Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Man's Quest and Madness - A Brief Analysis of Miguel de Cervantes' The Ingenious Hidalgo Don Quixote de La Mancha

A Man's Quest and Madness - A Brief Analysis of Miguel de Cervantes' The Ingenious Hidalgo Don Quixote de La Mancha

Uploaded by

John Mark ValenciaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Man's Quest and Madness - A Brief Analysis of Miguel de Cervantes' The Ingenious Hidalgo Don Quixote de La Mancha

A Man's Quest and Madness - A Brief Analysis of Miguel de Cervantes' The Ingenious Hidalgo Don Quixote de La Mancha

Uploaded by

John Mark ValenciaCopyright:

Available Formats

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

A Man’s Quest and Madness: A Brief Analysis of

Miguel De Cervantes’ the Ingenious Hidalgo Don

Quixote De La Mancha

John Mark F. Valencia

Introduction

Don Quixote also spelled Don Quijote, 17th-century Spanish literary character and

the protagonist of Miguel de Cervantes' novel Don Quixote. The book, which was originally

published in two parts in Spanish (1605, 1615), is about the eponymous would-be knight

errant, whose arrogance makes him the target of many practical jokes. The novel is

considered by literary historians to be one of the most important books of all time, and it is

often cited as the first modern novel. The character of Quixote became an archetype, and

the word quixotic, used to mean the impractical pursuit of idealistic goals, entered

common usage.

This paper discusses how Miguel De Cervantes’ Don Quixote made it as a world

literary masterpiece. Specifically, the author aims to highlight linguistic elements of the

novel such as linguistic poignancy, imagery, philosophical inquiry, syntactical fluidity and

1 John Mark F. Valencia

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

complexity, emotional evocation, and the plot. Hence, this also aims to shed light on issues

faced by the masterpiece, the novel’s contribution in the transformation of human identity

and its time relevance to present society.

Brief Biography of Miguel De Cervantes Saaverda

According to Lathrop (2011), Cervantes was born into a low-income family in a small

town near Madrid. His father was a surgeon and barber, and his mother was the daughter

of disgraced noblemen. Some academics believe he attended university in Salamanca or

Seville. He moved to Rome as a young man, where he immersed himself in Renaissance art

and literature. He enlisted in the Spanish navy in his early thirties, spending five years as a

soldier and another five years as a captive and slave in Algiers. He returned to Spain,

married a younger woman, and led a nomadic and impoverished life, frequently going

bankrupt and serving several prison sentences. Cervantes began publishing fiction and

plays in 1585, but it wasn't until the publication of Don Quixote in 1605, that he achieved

literary and financial success. He died in Madrid a decade later, shortly after the second

part of the story was published.

Plot Summary

Originally, the novel was written in two parts. Together, the translation of Tom

Lathrop's version of Don Quixote makes up 1040 pages. It is, however, merely impossible

to summarize all from his version. In this regard, the plot summary below was taken from

the Encyclopedia Britannica page online.

Part I

Alonso Quixano, a middle-aged skinny bachelor who enjoys chivalry romances, loses

his mind, and decides to become a brave knight. He takes the names Don Quixote de la

Mancha for himself, Rocinante for his bony horse, and Dulcinea for his beloved.

A rusty suit of armor is donned by Don Quixote before he embarks on his first sally

in a few days. He defends a young shepherd from his enraged master, wins a knighthood at

an inn that he mistook for a castle, and is beaten by some merchants who are unaware of

the rules of knight-errantry. He goes back to his hometown to heal.

The priest and the barber, two of Quixote's friends, decide to burn the majority of

his chivalry books while he is recovering from his wounds. They attribute this decision to

Quixote's recent insanity and injuries. Quixote believes that evil enchanters, who typically

plague knights errant, are responsible for this. He hires Sancho Panza, a peasant, to be his

squire, and the two of them set out for the second sally.

Sancho and Quixote encounter many fictitious foes along the way, including giants

who turn out to be windmills, enchanters who turn out to be irate muleteers, and

2 John Mark F. Valencia

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

kidnappers who turn out to be peaceful friars. Because of their bizarre and absurd ideas,

people everywhere ridicule them and beat them.

When they release some prisoners, they are showered with stones as a form of

gratitude. They interact with a variety of fascinating strangers, many of whom are engaged

in unhappy romantic relationships. They unintentionally assist several split-up couples by

attending the funeral of a man who committed suicide because of his love for a stunning

shepherdess. At a small inn, a large, colorful cast of characters gathers, and

miscommunications and reconciliations happen one after the other in a flash.

In an effort to cure Quixote's madness, the barber, and the priest disguise

themselves and drag him back to the village inside a wooden cage. He is bedridden and

depressed at the end of part one.

Part II

In the second part, Quixote is a month older and eager to embark on his third sally.

He learns from the student Carrasco that his exploits thus far have been chronicled in a

popular chivalry novel, which has made him and Sancho famous. Quixote and Sancho set

out for El Toboso a few days later to gain Dulcinea's blessing.

But neither knows where Dulcinea lives because there is no such person in real life -

only a peasant girl named Aldonza, who is nothing like the ethereal princess of Quixote's

imagination. To make up for this inconsistency, Sancho informs Quixote that a

rough-looking peasant girl they meet on the road is the enchanted Dulcinea. Quixote is

displeased to see his beloved take such an unusual form.

When they return to the road, Quixote fights the Knight of the Forest, who is actually

Carrasco in disguise, attempting to trick Quixote into returning to the village. Quixote

triumphs, and Carrasco retreats in shame. Quixote and Sancho Panza have a number of

adventures, including staying with a gentleman, attending a lavish wedding, and

investigating the Cave of Montesinos, where Quixote claims to have seen magical,

unbelievable sights.

They make friends with a Duke and Duchess who are fans of the first part of the

story. The Duke and Duchess lavishly welcome them, but they play numerous cruel tricks

on them. In one elaborate scenario, an "enchanter" tells Sancho that he must lash himself

thousands of times in order to disenchant Dulcinea.

When the Duke learns that Quixote has promised Sancho an island in exchange for

his services, he appoints Sancho as governor of a small town. He expects to humiliate the

illiterate, uneducated peasant, but Sancho proves to be a wise and gifted ruler. However,

after a week, Sancho grows tired of his difficult responsibilities and begins to miss his life as

Quixote's squire. He resigns and returns to his adventures with Quixote.

3 John Mark F. Valencia

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

The two friends keep meeting fascinating strangers. In Barcelona, they make friends

with a gallant captain of thieves and a wealthy gentleman. Quixote faces off against the

enigmatic Knight of the White Moon. Carrasco wins the battle this time and demands that

Quixote and Sancho return to the village as his prize. Quixote becomes increasingly

depressed as he loses hope of Dulcinea's disenchantment.

When they return to the village, Quixote falls gravely ill. One day, after a long sleep,

he declares that he has regained his sanity. He now despises knighthood and chivalry

romances. There is no longer a Don Quixote; instead, he is Alonso Quixano the Good. He

passed away soon after.

Miguel De Cervantes’ Linguistic Poignancy on Don Quixote

Poets recognize that each word has the potential to improve the vibrancy of a poem.

Because poems have fewer words per page, prose writers have much less linguistic

freedom than prose writers. Good prose writers, on the other hand, understand that even

if their documents contain thousands more words, each one represents an opportunity to

boost the text's vibrancy. Every written masterpiece, regardless of genre, is a deliberate

combination of carefully selected words (Huff, 2018).

It is important to note that Miguel De Cervantes’ Don Quixote is a novel written in

the 17th century in Spanish language. In that regard, the need to translate this masterpiece

to another language became an enormous demand a couple of centuries after its

publication. However, these have resulted in different variations on passages of the text

(Thacker, 2015). For instance, many historians may consider that the version of Thomas

Shelton of Part I that appeared in 1612, just a few years later the publication of Cervantes

was highly accurate. However, linguists argued that Shelton had limited tools at his disposal

and relied upon his good knowledge of Spanish, basic dictionaries, his general cultural

awareness, and his wits. Yet, sufficient study and careful analysis of different translators

have created a more accurate version of the novel. Among those critically acclaimed

translations of today were Harper Perennial, Burton Raffel, Edith Grossman (the first

woman to translate the work), Tom Lathrop and James H. Montgomery.

The translation of a novel into another language inevitably impacts its linguistic

poignancy. While the essence of the story and its emotional depth can still be conveyed,

the specific nuances, wordplay, cultural references, and stylistic elements that contribute to

the original work's linguistic beauty may be altered or lost. The intricate dance of words,

the rhythm, and the cadence of the prose, which contribute to the novel's aesthetic impact,

are often difficult to replicate in a different language (Predmore, 1967). Translators face the

daunting task of finding equivalent expressions and structures that can capture the

essence of the original text, while also considering the target language's linguistic and

cultural context. Despite their skill, some linguistic subtleties may inevitably be

compromised, which may affect the overall poignancy of the translated work. Nevertheless,

4 John Mark F. Valencia

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

a skillful translator can still create a compelling and emotionally resonant narrative,

ensuring that the heart of the story shines through in the new language (Thacker, 2015).

Nevertheless, despite that challenging task faced by different translators and

historians and their various versions of the novel, it can be agreed that among those

versions, there are similar notable features in terms of linguistic poignancy of translated

text. However, in this constructive criticism, the author uses the version of Tom Lathrop of

Signet Classics to highlight the said linguistic features.

Setting that aside, from the said version, and even other versions, it can be assumed

and agreed that Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote is a novel that is rich in linguistic

poignancy. Primarily, despite that it was translated in American English, the language used

in the novel is still a reflection of the time period in which it was written, and the Cervantes

use of various literary techniques adds depth and nuance to the characters and their

relationships are evident.

One of the most significant examples of linguistic poignancy in Don Quixote is the

use of irony. Throughout the novel, Cervantes employs this to highlight the absurdity of

Quixote's actions and the world in which he lives. For example, Quixote believes himself to

be a Noble Knight Errant, but in reality, he is a delusional old man who is out of touch with

reality. Cervantes also uses satire to criticize the society of his time. The novel is a scathing

critique of the Spanish aristocracy and the feudal system.

Cervantes' use of allusion adds depth and nuance to the novel. For example, he

alludes to the epic poems of the past, such as the Odyssey and the Aeneid, to create a

sense of grandeur and heroic myths around Quixote's quest.

The utilization of metaphor to create vivid and evocative descriptions of the world in

which his characters inhabit. For example, he describes the windmills that Quixote

mistakes for giants as "long arms" that "whirl around in the air." This metaphor helps to

create a sense of the danger and drama of Quixote's battle with the windmills. Meanwhile,

the novel's dialogue is an important aspect of the novel’s linguistic poignance. Cervantes

creates distinct voices for each of his characters, from the bombastic and grandiose

speeches of Quixote to the more down-to-earth conversations of Sancho Panza. This

creates a sense of realism and authenticity to the characters and their relationships.

Perhaps the evident skill of Cervantes' use of linguistic poignancy in the novel can be

primarily cited in the names of the characters. Only the names of the knights, heroes, and

giants from the hidalgo's books are given to specific people in the opening chapter, with

the exception of the village barber. And the main action of the opening situation is

constituted by processes of naming, of his horse, his lady, and himself (Brink, 1998).

Cervantes named his main characters using a variety of naming conventions and

techniques. For instance, the protagonist's name, Don Quixote, is a pseudonym that he

chooses for himself, the real name is Alonso Quijano, but he changes it to reflect his new

5 John Mark F. Valencia

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

identity as a chivalrous knight. "De la Mancha" refers to the region of Spain where Quixote

lives.

Moreover, Don Quixote's loyal squire is named Sancho Panza. "Sancho" is a

common Spanish name, and "Panza" means "belly" in Spanish, possibly alluding to

Sancho's overweight figure. Dulcinea del Toboso, Don Quixote's love interest, means

"sweet" or "gentle" in Spanish, whereas “Del Toboso" refers to her hometown. Additionally,

Don Quixote's horse is named Rocinante, which means "old nag" or "workhorse" in

Spanish. The name reflects the horse's humble origins and Quixote's delusions of

grandness.

However, in the case of characters “Duke and Duchess”, they are not named but are

instead referred to by their titles. This reinforces their position of authority and their status

as representatives of the ruling class. Cervantes' naming conventions in Don Quixote reflect

the themes and motifs of the novel, such as the contrast between reality and fantasy, the

nature of identity and self-invention, and the critique of the Spanish aristocracy.

The linguistic poignancy of Don Quixote lies in its intricate wordplay, rhetorical

devices, and the interplay between elevated and colloquial language, which reflect the dual

nature of its protagonist's imagination and the real world.

Miguel De Cervantes’ Use of Imagery

Imagery is the foundation of imagination. Imagery is the product of the author’s

observation and linguistic transformation from memory to page (Huff, 2018). Miguel de

Cervantes uses a wide range of imagery in Don Quixote to vividly describe the characters

and settings, as well as to convey thematic elements such as the contrast between fantasy

and reality.

Imagery of the countryside. Throughout the novel, Cervantes uses detailed

descriptions of the Spanish countryside to create a sense of place and atmosphere. For

example, when Don Quixote is riding through the countryside, Cervantes writes: "they

traveled through a vast and unbroken plain, which they said was the La Mancha" (Chapter

2). The use of the word "vast" and the description of the "unbroken plain" help to create a

sense of the vastness and emptiness of the landscape.

Imagery of chivalry. Cervantes also uses imagery related to chivalry to create a sense

of grandeur and heroism. For example, when Don Quixote first sees Dulcinea, Cervantes

writes: "her beauty was so great that it confused the understanding of those who tried to

describe it" (Chapter 3). The use of the word "confused" suggests the overwhelming power

of Dulcinea's beauty.

Imagery of madness. Another key element of Don Quixote is the protagonist's

descent into madness. Cervantes uses imagery related to madness to convey the confusion

6 John Mark F. Valencia

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

and disorientation of Quixote's state of mind. For example, when Quixote is in the grip of

his delusions, Cervantes writes: "his wits were gone, and he raved as if he were out of his

mind" (Chapter 8). The use of the word "raved" and the description of Quixote as being "out

of his mind" create a sense of the protagonist's disordered mental state.

Imagery of deception. Cervantes also uses imagery related to deception to convey the

novel's themes of illusion and reality. For example, when Quixote mistakes a windmill for a

giant, Cervantes writes: "It was a fearful sight, and it made him tremble in every limb"

(Chapter 8). The use of the word "fearful" suggests the power of Quixote's delusions, while

the image of the windmill as a giant creates a sense of the protagonist's confusion and

misperception.

Cervantes' use of imagery in Don Quixote is a key element in the novel's style and

thematic content. His descriptions of the countryside, chivalry, madness, and deception

create a rich and evocative portrait of the world of the novel.

Philosophic Inquiry of Miguel De Cervantes’ Don Quixote

Textual masterpieces also weave wisdom throughout the entire text; they unfold in

an amalgam of singular, aphoristic musings, planted amid the aforementioned illuminating

imagery. Philosophical inquiry in literary text refers to the use of literary works to explore

philosophical questions and ideas. Like philosophy, novels make arguments and explicitly

engage the range of philosophical questions; and like literature, essential elements of

philosophy include aesthetic considerations. Literature can be used as a tool to understand

philosophical concepts and ideas (Jaima, 2019).

In Miguel De Cervantes’ Don Quixote, several philosophies can be found. These

philosophical ideas are more likely embedded in the novel’s themes. These are truth and

lies, realism and idealism, madness and sanity, intention and consequence, self-invention,

class identity, and social change.

Truth and Lies. At the heart of Quixote’s disagreement with the world around him is

the question of truth in chivalry books. His niece and housekeeper, his friends the barber

and the priest, and most other people he encounters in his travels tell Quixote that chivalry

romances are full of lies. Over and over again, Quixote struggles to defend the truthfulness

of the stories he loves. In that struggle, he begins to redefine conventional notions of truth

in ways that align closely with the philosophical trends of the Enlightenment.

Cervantes also satirizes that sort of truth in his portrayals of narrow-minded

characters with stubborn, myopic ideas. The alternative, imaginative kind of truth, which

varies from person to person, finds its main spokesperson in Quixote. For Quixote, chivalry

stories are true because people believe in them, not the reverse. He describes truth as

7 John Mark F. Valencia

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

something palpable and sustaining, a kind of imaginative warmth and brightness. And he

believes that truth is something to aspire to, a vision of the world as it should be.

Realism and Idealism. Quixote and Sancho seem like caricatures of idealism and

realism. Philosophical idealism holds that reality is primarily a set of ideas, private mental

constructs; political idealism holds that ideas can meaningfully transform the human world.

Philosophical realism holds that reality is primarily material, and that its qualities exist

independently of human perception and interpretation. Quixote sees the world around

him as a set of beliefs about honor, goodness, gallantry, and courage, and as an

opportunity for social change on a large scale; Sancho sees a world filled with detail, with

sounds, smells, and textures, and as an opportunity to eat well and sleep deeply.

Madness and Sanity. Quixote is considered insane because he “see[s] in his

imagination what he didn’t see and what didn’t exist.” He has a set of chivalry-themed

hallucinations. But then, they are not quite hallucinations, which by definition occur

without any external stimulus. They are distorted perceptions of real objects and events. To

see giants instead of windmills is, in a way, just a very peculiar interpretation of large,

vaguely threatening objects in motion.

And many other instances of Quixote’s madness – his rigid principles, his obsession

with knighthood – are also peculiarities. The priest and the barber, who persecute Quixote

in the guise of well-wishers trying to restore his sanity, are simply trying to stamp out his

unsettling peculiarity. They are conducting a witch-hunt in the timeless manner of

narrow-minded people threatened by strangeness.

Quixote’s madness is ambiguous and paradoxical, because he both and does not

see; he sees the giants in his imagination, but he does not hallucinate giants in the world

outside. His madness consists in his trusting his imagination over his perception, and his

imagination is captivated by the values of chivalry books. His madness is a state of thrall to

a coherent imagined world. But in the course of his adventures, that world loses its

coherence: it is shaken by internal inconsistencies and by the world’s complications and

contradictions. When Quixote declares on his deathbed that he is finally sane, he means

that the imagined world has lost its grip on him, and he is left with a chilling blankness that

cannot sustain him.

Intention and Consequence. For Quixote, gaps between intention and consequence

mark the failures of the chivalric way of life. Quixote tries to help others by following the

elaborate conventions outlined in chivalry novels, but his efforts often backfire – most

obviously in the episode with the shepherd boy, who is beaten even more severely after

Quixote intervenes. The first few times Quixote’s efforts backfire, he defends his actions by

claiming, in effect, that intention is more important than consequence – that a knight’s duty

is to react courageously, not to judge precisely.

8 John Mark F. Valencia

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

But as negative consequences pile up, Quixote begins to alter his reasoning. When

he observes that appearances can be deceitful, he acknowledges that a person has a

responsibility to look past the traps and illusions of appearance to a more solid foundation

of truth. If appearances can be deceitful, then a knight should not act impulsively because

someone or something looks sinister – he must dig deeper to identify the most ethical

course of action. This is a difficult task, and by the end of the novel it seems to overwhelm

Quixote. He despairs to see that each event is a tangled ball of motives and desires, to

realize that his chivalry rulebook is not an adequate guide to the world, after all.

Self-Invention, Class Identity, and Social Change. One of the first scenes of the novel is

Quixote’s self-naming. The scene is a little comical, like a child renaming herself after her

favorite cartoon character, yet it’s also extraordinary. An aging, poor, frail man claims for

himself the power to remake himself entirely, merely on the strength of his belief. He is

blissfully indifferent to his own past, his capacities, or the constraints of his situation; he

becomes what he wishes to be instantaneously, almost like a god.

Quixote believes that identities and societies are always in flux, always about to be

changed by the force of ideals. He believes that each person should be valued on the

strength of her character, not on the circumstances of her birth; he thinks that every

person, rich or poor, nobleman or peasant, can become good, brave, and courteous,

despite the social boundaries that fence us into various stereotypes and stations.

Syntactical Fluidity of the Novel

One of the defining features of the novel's syntax is its use of long, complex

sentences. Cervantes was known for his ability to construct sentences that were both

syntactically complex and yet clear and easy to understand. This fluidity and complexity of

his sentences allowed him to convey complex ideas and emotions in a way that was both

elegant and accessible.

The novel is also characterized by its use of digressions, which are long and

meandering passages that depart from the main narrative. These digressions can take

many forms, including stories within stories, asides to the reader, and philosophical

musings. While they may seem extraneous or unnecessary to the plot, they add depth and

richness to the novel and contribute to its overall philosophical and thematic complexity.

Cervantes also uses language in innovative ways, playing with words and using

puns, wordplay, and other linguistic devices to create a sense of playfulness and humor.

This use of language is particularly evident in the character of Don Quixote himself, who

often speaks in a grandiose and elaborate style that is both absurd and charming.

"In short, the priest and Sancho conducted Don Quixote to bed and

waited on him for three days, during which time they had some very long

conversations with him, in which he gave them an account of his life, all

9 John Mark F. Valencia

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

through his madness, with such an air of good sense and good faith that

they were convinced that he was entirely sane when he was in his right

mind, and out of it mad; and they concluded that, all things considered,

there was no reason to deprive him of his liberty, and that the errant

knight might very well be allowed to roam about in search of adventures,

provided that he promised to behave himself in the future, as he had

done in the past." (Part I, Chapter 17)

This passage is an example of a digression because it departs from the main

narrative of the story to provide background information on Don Quixote's character and

his conversations with the priest and Sancho. This digression allows the reader to gain a

deeper understanding of Don Quixote's character and motivations and adds depth and

richness to the novel.

Some Important Notes on the Novel’s Plot

Don Quixote, by Miguel de Cervantes, is a novel with a complex and multi-layered

plot. At its most basic level, the novel follows the adventures of the eponymous character,

Don Quixote, a man who has become so enamored with the stories of chivalry and

romance that he has lost touch with reality. The novel is structured around a series of

loosely connected episodes, each of which sees Don Quixote embarking on a new

adventure, often accompanied by his loyal squire, Sancho Panza.

As the novel progresses, the focus shifts from Don Quixote's adventures to the

people around him, including Sancho Panza, the various characters he encounters on his

travels, and the people who are affected by his actions. In this way, the novel becomes a

broader exploration of the human experience, examining questions of identity, morality,

and the nature of reality.

Issues on Manuscript of Cervantes’ Masterpiece

Ever since the Quixote has been annotated, according to Lathrop, many book

editors have pointed out that the book is filled with inconsistencies, contradictions, and

errors. This is actually true or at least agreed by those who attempted and thrived to

translate the original version to another target language.

In the 1830s, the novel has been proclaimed as masterwork of world literature yet

allegedly written by an extremely careless author who wrote at full speed without ever

going over his work, and that he included hundreds of contradictions without ever realizing

his terrible mistakes. That there are hundreds of inconsistencies is undeniable, but that

Cervantes was a careless writer is very far from the truth.

Since there are no wholesale contractions in his other works, the obvious conclusion

has to be that Cervantes put them in Don Quixote on purpose. Simple explanations

10 John Mark F. Valencia

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

provided by editors was that Cervantes advertised the objective in writing Don Quixote was

to imitate and make so much fun of the ancient romances of chivalry – books that told tales

of roaming knights in armor – that no further ones would be written. Cervantes was quite

successful since no new romances were written in Spanish after Don Quixote came out.

In order to imitate the romances fully, Cervantes satirized not only their content but

also imitated their careless style. In fact, this intent is clearly stated in the Prologue to Part I.

One of the lines in that section states that “You only have to imitate the style of what you are

writing, the more perfect the imitation is, the better your writing will be.” Far from being a

defect in the book, these contradictions are truly an integral part of the art of the book. No

one can convince that Cervantes, whose erudition and memory were so vast that he was

able to cite, in the book translated by Lathrop, 104 mythological, legendary, and biblical

characters; 131 chivalresque, pastoral, and poetic characters; 227 historical persons pr

lineages; 21 famous animals; 93 well-known books, 261 geographic locations; 210 proverbs;

and who created 371 characters (230 of whom have speaking roles). To fonder on this,

Cervantes could easily forget from paragraph to the next name of Sancho Panza’s wife for

instance. Sancho’s wife is called Juana Gutierrez in Part I, chapter 7, and Marie Gutierrez

four lines later. She is also known as Juana Panza, Teresa Panza, and Teresa Cascajo. Of

great interest is the real name of Don Quixote himself. Half a dozen variants are proposed

(Quixano, Quesada, Quijana…) On a couple of occasions, one of them is proclaimed to be

the true one, each one a different variant.

Cervantes imitated the careless style of these romances by, in a very carefully

planned way, making mistakes on purpose about practically everything, and he made sure

that whatever was said was eventually contradicted.

In Part I, chapter four, when Don Quixote makes an error in math and says that

seven times nine is seventy-three, some editors and translators think that the typesetter

has made a mistake. Afterall, there is only one letter different between sixty and seventy in

the Spanish language. However, it is not a typesetter mistake, this is Don Quixote’s math

error.

On another occasion, Don Quixote makes a mistake when he says that the biblical

Samson removed the doors of the temple. It was really the gates of the city of Gaza that

Samson tore off. Cervantes inserted this error on purpose, either to show that Don

Quixote’s biblical knowledge was faulty, or to show that in the heat of excitement one’s

memory is as acute as it should be. To some historians and literary writers, this is another

proof of Cervantes’ lack of attention and of his carelessness in quotations is ludicrous.

However, it is indeed that the characters are capable of making their own mistakes all by

themselves, and when they make them, it should be realized that they belong to the

characters and to the author. Cervantes, as a rule, simply does not make mistakes and he

does not care either. Indeed, he had to be particularly keen and creative in order to make

11 John Mark F. Valencia

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

sure everything was contradicted. Every contradiction, every mistake, every careless turn of

phrase is there because Cervantes wanted it exactly that way.

Aside from those misconceptions of Cervantes' proposed or intentioned error.

There are several reasons why Don Quixote is considered a masterpiece of world literature.

One of the most significant is its innovative use of narrative structure and literary form. At

the time of its publication in the early 17th century, the novel was a relatively new literary

genre, and Cervantes pushed the boundaries of what was possible with the form. For

example, he incorporated elements of popular storytelling traditions like the chivalric

romance and the picaresque novel, while also experimenting with more modern

techniques like metafiction and self-reflexivity. The result is a novel that is both

entertaining and intellectually engaging, with a richness and complexity that has continued

to captivate readers for centuries.

Another reason for the novel's enduring appeal is its memorable characters. Don

Quixote, with his eccentricities and quirks, has become an iconic figure in world literature,

and his sidekick Sancho Panza is similarly beloved. The novel's other characters are equally

memorable, each with their own distinct personalities and quirks. Cervantes has a

remarkable ability to capture the essence of human nature in his characters, making them

relatable and sympathetic even when they are flawed or eccentric.

Don Quixote is also a novel with a timeless quality, addressing universal themes and

issues that continue to resonate with readers today. Its exploration of the tension between

reality and illusion, the power of storytelling, and the nature of the human experience are

all as relevant today as they were when the novel was first published. In this way, Don

Quixote has transcended its historical context and become a timeless masterpiece that

speaks to readers across generations and cultures.

Miguel De Cervantes’ Don Quixote on Human Transformation

Miguel De Cervantes' Don Quixote is a novel that explores the transformation of

human identity in a number of ways. At its core, the novel is a study of the power of the

human imagination to shape our perceptions of ourselves and the world around us, and

the ways in which our identities are shaped by the stories we tell ourselves and others.

One of the most striking transformations in the novel is that of Don Quixote himself.

At the beginning of the novel, he is a man who has become so consumed by the stories of

chivalry and romance that he has lost touch with reality, and his identity is defined by his

obsession with these stories. However, over the course of the novel, he begins to question

the validity of these stories and to see the world in a more nuanced and complex way. He

begins to realize that his idealized vision of the world is not necessarily the reality, and he

becomes humbler and more reflective as a result.

12 John Mark F. Valencia

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

Similarly, the character of Sancho Panza also undergoes a transformation over the

course of the novel. At first, he is a simple, uneducated man who is content to follow Don

Quixote on his adventures. However, as he becomes more involved in Don Quixote's quest,

he begins to develop his own sense of identity and purpose, and he becomes more

assertive and confident as a result.

In addition to these individual transformations, the novel also explores the broader

question of how our identities are shaped by the stories we tell ourselves and others. Don

Quixote's obsession with chivalric stories is, in many ways, a reflection of the power of

literature to shape our perceptions and values. However, the novel also shows how this can

be a double-edged sword, as our reliance on stories and ideals can sometimes blind us to

the realities of the world around us.

Masterpiece’s Reflection on Human Identity and Society

Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote can offer insights into the questions of who we

are, what it means to be human, and how we relate to society. The novel explores these

questions through its portrayal of its main characters and their interactions with each other

and the world around them (Spitzer, 1962).

One of the central themes of the novel is the nature of reality and the tension

between reality and illusion. Don Quixote, the novel's protagonist, is a man who becomes

so consumed by his own idealized vision of the world that he loses touch with reality. This

raises questions about the role of imagination in shaping our perceptions of the world and

ourselves, and the ways in which our identities are constructed through the stories we tell

ourselves and others.

The novel also explores the question of what it means to be human through its

portrayal of the relationships between its characters. Don Quixote and his sidekick Sancho

Panza have a complex relationship that is both master-servant and friend-friend. Through

their interactions, the novel raises questions about power dynamics, friendship, and the

nature of human relationships.

Finally, the novel offers insights into how we relate to society through its portrayal of

the various social structures and institutions that shape the characters' lives. The novel

explores issues of social class, gender roles, and the power dynamics between individuals

and society. Through its satirical tone and its use of humor, the novel critiques these social

structures and offers a vision of a more egalitarian society.

Conclusion

13 John Mark F. Valencia

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

Don Quixote offers insights into various aspects of the human condition, including

the power of imagination, the dangers of idealism, the complexity of human nature, the

significance of storytelling, and the nature of truth and perception. Don Quixote is known

for his vivid imagination, which leads him to see the world in a different light. This

highlights the transformative power of imagination and encourages us to embrace our own

imaginative capacities. Don Quixote's idealism and quest for chivalry are portrayed as both

noble and foolish. His relentless pursuit of a romanticized version of reality leads him to

disregard practicality and ignore the consequences of his actions. Cervantes warns us

about the dangers of excessive idealism and the importance of grounding our aspirations

in reality. Moreover, Don Quixote himself is a mixture of admirable qualities, such as

bravery and loyalty, but also demonstrates delusion and irrationality. This reflects the

complexity and inherent contradictions of human nature, reminding us that people are not

easily categorized as purely good or bad. Hence, the novel explores the impact and

influence of literature, showing how stories shape our perception of reality and can inspire

individuals to pursue their own quests. Cervantes emphasizes the importance of

storytelling as a means of self-expression, entertainment, and understanding. These

lessons continue to resonate with readers, making the novel a timeless masterpiece of

literature.

Little to Known by Anyone: Trivia to Miguel De Cervantes’ Don Quixote

The word "Quixotic" is derived from the character Don Quixote and is commonly

used in the English language to describe someone or something that is idealistic,

impractical, or motivated by noble but unrealistic goals or pursuits. It refers to a person

who is extremely enthusiastic and passionate about a cause or mission, often to the point

of being unrealistic or impractical in their approach.

Also, the song “Impossible Dream (The Quest)” which is a popular song composed by

Mitch Leigh, with lyrics written by Joe Darion was from the 1965 Broadway musical “Man of

La Mancha” inspired by Miguel De Cervantes’ Don Quixote. The song itself highlights life

and ideals of Cervantes’ Don Quixote (Kiger, 2014).

References

Brink, A., & Brink, A. (1998). The Wrong Side of the Tapestry: Miguel de Cervantes: Don

Quixote de la Mancha. The Novel: Language and Narrative from Cervantes to Calvino,

20-45.

Dom Quixote - Resumo, Autor E Análise - Arena Marcas E Patentes. (n.d.). Arena Marcas e

Patentes. Retrieved June 2, 2023, from

https://registrodemarca.arenamarcas.com.br/educacao/dom-quixote-resumo-autor-e-

analise/

14 John Mark F. Valencia

LITERARY HISTORY AND MASTERPIECES

Don Quixote | Summary, Legacy, & Facts. (n.d.). Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved June 2,

2023, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Don-Quixote-novel

Huff, H. (2018, September 20). 8 Key Literary Elements in Every Written Masterpiece - Notes

of Oak. Notes of Oak. Retrieved June 2, 2023, from

https://notesofoak.com/discover-literature/8-key-literary-elements/

Jaima, A. R. (2019). Literature Is Philosophy: On the Literary Methodological Considerations

That Would Improve the Practice and Culture of Philosophy. The Pluralist, 14(2), 13–29.

https://doi.org/10.5406/pluralist.14.2.0013

Kiger, P. (2014). The Man Who Dreamed Up The Impossible Dream. Retrieved 2 June 2023

from https://blog.aarp.org/legacy/the-man-who-dreamed-up-the-impossible-dream.

Lathrop, T. (2011). Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra Don Quixote. Fourth-Centenary

Translation. Penguin Group, Signet Classics. 357 Hudson Street, New York, New York 1004,

USA.

Predmore, R. L. (1967). The World of Don Quixote. Harvard University Press.

Spitzer, L. (1962). On the Significance of Don Quijote. MLN, 77(2), 113–129.

https://doi.org/10.2307/3042856

Thacker, Jonathan, ‘Don Quijote in English Translation’, in James A. Parr and Lisa Vollendorf,

eds, Don Quixote’, second edition (New York, 2015) 1580.560000

Translation, E. G. S. (2006). of Don Quixote. Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of

America, 26(2008), 237-55.

15 John Mark F. Valencia

You might also like

- Don Quixote (Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha (Spanish: El Ingenioso HidalgoDocument9 pagesDon Quixote (Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha (Spanish: El Ingenioso HidalgokhwenkNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote and MacbethDocument3 pagesDon Quixote and MacbethJayJayPastranaLavigneNo ratings yet

- Postmodernism and Fiction - Barry LewisDocument12 pagesPostmodernism and Fiction - Barry Lewisdaniel75% (4)

- Don QuixoteDocument5 pagesDon QuixoteChinie Rose Pama FloresNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote Book I Study GuideDocument42 pagesDon Quixote Book I Study GuideHenry SmitovskyNo ratings yet

- English 1-29-20Document3 pagesEnglish 1-29-20Jzzr DumpNo ratings yet

- Renaissance in Spanish LiteratureDocument20 pagesRenaissance in Spanish LiteraturedfuibrsiufNo ratings yet

- The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes - Delphi Classics (Illustrated)From EverandThe Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes - Delphi Classics (Illustrated)No ratings yet

- Don Quixote by Miguel de CervantesDocument17 pagesDon Quixote by Miguel de CervantesAramNo ratings yet

- Lec 18 Don QuixDocument8 pagesLec 18 Don QuixEdzel Anne De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Miguel de CervantesDocument6 pagesAnalysis of Miguel de Cervantesruslan.bondarenkoNo ratings yet

- Lec 18 Don QuixDocument8 pagesLec 18 Don QuixEljesa LjusajNo ratings yet

- Don Chisciotte - LosadaDocument2 pagesDon Chisciotte - LosadaHelenaNo ratings yet

- Don QuixoteDocument3 pagesDon Quixoterianne ivansNo ratings yet

- Don QuixoteDocument19 pagesDon QuixoteАлина СладкаедкаNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote EnglishDocument4 pagesDon Quixote EnglishcristianeitorpatopatoNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote in 2000 WordsDocument3 pagesDon Quixote in 2000 Wordsandrewholly999No ratings yet

- All About Renaissance AND Don QuixoteDocument40 pagesAll About Renaissance AND Don QuixoteJamille Ann Isla VillaNo ratings yet

- DQDLM PCDocument4 pagesDQDLM PCJennie Sanaco BasaNo ratings yet

- Don QuixoteDocument2 pagesDon QuixotemaissiemalloriNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote and The End of Knight Literature: Yan LiuDocument6 pagesDon Quixote and The End of Knight Literature: Yan LiuManjuNo ratings yet

- Presented by Sruthi S. KumarDocument21 pagesPresented by Sruthi S. Kumarsruthi s kumarNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideFrom EverandDon Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes (Book Analysis): Detailed Summary, Analysis and Reading GuideNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote ResumeDocument1 pageDon Quixote ResumealderNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote PDFDocument2 pagesDon Quixote PDFHamza DouichiNo ratings yet

- W3 Reading Activity PDFDocument2 pagesW3 Reading Activity PDFLorenz PateñoNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote ReportDocument1 pageDon Quixote ReportRama MalkawiNo ratings yet

- Novel: El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de La ManchaDocument2 pagesNovel: El Ingenioso Hidalgo Don Quijote de La ManchaWilliam DavisNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote and The Windmills : Miguel de CervantesDocument19 pagesDon Quixote and The Windmills : Miguel de CervantesRizza Mae EudNo ratings yet

- Tilt - The New York Times - Don QuixoteDocument5 pagesTilt - The New York Times - Don QuixoteAnarcoNo ratings yet

- Don QuixoteDocument1 pageDon QuixotediogoNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote 1Document46 pagesDon Quixote 1Edward Estrella GuceNo ratings yet

- Don QuixoteDocument18 pagesDon QuixoteMarcos Pérez Collantes0% (1)

- The Adventure With The: WindmillsDocument14 pagesThe Adventure With The: WindmillsKasdeya PlaysNo ratings yet

- Spanish Literature LectureDocument3 pagesSpanish Literature LectureairacrisjuanNo ratings yet

- Don QuixoteDocument9 pagesDon QuixoteRobert SorterNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote: by Miguel de CervantesDocument30 pagesDon Quixote: by Miguel de Cervantesrozha jihanNo ratings yet

- ResumenDocument2 pagesResumenSeñor BichidosNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote: About The AuthorDocument3 pagesDon Quixote: About The AuthorP TruNo ratings yet

- 10 Don QuixoteDocument18 pages10 Don QuixotemaxNo ratings yet

- MODULE 3 - Revisiting The ClassicsDocument22 pagesMODULE 3 - Revisiting The ClassicsSneha MichaelNo ratings yet

- Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616) : The Legacy of CervantesDocument4 pagesMiguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616) : The Legacy of Cervantesরবিন মজুমদারNo ratings yet

- Synopsis of Don QuixoteDocument3 pagesSynopsis of Don QuixoteDOLORFEY L. SUMILENo ratings yet

- Don QuixoteDocument21 pagesDon Quixotesruthi s kumarNo ratings yet

- Harold Bloom. Hamlet and Don QuixoteDocument10 pagesHarold Bloom. Hamlet and Don QuixoteAlejandro MiguezNo ratings yet

- The Second Part of the Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes - Delphi Classics (Illustrated)From EverandThe Second Part of the Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes - Delphi Classics (Illustrated)No ratings yet

- Don Quixote AnalysisDocument2 pagesDon Quixote AnalysisAleksandra MishkovskaNo ratings yet

- Summary Don Quixote Vicens VivesDocument17 pagesSummary Don Quixote Vicens VivesScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- Don QuijoteDocument45 pagesDon QuijoteMaja KovačićNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote: A Bridge From The Middle Ages To Modernity: Bsmith 1Document12 pagesDon Quixote: A Bridge From The Middle Ages To Modernity: Bsmith 1ErleNo ratings yet

- Don QuixoteDocument6 pagesDon Quixotecatish.kimNo ratings yet

- Monograph Cervantes Don QuixoteDocument5 pagesMonograph Cervantes Don QuixoteFrank Daniel Espirítu ValeraNo ratings yet

- E-Book English Literature (1) - 1Document101 pagesE-Book English Literature (1) - 1jyotikaushal98765No ratings yet

- Title: Don Quixote: University of MakatiDocument6 pagesTitle: Don Quixote: University of MakatiZ eeNo ratings yet

- Don Quijote de La ManchaDocument2 pagesDon Quijote de La ManchaMari IbañezNo ratings yet

- Don Quixote and Chivalric IdealsDocument3 pagesDon Quixote and Chivalric IdealsManjuNo ratings yet

- Textiles Homework ProjectsDocument6 pagesTextiles Homework Projectsafmsmobda100% (1)

- The Art of Pencil Drawing PDFDocument158 pagesThe Art of Pencil Drawing PDFelenaluca50% (2)

- Greek Art HistoryDocument23 pagesGreek Art HistoryMyra Nena Carol EduaveNo ratings yet

- Defamiliarization in E.E. Cumming5' Poem "5pring 15 Like A Perhap5 Hand"Document5 pagesDefamiliarization in E.E. Cumming5' Poem "5pring 15 Like A Perhap5 Hand"Nermin OrmanovicNo ratings yet

- HOA - Condensed Notes by YamDocument4 pagesHOA - Condensed Notes by YamMiriam San JuanNo ratings yet

- Teaddy Bear ReadingDocument2 pagesTeaddy Bear ReadingIruki IrukiñaNo ratings yet

- Oliver The Donkey Pattern: @ipseveranneDocument7 pagesOliver The Donkey Pattern: @ipseverannemariajoaomoreira100% (1)

- Ak12015 MagnetDocument1 pageAk12015 MagnetBENoNo ratings yet

- Technology of Iron and SteelDocument29 pagesTechnology of Iron and SteelTanya SirohiNo ratings yet

- The Ambiguous Feminism of Boccaccio A ReDocument11 pagesThe Ambiguous Feminism of Boccaccio A ReFrancis Robles SalcedoNo ratings yet

- Kenilworth Castle Phased Plans PDFDocument2 pagesKenilworth Castle Phased Plans PDFMisha JoseNo ratings yet

- Inked November 2015Document100 pagesInked November 2015mar phisNo ratings yet

- The Power Behind The Smile: Ninja World Tournament - Ally EventsDocument3 pagesThe Power Behind The Smile: Ninja World Tournament - Ally EventsninosaurusNo ratings yet

- Less Is More: Latest Trend Is Sure To Stay For LongerDocument3 pagesLess Is More: Latest Trend Is Sure To Stay For LongerShwetha HCNo ratings yet

- Isaac Rosenberg, A Great Neglected Poet ADocument1 pageIsaac Rosenberg, A Great Neglected Poet AOmar QuilliganaNo ratings yet

- Wima Takto - One or Two Archaeological An PDFDocument20 pagesWima Takto - One or Two Archaeological An PDFZaheerNo ratings yet

- Eric Burdon: The AnimalsDocument6 pagesEric Burdon: The AnimalsХристинаГулеваNo ratings yet

- Art Education Lesson Plan Template 1.) Book Sculpture /11-12 Grade /7 Days Project 2.) GoalsDocument7 pagesArt Education Lesson Plan Template 1.) Book Sculpture /11-12 Grade /7 Days Project 2.) Goalsapi-457682298No ratings yet

- Something Like Bags TAB - Wes MOntgomeryDocument4 pagesSomething Like Bags TAB - Wes MOntgomerymabbagliati100% (1)

- Alfred Prufrock-T.S.EliotDocument3 pagesAlfred Prufrock-T.S.EliotAbdulRehman100% (2)

- Liping Die Zauberflöte PaperDocument11 pagesLiping Die Zauberflöte PaperLiping XiaNo ratings yet

- Warp Weighted Loom Weights Their Story ADocument21 pagesWarp Weighted Loom Weights Their Story Aumut kardeslerNo ratings yet

- Overview of Lyric Poetry The Sonnet Mini-LessonDocument23 pagesOverview of Lyric Poetry The Sonnet Mini-Lessonapi-433415320No ratings yet

- Theatre Street Journal Vol1 No1 July 2015Document193 pagesTheatre Street Journal Vol1 No1 July 2015Sourav Gupta100% (1)

- Rockbot Song ListDocument7 pagesRockbot Song ListCarson BakerNo ratings yet

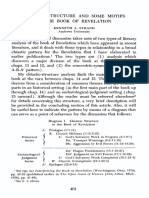

- Chiastic Structure and Some Motifs in The Book of RevelationDocument8 pagesChiastic Structure and Some Motifs in The Book of RevelationGerman Dario GalvanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - ArtsDocument3 pagesChapter 2 - Artsandrea227No ratings yet

- Humanities Module 5Document6 pagesHumanities Module 5Shey MendozaNo ratings yet

- Cpar Tos Diagnostic-TestDocument2 pagesCpar Tos Diagnostic-TestAvelyn Narral Plaza-ManlimosNo ratings yet