Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SSRN Id2802426

SSRN Id2802426

Uploaded by

hmehmi08Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SSRN Id2802426

SSRN Id2802426

Uploaded by

hmehmi08Copyright:

Available Formats

CEO Severance Pay and Corporate Tax Planning

John L. Campbell

University of Georgia

johnc@uga.edu

Jenny Xinjiao Guan

Monash University

jenny.guan@monash.edu

Oliver Zhen Li

Shanghai Lixin University of Accounting and Finance

lizhen@lixin.edu.cn

Zhen Zheng*

Xiamen University

zhenzheng@xmu.edu.cn

June 2019

Running Head: CEO Severance Pay and Corporate Tax Planning

* Corresponding author. We appreciate helpful comments and suggestions from two anonymous reviewers, Kris Allee (discussant),

Steve Baginski, Ted Christensen, Matt DeAngelis, Dan Dhaliwal, Jeremy Douthit, Anne Ehinger, Paul Fischer, Fabio Gaertner

(discussant), Cristi Gleason, Michelle Hanlon, Ken Klassen, Robbie Moon, Santhosh Ramalingegowda, Susan Shu (discussant),

Anup Srivastava (discussant), Bridget Stomberg, Jake Thornock, Erin Towery, Dan Wangerin, James Warren, Connie Weaver,

Ben Whipple, Jaron Wilde (discussant), workshop participants at the University of Georgia and the National University of

Singapore, conference participants at the 2016 MIT Asia Conference in Accounting, 2017 Financial Accounting and Reporting

Section (FARS) Midyear Meeting, the 2017 Journal of the American Taxation Association (JATA) Conference, the 2017 Center

for the Economic Analysis of Risk (CEAR) accounting conference at Georgia State University, and the 2017 American Accounting

Association (AAA) Annual Meeting. Zhen Zheng acknowledges the grants from NSFC (No. 71702160, 71790602, 71772156) and

the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 20720171077).

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

CEO Severance Pay and Corporate Tax Planning

Abstract

We examine the association between CEO severance pay (i.e., payment a CEO would receive if

s/he is involuntarily terminated) and corporate tax planning activities. We find that CEO severance

pay is positively associated with corporate tax planning, consistent with CEO severance pay

providing contractual protection against managers’ career concerns and thereby inducing

otherwise risk-averse managers to engage in incremental levels of tax planning. This result holds

under an instrumental variable approach and a propensity score matching, and survives alternative

measures of CEO severance pay and corporate tax planning. Finally, we find that severance pay

provides stronger tax planning incentives in situations where managers are expected to face greater

career concerns – when they are less experienced, when they face stronger shareholder monitoring,

and when they manage firms with higher idiosyncratic volatility. Overall, our results suggest that

CEO severance pay represents a form of efficient contracting with otherwise risk-averse managers.

Keywords: corporate tax planning; CEO severance pay; risk-taking incentives

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

INTRODUCTION

Corporate tax planning activities have the potential to increase shareholders’ after-tax wealth,

but can also subject managers to risk.1 Tax planning increases a firm’s expected cash flows (from

the expected tax savings), but also increases the dispersion of these cash flows, widening the

probability distribution of future cash flows (Goh, Lee, Lim, and Shevlin 2016). Tax planning,

thus, is analogous to value-increasing investment projects favored by risk-neutral shareholders

(who can diversify risk), but not necessarily by risk-averse managers (who are under-diversified

with their wealth and human capital, and thus tend to avoid risk). To alleviate this tax-related

agency problem, shareholders can design compensation contracts that induce otherwise risk-averse

managers to take more risk (Crocker and Slemrod 2005).

Recent research finds that stock-based compensation contracts encourage CEOs to take more

risks and, thus, engage in more tax planning (Rego and Wilson 2012; Armstrong, Blouin,

Jagolinzer, and Larcker 2015). However, stock options only provide managers with upside gain

potential, and fail to protect managers from downside risk (Cadman, Campbell, and Klasa 2016).

Downside risk protection is important in the tax setting because tax positions have been shown to

draw scrutiny from outside parties (i.e., the IRS, the SEC, analysts, and the media), and thus have

the potential to attract unwanted attention on CEOs and their firms (Bozanic, Hoopes, Thornock,

and Williams 2017; Kubick, Lynch, Mayberry, and Omer 2016; Ehinger, Lee, Stomberg, and

Towery 2017; Chen, Powers, and Stomberg 2016). This attention can even potentially lead to CEO

job termination (Chyz and Gaertner 2018).

1

We define tax planning broadly as any action that reduces firms’ explicit tax liability. A high level of tax planning

decreases firms’ explicit tax liability to a greater extent, and thus represents particularly risky tax positions. We use

the term “a high level of tax planning” or “risky tax positions” throughout to describe firms’ aggressiveness in reducing

the explicit tax liability.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

Prior research provides evidence that severance pay reduces managers’ career concerns and

encourages otherwise risk-averse managers to take higher levels of risk (Ju, Leland, and Senbet

2014; Chen, Cheng, Lo, and Wang 2015; Cadman et al. 2016). In this study, we examine whether

the increased risk-taking behavior induced by severance pay extends to the tax setting. As in these

other risk-taking settings, it is not necessary to assume that a CEO believes that s/he will be fired

solely for engaging in incremental tax planning. Rather, as long as tax planning increases the

attention paid to a CEO in a way that would increase her/his career concerns, and this expected

increase in career concerns prevents the CEO from taking these tax positions, severance pay will

mitigate this tendency and the CEO will take more tax risks than s/he would absent the severance

pay.

Severance pay represents a significant portion of CEOs’ compensation package, as over 75

percent of S&P 1500 firms have sizeable severance agreements with their CEOs (Cadman et al.

2016).2 Using a hand-collected sample of severance pay amounts, we find a positive association

between CEO severance pay and corporate tax planning, after controlling for risk-taking incentives

from stock options (i.e., delta and vega) as well as other known determinants of tax planning

activities (i.e., firm size, firm age, operating volatility, R&D, capital expenditures, leverage, and

foreign operations). We find this association when using firms’ GAAP and cash effective tax rates

(ETRs) to proxy for the level of tax planning as well as two additional measures that proxy for

firms’ tax planning: tax settlements with the IRS, and unrecognized tax benefits. Overall, our

findings imply that severance pay encourages otherwise risk-averse managers to engage in

incremental tax planning activities, and that it represents a form of efficient contracting between

shareholders and managers (Ju et al. 2014; Cadman et al. 2016).

2

Over the last decade, the ten largest CEO severance payouts cost shareholders over $2.4 billion (GMI 2013).

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

As with all empirical compensation analyses, our tests present associations for which we cannot

definitively ascribe causality. We mitigate the likelihood that our results are driven by endogeneity

through two additional analyses. First, we use propensity score matching to alleviate functional

form misspecification by matching high and low severance pay firms on non-severance observable

characteristics. Our result continues to hold. Second, we use an instrumental variable approach to

alleviate any correlated omitted variable bias. As instruments, we use a firm’s geographic

proximity to its local largest severance payer as well as the local median severance pay. Tests of

instrument strength and over-identification indicate that our instruments are not weak or over-

identified. Our result continues to hold.

To better understand the underlying mechanism that links severance pay to tax planning

activities, we perform a set of cross-sectional tests. If CEO severance pay increases corporate tax

planning because it reduces managers’ career concerns and protects otherwise risk-averse

managers against downside risk, such an effect should be stronger when CEOs face greater career

concerns. We find that CEO severance pay exhibits a stronger association with corporate tax

planning when CEOs are less experienced with their firms, face stronger shareholder monitoring,

and operate in firms with higher idiosyncratic volatility – situations where managers are expected

to face greater career concerns. Thus, managers with greater career concerns appear to be more

sensitive to the incentive effect of CEO severance pay.

Our study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, we further explain the variation in

corporate tax planning activity. The fact that some firms engage in more tax planning activities

than others is puzzling and not fully understood (Shevlin 2007; Hanlon and Heitzman 2010). The

majority of prior literature seeks to explain the determinants of tax planning by focusing on firm

characteristics (e.g., size, profitability, capital structure, foreign income, accounting metrics to

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

evaluate performance) and manager characteristics (e.g., education, ability, political affiliation,

personal tax aggression) (Gupta and Newberry 1997; Wilson 2009; Dyreng, Hanlon, and Maydew

2010; Chyz 2013; Christensen, Dhaliwal, Boivie, and Graffin 2015). More recent studies suggest

that a possible explanation for the substantial variation in corporate tax planning activities is the

heterogeneity in managerial incentives. We complement these studies, providing evidence that one

particular form of managerial incentives (i.e., CEO severance pay) can at least partially explain

the large variance in corporate tax planning activities.

Second, we add to the literature on compensation contracts and corporate tax planning. Prior

studies focus primarily on the risk incentives provided by stock options. Findings related to these

contracts largely suggest that they provide incentives for managers to engage in incremental tax

planning (Phillips 2003; Desai and Dharmapala 2006; Rego and Wilson 2012; Gaertner 2014;

Armstrong et al. 2015; Powers, Robinson, and Stomberg 2016). Importantly, these studies examine

compensation contracts that only provide incentives when firm performance is positive. In contrast,

we examine a compensation agreement, CEO severance pay, that completes the spectrum of

compensation incentives provided to risk-averse CEOs by mitigating their career concerns (i.e.,

providing protection for downside risk). Such evidence is important in light of recent research

showing that tax risk can result in an increase in the probability of an IRS audit, an SEC comment

letter, high analyst scrutiny and media attention (Kubick et al. 2016; Chen et al. 2016; Bozanic et

al. 2017; Ehinger et al. 2017). Furthermore, extreme tax planning can damage a firm’s reputation

and value (Graham, Hanlon, Shevlin, and Shroff 2014) and even result in CEO turnover (Chyz

and Gaertner 2018).

Third, our study extends the literature on CEO severance pay. Theoretical work suggests that

CEO severance pay provides a risk taking incentive due to its unique role in contractual protection

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

against managers’ downside risk. Motivated by this argument, prior research finds that severance

pay encourages managers to take risks that increase firm value (Almazan and Suarez 2003; Chen

et al. 2016; Cadman et al. 2016; Baginski, Campbell, Hinson, and Koo 2018). We extend this

empirical work to the tax setting, where tax scholars are gradually adopting the view that

investment in corporate tax planning can be risky. Our findings support the notion that severance

pay represents a form of efficient contracting that encourages otherwise risk averse managers to

take more risk. Similarly, our results are inconsistent with the idea that severance contracts

represent agency costs and are only obtained by powerful, entrenched CEOs.3

Finally, our study has practical implications. As a prevalent compensation practice, severance

pay has received a lot of attention from practitioners and regulators. As recounted in an article on

www.thestreet.com, “It’s one thing when a CEO gets paid millions of dollars for a job well done,

but these executives made off like bandits despite failing in their roles” (Fiegerman 2010). Our

findings, taken together with other severance research, suggest that arguments such as this can

‘miss the point’ because they focus strictly on the ex post termination payout amount. However,

our results suggest that ex ante severance pay, on average, provides incentives for otherwise risk-

averse managers to take value-increasing risks.

LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

Corporate Tax Planning within an Agency Framework

3

We are aware of the existence of a contemporaneous paper, Brown, Dong, and Ke (2016), that also examines the

association between severance agreements and tax avoidance. Brown et al.’s sample begins in 1992, long before the

SEC mandated disclosure of severance. Thus, their severance data rely heavily on firms’ voluntary disclosure of

severance. Furthermore, Brown et al. (2016) build on Desai and Dharmapala (2006)’s entrenchment view of corporate

tax planning, which has been challenged by recent studies (Gallemore and Labro 2015; Lennox, Lisowsky, and

Pittman 2013; Blaylock 2016). Our cross-sectional tests provide evidence that our results are stronger when managers

are less likely to be entrenched (e.g., lower tenure). This result is consistent with our managerial risk-taking

explanation and inconsistent with Brown et al. (2016)’s management entrenchment explanation.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

Seminal work by Allingham and Sandmo (1972) lays the theoretical foundation for individual

tax planning bevahior. The optimal amount of individual tax planning increases in the income tax

rate, but decreases in the probability of being detected, the amount of the tax penalty due upon

detection, and the extent to which an individual is risk averse.

Slemrod (2004) argues that this simple framework does not necessarily apply to corporate tax

planning as modern corporations feature the separation of ownership and control. Shareholders,

holding well-diversified portfolios, are risk-neutral. They favor all activities that are expected to

add to shareholder value (Merton 1973; Jensen and Meckling 1976). Managers, however, invest

their human capital in specific firms. They are not able to diversify their portfolios in a manner

similar to shareholders. By definition, then, risk-averse managers do not take the level of risk

desired by shareholders (Chen and Chu 2005). Therefore, incentive plans need to be in place to

induce otherwise risk-averse managers to engage in corporate tax planning.

Empirical work on the association between managerial incentives and corporate tax planning

largely focuses on risk-based incentives such as bonus contracts, stock options and stock awards.

However, to date, the empirical findings are mixed. Phillips (2003) finds no evidence that bonus

contracts (based on after-tax earnings) encourage CEOs to engage in tax planning activities.

However, this incentive appears to work for business unit managers and tax department managers

(Phillips 2003; Robinson, Sikes, and Weaver 2010). Using an expanded sample, Gaertner (2014)

finds that linking bonuses to after-tax earnings does encourage CEOs to engage in more tax

planning. Furthermore, Powers et al. (2016) find that linking CEOs’ bonus to after-tax earnings

encourages them to report lower GAAP ETRs but similar Cash ETRs. In addition, using cash flow

metrics to evaluate CEOs’ performance for bonuses is associated with lower GAAP and cash ETRs

than using earnings metrics.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

Related to stock options, Desai and Dharmapala (2006) use firm fixed effects regressions and

find a negative association between stock options and the level of corporate tax planning. However,

Rego and Wilson (2012) find that stock options increase corporate tax planning, as stock options

provide CEOs with convex payoffs by linking option values to stock return volatility. This feature

of stock options (i.e., vega) induces risk-averse managers to engage in risky tax planning to pursue

upside gain potential. Finally, Armstrong et al. (2015) find that, on average, stock options provide

only modest tax planning incentives. Instead, results from their quantile regressions show that

options matter the most when corporate tax planning is either extremely high or extremely low.

CEO Severance Pay and Corporate Tax Planning

CEO severance pay plays a unique role in providing managers with downside risk protection.

Figures 1 through 3 illustrate how a severance contract functions differently than stock options and

bonus contracts. As shown in Figure 1, economic agents (including managers) have concave utility

functions. Winning $1,000 increases her/his utility by an amount less than losing $1,000 decreases

his/her utility. Thus, the manager is risk-averse, and this risk-aversion deters her/him from taking

the level of risk that risk-neutral shareholders prefer. To mitigate this agency problem and to

encourage the manager to be more risk-neutral, a firm can choose to grant her/him stock options.

Figure 2 presents the payoff function of a stock option.4 The option is “in-the-money” only when

the market price exceeds the strike price, otherwise the option has zero intrinsic value. Due to its

convex payoff function, the stock option helps bring the manager’s incentives more in line with

risk-neutral shareholders by effectively straightening out (i.e., removing the concavity of) the

upside of the manager’s utility function. On the other hand, severance pay plays a distinct role.

Figure 3 shows the payoff function of severance pay. It becomes “in-the-money” when the

4

Bonus contracts based on after-tax earnings offer similar incentives as options (i.e., only provide payment upon good

future outcomes). Thus, for brevity, we only discuss options in this example.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

manager is close to being involuntarily terminated, and is worthless when the manager can safely

retain her/his job. Therefore, severance pay has a convex payoff function which straightens out

(i.e., removes the concavity of) the downside of the manager’s utility function. Putting these

together, a combination of stock options and severance pay can motivate the manager to be more

risk-neutral than either contract can do alone (Almazan and Suarez 2003; Ross 2004; Ju et al.

2014).

Prior studies find evidence consistent with the above theoretical analysis that CEO severance

pay reduces managers’ career concerns and induces them to take a higher level of risk than they

would otherwise take. In particular, Cadman et al. (2016) find that CEO severance pay increases

stock return volatility, the level and the change in firm leverage, and same-industry (rather than

diversifying) acquisitions. They also find that CEO severance pay is positively associated with

acquisition announcement returns and the value of cash holdings, consistent with CEO severance

pay motivating managers to undertake not only risky projects but also projects with a positive net

present value. Brown, Jha, and Pacharn (2015), focusing on the financial sector, find that CEO

severance pay is positively associated with market-based risk after controlling for the incentive

effect of equity-based compensation. This suggests that severance pay induces risk taking.

Consistent with this strand of literature, we expect that CEO severance pay encourages tax-

related risk taking. First, tax positions have been shown to draw scrutiny from outside parties, and

therefore have the potential to attract unwanted attention on CEOs and their firm. Specifically,

prior research finds that tax planning activities can generate attention from the IRS (Bozanic et al.

2017), the SEC (Kubick et al. 2016), analysts (Ehinger et al. 2017), and the media (Chen et al.

2016). In addition, public revelations of tax planning activities can induce outside parties to

question the existence of other possible unethical activities undertaken by CEOs (Hanlon and

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

Slemrod 2009). These negative public images can harm CEOs’ reputation and limit their

bargaining power in the labor market (i.e., their career concerns) (Hirshleifer 1993; Graham et al.

2014; Austin and Wilson 2017). In extreme cases, tax planning activities can result in CEO

turnover. Specifically, Chyz and Gaertner (2018) find that an extremely high level of corporate tax

planning is positively associated with the likelihood of a forced CEO turnover.5 These results

suggest that career concerns can discourage managers from undertaking particularly high levels of

corporate tax planning.

Based on the analyses above, we expect that severance contracts alleviate managers’ career

concerns which in turn encourage managers to engage in higher levels of tax planning. Anecdotal

evidence supports this argument. Xerox Corporation offered severance contracts to its executives.

Under such contractual protection, the CEO of Xerox, Richard Thoman, shifted corporate

operations to low-tax Ireland to lower its effective tax rate. However, tax benefits were not

achieved due to losses incurred in Ireland, and this in turn inflated the firm’s effective tax rate.

This income shifting for tax purposes was considered a “big mistake,” and in the end resulted in a

forced CEO turnover.6 Upon termination, Richard Thoman received severance payments in the

form of cash payment ($375,000) and immediate vesting of unvested pension ($800,000 per year),

and thus was compensated for losses due to his dismissal.

That said, it is not necessary to assume that a CEO must believe that s/he would be terminated

solely for taking incremental tax positions. Instead, all a CEO needs to believe is that incremental

tax positions have the potential to come under scrutiny from the IRS/SEC/analysts/media/board of

directors, will attract unwanted attention, put them on thin ice with the board of directors and

5

Chuck Collins. CEOs Rewarded for Tax Dodging Gymnastics. The Huffington Post. Oct 31, 2011.

6

See the following media coverage for more details. James Bandler and Mark Maremont Staff Reporters of The

Wall Street Journal. How Xerox's Plan to Reduce Taxes While Boosting Earnings Backfired. The Wall Street

Journal. April 17, 2001.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

shareholders, and cause them to be closer to termination (i.e., increase their reputational cost and/or

career concerns). As previously argued, prior research establishes that severance pay can mitigate

managers’ career concerns and encourage them to take incremental levels of risk (Cadman et al.

2016; Baginski et al. 2018). If tax planning increases the attention paid to a CEO in a way that

would increase her/his career concerns, and this expected increase in career concerns prevents the

CEO from taking these tax positions, severance pay will mitigate this problem and the CEO will

take more tax risk than s/he would absent the severance pay. This leads to our main hypothesis:

H1: There is a positive association between CEO severance pay and corporate tax planning.

On the other hand, it is possible that the general risk-taking activities encouraged by severance

pay do not extend to corporate tax planning decisions. Several prior studies point to this possibility.

Specifically, in contrast to Chyz and Gaertner (2018), Gallemore, Maydew, and Thornock (2014)

find no evidence that CEOs are fired after public revelations of corporate tax sheltering.

Furthermore, Chen et al. (2016) find no adjustment of tax positions after negative media coverage

on corporate tax planning. Finally, most tax planning strategies survive IRS audits to yield positive

cash tax savings (Nessa, Schwab, Stomberg, and Towery 2016). Thus, it is possible that the

attention created by risky tax positions (from the IRS, the SEC, analysts, the media, the board of

directors) does not affect a CEO’s career concerns. If so, CEO severance pay will not be associated

with corporate tax planning.

DATA and SAMPLE

Hand-collected Data on CEO Severance Pay

On August 11, 2006, the SEC released new disclosure requirements regarding executive

compensation. As a result, firms are now required to quantify and disclose contracted severance

pay that CEOs would receive upon forced termination, either without cause or for good reasons

10

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

(as defined in the contracts). Prior to this change in regulation, disclosures of severance pay only

included whether such a contract existed and a narrative description of any material payments.

Further, these disclosures did not distinguish between whether the payments were already vested

(i.e., the CEO would receive them regardless of termination) or unvested (i.e., amounts that will

only be received by a CEO upon dismissal). Detailed information on CEO severance pay contracts

was only publicly disclosed once the CEO departed from the firm. 7 In contrast, firms now must

quantify and disclose all components of severance pay, including the unvested portion of the

payment (i.e., the amount that will be received by a CEO only upon dismissal). This requirement

enables researchers to examine the ex ante impact of CEO severance pay on corporate tax planning

in a comprehensive manner (Cadman et al. 2016).

We examine firms’ proxy statements (DEF-14, DEF-14A, or item 11 of Form 10-K) and hand-

collect the exact amount of each component of severance pay. A CEO will receive these payments

if s/he is dismissed “without cause” or resigns for “good reason” (see Cadman et al. (2016) for a

detailed description of these scenarios). We collect the total amount of severance payments, the

cash payment portion (e.g., salary and bonus continuation up to a certain number of years after

termination), the portion comprised of continuation of healthcare and other benefits, the unvested

stock options and stock awards that vest immediately upon dismissal, the incremental pension

benefits that vest upon dismissal, and other uncategorized portions.

We use hand-collected severance data rather than those provided by ExecuComp as Cadman et

al. (2016) identify several problems with the ExecuComp data. For example, when firms present

7

The restricted sample size problem and potential self-selection bias make ex post CEO severance pay a less attractive

setting compared with ex ante CEO severance pay. Furthermore, Cadman et al. (2016) show that when a CEO is

involuntarily terminated, the ex post payment is virtually identical to the ex ante contracted amount (ratio of ex post

payout to ex ante contracted amount of 1.04, correlation between the two of 0.99). This provides reasonable assurance

that the severance pay a CEO should expect to receive upon involuntary termination is the contracted amount provided

ex ante.

11

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

tables that do not report a “total” amount for severance payments, ExecuComp incorrectly reports

the first or last number in a column as the total. Also, ExecuComp includes vested payments to a

CEO, which do not reflect the incremental severance pay to the CEO if s/he is dismissed. Finally,

ExecuComp reports a zero value for severance pay in some cases when firms do in fact have

contracted payments disclosed in the proxy statements.8 Due to these issues with ExecuComp data,

our analyses rely on more accurate hand-collected data from firms’ proxy statements. Empirical

analysis presented in Appendix B presents the results of our tests if we use ExecuComp data rather

than our hand-collected sample. Our results do not hold on this sample, further highlighting the

need for our hand collected (i.e., less noisy) severance pay data.

Sample Selection

We start with firms covered in the ExecuComp for the years (i.e., 2006 and 2007) for which we

hand-collected severance pay data.9 We exclude financial firms, firms with foreign headquarters,

and firms with missing data to construct our regression variables. Our final sample consists of

1,413 firm-year observations. Among these observations, 661 fall in the fiscal year of 2006 and

752 in the fiscal year of 2007. We winsorize all continuous variables at the 1 and 99 percentiles to

remove the impact of outliers.

CEO SEVERANCE PAY AND CORPORATE TAX PLANNING

Empirical Model

We estimate the following empirical model to assess the association between CEO severance

pay and corporate tax planning:

TPi,t = β0 + β1SERPAYi,t + β2SIZEi,t + β3ROAi,t + β4LEVi,t + β5MBi,t + β6FIRMAGEi,t

+ β7MNEi,t + β8RDi,t + β9CAPXi,t + β10PPEi,t + β11INTANGi,t + β12EQINCi,t

8

These firms disclosed severance payments in narrative form instead of tabular form, resulting in ExecuComp

mistakenly coding a zero amount of severance pay.

9

As the new requirements apply to firms with fiscal year end after December 15, 2006, we also collect data for 2007

to ensure we have at least one full year for all firms in our sample.

12

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

+ β13NOLi,t + β14DNOLi,t + β15CEOAGEi,t +β16CEOTENUREi,t

+ β17MSHAREi,t + β18VEGAi,t + β19DELTAi,t + ∑YEAR + ∑INDUSTRY + εi,t, (1)

where i and t index firm and year, respectively. The dependent variable is corporate tax planning

(TP). We use effective tax rate as our main proxy for corporate tax planning. This is consistent

with Crocker and Slemrod’s (2005) theoretical argument that “[t]o align incentives, it may be

appropriate for the tax officer’s salary to depend (inversely) on the effective tax rate achieved.”

Thus, effective tax rate is an established proxy for our theoretical construct, especially under the

setting of agency conflicts. In addition, prior research shows that lower ETRs are associated greater

tax uncertainty (Dyreng, Hanlon, and Maydew 2018), and attract unwanted attention from the IRS

(Bozanic et al. 2017), the SEC (Kubick et al. 2016), analysts (Ehinger et al. 2017), and the media

(Chen et al. 2016).10 Such intense public attention is the main source of riskiness of corporate tax

planning that results in managers’ career concerns. Therefore, ETR is an appropriate proxy in our

setting. However, as noted in Hanlon and Heitzman (2010), effective tax rate can be calculated in

a number of ways, and the use of a single effective tax rate measure in isolation may not accurately

capture the extent of corporate tax planning. Specifically, total tax expense that constitutes the

calculation of GAAP effective tax rate includes certain accounting items such as valuation

allowances that are more broadly related to the firm’s profitability in general rather than specific

to tax planning (Dyreng, Hanlon, and Maydew 2008). Cash effective tax rate, defined as cash taxes

paid over pre-tax income, can reduce this impact. For these reasons, we use both GAAP ETR and

Cash ETR to capture the level of corporate tax planning. Both ETR measures are winsorized to be

within 0 and 1. To the extent that ETRs can be noisy in measuring corporate tax planning, we use

two additional tax measures (tax settlements and unrecognized tax benefits) in robustness tests.

10

For example, the New York Times revealed, “The official corporate rate is 35 percent, yet PG&E, the California-

based utility company, has paid zero net taxes since 2007.”

13

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

The variable of interest is the amount of a CEO’s severance pay. We follow Cadman et al. (2016)

and deflate CEO severance pay by CEO wealth defined as the market value of firm equity shares

held by the CEO. We also use alternative deflators in robustness tests to ensure that our measure

of CEO severance pay is not sensitive to alternative scalers. Our main focus is the coefficient on

SERPAY, which captures the effect of CEO severance pay on corporate tax planning. A negative

coefficient on SERPAY would support the notion that CEO severance pay encourages managers to

engage in corporate tax planning.

We control for other variables shown in the prior literature to be related to corporate tax

planning. We first control for a set of firm characteristics, including firm size (SIZE), firm

profitability (ROA), leverage ratio (LEV), firm maturity (MB and FIRMAGE), foreign operation

(MNE), firm investment (CAPX), capital and R&D intensity (PPE and RD), asset tangibility

(INTANG), equity income in earnings (EQINC), and loss carry forward (NOL and DNOL). Next,

we control for a set of variables that capture managerial characteristics and incentives, including

CEO age and tenure (CEOAGE and CEOTENURE), managerial ownership (MSHARE), and stock

option vega and delta (VEGA and DELTA). Variables are defined in Appendix A. Industry and

year fixed effects are also included.

Descriptive Statistics

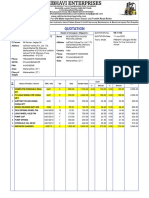

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics of our severance data as well as of our regression variables.

Panel A of Table 1 reports CEO compensation information. The average contracted severance pay

of our sample is $6.0 million, while the counterpart reported in ExecuComp is $7.1 million. This

is likely due to the fact that, as previously mentioned, ExecuComp includes as severance pay

amounts that a CEO has already “earned.” We also report the mean values of various components

of severance pay. Cash-based payment and stock-based payment constitute the largest proportion

14

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

of total severance pay. Also, note that severance pay is significant when compared to alternative

forms of CEO compensation. In particular, contracted severance pay is, on average, 7.63 times

CEO salary, 4.20 times bonus, 3.53 times stock awards, and 4.51 times option awards. The sharp

contrast highlights the economic significance of severance pay in CEO compensation.

Panel B of Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for corporate tax planning, severance pay, firm

characteristics, and CEO characteristics for the full sample. Our two measures of effective tax rate,

GAAP and cash ETR, have mean values ranging from 26.06% to 29.68%, both of which fall below

the statutory tax rate of 35%. This suggests that, on average, firms engage in at least some degree

of tax planning. Table 2 reports Pearson and Spearman correlations for the sample. Total severance

pay (SERPAY) is negatively associated with our two primary measures of tax planning. These

univariate correlations support H1.

Baseline Results

Table 3 presents our baseline results. We focus on the coefficient estimate on SERPAY, which

captures the impact of CEO severance pay on corporate tax planning. The coefficient on SERPAY

is significantly negative for our two primary measures of tax planning. This result is also

economically significant. A one-standard-deviation increase in CEO severance pay relative to

CEO wealth is associated with a 0.90 percentage point reduction in GAAP ETR [4.4898 × (–

0.0020)] and a 0.90 percentage point reduction in Cash ETR [4.4898 × (–0.0020)]. These

correspond to a 3.03% reduction in GAAP ETR [0.0090/0.2968] and a 3.45% reduction in cash

ETR [0.0090/0.2606] for the average firm. These results are consistent with severance pay

encouraging managers to engage in tax planning. They are inconsistent with severance pay

15

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

reflecting management entrenchment, as entrenched managers would refrain from taking the same

amount of risk.11

The coefficients on control variables are consistent with the findings in prior research. Large

firms report higher ETRs, consistent with larger firms facing a higher political cost that serves as

a deterrent to tax planning (Zimmerman 1983). Profitable firms have higher effective tax rates,

consistent with the notion that such firms often fall into high tax brackets (Gupta and Newberry

1997). Highly leveraged firms have lower effective tax rates, consistent with such firms utilizing

the tax deduction on interest expense to avoid taxes (Mills, Erickson, and Maydew 1998).

Multinational firms avoid more taxes, consistent with multinational firms having more tax

planning opportunities (Rego 2003). Firms with large intangible assets have higher effective tax

rates, and firms with loss carry forwards experience lower effective tax rates, consistent with the

findings in Chen, Chen, Cheng, and Shevlin (2010). Older CEOs and shorter-tenured CEOs engage

less in tax planning, consistent with a manager effect as documented in Dyreng et al. (2008).

We find that the coefficient on vega is significantly negative in one specification. This finding

is consistent with vega increasing corporate tax planning (Rego and Wilson 2012). A one-standard

deviation increase in vega is associated with a 0.8 percentage point increase in GAAP ETR, and

this corresponds to a 2.7% increase in GAAP ETR for the average firm. In terms of economic

significance, severance pay is at least as important as vega in inducing corporate tax planning.

However, we also note that this result is not consistent across both specifications. One possible

reason for this lack of consistency is offered by Kahneman and Tversky (1979), whose prospect

11

According to SFAS No. 146, severance pay is expensed only when the termination arrangement is communicated

to managers. However, it is likely that the severance payment is made in a different year in which severance pay is

tax deductible. This way, severance pay can create a book-tax difference that causes a mechanical association between

severance pay and corporate tax planning. We believe that the mechanical association, if any, is most likely to be

evident around CEO turnover. We examine whether our results are sensitive to CEO turnover, and find that our results

continue to hold when we exclude 22 observations with CEO turnover from our sample. Thus, it is unlikely that our

results are driven by the potential book-tax difference created by severance payment upon CEO termination.

16

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

theory suggests that people care more about losses than gains. Thus, we might find a stronger

incentive effect for CEO severance pay that protects managers from losses rather than stock

options that only provide CEOs with upside gain potential. The result is also consistent with

Armstrong et al. (2015)’s argument that stock options only provide tax planning incentives for

extreme corporate planning activities. In untabulated quantile regressions, we find that VEGA is

significant at the 1% level at the tails of the distribution of corporate tax planning.

Severance Pay Components

One important feature of our hand-collected severance data is that we are able to examine the

components of severance pay. Through this feature, we are able to determine which component of

severance pay induces the incentive effect. We decompose the total amount of severance pay into

several components, including (1) the cash payment which involves salaries and bonuses, (2)

continuing healthcare and other benefits, (3) the immediate vesting of any unvested stock options

and awards, and (4) the vesting of previously unvested pension payments. For each component,

we scale the amount by the total amount of CEO severance pay in order to compare the relative

importance of each component. Untabulated results show that cash payment and stock

options/awards components positively affect corporate tax planning, whereas the healthcare and

pension benefits do not affect corporate tax planning.

Endogeneity

Propensity Score Matching

Omitted variables can bias our baseline estimation. One form of omitted variable bias arises

from functional form misspecification. More specifically, our baseline model might omit, for

example, a quadratic term of certain independent variables that simultaneously affect CEO

severance pay and corporate tax planning. This functional form misspecification can render our

17

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

focus variable SERPAY endogenous. To address this concern, we use a matched sample approach,

which imposes no assumptions on the functional form (Kothari, Leone, and Wasley 2005).

We follow Fang, Tian, and Tice (2014) to implement the propensity score matching. For each

year, we sort firms into terciles based on scaled CEO severance pay (SERPAY). Top tercile firms

are high severance pay firms while bottom tercile firms are low severance pay firms. Through

matching, we make high versus low severance pay firms more comparable on observables. We

construct an indicator variable to capture the likelihood of being a high severance pay firm. In the

first stage, we estimate a Probit model. We select matching variables based on Cadman et al. (2016)

who suggest that CEO severance pay should increase with CEO’s risk and the cost of dismissal.

Based on this theoretical argument, they predict that CEO severance pay should be higher when

(1) a CEO is hired from outside the firm, (2) a CEO owns less of the firm’s equity, (3) a CEO has

shorter tenure, (4) a CEO has signed a non-compete agreement, and (5) a CEO is far away from

retirement. Cadman et al. (2016) also include other CEO characteristics (CEO stock option vega

and delta) and firm characteristics (firm age, leverage, firm size, and the market-to-book assets

ratio) as determinants of CEO severance pay. We include all these variables as well as the

remaining control variables in our baseline regression in the first-stage Probit regression. We

impose a caliper distance of 0.03, which, according to Shipman, Swanquist, and Whited (2017), is

the most commonly used caliper distance in accounting research. We also impose a common

support requirement, restricting our attention to propensity scores falling in the common support

region. We perform the nearest neighbor matching without replacement, i.e., if a control firm is

matched to more than one treatment firm, we retain only the pair with the minimum distance in

propensity score. This matching without replacement results in 322 observations with 161 unique

pairs.

18

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

Table 4 presents the propensity score matching estimation results. Column (1) of Panel A

reports pre-matching Probit regression results. A CEO hired from outside the firm, holding less of

firm’s shares, and signing a non-compete agreement is more likely to receive higher severance

payment, consistent with Cadman et al. (2016). Some of the CEO and firm characteristics are also

predictors of a high severance payment. The pre-matching Probit regression has a pseudo-R2

equaling 0.34. Also, a χ2 test for model fitness has a p-value below 0.001. These results suggest

that these variables do well in explaining the probability of being a high severance pay firm.

Column (2) of Panel A reports post-matching Probit regression results. The coefficients on

independent variables become largely insignificant. The pseudo-R2 drops to 0.02 and χ2 test for

model fitness shows a p-value near 1. These results indicate a successful matching. Panel B

presents covariate balances. Before matching, we observe significantly large differences in CEO

and firm characteristics between high and low severance paying firms. After matching, high and

low severance paying firms become largely comparable, with all the differences in matching

variables being insignificant. Panel C estimates our baseline regression using the matched sample.

We find that the coefficient on SERPAY remains negative and significant for our effective tax rate

measures. Consequently, our baseline results are likely not influenced by potential functional form

misspecification.

Instrumental Variable Approach

We next use an instrumental variable approach. We use two instruments for CEO severance

pay. The selection of the instruments is based on the community effect of decision making. Prior

studies show that decision-makers located in the same community make similar decisions through

social interactions or information diffusion (Brown, Ivković, Smith, and Weisbenner 2008; Hong,

Kubik, and Stein 2005; Pool, Stoffman, and Yonker 2015). Therefore, we expect that a focal firm’s

19

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

CEO severance pay is affected by its community CEO severance pay. To capture this community

effect, we first calculate the geographic distance between a focal firm and the local largest

severance payer. We define communities at the city-level (Pool et al. 2015) and use firm

headquarter ZIP codes to pinpoint latitudes and longitudes. The Vincenty formula is applied to

calculate the geographic distance. Closer geographic proximity between a focal firm and its local

largest severance payer leads to a higher likelihood that this focal firm also exhibits a larger amount

of CEO severance pay. The second instrument we use is the community median CEO severance

pay. We expect that a focal firm’s severance pay increases with the community median severance

pay.

Table 5 presents the estimation results. Column (1) reports the first-stage regression results.

The dependent variable is CEO severance pay (SERPAY). The independent variables are the two

instruments (MSERPAY and DISTANCE) and all the controls from our baseline model. We find

that the coefficient on MSERPAY is significantly positive and that the coefficient on DISTANCE

is significantly negative. Therefore, CEO severance pay increases with its community median

severance pay and decreases with the geographic distance from the local largest severance payer,

supporting our predictions.

We next test for weak instruments. Valid instruments need to strongly predict severance pay.

We perform an F-test by excluding the two instruments from the first-stage regression. This yields

an F-statistic equaling 109.79, which is much higher than 10, the critical value for a weak

instrument F-statistic (Staiger and Stock 1997). We also perform a Stock and Yogo (2005) test to

verify the instrument strength. We derive a Cragg-Donald F-statistic equaling 1063.18 which

20

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

exceeds the critical value of 19.93 for weak instruments. 12 These results suggest that our

instruments are not weak. Thus, the instrumental variable estimates are unlikely to be biased

toward OLS estimates.

We also check whether our instruments satisfy the exclusion restriction condition. Valid

instruments should be exogenous. This requires that our instruments are not correlated with the

error term. As we use more than one instrument, we can check this through an over-identification

test. We derive a Hansen J-statistic equalling 0.132 which corresponds to a p-value of 0.7164.

There is no evidence that our instruments violate the exclusion restriction condition. Thus, our

instruments appear valid. In this sense, the instrumental variable estimates can capture a causal

effect of CEO severance pay on corporate tax planning.

Columns (2) - (3) of Table 5 report the second-stage instrumental variable estimation results.

The dependent variable is corporate tax planning, measured using GAAP and cash effective tax

rates. The main independent variable is the instrumented CEO severance pay, measured as the

predicted value from the first-stage estimation. We find that the coefficient on the instrumented

SERPAY remains significantly negative across both specifications, suggesting that the impact of

CEO severance pay on corporate tax planning is likely not due to correlated omitted variables.

Alternative Measures of Key Variables

We next consider alternative measures of CEO severance pay. In our initial design, we deflate

the total amount of CEO severance pay by a measure of CEO wealth, i.e., the market value of firm

equity shares held by the CEO (as in Cadman et al. 2016), to assess how significant the payment

amount is to the CEO’s overall net worth. Alternative scalars have been used in the prior literature

12

Stock and Yogo (2005) suggest that, for one endogenous regressor (n = 1) and two instruments (K = 2), the critical

value for weak instrument based on the maximum size bias at the 5% significance level is 19.93. Refer to Table 5.2

in Stock and Yogo (2005) for more details.

21

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

that, instead of focusing on CEO wealth, focus on CEO annual compensation. Consequently, we

assess whether our baseline results are sensitive to using CEO annual cash compensation (salary

and bonus) and annual total compensation as scalers of CEO severance pay. Columns (1) – (4) of

Table 6, Panel A report the results. We find that the coefficient on severance pay remains (at least

marginally) significantly negative for three of the four columns. Therefore, our baseline results

appear relatively robust to alternative scalers.

Our severance pay variable is a continuous variable that covers both severance paying firms

and non-severance paying firms, and this raises the question of whether our results are driven by

a self-selection bias. When we partition only on severance paying firms, we find similar results

(Columns (5) - (6) of Table 6, Panel A). Consistent with Cadman et al. (2016), these results suggest

that it is the amount of severance pay that matters, not simply the existence. These patterns also

suggest that our results are not driven by selection differences between firms that provide

severance pay and firms that do not provide severance pay. Finally, we create a severance pay

indicator variable that equals 1 for severance paying firms to test whether the existence of

severance pay (rather than the amount) has an impact on tax planning activities. We find at least

marginally significant results across both ETR measures (Columns (7)-(8) of Table 6, Panel A),

suggesting that the existence of severance also plays a role in incremental tax planning activities.

In addition, we consider alternative measures to capture the level of corporate tax planning.

First, we use tax settlements with the Internal Revenue Service. Specifically, TAXSETTLE is

defined as the natural logarithm of tax settlements attributable to unrecognized tax benefits plus

one, with missing values set to zero. Column (1) of Table 6, Panel B shows that CEO severance

pay is positively associated with tax settlements, supporting that severance contracts encourage

managers to engage in incremental tax planning. We also use unrecognized tax benefits to measure

22

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

corporate tax planning. UTB is defined as the natural logarithm of year-end unrecognized tax

benefits plus one, with missing values set to zero. CEO severance pay is positively associated with

the amount of unrecognized tax benefits (Column (2) of Table 6, Panel B).13 This finding is also

consistent with severance pay being associated with incremental tax planning. Untabulated results

suggest that these alternative tax measures survive both the propensity score matching approach

and the instrumental variable estimation.

TESTING FOR THE MECHANISM

In this section, we test for the mechanism through which we expect CEO severance pay affects

corporate tax planning. If our theoretical argument holds, we would find that CEO severance pay

provides stronger tax planning incentives when managers face greater career concerns.

Accordingly, we conduct cross-sectional tests related to managerial career concerns. Throughout

these cross-sectional tests, we use the severance pay variable derived from the instrumental

variable estimation to quantify CEO severance pay.14

CEO Tenure

CEO tenure can capture managerial career concerns. There is evidence that long-tenured

managers face a low risk of forced turnover (Goyal and Park 2002). One possible reason is that

long-tenured managers have more knowledge about a firm’s environment and are more

experienced in dealing with uncertainty (Simsek 2007). Another reason is that, over time,

managers have accumulated more power and thus are less likely to be fired (Goyal and Park 2002).

Consequently, we use CEO tenure to infer career concerns. We expect that our results are more

13

A one-standard-deviation increase in severance pay is associated with a 5 percentage point increase in log-

transformed tax settlements (0.0119×4.4898). This corresponds to a 10% increase in log-transformed tax settlements

for the average firm (0.0119×4.4898/0.5001). Also, a one-standard-deviation increase in severance pay is associated

with a 9 percentage point increase in log-transformed UTB (0.0211×4.4898). This corresponds to a 5% increase in

log-transformed UTB for the average firm (0.0211×4.4898/1.8808).

14

We also perform OLS and propensity score matching estimations of the cross-sectional tests. Results remain

unchanged.

23

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

pronounced for short-tenured CEOs who likely face greater career concerns.

We use an indicator variable to capture short-tenured versus long-tenured CEOs. Short-tenured

CEOs are defined as those who are early in their tenure (i.e., bottom quartile of tenure). Long-

tenured CEOs are those who have a long tenure (i.e., top quartile of tenure). We create an indicator

variable LOWTENURE that equals 1 for short-tenured CEOs and 0 for long-tenured CEOs. We

use the interaction term between instrumented CEO severance pay and CEO tenure indicator

(SERPAY*LOWTENURE) to examine how CEO tenure affects the association between CEO

severance pay and corporate tax planning. Panel A of Table 7 reports the results. For brevity, we

only report variables of interest. Consistent with expectations, we find that the coefficient on the

interaction SERPAY*LOWTENURE is significantly negative across both ETR specifications. This

suggests that CEO severance pay motivates short-tenured CEOs to take risky tax positions.

Shareholder Rights

Next, we use shareholder rights to capture managerial career concerns. Strong shareholder

rights often impose intense shareholder monitoring on managers and are thus effective in replacing

managers (Yermack 2006). We use the governance index (G-index) developed by Gompers, Ishii,

and Metrick (2003) to measure shareholder rights, as in Chava, Livdan, and Purnanandam (2008).

The G-index is constructed based on 24 governance provisions. A low G-index indicates strong

shareholder rights and therefore greater managerial career concerns.

We use an indicator variable to capture strong versus weak shareholder rights. Firms with strong

shareholder rights are defined as those with low G-index (i.e., bottom quartile of G-index). Firms

with weak shareholder rights are those with high G-index (i.e., top quartile of G-index). We create

an indicator variable HIGHRIGHTS that equals 1 for firms with strong shareholder rights and 0

for firms with weak shareholder rights. We use the interaction term between instrumented CEO

24

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

severance pay and shareholder rights (SERPAY*HIGHRIGHTS) to determine how shareholder

rights affect the association between CEO severance pay and corporate tax planning. Panel B of

Table 7 reports the results. Consistent with expectations, we find that the coefficient on the

interaction SERPAY*HIGHRIGHTS is significantly negative for cash ETR. This suggests that

CEO severance pay motivates managers under intense shareholder monitoring to take risky tax

positions.

Idiosyncratic Volatility

Finally, we use firm idiosyncratic volatility as a third proxy for managerial career concerns.

Managers are expected to have greater career concerns when firms’ operations are more volatile

(Rau and Xu 2013). Consistent with this notion, Bushman, Dai, and Wang (2010) find that the

likelihood of CEO turnover increases in firm idiosyncratic volatility. As a result, managers face

greater career concerns when firms exhibit higher idiosyncratic volatility. We measure

idiosyncratic volatility as the standard deviation of the idiosyncratic regression residuals derived

from regressing a firm’s weekly stock returns on value-weighted industry and market weekly

returns (Crawford, Roulstone, and So 2012). A higher value of the standard deviation of the

idiosyncratic regression residuals indicates higher idiosyncratic volatility.

We use an indicator variable to capture high versus low idiosyncratic volatility. Firms with

high idiosyncratic volatility are those with more volatile idiosyncratic regression residuals (i.e.,

top quartile of idiosyncratic volatility). Firms with low idiosyncratic volatility are those with less

volatile idiosyncratic regression residuals (i.e., bottom quartile of idiosyncratic volatility). We use

the interaction term between instrumented CEO severance pay and idiosyncratic volatility

indicator (SERPAY*HIGHIVOL) to determine how idiosyncratic volatility affects the association

between CEO severance pay and corporate tax planning. Panel C of Table 7 reports the results.

25

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

Consistent with expectations, we find that the coefficient on the interaction SERPAY*HIGHIVOL

is significantly negative in two specifications. This suggests that CEO severance pay encourages

more corporate tax planning when managers operate in firms with high idiosyncratic volatility.

Principal Component Analysis

We conduct a principal component analysis of the above three measures of career concerns. We

multiply CEO tenure and shareholder rights by negative one so that all three measures are

increasing in career concerns. The first principal component explains around 40% of the variation

in three measures of career concerns. The first and the second principle components together

explain more than 70% of the variation in three measures. Both the first and the second principle

components have eigenvalues greater than one. Panels D, E, and F of Table 7 re-estimate the

regression using the first principal component, the second principal component, and the average

of the first and second principal components, respectively. Consistent with expectations, we find

that the coefficients on the three interactions, SERPAY*FIRSTPRIN, SERPAY*SECONDPRIN,

and SERPAY*AVGPRIN, are all significantly negative across both ETR specifications.

To summarize, we find that CEO severance pay provides stronger tax planning incentives to

managers when managers are expected to have greater career concerns (i.e., when they are short-

tenured, when they face strong shareholder monitoring, and when they operate firms with high

idiosyncratic volatility). These results are consistent with career concerns being a mechanism

underlying the association between CEO severance pay and corporate tax planning.

CONCLUSION

We examine the association between CEO severance pay (i.e., payment a CEO would receive

if s/he is involuntarily terminated) and corporate tax planning activities. We find that CEO

severance pay increases corporate tax planning, consistent with CEO severance pay providing

26

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

contractual protection against managers’ career concerns and thereby inducing otherwise risk-

averse managers to engage in incremental tax planning. This result continues to hold under an

instrumental variable approach and a propensity score matching and survives alternative measures

of CEO severance pay and corporate tax planning. Finally, we find that severance pay provides

stronger tax planning incentives in situations where managers are expected to have greater career

concerns– i.e., when they are short-tenured, when they face strong shareholder monitoring, and

when they operate firms with high idiosyncratic volatility. Overall, our results suggest that CEO

severance pay represents a form of efficient contracting with otherwise risk-averse managers in

that it encourages incremental tax risk-taking.

27

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

References

Allingham, M. G., and Sandmo, A. 1972. Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Public

Economics 1: 323–338.

Almazan, A., and Suarez, J. 2003. Entrenchment and severance pay in optimal governance structures. The

Journal of Finance 58: 519–547.

Armstrong, C. S., Blouin, J. L., Jagolinzer, A. D., and Larcker, D. F. 2015. Corporate governance,

incentives, and tax avoidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics 60: 1–17.

Austin, C. R., and Wilson, R. J. 2017. An examination of reputational costs and tax avoidance: Evidence

from firms with valuable consumer brands. The Journal of the American Taxation Association, 39: 67-

93.

Baginski, S. P., Campbell, J. L., Hinson, L. A., and Koo, D. 2018. Do career concerns affect the delay of

bad news disclosure? The Accounting Review 93 (2), 61–95.

Blaylock, B.S. 2016. Is tax avoidance associated with economically significant rent extraction among US

firms? Contemporary Accounting Research 33: 1013-1043.

Bozanic, Z., Hoopes, J. L., Thornock, J. R., and Williams, B. M. 2017. IRS attention. Journal of Accounting

Research 55, 79-114.

Brown, J. R., Ivković, Z., Smith, P. A., and Weisbenner, S. 2008. Neighbors matter: Causal community

effects and stock market participation. The Journal of Finance 63: 1509–1531.

Brown, K., Jha, R., and Pacharn, P. 2015. Ex ante CEO severance pay and risk-taking in the financial

services sector. Journal of Banking and Finance 59: 111–126.

Brown, K., W. Dong, and Y. Ke. 2016. Ex ante severance agreements and tax avoidance. Working paper,

Brock University.

Bushman, R., Dai, Z., and Wang, X. 2010. Risk and CEO turnover. Journal of Financial Economics 96,

381-398.

Cadman, B. D., Campbell, J. L., and Klasa, S. 2016. Are ex-ante CEO severance pay contracts consistent

with efficient contracting? Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 51: 737–769.

Chava, S., Livdan, D., and Purnanandam, A. 2008. Do shareholder rights affect the cost of bank loans? The

Review of Financial Studies 22, 2973-3004.

Chen, K.-P., and Chu, C. Y. C. 2005. Internal control versus external manipulation: A model of corporate

income tax evasion. The RAND Journal of Economics 36: 151–164.

Chen, S., Chen, X., Cheng, Q., and Shevlin, T. 2010. Are family firms more tax aggressive than non-family

firms? Journal of Financial Economics 95: 41–61.

Chen, S., Powers, K., and Stomberg, B. 2016. Examining the role of the media in influencing corporate tax

avoidance and disclosure. SSRN working paper.

Chen, X., Cheng, Q., Lo, A. K., and Wang, X. 2015. CEO contractual protection and managerial short-

termism. The Accounting Review 90: 1871–1906.

Christensen, D. M., Dhaliwal, D. S., Boivie, S., and Graffin, S. D. 2015. Top management conservatism

and corporate risk strategies: Evidence from managers' personal political orientation and corporate tax

avoidance. Strategic Management Journal 36: 1918–1938.

Chyz, J. A. 2013. Personally tax aggressive executives and corporate tax sheltering. Journal of Accounting

and Economics 56: 311–328.

Chyz, J. A., and Gaertner, F. 2018. Can paying “too much” or “too little” tax contribute to forced CEO

turnover? The Accounting Review 93, 103-130.

Crawford, S. S., Roulstone, D. T., and So, E. C. 2012. Analyst initiations of coverage and stock

return synchronicity. The Accounting Review 87: 1527-1553.

Crocker, K. J., and Slemrod, J. 2005. Corporate tax evasion with agency costs. Journal of Public Economics

89: 1593–1610.

Desai, M. A., and Dharmapala, D. 2006. Corporate tax avoidance and high-powered incentives. Journal of

Financial Economics 79: 145–179.

Dyreng, S. D., Hanlon, M., and Maydew, E. L. 2008. Long-run corporate tax avoidance. The Accounting

28

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

Review 83: 61–82.

Dyreng, S. D., Hanlon, M., and Maydew, E. L. 2010. The effects of executives on corporate tax avoidance.

The Accounting Review 85: 1163–1189.

Dyreng, S. D., Hanlon, M., and Maydew, E. L. 2018. When does tax avoidance result in tax

uncertainty? The Accounting Review, forthcoming.

Ehinger, A., Lee, J. A., Stomberg, B., and Towery, E. 2017. Let's talk about tax: The determinants and

consequences of income tax mentions during conference calls. SSRN working paper.

Fang, V. W., Tian, X., and Tice, S. 2014. Does stock liquidity enhance or impede firm innovation? The

Journal of Finance 69: 2085–2125.

Fiegerman, S. 2010. “Outrageous CEO severance payouts.” Published on August 16, 2010. Accessed on

September 15, 2018 at: https://www.thestreet.com/slideshow/12816598/1/infamous-ceo-severance-

payouts.html.

Gaertner, F. 2014. CEO after-tax compensation incentives and corporate tax avoidance. Contemporary

Accounting Research 31: 1077–1102.

Gallemore, J., and E. Labro. 2015. The Importance of the Internal Information Environment for Tax

Avoidance. Journal of Accounting and Economics 60: 149–167.

Gallemore, J., Maydew, E. L., and Thornock, J. R. 2014. The reputational costs of tax

avoidance. Contemporary Accounting Research 31, 1103-1133.

GMI Rating (GMI). 2013. 2013 CEO pay survey.

Goh, B., Lee, J., Lim, C., and Shevlin, T. 2016. The effect of corporate tax avoidance and cost of equity.

The Accounting Review 91: 1647–1670.

Gompers, P., Ishii, J., and Metrick, A. 2003. Corporate governance and equity prices. Quarterly Journal of

Economics 118: 107–155.

Goyal, V. K., and Park, C. W. 2002. Board leadership structure and CEO turnover. Journal of Corporate

Finance 8: 49–66.

Graham, J.R., Hanlon, M., Shevlin, T., and Shroff, N. 2014. Incentives for tax planning and avoidance:

Evidence from the field. The Accounting Review 89: 991–1023.

Gupta, S., and Newberry, K. 1997. Determinants of the variability in corporate effective tax rates: Evidence

from longitudinal data. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 16: 1–34.

Hanlon, M., and Heitzman, S. 2010. A review of tax research. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50:

127–178.

Hanlon, M., and Slemrod, J. 2009. What does tax aggressiveness signal? Evidence from stock price

reactions to news about tax shelter involvement. Journal of Public Economics, 93(1-2), 126-141.

Hirshleifer, D. 1993. Managerial reputation and corporate investment decisions. Financial Management,

145-160.

Hong, H., Kubik, J. D., and Stein, J. C. 2005. Thy neighbor's portfolio: Word of mouth effects in the

holdings and trades of money managers. The Journal of Finance 60: 2801–2824.

Internal Revenue Service (IRS). 2014. Internal Revenue Service Data Book, 2014. Internal Revenue Service:

Washington, DC.

Jensen, M. C., and Meckling, W. H. 1976. Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and

ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–360.

Ju, N., Leland, H., and Senbet, L. W. 2014. Options, option repricing in managerial compensation: Their

effects on corporate risk. Journal of Corporate Finance 29: 628–643.

Kahneman, D., and Tversky, A. 1979. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica

47:263-91.

Kothari, S. P., Leone, A. J., and Wasley, C. E. 2005. Performance matched discretionary accrual measures.

Journal of Accounting and Economics 39: 163–197.

Kubick, T. R., Lynch, D. P., Mayberry, M. A., and Omer, T. C. 2016. The effects of regulatory scrutiny on

tax avoidance: An examination of SEC comment letters. The Accounting Review 91, 1751-1780.

Lennox, C., Lisowsky P., and Pittman, J. 2013. Tax aggressiveness and accounting fraud. Journal of

Accounting Research 51: 739–778.

29

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

Merton, R. C. 1973. Theory of rational option pricing. The Bell Journal of Economics and Management

Science 4: 141–183.

Mills, L. F., Erickson, M. M., and Maydew, E. L. 1998. Investments in tax planning. Journal of the

American Taxation Association 20: 1–20.

Nessa, M., C. Schwab, B. Stomberg, and E. Towery. 2016. How do IRS resources affect the tax enforcement

process? Working paper, Indiana University.

Phillips, J. 2003. Corporate tax planning effectiveness: The role of compensation-based incentives. The

Accounting Review 78: 491–521.

Pool, V. K., Stoffman, N., and Yonker, S. E. 2015. The people in your neighborhood: Social interactions

and mutual fund portfolios. The Journal of Finance 70: 2679–2732.

Powers, K., Robinson, J. R., and Stomberg, B. 2016. How do CEO incentives affect corporate tax planning

and financial reporting of income taxes? Review of Accounting Studies 21: 672–710.

Rau, P. R., and Xu, J. 2013. How do ex ante severance pay contracts fit into optimal executive incentive

schemes? Journal of Accounting Research 51: 631-671.

Rego, S. O. 2003. Tax-avoidance activities of U.S. multinational corporations. Contemporary Accounting

Research 20: 805–833.

Rego, S. O., and Wilson, R. 2012. Equity risk incentives and corporate tax aggressiveness. Journal of

Accounting Research 50: 775–810.

Robinson, J.R., Sikes, S.A. and Weaver, C.D. 2010. Performance measurement of corporate tax

departments. The Accounting Review 85:1035–1064.

Ross, S. A. 2004. Compensation, incentives, and the duality of risk aversion and riskiness. The Journal of

Finance 59: 207–225.

Shevlin, T. 2007. The future of tax research: from an Accounting professor’s perspective. Journal of the

American Taxation Association 29: 87–93.

Shipman, J. E., Swanquist, Q. T., and Whited, R. L. 2017. Propensity score matching in accounting

research. The Accounting Review 92, 213-244.

Simsek, Z. 2007. CEO tenure and organizational performance: An intervening model. Strategic

Management Journal 28: 653–662.

Slemrod, J. 2004. The economics of corporate tax selfishness. National Tax Journal 57: 877–899.

Staiger, D., and Stock, J. H. 1997. Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica

65: 557–586.

Stock, J. H., and Yogo, M. 2005. Testing for Weak Instruments in Linear IV Regression: in Donald Andrews

and James Stocks, eds: Identification and inference for econometric models, Cambridge University Press,

New York, NY.

Wilson, R. J. 2009. An examination of corporate tax shelter participants. The Accounting Review 84: 969–

999.

Yermack, D. 2006. Golden handshakes: Separation pay for retired and dismissed CEOs. Journal of

Accounting and Economics 41, 237-256.

Zimmerman, J. L. 1983. Taxes and firm size. Journal of Accounting and Economics 5: 119–149.

30

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2802426

APPENDIX A

Variable Definition

Variable Definition Compustat

Panel A CEO severance pay and corporate tax planning

Dependent variables

GAAP GAAP effective tax rate, measured as total tax expense over pre-tax book income TXT/(PI-SPI)

less special items.

CASH Cash effective tax rate, measured as cash taxes paid over pre-tax book income less TXPD/(PI-SPI)

special items.

Main independent variable

SERPAY CEO severance pay, measured as the contracted total severance payment amount to Hand-collected

a firm's CEO as disclosed in the 10-K report over the market value of firm equity severance/

shares held by the CEO. (SHROWN_EXCL

_OPTS*PRCC_F)

Control variables at the firm level

SIZE Firm size, measured as the logarithm transformed total assets. AT

ROA Firm profitability, measured as earnings before extraordinary items over total assets. IB/AT

LEV Firm leverage, measured as current debt plus long-term debt over total assets. (DLC+DLTT) /AT

MB Market-to-book ratio, measured as the market value of equity over the book value of (CSHO×PRCC_F)/

equity. CEQ

FIRMAGE Firm age, measured as the difference between the current year and the year a firm

first appears on Compustat.

MNE Multinationality, measured as an indicator variable that equals 1 for firms with pre- PIFO

tax foreign income and 0 otherwise.

RD R&D intensity, measured as R&D expenditure over sales. XRD/SALE

CAPX Firm investment, measured as capital expenditure over net property, plant, and CAPX/PPENT

equipment.

PPE Capital intensity, measured as net property, plant, and equipment over total assets. PPENT/AT

INTANG Asset tangibility, measured as intangible assets over total assets. INTAN/AT

EQINC Equity income, measured as equity income in earnings over total assets. ESUB/AT

NOL Loss carry forward, measured as an indicator variable that equals 1 for firms with TLCF

positive loss carry forward and 0 otherwise.

DNOL Change in loss carry forward, measured as changes in loss carry forward over total TLCF/AT

assets.

Control variables at the manager level

CEOAGE CEO age, measured as the age of the CEO of a firm. ExecuComp

CEOTENURE CEO tenure, measured as the number of years since a CEO has been in office. ExecuComp

MSHARE Managerial stock ownership, measured as the CEO shareholding percentage. ExecuComp

VEGA Option Vega, measured as change in the value of the CEO's stock options and

holdings for a one percent increase in stock return volatility, scaled by 1,000.

DELTA Option Delta, measured as change in the value of the CEO's stock options and

holdings for a one percent increase in stock price, scaled by 1,000.

Panel B Sensitivity tests and further tests

Instruments for CEO severance pay

DISTANCE Geographic distance to community largest severance payer, measured as the

geographic distance in miles between a firm and its city’s largest severance payer.

MSERPAY Community median severance pay, measured as the city’s median CEO severance

pay.

Propensity score matching variables

OUTSIDE Outside CEO, an indicator variable equal to 1 if a CEO is hired outside of a firm and Hand-collected

0 otherwise.