Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Diversity Lost - Are All Holarctic Large Mammal spe-WT - Summaries

Diversity Lost - Are All Holarctic Large Mammal spe-WT - Summaries

Uploaded by

Kookie JunOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Diversity Lost - Are All Holarctic Large Mammal spe-WT - Summaries

Diversity Lost - Are All Holarctic Large Mammal spe-WT - Summaries

Uploaded by

Kookie JunCopyright:

Available Formats

Diversity lost: are all Holarctic large mammal

species just relict populations?

Abstract

Population genetic analyses of Eurasian wolves suggest that a major genetic

turnover took place after the Pleistocene.

Unraveling the population history of a species is tricky business. The only archives

left are the fossil record and the traces that population processes have left in the

species' gene pool, but both are ultimately unsatisfactory when it comes to

addressing how organisms deal with change.

The analysis of ancient DNA has brought together two fields of research, allowing us

to compare current and past populations, with a timescale of around 50,000 to

100,000 years. The megafaunal extinctions that began at the end of the Pleistocene

are well studied.

Ancient DNA can help us understand how species that survived the Late Pleistocene

extinctions experienced population loss or replacement.

A study on Eurasian wolves found that the genetic diversity of the species was much

higher during the Pleistocene and Holocene than it is today, and that the wolf

population that disappeared from North America preyed on Pleistocene megafaunal

species that became rare at the beginning of the Holocene.

Diversity losses inferred from ancient DNA

Ancient DNA analyses have revealed a lot about changes in the genetic makeup of

populations over time. Modern DNA analyses miss events such as haplogroup

extinctions.

In 2002, the first study was published on brown bears from Alaska and Canada. This

study demonstrated that brown bears suffered a haplogroup extinction event around

35,000 years ago, and that European brown bears suffered a substantial loss of

genetic diversity before and during the Holocene.

Ecological factors in diversity loss

We know very little about the potential factors that drive reduction in genetic diversity

for the extant large mammals of the northern continents, and the causes of

megafaunal extinctions at the end of the Pleistocene are also still unresolved. These

data suggest that Pleistocene wolves preyed on megafaunal species, specifically

horses and large bovids, and that the disappearance of their prey caused the

extinction of wolf haplogroup 1 in North America.

Although wolves are usually highly mobile, ecological factors, including

specializations on certain prey, seem to play an important role in shaping the

geographical structure of genetic diversity in extant wolf populations.

Losing ecomorphological and genetic diversity

Carnivores have lost a large part of their genetic diversity, and bison and horses

have also become homogeneous. However, a recent ancient DNA study suggests

that the morphological range of extinct horse species was much larger than has

been assumed.

Extant species are depleted in both genetic and ecomorphological diversity when

compared with their Pleistocene counterparts, but this is not surprising given that the

last glaciation ended 10,000 years ago.

Biodiversity during the Pleistocene, today and in the future

Although we have undoubtedly lost a lot of biodiversity, some surviving species may

also have lower genetic diversity than they had during the Pleistocene. Yet despite

this, many species were extremely successful during the Holocene.

Converting this observation into conservation policy requires a more extensive

discussion between paleontologists, conservation biologists and ancient DNA

specialists. Perhaps the best way to preserve biodiversity is to encourage species to

colonize as broad a habitat as naturally possible.

You might also like

- Agency AgreementDocument10 pagesAgency AgreementbinoyjmatNo ratings yet

- Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives & Evolutionary HistoryFrom EverandDogs: Their Fossil Relatives & Evolutionary HistoryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- Challenges Faced by Entrepreneurs of Sari-Sari Stores in Kabankalan CityDocument40 pagesChallenges Faced by Entrepreneurs of Sari-Sari Stores in Kabankalan CityAyeng 1502100% (2)

- Paul S. Martin - Prehistoric Overkill. The Global ModelDocument52 pagesPaul S. Martin - Prehistoric Overkill. The Global ModelDarcio Rundvalt100% (6)

- How Carnivorous Are We The Implication For Protein ConsumptionDocument16 pagesHow Carnivorous Are We The Implication For Protein Consumptionapi-235117584No ratings yet

- Module 2 (Physics)Document4 pagesModule 2 (Physics)Miguel Oliveira100% (1)

- Evolution of DogsDocument2 pagesEvolution of DogsKristine Angelique PinuelaNo ratings yet

- Informe Millaray - QuintelaDocument5 pagesInforme Millaray - QuintelamillarayNo ratings yet

- ICAZ2023 Abstracts Final V4Document249 pagesICAZ2023 Abstracts Final V4Goran TomacNo ratings yet

- Wiki Origin of The Domestic DogDocument38 pagesWiki Origin of The Domestic DogDe-hai CayolemNo ratings yet

- An DogDocument11 pagesAn DogJospel GadNo ratings yet

- Cat Domestication & Breed Development L. A. LyonsDocument5 pagesCat Domestication & Breed Development L. A. LyonsNinaBegovićNo ratings yet

- Francis, Richard C - Domesticated - Evolution in A Man-Made World-W. W. Norton & Company (2015)Document566 pagesFrancis, Richard C - Domesticated - Evolution in A Man-Made World-W. W. Norton & Company (2015)ovidiu1965No ratings yet

- Top Dogs - Wolf Domestication and wealth-WT - SummariesDocument2 pagesTop Dogs - Wolf Domestication and wealth-WT - SummariesKookie JunNo ratings yet

- Wolf - WikipediaDocument187 pagesWolf - WikipediaOrigami toturial by AbhijeetNo ratings yet

- Homo HobbitDocument4 pagesHomo HobbitAndrew JonesNo ratings yet

- Science Has Been Working in Order To Find AnswersDocument6 pagesScience Has Been Working in Order To Find Answersapi-219303558No ratings yet

- Extinct AnimalsDocument13 pagesExtinct AnimalsIyliahNo ratings yet

- Top Dogs: Wolf Domestication and Wealth: OpinionDocument6 pagesTop Dogs: Wolf Domestication and Wealth: Opiniongryphn22No ratings yet

- The Evolution of DogsDocument6 pagesThe Evolution of DogsdorynemoNo ratings yet

- Tpo 04Document13 pagesTpo 04马英九No ratings yet

- Rethinking Dog DomesticationDocument6 pagesRethinking Dog DomesticationValeria Molina CanoNo ratings yet

- Canids of the World: Wolves, Wild Dogs, Foxes, Jackals, Coyotes, and Their RelativesFrom EverandCanids of the World: Wolves, Wild Dogs, Foxes, Jackals, Coyotes, and Their RelativesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Process of DomesticationDocument7 pagesThe Process of DomesticationNommandurNo ratings yet

- A History of Pig Domestication: New Ways of Exploring A Complex ProcessDocument10 pagesA History of Pig Domestication: New Ways of Exploring A Complex ProcessMaría EscobarNo ratings yet

- Pnas 2008 Vol 105 No 22 p11597-11604 - Domestication and Early Agriculture in The Mediteranean Basin - Origins, Diffusion and ImpactDocument8 pagesPnas 2008 Vol 105 No 22 p11597-11604 - Domestication and Early Agriculture in The Mediteranean Basin - Origins, Diffusion and ImpactNKMS:)No ratings yet

- How the Dog Became the Dog: From Wolves to Our Best FriendsFrom EverandHow the Dog Became the Dog: From Wolves to Our Best FriendsRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (8)

- Paleopathology and Paleomedicine: An Introduction.Document3 pagesPaleopathology and Paleomedicine: An Introduction.VALIDATE066No ratings yet

- Pattern of Speciation of Felidae Zia Czarina A. GarciaDocument14 pagesPattern of Speciation of Felidae Zia Czarina A. GarciaSedsed QuematonNo ratings yet

- Domestication of DogsDocument17 pagesDomestication of DogsMarzthNo ratings yet

- Felids and Hyenas of the World: Wildcats, Panthers, Lynx, Pumas, Ocelots, Caracals, and RelativesFrom EverandFelids and Hyenas of the World: Wildcats, Panthers, Lynx, Pumas, Ocelots, Caracals, and RelativesNo ratings yet

- A Joosr Guide to... The Sixth Extinction by Elizabeth Kolbert: An Unnatural HistoryFrom EverandA Joosr Guide to... The Sixth Extinction by Elizabeth Kolbert: An Unnatural HistoryNo ratings yet

- The Draft Genome of Extinct European Aurochs and Its Implications For De-Extinction Mikkel-Holger S. Sinding, and M. Thomas P. GilbertDocument9 pagesThe Draft Genome of Extinct European Aurochs and Its Implications For De-Extinction Mikkel-Holger S. Sinding, and M. Thomas P. GilbertWyatt WilmotNo ratings yet

- Domestication of The HorseDocument11 pagesDomestication of The HorseMuhammad Farrukh Hafeez100% (1)

- Ancient Mitochondrial DNA From Malaysian Hair Samples - Some Indications of Southeast Asian Population Movements - P.Z.2006Document14 pagesAncient Mitochondrial DNA From Malaysian Hair Samples - Some Indications of Southeast Asian Population Movements - P.Z.2006yazna64No ratings yet

- Germonpre Et Al. Palaeolithic Dog-LibreDocument18 pagesGermonpre Et Al. Palaeolithic Dog-LibreDaniel LockeNo ratings yet

- Lewis 2009 Dogs ReviewDocument4 pagesLewis 2009 Dogs ReviewFelipe HenriqueNo ratings yet

- Dog Evolution - Their Domestication History.Document7 pagesDog Evolution - Their Domestication History.SowmitraNo ratings yet

- DogsDocument6 pagesDogsKaranjiit Singh100% (1)

- Animal EvolutionDocument10 pagesAnimal EvolutionStace CeeNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Kelompok 900071Document7 pagesJurnal Kelompok 900071Tito Gazza AryatnoNo ratings yet

- Mammoth KillDocument2 pagesMammoth KillLê Thị Thanh ThảoNo ratings yet

- Janicki Benjamin Paper 3Document5 pagesJanicki Benjamin Paper 3api-255513478No ratings yet

- About HyenaDocument24 pagesAbout HyenaRiswan Hanafyah Harahap0% (1)

- Article Fossil AnimalsDocument4 pagesArticle Fossil AnimalsmozartNo ratings yet

- Wayne 2012 Evolutionarygenomicsofdogdomestication-1Document17 pagesWayne 2012 Evolutionarygenomicsofdogdomestication-1Карина ШевчукNo ratings yet

- Once and Future Giants - What Ice Age Extinctions Tell Us About The Fate of Earth's Largest AnimalsDocument274 pagesOnce and Future Giants - What Ice Age Extinctions Tell Us About The Fate of Earth's Largest AnimalsHoàng Anh PhươngNo ratings yet

- Exploiters & Exploited W1 - WolvesDocument3 pagesExploiters & Exploited W1 - WolvesMonica OrtizNo ratings yet

- Salis Bears LionsDocument15 pagesSalis Bears LionsdrrossbarnettNo ratings yet

- 2001 Speth and Tchernov Neandertal HuntiDocument22 pages2001 Speth and Tchernov Neandertal HuntiAnaLiggiaSamayoaNo ratings yet

- DomesticationDocument4 pagesDomesticationDeniseNo ratings yet

- Science Evolution Project-Maned WolfDocument12 pagesScience Evolution Project-Maned Wolfapi-257094154No ratings yet

- Mammoth Kill 2: Reading Passage 1Document7 pagesMammoth Kill 2: Reading Passage 1Quan NguyenNo ratings yet

- Importance of CowDocument3 pagesImportance of CowthanosNo ratings yet

- Davis 2005-Zasto Je Doslo Do Domestikacije-LevantDocument9 pagesDavis 2005-Zasto Je Doslo Do Domestikacije-LevantAleksandar SalamonNo ratings yet

- Breaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies: Animals as Material Culture in the Middle AgesFrom EverandBreaking and Shaping Beastly Bodies: Animals as Material Culture in the Middle AgesNo ratings yet

- Panthera Leo Spelaea: Physical CharacteristicsDocument3 pagesPanthera Leo Spelaea: Physical CharacteristicsDorina DoryNo ratings yet

- Farmers and Their Languages SciARTDocument7 pagesFarmers and Their Languages SciARTgeorgeperkinsNo ratings yet

- Project in ScienceDocument14 pagesProject in ScienceGegeyz1028No ratings yet

- Limbs in Whales and Limblessness in Other VertebratesDocument14 pagesLimbs in Whales and Limblessness in Other VertebratesJay LeeNo ratings yet

- Gene Expression NeighborhoodsDocument1 pageGene Expression NeighborhoodsKookie JunNo ratings yet

- Small-Molecule Modulators of Hedgehog SignalingDocument7 pagesSmall-Molecule Modulators of Hedgehog SignalingKookie JunNo ratings yet

- Roughing Up Smoothened - Chemical Modulators of HedDocument2 pagesRoughing Up Smoothened - Chemical Modulators of HedKookie JunNo ratings yet

- Evidence For Large Domains of Similarly ExpressedDocument3 pagesEvidence For Large Domains of Similarly ExpressedKookie JunNo ratings yet

- A Modern Circadian Clock in The Common Angiosperm - WT - SummariesDocument2 pagesA Modern Circadian Clock in The Common Angiosperm - WT - SummariesKookie JunNo ratings yet

- The Mathematics of Sexual AttractionDocument2 pagesThe Mathematics of Sexual AttractionKookie JunNo ratings yet

- Hybridization and Speciation in Angiosperms - arole-WT - SummariesDocument2 pagesHybridization and Speciation in Angiosperms - arole-WT - SummariesKookie JunNo ratings yet

- Endothelial Adherens Junctions and The Actin cytos-WT - SummariesDocument1 pageEndothelial Adherens Junctions and The Actin cytos-WT - SummariesKookie JunNo ratings yet

- Robust and Specific Inhibition of microRNAs in Cae-WT - SummariesDocument1 pageRobust and Specific Inhibition of microRNAs in Cae-WT - SummariesKookie JunNo ratings yet

- Evolution Underground - Shedding Light On The diver-WT - SummariesDocument2 pagesEvolution Underground - Shedding Light On The diver-WT - SummariesKookie JunNo ratings yet

- Scale-Eating Cichlids - From Hand (Ed) To mouth-WT - SummariesDocument2 pagesScale-Eating Cichlids - From Hand (Ed) To mouth-WT - SummariesKookie JunNo ratings yet

- DiureticsDocument17 pagesDiureticsKookie JunNo ratings yet

- Vaping-Induced Acute Epiglottitis - A Case Report-WT - SummariesDocument2 pagesVaping-Induced Acute Epiglottitis - A Case Report-WT - SummariesKookie JunNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 - Object-Oriented Database ModelDocument9 pagesChapter 5 - Object-Oriented Database Modelyoseffisseha12No ratings yet

- Encoder Serie Ria-40Document6 pagesEncoder Serie Ria-40Carlos NigmannNo ratings yet

- Hendricks, David W - Fundamentals of Water Treatment Unit Processes - Physical, Chemical, and Biological-CRC Press (2011)Document930 pagesHendricks, David W - Fundamentals of Water Treatment Unit Processes - Physical, Chemical, and Biological-CRC Press (2011)Héctor RomeroNo ratings yet

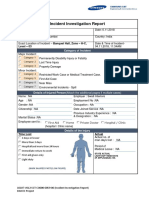

- Incident Investigation Report - Fire Incedent - 04-11-2018 Swati InteriorsDocument4 pagesIncident Investigation Report - Fire Incedent - 04-11-2018 Swati InteriorsMobin Thomas AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Data Presentation and AnalysisDocument105 pagesQuantitative Data Presentation and AnalysisAljon Andol OrtegaNo ratings yet

- AOF - Orcs v2.50Document2 pagesAOF - Orcs v2.50Emilio Domingo RodrigoNo ratings yet

- Delcam - PowerINSPECT 2017 WhatsNew CNC RU - 2016Document40 pagesDelcam - PowerINSPECT 2017 WhatsNew CNC RU - 2016phạm minh hùngNo ratings yet

- Illinois State Board of Education: General InformationDocument40 pagesIllinois State Board of Education: General InformationLeslie AtkinsonNo ratings yet

- Ghirri - Redutores - Classificação - Um-Vs-Rev.20.06.06-Eng3Document35 pagesGhirri - Redutores - Classificação - Um-Vs-Rev.20.06.06-Eng3Jeferson DantasNo ratings yet

- UNIT-4 Key Distribution & ManagementDocument53 pagesUNIT-4 Key Distribution & ManagementBharath Kumar T VNo ratings yet

- InventoryrrgDocument31 pagesInventoryrrgPiyush KumarNo ratings yet

- Department of Applied Physics Applied Physics Question Bank Session - 2012-13Document4 pagesDepartment of Applied Physics Applied Physics Question Bank Session - 2012-13Sajid Ur RehmanNo ratings yet

- A Circle of DistortionDocument20 pagesA Circle of DistortionfinityNo ratings yet

- LOC Taxed Under ITADocument3 pagesLOC Taxed Under ITARizhatul AizatNo ratings yet

- Arithmetic MeansDocument8 pagesArithmetic MeansMargie Ballesteros ManzanoNo ratings yet

- Sms CollectionDocument95 pagesSms Collectionsaurabh jainNo ratings yet

- Evaluasi Manajemen Peserta Didik Di SMPN 50 PalembangDocument7 pagesEvaluasi Manajemen Peserta Didik Di SMPN 50 PalembangAngel GabrielNo ratings yet

- Social Media Changed The Nature of Indian Education SystemDocument9 pagesSocial Media Changed The Nature of Indian Education SystemHiteshNo ratings yet

- UTS 013 CaseStudies HasbahDigital v1.0 MEDocument2 pagesUTS 013 CaseStudies HasbahDigital v1.0 METhomas ThomasNo ratings yet

- Miles High Cycles Katherine Roland and John ConnorsDocument4 pagesMiles High Cycles Katherine Roland and John ConnorsvivekNo ratings yet

- DR - Nitish Kumar - CV ..Document6 pagesDR - Nitish Kumar - CV ..ABHISHEK SINGHNo ratings yet

- Configure Anyconnect 00Document22 pagesConfigure Anyconnect 00Ruben VillafaniNo ratings yet

- Hf7/Hf9 Front Axle Spare Parts Catalog: SinotrukDocument9 pagesHf7/Hf9 Front Axle Spare Parts Catalog: SinotrukSamuel WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Multiattribute Utility FunctionsDocument25 pagesMultiattribute Utility FunctionssilentNo ratings yet

- Carbohydrates Discussion Questions and AnswersDocument2 pagesCarbohydrates Discussion Questions and AnswerslolstudentNo ratings yet

- Accomplishment of ElectricianDocument17 pagesAccomplishment of ElectricianRichard Tañada RosalesNo ratings yet

- CHP 7 InventoryDocument48 pagesCHP 7 InventoryStacy MitchellNo ratings yet