Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lubaton vs. Lazaro

Lubaton vs. Lazaro

Uploaded by

Paolo Antonio Macalino0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views11 pagesThis document summarizes a resolution regarding a motion for reconsideration filed by Judge Mary Josephine P. Lazaro. Previously, Judge Lazaro was fined ₱5,000 for undue delay in resolving a motion to dismiss in a civil case. In her motion for reconsideration, Judge Lazaro argued that she was denied due process by not being furnished with supplemental complaints, and that her delay was necessary given the heavy docket of her court. The court found Judge Lazaro's arguments meritorious, noting she was not informed of the full charges against her and that the circumstances of her overloaded docket provide context for her delay. The court determined Judge Lazaro's delay was not undue.

Original Description:

Original Title

Lubaton Vs. Lazaro

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document summarizes a resolution regarding a motion for reconsideration filed by Judge Mary Josephine P. Lazaro. Previously, Judge Lazaro was fined ₱5,000 for undue delay in resolving a motion to dismiss in a civil case. In her motion for reconsideration, Judge Lazaro argued that she was denied due process by not being furnished with supplemental complaints, and that her delay was necessary given the heavy docket of her court. The court found Judge Lazaro's arguments meritorious, noting she was not informed of the full charges against her and that the circumstances of her overloaded docket provide context for her delay. The court determined Judge Lazaro's delay was not undue.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views11 pagesLubaton vs. Lazaro

Lubaton vs. Lazaro

Uploaded by

Paolo Antonio MacalinoThis document summarizes a resolution regarding a motion for reconsideration filed by Judge Mary Josephine P. Lazaro. Previously, Judge Lazaro was fined ₱5,000 for undue delay in resolving a motion to dismiss in a civil case. In her motion for reconsideration, Judge Lazaro argued that she was denied due process by not being furnished with supplemental complaints, and that her delay was necessary given the heavy docket of her court. The court found Judge Lazaro's arguments meritorious, noting she was not informed of the full charges against her and that the circumstances of her overloaded docket provide context for her delay. The court determined Judge Lazaro's delay was not undue.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 11

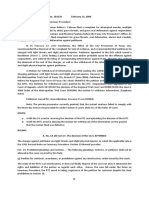

A.M. No.

RTJ-12-2320 September 2, 2013

COL. DANILO E. LUBATON (RETIRED,

PNP), COMPLAINANT,

vs.

JUDGE MARY JOSEPHINE P. LAZARO, REGIONAL

TRIAL COURT, BRANCH 74, ANTIPOLO

CITY, RESPONDENT.

RESOLUTION

BERSAMIN, J.:

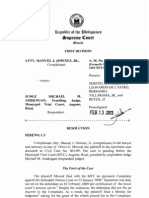

For consideration and resolution is the Motion for

Reconsideration dated June 25, 2012 filed by respondent

Hon. Judge Mary Josephine P. Lazaro, Presiding Judge of

Branch 74 of the Regional Trial Court in Antipolo City,

whereby she seeks to undo the resolution promulgated on

April 16, 2012 fining her in the amount of ₱5,000.00 for

her undue delay in resolving a Motion to Dismiss in a

pending civil case.

Antecedents

Through the aforecited resolution, the Court adopted and

approved the following recommendations contained in the

Report dated February 6, 2012 of the Office of the Court

Administrator (OCA), to wit:

(1)

[T]he instant administrative complaint against Judge Mary

Josephine P. Lazaro, Regional Trial Court, Branch 74,

Antipolo City, Rizal, is REDOCKETED as a regular

administrative case; and

(2)

Judge Lazaro is FINED in the amount of Five Thousand

Pesos (₱5,000.00) and is REMINDED to be more

circumspect in the performance of her duties particularly in

the prompt disposition of cases pending and/or submitted

for decision before her court.1

Thereby, the Court declared respondent Judge

administratively liable for undue delay in the resolution of

the Motion to Dismiss of the defendants in Civil Case No.

10-9049 entitled Heirs of Lorenzo Gregorio y De Guzman,

et al. v. SM Development Corporation, et al.,2 considering

that she had resolved the Motion to Dismiss beyond the

90-day period prescribed for the purpose without filing any

request for the extension of the period.

In her Motion for Reconsideration, respondent Judge

alleges that:

She had not been furnished copies of the supplemental

complaints dated June 13, 2011, June 17, 2011 and July

5, 2011 (with enclosures) mentioned in item no. 2 of the

resolution of April 16, 2012, thereby denying her right to

due process; and

The delay had been only of a few days beyond the period

for resolving the Motion to Dismiss in Civil Case No. 10-

9049, but such delay was necessary and not undue, and

did not constitute gross inefficiency on her part in the

manner that the New Code of Judicial Conduct for the

Philippine Judiciary would consider to be the subject of a

sanction.

On July 16, 2012, the Court directed Lubaton to comment

on respondent Judge's Motion for Reconsideration within

10 days from notice, but he did not comment despite

receiving the notice on September 17, 2012.

Ruling

The Motion for Reconsideration is meritorious.

1.

Respondent Judge's right to due process should be

respected

It appears that Lubaton actually filed five complaints, four

of them being the letters-complaint he had addressed to

Chief Justice Corona (specifically: (1) that dated May 18,

2011;3 (2) that dated June 13, 2011;4 (3) that dated June

17, 2011;5 and (4) that dated July 5, 20116), and the fifth

being the verified complaint he had filed in the OCA.7 All

the five complaints prayed that respondent Judge be held

administratively liable: (a) for gross ignorance of the law

for ruling that her court did not have jurisdiction over Civil

Case No. 10-9049 because of the failure of the plaintiffs to

aver in their complaint the assessed value of the

37,098.34 square meter parcel of land involved the action;

and (b) for undue delay in resolving the Motion to Dismiss

of the defendants.

In its directive issued on July 27, 2011, however, the OCA

required respondent Judge to comment only on the

verified complaint dated July 20, 2011.8 Thus, she was not

notified about the four letters-complaint, nor furnished

copies of them. Despite the lack of notice to her, the OCA

considered the four letters-complaint as "supplemental

complaints" in its Report dated February 6, 2012,9 a sure

indication that the four letters-complaint were taken into

serious consideration in arriving at the adverse

recommendation against her.

Respondent Judge now complains about being deprived

of her right to due process of law for not being furnished

the four letters-complaint before the OCA completed its

administrative investigation.

Respondent Judge's complaint is justified.

It cannot be denied that the statements contained in the

four letters-complaint were a factor in the OCA's adverse

outcome of its administrative investigation. Being given the

copies would have forewarned respondent Judge about

every aspect of what she was being made to account for,

and thus be afforded the reasonable opportunity to

respond to them, or at least to prepare to fend off their

prejudicial influence on the investigation. In that context,

her right to be informed of the charges against her, and to

be heard thereon was traversed and denied. Verily, while

the requirement of due process in administrative

proceedings meant only the opportunity to explain one's

side,10 elementary fairness still dictated that, at the very

least, she should have been first made aware of the

allegations contained in the letters-complaint before the

OCA considered them at all in its adverse

recommendation and report. This is no less true despite

the similarity of the statements contained in the four

letters-complaint, on the one hand, and of the statements

contained in the verified complaint, on the other, simply

because the number of the complaints could easily

produce a negative impact in the mind of even the most

objective fact finder.

Moreover, the OCA's treatment of the four letters-

complaint as "supplemental complaints" was legally

unsustainable. The requirements for a valid administrative

charge against a sitting Judge or Justice are found in

Section 1, Rule 140 of the Rules of Court, which

prescribes as follows:

Section 1. How instituted. - Proceedings for the discipline

of judges of regular and special courts and Justices of the

Court of Appeals and the Sandiganbayan may be

instituted motu proprio by the Supreme Court or upon a

verified complaint, supported by affidavits of persons who

have personal knowledge of the facts alleged therein or by

documents which may substantiate said allegations, or

upon an anonymous complaint, supported by public

records of indubitable integrity. The complaint shall be in

writing and shall state clearly and concisely the acts and

omissions constituting violations of standards of conduct

prescribed for Judges by law, the Rules of Court, or the

Code of Judicial Conduct.

Based on the rule, the three modes of instituting

disciplinary proceedings against sitting Judges and

Justices are, namely: (a) motu proprio, by the Court itself;

(b) upon verified complaint, supported by the affidavits of

persons having personal knowledge of the facts alleged

therein, or by the documents substantiating the

allegations; or (c) upon anonymous complaint but

supported by public records of indubitable integrity.11

Only the verified complaint dated July 20, 2011 met the

requirements of Section 1, supra. The four letters-

complaint did not include sworn affidavits or public records

of indubitable integrity. Instead, they came only with a

mere photocopy of the denial of the Motion to Dismiss,

which was not even certified. The OCA's reliance on them

as "supplemental complaints" thus exposed the unfairness

of the administrative investigation.

Although the denial of respondent Judge's right to be

informed of the charges against her and to be heard

thereon weakened the integrity of the investigation, it was

not enough ground to annul the investigation and its

outcome in view of her admission of not having filed a

motion for extension of the 90-day period to resolve the

Motion to Dismiss.

Consequently, the Court should still determine whether

she was administratively liable or not.

2.

Respondent Judge's delay in resolving the Motion to

Dismiss was not undue

The 90-day period within which a sitting trial Judge should

decide a case or resolve a pending matter is mandatory.

The period is reckoned from the date of the filing of the

last pleading. If the Judge cannot decide or resolve within

the period, she can be allowed additional time to do so,

provided she files a written request for the extension of her

time to decide the case or resolve the pending

matter.12 Only a valid reason may excuse a delay.

Regarding the Motion to Dismiss filed in Civil Case No. 10-

9049, the last submission was the Sur-Rejoinder

submitted on December 16, 2010 by defendants-movants

SM Development Corporation, et al. As such, the 90th day

fell on March 16, 2011. Respondent Judge resolved the

Motion to Dismiss only on May 6, 2011, the 51st day

beyond the end of the period to resolve. Concededly, she

did not file a written request for additional time to resolve

the pending Motion to Dismiss. Nor did she tender any

explanation for not filing any such request for time.

To be clear, the rule, albeit mandatory, is to be

implemented with an awareness of the limitations that may

prevent a Judge from being efficient. In respondent

Judge's case, the foremost limitation was the situation in

Antipolo City as a docket-heavy judicial station. She has

explained her delay through various submissions to the

Court (i.e., the Comment dated August 25, 2011, the

Rejoinder dated January 20, 2012, and the Motion for

Reconsideration), stating that her Branch, being one of

only two branches of the RTC in Antipolo City at the time,

then had an unusually high docket of around 3,500 cases;

that about 1,800 of such cases involved accused who

were detained; that her Branch could try criminal cases

numbering from 60 to 80 on Mondays and Tuesdays, and

civil cases with an average of 20 cases/day on

Wednesdays and Thursdays; that despite its existing

heavy caseload, her Branch still received an average

number from 90 to 100 newly filed cases each month; that

the four newly-created Branches of the RTC in Antipolo

City were added only in early 2011, but they did not

immediately become operational until much later; that she

had devoted only Fridays to the study, consideration and

resolution of pending motions and other incidents, to the

drafting and signing of resolutions and decisions, and to

other tasks; that she had spent the afternoons of

weekdays drafting and signing decisions and extended

orders, issuing warrants of arrest and commitment orders,

approving bail, and performing additional duties like the

raffle of cases and the solemnization of marriages.

Under the circumstances specific to this case, it would be

unkind and inconsiderate on the part of the Court to

disregard respondent Judge's limitations and exact a rigid

and literal compliance with the rule. With her undeniably

heavy inherited docket and the large volume of her official

workload, she most probably failed to note the need for

her to apply for the extension of the 90-day period to

resolve the Motion to Dismiss.

This failure does happen frequently when one is too

preoccupied with too much work and is faced with more

deadlines that can be humanly met. Most men call this

failure inadvertence. A few characterize it as oversight. In

either case, it is excusable except if it emanated from

indolence, neglect, or bad faith.

With her good faith being presumed, the accuser bore the

burden of proving respondent Judge's indolence, neglect,

or bad faith. But Lubaton did not come forward with that

proof. He ignored the notices for him to take part,

apparently sitting back after having filed his several letters-

complaint and the verified complaint. The ensuing

investigation did not also unearth and determine whether

she was guilty of, or that the inadvertence or oversight

emanated from indolence, neglect, or bad faith. The Court

is then bereft of anything by which to hold her

administratively liable for the failure to resolve the Motion

to Dismiss within the prescribed period. For us to still hold

her guilty nonetheless would be speculative, if not also

whimsical.

The timing and the motivation for the administrative

complaint of Lubaton do not escape our

attention.1âwphi1 The date of his first letter-complaint -

May 18, 2011 - is significant because it indicated that

Lubaton had already received or had been notified about

the adverse resolution of the Motion to Dismiss. If he was

sincerely concerned about the excessive length of time it

had taken respondent Judge to resolve the Motion to

Dismiss, he would have sooner brought his complaint

against her. The fact that he did not clearly manifested

that he had filed the complaint to harass respondent

Judge as his way of getting even with her for dismissing

the suit filed by his principals.

In conclusion, we deem it timely to reiterate what we once

pronounced in an administrative case involving a sitting

judicial official, viz:

x x x as always, the Court is not only a court of Law and

Justice, but also a court of compassion. The Court would

be a mindless tyrant otherwise. The Court does not also

sit on a throne of vindictiveness, for its seat is always

placed under the inspiring aegis of that grand lady in a

flowing robe who wears the mythical blindfold that has

symbolized through the ages of man that enduring quality

of objectivity and fairness, and who wields the balance

that has evinced the highest sense of justice for all

regardless of their station in life. It is that Court that now

considers and htvorably resolves the reiterative plea of

Justice Ong.13

This reiteration is our way of assuring all judicial officials

and personnel that the Cout1 is not an uncaring overlord

that would be unmindful of their fealty to their oaths and of

their dedication to their work. For as long as they act

efficiently to the best of their human abilities, and for as

long as they conduct themselves well in the service of our

Country and People, the Court shall always be

considerate and compassionate towards them.

WHEREFORE, the Court GRANTS the Motion for

Reconsideration; RECONSIDERS AND SETS ASIDE the

Resolution promulgated on April 16, 2012; ABSOLVES

Hon. Judge Mary Josephine P. Lazaro from her

administrative tine of ₱5,000.00 for undue delay in

resolving a Motion to Dismiss in a pending civil case, but

nonetheless REMINDS her to apply for the extension of

the period should she be unable to decide or resolve

within the prescribed period; and DISMISSES this

administrative matter for being devoid of substance.

SO ORDERED.

You might also like

- Introduction To Criminal Justice Practice and Process 5th EditionDocument481 pagesIntroduction To Criminal Justice Practice and Process 5th EditionjosephfellizarNo ratings yet

- ETHICS - Col Lubaton Vs Judge Lazaro - Undue Delay PDFDocument7 pagesETHICS - Col Lubaton Vs Judge Lazaro - Undue Delay PDFJerik SolasNo ratings yet

- GR207377 DigestDocument3 pagesGR207377 DigestLito Lagunday (litlag)No ratings yet

- 7 Macapagal v. PeopleDocument5 pages7 Macapagal v. PeopleVince Llamazares LupangoNo ratings yet

- Motion For Reconsideration of A Winning Judge in A Dismissed Administrative CaseDocument11 pagesMotion For Reconsideration of A Winning Judge in A Dismissed Administrative CaseEBY Traders100% (3)

- Heirs of Amada Zaulda vs. Isaac Z. ZauldaDocument7 pagesHeirs of Amada Zaulda vs. Isaac Z. ZauldaRandy SiosonNo ratings yet

- Rubio, JR Vs ParasDocument4 pagesRubio, JR Vs ParasremleanneNo ratings yet

- Maravilla vs. RiosDocument7 pagesMaravilla vs. RiosJohn AguirreNo ratings yet

- Maravilla Vs Rios (G.R. No. 196875. August 19, 2015.)Document8 pagesMaravilla Vs Rios (G.R. No. 196875. August 19, 2015.)jtlendingcorpNo ratings yet

- 014 Sanico vs. PeopleDocument7 pages014 Sanico vs. PeopleJazztine ArtizuelaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 193217Document3 pagesG.R. No. 193217Abby EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- Oct 17 RecitDocument7 pagesOct 17 RecitBenedict AlvarezNo ratings yet

- 7107 Islands Publishing-StatconDocument4 pages7107 Islands Publishing-StatconFritz Frances DanielleNo ratings yet

- M4 RehearingDocument4 pagesM4 RehearingzonelizzardNo ratings yet

- Certiorari-People vs. GoDocument4 pagesCertiorari-People vs. GoRea Nina OcfemiaNo ratings yet

- Macapagal Vs People (2014)Document8 pagesMacapagal Vs People (2014)Joshua DulceNo ratings yet

- Gandarosa-vs-Flores-and-PeopleDocument3 pagesGandarosa-vs-Flores-and-PeopleKen BocsNo ratings yet

- Indispensable Party Not ImpleadedDocument9 pagesIndispensable Party Not ImpleadedChris.No ratings yet

- Diaz-Motion To Dismiss For: Quieting of TitleDocument3 pagesDiaz-Motion To Dismiss For: Quieting of TitleMaria RochelleNo ratings yet

- Gandarosa vs. Flores and PeopleDocument3 pagesGandarosa vs. Flores and PeopleTeoti Navarro Reyes100% (1)

- Maceda Vs Vasquez 2Document6 pagesMaceda Vs Vasquez 2Kristanne Louise YuNo ratings yet

- Encarnacion V CADocument4 pagesEncarnacion V CABen CamposNo ratings yet

- Afulgencia Vs Metrobank G.R. No. 185145Document7 pagesAfulgencia Vs Metrobank G.R. No. 185145Newbie KyoNo ratings yet

- Factual Antecedents: TEDDY MARAVILLA, Petitioner, v. JOSEPH RIOS, Respondent. Decision Del Castillo, J.Document5 pagesFactual Antecedents: TEDDY MARAVILLA, Petitioner, v. JOSEPH RIOS, Respondent. Decision Del Castillo, J.Anonymous himZBVQcoNo ratings yet

- Informations Were Filed Before The RTC Charging Respondent Pablo Olivarez With Violation of ofDocument16 pagesInformations Were Filed Before The RTC Charging Respondent Pablo Olivarez With Violation of ofEunice SerneoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 205492 Republic OF THE PIDLIPPINES, Petitioner, Spouses Dante and Lolita Benigno, Respondents. DecisionDocument6 pagesG.R. No. 205492 Republic OF THE PIDLIPPINES, Petitioner, Spouses Dante and Lolita Benigno, Respondents. DecisionMarianne Shen PetillaNo ratings yet

- Jimenez vs. Judge Amdengan Gross Inefficiency PDFDocument6 pagesJimenez vs. Judge Amdengan Gross Inefficiency PDFPeterD'Rock WithJason D'ArgonautNo ratings yet

- Afulugencia Vs Metrobank SubpoenaDocument12 pagesAfulugencia Vs Metrobank SubpoenaEthel Joi Manalac MendozaNo ratings yet

- People vs. Clemente BautistaDocument6 pagesPeople vs. Clemente BautistaIvy ZaldarriagaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 193217 February 26, 2014 CORAZON MACAPAGAL, Petitioner, People of The Philippines, RespondentDocument16 pagesG.R. No. 193217 February 26, 2014 CORAZON MACAPAGAL, Petitioner, People of The Philippines, RespondentsofiaNo ratings yet

- 25.quillopa vs. Quality Guards Services and Investigation AgencyDocument4 pages25.quillopa vs. Quality Guards Services and Investigation AgencyLord AumarNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 183398Document7 pagesG.R. No. 183398Abby EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- (Respondent), Which Originated From An Administrative Complaint Filed by The LatterDocument34 pages(Respondent), Which Originated From An Administrative Complaint Filed by The LatterJanine AranasNo ratings yet

- Maceda vs. Atty. Abiera, G.R. No. 102781, April 22, 1993Document4 pagesMaceda vs. Atty. Abiera, G.R. No. 102781, April 22, 1993Tim SangalangNo ratings yet

- EncaDocument5 pagesEncaLDCNo ratings yet

- Acuzar vs. JorolanDocument5 pagesAcuzar vs. JorolanedmarkarcolNo ratings yet

- Rule 6 10 New Cases Civ ProDocument29 pagesRule 6 10 New Cases Civ ProJeff Cacayurin TalattadNo ratings yet

- Factual AntecedentsDocument6 pagesFactual Antecedentsjmf123No ratings yet

- Lopez V Court of AppealsDocument1 pageLopez V Court of AppealsprgaiNo ratings yet

- Diu vs. CADocument9 pagesDiu vs. CAAnwrdn MacaraigNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 193158 Philippine Health Insurance CORPORATION, Petitioners, Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital, RespondentDocument5 pagesG.R. No. 193158 Philippine Health Insurance CORPORATION, Petitioners, Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital, RespondentkristinevillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Anson Trade v. Pacific Bank DigestDocument3 pagesAnson Trade v. Pacific Bank DigestJulian100% (1)

- Davies V Carillion Energy Services LTD and A PDFDocument20 pagesDavies V Carillion Energy Services LTD and A PDFRon MotilallNo ratings yet

- Pale Cases #2Document34 pagesPale Cases #2Janine AranasNo ratings yet

- TAGLAY V DARAYDocument5 pagesTAGLAY V DARAYMalaya PilipinaNo ratings yet

- (B7) 170125-2014-People - v. - Go PDFDocument4 pages(B7) 170125-2014-People - v. - Go PDFCYMON KAYLE LubangcoNo ratings yet

- 2014 - Afulugencia vs. Metropolitan Bank & Trust Co., 715 SCRA 399, G.R. No. 185145 February 5, 2014 - Remedial Law - CourtsDocument7 pages2014 - Afulugencia vs. Metropolitan Bank & Trust Co., 715 SCRA 399, G.R. No. 185145 February 5, 2014 - Remedial Law - CourtsDaysel FateNo ratings yet

- National Electrification Administration Vs CADocument2 pagesNational Electrification Administration Vs CAAnonymous 5MiN6I78I0No ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Case DigestsDocument22 pagesLegal Ethics Case DigestsMaria Monica GulaNo ratings yet

- 08 Sanico v. PeopleDocument9 pages08 Sanico v. Peoplefammy jesseNo ratings yet

- Litigant Preparing His Own PleadingDocument9 pagesLitigant Preparing His Own PleadingjoshNo ratings yet

- Magdiwang Realty Corporation v. The Manila Banking CorporationDocument3 pagesMagdiwang Realty Corporation v. The Manila Banking CorporationblckwtrprkNo ratings yet

- Motion To Dismiss Due To Fault of PlaintiffDocument3 pagesMotion To Dismiss Due To Fault of Plaintifffurry_attorneyNo ratings yet

- 09 Macaslang V Sps ZamoraDocument17 pages09 Macaslang V Sps Zamorafammy jesseNo ratings yet

- MARK MONTELIBANO v. LINDA YAPDocument12 pagesMARK MONTELIBANO v. LINDA YAPIldefonso HernaezNo ratings yet

- 20 MARK MONTELIBANO v. LINDA YAP PDFDocument12 pages20 MARK MONTELIBANO v. LINDA YAP PDFIldefonso HernaezNo ratings yet

- Viudez Vs CA June 5 2009Document12 pagesViudez Vs CA June 5 2009Jose Gonzalo SaldajenoNo ratings yet

- CLODUALDA D. DAACO, Petitioner, VALERIANA ROSALDO YU, RespondentDocument5 pagesCLODUALDA D. DAACO, Petitioner, VALERIANA ROSALDO YU, Respondentianmaranon2No ratings yet

- Supreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandSupreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionNo ratings yet

- California Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandCalifornia Supreme Court Petition: S173448 – Denied Without OpinionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Manangan Vs CFIDocument12 pagesManangan Vs CFIPaolo Antonio MacalinoNo ratings yet

- Maglasang vs. PeopleDocument11 pagesMaglasang vs. PeoplePaolo Antonio MacalinoNo ratings yet

- Panganiban vs. Guerrero (Neg)Document7 pagesPanganiban vs. Guerrero (Neg)Paolo Antonio MacalinoNo ratings yet

- OCA Vs Judge UsmanDocument8 pagesOCA Vs Judge UsmanPaolo Antonio MacalinoNo ratings yet

- Acharon V PeopleDocument1 pageAcharon V PeoplePaolo Antonio Macalino50% (2)

- DictionaryDocument2 pagesDictionaryPaolo Antonio MacalinoNo ratings yet

- Go V DimagibaDocument1 pageGo V DimagibaPaolo Antonio MacalinoNo ratings yet

- Lim v. PeopleDocument2 pagesLim v. PeoplePaolo Antonio MacalinoNo ratings yet

- Ivler V Modesto-San PedroDocument1 pageIvler V Modesto-San PedroPaolo Antonio MacalinoNo ratings yet

- Consolidated Crim Digests 083122Document13 pagesConsolidated Crim Digests 083122Paolo Antonio Macalino100% (1)

- Pobre and SantiagoDocument33 pagesPobre and SantiagoFriktNo ratings yet

- The 5 KIIT National Moot Court Competition, 2017 1 - PageDocument21 pagesThe 5 KIIT National Moot Court Competition, 2017 1 - PageRohit KumarNo ratings yet

- Ledesma vs. CA 9-5-97Document19 pagesLedesma vs. CA 9-5-97Karl Rigo AndrinoNo ratings yet

- Alvarez vs. RamirezDocument8 pagesAlvarez vs. Ramirezpoiuytrewq9115No ratings yet

- English Tort Law FicheDocument13 pagesEnglish Tort Law FicheelyssaarezkiNo ratings yet

- People v. EstenzoDocument2 pagesPeople v. EstenzoSophiaFrancescaEspinosaNo ratings yet

- 1200 Tough WordsDocument23 pages1200 Tough WordsroshannazarethNo ratings yet

- Francis Kelly V HMADocument12 pagesFrancis Kelly V HMASzymon CzajaNo ratings yet

- Assignment On: University of ChittagongDocument7 pagesAssignment On: University of ChittagongNoobalistNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Bar Questions and Answers 1Document44 pagesLegal Ethics Bar Questions and Answers 1Dionicio G. Sanchez100% (1)

- Uttar Pradesh Civil Laws Amendment Act, 1970Document7 pagesUttar Pradesh Civil Laws Amendment Act, 1970Latest Laws TeamNo ratings yet

- Leslie E Kobayashi Financial Disclosure Report For Kobayashi, Leslie EDocument12 pagesLeslie E Kobayashi Financial Disclosure Report For Kobayashi, Leslie EJudicial Watch, Inc.No ratings yet

- People v. Lacson, October 7, 2003Document21 pagesPeople v. Lacson, October 7, 2003dondzNo ratings yet

- Curtis Warren Case JudgementDocument26 pagesCurtis Warren Case JudgementEcho NewsroomNo ratings yet

- Rem SCRA IndexDocument90 pagesRem SCRA Indexkrystel engcoyNo ratings yet

- CSL 2601 DiscussiondocumentDocument17 pagesCSL 2601 DiscussiondocumentDAWA JAMES GASSIMNo ratings yet

- In RE Joaquin T. Borromeo. Ex Rel. Cebu City Chapter of The Integrated Bar of The Philippines A.M No. 93-7-696-0 Feb 21, 1995Document51 pagesIn RE Joaquin T. Borromeo. Ex Rel. Cebu City Chapter of The Integrated Bar of The Philippines A.M No. 93-7-696-0 Feb 21, 1995bogoldoy100% (1)

- Carino V CHR (Digest)Document2 pagesCarino V CHR (Digest)JohnAlexanderBelderol67% (3)

- Bacalso vs. Ramolete, 21 SCRA 519 - FULL TEXTDocument3 pagesBacalso vs. Ramolete, 21 SCRA 519 - FULL TEXTMctc Nabunturan Mawab-montevistaNo ratings yet

- Baltazar V People, G R No 174016, July 28, 2008, 582 PHIL 275 294Document12 pagesBaltazar V People, G R No 174016, July 28, 2008, 582 PHIL 275 294Jett ChuaquicoNo ratings yet

- Legalaid PDFDocument2 pagesLegalaid PDFNicole RichardsonNo ratings yet

- NoticeDocument293 pagesNoticepriyadarshi manishNo ratings yet

- INTA Table Topic Outline - TTAB Hearings: Tips For Oral ArgumentsDocument5 pagesINTA Table Topic Outline - TTAB Hearings: Tips For Oral ArgumentsErik PeltonNo ratings yet

- The America BetrayalDocument4 pagesThe America BetrayalAllen Carlton Jr.100% (2)

- Accord Coi Compilation Pakistan August 2016Document295 pagesAccord Coi Compilation Pakistan August 2016Dana CăpitanNo ratings yet

- HK Risk Assessment Report - e PDFDocument132 pagesHK Risk Assessment Report - e PDFVintonius Raffaele PRIMUS100% (1)

- Draft Opinioni I Komisionit Të VeneciasDocument22 pagesDraft Opinioni I Komisionit Të VeneciasNewsbomb AlbaniaNo ratings yet

- An Overview of The Japanese Legal SystemDocument24 pagesAn Overview of The Japanese Legal SystemNakaoka RicardoNo ratings yet