Professional Documents

Culture Documents

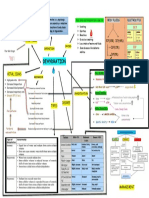

Pterygium and Conjunctival Degenerations

Pterygium and Conjunctival Degenerations

Uploaded by

Juan David VargasOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pterygium and Conjunctival Degenerations

Pterygium and Conjunctival Degenerations

Uploaded by

Juan David VargasCopyright:

Available Formats

PART 4 CORNEA AND OCULAR SURFACE DISEASES

SECTION 4 Conjunctival Diseases

Pterygium and Conjunctival

Degenerations

4.9

Roni M. Shtein, Alan Sugar

Definition:Secondary deterioration or deposition in the conjunctiva,

distinct from the dystrophies.

Key features

■ Common

■ Bilateral usually

■ Typically does not affect vision

Associated features

■ Increased prevalence with age

■ Often associated with chronic light exposure

■ May follow past inflammation

■ Not inherited Fig. 4-9-1 Nasal pinguecula. Elevated conjunctival lesion encroaches on nasal

limbus.

Pingueculae are rarely associated with symptoms other than a mini-

mal cosmetic defect. They may become red with surface keratinization.

INTRODUCTION When inflamed, the diagnosis of pingueculitis may be given.

Distinguishing pingueculae from other lesions is usually not a prob-

Degenerations of the conjunctiva are common conditions that, in most lem because of the typical appearance. Conjunctival intraepithelial

cases, have relatively little effect on ocular function and vision. They neoplasia may be difficult to differentiate from keratinized pinguecula.

increase in prevalence with age as a result of past inflammation, long- Gaucher’s disease type I is said to be associated with tan pingueculae,

term toxic effects of environmental exposure, or aging itself. Conjunc- but this is not a specific finding.5

tival degenerations may be associated with chronic irritation, dryness, Histopathologically, pingueculae are characterized by elastotic

or previous history of trauma. Progression to involve the cornea may degeneration of the collagen with hyalinization of the conjunctival

occur, as in pterygium. stroma, collection of basophilic elastotic fibers, and granular deposits,

and noninvolvement of the cornea.6

PINGUECULA Pingueculitis responds to a brief course of topical corticosteroids or

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents.7 Chronically inflamed or cos-

Pingueculae are elevated, white to yellow in color, horizontally oriented metically unsatisfactory pingueculae rarely warrant simple excision.

areas of bulbar conjunctival thickening that adjoin the limbus in the

palpebral fissure area (Fig. 4-9-1). They are less transparent than nor-

mal conjunctiva, often have a fatty appearance, are usually bilateral, PTERYGIUM

and are located nasally much more often than temporally. When a

pinguecula crosses the limbus onto the cornea, it is called a pterygium. Pterygium is a growth of fibrovascular tissue on the cornea and con-

Current information, however, suggests that pinguecula do not progress junctiva. It occurs in the palpebral fissure, much more often nasally

to pterygium and that the two are distinct disorders. Pingueculae are than temporally, although either or both (“double” pterygium) occur

associated with a 2- to 3-fold increased incidence of age-related macular (Fig. 4-9-2). Elevated whitish opacities (“islets of Vogt”) and an iron

degeneration, possibly through a common light exposure effect.1 deposition line (“Stocker”) may delineate the head of the pterygium on

The causes of pingueculae are not known with certainty. Good evi- the cornea. Like pinguecula, it is a degenerative lesion, although it may

dence exists, however, of an association with increasing age and ultra- appear similar to pseudopterygium, which is a conjunctival adhesion to

violet light exposure. Pingueculae are seen in most eyes by 70 years of the cornea secondary to previous trauma or inflammation, such as

age and in almost all by 80 years of age.2 Chronic sunlight exposure has peripheral corneal ulceration. A pseudopterygium often has an atypical

been found to be a factor by association with outdoor work and equato- position and is not adherent at all points, so a probe can be passed

rial residence. In some studies, the strength of this association is less beneath it peripherally.

than that for pterygium.3, It is thought that the predominantly nasal Like pinguecula, pterygium is associated with ultraviolet light expo-

location is related to reflection of light from the nose onto the nasal sure.3 It occurs at highest prevalence and most severely in tropical areas

conjunctiva. The effect of ultraviolet light may be mediated by muta- near the equator and to a lesser and milder degree in cooler climates.8,9 203

tions in the p53 gene.4 Outdoor work and both blue and ultraviolet light have been implicated

4

CORNEA AND OCULAR SURFACE DISEASES

Fig. 4-9-3 Senile scleral plaque. Calcium deposition appears as a gray scleral plaque

A under the medial rectus muscle insertion.

Fig. 4-9-2 Double pterygium. (A) Note both nasal and temporal pterygia in a

57-year-old farmer. (B) It is the invasion of the cornea that distinguishes a pterygium

from a pinguecula.

in its causation. The use of hats and sunglasses is protective.8,9 In the

past, the pathogenesis of pterygium was thought to be related to distur- Fig. 4-9-4 Primary localized conjunctival amyloid. There is irregularity of the

conjunctiva superonasally with fixed folds. Resolving subconjunctival hemorrhages

bance of the tear film spread central to a pinguecula. More recent theo-

noted superiorly are associated with amyloid deposition in blood vessel walls.

ries include the possibility of damage to limbal stem cells by ultraviolet

light and by activation of matrix metalloproteinases.10,11 The histopa-

thology of pterygium is similar to that of pinguecula except that Bow- yellow, gray, or black vertical bands just anterior to the insertion of the

man’s membrane is destroyed within the corneal component and medial and lateral rectus muscles (Fig. 4-9-3). They become more com-

vascularization is seen.12 Recent evaluation using spectral domain opti- mon after the age of 60 years and, like pinguecula and pterygium, may

cal coherence tomography revealed pterygium as an elevated, wedge- be related to ultraviolet light exposure.18 Histologically, calcium depos-

shaped mass of tissue separating the corneal epithelium from Bowman’s its along with decreased cellularity and hyalinization are seen. These

membrane, which appears abnormally wavy and interrupted and often lesions do not need therapy.

destroyed, with satellite masses of subepithelial pterygium tissue

beyond the clinically seen margins.13 CONJUNCTIVAL AMYLOID

Pterygia warrant treatment when they cause discomfort (not respon-

sive to conservative therapy), encroach upon the visual axis, induce Deposition of amyloid in the conjunctiva has been reported in both

significant astigmatism, or become cosmetically bothersome. Aggres- primary and secondary localized forms (Fig. 4-9-4) and secondary to

sive or recurrent pterygia may cause restrictive strabismus and distor- systemic processes.19 Chronic conjunctival inflammation may cause

tion of the eyelids. A variety of surgical techniques have been developed. secondary localized amyloidosis, a true degenerative change. In the

The goal of treatment is prevention of recurrence. The recurrence rates primary localized forms, light-chain immunoglobulins deposited by

after simple excision are very high: of recurrences, 50% reoccur within monoclonal B cells and plasma cells have been demonstrated by

4 months of excision and nearly all within 1 year.14 Beta-radiation immunohistochemistry.

applied postoperatively to the pterygium base was popular for many In lesions secondary to systemic disease, other forms of amyloid

years, but is associated with late scleral necrosis.15 Currently, the most protein may be seen.20 All patients should be evaluated for lymphopro-

widely used techniques are conjunctival autografting, amniotic mem- liferative and systemic diseases. Amyloid involving the skin of the

brane transplantation, and mitomycin-C application – either pre-, eyelids has been suggested to be a sign of systemic involvement.21

intra-, or postoperatively.15,16 Fibrin-based glues have been used to Conjunctival amyloid may appear as a yellowish, well-demarcated,

minimize operating time and discomfort associated with sutures, and irregularly elevated mass. It generally involves the fornices, with the

to reduce the amount of suturing required.17 superior fornix and tarsal conjunctiva most commonly affected. In vivo

confocal microscopy of conjunctival amyloid shows hyporeflective

SENILE SCLERAL PLAQUES material in a lobular pattern in the substantia propria and around the

blood vessels in the conjunctiva without associated inflammation.22

Senile scleral plaques occur in the sclera of elderly patients and are Recurrent subconjunctival hemorrhages may be associated with amy-

204 frequently misinterpreted as a melting process similar to that of corneal loid deposition in blood vessel walls. Biopsy is required for definitive

degenerations or as conjunctival depositions. These lesions appear as diagnosis.20

Lesions are generally treated symptomatically, though debulking Bozkurt B, Kiratli H, Soylemezoglu F, et al. In vivo confocal microscopy in a patient with

conjunctival amyloidosis. Clin Exper Ophthalmol 2008;36:173–5.

excision can be performed for chronic irritation. Although it may not

Chen PP, Ariyasu RG, Kaza V, et al. A randomized trial comparing mitomycin C and

4.9

cause full regression of deposited amyloid, radiotherapy may be used to

conjunctival autograft after excision of primary pterygium. Am J Ophthalmol 1995;120:

prevent progression.23 151–60.

Pterygium and Conjunctival Degenerations

Folberg R, Jakobiec FA, Bernardino VB, et al. Benign conjunctival melanocytic lesions.

CONJUNCTIVAL MELANOSIS Clinicopathologic features. Ophthalmology 1989;96:436–61.

Leibovitch I, Selva D, Goldberg RA, et al. Periocular and orbital amyloidosis: clinical characteristics,

Conjunctival melanosis is a common finding with advancing age. The management, and outcome. Ophthalmology 2006;113:1657–64.

appearance is that of a flat, pigmented area on the conjunctiva. Primary Lucas RM. An epidemiological perspective of ultraviolet exposure – public health concerns.

acquired melanosis is a risk factor for development of conjunctival Eye Contact Lens 2011;37:168–75.

melanoma and is discussed in detail in Chapter 4-8. Ma DH, See LC, Liau SB, et al. Amniotic membrane graft for primary pterygium: comparison

Secondary melanosis of the conjunctiva is generally benign and with conjunctival autograft and topical mitomycin C treatment. Br J Ophthalmol

2000;84:973–8.

tends to be more frequently bilateral. Secondary melanosis occurs fol-

Mackenzie FB, Hirst LW, Battistutta D, et al. Risk analysis in the development of pterygia.

lowing trauma, chronic inflammation of the conjunctiva, and in indi-

Ophthalmology 1992;99:1056–61.

viduals with darker skin pigmentation.24 Secondary melanosis is

Scroggs MW, Klintworth GK. Senile scleral plaques: a histopathologic study using

generally not associated with atypia and can be observed. If the lesions energy-dispersive X-ray microanalysis. Hum Pathol 1991;22:557–62.

are noted to be elevated or where uncertainty exists, biopsies should be Soliman W, Mohamed TA. Spectral domain anterior segment optical coherence tomography

performed. assessment of pterygium and pinguecula. Acta Ophthalmol 2012;90:461–5.

Taylor HR, West S, Munoz B, et al. The long-term effects of visible light on the eye.

KEY REFERENCES Arch Ophthalmol 1992;110:99–104.

Uy HS, Reyes JMG, Flores JDG, et al. Comparison of fibrin glue and sutures for

Austin P, Jakobiec FA, Iwamoto T. Elastodysplasia and elastodystrophy as pathologic bases of attaching conjunctival autografts after pterygium excision. Ophthalmology 2005;112:

ocular pterygium and pinguecula. Ophthalmology 1983;90:96–109. 667–71.

Access the complete reference list online at

205

You might also like

- Introduction To Agada Tantra, Visha & It's Classification, Properties & Action of Visha, Diagnosis of Poisoning, Treatment of PoisoningDocument123 pagesIntroduction To Agada Tantra, Visha & It's Classification, Properties & Action of Visha, Diagnosis of Poisoning, Treatment of PoisoningAbiskar Adhikari100% (14)

- Concept MapDocument1 pageConcept Mapadriana100% (1)

- Yanoff DukerDocument8 pagesYanoff DukerFerdinando BaehaNo ratings yet

- Miopi X Katarak 4Document5 pagesMiopi X Katarak 4Melati Nurul UtamiNo ratings yet

- Md2024 Corneal DiseaseDocument3 pagesMd2024 Corneal DiseaseRohanNo ratings yet

- Articulo 2Document7 pagesArticulo 2Rocío SánchezNo ratings yet

- Common Conjunctival LesionsDocument4 pagesCommon Conjunctival LesionsSri AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Robbins Ch. 29 The Eye Review QuestionsDocument3 pagesRobbins Ch. 29 The Eye Review QuestionsPA2014No ratings yet

- Pearls Nov Dec 2010Document3 pagesPearls Nov Dec 2010Nhật LongNo ratings yet

- December 2017 Ophthalmic PearlsDocument2 pagesDecember 2017 Ophthalmic PearlsMEDIWAY CLINICNo ratings yet

- Cornea and ScleraDocument144 pagesCornea and SclerakhabibtopgNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmology - Diseases of ConjunctivaDocument11 pagesOphthalmology - Diseases of ConjunctivajbtcmdtjjvNo ratings yet

- Pinguecula - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument6 pagesPinguecula - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfWa Ode Meutya ZawawiNo ratings yet

- Interstitial Keratitis PDFDocument22 pagesInterstitial Keratitis PDFwilliam sitnerNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Inflammatory Corneal Disease (Non-Infectious Keratitis) By:Mohammed SDocument66 pagesPeripheral Inflammatory Corneal Disease (Non-Infectious Keratitis) By:Mohammed SGetenet shumetNo ratings yet

- Mcculley 2012Document11 pagesMcculley 2012Luisa Mayta PitmanNo ratings yet

- 7,8 CorneaDocument20 pages7,8 Corneadykesu1806No ratings yet

- Graves 508Document6 pagesGraves 508VellaNo ratings yet

- T1505C13Document9 pagesT1505C13Gheorgian HageNo ratings yet

- Ocular Findings in SLEDocument5 pagesOcular Findings in SLEyaneemayNo ratings yet

- Sympathetic Uveitis/ Ophthalmia: PG CornerDocument4 pagesSympathetic Uveitis/ Ophthalmia: PG CornerVincent LivandyNo ratings yet

- 2000 Ocular PathDocument26 pages2000 Ocular Pathdeta hamidaNo ratings yet

- CORNEA 5th Ed-804-821Document18 pagesCORNEA 5th Ed-804-821fn_millardNo ratings yet

- Racgp Floaters and Flashes OpthalmologyDocument3 pagesRacgp Floaters and Flashes OpthalmologyBeaulah HunidzariraNo ratings yet

- Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis: An Update: Stefan de Smedt, Gerhild Wildner, Philippe KestelynDocument7 pagesVernal Keratoconjunctivitis: An Update: Stefan de Smedt, Gerhild Wildner, Philippe KestelynSeroja HarsaNo ratings yet

- AAO Reading NNU - Ocular SyphilisDocument31 pagesAAO Reading NNU - Ocular Syphilissigitdwipramono09No ratings yet

- DR Vishali's PaperDocument9 pagesDR Vishali's PaperpoojasharmachdNo ratings yet

- Management of Corneal Abrasions: STEPHEN A. WILSON, M.D., and ALLEN LAST, M.D., University of Pittsburgh Medical CenterDocument6 pagesManagement of Corneal Abrasions: STEPHEN A. WILSON, M.D., and ALLEN LAST, M.D., University of Pittsburgh Medical CenterGokull ShautriNo ratings yet

- PUK Vs Mooren Ulcer Presentasi FinalDocument35 pagesPUK Vs Mooren Ulcer Presentasi FinalRaissaNo ratings yet

- Costagliola Et Al-2013-Clinical and Experimental OptometryDocument7 pagesCostagliola Et Al-2013-Clinical and Experimental OptometrysarassashaNo ratings yet

- Ocular Surgeries, Especially in Patients On AnticoagulationDocument6 pagesOcular Surgeries, Especially in Patients On AnticoagulationaryaNo ratings yet

- Retinal DetachmentDocument9 pagesRetinal DetachmentAnita Amanda PrayogiNo ratings yet

- Ceh 12 30 019 PDFDocument2 pagesCeh 12 30 019 PDFHerwandiNo ratings yet

- Opthalmology LMRDocument16 pagesOpthalmology LMRAqsa MemonNo ratings yet

- SEMINAR On Eyelid Echi 3rd YearDocument93 pagesSEMINAR On Eyelid Echi 3rd Yearsushmitabiswas052No ratings yet

- Ocular Manifestations of Systemic Disease in Cats: Noelle C. La Croix, DVM, Diplomate ACVODocument8 pagesOcular Manifestations of Systemic Disease in Cats: Noelle C. La Croix, DVM, Diplomate ACVOpramiswariNo ratings yet

- Itchy Eyes Case Study: Eye Series - 17Document2 pagesItchy Eyes Case Study: Eye Series - 17nicoNo ratings yet

- TerriensDocument8 pagesTerrienskemai akiateNo ratings yet

- Demystifying Viral Anterior Uveitis: A Review: Nicole Shu-Wen Chan Mbbs - Soon-Phaik Chee Frcophth Mmed (S'Pore)Document14 pagesDemystifying Viral Anterior Uveitis: A Review: Nicole Shu-Wen Chan Mbbs - Soon-Phaik Chee Frcophth Mmed (S'Pore)Dr Pranesh BalasubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Cet 5Document4 pagesCet 5jumi26No ratings yet

- Definitions Opthalmology MedadDocument10 pagesDefinitions Opthalmology MedadAhmed MansourNo ratings yet

- Jurnal KeratitisDocument2 pagesJurnal Keratitisanggun pratissaNo ratings yet

- Ocular ToxocariasisDocument2 pagesOcular ToxocariasisEnderson UsecheNo ratings yet

- ENDOFTALMITISDocument19 pagesENDOFTALMITISAndrea ArmeriaNo ratings yet

- Pan Uveitis (Causes and MGT of Sympathetic Ophthalmitis)Document21 pagesPan Uveitis (Causes and MGT of Sympathetic Ophthalmitis)Edoga Chima EmmanuelNo ratings yet

- Other Anterior Segment Complications Part 2. AyuDocument21 pagesOther Anterior Segment Complications Part 2. AyuAndi Ayu LestariNo ratings yet

- Gupta 2021Document22 pagesGupta 2021stroma januariNo ratings yet

- The Relationship of Opthalmology To Diseases of The Nose and Its Accessory Sinuses 1918Document8 pagesThe Relationship of Opthalmology To Diseases of The Nose and Its Accessory Sinuses 1918Denise MathreNo ratings yet

- Corneal EdemaDocument9 pagesCorneal Edemazeeshan aliNo ratings yet

- Mac HoleDocument21 pagesMac HoleSwati RamtekeNo ratings yet

- Epithelial DowngrowthDocument5 pagesEpithelial Downgrowthaghnia jolandaNo ratings yet

- In Neonates, A Transient 6th Nerve Paresis Can Occur It Usually ClearsDocument22 pagesIn Neonates, A Transient 6th Nerve Paresis Can Occur It Usually ClearsFull MarksNo ratings yet

- Sympathetic OphthalmiaDocument27 pagesSympathetic OphthalmiaAnish KumarNo ratings yet

- Prevention of Blindness in Leprosy: An Overview of The Relevant Clinical and Programme-Planning IssuesDocument9 pagesPrevention of Blindness in Leprosy: An Overview of The Relevant Clinical and Programme-Planning IssuesBudi KhangNo ratings yet

- JR - Glaucoma Sudut Tertutup AkutDocument12 pagesJR - Glaucoma Sudut Tertutup AkutverraNo ratings yet

- Vascularized Limbal Keratitis: Part V LimbusDocument6 pagesVascularized Limbal Keratitis: Part V LimbusVincent NgNo ratings yet

- Bleph PDFDocument13 pagesBleph PDFGusti Zidni FahmiNo ratings yet

- February 2016 Ophthalmic Pearls PDFDocument3 pagesFebruary 2016 Ophthalmic Pearls PDFIndah IndrianiNo ratings yet

- Eye LMRP 2019Document27 pagesEye LMRP 2019skNo ratings yet

- Phacoanaphylactic Endophthalmitis: A Clinicopathologic ReviewDocument9 pagesPhacoanaphylactic Endophthalmitis: A Clinicopathologic ReviewLuci PonceNo ratings yet

- Journal Article 17 276Document3 pagesJournal Article 17 276Lia BirinkNo ratings yet

- Complications in UveitisFrom EverandComplications in UveitisFrancesco PichiNo ratings yet

- Assay of Acetylcholinesterase Activity in The BrainDocument3 pagesAssay of Acetylcholinesterase Activity in The Brainapi-384625590% (10)

- Preparedness For A High-Impact Respiratory Pathogen Pandemic PDFDocument84 pagesPreparedness For A High-Impact Respiratory Pathogen Pandemic PDFchinzsteelNo ratings yet

- Feline Acute Kidney Injury. 2. Approach To Diagnosis, Treatment and PrognosisDocument9 pagesFeline Acute Kidney Injury. 2. Approach To Diagnosis, Treatment and PrognosisMartín QuirogaNo ratings yet

- Test 17 in 2017 With Answer KeyDocument4 pagesTest 17 in 2017 With Answer KeyMeecaiNo ratings yet

- Shoulder Roll PDFDocument2 pagesShoulder Roll PDFMichele GranadaNo ratings yet

- Endoscopy, Barium MealDocument22 pagesEndoscopy, Barium Mealyudhisthir panthiNo ratings yet

- Ceii205 PhysiotherapyDocument49 pagesCeii205 PhysiotherapyWaltas KariukiNo ratings yet

- Admin, JPHV VESTIBULAR NEURONITIS 3Document5 pagesAdmin, JPHV VESTIBULAR NEURONITIS 3williams papilayaNo ratings yet

- Snake Bite ManagementDocument92 pagesSnake Bite ManagementManoharNo ratings yet

- Health ProblemDocument2 pagesHealth ProblemDilausan B MolukNo ratings yet

- HTTPSWWW - Vims.ac - Ineducationpdfgrowth Assessment and Disorders of Growth PDFDocument43 pagesHTTPSWWW - Vims.ac - Ineducationpdfgrowth Assessment and Disorders of Growth PDFSrikar Chowdary BurugupalliNo ratings yet

- Pituitary Agents PharmaDocument42 pagesPituitary Agents PharmaJayson Tom Briva CapazNo ratings yet

- Peter Holmes - Jade Remedies - A Chinese Herbal Reference For West Life Vol 2Document504 pagesPeter Holmes - Jade Remedies - A Chinese Herbal Reference For West Life Vol 2jeanroNo ratings yet

- Living With Diabetes As A Transformational Experience: Barbara Paterson Sally Thorne John Crawford Michel TarkoDocument17 pagesLiving With Diabetes As A Transformational Experience: Barbara Paterson Sally Thorne John Crawford Michel TarkoMohamed MassoudiNo ratings yet

- IDSA Uncomplicated Cystitis and Pyelonephritis GuidelinesDocument18 pagesIDSA Uncomplicated Cystitis and Pyelonephritis GuidelinesDinoop Korol PonnambathNo ratings yet

- 8.8 What Is Gene TherapyDocument2 pages8.8 What Is Gene TherapyNarasimha MurthyNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument5 pagesDrug StudyinjilbalazoNo ratings yet

- Topic 2. Pharmacology For Pain and Inflammation RDocument52 pagesTopic 2. Pharmacology For Pain and Inflammation RKendrick GalosoNo ratings yet

- Disease and Immunity Paper 2 QuestionsDocument38 pagesDisease and Immunity Paper 2 QuestionsBalachandran PalaniandyNo ratings yet

- Anna Garcia Death Timeline 1Document19 pagesAnna Garcia Death Timeline 1api-245176779No ratings yet

- 10th Biology Solved MCQS (Bismillah) EditDocument19 pages10th Biology Solved MCQS (Bismillah) EditSohail Afzal100% (1)

- .TAH A Bionic Heart - IJESCDocument4 pages.TAH A Bionic Heart - IJESCAbhishek SharmaNo ratings yet

- Vaccines Wavre 2019 Ir Event Slides 26 Sep 2019 Final 3Document45 pagesVaccines Wavre 2019 Ir Event Slides 26 Sep 2019 Final 3hau vuvanNo ratings yet

- Assessment of OsteoporosisDocument339 pagesAssessment of OsteoporosisKhủngLongSiêuNguyHiểmNo ratings yet

- Nutri TriviaDocument18 pagesNutri TriviaShiela Mae Mirasol Abay-abayNo ratings yet

- CNS M1 Lecture Slides Compiled, DR OsaiDocument185 pagesCNS M1 Lecture Slides Compiled, DR OsaiMusaNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular System-GlosaryDocument3 pagesCardiovascular System-GlosaryJennevi BrunoNo ratings yet

- CGH PPT - CCCDocument45 pagesCGH PPT - CCCIan GreyNo ratings yet