Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Solving The Procrastination Puzzle

Solving The Procrastination Puzzle

Uploaded by

Yugahang LimbuOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Solving The Procrastination Puzzle

Solving The Procrastination Puzzle

Uploaded by

Yugahang LimbuCopyright:

Available Formats

Insights from Solving the Procrastination Puzzle by Timothy Pychyl

Procrastination takes a series toll on our mental and physical well‐being.

Putting off actions that move us closer to important goals erodes self‐esteem and lowers life satisfaction. Wasting valuable work time

procrastinating generates intense guilt and stress, which leads to bad eating habits and poor sleep. Studies on procrastination find that

frequent procrastinators suffer from stomach aches and headaches. One study found a strong correlation between procrastination and

heart disease.

Despite the long‐term consequences of procrastinating, we still do it for two reasons:

The future self forecasting fallacy: When we put off a task, we assume our future selves will be in a better mood and have the energy to

do it. Essentially, we tell ourselves, "I don't feel like doing this now, but my future self will!" However, we fail to predict the events that will

make our future selves just as busy and just as unwilling to do a task as our current selves are.

The mood enhancement effect: If the thought of doing a task makes us feel down, we can put it off until tomorrow and instantly improve

our mood. Studies show that people in a bad mood are more likely to procrastinate on difficult tasks and seek immediate pleasure.

Combine that with the fact that we value our current emotional state more than a future emotional state – just as we prefer $100 today to

$100 in one month – and it’s easy to see why we have a procrastination bias.

L.E.A.R.N. a new response

The urge to avoid a task starts in an area of the brain called the amygdala. When the amygdala is active, we experience the “fight‐or‐flight”

response. Luckily, we can L.E.A.R.N. to calm down the amygdala when we encounter a task that we don’t feel like doing and reduce the

urge to run away by labeling, exhaling, accepting, releasing, and noticing.

Label the emotion leading to procrastination. When we feel the urge to procrastinate, we must call it out by

thinking, “This is overwhelm,” or “This is anxiety.” Consciously acknowledging a fear‐based emotion is proven to

reduce activity in the amygdala.

Exhale slowly. By consciously exhaling longer than we inhale, we activate a parasympathetic response that

counteracts the fight‐or‐flight response.

Accept whatever you’re feeling. When we resist an uncomfortable emotion, we prolong its presence. But when

we accept a negative emotion, that emotion is no longer perceived as a threat, which further calms the amygdala.

Release muscle tension. Letting go of muscle tension relaxes the body, which relaxes the amygdala.

Notice where the urge to procrastinate is coming from. Searching our bodies for the source of our procrastination

urge puts us in a curious state, which we can then use to explore and move toward a task we didn’t feel like doing.

Set an anti‐procrastination intention

An anti‐procrastination intention (also known as an implementation intention) is a specific “when‐then” statement directed at a frequently

procrastinated task. For example, “When I hear my ‘book writing’ calendar notification at 9 AM, I will open a new Word document on my

laptop and do stream of conscious typing for 5 minutes to generate ideas for the writing session.” Give the brain an explicit cue and a simple

action sequence, and it will act without thought or resistance.

But sometimes, we need extra motivation to start a frequently procrastinated task. That’s why psychologists have come up with the

W.O.O.P. method – Wish, Outcome, Obstacle, Plan. Think of it like implementation intentions on steroids. Complete the following W.O.O.P.

statements for a task or project you’ve been putting off and you’ll find that you need very little willpower to move past your

procrastination and get your work done:

Wish: “I wish to complete ______________________________.”

I fill out this statement by thinking of something I want to finish by the end of the day – it’s typically a project or task I’ve been

putting off.

Outcome: “After I complete ______________________________, I will experience ______________________________.”

I complete this statement by imagining the emotional high I’ll experience when I fulfill my wish in statement one. I typically

write “immense pride,” “excitement,” or “complete satisfaction.”

Obstacle: “However, I won’t experience ______________________________ if I ______________________________.”

I complete this statement by writing the experience I want to have followed by the procrastination tactic that will prevent me

from having it. I typically write: Go down a researching rabbit hole or insist “I’m too tired.” Paradoxically, imagining an optimistic

vision of the future destroyed by procrastination is motivating (not demoralizing) because we hate the feeling of being held

back.

Plan: “When I start to ______________________________, I will ______________________________.”

This is the anti‐procrastination intention (implementation intention). Here I might write, “When I start to think ‘I’m too tired to

work,’ I will get on the floor, do five push‐ups, and get to work.” OR “When I start to browse YouTube, Reddit, or check my email, I

will turn off the phone and stare at the wall until I feel like working again.”

www.ProductivityGame.com

You might also like

- Report Q6WR D58D 2RM3 CTNK HES2Document7 pagesReport Q6WR D58D 2RM3 CTNK HES2Arnav KumarNo ratings yet

- Be Calm, Be Confident: Breaking the Cycle of Negative Thoughts to Regain Emotional FreedomFrom EverandBe Calm, Be Confident: Breaking the Cycle of Negative Thoughts to Regain Emotional FreedomRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- Yellow Fever East Asian Fetish Among Anime Fans OtakusDocument30 pagesYellow Fever East Asian Fetish Among Anime Fans OtakusTazin Khan PromiNo ratings yet

- Making Sense of Anxiety and Stress: A Comprehensive Stress Management ToolkitFrom EverandMaking Sense of Anxiety and Stress: A Comprehensive Stress Management ToolkitRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Brain Training by George Lynch PDFDocument32 pagesBrain Training by George Lynch PDFdluker2pi1256No ratings yet

- Report EXP 3Document16 pagesReport EXP 3Kirin Fazar100% (1)

- Anger and StressDocument5 pagesAnger and StressChristine Garcia RafaelNo ratings yet

- Smarter Goals TemplateDocument2 pagesSmarter Goals TemplateHamada AhmedNo ratings yet

- CBT For Anxiety: A Clinical Psychology Introduction To Cognitive Behavioural Therapy For Anxiety Disorders: An Introductory SeriesFrom EverandCBT For Anxiety: A Clinical Psychology Introduction To Cognitive Behavioural Therapy For Anxiety Disorders: An Introductory SeriesNo ratings yet

- Depression Self HelpDocument12 pagesDepression Self HelpFuzzyANo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word Document - 2Document6 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word Document - 2Arjun PanchalNo ratings yet

- Focused Breathing: I Need To Warm Up First by Doing Something ElseDocument8 pagesFocused Breathing: I Need To Warm Up First by Doing Something ElseejlksfjdlkNo ratings yet

- Letting Go of Stress, Anxiety, and Fear During Study and Test TakingDocument3 pagesLetting Go of Stress, Anxiety, and Fear During Study and Test TakingRamonNo ratings yet

- StressDocument2 pagesStressОлена ІшутінаNo ratings yet

- We All Worry and Get Upset From Time To TimeDocument8 pagesWe All Worry and Get Upset From Time To TimeMohamad AsrulNo ratings yet

- How To Stop ProcrastinationDocument4 pagesHow To Stop ProcrastinationTanvirNo ratings yet

- How Successful People Stay CalmDocument4 pagesHow Successful People Stay CalmHarshNo ratings yet

- The 3-Step Workday Reset PDFDocument16 pagesThe 3-Step Workday Reset PDFMarleneNo ratings yet

- E 8-Point Check-Up: "Mental Maintenance"Document9 pagesE 8-Point Check-Up: "Mental Maintenance"Volkan VVolkanNo ratings yet

- How Successful People Stay CalmDocument6 pagesHow Successful People Stay CalmBrayan CigueñasNo ratings yet

- If You Find Yourself Becoming Overly AnxiousDocument3 pagesIf You Find Yourself Becoming Overly Anxiousvoyager133100% (1)

- 5 Ways To Stop Your Racing ThoughtsDocument3 pages5 Ways To Stop Your Racing ThoughtsVladimir KostovskiNo ratings yet

- Steps in The Self Exploration ProcessDocument3 pagesSteps in The Self Exploration Processrezzel montecilloNo ratings yet

- Mental Health EbookDocument48 pagesMental Health EbookJulia AdrienNo ratings yet

- Twelve Ways To Cure Procrastination: 1: Make Sure You Have To Do ItDocument5 pagesTwelve Ways To Cure Procrastination: 1: Make Sure You Have To Do ItgheljoshNo ratings yet

- 4.1 PerspectiveDocument3 pages4.1 Perspectiveionut307No ratings yet

- Instant Energy: How to Get More Energy Instantly!From EverandInstant Energy: How to Get More Energy Instantly!Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Stop Overthinking - The Power of Mindfulness for a Happier Life: Unlock Your Inner Brilliance: Overcome Overthinking, Eliminate Negative Thoughts, and Tap into Your Full Potential for a Life of Unlimited Happiness and SuccessFrom EverandStop Overthinking - The Power of Mindfulness for a Happier Life: Unlock Your Inner Brilliance: Overcome Overthinking, Eliminate Negative Thoughts, and Tap into Your Full Potential for a Life of Unlimited Happiness and SuccessRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- MBSR Week2Document10 pagesMBSR Week2JOUBBANE FADOUANo ratings yet

- 7 Steps To Maximize Your Full Potential NDocument20 pages7 Steps To Maximize Your Full Potential Nkingscorp100% (1)

- Tap Into Your TruePotential With EFTDocument23 pagesTap Into Your TruePotential With EFTPeter Möhle100% (6)

- Fight-Or-Flight Response: What Happens in The BodyDocument5 pagesFight-Or-Flight Response: What Happens in The BodyjbcarilloNo ratings yet

- PERDEV Doc 2Document8 pagesPERDEV Doc 2Ahrts Quintana Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- No More Brain Fog: Why You Might Be Struggling With Head Fogginess & How To Beat ItFrom EverandNo More Brain Fog: Why You Might Be Struggling With Head Fogginess & How To Beat ItNo ratings yet

- Switch Off PanicDocument29 pagesSwitch Off PanichacerNo ratings yet

- Defusion HomeworkDocument3 pagesDefusion HomeworkkasiaNo ratings yet

- Psychology of ProcrastinationDocument7 pagesPsychology of ProcrastinationPauline Wallin100% (3)

- To Tell The Chronic Procrastinator To Just Do It Would Be Like Saying To A Clinically Depressed Person, Cheer UpDocument4 pagesTo Tell The Chronic Procrastinator To Just Do It Would Be Like Saying To A Clinically Depressed Person, Cheer UpAbhishekNo ratings yet

- Book SampleDocument23 pagesBook SampleJakirNo ratings yet

- Avoid Caffeine, Alcohol, and NicotineDocument4 pagesAvoid Caffeine, Alcohol, and NicotineVincent Orl MontalbanNo ratings yet

- RelaxationDocument7 pagesRelaxationlaki lakiNo ratings yet

- A Short Course in ScryingDocument23 pagesA Short Course in Scryingmariosergio05No ratings yet

- Stomping Out StressDocument24 pagesStomping Out Stressapi-641012969100% (2)

- Recover Stronger GuideDocument29 pagesRecover Stronger GuideEde GedeonNo ratings yet

- Insights From Rethinking Positive Thinking by Gabriele OettingenDocument1 pageInsights From Rethinking Positive Thinking by Gabriele OettingenChritian Laurenze LauronNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11.2Document4 pagesChapter 11.2BAT1N Daniel Cortes ContrerasNo ratings yet

- 752cstress ManagementDocument14 pages752cstress ManagementGaurav GirdharNo ratings yet

- Stop and Breathe: Simple Steps To Help You Cope With AnxietyDocument3 pagesStop and Breathe: Simple Steps To Help You Cope With AnxietyCardo DalisayNo ratings yet

- What To Do When You Feel OverwhelmedDocument6 pagesWhat To Do When You Feel OverwhelmedAnonymous WA0ihASNo ratings yet

- Calm BreathDocument6 pagesCalm BreathOVVCMOULINo ratings yet

- Perdev - Stress MGT - 2Document15 pagesPerdev - Stress MGT - 2sheilaNo ratings yet

- How To Do Things You Hate: Self-Discipline to Suffer Less, Embrace the Suck, and Achieve AnythingFrom EverandHow To Do Things You Hate: Self-Discipline to Suffer Less, Embrace the Suck, and Achieve AnythingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Cognitive Errors: DefinitionDocument22 pagesCognitive Errors: DefinitionMuhammad Ali ParachaNo ratings yet

- Communications201312 DLDocument132 pagesCommunications201312 DLhhhzineNo ratings yet

- Guide On PE TopicsDocument3 pagesGuide On PE TopicsXyrell Jane MarquezNo ratings yet

- 057 Mikropor Dentvac A5 Leaflet Ing 251220Document2 pages057 Mikropor Dentvac A5 Leaflet Ing 251220luisNo ratings yet

- Oppenheimer The Secrets He Protected and The Suspicions That Followed HimDocument6 pagesOppenheimer The Secrets He Protected and The Suspicions That Followed HimEwa AnthoniukNo ratings yet

- Lillian Moller GilbrethDocument7 pagesLillian Moller GilbrethjonNo ratings yet

- LP Phy Sci Q2-M3 (W1)Document3 pagesLP Phy Sci Q2-M3 (W1)MARIA DINA TAYACTACNo ratings yet

- Geometric Design Tolerancing - Theories, Standards and ApplicationsDocument467 pagesGeometric Design Tolerancing - Theories, Standards and ApplicationspejNo ratings yet

- Topic 62 Multi-Factor Risk Metrics and Hedges - AnswersDocument7 pagesTopic 62 Multi-Factor Risk Metrics and Hedges - AnswersSoumava PalNo ratings yet

- SQL For Data Science Project Week 4Document25 pagesSQL For Data Science Project Week 4Joseph Alexander ReyesNo ratings yet

- TempDocument3 pagesTempParth Joshi100% (1)

- GR6A1 LN 2nd QTRDocument14 pagesGR6A1 LN 2nd QTRAzlynn Courtney FernandezNo ratings yet

- Dimension:: Blind RivetsDocument1 pageDimension:: Blind RivetsrimshadtpNo ratings yet

- Biology 1 - Cell-Basic Unit of LifeDocument22 pagesBiology 1 - Cell-Basic Unit of LifeAryan MendozaNo ratings yet

- F Microgrids Development and ImplementationDocument303 pagesF Microgrids Development and Implementationsri261eeeNo ratings yet

- Sources of Magnetic FieldsDocument13 pagesSources of Magnetic FieldsAbdalla FarisNo ratings yet

- Poem 2 Geography LessonDocument5 pagesPoem 2 Geography LessonPritanshi ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Torres 2021Document35 pagesTorres 2021Karol FernandesNo ratings yet

- GBPSAT-500-EE-6501-0024-0 GGD Schematic Diagram (Incoming) PDFDocument3 pagesGBPSAT-500-EE-6501-0024-0 GGD Schematic Diagram (Incoming) PDFJoed Garzon MontalbanNo ratings yet

- Hazard Identification, Risk Assessment, and Determining Control (HIRADC) Method in A University Laboratory in Surabaya, IndonesiaDocument6 pagesHazard Identification, Risk Assessment, and Determining Control (HIRADC) Method in A University Laboratory in Surabaya, IndonesiaPasta GigiNo ratings yet

- Livelihood Strategies Sustaining Household Food SecurityDocument121 pagesLivelihood Strategies Sustaining Household Food SecurityMesfin GetachewNo ratings yet

- Resume For Student VisaDocument5 pagesResume For Student Visaafmrlxxoejlele100% (1)

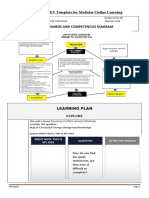

- 2021 JHS INSET Template For Modular/Online LearningDocument14 pages2021 JHS INSET Template For Modular/Online LearningMJ GuinacaranNo ratings yet

- Coding Form BarangDocument7 pagesCoding Form Barangzalfa yourpackagingsolutionNo ratings yet

- Low Quality Problems: Jeffrey Chen and Kevin ZhaoDocument2 pagesLow Quality Problems: Jeffrey Chen and Kevin ZhaoNadiaNo ratings yet

- Ch110 Lab Report WritingDocument5 pagesCh110 Lab Report WritingLazy BanditNo ratings yet

- Progress Test 9: Cause or Have in The Correct FormDocument3 pagesProgress Test 9: Cause or Have in The Correct FormYoncé Ivy KnowlesNo ratings yet

- Arsovski Miodrag-70 Godini Š.K.kumanovoDocument102 pagesArsovski Miodrag-70 Godini Š.K.kumanovoDimitar KacakovskiNo ratings yet