Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2014 Profilaxis Antibiotica en Endocarditis Infecciosa

2014 Profilaxis Antibiotica en Endocarditis Infecciosa

Uploaded by

Carlos AlfaroCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Glock Armorer's Manual Gen 1-5 2018Document140 pagesGlock Armorer's Manual Gen 1-5 2018Rachel Symes100% (3)

- BIO102 Practice ExamDocument10 pagesBIO102 Practice ExamKathy YuNo ratings yet

- Infective Endocarditis and Dental Procedures: Evidence, Pathogenesis, and PreventionDocument10 pagesInfective Endocarditis and Dental Procedures: Evidence, Pathogenesis, and PreventionSarah Ariefah SantriNo ratings yet

- Beatriz 2016 - Bacteremia Và Phẫu Thuật MiệngDocument30 pagesBeatriz 2016 - Bacteremia Và Phẫu Thuật MiệngPhong TruongNo ratings yet

- Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis: Sadewantoro, DR, SP - JPDocument25 pagesSubacute Bacterial Endocarditis: Sadewantoro, DR, SP - JPfelicedaNo ratings yet

- Infective Endocarditis Today (Version 1 Peer Review: 1 Not Approved)Document9 pagesInfective Endocarditis Today (Version 1 Peer Review: 1 Not Approved)preetNo ratings yet

- Jamacardiology Sperotto 2024 Oi 240019 1712241905.81501Document12 pagesJamacardiology Sperotto 2024 Oi 240019 1712241905.81501lakshminivas PingaliNo ratings yet

- Otitis ExternaDocument4 pagesOtitis ExternaCesar Mauricio Daza CajasNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical Cases and ReportsDocument4 pagesJournal of Clinical Cases and ReportsDonny RamadhanNo ratings yet

- The Risk For Endocarditis in Dental PracticeDocument9 pagesThe Risk For Endocarditis in Dental PracticeisanreryNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Dentoalveolar Surgery: Michael G. Savage, DDSDocument10 pagesAntibiotic Prophylaxis in Dentoalveolar Surgery: Michael G. Savage, DDSCriissthiiann HernnandezNo ratings yet

- OM Stafilococo (Clase Observacionales)Document7 pagesOM Stafilococo (Clase Observacionales)Jairo Camilo Guevara FaríasNo ratings yet

- antbioDocument16 pagesantbioefonseca2No ratings yet

- Fimmu 13 915081Document15 pagesFimmu 13 915081Zakia MaharaniNo ratings yet

- Antibiotics in Endodontics: A ReviewDocument16 pagesAntibiotics in Endodontics: A ReviewHisham HameedNo ratings yet

- ADJ-odontogenic InfectionDocument9 pagesADJ-odontogenic Infectiondr.chidambra.kapoorNo ratings yet

- 5fa2d32c9e2ea IJAR-33917Document9 pages5fa2d32c9e2ea IJAR-33917Sharanya BoseNo ratings yet

- Research and Reviews: Journal of Dental SciencesDocument7 pagesResearch and Reviews: Journal of Dental SciencesParastikaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2667147621000510 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S2667147621000510 MainDiahNo ratings yet

- Joint InfectionsDocument10 pagesJoint InfectionsJPNo ratings yet

- 325 FullDocument20 pages325 FullDessyadoeNo ratings yet

- Acute Mastoiditis in Children: Pasquale Cassano, Giorgio Ciprandi, Desiderio PassaliDocument6 pagesAcute Mastoiditis in Children: Pasquale Cassano, Giorgio Ciprandi, Desiderio PassaliSyafira AlimNo ratings yet

- Head and Neck AbsesDocument8 pagesHead and Neck AbsesNandaNo ratings yet

- Jced 9 E319Document6 pagesJced 9 E319sorayahyuraNo ratings yet

- Peacock Et Al-2016-Oral DiseasesDocument23 pagesPeacock Et Al-2016-Oral DiseasesGgg2046No ratings yet

- Reaching A BetterDocument6 pagesReaching A BetterAdyas AdrianaNo ratings yet

- Orthodontic Care For Medically Compromised Patients: ReviewDocument12 pagesOrthodontic Care For Medically Compromised Patients: ReviewAkram AlsharaeeNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Disease and The Role of Oral BacteriaDocument14 pagesCardiovascular Disease and The Role of Oral BacteriaOdonto BrunaNo ratings yet

- A Literature Review On Periodontitis and SystemicDocument3 pagesA Literature Review On Periodontitis and SystemicAfolabi Horlarmilekan AbdulbasitNo ratings yet

- Perio MedicineDocument90 pagesPerio MedicineAnsh Veer ChouhanNo ratings yet

- PIIS1201971214016713Document9 pagesPIIS1201971214016713Serque777No ratings yet

- 3.casual or Causal Relationship Between Periodontal Infection and Non Oral DiseaseDocument3 pages3.casual or Causal Relationship Between Periodontal Infection and Non Oral DiseaseEstherNo ratings yet

- Articulo ImportanteDocument8 pagesArticulo ImportanteTed SilvaNo ratings yet

- Nihms976360 PDFDocument17 pagesNihms976360 PDFyenny handayani sihiteNo ratings yet

- 6 SaDocument9 pages6 SaRizqi AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Cirugia OdDocument7 pagesCirugia OdDaniela Faundez VilugronNo ratings yet

- Interactions Between Neutrophils and Periodontal Pathogens in Late-Onset PeriodontitisDocument11 pagesInteractions Between Neutrophils and Periodontal Pathogens in Late-Onset PeriodontitisAdriana NoelNo ratings yet

- Systemic Diseases Caused by Oral InfectionDocument12 pagesSystemic Diseases Caused by Oral InfectionaninuraniyahNo ratings yet

- Periodontal Disease and Its Prevention, by Traditional and New Avenues (Review)Document3 pagesPeriodontal Disease and Its Prevention, by Traditional and New Avenues (Review)Louis Hutahaean100% (1)

- CO - Endocarditis in Critically Ill PatientsDocument8 pagesCO - Endocarditis in Critically Ill PatientsRomán Wagner Thomas Esteli ChávezNo ratings yet

- Antibiotics 10 01298 v3Document15 pagesAntibiotics 10 01298 v3Daniel AtiehNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Dentoalveolar SurgeryDocument10 pagesAntibiotic Prophylaxis in Dentoalveolar SurgeryDario Fernando HernandezNo ratings yet

- Infective EndocarditisDocument7 pagesInfective EndocarditisDwi Permana PutraNo ratings yet

- Posición Ante Los Antibióticos 2016Document40 pagesPosición Ante Los Antibióticos 2016Sydney LópezNo ratings yet

- Infective EndocarditisDocument16 pagesInfective EndocarditisAnnisa UlfaNo ratings yet

- Odontogenic Necrotizing Fasciitis: A Systematic Review of The LiteratureDocument7 pagesOdontogenic Necrotizing Fasciitis: A Systematic Review of The LiteratureDenta HaritsaNo ratings yet

- SJAMS 66 2563 2566 C PDFDocument4 pagesSJAMS 66 2563 2566 C PDFVitta Kusma WijayaNo ratings yet

- Case Study MHPTDocument10 pagesCase Study MHPTHalfIeyzNo ratings yet

- Fungal Endocarditis Current ChallengesDocument5 pagesFungal Endocarditis Current ChallengesmarnixvonkempNo ratings yet

- Fungi PDFDocument6 pagesFungi PDFnilnaNo ratings yet

- Periodontitis, Bacteremia and Infective Endocarditis: A Review StudyDocument8 pagesPeriodontitis, Bacteremia and Infective Endocarditis: A Review StudyAndra AgheorghieseiNo ratings yet

- Pubmed EndokarditisDocument7 pagesPubmed EndokarditisNayaka AriyaNo ratings yet

- Trop Med 140515Document10 pagesTrop Med 140515Arfa AlyaNo ratings yet

- WF10 (Immunokine) On Diabetic Foot UlcerDocument6 pagesWF10 (Immunokine) On Diabetic Foot UlcerRonal PerinoNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Little and Falaces Dental Management of The Medically Compromised Patient 8th Edition Little Test Bank PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full Little and Falaces Dental Management of The Medically Compromised Patient 8th Edition Little Test Bank PDFdanagarzad90y100% (13)

- Staphylococcus Epidermidis: Bio®lms: Importance and ImplicationsDocument6 pagesStaphylococcus Epidermidis: Bio®lms: Importance and Implicationsferro indahNo ratings yet

- Severe Intracranial and Extracranial Complications of The Middle Ear Cholesteatoma A Report CaseDocument5 pagesSevere Intracranial and Extracranial Complications of The Middle Ear Cholesteatoma A Report CaseChoirul UmamNo ratings yet

- Little and Falaces Dental Management of The Medically Compromised Patient 8th Edition Little Test BankDocument36 pagesLittle and Falaces Dental Management of The Medically Compromised Patient 8th Edition Little Test Bankjerrybriggs7d5t0v100% (27)

- Meningitis BakterialDocument10 pagesMeningitis BakterialVina HardiantiNo ratings yet

- Dyke Et Al-2013-Journal of Clinical PeriodontologyDocument7 pagesDyke Et Al-2013-Journal of Clinical PeriodontologyElena IancuNo ratings yet

- Odontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis - Need For Multidisciplinary Approach - A ReviewDocument6 pagesOdontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis - Need For Multidisciplinary Approach - A ReviewInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Specifications For Lime Slurry Injection For Ground ImprovementDocument5 pagesSpecifications For Lime Slurry Injection For Ground ImprovementSrini BaskaranNo ratings yet

- Devoir de Synthèse N°1 - Anglais - 2ème Lettres (2019-2020) Mme Rahmeni JamilaDocument5 pagesDevoir de Synthèse N°1 - Anglais - 2ème Lettres (2019-2020) Mme Rahmeni JamilaSassi LassaadNo ratings yet

- Electromagnetic Shielding Salvatore Celozzi Full ChapterDocument56 pagesElectromagnetic Shielding Salvatore Celozzi Full Chapternorma.catron566100% (10)

- House Beautiful 2010 Spring SummerDocument124 pagesHouse Beautiful 2010 Spring SummerAnnabel Lee100% (2)

- Flashcards 2601-2800Document191 pagesFlashcards 2601-2800kkenNo ratings yet

- ZTE UMTS NB-AMR Rate Control Feature GuideDocument63 pagesZTE UMTS NB-AMR Rate Control Feature GuideArturoNo ratings yet

- DoctrineDocument54 pagesDoctrinefredrick russelNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 10 Mathematics AcivitiesDocument20 pagesCBSE Class 10 Mathematics AcivitiesPrabina Sandra0% (1)

- PregnylDocument4 pagesPregnylAdina DraghiciNo ratings yet

- MICFL Annual Report 2017-18Document147 pagesMICFL Annual Report 2017-18Hasan Mohammad MahediNo ratings yet

- Astm D4Document3 pagesAstm D4Vijayan Munuswamy100% (1)

- English 8 Third Quarter Curriculum MapDocument5 pagesEnglish 8 Third Quarter Curriculum MapAgnes Gebone TaneoNo ratings yet

- Agile Certified Professional: Study Guide Take The Certification OnlineDocument25 pagesAgile Certified Professional: Study Guide Take The Certification OnlineqwertyNo ratings yet

- Declaration Form Autocop PDFDocument3 pagesDeclaration Form Autocop PDFAman DeepNo ratings yet

- Mobile Radio Propagation: Small-Scale Fading and MultipathDocument88 pagesMobile Radio Propagation: Small-Scale Fading and MultipathKhyati ZalawadiaNo ratings yet

- Rift Valley University: Department: - Weekend Computer ScienceDocument13 pagesRift Valley University: Department: - Weekend Computer ScienceAyele MitkuNo ratings yet

- Investment ProgrammingDocument14 pagesInvestment ProgrammingDILG NagaNo ratings yet

- Smith-Blair-Assessment-And-Management-Of-Neuropathic-Pain-In-Primary-Care 2Document51 pagesSmith-Blair-Assessment-And-Management-Of-Neuropathic-Pain-In-Primary-Care 2Inês Beatriz Clemente CasinhasNo ratings yet

- Appliacation LetterDocument7 pagesAppliacation LetterTriantoNo ratings yet

- UnivibeDocument1 pageUnivibePablo EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Mansi Mba Sip Report PDFDocument85 pagesMansi Mba Sip Report PDFAmul PatelNo ratings yet

- Reading Passage 1: (lấy cảm hứng) (sánh ngang)Document14 pagesReading Passage 1: (lấy cảm hứng) (sánh ngang)Tuấn Hiệp PhạmNo ratings yet

- Oana Adriana GICADocument42 pagesOana Adriana GICAPhilippe BrunoNo ratings yet

- Black White Sampling in Quantitative Research PresentationDocument12 pagesBlack White Sampling in Quantitative Research PresentationAnna Marie Estrella PonesNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan For TlsDocument7 pagesLesson Plan For TlsAini NordinNo ratings yet

- American Anthropologist - June 1964 - Pocock - Sociology A Guide To Problems and Literature T B BottomoreDocument2 pagesAmerican Anthropologist - June 1964 - Pocock - Sociology A Guide To Problems and Literature T B Bottomorek jNo ratings yet

- P To P CycleDocument5 pagesP To P CycleJaved AhmadNo ratings yet

- Article Reveiw FormatDocument18 pagesArticle Reveiw FormatSolomon FarisNo ratings yet

2014 Profilaxis Antibiotica en Endocarditis Infecciosa

2014 Profilaxis Antibiotica en Endocarditis Infecciosa

Uploaded by

Carlos AlfaroOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2014 Profilaxis Antibiotica en Endocarditis Infecciosa

2014 Profilaxis Antibiotica en Endocarditis Infecciosa

Uploaded by

Carlos AlfaroCopyright:

Available Formats

Costantinides

REVIEW ARTICLE

et al

Antibiotic Prophylaxis of Infective Endocarditis in

Dentistry: Clinical Approach and Controversies

Fulvia Costantinidesa/Emanuele Clozzab/Giulia Ottavianic/Margherita Gobboc/

Giancarlo Tirellid/Matteo Biasottoe

Purpose: Infective endocarditis (IE) in high-risk patients is a potentially severe complication which justifies the admin-

istration of antibiotics before invasive dental treatment. This literature review presents the current guidelines for anti-

biotic prophylaxis and discusses the controversial aspects related to the antibiotic administration for prevention of IE.

Results: According to the guidelines of the American Heart Association, individuals who are at risk to develop IE follow-

ing an invasive dental procedure still benefit from antibiotic prophylaxis. In contrast, the guidelines of the National In-

stitute for Health and Clinical Excellence in England and Wales have recommended that prophylactic antibiotic treat-

ment should no longer be performed in any at-risk patient. Bacteraemia following daily routines such as eating and

toothbrushing may be a greater risk factor for the development of IE than the transient bacteraemia that follows an

invasive dental procedure. However, a single administration of a penicillin derivate 30 to 60 minutes pre-operatively

still represents the main prophylactic strategy to prevent bacteraemia.

Conclusions: Presently, there is not enough evidence that supports and defines the administration of antibiotics to

prevent IE. The authors suggest performing a risk-benefit evaluation in light of the available guidelines before a deci-

sion is made about administration.

Key words: antibiotic prophylaxis, bacteraemia, current guidelines, endocarditis

Oral Health Prev Dent 2014;12:305-311 Submitted for publication: 03.12.12; accepted for publication: 11.04.13

doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a32133

It is currently estimated that more than 60% of all

bacterial infections in humans (and up to 80% of

chronic infections) are related to the microbial

sues caused by bacterial biofilms include the per-

sistence of infection and the resistance to

conventional antibiotic therapy and immune re-

growth in biofilms and to the host-response mech- sponses. Clinically, biofilms are considered a pri-

anism. To date, the most overwhelming evidence of mary cause of a majority of infections, such as oti-

the pathogenic relationship between humans and tis media, pneumonia in cystic fibrosis patients

biofilms is based on microscopy, revealing the pres- and endocarditis (Anderson et al, 2013).

ence of these communities at the site of infection Infective endocarditis (IE) is an infection of the

or in prosthetic implants recovered from patients endocardium induced most frequently by staphylo-

(Moscoso et al, 2009). cocci or streptococci that lead to general or sys-

The ability of bacteria to form biofilms is consid- temic symptoms of infection, embolic phenomena

ered a virulence factor; in fact, the most severe is- and endocardial vegetations. The pathogenesis of

IE is mainly attributed to the formation of septic

a

Assistant Professor, Dental Science School, University of Trieste, vegetations, which are fibrin-platelet complexes

Italy. embedded with bacteria on heart valves. The per-

b

Resident, Ashman Department of Periodontology and Implant sistent nature of biofilms can also induce inflam-

Dentistry, New York University College of Dentistry, NY, USA. mation and contribute directly to chronic bactere-

c

Postgraduate Fellow, Dental Science School, University of Trieste, mia and thromboembolic events, which are serious

Italy.

d

complications associated with IE (Jung et al, 2012).

Associate Professor and Director, Ear-Nose-Throat Division, Uni- The documented role of bacteria as the causal

versity of Trieste, Italy.

e agent of IE prompted a series of studies on the use

Researcher, Dental Science School, University of Trieste, Italy.

of antibiotic prophylaxis against bacteraemia. It is

Correspondence: Dr. Fulvia Costantinides, Dental Science School,

Piazza dell’Ospitale 1, 34100 Trieste, Italy. Tel: +39-040-399-2254, known that most of the procedures performed in

Fax: +39-040-399-2193. Email: f.costantinides@fmc.units.it the oral cavity (e.g. tooth extraction, apical surgery

Vol 12, No 4, 2014 305

Costantinides et al

and root scaling) cause bacteraemia, which may may heal by means of endothelialisation of vegeta-

subsequently lead to IE (Poveda-Roda et al, 2008). tions (Naber et al, 2004). The main complication of

The aim of this paper was to review the literature the proliferation of endocarditis is heart failure due

concerning the current guidelines for antibiotic to the direct effects of proliferating vegetations on

prophylaxis and to discuss the controversial as- the heart valves, which are eventually destroyed.

pects related to antibiotic administration for the Embolisms consisting of fragments of vegetations

prevention of IE in dental practice. can damage organs and tissues, including the

brain, lung, coronary arteries, spleen and the ex-

tremities of limbs. Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLINICAL PATTERN (SBE) is usually caused by different streptococci

OF INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS and less commonly by Staphyloccoccus aureus,

Staphylococcus epidermidis and Haemophilus influ-

Approximately 10,000 to 15,000 new cases of IE enzae (Oliver et al, 2008). Endocarditis on pros-

were diagnosed in the United States each year in thetic valves (EPV) occurs in 2% to 3% of patients

the early nineties (Bayer, 1993). However, IE is be- within 1 year after valve replacement and 0.5% per

coming more common in the U.S. than previously year thereafter. Right-Sided Endocarditis (RSE),

believed and is steadily increasing. In 2013, Bor et which involves the tricuspid valve and more rarely

al published a national study on IE epidemiology in the pulmonary valve and artery, may be induced by

the U.S. for the period 1998–2009. They found drug abuse or central venous-related infections.

that the number of unique endocarditis hospitalisa- Untreated IE is always fatal. The mortality rate

tions was 25,511 in 1998 (9.3 per 100,000 popu- varies greatly, depending on several factors: the

lation) rising to 38,976 in 2009 (12.7 per 100,000 age and general condition of the patient, duration

population). However, the precise incidence of IE is of infection before treatment, severity of pre-exist-

difficult to ascertain because case definitions have ing illnesses, site of infection, susceptibility of mi-

varied from decade to decade, among different au- croorganisms to antibiotics and the onset of com-

thors and between different medical centers plications. RSE often responds to antibiotics,

(Tleyjeh et al, 2007). For instance, in northeastern showing a better prognosis than left-sided endocar-

Italy, 1,863 subjects were hospitalised for IE be- ditis. The expected mortality for endocarditis from

tween 2000 and 2008, with a corresponding crude streptococci species – without major complications

rate of 4.4 per 100,000 person-years, increasing – is less than 10% when treated, but in practice,

from 4.1 in 2000–2002 to 4.9 in 2006–2008. A mortality can be 100% when endocarditis is caused

survey of IE in six regions in France in 1999 found by Aspergillus following valve replacement. Suc-

an incidence of 31 cases per 1,000,000 popula- cessful therapy requires the maintenance of an el-

tion (Hoen et al, 2002). evated level of antibiotic in serum and an effective

Sex and age also have an impact on the inci- surgical treatment to manage mechanical compli-

dence of IE. Men predominate in most case series, cations of resistant microorganisms (Mügge et al,

with male:female ratios ranging from 3:2 to 9:1 1989). Heart valve surgery (repair and/or valve re-

(Lerner and Weinstein, 1966; Watanakunakorn, placement) is often advisable to eradicate infec-

1977; Hill et al, 2007). More than half of all IE cas- tions that are untreatable with medications, espe-

es in the United States and Europe occur in pa- cially in cases of early introduction or IE in

tients over the age of 60, and the median age of prosthetic valves. Heart surgery performed to cor-

patients has increased steadily during the past 40 rect acute valvular insufficiency and to remove for-

years (Hill et al, 2007). eign bodies are associated with a significantly in-

IE usually affects the left side of the heart and creased survival rate (Werner et al, 2003).

the valves in descending order of frequency: mitral,

aortic, tricuspid and pulmonary. Important predis-

posing factors include: congenital heart disease CURRENT GUIDELINES FOR ANTIBIOTIC

and rheumatic valve disease, calcified or bicuspid PROPHYLAXIS IN DENTISTRY

aortic valves, mitral prolapse, hypertrophic subaor-

tic stenosis and prosthetic valves. Mural thrombus, It has been reported that the percentage of endo-

arteriovenous fistula, ventricular septal defect and carditis associated with dental procedures ranges

ductus arteriosus may provide further locations for from 4% to 14% of all cases (Ellervall et al, 2007).

infection. Those lesions treated with antibiotics There has been a well-established practice of ad-

306 Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry

Costantinides et al

ministering antibiotics to patients who are at risk of tional procedures if they bear structural cardiac de-

developing IE prior dental treatment. The rationale fects at risk of IE. The basis for this recommenda-

for this is that a high circulating dose of antibiotics tion is that: 1) there is no consistent association

may prevent the development of infected vegeta- between dental or non-dental interventional pro-

tion on damaged endocardium (Tomás Carmona et cedures and the development of IE; 2) regular

al, 2007). In vivo, prophylactic antibiotics are be- toothbrushing almost certainly produces a greater

lieved to act by interfering with three of the major risk of endocarditis than a single dental procedure;

stages in the pathogenesis of IE: bacteraemia (by 3) the clinical efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis is

reducing the number of microorganisms in blood), not proven and 4) antibiotic prophylaxis during den-

adherence (by decreasing the affinity of microor- tal procedures is not cost effective and increases

ganisms for heart valves) and multiplication of mi- the number of deaths due to anaphylaxis.

croorganisms on the heart valves (by interfering

with the metabolic activity of the microorganisms)

(Hall et al, 1993). DISCUSSION

Guidelines in many countries have recommend-

ed that before invasive dental procedures, antibiot- Three main guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis pro-

ics should be administered to people at high risk of moted by the AHA, BSAT and NICE are currently

IE. According to the guidelines from the American available. According to the guidelines from the

Heart Association (AHA), subjects with prosthetic American Heart Association and from the British

cardiac valves, previous IE, unrepaired cyanotic Society for Antimicrobial Therapy, people who are

congenital heart disease (CHD), completely re- at risk of developing IE after an invasive dental pro-

paired congenital heart defect with prosthetic ma- cedure benefit from antibiotic prophylaxis. A single

terial or device during the first six months after the administration of a penicillin derivate 30 to 60 min-

procedure, repaired CHD with residual defects at utes before the procedure remains the main pro-

the site or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic patch phylactic strategy to prevent bacteraemia.

or prosthetic device, and cardiac transplantation However, it has been demonstrated that the

recipients who develop cardiac valvulopathy are at presence of antibiotics such as penicillin did not

risk of developing IE when they undergo an invasive prevent bacterial biofilm formation in vitro in the

dental procedure (Gould et al, 2006; Wilson et al, presence of plasma components and platelets.

2007). The AHA withdrew the advice to cover gas- Moreover, prophylaxis with penicillin or other antibi-

trointestinal and urogenital interventions, but iden- otics failed to prevent colonisation or biofilm forma-

tified the manipulation of gingival tissue or the tion in situ when tested in a rat model of endocar-

periapical region of teeth or perforation of the oral ditis with predamaged valves (Jung et al, 2012). In

mucosa as invasive dental procedures, which com- vivo, the evidence for bacteraemia reduction or pre-

monly occur in oral surgery. vention by antibiotic prophylaxis is also unclear. In

For high-risk patients, prophylaxis is still recom- a study by Hall et al (1996), the incidence of bacte-

mended for all dental procedures that in general raemia with viridans streptococci was 79% in pa-

involve the manipulation of teeth and gingival tis- tients treated with Cefaclor and 50% in a placebo

sues or endodontics. When possible, a pre-opera- group during tooth extraction. No difference in the

tive mouthwash with 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate incidence or magnitude of bacteraemia was ob-

should be administered. served when the two patient groups were com-

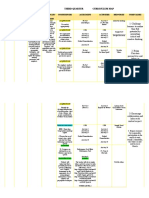

In Tables 1 and 2, guidelines for IE prophylaxis in pared (Hall et al, 1996). Even studies which show

children and adults according to the AHA and to the reduction in bacteraemia do not show reduction in

British Society for Antimicrobial Therapy (BSAT) are IE (Shanson et al, 1985; Roberts et al, 1987). Also,

shown (Gould et al, 2006; Wilson et al, 2007). A bacterial resistance to antibiotics could be involved

recent guideline provided by the National Institute in the inefficacy of the prophylaxis. Recently, a re-

for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in England duced susceptibility of oral streptococci to penicil-

and Wales has recommended that prophylactic an- lin was recorded in 13.4% of cases (Pasquantonio

tibiotic treatment should not be used for any at-risk et al, 2012).

patient undergoing a dental procedure (Stokes et The NICE in England and Wales recommended

al, 2008). In summary, the guideline recommends that prophylactic antibiotic treatment should no

that prophylaxis should not be given to adults or longer be used for any at-risk patient, considering

children undergoing dental or non-dental interven- that it was demonstrated that regular toothbrushing

Vol 12, No 4, 2014 307

Costantinides et al

Table 1 Recommended IE prophylaxis during interventions in the oral cavity in children

American Heart Association Guidelines (2007) British Society for Antimicrobial Therapy Guidelines (2006)

Regimen: single dose 30

Situation Agent to 60 min before procedure Agent Regimen

750 mg (< 5 years of age)

50 mg / kg 1.5 g (5 to 10 years of age)

Oral Amoxicillin Amoxicillin

3 g (> 10 years of age)

1 h before procedure

250 mg (< 5 years of age)

Unable to Ampicillin, Cefa- 500 mg (5 to 10 years of age)

50 mg / kg IM or IV

take oral zolin or Amoxicillin 1 g (> 10 years of age)

medication Ceftriaxone IV just before procedure or at induction of

anaesthesia

Cephalexin * § 50 mg / kg

150 mg (< 5 years of age)

Allergic to Clindamycin 20 mg / kg 300 mg (5 to 10 years of age)

Clindamycin

penicillin 600 mg (> 10 years of age)

Azithromycin or 1 h before procedure

15 mg / kg

Clarithromycin

75 mg (< 5 years of age)

Cefazolin§ or 150 mg (5 to 10 years of age)

Allergic to 50 mg / kg IM or IV Clindamycin

Ceftriaxone 300 mg (> 10 years of age)

penicillin or IV given over at least 10 min

ampicillin and

unable to 200 mg (< 5 years of age)

take oral 300 mg (5 to 10 years of age)

medication Clindamycin 20 mg / kg IM or IV Azithromycin 500 mg (> 10 years of age)

Oral suspension for patients that cannot

swallow capsules 1 h before procedure

* or other first- or second-generation oral cephalosporin in equivalent adult or paediatric dosage. §Cephalosporins should not be used in pa-

tients with immediate hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin (urticaria, angioedema or anaphylaxis).

Table 2 Recommended IE prophylaxis during interventions in the oral cavity in adults

American Heart Association Guidelines (2007) British Society for Antimicrobial Therapy Guidelines (2006)

Regimen: single dose 30

Situation Agent to 60 min before procedure Agent Regimen

Oral Amoxicillin 2g Amoxicillin 3 g 1 h before procedure

Unable to Ampicillin 2 g IM or IV

1 g IV just before procedure or at

take oral Cefazolin or Amoxicillin

1 g IM or IV induction of anaesthesia

medication Ceftriaxone

Cephalexin * § 2g

Allergic to Clindamycin 600 mg

Clindamycin 600 mg 1 h before procedure

penicillin

Azithromycin or

500 mg

Clarithromycin

Allergic to Cefazolin§ or

1 g IM or IV Clindamycin 300 mg IV given over at least 10 min

penicillin or Ceftriaxone

ampicillin and

unable to 500 mg oral suspension for patients that

take oral Clindamycin 600 mg IM or IV Azithromycin cannot swallow capsules 1 h before

medication procedure

* or other first- or second-generation oral cephalosporin in equivalent adult or paediatric dosage. § Cephalosporins should not be used in pa-

tients with immediate hypersensitivity reaction to penicillin (urticaria, angioedema or anaphylaxis).

308 Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry

Costantinides et al

and other everyday activities almost certainly pre- of penicillins in significantly reducing the number

sent a far greater risk of IE than a single dental pro- of subjects developing bacteraemia (Tomás et al,

cedure because of repeated exposure to bacterae- 2008). It should be borne in mind that since IE is

mia with oral flora (Delahaye et al, 2004). Recently, a life-threatening condition, the absence of evi-

Tomás et al (2012) published a systematic review on dence of benefit from prophylaxis is not the same

periodontal health status and bacteraemia from dai- as evidence of its absence (Mohindra, 2009). A

ly oral activities. Results showed that toothbrushing recent study attempted to quantify modification in

is the activity for which there is greatest evidence of prescription of prophylactic antibiotics before inva-

an influence of the prevalence of bacteraemia de- sive dental procedures for patients at risk of IE

pending on the state of oral hygiene, gingival or per- and any concurrent variation in the incidence of IE

iodontal status (Tomás et al, 2012). Thus, attention subsequent to the introduction of the NICE clinical

was shifted from procedure-related bacteraemia to guideline (in March 2008) recommending the ces-

cumulative bacteraemia. It is postulated that daily sation of antibiotic prophylaxis in the United King-

bacteraemia is six million times greater than bacte- dom (Thornhill et al, 2011). Those authors found

raemia after a single extraction (Roberts, 1999). that after the introduction of the guideline, a large

Furthermore, evidence is lacking that bacterae- (78.6%) and rapid decrease occurred in prescrib-

mia occurring during dental treatment significantly ing antibiotic prophylaxis. However, no significant

increases the risk of endocarditis. A Cochrane re- increase in the number of IE cases above the long-

view by Oliver et al (2008) did not find any evidence term baseline trend over this period was detected.

of a benefit from prophylactic administration of Neither was there a significant increase in the rate

penicillin in prevention of IE during invasive dental of IE-related deaths in hospitals nor a significant

procedures (Seymour et al, 2000; Naber et al, increase in the number of cases due to strepto-

2004). cocci of possible oral origin. The authors stressed

A recent report by the Working Party of the BSAT the fact that frequent episodes of bacteraemia fol-

stated that probably the most important factor in lowing daily routines such as eating and tooth-

reducing the risk of IE in susceptible individuals is brushing may be a greater risk factor for the devel-

good oral hygiene and, for this reason, the preven- opment of IE than the transient bacteraemia that

tive approach should facilitate access to high-qual- follows an invasive dental procedure. However,

ity dental care (Gould et al, 2006). they could not exclude the possibility that residual

Another reason for recommending restricting an- antibiotic prophylaxis could be indicated for a sub-

tibiotic prophylaxis regards antibiotic-related ad- set of patients with highest risk of IE, particularly

verse effects, e.g. anaphylaxis. Although the AHA, those with prosthetic heart valves or a history of IE

BSAT and NICE specifically discuss anaphylaxis, that might still benefit from antibiotic prophylaxis.

Gopalakrishnan et al (2010) reported that the To more directly answer this question, they sug-

guidelines place various emphasis on this point. gested that a carefully designed, randomised, pla-

Anaphylactic reactions are very rare and both AHA cebo-controlled trial of antibiotic prophylaxis in

and NICE recognise this fact. At the same time, the these patients would be required.

guidelines also acknowledge that there is a lack of Thus, there is still no solid evidence about

evidence demonstrating a clear benefit from antibi- whether prophylaxis is effective or ineffective

otic prophylaxis. Nevertheless, Gopalakrishnan et against IE in people at risk who are about to un-

al (2010) underline that based on the lack of clear dergo an invasive dental procedure. Moreover, few

benefit, even theoretical or rare risks like anaphy- randomised controlled trials, controlled clinical tri-

lactic reactions have to be factored in when making als or cohort studies were available to demonstrate

public health recommendations affecting large pa- a real benefit and, as reported by Bach (2010–

tient populations (as anaphylactic reactions could 2011), the arguments for and against prophylaxis

be fatal), as was discussed in the NICE guidance. must also take into consideration that the practical

The NICE recommendations are not currently guidelines should be compatible with ethical care.

universally accepted. Some cardiologists, cardiac

surgeons and oral surgeons still employ prophylac-

tic antibiotics in IE-risk patients, especially consid- CONCLUSIONS

ering that in the majority of the studies published

on antibiotic prophylaxis and post-dental extrac- The main concern for patients is the dualism be-

tion bacteraemia, the authors confirm the efficacy tween the status quo and the new guidelines, which

Vol 12, No 4, 2014 309

Costantinides et al

is likely to perturb many dental practitioners. Re- 12. Hill EE, Herijgers P, Claus P, Vanderschueren S, Herregods

MC, Peetermans WE. Infective endocarditis: changing epi-

fusal to change practice – derived from the highest demiology and predictors of 6-month mortality: a prospec-

professional choice of best care for individual pa- tive cohort study. Eur Heart J 2007;28:196–203.

tients – should be respected. Presently, there is 13. Hoen B, Alla F, Selton-Suty C, Béguinot I, Bouvet A, Brian-

not enough evidence that supports and defines the çon S, Casalta JP, Danchin N, Delahaye F, Etienne J, Le

Moing V, Leport C, Mainardi JL, Ruimy R, Vandenesch F.

administration of antibiotics to prevent IE. Thus, Association pour l‘Etude et la Prévention de l‘Endocardite

the decision on whether to prescribe antibiotic Infectieuse (AEPEI) Study Group. Changing profile of infec-

prophylaxis is based on a risk assessment consid- tive endocarditis: results of a 1-year survey in France.

JAMA 2002;288:75–81.

ering that the factors involved in the risk-benefit

14. Jung CJ, Yeh CY, Shun CT, Hsu RB, Cheng HW, Lin CS, Chia

evaluation may be approached differently by differ- JS. Platelets enhance biofilm formation and resistance of

ent experts. Where national guidelines for antibiot- endocarditis-inducing streptococci on the injured heart

ic prophylaxis exist, the dentist must follow these, valve. J Infect Dis 2012;205:1066–1075.

but ethically, practitioners need to carefully discuss 15. Lerner PI, Weinstein L. Infective endocarditis in the antibi-

otic era. N Engl J Med 1966;274:199–206.

the potential benefit and harm of antibiotic cover-

16. Mohindra RK. NICE, drug eluting stents and the limits of

age with their patients. trial data. Heart 2009;95:505–506.

17. Moscoso M, García E, López R. Pneumococcal biofilms.

Int Microbiol 2009;12:77–85.

REFERENCES 18. Mügge A, Daniel WG, Frank G, Lichtlen PR. Echocardiogra-

phy in infective endocarditis: reassessment of prognostic

1. Anderson MJ, Parks PJ, Peterson ML. A mucosal model to implications of vegetation size determined by the tran-

study microbial biofilm development and anti-biofilm thera- sthoracic and the transesophageal approach. J Am Coll

peutics. J Microbiol Methods 2013;92:201–208. Cardiol 1989;14:631–638.

2. Bach DS. Antibiotic prophylaxis for infective endocarditis: 19. Naber CK. Paul-Ehrlich-Gesellschaft für Chemotherapie;

ethical care in the era of revised guidelines. Methodist Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kardiologie, Herz- und Kreis-

Debakey Cardiovasc J 2010–2011;6:48–52. laufforschung; Deutschen Gesellschaft für Thorax-, Herz-

3. Bayer AS. Infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 1993;17: und Gefässchirurgie; Deutschen Gesellschaft für Infekti-

313–320. ologie; Deutschen Gesellschaft für Internistische

Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin; Deutschen Gesells-

4. Bor DH, Woolhandler s, Nardin R, Brusch J, Himmelstein chaft für Hygiene und Mikrobiologie. S2 Guideline for diag-

DU. Infective endocarditis in the U.S., 1998–2009: a na- nosis and therapy of infectious endocarditis [in German].

tionwide study. PLoS One 2013;8(3): e60033. Z Kardiol 2004;93:1005–1021.

5. Delahaye F, Celard M, Roth O, De Gevigney G. Indications 20. Oliver R, Roberts GJ, Hopper L. Worthington H. Antibiotics

and optimal timing for surgery in infective endocarditis. for the prophylaxis of bacterial endocarditis in dentistry.

Heart 2004;90:618–620. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;4:CD003813.

6. Ellervall E, Vinge E, Rohlin M, Knutsson K. Antibiotic 21. Pasquantonio G, Condò S, Cerroni L, Bikiqu L, Nicoletti M,

prophylaxis in oral healthcare – the agreement between Prenna M, Ripa S.Antibacterial activity of various antibiot-

Swedish recommendations and evidence. Br Dent J ics against oral streptococci isolated in the oral cavity. Int

2010;208:E5. J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2012 ;25:805–809.

7. Fedeli U, Schievano E, Buonfrate D, Pellizzer G, Spolaore 22. Poveda-Roda R, Jiménez Y, Carbonell E, Gavaldá C, Mar-

P. Increasing incidence and mortality of infective endocar- gaix-Muñoz MM, Sarrión-Pérez G. Bacteremia originating

ditis: a population-based study through a record-linkage in the oral cavity. A review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal

system. BMC Infect Dis 2011;11:48. 2008;13:E355–362.

8. Gopalakrishnan PP, Shukla SK, Tak T. Antibiotic prophy- 23. Roberts GJ, Radford P, Holt R. Prophylaxis of dental bacte-

laxis and anaphylaxis. Clin Med Res 2010;8:80–81. raemia with oral amoxycillin in children. Br Dent J 1987;162:

9. Gould FK, Elliott TS, Foweraker J, Fulford M, Perry JD, Rob- 179–182.

erts GJ, Sandoe JA, Watkin RW, Working Party of the Brit- 24. Roberts GJ. Dentists are innocent! “Everyday” bacteremia

ish Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Guidelines for is the real culprit: a review and assessment of the evi-

the prevention of endocarditis: report of the Working Party dence that dental surgical procedures are a principal

of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J cause of bacterial endocarditis in children. Pediatr Cardiol

Antimicrob Chemother 2006;57:1035–1042. 1999;20:317–325.

10. Hall G, Hedström SA, Heimdahl A, Nord CE. Prophylactic 25. Seymour RA, Lowry R, Whitworth JM, Martin MV. Infective

administration of penicillins for endocarditis does not re- endocarditis, dentistry and antibiotic prophylaxis; time for

duce the incidence of postextraction bacteremia. Clin In- a rethink? Br Dent J 2000;189:610–616.

fect Dis 1993;17:188–194.

26. Shanson DC, Akash S, Harris M, Tadayon M. Erythromycin

11. Hall G, Heimdahl A, Nord CE. Effects of prophylactic ad- stearate, 1.5 g, for the oral prophylaxis of streptococcal

ministration of cefaclor on transient bacteremia after den- bacteraemia in patients undergoing dental extraction: ef-

tal extraction. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1996;15: ficacy and tolerance. J Antimicrob Chemother 1985;15:

646–649. 83–90.

27. Stokes T, Richey R, Wray D. Guideline Development Group.

Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis: summary of

NICE guidance. Heart 2008;94:930–931.

310 Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry

Costantinides et al

28. Thornhill MH, Dayer MJ, Forde JM, Corey GR, Chu VH, 32. Tomás I, Limeres J, Diz P. Confirm the efficacy. Br Dent J

Couper DJ, Lockhart PB. Impact of the NICE guideline rec- 2008;205:3.

ommending cessation of antibiotic prophylaxis for preven- 33. Watanakunakorn C. Changing epidemiology and newer as-

tion of infective endocarditis: before and after study. BMJ pects of infective endocarditis. Adv Intern Med

2011;342:d2392. 1977;22:21–47.

29. Tleyjeh IM, Abdel-Latif A, Rahbi H, Scott CG, Bailey KR, 34. Werner M, Andersson R, Olaison L, Hogevik H. A clinical

Steckelberg JM, Wilson WR, Baddour LM. A systematic study of culture-negative endocarditis. Medicine (Balti-

review of population-based studies of infective endocardi- more) 2003;82:263–273.

tis. Chest 2007;132:1025–1035.

35. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, Baddour

30. Tomás Carmona I, Diz Dios P, Scully C. Efficacy of antibiotic LM, Levison M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis:

prophylactic regimens for the prevention of bacterial endo- guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guide-

carditis of oral origin. J Dent Res 2007;86:1142–1159. line from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fe-

31. Tomás I, Diz P, Tobías A, Scully C, Donos N. Periodontal ver, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee,

health status and bacteraemia from daily oral activities: Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the

systematic review/meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular

2012;39:213–228. Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Out-

comes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circula-

tion 2007;116:1736–1754.

Vol 12, No 4, 2014 311

Copyright of Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry is the property of Quintessence Publishing

Company Inc. and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a

listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print,

download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Glock Armorer's Manual Gen 1-5 2018Document140 pagesGlock Armorer's Manual Gen 1-5 2018Rachel Symes100% (3)

- BIO102 Practice ExamDocument10 pagesBIO102 Practice ExamKathy YuNo ratings yet

- Infective Endocarditis and Dental Procedures: Evidence, Pathogenesis, and PreventionDocument10 pagesInfective Endocarditis and Dental Procedures: Evidence, Pathogenesis, and PreventionSarah Ariefah SantriNo ratings yet

- Beatriz 2016 - Bacteremia Và Phẫu Thuật MiệngDocument30 pagesBeatriz 2016 - Bacteremia Và Phẫu Thuật MiệngPhong TruongNo ratings yet

- Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis: Sadewantoro, DR, SP - JPDocument25 pagesSubacute Bacterial Endocarditis: Sadewantoro, DR, SP - JPfelicedaNo ratings yet

- Infective Endocarditis Today (Version 1 Peer Review: 1 Not Approved)Document9 pagesInfective Endocarditis Today (Version 1 Peer Review: 1 Not Approved)preetNo ratings yet

- Jamacardiology Sperotto 2024 Oi 240019 1712241905.81501Document12 pagesJamacardiology Sperotto 2024 Oi 240019 1712241905.81501lakshminivas PingaliNo ratings yet

- Otitis ExternaDocument4 pagesOtitis ExternaCesar Mauricio Daza CajasNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical Cases and ReportsDocument4 pagesJournal of Clinical Cases and ReportsDonny RamadhanNo ratings yet

- The Risk For Endocarditis in Dental PracticeDocument9 pagesThe Risk For Endocarditis in Dental PracticeisanreryNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Dentoalveolar Surgery: Michael G. Savage, DDSDocument10 pagesAntibiotic Prophylaxis in Dentoalveolar Surgery: Michael G. Savage, DDSCriissthiiann HernnandezNo ratings yet

- OM Stafilococo (Clase Observacionales)Document7 pagesOM Stafilococo (Clase Observacionales)Jairo Camilo Guevara FaríasNo ratings yet

- antbioDocument16 pagesantbioefonseca2No ratings yet

- Fimmu 13 915081Document15 pagesFimmu 13 915081Zakia MaharaniNo ratings yet

- Antibiotics in Endodontics: A ReviewDocument16 pagesAntibiotics in Endodontics: A ReviewHisham HameedNo ratings yet

- ADJ-odontogenic InfectionDocument9 pagesADJ-odontogenic Infectiondr.chidambra.kapoorNo ratings yet

- 5fa2d32c9e2ea IJAR-33917Document9 pages5fa2d32c9e2ea IJAR-33917Sharanya BoseNo ratings yet

- Research and Reviews: Journal of Dental SciencesDocument7 pagesResearch and Reviews: Journal of Dental SciencesParastikaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2667147621000510 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S2667147621000510 MainDiahNo ratings yet

- Joint InfectionsDocument10 pagesJoint InfectionsJPNo ratings yet

- 325 FullDocument20 pages325 FullDessyadoeNo ratings yet

- Acute Mastoiditis in Children: Pasquale Cassano, Giorgio Ciprandi, Desiderio PassaliDocument6 pagesAcute Mastoiditis in Children: Pasquale Cassano, Giorgio Ciprandi, Desiderio PassaliSyafira AlimNo ratings yet

- Head and Neck AbsesDocument8 pagesHead and Neck AbsesNandaNo ratings yet

- Jced 9 E319Document6 pagesJced 9 E319sorayahyuraNo ratings yet

- Peacock Et Al-2016-Oral DiseasesDocument23 pagesPeacock Et Al-2016-Oral DiseasesGgg2046No ratings yet

- Reaching A BetterDocument6 pagesReaching A BetterAdyas AdrianaNo ratings yet

- Orthodontic Care For Medically Compromised Patients: ReviewDocument12 pagesOrthodontic Care For Medically Compromised Patients: ReviewAkram AlsharaeeNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Disease and The Role of Oral BacteriaDocument14 pagesCardiovascular Disease and The Role of Oral BacteriaOdonto BrunaNo ratings yet

- A Literature Review On Periodontitis and SystemicDocument3 pagesA Literature Review On Periodontitis and SystemicAfolabi Horlarmilekan AbdulbasitNo ratings yet

- Perio MedicineDocument90 pagesPerio MedicineAnsh Veer ChouhanNo ratings yet

- PIIS1201971214016713Document9 pagesPIIS1201971214016713Serque777No ratings yet

- 3.casual or Causal Relationship Between Periodontal Infection and Non Oral DiseaseDocument3 pages3.casual or Causal Relationship Between Periodontal Infection and Non Oral DiseaseEstherNo ratings yet

- Articulo ImportanteDocument8 pagesArticulo ImportanteTed SilvaNo ratings yet

- Nihms976360 PDFDocument17 pagesNihms976360 PDFyenny handayani sihiteNo ratings yet

- 6 SaDocument9 pages6 SaRizqi AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Cirugia OdDocument7 pagesCirugia OdDaniela Faundez VilugronNo ratings yet

- Interactions Between Neutrophils and Periodontal Pathogens in Late-Onset PeriodontitisDocument11 pagesInteractions Between Neutrophils and Periodontal Pathogens in Late-Onset PeriodontitisAdriana NoelNo ratings yet

- Systemic Diseases Caused by Oral InfectionDocument12 pagesSystemic Diseases Caused by Oral InfectionaninuraniyahNo ratings yet

- Periodontal Disease and Its Prevention, by Traditional and New Avenues (Review)Document3 pagesPeriodontal Disease and Its Prevention, by Traditional and New Avenues (Review)Louis Hutahaean100% (1)

- CO - Endocarditis in Critically Ill PatientsDocument8 pagesCO - Endocarditis in Critically Ill PatientsRomán Wagner Thomas Esteli ChávezNo ratings yet

- Antibiotics 10 01298 v3Document15 pagesAntibiotics 10 01298 v3Daniel AtiehNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Dentoalveolar SurgeryDocument10 pagesAntibiotic Prophylaxis in Dentoalveolar SurgeryDario Fernando HernandezNo ratings yet

- Infective EndocarditisDocument7 pagesInfective EndocarditisDwi Permana PutraNo ratings yet

- Posición Ante Los Antibióticos 2016Document40 pagesPosición Ante Los Antibióticos 2016Sydney LópezNo ratings yet

- Infective EndocarditisDocument16 pagesInfective EndocarditisAnnisa UlfaNo ratings yet

- Odontogenic Necrotizing Fasciitis: A Systematic Review of The LiteratureDocument7 pagesOdontogenic Necrotizing Fasciitis: A Systematic Review of The LiteratureDenta HaritsaNo ratings yet

- SJAMS 66 2563 2566 C PDFDocument4 pagesSJAMS 66 2563 2566 C PDFVitta Kusma WijayaNo ratings yet

- Case Study MHPTDocument10 pagesCase Study MHPTHalfIeyzNo ratings yet

- Fungal Endocarditis Current ChallengesDocument5 pagesFungal Endocarditis Current ChallengesmarnixvonkempNo ratings yet

- Fungi PDFDocument6 pagesFungi PDFnilnaNo ratings yet

- Periodontitis, Bacteremia and Infective Endocarditis: A Review StudyDocument8 pagesPeriodontitis, Bacteremia and Infective Endocarditis: A Review StudyAndra AgheorghieseiNo ratings yet

- Pubmed EndokarditisDocument7 pagesPubmed EndokarditisNayaka AriyaNo ratings yet

- Trop Med 140515Document10 pagesTrop Med 140515Arfa AlyaNo ratings yet

- WF10 (Immunokine) On Diabetic Foot UlcerDocument6 pagesWF10 (Immunokine) On Diabetic Foot UlcerRonal PerinoNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Little and Falaces Dental Management of The Medically Compromised Patient 8th Edition Little Test Bank PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full Little and Falaces Dental Management of The Medically Compromised Patient 8th Edition Little Test Bank PDFdanagarzad90y100% (13)

- Staphylococcus Epidermidis: Bio®lms: Importance and ImplicationsDocument6 pagesStaphylococcus Epidermidis: Bio®lms: Importance and Implicationsferro indahNo ratings yet

- Severe Intracranial and Extracranial Complications of The Middle Ear Cholesteatoma A Report CaseDocument5 pagesSevere Intracranial and Extracranial Complications of The Middle Ear Cholesteatoma A Report CaseChoirul UmamNo ratings yet

- Little and Falaces Dental Management of The Medically Compromised Patient 8th Edition Little Test BankDocument36 pagesLittle and Falaces Dental Management of The Medically Compromised Patient 8th Edition Little Test Bankjerrybriggs7d5t0v100% (27)

- Meningitis BakterialDocument10 pagesMeningitis BakterialVina HardiantiNo ratings yet

- Dyke Et Al-2013-Journal of Clinical PeriodontologyDocument7 pagesDyke Et Al-2013-Journal of Clinical PeriodontologyElena IancuNo ratings yet

- Odontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis - Need For Multidisciplinary Approach - A ReviewDocument6 pagesOdontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis - Need For Multidisciplinary Approach - A ReviewInternational Organization of Scientific Research (IOSR)No ratings yet

- Specifications For Lime Slurry Injection For Ground ImprovementDocument5 pagesSpecifications For Lime Slurry Injection For Ground ImprovementSrini BaskaranNo ratings yet

- Devoir de Synthèse N°1 - Anglais - 2ème Lettres (2019-2020) Mme Rahmeni JamilaDocument5 pagesDevoir de Synthèse N°1 - Anglais - 2ème Lettres (2019-2020) Mme Rahmeni JamilaSassi LassaadNo ratings yet

- Electromagnetic Shielding Salvatore Celozzi Full ChapterDocument56 pagesElectromagnetic Shielding Salvatore Celozzi Full Chapternorma.catron566100% (10)

- House Beautiful 2010 Spring SummerDocument124 pagesHouse Beautiful 2010 Spring SummerAnnabel Lee100% (2)

- Flashcards 2601-2800Document191 pagesFlashcards 2601-2800kkenNo ratings yet

- ZTE UMTS NB-AMR Rate Control Feature GuideDocument63 pagesZTE UMTS NB-AMR Rate Control Feature GuideArturoNo ratings yet

- DoctrineDocument54 pagesDoctrinefredrick russelNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 10 Mathematics AcivitiesDocument20 pagesCBSE Class 10 Mathematics AcivitiesPrabina Sandra0% (1)

- PregnylDocument4 pagesPregnylAdina DraghiciNo ratings yet

- MICFL Annual Report 2017-18Document147 pagesMICFL Annual Report 2017-18Hasan Mohammad MahediNo ratings yet

- Astm D4Document3 pagesAstm D4Vijayan Munuswamy100% (1)

- English 8 Third Quarter Curriculum MapDocument5 pagesEnglish 8 Third Quarter Curriculum MapAgnes Gebone TaneoNo ratings yet

- Agile Certified Professional: Study Guide Take The Certification OnlineDocument25 pagesAgile Certified Professional: Study Guide Take The Certification OnlineqwertyNo ratings yet

- Declaration Form Autocop PDFDocument3 pagesDeclaration Form Autocop PDFAman DeepNo ratings yet

- Mobile Radio Propagation: Small-Scale Fading and MultipathDocument88 pagesMobile Radio Propagation: Small-Scale Fading and MultipathKhyati ZalawadiaNo ratings yet

- Rift Valley University: Department: - Weekend Computer ScienceDocument13 pagesRift Valley University: Department: - Weekend Computer ScienceAyele MitkuNo ratings yet

- Investment ProgrammingDocument14 pagesInvestment ProgrammingDILG NagaNo ratings yet

- Smith-Blair-Assessment-And-Management-Of-Neuropathic-Pain-In-Primary-Care 2Document51 pagesSmith-Blair-Assessment-And-Management-Of-Neuropathic-Pain-In-Primary-Care 2Inês Beatriz Clemente CasinhasNo ratings yet

- Appliacation LetterDocument7 pagesAppliacation LetterTriantoNo ratings yet

- UnivibeDocument1 pageUnivibePablo EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Mansi Mba Sip Report PDFDocument85 pagesMansi Mba Sip Report PDFAmul PatelNo ratings yet

- Reading Passage 1: (lấy cảm hứng) (sánh ngang)Document14 pagesReading Passage 1: (lấy cảm hứng) (sánh ngang)Tuấn Hiệp PhạmNo ratings yet

- Oana Adriana GICADocument42 pagesOana Adriana GICAPhilippe BrunoNo ratings yet

- Black White Sampling in Quantitative Research PresentationDocument12 pagesBlack White Sampling in Quantitative Research PresentationAnna Marie Estrella PonesNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan For TlsDocument7 pagesLesson Plan For TlsAini NordinNo ratings yet

- American Anthropologist - June 1964 - Pocock - Sociology A Guide To Problems and Literature T B BottomoreDocument2 pagesAmerican Anthropologist - June 1964 - Pocock - Sociology A Guide To Problems and Literature T B Bottomorek jNo ratings yet

- P To P CycleDocument5 pagesP To P CycleJaved AhmadNo ratings yet

- Article Reveiw FormatDocument18 pagesArticle Reveiw FormatSolomon FarisNo ratings yet