Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Balkan Love-Affair

A Balkan Love-Affair

Uploaded by

Hannah MarshallOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Balkan Love-Affair

A Balkan Love-Affair

Uploaded by

Hannah MarshallCopyright:

Available Formats

First person

A Balkan love-affair

When Hannah Marshall met her Croatian grandma for the first time, she fell in love with her Balkan heritage. It was a love that culminated in a passionate liaison with a small communist-era car 'This car," the policeman said as he paced towards the rear of my Zastava 750, "it's no good. It is, how do you say, dangerous." I was in no position to argue. The exhaust lay crumpled on the motorway verge, and those Italians unfortunate enough to be following my 750 when it started to fall apart had joined me in the layby. "And you take car to London?" he continued. I nodded wearily. "But why?" It was a perfectly reasonable question; in fact I was beginning to ask myself the very same thing. Why was I so compelled to drag this old wreck (with an engine the size of a lawnmower's and a reputation as the worst car ever made) all the way from Ljubljana to London? "Strange holiday, huh?" he concluded, patting the orange roof, turning on his heel and walking away. Even if I had spoken Italian, I don't think he would have understood my dream of a decade; how this little car was an important part of my heritage. The Zastava 750 (or the Yugo) was the car of Tito's Yugoslavia and I had come across it when I was 17 and visiting my relatives in Croatia for the first time. Since that family holiday 10 years ago, an obsession with the Balkan world has gripped me. I've visited the former Yugoslavia eight times and travelled extensively in Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Montenegro and Slovenia. I've learned the language, I've taken an MA in South-East European studies and been seduced by the culture. In the process, I've developed a close relationship with my great-aunts and uncles, and with my cousins once and twice removed. And finally I bought my Yugo. It all began when my dad told my brother and me, aged 12 and 14, that we were going to meet our grandmother. To some degree I understood the implications of this. My dad's relationship with his mother, Milka, was a thorny issue. Milka had walked out on her husband when my dad, Robin, her only child, was three. Having been left for another man, my grandfather cut his wife out of all of his photographs and then he cut her out of his son's life. After an awkward meeting with her in his adolescent years, Dad decided for himself that he had no desire to piece things back together. So for many years, despite living in the UK, Milka remained a distant figure in all our lives, one who sent the odd gift - Yugoslavian dolls, squares of peasant-made muslin cloth, a Cyrillic edition of Pinocchio. Then, in 1994, Milka called to say she had cancer and that she would like to see my father before she died. Suddenly, at 49, my dad had a mum - and I had another grandma. And she was no ordinary grandma but an exotic one who came from somewhere far away. Although I had no understanding of what it meant to be Slav or Croat, or even where Croatia was, at that first meeting it was my expat grandmother's east Europeanness that made the deepest impression on me. I remember, most sharply, the joy of discovering a different world, one that belonged to my grandmother and therefore one I could claim ownership of as well. Her flat, on a leafy suburban street in Acton, west London, was always full of people, cigarette smoke and the smells of cooking. I would gorge on homemade dishes of calamari, gnocchi and ragu, borek and baklava. It seemed to me that each time I visited, all my senses were awakened, and when the time came to leave I was left tantalised and hungry for more. At the heart of this world was the concept of "family". So the fact that my dad had been "kept" from them for so many years, hung over proceedings like a dark cloud. The stories she told us were about how she had suffered, about how cruelly she had been treated by my grandfather, about how being separated from her son was like having her heart ripped out. She had had to choose between the man she loved and her child. In the end, her decision was driven by desperation, trapped as she was in an unhappy marriage and isolated and lonely in a new city where she couldn't speak the language. She had

left believing she would still have access to her child. When it became clear that her status as an adulterous woman, and an immigrant, denied her any influence in divorce proceedings, she retreated to bed for months, broken. There was even a monument to her grief: her second husband had bought her dozens of china robins in memory of her lost son, her Robin. But Robin was listening to a woman who had abandoned him speak negatively of the father who had raised him. He, too, had to come to terms with what he was losing; and what he had already lost. Thus, this reunion with his estranged maternal family was tainted by painful childhood memories and underlying tensions. My dad had rejected this family once before. As a 16-year-old boy, wary of oppressive familial traditions, he made the decision that he didn't want any more relatives in his life. I, however, had never had many relatives and, as a result, when I met my extended family I was more than willing to let them in. Milka's funeral and wake - when they came - proved tumultuous. Fights erupted continually. My parents joked that it was like being in The Godfather but in reality they were struggling with this Balkan obsession with lineage and family loyalty. I, one step removed, was able to enjoy the drama. After the funeral I felt bereft, not only for my grandmother but also my Croatian heritage. I was only just beginning to appreciate it. Fortunately, two years later we went on holiday in Pula to visit relatives and so began my immersion in all things Balkan, which resulted in me digging up my family's past: their role in the anti-fascist resistance during the second world war; how they had lived under Tito's communism; how they felt about the recent conflict and the dissolution of Yugoslavia. It fed my academic progression, towards an MA at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies. My Croatian family suggested that I should forget London and buy an apartment in Pula. By now, my fascination with Balkan history and culture was such that even my younger cousins couldn't fathom it. For them the Yugo was the strangest compulsion of all. Slumped at the table after dinner, my cousin's husband, Marion, jibed: "These cars are like toys, you fix them with your underwear!" No one could understand why I was doing it. But my cousin Ivica had planted the seed years earlier by telling me a 750 would never make it to London. "All right," he relented. "You are very brave. Or crazy. Anyway the Yugo is not such a bad car, the engine is strong. Just be careful. Oh, and make sure that you have brakes - they must work even if nothing else does." A few days later, Ivica's words rang in my ears as my car limped on to a tow truck, exhaustless. And it was only when I saw it on the back of the lorry that it dawned on me how much I loved it and how determined I was to get it home. After five days of twiddling my thumbs in Monfalcone, famous only for shipbuilding, two denim-clad mechanics had me on the road again. Averaging 45mph and stopping in obscure villages every 50km to rest the engine, the Yugo wound its way through the Italian countryside and (very) slowly I was able to join up the dots on my map. It took five days to journey across northern Italy, and it was never boring. Forced to stop in towns far from the tourist trail, the car paved the way for many encounters on my journey. There were plenty of Italian men who appreciated the Yugo as much as I did. "Seicento!", they would scream through my open window. "No," I would shout back, "Z-A-S-T-A-V-A. Yugoslavia." For them, it was beautiful, if only because it reminded them of their own Fiat 600. The glamorous crowd holidaying along the Cte d'Azur were less in awe; I just slowed up their Ferraris on the narrow roads. By the time I arrived in St Raphael I had been travelling non-stop for eight days but I was only half way to London. It was now Friday and I was due back at work on Monday. My last hope was a car train, which would arrive in Calais on Sunday morning, then a ferry to Dover. Next day the white cliffs welcomed me. As I drove through immigration, the family in the car next to mine were taking photographs of me: I was home and so was my Yugo. It now sits outside my front door and creates a curious amount of interest. As the years have gone by I've been to many places more beautiful, but the pull of Pula remains strong. Last summer, I sat on the city's ruined ramparts with my cousin, watching the sunset over the port. She

was consumed with the same angst that I was when I was 16 and we gossiped in the twilight. Some tourists were taking photographs from the ledge in front of us, and it dawned on me that I wasn't one of them. I wasn't on the outside looking in. I was on the inside. I belonged. I didn't need an academic qualification, extensive travels or a special car. I was part of this place and this place was part of me. By Hannah Marshall First published in the Guardian, Saturday 7th July 2008

You might also like

- EYP Teambuilding Guide - FinlandDocument21 pagesEYP Teambuilding Guide - FinlandMircea PetrescuNo ratings yet

- Parle G - Sales and DistributionDocument18 pagesParle G - Sales and DistributionGourab Kundu83% (48)

- In Dreams Begin Responsibilities by Delmore SchwartzDocument7 pagesIn Dreams Begin Responsibilities by Delmore SchwartzRobert Livingstone67% (3)

- OMG 5 English Form 2 - Unit 2Document11 pagesOMG 5 English Form 2 - Unit 2maaran sivamNo ratings yet

- The Good Life: The Autobiography Of Tony BennettFrom EverandThe Good Life: The Autobiography Of Tony BennettRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- Type 1: What Are The Advantages and Disadvantages?: Use This Template To Help Plan Your EssayDocument3 pagesType 1: What Are The Advantages and Disadvantages?: Use This Template To Help Plan Your EssayÂn's Nguyễn100% (1)

- The Long Road Home (UK - UAE)Document3 pagesThe Long Road Home (UK - UAE)William PardoeNo ratings yet

- Lolita - V. Nabokov 2Document2 pagesLolita - V. Nabokov 2Simina EnăchescuNo ratings yet

- Life before Frank: from Cradle to Kibbutz: Frank's Travel Memoirs, #1From EverandLife before Frank: from Cradle to Kibbutz: Frank's Travel Memoirs, #1No ratings yet

- How I Met My Polish HusbandDocument3 pagesHow I Met My Polish Husbandnikki123willett100% (1)

- My First Trip to The Homeland: In Search of Abandoned Treasures Behind the Iron Curtain: Travels with TaniaFrom EverandMy First Trip to The Homeland: In Search of Abandoned Treasures Behind the Iron Curtain: Travels with TaniaNo ratings yet

- A Chip Shop in Poznań: My Unlikely Year in PolandFrom EverandA Chip Shop in Poznań: My Unlikely Year in PolandRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (8)

- Living, Loving, Longing, Lisbon: Living, Loving, Longing, Lisbon, #1From EverandLiving, Loving, Longing, Lisbon: Living, Loving, Longing, Lisbon, #1No ratings yet

- The Cuckoo Season WatsonDocument217 pagesThe Cuckoo Season WatsonEleniNo ratings yet

- Eugene Zarebski – a Story of Escape, Survival and ResilienceFrom EverandEugene Zarebski – a Story of Escape, Survival and ResilienceNo ratings yet

- The Last Lancer: A Story of Loss and Survival in Poland and UkraineFrom EverandThe Last Lancer: A Story of Loss and Survival in Poland and UkraineNo ratings yet

- Love at the End of the World: Stories of War, Romance and RedemptionFrom EverandLove at the End of the World: Stories of War, Romance and RedemptionNo ratings yet

- Reading TextsDocument12 pagesReading TextsMatovilkicaNo ratings yet

- Through the Eyes of Rita: A Story of Extreme Hardship, Resilience, and DeterminationFrom EverandThrough the Eyes of Rita: A Story of Extreme Hardship, Resilience, and DeterminationNo ratings yet

- How to Love an American Man: A True StoryFrom EverandHow to Love an American Man: A True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (45)

- London On My Mind ExcerptDocument19 pagesLondon On My Mind ExcerptI Read YANo ratings yet

- Homecoming: B Ernhard SchlinkDocument11 pagesHomecoming: B Ernhard SchlinkAlper AnılNo ratings yet

- Krzysztof Kieślowski I M So So 1998Document149 pagesKrzysztof Kieślowski I M So So 1998Oolimpijac100% (2)

- #003 Tongue TwistersDocument2 pages#003 Tongue TwistersJuan QuispeNo ratings yet

- Infant and Young Child FeedingDocument19 pagesInfant and Young Child FeedingAnna Cayad-anNo ratings yet

- Betel VineDocument4 pagesBetel VineBinam LibangNo ratings yet

- The Fault in Our StarsDocument38 pagesThe Fault in Our StarsAlexisNo ratings yet

- Corn MealDocument2 pagesCorn MealSantosh YeleNo ratings yet

- DAILY LESSON PLAN IN TLE 6 (Agriculture)Document31 pagesDAILY LESSON PLAN IN TLE 6 (Agriculture)Ghrazy Ganabol Leonardo87% (30)

- Du Gruyere: The Restaurant 7/7 InformationDocument2 pagesDu Gruyere: The Restaurant 7/7 InformationLeo MoltoNo ratings yet

- Diet Plan 14 Day Low Carb Primal KetoDocument131 pagesDiet Plan 14 Day Low Carb Primal KetoAnonymous 5epXbVwzJ98% (42)

- Sabouraud Dextrose BrothDocument2 pagesSabouraud Dextrose Brothrdn2111No ratings yet

- Alcohol Chemistry: Alcoholic Drinks (Ethanol) Solvents FuelsDocument17 pagesAlcohol Chemistry: Alcoholic Drinks (Ethanol) Solvents FuelsSubhash DhungelNo ratings yet

- Adrenal FatigueDocument6 pagesAdrenal Fatigueray0% (1)

- Future Simple - 1Document3 pagesFuture Simple - 1Александра ЖиряковаNo ratings yet

- Question PaperDocument5 pagesQuestion Papersanjay_rapidNo ratings yet

- @InglizEnglish-4000 Essential English Words 6 UzbDocument193 pages@InglizEnglish-4000 Essential English Words 6 UzbMaster SmartNo ratings yet

- Shyamas Womens Hoste: Annapurnam Womens Paying GuestDocument6 pagesShyamas Womens Hoste: Annapurnam Womens Paying GuestSathish KumarNo ratings yet

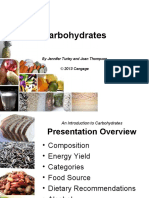

- Module 1-2 CarbohydratesDocument19 pagesModule 1-2 CarbohydratesMaski03No ratings yet

- QuizDocument5 pagesQuizBiondi Andorio HosogawaNo ratings yet

- VitaminB12 Consumer PDFDocument3 pagesVitaminB12 Consumer PDFKingNo ratings yet

- Johor Upsr 2016 English ModuleDocument141 pagesJohor Upsr 2016 English ModuleMun'xJarvisNo ratings yet

- 011 BEO Wedding Wedding Ima & Agam 07 January 2022 (Gino Feruci Kebonjati)Document1 page011 BEO Wedding Wedding Ima & Agam 07 January 2022 (Gino Feruci Kebonjati)Nabila Lathifah KhairunnisaNo ratings yet

- Pectobacterium Carotovorum Ssp. CarotovorumDocument7 pagesPectobacterium Carotovorum Ssp. CarotovorumTanah EkologisNo ratings yet

- Web DesignDocument492 pagesWeb DesignNagaraja SNo ratings yet

- Infant FormulaDocument2 pagesInfant Formulajihan azzubaidiNo ratings yet

- New WordsDocument13 pagesNew Wordstimurbek.eduNo ratings yet

- Ice Cream Parlour FeasibilityDocument23 pagesIce Cream Parlour FeasibilityWeena Yancey M Momin50% (2)

- The Ayurvedic Way Bringing Balance To Your LifeDocument30 pagesThe Ayurvedic Way Bringing Balance To Your Lifemiddela6503100% (1)