of the funnel, they laughed into it and then listened, as if

they had called into the forest and awaited now expected to hear the echo

stop. Only the village elder, an old man with a patriarch's beard and a nose

like a purple mandrake root, once got angry, felt mocked, and spat grimly into

the funnel. Incidentally, it was amazing how quickly Gerngruber found his way

around the belching, stuttering and rumbling of his gypsies. The pages of his

notebooks were covered with entries, the record collection grew by the day,

and in two weeks he had mastered the basics of grammar and a fairly

substantial vocabulary. Now he was able to communicate with people and

attempt to penetrate more deeply into their world of ideas and feelings. His

method dictated that he should first inquire into their concept of God, but he

soon became convinced, as he sadly assured me, that the question was

evidently far too involved to be dealt with by his still faint ones knowledge to

solve. "In any case, contrary to expectations, you have very subtle religious

ideas," he reported. I ask the elder, "Are you a ghost?" "Yes!" he says. "Do

you know where God lives?" I ask, not expecting him to tell me everywhere

because he's ubiquitous, but to point toward the sky in a child's way. But he

becomes anxious and restless, moves around, doesn't want to say it. I urge

him, promise him tobacco, it makes his eyes shine, but the fear is stronger; I

hold him a packet of tobacco in front of his violet bulbous growth, then greed

becomes the master of fear, he grabs it and murmurs, "in the jar." Immediately

afterwards, however, he covers his arm over his eyes and crawls backwards,

whimpering softly, like a dog that is afraid of being hit. What to think of that?

What are the religious ideas of these people, who are nominally Christians,

but which neither the Church nor the school and which even the state seems

to have forgotten for its army?' I had been hunting from early morning and

returned in the evening, very tired and battered from the march through the

thickets of the jungle, which had torn my clothes with thorny tendrils and

whipped my face. Gerngruber was sitting under an oak tree by a small fire

with some old men. He had the gramophone beside him and the notebook in

his hand. The men had roasted a hedgehog and divided it among themselves,

and now, smacking their lips and digging in their teeth with the hedgehog's

quills, answered the questions of my friend, who seemed to me to be like a

pump that groaned and labored to draw water from a dry and stubborn well .

He saw me approach, looked up in greeting and said, "Oh, your face is all

bloody!" "It's possible," I said, "the forest has taken a toll on me." And I pulled

out a small round pocket mirror, who showed me a bloody tear across my

forehead and one on my cheek. At that moment something unexpected and

strange happened. The men who had just been sitting comfortably around the

fire, munching and munching, dropped the pieces of meat from their dirty

claws and fell flat on their faces, whimpering softly. Gerngruber looked at me

in dismay and shouted something to the men. Without raising his face from

the ground, the eldest made violent, defensive movements with his right arm

and belched out a few words in excitement. "He says," translated the

professor, "you should put away the mirror." My mirror had flung the forest

people to the ground, superstitious fear of the glass repeating our figure had

overwhelmed them and suddenly it had become clear that they had no knew

God but only an idol, the looking glass, that these Christians were fetish

servants in the forests of the Transylvanian Alps. I kept the mirror in my

waistcoat pocket, the professor informed them that the god had withdrawn,

and now they rose slowly, with timid glances at me, still completely

mesmerized by the nearness of the highest thing of their neglected and

wretched souls. No more conversation could be started, they remained

disturbed, and after a while they withdrew to their huts. "You know," I said

afterwards, when we discussed this new observation over a bottle of wine and

put it into the series of our knowledge of these people, »the mirror has always

been an uncanny object for me. He mimics us, he pretends to be a double, he

turns us into a phantom, a ghost, we suddenly find ourselves out of our

depths, a vivid image that is nevertheless only a grimace, an insubstantial

semblance that emerges without a trace from the Glass slides when we take a

step to the side. That actually horrified me a long time ago, and it's only

through getting used to it that we can endure this horrible duplication of our

ego. Well, now that I know that there are people whose God lives in the

looking-glass, it's even scarier for me.' 'There may be a dark feeling about

what you're saying,' the professor said thoughtfully. "Forgive me, I'm not

kidding: the monkeys are very surprised when they find their image in the

mirror and when you turn the glass there is nothing behind it. One level higher

and the fear of the apparition sets in. Then mankind steps into the light of

culture and now the mirror is a thing about which one can read a whole lot of

laws in optics. It has its rules and its place in the world and its phenomena.

One step higher and that old fear of primeval times grows out of our nerves

and our imagination, because we know very well that we don't actually justify

or explain anything with our explanations and our laws. For our gypsies, it is

the incomprehensibleness of these creative powers of glass that frightens

them. Doesn't it in fact have something divine, in which there is always, even

in our religion of love, a residual fear that cannot be suppressed ... is it, as I

said, not really like a creative act of the deity when out of the nothingness of

the clear glass, suddenly an image of man emerges that wasn't there before?

And isn't it a counterpart to death and annihilation, when it is wiped away

again, disappears completely, how human life slips away from the mirror of the

world? Isn't there a deep philosophy in the madness of these people? One

can see that the professor was inclined to endow his gypsies and their ideas

with a significance that made the study of their language all the more

important to him. We spent some time that evening talking about this subject,

and the very next morning we were to be brought back to it. After breakfast

the village elder came and sat down on the floor next to our table and seemed

in a kind of celebratory mood. He was silent for a long time, and as it often

happened that he kept us silent company for a while, we paid no attention to

him at first. I got up to get my gun when suddenly he started to speak. The

worn style of his Otherwise impetuous chattering talk made me curious, I saw

astonishment on the open face of my companion, through all registers up to a

highly amused smile. "You have no idea what he wants," the professor turned

to me, "he asks nothing less than that we give him all the 'god glasses' that we

have. What do you say to that?' Apparently this old gentleman is also the chief

priest of his tribe and considers himself entitled to take care of all the mirrors

he can reach.' I found the desire a bit strong, saying some things in very

strong German , whereupon the old man, who could not understand the lyrics

but the melody, seemed very embarrassed. His wrinkles moved in confusion,

the white beard began to tremble and the purple bulbous growth above it

paled visibly, as if fate had caught his nose. I didn't care about him anymore

shouldered my rifle, whistled at Belisarius and went into the forest. When I got

home in the evening, Gerngruber smiled at me. 'Just imagine, the old man has

been here once more and asked for our mirrors again; I think he fears for his

high-priestly standing if anyone besides himself is in possession of the

glasses of God. Who knows how many shards of glass he has already

collected, in which holy place he keeps them hidden and what mischief they

may serve. He got pretty rude and I had to give him a shout out.” That evening

I was too exhausted to spin a long mirror conversation. After walking ten

hours through impassable mountain forests, the strangest peculiarities of

fellow human beings leave one more indifferent than a piece of cold meat and

the woolen blanket in which to wrap oneself. My sleep was very deep and

black, without a trace of dream colourfulness. A shaking woke me up, it was

morning, the professor had his hand on my shoulder. "Listen," he said, my

shaving mirror is gone. I want to shave and can't find him. Have you catted

him?' How could I have catted the professor's mirror?' I let my beard sprout in

the juiciest growth. 'Then it was stolen! Do you still have your mirror?” I

reached into my waistcoat, reached into my pockets, found a watch, toothpick,

compass and suitcase key, but I looked in vain for the small round mirror, it

had gone with Gerngruber’s shaving mirror to the holy place of the glasses of

God . We looked at each other. "Take Marinescu," we said at the same time. I

have heard about this our highly recommended shop steward, property

manager and So far I haven't found a chance to speak to Warden, because I

thought it more important to first tell a little about the customs and souls of the

forest people among whom we lived, and because it seemed to me that I was

also revealing a little of his nature by saying that these people were talking

about. I hope that I will not be entirely wrong when one learns of the further

course of our adventures. It was indeed the case with Take Marinescu that in

the course of the weeks he had changed more and more from a compliant,

attentive, hasty fellow into a lazy, slovenly, and dirty rope. Was it because the

professor, to whom I had given the supreme command, was too good-natured

to pull the leash tighter on this young man and hang the bread basket higher

in good time, or were his basic instincts in dealing with the degenerate people

overshot the education to become a European – he had himself adept at

nothing but idleness, had proved adept at nothing but gluttony, was reliable at

nothing but lying. We had known for a long time that we were paying for a

secret enemy in him, had long observed that we sometimes lost little things

that we heard jingling in his pockets. When we sent him out to buy groceries

in the next town, he cheated us in the most shameless way. But every such

shopping trip was a journey of four or five days and difficult at that, so that we

preferred to be swindled than to leave the forest for so long. He was on the

best of terms with the gypsies, we knew that he would give them a generous

supply of our supplies and, in his insatiable gluttony, he would take part in

their hedgehog meals, roast lizards and ant soup without shyness or choice. It

was certainly from this dark ground of humanity grown up, felt like family and

had learned the language of the forest almost as quickly as the professor. Our

tolerance had made him bolder and so it happened that he had kidnapped our

mirrors at night, probably on behalf of his friends. His name crossed our

tongues at the same time, but no sooner had it been pronounced than the

professor's German conscience struck and he began to think again. We

considered that our servants were harmless fellows, somewhat narrow-

minded, but with an honesty commanded by unwavering reverence. They

couldn't be expected to take hold of our property, and they were Bulgarians

who had no language community with our gypsies. The fact that Belisarius

hadn't struck was that it couldn't have been the old man or one of his village

gangs. The dog used to lie between my sleeping bag and the professor's at

the tent entrance and would certainly have attacked any suspicious

approaching stranger. It stuck to Take Marinescu, and the professor said it to

his head in the strictest tone he was capable of. Though he was righteously

annoyed that he had just slipped his shaving mirror, the most important piece

of his personal belongings, that tone of utter severity was still buttery soft, and

Take Marinescu denied it with an insolent grin without particularly rousing

himself. My blood boiled, I pushed the professor aside and stepped onto the

board. I don't remember what I said, but it must have been more succinct, like

the professor's reproaches and my pizzle must have waved a very clear beat

in front of the boy's face, because I remember I can still see his eyes, how

they lost their cheeky shine and fear and cowed malice began to smolder in

them. The eyeball was covered with fine red netting, the pupil was edged with

dark, a narrow, thin circlet stretched to the utmost around a black blazing well

of hate. I can't remember what he did to tease me enough to give him a first-

degree slap in the face. It happened. Take Marinescu howled, hid and didn't

come out for a whole day. But if we thought we had intimidated him with the

new robust method, we were to prove wrong. Apparently the gypsies believed

that after the kidnapping of our god glasses we were more vulnerable and less

to fear than before. A part of our strength, in their opinion, had been withdrawn

from us and passed over to them; so theirs grew Desires for other enticing

things, and Take Marinescu was all the more willing to minister to that craving

as he could satisfy his own vengeance in a pleasant way in the process.

Hardly a night went by without a loss, sometimes a piece of laundry was

missing, sometimes an instrument, sometimes some of the food that we had

piled up in our tent to protect it to some extent. And the stolen things

sometimes turned up again here and there, the professor found one of his

shirts on the body of tall, pockmarked Vitru, I fished my brass compass out

from between the withered, dirty breasts of an eighty-year-old old woman.

They carried the treasures stolen from us without fear before our eyes, and

they tolerated being snatched away from them by force without any particular

agitation, because it was obviously part of their legal concept that taking, one

way or another, establishes ownership. Such a Wrestling with the degenerate

people was, of course, shameful and degrading. If the village had been

somewhere in the interior of Africa, I would have considered myself entitled to

use punitive powers and to give us peace of mind with some exemplary

punishments. But we were still in a constitutional state, should we play police,

revolt the whole tribe against us and in the end cause God knows what

diplomatic confusion. The professor said that if it weren't so interesting here,

he would vote to pitch the tents. He told me, for apology and encouragement,

at length about the fabulously peculiar composition of these people's

language, and finally sacrificed Take Marinescu to staying, saying he'd had

enough now and he'd chase him away. 'No,' I said, 'running away isn't

enough. The guy is hiding in the forests and yet continues his craft at night.

He's a master thief. Do you ever notice when he steals from us? It's like he

knows exactly when we fell asleep. How often have we now taken turns

waking up, but at one point or another a slight confusion of sleep must have

come over us. Belisar doesn't answer, at most he waves his hand when he

scents the boy. Once I think I've been keeping an eye on the tent entrance all

night. I think I can swear to you that not a crease moved there and in the

morning my binoculars were gone. You know, he ties a tent line off the stake,

reaches in, fishes something out, and then ties the line back on. No, dear

professor, we can't get rid of him in any other way than by giving him a

reminder that he'll forget to come back. Give me authority, let me act hunter-

like for once." The professor reluctantly agreed, and all day I watched our

brave Take Marinescu walking, swaying his hips provocatively, lying smoking

under a tree and squinting insolently at us, and a pleasant anticipation of

impending satisfaction ran through my eyes Body. In the evening I made my

preparations while the professor was still sitting by the fire. I didn't want to

shake his tender heart, listen to last-minute arguments. Night came, the fire

sank, over the gap in the forest to our heads the sky was embroidered with a

thousand stars. We crawled into our sleeping bags without having talked

about my plan again, which Gerngruber perhaps did not expect to carry out

that night. I myself wanted to keep myself awake, at the risk of having given

up a night in vain, for it wasn't at all agreed that Take Marinescu would make

another night visit tonight. For a long time I fought bravely against sleep, on

my watch I saw the luminous hands move from one button to the other without

anything happening that rewards me for the burning in my eyes and the

painful gasping and tearing away from the pleasant sinking into the flood of

sleep had. I already believed that Take Marinescu had been warned by his

animal instincts and would let this night pass like any other that we had

guarded more closely. It had to be towards morning, in the narrow crack of the

tent entrance and over the back of the sleeping dog suddenly a gray web

hung, this sense of light was suddenly there, maybe I had overslept its

approach or it had just been washed over the threshold of consciousness. At

that moment I heard, without prior knowledge, only that the slightest sound,

the sharp snap of the strong steel springs somewhere behind me. I felt hot,

hunter's joy went to my head, Tale Marinescu was caught, we had him, let him

wriggle for a while, he didn't deserve better. He should call for our help, should

ask us to free him, he should have to make himself small in front of us and

promise to leave and never come back. It gave me a cruel pleasure to

imagine how he was hanging with his hand in the iron, how he clenched his

teeth to keep from screaming and how the pain finally forced the first groan

out of him. Now I was listening with all my inner and outer ears to what was

happening at the trap, but apart from a few faint noises, hardly louder than the

flapping of the wings of stray birds against the tent wall, I could hear nothing.

What superhuman willpower this guy possessed, his hand to let the sharp iron

grind it down for so long without calling us. Eventually I became all aroused by

this anticipation of a moan that wouldn't come. The longer he stayed outside,

the more he got the better of me, every minute weighed more on my soul; was

I still a European, or had I also become one of those savages, with the cruelty

of a beast and the delight in the torment of human bodies? Hesitatingly, pale

light poured into the tent, I couldn't stand it any longer, slid backwards on my

knees to the trapping iron that had snapped shut around Take Marinescu's

hand. I screamed. Between the iron's strong, steely, toothed jaws stuck a

single bloody crooked finger. "What is it?" asked the professor sleepily from

his couch. 'Look!' I said, trembling, 'I've got my trap irons set up, the rapier

irons... they snap into a lock, you can only open them with the key I've got with

me.' 'So what? ' 'Don't you understand... I've put one on each tent band so

that the thief will catch himself if he reaches into it. Take Marinescu has

recovered…” Gerngruber tugged out of the sleeping bag with the same feet.

'There you are, but he got loose. He left a finger, he severed it, silently... he

mutilated himself to stay free... like an animal, like a fox or a rat. The professor

was standing next to me, in his underpants with a red braid tied around his

stomach and his socks, his bald head sitting like a tight-fitting helmet over his

skull. I felt that he didn't agree with me at all, not at all, and that the sight of

that severed finger embarrassed him in the most embarrassing way. Since I

myself was by no means happy with the outcome of my first man-hunt, I

needed someone all the more who could have helped me to understand

things more easily, so that I could have accused myself all the more violently.

But since the professor did not do this, the whole burden of apologizing to

himself was left to me, and I felt the whole story very confused into anger, with

a distinct anger at the companion's lack of friendship. Grumpy and thoughtful,

we set about burying the finger left to us, buried, and we did as children bury a

canary, making a coffin for it out of a tin cigarette box in which it was carefully

laid on cotton wool. For the rest, we decided to keep quiet about the matter.

Take Marinescu himself, of course, had disappeared. On the canvas of the

tent we found some small traces of blood, on a flat stone near the stream a

dark spot, otherwise the forest had swallowed up our companion without a

trace and we assumed that he had left our vicinity. The professor told the

gypsies that we had chased him away on the spot after a violent outburst. But

you could see that they didn't believe us. But that he had by no means left our

vicinity, but was still somewhere in the forest prowling around and stalking us

should be reported to us in a strange way after a few days. As we stepped

outside our tent one rainy morning and, after poking our noses into the humid

air, looking for a dry patch of ground to set up our field chairs, a dead field

mouse caught my eye, perched on the edge of a puddle of rain lay. There

were enough mice in the woods that year that this little corpse could not have

been considered anything special unless something else about it was striking.

"You see, Professor!" I said, "there is a dead mouse with three pieces of wood

stuck in its body." It really was like that, three small ones, pointed at the top

and bottom, protruded from the gray velvet fur pointed pegs, one in the neck,

one in the stomach and one in the buttocks. The Professor stooped to

examine the strangely trimmed corpse more closely, and when he

straightened up again he displayed what seemed to me a most inappropriate

seriousness. 'It's an announcement,' he cleared his throat, 'you know, an

announcement in Gypsy sign language. You know that through such signs the

wandering tribes send each other information about the path, the direction of

the migration and everything worth knowing. Of course, I don't know what this

sign means in particular... In the meantime, we'll have François come and

ask.' Now we both acted as if the matter didn't concern us at all and left us

completely unconcerned. I know, however, that the professor was the same as

I was, namely that at the sight of this mysterious sign we both immediately

thought of Take Marinescu thought and from that moment were no longer

convinced that he had left the forest. François, the village chief and high priest

of the mirror glasses, who God knows how got his name, appeared and was

led in front of the dead mouse. After a moment's contemplation, he shook

himself as if tossing something from his shoulders, and then stretched three

splayed fingers of his left hand toward the staked corpse. When he lifted his

face towards us, I saw a hypocritical sadness above and, beneath it, a little

veiled, hearty gloating. "It's just as I said," the professor translated the expert's

report, "someone is telling us of misfortune and distress." "Anyone? Who

then? Take Marinescu!” 'François doesn't know. The sign doesn't say anything

about it." "Oh, don't you believe everything people say. Can't you see he's just

trying to spook us? They're in league with Take Marinescu. And by the way,

he's gone, has long since left the forest and is now stumbling around the

Bucharest pavement again.' Realizing that I had said something contradictory

with the last two views, I got very angry and chased the old man away with a

grim movement. Incidentally, I firmly resolved to believe that our enemy was

no longer within our reach, and I managed to piece together a number of

reasons why it must really be so and not otherwise. But I couldn't prevent my

nerves from giving in to my good reasons and all sorts of things in the woods

on my hunts Dangerous things painted behind bushes, trees and rocks. It was

really no fun crawling through the jungle with the feeling that a line could

suddenly be thrown around your neck or a stick knife stuck in your neck. In

the end … reason or not … it is not our head that makes our life comfortable

or uncomfortable, but the nerves are our real masters; and if you look closely,

if someone is capable of silently severing a finger caught in a trapping iron

himself, he is probably also capable of other things which are more

embarrassing to others than he is. Why should I deny it: under the

circumstances, I would have preferred it if the professor had said one day that

he was finished and we could pack. And he may have felt the same way, but

as is usual, no one wanted to give the first word, and so on first my poor

Belisarius had to believe in the enemy in the woods. One day I came back

from the thicket, tired and running hot. A blue-black thunderstorm loomed over

the mountains, cloud bellies pushed over grey-green peaks. The birds chirped

in fear of thunderstorms, my skin bled sweat in great drops. When we, I and

Belisarius, passed the spring from which we drew our water supplies, the dog,

thirsty as he was, threw himself on the ground and began to drink greedily. We

had discovered this spring, a quarter of an hour from our tents, and seized it

because we didn't want to drink god knows how polluted water from the

stream used by the gypsies. This stream ran through a small swamp and past

the huts, but here a clear and rather plentiful stream sprang straight up from

the slope through a short pipe into a basin. Belisar was because of that Rand,

both forepaws spread wide as if to embrace the little water, and slurped

greedily with a long, flinging tongue. I patiently waited for him to finish. He

finally got up with a dripping snout, shook himself so that the drops flew,

waved his gratitude at me and trotted on briskly. Then, when he stayed

behind, I paid no further attention to him, and only when I was about a

hundred paces from the camp did I look around for him. He came up behind

me very slowly, slinking, tail and head down and legs giving in strangely, as if

his bones had suddenly softened. He always stopped after five or six steps, I

could see that he was shaking and his head was dangling unsteadily. My

whistling did not hurry him in the least, and his deterioration was so evident

that I could not doubt that he had suddenly fallen gravely ill. I ran up to him

and he just broke his abdomen as if his spine had suddenly been crushed. His

eyes were dull, his lips pulled back from his teeth, and when I tried to put my

hand on his head he snapped blindly at me. A moment later he collapsed in

front too, rolled onto his side, and the muscles were clenched and stretched

with terrible spasms, long waves ran over his whole body. My poor Belisarius

couldn't be helped, I stood in front of the panting, dying animal with a wild

jumble of thoughts in my head. Suddenly one stabbed up glaringly, hit me

almost painfully in the center of consciousness. It threw me around and I ran

furiously to our campsite. The two servants worked at the fire, our meat

simmered in the blackened cauldron, and the water for tea simmered in the

smaller blue pot. I heard two screams, a wild hiss, and smoke billowed out,

searing my face hot. "What are you thinking of?" the professor roared. "Are

you crazy?" With two wild kicks I threw the meat kettle and teapot into the fire,

the two servants knelt by the destroyed embers, in which the pieces of meat

crackled, and with the expression of people who are about to be beheaded

looked up to me The professor held my arm and kept yelling, "Well, what's the

matter?" "Belisarius just died!" I finally said through a small slit in my throat.

Gerngruber didn't grasp the connection, his eyebrows rose to high arches

over the circular eyes. “Belisarius drank from the spring. Our source has been

poisoned.« - It turned out that I was right, we found the soil above the source

pipe churned up and under the covering layer of moss interspersed with a

yellowish powder and in the pipe itself a small yellow ball in a little bag. The

water meant for our enjoyment swept through a poisoned soil and through a

pipe in which death had been planted. On the evening of that day, the

professor said it was really enough and we would do well to retreat. He was

almost done with his work, and if we had selected the cave gypsies, then

nothing would stand in the way of our departure. The cave gypsies, they were

certainly the strangest of the lost people here in the Romanian mountain

forest, and no amount of hardship could deter us from to see and hear them.

We accelerated our preparations for what was at least a three-day excursion

into the unknown, stocked up on food, weapons and instruments. We got a

sufficient number of records from the black box and then we set off with one of

the servants, who carried a knapsack and a gramophone, while the other

stayed at home as the guard of the camp. Desert mountain streams beat foam

against steep rocks, the bridges consisted of two fallen trees side by side and

went over deep chasms without railings. A labyrinth of yellow-grey sandstone

walls surrounded us with the grotesque forms of an enchanted city. On the

crest of a mountain range we walked carefully over a swaying high moor,

which once swallowed our servant up to the knees. On the second day the

hundred meter high clay wall stretched out in front of us, which seemed to

have been cut off smoothly as if by a giant spade. Only when you got closer

did you see the time creases that the flowing water had dug into it and the

human mouse holes at the foot of the enormous waste. A piece of the

primeval world lived there in the mountain, the dirtiest, most miserable early

world of humanity, you thought you were visiting your ancestors, on the

monkey frontier as far as darkness, wetness and dirt of the dwelling was

concerned. In this widely ramified tangle of caves it smelled unspeakably, as if

one were crawling around in the decaying entrails of a gigantic beast. It was

all so far removed from the present, so stone-age and senile-faced, as if the

very foundation of history were shimmering through. It was just astonishing

that a quite respectable breed of people could thrive here, prettier than their

relatives in the surrounding forest villages, slim and sinewy men and above all

women who, up to their twenty or twenty-second year, had their own strangely

provocative beauty. Egyptian and Something Roman seemed mixed in, the

delicately quivering nostrils of Queen Nepto and the forehead, chin and

shoulders of the so-called Sabina in the Roman National Museum. Although

they had grown up directly from the filth, these girls somehow gave the

impression of grace and purity, and only when they were past their early youth

did they succumb to the natural law of their origin and environment, in that

they soon became withered, tired women and premature became sticky, dirt-

staring hags. Under our gaze they squirmed complacently and vainly, let us

see the nakedness of their supple, metallically shining bodies between their

rags, huddled together, giggled and seemed to expect something from us. We

were soon to find out what the girls thought they could get from us.

Gerngruber had already been working with his notebook for an hour and now

loaded the whole one Company in the most spacious cave, the state room or

the underground marketplace of this mole village. Half a hundred people went

into the room, bodies and heads were pressed tightly in the mouths of the

tunnels. Three or four pine shavings burned on the walls, and like in the

troglodyte caves of Auvergne one saw crude red chalk drawings of animals

and men on the smoothed hard clay of the ceiling. Just opposite us, in the

center of the gathering, a group of about twenty young girls had gathered,

nudged each other, laughed and swayed their bodies like large flowers. The

men remained in an Indian-like seriousness, the old women chattered all the

louder, as if they had a special claim to having the big word. All necks craned

as our servant took the gramophone out of its case and adjusted it. It was part

of the professor's method to show his gramophone candidates first a few

records, from which fairy tales, legends, and poems in their own language or a

related language would be snarled at them, in order to then be able to make

them more easily understand what was important to him. Experience had

shown him that he could always find what he needed more quickly in a

congregation than if he had to search for storytellers and singers through an

individual poll. This time, however, before the professor could explain what he

wanted, one of the old women, who didn't seem to be able to wait, sprang

forward and pulled one of the young girls by the arm in front of the horn of the

gramophone. And without any ado, the slender thing began to shed its rags of

clothing, revealing itself to the eyes of the whole village and ours. The

professor seemed to have lost his tongue, he turned to me in the most timid

embarrassment, but what could I say to him, not understanding a word of this

gypsy thing, I shrugged my shoulders and didn't know whether to keep my

eyes on the beautiful body in front of me or should put down. In the meantime,

the professor had composed himself so broadly that he wrestled with the old

woman in question and answer to find the solution. They babbled and burped,

other women chimed in, a chorus soon fought my mate's single voice,

shouting him down, and you could see that their opinions were becoming

more and more divided. After a quarter of an hour of fierce fighting, the

professor turned to me, dripping with sweat. I was extremely excited and

impatient for a clarification. "Do you think," he cried excitedly... "if you think it's

possible, it's outrageous..." 'What is it?' 'They got us for… no: wait. I ask why

the girl undressed. "You must take a picture of her," says the old woman.

"Why should I take a picture?" I say, "I just want to capture your voices, your

fairy tales, stories and songs, I'll take them to Germany to make a book about

them." "You don't want girls like that she asks..." "Buy girls!!" "Yes, my

dear...they think we're traffickers of girls here. Do you understand. Almost

every year, traffickers in girls come here, into this wilderness, into this

culturally untouched desert, to buy fresh goods for the Bucharest market, for

export, I don't know, and now the women are outraged because they are

attracted to us have deceived." They were really disappointed, obviously badly

hurt in the most sacred feelings, angry chatter grew louder and louder; only

the men remained rigid and Indian-like calm, for according to tribal customs

this trade seemed to belong exclusively to women. The young girl in front of

the gramophone horn put on her dirty rags again with a mocking shrug of her

shoulders, her mother continued to rage uncontrollably in front of the

professor's face. It was difficult to carry out our scholarly intentions, and the

professor had to talk a great deal and spend many times the usual gifts of

money to get a few poor speech samples onto his records. Stepping out of the

maze of caves back into the forest, it really was as if we were diving from the

depths of time into the present. I was about to say something immensely

socio-political when I felt my hand gripped and about to turn saw the narrow

face of the girl on my shoulder, who had undressed in front of the

gramophone. Her nose sucked in the air trembling, her lips were soft and

wonderfully curved, she said something that sounded more beautiful than

anything I had ever heard of the gypsy language. "She says," the professor

explained, "she wants to read your palm." A warm stream flowed from her

hand into mine, very gently she bent my crooked fingers and turned the palms

upwards. Then she looked seriously at the writing on her skin for a long time,

and meanwhile I looked with a kind of emotion at that lovingly bowed head

and how a white furrow had drawn through the black hair. Then, without

raising her head, she murmured a few dark words. My eyes asked the

professor. "Hm!" he said evasively, "of course she prophesies something

unpleasant for you, as was to be expected..." "Just say..." "Oh, stupid things...

sickness and death!" I could already feel the smile of superiority on my lips ,

when the girl suddenly spat vigorously into my palm, shrieked shrilly and

maliciously, and ran laughing into the nearest clay hole. There I stood, saliva

ran down my fingers and we both felt like we were on a desert island in our

erudition and honesty. - Whether it was an aftertaste of our defeat at the

hands of the cavemen or a foreboding of future surprises, we returned from

our excursion quite meekly, actually both expecting some sort of disaster to

find. With a sigh of relief we realized that our tents were in the same place,

and we were pleased to hear from the servant who had stayed behind that

nothing unusual had happened during our absence. So actually we could

have been quite reassured, but we still didn't feel that homely comfort that we

otherwise felt so clearly in our spacious tent. It was as if some hostile and

disturbing spirit had moved in, as if something was lying in wait with staring

evil eyes, and I really took it with gratitude that the professor said we were

done and could, if we wanted to, break out tomorrow. "Let's leave tomorrow!"

The professor unpacked his records, I helping him in an effort to bribe fate

with usefulness. We spoke of primitive peoples, slavery, The white slave

trade, the racial enigma of the beautiful people in the clay cave. My palm

secretly burned, as if there had been a mild caustic poison in the girl's saliva.

'You know,' said the professor, 'I've had enough of the woods. I long for my

bookshelves and my desk and wet pavement on which lie the broad lights of

the shop windows. We don't care about originality anymore, we're too involved

in the equal nature of culture... please put these records in the black box.' 'I

understand,' I said, chatting with the Platten bent down to the box in the

shadow of the corner of the tent, "I can appreciate a person like Take

Marinescu aesthetically, of course, aesthetically. But basically such

phenomena are uncomfortable disturbances of balance..." I had opened the

lid and, without looking, put the new records on top of the stack of the others.

"Our energies..." A cool touch on my fingers, a hissing hiss like wind blowing

through a narrow crack, then a sharp pain... I jerked my hand back, a damp

black serpent's body dangling, a triangular scaly head with teeth in mine bury

meat. The professor screamed, lunged at me, I don't know where he suddenly

got the pliers with which he grabbed the snake's head. Then he dipped my

hand in his, cut and burned, poured cognac into me, I saw how the tent was

caught in a whirlwind and spun in circles, and the center of this merry-go-

round was a misshapen swollen hand... Very soon I lost consciousness . The

next morning I awoke from a heavy intoxication, but the professor had saved

me with singeing, brandy, cutting and cognac, otherwise I should have been

dead by that time. Three of the dangerous black vipers had been put in the

plate case, but the vicious beasts were also found in my hunting bag, in the

camera and even in the thermos flask, and the professor had spent half the

night hunting snakes with the servants. He destroyed one brood in each of the

foot ends of our sleeping bags. The prophetic girl was only to be right about

the first part of a prophecy, and the illness didn't last too long either. In ten

days I was able to get the poison under control with no other consequences

than a hole in my right hand, lameness in the fourth and fifth fingers, and

some weakness. We made our way back without delay. A day of rattling

wagons brought me down a bit, and the ride on the wooden railway through

the autumn-colored forest made me shiver in the open box quite

embarrassingly. I was glad when we reached the train station and possession

of a comfortable express train car with soft seats was imminent. While the

professor at the counter arranged the tickets and luggage matters, I looked

out over the humped forest world. The forests ran down the slopes in yellow,

red and brown, and you could see the folds of the lonely valleys better than in

summer. On a patch of blue sky barred by white ridges of cloud stood a

distant bird. The memory of everything that had gone through was so vivid

that, when he suddenly stood before me, I took Take Marinescu for a creature

of my own thoughts. "Hello!" he said with a grin. “You… it's you. What do you

want?' He shuffled his left foot backwards and lifted his hat. 'The gentlemen

continue. I'm going back to Bucharest now.' 'Go to hell!' I said, furious that I

didn't know how to stop this insolence. 'Oh yes!' he laughed, 'but I still have

wages to be had. The gentlemen didn't fire me, so I'll still get paid for... wait...

five weeks and three days, that's...' He held up his hand and began to work

out how much he could still get from us, counting on nine fingers and that

stump whose complement we had buried out in the woods. "What... you ran

away from us, you scoundrel," I fumed, pointing at the stump, "run away from

us and still want reward after all? Think of them Source and remember the

snakes! Oh ... that there is no policeman there, I would hand you over to the

policeman immediately ... but I will call the station manager and he will have to

lock you in the boiler house until a policeman comes ..." "What? … What? …

Mister! What, gendarme?' And he stretched his chest and almost stepped on

my toes in a brutal challenge. His breath washed around my mouth, the pupils

were surrounded by an iris stretched to the point of bursting. Luckily the

professor came up, otherwise I probably would have fought with Take

Marinescu, despite my weakness. Gerngruber put his bear arms around me

like a child and simply put me away. "What do you want?" he asked Take

Marinescu harshly. Much more subdued in front of the professor's upright

figure, but with tenacious impertinence, Take Marinescu presented his

demand. "No," shouted Gerngruber, "no ... no!" he repeated weaker." The boy

immediately took advantage and raised a clamor as if he had been badly

wronged. A ring of men formed around us, all woodworkers from the woods

who had come out for the day of payment. They had drunk heavily and were

waiting for their turn. They are silent when they are sober, these men, and

submissively carry the heaviest loads, but when they have become dangerous

through the liquor, then it can happen that they suddenly remember that the

gentlemen are only made of clay and only have clay a life like her. Take

Marinescu shouted and the men tightened the ring around us, because here

one of theirs had obviously been wronged by the men. "You want to run away

with my wages," the boy shouted, throwing his arms in the air, "just drive

away. After serving them for so long...are these gentlemen? Brethren, I live by

the work of my hands...they are rich gentlemen. They want to get richer by

stealing my wages.” I could almost feel the men growing hostile around us,

becoming a wall, I felt pushed from behind, pressed against Take Marinescu.

The professor could have used his brute strength to make a breach, but he

hung his arms, apparently considering whether a few bruised ribs could be

justified. "Apart! What is it!' someone shouted. The station manager brought

us relief and immediately the circle of men grew a little further. “This person…

this murderer…” I began, shaking with rage. 'No, no,' said the professor, 'do

we have proof? We have no evidence—” “Yeah, what is it?” “They should give

me my wages!” Take Marinescu yelled shrilly, and the woodworkers grumbled

an echo. "He demands his wages... but he just deserted us," I said. "You see,

that's the way it is..." the professor began hesitantly. A signal arm in front of

the station, visible to me between Gerngruber's head and Tale Marinescu,

went up with a clatter. 'The express train is coming! Move!” the exclamations

drowned out the noise of our ball. In one leap, the station manager jumped at

the professor and caught him by the collar of his coat grabbed his coat collar

and yanked him off the rails. We all rolled sideways. "Don't get in!" Howled

Take Marinescu. "Don't let them get on!" howled the workers as they blocked

our way to the rails. 'You should pay! I want you to pay!” “My God, what can I

do?” the stationmaster cried tearfully. 'Leave me alone...I have to catch the

train...it's best if you pay. What can I do? Black, with a wild hint of distance

and danger, the train flew in. The workers standing furthest out staggered a

bit. "Don't let them get in!" Take Marinescu stood in front of us, legs apart and

fists clenched. He had seized power, he controlled the moment, there was no

avoiding it. For a few seconds the professor hesitated; the conductors were

already beginning to slam the doors shut again, someone whistled shrilly.

Then the professor tore out his wallet, let a banknote flutter, Take Marinescu

bent down... We rushed to the train, punched us... Five minutes later we had

caught our breath, and just as we were crossing the gorge on the big iron

bridge, we started to be ashamed of. "It's only been an interesting adventure

so far," said the professor, "but today Take Marinescu really proved his worth."

I looked out at the colorful forests that climbed towards the Hungarian border.

"Yes - I think we shall have a great deal to learn... before we can match this

blow."

You might also like

- Canton Fair - DaniyalDocument73 pagesCanton Fair - DaniyalAreesha FerozNo ratings yet

- Amigurumi 101: Part 1 - Never Give Up: Supply RecommendationsDocument117 pagesAmigurumi 101: Part 1 - Never Give Up: Supply RecommendationsMarie-Colette Robillard83% (6)

- An Image of Africa - Racism in HODDocument4 pagesAn Image of Africa - Racism in HODcultural_mobilityNo ratings yet

- The Lanny Budd Novels Volume One: World's End, Between Two Worlds, and Dragon's TeethFrom EverandThe Lanny Budd Novels Volume One: World's End, Between Two Worlds, and Dragon's TeethRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- The Curse of The Vourdalak - Alexis TolstoyDocument23 pagesThe Curse of The Vourdalak - Alexis TolstoySergio Mota100% (1)

- The Golden Maiden, and other folk tales and fairy stories told in ArmeniaFrom EverandThe Golden Maiden, and other folk tales and fairy stories told in ArmeniaNo ratings yet

- Exploring Gypsiness: Power, Exchange and Interdependence in a Transylvanian VillageFrom EverandExploring Gypsiness: Power, Exchange and Interdependence in a Transylvanian VillageNo ratings yet

- Wine-Dark Seas and Tropic Skies: Reminiscences and a Romance of the South SeasFrom EverandWine-Dark Seas and Tropic Skies: Reminiscences and a Romance of the South SeasNo ratings yet

- Essays in the Study of Folk-Songs (1886)From EverandEssays in the Study of Folk-Songs (1886)No ratings yet

- The Gypsies by Leland, Charles Godfrey, 1824-1903Document171 pagesThe Gypsies by Leland, Charles Godfrey, 1824-1903Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- The Gold Machine: Tracking the Ancestors from Highlands to Coffee ColonyFrom EverandThe Gold Machine: Tracking the Ancestors from Highlands to Coffee ColonyNo ratings yet

- 22939Document191 pages22939aptureincNo ratings yet

- Legends of the North; The Guidman O' Inglismill and The Fairy BrideFrom EverandLegends of the North; The Guidman O' Inglismill and The Fairy BrideNo ratings yet

- I Walked by Night - Being the Life and History of the King of the Norfolk PoachersFrom EverandI Walked by Night - Being the Life and History of the King of the Norfolk PoachersNo ratings yet

- Hauntings by Vernon LeeDocument153 pagesHauntings by Vernon LeeCristin HeartNo ratings yet

- Neruda The VampireDocument8 pagesNeruda The VampireandreNo ratings yet

- Studies And Essays: “the biggest tragedy of life is the utter impossibility to change what you have done”From EverandStudies And Essays: “the biggest tragedy of life is the utter impossibility to change what you have done”No ratings yet

- The Upper Berth: 'We had talked long, and the conversation was beginning to languish''From EverandThe Upper Berth: 'We had talked long, and the conversation was beginning to languish''No ratings yet

- Full Ebook of Eskimo Folk Tales 1St Edition Knud Rasmussen Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesFull Ebook of Eskimo Folk Tales 1St Edition Knud Rasmussen Online PDF All Chaptersatoshmakino0100% (9)

- None but the Nightingale: An Introduction to Chinese LiteratureFrom EverandNone but the Nightingale: An Introduction to Chinese LiteratureNo ratings yet

- Can The Double Murder?: To The Editor of "The Sun."Document6 pagesCan The Double Murder?: To The Editor of "The Sun."20145No ratings yet

- Without DogmaDocument236 pagesWithout Dogmacpi.gab.seducNo ratings yet

- Péter Zilahy - The Last Window Giraffe (Excerpts)Document8 pagesPéter Zilahy - The Last Window Giraffe (Excerpts)Palin WonNo ratings yet

- French and Oriental Love in A Harem by Uchard, MarioDocument166 pagesFrench and Oriental Love in A Harem by Uchard, MarioGutenberg.org100% (1)

- H.P. Lovecraft - The Complete H.P. Lovecraft CollectionDocument2,280 pagesH.P. Lovecraft - The Complete H.P. Lovecraft CollectionMatt Mackey100% (7)

- PDF of Jatuh Cinta Pada Al Qur An Amin M Ariza Full Chapter EbookDocument69 pagesPDF of Jatuh Cinta Pada Al Qur An Amin M Ariza Full Chapter Ebookjulinabarrissoffeef01100% (6)

- Howard Phillips Lovecraft - The Colour Out of SpaceDocument32 pagesHoward Phillips Lovecraft - The Colour Out of SpaceRuixuan DingNo ratings yet

- 7Kh&Duphqri3Urvshu0 Ulp H 5hylhzhgzrunv 6rxufh 7Kh/Rwxv0Djd) Lqh9Ro1R1Ryss 3xeolvkhge/ 6WDEOH85/ $FFHVVHGDocument20 pages7Kh&Duphqri3Urvshu0 Ulp H 5hylhzhgzrunv 6rxufh 7Kh/Rwxv0Djd) Lqh9Ro1R1Ryss 3xeolvkhge/ 6WDEOH85/ $FFHVVHGMel McSweeneyNo ratings yet

- DraculaDocument408 pagesDraculaOrsolya TóthNo ratings yet

- 15 Crazy Useful Things You Did Not Know How To Use ProperlyDocument15 pages15 Crazy Useful Things You Did Not Know How To Use ProperlyShahid AzizNo ratings yet

- Bvlgari Perfume - Google SearchDocument1 pageBvlgari Perfume - Google SearchBhoomika KNo ratings yet

- Lista Perfumes 04-08-22Document1 pageLista Perfumes 04-08-22Juano el matadorNo ratings yet

- MessageDocument11 pagesMessageVictor CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Piscataway H. S. Orchestra: Membership GuideDocument8 pagesPiscataway H. S. Orchestra: Membership GuideDanika CarranzaNo ratings yet

- MONIQUE Corinne, The Little Black Dress An EssayDocument6 pagesMONIQUE Corinne, The Little Black Dress An EssayMar�a Guadalupe Balderas AlfonsoNo ratings yet

- In Text Citation Apa Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesIn Text Citation Apa Literature Reviewafmzslnxmqrjom100% (1)

- Fashion Exhibition CenterDocument195 pagesFashion Exhibition CenterElijah PrinceNo ratings yet

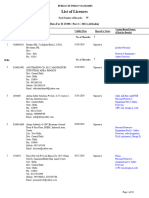

- 1529315308011-List of Licenes Is 15298Document10 pages1529315308011-List of Licenes Is 15298PALLAVI SHARMANo ratings yet

- CBM 321 Report EthicsDocument3 pagesCBM 321 Report Ethicsslow dancerNo ratings yet

- AI Art Generator - AI Image Generator APIDocument1 pageAI Art Generator - AI Image Generator APIlukasbenitezmartinNo ratings yet

- Product Specifications CUBO 2023 Bulacan Smart 10.07.22Document16 pagesProduct Specifications CUBO 2023 Bulacan Smart 10.07.22jose mari TrinidadNo ratings yet

- SillyChicken Readers TheaterDocument4 pagesSillyChicken Readers TheaterJonica Aira Gapuz EamilaoNo ratings yet

- Chicago Manual of StylesDocument2 pagesChicago Manual of Stylesbowdz100% (1)

- Accord Public Disclosure Report 1 January 2016 PDFDocument32 pagesAccord Public Disclosure Report 1 January 2016 PDFresful islamNo ratings yet

- BSBMKG433 T2Document7 pagesBSBMKG433 T2Francis Dave Peralta BitongNo ratings yet

- Fashion Statement: Solutions 2nd Edition IntermediateDocument2 pagesFashion Statement: Solutions 2nd Edition IntermediateLUIS GARCIANo ratings yet

- A Study On The Anglo-Indians of Kerala With Special Reference To MathilakamDocument41 pagesA Study On The Anglo-Indians of Kerala With Special Reference To MathilakamAlfert Stefan DsilvaNo ratings yet

- Crazy Crew TroubleDocument31 pagesCrazy Crew TroubleDaniela Franco100% (4)

- Extracurricular ActivityDocument7 pagesExtracurricular ActivityNastea BicuNo ratings yet

- Afiffi Rika Data Table - The Necklace BY Guy de MaupassantDocument22 pagesAfiffi Rika Data Table - The Necklace BY Guy de MaupassantafiffirikawNo ratings yet

- Gothic Revival NotesDocument4 pagesGothic Revival NotesANURAG GAGANNo ratings yet

- Facility Layout of Nike ShoesDocument17 pagesFacility Layout of Nike ShoesMohit Bhatt100% (13)

- Upcycling v1.00Document2 pagesUpcycling v1.00Sadid HossainNo ratings yet

- W Orkbook Answer Key Unit 8Document1 pageW Orkbook Answer Key Unit 8ingrid jami100% (1)

- LEMBAR SOAL PAS B.INGGRIS 5 SMT 2Document2 pagesLEMBAR SOAL PAS B.INGGRIS 5 SMT 2Dwi Fifi AlfiarumNo ratings yet

- Clothes: Reading and WritingDocument2 pagesClothes: Reading and WritingDAYELIS DUPERLY MADURO RODRIGUEZ100% (1)

- TPM BDL 2023Document19 pagesTPM BDL 2023M Alvin FadhliNo ratings yet