Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Association For Asian Studies

Association For Asian Studies

Uploaded by

kanye hardbassCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Taisho Democracy in Japan - 1912-1926 - Facing History and OurselvesDocument7 pagesTaisho Democracy in Japan - 1912-1926 - Facing History and Ourselvesfromatob3404100% (1)

- Changing Face of The YakuzaDocument21 pagesChanging Face of The YakuzaUğur ArgunNo ratings yet

- MRP Passport Form (Bangladesh Form)Document4 pagesMRP Passport Form (Bangladesh Form)Muhibbul Muktadir Tanim67% (3)

- Burakumin At: The End of HistoryDocument27 pagesBurakumin At: The End of HistoryCatherine Masitsa OmondiNo ratings yet

- Yasuba 1975 PDFDocument21 pagesYasuba 1975 PDFChristian JavierNo ratings yet

- Asad Haider y Salar Mohandesi 2015Document7 pagesAsad Haider y Salar Mohandesi 2015lagata1000No ratings yet

- Japanese Imperialism 1894-1945Document23 pagesJapanese Imperialism 1894-1945vigici2555No ratings yet

- A Social Basis for Prewar Japanese Militarism: The Army and the Rural CommunityFrom EverandA Social Basis for Prewar Japanese Militarism: The Army and the Rural CommunityNo ratings yet

- Sakuma Shozan S Hegelian Vision For Japan (Van Sant)Document17 pagesSakuma Shozan S Hegelian Vision For Japan (Van Sant)dash1011No ratings yet

- Chalmers Johnson - MITI and The Japanese Miracle - The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975-SUP (1982)Document409 pagesChalmers Johnson - MITI and The Japanese Miracle - The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975-SUP (1982)Felipe AugustoNo ratings yet

- Clases RevoluciónDocument30 pagesClases RevoluciónvicenteNo ratings yet

- Satsuma RebellionDocument12 pagesSatsuma RebellionRuh Javier AlontoNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press Journal of Latin American StudiesDocument30 pagesCambridge University Press Journal of Latin American StudiesVictoria HerreraNo ratings yet

- The Emergence of Socialist Parties 1848-1914Document19 pagesThe Emergence of Socialist Parties 1848-1914kaushal yadavNo ratings yet

- Meiji Restoration in JapanDocument21 pagesMeiji Restoration in JapanRamita Udayashankar100% (5)

- Fascism in JapanDocument16 pagesFascism in JapanHISTORY TVNo ratings yet

- BCAS v14n03Document78 pagesBCAS v14n03Len HollowayNo ratings yet

- The Journal of Peasant Studies: To Cite This Article: Neil Charlesworth (1980) The Middle Peasant Thesis' andDocument24 pagesThe Journal of Peasant Studies: To Cite This Article: Neil Charlesworth (1980) The Middle Peasant Thesis' andRavi Naid GorleNo ratings yet

- Peasant Movements in Colonial India An Examination of Some Conceptual Frameworks L S Viishwanath 1990Document6 pagesPeasant Movements in Colonial India An Examination of Some Conceptual Frameworks L S Viishwanath 1990RajnishNo ratings yet

- SHELDON 1958 - The Rise of The Merchant Class in Tokugawa Japan, 1600-1868Document215 pagesSHELDON 1958 - The Rise of The Merchant Class in Tokugawa Japan, 1600-1868Floripondio19No ratings yet

- Plots and Motives in Japan's Meiji RestorationDocument22 pagesPlots and Motives in Japan's Meiji Restorationdash1011No ratings yet

- Japan A3Document8 pagesJapan A3AnoushkANo ratings yet

- Yoshida Shigeru - Transition To Liberal DemocracyDocument16 pagesYoshida Shigeru - Transition To Liberal DemocracyClaudiu AldeaNo ratings yet

- Nam IDocument18 pagesNam Igugoloth shankarNo ratings yet

- Scalice 2022 ADeliberatelyForgottenBattleDocument27 pagesScalice 2022 ADeliberatelyForgottenBattleRaj VillarinNo ratings yet

- B41 - Peruvian Labour and The Military Government Since 1968Document60 pagesB41 - Peruvian Labour and The Military Government Since 1968YakuAtokNo ratings yet

- Association For Asian Studies The Journal of Asian StudiesDocument22 pagesAssociation For Asian Studies The Journal of Asian StudieshoampimpaNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Modernization and Education by Krishna KumarDocument7 pagesAgricultural Modernization and Education by Krishna KumarRachel PhilipNo ratings yet

- Saito1 PortraitDocument13 pagesSaito1 PortraitMohit KharbandaNo ratings yet

- Stuart Laing (Auth.) - Representations of Working-Class Life 1957-1964-Macmillan Education UK (1986)Document246 pagesStuart Laing (Auth.) - Representations of Working-Class Life 1957-1964-Macmillan Education UK (1986)Yasmim CamardelliNo ratings yet

- Labor History and Its Challenges - Confessions of A Latin AmericanistDocument9 pagesLabor History and Its Challenges - Confessions of A Latin Americanistmayaraaraujo.historiaNo ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc. Modern China: This Content Downloaded From 128.210.126.199 On Tue, 28 Jun 2016 20:12:12 UTCDocument37 pagesSage Publications, Inc. Modern China: This Content Downloaded From 128.210.126.199 On Tue, 28 Jun 2016 20:12:12 UTCDavid SlobadanNo ratings yet

- The Meiji Restoration: Modernization & The Rise of Nationalism in JapanDocument10 pagesThe Meiji Restoration: Modernization & The Rise of Nationalism in JapanMuhammad AbbasNo ratings yet

- LMLA TextDocument15 pagesLMLA TextMaciej DrabińskiNo ratings yet

- National Planning in Brazil An Historical PerspectDocument40 pagesNational Planning in Brazil An Historical Perspectabrie6396No ratings yet

- The Making of Modern Japan - Pyle, KennethDocument212 pagesThe Making of Modern Japan - Pyle, KennethKunal100% (1)

- Tracing Your Labour Movement Ancestors: A Guide for Family HistoriansFrom EverandTracing Your Labour Movement Ancestors: A Guide for Family HistoriansNo ratings yet

- Jsis 242-Exam 1 Id TermsasdfDocument12 pagesJsis 242-Exam 1 Id TermsasdfTJ HookerNo ratings yet

- Summary of 'Asian Drama'Document14 pagesSummary of 'Asian Drama'Tushar KadamNo ratings yet

- Book Review 1 - SmethurstDocument3 pagesBook Review 1 - SmethurstpoojajoshimamcNo ratings yet

- Molding Japanese Minds: The State in Everyday LifeFrom EverandMolding Japanese Minds: The State in Everyday LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- 10 2307@657877 PDFDocument44 pages10 2307@657877 PDFlomahanaNo ratings yet

- PAOLI, MC - Labour, Law and The State in Brazil, 1930-1950-2Document459 pagesPAOLI, MC - Labour, Law and The State in Brazil, 1930-1950-2Danilo Lucena MendesNo ratings yet

- The Meiji Restoration EraDocument7 pagesThe Meiji Restoration Eradash1011No ratings yet

- Usa Assignment PDFDocument3 pagesUsa Assignment PDFAnurakti VajpeyiNo ratings yet

- Anarcho-Syndicalism in JapanDocument26 pagesAnarcho-Syndicalism in Japandidier75No ratings yet

- YONG CHING FATT - Leadership Chinese in SGDocument16 pagesYONG CHING FATT - Leadership Chinese in SGJustin LokeNo ratings yet

- Continuar Da Pagina 62Document102 pagesContinuar Da Pagina 62salvandohomensNo ratings yet

- Amateur Manga MovementDocument29 pagesAmateur Manga MovementAndreea SoareNo ratings yet

- The Panic of 1837Document32 pagesThe Panic of 1837vanveen1967No ratings yet

- Why Was There No Marxism in Great Britain ?Document35 pagesWhy Was There No Marxism in Great Britain ?ed whiteNo ratings yet

- Frank Upham, "The Man Who Would Import - A Cautionary Tale About Bucking The System in Japan", 17 Journal of Japanese StudiesDocument21 pagesFrank Upham, "The Man Who Would Import - A Cautionary Tale About Bucking The System in Japan", 17 Journal of Japanese StudiesYanxin ZhangNo ratings yet

- Japanese Emigration To Latin AmericaDocument45 pagesJapanese Emigration To Latin AmericaRene EudesNo ratings yet

- Higginson BringingWorkersBack 1988Document26 pagesHigginson BringingWorkersBack 1988ugabugaNo ratings yet

- Poor Man's Fortune: White Working-Class Conservatism in American Metal Mining, 1850–1950From EverandPoor Man's Fortune: White Working-Class Conservatism in American Metal Mining, 1850–1950No ratings yet

- Making A LivingDocument6 pagesMaking A LivingAlexandra G AlexNo ratings yet

- Peasants KolffDocument25 pagesPeasants KolffTanisha BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Merchants and Society in Tokugawa JapanDocument13 pagesMerchants and Society in Tokugawa JapanDexter ConlinNo ratings yet

- Dwps Next Mun 2024Document24 pagesDwps Next Mun 2024harsh242123No ratings yet

- Us Shipscrapping 44324691963170Document4 pagesUs Shipscrapping 44324691963170dbbony 0088No ratings yet

- Garrigus Oge Americas 2011Document32 pagesGarrigus Oge Americas 2011ansapa1025No ratings yet

- Michael Freeden and The Morphological ApproachDocument181 pagesMichael Freeden and The Morphological ApproachMark A. FosterNo ratings yet

- Hitler-Discurs 1933-Sportpalast Berlin-Transcriere Tip ImaginiDocument355 pagesHitler-Discurs 1933-Sportpalast Berlin-Transcriere Tip ImaginiLuca OctavianNo ratings yet

- Lord Curzon and The Creation of The North-West Frontier Province (1901) : An AppraisalDocument13 pagesLord Curzon and The Creation of The North-West Frontier Province (1901) : An AppraisalnadiasajjadNo ratings yet

- Ozamis CityDocument2 pagesOzamis CitySunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- A.V.M. Sales Corpn. v. Anuradha Chemicals (P) LTD., (2012) 2 SCC 315Document6 pagesA.V.M. Sales Corpn. v. Anuradha Chemicals (P) LTD., (2012) 2 SCC 315nidhidaveNo ratings yet

- The Hill We Climb Amanda GormanDocument3 pagesThe Hill We Climb Amanda GormanDS RoseNo ratings yet

- Interview Prog No.6-2024Document6 pagesInterview Prog No.6-2024Ali RazaNo ratings yet

- Miami BBG 10th Regional Board PacketsDocument10 pagesMiami BBG 10th Regional Board PacketsIlana LadisNo ratings yet

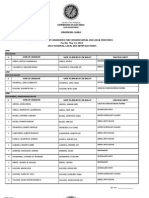

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Affidavit: WHEREFORE, I Have Hereunto Set My Hand This 2Document1 pageAffidavit: WHEREFORE, I Have Hereunto Set My Hand This 2Patricia CastroNo ratings yet

- Despite Modi, India Has Not Yet Become A Hindu Authoritarian StateDocument28 pagesDespite Modi, India Has Not Yet Become A Hindu Authoritarian StateCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- DLL-Q3-W2 - Mam LouDocument8 pagesDLL-Q3-W2 - Mam LouChello Ann Pelaez AsuncionNo ratings yet

- PDF Askep Persalinan Beresiko - CompressDocument40 pagesPDF Askep Persalinan Beresiko - CompressAudini HerawatiNo ratings yet

- 9.19.16 Mayor Lee & Sup. Cohen Hunters Point Shipyard LetterDocument2 pages9.19.16 Mayor Lee & Sup. Cohen Hunters Point Shipyard Lettercb0bNo ratings yet

- Will Banyan - The Illusion of Elite Disunity - Elite FacyionalismThe War OnTerror and The New World OrderDocument34 pagesWill Banyan - The Illusion of Elite Disunity - Elite FacyionalismThe War OnTerror and The New World OrderPopolvuh89No ratings yet

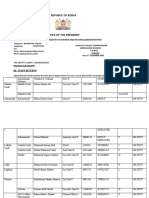

- Republic of Kenya: Ministry of Interior and NationaladministrationDocument3 pagesRepublic of Kenya: Ministry of Interior and NationaladministrationWanNo ratings yet

- Contact Details of Booth Level Officers Blos and Their SupervisersDocument23 pagesContact Details of Booth Level Officers Blos and Their Superviserssanjana.gatty23No ratings yet

- Ir 05Document3 pagesIr 05warnakulasooriyaNo ratings yet

- Andhra PradeshDocument4 pagesAndhra PradeshBharath KumarNo ratings yet

- Sarawak Government Gazette: Mineral Ordinance 2004Document7 pagesSarawak Government Gazette: Mineral Ordinance 2004Alka PillaiNo ratings yet

- 2022 SEIKO Catalogue 24112022Document21 pages2022 SEIKO Catalogue 24112022Gula-gula KapasNo ratings yet

- Nutritional-Status - 8 Daffodils-2022-2023Document98 pagesNutritional-Status - 8 Daffodils-2022-2023Jose Ruel MendozaNo ratings yet

- Pradhan Mantri Aawas YojanaDocument13 pagesPradhan Mantri Aawas YojanaShivam ShanuNo ratings yet

- Export Client List - KDD Pump SystemDocument15 pagesExport Client List - KDD Pump SystemIlyas Rangga RamadhanNo ratings yet

- International Perspectives On Exclusionary Pressures in Education How Inclusion Becomes Exclusion Elizabeth J Done Full ChapterDocument52 pagesInternational Perspectives On Exclusionary Pressures in Education How Inclusion Becomes Exclusion Elizabeth J Done Full Chapterpamela.sevillano879100% (6)

- Manalo Extension, Barangay Milagrosa Puerto Princesa City, Palawan Tel. No. 048-434-2393Document2 pagesManalo Extension, Barangay Milagrosa Puerto Princesa City, Palawan Tel. No. 048-434-2393Alexander ExeveaNo ratings yet

Association For Asian Studies

Association For Asian Studies

Uploaded by

kanye hardbassOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Association For Asian Studies

Association For Asian Studies

Uploaded by

kanye hardbassCopyright:

Available Formats

Organized Workers and Socialist Politics in Interwar Japan. by Stephen S.

Large

Review by: Sheldon M. Garon

The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 42, No. 1 (Nov., 1982), pp. 167-169

Published by: Association for Asian Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2055396 .

Accessed: 18/06/2014 04:02

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Association for Asian Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Asian Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.28 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 04:02:45 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BOOK REVIEWS- JAPAN 167

Trading declined in the early twentieth century when residents were drawn to

employment in Fukuoka and Kitakyiishui, but fishing still engaged about 100

persons in 60 to 70 households in 1930. New species (sand lance and yellowtail)

replacedthe declining sardine, and the large purse seine, requiring several boats to set

and take up, became as important as the beach net. Merchants, however, had

abandoned net ownership; net groups were formed by individual fishermen, dozoku

kin groups, or shareholding cooperative enterprises.

By 1976, these net groups had been dissolved or were inactive. A smaller purse

seine (the gochiami)had been adopted that could be worked by single boats with crews

of 1 to 3 persons, and Kalland details the roles and working relationships on the

twelve gochiamiboats. Cooperation survives only as informal arrangements among

boat crews in the brief, but highly lucrative, season for a particular sea bream fry and

in marketing through the fishing cooperative. Despite the ability to exploit this new

niche, gochiamiboats are economically viable only if operated with family labor, and

wives have come to work beside husbands on five of the twelve boats. Even so,

prospects are bleak for Shinga fishermen. It is difficult to attract spouses. In

twenty-five fishermen marriagesbefore 1960, the averagemale was 26.3 years old and

the average female, 23.5 years; from 1965 to 1978, it rose to 33 years for both. The

wife was the older in seven of the fourteen marriages from 1960 to 1978, and these

fourteen marriages have produced only 16 children. It is no wonder that "few people

in Shingu have any idea of what it is to be a fisherman"(p. 63).

Kalland's ethnography is admirably focused and historically sensitive, despite his

occasional lapses into conjectural history, e.g., the sex ratio imbalance in the 1825

population figures can hardly be explained as sex-selective infanticide among the

fishing households when fishermen were a minority of the population (pp. 44-45).

Also I do not believe that Kalland is particularly well-served by the analytical

language with which he has chosen to couch his material. The frequent referencesto

the "resources relevant to a status" (p. 88) and the "actors . . . allocating their

resources"(p. 146) imply a transactionalexchange theory of social behavior, but such

a theory is never applied rigorously, and the vocabulary by itself remains unconvinc-

ing. His "model of growth and decline" (pp. 146-53) may describe the sequence of

choices that a boat operator confronts, but it does not account for the constraints and

opportunities that form the context of those choices. Fortunately, these stand out

elsewhere in his book: industrial development, coastal pollution, and overfishing (pp.

13, 89); changes in regional employment (pp. 95, 153); shifts in markets for fish (pp.

185-86); reforms in fishing rights and increasingly strict licensing (pp. 89, 135-36);

and growing tensions within the fishing cooperative (pp. 140-45). Taken together,

these provide much more convincing explanations for the precariousposition of the

Shingiu fishermen and will ring true with any student of rural Japan.

WILLIAM W. KELLY

Yale University

Organized Workers and Socialist Politics in Interwar Japan. By STEPHEN S.

LARGE. New York:CambridgeUniversityPress, 1981. viii, 326 pp. Appendix,

Notes, Glossary, Bibliography, Index. $49.50.

In this new age of "Japanas Number One," we sometimes forget there was a time

when Japanese labor was not a respected partner in an efficient, harmonious system of

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.28 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 04:02:45 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

168 JOURNAL OF ASIAN STUDIES

industrial relations. Stephen Large, in his history of Japan's labor movement between

1919 and 1940, describes how it was that independent trade unions emerged as an

assertive, growing force after World War I, only to suffer stagnation and finally

dissolution in the late 1930s. For Large, this is more than a problem of industrial

relations. He explicitly relates the rise and fall of organized labor to one of the most

significant questions in the political history of interwarJapan: Why did the unions

fail to defend Social Democracy? More to the point, why did many labor leaders and

Socialist politicians enthusiastically support the drift toward militarism and authori-

tarianism?

This book is a refreshing antidote to the many Japanese accounts that dwell on the

romantic struggle of Marxist labor leaders against capitalism and the repressive

prewar state. Large avoids treating the unions as hapless victims, arguing that

organized labor possessed a certain degree of choice in its strategies. Taking a cue

from studies of Western social democratic movements, he distinguishes Japan's

Socialist parties, dominated by intellectuals, from the supporting unions, led by

working-class activists. The Socialist politicians generally promoted an ideological

brand of Socialism, but most unions-led by the. General Federation of Labor

(Sodomei)-preferred a more reformist policy of improving the lives of workers by

legislation and negotiation with employers.

Large's conclusions are unexpectedly partisan, yet intriguing. The reformist

Sodomei-not the smaller, Communist-influencedCouncil of Japanese Labor Unions

(Hyogikai)-incurs the major share of the blame for fragmenting organized labor

and the movement for a unified Socialist party after 1925. Recalling the fate of

Weimar Germany's Social Democratic unions, Large comes down hard on Sodomei's

leaders for becoming "bossified," "ossified," and "bourgeoisified." In his opinion,

they collaborated much too closely with management and governmental authorities

to safeguard their positions and distance themselves from the rival Communists.

Their strategy of accommodation forms the key element in the author's discussion of

labor in the hostile environment of the 1930s. He argues that the Socialist intellectu-

als of the newly united Social Masses' party challenged the government's policies of

authoritarianism and imperialism, but were undercut in their efforts by Sodomei

and other labor groups, which had retreated from Socialist politics to unqualified

patriotism and narrowly economic trade unionism. In 1940 the cautious Sodomei

found itself in the worst possible position: neither patriotic enough to prevent its

local membership from defecting to government-sponsored "industrial patriotic"

associations nor militant enough to rally labor against the dissolution of independent

unions.

Notwithstanding the clarity of the case, this book rests on a ratherprovocative set

of assumptions. Large is convinced that the labor movement could have succeeded

only if it had retained the unity and Socialist elan that it briefly enjoyed in

1919-1920. This contributes to Large's brooding portrayal of the developments of

the next two decades in terms of a steady fall from political activism. In fact, the labor

movement experienced a series of peaks and troughs that merit closer examination.

Total union membership quadrupled during this period, and Sodomei succeeded in

uniting two-thirds of the nation's organized workers behind a campaign for a labor

union law in 1929-1931 and probably enjoyed its greatest input in the formulation

of governmental social legislation as late as 1936-1938. Readers may also question

why the author feels that the unions' quest for improved working conditions detracted

from overall Social Democracy.

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.28 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 04:02:45 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BOOK REVIEWS- JAPAN 169

Large's case would have benefited from further discussion on three important

points. He might have demonstrated that organized labor, which accounted for only a

small proportion of Japan's working population, prevented the Socialist parties from

effectively appealing to the more numerous classes of small farmersand shopkeepers.

Second, he could have shown that Socialist politicians like Aso Hisashi were more

resistant to authoritarianism and imperialism than Sodomei's Nishio Suehiro and

Matsuoka Komakichi were. Instead he says that Aso and like-minded labor leaders

led the way in dissolving their unions and the Social Masses' party with the hope of

gaining the government's support for "Socialism from above." In contrast, the

supposedly "conservative" Sodomei officials and their political allies fought a

principled, if futile, battle to preserve independent unions and the multiparty system

until 1940. Who then were the true Social Democrats?

Third and most fundamental, Large's criticisms of the Sodomei's pragmatic

strategy require a fuller analysis of the alternatives available to organized labor. He

readily admits that the Hyogikai's militant tactics in the mid- 1920s and Kato

Kanju's "popular front" of 1937 resulted in total suppression by the state. If such

class-conscious Socialism was not the solution, what was? In view of the movement's

vulnerability, one could argue that Sodomei's cooperation with sympathetic gov-

ernmental authorities and established parties did more to advance Social Democracy

than the actions of labor's militant minority. Unfortunately, Large offers only

minimal coverage of the efforts of the Home Ministry and the Kenseikai/Minseito to

adopt a series of protective labor legislation and policies.

Last, mention should be made of the work's bold use of comparative history.

Studies of European and American labor movements have clearly inspired Large to

uncover new facets of Japan's union movement, most notably Sodomei's developing

subculture of workers' schools, newspapers, and consumer cooperatives. Large, how-

ever, tends to draw too many comparisons and contrasts without questioning their

significance. In the end, we are not sure whether the Japanese unions failed because

they became bourgeoisified as in Germany or because Japanese workers stoically

accepted capitalist inequality as did their British counterparts (I hadn't recalled

British Labour "failing" as a result).

Despite these shortcomings, Large presents us with a thoughtful analysis of the

political impact of Japan's interwar unions and the serious dilemmas they faced. In

the process, he has opened up a new debate on the potential for political and

industrial democracy in Japan before World War II.

SHELDON M. GARON

PomonaCollege

Masamune Hakucho. By ROBERTRoiF. Boston: Twayne, 1979. 171 pp. Pre-

face, Chronology, Titles of Hakucho's Works Cited, Notes and References,

Selected Bibliography, Index. $13.95.

Twayne's World Authors Series (TWAS) is difficult to write for. Each volume is

meant to be constructed so that young adults in preparatoryschools and college can

read it with ease. The series sets high standardsfor scholarly accuracyand chooses its

authors for their expertise. Because the series is intended for young people, each

volume ought to be written in a sufficiently lively style to hold the attention of this

special audience. These would not be easy goals for a writer in any field, but they are

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.28 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 04:02:45 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Taisho Democracy in Japan - 1912-1926 - Facing History and OurselvesDocument7 pagesTaisho Democracy in Japan - 1912-1926 - Facing History and Ourselvesfromatob3404100% (1)

- Changing Face of The YakuzaDocument21 pagesChanging Face of The YakuzaUğur ArgunNo ratings yet

- MRP Passport Form (Bangladesh Form)Document4 pagesMRP Passport Form (Bangladesh Form)Muhibbul Muktadir Tanim67% (3)

- Burakumin At: The End of HistoryDocument27 pagesBurakumin At: The End of HistoryCatherine Masitsa OmondiNo ratings yet

- Yasuba 1975 PDFDocument21 pagesYasuba 1975 PDFChristian JavierNo ratings yet

- Asad Haider y Salar Mohandesi 2015Document7 pagesAsad Haider y Salar Mohandesi 2015lagata1000No ratings yet

- Japanese Imperialism 1894-1945Document23 pagesJapanese Imperialism 1894-1945vigici2555No ratings yet

- A Social Basis for Prewar Japanese Militarism: The Army and the Rural CommunityFrom EverandA Social Basis for Prewar Japanese Militarism: The Army and the Rural CommunityNo ratings yet

- Sakuma Shozan S Hegelian Vision For Japan (Van Sant)Document17 pagesSakuma Shozan S Hegelian Vision For Japan (Van Sant)dash1011No ratings yet

- Chalmers Johnson - MITI and The Japanese Miracle - The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975-SUP (1982)Document409 pagesChalmers Johnson - MITI and The Japanese Miracle - The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975-SUP (1982)Felipe AugustoNo ratings yet

- Clases RevoluciónDocument30 pagesClases RevoluciónvicenteNo ratings yet

- Satsuma RebellionDocument12 pagesSatsuma RebellionRuh Javier AlontoNo ratings yet

- Cambridge University Press Journal of Latin American StudiesDocument30 pagesCambridge University Press Journal of Latin American StudiesVictoria HerreraNo ratings yet

- The Emergence of Socialist Parties 1848-1914Document19 pagesThe Emergence of Socialist Parties 1848-1914kaushal yadavNo ratings yet

- Meiji Restoration in JapanDocument21 pagesMeiji Restoration in JapanRamita Udayashankar100% (5)

- Fascism in JapanDocument16 pagesFascism in JapanHISTORY TVNo ratings yet

- BCAS v14n03Document78 pagesBCAS v14n03Len HollowayNo ratings yet

- The Journal of Peasant Studies: To Cite This Article: Neil Charlesworth (1980) The Middle Peasant Thesis' andDocument24 pagesThe Journal of Peasant Studies: To Cite This Article: Neil Charlesworth (1980) The Middle Peasant Thesis' andRavi Naid GorleNo ratings yet

- Peasant Movements in Colonial India An Examination of Some Conceptual Frameworks L S Viishwanath 1990Document6 pagesPeasant Movements in Colonial India An Examination of Some Conceptual Frameworks L S Viishwanath 1990RajnishNo ratings yet

- SHELDON 1958 - The Rise of The Merchant Class in Tokugawa Japan, 1600-1868Document215 pagesSHELDON 1958 - The Rise of The Merchant Class in Tokugawa Japan, 1600-1868Floripondio19No ratings yet

- Plots and Motives in Japan's Meiji RestorationDocument22 pagesPlots and Motives in Japan's Meiji Restorationdash1011No ratings yet

- Japan A3Document8 pagesJapan A3AnoushkANo ratings yet

- Yoshida Shigeru - Transition To Liberal DemocracyDocument16 pagesYoshida Shigeru - Transition To Liberal DemocracyClaudiu AldeaNo ratings yet

- Nam IDocument18 pagesNam Igugoloth shankarNo ratings yet

- Scalice 2022 ADeliberatelyForgottenBattleDocument27 pagesScalice 2022 ADeliberatelyForgottenBattleRaj VillarinNo ratings yet

- B41 - Peruvian Labour and The Military Government Since 1968Document60 pagesB41 - Peruvian Labour and The Military Government Since 1968YakuAtokNo ratings yet

- Association For Asian Studies The Journal of Asian StudiesDocument22 pagesAssociation For Asian Studies The Journal of Asian StudieshoampimpaNo ratings yet

- Agricultural Modernization and Education by Krishna KumarDocument7 pagesAgricultural Modernization and Education by Krishna KumarRachel PhilipNo ratings yet

- Saito1 PortraitDocument13 pagesSaito1 PortraitMohit KharbandaNo ratings yet

- Stuart Laing (Auth.) - Representations of Working-Class Life 1957-1964-Macmillan Education UK (1986)Document246 pagesStuart Laing (Auth.) - Representations of Working-Class Life 1957-1964-Macmillan Education UK (1986)Yasmim CamardelliNo ratings yet

- Labor History and Its Challenges - Confessions of A Latin AmericanistDocument9 pagesLabor History and Its Challenges - Confessions of A Latin Americanistmayaraaraujo.historiaNo ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc. Modern China: This Content Downloaded From 128.210.126.199 On Tue, 28 Jun 2016 20:12:12 UTCDocument37 pagesSage Publications, Inc. Modern China: This Content Downloaded From 128.210.126.199 On Tue, 28 Jun 2016 20:12:12 UTCDavid SlobadanNo ratings yet

- The Meiji Restoration: Modernization & The Rise of Nationalism in JapanDocument10 pagesThe Meiji Restoration: Modernization & The Rise of Nationalism in JapanMuhammad AbbasNo ratings yet

- LMLA TextDocument15 pagesLMLA TextMaciej DrabińskiNo ratings yet

- National Planning in Brazil An Historical PerspectDocument40 pagesNational Planning in Brazil An Historical Perspectabrie6396No ratings yet

- The Making of Modern Japan - Pyle, KennethDocument212 pagesThe Making of Modern Japan - Pyle, KennethKunal100% (1)

- Tracing Your Labour Movement Ancestors: A Guide for Family HistoriansFrom EverandTracing Your Labour Movement Ancestors: A Guide for Family HistoriansNo ratings yet

- Jsis 242-Exam 1 Id TermsasdfDocument12 pagesJsis 242-Exam 1 Id TermsasdfTJ HookerNo ratings yet

- Summary of 'Asian Drama'Document14 pagesSummary of 'Asian Drama'Tushar KadamNo ratings yet

- Book Review 1 - SmethurstDocument3 pagesBook Review 1 - SmethurstpoojajoshimamcNo ratings yet

- Molding Japanese Minds: The State in Everyday LifeFrom EverandMolding Japanese Minds: The State in Everyday LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- 10 2307@657877 PDFDocument44 pages10 2307@657877 PDFlomahanaNo ratings yet

- PAOLI, MC - Labour, Law and The State in Brazil, 1930-1950-2Document459 pagesPAOLI, MC - Labour, Law and The State in Brazil, 1930-1950-2Danilo Lucena MendesNo ratings yet

- The Meiji Restoration EraDocument7 pagesThe Meiji Restoration Eradash1011No ratings yet

- Usa Assignment PDFDocument3 pagesUsa Assignment PDFAnurakti VajpeyiNo ratings yet

- Anarcho-Syndicalism in JapanDocument26 pagesAnarcho-Syndicalism in Japandidier75No ratings yet

- YONG CHING FATT - Leadership Chinese in SGDocument16 pagesYONG CHING FATT - Leadership Chinese in SGJustin LokeNo ratings yet

- Continuar Da Pagina 62Document102 pagesContinuar Da Pagina 62salvandohomensNo ratings yet

- Amateur Manga MovementDocument29 pagesAmateur Manga MovementAndreea SoareNo ratings yet

- The Panic of 1837Document32 pagesThe Panic of 1837vanveen1967No ratings yet

- Why Was There No Marxism in Great Britain ?Document35 pagesWhy Was There No Marxism in Great Britain ?ed whiteNo ratings yet

- Frank Upham, "The Man Who Would Import - A Cautionary Tale About Bucking The System in Japan", 17 Journal of Japanese StudiesDocument21 pagesFrank Upham, "The Man Who Would Import - A Cautionary Tale About Bucking The System in Japan", 17 Journal of Japanese StudiesYanxin ZhangNo ratings yet

- Japanese Emigration To Latin AmericaDocument45 pagesJapanese Emigration To Latin AmericaRene EudesNo ratings yet

- Higginson BringingWorkersBack 1988Document26 pagesHigginson BringingWorkersBack 1988ugabugaNo ratings yet

- Poor Man's Fortune: White Working-Class Conservatism in American Metal Mining, 1850–1950From EverandPoor Man's Fortune: White Working-Class Conservatism in American Metal Mining, 1850–1950No ratings yet

- Making A LivingDocument6 pagesMaking A LivingAlexandra G AlexNo ratings yet

- Peasants KolffDocument25 pagesPeasants KolffTanisha BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Merchants and Society in Tokugawa JapanDocument13 pagesMerchants and Society in Tokugawa JapanDexter ConlinNo ratings yet

- Dwps Next Mun 2024Document24 pagesDwps Next Mun 2024harsh242123No ratings yet

- Us Shipscrapping 44324691963170Document4 pagesUs Shipscrapping 44324691963170dbbony 0088No ratings yet

- Garrigus Oge Americas 2011Document32 pagesGarrigus Oge Americas 2011ansapa1025No ratings yet

- Michael Freeden and The Morphological ApproachDocument181 pagesMichael Freeden and The Morphological ApproachMark A. FosterNo ratings yet

- Hitler-Discurs 1933-Sportpalast Berlin-Transcriere Tip ImaginiDocument355 pagesHitler-Discurs 1933-Sportpalast Berlin-Transcriere Tip ImaginiLuca OctavianNo ratings yet

- Lord Curzon and The Creation of The North-West Frontier Province (1901) : An AppraisalDocument13 pagesLord Curzon and The Creation of The North-West Frontier Province (1901) : An AppraisalnadiasajjadNo ratings yet

- Ozamis CityDocument2 pagesOzamis CitySunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- A.V.M. Sales Corpn. v. Anuradha Chemicals (P) LTD., (2012) 2 SCC 315Document6 pagesA.V.M. Sales Corpn. v. Anuradha Chemicals (P) LTD., (2012) 2 SCC 315nidhidaveNo ratings yet

- The Hill We Climb Amanda GormanDocument3 pagesThe Hill We Climb Amanda GormanDS RoseNo ratings yet

- Interview Prog No.6-2024Document6 pagesInterview Prog No.6-2024Ali RazaNo ratings yet

- Miami BBG 10th Regional Board PacketsDocument10 pagesMiami BBG 10th Regional Board PacketsIlana LadisNo ratings yet

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocument2 pagesCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Affidavit: WHEREFORE, I Have Hereunto Set My Hand This 2Document1 pageAffidavit: WHEREFORE, I Have Hereunto Set My Hand This 2Patricia CastroNo ratings yet

- Despite Modi, India Has Not Yet Become A Hindu Authoritarian StateDocument28 pagesDespite Modi, India Has Not Yet Become A Hindu Authoritarian StateCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- DLL-Q3-W2 - Mam LouDocument8 pagesDLL-Q3-W2 - Mam LouChello Ann Pelaez AsuncionNo ratings yet

- PDF Askep Persalinan Beresiko - CompressDocument40 pagesPDF Askep Persalinan Beresiko - CompressAudini HerawatiNo ratings yet

- 9.19.16 Mayor Lee & Sup. Cohen Hunters Point Shipyard LetterDocument2 pages9.19.16 Mayor Lee & Sup. Cohen Hunters Point Shipyard Lettercb0bNo ratings yet

- Will Banyan - The Illusion of Elite Disunity - Elite FacyionalismThe War OnTerror and The New World OrderDocument34 pagesWill Banyan - The Illusion of Elite Disunity - Elite FacyionalismThe War OnTerror and The New World OrderPopolvuh89No ratings yet

- Republic of Kenya: Ministry of Interior and NationaladministrationDocument3 pagesRepublic of Kenya: Ministry of Interior and NationaladministrationWanNo ratings yet

- Contact Details of Booth Level Officers Blos and Their SupervisersDocument23 pagesContact Details of Booth Level Officers Blos and Their Superviserssanjana.gatty23No ratings yet

- Ir 05Document3 pagesIr 05warnakulasooriyaNo ratings yet

- Andhra PradeshDocument4 pagesAndhra PradeshBharath KumarNo ratings yet

- Sarawak Government Gazette: Mineral Ordinance 2004Document7 pagesSarawak Government Gazette: Mineral Ordinance 2004Alka PillaiNo ratings yet

- 2022 SEIKO Catalogue 24112022Document21 pages2022 SEIKO Catalogue 24112022Gula-gula KapasNo ratings yet

- Nutritional-Status - 8 Daffodils-2022-2023Document98 pagesNutritional-Status - 8 Daffodils-2022-2023Jose Ruel MendozaNo ratings yet

- Pradhan Mantri Aawas YojanaDocument13 pagesPradhan Mantri Aawas YojanaShivam ShanuNo ratings yet

- Export Client List - KDD Pump SystemDocument15 pagesExport Client List - KDD Pump SystemIlyas Rangga RamadhanNo ratings yet

- International Perspectives On Exclusionary Pressures in Education How Inclusion Becomes Exclusion Elizabeth J Done Full ChapterDocument52 pagesInternational Perspectives On Exclusionary Pressures in Education How Inclusion Becomes Exclusion Elizabeth J Done Full Chapterpamela.sevillano879100% (6)

- Manalo Extension, Barangay Milagrosa Puerto Princesa City, Palawan Tel. No. 048-434-2393Document2 pagesManalo Extension, Barangay Milagrosa Puerto Princesa City, Palawan Tel. No. 048-434-2393Alexander ExeveaNo ratings yet