Professional Documents

Culture Documents

What Factors Make Controversial Advertising Offensive

What Factors Make Controversial Advertising Offensive

Uploaded by

Fernanda CalmonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

What Factors Make Controversial Advertising Offensive

What Factors Make Controversial Advertising Offensive

Uploaded by

Fernanda CalmonCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/241161860

WHAT FACTORS MAKE CONTROVERSIAL ADVERTISING OFFENSIVE?: A

PRELIMINARY STUDY

Article · January 2004

CITATIONS READS

26 33,270

1 author:

David S Waller

University of Technology Sydney

109 PUBLICATIONS 2,643 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by David S Waller on 04 June 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

ANZCA04 Conference, Sydney, July 2004 1

WHAT FACTORS MAKE CONTROVERSIAL ADVERTISING OFFENSIVE?:

A PRELIMINARY STUDY

David S. Waller

School of Marketing

University of Technology, Sydney, Australia

ABSTRACT

While some advertisers have undertaken controversial advertising campaigns that have been

very successful, some have been damaging to the company. This is particularly important for

companies that have a controversial product, like condoms, feminine hygiene products and

underwear. This paper presents some preliminary results of a survey of 150 people to determine

whether they perceive particular sex/gender-related products as offensive, what are the reasons

to find advertisements offensive and discover correlations to ascertain why certain products are

perceived as offensive. The results, while preliminary, indicate some important issues for

advertisers.

INTRODUCTION

As the amount of advertising increases, it would appear that there has been an increase in the

amount of controversial advertising shown in various media. Some of reasons for this include

that society has become more complex, increased awareness of the harmful effects of some

products and as agencies try to become more creative to "cut through the clutter" to gain

attention and brand awareness (Waller 1999). For advertisers the problem can be that a

controversial advertising campaign can be very successful or very damaging, depending on what

ultimately happens in the marketplace. For example, the clothing company Benetton has long

been criticized for its advertising which uses controversial images to send a message of "social

concern" (Evans and Sumandeep 1993), until the death-row campaign was felt o have gone too

far (Curtis 2002). Similar problems occurred to Calvin Klein who had been criticized for running

campaigns with explicit sexual images, but had to publicly apologize after the outrage caused by

a campaign that was alleged to use images of child pornography (Anon 1995; Irvine 2000). The

result of a controversial advertising campaign can, therefore, be offence that can lead to a number

of actions like negative publicity, attracting complaints to advertising regulatory bodies, falling

sales, and product boycotts Advertisers wanting to undertake a controversial campaign must,

therefore, then tread the fine line between successfully communicating to the marketplace and

offending some people.

The issue for some advertisers and their agencies is to determine who may be offended by their

controversial campaign and what are the reasons for offence, particularly when the product itself

may be controversial, eg condoms and feminine hygiene products. To some extent the

advertisers, particularly those with controversial products, have a social responsibility not to

offend people by their advertising images, yet in a free market they should be able to

ANZCA04: Making a Difference

ANZCA04 Conference, Sydney, July 2004 2

communicate a message to their customers. This paper presents some preliminary finding on a

study of controversial advertising and what are the underlying reasons for offence towards the

advertising of particular products. The objective is to determine types of people who are

offended and the areas of offence to assist advertisers in making better managerial decisions

when is comes to deciding on a controversial advertising strategy.

ADVERTISING OF CONTROVERSIAL PRODUCTS

Some advertisers, by the nature of the product, may be perceived as controversial and any

promotion of their product may generate negative responses, for example cigarettes, alcohol,

condoms or feminine hygiene products (Schuster and Powell 1987; Wilson and West 1995).

Previous studies in this area have mainly looked at these products in terms of the products being

"unmentionables" (Wilson and West 1981; Alter 1982; Katsanis 1994; Wilson and West 1995;

Spain 1997), "decent products" (Shao 1993) "socially sensitive products" (Shao and Hill 1994a;

Shao and Hill 1994b; Fahy, Smart, Pride and Ferrell 1995), and "controversial products"

(Rehman and Brooks 1987). Wilson and West (1981) defined "unmentionables" as: "... products,

services, or concepts that for reasons of delicacy, decency, morality, or even fear tend to elicit

reactions of distaste, disgust, offence, or outrage when mentioned or when openly presented"

(p92). This definition has since been supported by Triff, Benningfield and Murphy (1987),

Fahy, Smart, Pride and Ferrell (1995) and Waller (1999). Katsanis (1994) also added that

“unmentionables” were “offensive, embarrassing, harmful, socially unacceptable or

controversial to some significant segment of the population”.

Waller (2003) noted that most of the research has observed “controversial advertising” as a

negative concept, and if controversial advertising resulted in only negative responses

advertisers would shy away from this type of campaign. However, advertisers are not shying

away but using it in increasing numbers. The use of controversial images has been successful

for a number of organizations in the past (for example, Evans and Sumandeep 1993; Hornery

1996; Waller 1999; Irvine 2000; McIntyre 2000; Phau and Prendergast 2001). This is

particularly important when the reason for controversy is based on the nature of the product.

Various types of products, both goods and services, have been suggested by past studies as

being controversial when advertised, including cigarettes, alcohol, contraceptives, underwear,

and political advertising. Fam, Waller and Erdogan (2002) used factor analysis to generate four

groups:

(1) Gender/Sex Related Products (eg. condoms, female contraceptives, male/female

underwear, and feminine hygiene products);

(2) Social/Political Groups (eg. political parties, religious denominations, funeral

services, racially extreme groups, and guns and armaments);

(3) Addictive Products (eg. alcohol, cigarettes, and gambling); and

(4) Health and Care Products (eg. Charities, sexual diseases (AIDS, STD prevention),

and weight loss programs).

Previous studies have also used these products as examples of controversial products. Wilson

and West (1981), in their study of "unmentionables", included "products" such as personal

hygiene and birth control. Feminine Hygiene Products was the main focus of Rehman and

ANZCA04: Making a Difference

ANZCA04 Conference, Sydney, July 2004 3

Brooks (1987), but also included undergarments, alcohol, pregnancy tests, contraceptives,

medications, and VD services, as examples of controversial products. When asked about the

acceptability of various products being advertised on television, only two products were seen as

unacceptable by a sample of college students: contraceptives for men and contraceptives for

women. Feminine Hygiene Products has also been mentioned in industry articles as having

advertisements that are in “poor taste”, “irritating” and “most hated” (Alter 1982; Aaker and

Bruzzone 1985; Hume 1988; Rickard 1994).

Shao (1993) and Shao and Hill (1994a) analyzed advertising agency attitudes regarding various

issues, including the legal restrictions of advertising of "sensitive" products, which can be

controversial for the agency that handles the account. The products/services discussed in these

studies were cigarettes, alcohol, condoms, female hygiene products, female undergarments, male

undergarments, sexual diseases (eg STD's, AIDS), and pharmaceutical goods.

Barnes and Dotson (1990) discussed offensive television advertising and identified two different

dimensions: offensive products and offensive execution. The products which were in their list

included condoms, female hygiene products, female undergarments, and male undergarments.

Phau and Prendergast (2001) found that products like cigarettes, alcohol, condoms, female

contraceptives, and feminie hygiene products, were perceived as controversial products that

could offend when being advertised, but included in their study sexual connotations, subject too

personal, evoking unnecessary fear, cultural sensitivity, indecent language, sexist images and

nudity. Waller (1999) presented a list of 15 controversial product that aimed to range from

extremely offensive to not very offensive: Alcohol, Cigarettes, Condoms, Female

Contraceptives, Female Hygiene Products, Female Underwear, Funeral Services, Gambling,

Male Underwear, Pharmaceuticals, Political Parties, Racially Extremist Groups, Religious

Denominations, Sexual Diseases (AIDS, STD Prevention), and Weight Loss Programs. He also

included six reasons for offence: Indecent Language, Nudity, Sexist, Racist, Subject Too Personal

and Anti-social Behavior.

In relation to who is offended, Fahy, Smart, Pride and Ferrell (1995) while researching

advertising of "sensitive products", asked a sample of over 2000 people their attitudes towards

the advertising on certain products on television. The products were grouped into three main

categories: alcoholic beverages, products directed at children and health/sex-related products.

Comparing the attitudes according to sex, age, income, region, education and race, they found

that women, particularly aged 50 and over, had much higher disapproval levels for such

commercials. Waller (1999) compared gender and found females were significantly more

offended than males by the reasons for offence than the controversial products.

The products to be used in the analysis for this study are gender/sex-related products:

Condoms, Female Hygiene Products, Female Underwear, and Male Underwear. These were

chosen as it was felt that these products may generate a stronger response of “offensiveness”

with respondents. A larger number of reasons were given to give the respondents more choice

and determine more specifically reasons for offence.

METHODOLOGY

ANZCA04: Making a Difference

ANZCA04 Conference, Sydney, July 2004 4

To obtain a measure of attitudes towards advertising of controversial products, a questionnaire

was distributed to a convenience sample of students at a large urban university. The rationale for

using university students as subjects has been a research method practiced overseas for many

years, mainly for their accessibility to the researcher and homogeneity as a group (Calder,

Phillips and Tybout 1981). Student samples have already been used in controversial

advertising studies by Rehman and Brooks (1987), Tinkham and Weaver-Lariscy (1994) and

Waller (1999). The use of students in a potential cross-cultural comparison of attitudes has

other advantages as it is accepted that purposive samples, such as with students, are superior

than random samples for establishing equivalence, and it controls a source of variation, thus is

more likely to isolate any cultural differences if they exist (Dant and Barnes 1988; Ramaprasad

and Hasegawa 1992).

A total of 150 students studying were sampled (73 male and 77 female). The average age of the

total sample was 21.87 years old (21.68 male and 22.05 female) with ages ranging from 18 to 40

years old. For ease of analysis the respondents were categorized grouped into two age groups:

21 or less and 22+. The sample is made up of primarily second and third year students and the

questionnaire took approximately 10 minutes to complete and was administered in a classroom

environment. The main two sections of the questionnaire comprised of a five point Likert type

format from which respondents were given (i) a list of products/services and (ii) a list of reasons

for offensive advertising. The respondents were asked to indicate their level of personal

"offence" on a five point scale, where 1 means "Not At All" offensive and 5 means "Extremely"

offensive. The list of reasons expands Waller (1999) to include 11 items: Anti-social Behaviour,

Concern for Children, Hard Sell, Health & Safety Issues, Indecent Language, Nudity, Racist

Image, Sexist Image, Stereotyping of People, Subject Too Personal, and Violence

RESULTS

Offensiveness of Products

Firstly the respondents were presented with the list of products for which they indicated their

level of offence. With a midpoint of 3 on the Likert scale, none of the products were perceived to

be offensive, which may be due to the sample being primarily young people in a cosmopolitan

western city. It also confirms Waller (1999) results. Condoms were perceived to be most

offensive when advertised, followed by Feminine Hygiene Products, Men’s Underwear and

Women’s Underwear (Table 1). Comparing gender the females were more offended by Condoms

and Women’s Underwear advertisements than the males at the .10 level. There were no

significant differences between the two age groups f 21 or less and 22+.

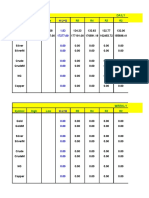

TABLE 1: OFFENSIVENESS OF ADVERTISEMENTS FOR

CONTROVERSIAL PRODUCTS

PRODUCT TOTAL Males Females 21 or less 22+

Condoms 2.52 2.32 2.71 * 2.57 2.45

(1.27) (1.18) (1.32) (1.28) (1.22)

Feminine Hygiene Products 2.36 2.48 2.24 2.35 2.33

ANZCA04: Making a Difference

ANZCA04 Conference, Sydney, July 2004 5

(1.27) (1.27) (1.26) (1.32) (1.20)

Men’s Underwear 2.13 2.19 2.07 2.02 2.23

(1.18) (1.25) (1.11) (1.18) (1.18)

Women’s Underwear 2.04 1.86 2.21 * 1.97 2.12

(1.21) (1.12) (1.28) (1.18) (1.28)

Mean (Standard Deviation)

*p<.100

Reasons for Offensiveness

Next the respondents were presented with the list of reasons for advertising offensiveness for

which they indicated their level of offence. With a midpoint of 3 on the Likert scale, the total

sample indicated offence to all of reasons except Anti-social Behavior (Table 2). Although a few

reasons were claimed to be not offensive by males and the younger age group, but these were

generally just under the midpoint and so indicating more of an indifference. Comparing gender,

females were significantly more offended than males for Sexist Image, Violence, Stereotyping of

People, Subject Too Personal, Indecent Language and Nudity. This can be due to the fact that

women are often the objects of the sexism, stereotyping and nudity. Looking at age, the older

group was significantly more offended by advertisements with Violence, Hard sell, Concern for

Children, and Anti-social Behavior. This would indicate the older group being more conservative

and more concerned with things like child welfare and anti-violence.

TABLE 2: REASONS FOR OFFENSIVENESS

PRODUCT TOTAL Males Females 21 or 22+

less

Racist Image 4.32 4.51 4.14 4.37 4.24

(2.59) (3.52) (1.16) (3.28) (.94)

Sexist Image 3.60 3.16 4.01 ** 3.64 3.53

(1.28) (1.36) (1.04) (1.35) (1.20)

Violence 3.55 3.16 3.91 ** 3.28 3.97 **

(1.33) (1.37) (1.19) (1.37) (1.18)

Stereotyping of People 3.38 3.14 3.60 ** 3.34 3.42

(1.12) (1.18) (1.03) (1.14) (1.13)

Hard Sell 3.24 3.37 3.11 2.99 3.59 **

(1.21) (1.26) (1.14) (1.20) (1.12)

Concern for Children 3.21 3.10 3.32 2.97 3.50 **

(1.41) (1.42) (1.40) (1.42) (1.35)

Subject Too Personal 3.13 2.84 3.42 ** 3.09 3.19

(1.21) (1.20) (1.15) (1.15) (1.32)

Indecent Language 3.11 2.77 3.43 ** 2.96 3.28

(1.23) (1.24) (1.14) (1.28) (1.14)

Nudity 3.06 2.64 3.45 ** 3.00 3.10

(1.31) (1.38) (1.12) (1.29) (1.36)

ANZCA04: Making a Difference

ANZCA04 Conference, Sydney, July 2004 6

Health & Safety Issues 3.02 2.85 3.19 2.97 3.11

(1.35) (1.34) (1.34) (1.32) (1.40)

Anti-social Behaviour 2.94 2.92 2.96 2.71 3.30 **

(1.27) (1.22) (1.32) (1.29) (1.19)

*p<.020

Correlating Products and Reasons for Offence

To help determine what makes controversial advertising offensive, a correlation of the results

between the four controversial products and reasons for the offence was made using a

Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient (Table 3). Strong relationships (greater than 0.30) were

found between Condoms with Indecent Language, Nudity, Sexist Images and Subject Too

Personal; as well as Women’s Underwear and Nudity. Other significant relationships (p<.01)

were found with Feminine Hygiene Products and Hard Sell; Men’s Underwear with Anti-

social Behavior and Subject Too Personal; and Women’s Underwear with Indecent Language,

Sexist Image, Stereotyping of People and Subject Too Personal.

TABLE 3: CORRELATION OF RODUCTS AND REASONS FOR OFFENSIVENESS

PRODUCT Condoms Feminine Men’s Women’s

Hygiene Underwear Underwear

Products

Anti-social Behaviour .107 .117 .231 ** .113

(.199) (.156) (.005) (.171)

Concern for Children .194 * .065 .035 -.005

(.018) (.428) (.668) (.948)

Hard Sell .083 .242 ** .120 .156

(.327) (.004) (.155) (.063)

Health & Safety Issues .107 .111 .108 .111

(.200) (.181) (.192) (.179)

Indecent Language .399 ** .011 .093 .289 **

(.000) (.890) (.260) (.000)

Nudity .418 ** .097 .157 .421 **

(.000) (.243) (.057) (.000)

Racist Image .168 * .073 .016 .113

(.042) (.374) (.844) (.171)

Sexist Image .307 ** .148 .075 .271 **

(.000) (.071) (.360) (.001)

Stereotyping of People .171 * .071 .151 .219 **

(.038) (.391) (.067) (.008)

Subject Too Personal .434 ** .207 * .266 ** .240 **

(.000) (.011) (.001) (.003)

Violence .170 * -.007 .119 .098

ANZCA04: Making a Difference

ANZCA04 Conference, Sydney, July 2004 7

(.040) (.928) (.150) (.233)

Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient

(Sig. – 2-tailed)

* p<.05

** p<.01

CONCLUSION

Overall, it appears this study has shown that while those sampled indicated that they did not

feel particular controversial products were offensive when advertised, but they did find

particular reasons for advertisements being offensive. Therefore, the respondents perceive the

reasons given as more of an indication of why an advertisement is personally offensive than the

controversial products, which supports Waller (1999). Also there were significant differences in

the responses with gender being more of a determinant of offensiveness than age for indicating

offence, with women being more offended compared to the men’s responses.

To determine what makes controversial advertising offensive a correlation of the results

between the four controversial products and reasons for the offence was made using a

Spearman’s Correlation Coefficient with a number of relationships being indicated. In

particular strong relationships were found between Condoms with Indecent Language,

Nudity, Sexist Images and Subject Too Personal; as well as Women’s Underwear and Nudity.

For those involved with controversial products or controversial campaigns, it appears that they

should be aware of the potential to offend the public. Although some campaigns aim to be

controversial, care should be made to ensure that they are not Racist, Sexist, or have violent

images, particularly when targeting the female market. Offending the public can result in a drop

in sales or,

at an extreme, a boycotting of the product, which can then reflect poorly on the brand, the

company and the agency behind the campaign. Those companies with controversial products

should also be aware of what issues are the ones that offend their customers, and be socially

responsible enough to refrain from openly being offensive. For example, Condom manufacturers

should run advertisements that refrain from having indecent language, nudity, sexist images

and talking about the product too personally. However, it is still up to the advertiser to decide

on the right strategy for their controversial product.

Further research should be undertaken into attitudes towards controversial products and

offensive advertising. This could take the form of measuring levels of offensiveness towards

specific advertisements, comparing offensiveness with various demographics, such as age,

religion, personality, location, etc, and a cross-cultural comparison to determine if view hold

across different countries/cultures. From an advertiser’s view it is important to develop an

understanding of the relationship between their advertising messages and their customers, and

undertake some social responsibility for the messages being resented. The last thing an advertiser

would want to do is to offend its customers and cause a negative reaction in the marketplace.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ANZCA04: Making a Difference

ANZCA04 Conference, Sydney, July 2004 8

Aaker, David A. and Donald E. Bruzzone (1985) “Causes of Irritation in Advertising”,

Journal of Advertising, 49 (Spring): 47-57.

Alter, J. (1982) "A Delicate Balance: Not Everything Goes in the Marketing of

`Unmentionables'", Advertising Age, 12 July, M3-M8.

Anonymous (1995) "US Pressure Group Forces Calvin Klein to Drop 'Porn'Ads", Campaign,

1 September, 2.

Barnes, J.H. and M.J. Dotson (1990) "An Exploratory Investigation into the Nature of

Offensive Television Advertising", Journal of Advertising, 19 (3), 61-69.

Calder, B. J., Phillips, L. W. & Tybout, A. M. (1981) "Designing Research for Applications",

Journal of Consumer Research, 8, September: 197-207.

Curtis, Maree (2002) “Blood Sweaters and Tears”, Sunday Magazine – The Sunday

Telegraph, 21 July: 22-26.

Dant, R. P., & Barnes, J. H. (1988) "Methodological Concerns in Cross-Cultural Research:

Implications for Economic Development", in Erdogan Kumcu & A. Fuat Firat (eds),

Marketing and Development: Towards Broader Dimensions, Greenwich CT: Jai Press Inc.

Evans, I.G. and R Sumandeep (1993) "Is The Message Being Received? Benetton Analysed",

International Journal of Advertising, 12 (4), 291-301.

Fahy, John, Denise Smart, William Pride and O.C. Ferrell (1995) "Advertising Sensitive

Products", International Journal of Advertising, 14, pp231-243.

Fam, Kim Shyan, David S. Waller and B. Zafer Erdogan (2002) “A Cross-Cultural

Comparison of Attitudes Towards the Advertising of Controversial Products”, paper

presented at International Advertising Association (IAA) Regional Educational Conference,

Sydney, September.

Hornery, Andrew (1996) "But Wait, Why's There More Outrage Than Laughter?", The

Sydney Morning Herald, 20 January, 4.

Hume, S. (1988), “Most Hated Ads: Feminine Hygiene”, Advertising Age, 18 July: 1.

Irvine, Susan (2000) “The Black Prince”, Good Weekend, 8 April: 54-55, 57, 58.

Katsanis, L.P. (1994) "Do Unmentionable Products Still Exist? An Empirical Investigation",

Journal of Product and Brand Management, 3 (4), 5-14.

McIntyre, Paul (2000) "Buy Sexual", The Australian Magazine 27-28 May, 26-29.

ANZCA04: Making a Difference

ANZCA04 Conference, Sydney, July 2004 9

Phau, Ian and Prendergast, Gerard (2001) “Offensive Advertising: A View from Singapore”,

Journal of Promotion Management, 7(1/2), 71-90.

Ramaprasad, Jyotika & Kazumi Hasegawa (1992) "The Youth Market: A Study of American

and Japanese Students as Consumers", paper presented at the Conference of the American

Academy of Advertising, San Antonio, Texas.

Rehman, S.N. and J.R. Brooks (1987) "Attitudes Towards Television Advertising for

Controversial Products", Journal of Healthcare Marketing, 7, 78-83.

Rickard, L. (1994) “Consumers Would Rather Skip Feminine Hygiene Ads”, Advertising Age,

65 (11), March 14, 29.

Schuster, Camille P. and Christine Pacelli Powell (1987) “Comparison of Cigarette and

Alcohol Advertising Controversies”, Journal of Advertising, 16 (2), 26-33.

Shao, Alan T. (1993) "Restrictions on Advertising Items That May Not Be Considered

`Decent': A European Viewpoint", Journal of Euromarketing, 2 (3), 23-43.

Shao, Alan T. and John S. Hill (1994a) "Global Television Advertising restrictions: The Case

of Socially Sensitive Products", International Journal of Advertising, 13, 347-366.

Shao, Alan T. and John S. Hill (1994b) "Advertising Sensitive Products in Magazines: Legal

and Social Restrictions", Multinational Business Review, Fall, 16-24.

Spain, W. (1997) "Unmentionables' Ads Making Their Way Onto Cable", Advertising Age,

14 April, s6.

Tinkham, Spencer F. & Ruth Ann Weaver-Lariscy (1994) "Ethical Judgements of Political

Television Commercials as Predictors of Attitude Toward the Ad", Journal of Advertising, 23

(3), September, 43-57.

Triff, M., D. Benningfield and J.H. Murphy (1987) "Advertising Ethics: A Study of Public

Attitudes and Perceptions", The Proceedings of the 1987 Conference of the American

Academy of Advertising, Columbia, South Carolina.

Waller, David S. (2003) “A Proposed Response Model For Controversial Advertising”,

Journal of Promotion Management, Vol 10 No1, forthcoming.

Waller, David S. (1999) "Attitudes Towards Offensive Advertising: An Australian Study",

Journal of Consumer Marketing, 16 (3), 288-294.

Wilson, Aubrey and Christopher West (1981) "The Marketing of `Unmentionables'",

Harvard Business Review, January/February, 91-102.

ANZCA04: Making a Difference

ANZCA04 Conference, Sydney, July 2004 10

Wilson, Aubrey and Christopher West (1995) “Commentary: Permissive Marketing - The

Effects of the AIDS Crisis on Marketing Practices and Messages”, Journal of Product and

Brand Management, 4:5, 34-48.

ANZCA04: Making a Difference

View publication stats

You might also like

- Technical Regulation For Machinery Safety - Part 1: Portable And/or Hand-Oriented MachinesDocument53 pagesTechnical Regulation For Machinery Safety - Part 1: Portable And/or Hand-Oriented MachinesEyad OsNo ratings yet

- Controlling Sex and Decency in Advertising Around The WorldDocument12 pagesControlling Sex and Decency in Advertising Around The WorldShwetha ShekharNo ratings yet

- Blake EletronicsDocument10 pagesBlake EletronicsParkbyun HanaNo ratings yet

- ZBNFDocument30 pagesZBNFsureshkm100% (3)

- Elliotts Letter To MPC 09252019Document3 pagesElliotts Letter To MPC 09252019Tom TsakopoulosNo ratings yet

- CIA Learning SystemDocument49 pagesCIA Learning Systemkae100% (2)

- Attitudes Towards Offensive Advertising: An Australian StudyDocument7 pagesAttitudes Towards Offensive Advertising: An Australian StudyNikmatur RahmahNo ratings yet

- Controversial Advertisement: Presented By: Sakshi Mehta Neha Narang Simerjeet Khurana Saviny ManglaDocument24 pagesControversial Advertisement: Presented By: Sakshi Mehta Neha Narang Simerjeet Khurana Saviny Manglasakshimehta07No ratings yet

- How To Make Advertising More Effective:shock AdvertisingDocument52 pagesHow To Make Advertising More Effective:shock Advertisingthebuzzingbee5743100% (1)

- ShockDocument14 pagesShockRoberta Lemgruber VilelaNo ratings yet

- Ethics Viral AdvertisingDocument6 pagesEthics Viral Advertisingkduke748No ratings yet

- Humann and Mott-Stenerson 2008 PDFDocument23 pagesHumann and Mott-Stenerson 2008 PDFShahin SamadliNo ratings yet

- Ethic Issues in AdvertisingDocument12 pagesEthic Issues in AdvertisingazamabdrahimNo ratings yet

- Celebrity Endorsements in U.S. and Thai Magazines: A Content Analysis Comparative AssessmentDocument16 pagesCelebrity Endorsements in U.S. and Thai Magazines: A Content Analysis Comparative AssessmentMaduni GurugeNo ratings yet

- Controversial Advert Perceptions in SNS AdvertisingDocument17 pagesControversial Advert Perceptions in SNS AdvertisingmaychoisshopNo ratings yet

- Ijmra 11863Document10 pagesIjmra 11863burhanuddinbombaywalaNo ratings yet

- Revised MRDocument50 pagesRevised MRapi-291981727No ratings yet

- Celebrity Endorser and Its Impact On Company, Behavioral and Attitudinal VariablesDocument20 pagesCelebrity Endorser and Its Impact On Company, Behavioral and Attitudinal VariablesVirendra ChavdaNo ratings yet

- Brand ExtensionDocument37 pagesBrand ExtensionVirang SahlotNo ratings yet

- Advertising of Controversial Products: A Cross-Cultural StudyDocument8 pagesAdvertising of Controversial Products: A Cross-Cultural StudyRavi GuptaNo ratings yet

- Neha Jain (Controversial Advertisement)Document41 pagesNeha Jain (Controversial Advertisement)Neha JainNo ratings yet

- Brand Positioning Through Celebrity Endorsement - A Review Contribution To Brand LiteratureDocument17 pagesBrand Positioning Through Celebrity Endorsement - A Review Contribution To Brand LiteraturesuccessseakerNo ratings yet

- Sex in AdvertisingDocument16 pagesSex in AdvertisingBaraheen E Qaati'ahNo ratings yet

- Ethical Violations in Advertising - Nature, Consequences, and PerspectivesDocument48 pagesEthical Violations in Advertising - Nature, Consequences, and PerspectivesRaj K GahlotNo ratings yet

- Csr-Case Study Research Study 1Document4 pagesCsr-Case Study Research Study 1api-300476144No ratings yet

- Here's The Beef: Factors, Determinants, and Segments in Consumer Criticism of AdvertisingDocument16 pagesHere's The Beef: Factors, Determinants, and Segments in Consumer Criticism of AdvertisingAli ANo ratings yet

- Consumer Attitude Towards Celebrity Endorsement On Social Media PDFDocument55 pagesConsumer Attitude Towards Celebrity Endorsement On Social Media PDFShaloni Jain100% (1)

- Solution Manual For M Advertising 2nd Edition Arens Schaefer Weigold 0078028965 9780078028960Document36 pagesSolution Manual For M Advertising 2nd Edition Arens Schaefer Weigold 0078028965 9780078028960briannastantonjeizaxomrb100% (34)

- Solution Manual For M Advertising 2Nd Edition Arens Schaefer Weigold 0078028965 9780078028960 Full Chapter PDFDocument36 pagesSolution Manual For M Advertising 2Nd Edition Arens Schaefer Weigold 0078028965 9780078028960 Full Chapter PDFjohn.burrington722100% (22)

- M Advertising 2nd Edition Arens Schaefer Weigold Solution ManualDocument22 pagesM Advertising 2nd Edition Arens Schaefer Weigold Solution Manualronald100% (30)

- Greenwashing As A PhenomenonDocument9 pagesGreenwashing As A PhenomenoncarlataljaardNo ratings yet

- Personal Brands: An Exploratory Analysis of Personal Brands in Australian Political MarketingDocument8 pagesPersonal Brands: An Exploratory Analysis of Personal Brands in Australian Political MarketingCẩm Tú ĐặngNo ratings yet

- Impact of Advertising On Consumers' Buying Behavior Through Persuasiveness, Brand Image, and Celebrity EndorsementDocument10 pagesImpact of Advertising On Consumers' Buying Behavior Through Persuasiveness, Brand Image, and Celebrity Endorsementvikram singhNo ratings yet

- MaterialDocument4 pagesMaterialajayNo ratings yet

- Ad Skepticism The Consequences of DisbeliefDocument17 pagesAd Skepticism The Consequences of DisbeliefvarshaalakshmipathyNo ratings yet

- Advertsiement Skepticism and Brand Extension Evaluation - Versao - Enanpad - 2013 - VF1Document16 pagesAdvertsiement Skepticism and Brand Extension Evaluation - Versao - Enanpad - 2013 - VF1Caio Henrique Noronha JuniorNo ratings yet

- Why The Tort System Is Important: P.O. Box 3326 - Church Street Station - New York, NY 10008-3326Document2 pagesWhy The Tort System Is Important: P.O. Box 3326 - Church Street Station - New York, NY 10008-3326Dennis KimamboNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Role of Sex Appeal in Marketing CommunicationsDocument27 pagesAssessing The Role of Sex Appeal in Marketing CommunicationsCitizenNo ratings yet

- Elliot Richard - Media Amplification of A Brand CrisisDocument18 pagesElliot Richard - Media Amplification of A Brand CrisisBrăescuBogdanNo ratings yet

- ISSUE 31 PART 1NafisehNourozi8724 8732Document10 pagesISSUE 31 PART 1NafisehNourozi8724 8732varshaalakshmipathyNo ratings yet

- Impact of Celebrity EndorsementDocument10 pagesImpact of Celebrity EndorsementrahulNo ratings yet

- An Ethical Evaluation of Product PlacemeDocument18 pagesAn Ethical Evaluation of Product Placememadihaadnan1No ratings yet

- Dwnload Full M Advertising 2nd Edition Arens Solutions Manual PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full M Advertising 2nd Edition Arens Solutions Manual PDFhenrycamb22100% (16)

- M Advertising 2nd Edition Arens Solutions ManualDocument35 pagesM Advertising 2nd Edition Arens Solutions Manualgenepetersfkxr33100% (28)

- Negative Word-Of-Mouth and Redress Strategies: An Exploratory Comparison of French Versus American ManagersDocument15 pagesNegative Word-Of-Mouth and Redress Strategies: An Exploratory Comparison of French Versus American ManagersSamir AlexNo ratings yet

- Global Media Journal Vol. 6 (2) :149 December 2013: Shumaila Ahmed and Ayesha AshfaqDocument9 pagesGlobal Media Journal Vol. 6 (2) :149 December 2013: Shumaila Ahmed and Ayesha AshfaqsarmithamalaiNo ratings yet

- Australia Beer Sexist PDFDocument13 pagesAustralia Beer Sexist PDFfranco12453No ratings yet

- Chau Fatimah - Sukd1902342 - AaDocument11 pagesChau Fatimah - Sukd1902342 - Aa11 ChiaNo ratings yet

- Imc Analysis of DurexDocument14 pagesImc Analysis of DurexHà My NguyễnNo ratings yet

- 1 - IMR Halal Paper Jan 2 BBS 1-5-15 FinalDocument32 pages1 - IMR Halal Paper Jan 2 BBS 1-5-15 Finalerlopez100% (1)

- M Advertising 2nd Edition Arens Solutions ManualDocument25 pagesM Advertising 2nd Edition Arens Solutions ManualJessicaGarciabtcmr100% (61)

- Chapter 2 StructureDocument6 pagesChapter 2 StructureshinttopNo ratings yet

- PR EthicsDocument33 pagesPR Ethicsphuogbe099No ratings yet

- Offensive Advertising An Legal Environment Project by Mansi Bengali 103 TybmmDocument14 pagesOffensive Advertising An Legal Environment Project by Mansi Bengali 103 TybmmKatie1901No ratings yet

- WP 26-2007 ShacharDocument36 pagesWP 26-2007 ShacharDustin DavisNo ratings yet

- Is CompileDocument50 pagesIs CompileCik MieNo ratings yet

- M Advertising 3rd Edition Schaefer Solutions ManualDocument74 pagesM Advertising 3rd Edition Schaefer Solutions ManualJustinMillerfjoea100% (14)

- Socio-Economic and Ethical Implications of Advertising - A Perceptual StudyDocument15 pagesSocio-Economic and Ethical Implications of Advertising - A Perceptual StudyAnkit AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Dan Horsky and Leonard S. Simon - Advertising and The Diffusion of New ProductsDocument18 pagesDan Horsky and Leonard S. Simon - Advertising and The Diffusion of New ProductsDana ConstantinNo ratings yet

- Sales Promotion Effectiveness The Impact of ConsumDocument39 pagesSales Promotion Effectiveness The Impact of ConsumMohola Tebello GriffithNo ratings yet

- Public Relations Consultant in NYC Resume Wendie OwenDocument4 pagesPublic Relations Consultant in NYC Resume Wendie OwenWendieOwenNo ratings yet

- 52.developing and Validating A Scale of Consumer Brand Embarrassment TendenciesDocument10 pages52.developing and Validating A Scale of Consumer Brand Embarrassment TendenciesBlayel FelihtNo ratings yet

- The Whistleblowing Guide: Speak-up Arrangements, Challenges and Best PracticesFrom EverandThe Whistleblowing Guide: Speak-up Arrangements, Challenges and Best PracticesNo ratings yet

- Strong Medicine: Creating Incentives for Pharmaceutical Research on Neglected DiseasesFrom EverandStrong Medicine: Creating Incentives for Pharmaceutical Research on Neglected DiseasesRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1)

- More Than You Wanted to Know: The Failure of Mandated DisclosureFrom EverandMore Than You Wanted to Know: The Failure of Mandated DisclosureRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Free Ebook Affiliate MarketingDocument19 pagesFree Ebook Affiliate MarketingNoor-ul HudaNo ratings yet

- Partnership Fundamental Worksheet 1Document2 pagesPartnership Fundamental Worksheet 1kena0% (1)

- DuplicateBill Jan 2024 0400017071627Document2 pagesDuplicateBill Jan 2024 0400017071627hk3737253No ratings yet

- Inorman - Managing The MArketing FunctionDocument10 pagesInorman - Managing The MArketing FunctionGilbert CalosaNo ratings yet

- Indicative Programme: Day 1 (November 18, 2021) : Barangay Development Planning Time Topic DiscussantDocument2 pagesIndicative Programme: Day 1 (November 18, 2021) : Barangay Development Planning Time Topic DiscussantVinvin EsoenNo ratings yet

- Indian Bank - Print ChallanDocument1 pageIndian Bank - Print Challandineshtk04No ratings yet

- DCB Bank Announces First Quarter Results FY 2021 22 Mumbai August 0 2021Document7 pagesDCB Bank Announces First Quarter Results FY 2021 22 Mumbai August 0 2021anandNo ratings yet

- Public Private PartnershipsDocument22 pagesPublic Private PartnershipsPeter MutuiNo ratings yet

- Vietnam TourDocument10 pagesVietnam TourHerbert AlcatrasNo ratings yet

- Practical Guide To Project ManagementDocument236 pagesPractical Guide To Project Managementsantosh_kecNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 Costs: Table 11.1 Description of Selected Aircraft Tires (App. A) Tire Type Aircraft Application Cost, $Document2 pagesChapter 11 Costs: Table 11.1 Description of Selected Aircraft Tires (App. A) Tire Type Aircraft Application Cost, $Raniero FalzonNo ratings yet

- Company Law and Corporate Governance - Cia 3Document12 pagesCompany Law and Corporate Governance - Cia 3harjas singhNo ratings yet

- Retail Format: Presented By: Ayush Shrivastava Bhanusree Lohia Diksha Jiwtode Divisha RastogiDocument8 pagesRetail Format: Presented By: Ayush Shrivastava Bhanusree Lohia Diksha Jiwtode Divisha RastogiKrati GugnaniNo ratings yet

- 310611320518754RPOSDocument4 pages310611320518754RPOSJasleen KaurNo ratings yet

- CHRYSLER COMMERCIAL VEHICLES Section 179 Deduction OptionsDocument1 pageCHRYSLER COMMERCIAL VEHICLES Section 179 Deduction OptionsswiftNo ratings yet

- Inventory Management System (3) - 2Document4 pagesInventory Management System (3) - 2iraoui jamal (Ebay)No ratings yet

- Audit Process - Psba PDFDocument46 pagesAudit Process - Psba PDFMariciele Padaca AnolinNo ratings yet

- INSTA July 2022 Current Affairs Quiz QuestionsDocument21 pagesINSTA July 2022 Current Affairs Quiz Questionsprashanth kenchotiNo ratings yet

- Symbol High Low R5 R4 R3 R2: DailyDocument8 pagesSymbol High Low R5 R4 R3 R2: Daily257597 rmp.mech.16No ratings yet

- Supply and Demand TogetherDocument6 pagesSupply and Demand TogetherQuang ĐạiNo ratings yet

- Cosmetic Manufacturers in India - Private Label Skin CareDocument10 pagesCosmetic Manufacturers in India - Private Label Skin CareCosmetifyNo ratings yet

- JollibeeDocument15 pagesJollibeesweety_cha1984% (19)

- Case Study: Implementation of Poka Yoke in Textile IndustryDocument11 pagesCase Study: Implementation of Poka Yoke in Textile IndustryJyoti RawalNo ratings yet

- Jet Lounge ListDocument1 pageJet Lounge ListManas NayakNo ratings yet

- Driving Breakthrough Performance in The New Work Environment CompressDocument26 pagesDriving Breakthrough Performance in The New Work Environment Compresshelen bollNo ratings yet