Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Giorgio Ghelfi - Full Paper

Giorgio Ghelfi - Full Paper

Uploaded by

Giorgio GhelfiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Giorgio Ghelfi - Full Paper

Giorgio Ghelfi - Full Paper

Uploaded by

Giorgio GhelfiCopyright:

Available Formats

Doi: https://doi.org/10.4995/HERITAGE2022.2022.

****

The parish church of San Michele Arcangelo in Metelliano: the path of

knowledge of a vernacular architecture

Author 11

University of Florence, Department of Architecture, giorgio.ghelfi@unifi.it

Topic: Topic 1. Vernacular architecture: matter, culture and sustainability

T1.3. Studies of traditional techniques and materials

Abstract

The parish church of San Michele a Metelliano, located in Tuscany near the city of Arezzo, is a unique case

of vernacular architecture. The building is the result of a synthesis of traditional local architecture and a

strong Byzantine influence. It became a national monument in 1907.

Keywords: traditional architecture, restoration, conservation, heritage, traditional techniques

1. Introduction times. 2 It is a well-known fact that in Tuscany,

more than in any other region, the 9th century saw

Research on parish churches in Tuscany has been

a radical renewal in the construction of places of

ongoing for over a century. 1 The numerous stud-

worship, which was driven by the strong increase

ies that have been conducted are justified by the

in productivity. In Arezzo, the situation was no

important role these places of worship have

different; in fact, numerous places of worship

played throughout the ages. For centuries, parish

were built, both minor, located mainly in rural ar-

churches have not only collected the material and

eas, and major, for example, the so-called Duomo

immaterial records of their surroundings, but

Vecchio di Arezzo. 3

they themselves are, for the traditional building

techniques and local materials employed, im- This building, erected on the Pionta hill, was de-

portant testaments. Although the construction of molished by Cosimo I in 1561 for military pur-

holy places rose in the first centuries of the sec- poses. 4 The only information available today is

ond millennium, many of today’s parish churches comprised of episodic notes from recognised

are the result of stratifications that date back to sources. 5

early Christian and, in some cases, Roman

1 2 Angelo Tafi in Le antiche pievi. Madri vegliarde del popolo

For further information on the subject, see the various stud-

ies conducted, including the following cfr.: Bracco M. (1971) aretino explains the mixture of peoples and events that led to

Architettura e scultura romanica in Casentino, Firenze; the formation of the pievi in the ancient context of Arezzo by

Canestrelle A. (1904). L’Architettura medievale a Siena e using a time scale.

nell’antico territorio, Siena; Moretti I., Stopani R. (1968). 3 For a more detailed discussion of the subject, see Guglielmo

Chiese Romaniche in Valdelsa, Firenze; Salmi M. (1912).

De Angelis d’Ossat in Atti e Memorie della Accademia Pet-

Chiese romaniche in Casentino e in Valdarno superiore, in

rarca di Arezzo N.S. XXXVII, p. XXVI, (citated in De An-

“L’Arte”; (1927). L’architettura romanica in Toscana, Mi-

gelis d’Ossat G. (1978). Il “Duomo Vecchio” di Arezzo, Pal-

lano-Roma; (1972). Chiese romaniche in Val di Pesa, Fi-

ladio, p.38)

renze; (1985). Chiese romaniche della campagna toscana,

Milano; Salvini R., Von Borsig A. (1973). Toskana. Un- 4

De Angelis d’Ossat G. (1978). Il “Duomo Vecchio” di

bekannte romanische Kirchen, Monaco; (1974). Architettura Arezzo, cit. p.7

romanica religiosa nel contado fiorentino, Firenze; (1981).

Romanico Senese, Firenze;

5

Pasqui U. (1899). Documenti per la storia della città di

Arezzo nel Medio Evo, Voll. I-IV

2022, Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València

The parish church of San Michele Arcangelo in Metelliano: the path of knowledge of a vernacular architecture

architect not only in the construction of the

Duomo Vecchio di Arezzo but also in his later

works.

Fig. 1 Territorial outline of the parish church of San Michele

a Metelliano.

For the renovation of the episcopal complex in

Arezzo, initiated by Bishop Elimperto (986-

1010), Maginardo, the architect who would sub-

sequently be known as Maginardo Aretino, was Fig. 2. In Morelli E. (2007). Strade e paesaggi della Tos-

commissioned to build the Duomo, known today cana, il passaggio della strada, la strada come passaggio,

Alinea Editrice, Firenze, p. 59.

as the Duomo Vecchio, outside the walls of

Arezzo. In that same period, Maginardo was also

commissioned to build the parish church of San

Michele a Metelliano, the object of this study. In

order to understand the combination of different

elements that the parish church of Metelliano

presents today, it was important to study this ar-

chitect from Arezzo; and it was particularly rele-

vant to know that Maginardo travelled to the Ba-

silica of San Vitale in Ravenna at the beginning

of the 11th century. The reasons for his stay there

are made clear in a number of documents, in par-

ticular one dated 1026, 6. which states that the

work was commissioned by Bishop Adalbert.

The bishop, who was previously the Archbishop

of Ravenna, intended to have a new basilica,

modelled on the one in Ravenna, built just out-

side the city of Arezzo. Some texts suggest the

existence of study drawings made by Maginardo

during his journey, but they offer no more defi-

nite information. It is, however, important to note

that the Basilica of St Vitale influenced the Fig. 3. Giorgio Vasari il giovane, Pianta del Duomo Vecchio

(Uffizi, A4788)

6

As reported in the document of 1026 (Arch.Capit, N.86) «eo instar Ecclesiae sancti Vitalis primus iniecit» mentioned in

quod ipse architectus Ravennam ivit, et exemplar ecclesiae S. De Angelis d’Ossat G. (1978). Il “Duomo Vecchio” di Arezzo

Vitalis inde adduxit, atque solers fundamina in aula b.Donati,

2022, Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València

most likely be attributed to the Lombards. 9 The

2. History of the Parish Church of St Mi- discovery of early-medieval elements in the

building confirms this hypothesis. At the begin-

chael in Metelliano

ning of the new Millennium, Maginardo realized

The parish church of San Michele in Metelliano the present structure. The building has undergone

is a summary of Maginardi’s Ravenna experi- major transformations over the centuries: in 1439

ence within the framework of minor architecture AD, the bell tower, located at the centre of the

in the Cortona countryside. The structure is, to- façade, was replaced with the present-day bell

day, the result of multiple stratifications, which gable; and in 1674, plaster was added to the fa-

were determined by the needs of the community çade. During the restorations which began in

throughout the ages. The most evident interven- 1905, and which are documented in the Cortona

tion is, today, the one carried out by Maginardo periodical "L'Etruria", 10 important interventions

at the beginning of the 11th century. At that time, were carried out by Prof. Giuseppe Castellucci.

a radical demolition was carried out, and it was 11

The plaster was stripped from the building en-

later followed by the reconstruction that gave the tirely, uncovering, once again, the stone façade

building its present appearance. Some studies that lay underneath. This intervention not only al-

trace the origins of the structure back to Roman lowed for a better understanding of the structure

times, and it is hypothesised that an ancient tem- for purposes of stabilization, 12 but it also gave the

ple, dedicated to the god Bacchus, once rose building its present-day appearance. Without the

there. Traces of this previous structure can be plaster, the façade is probably as it once was:

found both on the tombstone of a Roman child, simple and austere, and more similar to Lombard

which was found during a 20th century excava- structures than Tuscan ones. In 1907 it was made

tion and is now preserved in the museum of the a national monument.

Accademia Etrusca di Cortona, and in the ety-

mology of the word Metelliano, which derives

from the name of an ancient Roman family, the

Gens Metellia. 7 One of the earliest references to

the building is found in a document dated 1014,

in which Henry II confirms that the abbey of

Santa Maria in Farneta holds, among other prop-

erties, a church dedicated to S. Angelo. 8 In 13th

century registrations and tithes, the structure is

listed as "S. Angelo del Succhio," bishopric of

the parish of Cortona. The original construction

of the church dates back to the 7th century and can Fig. 4. Two-dimensional survey.

7 11

Tüskés A. (2006) Il ciborio della chiesa di san michele ar- Giuseppe Castellucci Architect is a well-known figure on

cangelo a metelliano di cortona: una proposta di ricos- the Tuscan scene between the 19th and 20th centuries for the

truzione, p.2 large number of restorations he carried out. For further infor-

mation see: C. Cresti-L. Zangheri (1978). Architetti e

8

Minutoli G., Repole M. (2018). Pieve di San Michele a ingegneri nella Toscana dell'Ottocento, Uniedit, Firenze, pp.

Metelliano, Rilievo e analisi, in VI Convegno Internazionale 53–54; Sanguineti C. (2007). Scheda su Giuseppe Castel-

Reuso, Messina, p. 894. lucci, in Guida agli archivi di architetti e ingegneri del Nove-

9 cento in Toscana, a cura di E. Insabato, C. Ghelli, Edifir, Fi-

Tüskés A. (2006). Il ciborio della chiesa di…cit.

renze, pp. 113–119.

10

Pompilj G. (1906). S. Angelo a Metelliano in Cortona in 12

Minutoli G., Repole M. (2018) Pieve di San Michele a

L’Etruria, n.20, anno 1906.

Metelliano…cit. p. 894.

2022, Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València

The parish church of San Michele Arcangelo in Metelliano: the path of knowledge of a vernacular architecture

3. Method of analysis 4. Analysis of the structure

The discovery phase combined an analysis of his- San Michele a Metelliano presents a basilica plan

torical records with a direct analysis of the struc- with three naves at the end of which stand three

ture: the former provided a starting point for the semi-circular apses, and which has no transept.

understanding of the building and the discovery The ceiling alternates barrel vaults, near the

of known and unknown documentary sources apses and the entrance, and wooden trusses. The

that made it possible to answer the temporal nave is twice as wide as the side aisles, and it has

questions that a direct analysis alone could not; a slightly raised chancel. The three naves are sep-

and the latter, carried out on the materials, in- arated by two massive rectangular pillars alter-

volved the use of some of the most modern sur- nated by three narrow polygonal columns. From

veying methods, such as laser scanning and pho- a stratigraphic point of view, the wall face is

togrammetry. Together, the two analyses made it made of small sandstone blocks arranged in hor-

possible to study the condition of the structure izontal and parallel. The Lombard Romanesque

and elaborate thematic tables for its comprehen- façade preserves, above the door, a suspended

sion and conservation. The realization of the ar- prothyrum between two single-light windows.

chitectural survey, obtained through the two-di- The apsidal area is richer: it is made of three

mensional restitution of the 3D point cloud, was apses which are divided by pilasters made from

the base on which further analyses were carried materials that are in part from Roman remains.

out. Having accurate geometrical-dimensional From the above description, it is clear that some

data makes it possible to elaborate an equally ac- of the constructive and formal elements of the

curate restoration project. In the case of San structure are typical of pre-Romanesque, 14 Tus-

Michele a Metelliano, in the design phase of the can architecture, for example, the basilica plan

survey, attention was paid to the quality of the and the spatial distribution. Other elements, how-

data to be acquired, so that it suited the level of ever, are typical of Byzantine architecture. Inside

detail that needed to be obtained. 13 The subse- the parish church of San Michele in Metelliano,

quent analyses involved, on the one hand, the the alternated pillars and columns are an archi-

outline of the state of conservation of the build- tectural element taken directly from the basilica

ing − through a precise mapping of the materials of San Vitale in Ravenna. This architectural ele-

used and of the relative deterioration and altera- ment is, as Kubach also affirmed, hardly ever the

tions – and on the other hand, an analysis of the case in Tuscan churches, but it is very common

static architecture of the church through the iden- in buildings found in Northern Europe. In the

tification of both its structural elements and in- parish church of San Michele, the capitals them-

stabilities. Together with the instrumental anal- selves, which in Tuscan architecture are fash-

yses − and in order to understand the constructive ioned in various ways, have a square base and

and formal elements that are typical of the archi- trapezoidal sides, like those on the monolithic

tecture of Cortona − comparative analyses of columns in the presbytery of the church in Ra-

similar buildings were carried out. This made it venna, which, however, include a pulvino that is

possible to highlight the discordant aspects and absent in the church in Arezzo. The monolithic

elements in the structures that were analysed. columns, on the other hand, are octagonal, like in

13 14

Pancani G. (2017). San Michele Arcangelo a Metelliano, H. E. Kubach (1978). Architettura romanica, Milano,

Pieve in val D’Asse: metodologie per il rilevo, la documen- Electa Editrice.

tazione, la conservazione e la valorizzazione, Restauro Ar-

cheologico, n.1, FUP, p. 129

2022, Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València

other Tuscan parish churches but absent in S. Vi-

tale. A comparison with what was once the

Duomo Vecchio, would be of great interest, but,

unfortunately, only exterior views and a plan

made by Giorgio Vasari can still be found in his

book "Libro delle Piante". 15 The constructive

and formal elements that see the parish church of

San Michele in Metelliano listed among other

important Tuscan vernacular architectures are

found in the decorative elements outside the

apses. All three apses are divided by pilasters

made of terracotta and stone. The lateral ones are

also crowned in twin arches. The same construc-

tion technique is also present in the parish church

of Santa Maria di Confine, in Tuoro sul Trasi-

Fig 6. External view of the church. (Giorgio Ghelfi, 2021)

meno, where the twin arches are the only peculiar

element. In the case of the parish church in

Metelliano, however, the pilasters are also wor- 5. Conclusions

thy of note for their display of heterogeneous

ashlars. This peculiar characteristic is the result The interdisciplinary approach, carried out by ap-

of the reuse of remains from the pre-existing Ro- plying a rigorous scientific process, has made a

man temple of Bacchus. What is more, the reuse deeper understanding of the architectural peculi-

of material is not limited to the apses: the whole arities of the parish church of San Michele a

building presents elements re-claimed from Ro- Metelliano possible.

man structures, mainly travertine (also reworked, The conservation of this structure becomes inev-

like in the façade), and various bricks from the itable in a measure that is both critical and con-

imperial age bearing diagonal incisions. 16 scious and must be observed. The building, un-

like a great number of parishes found in Tuscany,

stands apart from the rest for characteristics that

are difficult to find elsewhere. The blending of

essential elements of Byzantine architecture, first

and foremost, the alternated pillars and columns,

and the constructive elements of the local tradi-

tion makes the building an important example of

vernacular architecture.

Fig 5. Interior view of the church. (Giorgio Ghelfi, 2021)

15 16

De Angelis d’Ossat G., Il “Duomo Vecchio” di Fatucchi A. (1977). La diocesi di Arezzo, (Corpus della

Arezzo…cit. p.7. scultura altomedievale, IX), Spoleto, p.117

2022, Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València

The parish church of San Michele Arcangelo in Metelliano: the path of knowledge of a vernacular architecture

Canestrelle A. (1904). L’Architettura medievale a

Siena e nell’antico territorio, Siena;

Cresti C., Zangheri L. (1978). Architetti e ingegneri

nella Toscana dell'Ottocento, Uniedit, Firenze;

De Angelis d’Ossat G. (1978). Il “Duomo Vecchio” di

Arezzo, «Palladio»;

De Angelis d’Ossat G., in «Atti e Memorie della Ac-

cademia Petrarca di Arezzo» N.S. XXXVII, p.

XXVI;

Kubach H. E. (1978). Architettura romanica, Milano,

Electa Editrice;

Fig 7. Lunette of one of the side doors of the parish church. Minutoli G., Repole M. (2018). Pieve di San Michele

(Giorgio Ghelfi, 2021) a Metelliano, Rilievo e analisi, in VI Convegno In-

ternazionale Reuso, Messina;

The ties to the territory are present in its every

Morelli E. (2007), Strade e paesaggi del-la Toscana,

element, from the materials to the stonework, il passaggio della strada, la strada come passag-

from the decorative elements to the construction. gio, Alinea Editrice, Firenze.

The reuse of building materials has been an inte- Moretti I., Stopani R. (1968). Chiese Romaniche in

gral part of this structure. From when it was first Valdelsa, Firenze 1968;

constructed in the 7th century A.D. until more re- Pancani G. (2017). San Michele Arcangelo a Metelli-

ano, Pieve in val D’Asse: metodologie per il

cent interventions, local materials, new or recov-

rilevo, la documentazione, la conservazione e la

ered, were used. From the palimpsest that has valorizzazione, «Restauro Archeologico», n.1;

arisen, it is possible to gain information about the

Pardi R. (2000). Architettura religiosa medievale in

changes that have taken place. Some examples Umbria, Spoleto;

can be found in the walls of the church, where it Pasqui U. (1899). Documenti per la storia della città

is possible to identify materials from pre-existing di Arezzo nel Medio Evo, Voll I-IV;

Roman buildings: travertine, used for significant Pompilj G. (1906). S. Angelo a Metelliano in Cortona

elements, or bricks dating back to the imperial in «L’Etruria», n.20;

age. Salmi M. (1912). Chiese romaniche in Casentino e in

Valdarno superiore, in “L’Arte”;

Even the monolithic columns are a synthesis of Salmi M. (1927). L’architettura romanica in Toscana,

the alternated pillars and columns found in the Milano-Roma;

architecture of Ravenna and the octagonal ones Salmi M. (1985). Chiese romaniche della campagna

found in other local churches, for example, the toscana, Milano;

Badia di Petroia, the church of San Pietro in Ac- Salmi M. (1972). Chiese romaniche in Val di Pesa, Fi-

qui, the church of San Martino di Pombia. 17 The renze;

parish church of San Michele a Metelliano be- Salvini R. (1973). Von Borsig A., Toskana. Unbe-

kannte romanische Kirchen, Monaco;

came a national monument in 1907, and today it

Salvini R. (1974). Architettura romanica religiosa nel

represents an important testament to be preserved contado fiorentino, Firenze;

and protected. Salvini R. (1981). Romanico Senese, Firenze;

Tafi A. (1998). Le antiche pievi. Madri vegliarde del

References popolo aretino, Cortona;

Tüskés A. (2006). Il ciborio della chiesa di san mi-

chele arcangelo a metelliano di cortona: una pro-

Bracco M. (1971). Architettura e scultura romanica in posta di ricostruzione.

Casentino, Firenze;

17

Pardi R. (2000). Architettura religiosa medievale in Um-

bria, Spoleto, p. 459.

2022, Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València

You might also like

- Saa Hb111-1998.the Domestic Kitchen Handbook.Document92 pagesSaa Hb111-1998.the Domestic Kitchen Handbook.John Evans0% (1)

- NBS - 005-Small Works-Attic-Refurbishment Sample Specification-2020-08-10Document37 pagesNBS - 005-Small Works-Attic-Refurbishment Sample Specification-2020-08-10Nay Win MaungNo ratings yet

- Fire Water Demand Calculations Annexure-1Document8 pagesFire Water Demand Calculations Annexure-1Jason Mullins94% (18)

- Tosco, Carlo. The Cross-In-square Plan in Carolingian ArchitectureDocument9 pagesTosco, Carlo. The Cross-In-square Plan in Carolingian ArchitectureImpcea0% (1)

- Labours of The Months and Zodiac Otranto CathedralDocument28 pagesLabours of The Months and Zodiac Otranto CathedralP NielsenNo ratings yet

- Activating The Effigy Donatellos Pecci TDocument16 pagesActivating The Effigy Donatellos Pecci TJavier Martinez EspuñaNo ratings yet

- The Church of San Miniato Al Monte, Florence: Astronomical and Astrological Connections Valerie ShrimplinDocument10 pagesThe Church of San Miniato Al Monte, Florence: Astronomical and Astrological Connections Valerie ShrimplinberixNo ratings yet

- Ackerman, Palladio, Michelangelo and Publica MagnificentiaDocument16 pagesAckerman, Palladio, Michelangelo and Publica MagnificentiaAna RuizNo ratings yet

- Glowa, RemarksDocument14 pagesGlowa, RemarksannaglowaNo ratings yet

- Architectural PresentationDocument9 pagesArchitectural PresentationKushagra ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Kapnikarea: Byzantine Church of Ermou SreetDocument20 pagesKapnikarea: Byzantine Church of Ermou SreetSir ArtoriasNo ratings yet

- Romanesque Art: Caen, FranceDocument40 pagesRomanesque Art: Caen, FrancePrateek SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- CSL Tedolinda JurkovicDocument28 pagesCSL Tedolinda JurkovicTea MađarevićNo ratings yet

- Chiesa Di Donnalbina EnglishDocument4 pagesChiesa Di Donnalbina EnglishNestor JrNo ratings yet

- The Byzantine Wall-Paintings in The Church of Saint Theodore at Platanos, Kynouria (Arcadia)Document15 pagesThe Byzantine Wall-Paintings in The Church of Saint Theodore at Platanos, Kynouria (Arcadia)TanjciA*No ratings yet

- Cortona The-Best-Of-Cortona-In-Half-A-Day 2019 07 18 11 09 53Document8 pagesCortona The-Best-Of-Cortona-In-Half-A-Day 2019 07 18 11 09 53Corina NedaNo ratings yet

- Basilica Di San LorenzoDocument43 pagesBasilica Di San LorenzoCyan ManaleseNo ratings yet

- Understanding An Era Through The Chora ChurchDocument6 pagesUnderstanding An Era Through The Chora Churchİdil ÖzenelNo ratings yet

- San Marco Byzantium and The Myths of Venice PDFDocument71 pagesSan Marco Byzantium and The Myths of Venice PDFHakanBulutNo ratings yet

- Phialai On Mount AthosDocument28 pagesPhialai On Mount Athosirfankara85No ratings yet

- 2 Convivium 1-2014-2 9Document25 pages2 Convivium 1-2014-2 9Isik Eflan TINAZNo ratings yet

- BOURAS The Soteira Lykodemou at Athens Architecture PDFDocument15 pagesBOURAS The Soteira Lykodemou at Athens Architecture PDFdrfitti1978No ratings yet

- Panselinos MilinerDocument33 pagesPanselinos Milinerzarchester100% (2)

- Theory of Architecture: 18AATC106Document65 pagesTheory of Architecture: 18AATC106Pooja MantriNo ratings yet

- Charalambos Bakirtzis Pelli Mastora-Mosaics - Rotonda.thessalonikiDocument14 pagesCharalambos Bakirtzis Pelli Mastora-Mosaics - Rotonda.thessalonikizarchesterNo ratings yet

- 1.3.1.10. 2021 NicaeaDocument22 pages1.3.1.10. 2021 NicaeathrasarichNo ratings yet

- RenaissanceDocument29 pagesRenaissanceRuben FogarasNo ratings yet

- Glass ProphecyPriesthoodModena 2000Document14 pagesGlass ProphecyPriesthoodModena 2000MélNo ratings yet

- The Art and Architecture of Chora Monastery in Comparison With Its East European and Italian ContemporariesDocument12 pagesThe Art and Architecture of Chora Monastery in Comparison With Its East European and Italian Contemporariesmaximos74No ratings yet

- Mathews, T., (1985), " Notes On The Atik Mustafa Paşa Camii in Istanbul and Its Frescoes"Document23 pagesMathews, T., (1985), " Notes On The Atik Mustafa Paşa Camii in Istanbul and Its Frescoes"Duygu KNo ratings yet

- Romanesque ArchitectureDocument7 pagesRomanesque ArchitectureNiharikaNo ratings yet

- Salona at The Time of Bishop Hesychius PDFDocument12 pagesSalona at The Time of Bishop Hesychius PDFpostiraNo ratings yet

- The Architectural Iconography of The Late Byzantine MonasteryDocument36 pagesThe Architectural Iconography of The Late Byzantine MonasteryDusan LjubicicNo ratings yet

- International Center of Medieval Art, The University of Chicago Press GestaDocument13 pagesInternational Center of Medieval Art, The University of Chicago Press GestaMalena TrejoNo ratings yet

- About Pisa CathedralDocument5 pagesAbout Pisa CathedralSnow WhiteNo ratings yet

- Byzantine Art in Post-Byzantine Southern ItalyDocument18 pagesByzantine Art in Post-Byzantine Southern ItalyBurak SıdarNo ratings yet

- Spring: HistoryDocument41 pagesSpring: HistoryAhmad RNo ratings yet

- Chatzidakis Hosios LoukasDocument96 pagesChatzidakis Hosios Loukasamadgearu100% (4)

- A Masterpiece Restored: James WatsonDocument6 pagesA Masterpiece Restored: James WatsonJames WatsonNo ratings yet

- Articulo 6 - TdVeTDocument57 pagesArticulo 6 - TdVeTAntonio CampitelliNo ratings yet

- A. Moskovitz, A Tale of Two Cities Pavia, Milan, and The Arca Di Sant' AgostinoDocument9 pagesA. Moskovitz, A Tale of Two Cities Pavia, Milan, and The Arca Di Sant' AgostinoM McKinneyNo ratings yet

- 04 Gojko Subotic Visoki DecaniDocument42 pages04 Gojko Subotic Visoki DecaniJasmina S. Ciric100% (1)

- The Church of Kapnikarea in Athens - N. GkiolesDocument13 pagesThe Church of Kapnikarea in Athens - N. GkiolesMaronasNo ratings yet

- Dana Jenei, LES PEINTURES MURALES DE L'ÉGLISE DE MĂLÂNCRAV. NOTES AVANT LA RESTAURATIONDocument34 pagesDana Jenei, LES PEINTURES MURALES DE L'ÉGLISE DE MĂLÂNCRAV. NOTES AVANT LA RESTAURATIONDana JeneiNo ratings yet

- Italian Gothic ArchitectureDocument6 pagesItalian Gothic ArchitectureAndree AndreeaNo ratings yet

- Basilica San Marco InteriorDocument29 pagesBasilica San Marco Interioryinhanyue100% (1)

- Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Athonite de PDFDocument28 pagesByzantine and Post-Byzantine Athonite de PDFDaniela-LuminitaIvanoviciNo ratings yet

- Archaeological Institute of America American Journal of ArchaeologyDocument32 pagesArchaeological Institute of America American Journal of ArchaeologyDejan ZivicNo ratings yet

- Reviewed Work(s) La Real Chiesa Di San Lorenzo in Torino by Giuseppe Michele CrepaldiDocument3 pagesReviewed Work(s) La Real Chiesa Di San Lorenzo in Torino by Giuseppe Michele CrepaldiBochao SunNo ratings yet

- A Baptistery Below The Baptistery of Florence Franklin TokerDocument12 pagesA Baptistery Below The Baptistery of Florence Franklin TokerDavi ChileNo ratings yet

- FAB 03.27. Stamenova-Atanasova, M. - Overview of The Results From The Excavation at The Medieval Necropolis at The Orta-Dzamija Location in StrumicaDocument8 pagesFAB 03.27. Stamenova-Atanasova, M. - Overview of The Results From The Excavation at The Medieval Necropolis at The Orta-Dzamija Location in StrumicaohridasskiNo ratings yet

- HistoryofConstructionCulturesVOLUME2 VandenabeeleDocument9 pagesHistoryofConstructionCulturesVOLUME2 Vandenabeelevu thienNo ratings yet

- Giakoumis K. - Karajskaj Gj. (2004), New Architectural and Epigraphic Data On The Site and Catholicon of The Monastery of St. Nikolaos at Mesopotam (Southern Albania) ', Monumentet, v. 1, Pp. 81-95.Document19 pagesGiakoumis K. - Karajskaj Gj. (2004), New Architectural and Epigraphic Data On The Site and Catholicon of The Monastery of St. Nikolaos at Mesopotam (Southern Albania) ', Monumentet, v. 1, Pp. 81-95.Kosta GiakoumisNo ratings yet

- Santa Maria Della Salute 1999Document27 pagesSanta Maria Della Salute 1999Rough RaiderNo ratings yet

- The Chora Monastery and Its Patrons: Finding A Place in HistoryDocument70 pagesThe Chora Monastery and Its Patrons: Finding A Place in HistoryCARMEN100% (1)

- Selina BallanceDocument43 pagesSelina Ballancegonul demetNo ratings yet

- Cali Aet AliDocument7 pagesCali Aet AliirfanNo ratings yet

- VanMarle Development Vol4 1924Document560 pagesVanMarle Development Vol4 1924sallaydoraNo ratings yet

- Ceraldi Carla Layouted LibreDocument9 pagesCeraldi Carla Layouted LibreStephen.KNo ratings yet

- The Mural Paintings From The Exonarthex PDFDocument14 pagesThe Mural Paintings From The Exonarthex PDFomnisanctus_newNo ratings yet

- The Multi-Layer Composition of A IconostasisDocument16 pagesThe Multi-Layer Composition of A IconostasisVictor TerisNo ratings yet

- Ar A Prova de ExplosãoDocument2 pagesAr A Prova de ExplosãoMailthon Ritter GilNo ratings yet

- F R Ee Man U Al S: Pipe Handbook ManualDocument3 pagesF R Ee Man U Al S: Pipe Handbook ManualDenstar Ricardo SilalahiNo ratings yet

- FMDS0281Document56 pagesFMDS0281HữuĐầuĐấtNo ratings yet

- Foundation Analysis and Design: Michael Valley, S.EDocument25 pagesFoundation Analysis and Design: Michael Valley, S.EchopraNo ratings yet

- PIP STF05121 Anchor Fabrication and Installation Into ConcreteDocument6 pagesPIP STF05121 Anchor Fabrication and Installation Into Concretecarrimonn11No ratings yet

- SMC Solenoid Valves CatalogDocument13 pagesSMC Solenoid Valves Catalogmon012No ratings yet

- Pre DCR ReportDocument6 pagesPre DCR ReportÂsÏF MåñSùRïNo ratings yet

- Public Procuement Rule of NepalDocument147 pagesPublic Procuement Rule of NepalShreeNo ratings yet

- Hydraulic Elevators Basic ComponentsDocument16 pagesHydraulic Elevators Basic ComponentsIkhwan Nasir100% (2)

- Sample SFS SpreadsheetDocument18 pagesSample SFS SpreadsheetJred MondejarNo ratings yet

- M.B.M Engneerng College Jodhpur, Rajasthan: Project Report On Recent Advanced Hghway MateralsDocument49 pagesM.B.M Engneerng College Jodhpur, Rajasthan: Project Report On Recent Advanced Hghway MateralsvrrrruNo ratings yet

- Aama 450-06Document26 pagesAama 450-06samuelNo ratings yet

- FAG Bearing Roller CagesDocument19 pagesFAG Bearing Roller Cagesomni_partsNo ratings yet

- Api 510 Exam: Api576 Questions - 02Document3 pagesApi 510 Exam: Api576 Questions - 02korichiNo ratings yet

- Green BuildingDocument7 pagesGreen Buildingjayraj patilNo ratings yet

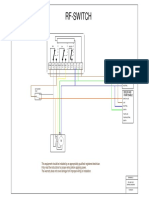

- RF Switch 3 Way ValveDocument1 pageRF Switch 3 Way ValveHillbeleyNo ratings yet

- Bsc071 - Glamz - Civil - Submittal LogDocument16 pagesBsc071 - Glamz - Civil - Submittal Logقاسم ابرار محمدNo ratings yet

- Stego HG140 400V 2017 enDocument1 pageStego HG140 400V 2017 enJulek VargaNo ratings yet

- 4.2 Continuous Load Path: 4.3 Overall FormDocument10 pages4.2 Continuous Load Path: 4.3 Overall FormSirajMalikNo ratings yet

- Company Profile - Hannik Engineering - NEW2.1Document33 pagesCompany Profile - Hannik Engineering - NEW2.1ikehdNo ratings yet

- 5.0 Tension-Members (1) BENG17-1Document20 pages5.0 Tension-Members (1) BENG17-1Erick Elvis ThomassNo ratings yet

- Prysmian WEDGTAP IntroductionDocument3 pagesPrysmian WEDGTAP IntroductionrocketvtNo ratings yet

- Flexural Analysis1Document66 pagesFlexural Analysis1hannan mohsinNo ratings yet

- Parkland Company Brochure Company Tri Fold 4 2012Document2 pagesParkland Company Brochure Company Tri Fold 4 2012Saheed PoyilNo ratings yet

- Valve Manual Pocket EditionDocument23 pagesValve Manual Pocket EditionBùi Cảnh Trung100% (1)

- A - Study - On - Some - Geotechnical - Properties 19-11-2019 PDFDocument8 pagesA - Study - On - Some - Geotechnical - Properties 19-11-2019 PDFkrunalshah1987No ratings yet