Professional Documents

Culture Documents

02 - Crystal - Parts III-IV

02 - Crystal - Parts III-IV

Uploaded by

Swati Rai0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views96 pagesn

Original Title

02_Crystal_parts III-IV

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentn

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views96 pages02 - Crystal - Parts III-IV

02 - Crystal - Parts III-IV

Uploaded by

Swati Rain

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 96

Senco acon gece

take completely for granted. We are so used to

speaking and understanding our mother tongue

with unselfconscious ease that we do not noti

Pe ee rete ett eet ee

Peco ee arn ed

Peer nmr ten a end

encounter the structural compl

ORC

language as an adult, we are often amazed at the

level of diffi

erent

ty involved. Similarly, when we

bility to control the struc-

Re cae canons

cap. Such instances suggest the central impor-

f BES

eet ae

tance of the field of lingu

to such specialists as teachers or therapists, but to

PR eR Ree eon Ck

phenomenon of languag

rer nen ku

Pte nnn

ee

Perry

cr

of sounds and words must be one of confusion;

other. T

ee en oe

eens will gradually

emerge. Some words will stand out, and so

erent ce eer on

y be recognizable, The pronunciation will

become less alien, as we detect the melodies and

The structure of

language

thythmical patterns that convey such info

as ‘stating’ and ‘questioning’. W.

8h

Preity

eee

eon

Seema

of foreign-language publicat

ee eat eon

Seen e nen

Instead of sounds and thythms, we are now

h shapes and spaces: but the principle

Perna

Pen eet eR

forms, many of which are expressing similar

rt

Ren eee nan

fren ero

In this part of the encyclopedia, we therefore

ructure

ne the factors involved in carrying outa

Peet ee eee one ene cn

written, or signed, and illustrate the main compo:

orlevels, that linguists have proposed in

ae

rere ter tee aes er

The largest section will be devoted to the field of

grammar, which is at the centre of most ling

eon test toner cons

to semantics, the study of meaning in language,

and to the associated themes of diction

al

review of some general issues that form part of

aoe

Pree

Eee

Poe htt oy ern Cnn enc on

question of whether all languages have properties

in common, Parti concludes with PY oy

eek cnc nO CLA as

Pen ene ccc C UMMC

mera or onan oa

SE

3 LINGUISTIC LEVELS

a es i;

on ina piece of speech, writ-

oo pettus co describe its characters:

ing Ser rape sarment, Even in a shor

Ms centence such as Hello there, several things

SPO at once. Each word conveys 2 particular

Phere is roo much going ©

a ere a in which the words

rere is a likely order in whi

moaning, There id noe say There bell! Each word

ayaa apeic sequence of sounds, Thesen-

aac ava whole is uttered in a particular tone of voice

ieeodyaonled i ing tug te exclamation

hark (629). And the choice of this sentence immedi-

rans crains the oceasions when it might be sed —

oon a frst meeting (and not, for example, upon leave-

taking). While we say or hear the sentence, we are not

‘consciously aware ofall chese facets ofits structure, but

‘once our attention is drawn to them, we easily recog-

nize their existence. We could even concentrate on the

seudy of one of these facers largely to the exclusion of

the others — something that takes place routinely in

language reaching, for instance, where someone may

eee arnacddot one day, and of

‘vocabulary’ or ‘grammar’ the next.

Selective focusing of this kind in face takes place in all

linguistic studies, as part of the business of discovering

hhow language works, and of simplifying the task of

description. The different facets are usually referred to

as levels oF linguistic organization. Each level is studied

using its own terms and techniques, enabling us to

‘obcain information abouone aspect of language struc-

ture, while temporarily disregarding the involvement

of others. The field of pronunciation, for example, is

basically analysed ar the level of phonetics, using proce-

that are quite distinct from anything encoun-

tered at other linguistic levels. When we do phonetic

research, we try to disassociate ourselves from the

problems nd practices we would encounter if we were

‘carrying our a study at the level of, Say, grammar. Simi

srammatical study takes place using approaches

that aze in principle independent of what gocs on in

Phonetics. And other levels likewise, provide us with

their own independent ‘lant’ on the workings of len.

‘age structure.

{fhe noon of eves is widely applicable, expecially

me engage inthe analysis ofa fangeoflanguages

asitenables us to see and state patterns of organization

ima tas any other way thathas

ci dine appear to have a certai

“empitical ‘ a

fe as neta and neatologil

seen Ace wes

‘study, weare ined geo 2 level for independent

lucing an artificial element into our

enquiry, whose consequences mustbeanticipated. The SPace sy &

sais of speech that we study via phonetics are, afer UNGUIgST®N

Sil the substance through which the paternsof yram- inwygy,o. P

ange are conveyed. There will therefore be interrela-

tionships between levels that need co be taken into

sccoune ifwe wish co understand the way language asa

whole is organized. As with any structure, the whole

tannotbe broken down into its constituent parts with-

ut loss, and we must therefore always recollect the

need to place our work on individual levels within a

more general structural perspective.

HOW MANY LEVELS?

Ieis not difficult to sense the complexity of language

seructure, but it is not so easy to say how many levels

should be set up in order to explain the way this struc-

ture is organized. Some simple mocels of language tec-

ognize only two basic levels: the set of physical forms

(sounds, letters, signs, words) contained in a language,

and the range oF abstract meanings conveyed by these

forms, More commonly, the notion of forms is subdi-

vided, co distinguish different kinds of abstracuness. In

speech, for example, the physical facts of pronuncia-

tion, as defined by the processes of articulation, acous-

tictransmission and audition, are considered to be the

subject matter of phoneries (§27). The way different

languages organize sounds to convey differences of

meaning is the province of phonolygy ($28). And the

study of the way meaningful units are brought into

sequence to convey wider and more varied patterns of

‘meaning is the province of grammar. The term seman-

siesis then used for the study of che patterns of meaning

themselves.

Four-level models of language (phonetics / phonol-

ogy / grammar / semantics) are among the most widely

used, but further divisions within and between these

levels are often made. For example, within the level of

grammar, it is common to recognize a distinction

berween the study of word structure (morphology) and

the study i

¢ study of word sequence within sentences (sya)

sin te Pion om

ts, an ental phonol is usu

distinguished from the study of Pee cue

{ones of voice (suprasegmental phonology) ($29)

Within semantics, the suid of vocabulary or lexicon

areetimes taken separately from the study of larger

ig (under such headings as text or

levels ofstruceana 1 ese te tepularly referred co as

_We could continue,

Sons, and recognizing

making divisions within divi-

more subdle

nN

eptesenteg gt

the whole wt f

complerst eng

rose tain

otuniteasse)

torture

Gaulle iporignt

auistsmap tea

yee wa

acestoalonee

this tespect tei

bearsastriing a?

tothesaraiag

Clarkes 010

Key

L Linguist

Morphology

Phonetics

! Phonology

S Syntax

SI Semantic.

(© Other levels

| ==

a vastarray

Why should

jon is to

ofthe world present us wid

ae a ad diesen, Why

oo ay cof answering this qu‘

this beso? One 2) ives investigating the origins

adopea histori Pengo the importance of inguls-

Flags 2nd x,

ea perspective that is dis

a reproach sro make a dealed descrip

: f

pnaOf the smiarites or differences, regardless

on si antecedent, and proceed fom sees0

everalize abou the structure and fanction of human

eee two main vays of approaching ths latter

task, We might look for the structural features that all

‘or most languages have in common; or we might focus

four attention on the features that differentiate them.

Inthe former case, we are searching for language uni-

rersals in the latter case, we are involving ourselves in

language npology In principle, the two approaches are

complemencary, but sometimes they are associated

swith differen theoretical conceptions of the nature of

linguistic enquiry

SIMILARITY OR DIFFERENCE?

Since theend ofthe 18th century, the chief concern has

been to explain the nature of linguistic diversicy. This

was the focus of comparative philology and dialectol-

‘ogy, and it led to early attempts to set up genetic and

structural typologies oflanguages ($50). The emphasis

‘carried through into the 20th century when the new

science of linguistics continually stressed the variety of

Janguages in the world, partly in reaction against the

iaions of 1h-centry prescrip, where one

language, Latin, had been commonly te

svadartofccelene(S), ps

ince the 1950s, the focus on diversity has been

telaced by esearch paradigm, stemming fom the

Toes. te American linguist Noam Chomsky

HSE, in which the nature of linguistic universae

lds a central place. Chomsky’s generative thy

HBUage Proposes a sin ha

_ ; ile set of rules from which all

the grammatical semtencesinalanguage can bederh

{P.97)-Inorderto define these rules in an accurate cet

ere vay, grammar has to rely on certain soy

fenPancpls = absraceconseaints hat goer he

pias nd cg se

‘operates. In thi BG

sige a ieee pet

aa — proper-

Fologially necessary and thus innave

Important, it is

leepensour underst,

beeen

1g. TYPOLOGY 4

essential first step in the task of understanding human

tellecrual capacity: :

Jv Chomsky’s view, therefore, the aim of linguistics is

to go beyond the study of individual languages, to

decermine what the universal properties of language

ste and to establish a ‘universal grammar’ that would

fccount for the range of linguistic variation thar is

humanly possible. The question issimply: Whatare the

limits on human language variability? Languages do

hot make use of all possible sounds, sound sequences,

be word orders. Can we work out the reasons? It might

be possible to draw a line between the patterns that are

casential features of language, and those that no lan-

guage ever makes use of (p. 97). Or perhaps there is a

‘continuum between these extremes, with some features

being found in most (but not all) languages, and some

being found in very few. Questions of this kind consti-

tute the current focus of many linguists’ attention.

‘THE PORT-ROYAL GRAMMAR

Contemporary ideas about the

‘nature of linguistic universals

have several antecedents in

the work of 17th-century

thinkers. The Grammaire

générale etraisonnée (1660) is

‘widely recognized as the most

| influential treatise ofthis

period. ttis often referred to.as

‘the Port Royal grammar’,

because it was written by’

scholars who belonged to the

community of intellectuals and

ND UNIVERSALS

CONTENANT =

Les fandemens de Partde parlers ex

Pe ea

EXPRESS)

ING.

cor

me

Seuclon nate

ima toh

2a

of compara

and the stands

son(h eat

is shared by may

including Bete

thai, Swahili, Th ©

Zapotec, ms,

However, the op

overran

of comparison iseres.

fist, salsocommenns

ee

protean

big’), and this way of,

eileen

Burmese Co

ae

Samet at

"GRAMMAR

GENERALE

JET RAISONNEL

tegiousetiashedtetwcan Zl raf de ce qui of command

{627 and 1650inPor-Royal, eg ernie

Although published anony-

‘ously the authorship of the

Grammarhasbeen ascribed to

‘laude Lancelot (1615-95) and

Antoine Arnauld (1612-94). fs

Subtitle, referring to ‘that. .

Whichis common toalllan- j

‘guages, and their I &

diferences. provides eat ‘

summary ofthe current preoe-

Sybation with universals an! A PARIS,

logy. However, the

‘eombolnsealoaviis | Che Pex na

Tecercmaemmice | Cunaareaa sa Rael

‘tyandmorewntnis a

arbitrary properties. MDG LX,

oR DEPTH?

H va typological and universal

erween (yPolOB ise

naion Pee cud is doubtless uleimately

mah 2 a both have considerable insights

I ia me roaches, as currently practised,

7 wo APP

8 the procedures. Typologiss typically

weer agesas part of their enquiry,

wide oe izations that deal with che

sie co me jcrure, such as wor

ied © ie pcs of stich a8 word

Bre ies anc pes of sound In contrast

et WON Cee breadth of such studies, universal-

wi se eh aude of single languages, espe-

Iv — English, in particul;

elon Se amar — English, in particular is

sind ae “fF exemplification ~ and tend to

Sennen angi Spout the more absteact, under

gee jes of anguage

prov’ on single languages might at first scem

Ts fo grein for universal, chen surely

r ady many languages? Chomsky argues,

cane.

ob 0

see har there sno paradox, Because English isa

once i ms herefore incorporate uni

ff mero nae aswell as chose individual

SPesmake it specifically ‘English. One way of

ino aout these propertics, therefore, is the

‘Folesudy ofsingle languages. The more languages

edu inco our enquiry, the moredifficul it can

[eat osee the cena feacures behind the welter of

andl differences.

(athe other hand, ir can be argued that the detailed

uhofsngle languages is inevitably going to produce

‘sored picture. There are features of English, for

ape ha ae notcommonly met with in other lan-

tug suchas the use ofonly one inflectional ending

Se ptesent sense (third-person, asin she runs), or the

‘benceofasecond-person singular / plural distinction

(Frac rout). Without a typological perspec-

‘seamesyitisnot possible co anticipate the extent

Dowich ou sense of priorities will be upset. If lan-

2p were relatively homogeneous entities, like sam=

tia ion ore, this would not be a problem. But,

‘slog argue, languages are unpredictably irregu-

fi2didosyncavc, Under these circumstances, 2

Seay tran depeh, indesirable

RELATIVE

ee OAS OL UIE a:

inagltlitidel isto beable vo make succinct and

full Statements that hold, without exception,

Salem rate, very few such statements

thiwfeg HeStcincc ones often seem to state the

gin languages have vowels: and the intet-

ledijagia £10 require considerable techni-

A te ea the time, in fact, i is clear

AS regu or ePtionless) universals donot

elnce att lingisslook instead for trends

inate given gen aBe8 ~ ‘elative! universals ~

3 tts expression. For example,

guages whose word order has been

THREE TYPES OF UNIVERSaLs,

Substan

is needed in order to anal retract

faneeed| to analyse a language, s Shout

{Buon ist-person,antonyms aetna eu

languages ave nounsand vowlsrine ore

ings pepertion, or hen a

thee areserlspranglinstonent

vewetandconnarena greets

Colconsiderationsmustakobebaramnmar nee

Stagesnaveworde thesnweriovennfeatl

Sunde

ple and

the range of

Formal

Formal universalsare ast of abstract conditions hat

ern thewayinuhina language snisan seas

‘the factors that have to bevwritten nto agar itis

to account successfully forthe way sentences work In

language. For example, because alanguiges make state:

iments andl ask related questions uch a The cariready

Isthecarready?), somemeanshasto be found to snom

the relationship between sch pis, Mostorammars

drive question structures from statementstructres by

some kind of transformation inthe above example,

‘Move the verb tothe beginning ofthe sentence itis

aimed that such transformations are qacessary in order

tocarry outthe analysisof these (end other kinds of struc

‘tures, as one version of Chomskyan theor does then they

would be proposed as formal universas. Other cases

include the kinds of ules sed ina grams othedite

tent levels recognized by a theory (613.

Impictional

tat sabayine theo then

(Rerintenonbengtotnacancaretone

the ne te pope of bg fa at

aac ene roped nates te

Be ee espn Greenberg 31] a>

lows

Unies 7 nove mara

ives agen demnancore VSO

freer ena te ec att te

subject or object noun agrees

Universal 3. eltes te bie fv ates

‘with the verb in gender. then

‘with the noun in gender F

sender categories in he

Universal 43 falanguage #5 3 etn

eae gender categories te PION

nal statements

mes

HOW any.

Uwcuaces?

Wie

mBOLbiein rin

5 human

‘mower toting out

iver orthesgy

mgood,

‘of bredcting what lang

coat

nicarateae

mackie,

sacniescreree

cane,

Seer

eed

saree

eure,

sonia

oom

ae

oe

seule

es

lat

0

umber of languages within

each famiyrastobecare:

{uly considered. would nat

berighttoselec an abivay

five languages remeath

fami bearing inn that

Indo Paci for era bas

‘over 700 languages whereas

‘Draviion has ony about2s

(52), The languages of New

Guineacught satay

Speaking to constitute aout

20% of any sample

Inpractce, sureshaveto

beatified ith seathe

canget Asfew ofthe Neo

{Guin languages hae bee”

k ic structure (s13),

Within 297 irs that occult,

sible co count the different oe that phere ae

posible co is eo May

ammat 8 ound system, and

cae res irae en suid in this was a

vig ering pacers ave merged: It has even

been possible ro propose statistical properties chat are

Peommon co all languages: these are sometimes

refersed | oas statistical Jawsor‘ universal.

fe gular ase independent of speaker 0°

voter oraubject mace While ina sense we ae free 60

By wbacrer we want in

practice our linguistic

Prhmiour conforms closely co statistical expectations

sel of linguist

of the letters 0!

frequency ©

different sty

‘sten, 1969, P-

wetting, (

average rank ord

gories of

as (¢). Column

Morse (1791-18)

His frequency ordering

type found ina

|

rders foun

vies of American Engl

21): (a) press

(¢) scientific writings

cr, based on a dest

printers

ext totalling ove

(0) gives €

72) in compl

repo!

the alphaber. Here is a selection of

¢ in one comparative study of

ish (after A. Zetter-

ring, (b) religious

(d) general fiction. The

ion of 15 cate-

‘+a million words, is given

he order used by Samuel

ling the Morse Code.

was based on the q

office (sce column (g))-

juantities of

Mian oy wi condense hac we wie 2 98

Engh, ic is alos lays going to be followed by Gaps 9

fae hot aiways becuse Ig adobe op FFE ee ~—«(12,000

tons. Lexus buteqlyconfdent)y seers er eet st 9,000

Bch eos 2 e 2 a a 2,000

afconsnans and jut under 40% of vowels, About 8» eis eee or

Feige wees pac wil fig ee nat eae ore

havethestructuie ofconsonant + vowel s consonant,as = 5 ee gs 8000

Peco emwiiniele hh oh i 4 so

Beene rdsinthelan- hh h A e400

we scape (t oferhinge We rot ' ee 6.200)

_ lieemaiable ingaboursuchfactsisthar, while © 2 5 | oy oe

‘engaged in communication, we do not con- fp ‘ a v ‘ oon

fees Caspar ‘our language to ensure that these sté oe - am é 2 3000

tistical properties obtain. It would be impossibl fae dees tae " 300

seers ibe co oe eee ek ey P2300

ae ci SF part, we . 2,500.

ae eee ig regularities in any large wy ey zo

oo iri ef i

re spec of wing The suly of tse g lucene at 4

ee etn bobo ow bk OB 11700

eee ey 1,600

ee UENCY ae t ‘eoo

ne of the simplest demonstrat x ae x oe

eettcsinplardemonsiaon oscil mgu- § ek ee ; a

a

i

Rank : : “

Fa Wetten

wets cme este

2 ky oa ihe _ Pin fienci German cen. Se

Pee os oo

5 les i in . ees sich . yes

Met > : 2: 8 & =

Meet PEE FE

fo ute) ton was ae eee ee ist Re 7

ae: ¢ that i Qui it =

ee om OE » sh es =

2. article se - as.

P-Pronouny Sh is Dor his have

or

MONos¥U

POLYSYLLANeS

The mostregam

rmonosplabe tase fo

Gearlyseennasspe

telephorecoweagy, —&°

Therewerefennang CO

ormoresilabicnina 3

‘most frequenyears

words. (AfterN.R Fret, =

31,1530)

ts

li ll

|S aw |

fe

|

all

\E 00 |

& /

fg 0p)

ez / Numbers

| =

an

se

| Kiniew

| sie

LexicaL Tor TWA

“The 20 most freqved™,

occurring words

of newspaper writ

English, French, nde

fre shown (after? MM

jewet al, 1968). Fore

eon the ast columns

ison Frequent worsi"

Tondon-Lund cosich

en conversation 04"

The importance

speech writing dist

evident: note the

Sti yes and welts

English, and the oc

of DDR (‘German

Republic) in the

LAWS

i ions of the existence of

~ fine demonstrat =

fit fpulaiies in language was cartied

pa 2 an philologist George Kingsley ZipF

Fie pest known law’ proposes a constant

50) en the rank ofa word ina frequency

penne with which ic is used in a text. If

athe validity of the law, you have to

veh

One ii

yo at allowing operations:

aie

tee instance (‘okens) of diferent words

Con vest the 364, 5251, tabled, et

np) nae escending rank order of frequency,

Pac mach rank a number ~ (1) the 364, (2) i

B13) of 166,

Be rank numb (by the frequency (9,

ithe esuleis approximately constant (C).

1

(ops

seresale te ist below gives the 35th, 45th, 55th,

‘Rie and 75th most-frequently occurring words in

ee aregory of the London—Lund corpus of spoken

eversation (conversations between equals/disparates,

Sts, 175,000 words). The values come out at

sround 30,000 each time.

7 nd

B wy we

4% see 674

55. which 563

65 get 469

out 422

Inother words, the relationship is inversely propor-

somal and ie was thought to obtain regardless of sub-

jax mater, author, or any other linguistic variable.

Howes, it was subsequently shown that the relation-

LENGTH / FREQUENCY RELATIONSHIP

Terdationship of syllable length and frequency of occur

‘we was chartered in a study of nearly 11 million German

wers[ofterE W. Kaeding, 1898).

Naser

abies

Numberofword Percentage

ord occurrences of whole

7

2 5,426,326 ‘376

: 3,156,448 28.94

‘ vatoa9a 1293

5 646,971 593

5 167,738 12

H 54436 050

f 16,993

5 5.038

” 4,225

y ‘461

2 5 022

a 5

het B

8 2

Se i

CAL'STRUGTURE OF Laney

TR ANGUAGE

ship does not obtain

5.920 times (f= 5,920), and

summarized a5 fr jueng

iamitied s fr = Ch a iwc at

curve has been found in roy engages cuca

ina French word-frequency book the 16h ne

sed Sr yea ek

(51,600), and the 1,000th, 31 times 1,000).

OTHER RELATIONSHIPS

pt also showed that there is an inverse rl

between the length of a word and ie fey

English, for example, the majority of the commonly

used words are monosyllables. The seme relationship

‘obtains even in a language like German, which has &

marked ‘polysyllabic’ vocabulary. This effect seems to

account for our tendency to abbreviate words when

their frequency of use rises, e.g. che routine reduction

of microphone to mikey radio broadcasters. I would

also seem to be an efficient communicative principleto

have the popular words short and the rare words long,

Factors such as efficiency and ease of communica-

tion appealed strongly to Zipf, who argued fora princi-

pile of ‘least effort’ co explain che apparent equilibrium

berween diversity and uniformity in our use of sounds

and words. The simpler the sound and the shorter the

sword, the more often will human beings want co useit

There ate, however, soe dle fing th

‘explanation (e.g. how to quantify the ‘effort involve

imarculaing sounds, andthe exceptions the law

referred to above), and today a more conventional

explanation in terms of probability theory is accepted.

TAKE A TEXT, ANY TEXT.

Takea text anyan-

‘guage, and count the

‘words, Order the words in

terms of decreasing fre-

‘quency. According to.one

Statistical prediction, the

semples, however, consider-

ablevariation from these

‘sso, the ype of text

corpuswilaffectthe

esis: nthe Lancaster

Jo! Bergen corpus fOr

fist 15 wordsal acount 080/636 ON

for25%ofthetert. The example tie 9

first 100 words will account

for 60%; and the first 1,000

for 85%, The frst 4.000 will

‘account for 97.5%. Inshore

words (after. Johansson

BK. Hofland, 1989, p-415)

DICTIONARIES eer

rasan creme ae

fue sf meanings {m) is

have oe saare often

6. K.Zipf (1902-50)

SYLLABLES

este edog

sore spe rei

trarstbek Mane

Sundar between he

lable Youshoue rath

{2sjlabesmakeup2sot

theseee iv

teh. fe,

‘ne Gee apse or

‘eanserpion atthe

speech lus ony Pier

trtsylabesSuttoacoune

{or30%ofteapeeth you

vilineed recognize aver

‘2o0eylabiesype Bs

tioneroates po

Spoken sates ur up

‘on average every 14 syllables

(after Beney 1923)

_—

16° GRAMMAR

eS... tC

role played by gram-

isdifedcwaperee cen es by using

mar in the SITUCTUTe ane or ‘sl n’. But

por such 25 framework of ‘skeleton, O°

am voor can express satisfactorily d

no physical metaphor ee ab aece

tnulifarous kinds of formal pavtening and abstiac

ai donshp thacare brought Co lghtina grammatical

aa eps can sully be distinguished in the study

of gaminar. The fis step isto identify units in che

sereamof pec (or writing, orsigning) ~ units such as

‘word and sentence’ The second step isto analyse the

pavers into which these units fll, and the relation-

ships of meaning that these patterns convey. Depend-

ing upon which units we recognize at the beginning of

the study so the definition of grammar alters. Most

approaches begin by recognizing the ‘sentence’, and

‘grammar is thus most widely defined as ‘the study of

Sentence structure’, A grammar of a language, from

this point of view, isan account of the language’ possi-

Sere organized according to certain

‘general principles. For example, in the opening page:

of the most influential grammatical Rete of ex

times, the American linguist Noam Chomsh

UE retettharsgrmincist device

for producing the sentences of the language under

analysis (1957, p11), to which is added the rider that

the sentences produced must be grammatical ones

sghubleto the native speaker -

ithin this general perspective there is room fe

mae pee Positions, In particular, there are wo

Ming Nt apPlictions of the term “grammar,

general one. The spe

SIX TYPES OF GRAMMAR

edagogleal grammar _Abook cifically designed

Foteusingeforegnianguage, or fr developing an

IMaranessel the mather tongue, Such ‘teaching gram

mar ate widely used in schools so much sothat many

peoplehovecnlyone meaning forthe term ‘grammar'a

‘rammar book

Prescriptive grammar A manual that focuses on

constructions where usage is divided, and lays down rules

{governing the socially correct use of language (§1). These

‘grammars were a formative influence on language atti-

tudes in Europe and America during the 18th and 19th

«centuries. Their influence lives on in the handbooks of

Usage widely found today, such as A Dictionary of

‘Modern English Usage (1826) by Henry Watson Fowler

(1858-1933).

Reference grammar A grammatical desc

Imatical description that

‘ties to be as comprehensive as possible, so that it can act

4382 reference book for those interested in establishing,

European gammeranseeoo eck

ped handbooks of type

inte ar20h century haber roars fe

we

shai

wren ey

Werest in the stud f

Ne history of linguistic

*2

Symbols in mega

icalanaiyss aga

seein

thatitisofdoua

‘aticalty Foren

isnodoubt teat

ungrammatiain

"Who and why in

*That book ook iy

ut the sts

ing sentence

Bothareinuse yrs

something odin

Don't forget ous

Books

This is the ca ofthe

(One of the main ain

uistic analysis toi

‘the principles enables

decide the granmac

sentence,

‘SO MUCH GRAWIME

A LANGUAGE

Probably the rasta

mar produced:

uage:A Compre

Grantee

Language (1985) by

Randolph Quits

Greenbaum Geof

‘and Jan Svertvik.Te3”

(of detail ints 4.77908

comes as asurprst'o™

people who, vests

traditional focusongt

as a matterof vo

have been broushtve™

think of Engliest a

guage lacking ng

But this book stander

shouldersof even™

detailed trestren

of the language:fo

‘end the alone

Tanted a 2003085

(P. Christopherson

eee

s CREATING

mars taught people to ‘parse’, or ana-

nce, BY making ais of divisions wishin

anne be cow, for example, would be divide

t i met ibe man), and a ‘predicate’ (saw the

ine pe predicate would then be divided into its er’

cath To Tre object’ (she cow). Other divisions would

(sa) 27 until all the features of the sentence had

ot be ma ’d, It is an approach co language that

2 ie call wth distaste. Grammar, for them,

.d frustrating subject. Why should

ARSE ian

Pe iio

cy peo rca

0 fy boring 28

-al reasons. All too often, in the tradi-

insufficient reasons were given for

ona gamma insu ee

amarticular sentence analysis. As a conse

aking 2 Pvommon to find children learning ana-

que etnitions off by heart, without any real

tee anding of what was going on. In particular,

they had to master the cumbersome, Latin-based

tganmatial terminology a8 an end in itself (terms

eh at accusative, ‘complement’, apposition’), and

tony ito examples oflanguage that were cither arti

Gily constructed, or taken from abstruse literature, Ie

‘was all at a considerable remove from the child’s real

Janguage world, as found in conversation or the media.

Linfearempt was made co demonstrate the practical

usfulnes of grammatical analysis in che childs daily

life, whether in school or outside. And there was no

interest shown in relating this analysis to the broader

principles of grammatical pacterning in the language as,

awhole Ie is not surprising, then, thar most people

‘who were taught parsing in school ended up unable ro

see the point of the exercise, and left remembering

gammar only asa dead, irrelevant subject.

‘The reality is quite the opposite. The techniques of

grammatical analysis can be used to demonstrate the

tnormous creative power of language — how, from a

Fite ec of grammatical patterns, even a young child

can express an infinite et of sentences. They can help

usall to identify the fascinating ‘edges’ of language,

where grammaticality shades into ungrammacicality,

and where we find the many kinds of humorous and

‘lamatic effets, both in literature and in everyday lan-

‘Sage (p. 72). As we discover more about the way We

‘ich use grammar as part of our daily linguistic sur-

‘al, we inevitably sharpen our individual sense of

20% and thus promote our abilities to handle more

sanelex constructions, both in speaking/listeningand

ane! rting, ‘We become more likely to spot

Tints ad lose constructions, and to do some-

ad gt. Moreover, che principles of grammati-

any [ease general ones, applicable to che study of

Leyatts8s So that we find ourselves developing &

neue Of thesimilarties and differences becween

ar atl many kinds of specialized problems

luminated through the study of grammar ~

culties facing the language-handl

guage learner, or the translator

16» GRAMMAR

Grammar need not be

alive, relevant,

fet be dy une, sane: it an be

itdepends only on how ie puree ay bes

| cram

the following way. Ahypothetca prc ana omerin

| oa nares aaron

beat Te hn olem hema y

pentane eres,

woyooeearrenanstentoey cag

[Apage from Maureen Vidler' Find a Story (1978) The

ape sat roncontaly sotharareach pis tured ove, 2

en sentence and pcre reils On the next page fo

Meese hep strip reads Meg hess goy bonnet andthe

ottom one‘aniong,shorpteth Thereare ony 12p9ge1

orth book ut there are ver 20,000 posible grammatical

oeGinotns na simiar approach (Rolla St), the cs

okey aserterceby lings sees os on which wars

rane ace prnted. Such proaches ean entetaiing

nave pengvounsclarasaertonosertene

frrctre Grammar can at mes, bef,

POODLES WEARING

JEANS?

isnot difeut to thinkup

dramaticor entertaining

Sentences that would moti

vateachldto cary out

‘rammatial anal

because ol ther ambiguity

orstysticetiect Here are

Some nice cases of smbigu-

"taken rom. Mitra,

‘Grammar of Modern

English (1962, all of which

an be explained throughe

single principle

The gir as followed bye

smal poate wearing jeans

Next came. mother mitha

very small baby who was

pushing a pram.

‘aivays buy my newspapers

at theshopnext to the police

Station in whieh cards maga.

Zines and fancy goods are

splayed.

Acailorwatdancing with

‘wooden leg

Ineach case, the construc:

tion at the endof the sen:

tence has been separated

‘rom the noun towhichit

belongs. fone wished to

void the unintentionally

humorous effets, tne

sentences would need to

be reformulated with tis

Construction immediately

following. or ‘postmodify-

ing’ the noun (The i

wearing jeans...

pART IT

rue STRUCT!

RE OF LANGUAGE

Be LEMS

e Orr re ed into mosphere 0 es

ori Jot all words can be analy om sie

MATICAL NOTIONS | Noval wer example, ti dike ow

2 am ast and verbs: feeris the plural

55 Ae nian eh cl

“aie teens studied by grant bur ic is not obvi Ww oe

eons pave on cided ic Ak DUT word, analogous 10 the -s ending

ae 2d mova ane In & Turkish word evinden ‘from hisee

ino spol = fore “Uhere is the opposite problem, as can be seen

a ae from the related forms:

aE listo

ee evi

ee: hous

Fra bnchofgammarstudiesthestrucureofwords. aden fromthe house ae

be

soglist all the words except the last can

es ore aah oF which has some kind of

independent meaning.

aunbappines

hones

walking

we

sm -happi--nes

Yeshas no intemal grammatical structure. We could

analyse its constituent sounds, jj, /e/, /s/, but none of

these has 2 meaning in isolation. By contrast, horse,

talk, and happy plainly have a meaning, as do the

ee

negative meanings -nes expresses a state or quality; -s

ee ants cen eas ot

duration, The smallest meaningful clements into

which words can be analysed are known as morphemes,

‘and the way morphemes operate in language provides

the subject marcer of morphology.

Itis an easy matter to analyse the above words into

‘morphemes, because a clear sequence of elements is

involved, Even an unlikely word such as antidicertab-

lishmentarianim would also be easy to analyse, for the

same reason. In many languages (the so-called ‘ageluti-

nating’ languages (p. 295)), itis quite normal to have

long sequences of morphemes occur within a word,

and these would be analysed in the same way. For

ample, in Eskimo the word angyaghllangyugrug has

aning he wants to acquire a big boat Speakers

ef English find such words very complex ats sigh

burthingsbecome much clearer when we analyse then,

into their constituent morphemes:

De “boar”

oe

nals expressing augmenttive meaning

mE

mage

an alfix expressing desire

‘anaffix expressing third person. singular,

nih bas relatively Few word structures of

Tolan a oesing

th id Latin, wides

‘G8 atiation. Many Afigy iF

or Bilin, have verbs

‘over 10,000 vatiant forme

this type,

such as

‘morpho.

such as

which can appear in well

ems thar the-fending marks ‘his her / h

oh ending marks from’ — in which case the ost

tion of the two ought to produce evden. But the form

foun in Turkish has an extra m, which does noc seem

to belong anywhere, Its use is aucomatic in this a

(inmuch the same way asan extra rturns up in che pl fe

ral of childin English ~ child-r-en). Effects of this kin

complicate morphological analysis = and add to its

fascination. Explanations can sometimes be found in

other domains: ie might be possible to explain the min

evindenon phonetic grounds (perhaps anticipating the

following nasal sound), and the r in children is cer-

tainly a fossil of an older period of usage (Old Engi

childru). To those with a linguistic bent, there is noth-

ing more intriguing than the scarch for regularities in a

mass of apparently irregular morphological data.

Another complication is that morphemes sometimes

have several phonetic forms, depending on the context

in which chey occur. In English, for example, the past-

fense morpheme (written as -ed), is pronounced in

three different ways, depending on the nature of the

sounds that precede it, Ifthe preceding sound is /t/ or

/MI, the ending is pronounced /id/, as in spotted: if the

Preceding sound is a voiceless consonant (p. 128),

the ending is pronounced /t/, as in walked, and if the

Preceding sound isa voiced consonant or a vowel, the

ending is pronounced /dl, asin rolled. Variant forms of

amorphemeare known as allomorphs,

ally recognized within

morphology ology studies the way in

Hi pos lect’) in order to expres

vent tense. In older grammar

rectus branch of the subject was refereed none

cl boys for example, are ewo forms oF

am “ween them, singular vs

plu isa macer of gtammarand thus the bustoca of

nea otDholgy Devivational. morphology

ver, studies Principles governing the con.

hew words, without Teference tothe spe

Ices oreab0 pos

affix which isinserted

stem the nearest

ism Engton emp

fons suchas

jng-lutely afb

Tagua info

mal morphological PO" ine

Intagal

form urnone we 2

infined within thei,

‘tot toprosse

wach mean

pened

NEW WorDso,.

OLD PSour

There ate four,

cesses of wo

English

forma

placed eto as

workegon

Placed efter the bee

word, €.g. kindness tte

change of form, eg te”

‘carpet (noun) become

aoe

cee

Pe

eg ecto

feet a

tual woritanianes

ae

Saeed

Senda

ee

cniysigniyancens

enone

See

cata amen

onan

ee

gents, flu, telly,

ae

joo rae

ie

oan eae

radio. Neen ae

Sabapebonapnann

imwhich the dferntlete

Se alee

TB ec nesne

ints Soerep oa

Peete

twerttocpe*

orc

‘/ABSO-BLOOMING

LuTELY =

phemescan bea

Intorre’ and vou

Free morphemes ono

separate words 63 7

Bound morphemescav,

‘ccuron theirown. 29 2

“tion. The main last

bound morphemesett

at

prefies and suf

ca

loot

tin rat

ion 8

for exam

Co

col

archeboundary beoseen morphol

asi Meome languages ~ ‘isolating’ lan-

7 2 arma (p. 299) they ae plainly

4 Veh lede or no internal structure, In

etic’ languages, such as Eskimo ~

highly complex forms, equivalent

ike units ate es

ius? noes. The concept of ‘word’ thus ranges

oe ge sounds as Eieliite minal

fu Chelshe definitly did not become

i esern Desert language of Australia

oe ually the easiest unit to identify, in the

Wor ngage In moscwetingsystems, they are che

i have spaces on ether side. (A few systems

ene ders (8. Amari), and some do not

ue Me worsatall 4, Sanskrit) Because aliterate

Tae poss its members fo these units from early

‘Fidhood,weall know whereto put the spaces—apart

inna mambo of problems, many cdo wih

Tamron, Should we write washing machine or

wet be washing-machine? Well informed or

“vl informed? No oneor no-ane?

Tris more difficult to decide what words arc in the

steam of speech, especially in a language that has

oer been written down. But chereare problems, even

in languages like English or French. Cerainly, ic is

posibieto rada sentence aloud slowly, so thac we can

hea’ thespaces between the words; but this is an arti-

geal extese. In natural speech, pauses do noc occur

Semeen each word, a can be seen from any acoustic

words!

Teett of the way people clk. Even in very hesitan

jamal a eal Deen

(p.95) Soif there are mo aude see oy

new what the words at? Linguine hve pone soe:

deal of time trying to devi

Seloimeyingtod vise sasfactory itera none

FIVE TESTS OF WORD IDENT!

mers IFICATION

Say a sentence outloud, and

atk someone to "epeatit,

ever thiscteonisnotper

fectetherinthelgheer,

Sich orméaabsblocming

Verysoniywftnpnuss

Thepowsevilterdtorain eh

bewamwords andnot The aneenionist

within words, For example, peor Nel

the/ thre pis irne ‘heels

(1887-1849) thought of

‘words minimal free

forms'—thats, the smallest

10] market Butthe cite

Fionisnot foo)proot, for

| some people will break up

words containing more than wast apegh than

resisble cemoreth29 meaningfully stand on their

silable, eg. mariket. Gyn Thsdetintion does

tndivisbtity Fandethe majority of

Sey asentence outloud, and wor but eannot cope

ask someone to ‘add extra

Words toit. The extraitems

willbe added between the

wordsand not withinthem,

For example, the pig went to

‘with severalitems which are

‘veated as wordsin writing,

‘but which never stand on

‘their own innatural speech,

suchas Englsh the and of, or

‘market mightbecomethe Frenchje("}and de)

big pig once wentstraight © phonetic boundaries

themarket,butwewould frees :

not have such forms as p- lee

tell from thesoundot

big gormartheket How ord whereit begins or

‘There arene werdspacesin

‘he sthcentury so Geek

Codex Snaiticus Word spaces

‘were creation ofthe Romans,

‘and became widespread only

Inthemtidale ges

Kenicectinons |

Sticectinona

a

renee

sae

=e

ee

cae

Sie siete

pe

tere

penn

eran bala

oe

eee

ee a

cme

eo ae

alee ease

ee

mee

ae

and ee

WORD CLASSES

Since the easly days of grammatical study, words have

been grouped into word clases, traditionally labelled

the pars of speech’. In most grammars, cight such

clases were recognized, illustrated here from English:

‘nouns bay, machine, beauty

‘pronouns she, it, who

adjectives Aappy. shree, bos

vs go, frighten, be

ee 1n, under, with

ictions and, because,

atlerbs ———appily aes

Imerjections gosh, alas, coo

Insome asifications, partic

sits classifications, participles (looking, taken) and.

“elahweepuaapines

ofc a gtoaches dasty words too, bur the use

‘recat ford cas rather than ‘pare of spect

‘lutea at it emphasis. Modern linguists are

Sind gets the nosional defnicons found in adi

some mat = such as a noun being the ‘name of

- The vagueness of these definitions has

often been critici is beauty a ‘thing’? is not the

adjective redalso a ‘name’ of a colour? in place of defi-

nitions based on meaning, there is now a focus on the

seructural features chat signal the way in which groups

‘of words behave ina language. In English, for example,

the definite or indefinite article is one criterion that can

bie used to signal the presence ofa following noun (the

car); similarly, in Romanian, the article (ud) signals the

presence ofa preceding noun (avionud ‘the plane).

"Above all, the modern aim isco establish word classes

thar are coherent: all the words within a class should

behave in che same way. For instance, jump, walk, and

‘cook form a coherent clas, because all the grammatical

“operations that apply to one ofthese words apply the

thers also: they alltakea third personsingular form in

the present tense (he jumps walks/coks), they all hay

apart tense ending in -ed (jumped! walked cooked),

2 so on, Many other words display the same (or

losely similar) behaviour, and this would lead 19

tablish the important class of verbs in English, Sins

ilar reasoning would lead co an analogous cass BN

fee up in other Languages, and timarcly 10

hypothesis that this clas is requi

aillanguages (asa‘substancive univers, S14)

red for the analysis of

CLASSIFYING NOUNS

oad

ed

eo

Le

oe

roe

ree ed

=

eel

oe

coe

earee

ed

cen

sonst

aoe

Kors

ees

sn tanguages. In:

asses forlhuman beings and

generic werds nec and

mata frraly

totng tothe numa st

part tl

erent, But if we do 0°

we have 10 Jer some

‘example, for ues

house is: ‘the only ish noun Sie

she oe {si becomes Joi when the plural ihe

Ae

a deal in common.

ee i ties in a lan

homogeneous 25 the the-

if words that behave

Gaalence

ord classes

Novos

1 ino each one

3 fort: aa

con in pra

which it has:

Because s

asses are chus not

lies. Each class has a core o!

et on 2 grammatical point of view. Buc a¢

if ge ofa cas are dhe mre irregular words, some

oF ich may behave like words from other clases

Some adjectives have a function similar to nouns (eg:

the rich, some nouns behave similarly to adjectives

(eg, nileayisused adjectivally before sation

Frye movement from a central core of stable gram-

matical behaviour to a more irregular periphery has

been called gradience. Adjectives display this phe-

nomenon very clearly, Five main criteria arc usually

tused to identify the central class of English adjectives:

nguage, word

(A) they occurafier forms of fo be, e.g. be sack

(@) they occurafier articles and before nouns, eg. the

bigcar,

(©) they occur after very e.g. very nice

(D) they occurin the comparative or superlative

“ecg eaer ee

they occur before-fyto form adverbs, eg. quickly

‘Wecan now use these criteria to test how much like an

adjective a word is. In che matrix below, candidate

words are listed on the left, and the five criteria are

along thetop. Ifaword meets criterion, itis given a+;

42d, for example, is clearly an adjective (het sad, the sad

ee ser sar sas, ea Ifa word fails the

‘criterion, itis given a— (asin the case of want, which is

Aathng ike an ajc: “hes wan, “Whe on god

“very want, “wanter wanes, “wanth). .

placed in sequence

cual,

set dag 8 one moves away from the

seemssare more adjectvesike eosin tet

ne OF LA’

warner

yas eanr ors

1s ROUND?

peeieres

rotate

rouPecas

eiceseaee

Societe

Batrpedite

ensc

teeters

sett Shin

the grammatical context

Adjective

Mary boua!

Preposition

‘The car went round the

corner.

verb

The yacht willround the

buoy soon,

Adverb

‘Wewalked round to the

shop

Noun

Isyour round. lthave a

whiskey.

TH

ta round table.

ADUSTBIN CLASS?

Several ofthe traditional

parts of speech lacked the

coherence required ot a

well-defined word

las notably, the adverb,

Some have likened this lass

‘toa dustbin, into which

‘remmarians would place

any word whose grammati-

‘alstatuswas unclear,

Certainly the following

words have very little

structurally in common, yet

allhave been labelled

‘adverb’ in traditional

‘grammars:

tomorrow

very

however

pot

quickly when

just the

The, an adver? in sch

contextsas The more

merrier a

i

NGUAGE

NOUN TENSES?

ean ee rN tea

a aia omer mnie eerie

Senne natecin thew cp

se rater shouts oongneee

Bea enecnineh cont ee

tor bevseé on nouns “a

Inkatates! am happy.

jnkegatsopon’ —Iwasonce happy

Inos! my father

Inosp2n! my dead father |

inéimant my canoe

intimanpon’ my former canoe (los, stolen)

(after. F Hockett, 1958, p. 238)

FIVE MOODS |

fear reieten oneal cee

Be ean aie

St ees

eee A eat worn eee

eons are

ioe

pe eon a

ie maine cain

pee een oe

fe A rel espace

‘outhe is not)

(after C.F Hockett, 1958, p. 237.)

DUAL AND TRIAL NUMBER. |

Four numbess are found in the language spoken on

‘Aneltyum Island (Melanesia): singular, dual, tra, plural

‘The forms are shown for 1st and 2nd person: fiv/isa pal

nasal: isa palatal affricate or stop; excl/incl.= |

exclusive/indusive of speaker:

foro)

{Stal we Gre)

ima Wetec)

Cocca |

Lege iens

joka Wwettre inh

Iajamtaj/ we three (excl)

Las

fad tro

Rater ecto

mein

A FOURTH PERSON

A fourth-person contrast is mad

A n contrasts made in the Algonquian

languages, referring to non-identical animate third pero™

inaparticular content. In cree, if we speak of man, atd

then Gecondariy) of another man, the formsare diet

"apex! e/'naspewal. This fourth person form sus

teferred to as the ‘obviative’ ran

(after L. Bloomfield, 1933, p. 257.)

FIFTEEN Cases

Nominative wubjec,

ir o genitive (of), accusative (objec.

inessve in) eative (out o), ative (nt), deste"

tramge tam allatve to) esive (es) parte ea

mrdcomma mre nanso)-abessve (without), struct

pr oh case sso sears fearsome to those Bo

eben the si-term system of Latin, But the es familia

sSies ate Feely quite hike prepositions except that

Fees are atached to the end of the noun as suifbeS

English, 8iNg separate words placed before, asi" |

Ce

(by)

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Teacher Guide Paper 3: Language Analysis: Cambridge International A Level English Language 9093Document29 pagesTeacher Guide Paper 3: Language Analysis: Cambridge International A Level English Language 9093Swati Rai100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Cambridge International AS & A Level Global Perspectives & Research Teacher's Resource CD-ROMDocument5 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level Global Perspectives & Research Teacher's Resource CD-ROMSwati RaiNo ratings yet

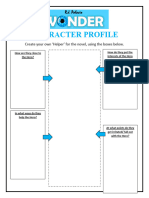

- WonderByRJPalacioQuizzesandAnswerKeys 1Document34 pagesWonderByRJPalacioQuizzesandAnswerKeys 1Swati RaiNo ratings yet

- Character Profile Blank TemplateDocument1 pageCharacter Profile Blank TemplateSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- The Breadwinner Chapter by Chapter ActivitiesDocument32 pagesThe Breadwinner Chapter by Chapter ActivitiesSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- 05 - Crystal - Parts X-XIDocument75 pages05 - Crystal - Parts X-XISwati RaiNo ratings yet

- 06 Crystal AppendicesDocument61 pages06 Crystal AppendicesSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- The Breadwinner - Lesson 3Document2 pagesThe Breadwinner - Lesson 3Swati RaiNo ratings yet

- Morris Jamie - Paper Guided ReadingDocument20 pagesMorris Jamie - Paper Guided ReadingSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- Guided TeachingDocument54 pagesGuided TeachingSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- GSW Afl Transcript 2Document1 pageGSW Afl Transcript 2Swati RaiNo ratings yet

- Streetcar Dramatic TechniquesDocument4 pagesStreetcar Dramatic TechniquesSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- Literature CircleDocument11 pagesLiterature CircleSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- Curious SOWDocument36 pagesCurious SOWSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- Poetry Notes-PracticeDocument35 pagesPoetry Notes-PracticeSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- GSW Afl Transcript 1Document1 pageGSW Afl Transcript 1Swati RaiNo ratings yet

- A Streetcar Named DesireDocument30 pagesA Streetcar Named DesireSwati Rai100% (1)

- Assessment For Learning and EAL LearnersDocument7 pagesAssessment For Learning and EAL LearnersSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- Letter-6 CopiesDocument1 pageLetter-6 CopiesSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- The Main Theme ofDocument6 pagesThe Main Theme ofSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- Pedagogical Support For The EE: The Supervisor-Student RelationshipDocument12 pagesPedagogical Support For The EE: The Supervisor-Student RelationshipSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- Using This Teacher's Resource With The Coursebook: Cambridge International AS & A Level Global Perspectives & ResearchDocument2 pagesUsing This Teacher's Resource With The Coursebook: Cambridge International AS & A Level Global Perspectives & ResearchSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- Linking Skills To Assessment Using A Scheme of Work: Cambridge International AS & A Level Global Perspectives & ResearchDocument4 pagesLinking Skills To Assessment Using A Scheme of Work: Cambridge International AS & A Level Global Perspectives & ResearchSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Pre-U Global Perspectives & Research GuidanceDocument2 pagesCambridge Pre-U Global Perspectives & Research GuidanceSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- 9239 Example Candidate Responses Component 1 (For Examination From 2017)Document30 pages9239 Example Candidate Responses Component 1 (For Examination From 2017)Swati RaiNo ratings yet

- A Study of The Features of Internet English From The Linguistic PerspectiveDocument6 pagesA Study of The Features of Internet English From The Linguistic PerspectiveSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- The Chronicals of NarniaDocument1 pageThe Chronicals of NarniaSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- 9239 Example Candidate Responses Component 4 (For Examination From 2017)Document63 pages9239 Example Candidate Responses Component 4 (For Examination From 2017)Swati Rai0% (1)

- Cambridge International AS and A Level Global Perspectives and ResearchDocument35 pagesCambridge International AS and A Level Global Perspectives and ResearchSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document32 pagesChapter 4Swati RaiNo ratings yet