Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sacramental Spirituality Review Bernard Haring

Sacramental Spirituality Review Bernard Haring

Uploaded by

mertoosCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sacramental Spirituality Review Bernard Haring

Sacramental Spirituality Review Bernard Haring

Uploaded by

mertoosCopyright:

Available Formats

of its self-expressions, the ways it did bear witness to the Lord; hence the four

sections into which the articles are grouped: the apostolic church and preaching,

liturgy, written gospels, and missionary activity. Scripture students can hope

that Stanley will further pursue this analysis and synthesize his discoveries in a

work more formally ecclesiological.

The volume is not without defects that could easily have been avoided. An

index of scripture passages is missing, all the more unfortunate in that Stanley

usually gives his own translations. And any reader is jusdy disappointed that

the footnotes have been relegated to that awkward, clumsy location in the back

of the book.

St. John's Abbey Job Dittberner, OSB.

A Sacramental Spirituality. By Bernard Haring, C.SS.R. Translated by R. A.

Wilson. Sheed and Ward, New York. 1965. Pp. 281. Cloth, $5.00.

When a man is confronted with the reality beyond his powers of expression, he

responds in two ways: he accepts the reality and lives with it, or he attempts to

reduce the reality to his terms so he can define it. Both responses are valid.

When in the area of God's plan of salvation, however, the tendency to define

God's action in the cramped small letters of our vocabulary can lead us astray.

For many years the highly technical explanation of the sacraments, translated

into the handy memorizable phrases of the catechism, has left us devoid of the

reality of God's self-giving manifested to us in the sacraments. A gross over-

simplification results if a Christian attempts to live out the mystery of his sal-

vation according to definitions. The sacraments get placed in the realm of some-

thing we do. As it were, fill out correcdy the application blank and get a prize.

The liturgy becomes human exactitude and a matter of legality. In such a view

the sacraments become ritualism, and salvation, morality taught from a ca-

nonical viewpoint.

Father Bernard Häring does much to defeat the notion that Christian moral-

ity is a mere ethics and Christian worship human perfectionism. Christian

morality in fact is spirituality,, that is, life in the Spirit. We experience this life-

giving Spirit in our encounter with the risen Christ in the sacraments. We have

grown to expect of Father Häring a book such as Sacramental Spirituality, for

he has always integrated our everyday life in the basic mystery of salvation, the

passover of Christ. Christian spirituality builds on the- fact that we are saved

in Christ; and we meet Christ today in sign^u* his earthly visibilty, the, church.

Ihe basic premise of Father Haring's teaching is the gratuity of salvation,

that God acts first. Sin is egoism, self-centeredness, the attitude that we save

ourselves or, in other words, that we do not need the Father. If a Christian is to

act spiritually, if his actions are to be worthy of salvation, they must become the

action of Christ. Building on the belief that Christ is all and we are in Christ,

Boo\ Reviews 121

Father Häring the moral theologian does not hesitate to ground moralitv and

Christian existence in the sacraments, the sacraments not seen as definitions but

PSrov^terie*to be lived.

The book reads much like a retreat. It is not a systematic study from the view-

point of exegesis or historical development. But a retreat does not attempt to do

this. For many non-theologians it is a good introduction to the renewed aware-

ness of a theology concerned with the presence of Christ in the sacraments and

the possibility of our experiencing this presence. The book can also serve many

priests in their preparations for sermons and instructions.

Holy Rosary Church Tobias Maeder, O.S.Β.

Detroit La\es, Minnesota

The Christian and the World: Readings in Theology. By Alfons Auer et al.

Compiled at the Canisianum, Innsbruck. P. J. Kenedy & Sons, New York. 1965.

Pp. xx-229. Cloth, $4.95.

Written large across the page of contemporary theology is the word History.

Not only have the methods of historical research which have given us profound

insights about the gospel resulted in renewed interest in the history of dogma,

liturgy, and the Bible, but also the awareness of history as the basic dimension

of human existence has predominated in the theology of renewal promulgated

by the council fathers. The concern for widening the horizon of the Roman

Catholic, clerical and lay, to include not only other Christian churches, but also

other religions, and even the world, has arisen from a confrontation of the

gospel message by the philosophies of history and the scientific studies of evolu

tion. For the large question facing the believer today is whether the direction

of the history of humankind, which is disenchanting itself at a rapid rate of the

superstitions and fears of primitive man, is God-ward or toward the utopia

achieved by the efforts of man.

The doctrine propounded by contemporary secular thinkers and the prophetic

vision of the scientific theories of Chardin are definitely anthropological in

emphasis. "The cosmos is now situated in the horizon of man rather than man

in the horizon of the cosmos" (Auer, p. 28). The ascendency of man has been

asserted and the beginning of a new era proclaimed. "This man of the unified,

planetary living-space which is extended even beyond the earth . . . has . . .

the impression of standing at a beginning, of being the beginning of the new

man, conceived as a kind of a superman who will show clearly for thefirsttime

what man really is" (Rahner, p. 210).

This collection of articles by European theologians asks whether belief in

salvation given us by the Father in Christ lesus makes sense in the face of the

achievements of the modern world. The first three articles, by Alfons Auer,

Karl Rahner, and Johannes Metz, attempt a theology of the world, to mark out

122 Worship: Volume 40, Number 2

^ s

Copyright and Use:

As an ATLAS user, you may print, download, or send articles for individual use

according to fair use as defined by U.S. and international copyright law and as

otherwise authorized under your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement.

No content may be copied or emailed to multiple sites or publicly posted without the

copyright holder(s)' express written permission. Any use, decompiling,

reproduction, or distribution of this journal in excess of fair use provisions may be a

violation of copyright law.

This journal is made available to you through the ATLAS collection with permission

from the copyright holder(s). The copyright holder for an entire issue of a journal

typically is the journal owner, who also may own the copyright in each article. However,

for certain articles, the author of the article may maintain the copyright in the article.

Please contact the copyright holder(s) to request permission to use an article or specific

work for any use not covered by the fair use provisions of the copyright laws or covered

by your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement. For information regarding the

copyright holder(s), please refer to the copyright information in the journal, if available,

or contact ATLA to request contact information for the copyright holder(s).

About ATLAS:

The ATLA Serials (ATLAS®) collection contains electronic versions of previously

published religion and theology journals reproduced with permission. The ATLAS

collection is owned and managed by the American Theological Library Association

(ATLA) and received initial funding from Lilly Endowment Inc.

The design and final form of this electronic document is the property of the American

Theological Library Association.

You might also like

- Apologetics at the Cross: An Introduction for Christian WitnessFrom EverandApologetics at the Cross: An Introduction for Christian WitnessNo ratings yet

- Historical Theology: An Introduction to Christian DoctrineFrom EverandHistorical Theology: An Introduction to Christian DoctrineRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (22)

- Renewal Theology: Systematic Theology from a Charismatic PerspectiveFrom EverandRenewal Theology: Systematic Theology from a Charismatic PerspectiveRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (12)

- Biblical Interpretation Then and Now - Contemporary Hermeneutics in The Light of The Early Church (PDFDrive)Document356 pagesBiblical Interpretation Then and Now - Contemporary Hermeneutics in The Light of The Early Church (PDFDrive)Stephen Luna100% (7)

- R.V. Sellers Two Ancient Christologies Alexandria AntiochDocument142 pagesR.V. Sellers Two Ancient Christologies Alexandria Antiochkamweng_ng7256100% (2)

- Chrysostom's Sermons On Genesis - A Problem PDFDocument14 pagesChrysostom's Sermons On Genesis - A Problem PDFZakka Labib100% (1)

- A Layman's Guide To Theology and ApologeticsDocument150 pagesA Layman's Guide To Theology and ApologeticsKen100% (6)

- C. F. D. Moule The Holy Spirit 2000Document129 pagesC. F. D. Moule The Holy Spirit 2000RudolfEarringsmaADAM100% (5)

- Quantum Spirituality Leonard SweetDocument285 pagesQuantum Spirituality Leonard Sweetwraygraham4538No ratings yet

- Being Salvation: Atonement and Soteriology in the Theology of Karl RahnerFrom EverandBeing Salvation: Atonement and Soteriology in the Theology of Karl RahnerNo ratings yet

- Christian TheologyDocument362 pagesChristian TheologyEBHobbit100% (3)

- Comic Literature - Tragic Theology A Study of Judges 17-18 PDFDocument9 pagesComic Literature - Tragic Theology A Study of Judges 17-18 PDFIvan_skiNo ratings yet

- The Poetic Structure of Psalm 42-43 SchokelDocument19 pagesThe Poetic Structure of Psalm 42-43 SchokelRyan CookNo ratings yet

- Ecstasy and Intimacy: When the Holy Spirit Meets the Human SpiritFrom EverandEcstasy and Intimacy: When the Holy Spirit Meets the Human SpiritRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- (Frank Holbrook, Leo Van Dolson, Eds.) Issues in R (B-Ok - Xyz)Document235 pages(Frank Holbrook, Leo Van Dolson, Eds.) Issues in R (B-Ok - Xyz)Filipe Veiga100% (2)

- Christian Understandings of Creation: The Historical TrajectoryFrom EverandChristian Understandings of Creation: The Historical TrajectoryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Athanasius (Foundations of Theological Exegesis and Christian Spirituality)From EverandAthanasius (Foundations of Theological Exegesis and Christian Spirituality)Rating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- 00 Theosis and The Doctrine of SalvationDocument49 pages00 Theosis and The Doctrine of SalvationRonnie Bennett Aubrey-Bray100% (7)

- Theology, Prayer And: The Divine OfficeDocument14 pagesTheology, Prayer And: The Divine OfficestjeromesNo ratings yet

- Tending Soul, Mind, and Body: The Art and Science of Spiritual FormationFrom EverandTending Soul, Mind, and Body: The Art and Science of Spiritual FormationGerald L. HiestandRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Trinity among the Nations: The Doctrine of God in the Majority WorldFrom EverandThe Trinity among the Nations: The Doctrine of God in the Majority WorldNo ratings yet

- Chasing the Shadow—the World and Its Times: An Introduction to Christian Natural Theology, Volume 2From EverandChasing the Shadow—the World and Its Times: An Introduction to Christian Natural Theology, Volume 2No ratings yet

- Theosis and The Doctrine of SalvationDocument48 pagesTheosis and The Doctrine of SalvationRonnie Bennett Aubrey-Bray100% (3)

- Theology in Practice: A Beginner's Guide to the Spiritual LifeFrom EverandTheology in Practice: A Beginner's Guide to the Spiritual LifeNo ratings yet

- A Secular Look at The BibleDocument75 pagesA Secular Look at The BibleEdgar NationalistNo ratings yet

- Patristic Soteriology: Three TrajectoriesDocument30 pagesPatristic Soteriology: Three TrajectoriesSancta Maria ServusNo ratings yet

- Bibliotheca Sacra: Professor Jacob Cooper, D.C.L., LL.DDocument28 pagesBibliotheca Sacra: Professor Jacob Cooper, D.C.L., LL.DJavier Allende JulioNo ratings yet

- Karl Rahner - On Grace and SalvationDocument19 pagesKarl Rahner - On Grace and SalvationfesousacostaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Christian WorshipDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Christian Worshipafeehpoam100% (1)

- 25 1 3Document16 pages25 1 3Anonymous JsxeHBNo ratings yet

- Great Cloud of Witnesses: How the Dead Make a Living ChurchFrom EverandGreat Cloud of Witnesses: How the Dead Make a Living ChurchNo ratings yet

- Theological Retrieval for Evangelicals: Why We Need Our Past to Have a FutureFrom EverandTheological Retrieval for Evangelicals: Why We Need Our Past to Have a FutureRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- The Triune Nature of God: Conversations Regarding the Trinity by a Disciples of Christ Pastor/TheologianFrom EverandThe Triune Nature of God: Conversations Regarding the Trinity by a Disciples of Christ Pastor/TheologianNo ratings yet

- Broken Lights and Mended Lives: Theology and Common Life in the Early ChurchFrom EverandBroken Lights and Mended Lives: Theology and Common Life in the Early ChurchRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Enthroned on Our Praise: An Old Testament Theology of WorshipFrom EverandEnthroned on Our Praise: An Old Testament Theology of WorshipRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Denuded Devotion to Christ: The Ascetic Piety of Protestant True Religion in the ReformationFrom EverandDenuded Devotion to Christ: The Ascetic Piety of Protestant True Religion in the ReformationNo ratings yet

- On The Patristic and Post-Patristic' View of Education and SalvationDocument14 pagesOn The Patristic and Post-Patristic' View of Education and SalvationAnonymous uD8YEGVNo ratings yet

- In Dwelling Holy SpiritDocument358 pagesIn Dwelling Holy Spiritforewer2000100% (2)

- Christ and the Created Order: Perspectives from Theology, Philosophy, and ScienceFrom EverandChrist and the Created Order: Perspectives from Theology, Philosophy, and ScienceNo ratings yet

- Cman 092 2 PackerDocument8 pagesCman 092 2 Packermilkymilky9876No ratings yet

- The Philosopher and the Gospels: Jesus Through the Lens of PhilosophyFrom EverandThe Philosopher and the Gospels: Jesus Through the Lens of PhilosophyNo ratings yet

- Studies of Christianity; Or, Timely Thoughts for Religious ThinkersFrom EverandStudies of Christianity; Or, Timely Thoughts for Religious ThinkersNo ratings yet

- Person and Work of Christ: Understanding Jesus: Understanding JesusFrom EverandPerson and Work of Christ: Understanding Jesus: Understanding JesusRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Being the Body of Christ in the Age of ManagementFrom EverandBeing the Body of Christ in the Age of ManagementNo ratings yet

- Ecological Theology(Laudato Si & Laudate Deum) Pope FrancisDocument11 pagesEcological Theology(Laudato Si & Laudate Deum) Pope FrancismertoosNo ratings yet

- Review of Luke Timothy Johnson S ProphetDocument8 pagesReview of Luke Timothy Johnson S ProphetmertoosNo ratings yet

- Exegesis of Psalm 131Document18 pagesExegesis of Psalm 131mertoosNo ratings yet

- NT Exegesis 3-6 ChaptersDocument8 pagesNT Exegesis 3-6 ChaptersmertoosNo ratings yet

- Justice in 4 Social Documents of ChurchDocument12 pagesJustice in 4 Social Documents of ChurchmertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord Fri EpDocument38 pagesDivine Ord Fri EpmertoosNo ratings yet

- How Can We Learn What Veritatis Splendor Has to TeachDocument6 pagesHow Can We Learn What Veritatis Splendor Has to TeachmertoosNo ratings yet

- Verbum in Ecclesia Part 2 of Verbum DominiDocument13 pagesVerbum in Ecclesia Part 2 of Verbum DominimertoosNo ratings yet

- Holy God We Praise Thy NameDocument1 pageHoly God We Praise Thy NamemertoosNo ratings yet

- Ps 51 An Exegesis in MalayalamDocument2 pagesPs 51 An Exegesis in MalayalammertoosNo ratings yet

- Theology of The SacramentsDocument11 pagesTheology of The SacramentsmertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord A Sun np2Document4 pagesDivine Ord A Sun np2mertoosNo ratings yet

- July 21 ReadingsDocument3 pagesJuly 21 ReadingsmertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord A Sat np1Document4 pagesDivine Ord A Sat np1mertoosNo ratings yet

- Ps. 22 An Exegesis in MalayalamDocument4 pagesPs. 22 An Exegesis in MalayalammertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord C Tue NPDocument4 pagesDivine Ord C Tue NPmertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord B Mon NPDocument4 pagesDivine Ord B Mon NPmertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord F Fri NPDocument4 pagesDivine Ord F Fri NPmertoosNo ratings yet

- Divine Ord e Thu NPDocument3 pagesDivine Ord e Thu NPmertoosNo ratings yet

- I'm My Own BookDocument1 pageI'm My Own BookmertoosNo ratings yet

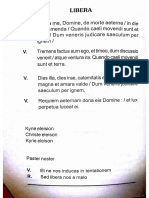

- Libera MeDocument3 pagesLibera MemertoosNo ratings yet

- Antigen Test Request FormDocument2 pagesAntigen Test Request FormmertoosNo ratings yet

- The Kerala Panchayat Raj (Burial and Burning Grounds) Rules, 1998Document7 pagesThe Kerala Panchayat Raj (Burial and Burning Grounds) Rules, 1998mertoosNo ratings yet

- Android Search Telegram ChannelsDocument4 pagesAndroid Search Telegram ChannelsmertoosNo ratings yet

- Veg@Lent 2023Document2 pagesVeg@Lent 2023mertoosNo ratings yet

- Recollection For MeditationDocument5 pagesRecollection For MeditationmertoosNo ratings yet

- Eucharist ReadingsDocument9 pagesEucharist ReadingsmertoosNo ratings yet

- My First Book of Spanish Words by Kudela, Katy RDocument33 pagesMy First Book of Spanish Words by Kudela, Katy Rmertoos50% (2)

- MCQ BRFWDocument37 pagesMCQ BRFWmertoosNo ratings yet

- Jairus' DaughterDocument18 pagesJairus' Daughterapi-281967996No ratings yet

- Method in Determining Wisdom Influence Upon Historical Litera Ture J L CrenshawDocument15 pagesMethod in Determining Wisdom Influence Upon Historical Litera Ture J L CrenshawAto TheunuoNo ratings yet

- Silent ExodusDocument5 pagesSilent Exodus321876No ratings yet

- Translation of Heb 11.1Document4 pagesTranslation of Heb 11.131songofjoyNo ratings yet

- Who Is Addressed in Revelation 18 6 7Document17 pagesWho Is Addressed in Revelation 18 6 7Rupesh SawantyNo ratings yet

- Battle Between Joab and AbnerDocument3 pagesBattle Between Joab and AbnerOtto PecsukNo ratings yet

- Kaiser, Psalm 72 An Historical and Messianic Current Example of Antiochene Hermeneutical TheoriaDocument15 pagesKaiser, Psalm 72 An Historical and Messianic Current Example of Antiochene Hermeneutical TheoriatheoarticlesNo ratings yet

- Sacramental Spirituality Review Bernard HaringDocument3 pagesSacramental Spirituality Review Bernard HaringmertoosNo ratings yet

- The Lion, The Wicked, and The Wonder of It All: Psalm 104 and The Playful GodDocument7 pagesThe Lion, The Wicked, and The Wonder of It All: Psalm 104 and The Playful GodScott DonianNo ratings yet

- The Intermediary World: The Problem in Its Historical SettingDocument11 pagesThe Intermediary World: The Problem in Its Historical SettingEric ZsebenyiNo ratings yet

- Alan Kreider - Testimony As Sharing Hope, A Sermon On Matthew 8 VV 5 A 13Document10 pagesAlan Kreider - Testimony As Sharing Hope, A Sermon On Matthew 8 VV 5 A 13Eliceo Saavedra Rios100% (1)

- Krister Stendahl - Hate, Non-Retaliation and Love (1962)Document14 pagesKrister Stendahl - Hate, Non-Retaliation and Love (1962)Jona ThanNo ratings yet

- Book Review-Jesus The Teacher - A Socio-Rhetorical Interpretation of MarkDocument3 pagesBook Review-Jesus The Teacher - A Socio-Rhetorical Interpretation of MarkJohnPaul DevakumarNo ratings yet

- LIMBURG, J. Sevenfold Structures in The Book of AmosDocument7 pagesLIMBURG, J. Sevenfold Structures in The Book of AmosFilipe AraújoNo ratings yet

- Frey, Sabbath in Egypt? An Examination of Exodus 5Document16 pagesFrey, Sabbath in Egypt? An Examination of Exodus 5anewgiani6288No ratings yet

- 1 Cor 7 - Paul and Permance of MarriageDocument13 pages1 Cor 7 - Paul and Permance of Marriage31songofjoyNo ratings yet

- Quo Vadis Eastern Europe. Religion, State and Society After Communism PDFDocument3 pagesQuo Vadis Eastern Europe. Religion, State and Society After Communism PDFRubenAronicaNo ratings yet

- The First and The LastDocument8 pagesThe First and The LastAlingal CmrmNo ratings yet

- Semeia 18 (1980), The Myth Semantics of GenesisDocument10 pagesSemeia 18 (1980), The Myth Semantics of GenesisKeung Jae LeeNo ratings yet

- Crítica A N.t.wrightDocument19 pagesCrítica A N.t.wrightFilipeGalhardoNo ratings yet

- 1 Cor 9.24-27 - Paul's ArgumentDocument6 pages1 Cor 9.24-27 - Paul's Argument31songofjoyNo ratings yet

- Longman, Psalm98 A Divine Warrior Victory SongDocument9 pagesLongman, Psalm98 A Divine Warrior Victory SongtheoarticlesNo ratings yet

- Terence Fretheim - The Exaggerated God of JonahDocument11 pagesTerence Fretheim - The Exaggerated God of JonahChris Schelin100% (1)

- Women Caught in The Conflict The Culture War Between Traditionalism and Feminism-1Document3 pagesWomen Caught in The Conflict The Culture War Between Traditionalism and Feminism-1Luisa GomezNo ratings yet

- Judgment or Vindication - Heb 10.30Document17 pagesJudgment or Vindication - Heb 10.3031songofjoyNo ratings yet

- Bayer, Oswald. 2003. Law and MoralityDocument15 pagesBayer, Oswald. 2003. Law and MoralitysanchezmeladoNo ratings yet

- 1 Cor 9.19-23Document15 pages1 Cor 9.19-2331songofjoyNo ratings yet