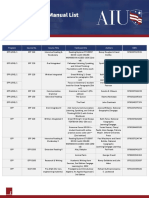

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mimetic Bodies Repetition Replication and Simulation in The Marriage Charter of Empress Theophanu

Mimetic Bodies Repetition Replication and Simulation in The Marriage Charter of Empress Theophanu

Uploaded by

Jose GalatiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mimetic Bodies Repetition Replication and Simulation in The Marriage Charter of Empress Theophanu

Mimetic Bodies Repetition Replication and Simulation in The Marriage Charter of Empress Theophanu

Uploaded by

Jose GalatiCopyright:

Available Formats

Word & Image

A Journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry

ISSN: 0266-6286 (Print) 1943-2178 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/twim20

Mimetic bodies: repetition, replication, and

simulation in the marriage charter of Empress

Theophanu

Eliza Garrison

To cite this article: Eliza Garrison (2017) Mimetic bodies: repetition, replication, and

simulation in the marriage charter of Empress Theophanu, Word & Image, 33:2, 212-232, DOI:

10.1080/02666286.2017.1304796

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02666286.2017.1304796

Published online: 22 Jun 2017.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 78

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=twim20

Download by: [Middlebury College] Date: 01 July 2017, At: 12:35

Mimetic bodies: repetition, replication, and

simulation in the marriage charter of Empress

Theophanu

ELIZA GARRISON

Abstract As an object and as a collection of text and images, the marriage charter of Empress Theophanu (Wolfenbüttel,

Niedersächsisches Staatsarchiv, 6 Urk 11) relies on replication, repetition, and doubling to reinforce the meanings relayed in its text

and to enhance its function as a legal document. This article argues that the charter’s remarkable illusionism functioned as a kind of

visual rhetoric that was entirely in tune with the terms of the golden text that stretches across its surface. Such a powerful coalescence

between text and image was especially well suited to the visualization and propagation of imperial authority, and it girded expectations

of Theophanu’s obedience at the political, social, and physical levels. Framed in terms that name and foreground God-the-craftsman’s

creation of humankind as the originary mimetic act, creation becomes a template for the order of the Ottonian court. The marriage

charter was thus a call to Theophanu and Otto II to internalize both biblical and Platonic models of creation in the interest of

preserving and perpetuating the Saxon imperial line, which was, at the time of the charter’s presentation, but ten years young. In

explicating the various ways in which the marriage charter’s images and text hinge on themes of repetition and replication, this article

will make a case for the political stakes of mimesis.

Keywords Empress Theophanu, Emperor Otto II, Ottonian art, mimesis, marriage charter

On Sunday, April 14, 972, exactly a week after Easter, the

twelve- or thirteen-year-old Theophanu, a niece of the year (maybe even less) prior to the wedding to learn the

Byzantine Emperor John Tzimiskes, was wed to the seven- languages spoken and used in the Ottonian imperial court;

teen-year-old co-emperor Otto II at St Peter’s in Rome. She the meanings of the charter’s language may not have made

was crowned co-empress on this day.1 The ceremony, which much sense to her when she first heard it.5

Pope John XIII performed, came at the end of a protracted As an object and as a collection of text and images,

and contentious series of marriage negotiations between the Theophanu’s marriage charter relies on replication, repetition,

Ottonian and Byzantine empires. At the wedding Theophanu and doubling to reinforce the meanings relayed in its text and

received a luxurious illuminated marriage charter, which was to enhance its function as a legal document. I propose that the

first presented to her as a rotulus that would have been bound charter’s remarkable simulative qualities functioned as a kind

with a cord, sealed with an imperial bull, and possibly con- of visual rhetoric that was entirely in tune with the terms of the

tained in a custom-made case in the manner of official corre- golden text that stretches across its surface.6 Such a powerful

spondence from the Byzantine court (figure 1).2 The document coalescence between text and image was especially well suited

is strikingly illusionistic: with its background painted to simulate to the visualization and propagation of imperial authority, and

purple Byzantine silk, its “embroidered” edges, and its golden it girded expectations of Theophanu’s obedience at the politi-

text, the charter’s various makers made clear the preciousness cal, social, and physical levels. Framed in terms that name and

of its content.3 foreground God’s creation of humankind as the originary

At some point during the marriage ritual, the seal on the mimetic act by a divine craftsman, creation becomes a tem-

rotulus would have been broken and the Latin text of the plate for the order of the Ottonian court. The marriage charter

charter, which was written in the voice of the groom, would was thus a call to Theophanu and Otto II to internalize both

have been read aloud to Theophanu and to the rest of the biblical and, as I will show, Platonic models of creation in the

guests in attendance that day. As decorative as the work may interest of preserving and perpetuating the Saxon imperial line,

appear to us today, the charter marked legally the union which was, at the time of the charter’s presentation, but ten

between Theophanu and Otto II, and among other things it years young.7 In explicating the various ways in which the

documented the territories she was to receive for her faithful marriage charter’s images and text hinge on themes of repeti-

and obedient hand in marriage. After the wedding, as the tion and replication, this article will make a case for the

couple made their way north of the Alps and into Franco- political stakes of mimesis.

Saxon territory, the charter would have been displayed and As I argue, the strident imitation of precious materials in

read aloud at key stops on the imperial itinerary as Theophanu Theophanu’s marriage charter indicates that mimesis as an

was officially presented to the Ottonian nobility.4 Theophanu, ideal helped shape Ottonian artistic culture. The interpretation

whose native language was Greek, had had perhaps about a of this ideal and its attendant meanings have changed over

WORD & IMAGE, VOL. 33, NO. 2, 2017 212

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02666286.2017.1304796

# 2017 Taylor & Francis

time, and yet the art of the early and high Middle Ages, and of a fertile body with a desirable and rare pedigree than an

that of the Ottonians in particular, has gone unnoticed in individual person.15 Like the charter’s silken foundation, it is also

otherwise rich examinations of a concept that has served alter- possible that its text’s bare bones were drafted in advance and

nately as a goal or point of resistance in the history of Western revised over time: the long marriage negotiations outlined below

art.8 Mimesis equated art-making with the imitation of things provided ample time to prepare the charter’s language, and this

in the world, and the charter’s imitative qualities suggest that could conceivably have been adjusted in the weeks leading up to

this ideal could exist alongside the proscriptions of the Second the ceremony. We will never know for certain, but it is plausible

Commandment, which admonished the faithful against making that the charter’s artists and scribe were summoned to Rome

a likeness of any living thing. Far from preventing medieval from their respective workshops north of the Alps to paint its

artists from making images at all, however, these seemingly ground and to pen its golden text.16

conflicting directives fostered an artistic culture that prized Whoever created the body of the marriage charter was draw-

copying, simulation, and the creation of replicas; the very act ing upon the format and deep purple color of the Ottonianum

of creating a copy was sacred.9 This partially explains the (figure 2), which was made for Otto I on the occasion of his

relative abundance of Ottonian artworks that convincingly imperial coronation at St Peter’s in Rome in 962. At this

simulate the appearance of other objects and materials, as ceremony, the newly crowned emperor presented the document

opposed to the faithful reproduction of, for example, individual to John XII; it reaffirmed the privileges the pope had held since

facial features. The story of creation, with which the text of Charlemagne’s reign.17 The relationship between the Ottonianum

Theophanu’s charter commences, involves God’s making of and Theophanu’s marriage charter is clear, and yet the people

Adam in His own image (imago), and medieval intellectuals who designed the charter were also aware of the form and style

likened this model/copy relationship to that between a seal of official correspondence from the Byzantine court, such as the

and its imprint.10 The marriage charter’s simulative illusion- sumptuous letter written on behalf of the Emperor John

ism—its skillful mimicry of the appearance of precious objects Komnenos to Innocent II in 1139 (figure 3).18 Not least, the

and materials—echoed its call to Theophanu to understand form of the marriage charter recalls the format and appearance

her function at court as both a faithful helpmeet and a fecund of southern Italian liturgical scrolls (figure 4).19 As Nino

imperial body. Zchomelidse has shown, the combination of text and image in

such scrolls, along with their unfurling in the celebration of the

From skin into silk: the marriage charter’s Easter mass, was theologically aligned with processes of divine

materials and forms revelation.20

Like so many artworks created for Ottonian patrons, None of the charter’s relationships to its models is entirely

Theophanu’s marriage charter is both visually dazzling and direct, however, meaning that it is formally in conversation

intellectually sophisticated. And yet the object is unique: no with other traditions, but it is nonetheless distinct from all of

other such charter exists. Specialists do not agree on where it them. By any standard, then, the marriage charter is as inno-

was made, but it seems possible that painters at monastic scrip- vative and artful as it is bound to tradition and focused on

toria in Trier or Echternach would have been in a position to replication. Measuring 114.5 centimeters long by 39.5 centi-

paint parchment that could simulate woven silk and other pre- meters wide (just under five feet long by 15.5 inches), it consists

cious materials.11 Ordinarily a legal document such as this char- of three pieces of parchment.21 After these pieces were cut

ter would have been penned in a special notarial script on a down to size, they were glued together and then painted a

piece of blank parchment, but the marriage charter’s scribe, who rich purple. Pigments derived from madder and minium were

learned his trade at Fulda, used golden book miniscule and used to paint the document’s front; the reverse was painted

capitalis rustica after the document’s language had been formu- with a layer of purple pigment derived only from madder.22

lated by Ottonian courtiers and notaries.12 Since the marriage These pigments simulated the effects of murex purple dye,

negotiations between the Ottonian and Byzantine houses whose use in the West was restricted solely for luxury goods

dragged on for roughly five years, during much of which time made specifically for the Byzantine emperor. In this work,

the Ottonians were holding out for a princess born to the simulation became a mark of authority and control: unable to

Byzantine emperor and empress in the porphyry-lined birthing access murex purple for themselves, Ottonian artists set to the

chamber in the imperial palace in Constantinople,13 Anthony task of devising a material alternative.

Cutler and William North have suggested that the body of the After the extensive preparation of the parchment’s purple

“silk” could have been prepared early on in this process; the ground, the document was painted to simulate a swath of

document could therefore have been created just as easily for Byzantine silk, and it would have certainly resembled many of

Princess Anna, who had been the desired bride for Otto II, as it the precious items that Theophanu would have brought with her

was for Theophanu.14 Indeed, this point reminds us that the from Constantinople.23 Beneath the golden script there are seven-

work was conceived with a Byzantine imperial bride in mind: and-a-half pairs of purple roundels. These are framed by alter-

from the perspective of the Ottonian court, this bride was more nating cruciform foliate forms painted a rich indigo; these forms

WORD & IMAGE 213

Figure 1. The marriage charter of Empress Theophanu, 972. Parchment. 144.5 × 39.5 centimeters. Niedersächsisches Staatsarchiv, Wolfenbüttel, 6 Urk 11.

214 ELIZA GARRISON

Figure 2. Ottonianum, February 13, 962. Parchment. 100 × 40 centimeters. Archivio Segreto Vaticano, Rome, A.A., Arm. I–XVIII, 18r.

WORD & IMAGE 215

Figure 3. Correspondence from Emperor John II Komnenos to Pope Innocent II, 1139. Parchment. 399.9 × 35.2 centimeters. Archivio Segreto Vaticano,

Rome, A.A., Arm. I–XVIII, 402r.

216 ELIZA GARRISON

Figure 4. Commemoration of temporal authority, miniature from the Exultet (Easter Proclamation) of Bari, 11th century. Archivio Capitolare, Bari. © DeA

Picture Library/Art Resource, New York.

WORD & IMAGE 217

Figure 5. Detail of figure 1 showing the upper border of the marriage charter of Empress Theophanu.

run through the charter’s center and appear “halved” at the wedding ceremony.28 Southern Italian liturgical scrolls, whose

work’s outer edges, and they thus follow the model of mirroring format certainly informed the appearance of the marriage char-

and splitting that we see in the rest of the images on the body of ter, also typically contain Deesis imagery as well as borders

the charter’s “silken” surface. At the bottom of the document, the decorated with small medallions of holy figures (figure 4).29

charter’s repeating patterns are truncated to enhance its trompe- Alternating pairs of peacocks and leonine quadrupeds separate

l’œil effect and to make it appear as if the charter were cut from a these medallions and are Eucharistic references; their positions

bolt of actual silk. The pair of “split doubles” at the bottom of the as mirror images of each other are formally in concert with their

silk lend the roundels a visual dynamism that is tied to the larger combative “silken” analogues in the main body of the

predictability of the pattern’s repetition and replication. charter.

The roundels contain alternating pairs of dominant male Given the simulative qualities of the forms on the “silk” of

animals and hybrid beasts—griffons and lions—subduing the marriage charter, it is not surprising that scholars of this

acquiescent does and cows. The animal figures in the roundels work have tried to pinpoint their exact origins; however, every

mirror each other: the pairs on the left face left and those on iconographic road seems to lead to multiple other paths.30

the right face right. Each set of animals and the roundels that What has gone hitherto unexamined in the large body of

contain them thus appears as a reflection of its partner. The literature on the marriage charter is the powerful coalescence

battles between dominant male and submissive female crea- of text, image, and illusionism in relation to the expectations it

tures repeat in symmetrical and orderly fashion. Here, it is placed on the young bride.

struggle that girds the message of the golden text, which speaks Cutler and North’s joint study of the marriage charter sees

of a political and marital harmony that is tied to Theophanu’s its text and images as “discrete phases in the production of an

charge to bear children and to keep the marriage bed clean extraordinary document for an extraordinary diplomatic

(see the appendix): event.”31 That is, for these authors the relationship between

the object’s imagery and its text is coincidental. Although the

Likewise the Apostle judges: “Honorable is marriage and present argument diverges from Cutler and North on this point

spotless the marriage bed.” And many other witnesses from —at the very least, the author(s) of the document’s text took a

the holy books affirm that the bond of the marriage pact great deal of inspiration from the images on its ground—they

should happen with God as its author and endure in mutual

were absolutely correct to complicate our understanding of the

and indissoluble love for the procreation of children.

various stages of production that would have been involved in

This duty is presented as a reflection of a heavenly order.24 creating a work like the marriage charter. Hiltrud

Much like the body of the charter, its edges evoke numerous Westermann-Angerhausen, who in several studies has asso-

precious things: embroidered silk, carved ivory, hammered gold, ciated the illuminators of the charter with Trier, has acknowl-

and cloisonné enamel. Anna Muthesius’s work on Byzantine silks edged the various iconographic sources for the silken forms on

has shown that silk clothing was often edged with gold-embroi- the charter’s ground. Further, she has reminded us that the

dered borders that contained small pictures, and the small marriage charter is distinctly and artfully “Ottonian”; its

medallions at the document’s upper edge may have evoked “Byzantine” appearance is a confection. By the time the mar-

this practice (figure 5).25 These medallions contain busts of riage charter was created, Westermann-Angerhausen points

Christ, Mary, and John the Evangelist26—who are all flanked out, artists working in all media in the Ottonian empire—

by four additional medallions of prophets or apostles—and also manuscript illuminators, scribes of sacred texts, goldsmiths—

recall the richness of Byzantine cloisonnés such as those that frame had developed an artistic language that was “supple” and

the cover of the Pericope Book of Henry II (figure 6). Anton von “expansive” and could “simulate a foreign idiom by its own

Euw has noted their remarkable similarity to the portrait round- means.”32 This point bears repeating, for, as noted above, even

els on the sixth-century Byzantine ivory diptych of Justinus the pigments used to create the document’s purple ground—

housed in Berlin.27 The central three medallions of Christ, madder and minium—were intended to simulate murex purple

Mary, and John together form a Deesis, which was a nod to dye from Byzantium.

Theophanu’s Byzantine heritage, and which was perhaps icono- Von Euw’s extensive iconographic analysis of the marriage

graphically keyed to the singing of protective liturgical acclama- charter intrepidly seeks to isolate the clearest iconographic

tions—the Laudes regiae—at the combined coronation and sources for its silken forms; his examination attends to the

218 ELIZA GARRISON

Figure 6. Pericope Book of Henry II, front cover, 1012. Ivory, gold, cloisonné, gems. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, CLM 4452.

WORD & IMAGE 219

document’s imagery in isolation from its text and from the the books’ use.36 In a related study, Anna Bücheler has argued

historical events that occasioned its creation.33 He suggests that the painted textile pages in the twelfth-century Aegidien

that the range of models for this extraordinary object were Gospels functioned for their viewers as metaphorical “veils” of

vast and can be located in forms derived from Assyrian textiles revelation.37 Furthermore, in an investigation of the full-folio

and sculpture, Lombard goldsmithwork, sixth-century consular textile pages in the Golden Gospels of Echtnernach, Bücheler

diptychs from Constantinople, and ivories carved at the court has compellingly proposed that the color purple and purple

school of Charlemagne, to name but a few. Von Euw’s study textiles were metaphorically related both to the human body

concludes that these varied iconographic sources have at their and, more specifically, to Christ’s humanity.38 Made as it was

heart the glorification of the ruler; he suggests only obliquely from skin, parchment was already laden with metaphorical

that, by 972, the charter’s various forms all carried with them allusions to the physical and the material.

the sheen of the “ancient,” the “Carolingian,” and the Sciacca, Bücheler, and others have acknowledged that silk

“Byzantine.”34 I would further propose that the work’s creators was so rare in the West that even its simulation was equated

were also looking closely to Roman sculptural traditions in with the divine. By the tenth century, Constantinople was the

which scenes of dominant beasts (especially lions) tearing at sole center of the silk industry in the Western world; the city’s

the flesh of a captive bull or horse abounded (figure 7). Such a five private guilds answered directly to the city prefect, who

display of taste and sophistication was doubtlessly directed both was charged with maintaining a monopoly on silk, for over-

to Theophanu and her handlers from the Byzantine imperial seeing its export, and for ensuring that silks dyed with murex

court who must also have been in attendance at the wedding; purple were destined only for the emperor’s use.39 Its extreme

the document had to be as sumptuous as it was legally binding, rarity made it that much more desirable. In 968, while on

and what better way to do so than with an air of romanitas. mission to the Byzantine imperial court to negotiate a marriage

Studies of the marriage charter’s silken models consistently for Otto II at a point when Otto I and Empress Adelheid were

note that precious silks from Byzantium and the Near East holding out for the purple-born princess Anna as the chosen

were frequently used in sacred contexts, and they were prized bride, the Italian diplomat and cleric Liudprand of Cremona

as diplomatic gifts. Often, scraps of silk were used to wrap illicitly obtained a cache of murex purple silks to bring back to

relics, for the beauty of the exotic fabric was deemed worthy Italy with him. These were promptly confiscated, for possession

to contain and protect saintly remains. During the Carolingian of such silks was tantamount to treason and punishable by

and Ottonian periods, Byzantine silks were occasionally used as death.40

pastedowns in liturgical books.35 This practice gave rise to the If it is possible to say anything definitive about the silken

integration of full-folio painted “swaths” of simulated fabric forms on the marriage charter of Theophanu, it is that their

into Gospel texts as a way of alluding to the sacred qualities varied iconographic pedigree would have been clear to the

of the Word, as is the case in the Golden Gospels of people who designed them, and no doubt also to the people

Echternach (figure 8). Christine Sciacca has examined the use for whom they were made. At once Roman, Byzantine, Near

of actual textiles as coverings for illuminations that were sewn Eastern, and Carolingian, the forms on the body of the charter

into medieval liturgical and devotional manuscripts, and has conveyed a sense of preciousness and rarity. They also testified

proposed that their integration must have had implications for to a level of cultural sophistication that included a working

Figure 7. Two sides of a Roman sarcophagus with a lion attacking a horse, c.200 CE. Marble. Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican Museums, Rome. Photos:

author; photo montage: Ava Freeman.

220 ELIZA GARRISON

Figure 8. Codex Aureus of Echternach, c.1040. Parchment. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Hs. 15146, ff. 17v–18r.

familiarity with the aesthetic qualities of all manner of artworks reproduction—down to the pairs of dominant and submissive

made in a variety of media, to the extent that Ottonian illumi- animals and beasts on its surface—enhanced its function and it

nators were capable of simulating these media in paint. Indeed, made the terms of the text that much more binding. The

the marriage charter’s dazzling appearance would seem to authors of the charter’s language seem to have used the docu-

suggest that there was no rare and exotic thing of beauty that ment’s visual emphasis on replication and repetition as a point

could escape the voracious eyes of book painters working for of departure in drafting a text that, on the one hand, could

the Ottonian court. In this instance and many others, Ottonian legally mark Theophanu and Otto II’s union and, on the other,

rulers and courtiers supported the artistic virtuosity of painters employed terms that place art and marriage in the service of

in their employ to give visual form to their authority. In the creation. That is, the people who drafted the text and the

absence of murex purple dye, painters employed at the charter’s scribe heeded the work’s visual complexity with lan-

Ottonian court set themselves the task of harnessing the mate- guage that could match it. The virtuosic artfulness of both its

rial qualities of woven and embroidered purple silk. Their “silken” forms and its text amplified its ideological force.

mastery of this simulative process was itself a mark of authority Generally speaking, the structure of the text of Theophanu’s

and control. marriage charter hews closely to the structure of Frankish dotal

charters.41 Walter Deeters proposed that the courtiers respon-

The text sible for much of the legal language in Theophanu’s charter

The marriage charter’s visual references to and simulation of were drawing from language in the dotal charter issued on

other things amplified its textual call to Theophanu and Otto December 12, 937, for Empress Adelheid on the occasion of her

II to understand themselves as two parts of the same whole; the betrothal to her first husband, King Lothar of Italy; the authors

purpose of their union was the birth of heirs to the throne. The of the text of Theophanu’s document may have also had access

marriage charter’s focus on replication, repetition, and to the no-longer-extant copy of the official marriage charter

WORD & IMAGE 221

that was later issued for this union.42 A side-by-side comparison in this document; her role at court was ordered and confirmed

of the texts of these two documents underscores both the by her husband and father-in-law. The male voice and the

verbosity and the theological tenor of Theophanu’s charter male action that gave voice to the text directed Theophanu to

relative to its closest extant model. The authors of the charter’s embody its ideals in her roles as a reflection of her spouse and

language were expected to draft a text that contained all the as the future mother of heirs to the throne. We might even

legal language necessary for such a document, and yet also think of the text and the images in the charter as performing a

underscored the spiritual importance of marriage with termi- metaphorical “clothing” of Theophanu much in the same way

nology borrowed from sources ranging from the Bible to that the text of the Liuthar Gospels was, according to its

Augustine and Tertullian.43 In other words, much of the mar- dedication inscription, intended to “clothe” Otto III’s heart.51

riage charter’s language goes beyond the boilerplate legalese As is common for artworks made in all manner of media in

that would have sufficed to bind Theophanu and Otto II in the Ottonian period, the text of the charter seems to unite the

legal matrimony and to outline the lands that the bride time of the Old and New Testaments with the time of the

received in her dos. This indicates that the courtiers and clerks Ottonian court. The marriage charter’s opening words, its

who wrote the charter’s text were charged with the task of Invocatio, call upon the Trinity, and the next line of the

finding language that could suit the enormous political signifi- Intitulatio invokes “Otto, august emperor by the favor of divine

cance of the union between the Ottonian and Byzantine imper- clemency” (see the appendix). In the three sections that directly

ial houses.44 follow—the Arenga, the Promulgatio and Narratio, and the Dispositio

In a suggestion that has gone unheeded in the subsequent —the text moves from the time of creation, to the time of the

literature on the marriage charter, Deeters argued that none incarnation, to the time of the charter, in which the Ottonian

other than Willigis, the future archbishop of Mainz, and court and Ottonian territory are reflections of divine order.

Gerbert of Aurillac, the future Pope Sylvester II, were responsible What distinguishes the Arenga of Theophanu’s charter from

for drafting much of its text.45 That Willigis was involved in some its closest model is the explicit focus on creation as generative,

aspect of the charter’s text is clear from its final line, which reads: replicative, and artful; this thematic thread is established in the

“I, Willigis the Chancellor, in place of Archchaplain Ruotpert, document’s preamble and it resounds throughout. In the very

have reviewed this” (see the appendix). Indeed, Willigis had first sentence of the Arenga, God is identified both as creator and

become an adviser to the co-emperor Otto II in 969, and by a “very good craftsman” (artifex summe bonus), who, “after the

December 971 had advanced in the ranks of the imperial primordial natures had been set forth in perfect elegance at the

chancellery.46 A mathematician, astronomer, philosopher, theo- beginning of the nascent world,” made Adam “in his own

logian, and teacher, Gerbert of Aurillac was among the most image and likeness” (ad imaginem et similitudinem suam) and gave

learned men of his time; prior to his employment at the him dominion over all creatures. Eve, here referred to as a

Ottonian court, he had been educated in Catalonia, where he “conjugal helpmeet” (adiutorium coniugale), was built (fabricatus)

studied the liberal arts.47 At the time of Theophanu’s marriage to from Adam’s rib to function as his consort and to bear his

Otto II, both Willigis and Gerbert were in Rome, and both were children in order to repopulate the world to take up the spaces

working at the Ottonian court. Gerbert’s likely involvement in left by the fallen angels.52 That is, the purpose of marriage

writing some of the charter’s language also explains its emphasis between a man and a woman is for procreation, as opposed to

on the creator as a craftsman, which further echoes the charter’s the satisfaction of more base physical urges. God’s creation of

visual focus on doubling and repetition. humankind is likened in this section to Christ’s emergence

The marriage charter’s text consists of nine sections of vary- “from the immaculate womb of the virgin [. . .]”; the charter’s

ing length, and, as mentioned above, it is written in the voice of text extends this analogy to Christ’s marriage to the Church.53

Otto II. Knowing that the document would be read aloud, the The preambles of Franco-Saxon marriage charters typically

charter’s scribe, presumably in consultation with its authors, borrow language from Genesis, and Theophanu’s marriage

interspersed small gold dots at key points throughout the text to charter is no exception. And yet the authors of the marriage

indicate to the reader where to pause so as to gird its rhetorical charter integrated theological concepts that were otherwise

impact and to lend rhythm to the spoken word.48 These gold uncommon in such texts.54 In a short consideration of the

dots further indicate that, in the months following the imperial motif of the Church as the bride of Christ in the final sentences

marriage, the text of the charter would have been read on of the marriage charter’s Arenga, Philip Reynolds has recently

repeated occasions as the couple made its way northward and shown that this part of the text had to have been drafted by a

Theophanu was introduced to her subjects.49 If this is the case, theologian with a deep familiarity with both Paul’s discourse on

then the text’s meanings would have been re-inscribed in a marriage in Ephesians 5, and with a gloss on Psalm 18:6 by

series of ritualized speech acts; its performative repetition fol- Augustine that could have been found in Carolingian

lowing the wedding is in keeping with the generative aspects of commentaries.55

creation proclaimed in the text and evoked in its imagery.50 It If the Arenga situates the reader in the time of the Old

is by no means out of the ordinary that Theophanu is voiceless Testament, the Promulgatio and Narratio moves forward into the

222 ELIZA GARRISON

tenth-century present. As short as it is, relative to the long diligently upheld in the times to come, we order that it be

Arenga, it is in this section that the legalities of marriage—the strengthened by our own hand and marked with the imprint

groom’s intention to take his bride in holy matrimony—appear [impressione] of our ring.”

as a response to God’s command in the long opening segment. Indeed, the Subscriptio further connects all the governing

Here the text progresses from an explication of creation and ideas of the charter’s text with the concepts of copying and

God’s command to bear children within the bonds of marriage replication in the work’s silken foundation, and it does so by

to Otto II’s own proclamation of his intent to take Theophanu, exploiting the imagistic potential of the names of Otto the

“the most noble niece of John, emperor of Constantinople,” in father and Otto the son (figure 9). Introduced by the term

matrimony and “in the shared fellowship of imperial rule.” In dominus, the imperial monograms, which function as signa-

the logic of the charter’s text, Theophanu’s proper role as Otto tures as well as visual renderings of the imprints of their

II’s consort is to function as a reflection of him. The completion imperial rings, are stacked one on top of the other, the son

of the marriage in Rome, here referred to as Romulea urbs (a placed below the father.57 The palindromic qualities of the

term derived from Ovid),56 burnished the Ottonians’ imperial name OTTO are used here to representational ends, and

pedigree and close connections to the pope; it propagated the turned inside out and halved to create a curious visual double,

Ottonian court’s romanitas. Perhaps most importantly, this sec- much like the stacked double pairs of animals whose forms are

tion created clear parallels among Otto I, Otto II, and “woven” into the parchment’s purple ground. The repetition

Theophanu and God the Father, Adam, and Eve. of the imperial name and the visual reiteration of its symbolic

With these high stakes in mind, the charter’s Dispositio guaran- force make clear that it is a site of replication, representation,

tees Theophanu territories as part of her dos as if they were parts of and reproduction. While the text of the charter makes con-

creation. These counties and provinces were spread across sistent and repeated reference to creation in its many forms,

Ottonian territory; some of them had formerly been in the posses- the placement, organization, and form of the monograms

sion of Empress Mathilde, Otto I’s mother and Otto II’s paternal underscore the sacred nature of the emperor and co-emperor

grandmother. As the charter states, Theophanu’s receipt of these and their relationship to one another as model and copy,

lands was immediate and perpetual, and they were hers to give, much as Adam was made after the imago of the creator

sell, or exchange in any way she pleased. In receiving control over himself. If creation constitutes the first mimetic act, the repe-

Istria, Pescara, Walacher, Wichelen (with the abbey of Nivelles tition and inversion of the imperial signum makes clear that

and its fourteen thousand manses), Boppard, Thiel, Herford, both emperors in their sameness will beget more of the same,

Tilleda, and Nordhausen, the charter proclaims that this control and Theophanu’s role was to ensure this. In looking to Adam,

extends to everything in those places, “along with the castles, Eve, and the creator as models, Theophanu and Otto II were

houses, male and female servants [. . .] and everything belonging enjoined to do their part to help repopulate their own piece of

wholly to these estates or provinces or abbey.” heaven at court, and in the process heal the deeply wounded

Certainly other parts of the charter are redolent of a culture relationship between their empires. The visual and material

whose structures were believed to reflect biblical precepts. This terms in which this information is relayed unites the legal and

includes a perception of the ruler and the ruling house as political aspects of this marriage with the proposed sacredness

governing with God’s grace, and here we see that it encompasses of the Ottonian imperial line. Such a broad range of concerns

a belief that people could be exchanged as one would exchange was best served by representational and textual strategies that

castles, livestock, or land. It would be presumptuous to assume derived many of their meanings from doubling, replication,

that Theophanu had any chance or inclination to reflect upon and allusions to sealing. Here, Theophanu is metaphorically

her own dual position in this hierarchy, in which she was both a aligned with the material upon which Otto II could impress

ruler and, by virtue of her sex, also an object of exchange, whose his own image or signum.

value was connected to her virginity, her fertility, and her exotic The document’s focus at the beginning and end on the act of

pedigree. Nonetheless, for present-day scholars of this artwork, a creation—first at the time of Adam and Eve and then at the

consideration of these dual positions can help us come to a time of Otto I and Otto II—as both artful and replicative

different understanding of how the marriage charter’s artfulness registers the simulative qualities of the charter’s ground.

and its focus on replication and reproduction functioned to put Further, analysis of the text indicates that its authors were

Theophanu in her place at the very beginning of her life at court. familiar with the discourse on creation contained in

Unlike the first five sections of the charter, which are visually Calcidius’s fourth-century Commentary on and translation of

united in a single text, its final four sections are arranged in Plato’s Timaeus.58 In the late tenth century, Gerbert of

short independent paragraphs. The Sanctio assures that anyone Aurillac and his students were particularly active in copying

who poses a challenge to Theophanu’s gift will be forced to pay Calcidius’s Commentary and in translating the Timaeus.59 Indeed,

her a fine of one thousand pounds in “the finest gold.” The those who read Plato in the tenth century read him through

Corroboratio introduces and explains the Subscriptio beneath it, Calcidius’s commentary and translation; Calcidius’s texts there-

noting: “That this decree be more truly believed and more fore determined the shape of Platonic thought in this period.

WORD & IMAGE 223

Figure 9. Detail of figure 1 showing the Subscriptio of the marriage charter of Empress Theophanu.

Even if Gerbert was not involved in drafting the language of translation of Plato, Anna Somfai has remarked that Calcidius

the charter with Willigis, it is significant that the sections of the presents “Creation [. . .] as the placing of a mathematical order by

marriage charter’s text that stray most pointedly from the dotal a divine artifex on previously existing, chaotic matter.”64 For his

charter of Adelheid—its closest extant model—are those that part, Ittai Weinryb sees this “chaotic matter,” which Calcidius

emphasize both creation and God’s role as an artist and crafts- called silva, as “pure potentiality.”65 Artists, in the manner of the

man. For example, the first sentence of Adelheid’s charter creator, could harness and work this potentiality. In the text of the

includes a reference to God as the “creator omnium’, while charter, Theophanu and Otto II were reminded again and again

the document drafted for Theophanu begins with the phrase of their own physical potentiality, whose positive fulfillment

“Creator et institutor omnium ab aeterno Deus quecumque depended on a harmonious and fecund union. Like the pairs of

sunt rerum primordialibus initio nascentis mundi in perfecta tussling creatures whose chaotic yet choreographed movements

elegantis editis naturis [. . .]” (see the appendix).60 “God, eter- repeat down the expanse of the charter’s ground, this document

nal creator and founder of all things whatsoever they are,” who gave Theophanu and Otto II an understanding of the urgency

is described at the end of that same sentence as “a very good and inevitability of this responsibility, upon which the continuity

craftsman” (artifex summe), brought all the “primordial natures” of the Saxon line depended. Although only a speculation, it is

together in harmony and beauty. Much as a craftsman might tempting to see the visual and textual tension between order and

mold or shape material, the god of Theophanu’s charter is able chaos in relation to the warfare and political intrigue that marked

to harness chaotic primordial elements and to bring them into the five-year marriage negotiations between the Ottonian and

a perfect order. Byzantine imperial houses. In short, the images, text, and materi-

Such a characterization of the creator would seem to derive in als of the marriage charter are imbued with a powerful mimetic

great measure from Calcidius’s description of Plato’s creator in charge; the object’s extraordinary sophistication is a testimony to

the Timaeus.61 In chapter 23 of his Commentary, which in part the high political stakes of Theophanu and Otto II’s union.

responds to and expands upon section 32c of the Timaeus,

Calcidius states that “everything that exists is a work of god, The marriage negotiations

nature, or man acting as an artisan [artificis] in imitation of In the 960s, both the Roman Emperor Otto I and his Byzantine

nature.”62 Even a casual reading of Calcidius’s translation and counterpart, Emperor Nikephoros Phokas, had set their sights on

commentary makes clear that both Plato and Calcidius were establishing territorial control in southern Italy.66 Phokas was

interested in explaining in various ways the role of a craftsman- married to Empress Anastasio Theophanu, the wife of his pre-

god or demiurge (most commonly an opifex but occasionally also decessor; the empress played an influential role at the Byzantine

an artifex) in fashioning things that resemble and reflect divine court.67 In March 967, while he was in residence in Ravenna,

models.63 In her examination of Calcidius’s commentary and Otto I received emissaries from Phokas’s court. The Byzantine

224 ELIZA GARRISON

diplomats expressed Phokas’s concern over the incursion of Otto over Rome and Ravenna in favor of Apulia and Calabria. In

I’s forces into Benevento and Capua and those towns’ surround- spite of the new political openness of his court, however,

ing territories; both towns and their dependent lands were situ- Tzimiskes, like his predecessor, refused to marry off Anna to

ated on the edge of the Ottonian empire and abutted territory Otto II. As much as the relations between the Ottonians and the

controlled by the Byzantines. By the close of these talks, an Byzantines had warmed by this point, and in spite of the imperial

arranged marriage between the two houses appeared to be the titles of Otto the father and Otto the son, marrying off a purple-

most reasonable way to a military truce. Otto I entrusted a born daughter to a European court could pose a potential threat

Venetian named Dominikus to travel to Constantinople and to the line of Byzantine succession in the future.75

appeal to Phokas for a marriage between Phokas’s stepdaughter, Instead of sending Anna, Tzimiskes selected the young

Anna, and Otto II.68 Perhaps as a way of assuring the Byzantines Theophanu, a niece of his who had probably grown up in the

that any purple-born daughter of theirs would marry within her palace walls but who was not purple-born.76 At some point in

station, Otto II was elevated to co-emperorship with his father on the early months of 972, Theophanu, along with her own retinue

December 25, 967, at St. Peter’s in Rome. and that of Archbishop Gero, boarded ship and sailed for the

Already by January 968, or shortly thereafter, the marriage Italian peninsula.77 They disembarked at an Italian port under

negotiations between the Ottonians and the Byzantines had dete- Byzantine control—perhaps Bari or Siponto—and proceeded

riorated, prompting Otto II to send forces to invade the contested thence to Benevento, which was then under Ottonian control,

territory of Apulia, which would have extended Ottonian control where Bishop Dietrich of Metz formally received them. From

over much of the trade on the eastern Italian coast and in the Benevento they made their way to Rome, where Otto I, Otto II,

Adriatic. By March 968, Otto I’s army had advanced as far south and the rest of the imperial court met them.78

as Bari before his soldiers were forced to retreat.69 Thietmar of Merseburg noted in his Chronicon that “not a few”

This Ottonian defeat at Bari immediately prompted a renewed nobles at Otto I’s court felt that Theophanu’s arrival was an

set of marriage negotiations; both sides viewed such an exchange affront to the Saxon emperor’s honor, and they advised Otto I

as the best way to achieve a measure of peace between them. This to send the girl back to Constantinople.79 Yet there were many

time, Otto I engaged the polyglot diplomat and cleric Liudprand reasons not to return Theophanu to the Byzantine court.80 For

of Cremona to renew efforts to arrange a marriage between example, it is possible that the subject of a Byzantine princess who

Princess Anna and Otto II. By June 4, 968, Liudprand arrived was not born in the purple had been part of the last negotiations.

at the court of Phokas in Constantinople, and the two men met At the very least, Otto I was certainly aware that returning

face to face in the Crown Palace three days later.70 Liudprand Theophanu to her family would only protract and intensify the

related to Phokas that, in exchange for Anna’s hand in marriage, long-standing political antagonism between the two houses.

Otto I promised to relinquish control over his territories on the Having faced serious challenges from his younger brother,

southern Italian peninsula. Phokas rejected this deal out of hand: Henry, upon his accession of the throne in 936, it is plausible

in such an exchange, he would settle for nothing less than Rome, that Otto I and Empress Adelheid were concerned about their son

Ravenna, and all their dependent lands. Given the vastly different fathering a healthy and legitimate male heir.81 With verbal and

expectations on both sides, the negotiations fell apart.71 visual imagery that invokes procreation and doubling,

Just over a year later, late at night on December 10 or early Theophanu’s marriage charter would seem to be the one primary

in the morning of December 11, 969, Phokas was murdered in source that might corroborate this proposition. At the very least,

his bedchamber by contract killers hired by none other than his this magnificent document provided Theophanu with the purple

wife, the Empress Anastasio Theophanu, and her lover, a pedigree that Otto I, Adelheid, and much of the rest of the

general named John Tzimiskes who immediately succeeded to Ottonian court had so desperately desired.

the Byzantine throne.72 This coup-d’état and the concomitant

political changes it brought about at the Byzantine court occa- Conclusions

sioned the release of the Italian Prince Pandulf of Capua from On the charter, creation generates and demands more of the

prison in Constantinople in the spring of 970. Pandulf was same; it is mimetic, and therefore expects an equal, and equally

returned to Italy with a message from the Byzantine court to harmonious, response. The document’s visual and linguistic

Otto I indicating that the new Emperor Tzimiskes was willing emphasis on sameness and doubling imbued it with authority

to renew peace and marriage negotiations. Pandulf’s arrival and a binding power. At this point of closure it is important to

was particularly timely, since Otto I’s forces had advanced once acknowledge that Theophanu adapted quickly to the expecta-

more into Apulia.73 tions enumerated on the charter’s silken surface: she bore five

In 971, with renewed hope, Otto I sent Archbishop Gero of children (four of whom survived infancy) in quick succession,

Cologne on a diplomatic mission to Constantinople to begin including a male heir to the throne; she took an active hand in

marriage negotiations yet again; it is possible that Liudprand of the governance of the empire during Otto II’s lifetime and after

Cremona accompanied his German colleague.74 Unlike his pre- his death in 983, and she was, along with the Empress Dowager

decessor, the Emperor Tzimiskes was willing to forgo control Adelheid, a formidable imperial regent for her son, Otto III,

WORD & IMAGE 225

until her own death in 991 in Nimwegen when she was about Wolfenbüttel (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1972), 29, 38; and Die

thirty-one years old.82 Upon her request, she was buried in the Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin Theophanu. Sonderveröffentlichung der

Niedersächsischen Archivverwaltung anläßlich des X. internationalen

Westwerk of St Pantaleon in Cologne, in proximity to the relics Archivkongresses in Bonn, ed. and trans. Dieter Matthes (Braunschweig:

of that same saint that Archbishop Gero of Cologne had Niedersächsisches Staatsarchiv, 1984), 24, 26. See also Franz Dölger, Byzanz

procured in Constantinople while he was arranging her und die europäische Staatenwelt. Ausgewählte Vorträge und Aufsätze (Darmstadt:

marriage.83 These same relics, then, had accompanied Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1964), 9–33.

Theophanu on her entry into life at the Ottonian court, and 3 – The marriage charter is now kept in the Niedersächsisches Staatsarchiv,

Wolfenbüttel, 6 Urk 11. In 1823 it was removed from the convent archives

they stood sentry for her after her death. No matter how at Gandersheim to be deposited in the Braunschweigisches

powerful a figure Theophanu eventually became in her short Landeshauptarchiv. It is possible that the document arrived in

life, at the time of its creation, the marriage charter that she Gandersheim at some point during Theophanu’s lifetime or during that

received on her wedding day was one result of a political of her daughter, Sophia, who was abbess at Gandersheim from 1001 to

exchange in which her future life and property were laid out 1039; see Anthony Cutler and William North, “Word Over Image: On the

Making, Uses, and Destiny of the Marriage Charter of Otto II and

for her like so many bones on precious silk. Theophanu,” in Interactions: Artistic Interchange between the Eastern and Western

Worlds in the Medieval Period, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 2007), 167–87, at 167, nn. 1, 2. In 1980, the

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Niedersächsisches Staatsarchiv published a facsimile of the marriage char-

ter along with a short commentary volume: Die Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin

This article benefited enormously from insight and feedback Theophanu. 972 April 14. Faksimile-Ausgabe nach dem Original im Niedersächsischen

from Brigitte Buettner, Mariah Proctor-Tiffany, Nina Rowe, Staatsarchiv in Wolfenbüttel (6 Urk 11), ed. and trans. Dieter Matthes (Stuttgart:

Stephen Wagner, and Ittai Weinryb. Changes suggested by an Müller & Schindler, 1980).

anonymous referee for this journal strengthened the terms of the 4 – Precisely how the document would have been displayed and read in

argument. William North provided extremely helpful substan- public remains an open question. Was the charter’s golden text and

“silken” surface displayed to the audience while a more ordinary transcrip-

tive comments on an earlier draft, and he graciously allowed the tion and/or translation was read aloud? Was the text read in its entirety or

publication of his revised translation of the Charter's text with merely brief passages? Anthony Cutler and William North have offered

this article. John Magee and Anna Somfai deserve recognition some educated speculation; Cutler and North, “Word Over Image,”

for their willingness to field questions as the author grappled 170–71, 182–83. See also note 50 below.

with Calcidius. Philip Reynolds was most gracious in engaging 5 – Judith Herrin, “Theophano: The Education of a Byzantine Princess,”

in The Empress Theophano, ed. Adelbert Davids (Cambridge: Cambridge

queries about the theological nuances of the Charter’s text. University Press, 1995), 64–85, esp. 82.

Kristen Collins, Sherry Lindquist, Elizabeth L’Estrange, 6 – In recent decades, scholars of contemporary art have turned their

Melanie Sympson, Trevor Verrot, and Beth Williamson all attention to the practice of “re-mediation,” in which artworks made in a

provided space to present this work publicly in its various stages, particular medium evoke other, often older, media; e.g. Jay David Bolter

and for this the author is deeply grateful. Jürgen Diehl and the and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge, MA:

MIT Press, 1998); and Mediation, Remediation, and the Dynamics of Cultural

archivists at the Niedersächsisches Staatsarchiv in Wolfenbüttel Memory, ed. Astrid Erll and Ann Rigney (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2009).

were most generous in granting access to the Marriage Charter. 7 – The work of Madeline Caviness, Brigitte Buettner, Cecily Hilsdale, and

The author dedicates this article to the memory of the historian Mariah Proctor-Tiffany has attended to the ways in which objects, in

David Warner. Buettner’s words, “played a role in the production and reproduction of

social relations within court society”, 598; Madeline Caviness, “Patron or

Matron? A Capetian Bride and a Vade Mecum for Her Marriage Bed,”

Speculum 68, no. 2 (1993): 333–62; Brigitte Buettner, “Past Presents: New

NOTES Year’s Gifts at Valois Courts, ca. 1400,” Art Bulletin 83, no. 4 (2001):

1 – Theophanu was born in either 959 or 960 and died in 991. Otto II was 598–625; Cecily Hilsdale, “Constructing a Byzantine ‘Augusta’: A Greek

born in 955 and died in 983. While the details of what the marriage liturgy Book for a French Bride,” Art Bulletin 87, no. 3 (2005): 458–83; eadem,

would have consisted are unclear, the empress’s coronation ceremony Byzantine Art and Diplomacy in an Age of Decline (New York: Cambridge

would have resembled the Ordo transcribed in Die Ordines für die Weihe und University Press, 2014); Mariah Proctor-Tiffany, “Transported as a Rare

Krönung des Kaisers und der Kaiserin, ed. Reinhard Elze (Hannover: Hahnsche Object of Distinction: The Gift-Giving of Clémence of Hungary, Queen of

Buchhandlung, 1960), 6–9. See also Cyrille Vogel, “Le Pontifical romano- France,” Journal of Medieval History (2015): 1–21.

germanique du dixième siècle. Nature, date et importance du document,” 8 – Erich Auerbach, Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature,

Cahiers de civilisation médiévale 6, no. 21 (1963): 27–48; and Cyrille Vogel and trans. Willard R. Trask (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953, 2003),

Reinhard Elze, Le Pontifical romano-germanique du dixième siècle (Rome: set up many of the terms of the scholarly discussion of the concept. To get a

Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1966). sense of the manner in which art historians have engaged with it, and for

2 – If such a container existed, then the “fabric” of the charter would have references to the rest of the literature, see Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence

been conceptually akin to the kinds of precious Byzantine and Near (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997); Gunter Gebauer and

Eastern fabrics used to wrap relics; the sacred object here would be the Christoph Wulf, Spiel–Ritual–Geste: Mimetisches Handeln in der sozialen Welt

text itself, which had a dual function as a kind of authentic. Given the (Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1998); The Holy Face and the Paradox of Representation,

preciousness of the document’s content, this container could have been ed. Herbert Kessler and Gerhard Wolf (Bologna: Nuova Alfa and Johns

similarly sumptuous in appearance. For the reference to Byzantine corre- Hopkins University Press, 1998); Stephen Halliwell, The Aesthetics of Mimesis

spondence, see Dieter Matthes and W. Deeters, Die Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002); Vibeke Olsen, “The

Theophanu. 972 April 14, Rom. Eine Ausstellung des Niedersächsischen Staatsarchivs in Significance of Sameness: An Overview of Standardization and Imitation

226 ELIZA GARRISON

in Medieval Art,” Visual Resources 20 (2004): 161–78; Original–Kopie–Zitat. 16 – Specialists seem relatively certain that the artist who painted the

Kunstwerke des Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit, ed. Wolfgang Augustyn and charter’s ground was none other than the “Master of the Registrum

Ulrich Söding (Passau: Dietrich Klinger, 2010); Similitudo, ed. Martin Gaier, Gregorii”; see notes 11 and 12 above.

Jeanette Kohl, and Alberto Saviello (Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 2012); and 17 – For a brief examination of this connection along with references to the

Göran Sörbom, Mimesis and Art: Studies in the Origin and Early Development of an earlier literature, see Wolfgang Georgi, “Ottonianum und

Aesthetic Vocabulary (Stockholm: Svenska, 1966). Heiratsurkunde,” in Schreiner and von Euw, Kaiserin Theophanu: Begegnung

9 – Richard Krautheimer, “Introduction to an ‘Iconography of Mediaeval des Ostens und Westens, II: 13–160, at 135–143.

Architecture,’” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 5 (1942): 1–33. 18 – Ibid., 143–46.

10 – Brigitte Miriam Bedos-Rezak, “Replica: Images of Identity and the 19 – For the most recent work on these objects, see Nino Zchomelidse, Art,

Identity of Images in Prescholastic France,” in The Mind’s Eye: Art and Ritual, and Civic Identity in Medieval Southern Italy (University Park: Penn State

Theological Argument in the Middle Ages, ed. Jeffrey Hamburger and Anne- University Press, 2014), 34–71.

Marie Bouché (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), 46–64. See 20 – Ibid., 55–56. Zchomelidse has tied the emergence of these scrolls (also

also my analysis of this concept in relation to Otto III’s donations to the called Exultet rolls) to both the patronage of Archbishop Landulf of

Palace Chapel at Aachen: Eliza Garrison, Ottonian Imperial Art and Portraiture: Benevento and the Beneventan Easter Rite. It seems significant that the

The Artistic Patronage of Otto III and Henry II (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), 39–86, form and elements of the imagery of both southern Italian liturgical scrolls

esp. 50–60, and eadem, “Otto III at Aachen,” Peregrinations 3, no. 1 (2010): and the marriage charter are so similar, particularly in the light of the fact

83–137. that control over Benevento, Capua, and their dependent territories was

11 – Hartmut Hoffmann devoted an entire section of his Buchkunst und one of the many terms of discussion in the negotiations between the

Königtum to the marriage charter. He identified the charter’s illuminations Ottonians and the Byzantines.

as the work of the “Master of the Registrum Gregorii,” who was active in 21 – Although there is no way to know for certain how tall Theophanu was

Trier; Hartmut Hoffmann, Buchkunst und Königtum im ottonischen und at the time of her marriage, it seems possible she was not much taller than

frühsalischen Reich, 2 vols (Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1986), Vol. I, 103–26. the marriage charter when she first received it.

For a technical examination of the charter’s golden script, see Vera 22 – For pigment analysis, see Hans Goetting and Hermann Kühn, “Die

Trost, “Chrysographie und Argyrographie in Handschriften und sogenannte Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin Theophanu (DO II.21), ihre

Urkunden,” in Kaiserin Theophanu: Begegnung des Ostens und Westens um die Untersuchung und Konservierung,” Archivalische Zeitschrift 64 (1968): 11–24.

Wende des ersten Jahrtausends, ed. Peter Schreiner and Anton von Euw, 2 23 – Whatever the treasure that Theophanu brought with her from

vols (Cologne: Schnütgen Museum, 1991), Vol. II, 335–43. Constantinople may have consisted of is a mystery. Indeed, very few art-

12 – Hoffmann, Buchkunst und Königtum, I: 10–11; Hans Schulze, Die works that can be directly associated with her patronage survive. Hiltrud

Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin Theophanu. Die Griechische Kaiserin und das römisch- Westermann-Angerhausen has addressed the question of whether the

deutsche Reich, 972–991 (Hannover: Hahn, 2007), 27–28. numerous pieces of Byzantine and eastern spolia in Ottonian treasury

13 – Such imperial offspring were described as “purple born” or “born in works somehow derived from the precious objects that Theophanu must

the purple” (Greek Πορφυρογέννητος and latinized in the West to porphyr- have brought from Constantinople, suggesting that this question is a bit of a

ogenitus). These terms could only refer to children of the Byzantine emperor red herring in art-historical studies of Ottonian artworks. To get a sense of

who were born in this special birthing chamber in the imperial palace in the discussion of Theophanu’s elusive treasure, see Hiltrud Westermann-

Constantinople, and the title could only apply to imperial children born to Angerhausen, “Did Theophano Leave Her Mark on the Ottonian

the emperor after he had become emperor. For more on this, see Adelbert Sumptuary Arts?,” in Davids, Empress Theophano, 244–64; eadem, “Spuren

Davids, “Marriage Negotiations between Byzantium and the West and the der Theophanu in der ottonischen Schatzkunst?,” in Schreiner and von

Name of Theophano in Byzantium (Eighth to Tenth Centuries),” in Euw, Kaiserin Theophanu: Begegnung des Ostens und Westens, II: 193–218; Hans

Davids, Empress Theophano, 99–120, at 99–101. Wentzel, “Das byzantinische Erbe der ottonischen Kaiser. Hypothesen

14 – Cutler and North were the first to propose such a scenario; Cutler and über den Brautschatz der Theophanu,” Aachener Kunstblätter 40 (1970):

North, “Word Over Image,” at 180. 15–39; idem, “Das byzantinische Erbe der ottonischen Kaiser.

15 – The literature on medieval marriage and medieval brides is vast, and Hypothesen über den Brautschatz der Theophanu,” Aachener Kunstblätter

thus I cite the most critical points of departure, each of which contains 43 (1972): 11–96; idem, “Alte und altertümliche Kunstwerke der Kaiserin

references to a host of other sources. On medieval brides and marriage, see Theophanu,” Pantheon 30 (1972): 3–18; and idem, “Byzantinische

Georges Duby, The Knight, the Lady, and the Priest: The Making of Modern Kleinkunstwerke aus dem Umkreis der Kaiserin Theophanu,” Aachener

Marriage in Medieval France, trans. Barbara Bray (New York: Pantheon, Kunstblätter 44 (1973): 43–86.

1983); idem, Love and Marriage in the Middle Ages, trans. Jane Dunnett 24 – It is tempting to see these paired animals as references both to tensions

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996); Judith Herrin, between the east and the west and the eventual consummation of

“Theophano: The Education of a Byzantine Princess,” in Davids, Empress Theophanu and Otto II’s marriage. Mary Carruthers has an excellent,

Theophano, 64–85; Jo Ann McNamara, “Women and Power through the yet short, analysis on a passage in Deuteronomy 21 describing a captor and

Family Revisited,” in Gendering the Master Narrative: Women and Power in the a captive that would seem also to apply to the concepts evoked in the

Middle Ages, ed. Mary C. Erler and Maryanne Kowaleski (Ithaca: Cornell paired images on the marriage charter; Mary Carruthers, The Craft of

University Press, 2003), 17–30, esp. 25–26; Carolyn L. Connor, Women of Thought: Meditation, Rhetoric, and the Making of Images, 400–1200 (Cambridge:

Byzantium (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004), 207–37; Cambridge University Press, 1998), 126–27. See also Cutler and North,

and Sara McDougall, “The Making of Marriage in Medieval France,” “Word Over Image,” esp. 176–79.

Journal of Family History 38, no. 2 (2013): 103–21. On marriage as a sacra- 25 – Anna Muthesius, Studies in Byzantine, Islamic, and Near Eastern Silk

ment, see Philip L. Reynolds, How Marriage Became One of the Sacraments: The Weaving (London: Pindar, 2008), 17–21. See the following studies for more

Sacramental Theology of Marriage from its Medieval Origins to the Council of Trent on the significance of Byzantine silks in the Ottonian empire: Anna

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016); To Have and to Hold: Muthesius, “The Role of Byzantine Silks in the Ottonian Empire,” in

Marrying and its Documentation in Western Christendom, 400–1600, ed. Philip L. Byzanz und das Abendland im 10. und 11. Jahrhundert, ed. Evangelos

Reynolds and John Witte, Jr. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Konstantinou (Cologne: Böhlau, 1997), 301–17; eadem, Byzantine Silk

2007); and Philip L. Reynolds, Marriage in the Western Church: The Weaving, AD 400 to AD 1200 (Vienna: Fassbaender, 1997), esp. 119–39;

Christianization of Marriage During the Patristic and Early Medieval Periods eadem, Studies in Silk in Byzantium (London: Pindar, 2004); and Leonie von

(Leiden: Brill, 1994). Wilckens, “Byzantinische Seidenweberei in der Zeit vom späten 8. bis zum

WORD & IMAGE 227

12. Jahrhundert,” in Kunst im Zeitalter der Kaiserin Theophanu, ed. Anton von book covers; David Ganz, “Das Kleid der Bücher,” in Woodfin and

Euw and Peter Schreiner (Cologne: Locher, 1993), 79–93. Warren Kapustka, Clothing the Sacred, 121–46.

Woodfin’s work has dealt with the political meanings of Byzantine silks in 39 – Silk production first arrived in the West in the second half of the

the west; Warren Woodfin, “Presents Given and Presence Subverted: The twelfth century during the reign of Roger II of Sicily, who established silk

Cunegunda Chormantel in Bamberg and the Ideology of Byzantine Textiles,” workshops in Palermo staffed by craftspeople from Byzantium and the

Gesta 47, no. 1 (2008): 33–50; and Clothing the Sacred: Medieval Textiles as Fabric, Islamic world; Anna Muthesius, “The Role of Byzantine Silks in the

Form, and Metaphor, ed. Warren Woodfin and Mateusz Kapustka (Berlin: Ottonian Empire,” in Konstantinou, Byzanz und das Abendland, 302–03.

Imorde, 2014). See also Anna Muthesius, “The Role of Byzantine Silks in the Ottonian

26 – Dieter Matthes identified this figure as John the Evangelist in his Empire,” in Anna Muthesius, Studies in Byzantine and Islamic Silk Weaving

commentary volume to the facsimile of the marriage charter, but he did (London: Pindar, 1995), 201–15, at 202.

not provide any explanation for this identification. Both this figure and that 40 – Anna Muthesius, “Silken Diplomacy,” in eadem, Studies in Byzantine and

of Mary are placed in front of blue backgrounds, forming bookends to Islamic Silk Weaving, 165–72, at 169, nn. 22, 23. Muthesius notes that purple

Christ’s figure in the manner of a traditional Deesis. John’s figure holds a silk was so highly sought after that Byzantine emperors supported the

codex in his left hand, which would be an appropriate attribute for the production of silks colored with a lower-quality purple dye for export to

Evangelist. This is, therefore, among the earliest—if not, in fact, the earliest the West; Liudprand of Cremona, Embassy, ch. 54, in The Complete Works of

—extant representations of a Deesis with John the Evangelist instead of John Liudprand of Cremona, ed. and trans. Paolo Squatriti (Washington, DC:

the Baptist; Dieter Matthes, Die Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin Theophanu. Catholic University of America Press, 2007), 271–72. See also Peter

Faksimile-Ausgabe, 9. Jeffrey Hamburger has argued for the Evangelist’s Schreiner, “Diplomatische Geschenke zwischen Byzanz und dem Westen

role as an imago Dei. Given the charter’s focus on processes of copying, ca. 800–1200: Eine Analyse der Texte mit Quellenanhang,” Dumbarton Oaks

repetition, and mimesis, the inclusion of the Evangelist in this small vision Papers, 58 (2004): 251–82, at 263, n. 87.

of the Deesis is particularly fitting; Jeffrey Hamburger, Saint John the Divine: 41 – Philip Reynolds has outlined in his work the structures of such

The Deified Evangelist in Medieval Art and Theology (Berkeley: University of documents; Reynolds, How Marriage Became One of the Sacraments, 18–19,

California Press, 2002). passim; and idem, “Marrying and its Documentation in Pre-Modern

27 – Anton von Euw, “Ikonologie der Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin Europe: Consent, Celebration, and Property,” in Reynolds and Witte, To

Theophanu,” in Schreiner and von Euw, Kaiserin Theophanu: Begegnung des Have and To Hold, 1–42.

Ostens und Westens, II: 175–91, at 186–90, fig. 17. 42 – Walter Deeters, “Zur Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin Theophanu,” in

28 – On the Laudes regiae, see, Ernst Kantorowicz, “Ivories and Litanies,” Neue Forschungen zur Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin Theophanu. 972 April 14, Rom

Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 5 (1942): 56–81; idem, Laudes Regiae: (MGH DO II 21), Sonderdruck aus Braunschweigisches Jahrbuch, 54 (1973):

A Study in Liturgical Acclamations and Mediaeval Ruler Worship (Berkeley: 5–19, at 6–9. Adelheid and Lothar were not married until 942. Lothar

University of California Press, 1958), esp. 65–111; Schulze, Heiratsurkunde der died in November 950 and Adelheid married Otto I in the fall of the

Kaiserin Theophanu, 27. Schulze notes here that Deesis iconography had a following year. The charter that Adelheid received at her second marriage

protective function both for the recipient of the work and also for its creators. has not survived, but it seems likely that it could have served as a crucial

29 – Zchomelidse, Art, Ritual, and Civic Identity, 34–71. model for the creators of Theophanu’s charter; Schulze, Heiratsurkunde der

30 – The literature on this object is extensive, and I cite here the most Kaiserin Theophanu, 34. Deeters, “Zur Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin

substantive analyses, each of which contains references to the rest of the Theophanu,” 7–9, has reproduced the text of Adelheid’s dotal charter; it

literature: Cutler and North, “Word Over Image”; Schulze, Heiratsurkunde is also available in Historiae Patriae Monumenta, Tomus XIII: Codex Diplomaticus

der Kaiserin Theophanu; von Euw, “Ikonologie der Heiratsurkunde der Langobardiae (Turin, 1873), no. 553, pp. 568–69.

Kaiserin Theophanu,”; Matthes and Deeters, Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin 43 – Deeters, “Zur Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin Theophanu,” 10–15.

Theophanu. 44 – Ibid., 18–19. Deeters noted the care that the text’s authors took in

31 – Cutler and North, “Word Over Image,” 180. drafting the text of the marriage charter, and suggested briefly a self-

32 – Westermann-Angerhausen, “Did Theophano Leave Her Mark,” 252, conscious connection between word and image.

and generally 246–52. See also note 23 above. 45 – Ibid.

33 – Von Euw, “Ikonologie der Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin Theophanu.” 46 – Ibid., 19.

34 – Ibid., 191. 47 – Deeters suggests that this may explain the mozarabic origins of the

35 – The Lindau Gospels in the Morgan Library, MS M. 1, contain one liturgical language in the Arenga’s second sentence; ibid., 11.

such Byzantine silk pastedown, which was made between the eighth and 48 – Ibid., 5–6, nn. 3, 4.

tenth centuries. 49 – Ibid., 5–6.

36 – Christine Sciacca, “Raising the Curtain on the Use of Textiles in 50 – Schulze also postulates that Greek and German translations of the

Manuscripts,” in Weaving, Veiling, and Dressing: Textiles and their Metaphors in the document may have existed; these texts would have likewise been read

Late Middle Ages, ed. Kathryn Rudy and Barbara Baert (Turnhout: Brepols, aloud in public fora. As he points out, Theophanu’s retinue would have

2007), 161–90. spoken primarily Greek, and the nobles at the Ottonian court spoke

37 – Anna Bücheler, “Veil and Shroud: Eastern References and Allegoric German; Schulze, Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin Theophanu, 39. This phenom-

Functions in the Textile Imagery of a Twelfth-Century Gospel book from enon is also visible in the dedication images of manuscripts made for both

Braunschweig,” Medieval History Journal 15, no. 2 (2012): 269–97. For clear Otto III and Henry II. Compare, for example, the dedication series in the

explanations of the use of silk in Ottonian and Salian manuscripts, see Liuthar Gospels and the Regensburg Sacramentary, both of which include

Stephen Wagner, “Establishing a Connection to Illuminated Manuscripts coronations surrounded by text that, it stands to reason, was designed to be

Made at Echternach in the Eighth and Eleventh Centuries and Issues of read aloud and thus performed on repeated occasions. I would also suggest

Patronage, Monastic Reform and Splendor,” Peregrinations 3, no. 1 (2010): that works created in association with Archbishop Egbert of Trier are often

49–82. possessed of a “speaking” element, which would have been activated in

38 – Anna Bücheler, “Textile Ornament and Scripture Embodied in the their use in liturgical performance; Eliza Garrison, “Movement and Time

Echternach Gospel Books,” in Woodfin and Kapustka, Clothing the Sacred, in the Egbert Psalter,” in Les Représentations du livre aux époques carolingienne et

147–72, at 158–60. David Ganz’s article in this same collected volume ottonienne, ed. Charlotte Denoël, Anne-Orange Poilpré, and Sumi

presents parallel arguments on the metaphorical meanings of medieval Shimahara (Turnhout: Brepols, forthcoming).

228 ELIZA GARRISON

51 – Garrison, Ottonian Imperial Art and Portraiture, 39–86; eadem, “Otto III at Otto I, the most immediate model would have been Charlemagne, and for

Aachen.” Nikephoros Phokas it was none other than Justinian. See also Schulze,

52 – I thank Bill North and Philip Reynolds for assistance with these points. Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin Theophanu, 14.

53 – In addition to the translation given in the appendix, see Reynolds’s 67 – It is possible that the future Ottonian Empress Theophanu was named

brief treatment of the marriage charter’s text; Reynolds, How Marriage after Anastasio Theophanu. For an assessment of Theophanu’s ancestry and

Became One of the Sacraments, 18–19. her biography, see Gunther Wolf, “Wer war Theophanu?,” in Schreiner and

54 – Walter Deeters noted, for example, that the authors of this section of von Euw, Kaiserin Theophanu: Begegnung des Ostens und Westens, II, 385–96; and

the text were taking language from Augustine, noting here that the phrase Otto Kresten, “Byzantinische Epilegomena zur Frage: Wer war

“Ut ostenderet bonas et sanctas esse nuptias legitima institutione celebratas Theophanu?,” in Schreiner and von Euw, Kaiserin Theophanu: Begegnung des

seque auctorem esse earum” derives from language in Augustine’s de bono Ostens und Westens, II, 403–10. Both articles contain numerous references to

coniugali I as well as his de nuptiis et concupiscentia II; Deeters, “Zur the earlier literature on this question. It is not surprising that the question of

Heiratsurkunde der Kaiserin Theophanu,” 12, nn. 24–29. Theophanu’s parentage was of particular interest to scholars working in

55 – Reynolds, How Marriage Became One of the Sacraments, 19. Germany and Austria during the National Socialist period. Mathilde