Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Yang2018 - Skizofrenia Referat

Yang2018 - Skizofrenia Referat

Uploaded by

Febelina IdjieOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Yang2018 - Skizofrenia Referat

Yang2018 - Skizofrenia Referat

Uploaded by

Febelina IdjieCopyright:

Available Formats

Polypharmacy and psychotropic drug loading in patients with schizophrenia in

Asian countries: The REAP-AP4 study

Shu-Yu Yang, PhD,1 Lian-Yu Chen, MD, PhD,1 Eunice Najoan, MD,2 Roy Abraham

Kallivayalil, MD,3 Kittisak Viboonma, MD,4 Ruzita Jamaluddin, MD,5 Afzal Javed,

MD,6 Duong Thi Quynh Hoa, MD,7 Hitoshi Iida, MD,8 Kang Sim, MD,9 Thiha Swe,

MD,10 Yan-Ling He, MD,11 Yongchon Park, MD,12 Helal Uddin Ahmed, MD,13

Angelo De Alwis, MD,14 Helen Fung-Kum Chiu, MD,15 Norman Sartorius, MD,

PhD,16 Chay-Hoon Tan, MD,17 Mian-Yoon Chong, MD, PhD,18 Naotaka Shinfuku,

Accepted Article

MD, PhD,19 Shih-Ku Lin, MD,1,20*

1

Taipei City Hospital and Psychiatric Center, Taipei, Taiwan, 2Mintoharjo Hospital,

Jakarta, Indonesia, 3Pushpagiri Institute of Medical Sciences, Tiruvalla, Kerala,

India, 4Suanprung Psychiatric Hospital, Chian Mai, Thailand, 5Department of

Psychiatry & Mental Health, Hospital Tuanku Fauziah, Kangar, Perlis, Malaysia, 6

Pakistan Psychiatric Research Centre, Fountain House, Lahore, Pakistan, 7Thanh

Hoa Provincial Psychiatric Hospital, Thanh Hoa, Vietnam, 8Department of

Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Fukuoka University, Fukuoka, Japan, 9Institute of

Mental Health, Buangkok Green Medical Park, Singapore, 10 Department of Mental

Health, University of Medicine, Magway, Myanmar, 11Department of Psychiatric

Epidemiology, Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai, China, 12Department of

Psychiatry, Hanyang University, Seoul, Korea, 13National Institute of Mental Health,

Dhaka, Bangladesh, 14National Institute of Mental Health, Angoda, Sri Lanka,

15

Department of Psychiatry, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR,

China, 16Association for the Improvement of Mental Health Programs, Geneva,

Switzerland, 17National University of Singapore, Singapore.18Chiayi Chang Gung

Memorial Hospital and School of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Chiayi, Taiwan,

19

School of Human Sciences, Seinan Gakuin University, Fukuoka, Japan,

20

Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei,

Taiwan

*

Correspondence: Shih-Ku Lin, MD, Taipei City Hospital and Psychiatric Center

309 Songde Road, Taipei 110, Taiwan. E-mail: sklin@tpech.gov.tw

Tel: +88627263141

Running Title: Polypharmacy and PDL in REAP-AP4

This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not

been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process, which

may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this

article as doi: 10.1111/pcn.12676

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Abstract

Aim: The aim of the present study was to survey the prevalence of antipsychotic

polypharmacy and combined medication use across 15 Asian countries and areas in

Accepted Article

2016.

Methods: By using the results from the fourth survey of Research on Asian

Prescription Patterns on antipsychotics (REAP-AP4), the rates of polypharmacy and

combined medication use in each country were analyzed. Daily medications

prescribed for the treatment of inpatients or outpatients with schizophrenia,

including antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, anxiolytics, hypnotics, and antiparkinson

agents, were collected. Fifteen countries from Asia participated in this study.

Results: A total of 3744 patients’ prescription form were examined. The prescription

patterns differed across these Asian countries, with the highest rate of polypharmacy

noted in Vietnam (59.1%) and the lowest in Myanmar (22.0%). Furthermore, the

highest rate and the lowest rate of combined use of mood stabilizers was China

(35.0%) and Bangladesh (1.0%), antidepressants South Korea (36.6%) and

Bangladesh (0%), anxiolytics Pakistan (55.7%) and Myanmar (8.5%), hypnotics

Japan (61.1%) and Myanmar and Sri Lanka (0%), and antiparkinson agents

Bangladesh (87.9%) and Vietnam (10.9%), respectively. The average psychotropic

drug loading of all patients was 2.01 ± 1.64, with the highest and lowest loadings

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

noted in Japan (4.13 ± 3.13) and Indonesia (1.16 ± 0.68), respectively.

Conclusion: Differences in psychiatrist training as well as the civil culture and

health insurance system of each country may have contributed to the differences in

Accepted Article

these rates. The concept of drug loading can be applied to other medical field.

Key words: antipsychotic loading, combined medication, polypharmacy,

psychotropic drug loading, schizophrenia

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Introduction

The term polypharmacy is originally coined to refer to problems related to multiple

drug consumption and excessive drug use during treatment of a disease or disorder.1

Accepted Article

In the treatment of schizophrenia, polypharmacy usually refers to the simultaneous

use of two or more antipsychotic medications, and combined (adjunct) medications

as the use of mood stabilizers, antidepressants, anxiolytics, or hypnotics in addition

to single or multiple antipsychotics. Ideally, a clinician should administer

monotherapy of an antipsychotic to treat schizophrenia; however, some proportions

of patients respond to this treatment suboptimally.2 Thus, polypharmacy and

combined medications are frequently applied in clinical practice. The prevalence of

polypharmacy varies among countries: It is lower in North American countries, such

as the United States3-5 and Canada,6 and Europe such as United Kingdom,7 but higher

in Asian countries, such as Japan and Singapore.8, 9 Because it is expensive with

unproven efficacy and several side effects, the use of antipsychotic polypharmacy

used to be discouraged and avoided.10 However, recent data suggested that

antipsychotic polypharmacy and combined medications has been shown to be

helpful in some patients.11, 12

The Research on Asian Prescription Patterns (REAP) is an international

collaborative consortium for studying prescription patterns of psychotropic drugs

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

across countries. This consortium has conducted three surveys on antipsychotics

(REAP-AP1, -AP2, and -AP3 in 2001, 2004, and 2009, respectively) and two on

antidepressants (REAP-AD1 and -AD2 in 2004 and 2013, respectively;

Accepted Article

http://reap.asia/index.html). The rate of antipsychotic polypharmacy has been

reported in previous surveys.8, 13 The present study was the fourth REAP survey on

antipsychotics (REAP-AP4), and we report herein on the prevalence of

antipsychotic polypharmacy and combined medication use across 15 Asian countries

and areas.

Methods

Design and participants

For data collection, this study used an online website-based data key-in system. The

research protocol can be accessed at http://reap.asia/reap_ap.html#reap_ap4. In brief,

data on the daily medications prescribed for treating inpatients or outpatients with

schizophrenia, including antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, antidepressants,

anxiolytics, hypnotics, and antiparkinson agents, and demographics were collected.

Fifteen Asian countries and areas, namely China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea,

Singapore, Taiwan (REAP-AP1–3), India, Thailand, Malaysia (REAP-AP3),

Bangladesh, Indonesia, Myanmar, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam, participated in

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

this study, which took place between March 1, 2016 and May 31, 2016. Because no

established definition of polypharmacy has been reported,14 here we referred to

polypharmacy as the use of two or more antipsychotics, and combined medications

Accepted Article

as the additional use of other psychotropic drugs in the treatment of schizophrenia.

The use of a long-acting injectable antipsychotic combined with the same drug in

oral form was considered monotherapy. The prevalence of antipsychotic

polypharmacy and combined medications of each psychotropic drug were analyzed.

Conventionally, a chlorpromazine equivalent is used to compare the therapeutic

dose of an antipsychotic.15-17 Because newer antipsychotics, such as iloperidone,

lurasidone, and paliperidone, do not have a chlorpromazine equivalent,18 the defined

daily dose (DDD) system is a useful and reliable tool for international drug

utilization studies19 for comparison with either other antipsychotics alone or

combined with other medications. Here, the antipsychotic loading index was

calculated using the sum of the prescribed daily dose (PDD) of each antipsychotic,

divided by its DDD to indicate the quantity of antipsychotic drugs received by a

patient. Accordingly, psychotropic drug loading (PDL) was used to represent the

medication quantity prescribed to treat a mental disorder. For schizophrenia,

psychotropic drugs comprise five pharmacological classes of drugs, namely

antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and hypnotics; these

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

drugs are administered to treat the core and peripheral schizophrenia symptoms,

such as delusions, hallucinations, agitated or aggressive behaviors, anxious or

depressive mood, and insomnia. PDL is the sum of each psychotropic drug’s PDD

Accepted Article

divided by its DDD in the five pharmacological classes. Based on the dose

information obtained from the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC)

Classification System (i.e., the ATC/DDD Index 2016), DDD was considered to be

the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main

indication in an adult weighing 70 kg (https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/

[accessed 15 September 2016]).20 The ATC/DDD system is a tool used for

exchanging and comparing data on drug use at international, national, or local levels

and has become the gold standard for international drug utilization research. For

instance, if a patient receives a daily dose of aripiprazole 15 mg, valproic acid 750

mg, and lorazepam 2 mg, the PDL will be (15/15) +(750/1500) + (2/2.5) = 2.3. We

calculated the PDL of each enrolled patient and compared the results between

countries.

This REAP-AP4 study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB)

of Taipei City Hospital (TCHIRB-10412128-E) for data collection in this hospital

and management of all data sets. For remaining regions, IRB approval was obtained

from individual study sites.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Statistical analyses

We used SPSS for Windows (version 20; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for

Accepted Article

computing study data. Here, the samples are reported as numbers and percentages as

well as means ± standard deviations (SDs). A chi-square test was then used to

compare the four cohorts of the REAP-AP. Statistical significance was set at p <

0.05.

Results

In total, 3744 patients with schizophrenia (1950 inpatients, 1794 outpatients; 2200

men) were enrolled. The numbers and demographics of each country are presented

in Table 1, where countries are listed in order of the number of patients enrolled. The

mean age was 39.5 ± 13.1 years, with the oldest patients in Singapore (48.1 ± 13.7

years) and the youngest in Bangladesh (31.9 ± 11.0 years). The mean body weight

was 62.9 ± 13.8 kg, with highest patient weights in Hong Kong (71.8 ± 15.4 kg) and

the lowest in Bangladesh (52.2 ± 12.4 kg). The mean body mass index was 23.8 ±

4.6.

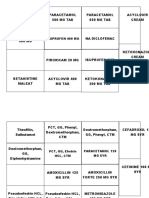

Table 2 shows the numbers and rates of antipsychotic polypharmacy and

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

combined medication use in each country, with the red and blue cells containing

more than and less than 1 SD, respectively. The antipsychotic polypharmacy rate

ranged from 22.0% (Myanmar) to 59.1% (Vietnam), with a mean rate of 42.2% ±

Accepted Article

12.0%. The mean number of antipsychotics used was 1.5 ± 0.6, with the highest

numbers obtained from Japan (1.8 ± 0.9) and the lowest numbers obtained from

Myanmar (1.2 ± 0.4). The most used antipsychotic was risperidone (36.9%),

followed by olanzapine (20.5%), clozapine (18.5%), haloperidol (15.5%),

chlorpromazine (8.4%), quetiapine (7.9%), aripiprazole (5.6%), and trifluoperazine

(4.0%).

Notably, there was a large variation in the rates of combined medication use

across countries. A comparison of the polypharmacy and drug loading between

inpatients and outpatients is outlined in Table 3.

Figure 1 illustrates the comparison of polypharmacy rates across countries,

from the REAP-AP1 to REAP-AP48, and Figure 2 depicts the comparison of PDL

and antipsychotic loading between the countries. The mean PDL of all patients was

2.01 ± 1.64, with the highest and lowest loadings occurring in Japan (4.1.3 ± 3.13)

and Indonesia (1.16 ± 0.68), respectively.

Discussion

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

The mean rate of antipsychotic polypharmacy in Asian countries was 42.2%

(although with considerable variation among the countries), indicating that

Accepted Article

polypharmacy is still widely prescribed for patients with schizophrenia in these

locations compared with Western countries.5-7

Compared with previous REAP-AP surveys8 (45.6% in 2001, 37.4% in 2004,

42.3% in 2009), the rate here showed no apparent significant change. However,

during the course of the four surveys, the rate has consistently decreased to 55.0%

from 78.1% in Japan (χ2 = 60.8, df = 3), to 52.6% from 70.3% in Singapore (χ2 =

22.9, df =3) and to 25.7% from 45.9% in India (χ2 = 24.9, df = 1; all p < 0.001). In

Japan, the use of high doses of antipsychotics and polypharmacy has been

conventionally prevalent.21, 22 To reduce the high rate of polypharmacy, psychotropic

dose equivalence has been suggested for dose standardization; in addition, the public

insurance reimbursement system, drug reduction program, and pharmacist

intervention policies have been revised to improve and prevent psychotropic

polypharmacy.23-25 Our results indicated that the rate of polypharmacy has reduced in

recent years in Japan; nevertheless, among the Asian countries included here, Japan

still has the highest average number of antipsychotic use (1.8 ± 0.9) and

antipsychotic loading (2.29 ± 1.79).

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Notably, the rate of polypharmacy increased only in China, from 25.0% in 2001,

23.2% in 2006, and 35.7% in 2009, to 52.5% in 2016 (χ2 = 63.4, df = 3, p < 0.001).

In a series survey, the frequency of polypharmacy significantly increased from

Accepted Article

26.1% (2002) and 26.4% (2006) to 34.2% in 2012 (p < 0.001) in China.26 The data

analysis in that study revealed that polypharmacy-administered patients and their

families had lower satisfaction with treatment, higher mental quality of life, earlier

onset age, more side effects, and higher antipsychotic doses; the patients were also

more likely to receive first-generation antipsychotics, but less likely to receive

benzodiazepines.

The mean antipsychotic loading was 1.50 ± 1.15 in all patients, which was

approximately equal to chlorpromazine (DDD, 300 mg) 450 mg/day or risperidone

(DDD, 5 mg) 7.5 mg/day. After further stratification (Table 3), inpatients (n = 1950)

showed a significantly higher rate of polypharmacy (49.1%), higher antipsychotic

loading, and more psychotropic loading than did outpatients. These differences were

attributed to higher illness severity among inpatients. Whether a difference exists

between Asian and Western countries in antipsychotic loading should be

investigated in future studies.

The large differences in combined medication use observed among countries

are difficult to explain. For instance, in Bangladesh, only 1 of 99 (1%) patients was

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

prescribed mood stabilizers; by contrast, 25.8% and 35.0% of the patients in

Pakistan and China, respectively, were prescribed mood stabilizers. The rate of

antidepressant use was less than 5% in Indonesia, Vietnam, Japan, Myanmar, and

Accepted Article

Bangladesh, but was 23.4%, 25.8%, and 36.6% in Singapore, Hong Kong, and South

Korea, respectively. More than half of the patients in Pakistan (55.7%) and Korea

(54.2%) were receiving anxiolytics, whereas this rate was considerably smaller in

Myanmar (8.5%) and Sri Lanka (9.3%). However, the most notable difference was

observed for the use of hypnotics. In most countries, hypnotics were rarely

prescribed, but the rate of their use was 61.1% and 36.5% in Japan and Taiwan,

respectively. Nevertheless, our pooled combined medication use rates were lower

than those recently reported for 961 patients with schizophrenia from the Eastern

European region (anxiolytics, 70%; antidepressants, 42%; mood stabilizers, 27%).27

Some explanations to account for these differences among countries have been

proposed, such as training backgrounds, availability of drugs, and reimbursement

systems. Although no guidelines have been established for antipsychotic

polypharmacy or combined medications in the treatment of schizophrenia, a subset

of patients still require such unconventional pharmacotherapy.28 In a special

article,29 polypharmacy and high-dose antipsychotics were proposed. Additional

studies are warranted to elucidate the ideal rate of polypharmacy and combined

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

psychotropic drug use.

In this study, we created a PDL index to represent the medication burden on

patients with schizophrenia. In the treatment of schizophrenia, we considered each

Accepted Article

class of drug to have the same weighting, in terms of efficacy and side effects. This

is similar to the disease severity assessment of schizophrenia by Positive and

Negative Syndrome Scale,30 in which the item of delusion or hallucinatory behavior,

has the same weighting to the item of anxiety or depression. Notably, Japan had a

higher rate of polypharmacy (55.0%) and the highest index of antipsychotic loading

(2.29 ± 1.79) and PDL (4.06 ± 3.05); by contrast, Vietnam had the highest rate of

polypharmacy (59.1%) and lower antipsychotic loading (1.77 ± 0.96) and PDL (2.09

± 1.11). This example reveals that a high rate of polypharmacy does not necessarily

indicate a high burden of psychotropic drugs. Thus, when reviewing a prescription

pattern in the treatment of schizophrenia, the evaluation of antipsychotic

polypharmacy rate, antipsychotic loading index, and global PDL is crucial.

The PDL index may be applied to any other psychiatric disorder; the concept of

drug loading may be also applied to other diseases, such as hypertension and

diabetic mellitus, where polypharmacy or combined medication use is prevalent.

The main perspectives of the REAP are comparing the differences in

prescription patterns across Asian countries and contributing to the improvement of

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

psychotropic drug prescription quality in the Asian countries that participate in this

collaborative consortium. Similar to the conception of a quality indicator project,31,32

a set of indicators can be developed by using these comparisons; the exact positions

Accepted Article

of these indicators can then be learned by clinicians and health administrators to

obtain consistent results. Thus, according to the REAP-AP4 data related to

schizophrenia pharmacotherapy in Asian countries, we suggest the ideal rate of

antipsychotic polypharmacy could be around 30%; the approximate rates in

combination with mood stabilizers, antidepressants, anxiolytics, and hypnotics could

be 15%, 10%, 30%, and 10%, respectively; furthermore, the antipsychotic loading

and PDL could be approximately 1.5 and 2.0, respectively.

In conclusion, the differences in prescription patterns in the treatment of

schizophrenia among countries and fluctuations in the results among the

REAP-AP1–4 may attribute to the diverse training backgrounds of psychiatrists,

civil culture, availability and cost of drugs, patient characteristics, and the local

health care reimbursement system of each country. For a prescriber treating

schizophrenia, the golden rule should be an adequate dose of antipsychotic, reducing

polypharmacy and combined medication as much as possible. The results from all of

the REAP-AP studies provide a basis to compare individual clinicians and countries,

facilitating a more suitable and reasonable prescription pattern. It also offers an

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

indicator of change of practice due to changes in the education of psychiatry and

other mental health systems interventions.

Accepted Article

Limitations

This study had several limitations: the convenient sampling method may have

incurred selection bias, patients underwent antipsychotic switching and dose

tapering, the numbers of patients enrolled from each country varied, no stratification

of illness severity was performed, and the ethnic diversity of the sample.

Nevertheless, the comparison of the four surveys may approximate trends of

antipsychotic polypharmacy and combined medications in the treatment of patients

with schizophrenia across Asian countries. Future research should employ a more

precise study design, and also investigate the effects of prescription patterns on

bipolar disorder or other minor psychiatric disorders, particularly by comparing

them with results from Western countries.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mr. Da-Yi Tsai for internet server maintenance and Mr. Yan-Lung

Chiou for assistance of data management. The authors are grateful to the following

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

clinicians involved in the data collection: Mekhala Sarkar in Bangladesh; Hao Wei

and Weifu Cai in China; Adarsh Tripathi, Ajit Avasthi, Sandeep Grover, Amitava

Dan and Arshad Hussain in India; Andi J Tanra, Elmeida Effendy, Margarita

Accepted Article

Maramis, Khamelia Malik, Isa Multazam, Santi Yuliani, Widodo Sarjana and Metta

Desvini in Indonesia; Toshiya Inada, Hiroaki Kawasaki, Kentaro Kira, Yuma Ogushi,

Shigenobu Kanba, Takahiro Kato, Hiroaki Kubo, Hironori Kuga, Nobutomo

Yamamoto, Futoshi Shintani, Hajime Iwatsuki, Hideki Horikawa and Mina

Sato-Kasai in Japan; Min-Soo Lee, Seon-Cheol Park and Yong-Chon Park in Korea;

Chee Kok Yoon, Loi-Fei Chin, Chee-Hoong Moey, Yee-Tieng Lee, Aida Mohd Arif,

Siong-Teck Wong, Syarifah Hafizah Wan Kassim, Selvasingam Ratnasingam and

Siti Salwa Ramly in Malaysia; Wing Aung Myint, Tin Oo, Bo Bo Nyan, Sun Lin,

Nyan Win Kyaw in Myanmar; M. Munir Hamirani, Imtiaz Dogar and Mazhar Malik

in Pakistan; Ee-Heok Kua and Johnson Fam in Singapore; Samudra Kathiarachchi,

Dulshika Wass and Thilini Rajapakse in Sri Lanka; Chi-Fa Hung, Tsung-Ming Hu,

Chih-Ken Chen, Wen-Chen Ouyang in Taiwan; Pichet Udomratn, Nopporn

Tantirangsee and Pairoj Sareedenchai in Thailand; Tran Van Cuong, La Duc Cuong,

Bui The Khanh, Nguyen Doan Phuong, Ngo Van Vinh, Ly Tran Tinh, Trinh Tat

Thang, Lam Tu Trung, Doan Hong Quang, Duong Thi Quynh Hoa, Trinh Van An

and Cao Tien Duc in Vietnam. We acknowledge Wallace Academic Editing

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

(www.editing.tw) for editing this manuscript.

DISCLOSURES STATEMENT

Accepted Article

This work was supported by Taipei City Government (10501-62-012). The authors

declare no conflict of interest in reporting this study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

N.S., M.Y.C., S.Y.Y., C.H.T., N.S., and S.K.L. designed the REAP-AP4 study and

wrote the protocol. L.Y.C., E.N., R.A.K., K.V., R.J., A.J., D.T.Q.H., H.I., K.S., T.S.,

Y.L.H., Y.P., H.U.A., A.D.A., H.F.K.C., recruited participants in different countries,

and S.Y.Y., and S.K.L. performed the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

References

1. Friend DG. Polypharmacy; multiple-ingredient and shotgun prescriptions.

The New England journal of medicine 1959; 260: 1015-10188.

2. Kane JM, Correll CU. Past and present progress in the pharmacologic

treatment of schizophrenia. The Journal of clinical psychiatry 2010; 71:

Accepted Article

1115-1124.

3. Correll CU, Shaikh L, Gallego JA et al. Antipsychotic polypharmacy: a

survey study of prescriber attitudes, knowledge and behavior. Schizophrenia

research 2011; 131: 58-62.

4. Mojtabai R, Olfson M. National trends in psychotropic medication

polypharmacy in office-based psychiatry. Archives of general psychiatry

2010; 67: 26-36.

5. Fisher MD, Reilly K, Isenberg K, Villa KF. Antipsychotic patterns of use in

patients with schizophrenia: polypharmacy versus monotherapy. BMC

psychiatry 2014; 14: 341.

6. Procyshyn RM, Honer WG, Wu TK et al. Persistent antipsychotic

polypharmacy and excessive dosing in the community psychiatric treatment

setting: a review of medication profiles in 435 Canadian outpatients. The

Journal of clinical psychiatry 2010; 71: 566-573.

7. Kadra G, Stewart R, Shetty H et al. Predictors of long-term (>/=6months)

antipsychotic polypharmacy prescribing in secondary mental healthcare.

Schizophrenia research 2016; 174: 106-112.

8. Xiang YT, Wang CY, Si TM et al. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in inpatients

with schizophrenia in Asia (2001-2009). Pharmacopsychiatry 2012; 45:

7-12.

9. Ito C, Kubota Y, Sato M. A prospective survey on drug choice for

prescriptions for admitted patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry and

clinical neurosciences 1999; 53 Suppl: S35-40.

10. Stahl SM. Antipsychotic polypharmacy, Part 1: Therapeutic option or dirty

little secret? The Journal of clinical psychiatry 1999; 60: 425-426.

11. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, Kane JM, Leucht S. Antipsychotic

combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of

randomized controlled trials. Schizophrenia bulletin 2009; 35: 443-57.

12. Stahl SM. Antipsychotic polypharmacy: never say never, but never say

always. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica 2012; 125: 349-351.

13. Sim K, Su A, Fujii S et al. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in patients with

schizophrenia: a multicentre comparative study in East Asia. British journal

of clinical pharmacology 2004; 58: 178-183.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

14. Freudenreich O, Goff DC. Polypharmacy in schizophrenia: a fuzzy concept.

The Journal of clinical psychiatry 2003; 64: 1132; author reply 1132-1133.

15. Davis JM. Dose equivalence of the antipsychotic drugs. Journal of

psychiatric research 1974; 11: 65-69.

16. Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical

Accepted Article

antipsychotics. The Journal of clinical psychiatry 2003; 64: 663-667.

17. Leucht S, Samara M, Heres S, Patel MX, Woods SW, Davis JM. Dose

equivalents for second-generation antipsychotics: the minimum effective

dose method. Schizophrenia bulletin 2014; 40: 314-326.

18. Leucht S, Samara M, Heres S et al. Dose Equivalents for Second-Generation

Antipsychotic Drugs: The Classical Mean Dose Method. Schizophrenia

bulletin 2015; 41: 1397-1402.

19. Nose M, Tansella M, Thornicroft G et al. Is the Defined Daily Dose system a

reliable tool for standardizing antipsychotic dosages? International clinical

psychopharmacology 2008; 23: 287-290.

20. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology AciwD, 2016.

Oslo, Norway 2015.

21. Takei N, Inagaki A, group J-r. Polypharmacy for psychiatric treatments in

Japan. Lancet 2002; 360: 647.

22. Shinfuku M, Uchida H, Tsutsumi C et al. How psychotropic polypharmacy

in schizophrenia begins: a longitudinal perspective. Pharmacopsychiatry

2012; 45: 133-137.

23. Inada T, Inagaki A. Psychotropic dose equivalence in Japan. Psychiatry and

clinical neurosciences 2015; 69: 440-447.

24. Hashimoto Y, Tensho M. Effect of pharmacist intervention on physician

prescribing in patients with chronic schizophrenia: a descriptive pre/post

study. BMC health services research 2016; 16: 150.

25. Yamanouchi Y, Sukegawa T, Inagaki A et al. Evaluation of the individual

safe correction of antipsychotic agent polypharmacy in Japanese patients

with chronic schizophrenia: validation of safe corrections for antipsychotic

polypharmacy and the high-dose method. The international journal of

neuropsychopharmacology 2014; 18.

26. Li Q, Xiang YT, Su YA et al. Antipsychotic polypharmacy in schizophrenia

patients in China and its association with treatment satisfaction and quality

of life: findings of the third national survey on use of psychotropic

medications in China. The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry

2015; 49: 129-136.

27. Szkultecka-Debek M, Miernik K, Stelmachowski J et al. Treatment patterns

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

of schizophrenia based on the data from seven Central and Eastern European

Countries. Psychiatria Danubina 2016; 28: 234-242.

28. Stahl SM. Emerging guidelines for the use of antipsychotic polypharmacy.

Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment 2013; 6:97-100

29. Moore BA, Morrissette DA, Meyer JM, Stahl SM. Drug information update.

Accepted Article

Unconventional treatment strategies for schizophrenia: polypharmacy and

heroic dosing. BJPsych Bull 2017, 41:164-168.30. Kay SR, Fiszbein A,

Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for

schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin 1987; 13: 261-276.

31. Arah OA, Westert GP, Hurst J, Klazinga NS. A conceptual framework for the

OECD Health Care Quality Indicators Project. International journal for

quality in health care 2006; 18 Suppl 1: 5-13.

32. Carinci F, Van Gool K, Mainz J et al. Towards actionable international

comparisons of health system performance: expert revision of the OECD

framework and quality indicators. International journal for quality in health

care 2015; 27: 137-146

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Figuure legends

Figuure 1. Compparison of polypharmaccy rates from

m the REAP

P-AP1 to REAP-AP4.

Accepted Article

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Figuure 2. Compparison of psychotropic

p c drug loadiing betweenn countries; red bar

indiicates antipssychotic loaading and bllue bar indicates combined medicaations

loadding.

Accepted Article

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Accepted Article

Table 1. Patient number and demographics in each country

South Sri Hong

Indonesia India Taiwan Thailand Malaysia Pakistan Vietnam Japan Singapore Myanmar China Bangladesh Total

n(%) Korea Lanka Kong

n= 581 479 403 322 305 298 274 229 171 164 160 131 99 97 31 3744

gender

Male 370 319 182 212 157 168 184 140 64 107 104 59 58 58 18 2200

( 63.7 ) ( 66.6 ) ( 45.2 ) ( 65.8 ) ( 51.5 ) ( 56.4 ) ( 67.2 ) ( 61.1 ) ( 37.4 ) ( 65.2 ) ( 65 ) ( 45 ) ( 58.6 ) ( 59.8 ) ( 58.1 ) ( 58.8 )

Female 211 160 221 110 148 130 90 89 107 57 56 72 41 39 13 1544

( 36.3 ) ( 33.4 ) ( 54.8 ) ( 34.2 ) ( 48.5 ) ( 43.6 ) ( 32.8 ) ( 38.9 ) ( 62.6 ) ( 34.8 ) ( 35 ) ( 55 ) ( 41.4 ) ( 40.2 ) ( 41.9 ) ( 41.2 )

Age

mean 34.9 36 47.6 39.3 39.3 36.9 38.7 46.5 48.1 37.6 39.7 40.5 31.9 40.4 38.8 39.5

SD 11.3 11.7 11.7 12.3 12.3 11.9 12 14.4 13.7 11.2 16.4 12.5 11.0 13.3 13.9 13.1

Body weight

mean 60.5 64.4 64.9 63.3 67.1 66.3 57.3 64.1 62.5 56.7 67.9 66.7 52.2 57.8 71.8 62.9

SD 12.8 11.9 15.5 13.2 16.5 13.6 10.1 14.2 13.9 10.1 13.0 13.2 12.4 10.2 15.4 13.8

BMI

mean 23.1 24.1 24.8 23.7 25.3 25.2 21.9 23.9 24.7 21.8 24.1 24.2 22.0 22.9 26.3 23.8

SD 4.7 4.4 4.9 4.5 5.1 5.2 3.5 4.3 5.0 3.6 3.8 3.8 4.0 3.4 5.5 4.6

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Accepted Article

Table 2. Antipsychotic polypharmacy and combined medications

South Sri Hong

Indonesia India Taiwan Thailand Malaysia Pakistan Vietnam Japan Singapore Myanmar China Bangladesh Total

Korea Lanka Kong

N 581 479 403 322 305 298 274 229 171 164 160 131 99 97 31 3744

Polypharmacy (More than 1 antipsychotic)

N 234 123 109 175 132 154 162 126 90 36 84 60 45 41 9 1580

% (40.3) (25.7) (27.0) (54.3) (43.3) (51.7) (59.1) (55.0) (52.6) (22.0) (52.5) (45.8) (45.5) (42.3) (29.0) (42.2±12.0)

Number of Antipsychotic used

mean 1.4 1.3 1.3 1.7 1.5 1.6 1.6 1.8 1.6 1.2 1.6 1.6 1.5 1.5 1.3 1.5

SD 0.6 0.5 0.5 0.7 0.6 0.8 0.5 0.9 0.6 0.4 0.6 0.8 0.5 0.6 0.5 0.6

Antipsychotic loading (Sum of each antipsychotic’s PDD/DDD)

mean 1.00 1.33 1.39 1.39 1.43 1.79 1.79 2.29 1.47 1.14 1.79 1.92 2.17 1.81 1.44 1.50

SD 0.64 0.92 0.97 1.19 1.07 1.47 1.02 1.79 0.99 0.55 0.95 1.74 1.01 1.34 0.75 1.15

Mood stabilizer used

N 44 34 54 63 18 77 37 69 30 16 56 11 1 7 6 523

% (7.6) (7.1) (13.4) (19.6) (5.9) (25.8) (13.5) (30.1) (17.5) (9.8) (35.0) (8.4) (1.0) (7.2) (19.4) (14.0±9.7)

Antidepressant used

N 24 73 51 62 21 56 12 6 40 5 29 48 0 13 8 448

% (4.1) (15.2) (12.7) (19.3) (6.9) (18.8) (4.4) (2.6) (23.4) (3.0) (18.1) (36.6) 0 (13.4) (25.8) (12.0±10.3)

Anxiolytics used

N 92 151 157 99 49 166 42 73 53 14 24 71 39 9 5 1044

% (15.8) (31.5) (39.0) (30.7) (16.1) (55.7) (15.3) (31.9) (31.0) (8.5) (15.0) (54.2) (39.4) (9.3) (16.1) (27.9±15.2)

Hypnotics used

N 1 7 147 10 1 21 0 140 10 0 4 2 4 0 1 348

% (0.2) (1.5) (36.5) (3.1) (0.3) (7.0) 0 (61.1) (5.8) 0 (2.5) (1.5) (4.0) 0 (3.2) (9.3±17.2)

Antiparkinsonian drug used

N 224 180 154 272 116 207 30 90 69 99 49 65 87 33 13 1688

% (38.6) (37.6) (38.2) (84.5) (38.0) (69.5) (10.9) (39.3) (40.4) (60.4) (30.6) (49.6) (87.9) (34.0) (41.9) (45.1±20.6)

Note: Red and blue cells contain more than and less than 1 SD, respectively.

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

Accepted Article

Table 3. Comparison of polypharmacy and drug loading between inpatients and outpatient

Inpatient Outpatient P value

Count 1950 1794

Polypharmacy N (%) 957 (49.1) 623 (34.7) < 0.001

Antipsychotic loading mean (SD) 1.72 (1.24) 1.27 (1.01) < 0.001

Psychotropic drug loading mean (SD) 2.29 (1.79 ) 1.70 (1.40) < 0.001

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- ADHD OaplDocument145 pagesADHD Oaplminiloup05No ratings yet

- Inada, 2015Document8 pagesInada, 2015Khumaira SantaNo ratings yet

- Antipsychotic Medication Prescribing Trends in A Tertiary Care HospitalDocument4 pagesAntipsychotic Medication Prescribing Trends in A Tertiary Care HospitalSilfa NataliaNo ratings yet

- Patterns and Frequency of Atypical Antipsychotic Prescribing in Psychiatric Medical Centers: A Cross-Sectional National SurveyDocument9 pagesPatterns and Frequency of Atypical Antipsychotic Prescribing in Psychiatric Medical Centers: A Cross-Sectional National Surveymiron_ghiuNo ratings yet

- Pone 0267808Document22 pagesPone 0267808patowilliamsNo ratings yet

- Off-Label Use of Sodium Valproate For SchizophreniaDocument7 pagesOff-Label Use of Sodium Valproate For SchizophreniaHaya GrinvaldNo ratings yet

- Antipsychotic Polypharmacy in Psychotic DisorderDocument10 pagesAntipsychotic Polypharmacy in Psychotic DisorderFiarry FikarisNo ratings yet

- Efficacy and Safety of Paliperidone Palmitate Eca ADocument14 pagesEfficacy and Safety of Paliperidone Palmitate Eca AMaria Fernanda AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Meta-Analysis 1Document9 pagesMeta-Analysis 1blessing OjoneNo ratings yet

- BarbuiDocument8 pagesBarbuirinaldiapt08No ratings yet

- Evaluation of Anti-Psychotics Prescribing Pattern Using Who Indicators in A Tertiary Care HospitalDocument14 pagesEvaluation of Anti-Psychotics Prescribing Pattern Using Who Indicators in A Tertiary Care HospitalInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- Pi Is 0025712514000893Document32 pagesPi Is 0025712514000893Christoph HockNo ratings yet

- Antipsychotic PolypharmacyDocument10 pagesAntipsychotic PolypharmacymarcoNo ratings yet

- NDT 45697 Efficacy of Second Generation Antipsychotics in Patients at 061813Document8 pagesNDT 45697 Efficacy of Second Generation Antipsychotics in Patients at 061813twahyuningsih_16No ratings yet

- Provisional: Pharmacotherapy of Anxiety Disorders: Current and Emerging Treatment OptionsDocument73 pagesProvisional: Pharmacotherapy of Anxiety Disorders: Current and Emerging Treatment OptionsDewi NofiantiNo ratings yet

- Integrative Literature Review FinalDocument17 pagesIntegrative Literature Review Finalapi-355221395No ratings yet

- Clinician Guidelines For The Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders With Nutraceuticals and Phytoceuticals The World Federation of Societies of BiologicaDocument34 pagesClinician Guidelines For The Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders With Nutraceuticals and Phytoceuticals The World Federation of Societies of Biologicapatrick.arnonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12Document59 pagesChapter 12Alif riadiNo ratings yet

- Atypical Antipsychotic Augmentation in Major Depressive DisorderDocument13 pagesAtypical Antipsychotic Augmentation in Major Depressive DisorderrantiNo ratings yet

- Alpha-Dihydroergocryptine vs. Pramipexole As Adjunct Symptomatic Treatment of Idiopathic Parkinson'sDocument9 pagesAlpha-Dihydroergocryptine vs. Pramipexole As Adjunct Symptomatic Treatment of Idiopathic Parkinson'sRizka Leonita FahmyNo ratings yet

- Mahatme M S Et. Al., 2018Document6 pagesMahatme M S Et. Al., 2018kaniNo ratings yet

- Panss ScoreDocument8 pagesPanss ScoretriaclaresiaNo ratings yet

- Prescription Patterns of Patients Diagnosed With Schizophrenia in Mental Hospitals in Tashkent/Uzbekistan and in Four German CitiesDocument7 pagesPrescription Patterns of Patients Diagnosed With Schizophrenia in Mental Hospitals in Tashkent/Uzbekistan and in Four German CitiesRina YemimaNo ratings yet

- Antipsychotic Use in Children and Adolescents A.13Document7 pagesAntipsychotic Use in Children and Adolescents A.13jacopo pruccoliNo ratings yet

- Medi-100-E27653Document7 pagesMedi-100-E27653Rika TriwardianiNo ratings yet

- Earitcle - Practice Parameters For The Psychological and Behavioaral Treatment of InsomniaDocument5 pagesEaritcle - Practice Parameters For The Psychological and Behavioaral Treatment of InsomniaRichard SiahaanNo ratings yet

- Appi Focus 16407Document10 pagesAppi Focus 16407MARIALEJ PEREZ MONTALVANNo ratings yet

- Morbidity Profile and Prescribing Patterns Among Outpatients in A Teaching Hospital in Western NepalDocument7 pagesMorbidity Profile and Prescribing Patterns Among Outpatients in A Teaching Hospital in Western Nepalpolosan123No ratings yet

- Clinical Medicine Insights: PediatricsDocument14 pagesClinical Medicine Insights: PediatricsferegodocNo ratings yet

- Ijmrhs Vol 4 Issue 3Document263 pagesIjmrhs Vol 4 Issue 3editorijmrhsNo ratings yet

- Usr 6403928586398Document3 pagesUsr 6403928586398Rodrigo SosaNo ratings yet

- J Eurpsy 2007 03 002Document11 pagesJ Eurpsy 2007 03 002xhdrv7nvdrNo ratings yet

- J Ajem 2020 07 013Document21 pagesJ Ajem 2020 07 013Athea 88No ratings yet

- Comparative e Cacy and Acceptability of Antimanic Drugs in Acute Mania: A Multiple-Treatments Meta-AnalysisDocument10 pagesComparative e Cacy and Acceptability of Antimanic Drugs in Acute Mania: A Multiple-Treatments Meta-AnalysisCarolina PradoNo ratings yet

- Psychotic Disorders Induced by Antiepileptic Drugs in People With EpilepsyDocument11 pagesPsychotic Disorders Induced by Antiepileptic Drugs in People With EpilepsyShadrackNo ratings yet

- Pharmacologic Treatment of Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity DisorderDocument7 pagesPharmacologic Treatment of Attention Deficit-Hyperactivity DisorderSusana Maria Ribero BalagueraNo ratings yet

- Tdah - ReviewDocument7 pagesTdah - ReviewFábio Yutani KosekiNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Prescription Pattern of Psychotropics I 2022 Medical JournalDocument6 pagesAnalysis of The Prescription Pattern of Psychotropics I 2022 Medical JournalAnisha RanaNo ratings yet

- REF4 - Evaluation of Drug Utilization and Analysis of AntiEpileptic DrugsDocument7 pagesREF4 - Evaluation of Drug Utilization and Analysis of AntiEpileptic DrugsJorge Ropero VegaNo ratings yet

- Sleep Medicine: Judith A. Owens, Carol L. Rosen, Jodi A. Mindell, Hal L. KirchnerDocument9 pagesSleep Medicine: Judith A. Owens, Carol L. Rosen, Jodi A. Mindell, Hal L. KirchnerHernán MarínNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Drugs in Children and Adolescents: Basic Pharmacology and Practical ApplicationsDocument540 pagesPsychiatric Drugs in Children and Adolescents: Basic Pharmacology and Practical ApplicationsRey Jerly Duran BenitoNo ratings yet

- Paliperidona Revision 18 PagsDocument19 pagesPaliperidona Revision 18 PagsRodrigo SosaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Characteristics of Agitated Psychotic Patients Treated With An Oral Antipsychotics Attended in The Emergency Room Setting: NATURA StudyDocument8 pagesClinical Characteristics of Agitated Psychotic Patients Treated With An Oral Antipsychotics Attended in The Emergency Room Setting: NATURA StudyMaria Niña Beatrice DelaCruzNo ratings yet

- Herbal Medicine Treatment For Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic ReviewDocument14 pagesHerbal Medicine Treatment For Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic ReviewMaximiliano QMCNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia Treatment & ManagementDocument16 pagesSchizophrenia Treatment & ManagementDimas Januar100% (2)

- Aripiprazol Versus Quetiapine in Treatment of Non-Affective Acute Psychosis: A Double-Blind, Randomized - Controlled Clinical TrialDocument4 pagesAripiprazol Versus Quetiapine in Treatment of Non-Affective Acute Psychosis: A Double-Blind, Randomized - Controlled Clinical TrialAsti DwiningsihNo ratings yet

- Matej Stuhec Antipsychotic Treatment in ElderlyDocument6 pagesMatej Stuhec Antipsychotic Treatment in Elderlymagocita.martinNo ratings yet

- Current Practices, Experiences, and Views in Clinical HypnosisDocument43 pagesCurrent Practices, Experiences, and Views in Clinical HypnosisJoBPNo ratings yet

- Presentation RTA, DM, Rheumatoid ArthritisDocument26 pagesPresentation RTA, DM, Rheumatoid ArthritisShah MohammedNo ratings yet

- Sci 2013 9 (10s) :60-62) - (ISSN: 1545-1003)Document3 pagesSci 2013 9 (10s) :60-62) - (ISSN: 1545-1003)Muhammad Ziaur RahmanNo ratings yet

- An Association Between Incontinence and Antipsychotic Drugs - A Systematic ReviewDocument9 pagesAn Association Between Incontinence and Antipsychotic Drugs - A Systematic ReviewchaconcarpiotatianaNo ratings yet

- Hipnose e AVCDocument8 pagesHipnose e AVCTransf ArquivosNo ratings yet

- Aripiprazol LAI Vs Paliperidona LAI in SKDocument10 pagesAripiprazol LAI Vs Paliperidona LAI in SKRobert MovileanuNo ratings yet

- 2017-Ugo Chukwu-International Journal of Medicine and PharmacyDocument10 pages2017-Ugo Chukwu-International Journal of Medicine and PharmacyNurettin AbacıoğluNo ratings yet

- Gajjar B M Et. Al., 2016Document6 pagesGajjar B M Et. Al., 2016kaniNo ratings yet

- 2021 Grupo 1 Metanálise AntidepressivosDocument14 pages2021 Grupo 1 Metanálise AntidepressivosAmanda NelvoNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Stimulant Treatment Affects Brain Dopamine Transporter Level in Patients With Attention Deficit Hyperactive DisorderDocument6 pagesLong-Term Stimulant Treatment Affects Brain Dopamine Transporter Level in Patients With Attention Deficit Hyperactive DisorderpriyaNo ratings yet

- Initial Severity Jama PDFDocument8 pagesInitial Severity Jama PDFnoeanisaNo ratings yet

- Initial Severity of Schizophrenia and Efficacy of Antipsychotics Participant-Level Meta-Analysis of 6 Placebo-Controlled StudiesDocument8 pagesInitial Severity of Schizophrenia and Efficacy of Antipsychotics Participant-Level Meta-Analysis of 6 Placebo-Controlled StudieseviantiNo ratings yet

- Medication Errors Associated With Look-alike/Sound-alike Drugs: A Brief ReviewDocument8 pagesMedication Errors Associated With Look-alike/Sound-alike Drugs: A Brief Reviewsabbo morsNo ratings yet

- 01 Drug Absorption (Notes - Q A) AtfDocument2 pages01 Drug Absorption (Notes - Q A) Atfemaannoor972No ratings yet

- Daftar Nama Obat Di Farmasi Klinik Ibnu SinaDocument5 pagesDaftar Nama Obat Di Farmasi Klinik Ibnu SinaAfifa RahmahNo ratings yet

- Pentingnya Pemberian Imunisasi DPT Pada Anak Difteri Dan PertusisDocument30 pagesPentingnya Pemberian Imunisasi DPT Pada Anak Difteri Dan Pertusisrevi rillianiNo ratings yet

- Drug Study PediaDocument3 pagesDrug Study PediaDanica Kate GalleonNo ratings yet

- ParacetamolDocument2 pagesParacetamolKristine YoungNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee: APOLLOJAMES, M. Pharm., (PH.D), Asst - Prof, Dept of Pharmacy PracticeDocument39 pagesPharmacy and Therapeutics Committee: APOLLOJAMES, M. Pharm., (PH.D), Asst - Prof, Dept of Pharmacy PracticeSuresh ThanneruNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics - PPT - Dr. Maulana Antian Empitu (Airlangga Medical Faculty)Document59 pagesPharmacology Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics - PPT - Dr. Maulana Antian Empitu (Airlangga Medical Faculty)rizkyyunitaa15No ratings yet

- Multimodal Analgesia Techniques and Postoperative RehabilitationDocument18 pagesMultimodal Analgesia Techniques and Postoperative RehabilitationJazmín PrósperoNo ratings yet

- Insulin Injection PDFDocument6 pagesInsulin Injection PDFAulia mulidaNo ratings yet

- The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of PsDocument3 pagesThe American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Ps!R_I_A!No ratings yet

- Abaloparatide (Tymlos) For OsteoporosisDocument2 pagesAbaloparatide (Tymlos) For Osteoporosishossein kasiriNo ratings yet

- Medicines For BaguioDocument3 pagesMedicines For BaguioMaielyne Keith DalilisNo ratings yet

- Inn Dci ListDocument80 pagesInn Dci ListPapa Sissao SeckNo ratings yet

- THE Check Principle Applied in Pharmacology: Remember To Take Your Tagamet With Meals!Document35 pagesTHE Check Principle Applied in Pharmacology: Remember To Take Your Tagamet With Meals!helloaNo ratings yet

- Crash Cart Check ListDocument2 pagesCrash Cart Check Listkim reyesNo ratings yet

- Practice Standard: Safe Prescribing of Opioids and SedativesDocument4 pagesPractice Standard: Safe Prescribing of Opioids and SedativesSteve GreenNo ratings yet

- CLARITHROMYCINDocument3 pagesCLARITHROMYCINCay SevillaNo ratings yet

- Lisinopril (Prinvil, Zestril) Fosinopril (Monopril) Ramapril (Altace)Document1 pageLisinopril (Prinvil, Zestril) Fosinopril (Monopril) Ramapril (Altace)vigNo ratings yet

- COMPRE - MODULE 3 (Practice of Pharmacy) : Attempt ReviewDocument39 pagesCOMPRE - MODULE 3 (Practice of Pharmacy) : Attempt ReviewLance RafaelNo ratings yet

- Simvastatin 20 MG Paracetamol 500 MG Tab Paracetamol 650 MG Tab Acyclovir CreamDocument7 pagesSimvastatin 20 MG Paracetamol 500 MG Tab Paracetamol 650 MG Tab Acyclovir CreamtdshyenNo ratings yet

- DrugStudy CelecoxibDocument2 pagesDrugStudy CelecoxibLegendXNo ratings yet

- P2 (1) - Kowski AB, Et Al. Epilepsy Behav - 2016 Jan 54150-7.Document8 pagesP2 (1) - Kowski AB, Et Al. Epilepsy Behav - 2016 Jan 54150-7.li chenNo ratings yet

- Pepcid AC - Group1 - AnalysisDocument2 pagesPepcid AC - Group1 - AnalysisRini RafiNo ratings yet

- USFDA Guidance For Industry - PSURDocument50 pagesUSFDA Guidance For Industry - PSURErshad Shafi AhmedNo ratings yet

- India: Drug Regulatory Framework & New InitiativesDocument16 pagesIndia: Drug Regulatory Framework & New InitiativesRajesh RanganathanNo ratings yet

- Drug Interactions of Antianginal Drugs..Document40 pagesDrug Interactions of Antianginal Drugs..Kamal SikandarNo ratings yet

- Beneficiary Details: COVID-19Document1 pageBeneficiary Details: COVID-19THAMIZHAZHAHAN SNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument4 pagesDrug StudyMelvin D. RamosNo ratings yet

- Drugs Not To Take With LDNDocument10 pagesDrugs Not To Take With LDNbktangoNo ratings yet