Professional Documents

Culture Documents

10 2307@20004780

10 2307@20004780

Uploaded by

Shreyans MishraCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- A Guide - To - Stoic - Living - Keith SeddonDocument196 pagesA Guide - To - Stoic - Living - Keith Seddonstrayl1ght100% (10)

- Buddhism in 10 Steps (Ebook)Document51 pagesBuddhism in 10 Steps (Ebook)Sarang BhaisareNo ratings yet

- What Is Meditation ?Document33 pagesWhat Is Meditation ?JonathanNo ratings yet

- Aspects of Spiritual Practice in Early YogacaraDocument33 pagesAspects of Spiritual Practice in Early YogacaraGuhyaprajñāmitra3No ratings yet

- The Psychology of Worldviews: Mark E. Koltko-RiveraDocument56 pagesThe Psychology of Worldviews: Mark E. Koltko-RiveraPablo SeinerNo ratings yet

- Worldview Defhistconceptlect PDFDocument50 pagesWorldview Defhistconceptlect PDFbilkaweNo ratings yet

- Rebirth and The Western BuddhistDocument93 pagesRebirth and The Western BuddhistPilar ValerianoNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Buddhism: Four LecturesDocument63 pagesFundamentals of Buddhism: Four LecturesWinNo ratings yet

- BST 203-Christian WorldviewDocument10 pagesBST 203-Christian WorldviewAdaolisa IgwebuikeNo ratings yet

- Capriles E. - Beyond Mind. Steps To A Met A Trans Personal Psychology IJTS 2000Document52 pagesCapriles E. - Beyond Mind. Steps To A Met A Trans Personal Psychology IJTS 2000Barbora ChvatalovaNo ratings yet

- Theravada Buddhism02Document3 pagesTheravada Buddhism02Kenn KennNo ratings yet

- Rimé and Dzogchen Article DerocheDocument30 pagesRimé and Dzogchen Article DerocheSara MessiNo ratings yet

- Reflections On Suffering and Happiness: The Centered WheelDocument4 pagesReflections On Suffering and Happiness: The Centered WheelAutumn HughesNo ratings yet

- BST 201 Christian Worldview 1Document30 pagesBST 201 Christian Worldview 1enochnanfwangNo ratings yet

- Epoche and Śūnyatā: Skepticism East and WestDocument24 pagesEpoche and Śūnyatā: Skepticism East and WestJohn HaglundNo ratings yet

- Buddhist Philosophy and Its Europen ParallelsDocument16 pagesBuddhist Philosophy and Its Europen ParallelsDang TrinhNo ratings yet

- A Little Disillusionment Is A Good ThingDocument16 pagesA Little Disillusionment Is A Good ThingCTSNo ratings yet

- 9277 9952 1 PB PDFDocument53 pages9277 9952 1 PB PDF张晓亮No ratings yet

- Philosophical Foundations in Psychology AssignmentDocument16 pagesPhilosophical Foundations in Psychology Assignmentratheeanushka16No ratings yet

- YogaandecologyDocument12 pagesYogaandecologyalinesanyogaNo ratings yet

- Written Report in Sts Group 2Document5 pagesWritten Report in Sts Group 2aries sangalangNo ratings yet

- Consciousness and Self-ConsciousnessDocument21 pagesConsciousness and Self-Consciousnessantonio_ponce_1No ratings yet

- STEPHAN SCHWARTZ: Nonlocal Consciousness and The Anthropology of Religion.Document5 pagesSTEPHAN SCHWARTZ: Nonlocal Consciousness and The Anthropology of Religion.Michel BLANCNo ratings yet

- Jiddu Krishnamurthis Perspective On EducDocument13 pagesJiddu Krishnamurthis Perspective On EducMaria Lancelot maria.No ratings yet

- The Essence of HumanismDocument7 pagesThe Essence of Humanismcliodna18No ratings yet

- The Path To Liberation: Reconciling The Theory of Interdependent Origination With Free WillDocument9 pagesThe Path To Liberation: Reconciling The Theory of Interdependent Origination With Free WillGuiller Martin Cedric GabaoenNo ratings yet

- Mysticism and Theravada MeditationDocument25 pagesMysticism and Theravada MeditationMagdalena SpytNo ratings yet

- Buddhist Ethics - Oxford HandbooksDocument18 pagesBuddhist Ethics - Oxford HandbooksalokNo ratings yet

- Epoche and Śūnyatā - Skepticism East and WestDocument24 pagesEpoche and Śūnyatā - Skepticism East and WestKadag LhundrupNo ratings yet

- Will Focus Emphasizes: The Bhagavadgita and MoralityDocument9 pagesWill Focus Emphasizes: The Bhagavadgita and MoralityFa-ezah WasohNo ratings yet

- Spiritual Advice For Dharma Practitioners of This Degenerate AgeDocument3 pagesSpiritual Advice For Dharma Practitioners of This Degenerate AgeDudjomBuddhistAssoNo ratings yet

- 40 Studies On The Tantras The Spiritual Heritage of India: The Tantras 41Document7 pages40 Studies On The Tantras The Spiritual Heritage of India: The Tantras 41propernounNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Jainism 101Document27 pagesIntroduction To Jainism 101heenamodiNo ratings yet

- On Initiation by Peter Mark AdamsDocument12 pagesOn Initiation by Peter Mark AdamsPeter Mark AdamsNo ratings yet

- Searching For The Extended Self: Parapsychology & SpiritualityDocument23 pagesSearching For The Extended Self: Parapsychology & SpiritualityBryan J WilliamsNo ratings yet

- MokaDocument17 pagesMokaLuis Tovar CarrilloNo ratings yet

- (Asian Folklore Studies Vol. 37 Iss. 1) Francisco R. Demetrio - The Shaman As Psychologist (1978) (10.2307 - 1177583)Document20 pages(Asian Folklore Studies Vol. 37 Iss. 1) Francisco R. Demetrio - The Shaman As Psychologist (1978) (10.2307 - 1177583)Lynnlin GamingNo ratings yet

- Ajahn Brahm, Dependent Origination (2002)Document23 pagesAjahn Brahm, Dependent Origination (2002)David Isaac CeballosNo ratings yet

- Icon by IconDocument6 pagesIcon by IconpropernounNo ratings yet

- America Smiles On The Buddha-Part 2Document3 pagesAmerica Smiles On The Buddha-Part 2frankiriaNo ratings yet

- Religion Compass Volume 3 Issue 1 2009 (Doi 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00120.x) June McDaniel - Religious Experience in Hindu TraditionDocument17 pagesReligion Compass Volume 3 Issue 1 2009 (Doi 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00120.x) June McDaniel - Religious Experience in Hindu TraditionNițceValiNo ratings yet

- Confucianism, Buddhism, HinduismDocument8 pagesConfucianism, Buddhism, HinduismKoRnflakes100% (1)

- The Psychedelic Experience A Manual Based On The Tibetan Book of The DeadDocument61 pagesThe Psychedelic Experience A Manual Based On The Tibetan Book of The DeadAntonella Wagner100% (1)

- FinalDocument6 pagesFinalapi-355717370No ratings yet

- Kalu Rinpoche Ocean of AttainmentDocument90 pagesKalu Rinpoche Ocean of AttainmentTùng Hoàng100% (1)

- Scientology and Religion by Christiaan VonckDocument10 pagesScientology and Religion by Christiaan VoncksirjsslutNo ratings yet

- A Primer on Applied Feel Theory: Rethinking the Relationship with Society (The Equilibrium Texts, Vol. 2)From EverandA Primer on Applied Feel Theory: Rethinking the Relationship with Society (The Equilibrium Texts, Vol. 2)No ratings yet

- Qautrivium of FourDocument84 pagesQautrivium of FourNner G AsarNo ratings yet

- Module - 1 RRES GE110 Introduction Definition of TermsDocument9 pagesModule - 1 RRES GE110 Introduction Definition of TermsAngelica PallarcaNo ratings yet

- SCHMITHAUSEN - The Problem of The Sentience of Plants in Earliest BuddhismDocument128 pagesSCHMITHAUSEN - The Problem of The Sentience of Plants in Earliest BuddhismEugen Ciurtin100% (3)

- Buddha'S Journey To Enlightenment: Aryan SinghDocument10 pagesBuddha'S Journey To Enlightenment: Aryan SingharyanNo ratings yet

- Zureta Reflection PaperDocument5 pagesZureta Reflection PaperYsabella ZuretaNo ratings yet

- The Jains and Their CreedDocument17 pagesThe Jains and Their CreedvitazzoNo ratings yet

- Stress Management FinalDocument66 pagesStress Management FinalBeniram KocheNo ratings yet

- Freedom East and West by J L ShawDocument17 pagesFreedom East and West by J L Shawsatyagraha0No ratings yet

- Buddhism and Immortality: The view of the Immortality of ManFrom EverandBuddhism and Immortality: The view of the Immortality of ManNo ratings yet

- Guide To Stoic Living PDFDocument196 pagesGuide To Stoic Living PDFgaston100% (1)

- 5 Vasundhara Iyer Philosophy AssignmentDocument2 pages5 Vasundhara Iyer Philosophy AssignmentIyer VasundharaNo ratings yet

- ITWRBS Final Examination ReviewerDocument7 pagesITWRBS Final Examination Reviewerprecious DalumpinesNo ratings yet

- Some Popular Symbols in Myanmar CultureDocument10 pagesSome Popular Symbols in Myanmar Cultureoat awNo ratings yet

- Examine The Origins of Commentarial Literature in India 1Document9 pagesExamine The Origins of Commentarial Literature in India 1Wimalagnana RevbNo ratings yet

- Group 2Document30 pagesGroup 2Zyra DimaanoNo ratings yet

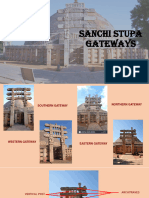

- Sanchi Stupa GatewaysDocument64 pagesSanchi Stupa Gateways520219005 AnweshaMrokNo ratings yet

- The Lotus SutraDocument20 pagesThe Lotus SutraMike PazdaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement On BuddhismDocument8 pagesThesis Statement On Buddhismjoysmithhuntsville100% (2)

- Bus Ethics q3 Mod5 Impact of Belief System Final - Compress 1Document19 pagesBus Ethics q3 Mod5 Impact of Belief System Final - Compress 1Mharlyn Grace Mendez100% (1)

- Eastern PhilosophiesDocument6 pagesEastern PhilosophiesLyza Sotto ZorillaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - BuddhismDocument9 pagesLesson 2 - BuddhismVictor Noel AlamisNo ratings yet

- Siddhartha (Hermann Hesse) (Z-Library)Document112 pagesSiddhartha (Hermann Hesse) (Z-Library)otimasvreiNo ratings yet

- Different VadasDocument3 pagesDifferent VadasGabe DiscourseNo ratings yet

- G7 - Chapter 05 - Short NotesDocument3 pagesG7 - Chapter 05 - Short NotesYenuka KannangaraNo ratings yet

- WRBS11 Q2 Mod5 Comparative Analysis of Dharmic ReligionsDocument22 pagesWRBS11 Q2 Mod5 Comparative Analysis of Dharmic ReligionsJerryNo ratings yet

- Ancient History MCQ PDF by Study Like A ProDocument44 pagesAncient History MCQ PDF by Study Like A ProNirmal SharmaNo ratings yet

- A Gulim La SuttaDocument13 pagesA Gulim La SuttaNiran ChueachitNo ratings yet

- Walking The Tightrope - David YoungDocument177 pagesWalking The Tightrope - David YoungRidma Chathu (Rimi)No ratings yet

- Chapter 5951 - 6000 Spanish NamesDocument184 pagesChapter 5951 - 6000 Spanish NamesAkmal ShahbazNo ratings yet

- Dimensions of The Sacred An Anatomy of The Worlds Beliefs (Ninian Smart) (Z-Library) - CompressedDocument100 pagesDimensions of The Sacred An Anatomy of The Worlds Beliefs (Ninian Smart) (Z-Library) - CompressedEd VulcaoNo ratings yet

- Ancient India and China Test ReviewDocument2 pagesAncient India and China Test Reviewelmoukademtania99No ratings yet

- Rinzai ZenDocument13 pagesRinzai ZenOlly SuttonNo ratings yet

- Buddhism & Jainism AssignmentDocument2 pagesBuddhism & Jainism AssignmentNazmul HasanNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 12 History Thinkers Beliefs and Buildings Cultural DevelopmentsDocument4 pagesCBSE Class 12 History Thinkers Beliefs and Buildings Cultural DevelopmentsRashi LalwaniNo ratings yet

- Senior High School Introduction To World Religion and Belief System School Year 2022-2023Document91 pagesSenior High School Introduction To World Religion and Belief System School Year 2022-2023Vee SilangNo ratings yet

- Enmei JukkuDocument11 pagesEnmei JukkuEsteban DonadoNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Self - 061558Document27 pagesUnderstanding The Self - 061558Reyward FelipeNo ratings yet

- Ajahn Brahmali Buddhist CosmologyDocument24 pagesAjahn Brahmali Buddhist CosmologyMinato NamikazeNo ratings yet

- World Religion PDF World Religion PDFDocument35 pagesWorld Religion PDF World Religion PDFDeina PurgananNo ratings yet

- Theravada Buddhisem BasicDocument96 pagesTheravada Buddhisem BasicRidmini Niluka PunchibandaNo ratings yet

10 2307@20004780

10 2307@20004780

Uploaded by

Shreyans MishraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

10 2307@20004780

10 2307@20004780

Uploaded by

Shreyans MishraCopyright:

Available Formats

Buddhist Ethics

Author(s): David Bastow

Source: Religious Studies, Vol. 5, No. 2 (Dec., 1969), pp. 195-206

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20004780 .

Accessed: 28/06/2014 14:00

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Religious

Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 141.101.201.31 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 14:00:55 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Rel. Stud. 5, pp. 195-206

DAVID BASTOW

Lecturer in Philosophy,Universityof Dundee

BUDDHIST ETHICS

The canonical texts of Early Buddhism describe and explain a way to achieve

a goal.What the goal is isnot immediately clear; many different descriptions

are given of it, and these descriptions can be variously interpreted. It is to

some extent easier to find out what is the way to achieve the goal; the texts

contain frequently repeated lists of stages on thisWay. The best way of

starting a consideration of the nature of the goal and itsmoral status is to

examine themost important of these lists.

The longest and most elaborate first appears in a Sutta inwhich theBuddha

is answering the question 'What are the fruits of a recluse ?'-i.e. what are

the benefits and achievements which men do or can hope for when they

take up the recluse's life? ('Recluse' is an inadequate translation of the Pali

'bhikkhu'. The Sutta is the SamaiinnaPhala Sutta, in D.I the translations I

use are (a) of the Digha Nikaya (D), Dialogues of theBuddha, translated by

T. W. and C. A. F. Rhys Davids, in the series 'SacredBooks of theBuddhists';

(b) of theMajjhima Nikaya (M), Middle Length Sayings, translated by I. B.

Horner, in the Pali Text Society Translation Series.) In answering the ques

tion about the fruits of such a life, the Buddha gives a list of benefits and

accomplishments which is repeated with only minor variations in many of

the Suttas, and which forms the basis for discussion in a great many of the

others. I shall first describe it without any general comment; and later

attempt to explain it and draw conclusions relevant to the topic of the paper.

The Buddha first describes how a householder hears the preaching of 'one

who has won the truth, ... a Blessed One, a Buddha, ... who proclaims the

truth and makes known the higher life ... in all its fulness and all its purity'

(D.I 78). He realises that he cannot lead this higher life as a householder,

and so decides to 'go forth into the homeless state'. He then 'lives self

restrained by that restraint that should be binding on a recluse' (D.I 79).

Firstly, his conduct is good. This is explained in two sections. In the first,

there is a list of abstentions-from destruction of life, taking what is not

given, unchastity, lying words, slander, rudeness of speech and frivolous

talk-each of which is expanded in a way which goes quite beyond mere

overt abstention; e.g. the paragraph about abstaining from the destruction

of life continues 'He has laid the cudgel and the sword aside, and ashamed

of roughness and full of mercy he dwells compassionate and kind to all

creatures that have life' (D.I 4). The second section ismany pages long, and

This content downloaded from 141.101.201.31 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 14:00:55 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

i96 DAVID

BASTOW

contains the most elaborate and detailed accounts of the various kinds of

activity inappropriate for a recluse-accepting presents, attending fairs and

shows, playing games etc.; and of the various things a recluse may not do as

a means of livelihood-sorcery, soothsaying of many kinds, carrying out

sacrifices etc. A recluse who has dealt with these two sections is said to be

'master of the minor moralities', and to have the confidence which comes

from seeing no danger from any side so far as concerns one's self restraint

in conduct (D.I 79).

The next stage is 'keeping guarded the door of one's senses'. 'When [the

recluse] sees an object with his eye he is not entranced in the general appear

ance or the details of it. He sets himself to restrain that which might give

occasion for evil states, covetousness and dejection from flowing over him'

(were he unrestrained), and so with the other senses (D.I 8o). Thereby he

becomes 'mindful and self-possessed', being aware of whatever he sees and

of whatever he does, aware also of all his mental states, his feelings and his

thoughts (seeD.II 324-5). With respect to each of these aspects of himself

of which he is conscious, he 'keeps himself aware of all it really means'.

This phrase refers to the philosophical doctrines of the transience of every

thing, and of dependent origination-a variation on 'Every event has a

cause'. I shall return to these doctrines later.

Then the Bhikkhu is described as one who is content with the fewest

possessions: a robe and sufficient food to keep him alive-so that all that he

has he can takewith him in his wanderings. Thus he is able to concentrate

on putting away the Five Hindrances; hankering after theworld, the corrup

tion of the wish to injure; weakness and sloth of heart and mind; worry and

irritability; wavering and perplexity. He then experiences the gladness and

joy which result from the knowledge that one is free of these fetters. 'Being

thus at ease he is filled with a sense of peace, and in that peace his heart is

stayed' (D.I 84). The Buddha then describes the Four Meditations: that of

detachment from the world; serenity of concentration; equability-i.e.

looking on rival mental states with impartiality, imperturbability; and

finally 'the putting away of ease and pain', of elation and dejection, (being)

in a state of pure self-possession and equanimity' (D.I 86).

The recluse then applies himself to the insight that comes from knowledge

of the philosophical doctrines mentioned earlier.

There follows a description of various mystical abilities; including insight

into the hearts of men, into one's own previous lives, and the lives and re

births of all beings. This last ability gives one knowledge of the operation of

karma, the natural law whereby a man is reborn into a state determined by

his conduct in previous lives. The knowledge of karma is straightforwardly

inductive.

The final stage is that of the destruction of the Asavas, cankers, defiling

impulses, or corruptions. There are three usually mentioned-that of lust,

This content downloaded from 141.101.201.31 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 14:00:55 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BUDDHIST ETHICS 197

with particular reference to hankering after rebirth in a sensuous world;

that of becoming, hankering after rebirth of any kind; and that of ignorance,

i.e. of the Four Noble Truths, of pain, its origin, its cessation, and the Path

that leads to its cessation. When the recluse has conquered these corruptions

'in him, thus set free, there arises the knowledge of his emancipation and he

knows "Rebirth has been destroyed. The higher life has been fulfilled.What

had to be done has been accomplished"' (D.I 93).

The question of first importance about theWay just described is,Why is

it as it is ?Why does it contain just those elements in just that order ?Answers

may be on the one hand in terms of historical processes, or on the other in

terms of some unifying thought. An explanation of the second kind, giving

a reasoned defence of the list of elements as they stand, will be, if it turns out

to be possible, what may be called a favourable interpretation, in that it

will give the list coherence. The theory now to be proposed and examined

is that the list isunified by the two concepts of self-restraint and emancipation.

Nearly all the component parts of theWay fall into one or both of the cate

gories of progressive stages of achievement on the one hand, and themeans

necessary to these achievements on the other. The latter are different kinds

of self-restraint, the former, the actual achievements, are different kinds of

emancipation, becoming free. As already quoted, theWay is introduced as

that of a recluse who 'lives self restrained by that restraint that should be

binding on a recluse'; and when the recluse has progressed through all the

stages of theWay, 'in him, thus set free, there arises the knowledge of his

emancipation'.

The first stages concern self-restraint as regards conduct in theworld, how

one behaves towards other people and oneself. Here achievement and method

of achievement are hardly separated; there are no specific instructions about

how to become honest, chaste, truthful, etc.; and the emancipation resulting

from this stage is emptily described as freedom from danger on any side as

far as regards one's self-restraint in conduct. The obvious question here is

'self-restraint fromwhat?', and this is a matter I shall have to discuss later.

The next kind of restraint is concerned not with actual conduct, but with

states of mind which are very close to conduct, the Five Hindrances; these

are hankerings and frettings, intellectual laziness and wavering. It may be

felt that the separation of these from the morality of conduct is artificial,

that unless such dispositions are manifested in action they are unreal; but

it seems that the Buddhist writers thought that even though one's conduct

was all that it should be, one's moral states could retain traces of the impulses

and weaknesses which led to wrong action. The ordering is certainly not

absolutely systematic; no clear line can be drawn between the expansion of

the abstention from killing in the first stage, '(the recluse) dwells compassion

ate and kind to all creatures that have life', and the second of theHindrances;

'Putting away the corruption of the wish to injure, he remains with a heart

This content downloaded from 141.101.201.31 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 14:00:55 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

i98 DAVID BASTOW

free from ill-temper, and purifies his mind of malevolence' (D.I 82). But

there is a general change of emphasis, or of point of view, from one's actions

and mental states as they have consequences in the world, to one's mental

states as one's own private concern.

Preceding the description of the Five Hindrances are two sections concerned

more with methods than with achievements. The recluse must be guarded

as to the doors of his senses, and mindful and self-possessed. These describe

a discipline of self-awareness, applicable to actions, but particularly directed

to the control of one's mental states. The first stage in the achievement of

mindfulness is bodily control, and in particular control of the breathing

but the control is always directed at the ends I have described, and especially

freedom from the Hindrances, unskilled mental states-i.e. those which

hinder one from the achievement of the goal. The recluse wishes to be in

complete control of all the components of his individuality; he therefore

must be conscious of all that goes on within him; no bodily movements or

mental wanderings must go unrecognised forwhat they are. The symbol of

success in these efforts is the recluse's contentment with themeanest posses

sions; the robe, and the food of themendicant.

When a recluse has destroyed theHindrances his efforts move to a higher

plane-that of the Jhdnas, meditations. This presupposes aloofness from

unskilled states of mind; the effort and the achievements are now beyond

the particular cravings and weaknesses which may survive themastery over

conduct, and are concerned with general attachment to intellect and

argument, and to such states as rapture and joy. In the state achieved in

the Fourth and final Meditation, the recluse is totally irresponsive to the

world, "'all is still", and (his) senses are completely withdrawn from the

external world' (Introduction toM.III, p. xxxi). This seems to be a trance

like state, which the recluse must leave in order to lead his daily life; but

having achieved the Fourth Meditation none of his experiences will bring

about any emotional reaction in him. He will view everything with 'pure

self-possession and equanimity, without pain and without ease'. The term

'self-restraint' seems hardly strong enough to describe efforts of this nature,

but the image of freedom from fetters, of emancipation, still seems appropriate

as an account of what has been achieved. The recluse is now in no way bound

to the demands of his senses, nor to the subtler demands of his intellect, or

any constraint to avoid whatever brings pain or dis-ease of any kind, or to

seek what brings ease or joy.

The mystical abilities are neither methods of self-restraint nor, in general,

achievements of emancipation: but rather by-products of the achievements

already reached. Some are included merely because it was thought that

some recluses did experience them, and were not thought to be specifically

Buddhist. Such abilities as that of Iddhi-'he becomes visible or invisible . . .

he penetrates up and down through solid ground, as if through water . . .',

This content downloaded from 141.101.201.31 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 14:00:55 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BUDDHIST ETHICS I99

etc.' (D.1 88)-are included for historical reasons; non-Buddhist recluses

claimed to have them, so they were not beyond the powers of those following

the Buddhist Way, but the Buddha had no interest in them. The abilities I

mentioned earlier, though, aremore important; as I said, they provide induc

tive evidence for the theory of karma.The doctrine that the quality of one's

rebirth depends on one's conduct in this life, is not itself peculiarly Buddhist;

but the Buddha claimed, unlike other teachers, to have good 'empirical'

reasons for believing it to be true.

The final kind of knowledge ismore obviously a kind of emancipation;

from ignorance of the basic truths about the world. It is called 'knowledge

of the destruction of the defiling impulses'; and immediately consequent on

the knowledge is the achievement of the destruction itself. It may seem that

since the recluse has already reached the Fourth Meditation there is little

left to destroy; in fact what is added at this stage is a recapitulation and

extension of what has gone before, in the light of the Buddhist philosophical

theories. These theorieswere mentioned earlier in theWay, in the description

of the discipline ofmindfulness; this included seeing all one's constituent parts,

and all one's thoughts and actions, 'as they really were'; i.e. according to

true philosophical generalisations about the world. But at that stage the

recluse had to take these generalisations to some extent on trust; only at this

final stage can he see their truth for himself. The basic philosophical state

ment is that events happen because they are caused, because the appropriate

causal conditions are present: they do not, therefore, come about randomly

or casually nor by the action of fate or some supreme yet personal deity. The

Buddhist formulation of the principle is 'If this is, that comes to be; from

the arising of this, that arises; if this is not, that does not come to be; from

the stopping of this, that is stopped' (M.II 230). The formula is not inter

preted very critically; for example, the theory of karma is a notable applica

tion of it; but the idea that any kind of suffering or misfortune is due to

previous misdoings seems to imply a theory much stronger than 'Every

event has a cause'-namely every event under every description has an

explanation appropriate to that description. Thus if a tree falls on top of

me and injures me, this will need explanation not only as a case of a tree

falling, but also as a case of me being injured. It may be that the formula

could be tightened to get over these difficulties, but the Buddhist writers

did not reach such levels of sophistication. The other basic principle is

that all things are transient. This is sometimes in the laterwriting expressed

in an extreme form: 'there is no Being or not Being, only Becoming'

(Hiriyanna; Outlinesof IndianPhilosophy,p. I42). This presumably means that

the ultimate constituents of the world are not things but events. I know of

no Buddhist argument for the extreme position, except that it fits inwith the

general atomistic approach; the less extreme principle isjustified by common

sense induction; nothing that we know lasts.

This content downloaded from 141.101.201.31 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 14:00:55 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

200 DAVID BASTOW

These two principles are applied in our present context to show in the

first place that there is no reason for believing in the existence of any perma

nent substratum to a man's individuality, any soul, to be reborn. Karma

therefore operates not as punishment or reward for persisting individuals,

but as the natural effect of the behaviour of one collection of constituents

on the circumstances and experiences of some future collection of constituents.

The connection between these people, or 'aggregates', is purely causal; there

is no closer identification, such as the word 'rebirth'might suggest. This is

not, though, the whole story as regards the Buddhist soul teaching and I

shall have to return to it yet again later in the paper. The second application

of the two principles is that both our dispositions and our experiences occur

for some reason, and can be altered or destroyed by altering or destroying

the conditions which bring them about. A man is therefore in the last resort

responsible for every aspect of his life-what he does, what he is, and what he

suffers. The best known summary of Buddhist teaching, the Four Noble

Truths, makes this explicit with respect to his suffering.The word is not

necessarily to be taken in a physical sense; any dis-ease is due to attachment

of some kind, and so can be eliminated by living a life such as that described

in detail above-set out in another formulation as the Fourth Truth; the

Path to the cessation of suffering is the Noble Eightfold Path; which Path

follows quite closely the Way already described. This idea that a man is

responsible for his dispositions and for his experiences has of course been

implicit throughout the whole of theWay; it had therefore to be taken on

trust by aman starting on the course of self-discipline; at the end of theWay

he is able to verify it for himself. The process of verification isnever described;

in theory it seems to have been by some kind of philosophical insight

though as I have already mentioned, common-sense justifications were

occasionally given for heuristic purposes.

The final achievement is just this freedom from the defiling impulses. The

first, that of Lusts, summarises in a schematic way the various kinds of craving

for theworld which have been faced and abandoned earlier in theWay and

adds the impulse to hanker after rebirth in thisworld. Such hankering is to be

resisted firstly because it is obviously an extension of the other cravings, but

also because it is pointless; the kind of rebirth allowed for by the Buddhist

theory of the soul makes nonsense of a man saying 'Iwish to be reborn in

such and such a state'. The second defiling impulse is that of Becomings; to

destroy this is to get rid of the desire for rebirth in any of the heavens. This

desire again is a constraint, as are all such desires, and is again a pointless

one, based on an illusion. The third defiling impulse is that of Ignorance of

the Four Noble Truths with respect to dis-ease or suffering.

A recluse who has destroyed these is an Arahat, one emancipated inmind

and heart (D.I 20I); one who has 'laid down the burden, attained his own

goal, whose fetters of becoming are utterly worn away, who is freed by perfect

This content downloaded from 141.101.201.31 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 14:00:55 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BUDDHIST ETHICS 20I

profound knowledge' (M.I 6). Everything said about this goal of Arahatship,

with the exception of a very few pictorial similes, is by reference to the

progressive achievements of theWay. So it seems that the nature of the

goal can be described only as the emancipation resulting from the various

kinds of self-restraint. The Way and the goal are conceptually interwoven.

One considerable objection to this account should immediately be mentioned.

This is that the goal is the elimination of suffering by the only means

possible, i.e. the destruction of craving leading to victory over rebirth. On

this account the goal is claimed to be conceptually distinct from theWay;

the connection is rather causal and therefore contingent; the Buddha found

in his own experience that the only way to get rid of suffering was to pass

through the various stages of the recluse's Way. This account is the one

suggested by many of the handbooks on Buddhism. It can be answered at

several levels. The accounts of theWay in the Suttas are never introduced

as themethod to achieve freedom from rebirth; but rather as the proper way

to live the higher life, or as an account of true righteousness and truewisdom.

Freedom from rebirth is an Upanisadic goal, which the Buddha adopted,

but although it is not infrequently mentioned in the Suttas the implication

that rebirth as such can be wearisome fits too awkwardly with the Buddhist

soul theory, according to which there is no rebirth of individuals, for it to

be made the central aim of Buddhist striving. The Four Noble Truths regar

ding suffering do seem to support the theory, especially as they are placed

right at the end and therefore the summit of the recluse's achievements; but

it must be remembered that suffering or dis-ease and craving have to be

widely interpreted; craving forworldly things is only one of the Five Hin

drances, and when the fourth meditation is reached ease and dis-ease have

disappeared altogether. It seems that the Four Noble Truths can be seen

either as a statement of the minimal aims of theWay, expressed in terms

everyone can understand, or as an empty formula, tobe filled in appropriately

to the kind of fetter one is striving to get rid of.Whichever this is, the recluse

will think of the bondage to it as being, if not causing, unhappiness, just

because he wants to be but is not yet rid of it-not because of any connexion

with rebirth.

It seems then much more likely that the Buddha and his first followers

thought of theWay as a progressive revelation of the possibilities of self

restraint and the freedom resulting therefrom. To this extent the Buddhist

goal was the same as that of all recluses; self-restraint of some kind, abandon

ment of worldly pleasures and worldly desires, was common to all thosewho

'went forth' to lead the higher life. But the Buddhist would think that the

other recluses had only the vaguest idea of what self-restraint really implied;

it was for this reason that many of them were sidetracked into such useless

practices as asceticism, and self-mortification. The Buddha though saw clearly

that true self-restraint included perfect conduct, but was not exhausted

This content downloaded from 141.101.201.31 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 14:00:55 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

202 DAVID BASTOW

by this; the same principles had to be applied to mental states, and

finally to the desire which had formany been the central idea of the religious

life, that for rebirth in some more fortunate state. With regard to this last

point, it should be mentioned that one element in the confused picture of

the Buddha's attitude to the theory of the soul, is that the questions of the

nature of the soul, and whether an Arahat continued to live after death, were

among the speculative questions which theBuddha refused to answer, saying

that worrying about such things hampered one from attaining the goal. This

may well imply that the rewards of the attainment of Arahatship, if there are

any, are as irrelevant to its true nature, and as likely to confuse the issue, as

are Kant's grocer's profits to themoral worth of his action. This lofty position

is not however held consistently, as will be seen inwhat follows.

Emancipation or freedom are unsatisfactory concepts to put at the centre

of a comprehensive plan for the conduct of one's life; almost any change for

the better in a man's state can be seen as an extension of his freedom. The

term as it stands is evaluative-the change must be one for the better-but

insufficiently descriptive. What the above account of the Buddhist Way

needs, therefore, is a descriptive stiffening of the term, an explanation of why

it is just these kinds of emancipation that are to be sought. Three alternatives

suggest themselves. The first concentrates on the first stage of theWay, that

which describes the ideal of uprightness in conduct, resulting in 'freedom from

danger as far as regards self-restraint in conduct'. The suggestion is that the

emancipation here referred to is simply freedom from immorality; the self

restraint is that necessary to resist temptations towrong-doing. The kinds of

moral behaviour mentioned could be seen as selected to cover, in a schematic

fashion, thewhole field of morality. Abstention from killing is interpreted as

covering compassion, absence of malevolence-in fact the general field of

benevolence. Abstention from stealing and lying cover the field of honesty;

those rules of conduct which do not have immediate utilitarian justification.

Abstention from unchastity is representative of self-regarding morality. This

is not in anyway religiousmorality; theBuddha does not claim any originality

for it. He uses it as common ground between himself and the Brahmans when

arguing against ceremonial and sacrificial activities, and against the four-fold

class-system as determined by birth (Sonadanda Sutta, D.I I44 f.); and

between himself and the lay householder when he makes clear the duties of

a householder (Sigalovada Suttanta, D.III 173 ff.). In the Sutta in which

the Minor Moralities are first described, the fact that the Buddha is praise

worthy in that he lives according to them is seen as something that can be

recognised by non-Buddhists. So there is little doubt that the injunction of

the first stages of theWay can be described without distortion as injunctions

to restrain oneself from the commonly accepted kinds of immorality. One

This content downloaded from 141.101.201.31 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 14:00:55 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BUDDHIST ETHICS 203

may feel that the image of self-restraint is not entirely appropriate here; is it

necessarily the case that one should have to restrain oneself from immorality ?

One answer would be that immorality is always more natural thanmorality,

in that the latter involves, through universalisation, attention to interests

other than one's own. A less subtle reaction is to limit the description of what

the recluse should avoid, to activities which are immoral because they are

pleasant-activities and experiences for which men may be said to crave.

This is interesting because it seems to provide what was lacking in the above

account, namely ameans of relating the injunctions of the first stages to those

of the later stages of theWay. Craving is then distinguished from other forms

of desire in two ways; first that cravings are desires which are the result of

external impulses-external in the sense of being foreign to a man's real

nature. The frequently-used word 'lusts'would in this case indicate their

character. The second important feature of cravings is that it is these desires

which bind one to the kind of lifewhich necessarily brings with it suffering,

grief, lamentation and despair: so, as the Four Noble Truths observe, the

only way to free oneself of suffering is to free oneself of cravings. (This may

or may not refer to rescuing oneself from the wearisome wheel of rebirth,

according to whether the picture of the wheel is thought to be compatible

with the theory of non-self If not, the Truths refer in a commonsense way

to how one can eliminate suffering in this life.) On this account the aim of

theWay is the destruction of craving, i.e. of those desires which the agent

sees as not being part of his true self; first of the simple desires of the flesh,

then as the recluse's vision of his true self becomes clearer, the desires which

defile and corrupt not his actions but his thoughts and states of mind. The

destruction of these cravings will, it is pointed out, have as a result (though

not necessarily as its purpose) the elimination of the suffering towhich they

bind us.

There is, I think, considerable truth in this account, and many texts could

be found to support it. Its weakness is that it does not tell the whole story.

In the first place it fails to do justice to the morality of conduct, already

described. I have said that this is best seen as an attempt to cover the com

monly accepted scope of morality: not without unreasonable distortion can

it be claimed that all the kinds of immorality therementioned are the result

of craving. Rough action, calumny, harsh language, frivolous talk, lying

speech, can hardly be fitted into the category of actions due to desires external

to one's true will. Similarly with the Five Hindrances; the first is certainly

hankering after the world, and its destruction is described as having 'a

heart that hankers not, and purifying one's mind of lusts' (D.I 82). But the

other Hindrances-the corruption of the wish to injure, sloth, worry and

irritability, wavering-fit best into a category wider than craving; loss

of self-control. At a higher level still, the Fourth Meditation is 'a state

of pure self-possession and equanimity, without pain and without ease'

This content downloaded from 141.101.201.31 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 14:00:55 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

204 DAVID BASTOW

not only does the recluse at this stage cease to be attracted to anything;

neither does anything repel him. Once again, self-control seems to be a

more appropriate term, and the emancipation is from lack of self-control.

This; though, only pushes the problem a stage further back; how is the

term 'self-control' to be explained. As it stands, it is as open to variety of

interpretation as 'self-restraint' or 'emancipation'. What is the self,who does

the controlling? A similar term found in the texts is 'self-mastery'; and this

means mastery over those elements which make up the individual, and which

masquerade as the self. Here we have the third attempt to spell out what

was hoped would be the unifying concept of self-restraint. This time the

explication is appropriate to the final stages of the Way, but has little

relevance to the earlier stages. All the elements of the individual person are

to be seen as of no account; 'the instructed disciple disregards material

shape, feeling, perception, dispositions, consciousness; disregarding, he is

dispassionate, through dispassion he is freed' (M.I I78). This goes even

beyond the Kantian proscription of interest and inclination as instigators

of action; reason, which in Kant's account remains, was quenched in the

Second Meditation. One cannot say that the real Self, the Pure Ego, remains,

as would be possible in theVedanta tradition, for there is no real Self. The

final emancipation is from the bondage of all that is impermanent, and

therefore not self; but since everything is impermanent, the emancipation is

absolute.

The final picture contains an incoherence which seems irreducible. The

Arahat is one who has mastered the Minor Moralities and is therefore

compassionate and kind-the Buddha himself shows himself to be compassion

ate on several occasions in his life; and in particular in the mythological

description of how he decided, on reaching Buddhahood, to live on earth in

order to preach his message to those who were in need of it (M.I 213). Yet

the goal of the recluse's Way includes the dispassionate disregard of all

feeling. To put the point in more general terms; the earlier stages of the

Way can be seen as progressive explorations of the notion of self-control

which we are familiar with, and which we may well approve of. But in the

later stages all possibility disappears of distinguishing between those actions,

thoughts, motives of which one may approve and those of which one may

disapprove-those which ought to be suppressed, and those which ought to

replace those suppressed. No recognisably human activities, mental or

physical, remain.

The final question is, how is all this related to morality. (I think it is

important to notice that this question can come only at the end of such a

relatively detailed survey of the relevant aspects of the religion concerned;

and the more one knew about the religion, the better placed one would be

This content downloaded from 141.101.201.31 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 14:00:55 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BUDDHIST ETHICS 205

to answer the question.) The Buddha certainly recommends aWay and a

Goal to his followers, but is the recommendation a moral one, and if so, how

is it justified? To take the second question first; I have mentioned the

possibility that the real justification of theWay is that it eliminates suffering;

my conclusion was that this fails to do justice to the composition and des

cription of the stages of theWay, and to the description of the goal. It is

true and important that one who has reached the goal has eliminated

suffering; and this fact is often used to attract people to theWay, but it is

not the heart of thematter. A more promising suggestion is that theWay is

justified by the implied argument that the kinds of self control and freedom

from bondage described in the first stages have their proper extension and

culmination in the later and final stages. This thesis is importantly supported

by the Buddhist teaching about the self or soul. But it has been one of the

main purposes of my paper to argue that the assumed continuity between

the stages is seriously open to question; and even if the discontinuity is

surmountable, it is hardly sufficient to justify thewhole Way by reference to

the attractiveness of the early stages. There should be some justification of

the goal itself. The orthodox reply here would be that only when one has

reached the higher stages of achievement can one appreciate them at their

proper value; to this extent theWay must be taken on trust by the beginner.

It remains true that Buddha is notproposing a completely new and ultimate

evaluative principle; he describes the views which any man, and in particular

the recluse, will be led to if he takes his present principles seriously. These

principles would importantly include not allowing oneself to be controlled

by psychological forceswhich are in some sense external to one's real nature;

this principle may be based on or confirmed by the belief that in so doing a

man is getting at the ultimate truth about himself. This latter justification

carries over well to the later stages of theWay; the final freedom is always

coupled with knowledge of this freedom and of its significance.

This brings us to the other question, of whether these principles aremoral;

whether theWay can be described as a set of moral injunctions, and the

goal as a moral ideal. It seems in fact that little depends on such a classifi

cation, provided the principles' status is clear.

I. They presuppose the mastery of morality in the normal sense. This of

course raises the question of whether this kind of morality can be mastered,

and if not why not.

2. They are not incumbent on every man; the Buddha does not say that

it is a man's duty to undertake theWay. His attitude is rather that any

recluse who having heard the Truth follows some other kind of religious life

must be stupid or blind. Similarly a householder's life may be of profit,

but much greater and sweeter is the profit of theWay. The situation may be

similar to that in some aesthetic matters; appreciation of chamber music isnot

every man's duty, but may perhaps be expected of people of a certain type.

This content downloaded from 141.101.201.31 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 14:00:55 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

206 DAVID BASTOW

3. They are concerned, unlike say utilitarianism, solely with the way

farer's own states. This suggests that the Buddha was describing the way

to the good life; the morally perfect life was certainly thought to be part of

the good life, but a part which could be disposed of before one moved to

higher things.What is perhaps the common-sense view was accepted, that

morality deals primarily with one's relations with other people, and therefore

with one's actions; but therewere thought to be goals more important than,

though not conflicting with, such morality. The question which arises here

iswhether pursuing these goals is in fact compatible with mastery of conven

tional morality. I have suggested that there may be conceptual incompati

bility; even if this is not the case, the practical difficulties of combining the

two kinds of goal may well be insurmountable.'

1 I do not deal in this paper with Buddhist teaching on the layman's morality, though this is

certainly worth discussing. The general point of view from which this paper is written is described

inmy 'The Principles of the Philosophy of Religion' (PhilosophicalQuarterly,July, I969).

This content downloaded from 141.101.201.31 on Sat, 28 Jun 2014 14:00:55 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- A Guide - To - Stoic - Living - Keith SeddonDocument196 pagesA Guide - To - Stoic - Living - Keith Seddonstrayl1ght100% (10)

- Buddhism in 10 Steps (Ebook)Document51 pagesBuddhism in 10 Steps (Ebook)Sarang BhaisareNo ratings yet

- What Is Meditation ?Document33 pagesWhat Is Meditation ?JonathanNo ratings yet

- Aspects of Spiritual Practice in Early YogacaraDocument33 pagesAspects of Spiritual Practice in Early YogacaraGuhyaprajñāmitra3No ratings yet

- The Psychology of Worldviews: Mark E. Koltko-RiveraDocument56 pagesThe Psychology of Worldviews: Mark E. Koltko-RiveraPablo SeinerNo ratings yet

- Worldview Defhistconceptlect PDFDocument50 pagesWorldview Defhistconceptlect PDFbilkaweNo ratings yet

- Rebirth and The Western BuddhistDocument93 pagesRebirth and The Western BuddhistPilar ValerianoNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Buddhism: Four LecturesDocument63 pagesFundamentals of Buddhism: Four LecturesWinNo ratings yet

- BST 203-Christian WorldviewDocument10 pagesBST 203-Christian WorldviewAdaolisa IgwebuikeNo ratings yet

- Capriles E. - Beyond Mind. Steps To A Met A Trans Personal Psychology IJTS 2000Document52 pagesCapriles E. - Beyond Mind. Steps To A Met A Trans Personal Psychology IJTS 2000Barbora ChvatalovaNo ratings yet

- Theravada Buddhism02Document3 pagesTheravada Buddhism02Kenn KennNo ratings yet

- Rimé and Dzogchen Article DerocheDocument30 pagesRimé and Dzogchen Article DerocheSara MessiNo ratings yet

- Reflections On Suffering and Happiness: The Centered WheelDocument4 pagesReflections On Suffering and Happiness: The Centered WheelAutumn HughesNo ratings yet

- BST 201 Christian Worldview 1Document30 pagesBST 201 Christian Worldview 1enochnanfwangNo ratings yet

- Epoche and Śūnyatā: Skepticism East and WestDocument24 pagesEpoche and Śūnyatā: Skepticism East and WestJohn HaglundNo ratings yet

- Buddhist Philosophy and Its Europen ParallelsDocument16 pagesBuddhist Philosophy and Its Europen ParallelsDang TrinhNo ratings yet

- A Little Disillusionment Is A Good ThingDocument16 pagesA Little Disillusionment Is A Good ThingCTSNo ratings yet

- 9277 9952 1 PB PDFDocument53 pages9277 9952 1 PB PDF张晓亮No ratings yet

- Philosophical Foundations in Psychology AssignmentDocument16 pagesPhilosophical Foundations in Psychology Assignmentratheeanushka16No ratings yet

- YogaandecologyDocument12 pagesYogaandecologyalinesanyogaNo ratings yet

- Written Report in Sts Group 2Document5 pagesWritten Report in Sts Group 2aries sangalangNo ratings yet

- Consciousness and Self-ConsciousnessDocument21 pagesConsciousness and Self-Consciousnessantonio_ponce_1No ratings yet

- STEPHAN SCHWARTZ: Nonlocal Consciousness and The Anthropology of Religion.Document5 pagesSTEPHAN SCHWARTZ: Nonlocal Consciousness and The Anthropology of Religion.Michel BLANCNo ratings yet

- Jiddu Krishnamurthis Perspective On EducDocument13 pagesJiddu Krishnamurthis Perspective On EducMaria Lancelot maria.No ratings yet

- The Essence of HumanismDocument7 pagesThe Essence of Humanismcliodna18No ratings yet

- The Path To Liberation: Reconciling The Theory of Interdependent Origination With Free WillDocument9 pagesThe Path To Liberation: Reconciling The Theory of Interdependent Origination With Free WillGuiller Martin Cedric GabaoenNo ratings yet

- Mysticism and Theravada MeditationDocument25 pagesMysticism and Theravada MeditationMagdalena SpytNo ratings yet

- Buddhist Ethics - Oxford HandbooksDocument18 pagesBuddhist Ethics - Oxford HandbooksalokNo ratings yet

- Epoche and Śūnyatā - Skepticism East and WestDocument24 pagesEpoche and Śūnyatā - Skepticism East and WestKadag LhundrupNo ratings yet

- Will Focus Emphasizes: The Bhagavadgita and MoralityDocument9 pagesWill Focus Emphasizes: The Bhagavadgita and MoralityFa-ezah WasohNo ratings yet

- Spiritual Advice For Dharma Practitioners of This Degenerate AgeDocument3 pagesSpiritual Advice For Dharma Practitioners of This Degenerate AgeDudjomBuddhistAssoNo ratings yet

- 40 Studies On The Tantras The Spiritual Heritage of India: The Tantras 41Document7 pages40 Studies On The Tantras The Spiritual Heritage of India: The Tantras 41propernounNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Jainism 101Document27 pagesIntroduction To Jainism 101heenamodiNo ratings yet

- On Initiation by Peter Mark AdamsDocument12 pagesOn Initiation by Peter Mark AdamsPeter Mark AdamsNo ratings yet

- Searching For The Extended Self: Parapsychology & SpiritualityDocument23 pagesSearching For The Extended Self: Parapsychology & SpiritualityBryan J WilliamsNo ratings yet

- MokaDocument17 pagesMokaLuis Tovar CarrilloNo ratings yet

- (Asian Folklore Studies Vol. 37 Iss. 1) Francisco R. Demetrio - The Shaman As Psychologist (1978) (10.2307 - 1177583)Document20 pages(Asian Folklore Studies Vol. 37 Iss. 1) Francisco R. Demetrio - The Shaman As Psychologist (1978) (10.2307 - 1177583)Lynnlin GamingNo ratings yet

- Ajahn Brahm, Dependent Origination (2002)Document23 pagesAjahn Brahm, Dependent Origination (2002)David Isaac CeballosNo ratings yet

- Icon by IconDocument6 pagesIcon by IconpropernounNo ratings yet

- America Smiles On The Buddha-Part 2Document3 pagesAmerica Smiles On The Buddha-Part 2frankiriaNo ratings yet

- Religion Compass Volume 3 Issue 1 2009 (Doi 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00120.x) June McDaniel - Religious Experience in Hindu TraditionDocument17 pagesReligion Compass Volume 3 Issue 1 2009 (Doi 10.1111/j.1749-8171.2008.00120.x) June McDaniel - Religious Experience in Hindu TraditionNițceValiNo ratings yet

- Confucianism, Buddhism, HinduismDocument8 pagesConfucianism, Buddhism, HinduismKoRnflakes100% (1)

- The Psychedelic Experience A Manual Based On The Tibetan Book of The DeadDocument61 pagesThe Psychedelic Experience A Manual Based On The Tibetan Book of The DeadAntonella Wagner100% (1)

- FinalDocument6 pagesFinalapi-355717370No ratings yet

- Kalu Rinpoche Ocean of AttainmentDocument90 pagesKalu Rinpoche Ocean of AttainmentTùng Hoàng100% (1)

- Scientology and Religion by Christiaan VonckDocument10 pagesScientology and Religion by Christiaan VoncksirjsslutNo ratings yet

- A Primer on Applied Feel Theory: Rethinking the Relationship with Society (The Equilibrium Texts, Vol. 2)From EverandA Primer on Applied Feel Theory: Rethinking the Relationship with Society (The Equilibrium Texts, Vol. 2)No ratings yet

- Qautrivium of FourDocument84 pagesQautrivium of FourNner G AsarNo ratings yet

- Module - 1 RRES GE110 Introduction Definition of TermsDocument9 pagesModule - 1 RRES GE110 Introduction Definition of TermsAngelica PallarcaNo ratings yet

- SCHMITHAUSEN - The Problem of The Sentience of Plants in Earliest BuddhismDocument128 pagesSCHMITHAUSEN - The Problem of The Sentience of Plants in Earliest BuddhismEugen Ciurtin100% (3)

- Buddha'S Journey To Enlightenment: Aryan SinghDocument10 pagesBuddha'S Journey To Enlightenment: Aryan SingharyanNo ratings yet

- Zureta Reflection PaperDocument5 pagesZureta Reflection PaperYsabella ZuretaNo ratings yet

- The Jains and Their CreedDocument17 pagesThe Jains and Their CreedvitazzoNo ratings yet

- Stress Management FinalDocument66 pagesStress Management FinalBeniram KocheNo ratings yet

- Freedom East and West by J L ShawDocument17 pagesFreedom East and West by J L Shawsatyagraha0No ratings yet

- Buddhism and Immortality: The view of the Immortality of ManFrom EverandBuddhism and Immortality: The view of the Immortality of ManNo ratings yet

- Guide To Stoic Living PDFDocument196 pagesGuide To Stoic Living PDFgaston100% (1)

- 5 Vasundhara Iyer Philosophy AssignmentDocument2 pages5 Vasundhara Iyer Philosophy AssignmentIyer VasundharaNo ratings yet

- ITWRBS Final Examination ReviewerDocument7 pagesITWRBS Final Examination Reviewerprecious DalumpinesNo ratings yet

- Some Popular Symbols in Myanmar CultureDocument10 pagesSome Popular Symbols in Myanmar Cultureoat awNo ratings yet

- Examine The Origins of Commentarial Literature in India 1Document9 pagesExamine The Origins of Commentarial Literature in India 1Wimalagnana RevbNo ratings yet

- Group 2Document30 pagesGroup 2Zyra DimaanoNo ratings yet

- Sanchi Stupa GatewaysDocument64 pagesSanchi Stupa Gateways520219005 AnweshaMrokNo ratings yet

- The Lotus SutraDocument20 pagesThe Lotus SutraMike PazdaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement On BuddhismDocument8 pagesThesis Statement On Buddhismjoysmithhuntsville100% (2)

- Bus Ethics q3 Mod5 Impact of Belief System Final - Compress 1Document19 pagesBus Ethics q3 Mod5 Impact of Belief System Final - Compress 1Mharlyn Grace Mendez100% (1)

- Eastern PhilosophiesDocument6 pagesEastern PhilosophiesLyza Sotto ZorillaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - BuddhismDocument9 pagesLesson 2 - BuddhismVictor Noel AlamisNo ratings yet

- Siddhartha (Hermann Hesse) (Z-Library)Document112 pagesSiddhartha (Hermann Hesse) (Z-Library)otimasvreiNo ratings yet

- Different VadasDocument3 pagesDifferent VadasGabe DiscourseNo ratings yet

- G7 - Chapter 05 - Short NotesDocument3 pagesG7 - Chapter 05 - Short NotesYenuka KannangaraNo ratings yet

- WRBS11 Q2 Mod5 Comparative Analysis of Dharmic ReligionsDocument22 pagesWRBS11 Q2 Mod5 Comparative Analysis of Dharmic ReligionsJerryNo ratings yet

- Ancient History MCQ PDF by Study Like A ProDocument44 pagesAncient History MCQ PDF by Study Like A ProNirmal SharmaNo ratings yet

- A Gulim La SuttaDocument13 pagesA Gulim La SuttaNiran ChueachitNo ratings yet

- Walking The Tightrope - David YoungDocument177 pagesWalking The Tightrope - David YoungRidma Chathu (Rimi)No ratings yet

- Chapter 5951 - 6000 Spanish NamesDocument184 pagesChapter 5951 - 6000 Spanish NamesAkmal ShahbazNo ratings yet

- Dimensions of The Sacred An Anatomy of The Worlds Beliefs (Ninian Smart) (Z-Library) - CompressedDocument100 pagesDimensions of The Sacred An Anatomy of The Worlds Beliefs (Ninian Smart) (Z-Library) - CompressedEd VulcaoNo ratings yet

- Ancient India and China Test ReviewDocument2 pagesAncient India and China Test Reviewelmoukademtania99No ratings yet

- Rinzai ZenDocument13 pagesRinzai ZenOlly SuttonNo ratings yet

- Buddhism & Jainism AssignmentDocument2 pagesBuddhism & Jainism AssignmentNazmul HasanNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 12 History Thinkers Beliefs and Buildings Cultural DevelopmentsDocument4 pagesCBSE Class 12 History Thinkers Beliefs and Buildings Cultural DevelopmentsRashi LalwaniNo ratings yet

- Senior High School Introduction To World Religion and Belief System School Year 2022-2023Document91 pagesSenior High School Introduction To World Religion and Belief System School Year 2022-2023Vee SilangNo ratings yet

- Enmei JukkuDocument11 pagesEnmei JukkuEsteban DonadoNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Self - 061558Document27 pagesUnderstanding The Self - 061558Reyward FelipeNo ratings yet

- Ajahn Brahmali Buddhist CosmologyDocument24 pagesAjahn Brahmali Buddhist CosmologyMinato NamikazeNo ratings yet

- World Religion PDF World Religion PDFDocument35 pagesWorld Religion PDF World Religion PDFDeina PurgananNo ratings yet

- Theravada Buddhisem BasicDocument96 pagesTheravada Buddhisem BasicRidmini Niluka PunchibandaNo ratings yet