Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Discounting Explainer - Final

Discounting Explainer - Final

Uploaded by

AhsanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Discounting Explainer - Final

Discounting Explainer - Final

Uploaded by

AhsanCopyright:

Available Formats

Discounting 101

How does discounting help decisionmakers understand the costs and benefits of

choices and policies—and how does it apply to climate change?

Explainer by Brian Prest — January 16, 2020

Discounting is the process of converting a value • Money received today can be saved or invested to

received in a future time period (e.g., 1, 10, or even earn a positive rate of return, such as by putting

100 years from now) to an equivalent value received the money into the bank, or by purchasing stocks

immediately. For example, a dollar received 50 years or bonds. Therefore, the value of a dollar received

from now may be valued less than a dollar received today is greater than the value of a dollar received

today—discounting measures this relative value. The in the future, because it can be invested and earn

discounting process is a way to convert units of value a return in the interim.

across time horizons, translating future dollars into

today’s dollars. Discounting is used by decisionmakers The difference between present and future values

to fully understand the costs and benefits of policies makes it difficult to compare costs and benefits over

that have future impacts. This explainer will review the time, and it can affect the outcome of policy analysis.

rationale behind discounting, how the discount rate is Policymakers can use discounting to adjust for this

calculated, and why discounting matters for climate difference and ensure that the costs and benefits of a

policies. policy are compared consistently.

Why Discount? Setting the Discount Rate

Discounting is used to measure the difference between The discount rate represents how much value is

present values and future values. There are a few assigned to benefits received today rather than in the

reasons why this difference exists: future. The effect of different discount rates can be

illustrated with the example of a homeowner considering

• People tend to display impatient behavior, replacing their standard washing machine with a new,

preferring their immediate well-being to future energy-efficient, water-saving one. The homeowner

well-being. This means that people often value has to decide how much they value the future benefits

benefits received sooner more than they value the of replacing the appliance (the money they will save

same benefits received later. on their water and electricity bills, and however much

• People may reasonably expect to grow wealthier they value the environmental benefits of saving water

in the future, because income and wealth have and energy), relative to the immediate costs they will

been increasing on average in the United States incur today to purchase the new appliances. This can be

and globally. If individuals expect to have more represented by different discount rates:

income in the future, then having an extra dollar

today (when they are relatively less wealthy) is • Discount rate of zero: Present benefits and

more valuable than having a dollar in the future future benefits are valued equally—there is no

(when they are relatively more wealthy, and hence preference between receiving a benefit today

consuming more). or in the future. If a homeowner values each

dollar saved in the future from replacing the • High discount rate: Present benefits are

washer equally to each dollar in immediate costs much more valuable than future benefits. If

of replacing it, this could be represented by a a homeowner values each dollar of future cost

discount rate of zero. With a discount rate of zero, savings from the new washer far less than they

the homeowner would choose to buy the energy value each dollar in immediate costs of replacing it,

efficient appliance if the total undiscounted cost this could be represented by a high discount rate.

savings are at least as large as the replacement With a high discount rate, the total undiscounted

cost. cost savings must exceed the replacement costs

• Low discount rate: Present benefits are only by a large amount to convince the homeowner to

slightly more valuable than future benefits. purchase the appliance.

If a homeowner values each dollar of future

cost savings from the new washer slightly less For policy analysis, the discount rate is chosen to

than they value each dollar in immediate costs reflect the rate at which society is willing to trade off

of replacing it, this could be represented by a immediate and future values. Further, a number of

low discount rate. With a low discount rate, the specific questions and issues arise when determining

total undiscounted cost savings must exceed the appropriate discount rate to use when valuing the

the replacement costs by a modest amount to benefits of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

convince the homeowner to purchase the new Some of these questions are described below.

appliance.

In the Weeds: A Discounting Calculation Example

Suppose you can earn a guaranteed return of 3% by putting $1 in a bank account. That $1 will grow to be worth $1.03 in one

year ($1*(1+3%)=$1.03). If we divide both sides of this equation by (1+3%), we have $1=$1.03/(1+3%), which relates the present

value ($1) to the future value ($1.03) and the discount rate (3%). Then we say that, using a discount rate of 3%, the present

value of $1.03 received in one year is $1 today.

If the $1 is in the bank for more than one year, the investment yields compound interest (the interest on the interest). For a

two-year investment, the value would be $1.0609 ($1*(1+3%)*(1+3%)=$1*(1+3%)^2=$1.0609). As before, using a discount rate

of 3%, the present value of $1.0609 received in 2 years is $1.

Compound interest accounts for why the investment grows by 6.09 cents rather than just 6.0 cents (3 cents per year for two

years). Over long time periods, compounding of interest can have significant effects on the calculation results.

Leaving the bank account example behind, the general relationship between the present value (PV), the future value (FV), the

discount rate (r), and the duration of the investment (t) is described by the following formula:

PV = FV/(1+r)^t

Because t, which represents the number of years in the future until the payment is received, appears in an exponential form,

small changes in the discount rate can have large effects on present values. For example, consider a payment of $1,000

received in 200 years. Using a 3% discount rate, the present value can be calculated as follows:

$1,000/(1+3%)^200 = $2.71.

At a slightly higher discount rate of 4%, the present value is calculated to be only $0.39, which is about 7 times smaller.

Resources for the Future — Discounting 101 2

Who should be considered when setting the released today remain for hundreds of years or more.

discount rate? Discounting allows policymakers to measure the present

value of the long-term benefits that come from reducing

There are two different approaches to choosing these greenhouse gas emissions.

the discount rate: the prescriptive (or normative)

approach (how should society trade off current and While the benefits of decreasing emissions are spread

future consumption based on ethical arguments), over hundreds of years, the costs typically occur in the

or the descriptive (or positive) approach (how do short run. This means that the costs will be minimally

individuals and markets trade off current and future affected by discounting, while the benefits—which

consumption based on observed behavior). The are spread across many years in the future—may be

value of each approach for use in policy analysis is significantly affected by discounting. This disparity

a contentious issue, with different analysts having between the timing of the costs and benefits means that

differing opinions about which is best. Even within these discounting can greatly impact the benefit-cost analysis

broad approaches, there are many different ways to of any policy or investment that affects GHG emissions.

apply them.

For example, building a renewable wind farm requires

The prescriptive approach emphasizes philosophical capital investments (short-term costs). Once built, this

and ethical considerations. This approach requires wind farm will reduce emissions over the course of its

making ethical judgments about how much we should lifetime and the benefits will extend even further into the

value peoples’ well-being at different points in time and future, since avoided warming effects last for hundreds

the degree to which the incremental value of a dollar of years (long-term benefits). The present value of the

diminishes as wealth increases (which determines benefits from this wind farm will vary depending on

the relative value placed on impacts on future which discount rate is used, while the present value of

wealthier versus current less-wealthy individuals). The the cost will not be significantly affected by the discount

prescriptive approach for discounting requires making rate.

judgments based on a priori moral reasoning (described

by Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy as reasoning The example below only considers benefits occurring

“without drawing on observations of human beings and 200 years from now. But, in reality, reducing emissions

their behavior”). today has impacts that occur gradually over time, not

just in 200 years but next year, the year after, and

By contrast, the descriptive approach bases discount so on. Each ton of greenhouse gas emitted into the

rates on observable, realized outcomes in society atmosphere has some impact each year into the future.

(typically market interest rates). This approach requires The costs of these annual impacts are discounted

determining which market interest rate is the most (converted to the present value) and added up, and the

appropriate to use (e.g., should the discount rate be the resulting sum is called the social cost of carbon (SCC).

same as the rate of return on bonds, or should it equal Since these costs are discounted over time, the discount

the return on capital investments?) and then estimating rate is a significant determinant of the SCC.

that rate using empirical data.

The Social Cost of Carbon (SCC)

Discounting and Climate Change

As with climate change policy analysis in general, the

Discounting is particularly significant for understanding discount rate plays a substantial role in calculating the

the present value of mitigating climate change. This is SCC, which is “an estimate, in dollars, of the economic

because climate change has long-lasting effects: the damages that would result from emitting one additional

warming effects of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions ton of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.”

Resources for the Future — Discounting 101 3

Doing the Math: What Role Does the Discount Rate Play in Climate Policy?

Suppose you invest $1 in a wind farm in order to mitigate climate change, and the resulting reduction in emissions generates a future

benefit of $1,000 in 200 years. This future value can be converted into a present value, so that it can be compared with present-day

costs and incorporated into policy analysis. To find the present value of this future benefit, we can use the formula from the bank

account example above. The net benefit of this $1 investment, in today’s dollars, is the present value of the future benefit, $1,000/

(1+r)^200, minus the $1 spent today:

Net Benefit = $1000/(1+r)^200 - $1

For a discount rate of 3%, the net benefit of this investment is positive, which means that this investment passes a benefit-cost test:

$1000/(1+3%)^200 - $1 = $2.71 - $1 = $1.71

By contrast, for a slightly higher discount rate of 4%, the net benefit of the wind-farm investment is negative, which means that this

investment does not pass a benefit-cost test:

$1000/(1+4%)^200 - $1 = $0.39 - $1 = -$0.61

This example demonstrates that small changes in the discount rate can have significant effects on the calculation of an investment’s

benefit (or, in other cases, a policy’s benefit). Decisions regarding which discount rate to use can determine whether investments and

policies that mitigate climate change will pass a benefit-cost test. (Of course, it is important to note that benefit-cost analysis is also

only one ingredient in policy decisions, although it is an important one).

Small changes in the discount rate can have significant Climate Change and the Discount

effects on the SCC. For example, when the Trump

administration released its estimates of the SCC using

Rate

discount rates of 3% and 7%, the SCC was reduced by Certain features of climate change suggest using

90% when using a 7% discount rate compared to when a lower discount rate. Here are a few related

using a 3% discount rate ($5 per ton of CO₂ versus $44 considerations:

per ton of CO₂ for a reduction occurring in 2020).

Since the SCC is often used to guide the desired

Does the discount rate take into account the

stringency of regulations, this difference can be values of the next generation?

significant. A regulation reducing emissions at a cost of

$20 per ton would appear favorable using the $44-per- Individuals may value their future personal well-being

ton estimate of the benefit (based on the 3% rate), but less than their current well-being, but does this imply

would not be deemed worthwhile using the $5-per-ton that it is appropriate to place a lower value on benefits

estimate (based on the 7% rate). The cost of many that will be received by future generations simply

potential GHG-reducing actions could fall within this because they were born later? This question raises

range—investments that would be deemed worthwhile ethical issues that have been explored by economists

at the higher SCC value (calculated with a lower and philosophers alike, some of whom argue for using

discount rate) but not the lower one (calculated with a lower discount rates to avoid unfairly penalizing people

higher discount rate). for being born at different times. For example, Ramsey

(1928) argued that discounting future generations

simply because they occur later in time is “ethically

Resources for the Future — Discounting 101 4

indefensible and arises merely from the weakness of the incorrect. The correct approach is to discount the

imagination.” In contrast, others argue that society does future value separately with discount rates of 1% and

have the means to pass on increased wealth to future 7% and then take the average of the two discounted

generations and has tended to do so historically. values. If you had to use a single discount rate that

would get the same result as this correct (but more

How does uncertainty affect which discount complicated) approach, you could calculate the single

discount rate that gives the same result. In this example,

rate we choose?

the calculated* discount rate that produces the correct

Choosing a discount rate generally involves dealing with result is 1.35% (not 4%), which is much closer to the

uncertainty. One approach to dealing with uncertainty lower rate. The longer the time horizon, the lower the

is to use a discount rate that declines over time, rather discount rate that should be used when taking into

than using a single fixed rate for all time periods. This account this uncertainty.

approach implies that, when discounting the distant

future amid uncertainty about the right discount rate to There is also an additional consideration if there

use, we should use a discount rate on the low end of the is a strong correlation between the future value of

range of possible rates. reducing GHG emissions (i.e., the value of avoiding the

consequences of climate change) and the discount rate.

For example, suppose there is a 50/50 chance that the In this case, we must also add a risk premium (that is,

right discount rate over 200 years is either 1% or 7%. use a higher discount rate to reflect the risk associated

Which discount rate should be chosen? An intuitively with the benefit of GHG reductions) to the discount rate

appealing approach may be to use the average of the that depends on the strength of that correlation.

two discount rates, which is 4%— but this would be

*1/(1+1.35%)^200 =50%1/(1+1%)^200 +50%1/(1+7%)^200

Resources for the Future (RFF) is an independent,

nonprofit research institution in Washington, DC. Its

mission is to improve environmental, energy, and natural

resource decisions through impartial economic research

and policy engagement.

Brian Prest is a Postdoctoral Fellow at

Resources for the Future.

Resources for the Future — Discounting 101 5

You might also like

- Solution Manual For Microeconomics 4th Edition by BesankoDocument21 pagesSolution Manual For Microeconomics 4th Edition by Besankoa28978213333% (3)

- McEachern11e - Ch1-The Art and Science of Economic AnalysisDocument53 pagesMcEachern11e - Ch1-The Art and Science of Economic AnalysisLilith GhazaryanNo ratings yet

- Cost-Benefit AnalysisDocument47 pagesCost-Benefit AnalysisDarryl LemNo ratings yet

- Part 6-3 (Role of Government-Uncertainty-Cost Effectiveness Analysis)Document13 pagesPart 6-3 (Role of Government-Uncertainty-Cost Effectiveness Analysis)My LyfeNo ratings yet

- Economics As An Applied ScienceDocument35 pagesEconomics As An Applied ScienceStephanie Ann MARIDABLENo ratings yet

- An Overview of BenefitDocument9 pagesAn Overview of BenefitDivyashri JainNo ratings yet

- Akmen Chap 12Document5 pagesAkmen Chap 12Nadiani NanaNo ratings yet

- Time Value of MoneyDocument7 pagesTime Value of Moneyanand.arora7No ratings yet

- Final Exam ManaDocument7 pagesFinal Exam Manaale montalvnNo ratings yet

- Primer On Social Discount RatesDocument4 pagesPrimer On Social Discount RatesRuth ChiahNo ratings yet

- SEM: Discounted Utility Model (DUM) : 1) Models Incorporating Utility From Anticipation Savoring and DreadDocument4 pagesSEM: Discounted Utility Model (DUM) : 1) Models Incorporating Utility From Anticipation Savoring and DreadGrace SathienwongsaNo ratings yet

- A Short Note On Present Value Calculations: John Crump - For Prof. Dole - Sales & Leasing - Summer 2001 TopicsDocument12 pagesA Short Note On Present Value Calculations: John Crump - For Prof. Dole - Sales & Leasing - Summer 2001 TopicsCarla TateNo ratings yet

- Basic Long Term Financial ConceptsDocument47 pagesBasic Long Term Financial ConceptsJustine Elissa Arellano MarceloNo ratings yet

- Environmental Economics: Lecture 4: Cost - Benefit Analysis and Other Decision Making MetricsDocument21 pagesEnvironmental Economics: Lecture 4: Cost - Benefit Analysis and Other Decision Making MetricsGarang Diing DiingNo ratings yet

- Discount RatesDocument14 pagesDiscount RatesAditya Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Module 3 in AE 11Document7 pagesModule 3 in AE 11Neshl Angelisse BalacantaNo ratings yet

- Economic Principles Assist in Rational Reasoning and Defined ThinkingDocument3 pagesEconomic Principles Assist in Rational Reasoning and Defined ThinkingAbhijeet KulkarniNo ratings yet

- Business Economics - A - SRDocument8 pagesBusiness Economics - A - SRRameshwar BhatiNo ratings yet

- Household BehaviorDocument3 pagesHousehold BehaviorjohserNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Benefit-Cost AnalysisDocument11 pagesAn Overview of Benefit-Cost AnalysisAnand YadavNo ratings yet

- Part 6-2 (Discounting BC-PV-Sensitivity Analysis)Document13 pagesPart 6-2 (Discounting BC-PV-Sensitivity Analysis)My LyfeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Consumer BehaviourDocument5 pagesChapter 5 Consumer BehaviourZyroneGlennJeraoSayanaNo ratings yet

- Business Plan Howard DuckDocument12 pagesBusiness Plan Howard DuckFarhad HussainNo ratings yet

- Engineering EconomyDocument11 pagesEngineering EconomyJune CostalesNo ratings yet

- WK 9 Tutorial 10 Suggested AnswersDocument7 pagesWK 9 Tutorial 10 Suggested Answerswen niNo ratings yet

- PV PrimerDocument15 pagesPV Primerveda20No ratings yet

- What Does Absorption Costing MeanDocument72 pagesWhat Does Absorption Costing MeanKhalfan ZaharaniNo ratings yet

- Behavioural Economics Intertemporal ChoiceDocument3 pagesBehavioural Economics Intertemporal Choiceanne1708No ratings yet

- Cost-Benefit Analysis: by Matthew J. KotchenDocument4 pagesCost-Benefit Analysis: by Matthew J. KotchenJair PachecoNo ratings yet

- Costs HandoutDocument8 pagesCosts HandoutSreePrasanna LakshmiNo ratings yet

- Time Value of MoneyDocument4 pagesTime Value of MoneyTshireletso MphaneNo ratings yet

- Time Value of Money Class 2Document35 pagesTime Value of Money Class 2Shivani -No ratings yet

- Problem Session-2 15.03.2012Document44 pagesProblem Session-2 15.03.2012Chi Toan Dang TranNo ratings yet

- Pricing Fixed Income SecuritiesDocument3 pagesPricing Fixed Income SecuritiesIrfan Sadique IsmamNo ratings yet

- Engineering EconomicsDocument43 pagesEngineering EconomicsBeverly Paman100% (3)

- Fundamental Concepts of MEDocument36 pagesFundamental Concepts of MEShivang GuptaNo ratings yet

- Cost Accounting Chapter 4 0Document15 pagesCost Accounting Chapter 4 0FaioNo ratings yet

- Problem Session-2 - 15.03.2012Document44 pagesProblem Session-2 - 15.03.2012markydee_20No ratings yet

- Managing Interest RateDocument22 pagesManaging Interest RatemahadiparvezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Interest Rates in The Financial SystemDocument17 pagesChapter 2 Interest Rates in The Financial SystemybegduNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Engineering CostsDocument34 pagesChapter 2 Engineering CostsShudipto PodderNo ratings yet

- Principles of Managerial EconomicsDocument2 pagesPrinciples of Managerial EconomicsVarun KalseNo ratings yet

- Time Value of MoneyDocument7 pagesTime Value of MoneyRishab Jain 2027203No ratings yet

- H3 Theme 1 Assignment Suggested AnswerDocument6 pagesH3 Theme 1 Assignment Suggested Answer23S46 ZHAO TIANYUNo ratings yet

- 3Document2 pages3Sara AlnahdiNo ratings yet

- Time Value of MoneyDocument16 pagesTime Value of MoneyAnmol Shrestha100% (1)

- Assignment 2: DecisionDocument1 pageAssignment 2: DecisionUzair KhanNo ratings yet

- Sequence 5 - Life Cycle Costing - Engineering EconomicsDocument30 pagesSequence 5 - Life Cycle Costing - Engineering EconomicsZeeshan AhmadNo ratings yet

- Economics: EE 394J10 Distributed TechnologiesDocument30 pagesEconomics: EE 394J10 Distributed TechnologiesfarazhumayunNo ratings yet

- Why We Should Value The Environment? and When?: Anil MarkandyaDocument4 pagesWhy We Should Value The Environment? and When?: Anil MarkandyaSatendra KumarNo ratings yet

- Consumption SavingsDocument68 pagesConsumption SavingskhatedeleonNo ratings yet

- Financial - Management Book of Paramasivam and SubramaniamDocument21 pagesFinancial - Management Book of Paramasivam and SubramaniamPandy PeriasamyNo ratings yet

- Price Elasticity of Demand Research PaperDocument4 pagesPrice Elasticity of Demand Research Paperafeaxbgqp100% (1)

- Profitable Decision MakingDocument28 pagesProfitable Decision MakingchessyNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Concept of Managerial EconomicsDocument3 pagesFundamental Concept of Managerial EconomicsANSH SONINo ratings yet

- Ae11 Reviewer Midterm Exam For DistributionDocument6 pagesAe11 Reviewer Midterm Exam For Distributionfritzcastillo026No ratings yet

- Chapter One: Definition and Basic Terms and Terminology of Engineering EconomyDocument16 pagesChapter One: Definition and Basic Terms and Terminology of Engineering EconomyamrNo ratings yet

- San José State UniversityDocument18 pagesSan José State UniversityDivyashri JainNo ratings yet

- Module4 - Extent DecisionsDocument6 pagesModule4 - Extent DecisionsSindac, Maria Celiamel Gabrielle C.No ratings yet

- 07 Handout 140Document5 pages07 Handout 140mitchelalteranNo ratings yet

- An MBA in a Book: Everything You Need to Know to Master Business - In One Book!From EverandAn MBA in a Book: Everything You Need to Know to Master Business - In One Book!No ratings yet

- Cost & Managerial Accounting II EssentialsFrom EverandCost & Managerial Accounting II EssentialsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Eval CreditDocument1 pageEval CreditAhsanNo ratings yet

- Route 411: IntroducingDocument2 pagesRoute 411: IntroducingAhsanNo ratings yet

- آٹھویں روزے کی عبادتDocument8 pagesآٹھویں روزے کی عبادتAhsanNo ratings yet

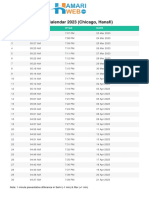

- Chicago-Ramadan-Calender 2023Document1 pageChicago-Ramadan-Calender 2023AhsanNo ratings yet

- Sociology Project: Madras School of Social WorkDocument10 pagesSociology Project: Madras School of Social WorkJananee RajagopalanNo ratings yet

- Berger Paints M MixDocument4 pagesBerger Paints M MixMax CharadvaNo ratings yet

- Human Development IndexDocument4 pagesHuman Development IndexKruthik VemulaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Financial ManagementDocument25 pagesThe Role of Financial Managementbara setyantoNo ratings yet

- D2 Itibaev KairatDocument22 pagesD2 Itibaev KairatIvana WijayaNo ratings yet

- Technology Transfer Principle & EstrstegyDocument10 pagesTechnology Transfer Principle & EstrstegyJorge Rodriguez MNo ratings yet

- 6 KZPK 7 Cqs 9 ZazDocument24 pages6 KZPK 7 Cqs 9 ZazNelunika HarshaniNo ratings yet

- Financial Services Dumping - Priscilla CarriónDocument2 pagesFinancial Services Dumping - Priscilla CarriónAndrea Carrion100% (2)

- Herman Miller: A Case of Reinvention and RenewalDocument15 pagesHerman Miller: A Case of Reinvention and RenewalUmair Dar100% (1)

- AFM Exam Focus Notes 1st PartDocument28 pagesAFM Exam Focus Notes 1st Partmanish kumarNo ratings yet

- Industrialization in The CaribbeanDocument20 pagesIndustrialization in The CaribbeanAlicia RampersadNo ratings yet

- 7.3 - Efficiency and Market Failure (S)Document71 pages7.3 - Efficiency and Market Failure (S)l PLAY GAMESNo ratings yet

- Financial DerivativesDocument31 pagesFinancial DerivativesSyed Roshan JavedNo ratings yet

- Auditoria II 2021 OkDocument67 pagesAuditoria II 2021 OkDark BrownNo ratings yet

- Chap 03Document16 pagesChap 03Syed Hamdan100% (1)

- The Role of Deposit Money Banks' Loan Facilities in Financing Small and Medium-Scale Enterprises in NigeriaDocument8 pagesThe Role of Deposit Money Banks' Loan Facilities in Financing Small and Medium-Scale Enterprises in NigeriaAkingbesote VictoriaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Is Power, So Be As Powerful As You Can!Document27 pagesKnowledge Is Power, So Be As Powerful As You Can!Ahemad ShamimNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Economics - Chapter 9Document13 pagesFundamentals of Economics - Chapter 9Alya SyakirahNo ratings yet

- Power Purchase AgreementDocument2 pagesPower Purchase AgreementDyabbie Bisa-TagumNo ratings yet

- Ma Ehp - SyllabiDocument35 pagesMa Ehp - SyllabiMei-Ann Cayabyab-PatanoNo ratings yet

- Https Docs - Google.com Spreadsheet FM Id TswWmqocm6KnY-KW7WfLrqA - Pref 06872257018252351705Document10 pagesHttps Docs - Google.com Spreadsheet FM Id TswWmqocm6KnY-KW7WfLrqA - Pref 06872257018252351705Banu Prasad SekarNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship: Nature and Relevance of EntrepreneurshipDocument17 pagesEntrepreneurship: Nature and Relevance of EntrepreneurshipGilbert Gonzales100% (1)

- A2 MicroEconomics Summary NotesDocument106 pagesA2 MicroEconomics Summary Notesangeleschang99No ratings yet

- Chapter 8 NotesDocument6 pagesChapter 8 NotesXiaoNo ratings yet

- Indian Money MarketDocument6 pagesIndian Money MarketvrushalispNo ratings yet

- Microeconomics - Multiple Choice - SentDocument8 pagesMicroeconomics - Multiple Choice - Sentsơn trầnNo ratings yet

- Evan J. Horowitz: ObjectiveDocument1 pageEvan J. Horowitz: Objectiveok00l14No ratings yet

- International Business Assignment PDFDocument7 pagesInternational Business Assignment PDFAyesha RashidNo ratings yet