Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in Sound Action v. King County and Mike Spranger

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in Sound Action v. King County and Mike Spranger

Uploaded by

Alex BruellOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in Sound Action v. King County and Mike Spranger

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in Sound Action v. King County and Mike Spranger

Uploaded by

Alex BruellCopyright:

Available Formats

1 SHORELINES HEARINGS BOARD

STATE OF WASHINGTON

2

SOUND ACTION, a Washington non-profit

3 corporation,

SHB No. 23-002

4 Petitioner,

v. FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF

5 LAW AND ORDER

KING COUNTY, a political subdivision of

6 the State of Washington; and

MIKE SPRANGER, Applicant,

7

Respondents.

8

9 I. INTRODUCTION

10 On February 1, 2023, Petitioner Sound Action filed a petition with the Shorelines Hearings

11 Board (Board) for review of two 1 decisions: (1) the Shoreline Substantial Development Permit

12 Report and Decision issued by King County on January 10, 2023, to approve File No. SHOR22-

13 0015, a proposal titled SPARO Kelp and Shellfish Farm and (2) King County’s Mitigated

14 Determination of Nonsignificance for SPARO Kelp and Shellfish Farm.

15 The Board held a seven-day hearing on this matter on May 1-9, 2023, by Zoom

16 videoconference. The Board deciding this matter was comprised of Board Chair Carolina Sun-

17 Widrow, and Members Neil L. Wise, 2 Michelle Gonzalez, Jason Sullivan, and Dennis Weber.

18 Administrative Appeals Judge Heather L. Coughlan presided for the Board. Attorney

19

1

In its petition, Sound Action also listed a third decision: the Shoreline Substantial Development Permit Application

20 Decision. Pet. for Review, p. 1. Sound Action’s Closing Brief only seeks reversal of the Permit and the Mitigated

Determination of Nonsignificance. As a result, the Board concludes that the third decision has either been abandoned

21 or combined with the Permit. Sound Action’s Closing Br., p. 20.

2

Board Member Wise participated in the hearing and Board discussion but retired before issuance of this decision.

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

1

1 Kyle A. Loring represented Petitioner Sound Action. Attorneys Lena Madden and Noah Mikell

2 represented Respondent King County. Attorney Jesse G. DeNike represented Respondent

3 Mike Spranger. Court Reporters Evelyn Adrean, Nicole Buldis, Patricia Jacoy, Nancy Kottenstette,

4 Andrea Ramirez, and Anita Self of Buell Realtime Reporting LLC provided court reporting

5 services.

6 The parties agreed to 17 legal issues governing this appeal, as established in the February 28,

7 2023, Prehearing Order. Sound Action has withdrawn legal issues 12, 15, 16, and 17, Sound Action

8 Closing Br., p. 2, leaving the following issues to be resolved:

9 1. Did King County clearly err under the State Environmental Policy Act (“SEPA”) on the

basis that it applied the optional [Determination of Nonsignificance (“DNS”)] process

10 to review the impacts of a novel type of marine development when that integrated review

process is reserved for proposals for which the lead agency has a reasonable basis for

11 determining that significant adverse environmental impacts are unlikely?

12 2. Did King County clearly err under SEPA when it issued the Mitigated Determination of

Nonsignificance (“MDNS”) on the basis that it did not have reasonably sufficient

13 information about the location of the kelp and shellfish installation and critical saltwater

habitats like seagrass and macroalgae, and without reasonably sufficient information

14 about the amount of shade that will be caused by the kelp facility, the number of anchors

that will displace critical saltwater habitats, and risks to orcas and humpback whales

15 known to spend time in the area, including but not limited to entanglement and exclusion

from a feeding area?

16

3. Did King County clearly err by issuing an MDNS on the basis that it did not carefully

17 consider the full range of probable impacts, including short-term and long-term impacts,

as required by KCC 20.44.030 and WAC 197-11-060(4)(c)?

18

4. Was King County’s decision to issue the MDNS clearly erroneous on the basis that the

19 mitigation conditions do not require redress for project impacts associated with cetacean

entanglement and feeding exclusion and shade and displacement impacts to submerged

20 aquatic vegetation within and adjacent to the project footprint?

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

2

1 5. Did King County clearly err by determining that an Environmental Impact Statement

was not required on the basis that this is a novel type of commercial development with

2 unevaluated impacts associated with cetacean entanglement and feeding exclusion and

shade and displacement of critical saltwater habitats?

3

6. Does Permit No. SHOR22-0015 (“Permit”) conflict with Comprehensive Plan policy S-

4 207 on the basis that it is inconsistent with the hierarchy of uses that King County must

observe for shorelines of statewide significance?

5

7. Does the Permit conflict with Comprehensive Plan policy S-538 on the basis that it is

6 inconsistent with the policy that all developments and uses on navigable waters or their

beds in the Aquatic Shoreline Environment be located and designed to minimize

7 interference with surface navigation, to consider impacts to public views, and to allow

for the safe, unobstructed passage of fish and wildlife and materials necessary to create

8 or sustain their habitat, particularly those species dependent on migration?

9 8. Does the Permit conflict with Comprehensive Plan policy S-539 on the basis that it is

inconsistent with the policy not to allow uses in the Aquatic Shoreline Environment that

10 adversely impact the ecological processes and functions of critical saltwater and

freshwater habitats, except when necessary to achieve the objectives of Revised Code

11 of Washington 90.58.020, and then only when the adverse impacts are mitigated

according to the sequence described in Washington Administrative Code 173-26-

12 201(2)(e) as necessary to ensure no net loss of shoreline ecological processes and

functions?

13

9. Does the Permit conflict with the [shoreline master program (“SMP”)] on the basis that

14 it is inconsistent with the SMP’s no net loss standards, including the policy that the

County shall ensure that new uses, development and redevelopment within the shoreline

15 jurisdiction do not cause a net loss of shoreline ecological processes and functions

(Comprehensive Plan policy S-601), the requirement to ensure that the use and

16 modification of the nearshore area for a commercial kelp growing facility does not cause

a net loss of shoreline functions and complies with the sequencing requirements under

17 KCC 21A.25.080 (KCC 21A.25.090), and the requirement to apply the mitigation

measures pursuant to the order of priority established by the mitigation sequence

18 (KCC 21A.25.080)?

19 10. Does the Permit conflict with Comprehensive Plan policy S-631 on the basis that it is

inconsistent with the policy that docks, bulkheads, bridges, fill, floats, jetties, utility

20 crossings, and other human-made structures shall not intrude into or over critical

saltwater habitats except when conditions are satisfied?

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

3

1 11. Does the Permit conflict with Comprehensive Plan policy S-718 on the basis that it is

inconsistent with the policy that aquaculture activities shall be designed, located and

2 operated in a manner that supports long-term beneficial use of the shoreline and protects

and maintains shoreline ecological processes and functions, and that aquaculture permits

3 shall not be approved where it would result in net loss of shoreline ecological functions;

net loss of habitat for native species including eelgrass, kelp, and other macroalgae;

4 adverse impacts to other habitat conservation areas; or interference with navigation or

other water-dependent uses?

5

13. Does the Permit conflict with the SMP on the basis that it is inconsistent with the SMP’s

6 standards for experimental activities, including the policy that experimental aquaculture

projects in water bodies should be limited in scale and should be approved for a limited

7 period of time (Comprehensive Plan policy S-725), the requirement to include specific

performance measures and provisions for adjustment or termination of the project if

8 monitoring indicates that significant, adverse environmental impacts cannot be

adequately mitigated (KCC 21A.25.110.I), and the limitations on experimental facilities

9 to five acres in area and three years in duration (KCC 21A.25.110.J), given the potential

impacts of the facility on cetaceans and underlying and adjacent submerged aquatic

10 vegetation and lack of tested methodology?

11 14. Does the Permit conflict with the SMP on the basis that KCC 21A.25.110.W directs that

aquaculture shall not be approved where it will adversely impact eelgrass and

12 macroalgae?

13 The Board received prehearing briefs, sworn testimony of witnesses, exhibits, and written

14 closing arguments. Based upon the evidence and arguments presented, the Board enters the

15 following Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law, and Order affirming the King County Department

16 of Local Services, Permitting Division’s Shoreline Substantial Development Permit and Mitigated

17 Determination of Non-Significance, with an additional modification.

18

19

20

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

4

1 II. FINDINGS OF FACT

2 Project Background

3 1.

4 Mike Spranger proposed the SPARO Kelp and Shellfish Farm (Project), consisting of an

5 integrated and regenerative kelp (seaweed) and shellfish farm that would grow sugar kelp, clams,

6 mussels, oysters, and possibly scallops at one location. Kelp and seaweed are used interchangeably

7 here and refer to the species Saccharina latissima. All the species are either native or naturalized to

8 the proposed area. The appeal focused mainly on the kelp proposed to be grown from seeds attached

9 to lines and secured with a system of anchors, buoys, and suspended lines. Ex. RKC1, pp. 0001,

10 0003.

11 2.

12 The Project would be located 300 feet offshore of the mean low tide at the southwest corner

13 of Vashon Island, in Colvos Passage. The site would be entirely in open water, between depths of

14 30 feet and 80 feet. Ex. RKC1, p. 0001. The site measures approximately 1,200 feet by 350 feet, for

15 a total of 9.6 acres. Ex. RKC4, p. 0001. The maximum farmable area of the site, however, is 6.6

16 acres. Spranger Testimony at 814. In comparison, Colvos Passage is approximately 9,819.97 acres.

17 Ex. RKC12, p. 10. Puget Sound, where the Project would be located, is a shoreline of statewide

18 significance and within the designated Aquatic environment under the King County Shoreline

19 Master Program (SMP). KCC 21A.25; Ex. RKC1, p. 0001. The purpose of the Aquatic environment

20 designation is to protect, restore, and manage the unique characteristics and resources of the areas

21 waterward of the ordinary high-water mark. The adjacent shoreland environment is designated as

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

5

1 Conservancy. KCC 21A.25; Ex. RKC1, p. 0008. The purpose of the Conservancy shoreline is to

2 conserve areas that are a high priority for restoration, including valuable historic properties, or to

3 provide recreational opportunities. Ex. RKC1, p. 0008.

4 3.

5 Spranger hired a marine engineering firm, DSA Ocean, to design the farm. Spranger

6 Testimony at 813; Ex. RS11. Colin Wilson, the registered engineer who led the analysis for the

7 Project design, has ten years’ experience at DSA Ocean as a marine and hydrodynamic engineer.

8 Wilson Testimony at 1216-17, 1219; Ex. RS24 (Wilson CV). DSA Ocean completed a metocean

9 assessment, using a one-in-50-year storm condition to determine the necessary size of the anchors

10 and mooring components. Wilson Testimony at 1219. DSA Ocean also determined wave loads

11 based on fetch (distance along open water or land over which the wind blows 3) and storm duration,

12 using data from local weather stations. Id. at 1220. Wilson testified that DSA Ocean applied

13 relevant international standards throughout its analysis. Id.

14 4.

15 Spranger contacted and obtained approval for the Project from several federal, state, and

16 local agencies. He first contacted the Puyallup Tribe, which supported the Project. Spranger

17 Testimony at 843. In October 2021, Spranger began to seek approval from King County and, around

18 the same time, from the State of Washington, Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW). Id. at

19 843-44. He also obtained approval from the State of Washington, Department of Ecology. Id. at

20

21

3

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/fetch

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

6

1 843. Spranger also proceeded through the Army Corps of Engineers’ (Corps) approval process. Id.

2 at 848. The Corps shared information regarding the Project with the National Marine Fisheries

3 Service (NMFS) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Id. at 849. Both NMFS and

4 USFWS issued letters of concurrence regarding the Project. Spranger Testimony at 849; Ex. RKC14

5 (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Concurrence Letter). After those two federal agencies issued letters

6 of concurrence, the Corps approved the Project. Spranger Testimony at 849-50; Ex. RKC18 (Corps

7 Permit). The Corps then contacted the U.S. Coast Guard, which required Spranger to install buoys

8 as navigational aids at each side of the Project grow area. Spranger Testimony at 850.

9 5.

10 Around October 2022, after contact from Sound Action, the Corps reinitiated its approval

11 so that NMFS could evaluate the Project’s potential effects on humpback whales. Carey Testimony

12 at 331-35; Spranger Testimony at 895-96. NMFS issued an updated letter, concluding that the

13 Project’s effects on the movement of humpback whales and Southern Resident Killer Whales

14 (SRKW) was insignificant considering the size of the farm relative to the passage, SRKW’s

15 echolocation abilities, the lack of any reported entanglements of humpback whales or SRKW with

16 kelp aquaculture farms, and the lower probability of an ESA-listed Distinct Population Segment of

17 humpback whales in the action area. Ex. RKC12, p. 0012 (NMFS Concurrence Letter). NMFS again

18 concurred with the Project, and around January 2023 the Corps again approved it. Spranger

19 Testimony at 896.

20

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

7

1 Other Kelp Farms

2 6.

3 The Project would not be the only seaweed farm in Washington state. Blue Dot Sea Farm is

4 a seaweed and shellfish integrated suspended aquaculture farm in North Hood Canal. Davis

5 Testimony at 1515-16. Dr. Jonathan Davis is Blue Dot Sea Farm’s co-founder and senior scientist.

6 Ex. RS36, p. 1 (Davis CV). Davis completed his Ph.D. in fisheries in 1994 and has worked as a

7 researcher in the shellfish industry since that time. Davis Testimony at 1515; Ex. RS36. He is also

8 an affiliate professor at the University of Washington School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences. Id.

9 at 1515.

10 7.

11 Blue Dot Sea Farm has been cultivating seaweed and shellfish at its 5.7-acre site since 2016.

12 Id. at 1516. Davis testified that the seaweed Blue Dot Sea Farm cultivates is grown based on

13 methods that have been used extensively throughout the world. Id. Blue Dot Sea Farm currently

14 cultivates sugar kelp, which it typically plants on grow lines in late November and harvests at the

15 end of March or the first week of April. Id. at 1516-17. Davis is familiar with the methods and

16 technologies that Spranger plans to use for the Project and stated that Spranger’s approach is

17 essentially the same as what Blue Dot Sea Farm has been doing in North Hood Canal. Id. at 1530-

18 31. Davis testified that seaweed cultivation is quite standardized throughout the industry. Id. at

19 1531.

20

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

8

1 8.

2 Lummi Island SeaGreens, based near Lummi Island, also farms kelp. Spranger Testimony

3 at 841. Spranger testified that Lummi SeaGreens was recently granted a permit and harvested

4 seaweed in April. Id. Similar to the Project’s design, Lummi Island SeaGreens grows sugar kelp

5 from seeds attached to lines, which are secured with anchors. Id.

6 9.

7 The Board also heard testimony regarding similar kelp farms outside of Washington. Scott

8 Lindell, a research specialist with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, reviewed the Project

9 design and testified that it was the same design his lab had been using successfully for five years in

10 New Hampshire, where the design supports five lines that are 200–300 feet in length. Lindell

11 Testimony at 1261, 1270. Lindell’s lab has been using a much larger but similarly designed system

12 in Kodiak, Alaska, for four years. Id. at 1270.

13 King County Permitting Process

14 10.

By statute, the lead agency is a local government which oversees the process of issuing a

15

shoreline substantial development permit (SSDP) consistent with the Shoreline Management Act

16

(SMA), its own SMP, and other regulations. See RCW 90.58.140(1)-(2). King County is the lead

17

agency, which issued the SSDP for the Project. Ex. RKC10. King County is also the lead agency,

18

which issued the Mitigated Determination of Nonsignificance (MDNS) pursuant to the State

19

Environmental Policy Act (SEPA), Ch. 43.21C RCW.

20

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

9

1 11.

2 King County Department of Local Services, Permitting Division (Permitting) conducted a

3 preliminary review of the Project during the pre-application process that began in October 2021,

4 months before the application was submitted. Spranger Testimony at 847-48. Spranger recalls that

5 King County assigned staff to conduct the pre-application review in March 2022. Id. at 844. On

6 June 2, 2022, Spranger applied to King County for an SSDP for the Project. Ex. RKC1, p. 0001.

7 12.

8 Ty Peterson testified for King County regarding its permitting process. Peterson is the

9 commercial product line manager for Permitting. Peterson Testimony at 975; Ex. RKC52 (Peterson

10 Resume). He has an undergraduate degree in urban and regional planning and a graduate degree in

11 construction management technology. Id. at 979. Peterson has worked for King County for nearly

12 ten years. Id. He estimates that in that time he has reviewed an average of 20 SSDP permits per

13 year. Id. at 977-78. Prior to working for King County, Peterson worked for several cities as a

14 planner, planning and development services manager, and community development and public

15 works director. Id. at 979-80; Ex. RKC52.

16 13.

17 Peterson has served as the designated SEPA official for his entire tenure at King County

18 and for a total of more than 20 years in the various jurisdictions for which he has worked. Peterson

19 Testimony at 987-88. A SEPA official is the lead agency’s designee who is essentially responsible

20 for carrying out the agency’s duties under SEPA. Id. at 988. One determination a SEPA official

21 must make is whether a project is exempt under SEPA. If a project is not exempt under SEPA, then

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

10

1 review proceeds to assess whether the SEPA threshold determination is likely to be a Determination

2 of Significance (DS), DNS, or MDNS. Id. at 988-89. One of those three determinations is reached

3 before King County can proceed with issuance of a permit decision that is subject to SEPA. Id. at

4 989.

5 14.

6 King County uses the optional DNS process for the majority of SEPA-related permit

7 applications. Peterson Testimony at 1014-16. The optional DNS process is allowed under

8 WAC 197-11-355. The notice must specify that the agency expects to issue a DNS for the proposal,

9 that the optional DNS process is being used, that the comment period announced in the notice may

10 be the only opportunity to comment on the environmental impacts of the proposal, and that a copy

11 of the subsequent threshold determination for the proposal may be obtained upon request.

12 WAC 197-11-355(2)(a); See also Peterson Testimony at 1014. Peterson testified that King County

13 uses the optional DNS process by default because it would not be able to issue two separate public

14 notices within the required timeline for rendering a permit decision. Peterson Testimony at 1015-

15 16. Among other recipients specified in the regulation, the notice of application and environmental

16 checklist must be sent to anyone who requests a copy of the environmental checklist for the specific

17 proposal. WAC 197-11-355(2)(d). The responsible official must consider timely comments on the

18 notice of application and then may take actions including issuing a DNS or MDNS with no

19 comment period or requiring additional information or studies prior to making a threshold

20 determination. WAC 197-11-355(4). Under the optional DNS process, King County may include

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

11

1 in the notice the likely SEPA determination. Id. at 1014. Listing the likely SEPA determination,

2 however, does not bind the agency to a particular determination. Id. at 1016, 1033-34.

3 15.

4 King County used the optional DNS process for the Project, issuing a Notice of Application

5 on August 11, 2022. Ex. RKC4, p. 0001. The Notice of Application states that the optional DNS

6 process was being used and that the responsible official had a reasonable basis for expecting to

7 issue a SEPA DNS. Id. The public comment period for the Notice of Application extended to

8 September 13, 2022, and the Notice of Application states that the provided comment period may

9 be the only opportunity to comment on the environmental impacts of the proposal. Id. Peterson

10 testified that King County continues to accept comments after the comment period has closed,

11 however, until the time it makes a decision. Peterson Testimony at 1040. Public comments were

12 received and reviewed by King County and the applicant. Ex. RKC1, p. 0002. The applicant

13 provided written responses to the public comments. Id.

14 16.

15 King County relied in part on federal agencies—NMFS and USFWS—in reviewing the

16 status of the location as a foraging area for marine mammals. See Peterson Testimony at 1171-72.

17 17.

18 During the review process, King County required Spranger to complete a macroalgae survey

19 on the Project site. Spranger Testimony at 851. Before completing the survey, Spranger reviewed

20 survey guidelines from WDFW and obtained advice from an environmental consulting firm,

21 Confluence Environmental Company, on how to conduct the survey. Id. at 852-53, 890;

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

12

1 Ex. RKC15. Spranger conducted the survey in May 2022, using his remote-operated vehicle (ROV).

2 Spranger Testimony at 851-52; Ex. RKC15, p. 0004. He completed the survey by using GPS

3 coordinates to identify the site, then he divided the site into transects, along each of which he guided

4 the ROV, taking either video or pictures of the seafloor from the ROV as it drove along each

5 transect. Spranger Testimony at 881-82; Ex. RKC15, pp. 0005-06. The transects were spaced 50

6 feet apart. Spranger Testimony at 882; Ex. RKC15, p. 0005.

7 18.

8 To estimate the macroalgae coverage in the Project site, Spranger printed a picture of the

9 site and overlaid it with a grid, filling in boxes in the grid where he found macroalgae during the

10 survey. Spranger Testimony at 883. He concluded that there was macroalgae coverage between 10

11 and 60 percent in certain areas of the Project site, which decreased in coverage as the depth

12 increased. Id. at 883-84; Ex. RKC15, p. 0006. Confluence confirmed the identity of the macroalgae

13 found. Spranger Testimony at 853. While Spranger stated in the survey that “a comprehensive

14 identification of macroalgae species” was beyond the scope, Ex. RKC15, p. 0007, Spranger testified

15 that he meant this statement to allude to the fact that the survey did not reflect spores and other

16 microscopic components of macroalgae, which would not be visible from the ROV. Spranger

17 Testimony at 884. Spranger testified that although there is a bull kelp bed approximately 750 feet

18 away from the Project site, he saw only one piece of bull kelp at the site itself, which was located

19 at a shallower elevation than he planned to plant sugar kelp. Id. at 868.

20

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

13

1 19.

2 King County considered whether the Project constituted an “experimental” aquaculture project

3 under the Comprehensive Plan. Peterson Testimony at 1102. The Comprehensive Plan provides:

4 “Experimental aquaculture projects in water bodies should be limited in scale and should be

5 approved for a limited period of time. Experimental aquaculture means an aquaculture activity that

6 uses methods or technologies that are unprecedented or unproven in the State of Washington.” King

7 County Comprehensive Plan, Policy S-725 (Policy S-725). Because King County had not processed

8 this type of aquaculture before, it asked its consultants and staff whether the Project was

9 “experimental.” Id. at 1103. Peterson testified that staff and decision makers at King County

10 ultimately agreed that the Project—which uses a series of anchors, lines, and buoys—would not

11 use methods or technologies that are unprecedented or unproven in the state of Washington. Id.

12 Rather, these methods and materials are used for a variety of purposes, including for mooring ships,

13 docks, and other structures. Id. Thus, King County concluded that the Project would not be an

14 experimental aquaculture project. Peterson Testimony at 1103-04.

15 20.

16 King County prioritized its review of the Project ahead of other applications, per request of

17 the King County Executive. Peterson Testimony at 1109. The review process, however, was the

18 same as if it had not been prioritized ahead of the review of other applications. Id.

19 21.

20 On October 5, 2022, King County requested additional information from Spranger

21 regarding the Project. Ex. P71. On several issues, including potential effects on marine mammals

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

14

1 and macroalgae, King County asked Spranger to provide additional written commentary and

2 documents. Id., pp. 2, 7.

3 Marine Biologist Consultants

4 22.

5 King County coordinated with the King County Department of Natural Resources and Parks

6 (DNRP) to find and retain marine biologists to consult on the Project. Peterson Testimony at 1054-

7 55. King County required outside consultants because Permitting does not employ on-staff marine

8 biologists, and DNRP did not have capacity to assist in reviewing the Project. Peterson Testimony

9 at 1054, 1057. King County retained from the consulting firm Anchor QEA to review the project.

10 Peterson Testimony at 1060.

11 23.

12 The Anchor QEA scope of work, dated August 3, 2022, states that the firm’s marine

13 biologists would assist “King County staff in objectively determining whether the projects have

14 impacts on the surrounding shoreline environments and meet the goals and regulations of the

15 Shoreline Management Act (WAC 173‐27) and King County Shoreline Master Program

16 (KCC 21A.25), particularly from an ecological / biological perspective.” RKC35, p. 0001 (scope

17 of work). Anchor QEA’s review included the scientific credibility of the applicant’s studies, impact

18 analysis, and scientific references. RKC35, p. 0001. In addition, the consultants reviewed potential

19 changes from existing conditions on the following species and habitats: marine mammals

20 (including potential for entanglement), eelgrass and kelp, the benthic community, substrate

21 composition, and protected/Endangered Species Act-listed species (including salmonids, Orca,

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

15

1 other marine mammals), non-listed species, and adjacent shorelands. RKC35, pp. 0001-02. The

2 scope of work also included recommending project mitigation measures and reviewing

3 King County reports and decisions. Id., p. 0002.

4 24.

5 Elizabeth Greene, an Anchor QEA principal biologist who reviewed the Project for King

6 County, testified at the hearing. Greene Testimony at 1557; Ex. RKC50 (Greene Resume). Greene

7 has a master’s degree in marine resource management and 23 years’ experience working as a

8 biologist. Greene Testimony at 1557. In her role, Greene evaluates impacts of proposed projects

9 on aquatic resources, primarily aquatic species and their habitats. Greene Testimony at 1557.

10 Earlier in her career, Greene conducted around 10 macroalgae or eelgrass surveys as a diver. Id.

11 at 1560-61. She no longer personally dives to conduct eelgrass or macroalgae surveys, but she

12 manages projects that require hiring a diver to complete such surveys. Id. at 1560.

13 25.

14 Greene completed an initial evaluation on August 31, 2022, and completed a second review

15 around the end of October 2022. Id. at 1587, 1657.

16 In evaluating the Project, Greene reviewed materials including:

17 • Applicable code provisions;

18 • Spranger’s application materials;

19 • An impact analysis prepared by Confluence Environmental Company;

20 • NMFS’s first letter of concurrence;

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

16

1 • The best management practices, avoidance, and minimization measures that

2 Spranger agreed to implement;

3 • USFWS’s letter of concurrence;

4 • The eelgrass and macroalgae survey completed by Spranger with assistance from

5 Confluence;

6 • The permit from the Corps;

7 • The SPARO seaweed/shellfish farm planting and harvesting narrative;

8 • The Biological Evaluation for Informal ESA Consultation; and

9 • The Joint Aquatic Resources Permit application form.

10 Greene Testimony at 1579-80, 1598-1606; Exs. RKC17 (Confluence Impact Analysis), RKC13

11 (SPARO Aquatics Best Management Practices, Avoidance, and Minimization Measures), RKC14

12 (USFWS letter of concurrence), RKC15 (eelgrass and macroalgae survey), RKC18 (Corps permit),

13 RKC20 (SPARO seaweed/shellfish farm planting and harvesting narrative), RKC25 (Biological

14 Evaluation for Informal ESA Consultation), RKC27 (Joint Aquatic Resources Permit application

15 form). During review, Greene also requested additional information from Spranger and reviewed

16 and responded to his written responses. Greene Testimony at 1584-88; Exs. RKC32, RKC34.

17 26.

18 Sound Action challenges King County’s reliance on the NMFS concurrence letter, which

19 it asserts was flawed. Sound Action Closing Br., p. 12. Sound Action contends that the NMFS letter

20 was based on incorrect assertions that humpback whales would not be present at the site and that

21 the site would serve as a core summer habitat for SRKW, such that SRKW would avoid the site

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

17

1 during the winter months when farm activities would occur. Id. As Greene testified, however, it is

2 reasonable to rely on letters of concurrence from NMFS and USFWS because those agencies are

3 required to use best available science and are responsible for managing the recovery of species.

4 Greene Testimony at 1637; Ex. P68; see also Bain Testimony at 706 (Sound Action’s expert

5 acknowledging that NMFS is the main agency responsible for protecting the marine mammals and

6 fish that could be affected by the Project); Gornall Testimony at 1332 (veterinarian with significant

7 experience with marine mammals, agreeing with NMFS’s conclusions). Moreover, as is apparent

8 from the reinitiation process that the Corps and NMFS engaged in, NMFS did consider the

9 presence of humpback whales before issuing its second concurrence letter. Ex. RKC12, p. 0012

10 (NMFS Concurrence Letter). The Board finds it was reasonable for King County to rely on the

11 NMFS concurrence letter.

12 27.

13 Greene also testified regarding potential positive benefits from the Project. Those benefits

14 include increased benthic community diversity and abundance as well as the structure that would

15 provide habitat for fish and other organisms. Greene Testimony at 1629. Based on her evaluation,

16 Greene concluded the Project would not result in a net loss of ecological function or process. Id. at

17 1610. Scientists from King County DNRP performed a quality assurance review of Greene and

18 Montgomery’s work to confirm that they had completed the review that King County had requested.

19 Peterson Testimony at 1062. The DNRP scientists were generally in agreement with the consultants.

20 See Peterson Testimony at 1066, 1071.

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

18

1 King County MDNS and SSDP Issuance

2 28.

3 e On January 10, 2023, King County issued both the MDNS and the SSDP for the Project.

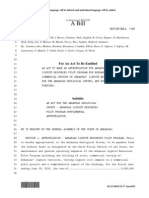

4 Exs. RKC1, RKC10. The Project, as approved by King County, includes six anchors with three

5 arrays of lines. Peterson Testimony at 1084; Spranger Testimony at 817, 948; Ex. RKC1, p. 0003

6 (SSDP provision stating that “[t]he farm will utilize 6 anchor locations to secure the farm in

7 place.”). Each array will be equipped with “spreader bars,” which will allow Spranger to include

8 up to five grow lines per array—constituting a total of 15 grow lines as approved in the SSDP.

9 Spranger Testimony at 819-20, 948. The five-line arrays will be spaced approximately 125 feet

10 apart. Id. at 820. Peterson, who signed the MDNS, testified that he made the final decision about

11 the conditions in the MDNS and that he was satisfied that he had all information he needed to do

12 so. Peterson Testimony at 1042.

13 29.

14 Below is a diagram of the Project, depicting the three arrays of lines and six anchors, with

15 bathymetry measurements showing the depth of each anchor:

16

17

18

19

20

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

19

1

10

11

12 Ex. RS11, p. 3.

13 30.

14 Sound Action contends that King County failed to evaluate the impacts from the complete

15 scope of the Project, citing a Farm Planting and Harvesting Narrative in which Spranger wrote that

16 in years two and beyond he would add more grow lines to fill the full farmable area. Sound Action

17 Closing Br., p. 6; Ex. RKC20, p. 0004. Several of Sound Action’s witnesses testified to their

18 understanding that Spranger would build out the Project to include more than six anchors and three

19 arrays of grow lines. See, e.g., Carey Testimony at 77; Myers Testimony at 411-13.

20

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

20

1 31.

2 The text of the SSDP, however, indicates that Spranger is limited to installing six anchors,

3 which can support a total of three arrays of grow lines. The SSDP states that “[t]he farm will utilize

4 6 anchor locations to secure the farm in place.” Ex. RKC1, p. 0003. The SSDP also provides that

5 the Project “shall be in general conformance to the project plans and information provided by the

6 applicant listed as exhibits in this report, and following, [sic] except as modified by conditions of

7 approval contained herein or as otherwise approved by Permitting.” Id., p. 0019. Peterson testified

8 that this provision means that the Project would need to be constructed in the basic configuration

9 proposed, which in this case includes using six anchors. Peterson Testimony at 1168.

10 32.

11 Consistent with the text of the SSDP, both Spranger and Peterson testified that the Project

12 is limited to the description in the SSDP. Spranger explained his understanding that the SSDP

13 authorizes three arrays with a total of up to 15 lines and that he would need to obtain approval from

14 all relevant agencies if he wanted to add additional arrays or lines. Spranger Testimony at 824-25,

15 866-67. Peterson also testified that the SSDP allows a maximum of six anchors with three arrays

16 that can have up to 15 lines. See Peterson Testimony at 1084.

17 33.

18 Furthermore, Spranger testified that when referring to the full farmable area in the Farm

19 Planting and Harvesting Narrative, he meant the maximal farmable area based on what he could

20 afford and what he paid his marine engineer to design—that is, three arrays attached to a total of

21 six anchors. Spranger Testimony at 916-17. Spranger initially intended to plant between 10 and 15

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

21

1 lines in the first year, as reflected in documents, but later decided to start smaller in the first year

2 and gradually add more lines up to the maximum permitted in the SSDP. Id. at 821-24; see also

3 Ex. RKC20, p. 0004. The Board finds and concludes that King County properly based its review of

4 environmental impacts on the scope of the Project that it approved—that is, six anchors that support

5 three arrays of grow lines, for a total of up to 15 grow lines.

6 34.

7 In the SSDP, King County noted that a map of existing kelp relative to the proposed farm

8 location had been provided. Ex. RKC1, p. 0003. The map and accompanying report show that the

9 two anchors at the shallowest depth were at 30-40’, the two mid-depth anchors would be located at

10 a depth of 50-60’, and the anchors at the deepest position would be at 70-90’. Ex. RKC16, pp. 0001-

11 02. Peterson testified that he used this information in determining where macroalgae was present at

12 the Project site. Peterson Testimony at 1160. King County also imposed a condition requiring

13 additional photographs of macroalgae with an ROV to be taken prior to and at the time of

14 installation of the anchors, and quarterly after that. Id. at 1158; Ex. RKC1, pp. 19-21; Ex. RKC10,

15 p. 8. Annual monitoring of macroalgae extent and quantification of no net loss following WDFW

16 macroalgae survey guidelines to the extent practicable is also required. Ex. RKC1, p. 0021.

17 35.

18 King County imposed several conditions under SEPA to mitigate the potential adverse

19 environmental impacts of the Project. Exs. RKC1, pp. 0019-22; RKC10, pp. 0007-10. The

20 conditions include, among others:

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

22

1 • Siting aquaculture lines in areas where minimal to no existing macroalgae is

2 present;

3 • Positioning of anchors to avoid existing macroalgae to the extent practicable,

4 through the use of an ROV;

5 • Taking photographs upon anchor installation and quarterly after that;

6 • Monitoring of macroalgae extent and quantification of no net loss on an annual basis,

7 following WDFW macroalgae survey guidelines to the extent practicable;

8 • Monitoring before and after construction and operations to see if Project provides

9 benefits or impacts to the benthic community;

10 • Avoiding in-water activities if marine mammals are in the area;

11 • Keeping longlines taut to reduce potential for marine mammal entanglement; and

12 • Developing a marine mammal entanglement response plan.

13 Ex. RKC1, pp. 0019-22.

14 Macroalgae Survey

15 36.

16 Macroalgae Survey

17 Sound Action contends that the macroalgae survey Spranger completed, and King County

18 relied on, was flawed. Sound Action Closing Br., p. 7. To opine on the macroalgae survey, Sound

19 Action called witness Doug Myers, the Maryland senior scientist at the Chesapeake Bay Foundation

20 and a Sound Action Board member. Myers Testimony at 404, 409; Ex. P60 (Myers Resume). Myers

21 discussed eelgrass and kelp surveys, which he has conducted in Puget Sound. Myers Testimony at

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

23

1 435-36. Referring to guidelines prepared by WDFW, Myers testified that a survey should include

2 not just the footprint of the project itself, but an area 25 feet waterward of the project footprint and

3 at 10 and 25 feet from the outer edges of the project footprint. See Myers Testimony at 436; Ex. P6,

4 p. 2 (Eelgrass/Macroalgae Habitat Interim Survey Guidelines). Myers further testified that the

5 survey should be conducted using transects by divers who are qualified to identify species. Myers

6 Testimony at 436.

7 37.

8 According to the WDFW survey guidelines, a preliminary survey is conducted to determine

9 if eelgrass or macroalgae is present at the site, evaluate that the project can be located and constructed

10 to avoid impacting eelgrass or macroalgae, and establish a project location that would minimize

11 impacts when avoidance is impossible. Ex. P6, p. 1. If a preliminary survey indicates that the project

12 footprint potentially impacts existing eelgrass or macroalgae beds, the protocol provides that an

13 advanced survey is required. Id., p. 3. The guidelines state that advanced surveys—to quantify the

14 impacts to eelgrass and macroalgae and to quantify the performance of mitigation actions—shall

15 occur between June 1 and October 1. Id., p. 3.

16 38.

17 Myers testified that the survey was inconsistent with the WDFW guidelines in several

18 respects. Myers Testimony at 439-40, 443. The survey was conducted outside of the June 1 to

19 October 1 timeframe, limited to the actual footprint of the Project site, completed by an ROV

20 instead of a diver, and conducted without the participation of someone who was qualified to identify

21 the species. Id. at 443.

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

24

1 39.

2 On cross-examination, however, Myers acknowledged that the WDFW survey guidelines,

3 as well as protocols of the Corps, were indeed only guidelines from which a permitting agency

4 could deviate. Myers Testimony at 504-05. Similarly, the guidelines concerning the use of a diver

5 rather than an ROV to conduct a survey are not mandatory requirements—they can be waived by

6 the permitting agency. Id. at 506-07.

7 40.

8 Myers opined, however, that these deviations from the survey guidelines mean that the

9 survey could have failed to identify extant macroalgae. The Project survey noted a small area of bull

10 kelp approximately 1,000 feet to the south of the proposed farm site, for example, which Myers

11 testified means that spores from that bull kelp could be moving into the Project area. Id. at 445.

12 Myers testified that without a survey in the proper season, very young bull kelp in the Project site

13 could have been overlooked, particularly when a survey is conducted via ROV rather than by a

14 knowledgeable diver. Id. Myers further noted that just because species like bull kelp and eelgrass

15 are not expressed at one time does not mean they would not be seen in the area at other times. Id. at

16 446. Myers opined that it is important to not just survey an area’s existing kelp, but to also estimate

17 the amount of shading that would result from a project because shade may exclude kelp from

18 growing in the future. Id. at 451.

19 41.

20 Other witnesses, however, opined that the macroalgae survey was sufficient and meets the

21 WDFW Eelgrass/Macroalgae Habitat Survey Guidelines for a preliminary survey, which may be

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

25

1 conducted at any time of year. Greene Testimony at 1611-12, 1617; Ex. P6, p. 2. Greene testified

2 that the macroalgae survey was sufficient for her to evaluate the potential impacts of the Project on

3 macroalgae and eelgrass. Greene Testimony at 1613. Although she was not provided a map with an

4 overlay indicating where macroalgae was present at the Project site, Greene stated that she was

5 given all the information she needed to map out the macroalgae herself. Id. at 1614. Greene

6 reviewed the elevations where macroalgae was found and assumed that a similar percent cover

7 composition would be found at the same elevations throughout the site. Id. at 1614-15; see also

8 Ex. RKC15, p. 9 (survey photos indicating elevation and depicting macroalgae presence) and

9 Ex. RCK16, p. 1 (bathymetry survey showing Project site depths). Greene testified that the survey

10 showed the presence of scattered kelp on the substrate on the bottom, but it did not show any

11 eelgrass or kelp beds. Greene Testimony at 1616-17. Rather, the scattered kelp is interspersed with

12 other types of macroalgae. Id. at 1616.

13 42.

14 Because macroalgae was found in the survey, Greene recommended baseline monitoring as

15 well as postconstruction and operation monitoring on an annual basis to confirm there was no net

16 loss. Greene Testimony at 1617; Ex. RKC1, pp. 0019-20. As stated, she opined the survey was

17 sufficient for a preliminary survey, and her recommendations included using advanced survey

18 protocols for later monitoring. Greene Testimony at 1617. Consistent with Greene’s

19 recommendation, the conditions in the SSDP include “[m]onitoring of macroalgae extent and

20 quantification of no net loss on an annual basis following WDFW macroalgae survey guidelines to

21 the extent practicable.” Ex. RKC1, p. 0021.

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

26

1 43.

2 Greene also testified that it is not atypical that the survey was conducted by video and without

3 a diver, particularly because it is a preliminary survey. Greene Testimony at 1620. Greene found it

4 was also acceptable that the preliminary survey was limited to the Project footprint rather than

5 including the outskirts, which could be monitored in the future per the SSDP condition. Id.

6 44.

7 Chris Cziesla, a marine and fisheries biologist with Confluence Environmental Company,

8 also testified on behalf of Spranger regarding submerged aquatic vegetation and surveys. He has

9 conducted dozens of eelgrass and macroalgae surveys, ranging from small areas to areas of one

10 hundred acres or more. Cziesla Testimony at 1369. In his experience, the survey methods have been

11 modified almost every time for a variety of reasons, including the depth of the location and the

12 plants being observed. Id. at 1424. Cziesla testified that the quadrat system—using a quarter-meter-

13 squared hoop to estimate the density of aquatic plants—is more important when surveying eelgrass.

14 Id. at 1427-28. Macroalgae, on the other hand, is surveyed with more of a “broad brush,” without

15 quantifying percent coverage per species, which Cziesla testified is not required in relevant

16 guidance. Id. at 1428-29.

17 45.

18 Given the characteristics of the Project site, Cziesla testified that a diver transect survey

19 would not be desirable or feasible. Id. at 1432. The site is too deep for eelgrass to grow, and it is a

20 large, uniform site, which would justify reducing the sampling intensity. Id. at 1430-31. Also,

21 because of the two-to-three knot sweeping current, it would be virtually impossible to have a scuba

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

27

1 diver complete the survey using 25-foot transects. Id. Cziesla testified that Spranger’s methods,

2 including using an ROV and the spacing of the transects, were appropriate for the aquatic vegetation

3 survey. Id. at 1438.

4 46.

5 Cziesla also stated that the timing of Spranger’s survey in May, although outside the

6 recommended window of June through October, made sense because Spranger would be harvesting

7 at about that time. Id. at 1441. Although conducting the survey in the summertime would have been

8 better, Cziesla explained that the May window is a borderline month and that he commonly will

9 conduct surveys outside of the recommended window. Id. Additionally, Cziesla testified that

10 images of the proposed anchor sites taken later in the year—in August and September—are

11 consistent with the findings in the earlier survey. Id. at 1442-44; Ex. RKC16.

12 47.

13 The Board finds and concludes that King County did not err in relying on the macroalgae

14 survey. Although Sound Action contends the survey failed to meet certain WDFW survey

15 guidelines, it is undisputed that those guidelines are not mandatory requirements. Rather, as Cziesla

16 and Greene testified there is flexibility in how macroalgae surveys are conducted depending on

17 specific site location and conditions. They further testified that the deviations from the guidelines

18 pointed out by Sound Action here were appropriate and reasonable given site-specific conditions

19 as well as conditions imposed in the SSDP.

20

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

28

1 Macroalgae Impacts

2 48.

3 In addition to challenging the sufficiency of the macroalgae survey, Sound Action contends

4 the Project will impermissibly impact macroalgae, including bull kelp. Sound Action Closing Br.,

5 pp. 15-16. Myers opined that because there are macroalgae present within the shade footprint of the

6 Project, there will be net loss of macroalgae if the Project goes forward. Myers Testimony at 468-

7 69. He further opined that the Project’s proposed growing schedule—seeding the sugar kelp in

8 November and harvesting by April—would not prevent impacts to macroalgae because

9 gametophyte generation may already be present at that time, when the macroalgae would be very

10 sensitive to the amount of light received. Id. at 459; Ex. RKC20, p. 0001.

11 49.

12 Myers criticized the evidence supporting the MDNS as well as the terms within the MDNS.

13 He opined that the MDNS fails to support the conclusion that the Project’s effects on macroalgae

14 would be mitigated by adjusting the location of lines to areas of minimal or no existing macroalgae.

15 Myers Testimony at 470; Ex. RKC10, p. 0003. Furthermore, to the extent mitigation was

16 appropriate, Myers testified that it is impossible to know how the lines can be placed to minimize

17 shading of macroalgae because no macroalgae map was prepared. Myers Testimony at 471.

18 50.

19 Sound Action’s executive director, Amy Carey, testified regarding the presence of a

20 particular type of macroalgae, bull kelp, at the Project site. Sound Action submitted maps prepared

21 by King County DNRP, showing the presence of bull kelp in 2017 or 2019. Ex. P4, p. 1. Carey

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

29

1 testified that these maps depicted the presence of bull kelp along the shoreline, including through

2 the Project area. Carey Testimony at 141; Ex. P4, pp. 2-3. Carey testified that she had seen bull

3 kelp at or near the Project site, which she said is visible during parts of the season when the kelp

4 extends up to the surface. Carey Testimony at 142.

5 51.

6 Witnesses for Spranger disagreed with Sound Action’s assertion that macroalgae would be

7 negatively impacted by the Project. Greene evaluated the potential impact of shading, concluding

8 that there would not be a probable impact to existing macroalgae. Greene Testimony at 1625. This

9 conclusion was based on scientific literature and the short growing season anticipated for the kelp,

10 which would be harvested right at the beginning and just before the macroalgae growth season. Id.

11 at 1624-26; Ex. RKC77. Greene also considered Spranger’s commitments to site the farm in deeper

12 water where there would not be macroalgae, to use an ROV to observe where the anchors were

13 being placed, and to avoid macroalgae to the extent possible. Greene Testimony at 1626. She also

14 found it would be difficult to measure any loss of ecological function from the two anchors that

15 would be placed in areas that supported macroalgae growth, since they are relatively small and their

16 surface area would support macroalgae growth. Id. at 1626-27.

17 52.

18 Even assuming there was a substantial shading of native kelp due to the Project, that would

19 be offset by the kelp that is being cultivated, which is also native. Cziesla Testimony at 1458-63.

20 The farmed kelp will filter nutrients from the water column and will provide a structure for fish and

21 other organisms, including macroalgae that will likely colonize the surface of the anchors. Id. at

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

30

1 1458-59. Cziesla testified that the Project is in an area with generally limited macroalgae presence

2 and that it is sited specifically to avoid the area toward the shoreline, which has the densest

3 macroalgae presence. Id. at 1457-58.

4 53.

5 The Board finds and concludes that Sound Action has failed to show the Project will

6 adversely affect macroalgae. The Project has been sited in an area with minimal macroalgae. In

7 addition, native kelp will grow near the two anchors, which are located in the shallower area of the

8 Project site. While bull kelp has been found near the Project site, the evidence does not establish

9 that it grows at the site itself. Furthermore, the SSDP and MDNS conditions require annual

10 “[m]onitoring of macroalgae extent and quantification of no net loss…” Exs. RKC1, p. 0021;

11 RKC10, p. 10.

12 Whale Impacts

13 54.

14 Sound Action contends King County failed to adequately consider the risks the Project poses to

15 whales.

16 Carey Motion in Limine

17 55.

18 Carey, Sound Action’s executive director, testified regarding the Project’s effects on

19 whales. Carey Testimony at 25. Sound Action’s mission is the protection of nearshore habitat and

20 species. Carey Testimony at 26. As executive director, Carey regularly reviews environmental

21 assessments and works with scientists and project collaborators. Carey Testimony at 27; see also

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

31

1 Ex. P58 (Carey Resume). Carey is not a research scientist. Carey Testimony at 44. As a resident of

2 Vashon Island, however, Carey has been monitoring and tracking SRKW around the island. Id. at

3 54. Carey has visited the Project site. Id. at 32.

4 56.

5 Before the hearing, King County and Spranger moved in limine to exclude Carey’s expert

6 testimony regarding ecological processes and functions or impacts on nearshore habitat or species.

7 Respondents’ Mot. in Limine to Limit Amy Carey’s Expert Testimony and Opinions. The Board

8 initially denied the motion in limine so that more foundation for Carey’s testimony could be

9 provided at hearing. Order on Mot. in Limine, p. 7 (Apr. 28, 2023).

10 57.

11 The Pollution Control Hearings Board (PCHB) has ruled on the admissibility of Carey’s

12 expert testimony in two cases that have recently been reviewed by the Court of Appeals. In an

13 unpublished decision, the Court of Appeals affirmed the PCHB’s decision to partially exclude

14 Carey’s testimony, concluding “that the Board’s determination that Carey was not an expert in

15 nearshore ecology and development impacts was not arbitrary and capricious.” Sound Action v.

16 Pollution Control Hr’gs Bd., No. 56641-9-II, 2023 Wash. App. LEXIS 424, at *51 (Ct. App. Mar 7,

17 2023). In another unpublished decision, filed on the last day of hearing in this appeal, the Court of

18 Appeals again affirmed the PCHB’s decision limiting the scope of Carey’s testimony. Sound Action

19 v. Pollution Control Hr’gs Bd., No. 57308-3-II, 2023 Wash. App. LEXIS 909, at *22 (Ct. App.

20 May 9, 2023) (“Gerlach”). In Gerlach, the Court of Appeals found that the PCHB had “examined

21 each factor from ER 702 as it related to Carey’s qualifications—scientific knowledge, skill,

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

32

1 experience, training, and education.” Gerlach, Wash. App. LEXIS 909 at *20. The PCHB’s “order

2 further explained that Carey’s assertion that she had relevant training was not supported by any

3 certification or other proof of formal training and, regarding education, she did not have a college

4 degree or other degree in the sciences.” Id. at *20-21. The Court of Appeals concluded that Sound

5 Action had not shown that the PCHB “abused its discretion in limiting Carey’s expert testimony,

6 and not qualifying her as an expert on biology, and not allowing her to testify regarding the

7 ecological impacts of the Gerlach project.” Id. at *22.

8 58.

9 At the hearing the Board received additional foundational testimony from Carey, who was

10 subject to voir dire. The Presiding Officer granted the motion in limine to exclude her testimony on

11 ecological processes and functions as not meeting ER 702 requirements. Oral Ruling at 130-31.

12 The Presiding Officer noted that Carey does not have formal education, training, or peer reviewed

13 scientific publications in this subject. Id. at 130-32. Furthermore, the Presiding Officer explained

14 that Carey’s testimony as an expert in biology had been excluded in Gerlach and found that no

15 significant additional support had been provided since then that would justify a different result. Id.

16 at 131; see also Gerlach, at *20-22. Carey was allowed to testify as a lay witness on other topics,

17 such as whale sightings.

18 Whale Sightings

19 59.

20 The parties dispute the extent to which whales are present at the Project site or its vicinity,

21 such that the Project would potentially affect them. Several witnesses testified regarding the Project

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

33

1 site and its surrounding areas without precisely defining the terms. See, e.g., Carey Testimony at

2 213-14. For clarity and consistency, the Board finds that the “Project site” is the 9.6-acre area

3 referenced in the Notice of Application. See Ex. RKC4, p. 0001; Spranger Testimony at 870. The

4 Board finds that “Project vicinity” encompasses the Project site as well as a small area on all sides

5 surrounding the Project site.

6 Carey testified about sightings of whales at or around the Project, and introduced photos

7 and videos of whales, including SRKW. Carey Testimony at 213-25; Exs. P16, P17, P18. However,

8 the evidence offered at hearing does not establish the location of the whales depicted in the exhibits.

9 For example, Carey asserted that a photo showed a whale traveling into the Project site based on

10 her description that a building in the photo “generally is along” the southern line of the Project site.

11 Carey Testimony at 213; Ex. P16, p. 1. It was unclear from the photos, however, how near the whale

12 was to the building and the Project site. See Ex. P16, p. 1. Carey testified as to another photo that

13 she knew it showed whales at the Project site because it was sent to her from someone on the water

14 monitoring the whales, without further explanation or support to demonstrate that it in fact showed

15 whales at the Project site. See Carey Testimony at 219; Ex. P16, p. 11. The Board finds that neither

16 Carey’s testimony nor the photos and videos conclusively establish that whales depicted in the

17 exhibits were in the Project site or Project vicinity.

18 Carey also testified regarding her own observation of whales in or around the Project site.

19 She stated that she has seen Bigg’s killer whales “in the vicinity of the site,” that she has

20 “[f]requently” observed humpbacks at the site, and that it is “fairly common” to see SRKW spend

21 “a bit of time in that area.” Carey Testimony at 226-28. The Board finds that Carey’s testimony

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

34

1 regarding her personal observations—which does not specify either location or frequency of whale

2 sightings beyond general terms—does not conclusively establish that whales were at either the

3 Project site or Project vicinity.

4 60.

5 Carey also presented estimates of whales in the Project area, based on reported whale

6 sightings. Carey Testimony at 236-47; Exs. P8, pp. 5-7 (Carey Summary), P10, P11, P12. To

7 prepare the estimates, Carey compared and correlated sighting data from the Whale Museum with

8 sighting reports from the Orca Network. Carey Testimony at 243. The sighting data from the Whale

9 Museum is broken down into grids, meaning that a whale reported in any of several grids adjacent

10 to the Project site possibly would have been within the actual vicinity of the Project. Id. at 240-41;

11 Ex. P8, pp. 3-4. In a written report, Carey explained that the Project site is located at the nexus of

12 three grids: 418, 420, and 422. Id. Accordingly, Carey included sightings from all three grids in

13 estimating the number of days whales were seen around the Project site. Id., p. 3. Carey explained

14 that she cross-referenced the Whale Museum data with other data and information “as well as with

15 personal observation information to determine a more precise location.” Id., p. 4. On cross-

16 examination Carey testified that the Whale Museum data contained 25 to 30 errors including dates

17 and type of whale identified that she corrected. Carey Testimony at 369. Per Carey’s calculations,

18 SRKW were seen in the Project area between two and eight days per year from 2014 to 2022.

19 Ex. P8, p. 5. Carey estimated that Bigg’s killer whales were seen around the Project site between

20 eight and 32 days per year and that humpback whales were seen between one and 88 times per year.

21 Id., pp. 6-7.

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

35

1 61.

2 Sound Action also called Alisa Lemire Brooks, who has been the whale sighting network

3 coordinator for the Orca Network since 2015. Brooks Testimony at 152, 156; Ex. P62 (Brooks

4 Resume). Orca Network collects reports from researchers, naturalists, trained volunteers, and

5 members of the public who observe orcas, humpbacks, and other whales in the Puget Sound. Brooks

6 Testimony at 153-54. Brooks provided expert testimony on whale presence and sightings in the

7 Salish Sea. Brooks Testimony at 161.

8 62.

9 The Orca Network collects data from a variety of sources, including emails, phone calls,

10 and social media. Brooks Testimony at 164. Each report is documented and then compiled into a

11 spreadsheet by one of the Orca Network’s board members. Id.; Ex. P86. The Orca Network also

12 collaborates on a whale alert app, which collects reports of whale sightings and records them on a

13 map. Brooks Testimony at 167; Ex. P13. Brooks testified that the whale alert map reflected whale

14 sightings in the vicinity of the Project site. Brooks Testimony at 171. Brooks also personally

15 observed orcas and other whales in the vicinity of the project along the southwest corner of Vashon

16 Island. Id. Based on her observations, Brooks would expect SRKW, Bigg’s killer whales, and

17 humpback whales to spend time in the Project site. Id. at 173, 180, 182.

18 63.

19 Brooks has not been to the Project site. Id. at 190-91. On cross examination, she

20 acknowledged that she cannot say that she observed whales in the actual Project site (as opposed to

21 the vicinity of the site) because she did not know about the Project when she observed whales in

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

36

1 the area. Id. at 191-92. According to Brooks, she had seen whales foraging within as close as 50 or

2 100 yards to the Project site. Id. at 192. She estimated that she had observed SRKW foraging in the

3 area of the Project site around six times and humpbacks around three times. Id. at 192-93. When

4 she observed whales in the area, she was either on a ferry approximately one-half to one mile away

5 from the Project site or on a shoreline approximately two miles from the Project site. Id. at 191.

6 64.

7 Dr. David Bain, the chief scientist for Orca Conservancy, also testified in support of Sound

8 Action. Bain Testimony at 600. Bain has a PhD in biology from the University of California, Santa

9 Cruz, and completed postdoctoral fellowships at the University of California, Davis, and at

10 NOAA’s national mammal laboratory. Id.; Ex. P59 (Bain CV). Among other positions related to

11 marine mammal research and observation, Bain was also a scientist for the Marine World

12 Foundation and worked for approximately 20 years as a contractor for NOAA. See Bain Testimony

13 at 600-03. Bain has also authored publications on marine mammal issues. Id. at 603. Bain was

14 permitted to testify as an expert on whale biology, behavior, and risks in the Salish Sea and beyond.

15 Id.; see also Ex. P21. Bain sits on the board for Sound Action. Bain Testimony at 607.

16 65.

17 Bain provided evidence regarding whale sightings. Bain testified regarding a peer-reviewed

18 scientific paper from 1990, which reflected humpback whale sightings in 1988. Bain Testimony at

19 617-18; Ex. P27. Based on a figure in the report that depicts humpback whale sightings as “dots”

20 on a low detail map (scale of 1 inch representing 10 kilometers), Bain testified that two of the “dots”

21 were in or just outside of the Project site. Bain Testimony at 619; P27 at 46 (Fig. 1). Bain had not

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

37

1 looked for more recent literature. Bain Testimony at 620. In his report, Bain also cited an NMFS

2 report from 2008, which reflects 26-100 SRKW sightings in or around the vicinity of the Project.

3 Ex. P21, p. 6. Bain’s report does not indicate the period over which the SRKW sightings were

4 reported. See Ex. P21, p. 6.

5 66.

6 Bain acknowledged that many of the whale sighting reports from the Orca Network do not

7 give an exact location of where a whale was located. Bain Testimony at 722. Moreover, even as to

8 sightings where a location is provided, uncertainty arises from how individuals perceive and

9 describe the location of whales. If a whale is reported to be “halfway across the channel,” for

10 example, it is uncertain how far offshore the whale is located and whether it was straight ahead

11 from the observer or not. Id. at 725. Bain testified that such sightings do indicate that a whale is

12 “somewhere between Tacoma and the south end of Vashon Island.” Id.

13 67.

14 Bain testified that humpback whales are likely to be found at the Project site from early

15 spring into late fall, although it is possible they will be seen in the area year round. Id. at 628. Bain

16 would expect to see humpback whales inshore of the Project site. Id. at 629. Bain also testified

17 regarding Bigg’s killer whales, opining that he would expect to see them at the Project site any time

18 of year. Id. at 630. Bain has not personally seen SRKW forage at the Project site. Id. at 778. Bain

19 testified about SRKW, stating that they circumnavigate Vashon Island fairly regularly over the

20 winter. Id. at 630-31.

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

38

1 68.

2 Cziesla testified on behalf of Spranger regarding whales. He discussed whale sightings in

3 the area and challenged the reliability and usefulness of the sighting analysis proffered by Sound

4 Action’s witnesses. Cziesla Testimony at 1366; Ex. RS28 (Cziesla CV). For the past 25 years,

5 Cziesla has been conducting research, collecting data, and analyzing projects, primarily in the

6 Northwest. Cziesla Testimony at 1367. Cziesla’s focus areas include marine and estuarian ecology,

7 fisheries biology, habitat classification, nearshore oceanography and circulation, marine mammals,

8 and shellfish. Id.. Cziesla first became involved with the Project when Spranger reached out to

9 Confluence for assistance during the permitting process. Id. at 1374.

10 69.

11 Cziesla relied on a study of SRKW sightings from 1976 to 2014, which was published in

12 2018. Id. at 1393-94; Ex. RS12 (Olson JK, et al., Sightings of southern resident killer whales in the

13 Salish Sea 1976–2014: the importance of a long-term opportunistic dataset. Endang Species Res

14 37:105-118 (2018)). According to the 2018 study, Cziesla explained that the Project is within an

15 area that is in the lowest group of sighting frequencies, supporting the conclusion that the Project

16 site does not represent a frequent use area for SRKWs. Ex. RS60, pp. 3-4.

17 70.

18 In his initial analyses, Cziesla avoided using sighting data relied upon by Sound Action’s

19 witnesses because they consist of opportunistic observations that are not corrected for sampling

20 bias, meaning that they are collected in such a way that there is a lower or higher probability of

21 detection under the methods being used. Cziesla Testimony at 1394-95. In particular, Cziesla

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

39

1 testified that the data would show a higher incidence of whale presence where there are overlooks

2 or viewpoints to observe whales and a higher bias for daytime versus nighttime hours. Id. at 1395.

3 Ferry routes also heavily influence the datasets, according to Cziesla, because ferry captains are

4 obligated to report every whale sighting, ferries provide an effective platform for viewing whales,

5 and all the passengers are observers. Id. at 1395-96.

6 71.

7 Furthermore, Cziesla criticized Carey’s use of the Whale Museum data for all three separate

8 grids in the vicinity of the Project—grid numbers 418, 420, and 422. According to Cziesla, the

9 majority of grid 420 is away from the Project area, and the sighting frequency data are biased by a

10 large population of potential observers from Point Defiance, Tacoma, and ferry passengers.

11 Ex. RS60, pp. 1-2 (Cziesla Report); see also P8, p. 4 (Carey Report). Even using Carey’s data and

12 analysis, however, Cziesla concluded that the 2-8 sighting days of SRKW per year in grid numbers

13 418, 420, and 422 is relatively low compared with other areas such as Elliott Bay and the

14 Edmonds/Kingston area, which have up to 34 and 37 sighting days respectively. Ex. RS60, p. 2.

15 72.

16 Spranger also testified regarding his own observations while at the Project site. He visits the

17 Project site via boat about 3-5 times per week, totaling approximately 200 to 250 visits. Spranger

18 Testimony at 868-70. In his visits, he has never seen any whales within the Project site (i.e., within

19 the footprint of the approximately 10-acre site). Id. at 870.

20

21

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

40

1 73.

2 The Board finds and concludes that King County did not err in concluding that the proposed

3 farm is located in an area that is not known as a particularly high use area for marine mammals as

4 compared to other sites in Puget Sound. RKC1 p.2; RKC10 p. 2. The Board finds Cziesla’s and

5 Spranger’s testimony regarding the frequency of whale sightings in or around the area is generally

6 more reliable than the evidence presented by Sound Action’s witnesses. Cziesla’s opinion that the

7 Project site does not represent a frequent use area for SRKW is supported by a 2018 published study

8 of whale sightings, which attempted to correct for sampling bias. Cziesla Testimony at 1397-98;

9 Ex. RS60, pp. 3-4. The Board also places more weight to Spranger’s testimony as it was based on

10 frequent firsthand observation at the Project site. In contrast, the opinions of Sound Action’s

11 witnesses regarding whale sighting data were not corrected for sampling bias and included data

12 from areas well beyond the Project site.

13 Whale Behavior

14 74.

15 The parties also disputed the behaviors that whales engage in at the Project site that would

16 either be limited by the Project or would expose them to risk if the Project is built. Monika Wieland

17 Shields, director of the Orca Behavior Institute, testified for Sound Action as an expert on whale

18 presence, behavior, and the Project’s potential effects on whales. Shields Testimony at 534-37; Ex.

19 P61 (Shields CV). Orca Institute’s mission is to conduct noninvasive behavioral and acoustic

20 research on Bigg’s killer whales and SRKW in the Salish Sea. Shields Testimony at 535. Shields’s

21 responsibilities at the Orca Institute include implementing the group’s research projects, analyzing

FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ORDER

SHB No. 23-002

41

1 data, and publishing research. Shields Testimony at 535. She has a degree in biology with a focus

2 in animal behavior. Id. at 536. Shields also has more than 20 years of experience in the San Juan

3 Islands. Id.; Ex. P61.

4 75.

5 Shields testified that she would expect SRKW to use the Project site for foraging or

6 traveling. Shields Testimony at 547-48. She stated she would expect to see SRKW in the area

7 primarily from September through January, for a total of about one-to-two weeks. Id. at 548. The

8 amount of time humpbacks spend in the vicinity varies, she stated, and most sightings occur

9 between May and December. Id. at 565-66.

10 76.

11 Shields also testified that SRKW, Bigg’s killer whales, and humpback whales all engage in

12 a behavior called “kelping,” during which they swim through kelp beds and interact with the kelp.

13 See Id. at 549-53; Ex. P36. Shields discussed photos she had taken of whales kelping. Shields

14 Testimony at 549-53; Ex. P36. Although the photos show whales interacting primarily with bull

15 kelp, Shields testified that she had seen whales interacting with a variety of kelp species and that

16 she did not think orcas would interact differently with the sugar kelp to be grown at the Project site.