Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Babbie Kapitel 6

Babbie Kapitel 6

Uploaded by

余耒Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Babbie Kapitel 6

Babbie Kapitel 6

Uploaded by

余耒Copyright:

Available Formats

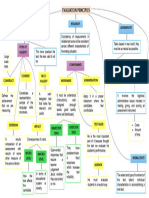

CHAPTER 6

From Concept to Measurement

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

The interrelated steps of

conceptualization, operationalization,

and measurement allow research-

ers to turn a general idea for a

research topic into useful and valid

measurements in the real world.

An essential part of this process Introduction A Note on Dimensions

involves transforming the relatively Measuring Anything That Exists Defining Variables and Attributes

Conceptions, Concepts, and Reality Levels of Measurement

vague terms of ordinary language Concepts as Constructs Single or Multiple Indicators

Some Illustrations of

into precise objects of study with Conceptualization

Operationalization Choices

Indicators and Dimensions

Operationalization Goes On and

well-defined and measurable The Interchangeability of Indicators

On

Real, Nominal, and Operational

meanings. Definitions Criteria of Measurement Quality

Creating Conceptual Order Precision and Accuracy

An Example of Conceptualization: Reliability

The Concept of Anomie Validity

Definitions in Descriptive Who Decides What’s Valid?

and Explanatory Studies Tension between Reliability and

Validity

Operationalization Choices

Range of Variation The Ethics of Measurement

Variations between the Extremes

Aplia for The Practice of Social Research

After reading, go to “Online Study Resources” at the end of this chapter for

instructions on how to use Aplia’s homework and learning resources.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 163 11/18/11 5:24 PM

164 ■ Chapter 6: From Concept to Measurement

Introduction use the term measurement instead, meaning careful,

deliberate observations of the real world for the

This chapter and the next one deal with how purpose of describing objects and events in terms of

researchers move from a general idea about what the attributes composing a variable.

they want to study to effective and well-defined You may have some reservations about the

measurements in the real world. This chapter ability of science to measure the really important

discusses the interrelated processes of conceptu- aspects of human social existence. If you’ve read

alization, operationalization, and measurement. research reports dealing with something like liber-

Chapter 7 builds on this foundation to discuss types alism or religion or prejudice, you may have been

of measurements that are more complex. dissatisfied with the way the researchers measured

Consider a notion such as “satisfaction with col- whatever they were studying. You may have felt

lege.” I’m sure you know some people who are very that they were too superficial, that they missed the

satisfied, some who are very dissatisfied, and many aspects that really matter most. Maybe they mea-

who are between those extremes. Moreover, you can sured religiosity as the number of times a person

probably place yourself somewhere along that satis- went to religious services, or maybe they measured

faction spectrum. While this probably makes sense liberalism by how people voted in a single election.

to you as a general matter, how would you go about Your dissatisfaction would surely have increased if

measuring how different students were in this re- you had found yourself being misclassified by the

gard, so you could place them along that spectrum? measurement system.

There are some comments students make in Your feeling of dissatisfaction reflects an im-

conversations (such as “This place sucks”) that portant fact about social research: Most of the var-

would tip you off as to where they stood. Or, in iables we want to study don’t actually exist in the

a more active effort, you can probably think of way that rocks exist. Indeed, they are made up.

questions you might ask students to learn about Moreover, they seldom have a single, unambigu-

their satisfaction (such as “How satisfied are you ous meaning.

with . . . ?”). Perhaps there are certain behaviors To see what I mean, suppose we want to study

(class attendance, use of campus facilities, setting political party affiliation. To measure this variable,

the dean’s office on fire) that would suggest differ- we might consult the list of registered voters to

ent levels of satisfaction. As you think about ways note whether the people we were studying were

of measuring satisfaction with college, you are en- registered as Democrats or Republicans and take

gaging in the subject matter of this chapter. that as a measure of their party affiliation. But we

We begin by confronting the hidden concern could also simply ask someone what party they

people sometimes have about whether it’s truly identify with and take their response as our mea-

possible to measure the stuff of life: love, hate, sure. Notice that these two different measurement

prejudice, religiosity, radicalism, alienation. The possibilities reflect somewhat different definitions

answer is yes, but it will take a few pages to see of political party affiliation. They might even pro-

how. Once we establish that researchers can mea- duce different results: Someone may have reg-

sure anything that exists, we’ll turn to the steps istered as a Democrat years ago but gravitated

involved in doing just that. more and more toward a Republican philosophy

over time. Or someone who is registered with

neither political party may, when asked, say she is

Measuring Anything That Exists affiliated with the one she feels the most kinship

Earlier in this book, I said that one of the two pil- with.

lars of science is observation. Because this word Similar points apply to religious affiliation. Some-

can suggest a casual, passive activity, scientists often times this variable refers to official membership in

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 164 11/18/11 5:24 PM

Measuring Anything That Exists ■ 165

a particular church, temple, mosque, and so forth; With additional experience, we notice some-

other times it simply means whatever religion, if thing more. A lot of the people who call African

any, you identify yourself with. Perhaps to you it Americans ugly names also seem to want women to

means something else, such as attendance at reli- “stay in their place.” They are also likely to think mi-

gious services. norities are inferior to the majority and that women

The truth is that neither party affiliation nor are inferior to men. These several tendencies often

religious affiliation has any real meaning, if by “real” appear together in the same people and also have

we mean corresponding to some objective aspect of something in common. At some point, someone

reality. These variables do not exist in nature. They had a bright idea: “Let’s use the word prejudiced as a

are merely terms we’ve made up and assigned shorthand notation for people like that. We can use

specific meanings to for some purpose, such as the term even if they don’t do all those things—as

doing social research. long as they’re pretty much like that.”

But, you might object, political affiliation and Being basically agreeable and interested in

religious affiliation—and a host of other things social efficiency, we went along with the system. That’s

researchers are interested in, such as prejudice or where “prejudice” came from. We never observed

compassion—have some reality. After all, research- it. We just agreed to use it as a shortcut, a name

ers make statements about them, such as “In that represents a collection of apparently related

Happytown, 55 percent of the adults affiliate with phenomena that we’ve each observed in the course

the Republican Party, and 45 percent of them are of life. In short, we made it up.

Episcopalians. Overall, people in Happytown are Here’s another clue that prejudice isn’t some-

low in prejudice and high in compassion.” Even thing that exists apart from our rough agreement

ordinary people, not just social researchers, have to use the term in a certain way. Each of us devel-

been known to make statements like that. If these ops our own mental image of what the set of real

things don’t exist in reality, what is it that we’re phenomena we’ve observed represents in general

measuring and talking about? and what these phenomena have in common.

What indeed? Let’s take a closer look by When I say the word prejudice, it evokes a mental

considering a variable of interest to many social image in your mind, just as it evokes one in mine.

researchers (and many other people as It’s as though file drawers in our minds contained

well)—prejudice. thousands of sheets of paper, with each sheet of

paper labeled in the upper right-hand corner. A

sheet of paper in each of our minds has the term

Conceptions, Concepts, prejudice on it. On your sheet are all the things

and Reality you’ve been told about prejudice and everything

As we wander down the road of life, we observe you’ve observed that seems to be an example of it.

a lot of things and know they are real through My sheet has what I’ve been told about it plus all

our observations, and we hear reports from other the things I’ve observed that seem examples of it—

people that seem real. For example: and mine isn’t the same as yours.

The technical term for those mental images,

• We personally hear people say nasty things

those sheets of paper in our mental file drawers,

about minority groups.

is conception. That is, I have a conception of preju-

• We hear people say that women are inferior dice, and so do you. We can’t communicate these

to men. mental images directly, so we use the terms written

• We read that women and minorities earn less in the upper right-hand corner of our own mental

for the same work. sheets of paper as a way of communicating about

• We learned about “ethnic cleansing” and wars our conceptions and the things we observe that

in which one ethnic group tries to eradicate are related to those conceptions. These terms make

another. it possible for us to communicate and eventually

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 165 11/18/11 5:24 PM

166 ■ Chapter 6: From Concept to Measurement

Research in Real Life

Gender and Race in City Streets You can read excerpts of the book online and can hear Anderson

In the early 1970s, Elijah Anderson spent three years observing life in a black, discuss the book in an interview with BBC’s Laurie Taylor at the links on

working-class neighborhood in South Chicago, focusing on Jelly’s, a combina- your Sociology CourseMate at www.cengagebrain.com.

tion bar and liquor store. While some people still believe that impoverished

Elijah Anderson, A Place on the Corner: A Study of Black Street Corner Men

neighborhoods in the inner city are socially chaotic and disorganized,

Anderson’s study and others like it have clearly demonstrated a definite social

structure there that guides the behavior of its participants. Much of his interest

centered on systems of social status and how the 55 or so regulars at Jelly’s

worked those systems to establish themselves among their peers.

In the second edition of this classic study of urban life, Elijah

Anderson returned to Jelly’s and the surrounding neighborhood. There

he found several changes, largely due to the outsourcing of manufactur-

(University of Chicago Press, 2004).

ing jobs overseas that has brought economic and mental depression to

many of the residents. These changes, in turn, had also altered the nature

of social organization.

For a research methods student, the book offers many insights into

the process of establishing rapport with people being observed in their

natural surroundings. Further, Anderson offers excellent examples of

how concepts are established in qualitative research.

agree on what we specifically mean by those words—ranging from 1 to 400. Several sources,

terms. In social research, the process of coming moreover, will suggest that if the Inuit have sev-

to an agreement about what terms mean is eral words for snow, so does English. Cecil Adams,

conceptualization, and the result is called a for example, lists “snow, slush, sleet, hail, powder,

concept. See “Research in Real Life” for a glimpse at hard pack, blizzard, flurries, flake, dusting, crust,

a project that reveals a lot about conceptualization. avalanche, drift, frost, and iceberg” (Straight Dope

Perhaps you’ve heard some reference to the 2001). This illustrates the ambiguities in the field

many words Eskimos have for snow, as an example with regard to the concepts and words that we use

of how environment can shape language. Here’s in everyday communications and that also serve as

an exercise you might enjoy when you’re ready the grounding for social research.

to take a break from reading. Search the web Let’s take another example of a conception.

for “Eskimo words for snow.” You may be sur- Suppose that I’m going to meet someone named

prised by what you find. You’re likely to discover Pat, whom you already know. I ask you what Pat is

wide disagreement on the number of, say, Inuit, like. Now suppose that you’ve seen Pat help lost chil-

dren find their parents and put a tiny bird back in its

nest. Pat got you to take turkeys to poor families on

Thanksgiving and to visit a children’s hospital on

conceptualization The mental process whereby Christmas. You’ve seen Pat weep through a movie

fuzzy and imprecise notions (concepts) are made about a mother overcoming adversities to save and

more specific and precise. So you want to study protect her child. As you search through your mental

prejudice. What do you mean by “prejudice”? Are files, you may find all or most of those phenomena

there different kinds of prejudice? What are they?

recorded on a single sheet labeled “compassionate.”

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 166 11/18/11 5:24 PM

Measuring Anything That Exists ■ 167

You look over the other entries on the page, and you his or her mental images to correspond with such

find they seem to provide an accurate description of agreements. But because all of us have different

Pat. So you say, “Pat is compassionate.” experiences and observations, no two people end

Now I leaf through my own mental file drawer up with exactly the same set of entries on any

until I find a sheet marked “compassionate.” I then sheet in their file systems. If we want to measure

look over the things written on my sheet, and I say, “prejudice” or “compassion,” we must first stipulate

“Oh, that’s nice.” I now feel I know what Pat is like, what, exactly, counts as prejudice or compassion

but my expectations reflect the entries on my file for our purposes.

sheet, not yours. Later, when I meet Pat, I happen Returning to the assertion made at the outset

to find that my own experiences correspond to the of this chapter, we can measure anything that’s

entries I have on my “compassionate” file sheet, real. We can measure, for example, whether Pat

and I say that you sure were right. actually puts the little bird back in its nest, visits

But suppose my observations of Pat contradict the hospital on Christmas, weeps at the movie, or

the things I have on my file sheet. I tell you that refuses to contribute to saving the whales. All of

I don’t think Pat is very compassionate, and we those behaviors exist, so we can measure them.

begin to compare notes. But is Pat really compassionate? We can’t answer

You say, “I once saw Pat weep through a movie that question; we can’t measure compassion in any

about a mother overcoming adversity to save and objective sense, because compassion doesn’t exist

protect her child.” I look at my “compassionate in the way that those things I just described exist.

sheet” and can’t find anything like that. Looking Compassion exists only in the form of the agree-

elsewhere in my file, I locate that sort of phenom- ments we have about how to use the term in

enon on a sheet labeled “sentimental.” I retort, communicating about things that are real.

“That’s not compassion. That’s just sentimentality.”

To further strengthen my case, I tell you that

I saw Pat refuse to give money to an organiza- Concepts as Constructs

tion dedicated to saving whales from extinction. If you recall the discussions of postmodernism in

“That represents a lack of compassion,” I argue. Chapter 3, you’ll recognize that some people would

You search through your files and find saving the object to the degree of “reality” I’ve allowed in

whales on two sheets—“environmental activism” the preceding comments. Did Pat “really” visit the

and “cross-species dating”—and you say so. Even- hospital on Christmas? Does the hospital “really”

tually, we set about comparing the entries we have exist? Does Christmas? Though we aren’t going

on our respective sheets labeled “compassionate.” to be radically postmodern in this chapter, I think

We then discover that many of our mental images you’ll recognize the importance of an intellectually

corresponding to that term differ. tough view of what’s real and what’s not. (When

In the big picture, language and communica- the intellectual going gets tough, the tough become

tion work only to the extent that you and I have social scientists.)

considerable overlap in the kinds of entries we In this context, Abraham Kaplan (1964) dis-

have on our corresponding mental file sheets. The tinguishes three classes of things that scientists

similarities we have on those sheets represent the measure. The first class is direct observables: those

agreements existing in our society. As we grow up, things we can observe rather simply and directly,

we’re told approximately the same thing when like the color of an apple or the check mark on a

we’re first introduced to a particular term, though questionnaire. The second class, indirect observables,

our nationality, gender, race, ethnicity, region, require “relatively more subtle, complex, or indi-

language, or other cultural factors may shade our rect observations” (1964: 55). We note a person’s

understanding of concepts. check mark beside “female” in a questionnaire and

Dictionaries formalize the agreements our soci- have indirectly observed that person’s sex. History

ety has about such terms. Each of us, then, shapes books or minutes of corporate board meetings

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 167 11/18/11 5:24 PM

168 ■ Chapter 6: From Concept to Measurement

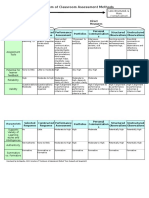

TABLE 61

What Social Scientists Measure

Examples

Direct observables Physical characteristics (sex, height, skin color) of a person

being observed and/or interviewed

Indirect observables Characteristics of a person as indicated by answers given in a

self-administered questionnaire

Constructs Level of alienation, as measured by a scale that is created by

combining several direct and/or indirect observables

provide indirect observations of past social actions. Usually, however, we fall into the trap of be-

Finally, the third class of observables consists of lieving that terms for constructs do have intrinsic

constructs—theoretical creations that are based on meaning, that they name real entities in the world.

observations but that cannot be observed directly That danger seems to grow stronger when we begin

or indirectly. A good example is intelligence quo- to take terms seriously and attempt to use them

tient, or IQ. It is constructed mathematically from precisely. Further, the danger is all the greater in

observations of the answers given to a large num- the presence of experts who appear to know more

ber of questions on an IQ test. No one can directly than we do about what the terms really mean: It’s

or indirectly observe IQ. It is no more a “real” char- easy to yield to authority in such a situation.

acteristic of people than is compassion or prejudice. Once we assume that terms like prejudice and

See Table 6-1 for more examples of what social compassion have real meanings, we begin the tor-

scientists measure. tured task of discovering what those real meanings

Kaplan (1964: 49) defines concept as a “family are and what constitutes a genuine measurement

of conceptions.” A concept is, as Kaplan notes, a of them. Regarding constructs as real is called

construct, something we create. Concepts such as reification. The reification of concepts in day-to-day

compassion and prejudice are constructs created life is quite common. In science, we want to be quite

from your conception of them, my conception of clear about what it is we are actually measuring, but

them, and the conceptions of all those who have this aim brings a pitfall with it. Settling on the “best”

ever used these terms. They cannot be observed way of measuring a variable in a particular study

directly or indirectly, because they don’t exist. We may imply that we’ve discovered the “real” mean-

made them up. ing of the concept involved. In fact, concepts have

To summarize, concepts are constructs derived no real, true, or objective meanings—only those we

by mutual agreement from mental images (con- agree are best for a particular purpose.

ceptions). Our conceptions summarize collections Does this discussion imply that compassion,

of seemingly related observations and experiences. prejudice, and similar constructs can’t be mea-

Although the observations and experiences are sured? Interestingly, the answer is no. (And a good

real, at least subjectively, conceptions, and the con- thing, too, or a lot of us social researcher types

cepts derived from them, are only mental creations. would be out of work.) I’ve said that we can mea-

The terms associated with concepts are merely sure anything that’s real. Constructs aren’t real

devices created for the purposes of filing and com- in the way that trees are real, but they do have

munication. A term such as prejudice is, objectively another important virtue: They are useful. That

speaking, only a collection of letters. It has no in- is, they help us organize, communicate about,

trinsic reality beyond that. Is has only the meaning and understand things that are real. They help us

we agree to give it. make predictions about real things. Some of those

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 168 11/18/11 5:24 PM

Conceptualization ■ 169

predictions even turn out to be true. Constructs presence or absence of the concept we’re studying.

can work this way because, although not real or Here’s an example.

observable in themselves, they have a definite rela- We might agree that visiting children’s hospitals

tionship to things that are real and observable. The during Christmas and Hanukkah is an indicator of

bridge from direct and indirect observables to useful compassion. Putting little birds back in their nests

constructs is the process called conceptualization. might be agreed on as another indicator, and so

forth. If the unit of analysis for our study is the

individual person, we can then observe the pres-

Conceptualization ence or absence of each indicator for each person

As we’ve seen, day-to-day communication usually under study. Going beyond that, we can add up

occurs through a system of vague and general the number of indicators of compassion observed

agreements about the use of terms. Although for each individual. We might agree on ten specific

you and I do not agree completely about the use of indicators, for example, and find six present in our

the term compassionate, I’m probably safe in assum- study of Pat, three for John, nine for Mary, and so

ing that Pat won’t pull the wings off flies. A wide forth.

range of misunderstandings and conflict—from the Returning to our question about whether men

interpersonal to the international—is the price we or women are more compassionate, we might

pay for our imprecision, but somehow we muddle calculate that the women we studied displayed an

through. Science, however, aims at more than average of 6.5 indicators of compassion, the men

muddling; it cannot operate in a context of such an average of 3.2. On the basis of our quantitative

imprecision. analysis of group difference, we might therefore

The process through which we specify what conclude that women are, on the whole, more

we mean when we use particular terms in research compassionate than men.

is called conceptualization. Suppose we want to Usually, though, it’s not that simple. Imagine

find out, for example, whether women are more you’re interested in understanding a small fun-

compassionate than men. I suspect many people damentalist religious cult, particularly their harsh

assume this is the case, but it might be interest- views on various groups: gays, nonbelievers,

ing to find out if it’s really so. We can’t meaning- feminists, and others. In fact, they suggest that

fully study the question, let alone agree on the anyone who refuses to join their group and abide

answer, without some working agreements about by its teachings will “burn in hell.” In the context

the meaning of compassion. They are “working” of your interest in compassion, they don’t seem

agreements in the sense that they allow us to work to have much. And yet, the group’s literature

on the question. We don’t need to agree or even often speaks of their compassion for others. You

pretend to agree that a particular specification is want to explore this seeming paradox.

ultimately the best one. To pursue this research interest, you might

Conceptualization, then, produces a specific, arrange to interact with cult members, getting to

agreed-on meaning for a concept for the purposes know them and learning more about their views.

of research. This process of specifying exact mean- You could tell them you were a social researcher

ing involves describing the indicators we’ll be using interested in learning about their group, or per-

to measure our concept and the different aspects of haps you would just express an interest in learning

the concept, called dimensions. more, without saying why.

Indicators and Dimensions indicator An observation that we choose to con-

Conceptualization gives definite meaning to a con- sider as a reflection of a variable we wish to study.

Thus, for example, attending religious services might

cept by specifying one or more indicators of what

be considered an indicator of religiosity.

we have in mind. An indicator is a sign of the

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 169 11/18/11 5:24 PM

170 ■ Chapter 6: From Concept to Measurement

In the course of your conversations with group dimension” of compassion and the “action di-

members and perhaps attendance of religious mension” of compassion. In a different grouping

services, you would put yourself in situations scheme, we might distinguish “compassion for

where you could come to understand what the humans” from “compassion for animals.” Or we

cult members mean by compassion. You might might see compassion as helping people have

learn, for example, that members of the group what we want for them versus what they want

were so deeply concerned about sinners burning in for themselves. Still differently, we might distin-

hell that they were willing to be aggressive, even guish compassion as forgiveness from compas-

violent, to make people change their sinful ways. sion as pity.

Within their own paradigm, then, cult members Thus, we could subdivide compassion into sev-

would see beating up gays, prostitutes, and abor- eral clearly defined dimensions. A complete con-

tion doctors as acts of compassion. ceptualization involves both specifying dimensions

Social researchers focus their attention on and identifying the various indicators for each.

the meanings that the people under study give to When Jonathan Jackson (2005: 301) set out

words and actions. Doing so can often clarify the to measure “fear of crime,” he considered seven

behaviors observed: At least now you understand different dimensions:

how the cult can see violent acts as compassionate.

On the other hand, paying attention to what words • The frequency of worry about becom-

ing a victim of three personal crimes and

and actions mean to the people under study almost

two property crimes in the immediate

always complicates the concepts researchers are

neighbourhood . . .

interested in. (We’ll return to this issue when we

discuss the validity of measures, toward the end of • Estimates of likelihood of falling victim to each

this chapter.) crime locally

Whenever we take our concepts seriously and

• Perceptions of control over the possibility of

set about specifying what we mean by them, we becoming a victim of each crime locally

discover disagreements and inconsistencies. Not

only do you and I disagree, but each of us is likely • Perceptions of the seriousness of the conse-

quences of each crime

to find a good deal of muddiness within our own

mental images. If you take a moment to look at • Beliefs about the incidence of each crime

what you mean by compassion, you’ll probably locally

find that your image contains several kinds of

• Perceptions of the extent of social physical inci-

compassion. That is, the entries on your mental file vilities in the neighbourhood

sheet can be combined into groups and subgroups,

say, compassion toward friends, co-religionists,

• Perceptions of community cohesion, including

informal social control and trust/social capital

humans, and birds. You may also find several dif-

ferent strategies for making combinations. For Sometimes conceptualization aimed at identi-

example, you might group the entries into feelings fying different dimensions of a variable leads to a

and actions. different kind of distinction. We may conclude that

The technical term for such groupings is we’ve been using the same word for meaningfully

dimension, a specifiable aspect of a concept. distinguishable concepts. In the following example,

For instance, we might speak of the “feeling the researchers find (1) that “violence” is not a

sufficient description of “genocide” and (2) that the

concept “genocide” itself comprises several distinct

dimension A specifiable aspect of a concept. “Reli- phenomena. Let’s look at the process they went

giosity,” for example, might be specified in terms of through to come to this conclusion.

a belief dimension, a ritual dimension, a devotional

When Daniel Chirot and Jennifer Edwards

dimension, a knowledge dimension, and so forth.

attempted to define the concept of “genocide,”

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 170 11/18/11 5:24 PM

Conceptualization ■ 171

they found existing assumptions were not precise worries that the growing Albanian population

enough for their purposes: of Kosovo was gaining political strength

through numbers. Similarly, the Hutu attempt

The United Nations originally defined it as

to eradicate the Tutsis of Rwanda grew out

an attempt to destroy “in whole or in part, a

of a fear that returning Tutsi refugees would

national, ethnic, racial, or religious group.” If

seize control of the country. Often intergroup

genocide is distinct from other types of vio-

fears such as these grow out of long histories of

lence, it requires its own unique explanation.

atrocities, often inflicted in both directions.

(2003: 14)

4. Purification: The Nazi Holocaust, probably the

Notice the final comment in this excerpt, as it most publicized case of genocide, was intended

provides an important insight into why research- as a purification of the “Aryan race.” While

ers are so careful in specifying the concepts they Jews were the main target, gypsies, homosexu-

study. If genocide, such as the Holocaust, were als, and many other groups were also included.

simply another example of violence, like assaults Other examples include the Indonesian witch-

and homicides, then what we know about violence hunt against Communists in 1965–1966 and

in general might explain genocide. If it differs from the attempt to eradicate all non-Khmer Cam-

other forms of violence, then we may need a differ- bodians under Pol Pot in the 1970s.

ent explanation for it. So, the researchers began by

No single theory of genocide could explain these

suggesting that “genocide” was a concept distinct

various forms of mayhem. Indeed, this act of con-

from “violence” for their purposes.

ceptualization suggests four distinct phenomena,

Then, as Chirot and Edwards examined histori-

each needing a different set of explanations.

cal instances of genocide, they began concluding

Specifying the different dimensions of a con-

that the motivations for launching genocidal may-

cept often paves the way for a more sophisticated

hem differed sufficiently to represent four distinct

understanding of what we’re studying. We might

phenomena that were all called “genocide” (2003:

observe, for example, that women are more com-

15–18).

passionate in terms of feelings, and men more

1. Convenience: Sometimes the attempt to eradi- so in terms of actions—or vice versa. Whichever

cate a group of people serves a function for the turned out to be the case, we would not be able to

eradicators, such as Julius Caesar’s attempt to say whether men or women are really more com-

eradicate tribes defeated in battle, fearing they passionate. Our research would have shown that

would be difficult to rule. Or when gold was there is no single answer to the question. That

discovered on Cherokee land in the Southeast- alone represents an advance in our understanding

ern United States in the early nineteenth cen- of reality. To get a better feel for concepts, vari-

tury, the Cherokee were forcibly relocated to ables, and indicators, go to the General Social

Oklahoma in an event known as the “Trail of Survey codebook and explore some of the ways

Tears,” which ultimately killed as many as half the researchers have measured various concepts

of those forced to leave. (see the link at your Sociology CourseMate at

2. Revenge: When the Chinese of Nanking bravely www.cengagebrain.com).

resisted the Japanese invaders in the early

years of World War II, the conquerors felt they

had been insulted by those they regarded as

The Interchangeability

inferior beings. Tens of thousands were slaugh- of Indicators

tered in the “Rape of Nanking” in 1937–1938. There is another way that the notion of indicators

3. Fear: The ethnic cleansing that recently oc- can help us in our attempts to understand real-

curred in the former Yugoslavia was at least ity by means of “unreal” constructs. Suppose, for

partly motivated by economic competition and the moment, that you and I have compiled a list

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 171 11/18/11 5:24 PM

172 ■ Chapter 6: From Concept to Measurement

of 100 indicators of compassion and its various di- conceptualization by looking at some of the ways

mensions. Suppose further that we disagree widely social researchers provide standards, consistency,

on which indicators give the clearest evidence and commonality for the meanings of terms.

of compassion or its absence. If we pretty much

agree on some indicators, we could focus our at- Real, Nominal,

tention on those, and we would probably agree on

the answer they provided. We would then be able and Operational Definitions

to say that some people are more compassionate As we have seen, the design and execution of social

than others in some dimension. But suppose we research requires us to clear away the confusion

don’t really agree on any of the possible indicators. over concepts and reality. To this end, logicians and

Surprisingly, we can still reach an agreement on scientists have found it useful to distinguish three

whether men or women are the more compas- kinds of definitions: real, nominal, and operational.

sionate. How we do that has to do with the inter- The first of these reflects the reification of

changeability of indicators. terms. As Carl Hempel cautions,

The logic works like this. If we disagree totally

A “real” definition, according to traditional

on the value of the indicators, one solution would

logic, is not a stipulation determining the

be to study all of them. Suppose that women turn

meaning of some expression but a statement

out to be more compassionate than men on all 100

of the “essential nature” or the “essential at-

indicators—on all the indicators you favor and on

tributes” of some entity. The notion of essential

all of mine. Then we would be able to agree that

nature, however, is so vague as to render this

women are more compassionate than men, even

characterization useless for the purposes of rig-

though we still disagree on exactly what compas-

orous inquiry.

sion means in general.

(1952: 6)

The interchangeability of indicators means

that if several different indicators all represent, to In other words, trying to specify the “real” meaning

some degree, the same concept, then all of them of concepts only leads to a quagmire: It mistakes a

will behave the same way that the concept would construct for a real entity.

behave if it were real and could be observed. Thus, The specification of concepts in scientific in-

given a basic agreement about what “compas- quiry depends instead on nominal and operational

sion” is, if women are generally more compas- definitions. A nominal definition is one that is

sionate than men, we should be able to observe simply assigned to a term without any claim that

that difference by using any reasonable measure the definition represents a “real” entity. Nominal

of compassion. If, on the other hand, women are definitions are arbitrary—I could define compas-

more compassionate than men on some indica- sion as “plucking feathers off helpless birds” if I

tors but not on others, we should see if the two wanted to—but they can be more or less useful.

sets of indicators represent different dimensions of For most purposes, especially communication, that

compassion. last definition of compassion would be pretty use-

You have now seen the fundamental logic less. Most nominal definitions represent some con-

of conceptualization and measurement. The sensus, or convention, about how a particular term

discussions that follow are mainly refinements is to be used.

and extensions of what you’ve just read. Before An operational definition, as you may remem-

turning to a technical elaboration of measure- ber from Chapter 4, specifies precisely how a

ment, however, we need to fill out the picture of concept will be measured—that is, the operations

we’ll perform. An operational definition is nomi-

nal rather than real, but it has the advantage of

specification The process through which concepts

achieving maximum clarity about what a concept

are made more specific.

means in the context of a given study. In the midst

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 172 11/18/11 5:24 PM

Conceptualization ■ 173

of disagreement and confusion over what a term meaning of the text as it is anticipated. The

“really” means, we can specify a working definition closer determination of the meaning of the

for the purposes of an inquiry. Wishing to examine separate parts may eventually change the origi-

socioeconomic status (SES) in a study, for example, nally anticipated meaning of the totality, which

we may simply specify that we are going to treat again influences the meaning of the separate

SES as a combination of income and educational parts, and so on.

attainment. In this decision, we rule out other pos- (Kvale 1996: 47)

sible aspects of SES: occupational status, money in

the bank, property, lineage, lifestyle, and so forth. Consider the concept “prejudice.” Suppose you

Our findings will then be interesting to the extent needed to write a definition of the term. You might

that our definition of SES is useful for our purpose. start out thinking about racial/ethnic prejudice. At

some point you would realize you should prob-

ably allow for gender prejudice, religious prejudice,

Creating Conceptual Order antigay prejudice, and the like in your definition.

The clarification of concepts is a continuing pro- Examining each of these specific types of prejudice

cess in social research. Catherine Marshall and would affect your overall understanding of the

Gretchen Rossman (1995: 18) speak of a “concep- general concept. As your general understanding

tual funnel” through which a researcher’s changed, however, you would likely see each of

interest becomes increasingly focused. Thus, a the individual forms somewhat differently.

general interest in social activism could narrow to The continual refinement of concepts occurs

“individuals who are committed to empowerment in all social research methods. Often you will find

and social change” and further focus on discovering yourself refining the meaning of important con-

“what experiences shaped the development of fully cepts even as you write up your final report.

committed social activists.” This focusing process is Although conceptualization is a continuing

inescapably linked to the language we use. process, it is vital to address it specifically at the

In some forms of qualitative research, the beginning of any study design, especially rigorously

clarification of concepts is a key element in the structured research designs such as surveys and

collection of data. Suppose you were conducting experiments. In a survey, for example, operational-

interviews and observations of a radical political ization results in a commitment to a specific set of

group devoted to combating oppression in U.S. questionnaire items that will represent the concepts

society. Imagine how the meaning of oppression under study. Without that commitment, the study

would shift as you delved more and more deeply could not proceed.

into the members’ experiences and worldviews. Even in less-structured research methods,

For example, you might start out thinking of op- however, it’s important to begin with an initial set

pression in physical and perhaps economic terms. of anticipated meanings that can be refined during

The more you learned about the group, however, data collection and interpretation. No one seriously

the more you might appreciate the possibility of believes we can observe life with no preconcep-

psychological oppression. tions; for this reason, scientific observers must be

The same point applies even to contexts where conscious of and explicit about these conceptual

meanings might seem more fixed. In the analysis starting points.

of textual materials, for example, social researchers Let’s explore initial conceptualization the way

sometimes speak of the “hermeneutic circle,” a it applies to structured inquiries such as surveys

cyclical process of ever-deeper understanding. and experiments. Though specifying nominal

definitions focuses our observational strategy, it

The understanding of a text takes place does not allow us to observe. As a next step we

through a process in which the meaning of the must specify exactly what we are going to observe,

separate parts is determined by the global how we will do it, and what interpretations we are

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 173 11/18/11 5:24 PM

174 ■ Chapter 6: From Concept to Measurement

TABLE 62

Progression of Measurement

Measurement Step Example: Social Class

Conceptualization What are the different meanings and dimensions of the concept “social class”?

Nominal definition For our study, we will define “social class” as representing economic differences: specifically, income.

Operational definition We will measure economic differences via responses to the survey question “What was your

annual income, before taxes, last year?”

Measurements in the real world The interviewer will ask, “What was your annual income, before taxes, last year?”

going to place on various possible observations. means to specific measurements in a fully struc-

All these further specifications make up the opera- tured scientific study.

tional definition of the concept.

In the example of socioeconomic status, we

might decide to ask survey respondents two

An Example of Conceptualization:

questions, corresponding to the decision to mea- The Concept of Anomie

sure SES in terms of income and educational To bring this discussion of conceptualization in

attainment: research together, let’s look briefly at the history

1. What was your total family income during the of a specific social science concept. Researchers

past 12 months? studying urban riots are often interested in the part

played by feelings of powerlessness. Social scientists

2. What is the highest level of school you

sometimes use the word anomie in this context.

completed?

This term was first introduced into social science by

To organize our data, we’d probably want Emile Durkheim, the great French sociologist, in

to specify a system for categorizing the answers his classic 1897 study, Suicide.

people give us. For income, we might use catego- Using only government publications on

ries such as “under $5,000,” “$5,000 to $10,000,” suicide rates in different regions and countries,

and so on. Educational attainment might be simi- Durkheim produced a work of analytic genius.

larly grouped in categories: less than high school, To determine the effects of religion on suicide,

high school, college, graduate degree. Finally, we he compared the suicide rates of predominantly

would specify the way a person’s responses to these Protestant countries with those of predominantly

two questions would be combined in creating a Catholic ones, Protestant regions of Catholic coun-

measure of SES. tries with Catholic regions of Protestant countries,

In this way we would create a working and and so forth. To determine the possible effects of

workable definition of SES. Although others might the weather, he compared suicide rates in north-

disagree with our conceptualization and operation- ern and southern countries and regions, and he

alization, the definition would have one essential examined the different suicide rates across the

scientific virtue: It would be absolutely specific and months and seasons of the year. Thus, he could

unambiguous. Even if someone disagreed with draw conclusions about a supremely individualistic

our definition, that person would have a good idea and personal act without having any data about

how to interpret our research results, because what the individuals engaging in it.

we meant by SES—reflected in our analyses and At a more general level, Durkheim suggested

conclusions—would be precise and clear. that suicide also reflects the extent to which a

Table 6-2 shows the progression of measure- society’s agreements are clear and stable. Noting

ment steps from our vague sense of what a term that times of social upheaval and change often

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 174 11/18/11 5:24 PM

Conceptualization ■ 175

present individuals with grave uncertainties about Powell went on to suggest there were two dis-

what is expected of them, Durkheim suggested tinct kinds of anomia and to examine how the two

that such uncertainties cause confusion, anxiety, rose out of different occupational experiences to re-

and even self-destruction. To describe this societal sult at times in suicide. In his study, however, Powell

condition of normlessness, Durkheim chose the did not measure anomia per se; he studied the re-

term anomie. Durkheim did not make this word up. lationship between suicide and occupation, making

Used in both German and French, it literally meant inferences about the two kinds of anomia. Thus, the

“without law.” The English term anomy had been study did not provide an operational definition of

used for at least three centuries before Durkheim to anomia, only a further conceptualization.

mean disregard for divine law. However, Durkheim Although many researchers have offered oper-

created the social science concept of anomie. ational definitions of anomia, one name stands out

In the years that have followed the publica- over all. Two years before Powell’s article appeared,

tion of Suicide, social scientists have found anomie Leo Srole (1956) published a set of questionnaire

a useful concept, and many have expanded on items that he said provided a good measure of

Durkheim’s use. Robert Merton, in a classic article anomia as experienced by individuals. It consists of

entitled “Social Structure and Anomie” (1938), five statements that subjects were asked to agree or

concluded that anomie results from a disparity be- disagree with:

tween the goals and means prescribed by a society.

Monetary success, for example, is a widely shared 1. In spite of what some people say, the lot of

goal in our society, yet not all individuals have the the average man is getting worse.

resources to achieve it through acceptable means. 2. It’s hardly fair to bring children into the

An emphasis on the goal itself, Merton suggested, world with the way things look for the

produces normlessness, because those denied the future.

traditional avenues to wealth go about getting 3. Nowadays a person has to live pretty much

it through illegitimate means. Merton’s discussion, for today and let tomorrow take care of itself.

then, could be considered a further conceptualiza- 4. These days a person doesn’t really know

tion of the concept of anomie. who he can count on.

Although Durkheim originally used the con- 5. There’s little use writing to public officials

cept of anomie as a characteristic of societies, as did because they aren’t really interested in the

Merton after him, other social scientists have used problems of the average man.

it to describe individuals. To clarify this distinction, (1956: 713)

some scholars have chosen to use anomie in refer-

ence to its original, societal meaning and to use the In the half-century following its publication,

term anomia in reference to the individual charac- the Srole scale has become a research staple for

teristic. In a given society, then, some individuals ex- social scientists. You’ll likely find this particular

perience anomia, and others do not. Elwin Powell, operationalization of anomia used in many of the

writing 20 years after Merton, provided the follow- research projects reported in academic journals.

ing conceptualization of anomia (though using the This abbreviated history of anomie and anomia

term anomie) as a characteristic of individuals: as social science concepts illustrates several points.

First, it’s a good example of the process through

When the ends of action become contradic- which general concepts become operationalized

tory, inaccessible or insignificant, a condition of measurements. This is not to say that the issue of

anomie arises. Characterized by a general loss how to operationalize anomie/anomia has been

of orientation and accompanied by feelings of resolved once and for all. Scholars will surely con-

“emptiness” and apathy, anomie can be simply tinue to reconceptualize and reoperationalize these

conceived as meaninglessness. concepts for years to come, continually seeking

(1958: 132) more-useful measures.

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 175 11/18/11 5:24 PM

176 ■ Chapter 6: From Concept to Measurement

The Srole scale illustrates another important of why this is so (we’ll discuss this point more fully

point. Letting conceptualization and operationaliza- in Part 4).

tion be open-ended does not necessarily produce It’s easy to see the importance of clear and

anarchy and chaos, as you might expect. Order precise definitions for descriptive research. If we

often emerges. For one thing, although we could want to describe and report the unemployment

define anomia any way we chose—in terms of, rate in a city, our definition of being unemployed

say, shoe size—we’re likely to define it in ways not is obviously critical. That definition will depend on

too different from other people’s mental images. If our definition of another term: the labor force. If

you were to use a really offbeat definition, people it seems patently absurd to regard a three-year-old

would probably ignore you. child as being unemployed, it is because such a

A second source of order is that, as researchers child is not considered a member of the labor force.

discover the utility of a particular conceptualization Thus, we might follow the U.S. Census Bureau’s

and operationalization of a concept, they’re likely convention and exclude all people under 14 years

to adopt it, which leads to standardized definitions of age from the labor force.

of concepts. Besides the Srole scale, examples This convention alone, however, would not

include IQ tests and a host of demographic and give us a satisfactory definition, because it would

economic measures developed by the U.S. Census count as unemployed such people as high school

Bureau. Using such established measures has two students, the retired, the disabled, and homemak-

advantages: They have been extensively pretested ers. We might follow the census convention further

and debugged, and studies using the same scales by defining the labor force as “all persons 14 years

can be compared. If you and I do separate stud- of age and over who are employed, looking for

ies of two different groups and use the Srole scale, work, or waiting to be called back to a job from

we can compare our two groups on the basis of which they have been laid off or furloughed.” If a

anomia. student, homemaker, or retired person is not look-

Social scientists, then, can measure anything ing for work, such a person would not be included

that’s real; through conceptualization and opera- in the labor force. Unemployed people, then,

tionalization, they can even do a pretty good job would be those members of the labor force, as

of measuring things that aren’t. Granting that such defined, who are not employed.

concepts as socioeconomic status, prejudice, com- But what does “looking for work” mean? Must

passion, and anomia aren’t ultimately real, social a person register with the state employment service

scientists can create order in handling them. It is or go from door to door asking for employment?

an order based on utility, however, not on ultimate Or would it be sufficient to want a job or be open

truth. to an offer of employment? Conventionally, “look-

ing for work” is defined operationally as saying yes

in response to an interviewer’s asking “Have you

Definitions in Descriptive been looking for a job during the past seven days?”

and Explanatory Studies (Seven days is the period most often specified, but

for some research purposes it might make more

As you’ll recall from Chapter 4, two general pur- sense to shorten or lengthen it.)

poses of research are description and explanation. As you can see, the conclusion of a descrip-

The distinction between them has important impli- tive study about the unemployment rate depends

cations for definition and measurement. If it seems directly on how each issue of definition is resolved.

that description is simpler than explanation, you Increasing the period during which people are

may be surprised to learn that definitions are more counted as looking for work would add more

problematic for descriptive research than for ex- unemployed people to the labor force as defined,

planatory research. Before we turn to other aspects thereby increasing the reported unemployment

of measurement, you’ll need a basic understanding rate. If we follow another convention and speak of

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 176 11/18/11 5:24 PM

Operationalization Choices ■ 177

the civilian labor force and the civilian unemploy- is best? As we saw in the discussion of indicators,

ment rate, we’re excluding military personnel; that, this is not necessarily an insurmountable obstacle

too, increases the reported unemployment rate, to our research. Suppose we found old people to

because military personnel would be employed— be more conservative than young people in terms

by definition. Thus, the descriptive statement that of all 25 definitions. Clearly, the exact definition

the unemployment rate in a city is 3 percent, or wouldn’t matter much. We would conclude that old

9 percent, or whatever it might be, depends directly people are generally more conservative than young

on the operational definitions used. people—even though we couldn’t agree about

This example is relatively clear because there exactly what conservative means.

are several accepted conventions relating to the In practice, explanatory research seldom results

labor force and unemployment. Now, consider how in findings quite as unambiguous as this example

difficult it would be to get agreement about the suggests; nonetheless, the general pattern is quite

definitions you would need in order to say, “Forty- common in actual research. There are consistent

five percent of the students at this institution are patterns of relationships in human social life that

politically conservative.” Like the unemployment result in consistent research findings. However,

rate, this percentage would depend directly on the such consistency does not appear in a descriptive

definition of what is being measured—in this case, situation. Changing definitions almost inevitably

political conservatism. A different definition might results in different descriptive conclusions. The

result in the conclusion “Five percent of the stu- Tips and Tools feature, “The Importance of Variable

dent body are politically conservative.” Names,” explores this issue in connection with the

What percentage of the population do you sup- variable citizen participation.

pose is “disabled”? That’s the question Lars Gronvik

asked in Sweden. He analyzed several databases

that encompassed four different definitions or mea-

sures of disablility in Swedish society. One study

Operationalization Choices

asked people if they had hearing, seeing, walking, In discussing conceptualization, I frequently have

or other functional problems. Two other measures referred to operationalization, for the two are

were based on whether people received one of two intimately linked. To recap: Conceptualization is

forms of government disability support. Another the refinement and specification of abstract con-

study asked people whether they believed they cepts, and operationalization is the development of

were disabled. specific research procedures (operations) that will

The four measures indicated different popula- result in empirical observations representing those

tion totals for those citizens defined as “disabled,” concepts in the real world.

and each measure produced different demographic As with the methods of data collection, social

profiles that included variables such as sex, age, researchers have a variety of choices when opera-

education, living arrangement, education, and tionalizing a concept. Although the several choices

labor-force participation. As you can see, it is im- are intimately interconnected, I’ve separated them

possible to answer a descriptive question such as for the sake of discussion. Realize, though, that

this without specifying the meaning of terms. operationalization does not proceed through a

Ironically, definitions are less problematic in the systematic checklist.

case of explanatory research. Let’s suppose we’re

interested in explaining political conservatism. Why

are some people conservative and others not? More Range of Variation

specifically, let’s suppose we’re interested in whether In operationalizing any concept, researchers must

conservatism increases with age. What if you and be clear about the range of variation that interests

I have 25 different operational definitions of con- them. The question is, to what extent are they will-

servative, and we can’t agree on which definition ing to combine attributes in fairly gross categories?

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 177 11/18/11 5:24 PM

178 ■ Chapter 6: From Concept to Measurement

Tips and Tools

The Importance of Variable Names local government meetings; another might maintain a record of the

Patricia Fisher different topics addressed by private citizens at similar meetings;

Graduate School of Planning, University of Tennessee while a third might record the number of local government meeting

attendees, letters and phone calls received by the mayor and other

Operationalization is one of those things that’s easier said than done. It

public officials, and meetings held by special interest groups during

is quite simple to explain to someone the purpose and importance of

a particular time period. As skilled researchers, we can readily see

operational definitions for variables, and even to describe how operation-

that each planner would be measuring (in a very simplistic fashion)

alization typically takes place. However, until you’ve tried to operationalize

a different dimension of citizen participation: extent of citizen par-

a rather complex variable, you may not appreciate some of the subtle

ticipation, issues prompting citizen participation, and form of citizen

difficulties involved. Of considerable importance to the operationalization

participation. Therefore, the original naming of our variable, citizen

effort is the particular name that you have chosen for a variable. Let’s

participation, which was quite satisfactory from a conceptual point of

consider an example from the field of Urban Planning.

view, proved inadequate for purposes of operationalization.

A variable of interest to planners is citizen participation. Planners

The precise and exact naming of variables is important in

are convinced that participation in the planning process by citizens is

research. It is both essential to and a result of good operationaliza-

important to the success of plan implementation. Citizen participation

tion. Variable names quite often evolve from an iterative process of

is an aid to planners’ understanding of the real and perceived needs of

forming a conceptual definition, then an operational definition, then

a community, and such involvement by citizens tends to enhance their

renaming the concept to better match what can or will be measured.

cooperation with and support for planning efforts. Although many differ-

This looping process continues (our example illustrates only one

ent conceptual definitions might be offered by different planners, there

iteration), resulting in a gradual refinement of the variable name and

would be little misunderstanding over what is meant by citizen partici-

its measurement until a reasonable fit is obtained. Sometimes the

pation. The name of the variable seems adequate.

concept of the variable that you end up with is a bit different from

However, if we ask different planners to provide very simple op-

the original one that you started with, but at least you are measur-

erational measures for citizen participation, we are likely to find a variety

ing what you are talking about, if only because you are talking about

among their responses that does generate confusion. One planner might

what you are measuring!

keep a tally of attendance by private citizens at city commission and other

Let’s suppose you want to measure people’s the general U.S. population, a bottom category of

incomes in a study by collecting the information $5,000 or less usually works fine.

from either records or interviews. The highest In studies of attitudes and orientations, the

annual incomes people receive run into the mil- question of range of variation has another dimen-

lions of dollars, but not many people earn that sion. Unless you’re careful, you may end up mea-

much. Unless you’re studying the very rich, it suring only half an attitude without really meaning

probably won’t add much to your study to keep to. Here’s an example of what I mean.

track of extremely high categories. Depending on Suppose you’re interested in people’s attitudes

whom you study, you’ll probably want to estab- toward expanding the use of nuclear power gen-

lish a highest income category with a much lower erators. You’d anticipate that some people consider

floor—maybe $100,000 or more. Although this nuclear power the greatest thing since the wheel,

decision will lead you to throw together people whereas other people have absolutely no inter-

who earn a trillion dollars a year with paupers est in it. Given that anticipation, it would seem to

earning a mere $100,000, they’ll survive it, and make sense to ask people how much they favor

that mixing probably won’t hurt your research expanding the use of nuclear energy and to give

any, either. The same decision faces you at the them answer categories ranging from “Favor it very

other end of the income spectrum. In studies of much” to “Don’t favor it at all.”

Copyright 2012 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

94_ch06.indd 178 11/18/11 5:24 PM

Operationalization Choices ■ 179

This operationalization, however, conceals half a group labeled 10 to 19 years old? Don’t answer

the attitudinal spectrum regarding nuclear energy. too quickly. If you wanted to study rates of voter

Many people have feelings that go beyond simply registration and participation, you’d definitely want

not favoring it: They are, with greater or lesser to know whether the people you studied were

degrees of intensity, actively opposed to it. In this old enough to vote. In general, if you’re going to

instance, there is considerable variation on the left measure age, you must look at the purpose and

side of zero. Some oppose it a little, some quite a procedures of your study and decide whether fine

bit, and others a great deal. To measure the full or gross differences in age are important to you.

range of variation, then, you’d want to operation- In a survey, you’ll need to make these decisions in

alize attitudes toward nuclear energy with a range order to design an appropriate questionnaire. In

from favoring it very much, through no feelings the case of in-depth interviews, these decisions will

one way or the other, to opposing it very much. condition the extent to which you probe for details.

This consideration applies to many of the vari- The same thing applies to other variables. If

ables social scientists study. Virtually any public you measure political affiliation, will it matter to your

issue involves both support and opposition, each inquiry whether a person is a conservative Democrat

in varying degrees. In measuring religiosity, people rather than a liberal Democrat, or will it be sufficient

are not just more or less religious; some are posi- to know the party? In measuring religious affiliation,

tively antireligious. Political orientations range is it enough to know that a person is Protestant, or

from very liberal to very conservative, and depend- do you need to know the denomination? Do you

ing on the people you’re studying, you may want simply need to know if a person is married, or will

to allow for radicals on one or both ends. it make a difference to know if he or she has never

The point is not that you must measure the full married or is separated, widowed, or divorced?

range of variation in every case. You should, how- There is, of course, no general answer to such

ever, consider whether you need to, given your questions. The answers come out of the purpose of

particular research purpose. If the difference be- a given study, or why we are making a particular

tween not religious and antireligious isn’t relevant measurement. I can give you a useful guideline,

to your research, forget it. Someone has defined though. Whenever you’re not sure how much de-

pragmatism as “any difference that makes no tail to pursue in a measurement, get too much detail

difference is no difference.” Be pragmatic. rather than too little. When a subject in an in-depth

Finally, decisions on the range of variation interview volunteers that she is 37 years old, record

should be governed by the expected distribution “37” in your notes, not “in her thirties.” When

of attributes among the subjects of the study. In you’re analyzing the data, you can always combine