Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hematology (Article) Author State of California Commission On Peace Officer Standards and Training

Hematology (Article) Author State of California Commission On Peace Officer Standards and Training

Uploaded by

Debasish SanyalCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- PDF Sbas and Emis For The General Surgery Frcs Richard Molloy Ebook Full ChapterDocument47 pagesPDF Sbas and Emis For The General Surgery Frcs Richard Molloy Ebook Full Chapterharry.quinn120100% (2)

- Miscellaneous For FinalsDocument30 pagesMiscellaneous For Finalsjames.a.blairNo ratings yet

- Guideline For Hemorrhagic ShockDocument8 pagesGuideline For Hemorrhagic ShockMikaGieJergoLarizaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology Illustrated NotesDocument148 pagesPharmacology Illustrated NotesShikha Khemani91% (11)

- Drug Guideline: Prostacyclin - NebulisedDocument11 pagesDrug Guideline: Prostacyclin - NebulisedJoana MoreiraNo ratings yet

- Dic 1Document6 pagesDic 1Sandra Lusi NovitaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal: Lila Esi Mustika, Amkg NIK: PK2013050Document11 pagesJurnal: Lila Esi Mustika, Amkg NIK: PK2013050lilaNo ratings yet

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation and Implications For Medical-Surgical NursesDocument5 pagesDisseminated Intravascular Coagulation and Implications For Medical-Surgical Nursesancours100% (1)

- Hemostasis 19-3-2012Document11 pagesHemostasis 19-3-2012Mateen ShukriNo ratings yet

- FCPS Dissertation Research Protocol Fresh No Print 2, 15, 16 PageDocument21 pagesFCPS Dissertation Research Protocol Fresh No Print 2, 15, 16 PageDrMd Nurul Hoque Miah100% (5)

- Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) :: A New Look at An Old DisorderDocument6 pagesImmune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) :: A New Look at An Old DisorderAsri Alifa SholehahNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Ischemic Stroke Post Bone FractureDocument11 pagesRisk Factors For Ischemic Stroke Post Bone FractureFerina Mega SilviaNo ratings yet

- Surgery: 1) Preoperative Assessment of HemostasisDocument13 pagesSurgery: 1) Preoperative Assessment of HemostasisIruthayanathar Andru NitharsanNo ratings yet

- Abordaje Niño Que Sangra Hematologia de OskyDocument13 pagesAbordaje Niño Que Sangra Hematologia de OskyivanNo ratings yet

- Original Article: Hyponatremia in Stroke Patients and Its Association With Early MortalityDocument7 pagesOriginal Article: Hyponatremia in Stroke Patients and Its Association With Early Mortalitykholis rizqullahNo ratings yet

- Anemia, Bleeding, and Blood Transfusion in The Intensive Care Unit: Causes, Risks, Costs, and New StrategiesDocument29 pagesAnemia, Bleeding, and Blood Transfusion in The Intensive Care Unit: Causes, Risks, Costs, and New StrategiesDefiita FiirdausNo ratings yet

- Thrombosis Risk Assessment As A Guide To Quality Patient CareDocument9 pagesThrombosis Risk Assessment As A Guide To Quality Patient CareRachel RiosNo ratings yet

- 14 Nisal EtalDocument5 pages14 Nisal EtaleditorijmrhsNo ratings yet

- jhm2616 AmDocument15 pagesjhm2616 Amkishore kumar meelNo ratings yet

- Clinical Cardiac EmergenciesDocument37 pagesClinical Cardiac EmergenciesmigalejandroNo ratings yet

- Myocardial Infarction & AnemiaDocument2 pagesMyocardial Infarction & AnemiaFinka TangelNo ratings yet

- pOSTOPERATIVE HYPOPARATHYROIDISM MANAGEMENTDocument12 pagespOSTOPERATIVE HYPOPARATHYROIDISM MANAGEMENTimran qaziNo ratings yet

- Hemostasis in Oral Surgery PDFDocument7 pagesHemostasis in Oral Surgery PDFBabalNo ratings yet

- Ischemic Stroke: Risk Stratification, Warfarin Teatment and Outcome MeasureDocument6 pagesIschemic Stroke: Risk Stratification, Warfarin Teatment and Outcome MeasureApt. Mulyadi PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- High Risk Patient االمعدلة 2023Document81 pagesHigh Risk Patient االمعدلة 2023MohammedNo ratings yet

- Review Articles: Medical ProgressDocument10 pagesReview Articles: Medical ProgressMiko AkmarozaNo ratings yet

- Rapid Geriatric Assessment of Hip FractureDocument14 pagesRapid Geriatric Assessment of Hip FractureJuliana Moreno LadinoNo ratings yet

- Haemophilia CourseworkDocument4 pagesHaemophilia Courseworkjxaeizhfg100% (2)

- Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic PurpuraDocument11 pagesIdiopathic Thrombocytopenic PurpuraMelDred Cajes BolandoNo ratings yet

- Complications and Management of Patients With Inherited Bleeding Disorders During Dental Extractions - A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesComplications and Management of Patients With Inherited Bleeding Disorders During Dental Extractions - A Systematic Literature ReviewnatalyaNo ratings yet

- Acute Flaccid ParalysisDocument4 pagesAcute Flaccid Paralysismadimadi11No ratings yet

- Patofisiologi Bhs InggrisDocument25 pagesPatofisiologi Bhs InggrisIka VirgiantiniNo ratings yet

- Management of Mild and Moderate Head Injuries in Adults: Dana Turliuc, A. CucuDocument11 pagesManagement of Mild and Moderate Head Injuries in Adults: Dana Turliuc, A. CucuSarrah Kusuma DewiNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology and Treatment of Stroke: Present Status and Future PerspectivesDocument24 pagesPathophysiology and Treatment of Stroke: Present Status and Future Perspectivesdewinta fitriNo ratings yet

- Paro CardiacoDocument14 pagesParo CardiacoDiana MartínezNo ratings yet

- Vte Clinical Update Final - 190207 - 1 - LR FinalDocument6 pagesVte Clinical Update Final - 190207 - 1 - LR FinalSantosh SinghNo ratings yet

- Haematology Dissertation TopicsDocument6 pagesHaematology Dissertation TopicsCollegePapersWritingServiceCanada100% (1)

- Jca TTP CC 2013Document20 pagesJca TTP CC 2013SECOELUNICONo ratings yet

- Pepas de SC Post InfartoDocument24 pagesPepas de SC Post InfartoJosé AñorgaNo ratings yet

- Kuliah Platelets DisordersDocument22 pagesKuliah Platelets DisordersDesi AdiyatiNo ratings yet

- thomas2019 - Peripheral Arterial DiseaseDocument11 pagesthomas2019 - Peripheral Arterial DiseasemutialailaniNo ratings yet

- CĐ 199 2 9Document8 pagesCĐ 199 2 9Hoàng Đức VõNo ratings yet

- New VTE Terbaru FixDocument68 pagesNew VTE Terbaru FixSurya MahardikaNo ratings yet

- SNC Module 1 - Medical Background 0Document42 pagesSNC Module 1 - Medical Background 0shadi alshadafanNo ratings yet

- Management of Patients With Systemic Diseases in Oral SurgeryDocument42 pagesManagement of Patients With Systemic Diseases in Oral SurgeryRichard Starr100% (2)

- Discracia en TX DentalDocument24 pagesDiscracia en TX DentaliraizaNo ratings yet

- S TrokeDocument12 pagesS Trokenersimelda dutyNo ratings yet

- Change Bleeding20clotting20and20platelets20disorders-220205073717Document74 pagesChange Bleeding20clotting20and20platelets20disorders-220205073717Norhan KhaledNo ratings yet

- Venousthromboembolism Andpulmonaryembolism: Strategies For Prevention and ManagementDocument14 pagesVenousthromboembolism Andpulmonaryembolism: Strategies For Prevention and ManagementDamian CojocaruNo ratings yet

- Perioperative AnemiaDocument76 pagesPerioperative AnemiaSimina ÎntunericNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics in HaematologyDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Topics in Haematologygz9fk0td100% (1)

- NoorlifeDocument24 pagesNoorlifeIqra AsimNo ratings yet

- Acute Visual Loss As A First Sign of HyperhomocysteinaemiaDocument3 pagesAcute Visual Loss As A First Sign of HyperhomocysteinaemiaAnGBalNo ratings yet

- Acute Ischemic Stroke UpdateDocument38 pagesAcute Ischemic Stroke Updatenarendra wahyuNo ratings yet

- Noveltreatmentsfor Transientischemicattack AndacuteischemicstrokeDocument16 pagesNoveltreatmentsfor Transientischemicattack AndacuteischemicstrokeDannyNo ratings yet

- TbiguidelineDocument8 pagesTbiguidelinearifbudipraNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Public Health Surveillance of Nonmalignant Blood DisordersDocument8 pagesHHS Public Access: Public Health Surveillance of Nonmalignant Blood DisordersPawan MishraNo ratings yet

- NICE 2010 Guidelines On VTEDocument509 pagesNICE 2010 Guidelines On VTEzaidharbNo ratings yet

- 14 s2.0 S0002870322000953 MainDocument13 pages14 s2.0 S0002870322000953 MainIsmael NavarroNo ratings yet

- Clinical GuidelineDocument12 pagesClinical Guidelineazab00No ratings yet

- Cerebral Venous Thrombosis From UptodateDocument20 pagesCerebral Venous Thrombosis From UptodatewbudyaNo ratings yet

- A Study Assess The Knowledge Regarding of Hemophilia Among Female Students in Jazan UniversityDocument14 pagesA Study Assess The Knowledge Regarding of Hemophilia Among Female Students in Jazan Universityشهد خالدNo ratings yet

- Who Uhc Sds 2019.10 EngDocument50 pagesWho Uhc Sds 2019.10 EngChristian ObandoNo ratings yet

- Predanalitika KoagulacijaDocument10 pagesPredanalitika KoagulacijaAnonymous w4qodCJNo ratings yet

- Sampling Lumbar PunctureDocument6 pagesSampling Lumbar PunctureydtrgnNo ratings yet

- Heparin InjectionDocument2 pagesHeparin InjectiongagandipkSNo ratings yet

- GIbleedingDocument23 pagesGIbleedingReinaldi octaNo ratings yet

- ICU protocol 2015 قصر العيني by mansdocsDocument227 pagesICU protocol 2015 قصر العيني by mansdocsWalaa YousefNo ratings yet

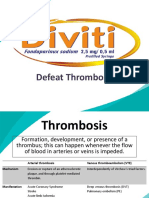

- DivitiDocument36 pagesDivitiMarLeniRNNo ratings yet

- Deep Vein ThrombosisDocument5 pagesDeep Vein ThrombosisSiva Malar GanasenNo ratings yet

- Arrhythmias - Cardiovascular Medicine - MKSAP 17Document17 pagesArrhythmias - Cardiovascular Medicine - MKSAP 17alaaNo ratings yet

- CPM8th Acute Stroke TreatmentDocument22 pagesCPM8th Acute Stroke TreatmentCassie OcampoNo ratings yet

- Anticoag BridgeDocument2 pagesAnticoag BridgeAnonymous ZUaUz1wwNo ratings yet

- 2 Phlebotomy Notes Taken From The Lecture of Sir Antonio Pascua JR RMTDocument5 pages2 Phlebotomy Notes Taken From The Lecture of Sir Antonio Pascua JR RMTRhoda Mae CubillaNo ratings yet

- Deep Vein Thrombosis DissertationDocument7 pagesDeep Vein Thrombosis DissertationPaperWriterUK100% (1)

- BR J Haematol - 2022 - Stanworth - A Guideline For The Haematological Management of Major Haemorrhage A British SocietyDocument14 pagesBR J Haematol - 2022 - Stanworth - A Guideline For The Haematological Management of Major Haemorrhage A British SocietyRicardo Victor PereiraNo ratings yet

- Mixing Studies: Connie H. Miller, PHDDocument2 pagesMixing Studies: Connie H. Miller, PHDYan PetrovNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study On Anticoagulant Activity of Different Parts of Achyranthes AsperaDocument7 pagesComparative Study On Anticoagulant Activity of Different Parts of Achyranthes AsperaSamarendra GhoshNo ratings yet

- An Overview of The MATH+, I-MASK+ and I-RECOVER ProtocolsDocument55 pagesAn Overview of The MATH+, I-MASK+ and I-RECOVER ProtocolsMaung OoNo ratings yet

- Cureus 0013 00000017832Document8 pagesCureus 0013 00000017832raulNo ratings yet

- PRP For Hair Loss Pre Post Instructions 10.18Document2 pagesPRP For Hair Loss Pre Post Instructions 10.18Selvabala904260No ratings yet

- Dade InnovinDocument7 pagesDade InnovinchaiNo ratings yet

- Intoxicación Por ApixabanDocument3 pagesIntoxicación Por ApixabanMariana fotos FotosNo ratings yet

- Serum Vs Plasma: Which Specimen Should You UseDocument48 pagesSerum Vs Plasma: Which Specimen Should You UseTanveerNo ratings yet

- Oral Anticoagulation in Patients With Chronic Liver DiseaseDocument23 pagesOral Anticoagulation in Patients With Chronic Liver DiseaseSophia PapathanasiouNo ratings yet

- BIO CHEM SeminarDocument28 pagesBIO CHEM SeminarBello Taofik InumidunNo ratings yet

- Thyme Increase The Levothyroxine Dose by 30-50%: This Is For Mild To Moderate But For Severe We Will Give Him TriptansDocument66 pagesThyme Increase The Levothyroxine Dose by 30-50%: This Is For Mild To Moderate But For Severe We Will Give Him TriptansOuf'ra AbdulmajidNo ratings yet

- Med-Surg Exam #2 Study GuideDocument33 pagesMed-Surg Exam #2 Study GuideCaitlyn BilbaoNo ratings yet

Hematology (Article) Author State of California Commission On Peace Officer Standards and Training

Hematology (Article) Author State of California Commission On Peace Officer Standards and Training

Uploaded by

Debasish SanyalOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hematology (Article) Author State of California Commission On Peace Officer Standards and Training

Hematology (Article) Author State of California Commission On Peace Officer Standards and Training

Uploaded by

Debasish SanyalCopyright:

Available Formats

HEMATOLOGY1

I. INTRODUCTION

Hematologic abnormalities range from those that are asymptomatic, causing no

significant impairment, to those that are symptomatic, causing significant impairment.

The following hematologic disorders are among the most common and require an

evaluation of the candidate’s ability to perform the functions of a peace officer.

A. Anemia

1) Iron-Deficiency Anemia

2) Thalassemia

B. Bleeding and Clotting Disorders

1) von Willebrand Disease

2) Factor V Leiden

3) Use of anticoagulants

II. IMPLICATIONS FOR JOB PERFORMANCE

Anemia can limit exercise capacity, thereby impacting performance in the following job

situations:

Running in Pursuit of Suspects: speed is important in up to 90% of incidents;

distances may range up to 500 yards.

Pursuit May Be Followed by Physical Altercation: subduing combative

suspects takes an average of three (3) minutes.

Moving Incapacitated Persons: lifting and carrying someone distances of 40+

feet when speed is critical.

These situations require an exercise capacity of up to 12 METS (Adams et al., 2010;

Jette, et al.,1990). They may also result in blunt or penetrating trauma which could lead

to serious complications for those with a bleeding disorder or who require anticoagulants.

1

Authors: Leslie M. Israel, D.O., M.P.H. (MED-TOX) with assistance from R. Leonard Goldberg, M.D.

Specialist Review Panel: Howard A. Liebman, M.D.; Ilene C. Weitz, M.D.

Revised June 2015 V-1

III. MEDICAL EXAMINATION GUIDELINES AND EVALUATION CRITERIA

The evaluation of candidates for hematologic disorders requires a comprehensive history

and physical examination. A candidate with abnormal findings in the history or physical

examination requires a review of relevant medical records to determine the severity of the

hematologic disorder. Further laboratory or diagnostic testing by the candidate’s treating

provider may be required to better define the hematologic disorder, treatment plan,

preventive measures including physical activity limitations, and risk of incapacitation.

Questions regarding a candidate’s aerobic fitness should be assessed with an exercise

test (see Cardiovascular System).

A number of hematologic disorders may be inherited; however, the Genetic Information

Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) of 2008 prohibits not only genetic testing, but also any

inquiries regarding family medical history during candidate and employee evaluations.

To be found acceptable, a candidate should meet the following criteria:

1. No history of severe thrombocytopenia (platelet counts < 5000) or major platelet

dysfunction disorder that is active. A history of previous thrombocytopenia that is

resolved should not put the candidate at risk and therefore should not be a basis for

disqualification. Thrombocytopenia that is transient is not a contraindication.

2. Platelets of <5000 presents a severe risk of bleeding complications. Platelet counts

of <30000 also place the officer at an increased risk for bleeding if injured.

3. Demonstrated history of successful participation in contact sports without recurrent

bleeding complications.

4. Medical record documentation that the candidate possesses adequate knowledge of

his/her disease and has acted responsibly to obtain therapy in a timely manner.

5. Absence of permanent joint damage that would interfere with the safe performance of

duties (see Musculoskeletal System).

6. Absence of advanced infectious disease (i.e., hepatitis B/C, and HIV) which would

impact the performance of duties (see Infectious Diseases).

7. Written acknowledgment from the candidate that he/she is aware of the following

facts and associated personal risks:

The mortality from intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) is 20-50%; those who survive

often have permanent neurological impairment.

Peace officer job demands create an imminent and substantial risk of head

trauma.

Revised June 2015 V-2

To reduce the risk of ICH, it is imperative that the officer obtain factor replacement

or undergo a medical evaluation as soon as possible following any trauma to the

head or face.

Early therapy of head trauma must not be delayed, regardless of the lack of

symptoms, fears of developing serum inhibitors to replacement factors, or cost

considerations.

While effective, early therapy will not eliminate the risk of death from minor head

trauma for those with severe factor deficiencies, or who have serum inhibitors to

replacement factors.

IV. COMMON CLINICAL SYNDROMES

A. ANEMIA

Anemia is a reduction in one or more of the major red blood cell measurements

obtained as part of the complete blood count (CBC). Common types of anemia in

candidates include the following:

1) Iron-Deficiency Anemia (IDA)

IDA is a microcytic anemia and is one of the most prevalent micronutrient

deficiencies, with an estimated occurrence rate in 10-20% of both male and

female athletes (Ahmadi et al., 2010). Marathon running can contribute to iron

loss through hematuria, subclinical gastrointestinal bleeding, sweating,

decreased absorption, and mechanical trauma to the foot (Eichner, 1986;

Newhouse & Clement, 1988). Relatively severe IDA (hemoglobin <10 gm%) will

impair athletic performance (Newhouse & Clement, 1988; Celsing et al., 1986).

Given the potential for IDA to impact performance, the review of medical

documentation must demonstrate a history of successful dietary iron

supplementation to normalize hemoglobin levels and/or the candidate should

perform exercise testing (see Cardiovascular System).

2) Thalassemia

Thalassemia is a microcytic anemia caused by a genetic disorder characterized

by absent or diminished synthesis of either the alpha or beta chains in the

hemoglobin molecule. The prevalence of heterozygotic Thalassemia "minor" is

reported to be common in African, Mediterranean, and Oriental populations.

Clinically, there is usually mild microcytic anemia with hematocrits greater than

32%; these individuals usually have normal cardiovascular capacity.

Homozygous thalassemia ("intermedia" and "major") is a very grave condition

resulting in premature death, poor growth, absent secondary sexual

Revised June 2015 V-3

characteristics, and multiple endocrine deficiencies. It is extremely unlikely that

individuals with this condition would be present in the candidate pool.

B. BLEEDING and CLOTTING DISORDERS

Bleeding and clotting disorders are identified through a comprehensive history and

clinical examination that reveals abnormal bleeding, bruising or clotting (thrombosis).

The diagnosis and severity of the condition, as well as physical activity limitations,

must be confirmed by medical records. If medical records are not available or do not

provide the needed information, evaluation by the candidate’s treating provider or

further evaluation by the candidate’s hematology specialist is necessary.

Intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) from minor head trauma poses the greatest risk of

harm to the individual. In untreated individuals with hemophilia, this occurs following

~10% of head injuries (unselected for severity), and has a mortality rate of 20-50%.

However, ICH can be prevented if clotting factors are administered within six hours of

the head trauma, performed either in the ER or by self-administered infusions (Andes

et al., 1984).

Complications from acute bleeding in someone with a mild bleeding disorder is

unlikely to cause incapacitation or impact performance within the 5-15 minute time

span. Furthermore, prophylactic pharmaceutical measures may be available to

prevent critical bleeds or thrombotic incidents.

A bleeding diathesis secondary to clotting disorders, or the use of anticoagulants

(warfarin), increases the risk of serious injury resulting from physical trauma.

Bleeding into joints, the retroperitoneal area, and intracranial bleeding are of

particular concern.

1) Von Willebrand Disease

Von Willibrand disease (VWD) is the most common bleeding disorder in

humans (Kumar & Carcao, 2013). The risk of bleeding in those with VWD

depends upon the level of functional Von Willibrand factor and on many other

factors that are poorly understood (NHLBI, 2007). The most important tool in

evaluating this condition is a positive response to a history of bleeding. If there

is a positive history of bleeding, the candidate should be questioned further.

Table V-1 provides supplemental questions regarding history of bleeding.

Further evaluation by the candidate’s personal physician and a review of the

candidate’s medical records may be indicated. Treatment of VWD in the United

States varies widely and is often based on local experience and physician

preference (NHLBI, 2007).

Revised June 2015 V-4

Table V-1: Supplemental Questions for Screening Candidates for a Bleeding Disorder

1. Have you ever had prolonged bleeding from trivial wounds lasting more than 15

minutes or recurring spontaneously during the 7 days after the wound?

2. Have you ever had heavy, prolonged, or recurrent bleeding after surgical procedures,

such as a tonsillectomy?

3. Have you ever had bruising with minimal or no apparent trauma, especially if you

could feel a lump under the bruise?

4. Have you ever had a spontaneous nosebleed that required more than 10 minutes to

stop or needed medical attention?

5. Have you ever had heavy, prolonged, or recurrent bleeding after dental extractions

that required medical attention?

6. Have you ever had blood in your stool, unexplained by a specific anatomic lesion

(such as an ulcer in the stomach, or a polyp in the colon, that required medical

attention?

7. Have you ever had anemia requiring treatment or received blood transfusion?

8. For women: Have you ever had heavy menses, characterized by the presence of

clots greater than an inch in diameter and/or the need to change a pad or tampon

more than hourly, or resulting in anemia or low iron level?

Modified from NHLBI 2007

2) Factor V Leiden

Factor V Leiden is the most common cause of venous thromboembolism,

accounting for 40–50% of cases (Bauer et al., 2015). Heterozygotes for the

Factor V Leiden mutation undergoing surgery receive prophylactic

anticoagulation based on the degree of risk associated with the surgery (Bauer,

2015).

3) Use of anticoagulants

Individuals treated with usual doses of warfarin have a 2-4% risk per year of

bleeding episodes requiring transfusion, and a 0.2% risk per year of fatal

hemorrhage. Risk factors for bleeding include both individual-related and

treatment-related factors. Since 2003, the development of new oral

anticoagulants (NOACs) has focused on two types: direct factor Xa inhibitors

and direct factor IIa (thrombin) inhibitors. Despite the advantages of NOACs,

important considerations, such as monitoring and reversal of anticoagulation,

are still unresolved (Hirschl & Kundi, 2014). The new anticoagulants

(dagabatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban or endoxaban) may or may not prolong the

prothrombin time or partial thromboplastin time; therefore, individuals on full

dose remain at risk for bleeding. The risk posed by individuals on prophylactic

doses or low-dose aspirin is minimal. A combination of antiplatelet agents,

such as aspirin combined with clopedigrel (Plavix), can result in significant

bleeding with trauma.

Revised June 2015 V-5

References

Adams, J., Schneider, J., Hubbard, M., McCullough-Shock, T., Cheng, D., Simms, K., &

Strauss, D. (2010). Measurement of functional capacity requirements of police officers to

aid in development of an occupation-specific cardiac rehabilitation training

program. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center), 23(1), 7.

Ahmadi, A., Enayatizadeh, N., Akbarzadeh, M., Asadi, S., & Tabatabaee, S. H. R. (2010).

Iron status in female athletes participating in team ball-sports. Pakistan Journal of

Biological Sciences, 13(2), 93.

Andes, W. A., Wulff, K., & Smith, W. B. (1984). Head trauma in hemophilia: a prospective

study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 144(10), 1981-1983.

Bauer, K., Leung, LLK., & Tirnauer, J.S. (2015). Management of Inherited thrombophilia.

UpToDate Topic 1365 Version 14.0. www.uptodate.com

Brandt-Rauf, P., Borak, J., & Deubner, D. C. (2015). Genetic Screening in the

Workplace. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 57(3), e17-e18.

Celsing, F., Blomstrand, E., Werner, B., Pihlstedt, P. & Ekblom, B. (1986). Effects of iron

deficiency on endurance and muscle enzyme activity in man. Medicine and Science in

Sports and Exercise, 18(2), 156-161.

Eichner, E. R. (1986). The Anemias of Athletes. Physician and Sportsmedicine,14(9),

122-25.

Hirschl, M. & Kundi, M. (2014). New oral anticoagulants in the treatment of acute venous

thromboembolism-a systematic review with indirect comparisons.Vasa, 43(5), 353-364.

Jette, M., Sidney, K., & Blümchen, G. (1990). Metabolic equivalents (METS) in exercise

testing, exercise prescription, and evaluation of functional capacity.Clinical

Cardiology, 13(8), 555-565.

Kumar, R. & Carcao, M. (2013). Inherited abnormalities of coagulation: hemophilia, von

Willebrand disease, and beyond. Pediatric clinics of North America, 60(6), 1419-1441.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2007). The diagnosis, evaluation and

management of von Willebrand disease. NIH publication, (08-5832).

Newhouse, I. J. & Clement, D. B. (1988). Iron status in athletes. Sports Medicine, 5(6),

337-352.

Viteri, F. E. & Torun, B. (1974). Anaemia and physical work capacity. Clinics in

Haematology, 3(3), 609-626.

Revised June 2015 V-6

You might also like

- PDF Sbas and Emis For The General Surgery Frcs Richard Molloy Ebook Full ChapterDocument47 pagesPDF Sbas and Emis For The General Surgery Frcs Richard Molloy Ebook Full Chapterharry.quinn120100% (2)

- Miscellaneous For FinalsDocument30 pagesMiscellaneous For Finalsjames.a.blairNo ratings yet

- Guideline For Hemorrhagic ShockDocument8 pagesGuideline For Hemorrhagic ShockMikaGieJergoLarizaNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology Illustrated NotesDocument148 pagesPharmacology Illustrated NotesShikha Khemani91% (11)

- Drug Guideline: Prostacyclin - NebulisedDocument11 pagesDrug Guideline: Prostacyclin - NebulisedJoana MoreiraNo ratings yet

- Dic 1Document6 pagesDic 1Sandra Lusi NovitaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal: Lila Esi Mustika, Amkg NIK: PK2013050Document11 pagesJurnal: Lila Esi Mustika, Amkg NIK: PK2013050lilaNo ratings yet

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation and Implications For Medical-Surgical NursesDocument5 pagesDisseminated Intravascular Coagulation and Implications For Medical-Surgical Nursesancours100% (1)

- Hemostasis 19-3-2012Document11 pagesHemostasis 19-3-2012Mateen ShukriNo ratings yet

- FCPS Dissertation Research Protocol Fresh No Print 2, 15, 16 PageDocument21 pagesFCPS Dissertation Research Protocol Fresh No Print 2, 15, 16 PageDrMd Nurul Hoque Miah100% (5)

- Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) :: A New Look at An Old DisorderDocument6 pagesImmune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) :: A New Look at An Old DisorderAsri Alifa SholehahNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Ischemic Stroke Post Bone FractureDocument11 pagesRisk Factors For Ischemic Stroke Post Bone FractureFerina Mega SilviaNo ratings yet

- Surgery: 1) Preoperative Assessment of HemostasisDocument13 pagesSurgery: 1) Preoperative Assessment of HemostasisIruthayanathar Andru NitharsanNo ratings yet

- Abordaje Niño Que Sangra Hematologia de OskyDocument13 pagesAbordaje Niño Que Sangra Hematologia de OskyivanNo ratings yet

- Original Article: Hyponatremia in Stroke Patients and Its Association With Early MortalityDocument7 pagesOriginal Article: Hyponatremia in Stroke Patients and Its Association With Early Mortalitykholis rizqullahNo ratings yet

- Anemia, Bleeding, and Blood Transfusion in The Intensive Care Unit: Causes, Risks, Costs, and New StrategiesDocument29 pagesAnemia, Bleeding, and Blood Transfusion in The Intensive Care Unit: Causes, Risks, Costs, and New StrategiesDefiita FiirdausNo ratings yet

- Thrombosis Risk Assessment As A Guide To Quality Patient CareDocument9 pagesThrombosis Risk Assessment As A Guide To Quality Patient CareRachel RiosNo ratings yet

- 14 Nisal EtalDocument5 pages14 Nisal EtaleditorijmrhsNo ratings yet

- jhm2616 AmDocument15 pagesjhm2616 Amkishore kumar meelNo ratings yet

- Clinical Cardiac EmergenciesDocument37 pagesClinical Cardiac EmergenciesmigalejandroNo ratings yet

- Myocardial Infarction & AnemiaDocument2 pagesMyocardial Infarction & AnemiaFinka TangelNo ratings yet

- pOSTOPERATIVE HYPOPARATHYROIDISM MANAGEMENTDocument12 pagespOSTOPERATIVE HYPOPARATHYROIDISM MANAGEMENTimran qaziNo ratings yet

- Hemostasis in Oral Surgery PDFDocument7 pagesHemostasis in Oral Surgery PDFBabalNo ratings yet

- Ischemic Stroke: Risk Stratification, Warfarin Teatment and Outcome MeasureDocument6 pagesIschemic Stroke: Risk Stratification, Warfarin Teatment and Outcome MeasureApt. Mulyadi PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- High Risk Patient االمعدلة 2023Document81 pagesHigh Risk Patient االمعدلة 2023MohammedNo ratings yet

- Review Articles: Medical ProgressDocument10 pagesReview Articles: Medical ProgressMiko AkmarozaNo ratings yet

- Rapid Geriatric Assessment of Hip FractureDocument14 pagesRapid Geriatric Assessment of Hip FractureJuliana Moreno LadinoNo ratings yet

- Haemophilia CourseworkDocument4 pagesHaemophilia Courseworkjxaeizhfg100% (2)

- Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic PurpuraDocument11 pagesIdiopathic Thrombocytopenic PurpuraMelDred Cajes BolandoNo ratings yet

- Complications and Management of Patients With Inherited Bleeding Disorders During Dental Extractions - A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesComplications and Management of Patients With Inherited Bleeding Disorders During Dental Extractions - A Systematic Literature ReviewnatalyaNo ratings yet

- Acute Flaccid ParalysisDocument4 pagesAcute Flaccid Paralysismadimadi11No ratings yet

- Patofisiologi Bhs InggrisDocument25 pagesPatofisiologi Bhs InggrisIka VirgiantiniNo ratings yet

- Management of Mild and Moderate Head Injuries in Adults: Dana Turliuc, A. CucuDocument11 pagesManagement of Mild and Moderate Head Injuries in Adults: Dana Turliuc, A. CucuSarrah Kusuma DewiNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology and Treatment of Stroke: Present Status and Future PerspectivesDocument24 pagesPathophysiology and Treatment of Stroke: Present Status and Future Perspectivesdewinta fitriNo ratings yet

- Paro CardiacoDocument14 pagesParo CardiacoDiana MartínezNo ratings yet

- Vte Clinical Update Final - 190207 - 1 - LR FinalDocument6 pagesVte Clinical Update Final - 190207 - 1 - LR FinalSantosh SinghNo ratings yet

- Haematology Dissertation TopicsDocument6 pagesHaematology Dissertation TopicsCollegePapersWritingServiceCanada100% (1)

- Jca TTP CC 2013Document20 pagesJca TTP CC 2013SECOELUNICONo ratings yet

- Pepas de SC Post InfartoDocument24 pagesPepas de SC Post InfartoJosé AñorgaNo ratings yet

- Kuliah Platelets DisordersDocument22 pagesKuliah Platelets DisordersDesi AdiyatiNo ratings yet

- thomas2019 - Peripheral Arterial DiseaseDocument11 pagesthomas2019 - Peripheral Arterial DiseasemutialailaniNo ratings yet

- CĐ 199 2 9Document8 pagesCĐ 199 2 9Hoàng Đức VõNo ratings yet

- New VTE Terbaru FixDocument68 pagesNew VTE Terbaru FixSurya MahardikaNo ratings yet

- SNC Module 1 - Medical Background 0Document42 pagesSNC Module 1 - Medical Background 0shadi alshadafanNo ratings yet

- Management of Patients With Systemic Diseases in Oral SurgeryDocument42 pagesManagement of Patients With Systemic Diseases in Oral SurgeryRichard Starr100% (2)

- Discracia en TX DentalDocument24 pagesDiscracia en TX DentaliraizaNo ratings yet

- S TrokeDocument12 pagesS Trokenersimelda dutyNo ratings yet

- Change Bleeding20clotting20and20platelets20disorders-220205073717Document74 pagesChange Bleeding20clotting20and20platelets20disorders-220205073717Norhan KhaledNo ratings yet

- Venousthromboembolism Andpulmonaryembolism: Strategies For Prevention and ManagementDocument14 pagesVenousthromboembolism Andpulmonaryembolism: Strategies For Prevention and ManagementDamian CojocaruNo ratings yet

- Perioperative AnemiaDocument76 pagesPerioperative AnemiaSimina ÎntunericNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics in HaematologyDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Topics in Haematologygz9fk0td100% (1)

- NoorlifeDocument24 pagesNoorlifeIqra AsimNo ratings yet

- Acute Visual Loss As A First Sign of HyperhomocysteinaemiaDocument3 pagesAcute Visual Loss As A First Sign of HyperhomocysteinaemiaAnGBalNo ratings yet

- Acute Ischemic Stroke UpdateDocument38 pagesAcute Ischemic Stroke Updatenarendra wahyuNo ratings yet

- Noveltreatmentsfor Transientischemicattack AndacuteischemicstrokeDocument16 pagesNoveltreatmentsfor Transientischemicattack AndacuteischemicstrokeDannyNo ratings yet

- TbiguidelineDocument8 pagesTbiguidelinearifbudipraNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Public Health Surveillance of Nonmalignant Blood DisordersDocument8 pagesHHS Public Access: Public Health Surveillance of Nonmalignant Blood DisordersPawan MishraNo ratings yet

- NICE 2010 Guidelines On VTEDocument509 pagesNICE 2010 Guidelines On VTEzaidharbNo ratings yet

- 14 s2.0 S0002870322000953 MainDocument13 pages14 s2.0 S0002870322000953 MainIsmael NavarroNo ratings yet

- Clinical GuidelineDocument12 pagesClinical Guidelineazab00No ratings yet

- Cerebral Venous Thrombosis From UptodateDocument20 pagesCerebral Venous Thrombosis From UptodatewbudyaNo ratings yet

- A Study Assess The Knowledge Regarding of Hemophilia Among Female Students in Jazan UniversityDocument14 pagesA Study Assess The Knowledge Regarding of Hemophilia Among Female Students in Jazan Universityشهد خالدNo ratings yet

- Who Uhc Sds 2019.10 EngDocument50 pagesWho Uhc Sds 2019.10 EngChristian ObandoNo ratings yet

- Predanalitika KoagulacijaDocument10 pagesPredanalitika KoagulacijaAnonymous w4qodCJNo ratings yet

- Sampling Lumbar PunctureDocument6 pagesSampling Lumbar PunctureydtrgnNo ratings yet

- Heparin InjectionDocument2 pagesHeparin InjectiongagandipkSNo ratings yet

- GIbleedingDocument23 pagesGIbleedingReinaldi octaNo ratings yet

- ICU protocol 2015 قصر العيني by mansdocsDocument227 pagesICU protocol 2015 قصر العيني by mansdocsWalaa YousefNo ratings yet

- DivitiDocument36 pagesDivitiMarLeniRNNo ratings yet

- Deep Vein ThrombosisDocument5 pagesDeep Vein ThrombosisSiva Malar GanasenNo ratings yet

- Arrhythmias - Cardiovascular Medicine - MKSAP 17Document17 pagesArrhythmias - Cardiovascular Medicine - MKSAP 17alaaNo ratings yet

- CPM8th Acute Stroke TreatmentDocument22 pagesCPM8th Acute Stroke TreatmentCassie OcampoNo ratings yet

- Anticoag BridgeDocument2 pagesAnticoag BridgeAnonymous ZUaUz1wwNo ratings yet

- 2 Phlebotomy Notes Taken From The Lecture of Sir Antonio Pascua JR RMTDocument5 pages2 Phlebotomy Notes Taken From The Lecture of Sir Antonio Pascua JR RMTRhoda Mae CubillaNo ratings yet

- Deep Vein Thrombosis DissertationDocument7 pagesDeep Vein Thrombosis DissertationPaperWriterUK100% (1)

- BR J Haematol - 2022 - Stanworth - A Guideline For The Haematological Management of Major Haemorrhage A British SocietyDocument14 pagesBR J Haematol - 2022 - Stanworth - A Guideline For The Haematological Management of Major Haemorrhage A British SocietyRicardo Victor PereiraNo ratings yet

- Mixing Studies: Connie H. Miller, PHDDocument2 pagesMixing Studies: Connie H. Miller, PHDYan PetrovNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study On Anticoagulant Activity of Different Parts of Achyranthes AsperaDocument7 pagesComparative Study On Anticoagulant Activity of Different Parts of Achyranthes AsperaSamarendra GhoshNo ratings yet

- An Overview of The MATH+, I-MASK+ and I-RECOVER ProtocolsDocument55 pagesAn Overview of The MATH+, I-MASK+ and I-RECOVER ProtocolsMaung OoNo ratings yet

- Cureus 0013 00000017832Document8 pagesCureus 0013 00000017832raulNo ratings yet

- PRP For Hair Loss Pre Post Instructions 10.18Document2 pagesPRP For Hair Loss Pre Post Instructions 10.18Selvabala904260No ratings yet

- Dade InnovinDocument7 pagesDade InnovinchaiNo ratings yet

- Intoxicación Por ApixabanDocument3 pagesIntoxicación Por ApixabanMariana fotos FotosNo ratings yet

- Serum Vs Plasma: Which Specimen Should You UseDocument48 pagesSerum Vs Plasma: Which Specimen Should You UseTanveerNo ratings yet

- Oral Anticoagulation in Patients With Chronic Liver DiseaseDocument23 pagesOral Anticoagulation in Patients With Chronic Liver DiseaseSophia PapathanasiouNo ratings yet

- BIO CHEM SeminarDocument28 pagesBIO CHEM SeminarBello Taofik InumidunNo ratings yet

- Thyme Increase The Levothyroxine Dose by 30-50%: This Is For Mild To Moderate But For Severe We Will Give Him TriptansDocument66 pagesThyme Increase The Levothyroxine Dose by 30-50%: This Is For Mild To Moderate But For Severe We Will Give Him TriptansOuf'ra AbdulmajidNo ratings yet

- Med-Surg Exam #2 Study GuideDocument33 pagesMed-Surg Exam #2 Study GuideCaitlyn BilbaoNo ratings yet