Professional Documents

Culture Documents

03 Lomozik Creep-Resisting Structural Steels For The Power Industry-The Past and The Present Time

03 Lomozik Creep-Resisting Structural Steels For The Power Industry-The Past and The Present Time

Uploaded by

Tibor KeményOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

03 Lomozik Creep-Resisting Structural Steels For The Power Industry-The Past and The Present Time

03 Lomozik Creep-Resisting Structural Steels For The Power Industry-The Past and The Present Time

Uploaded by

Tibor KeményCopyright:

Available Formats

Mirosław Łomozik

Creep-resisting structural steels for the power industry –

past and present

Abstract: The article provides information about the condition of domestic and

global power industries in the context of the thermal efficiency of existing pow-

er systems. The work also presents the tendencies in the development of power

systems operating at supercritical steam parameters. The article shows the basic

requirements for advanced structural materials intended for use in power in-

dustry machinery and also presents diagrams showing the development of suc-

cessive creep-resisting steel generations with the ferritic base and of austenitic

steels. The article provides approximate chemical compositions of selected steels

from individual groups differing in chromium content. Attention is also given to

the dependence of welding process technological parameters for joining steels

designed for higher temperatures on the chemical composition of the steels and

the thickness of the components being welded. The conclusion contains a state-

ment that the continuous introduction of new steel grades on the market is ac-

companied by the continuous use of steels belonging to older generation grades

such as 13CrMo4-5 and 10CrMo9-10 ones.

Keywords: power industry, creep-resisting steel, supercritical parameters;

Introduction in newly built power units even to 42-46%. The

This study is the result of work based on ac- thermal efficiency of power plants can be im-

cessing available scientific and popular-science proved by using the supercritical parameters of

publications, mainly from the early years of the steam, i.e. a temperature of over 540°C and a

21st century, related to tests of structural steels pressure of 18 MPa. It is estimated that increas-

for the power industry and the developmental ing steam temperature from 540°C to 650°C and

progression of these steels. pressure from 18 MPa to 30 MPa enables a 10%

Since electric energy started being generated increase in the efficiency of power generating

on an industrial scale at the end of 19th century, equipment [4].

mainly using coal, the principal parameter de- The potential of conventional power engi-

fining the modernity of a unit or a given tech- neering is made by power plants and combined

nology has been its thermal efficiency. heat and power plants using mainly brown

According to publicised data [3] the net effi- and carbon coal. As regards the generation of

ciency of the best Polish power plants amounts electric energy, power plants can be divided

on the average to 33%, in the world to 36%, and into steam power plants and those equipped

dr hab. inż. Mirosław Łomozik (PhD hab. Eng.), professor extraordinary at Instytut Spawalnictwa in Gliwice,

Testing of Materials Weldability and Welded Constructions Department

32 BIULETYN INSTYTUTU SPAWALNICTWA No. 5/2013

presently

Thermal efficiency, %

supercritical in the power industry would be im-

50 IGCC

possible without the development of

IGFC

40 integrated

fuel cells

structural materials, mainly steels, in-

30 pressure

fluidised

tended for operation at a heightened

supercritical

20

first

power boilers boilers temperature.

plant conventional boilers,

global standard

10 steam boilers Division of structural steels

0 intended for operation at

1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 2020 increased temperature

Year

Creep-resisting steels include a large

Fig. 1. Development of electric energy generation technologies

based on burning coal [1-3] group of structural steel grades differ-

ing in their chemical composition with

with gas turbines. The continual popularity and a microstructure obtained as a result of heat

continuous growth of investments connected treatment and intended use for a specific range

with the development of steam power plants is of power systems.

reflected by the results of surveys and investi- The development of thermal power engi-

gations monitoring the development of such neering towards the use of higher operating pa-

structures in the world (Fig. 2). It is possible to rameters (temperature and pressure), and thus

observe an interest in power units in operation obtaining a greater efficiency, depends on the

with supercritical parameters and projects availability of appropriate structural materials.

and investments related to units with

a power of 400-1000 MW for a steam 700°C / 720°C / 35 MPa

Yuhuan, 2x1050 MW,

600°C/600°C/26 MPa

pressure of 25-30 MPa and an operating

600°C / 620°C / 29 MPa

temperature in the range 580-610°C,

carried out mainly in the USA and 560°C / 580°C / 27 MPa

Japan. Currently implemented research 540°C / 560°C / 25 MPa Europe

Japan

projects involve even higher operating USA

China

538°C / 538°C / 16,7 MPa WaiGaiQiao, 2x980 MW,

parameters in which temperature is 538°C/566°C/25 MPa

restricted within the range 620-650°C 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020

(though sometimes reaching 700°C) Fig. 2. Forecast development of steam power plants in Europe,

and a pressure exceeding 30 MPa [3]. Japan, USA and China until 2020 [5]

An example of the development of 55 nickel alloys

carbon coal burning power units in (35MPa, >700°C)

Germany is presented in Figure 3. 50

Net efficiency, %

austenitic steels

The development and use of super- (29 MPa, 600°C)

critical parameters has enabled the con- 45 ferritic-martensitic steels

(26 MPa, 545°C)

struction of power units having net

thermal efficiency reaching 48% which 40

simultaneously reduce the emission of

35

noxious pollutants to the atmosphere

and cut down electric energy genera-

30

tion costs. 1950 1970 1990 2010 2030

The aforesaid development of tech- start-up date

nologies concerned with the manu- Fig. 3. Development of carbon coal burning power units

facturing and operating of equipment in Germany [6-8]

No. 5/2013 BIULETYN INSTYTUTU SPAWALNICTWA 33

In the boiler part of a power unit the most im- divided into the following:

portant elements include tight walls made of a) ferritic steels (ferritic-pearlitic, ferritic-bai-

thin-walled pipes, steam superheaters and re- nitic, bainitic and martensitic),

superheaters, as well as thick-walled live steam b) austenitic steels.

pipelines and chambers. Requirements for each The highest operating temperature of CMn-

of the enumerated elements include thermal type unalloyed steels is assumed to be within the

formability, weldability and heat treatment, as range of 400-450°C. For molybdenum steels and

well as [9, 10] the following: 0.5Mo, 1Cr-0.5Mo, 2.25Cr-1Mo and Cr-Mo-V

• proper mechanical properties, aimed to en- type chromium-molybdenum steels, depend-

sure long-lasting operation at a high temper- ing on the grade, operating temperature is con-

ature and under pressure (creep strength) tained within the range from 540°C to 565°C.

taking into account the cyclicity of loads (re- Steels having a martensitic microstructure with

sistance to low-cycle thermal fatigue), a carbon content of 0.07-0.22%, a chromium

• proper oxidation resistance, so that the content of 8-12% and containing molybdenum,

growth of an oxide film inside the pipes does tungsten, nickel, niobium, vanadium and bo-

not cause an excessive increase in the temper- ron additions can be used up to a temperature

ature of the pipe walls, of 600°C, whereas steels with a cobalt addition

• proper corrosion resistance in order to ensure are expected to be used up to a temperature of

the smallest possible material losses from the 620°C [11]. Austenitic steels can be used success-

furnace side. fully up to a temperature of 700°C.

Due to the microstructure and operat- Corrosion and oxidation resistance at a

ing temperature creep-resisting steels can be heightened temperature depends mainly on

Generation 1 Generation 2 Generation 3 Generation 4

Creep strength for 100 000 hours at a temperature of 600°C and stress, MPa

35 60-80 80-100 120-140 180

-C +W

2,25Cr-1Mo +V 2,24Cr-1,6WVNb

+Mo +Nb

ASME T22 ASME T23, 7CrWVNb9-6

STBA-24 2,25Cr-1MoV -C +Mo HCM2S

+Ti +B

10CrMo9-10 2,24Cr-1MoVTiB

+Co

10H2M +Mo

+B ASME T24, 7CrMoVTiB10-10 9Cr-VNbBN

CB2

- -C FB2 9Cr-WCoVLowC

20H8M2B -Mo

9Cr-1Mo +W PB2 -C MARBN

+Mo

ASME T9 9Cr-0,5Mo-1,8WVNb +B

STBA-26 9Cr-2Mo +W

Optimized V i Nb

NF 616

X10CrMo91 +Co

H9M +V HCM9M, STBA-27 ASME T92

+Nb

+Mo STBA-29 9Cr-WCoVNbB

9Cr-1MoVNb 9Cr-1MoVNb +N X10CrWMoVNb9-2

+Mo MARB2

+Nb TEMPALOY F-9 ASME T91

9Cr-1Mo-1WVNbN

+V STBA-28

9Cr-2MoVNb X10CrMoVNb9-1 E911

H9AMFNb X11CrMoWVNb9-1-1 12Cr-2W-2CoVNbBN

EM12, NFA 49213

VM12-SHC

+Mo

X12CrCoWVNb12-2-2

12Cr 12Cr-0,5Mo 12Cr-0,5Mo-2WVNb

+N

-Mo TB12

AISI 410 +W 12Cr-2,6W-2,5CoVNbB

+Mo -C -Mo

+V +W

+W +W

+Co

NF12

+W +Nb +Cu -B

12Cr-1MoV 12Cr-1MoWV 12Cr-1Mo-1WVNb 12Cr-0,5Mo-2WCuVNb 12Cr-3W-3CoVNb

HT91 HT9 HCM12 HCM12A SAVE12

X20CrMoV121 X20CrMoWV121 SUS410J2TB ASME T122

20H12M1F SUS410J3TB

Fig. 4. Scheme of development of ferritic steels intended for operation at heightened temperature [12, 13]

34 BIULETYN INSTYTUTU SPAWALNICTWA No. 5/2013

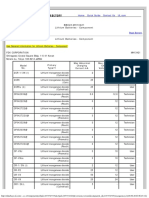

Table 1. Chemical composition of ferritic steels intended for operation at heightened temperatures [11, 14-22]

Element content,%

Steel

C Mn Si P S Cr Ni Mo V Ti Nb W Co Cu B Al N

Steels of content from approximately 0.5 to 2.25% Cr

T22 0,05 0,30 max. max. max. 1,90 0,87 max. ≤

- - - - - - - - - - 0,25 -

(10CrMo9-10) 0,15 0,60 0,50 0,025 0,025 2,60 1,13 0,040 0,012

0.12 0.40 0.17 max. max. max. max. 0.25 max. max. max. max. max. max.

16Mo3 - - -

0.035 0.035 0.30 0.30

-

0.02 0.05 0.01 0.10 0.10

0.30 -

0.10

-

0.20 0.90 0.37 0.35

0.08 0.40 0.10 max. max. 0.70 max. 0.40 max. max. max max.

13CrMo4-5 - - -

0.025 0.010

-

0.40

-

0.10 0.05

-

0.10

- 0.30 -

0.10

-

0.18 1.00 0.35 1.15 0.60

0.10 0.40 0.15 max. max. 0.30 max. 0.50 0.22 max. max.

14MoV63 - - -

0.040 0.040

-

0.30

- - - - - -

0.25

-

0.020

-

0.18 0.70 0.35 0.60 0.65 0.35

0.04 0.10 max. max. max. 1.90 max. 0.05 0.20 0.005 0.02- 1.45 max. max. 0.001 max. max.

T/P23 - -

0.50 0.030 0.010

-

0.40

- - -

0.08

-

0.10 0.30

-

0.03 0.03

0.10 0.60 2.60 0.30 0.30 0.060 1.75 0.006

0.05 0.30 0.15 max. max. 2.20 0.90 0.20 0.05 0.002

T/P24 - - -

0.020 0.010

- - - - - - - - - - 0.02 0.010

0.10 0.70 0.45 2.60 1.10 0.30 0.10 0.007

Steels of content of approximately 9% Cr

max. 0.30 0.25 max. max. 8.00 0.90 max.

H9M 0.12

- -

0.035 0.030

- - - - - - - -

0.30

- - -

0.60 1.00 10.00 1.20

max. 0.30 max. max. max. 8.00 1.80

HCM9M 0.08

-

0.05 0.03 0.03

- - - - - - - - - - - -

0.70 10.00 2.20

0.08 0.30 0.20 max. max. 8.00 0.85 0.18 0.06 0.03

T/P91 - - -

0.020 0.010

- 0.40 - - - - - - - - 0.04 -

0.12 0.60 0.50 9.50 1.05 0.25 0.10 0.07

0.09 0.30 0.10 max. max. 8.50 0.10 0.90 0.18 0.060 0.90 max. 0.050

E911 - - -

0.020 0.010

- - - - - - - - -

0.006

- -

0.13 0.60 0.50 9.50 0.40 1.10 0.25 0.100 1.10 0.090

T/P92 0.07 0.30 max. max. max. 8.50 max. 0.30 0.15 0.040 1.50 0.001 0.030

- - - - - - - - - - - 0.04 -

(NF616) 0.13 0.60 0.50 0.020 0.010 9.50 0.40 0.60 0.25 0.090 2.00 0.006 0.070

0.12 0.30 0.05 max. max. 9.00 0.10 1.40 0.18 0.04 1.20 0.006 0.005 0.015

PB2 - - -

0.009 0.003

- - - - 0.003 - - - 0.10 - - -

0.14 0.40 0.10 9.50 0.20 1.60 0.22 0.065 1.40 0.010 0.010 0.030

0.076 0.49 0.30 max. max. 8.88 0.19 0.049 2.85 3.00 0.0132 0.0015

MARBN - - -

0.020 0.010

- - - - - - - - - - - -

0.081 0.51 0.31 9.08 0.20 0.055 3.07 3.03 0.0150 0.0650

Steels of content of approximately 12% Cr

X20Cr- 0.17 max. max. max. max. 10.00 0.30 0.80 0.25

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

MoV121 0.23 1.00 0.50 0.035 0.035 12.50 0.80 1.20 0.35

max. max. max. max. max. 11.00 0.80 0.20 max. 0.80

HCM12 0.14 0.70 0.50 0.030 0.030

- - - - -

0.20

- - - - - -

13.00 1.20 0.30 1.20

0.07 max. max. max. max. 10.00 max. 0.25 0.15 0.04 1.50 0.30 max. max. 0.040

HCM12A -

0.70 0.50 0.015 0.001

-

0.50

- - - - - - -

0.005 0.040

-

0.14 12.50 0.60 0.30 0.10 2.50 1.70 0.100

0.10 max. max. max. max. 11.00 0.70 0.40 0.15 0.04 1.60 0.04

TB12 -

0.50 0.04 0.020 0.010

- - - - - - - - - - - -

0.15 13.00 1.00 0.60 0.25 0.09 1.90 0.09

max. max. max. max. max. max.

NF12 0.08 0.50 0.05 0.020 0.010

11.50

0.50

0.15 0.20 - 0.07 2.6 2.5 - 0.004 - 0.05

0.10 0.15 0.40 max. max. 11.0 0.10 0.20 0.20 0.005 0.030 1.30 1.40 0.003 0.030

VM12-SHC - - -

0.020 0.010

- - - - - - - - 0.25 - 0.02 -

0.14 0.45 0.60 12.0 0.40 0.40 0.30 0.018 0.080 1.70 1.80 0.006 0.070

No. 5/2013 BIULETYN INSTYTUTU SPAWALNICTWA 35

T23, T24

the chromium content of a steel. In turn, ap-

VM12-SHC, X20

propriately high creep strength of ferritic steels P92, E911

is obtained due to the microstructure of tem- P91

pered martensite and additions of strongly car- Nickel alloys

bide-forming elements such as molybdenum, Super 304H

niobium, vanadium and tungsten [4]. A scheme P23, P24

of the development of ferritic steels is present-

10CrMo9-10

ed in Figure 4, and the chemical composition 16Mo3, 13CrMo4-5

of the most popular steels of this group is pre- unalloyed steels

sented in Table 1.

parameters window

An extremely important problem for weld-

Fig. 5. Dependence of range of steel welding technologi-

ing practice is the deteriorating weldability of cal parameters for operation at heightened temperatures

structural steels along with an increase in the on chemical composition and assortment of steel (wall

content of alloying elements manifested not thickness) [23]

only by the necessity of taking safety precau-

tions during welding, such as pre-heating, mon- 6, and the chemical composition of new gen-

itoring interpass temperature during welding eration steels used in the production of power

and the use of post-weld heat treatment (PWHT) boilers is presented in Table 2.

of joints, but first of all by constricting the rang- The National Institute for Materials Science

es of welding process technological parameters, in Japan has developed a prototypical steel

as presented in Figure 5. In turn, the develop- named MARBN (MAR - martensite, B - boron, N

ment of austenitic steels is presented in Figure - nitrogen) [25] as an alternative to the P92 steel.

Table 2. Chemical composition of austenitic steels used in power industry [10, 24]

Steel Steel designation according to Element content in%

group ASME JIS C Mn Si Cr Ni Mo V Ti Nb W B Other

TP304H SUS304HTB 0.08 1.6 0.4 18.0 8.0 - - - - - - -

3.00 Cu

Super 304H SUS304J1HTB 0.10 0.8 0.2 18.0 9.0 - - - 0.40 - -

0.10 N

TP321H 321FHTB 0.08 1.6 0.6 18.0 10.0 - - - - - - -

18Cr-8Ni TEMPALOY A-1 SUS321J1HTB 0.12 1.6 0.6 18.0 10.0 - - 0.08 0.10 - - -

TEMPALOY AA-1 SUS321J2HTB 0.12 1.6 0.6 18.0 10.0 - - 0.10 0.20 - 0.002 3.00 Cu

TP316H SUS316HTB 0.08 1.6 0.6 18.0 12.0 2.5 - - - - - -

TP347H TP347HTB 0.08 1.6 0.6 18.0 10.0 - - - 0.80 - - -

TP347HFG - 0.08 1.6 0.6 18.0 10.0 - - - 0.80 - - -

17-14CuMo - 0.12 0.7 0.5 16.0 14.0 2.0 - 0.30 0.40 - 0.006 3.00 Cu

15Cr-15Ni

Esshete 1250 - 0.12 6.0 0.5 15.0 10.0 1.0 0.2 0.06 1.00 - - -

TP310 SUS310TB 0.08 1.6 0.6 25.0 20.0 - - - - - - -

TP310NbN (HR3C) 310J1TB 0.06 1.2 0.4 25.0 20.0 - - - 0.45 - - 0.20 N

Alloy 800H NCF800HTB 0.08 1.2 0.5 21.0 32.0 - - 0.50 - - - 0.40 Al

20-25Cr TEMPALOY A-3 SUS309J4HTB 0.05 1.5 0.4 22.0 15.0 - - - 0.70 - 0.002 0.15 N

NF709 SUS310J2TB 0.15 1.0 0.5 20.0 25.0 1.5 - 0.10 0.20 - - -

3.00 Cu

SAVE25 - 0.10 1.0 0.1 23.0 18.0 - 1.5 - 0.45 1.5 -

0.20 N

High CR30A - 0.06 0.2 0.3 30.0 50.0 2.0 - 0.20 - - - 0.03 Zr

content of

HR6W - 0.08 1.2 0.4 23.0 43.0 - - 0.08 0.18 6.0 0.003 -

Cr and Ni

36 BIULETYN INSTYTUTU SPAWALNICTWA No. 5/2013

Addition W (74) Heat treatment (58)

-C 18Cr10NiNb

18Cr9NiWVNb

18Cr8Ni, C<0,08 XA704 ASME TP347HFG

ASME TP347W (40-60)

+Ti AISI 304 Optimisation of chemical

H Grade composition (58) Addition Cu (76)

18Cr10NiTi 0,04-0,10C

AISI 321 18Cr10NiNbTi 18Cr10NiCuTiNb

18Cr8Ni +Nb AISI 304H

AISI 321H TEMPALOY A-1 TEMPALOY AA-1

AISI 302 18Cr10NiNb AISI 347H SUS321J1HTB ASME TP321HCuNb

AISI 347 AISI 316H SUS321J2HTB

+Mo (75) Addition Cu (70)

16Cr12NiMo 17Cr14NiCuMoNbTi 18Cr9NiCuNbN

AISI 316 Super 304H

+Cr ASME TP304CuNbN

+Ni SUS304J1HTB

(37) (65) (90)

22Cr12Ni 25Cr20Ni 25Cr20NiNbN 22,5Cr18,5NiWCuNbN

AISI 309 AISI 310 HR3C SAVE 25

ASME TP310NbN SUS310J3TB

SUS310J2TB (85)

(53) 20Cr25NiMoNbTi

21Cr32NiTiAl NF709

SUS310J2TB (66)

Alloy 800H

22Cr15NiNbN

TEMPALOY A-3

SUS309J4HTB (89)

High 23Cr43NiWNbTi () represents creep

HR6W strength (MPa)

Cr and Ni (73)

at temperature of 700°C

content 30Cr50NiMoTiZr for 100 000 hours

CR30A

Fig. 6. Development of austenitic steels intended for devices in power engineering [12]

The MARBN steel is a martensitic steel and, sim- 0.015%Ti and 40-170 ppm N; Ce = 0.35, in which,

ilarly to the P92 steel, contains approximately owing to appropriate Ti/N proportions it was

9% chromium. A novelty is the introduction possible to obtain an unexpected effect. Follow-

of strictly controlled boron and nitrogen con- ing the welding of the steel, in the HAZ area of a

tents to its chemical composition in order to joint it was possible to obtain a significantly vis-

significantly improve the creep strength of the ible restriction of the width of a coarse-grained

steel at an operating temperature of 650°C. As zone (CGHAZ – coarse-grained HAZ), which in

opposed to the P92 steel, the MARNB steel does turn enabled an increase in the crack resist-

not contain molybdenum, which is a complete- ance of a welded joint [26]. An example of the

ly new solution in the group of steels having a case under discussion is presented in Figure 7.

non-austenitic structure intend-

ed for use in power engineering.

Traditional

The approximate chemical com- steel with

TiN addition

position of the MARBN steel is pre-

sented in Table 1. Weld CGHAZ: 2,5 mm

Reference publications also

contain information regarding TiN steel with

high nitrogen

the results of the tests of structural content 100 μm

steels modified with nitrogen. An Weld CGHAZ: 0,2 mm

example is an unalloyed steel with Fig. 7. Comparison of microstructure of HAZ in welded joint of traditional

an approximate chemical compo- steel stabilised with titanium and nitrogen addition (top)and steel

sition containing 0.1%C; 1.5%Mn; with high nitrogen content (bottom) [26]

No. 5/2013 BIULETYN INSTYTUTU SPAWALNICTWA 37

Summary 3. Dobrzański J. (2011). Materiałoznawcza in-

Based upon data available in reference pub- terpretacja trwałości stali dla energetyki.

lications it is possible to conclude that the situ- Open Access Library. Scientific Internatio-

ation of structural steels for conventional power nal Journal of the World Academy of Mate-

engineering is stable. The necessity of increas- rials and Manufacturing Engineering, vol. 3.

ing the efficiency of power units, and thus the 4. Blicharski, M. (2013). Zmiany mikrostruktu-

necessity of building high-power boilers of su- ry w połączeniach spawanych różnoimien-

percritical parameters, entails the development nych materiałów stosowanych w energetyce.

of steels operating in creep conditions. At pres- Przegląd Spawalnictwa, (3), pp. 2-13.

ent, an example of the progress in modern ma- 5. Kern, T. U., Weighthardt, K. and Kirchner

terials of this type is the X12CrCoWVNb12-2-2 H. (2004). Material and design solutions for

martensitic steel with the addition of cobalt and advanced steam power plants. Proceedings

tungsten known in Europe as the VM12-SHC of the Fourth International Conference on

steel or the new X13CrMoCoVNbNB9-2-1 steel Advances in Materials Technology for Fos-

designated with an interim symbol of PB2. sil Power Plants. Hilton Head Island, USA.

Among the analysed groups of structural 6. Gierschner, G. (2008). COMTES 700 - on track

materials for conventional power engineering towards the 50plus Power Plant New Build

structures steels having the greatest chances of Europe 2008, Düsseldorf, 4th-5th March.

use in the future are the following: 7. Mohrbach, L. and Stolzenberger, C. (2008). Ul-

a) unalloyed steels having a ferritic-pearlit- tra Super Critical Coal Generation. IERE 2008

ic structure: 13CrMo4-5 (equivalent of the Florida Workshop ”More kWhs… Less Carbon”.

15HM steel) and 10CrMo9-10 (equivalent 8. Chmielniak, T. (2009). Kierunki ewolucji

of the 10H2M steel); głównych maszyn i urządzeń energetycznych

b) alloyed steels having a bainitic struc- dla nowych rozwiązań i koncepcji bloków

ture: 7CrWVMoNb9-6 (T/P23) and energetycznych. in: Hernas, A. eds. 2009.

7CrMoVTiB10-10 (T/P24); Materiały i technologie do budowy kotłów

c) alloyed steels having a martensitic struc- nadkrytycznych i spalarni odpadów. Wy-

ture: X10CrMoVNb9-10 (T/P91), dawnictwo Stowarzyszenia Inżynierów

X10CrWMoVNb9-2 (T/P92), i Techników Przemysłu Hutniczego w Pol-

X12CrCoWVNb12-2-2 (VM12-SHC) and sce, Katowice, pp. 12-26.

12Cr3W3CoVNbTaNdN (SAVE12); 9. Scarlin, B. and Stamatelopoulos, G. N.

d) alloyed steels having an austenitic struc- (2002). New boiler materials for advanced

ture: 18Cr8NiWNbN (Super 304H), steam conditions. Materials for Advanced

X7CrNiNb18-10 (347H) and Power Engineering 2002. Proceedings

25Cr20Ni0.4Nb0.2N (HR3C). of the 7th Liege Conference. European

Commission, University de Liege, vol. 21,

References pp. 1091-1108.

1. Schlachter, W., Gessinger, G. H., Wolk R. 10. Brózda, J. (2006). Stale austenityczne nowej

and McDaniel, J. (1990). Proceedings of the generacji stosowane na urządzenia dla ener-

Conference on High Temperature Materials getyki o parametrach nadkrytycznych i ich

for Power Engineering, Part I, Liege. spawanie. Biuletyn Instytutu Spawalnictwa,

2. Hernas, A. and Dobrzański, J. (2003). Trwa- (5), pp. 40-48.

łość i niszczenie elementów kotłów i turbin 11. Hernas, A. (2000). Żarowytrzymałość sta-

parowych. Wydawnictwo Politechniki Ślą- li i stopów. Wydawnictwo Politechniki Ślą-

skiej, Gliwice. skiej, Gliwice.

38 BIULETYN INSTYTUTU SPAWALNICTWA No. 5/2013

12. Masuyama, F. (2006). Advanced power plant niestopowe i stopowe o określonych włas-

developments and material experiences in nościach w podwyższonych temperaturach.

Japan. Proceedings of the 8th Liege Confer- 21. ASTM A213/A213M-11a Standard Specifi-

ence: Materials for Advanced Power Engi- cation for Seamless Ferritic and Auste-

neering 2006”. Part I, vol. 53, pp. 175-187. nitic Alloy-Steel Boiler, Superheater, and

13. Dobrzański, J. and Pasternak J. (2011). Ocena Heat-Exchanger Tubes.

struktury i własności materiału rodzimego 22. PN-EN 10222-2:2002 Odkuwki stalowe na

i złączy spawanych martenzytycznych stali urządzenia ciśnieniowe. Część 2: Stale ferry-

9-12% Cr na pracujące w warunkach pełza- tyczne i martenzytyczne o określonych wła-

nia elementy krytyczne części ciśnieniowej snościach w podwyższonych temperaturach.

kotłów o nadkrytycznych parametrach pra- 23. Von Heuser, H. and Jochum, C. (2008).

cy. 2nd Welding Conference „Badania oraz Rohrstähle für moderne Hochleistung-

zastosowanie nowych stali żarowytrzyma- skraftwerke. Teil 2: Schweißzusätze und

łych dla energetyki w zakresie temperatu- schweißtechnische Verarbeitung. 3R Inter-

ry pracy 600-650°C”. PowerWelding 2011, national (47), vol. 7, pp. 13-18.

8-9.09.2011, Kroczyce, Ostaniec, pp. 75-91. 24. Viswanathan, R., Purgert, R. and Rao, U.

14. Brózda, J., Zeman, M., Pasternak, J. and Fu- (2005). Materials technology for advanced

dali St. (2009). Żarowytrzymałe stale baini- coal power plants. Proceedings of the 1st In-

tyczne nowej generacji - ich spawalność i ternational Conference: Super-High Strength

własności złączy spawanych. in: Hernas, A. Steels. Rome, Italy.

eds. 2009. Materiały i technologie do budo- 25. Abe, F., Tabuchi, M., Semba, H., Igarashi, M.,

wy kotłów nadkrytycznych i spalarni odpa- Yoshizawa, M., Komai, N. and Fujita, A.

dów. Wydawnictwo Stowarzyszenia Inży- (2007). Feasibility of MARBN Steel for Appli-

nierów i Techników Przemysłu Hutniczego cation to Thick Section Boiler Components

w Polsce, Katowice, pp. 27-46. in USC Power Plant at 650°C. Proceedings

15. Zeman, M. and Brózda, J. (2000). Stale ża- from the 5th International Conference: Ad-

rowytrzymałe nowej generacji stosowane w vances in Materials Technology for Fossil

energetyce światowej. Proceedings of Confe- Power Plants, Marco Island, Florida, Octo-

rence: „Problemy i innowacje w remontach ber 3-5, 2007, pp. 92-106.

energetycznych”, PIRE 2000, 28.11-01.12.2000, 26. Hong Chul, Leong, Younga Ho An, Wung

Szklarska Poręba, pp. 277-284. Yong Choo (2001). Characteristics of HAZ

16. Arndt, J., Haarmann, K., Kottmann, G., microstructure and mechanical properties in

Vaillant, J. C., Bendick, W., Kubla, K., Arb- high nitrogen TiN steel. Proceedings of Fifth

ab, A. and Deshayes, F. (2000). The T23/T24 Workshop on the Ultra-Steel: Ultra-Steel:

Book. Vallourec & Mannesmann Tubes. Future Challenges based on the Atest Re-

17. COST 536 PB2 Steel. Size ODxWT 219,1x31 sults. National Research Institute for Met-

mm. Order No. 1011211-002. Mechanical test als, Tsukuba, Japan, pp. 224-225.

certificate. Tenaris Dalmine, 2010.

18. Richardot, D., Vaillant, J. C., Arbab, A. and

Bendick, W. (2000). The T92/P92 Book. Val-

lourec & Mannesmann Tubes.

19. VdTÜV-Werkstoffblatt. Warmfester Stahl

VM12-SHC. WB 560/2, 03.2009.

20. PN-EN 10028-2:2010 Wyroby płaskie ze sta-

li na urządzenia ciśnieniowe. Część 2: Stale

No. 5/2013 BIULETYN INSTYTUTU SPAWALNICTWA 39

You might also like

- PDF Manual Caterpillar 3306Document3 pagesPDF Manual Caterpillar 3306LuisanaOliveros73% (11)

- Cat 740 BDocument13 pagesCat 740 BTom Souza100% (5)

- 0405 0417 PDFDocument13 pages0405 0417 PDFRadharaman DasNo ratings yet

- Material Aspects of A 700 C Power Plant 4Document7 pagesMaterial Aspects of A 700 C Power Plant 4malsttarNo ratings yet

- File 024476424Document8 pagesFile 024476424mohamedahmedsayed484No ratings yet

- Optimization of Steam Cycles With Respect To Supercritical ParametersDocument7 pagesOptimization of Steam Cycles With Respect To Supercritical ParametersBac Duy NguyenNo ratings yet

- Improving The Energy Efficiency of NPP: S.E. Shcheklein, O.L. Tashlykov, A.M. DubininDocument7 pagesImproving The Energy Efficiency of NPP: S.E. Shcheklein, O.L. Tashlykov, A.M. DubininJorge EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Chap 27 PDFDocument22 pagesChap 27 PDFnelson escuderoNo ratings yet

- Steel Sections in Power Plant ConstructionDocument32 pagesSteel Sections in Power Plant ConstructionFNo ratings yet

- Bhel JournalDocument68 pagesBhel JournalChaitanya Raghav SharmaNo ratings yet

- Boiler Materials For USC Plants IJPGC 2000Document22 pagesBoiler Materials For USC Plants IJPGC 2000pawanumarji1100% (1)

- Experiences in Designing and Operating The Latest 1,050-MW Coal-Fired BoilerDocument5 pagesExperiences in Designing and Operating The Latest 1,050-MW Coal-Fired BoilerswatkoolNo ratings yet

- Future Development of Electric Equipment Manufacturing: High Efficiency, Energy Saving, Environmental ProtectionDocument31 pagesFuture Development of Electric Equipment Manufacturing: High Efficiency, Energy Saving, Environmental ProtectionblazegloryNo ratings yet

- Advancedmaterials PDFDocument13 pagesAdvancedmaterials PDFshaonaaNo ratings yet

- Gas Turbine Blade Failure Scenario Due To Thermal Load 2021 Materials TodayDocument8 pagesGas Turbine Blade Failure Scenario Due To Thermal Load 2021 Materials TodayMusyaffa RaisaNo ratings yet

- Influence of Heat Input and Post-Weld Heat Treatment On Boiler Steel P91 (9Document10 pagesInfluence of Heat Input and Post-Weld Heat Treatment On Boiler Steel P91 (9Hatem RagabNo ratings yet

- Coke Chem 1710004 Lipunov KORDocument7 pagesCoke Chem 1710004 Lipunov KORchemamarNo ratings yet

- Engineering Failure Analysis: M. Santos, M. Guedes, R. Baptista, V. Infante, R.A. CláudioDocument3 pagesEngineering Failure Analysis: M. Santos, M. Guedes, R. Baptista, V. Infante, R.A. CláudioKhaled HamodiNo ratings yet

- Development of 700°C Class Steam Turbine TechnologyDocument6 pagesDevelopment of 700°C Class Steam Turbine TechnologyJuve100% (1)

- Performance Evaluation of Combined Heat and Power PDFDocument9 pagesPerformance Evaluation of Combined Heat and Power PDFAbd Elrahman HamdyNo ratings yet

- Boiler Deporst SetupDocument9 pagesBoiler Deporst SetupbalusmeNo ratings yet

- RITMDocument7 pagesRITMAliNo ratings yet

- Finite Element Analysis of Steam Boiler Used in Power PlantsDocument8 pagesFinite Element Analysis of Steam Boiler Used in Power PlantsArkay KumarNo ratings yet

- USC Steam Turbine TechnologyDocument17 pagesUSC Steam Turbine TechnologyteijarajNo ratings yet

- Advanced Technologies For Blast Furnace Life Extension: Technical ReportDocument10 pagesAdvanced Technologies For Blast Furnace Life Extension: Technical ReportEnMS BF5No ratings yet

- BoilerDocument29 pagesBoilerMadhan RajNo ratings yet

- The Performance of Stirling Engine of The Free Piston Type Enhanced With Sic Ceramics HeaterDocument5 pagesThe Performance of Stirling Engine of The Free Piston Type Enhanced With Sic Ceramics HeaterJorge ArcosNo ratings yet

- Application of Eutectic Composites To Gas Turbine System and Fundamental Fracture Properties Up To 1700°CDocument9 pagesApplication of Eutectic Composites To Gas Turbine System and Fundamental Fracture Properties Up To 1700°CMikecz JuliannaNo ratings yet

- Metals 13 00076Document8 pagesMetals 13 00076GAURI RAJENDRA MAHALLENo ratings yet

- Review Paper On Ultra Supercritical Power Plants Full Length PaperDocument7 pagesReview Paper On Ultra Supercritical Power Plants Full Length PaperAtul NegiNo ratings yet

- Overall Model of The Dynamic Behaviour of The Steel Strip in An Annealing Heating Furnace On A Hot-Dip Galvanizing LineDocument16 pagesOverall Model of The Dynamic Behaviour of The Steel Strip in An Annealing Heating Furnace On A Hot-Dip Galvanizing LineJuan Perez AstillaNo ratings yet

- Research and Development of Heat Resistant Materials For Advanced - 2015 - EnginDocument14 pagesResearch and Development of Heat Resistant Materials For Advanced - 2015 - EnginDicky Pratama PutraNo ratings yet

- Engineering Failure Analysis: M. Santos, M. Guedes, R. Baptista, V. Infante, R.A. CláudioDocument10 pagesEngineering Failure Analysis: M. Santos, M. Guedes, R. Baptista, V. Infante, R.A. CláudioCHONKARN CHIABLAMNo ratings yet

- Modelling of Flexible Boiler Operation in Coal FirDocument8 pagesModelling of Flexible Boiler Operation in Coal FirAl Qohyum FernandoNo ratings yet

- TP ThermalDocument37 pagesTP ThermalgorkembaytenNo ratings yet

- Steam SurbinesDocument12 pagesSteam Surbinesmahmood750No ratings yet

- Combustion Optimisation of Stoker Fired Boiler Plant by Neural NetworksDocument7 pagesCombustion Optimisation of Stoker Fired Boiler Plant by Neural Networksgr8khan12No ratings yet

- Submerged Arc TechnologyDocument11 pagesSubmerged Arc TechnologymerlonicolaNo ratings yet

- Rahmani NTRP 2009Document10 pagesRahmani NTRP 2009Vignesh AlagesanNo ratings yet

- State-Of-The-Art Technologies For The 1,000-Mw 24.5-Mpa/ 600°C/600°C Coal-Fired BoilerDocument4 pagesState-Of-The-Art Technologies For The 1,000-Mw 24.5-Mpa/ 600°C/600°C Coal-Fired BoilerRezwana SarwarNo ratings yet

- Hitachi Boiler PDFDocument5 pagesHitachi Boiler PDFRichard Andrianjaka LuckyNo ratings yet

- Structure and Properties of The Composite Material Based On Heat-Resisting VKNA-4U Alloy With Oxide Stiffening FillersDocument7 pagesStructure and Properties of The Composite Material Based On Heat-Resisting VKNA-4U Alloy With Oxide Stiffening FillersMikecz JuliannaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0360544218323739 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0360544218323739 MainAltaccount KıvançNo ratings yet

- 2development of 900 MW Coal-Fired Generating UnitsDocument8 pages2development of 900 MW Coal-Fired Generating Unitsrajum650100% (1)

- Waste Management: Fabio Dal Magro, Haoxin Xu, Gioacchino Nardin, Alessandro RomagnoliDocument10 pagesWaste Management: Fabio Dal Magro, Haoxin Xu, Gioacchino Nardin, Alessandro RomagnoliKARAN KHANNANo ratings yet

- Residual Life Assessment of 60 MW Steam Turbine RotorDocument11 pagesResidual Life Assessment of 60 MW Steam Turbine RotorGanseh100% (1)

- 700 MW Plant DescripionDocument6 pages700 MW Plant Descripionsathesh100% (1)

- Ijiset V2 I10 37Document12 pagesIjiset V2 I10 37Ram HingeNo ratings yet

- Industrial Materials For The Future: C S M M A S RDocument2 pagesIndustrial Materials For The Future: C S M M A S RSatria PurwantoNo ratings yet

- Boiler Firing Control Design Using Model Predictive TechniquesDocument6 pagesBoiler Firing Control Design Using Model Predictive TechniquesAqmal FANo ratings yet

- Concept of Turbines For Ultrasupercritical, Supercritical, and Subcritical Steam ConditionsDocument7 pagesConcept of Turbines For Ultrasupercritical, Supercritical, and Subcritical Steam ConditionsRAM KrishanNo ratings yet

- FER-56-4-123-2010 Recent Technologies For Steam TurbinesDocument7 pagesFER-56-4-123-2010 Recent Technologies For Steam TurbinesNgoc Thach PhamNo ratings yet

- Effect of Post Welding Heat Treatment On The Mechanical and Microstructural Properties of Extra High Strength Steel Weld Metals For Application OnDocument10 pagesEffect of Post Welding Heat Treatment On The Mechanical and Microstructural Properties of Extra High Strength Steel Weld Metals For Application OnEhsan HaratiNo ratings yet

- Vacuum Furnaces For Metallurgical Processing: October 2020Document8 pagesVacuum Furnaces For Metallurgical Processing: October 2020PHÁT NGUYỄN VĂN HỒNGNo ratings yet

- Commercial Operation of 600 MW UnitDocument5 pagesCommercial Operation of 600 MW Unitwaleed emaraNo ratings yet

- Design Features of Advanced Ultrasupercritical PlantsDocument6 pagesDesign Features of Advanced Ultrasupercritical PlantstuanphamNo ratings yet

- Design PFBRDocument9 pagesDesign PFBRsamit327mNo ratings yet

- Innovation in Electric Arc Furnaces: Scientific Basis for SelectionFrom EverandInnovation in Electric Arc Furnaces: Scientific Basis for SelectionNo ratings yet

- Proceedings of the 2014 Energy Materials Conference: Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, China, November 4 - 6, 2014From EverandProceedings of the 2014 Energy Materials Conference: Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, China, November 4 - 6, 2014No ratings yet

- Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Superalloy 718 and DerivativesFrom EverandProceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Superalloy 718 and DerivativesNo ratings yet

- APM Tools 20130410Document7 pagesAPM Tools 20130410Tibor KeményNo ratings yet

- Titan TTSDocument5 pagesTitan TTSTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- ML003739516Document8 pagesML003739516Tibor KeményNo ratings yet

- p91 OxidDocument11 pagesp91 OxidTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- Heavy Forging USDocument47 pagesHeavy Forging USTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- MARBN SteelDocument16 pagesMARBN SteelTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- Asme Buttering Different Companies-InterpretDocument1 pageAsme Buttering Different Companies-InterpretTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- Beta Titanium Alloys in Aerospace IndustryDocument2 pagesBeta Titanium Alloys in Aerospace IndustryTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- Investigation of The Performance Characteristics of Re-Entry VehiDocument86 pagesInvestigation of The Performance Characteristics of Re-Entry VehiTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- f-8 Weldability Evaluation and Microstructure Analysis of Resistance Spot Welded HighDocument9 pagesf-8 Weldability Evaluation and Microstructure Analysis of Resistance Spot Welded HighTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- Forging Offshore-BrochureDocument5 pagesForging Offshore-BrochureTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- Asme - PWHT of Weld Overlayed Components - Section - 2-InterpretDocument1 pageAsme - PWHT of Weld Overlayed Components - Section - 2-InterpretTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- Asme Head-Forming InterpretDocument1 pageAsme Head-Forming InterpretTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- Standard Specification For Commercial Bronze Strip For Bullet JacketsDocument6 pagesStandard Specification For Commercial Bronze Strip For Bullet JacketsTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- Modern PowerplantsDocument12 pagesModern PowerplantsTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- 02 Weglowski Pfeifer Influence of Cutting Technology On The Quality of Unalloyed Steel SurfaceDocument11 pages02 Weglowski Pfeifer Influence of Cutting Technology On The Quality of Unalloyed Steel SurfaceTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- Competence-N6 Competence Oerlikon5838164642330492430 PDFDocument44 pagesCompetence-N6 Competence Oerlikon5838164642330492430 PDFTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- Freenove - Raspberry Pi Smart Car (3 Wheels)Document106 pagesFreenove - Raspberry Pi Smart Car (3 Wheels)Tibor KeményNo ratings yet

- Seamless Tubes and Pipes For Power Plants OKDocument7 pagesSeamless Tubes and Pipes For Power Plants OKJason BrownNo ratings yet

- Seamless Tubes and Pipes For Power Plants OKDocument7 pagesSeamless Tubes and Pipes For Power Plants OKJason BrownNo ratings yet

- Welding of High Strength Toughened Structural Steel S960QLDocument11 pagesWelding of High Strength Toughened Structural Steel S960QLTibor KeményNo ratings yet

- AboutDocument1 pageAboutMartynov MedinaNo ratings yet

- Meghalaya 04092012Document46 pagesMeghalaya 04092012HIMADRI 3837No ratings yet

- TT Electronics Capacitor Discharge CalculatorDocument7 pagesTT Electronics Capacitor Discharge CalculatorAnonymous ga5pyLmMCWNo ratings yet

- Exp 6Document8 pagesExp 6HR HabibNo ratings yet

- Intro To UV-Vis SpectrosDocument14 pagesIntro To UV-Vis SpectrosKuo SarongNo ratings yet

- FDK - BBCV2.MH13421 - Lithium Batteries - ComponentDocument7 pagesFDK - BBCV2.MH13421 - Lithium Batteries - ComponentMedSparkNo ratings yet

- Liebert Ita Datasheet 5kva To 20kva 2Document4 pagesLiebert Ita Datasheet 5kva To 20kva 2HafidGaneshaSecretrdreamholicNo ratings yet

- The Generation of Electricity by Nuclear Power Plant Is Described in DetailDocument6 pagesThe Generation of Electricity by Nuclear Power Plant Is Described in DetailAlexander NguNo ratings yet

- Electrochemistry Ws 2: II IIDocument23 pagesElectrochemistry Ws 2: II IIBilal Hameed100% (1)

- Biodiesel and Fuel Filter Service Intervals (TSB 07-02)Document2 pagesBiodiesel and Fuel Filter Service Intervals (TSB 07-02)Jorge Cuadros BlasNo ratings yet

- SA12A90 - F10 Data Sheet On-OffDocument1 pageSA12A90 - F10 Data Sheet On-Offanbarasan100% (1)

- Neutrons Are Not Fundamental ParticlesDocument8 pagesNeutrons Are Not Fundamental ParticlesKeith D. FooteNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Si and Ci EngineDocument16 pagesPresentation On Si and Ci EngineAman Jain0% (1)

- Nce Catalos Final Draft PDFDocument45 pagesNce Catalos Final Draft PDFJhonatan Villafuerte HuamancondorNo ratings yet

- 2017 PosterDocument1 page2017 PostertilamisuNo ratings yet

- April 30 2015 Beltane Clearing Dark Female Energies.Document8 pagesApril 30 2015 Beltane Clearing Dark Female Energies.Dustin ThomasNo ratings yet

- Enerjet High Velocity Gas/Oil Combination Burner: Ejc-1 Edition 08-08Document2 pagesEnerjet High Velocity Gas/Oil Combination Burner: Ejc-1 Edition 08-08鄭元豪No ratings yet

- HNX Co Pte LTD Company ProfileDocument17 pagesHNX Co Pte LTD Company ProfileMr. KNo ratings yet

- Hysys FileDocument34 pagesHysys FileSyed Saad ShahNo ratings yet

- BedZED Housing, Sutton, London BILL DUNSTER ARCHITECTS PDFDocument3 pagesBedZED Housing, Sutton, London BILL DUNSTER ARCHITECTS PDFflavius00No ratings yet

- CX75 225SRDocument28 pagesCX75 225SREng Ahmed ABasNo ratings yet

- Guide To The Application of The European STD en 50160 Final Draft 2003Document21 pagesGuide To The Application of The European STD en 50160 Final Draft 2003Gustavo AguayoNo ratings yet

- Urvan Diesel 2.7Document48 pagesUrvan Diesel 2.7Sergio NavaNo ratings yet

- LADWP Power Rate Proposal Cost Reduction ReportDocument143 pagesLADWP Power Rate Proposal Cost Reduction ReportBill RosendahlNo ratings yet

- 08 GRP01 All EnginesDocument24 pages08 GRP01 All Enginescianurel2184No ratings yet

- ATD Module 4Document23 pagesATD Module 4kannanNo ratings yet

- A Numerical Study of Some Aspects of The Spherical Charge Cratering TheoryDocument15 pagesA Numerical Study of Some Aspects of The Spherical Charge Cratering TheoryÁALNo ratings yet