Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Module 17-Academic Script200225070702023333

Module 17-Academic Script200225070702023333

Uploaded by

Knowledge Heist0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views17 pagesThe French New Wave was an influential film movement that emerged in post-World War 2 France. It was characterized by a celebration of the director as an auteur or artist with a unique vision. Young film critics at Cahiers du Cinema developed the theory of auteurism, analyzing directors' styles and arguing they imprinted their films with personal expression. This inspired critics like Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer and others to make low-budget, innovative films that experimented with form and expressed their personal worldviews, launching the New Wave. The movement emphasized experimenting with techniques and paying homage to cinema history through references in their films.

Original Description:

Original Title

Module 17-Academic script200225070702023333

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe French New Wave was an influential film movement that emerged in post-World War 2 France. It was characterized by a celebration of the director as an auteur or artist with a unique vision. Young film critics at Cahiers du Cinema developed the theory of auteurism, analyzing directors' styles and arguing they imprinted their films with personal expression. This inspired critics like Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer and others to make low-budget, innovative films that experimented with form and expressed their personal worldviews, launching the New Wave. The movement emphasized experimenting with techniques and paying homage to cinema history through references in their films.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views17 pagesModule 17-Academic Script200225070702023333

Module 17-Academic Script200225070702023333

Uploaded by

Knowledge HeistThe French New Wave was an influential film movement that emerged in post-World War 2 France. It was characterized by a celebration of the director as an auteur or artist with a unique vision. Young film critics at Cahiers du Cinema developed the theory of auteurism, analyzing directors' styles and arguing they imprinted their films with personal expression. This inspired critics like Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer and others to make low-budget, innovative films that experimented with form and expressed their personal worldviews, launching the New Wave. The movement emphasized experimenting with techniques and paying homage to cinema history through references in their films.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 17

Major Film Movement & The Auteurs

Module 17

The Rise of Nouvelle Vague

Academic script

The Rise of Nouvelle Vague

The French Nouvelle Vague or French New Wave was one

of the two most influential film movements which took

place in post-War Europe, the other being the Italian

Neorealism. If the Italian movement was inherently a

political movement - born out of anti-fascist resistance

movements - which gave birth to a definite aesthetic

paradigm, French New Wave was an aesthetic paradigm

shift with ambivalent political connotations.

The apparent features of both the movement was largely

similar - low-budget filmmaking was explored, shooting

in real locations instead of studio floors, shooting in

natural light conditions using faster stocks, strategies of

narration markedly different from the conventional and

established were features which can be found in both the

movements. Both the movements had a passionate

engagement with the contemporary and tried to present

a distinct national image on the screen; but while the

Italian movement located it in the socio-historical, French

New Wave was more interested in the cultural and the

discursive. While in Neorealism the poor, the proletariat

and the lower-class was given primacy, Parisian youth

got the centrestage in French New Wave.

If we continue with the differences between the Italian

Neorealism and French New Wave, a significant

difference should be the way directorial functions are

imagined in the movement. In neorealism, the style of

the director (and also his world-view) should be

subsumed largely under the umbrella paradigm of the

movement. In other words, if the style and world-view of

a particular director starts to be distinct from that of his

fellow directors, that would definitely begin the end of the

movement. The director’s strategies of non-intervention

into the reality demanded an effacement of the persona,

neorealism demanded acute and systematic observation

of the social reality.

The case is just the obverse in French New Wave. To be

precise, the French movement should not have a broader

umbrella aesthetics because the movement was about

liberating and articulating distinct style, signature and

world-views of individual directors. Therefore, to

understand the French New Wave, it is necessary to

understand the reimagination of the role of the director

as an individuated artist in post-War France.

The term “nouvelle vague” was primarily coined by

Francoise Giroud in the magazine L’Express to describe a

certain youth culture in later 1950s. Later it got

associated with the new cinematic movement.

It was in 1947, Alexandre Astruc wrote an essay titled ‘La

Camera Stylo: Birth of a new Avant-Garde’ where he

spoke of a new artistic tendency emerging in cinema

after the wars - that of considering the cinematic as a

language capable of expressing the individual artist’s

ideas, thoughts and obsessions. The most important

figure of speech in the essay was the metaphor used in

the title - that the camera was equated with the pen

(stylo) had many implications. Firstly, the pen is wielded

by an ‘individual artist’, not by a collective (like in

theater); secondly, the pen is a medium through which

the artist deals with language; thirdly, the pen in writer’s

hand is not restricted to any form (she might write a

poem, a journal entry, a novel, an essay); lastly, the pen

also signifies a relative inexpensive tool.

Each of this implications had significant possibilities which

will be fully explored during the French New Wave. While

the movement will stress on low-budget filmmaking to

lighten commercial baggages to hinder the director’s

expression; the movement will also try to expand the

horizons of feature filmmaking to go beyond character-

centric, plot-driven narratives. But most important was

the concept of the director as the sole expressive artist

‘authoring’ the film through a highly self-conscious,

modernist use of film-language.

That the essay was being correctly speculative of the

future would be vindicated by an influential journal within

a decade. Cahiers du Cinema, spearheaded by the

legendary film-theorist Andre Bazin, became the platform

where a relatively younger group of film-critics

consistently practiced a throughly designed ‘policy’ of

film-viewing which they named ‘politique des auteur’.

This policy - not a ‘theory’ as it will be shortly

misunderstood by Anglophone film critics - maintained

that if a film is a medium of art, then its artistic validity

should be judged through a singular yardstick: if it is

capable of expressing the artist behind it and if it is being

successfully helmed to attribute the artist a distinctive

personality. Thus, their ‘method’ of reading films was -

by default - transformed into an endeavor of ‘reading the

artistic personality’ behind the film-facade.

The policy faced severe criticism from more seasoned

and pragmatic film critics - they were not sure if cinema

can be considered equivalent to more expressive

mediums like literature, painting, music etc. They also

argued that cinema - in its fifth decade of existence - has

been thoroughly defined as a industrial, technology-

intensive medium which is dominantly collective in

nature; therefore, the notion of director as an expressive

individuated artist is too Utopian, according to these

critics. Lastly, the role of the director in this industrial

team is very throughly defined and it is not easy to

conclude that he is the single ‘authoritative’ figure in this

hierarchy, therefore assigning him the only agency is

hugely problematic.

The Cahiers group - comprising names like Francois

Truffaut, Jean-luc Godard, Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol,

Jacques Rivette - who will be in the forefront of Nouvelle

Vague movement within years responded to this criticism

in a more ambitious way, they decided to prove that the

director is the author within an industrial structure which

is the most rigorously hierarchical and therefore can

easily turn to be the most difficult terrain to prove their

policy, in Hollywood.

What can be discerned as their method had implications

in the film movement they will spearhead. They located

the specificity of the medium in its mise-en-scene, they

way a scene is put together; logically, the person who is

responsible for designing the mise-en-scene, i.e. the

director, becomes the cinematic artist. In their reading of

a director’s films, the Cahiers group would then identify

devices used in the designing of mise-en-scenes by a

director which seem unique to him, e.g. tracking shots in

Hitchcock; then they would read how these devices (or

motifs in contents) would recur in the oeuvre of the

filmmaker, what would it mean. In this way, they would

determine the signature, the unique style and the world-

view of the director.

When these critics would turn filmmakers within few

years there craft would follow similar traits, only this time

more self-conscious than implicit. They would hone their

craft to develop unique and idiosyncratic styles and also

use cinema to convey their ideas and world-view.

The Nouvelle Vague also involves a particular relationship

to and awareness of the history of cinema.

This was born out of a peculiar historical situation -

during and before the Second World War, when France

was occupied by German fascists, there was an embargo

on American films. After the liberation and end of the

Vichy era the embargo was lifted and not only current

American films but also those films which were not

released for a decade flooded the Parisian halls. This

simultaneity of a decade or more of American films gave

the French cinephiles a unique insight into history of

American films.

This was also boosted by a major institution - the

Cinematheque Francais or the French national archive

curated by Henri Langlois - whose classification and

opening of the archive to cinephiles gave similar insight

regarding world cinema.

When the critic-turned-filmmakers made their films, they

would constantly refer to the films with an awareness of

the historicity of the cinematic language. Thus, each

filmmaker would - through their quotations and

references - build a personalized canon of films which

would give them an unique identity.

Therefore, the French New Wave filmmakers would

function like advanced critics and readers of cinema

giving birth - after five decades of history of cinema - to

the films of a cinephile generation.

Theoretically, this peculiar way of making films through

references and quotations would give birth to an

intertextual cinema where one text would act like a portal

to a network of other films. Naturally, these engaged

filmmakers would demand a similarly engaged and

cinephilic way of viewing films.

Thus, not only a single film might act as recalling of other

films or genres; even a singular device, e.g. a close-up or

an iris-in, might also consciously recall histories of the

particular devices. In this way, cinematic language

ceased to be a transparent window to reality and turned

into a materiality with its own history. Thus, in French

New Wave films we often have a double-take - a film

would be looking simultaneously looking at both the

social real and the artifice of texts.

Thus, often a director can be identified with his personal

canons of films and filmmakers (identified through their

quotations and references). The Cahiers group -

notorious for their irreverence to senior filmmakers - had

their personal pantheon of respected paternal filmmakers

like Jean Renoir, Jean Rouch, Roberto Rossellini, Robert

Bresson, Jacques Tati, Jean Vigo, Jean-Pierre Mieville,

Ingmar Bergman etc. Thus, in Godard’s films often

cameos by senior filmmakers like Mieville (in Breathless),

Fritz Lang (as himself in Contempt) and Samuel Fuller (as

himself in Pierrot Le Fou) would act as respectful tributes.

The Cahiers group was respectful to many Classical

Hollywood filmmakers, but one can particularly mention

their immense respect and fondness for Orson Welles and

Alfred Hitchcock (with whom Truffaut had a memorable

conversation which was later published as a book).

Another key essay which might be considered as an

prologue to the French New Wave is Francois Truffaut’s

polemical essay titled ‘A Certain Tendency in French

Cinema’. Truffaut was known to be a passionate and

infamously dismissive critic of French cinema (leading to

the barring of his entry to the Cannes Film Festival the

year before he won over the same venue with his first

film). This essay can now be read as a sort of manifesto

to the movement which will follow. It is not directly a

manifesto because it does not envision a possible cinema,

rather it delineates the essayist’s impatience regarding

contemporary French cinema.

These films were often pejoratively called ‘Cinema du

Papa’ (Daddies’ Cinema) or ‘Tradition of Quality’ films by

the cinephiles. Since after the war - among other

infrastructures - the film industries were severely

damaged in Europe, there developed a system of co-

productions among industries of many European

countries. Only thus a certain quality of production could

have been ensured which will generate revenue in more

than one countries. This resulted in a cross-national pool

of technicians but in the cost of national specificities of

films, because often these films would get itself

constricted to lavishly built aristocratic-bourgeois

interiors which might look familiar to audiences of

different nationalities. Truffaut’s critique of these films

can be summarized as the following - keeping in mind

that they desired a cinema where the expressive director

would be supreme

These films are technicians’ films. The films tried to

achieve a set yardstick of cinematography, set-designing,

lighting which were unanimously considered to be

beautiful. Described as ‘glacis de la lumierre’ (cold light),

these look appeared lifeless and inexpressive to the new

cinephiles.

These films were screenwriter’s films. Often, the films

were adapted from recognized literary classics or

bestsellers where the screenwriters only goal is to match

the literary standards of the source materials. Thus, the

artistic goal seemed to be a sort of pre-given and the

purpose of adaptation or interpretation non-existent. The

director merely acts as a translator of the literary

classics. To Truffaut, the literary form of the screenplay

cannot attain the artistic heights of cinematic art, neither

can the literary source claim the quality of the cinematic

product.

On hindsight, one can describe the essay as a strategic

step to delineate a certain vacuum in the contemporary

French scene, that of an expressive personal cinema

where the directorial style and expression would be hold

paramount.

Therefore, when these critics turned into filmmakers

within a few years, there was a deluge of idiosyncratic

and often eccentric films. Francois Truffaut’s first full-

length feature film would therefore dare to attempt

something hitherto not attempted in cinema - an

autobiographical account of the director’s childhood which

also refers to Jean Vigo’s Zero du Conduit. Truffaut’s 400

Blows almost announced the onset of French New Wave,

though historians have traced beginnings to earlier films

by other directors.

Similarly, Jean-luc Godard’s first film was eccentric in an

extreme way, bringing a directorial vision of cinema

almost unseen after the advent of sound cinema.

Breathless was many things simultaneously - a genre film

made in shoestring budget, an essay on cinema which is

also exploring shooting in real locations with available

lighting, a vehicle of the director’s ideas and

contemplations on a number of issues, a tribute to

Hollywood B-movies.

Apart from the critics turned filmmakers of the Cahiers

group, there were also a distinct group of directors -

namely Alain Resnais, Agnes Varda, Jacques Demy, Chris

Marker etc - who were more experienced and

intellectually inclined. The ‘Left Bank’ group, the name

they were often clubbed under, also announced itself

through Resnais’s collaboration with novelist-screenplay

writer Margarit Duras in Hiroshima mon Amour, which

presented a completely different model of

correspondence with literature and cinematic

contemplation.

The French New Wave tacitly exploited the subsidies and

advances issued by the French government for new

filmmakers and presented a mode of production which

was relatively non-conventional. Thus, one filmmaker

might be an actor, writer or assistant to another maker’s

production. Therefore, though the artistic vision would be

firmly ascribed to a single person, the overall making

would present a largely collaborative endeavor. Instead

of hiring studio floors, often a friend’s apartment would

be used. Films would often refer to films made by other

comrade filmmakers, even in the extreme case of

Truffaut referring to Paris nous Appartient, which was still

under production, in his first film.

The French New Wave also rejuvenated cinema by

drawing inspirations from newer sources. When Godard

collaborated with cinematographer Raoul Coutard, the

primary reason was that Coutard was a wartime newsreel

cinematographer, thus having the reflexes and

experience of filming non-fiction quickly under stressful

condition with meager means - a condition which the

filmmaker wished to be in in his first film.

Godard’s infamous myth of shooting without scripts and

New Wave’s legendary methods of improvisation hints at

two different tendencies; while the former attests the

directors zeal towards absolute control - the crew-

members having minimum idea of what is to be shot in

any given schedule, the latter tries to eschew the

rigorous industrial scheduling and planning and not only

emphasizing on spontaneity and liveliness but also a

ready state of mind of the collaborators. There were also

an attempt to stretch the limits of decisiveness and

creativity beyond the production phase, as evident in the

famous use of ‘jump cuts’ in Breathless during the editing

to impart a more suitable rhythm and desperation to the

film.

The term ‘nouvelle vague’ was coined not to describe the

cinematic in particular but to describe an overall new

post-war youth culture in Paris. French New Wave

therefore presented not only a new battalion of

aggressive filmmakers, but also a brand new set of actors

and stars - like Anna Karina, Jeanne Moreau, Jean-Paul

Belmondo, Jean-Pierre Leaud - who brought forth a new

style of cinematic acting and star personas and became

cultural icons of a certain era. But definitely the most

important stars of the movement was the directors,

whose thoroughly personal visions rejuvenated Art

Cinema as the cinema of the ‘Auteurs’ for decades to

come.

While the Italian Neorealism had provided the template

of cinema exploring and re-exploring social realities

hitherto unrepresented or reified, the French New Wave

had been a constant source of inspiration and provider of

methods wherever and whenever an industry has turned

moribund, lacking in ideas and imagination and mired in

rigorous production structures. The New Wave reminds

that cinema must have the ability to articulate concerns

of newer generations of filmmakers while also recalling

forgotten moments in the past when cinema was jubilant

in ideas and executions. Thus, almost all new cinemas till

date has been bearing the legacies of these two

movements in one way or the other.

While French New Wave refreshed cinematic modernism

after the silent avant-gardes of 1920s in its reflexive self-

consciousness and repertoire of devices, critics also finds

postmodernist tendencies in its deliberate mixing of high

and low art, in its simultaneous enthusiasm regarding

pop art on one hand and novelistic contemplation on the

other. But the main achievement of French New Wave is

its ability to expand the scope and devices of cinema

beyond the culturally decided at any moment along with

keeping its means cheaper and meager.

You might also like

- 7000 Codes Xtream IPTV - 2023 VIP Premium Date 8-2023 Group - 6Document195 pages7000 Codes Xtream IPTV - 2023 VIP Premium Date 8-2023 Group - 6rebene9778100% (2)

- Laura Rascaroli - The Essay Film PDFDocument25 pagesLaura Rascaroli - The Essay Film PDFMark Cohen50% (2)

- La Mentira (1998 TV Series) : La Mentira (Lit. Title: The Lie / International Title: Twisted Lies) Is ADocument4 pagesLa Mentira (1998 TV Series) : La Mentira (Lit. Title: The Lie / International Title: Twisted Lies) Is AMargarita SantanaNo ratings yet

- The French New Wave - Chris Darke (4th Ed) PDFDocument28 pagesThe French New Wave - Chris Darke (4th Ed) PDFLefteris MakedonasNo ratings yet

- The French New Wave - Chris Darke (4th Ed)Document28 pagesThe French New Wave - Chris Darke (4th Ed)Kushal BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- French Impressionism (CINEMA)Document14 pagesFrench Impressionism (CINEMA)Anningningning100% (1)

- The Differences Between Neorealism N New WaveDocument2 pagesThe Differences Between Neorealism N New WaveWulan Tri Astuti0% (1)

- Before and After NeorealismDocument15 pagesBefore and After NeorealismGlen NortonNo ratings yet

- A Trail of Fire for Political Cinema: The Hour of the Furnaces Fifty Years LaterFrom EverandA Trail of Fire for Political Cinema: The Hour of the Furnaces Fifty Years LaterJavier CampoNo ratings yet

- FrenchtoamericannewwaveDocument11 pagesFrenchtoamericannewwaveapi-286011720No ratings yet

- Film Film Frexh WaveDocument5 pagesFilm Film Frexh WaveRashiNo ratings yet

- Political Cinema ResearchDocument3 pagesPolitical Cinema ResearchbillylondoninternationalNo ratings yet

- Art FilmDocument10 pagesArt Filmalfredo89No ratings yet

- Down With Cinephilia Long Live Cinephilia and OtheDocument14 pagesDown With Cinephilia Long Live Cinephilia and OthePaolo TizonNo ratings yet

- Το Γαλλικό Νέο Κύμα (revisited)Document11 pagesΤο Γαλλικό Νέο Κύμα (revisited)Georgio PlizopoulosNo ratings yet

- Cinephilia Movies, Love and MemoryDocument239 pagesCinephilia Movies, Love and Memorytint0100% (5)

- UNIT III - Film StudiesDocument6 pagesUNIT III - Film StudiesshutupiqraNo ratings yet

- People Exposed People As Extras Didi HubermanDocument8 pagesPeople Exposed People As Extras Didi Hubermanerezpery100% (1)

- Pierre Bourdieu and The French Sociology of Film ConsumptionDocument13 pagesPierre Bourdieu and The French Sociology of Film ConsumptionCezar GheorgheNo ratings yet

- The Theory in Practice: 4 - CahiersDocument13 pagesThe Theory in Practice: 4 - CahiersAdrián Abril MagallanesNo ratings yet

- Nationalism and the Cinema in France: Political Mythologies and Film Events, 1945-1995From EverandNationalism and the Cinema in France: Political Mythologies and Film Events, 1945-1995No ratings yet

- Filmmaking. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2001.: Uploaded 25 July 2002 1727 WordsDocument9 pagesFilmmaking. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2001.: Uploaded 25 July 2002 1727 WordsEran SaharNo ratings yet

- The Attractions - 2Document74 pagesThe Attractions - 2Mario RighettiNo ratings yet

- The City of Love: ParisDocument55 pagesThe City of Love: ParisDeneme Deneme AsNo ratings yet

- Ubc 2005-0300Document0 pagesUbc 2005-0300WilsonHuntNo ratings yet

- The 1960s: Cahiers Du CinemaDocument24 pagesThe 1960s: Cahiers Du CinemaXUNo ratings yet

- Sobre FRAMEWORKDocument14 pagesSobre FRAMEWORKDavidNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3: The Documentary Genre. Approach and TypesDocument18 pagesChapter 3: The Documentary Genre. Approach and TypesEirini PyrpyliNo ratings yet

- Rohmer LiterarinessDocument117 pagesRohmer Literarinessn v100% (1)

- François Truffaut and La Nouvelle VagueDocument8 pagesFrançois Truffaut and La Nouvelle Vagueveralynn35No ratings yet

- Peter Wollen - The Two Avant-GardesDocument9 pagesPeter Wollen - The Two Avant-Gardesdoragreenissleepy100% (2)

- Williams, Raymond - When Was ModernismDocument4 pagesWilliams, Raymond - When Was ModernismLea TomićNo ratings yet

- (Walter Donohue) Projections 9 French Film-MakersDocument204 pages(Walter Donohue) Projections 9 French Film-MakersFabián UlloaNo ratings yet

- Film Movements: Mazidul Islam Lecturer, Mass Communication and Journalism Discipline, Khulna University Khulna-9208Document17 pagesFilm Movements: Mazidul Islam Lecturer, Mass Communication and Journalism Discipline, Khulna University Khulna-9208Sudipto saha Topu100% (1)

- French Cinema Week 5Document10 pagesFrench Cinema Week 5filmstudiesffNo ratings yet

- Hollywood Theory, Non-Hollywood PracticeDocument42 pagesHollywood Theory, Non-Hollywood PracticeJosé Luis Caballero MartínezNo ratings yet

- The End of History Through The Disclosure of Fiction: Indisciplinarity in Miguel Gomes'S Tabu (2012)Document30 pagesThe End of History Through The Disclosure of Fiction: Indisciplinarity in Miguel Gomes'S Tabu (2012)Esteban BrenaNo ratings yet

- rp11 Interview Filmpopularmemory Foucault PDFDocument6 pagesrp11 Interview Filmpopularmemory Foucault PDFemmanuel santoyo rioNo ratings yet

- From Vues To EthnofictionDocument50 pagesFrom Vues To EthnofictionRafaDevillamagallónNo ratings yet

- Global Neorealism: The Transnational History of a Film StyleFrom EverandGlobal Neorealism: The Transnational History of a Film StyleNo ratings yet

- Amad, Paula-Cine-ethnographyDocument5 pagesAmad, Paula-Cine-ethnographyoscarguarinNo ratings yet

- Cinema and Mediation of Everyday Life in 1940s and 1950s SpainDocument24 pagesCinema and Mediation of Everyday Life in 1940s and 1950s SpainaarmherNo ratings yet

- Desires for Reality: Radicalism and Revolution in Western European FilmFrom EverandDesires for Reality: Radicalism and Revolution in Western European FilmNo ratings yet

- The New Extremism - Representation of Violence in The New French ExtremismDocument10 pagesThe New Extremism - Representation of Violence in The New French Extremismtorugobarreto5794No ratings yet

- La Politique Des Auteurs (Part One)Document15 pagesLa Politique Des Auteurs (Part One)rueda-leonNo ratings yet

- Asian CinemaDocument66 pagesAsian CinemanutbihariNo ratings yet

- FMovemntsDocument48 pagesFMovemntsSherana MehroofNo ratings yet

- Anti Anti-FidelityDocument17 pagesAnti Anti-FidelityDorotheaBrookeNo ratings yet

- P. Pająk, Early 21st - Century Serbian Exploitation CinemaDocument20 pagesP. Pająk, Early 21st - Century Serbian Exploitation CinemaXDNo ratings yet

- Cauwenberge Cinema VeriteDocument13 pagesCauwenberge Cinema VeriteflorenciacolomboNo ratings yet

- Award Wining FilmsDocument5 pagesAward Wining FilmsFriuli VeneziaNo ratings yet

- The International Impact of Futurism: Absorptions, Assimilations, Adaptations Günter BerghausDocument12 pagesThe International Impact of Futurism: Absorptions, Assimilations, Adaptations Günter BerghauscaptainfreakoutNo ratings yet

- Unraveling The Ethnographic Encounter - Institutionalization and Scientific Tourism in TheDocument17 pagesUnraveling The Ethnographic Encounter - Institutionalization and Scientific Tourism in ThekamtelleNo ratings yet

- The Battle of The Sexes in French Cinema, 1930-1956 by Noël BurchDocument15 pagesThe Battle of The Sexes in French Cinema, 1930-1956 by Noël BurchDuke University PressNo ratings yet

- The Film Essays Writing With The Movie CameraDocument5 pagesThe Film Essays Writing With The Movie CameraŞtefan-Adrian RusuNo ratings yet

- Spanish Cinema ShantadiaDocument32 pagesSpanish Cinema Shantadiadonnie_dunnNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument17 pagesRetrieveandreadelascasas25No ratings yet

- The Cinema of Economic MiraclesDocument222 pagesThe Cinema of Economic MiraclesAfece100% (1)

- District Wise MrThiruvizha Mentors - Engg, Arts & Science Colleges, Polytechnic, ITIs - 2023Document2 pagesDistrict Wise MrThiruvizha Mentors - Engg, Arts & Science Colleges, Polytechnic, ITIs - 2023iedpNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5Document7 pagesLesson 5Kevin SabateNo ratings yet

- Esio Trot by Roald DahlDocument28 pagesEsio Trot by Roald DahlAngela Markovska50% (2)

- Crossdressing and Bad Marriages Jacob Moffat EssayDocument34 pagesCrossdressing and Bad Marriages Jacob Moffat EssayjakeNo ratings yet

- A Companion To Federico Fellini Frank Burke Full ChapterDocument67 pagesA Companion To Federico Fellini Frank Burke Full Chaptersamuel.begley816100% (9)

- 电影《霍尔斯》影评Document6 pages电影《霍尔斯》影评cjcnpvse100% (1)

- Agatha Christie-The Symbol of Literature: "Elena Cuza" National CollegeDocument13 pagesAgatha Christie-The Symbol of Literature: "Elena Cuza" National CollegeAsd FghNo ratings yet

- Bamanpukur Humayun Kabir Mahavidyalaya: AssignmentDocument2 pagesBamanpukur Humayun Kabir Mahavidyalaya: AssignmentAnupam NaskarNo ratings yet

- American Cinema American CultureDocument7 pagesAmerican Cinema American CultureSyed Faisal MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Cinema Technique: Adding Citations To Reliable Sources RemovedDocument2 pagesCinema Technique: Adding Citations To Reliable Sources RemovedKishor RaiNo ratings yet

- Satire Cloze NotesDocument4 pagesSatire Cloze Notesapi-439626674No ratings yet

- Network Hospital List - New India Assurance Co. LTDDocument12 pagesNetwork Hospital List - New India Assurance Co. LTDHasitha mNo ratings yet

- Cca Student Council Up - 0 - 0Document4 pagesCca Student Council Up - 0 - 0soumyaranjansahoo7008No ratings yet

- Disney MoviesDocument9 pagesDisney MoviesClaireNo ratings yet

- Youve Got A Friend in MeDocument2 pagesYouve Got A Friend in MeSamuel oliveiraNo ratings yet

- CLCS 2214-Mechanics of FilmDocument5 pagesCLCS 2214-Mechanics of FilmMeow moewkNo ratings yet

- 28 Horror Classics of The 1970'sDocument3 pages28 Horror Classics of The 1970'sAnonymous sQ9wLhhZNo ratings yet

- High Court of Judicature at AllahabadDocument44 pagesHigh Court of Judicature at AllahabadAkanksha DubeyNo ratings yet

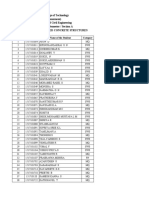

- Group 7 Excel QuestionsDocument16 pagesGroup 7 Excel QuestionsSIMRAN SHOKEENNo ratings yet

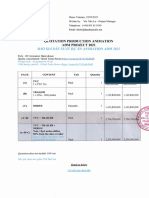

- Quotation DeeDee-Animation ADM 2021-SignedDocument4 pagesQuotation DeeDee-Animation ADM 2021-SignedTân PiNo ratings yet

- Contemporary - Westerns - Film - and - Television (Part - II - New - Wests - Old - Stories)Document80 pagesContemporary - Westerns - Film - and - Television (Part - II - New - Wests - Old - Stories)Ana Laura BochicchioNo ratings yet

- Prestress Name ListDocument6 pagesPrestress Name ListsavithaNo ratings yet

- Presentation Film "Forsazh" Prepared A Student of 11th Grade Zotova MariaDocument20 pagesPresentation Film "Forsazh" Prepared A Student of 11th Grade Zotova MariaВікторія КорнієцьNo ratings yet

- Good Read PH Ebooks List (6.12.2020)Document27 pagesGood Read PH Ebooks List (6.12.2020)Christopher LopezNo ratings yet

- Subhash Pipeline JuneDocument6 pagesSubhash Pipeline JuneAbhishek KesarwaniNo ratings yet

- Gnomeo and JulietDocument2 pagesGnomeo and JulietFikri DelayotaNo ratings yet

- Ulab 1122 (Essay) - Ahmad AmalludinDocument3 pagesUlab 1122 (Essay) - Ahmad AmalludinAmal AmranNo ratings yet