Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Banham and 'Otherness': Reyner Banham (1922-1988) and His Quest For An Architecture Autre

Banham and 'Otherness': Reyner Banham (1922-1988) and His Quest For An Architecture Autre

Uploaded by

Juying JiaoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Banham and 'Otherness': Reyner Banham (1922-1988) and His Quest For An Architecture Autre

Banham and 'Otherness': Reyner Banham (1922-1988) and His Quest For An Architecture Autre

Uploaded by

Juying JiaoCopyright:

Available Formats

Banham and 'Otherness': Reyner Banham (1922-1988) and His Quest for an Architecture

Autre

Author(s): Nigel Whiteley

Source: Architectural History , 1990, Vol. 33 (1990), pp. 188-221

Published by: SAHGB Publications Limited

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1568555

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Architectural History

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Banham and 'Otherness'

Reyner Banham (I922-I988) and his quest for an

architecture autre

by NIGEL WHITELEY

With the death of Peter Reyner Banham in March 1988 at the age of 66, the architectural

world lost one of its most distinguished historians and irrepressible critics. His career,

by normal academic standards, was wide-ranging and helps to explain his unconven-

tional and, at times, idiosyncratic approach to architecture. During the war Banham

very successfully studied at the Bristol Aeroplane Company's engine division, thereby

acquiring a thorough grounding in the theory and practice of mechanical engineering.

An evident enthusiasm for technology was combined with a rigorous training in art

history under Nikolaus Pevsner at the Courtauld Institute from where he graduated in

1952.

Banham began contributing on a regular basis to the Architectural Review in 1952 (on

whose editorial board sat Pevsner), eventually joining it as an assistant editor in 1959-

the time he successfully completed his controversial doctorate on the architecture and

ideas of the Modern Movement, again under Pevsner. Banham's first book - Theory

and Design in the First Machine Age (1960) - was substantially based on his doctorate,

and in 1964 he entered academia at the Bartlett School of Architecture in University

College, London, where he became professor in 1969. Two other major texts - The

New Brutalism (1966) and The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment (1969) -

date from this period. In 1976 he moved to the United States, taking up professional

appointments at the universities of Buffalo and California. In I987 he was appointed to

the apex of architectural history chairs - Professor of Architectural Theory and

History at New York University - but tragically died before he was able to take up the

post.

The early and decisive combination of technology, journalism and scholarship

accounts not only for Banham's robust, committed yet disciplined and incisive style of

writing, but also his keen interest in varied and various cultural artefacts from buildings

to cars. For, unlike most writers about the arts, Banham was equally at home whether

discussing conventional 'high art' architecture, the styling of household appliances, or

the latest science fiction puppet series on television. He contributed to a cross-section of

journals and magazines, not all of which were architectural. From 1958 until the late

1970s, for example, he wrote regularly for (first) New Statesman and (later) New Society

about architecture, technology, and popular culture.

However all-encompassing his subjects, there was an underlying commonality in

Banham's writings that could be traced to his quest to find a dynamic and persuasive

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BANHAM AND OTHERNESS I89

alternative to the conventional thinking and operational lores that, in

most contemporary architecture and design. This quest was at its m

1950s and it is the subject of this essay. During this decade Banham often

idea of an architecture autre: where did the idea come from? what did he

did he seek it? and what influence did it exert on his subsequent crit

Banham first used the term une architecture autre in an article about 'The New

Brutalism' which appeared in The Architectural Review in December I955.1 The term

was supposed to be analogous to the concept of un art autre, the subject and title of a

book written by the French art critic Michel Tapie and published in Paris in I952.2

What Tapie had had in mind in employing the term were the post-war anti-formal an

anti-classical tendencies that could be observed in both America and Europe. A

significant number of painters in the aftermath of the war felt unable or unwilling t

return to the confident and often elegant formal coherence that characterized the wor

of Modernist 'masters' such as Matisse and Mondrian. The supposedly 'timeles

qualities of great art - the relational and hierarchic ordering of colours, shapes and

spaces, the disinterested and 'objective' control of the artist, the heroic content

seemed entirely inappropriate to a society which, at least in Europe, had been

physically and psychologically devastated by war. In America, some artists reacted

against the post-war materialism, complacency, and the enthusiasm for the 'atomic

age' which, they felt, would inevitably lead to the holocaust. The attitude amongst th

tendency of artists was one of urgency and an almost brutal directness that rejecte

previous hopes and solutions.

There were three main tributaries which made up art autre. The first - the one

pre-war legacy - was the process-orientated Surrealism that made use of automatic

and semi-automatic techniques which, its proponents believed, extracted the uninhibi

ted and primordial subconscious. One of the chief characteristics of this so-calle

'absolute' Surrealism was the primacy of process over form and formalist control, o

unfinishedness over the resolvedness associated with 'great' art. For Arshile Gorky,

Surrealist-influenced artist working in America and greatly influential on the post-wa

generation of American painters, the value of process and unfinishedness was i

vitality:

When something is finished, that means it's dead doesn't it? I believe in everlastingness. I never

finish a painting - I just stop working on it for a while. I like painting because it's something I

never come to the end of... The thing to do is always to keep starting to paint, never finishing

painting.3

This almost metaphysical attitude to unfinishedness was eagerly imbibed by the 'New

American Painters' of the post-war years and can be clearly detected in the work and

statements of a major artist such as de Kooning whose energetic and gutsy work of the

late I940S and early I950s was a rebuke to the sure-footed control of European painters:

'... French artists have some "touch" in making an object. They have a particular

something that makes them look like a "finished" painting. They have a touch which I

am glad not to have'.4 The European Modernists' desire to impose order was also

foreign to de Kooning: 'The attitude that nature is chaotic and that the artist puts order

into it is a very absurd point of view'.5 Flux was an acceptable - even desirable - state

of being.

13

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I90o ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY 33: I990

^ - _ - 'I L " r. *? . v . -.

Fig. I Jackson Pollock, Europe, 1950 duco on canvas

Pollock's contribution to art autre was his non-relational, non-hierarchic

eschewed conventions offigure against ground and ordered points offocus

The second art autre tributary was also to be found in

convincingly in the work ofJackson Pollock (Fig. i). Pollock

the process of orientation of Absolute Surrealism and the n

flux. Echoing Gorky, Pollock was attracted to the notion th

and no end'.6 Yet what makes Pollock a more radical painte

Kooning is not his 'splash and dribble' technique but his re

relationship in favour of an all-over, non-hierarchic c

contrasts or contrived points of focus. This stage of devel

1940S in works like Full Fathom Five (1947), and came to its

as Autumn Rhythm and One, both of 1950. To a Modern art

canons of formal order, balance and qualitative judgeme

bewildering and even subversive. Indeed, even for a wo

(aged 28 in Ig50), Pollock's work was

... almost incomprehensible to European eyes. Yet it left an inde

and when it seemed to be time to try and overthrow the classic

dominance of France in European intellectual life) then Pollock

and became a sort of patron saint of anti-art even before his se

death (which occurred in I956).7

Pollock's major contribution to art autre was his non-relatio

longer employed a hierarchic ordering of discrete parts. T

have a profound influence on Banham's nascent architecture

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BANHAM AND OTHERNESS I9I

The third major component of art autre was the art brut championed by

a 'raw art' untainted by polite conventions of civilized refinement.

was nothing to do with taste, classical harmony or skill, but a

primordial impulse that existed in everyone and which should b

directly and spontaneously. Dubuffet looked towards the work of psy

the 'mad and the criminal' for this true art uncontaminated by artists an

He described graffiti as '. . . our state of civilisation, our primitive a

wall gives its voice to that part of man which, without it would

silence'. The wall was a '. . . reminder of a primitive existence' and '

the most faithful mirrors'.8 Dubuffet opened his collection of art bru

Only 63 of the 200 works in the first exhibition of art brut in 1949 were b

was justified by Dubuffet on the grounds that 'Art is not the exclusiv

initiates. It is a common asset, barred to no one. You enter without

without even knowing it, led by instinct'.9

Dubuffet's own work exemplified the art brut anti-aesthetic (Fig.

various materials including mud, sand, glue and asphalt revealed appa

scratches and blemishes:

I've found myself suggesting certain materials, not so much those with a 'noble' reputation, like

marble or exotic woods, but instead very ordinary ones with no value at all like coal, asphalt or

even mud ... in the name of what ... does man bedeck himself with necklasses of shells, and not

spiders webs, with foxs' furs and not their guts, in the name of what I'd like to know? Mud,

rubbish and dirt are man's companions all his life; shouldn't they be precious to him, and isn't

one doing man a service to remind him of their beauty?10

Dubuffet's reference to 'beauty' was significant, because it underlines that he was

certainly not antithetical to art itself - as unsympathetic critics claimed - but was

instead seeking a new beauty which owed nothing to classical aesthetics and accepted

taste. This was a state of affairs which Banham's architecture autre aesthetic was to

parallel.

Three aspects of Dubuffet's work helped to shape the emerging art autre. First was

Dubuffet's insistence that creation is not individualistic, but universal: '... there is only

a single man in the universe, whose name is Man -and if all painters signed their works

with this name: "Picture painted by Man" see how pointless any questioning would

appear'.11 But here was a universality that, although timeless, was of an entirely

different order from the aesthetically timeless and permanent works upheld by Modern-

ist artists and critics. Dubuffet's universality referred to the primordial urge to make a

mark as an assertion of existence in a hostile and unforgiving world. The resulting form

- the second important aspect of art brut- was, by traditional artistic standards, brutal

and ugly in its uncompromising anti-formalism. Third - and in some ways the most

important aspect for later architectural thought, especially the New Brutalism - was

Dubuffet's attitude to materials which was inclusive and non-hierarchical. No material

was rejected out-of-hand because of a lowly status. Each and every material was as

good as any other: each had its own characteristics, however conventionally unappeal-

ing, and must be used 'as found'.

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I92 ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY 33: I990

Fig. 2 Jean Dubuffet, Gymnosophy, 1950, oil on canvas

Dubuffet's primitive and crude paintings outraged critics and public alike in the early 195os.

Spontaneity, directness, rawness and 'authenticity' mattered more to Dubuffet than sophistication,

craftsmanship and refinement

An art autre then, at its most dynamic and radical, brought together flux a

unfinishedness as a state of being; non-hierarchic and non-relational anti-formalism

primordial universality; and a direct, anti-elegant, even ugly use of forms, mater

and colours. Art autre was not a new formalism, and certainly not a new style, but a new

and tough attitude to creating that eschewed high-minded and classical notions of A

Banham's understanding of art autre and its implications, as we shall see, was sou

For any misinterpretations that may have arisen were dispelled by direct contact w

the one British artist whose work during the I95os could most convincingly

described as art autre: Eduardo Paolozzi. On graduating from the Slade in 19

Paolozzi had moved to Paris for more than two years. During his stay there he me

many artists including Brancusi, Giacometti, Arp, Tristan Tzara and Dubuffet. Ac

to Mary Reynolds' large collection of Dada and Surrealist documents, and visits to

Musee de l'Homme and Dubuffet's collection of art brut helped to immerse Paolozz

modes of anti-art and art autre (Fig. 3).

Banham met Paolozzi when the latter gave his celebrated 'Bunk' slideshow (m

accurately, epidiascope-show) at the first meeting of the newly-formed Independe

Group in 1952.12 Although the subject matter of the slideshow - advertiseme

science fiction illustrations, robots, food, consumer goods and technological hardwa

most of it from American popular magazines - was proto-Pop, the manner in whi

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BANHAM AND OTHERNESS I93

Fig. 3 Eduardo Paolozzi, Head, 1953,

regard for logic, development, continuity, scale or meaning. The anti-art brut

character is certainly consistent with Paolozzi's sculpture of the 195os m

changed from the Giacometti- and Picasso-influenced work of Surrealism a

rough-hewn and primitive Dubuffet-inspired heads and figures ofuened

The Independent Group was a source of great stimulation for Banham. Its

the images were projected - one image speedily after the other

commentary or explanation - had a marked anti-art character. P

rough-hewn and primitive Dubuffet-inspired heads and figures

history is assured by its cont, coributinuity, scale or ensuing interest in A

over-emphasize the Pop elements of his graphic work at the expense

culture and mass media which led on to British Pop art. But 'o' culture

changed from the usiacometti- and Picassinterestsfluenced work of the group. Equally importa

history is assured by its contribution to the ensuing interest in American popular

with technology and art autre outlookwhich, in Banham's case, provedmmon errorqually influassessmential.s of Paolozzi's work.

culture and mass media which led on to British Pop art. But 'pop' culture was only one

Indeed, the first season of Independent Group seminars ource of great stimulation for2, devised by Banham. Its place in art

of the enthusiasms and interests of the group. Equally important were the concerns

with technology and art autre which, in Banham's case, proved equally influential.

Indeed, the first season of Independent Group seminars in I952, devised by Banham,

centred on science and technology: Banham's contribution was a talk on the machine

aesthetic of the Modern Movement. It was not until the second (and final) series of

seminars in 1954-55 that popular culture became one of the dominant themes. In that

series Banham talked about the symbolism of Detroit car styling; Alison and Peter

Smithson discussed American advertisements and architecture; and Richard Hamilton

analyzed the styling of consumer goods. However, of equal importance in the series,

convened by Lawrence Alloway andJohn McHale, were the themes of recent fine art,

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I94 ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY 33: I990

and communication theories. Art autre remained an undercurrent, sometimes surfac

in a talk such as 'Were the Dadaists Non-Aristotelean?', posed by Alloway and Edwa

Wright.

To the extent that a single Independent Group mentality existed, it could be argued

that it was broadly pro-art autre and, as far as high culture was concerned, anti-art. The

term 'anti-art' and its two different usages must, however, be clearly understood.

'Anti-art' can be used to describe the type of Dada work which subverted nothing less

than the whole institution and activity of art - Duchamp's moustache painted on a

reproduction of the Mona Lisa exemplifies this approach; or it can refer to work which

subverts not art itself, but a particular aesthetic and set of values - in mid century that

aesthetic was classical with its connotations of timelessness, sophistication and cultural

prestige.

The choice of the name Independent Group13 was itself significant because those

associated with the group sought to distance themselves and be independent from the

concept of 'High Art' as it was expressed by Herbert Read, then president of the

Institute of Contemporary Art (where the Independent Group met). For Banham and

the others, Read personified a serious and high-minded approach which, like the young

post-war artists and intellectuals in revolt in Europe and America, they believed to be

outdated and elitist. Read represented both a 'High Art' attitude and the British art

establishment which was seen as increasingly powerful and complacent. Hamilton

recalls that the '. . . one binding spirit amongst the people at the Independent Group . ..

was a distaste for Herbert Read's attitudes'.14 In Banham's opinion, his generation had

grown up under the 'marble shadow' of Read's classical aesthetics and were vehem-

ently beginning to reject it in the early I950s:

We were against direct carving, pure form, truth, beauty and all that ... what we favoured was

motion studies. We also favoured rough surfaces, human images, space, machinery, ignoble

materials and what we termed non-art (there was a project to bury Sir Herbert under a book

entitled Non-Art Not Now). 15

This was an anti-art antidote to Read's Art Now (1933) which had been revised in 1948.

Banham was rejecting the High Modernist values of universality, permanence and

disinterestedness and seeking instead a dynamic and genuine alternative: an 'anti-art'

that was other.

As we will see, there were four areas in which Banham linked art autre and

architecture: a revision of architectural Modernism; technology; popular culture; and

the New Brutalism. At the time of the Independent Group meetings, the most

promising seemed the New Brutalism because its chief practitioners, Alison and Peter

Smithson, were both members of the group and seemed highly sympathetic to the

notion of an art autre. In 1953, the year between the two Independent Group series, the

Smithsons had been co-organizers with Paolozzi and the experimental photographer

Nigel Henderson of the exhibition Parallel ofLife and Art, held at the ICA. Parallel of Life

and Art contained 122 large, grainy-textured photographs of machines, slow motion

studies, X-rays, materials under stress, primitive architecture, children's art, vegetable

anatomy and other miscellaneous images - the only 'high art' image permitted was a

photograph of Pollock working on painting - which flouted conventional standards

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BANHAM AND OTHERNESS 195

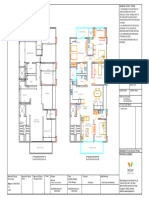

Fig. 4 Parallel of Life and Art exhibition, ICA, London, 1953

The criteria of'imagability' and emotional impact were emphasized by the aformal, env

layout which undermined the spectator's supposedly disinterested and detached contempl

of formal order, beauty and meaning. The criterion of selection was 'im

emotional impact. The photographs - many large in size and ignorin

hung environmentally from walls, ceiling and floor (Fig. 4). Organiz

duously non-hierarchic and, akin to art autre, anti-formal. Banham adj

exhibition undermined '. .. humanistic conventions of beauty in order

violence, distortion, obscurity and a certain amount of"humeur noir" .

subversive innovation whose importance was not missed'.16 While most v

have agreed with Banham's description of the exhibition, they would h

negative, not positive terms. Indeed, many critics and architects, Banh

complained of the deliberate flouting of the traditional concepts of

beauty, of a cult of ugliness, and "denying the spiritual in Man"'.17

Parallel of Life and Art revealed that the Smithsons shared Paolo

sympathies. They were well-versed in art autre tendencies - they

Pollock's work in I950 at the Venice Biennale - and Banham's hope

would develop a genuine architecture autre. For a while it seemed that it mig

the guise of the New Brutalism.

In some ways there were strong parallels in the reaction to the curre

scene between the New Brutalism and art autre - the most obvious is th

transcendent classical aesthetic- but there were also striking dissimilar

art autre turned its back on Modernism as a whole, the New Brutalism sig

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I96 ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY 33: I990

to the attitudes of the Modernism of its early period. 'It is necessary to create

architecture of reality', wrote the Smithsons,

an architecture which takes as its starting point the period 19 I - of de Stijl, Dada and Cubis

... An art concerned with the natural order [original authors' italics], the poetic relationship betw

living things and environment. We wish to see towns and buildings which do not make us f

ashamed, ashamed that we cannot realise the potential of the twentieth century, ashamed th

philosophers and physicists must think us fools, and painters think us irrelevant. We live

moron-made cities. Our generation must try and produce evidence that men are at work.1

The tone of the passage recalls Dubuffet and, although the New Brutalists and art au

artists were scrutinising different sources, they were both seeking a rekindling of

primitive and direct attitudes to creation in their disciplines which, for all th

differences in chronological location, both parties believed to be essentially a-historic

The most immediate source of hostility to the New Brutalists (who, to all extent

and purposes in the early 1950s, were Alison and Peter Smithson) was the 'Ne

Empiricism' or 'New Humanist' architecture, characterized by pitched roofs, brick

rendered walls, window boxes and balconies, paintwork, and picturesque grouping.

The sources for the style were the British 'Ideal Home', Picturesque plannin

'townscape' studies (popularized by the Architectural Review after the War), recen

Swedish architecture and, at least in the case of the London County Council architec

a firm Marxist belief in social realism with its unintentionally condescending 'peopl

detailing'. The origins of the term 'The New Brutalism' - both the straightforward

and esoteric - have been examined elsewhere19 and we need here only note tha

combined, as the Smithsons pointed out, a '. .. response to the growing literary style

the Architectural Review which, at the start of the fifties, was running articles on ... the

New Empiricism, the New Sentimentality, and so on';20 reference to beton brut (r

concrete) which had been one of the most controversial features of Le Corbusie

recently finished Unite block in Marseilles, and, not least, the art brut of Dubuffet.

The term was first used in public by Peter Smithson to describe a small house proj

of 1952 for a site in Soho, London. The statement which accompanied the des

indicates an art brut aesthetic of materials asfound:

It was decided to have no finishes at all internally, the building being a combination of shelter an

environment. Bare bricks, concrete and wood ... It is our intention in this building to have t

structure exposed entirely .. 21

The belief in 'truth to materials' is part of the legacy of the aesthetico-moral tradition of

the nineteenth century that continued into the present century. Its manifestation

percolated through Modernist art and architecture, whether Henry Moore or Mies v

der Rohe, but where the New Brutalists parted company with the Modernists was

the end to which the means were put. Modernists ultimately believed that each mater

had intrinsic qualities that could be brought out by the artist so as to create beauty. T

New Brutalist attitude to materials was to present them as fact, the effect of whi

might be inelegance and even ugliness.

The occupant of such a building would certainly need to be in tune with art bru

aesthetics: inelegance and conventional ugliness would appeal to the majority o

residents as much as the Purist machine aesthetic architecture of Le Corbusier or Mi

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BANHAM AND OTHERNESS I97

:....: ...

Fig. 5 Alison and Peter Smithson, School, Hunstanton, Norfolk, 1954

The Science Room, on completion of the building, demonstrates the starkness and di

design

van der Rohe. However, to the sort of aficionado who wrote in praise of their work, the

Smithson's buildings radiated

... a feeling quite unlike the undefined, accidental quality of the romantic school, which

incorporates imitation nature effects. On the contrary, the Smithsons' houses emphasize the

intimate feeling of shelter. One is in a space that represents all space, oneself orientated to the

matter within which the house stands and out of which it is built. Every part of the house seems

in balance with the essential brutality of man.22

The commentator went on to praise the Soho house in particular as

... one of the artists' highest poetic achievements ... Everything in the interior that meets the

eye is co-ordinated - air, light, glass, the dynamic, tense horizontal planes in ceiling and floor,

create a sense of space at once definitive and infinite. Within everything contributes to the balance

of space, equilibrium embodied in greater and lesser volumes, re-establishing a sense of intimate

brutality at the very moment of participation in surrounding nature.23

The use of materials and the aesthetic ends to which they were put was the cause of

much confusion and controversy in the Smithsons' early buildings and projects.

Nowhere was this more apparent than in their best-known early works - the school at

Hunstanton in Norfolk (Fig. 5). Although the design of the building (1950) predates the

term, the school is accepted (especially by the Smithsons) as one of the key buildings of

the New Brutalism. In its use of undisguised steel and glass the building appeared to

resemble the work of Mies but, in an assessment of the school written on its completion

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I98 ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY 33: I990

in 1954, Banham argued that it was free of the '. . .formalism [present author's italics

Mies van der Rohe. This may seem a hard saying, since Mies is the obvio

comparison, but at Hunstanton every element is truly what it appears to be ..

Banham developed the point to discuss the resultant

... new aesthetic of materials, which must be valued for the surfaces they have on delivery to

site - since paint is only used where structurally or functionally unavoidable - a valuation li

that of the Dadaists, who accepted their materials 'as found', a valuation built into the Mode

Movement by Moholy-Nagy at the Bauhaus. It is this valuation of materials which has led to

appellation 'New Brutalist', but it should now be clear that this is not merely a surface aesthe

of untrimmed edges and exposed services, but a radical philosophy reaching back to the fi

conception of the building. In this sense this is probably the most truly modern building

England, fully accepting the moral code which the Modern Movement lays upon the architec

shoulders. It does not ingratiate itself with cosmetic detailing, but, like it or dislike it, dema

that we should make up our minds about it, and examine our consciences in the light of t

decision. 25

Setting aside the inconsistencies of Moholy-Nagy's use of materials - he is presum

ably referring to Moholy's kinetic sculpture rather than his more formalistic produ

design - Banham is emphasizing the 'new' or art autre attitude, not only to material

but to the building's total conception and execution. This shifts the term of referen

away from aesthetic issues to a moral one. It is not, however, to be confused with t

aesthetico-moral approach beloved by nineteenth- and twentieth-century rationali

who were convinced that their true style or aesthetic had moral authority. T

Smithsons and Banham both adopted James Stirling's dictum of'a style for the job

which implied a pragmatic and inclusive attitude to visual matters, not a preconceiv

or ideal one.26

The same was true for the plan of the building. Hunstanton's plan was essentially

symmetrical and many critics thought this showed the influence of Rudolf Wittkower

recently published Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism, and Colin Rowe'

researches into mathematics and proportion in architecture. 27 Certainly the Smithson

were aware of this recent scholarship and, equally certainly, they were influenced by i

But the influence they absorbed and applied was filtered through the anti-idealist

outlook of the New Brutalism. Classical planning - or even classical proportions

could be used in a New Brutalist building because New Brutalism was inclusive. The

quintessential change, however, was that the transcendent and idealist associations o

classicism - the metaphysical dimension in which the particular always referred to th

general - were dropped so that any classical aspect was merely another option, anothe

tool at the architect's disposal, and on a par with all others.

These distinctions between classical aesthetics and pragmatics - crucial if one is to

understand the influence of art autre on architecture in this period - seemed to hav

eluded most commentators whosejudgements were based on superficial visual charac-

teristics. They were of the same order of misunderstanding as occurred in art a decad

later when formalist aesthetics were applied to Minimal sculptures by Robert Morri

and Donald Judd. In the case of the Hunstanton school, this confused thinking led

Philip Johnson in 1954 to applaud the 'inherent elegance' of the Smithsons' desig

influenced, so Johnson thought, by Mies. He regretted that, in their succeeding work

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BANHAM AND OTHERNESS 199

* E""

^..^^ ^ a^sa^.:.:.l .... : _.... .....

Fig. : .6 Alio and Peer Smithson, Golden Lane project, 192

Fig. 6 Alison and Peter Smithson, Golden Lane project, 1952

This drawing by the Smithsons illustrates the anti-formalism of the project. Layout is determined

by the topography of the site rather than by any formal ordering or picturesque aesthetic. The

architects hoped this would lead to a 'rough poetry' absent from contemporary architecture

the Smithsons had '... turned against such formalistic and "composed" designs

towards an Adolf Loos type of Anti-Design which they call the New Brutalism

phrase which is already being picked up by the Smithsons' contemporaries to defend

atrocities) .. .'.28 By then the New Brutalism was synonymous in most critics' minds

with raw concrete and was being discussed in primarily stylistic terms. The Smithson

themselves tried to make the point that '... Brutalism has been discussed stylistically

whereas its essence is ethical'.29 The aesthetics of art brut and the concept of art autr

were passed over by all but a tiny number of informed practitioners and critics.

Whether such an uncompromising ethico-aesthetic high ground should be foisted on

the sensitive and delicate minds that daily populated the school was a moot point. Whi

the purchasers of one of the Smithsons' private houses probably knew what they wer

taking on - at least they had the alternative to buy somewhere else - this wa

obviously not so for the users or inhabitants of an architecture brut public building. Th

Smithsons' attitude was redolent of the-architect-as-moral-crusader and artistic trail-

blazer that had characterized early Modernism: the public was expected to come

terms with what could be a stark and unforgiving architecture.

The anti-formalism of the Smithsons in the I950s can best be observed in the

unsuccessful entry for the City of London's Golden Lane public housing competition o

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

200 ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY 33: 1990

I952 (Fig. 6). The New Brutalists were, according to the Smithsons, committed

being

... objective about 'reality' - the cultural objectives of society, its urges, its techniques, and so

on. Brutalism tries to face up to a mass production society, and drag a rough poetry out of the

confused and powerful forces which are at work.30

The first sentence sounds distinctly like an anti-idealist, almost amoral stance; the

second recalls Dubuffet's pronouncements about art brut. 'Reality' related to the way

that the Smithsons believed that working-class people actually lived, rather than the

way that middle-class architects thought they should live, and it formed the basis of

these two projects. Their Golden Lane project incorporated the idea of the street deck

(subsequently taken up by Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith at Sheffield) which they hoped

would facilitate a community-orientated life akin to the traditional terraced street. New

Brutalism was, its proponents believed, essentially humane and 'user friendly' albeit

based on a rather heroic and unrealistic view of working-class lifestyles which were

becoming considerably lessprimeval than the Smithsons supposed (or hoped). The deck

was also a means of circulation - albeit for pedestrians - in much the same way that a

road normally was, and it linked clusters of buildings. The anti-formalism of the

project was most clearly in evidence in the layout of the blocks which were not

arranged in any aesthetically ordered or systematic way but were sited according to the

topography of the site. Nor was this in the Picturesque tradition of 'consulting the

genius of the place' and enhancing it: the Smithsons' attitude to layout was, like their

attitude to materials, 'as found'.

The Smithsons developed their topographical approach in their Sheffield University

extension (1953) and 'Cluster City' (1957) projects which continued the rejection of the

'geometry of crushing banality' that, in their view, characterized Modernist planning

schemes.31 Cluster City's emphasis on the '... realities of the situation, with all their

contradictions and confusions'32 brings to mind Robert Venturi's influential Complex-

ity and Contradiction in Architecture which it predates by nine years. The similarity

between the two serves to remind onejust how much the anti-formalism of the 1950s

was taken up in the next decade.

Banham's first major article on the New Brutalism appeared in the Architectural

Review in December 1955. In it he discusses the Smithsons' Soho house, Hunstanton

school, Sheffield University extension and several other projects including their

competition entry for Coventry Cathedral (195I). All were illustrated. Banham is

unambiguously partisan about the New Brutalism and not only praises the Smithsons'

work, but attempts to locate the New Brutalism in the contexts of post-war,

anti-classical aesthetics, and architectural history. Non-architectural illustrations

accompanying the article include an 'all-over' painting by Pollock ('Number Seven-

teen', 1949 - a work also illustrated in Un Art Autre - but misdated by Banham as

1953); an art brut burlap piece (undated) by Albert Burri described as '... typically

Brutalist in his attitude to materials ...',33 a Paolozzi head of 1953 exhibiting

'sophisticated primitivism',34 a Magda Cordell 'anti-aesthetic human image figure',35 a

photograph of window graffiti by Nigel Henderson; and an installation shot of Parallel

of Life and Art.

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BANHAM AND OTHERNESS 20I

The chief characteristics of the New Brutalism were summarized b

formal legibility of plan; 2, clear exhibition of structure, and 3, valu

for their inherent qualities "as found"'.36 However, Banham acknow

description could also apply to non-Brutalist buildings, such as

apartments. He therefore suggested a further key ingredient: 'In the

characterises the New Brutalism in architecture as in painting is preci

itsje-'en-foutisme, its bloody-mindedness'.37 In exactly paralleling the

architecture and painting, Banham significantly disregards the soci

dimension of architecture over painting. He goes on to question wh

Yale Art Centre could be accepted into the Brutalist canon, but ultima

negative:

... the Smithsons' work [at Hunstanton] is characterised by an abstemious

the details, and much of the impact of the building comes from the inelo

consistency of such components as the stairs and handrails. By comparison,

arty ...38

Banham (unlike the users of the building) appreciated the artlessness/anti-art quality of

the Hunstanton school where 'water and electricity do not come out of unexplained

holes in the wall, but are delivered to the point of use by visible pipes and manifest

conduits'.39 Such a comment anticipates Banham's enthusiasm for 'High Tech'

architecture in the I970s and I980s.

It is clear that what Banham likes about the New Brutalism is its generally art autre

character. Of the Sheffield University project Banham wrote that its '. .. aformalism

becomes as positive a force in its composition as it does in a painting by Burri or Pollock

. ..'40 and he applauds the aformal siting of the blocks which '... stand about the site

with the same graceless memorability as martello towers or pit-head gear'.41 It is at this

juncture that Banham introduces the idea of une architecture autre:

... Sheffield remains the most consistent and extreme point reached by any Brutalists in their

search for Une Architecture Autre. It is not likely to displace Hunstanton in architectural

discussions as the prime exemplar of The New Brutalism, but it is the only building-design

which fully matches up to the threat and promise of Parallel of Life and Art.42

Banham regarded Parallel of Life and Art as the 'locus classicus'43 of the New Brutalism: a

visual and conceptual manifesto of the art autre aesthetic.

So, by late 1955, Banham had nailed his colours to the mast of une architecture autre.

He was later to detail the required qualities more systematically:

... an architecture whose vehemence transcended the norms of architectural expression as

violently as the paintings of Dubuffet transcended the norms of pictorial art; an architecture

whose concepts of order were as far removed from those of'architectural composition' as those

of Pollock were removed from the routines of painterly composition (ie balance, congruence or

contrast of forms within a dominant rectangular format . .); an architecture as uninhibited in its

response to the nature of materials 'as found', as were the composers of 'musique concrete' in

their responses to natural sounds 'as recorded'.44

The abandonment by musique concrete of the traditional structures of western music '. ..

gave a measure of the extent to which "une architecture autre" could be expected to

abandon the concepts of composition, symmetry, order, module, proportion,

"literacy in plan, construction and appearance"'45 as it had been understood from

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

202 ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY 33: 1990

Fig. 7 Alison and Peter

_ times to Smithson, Eduardo Paolozzi and

_. an_ aesthetic _ matte.......... __ Nigel Henderson, 'Patio an

Pavilion' at This is Tomorrow

exhibition, Whitechapel Art

Gallery, London, 1956

projects of the lae15s-Cuse it frxmThe group aimed at a primeval

to conform to his de_tion, butin1956Banexpression of architecture

comprising an enclosed space (the

the:i~"~ Thi iToooe btin pavilion) in the world (the

symbolic1~~~~~~. patio). Fragments of humble

Du~ believed_'~ that the moexistence were scattered around

classical times to the Modern Movement. Clearly, for Banham architecture autre was

essentially an aesthetic matter and questions about function and the daily demands of the

architecture's occupants were secondary if not minor.

The Smithsons' New Brutalist work may have satisfied Banham's definition up to

the time of his December I955 article, and there were occasions when their Brutalist-

derived projects of the later I95os - 'Cluster City' for example - continued

to conform to his definition, but in I956 Banham began to doubt the architecture

autre integrity of the Smithsons' New Brutalist work, and turn towards a new

source of anti-art alternatives. Ironically, this new source also directly involved the

Smithsons.

The project which Banham had doubts about was the Patio and Pavilion environment

which the Smithsons, Eduardo Paolozzi and Nigel Henderson worked on together for

the This is Tomorrow exhibition of I956. Inspired by the way that East Enders used their

backyards and sheds for a diversity of activities and pursuits, Patio and Pavilion was a

symbolic semi-recreation of Henderson's own backyard in Bethnal Green. Just as

Dubuffet believed that the more individual a mark, the more it signified all humankind,

so Patio and Pavilion represented (according to the artists' statement in the exhibition

catalogue) '. .. the fundamental necessities of the human habitat in a series of symbols.

The first necessity is for a piece of the world - the patio. The second necessity is for an

enclosed space - the pavilion. These two spaces are furnished with symbols for all

human needs'. 46 The debris of daily life scattered around the exhibit - a bicycle tyre,

rocks, tools, a pin-up - symbolized desires and aspirations that were basic and

unheroic in the art brut sense (Fig. 7).

Banham disliked two interrelated aspects of the exhibit: its traditionalism and its

artiness. Commenting on the group's statement, he wrote,

Such an appeal to fundamentals in architecture nearly always contains an appeal to tradition and

the past - and in this case the historicising tendency was underlined by the way in which the

innumerable symbolic objects ... were laid out in beds of sand in a manner reminiscent of

photographs of archaeological sites with the finds laid out for display. One or two discerning

critics ... described the exhibit as 'the garden-shed' aesthetic but one could not help feeling that

this particular garden shed ... had been excavated after the atomic holocaust, and discovered to

be part of European tradition of site planning that went back to archaic Greece and beyond.47

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BANHAM AND OTHERNESS 203

...*~ . .:: : Fig. 8 Alison and Peter

Smithson, 'Sugden House',

Watford, 1956

they had frequently.emphasiedtheIn its attempt to combine

arhtcue(nldnheeryMdr oeet. architecture brute with

be le y d d as a t n in s h of suburbia, 'Sugden House' was,

that, for Banham, a tradtomutbaiaording to Banham, a 'subtl

and appearance'.48 To Banm t was the Smi ' lt ' y subversive' building

wa.: ' --,-.-'---- ~j

Banham could not fairly accuse the Smithsons of inconsistency about 'the past' because

they had frequently emphasized their desire for continuity with the earlier periods of

architecture (including the early Modern Movement). Furthermore art autre itself could

be legitimately described a a tradition in search of fundamentals. The key difference was

that, for Banham, a tradition must be attitude-led: notform-led; the Smithsons were

becoming seduced by the appearance of the primitive, t the aesthetic ofart brut. Patio and

Pavilion was too self-conscious and 'arty' - inelegance and bloody-mindedness had

given away to elegance and formal ordering.

Banham did not completely change his mind in I956 about the Smithsons' New

Brutalst-influenceedwork. Their 'Sugden House' in Watford (completed in t957;

Fig. 8), a mixture of suburbia and architecture brute, was described by one offended

commentator as a '. . . shocking piece of architectural illiteracy in plan, construction

and appearance'.4 To Banham it was athe Smithsons' last 'subtly subversive' build-

ing.49 Later work such as their next important building, t the Economist Cluster in St

James's, London (I959 to I964), demonstrated more conventional architectural solu-

tions in which the Smithsons turned their backs on the notion of une architecture autre.

The same was true of the New Brutalism as a movement. Wmhere once for Banham it

had promised to be an alternative to conventional architecture, it rapidly became just

another stylistic option characterized by rough-cast concrete: 'In the last resort they

[both the Smithsons and other Brutalists] are dedicated to the traditions of architecture

as the world has come to know them: their aim is not 'une architecture autre' but, as

ever, 'vers une architecture'.50 Few Brutalists would have disagreed- nor, by the

I960s, would they have believed it should be otherwise.

If Brutalism had seemed to hold the greatest potential for une architecture autre in the

early to mid I95OS, it was another- popular culture- that seemed most hopeful in

956. The Independent Group's foray into popular culture topics in the I 954/55 season

- which included Banham's own musings about the symbolism of contemporary

Detroit cars- led directly to two historically important manifestations of early Pop

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

204 ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY 33: I990

source of aesthetic otherness

U'?: , , I' '_.,, ,'(: k-,

exhibition, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, 19.6

culture in 1956: the exhibit by Richard Ham

the This is Tomorrow exhibition, and the Sm

shared a common concern with the 'reality

logically necessitated a downplaying of gran

of the artist-architect. Like Paolozzi and th

exhibit, Hamilton et alia rejected any abstr

logy and form. But, whereas the Smithsons

version of the primitive, Hamilton et alia ar

of meaningful imagery but the developmen

and utilise the continual enrichment of v

notorious for its inclusion of a life-size pho

high robot with flashing lights from The F

food, optical effects and 'rotorelief discs, an

- was not a programme, but a sample of the

of modern urban life. (To accompany it, Ham

of Pop art: Just what is it that makes today's h

were dismissive but Banham applauded t

barriers, prise open all watertight compart

on the move ... I find it the most exciting t

'.52 Banham valued the exhibit for its atti

anti-formalism.

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BANHAM AND OTHERNESS 205

Fig. Io Alison and Peter

ii.'irii9!s891The~~~~ Smithson, 'House of the Future',

::.:di;'?~ i t N-1956

March, 956 (Fig. ). nWith the 'House of the Future',

the Smithsons were coming to

terms with popular culture and

reality in whih ' potentially radvical i mplications

tI~Q`N jfor architecture

ii;"??

The Smithsons' House of t

March, acter956 (Fig zedo)

given a lecture on the gul

solutions Their thinking f

Mass production advertising

aspirations and standard ofbl

are t o match its powerful and e

Here

Herewe can seewe

the Smithsons

can purporting

see tothe

accept the 'reality o

Smit

namely 'the cultural obje

reality in which, whenmass

art brut primitivism of th

that characterized the th

illustrated than in a statement

i954 has been a key year. It

imagery; that automobile ma

elevations) classic box-on-whe

of the work of Gropi us t th

The Smithsonso anti-tradi

'popular' culture which, w

explosive cocktail.

Brutalism usually implie

came to terms with popular culture would have to be mass producible. This, the

Smithsons pointed out, was already underway:

... the mass production industries had already revolutionised half the house - kitchen,

bathroom, laundry, garage g without the intervention of the architect, and the curtain wall and

14

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

206 ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY 33: I990

the modular pre-fabricated building were causing us to revise our attitude to the rela

between architect and industrial production.56

The House of the Future took this development to a further stage. It was an in

mixture of building industrialization and Detroit-influenced car styling. The

nents that comprised the House were to be mass produced but, as with car prod

each component was used only once in each unit (house). This solved the probl

industrialization leading to repetition and standardization with the resultant v

dullness. With the Smithsons' approach there was the possibility for an annua

change and even customization from a kit of parts. The crucial difference fro

other experimental all-plastics houses of the I950s - such as Coulon and S

Maison Plastique, also of 1956 - was the House's shameless styling and con

appeal. The other plastics houses were essentially in the tradition of mass-pro

pre-fabricated housing which stretched back in its current form to early Mode

The House of the Future looked not towards architecture for guidance, but tow

apogee of advanced consumer product design: the American automobile.57

The House of the Future represented a radical break with conventional archit

practice and thinking. Traditionally, styles of and trends in product desi

followed in the wake of the 'mother' art, architecture. The Smithsons were turn

structure on its head and proposing an architecture that took its lead from ind

design, so offering the public (as Banham wrote in a review) 'new aesthet

planning trends and new equipment, as inextricably tangled together as the styl

engineering novelties on a new car'.58 Could this be an even more authentic arch

autre than the New Brutalism? Banham realized that to draw a parallel between

and a car in particular, or consumer products in general, was misleading - at l

one respect. In a letter to the author in 1980 he explained:

Appliances are made in one place, shipped to another to be sold, and then consumed som

else. The bulk of housing ... is made, sold, and consumed in one and the same place, an

place is a crucial aspect of the product.59

Houses are, therefore, not like consumer products because they are not po

consumers attitudes to them are not the same. On the other hand a house could b

consumer product if it was thought of as a piece of industrial design. This, Banha

was a bigger mental leap than might be imagined for it required the architect to

immersed in technology. This type of architect would have to ditch all of the

cultural attitudes that he had imbibed as a student, and most of the architectura

he had picked up. It was no good having a superficial smattering of techno

information because it would be misunderstood or outdated. What was needed

thorough understanding of the nature of technology itself, and a wholeh

commitment to it.

The architect's attitude to technology and technology's relationship to archit

were the two issues that Banham was finding increasingly central to his d

research into the Modern Movement of the 'first machine age' in architecture

caused major difficulties with his supervisor, Nikolaus Pevsner, whose commitm

a sachlichkeit Modernism based on classical aesthetics had been expounded in his s

Pioneers of the Modern Movement, published in 1936, and subsequent articles. By the

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BANHAM AND OTHERNESS 207

I95os these issues had crystallized and Banham raised them in an art

acknowledged as a landmark in the revised history of Modernism

Aesthetic', which appeared in the Architectural Review in April 1955,

that

The 'Machine Aesthetic' of the Pioneering Masters of the Modern Movement was ... selective

and classicizing, one limb of their reaction against the excesses of Art Nouveau, and it came

nowhere near an acceptance of machines on their own terms or for their own sakes.60

This was because '. . . theorists and designers of the waning Twenties cut themselves

off not only from their own historical beginnings, but also from their foothold in the

world of technology'.61 Ultimately, the 'pioneering masters' - Le Corbusier, Gro-

pius, Mies et alia - accepted the machine and technology only on a superficial,

symbolic and stylistic level. The lack of depth in their understanding led them to

misinterpret temporal effects for timeless aesthetic conditions: they thought the 'boxy'

look of post World War One cars was the result of the attainment of mechanical

sophistication and the 'type-form' which corresponded to the pure phileban solids

beloved by architects. Evolution of technology and art had apparently culminated in an

all-powerful aesthetic universalism.

Those visual characteristics may have coincided at a particular historicaljuncture but

the experimental studies into the performance of shapes in motion presaged '. . the

rapid revolution of an anti-Purist but eye-catching vocabulary of design . .62 for cars

and other forms of transport. Streamlining had come into being. Architects, however,

paid little attention to these developments and held on to forms which, technologically,

were becoming increasingly dated. In the conclusion to Theory and Design in the First

Machine Age, published in I960, Banham continued the theme of his I955 article:

As soon as performance made it necessary to pack the components of a vehicle into a compact

streamlined shell, the visual link between the International Style and technology was broken ...

though there was no particular reason why architecture should take note of these developments

in another field or necessarily transform itself in step with vehicle technology, one might have

expected an art that appeared so emotionally entangled with technology to show some signs of

this upheaval.63

None was evident amongst the pioneering masters and Banham concluded that their

way of thinking owed little to live technology but much to classical aesthetics.

Had Modernists really considered the fundamental condition of technology they

would have realized that the only constant was change. In I955 this was, in Banham's

opinion, still one of the most pressing issues:

... we are still making do with Plato because in aesthetics, as in most other things, we still have

no formulated intellectual attitudes for living in a throwaway economy. We eagerly consume

noisy ephemeridae, here with a bang today, gone without a whimper tomorrow - movies,

beachwear, pulp magazines, this morning's headlines and tomorrow's TV programmes - yet

we insist on aesthetic and moral standards hitched to permanency, durability and perenniality'.64

The acceptance of the 'new' conditions would require a new aesthetic and this could

lead to the architecture autre Banham so desired. Although an acceptance of expenda-

bility lay behind the styling of the American design - such as Detroit cars -

worshipped by Banham and other Independent Group members, it was only in an

isolated case like the House of the Future where it was manifested in architecture.

14*

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

208 ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY 33: 1990

Another - and more significant - exception Banham found to this general rule w

the Futurists whom Banham rediscovered during his researches into the Mode

Movement during the g950s. They emerge as central to the revised version o

Modernism in Banham's doctorate which eventually was published as Theory a

Design in the First Machine Age. It appeared to Banham that Modernist architects an

historians in the I93os and '40s - such as Walter Gropius, Sigfried Giedion and, indee

Pevsner - had tidied up the history of their movement to the extent that certain ke

aspects of it - in particular Futurism and Expressionism - had been excluded as if th

had been madmen in the family who needed to be kept away from the gaze of the

public. What particularly appealed to Banham is that they represented an architectur

autre within Modernism: an alternative to an architecture of classical aesthetics that, in

the case of Futurism, went some considerable way to running with live technology.

The nub of the matter was that sachlichkeit Modernists made technology conform to

classical aesthetics; the Futurists sought a new aesthetic based on the condition of

technology.

Futurism dates back to I909 when F. T. Marinetti, the founder and chief protagonist

of the movement, delivered a series of outspoken and uncompromising manifestos to

provoke a reaction in the Italian art world and free, as Marinetti described it, '. . . this

land from its smelly gangrene of professors, archeologists, ciceroni and antiquarians'.65

Like many other artists at the time, the Futurists believed they were witnessing the

dawning of a millennium. Like the 'pioneering masters' they looked at the machines

around them but saw no lessons inherent in the precision of machinery, no mathemat-

ical order nor classical harmony, but power, dynamism and excitement of the new

technology which should not be observed with the detached air of the academic, but

experienced for all its compulsive sensations. Jettisoning the aesthetic and cultural

conventions of the past, the Futurists embraced the radically new beauty of the

twentieth century, '... the beauty of speed. A racing car whose hood is adorned with

great pipes, like serpents of explosive breath - a roaring car that seems to ride on

grapeshot is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace'.66

A celebratory and romantic spirit infused all the Futurists' outpourings, including

the 'Manifesto of Futurist Architecture', published in 1914 and written by Marinetti

and Antonio Sant'Elia.67 The 'New City' was urgently needed, the authors declared,

because the current city belonged to the past:

As though we - the accumulators and generators of movement, with our mechanical

extensions, with the noise and speed of our life - could live in the same streets built for their

own needs, by the men of four, five, six centuries ago.68

The Futurist city represented a vision that ran counter to the static and controlled

classicism of the 'pioneering masters'. Dynamism, energy and movement were

paramount:

We must invent and rebuild the Futurist city: it must be like an immense, tumultuous, lively,

noble work site, dynamic in all its parts; and the Futurist house must be like an enormous

machine ... the lifts must climb like serpents of iron and glass up the housefronts. The house of

concrete, glass and iron . . ., extremely 'ugly' in its mechanical simplicity ... must rise on the

edge of a tumultuous abyss: the street . . . will descend into the earth on several levels ...69

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BANHAM AND OTHERNESS 209

It is not hard to appreciate the sense of identification the sympathizers with

autre must have felt with the Futurist sensibility. Here was an aesthet

unfinishedness and of 'ugly' vitality. Furthermore, the Futurists had

with the condition of technology in the twentieth century: '... th

characteristics of Futurist architecture will be obsolescence and transien

last less long than we. Each generation will have to build its own city'.

and transience had never before been elevated to the position of essential

The Futurists had squarely come to terms with the idea that technology

continual change.

In the light of his interest in technology and quest for an architecture aut

seemed tailor-made for Banham in the 1950s. His first major articl

deals with Sant'Elia and was published in the Architectural Review

the time when the whole issue of architecture autre was taking sh

the article is concerned with establishing the facts about the auth

Manifesto, and informing an as yet uninformed readership about Sant

Banham conclusively reasons that Sant'Elia needs to be acknowledge

of the International Style' because he was able to '. .. combine a comple

of the machine-world with an ability to realize and symbolize th

in terms of powerful ... form'.7 Banham also argues that Sant'Elia

porary relevance and so is even more appropriate as a guide to an archit

'... basing his whole design on a recognition of the fact that in the me

one must circulate or perish ... [he] seems to have foreseen the techno

the Fifties .. ..72

Banham continued his rehabilitation of Futurism with a lecture to the Royal Institute

of British Architects in 1957,73 an article in Arts magazine in I960,74 and, of course, the

publication of Theory and Design in the First Machine Age in 1960. In the Arts article and,

to a lesser extent, in Theory and Design, Banham presents Futurism not as a dead

art-historical movement, but as a relevant and urgent attitude to living in mid

twentieth-century society. In Arts, he recalls the rediscovery of Futurism in about 1954,

at a time when his generation were in full revolt against the Herbert Read version of

Modernism. Banham draws a number of parallels between Futurism and contempo-

rary experimentation and innovation - Russolo's 'Art of Noises' and musique concrete;

and Marinetti's 'Words in Liberty' and Beat poetry for example. Machine-age para-

phenalia listed by Boccioni in one of the manifestos and quoted by Banham -'...

gramophone, cinema, electric advertising, mechanistic architecture, skyscrapers ...

nightlife ... speed, automobiles, aeroplanes ...' - are found to accord with con-

temporary life: '... hi-fi, stereo, cinemascope and (in Richard Hamilton's succinct

phrase) "Polaroid Land and all that jazz" .75 He continues:

As Richard and I and the rest of us came down the stairs from the Institute of Contemporary Arts

those combative evenings in the early fifties, we stepped into a London that Boccioni had

described, clairvoyantly. We were at home in the promised land that the Futurists had been

denied, condemned instead to wander in the wilderness for the statutory forty years ... No

wonder we found in the Futurists long lost ancestors, even if we were soon conscious of having

overpassed them. Overpassed or not, they seemed to speak to us on occasions in precisely the

detail that the ghost spoke to Hamlet.76

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

210 ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY 33: I990

Having made out the case for its prophetic aspect, Banham offered its lesson:

While life remains as Futurist as it has been, indeed becomes increasingly so, concepts of art and

aesthetics based on eternal values will probably continue to prove perishable, like Roger Fry's,

while Futurism, founded on change and 'the constant renewal of our environment', looks to be

the one constant and permanent line of inspiration in twentieth-century art.77

This is Banham's argument for Futurism as anti-art, as art autre with implications for

architecture autre.

Banham allots a whole one of the five sections in Theory and Design in the First Machine

Age to an examination of Futurism, but it is in the book's conclusion where he develops

its full architecture autre status and brings it into the debate about contemporary

architectural thinking. Having praised Futurism's positive attitude to technology and

chastised Modern Movement architects for cutting themselves off from the 'philo-

sophical aspects of Futurism',78 Banham links Futurism with the then contemporary

work of Buckminster Fuller:

There is something strikingly, but coincidentally, Futurist about the Dymaxion House. It was to

be light, expendable, made of those substitutes for wood, stone and brick of which Sant'Elia had

spoken, just as Fuller also shared his aim of harmonising environment with man, and of

exploiting every benefit of science and technology. Furthermore, in the idea of a central core

distributing services through surrounding space there is a concept that strikingly echoes

Boccioni's field-theory of space, with objects distributing lines of force through their

surroundings.

Many of Fuller's ideas, derived from a first-hand knowledge of building techniques and the

investigation of other technologies, reveal a similarly quasi-Futurist bent . ..79

Whether Fuller would have been happy to have been likened to the Futurists is highly

doubtful for he thought of all European Modernists as artists (and therefore primarily

concerned with aesthetics) rather than technologists/problem-solvers. Banham quotes

at length in the conclusion Fuller's vitriol about European designers which, interest-

ingly - for it establishes a formal link between Fuller and Independent Group

members - comes from an at-the-time unpublished letter of I955 from Fuller to

Independent Group member and Fuller-enthusiast John McHale.80 In part it reads:

The 'International Style' brought to America by the Bauhaus innovators, demonstrated

fashion-inoculation without necessity of knowledge of the scientific fundamentals of structural

mechanics and chemistry. The International Style 'simplification' then was but superficial. It

peeled off yesterday's exterior embellishment and put on instead formalised novelties of

quasi-simplicity, permitted by the same hidden structural elements of modern alloys that had

permitted the discarded Beaux-Arts garmentation.

... the Bauhaus and International used standard plumbing fixtures and only ventured so far as

to persuade manufacturers to modify the surface of the valve handles and spigots, and the colour,

size, and arrangements of the tiles. The International Bauhaus never went back of the

wall-surface to look at the plumbing... they never enquired into the overall problem of sanitary

fittings themselves ... In short they only looked at problems of modifications of the surface of

end-products, which end-products were inherently sub-functions of a technically obsolete

world.81

Banham uses Fuller to place the Modern Movement in conceptual and cultural

perspective. By featuring Fuller's criticisms of 'International Style' architecture,

Banham exposes the artistic bias of Modernism and the fact that it was in search of, first

and foremost, a machine aesthetic rather than a profound or radical application of

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

BANHAM AND OTHERNESS 211

Fig. ii Buckminster Fuller, the Dymaxion Deployment Unit, 1944

A later version of the 1927 prototype, this building was exhibited in the sculpture g

Museum of Modern Art in New York. Hundreds were manufacturedfor military u

war

technology to architectural problems. It rejected a radical, other

traditional, architectural one.

Fuller's closest point of contact with Futurism was his touchs

characteristic of technology was the 'unhaltable trend to co

change'.82 An 'architectural' solution was only one possible soluti

technological problem as far as Fuller was concerned, and

'architecture' as it was generally recognized. His 'Dymaxion H

was not equivalent to a Modernist object-type 'machine fo

connotations of aesthetic formalism, but part of Fuller's

... concept of air-deliverable, mass-produceable, world-around, hum

nurturing scientific dwelling service industry as means of transforming

from a weaponry to livingry focus, thereby to render successful all

only a few, on the premise that a comprehensible anticipatory design

increased technical efficiency and upping of overall performance per po

bring about physical success for humanity - never to be obtained on p

eliminating fundamental causes of war.83

This content downloaded from

111.187.76.22 on Tue, 09 May 2023 15:13:49 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

212 ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY 33: I990

Other 'architectural' solutions by Fuller - such as the 'Wichita House' of 1946 (an

updating of the 'Dymaxion House', and his famous geodesic domes, which are highly

unconventional in visual terms - are well known although Fuller described himself as

an 'inventor' rather than an architect. Banham emphasized this distinction:

... the architectural profession started by mistaking him for a man preoccupied with creating

structures to envelop spaces. The fact is that, though his domes may enclose some very

seductive-seeming spaces, the structure is simply a means towards, the space merely a

by-product of, the creation of an environment, and that given other technical means, Fuller

might have satisfied his quest for ever-higher environmental performance in some more 'other'

way. 84

Architects were generally extremely hostile to Fuller's work, arguing that it ignored

one of the most vital ingredients of architecture in the traditional sense: the aesthetico-

symbolic. Philip Johnson spoke for many: 'Let Bucky Fuller put together the

dymaxion dwellings of the people so long as we architects can design their tombs

and monuments'.85 By his commitment to problem solving, his attitude to technol-

ogy, and his lack of interest in aesthetics, Fuller really did seem to offer an architecture

autre.

Fuller may seem to provide the obvious model for Banham for an architecture autre

but, around the time of Theory and Design, Banham can justifiably be accused of

inconsistency. The problem revolves around the issue ofjust how autre Banham wants

his architecture to be. Theory and Design, Banham acknowledged, was a revisionist text

which sought to counter the discrimination which had taken place since the late I920s

towards sachlichkeit or Pevsnerian Modernism. Therefore, Theory and Design empha-

sizes the Expressionist and, especially, Futurist aspects and legacy of Modernism.

Banham did not argue his case on formalistic or stylistic grounds which he saw as

relatively unimportant - hence his lack of interest in the architectural Neo-

Expressionism of the 1950s. While Pevsner interpreted Le Corbusier's Ronchamp,

Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum, or Eero Saarinen's TWA terminal

as significant (although not beneficial) architectural developments, to Banham

they represented little more that the continuation of the work of the heroic, form-

giving Modernist artist-architect: 'New shapes notwithstanding, it is still the

same old architecture, in the sense that the architects involved have relied on their

inherited sense of primacy in the building team, and have insisted that they alone shall

determine the forms to be employed'.86 His interest in Expressionism in Theory and

Design is not to do with form so much as content - the significations and 'meanings'

of Expressionist work and the implications for the value system of Modernism.

His main argument for Futurism, as we have seen, was in terms of its attitude to

technological society: that cultural activity responded positively and directly to

technological progress.

Yet Banham also praises Futurism on more than one occasion for its image of

modernity. Of one of Sant'Elia's most fully worked out perspectives of 'The New

City', Banham wrote in Theory and Design that it brought '. . . together skyscraper

towers and multi-level circulation in an image that has dominated modern ideas of

town-planning right down to the present time',87 And in his Architectural Review article

of 1955, Banham favourably compares Sant'Elia with Adolf Loos remarking that,