Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2001 Lynn-The Myth of The Bureaucratic Paradigm What Traditional Public Administration Really Stood For

2001 Lynn-The Myth of The Bureaucratic Paradigm What Traditional Public Administration Really Stood For

Uploaded by

Damar AdhyCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Offer LetterDocument1 pageOffer LetterSatya50% (2)

- 06 - The Study of Public Administration in PerspectiveDocument36 pages06 - The Study of Public Administration in PerspectiveHazeleen Mae M. Martinez-Urma100% (6)

- Bevir, Marc. A Theory of GovernanceDocument277 pagesBevir, Marc. A Theory of Governancetocustodio6910100% (1)

- Sample Offer LetterDocument1 pageSample Offer LetterKhaliqur rahmanNo ratings yet

- Eldersveld, Political Parties (Review)Document5 pagesEldersveld, Political Parties (Review)GonzaloNo ratings yet

- Overview PADocument61 pagesOverview PALalit SinghNo ratings yet

- Methodologies in Action ResearchDocument21 pagesMethodologies in Action Researchshweta2204No ratings yet

- The Language of Public Administration: Bureaucracy, Modernity, and PostmodernityFrom EverandThe Language of Public Administration: Bureaucracy, Modernity, and PostmodernityNo ratings yet

- What Tradition PA Stood ForDocument17 pagesWhat Tradition PA Stood ForRabiaNo ratings yet

- The Myth of Bureaucratic ParadigmDocument31 pagesThe Myth of Bureaucratic ParadigmSreekanth ReddyNo ratings yet

- Thernborn 1971 - What Does Ruling Class DoDocument20 pagesThernborn 1971 - What Does Ruling Class DoDiego Alonso Sánchez FlórezNo ratings yet

- Sir Jacs Report Refugio MolinosDocument56 pagesSir Jacs Report Refugio MolinosCharmz DynliNo ratings yet

- Politics Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesPolitics Literature Reviewgwjbmbvkg100% (1)

- Bahan Tugas 1 Historical TrendsDocument20 pagesBahan Tugas 1 Historical TrendsSteven SitompulNo ratings yet

- Bureaucracy in Modern Society (Peter M. Blau)Document127 pagesBureaucracy in Modern Society (Peter M. Blau)MUHAMMAD IQBALNo ratings yet

- Institution For Better LifeDocument11 pagesInstitution For Better LifeJoseph Ryan MarcelinoNo ratings yet

- The Thermidor of The Progressives: Managerialist Liberalism's Hostility To Decentralized OrganizationDocument48 pagesThe Thermidor of The Progressives: Managerialist Liberalism's Hostility To Decentralized OrganizationMimi BobekuninNo ratings yet

- Public AdministrationDocument8 pagesPublic AdministrationTowseef ShafiNo ratings yet

- Dobel, Patrick J. The Corruption of A StateDocument17 pagesDobel, Patrick J. The Corruption of A StateMarcos RobertoNo ratings yet

- Haste (2004) Constructing The CitizenDocument29 pagesHaste (2004) Constructing The CitizenaldocordobaNo ratings yet

- Neoliberalism - A - Foucauldian - PerspectiveDocument16 pagesNeoliberalism - A - Foucauldian - PerspectiveGracedy GreatNo ratings yet

- Charismatic AuthorityDocument11 pagesCharismatic AuthorityAndrea TockNo ratings yet

- PostindustrialSociety SocWorkDocument6 pagesPostindustrialSociety SocWorkcicoc6cNo ratings yet

- American Business, Public Policy, Case-Studies, and Political TheoryDocument29 pagesAmerican Business, Public Policy, Case-Studies, and Political TheoryGutenbergue Silva100% (1)

- Material Designs: Engineering Cultures and Engineering States Ireland 1650 1900Document40 pagesMaterial Designs: Engineering Cultures and Engineering States Ireland 1650 1900Robert CosNo ratings yet

- Lesson: Historical Foundation of Public AdministrationDocument4 pagesLesson: Historical Foundation of Public AdministrationCyj Kianj C. SoleroNo ratings yet

- Whta Happen To Pub Oic Administration Governance Everywhere Frederickson OkokokDocument36 pagesWhta Happen To Pub Oic Administration Governance Everywhere Frederickson OkokokRizalNo ratings yet

- Ethics in Politics. A Review and Synthesis of The Literature Ledivina V. Carino 1995 PDFDocument24 pagesEthics in Politics. A Review and Synthesis of The Literature Ledivina V. Carino 1995 PDFliezelle ngolab talanganNo ratings yet

- What's So Post About The Post-Secular? Mark Redhead California State University, FullertonDocument40 pagesWhat's So Post About The Post-Secular? Mark Redhead California State University, Fullerton123prayerNo ratings yet

- !dean State Phobia PDFDocument20 pages!dean State Phobia PDFFernando FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Reforming Democracies: Six Facts About Politics That Demand a New AgendaFrom EverandReforming Democracies: Six Facts About Politics That Demand a New AgendaNo ratings yet

- Emotional LifeDocument19 pagesEmotional LifeindocilidadreflexivaNo ratings yet

- Project MUSE - The Constructivist Turn in International Relations Theory PDFDocument27 pagesProject MUSE - The Constructivist Turn in International Relations Theory PDFTharanya AruNo ratings yet

- Nhops Chapter 1: I. Political Science As A DisciplineDocument11 pagesNhops Chapter 1: I. Political Science As A DisciplineNicoleMendozaNo ratings yet

- Cunningham - Ideology, History and Political AffectDocument14 pagesCunningham - Ideology, History and Political AffectMiguel Ángel Cabrera AcostaNo ratings yet

- Non Decisions and PowerDocument12 pagesNon Decisions and PowerRobert De Witt100% (1)

- VILE MJC, Constitutionalism and The Separation of Powers, 1998Document468 pagesVILE MJC, Constitutionalism and The Separation of Powers, 1998andresabelrNo ratings yet

- WP 01 24Document16 pagesWP 01 24Kristine De Leon DelanteNo ratings yet

- Postmodern Public AdministrationDocument7 pagesPostmodern Public AdministrationMuhammad AsifNo ratings yet

- The Nonsense and Non-Science of Political Science - A PoliticallyDocument32 pagesThe Nonsense and Non-Science of Political Science - A PoliticallyYuvragi DeoraNo ratings yet

- (2.1 1) Max Weber Power and DominationDocument9 pages(2.1 1) Max Weber Power and DominationJahnavi ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Vi̇ze Ödev KonularinizDocument4 pagesVi̇ze Ödev KonularinizkcbysevnurNo ratings yet

- Public Administration Theory WikipediaDocument7 pagesPublic Administration Theory WikipediaPswd MisorNo ratings yet

- J Public Adm Res Theory-1999-Raadschelders-281-304 - A Choerent Framework For The Study Os Public AdministrationDocument24 pagesJ Public Adm Res Theory-1999-Raadschelders-281-304 - A Choerent Framework For The Study Os Public AdministrationAntonio LisboaNo ratings yet

- NPA EpathasalaDocument21 pagesNPA Epathasalagugoloth shankarNo ratings yet

- Separation of Power in Uk PDFDocument245 pagesSeparation of Power in Uk PDFJackson LoceryanNo ratings yet

- Subject: Political Science I Course: Ba LLB Semester I Lecturer: Ms. Deepika Gahatraj Module: Module Ii, Approaches To Political ScienceDocument4 pagesSubject: Political Science I Course: Ba LLB Semester I Lecturer: Ms. Deepika Gahatraj Module: Module Ii, Approaches To Political SciencePaloma WatsonNo ratings yet

- Carlo Miguel Vazquez Theory in PADocument3 pagesCarlo Miguel Vazquez Theory in PAZarina VazquezNo ratings yet

- The Corruption of A State: American Political Science Association September 1978Document22 pagesThe Corruption of A State: American Political Science Association September 1978takeone123No ratings yet

- Introduction To Political InstitutionsDocument3 pagesIntroduction To Political Institutionsgamlp2023-6311-78968No ratings yet

- The Constructivist Turn in International Relations Theory: Jeffrey T. CheckelDocument19 pagesThe Constructivist Turn in International Relations Theory: Jeffrey T. Checkelain_94No ratings yet

- Aquinas and Christian AristotelianismDocument46 pagesAquinas and Christian AristotelianismCharles MorrisonNo ratings yet

- Power in Global GovernanceDocument32 pagesPower in Global GovernanceErtaç ÇelikNo ratings yet

- Liberalism WorkingDocument53 pagesLiberalism WorkingMohammad ShakurianNo ratings yet

- Simon Gunn Hisotira UrbanasDocument6 pagesSimon Gunn Hisotira UrbanasJorge CondeNo ratings yet

- NIEZEN, Ronald - Anthropological Approaches To PowerDocument10 pagesNIEZEN, Ronald - Anthropological Approaches To PowerAnonymous OeCloZYzNo ratings yet

- 01 Public AdministrationDocument74 pages01 Public AdministrationChristian ErrylNo ratings yet

- Journal of Public and Nonprofit AffairsDocument57 pagesJournal of Public and Nonprofit AffairsmahadiNo ratings yet

- CJ v39n3 13Document7 pagesCJ v39n3 13zahraa.jamal2020No ratings yet

- 6 - LOWI, Theodore J. American Business, Public Policy, Case-Studies, and Political Theory - 1964Document29 pages6 - LOWI, Theodore J. American Business, Public Policy, Case-Studies, and Political Theory - 1964Diego PrataNo ratings yet

- 2008 Demir-The Politics-Administration Dichotomy An Empirical Search For Correspondence Between Theory and PracticeDocument17 pages2008 Demir-The Politics-Administration Dichotomy An Empirical Search For Correspondence Between Theory and PracticeDamar AdhyNo ratings yet

- 1983 Rosenbloom-Public Administration Theory and The Separation of PowersDocument10 pages1983 Rosenbloom-Public Administration Theory and The Separation of PowersDamar AdhyNo ratings yet

- The "New Public Management" in The 1980S: Variations On A Theme'Document17 pagesThe "New Public Management" in The 1980S: Variations On A Theme'Fadhil Zharfan AlhadiNo ratings yet

- 4 1 Origin and Theoretical BasisDocument25 pages4 1 Origin and Theoretical BasisShahid Farooq100% (1)

- Two Stage Open Book GuidanceDocument62 pagesTwo Stage Open Book GuidanceMark Aspinall - Good Price CambodiaNo ratings yet

- 3.performance Budgeting Refers To A Budget in Terms Of: BenchmarkDocument3 pages3.performance Budgeting Refers To A Budget in Terms Of: BenchmarkUsama TariqNo ratings yet

- YES Prosperity Credit Card MITC - 14052021Document8 pagesYES Prosperity Credit Card MITC - 14052021Prinshu TrivediNo ratings yet

- Electricity Meter Conversion Process - BESCOM PDFDocument22 pagesElectricity Meter Conversion Process - BESCOM PDFsriraman8550% (2)

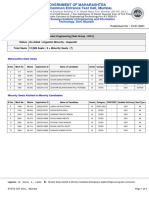

- 3209 - K J Somaiya Institute of Engineering and Information Technology, Sion, MumbaiDocument6 pages3209 - K J Somaiya Institute of Engineering and Information Technology, Sion, Mumbaisarcastic chhokreyNo ratings yet

- Advertisement Police ConstableDocument1 pageAdvertisement Police ConstableHussain AhmadNo ratings yet

- All The Fields Are Mandatory : Employee Application FormDocument9 pagesAll The Fields Are Mandatory : Employee Application Formkavitha221No ratings yet

- Moot Proposition - AUMP National Virtual Moot Court Competition, 2020 PDFDocument3 pagesMoot Proposition - AUMP National Virtual Moot Court Competition, 2020 PDFDakshita DubeyNo ratings yet

- (Rajasthan) / (2022) 447 ITR 698 (Rajasthan) (29-06-2022)Document6 pages(Rajasthan) / (2022) 447 ITR 698 (Rajasthan) (29-06-2022)rigiyanNo ratings yet

- Framework Agreements PDFDocument11 pagesFramework Agreements PDFSaji VarkeyNo ratings yet

- Statement of Assests 2012Document3 pagesStatement of Assests 2012Mark Anthony S. MoralesNo ratings yet

- Tiger Airways Booking Confirmation - N435BLDocument2 pagesTiger Airways Booking Confirmation - N435BLTommy PhanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document16 pagesChapter 3greenapl01No ratings yet

- RELAY InterlockingDocument14 pagesRELAY InterlockingYadwendra YadavNo ratings yet

- Alice Blue Financial Services (P) LTD: Name of The Client: UCC & Client CodeDocument2 pagesAlice Blue Financial Services (P) LTD: Name of The Client: UCC & Client CodeKulasekara PandianNo ratings yet

- Short Notes IAS CS365 2021 Volume 1Document15 pagesShort Notes IAS CS365 2021 Volume 1Editing WorkNo ratings yet

- Financial PlaningDocument14 pagesFinancial PlaningJuzer JiruNo ratings yet

- ,investment PPT SLU Chapters v-VI-1Document52 pages,investment PPT SLU Chapters v-VI-1Louat LouatNo ratings yet

- Tiket PesawatDocument2 pagesTiket PesawatWahyu FatriansaNo ratings yet

- Credit PolicyDocument13 pagesCredit PolicyUDAYNo ratings yet

- Titile Clearance Report For S. No. 583 of Village PakhajanDocument7 pagesTitile Clearance Report For S. No. 583 of Village PakhajanAvani ShahNo ratings yet

- Corporation LawDocument9 pagesCorporation LawDEBRA L. BADIOLA-BRACIANo ratings yet

- London Achivement 2023 Invi 2023Document4 pagesLondon Achivement 2023 Invi 2023Leo PraveenNo ratings yet

- Guidelines On The Use of Virtual Store For The Procurement of CSEDocument6 pagesGuidelines On The Use of Virtual Store For The Procurement of CSEJenelyn DomalaonNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 04-Jan-2024Document11 pagesAdobe Scan 04-Jan-2024deeptiarya127No ratings yet

- SPSA Overseas Bank Form UpdatedDocument1 pageSPSA Overseas Bank Form UpdatedsyedNo ratings yet

- M3 Shifa 2021-23 PracticeDocument5 pagesM3 Shifa 2021-23 PracticeSetul ShethNo ratings yet

- Cadre and Recruitment RulesDocument170 pagesCadre and Recruitment Rulessatheesh_srvNo ratings yet

2001 Lynn-The Myth of The Bureaucratic Paradigm What Traditional Public Administration Really Stood For

2001 Lynn-The Myth of The Bureaucratic Paradigm What Traditional Public Administration Really Stood For

Uploaded by

Damar AdhyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2001 Lynn-The Myth of The Bureaucratic Paradigm What Traditional Public Administration Really Stood For

2001 Lynn-The Myth of The Bureaucratic Paradigm What Traditional Public Administration Really Stood For

Uploaded by

Damar AdhyCopyright:

Available Formats

The Myth of the Bureaucratic Paradigm: What Traditional Public Administration Really

Stood for

Author(s): Laurence E. Lynn, Jr.

Source: Public Administration Review , Mar. - Apr., 2001, Vol. 61, No. 2 (Mar. - Apr.,

2001), pp. 144-160

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the American Society for Public Administration

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/977447

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Wiley and American Society for Public Administration are collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to Public Administration Review

This content downloaded from

202.43.93.30 on Wed, 09 Aug 2023 08:25:32 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Laurence E. Lynn Jr.

University of Chicago

The Myth of the Bureaucratic Paradigm: What

Traditional Public Administration Really Stood For

For a decade, public administration and management literature has featured a riveting story: the

transformation of the field's orientation from an old paradigm to a new one. While many doubt

claims concerning a new paradigm-a New Public Management-few question that there was an

old one. An ingrained and narrowly focused pattern of thought, a "bureaucratic paradigm," is

routinely attributed to public administration's traditional literature. A careful reading of that litera-

ture reveals, however, that the bureaucratic paradigm is, at best, a caricature and, at worst, a

demonstrable distortion of traditional thought that exhibited far more respect for law, politics,

citizens, and values than the new, customer-oriented managerialism and its variants. Public ad-

ministration as a profession, having let lapse the moral and intellectual authority conferred by its

own traditions, mounts an unduly weak challenge to the superficial thinking and easy answers of

the many new paradigms of governance and public service. As a result, literature and discourse

too often lack the recognition that reformers of institutions and civic philosophies must show how

the capacity to effect public purposes and accountability to the polity will be enhanced in a man-

ner that comports with our Constitution and our republican institutions.

We can safely pronounce that the true test of a good government is its aptitude and tendency to

produce a good administration.

-Alexander Hamilton

The student of administration must ... concern himself with the history of his subject, and will gain

a real appreciation of existing conditions and problems only as he becomes familiar with their

background.

-Leonard D. White'

Introduction2

For nearly a decade, public administration and manage- when the old habits and their brainchild, "bureaucracy,'"5

ment literature has featured a riveting story: the transfor- began to crumble under the forces of global change.

mation of the field's orientation from an old paradigm to a Ironically, the traditional paradigm now under attack was

new one.3 While many in public administration doubt that declared dead more than 50 years ago by some of public

there is a new paradigm4-a "New Public Management"

(Pollitt 2000)-few doubt that there was an old one. Vari- Laurence E. Lynn Jr. is the Sydney Stein, Jr., Professor of Public Manage-

ment in the Irving B. Harris Graduate School of Public Policy Studies and

ously termed the "bureaucratic paradigm," the "old ortho-

the School of Social Service Administration at the University of Chicago.

doxy," the "old-time religion," or simply "traditional pub-

His most recent research has focused on theories, models, methods, and

lic administration," an ingrained and narrowly focused data for the empirical study of governance and public management. Gov-

ernance and Performance: New Perspectives, which he coedited with

pattern of thought is routinely attributed to public Carolyn J. Heinrich, was recently published by Georgetown University Press.

administration's scholars and practitioners from the publi- A companion volume, Improving Governance: A New Logic for Research,

which he coauthored with Heinrich and Carolyn J. Hill, is forthcoming.

cation of Woodrow Wilson's 1887 essay until the 1990s,E-mail: lynn@midway.uchicago.edu.

144 Public Administration Review * March/April 2001, Vol. 61, No. 2

This content downloaded from

202.43.93.30 on Wed, 09 Aug 2023 08:25:32 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

administration's own intellectual leaders. A profession that Relying on literature is not altogether satisfactory: Authors

has virtually abandoned its traditions is unlikely to defend are not always clear or consistent, and differing interpreta-

them later. From my vantage point in an adjacent profes- tions of their views are possible. A thorough reconsidera-

sion, this state of affairs seems odd. A careful reading of tion ought to include a sociological analysis of thought

the traditional literature reveals that the "old orthodoxy" and practice. The historian Karl (1976) suggests that the

is, at best, a caricature and, at worst, an outright distortion popularity of a particular work or idea may owe as much

of traditional thought. The caricature better depicts the to one's affection for the author or to the prestige an au-

views of the judges, legislators, the increasingly powerful thor confers on the field than to its intellectual merit. In-

business community, and urban professional elites who tramural rivalries of a personal or professional nature doubt-

have shaped the emerging administrative state than of the less play a role in the way ideas have been selected or

profession's scholars, who have supplied broader, more rejected, but that is a subject for another essay.

thoughtful perspectives on practical issues of state build-

ing based on their grasp of Constitutional and democratic

theory and values.

What Is the Traditional Paradigm?

In this article, I first identify those habits of thought Public administration literature contains both retrospec-

that are attributed to traditional public administration. Next,tive accounts of traditional thinking and summaries of such

I address the questions: How did the traditional public ad- thinking found in the traditional literature itself.

ministration mind actually work? Does the "old orthodoxy"

shoe fit? I conclude with comments about the consequences Retrospective Views

of a profession's being unduly careless of its past. Retrospective critics of traditional thinking tend to cite

In undertaking this analysis, several ideas have helped relatively few sources, so it is not always clear whose hab-

to bring a sprawling, heterodox literature into clearer fo- its of mind are at issue. The wellsprings of tradition appar-

cus. Gerald Garvey (1995) succinctly summarizes the di- ently are to be found primarily in Woodrow Wilson's fa-

lemma of democratic administration as follows: "Admin- mous 1887 lecture, in the works of Frederick Taylor, Max

istrative action in any political system, but especially in a Weber, and Luther Gulick, and in the report of the

democracy, must somehow realize two objectives simul- President's Committee on Administrative Management-

taneously. It is necessary to construct and maintain admin- the Brownlow Report (1937). Less widely known authors

istrative capacity, and it is equally necessary to control it such as Frank J. Goodnow, Leonard D. White, and W. F.

in order to ensure the responsiveness of the public bureau- Willoughby are cited only occasionally.6

cracy to higher authority" (87). Herbert Kaufman (1956) The assault on traditional thinking began with the well-

saw administrative institutions as having been organized known critiques of scientific principles of administration

and operated in pursuit, successively, of three values: rep- by Herbert A. Simon and Robert A. Dahl (Simon 1946,

resentativeness, neutral competence, and executive lead- 1947; Dahl 1947). Their criticisms-that such principles

ership. "The shift," he says, "from one to another gener- were inconsistent and unscientific-were quickly endorsed

ally appears to have occurred as a consequence of the and embellished by mainstream public administrationists,

notably Dwight Waldo and Wallace Sayre. As a result, a

difficulties encountered in the period preceding the change"

(1057). Barry Karl (1976) notes the consequences of the new, revisionist interpretation of traditional thinking be-

American commitment to democratic compromise. Re- came the conventional wisdom in the profession.7

forms, he argues "tended to institutionalize defeated op- Waldo's view was unequivocal. In The Administrative

positions.... The result is often to sustain in the new ad- State (1948), he subjected orthodoxy to devastating criti-

ministrative structure ... the old opposition and to give cism: "The indictment against public administration can

that opposition a lifeline to continuity" (495). Finally, ac- only be that, at the theoretical level, it has contributed little

cording to James Morone (1990), "The institutions de- to the 'solution' or even the systematic statement of [fun-

signed to enhance democracy expand the scope and au- damental] problems" (101), producing instead "a spate of

shallow and spurious answers" (102). Public administra-

thority of the state, especially its administrative capacity.

A great irony propels American political development: the he concluded, "is only now freeing itself from a strait

tion,

search for more direct democracy builds up the bureau- jacket of its own devising-the instrumentalist philoso-

cracy" (1). Regimes do not simply succeed one another; phy of the politics-administration formula-that has lim-

rather, institutions, ideas, and values are woven into theited its breadth and scope" (208). "[S]ince publication of

complex institutional fabric that constitutes democratic the Papers [on the Science of Administration] in 1937,"

governance. Waldo wrote in 1961 (see also Gulick and Urwick [1937]),

My argument is based on a selective reconsideration of "a generation of younger students have demolished the

the literature, not the practice of public administration. classical theory, again and again; they have uprooted it,

The Myth of the Bureaucratic Paradigm 145

This content downloaded from

202.43.93.30 on Wed, 09 Aug 2023 08:25:32 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

threshed it, thrown most of it away. By and large, the criti- amount of resources it controls and by the tasks it per-

cisms of the new generation have been well-founded. In forms; controls costs; sticks to routine; fights for turf; in-

many ways the classical theory was crude, presumptuous, sists on following standard procedures; announces poli-

incomplete-wrong in some of its conclusions, naive in cies and plans; and separates the work of thinking from

its scientific methodology, parochial in its outlook" (220). that of doing (8-9).

In 1968, Waldo insisted that postwar intellectual challenges In David Osborne and Ted Gaebler's immensely influ-

had "brought public administration to the point of crisis, ential Reinventing Government (1992), they argued that,

of possible collapse and disintegration" (4), a viewpoint "American society embarked on a gigantic effort to con-

echoed by Vincent Ostrom in 1973. Waldo's critique has trol what went on inside government-to keep the politi-

been accepted as definitive. "[T]o the best of my memory,"cians and bureaucrats from doing anything that might en-

said Frank Marini, "the terms 'orthodox public adminis- danger the public interest or purse.... In attempting to

tration' and 'politics-administration dichotomy' appear first

control virtually everything, we became so obsessed with

in Waldo's statements (and the import of these concepts dictating how things should be done-regulating the pro-

and their influence upon our field has been profound if notcess, controlling the inputs-that we ignored the outcomes,

always obvious)" (1993, 412).8 the results" (14). Bureaucratic government had been ap-

Sayre (1951, 1958) further stigmatized traditional pub- propriate, Osborne and Gaebler said, for the conditions that

lic administration with his reference to "the high noon of prevailed until roughly the 1960s and 1970s. But those

orthodoxy," achieved with the 1937 publication of Gulick conditions have been swept away, and new forms of gov-

and Urwick's Papers and the Brownlow Report. In Sayre's ernance have begun to emerge, first at the local level, then

view, the underlying orthodoxy had first been codified in more broadly.'0

Leonard White's Introduction to the Study of Public Ad- The Barzelay-Osborne-Gaebler line of argument has

ministration (1926) and in W. F. Willoughby's Principles caught on with many both inside and outside of public

of Public Administration (1927), which espoused, accord-administration. From the policy schools, Mark Moore

ing to Sayre, "a closely knit set of values, confidently and (1995), dismissing traditional public administration as

incisively presented" (1951, 1): the politics-administra- merely "politically neutral competence," asserted that

tion dichotomy, scientific management, the executive bud-

... [T]he classic tradition of public administration

get, scientific personnel management, neutral competence,

does not focus a manager's attention on questions

and control by administrative law. Sayre, like Waldo, de-

of purpose and value or on the development of le-

clared these values obsolete and applauded the field's

gitimacy and support. The classic tradition assumes

movement toward heterodoxy.9 that these questions have been answered in the de-

In the early 1970s, the public policy schools' pro- velopment of the organization's legislative or policy

genitors, perhaps unaware that traditional doctrine was mandate ... managers must pursue the downward-

already widely regarded as dead and without intellec- and inward-looking tasks of deploying available re-

tual traditions of their own, piled on, charging traditional sources to achieve the mandated objectives as effi-

public administration with insufficient rigor and an af- ciently as possible. In accomplishing this goal, man-

finity for institutional description rather than analysis agers rely on their administrative expertise in

of choice and action (Lynn 1996)-failings, it must be wielding the instruments of internal managerial in-

fluence: organizational design, budgeting, human

noted, that these schools have since shown little incli-

resource development, and management control.

nation to remedy. The latter-day flogging of orthodoxy

(74)

by outsiders gathered momentum with two highly in-

fluential publications in 1992. From inside the profession, Robert B. Denhardt and Janet

To an academic audience, the Kennedy School's Michael Vinzant Denhardt (2000) similarly dismiss "old public

Barzelay described traditional public administration in administration" as neutral, hostile to discretion and to citi-

terms of a "bureaucratic paradigm." Its essence was "the zen involvement, uninvolved in policy, parochial, and nar-

prescribed separation between substance and institutionalrowly focused on efficiency.11

administration within the administration component of the That there was an old orthodoxy has thus become the

politics/administration dichotomy" (1992, 179, n. 18). new orthodoxy. The essence of traditional public adminis-

Barzelay summarized the bureaucratic paradigm first in a tration is repeatedly asserted to be the design and defense

series of normative principles and then in a series of asser- of a largely self-serving, Weberian bureaucracy that was

tions used to set off the postbureaucratic paradigm he fa-to be strictly insulated from politics and that justified its

vored. In Barzelay's view, a bureaucratic agency is focused actions based on a technocratic, one-best-way "science of

on its own needs and perspectives and on the roles and administration." Facts were to be separated from values,

responsibilities of the parts; defines itself both by the politics from administration, and policy from implemen-

146 Public Administration Review a March/April 2001, Vol. 61, No. 2

This content downloaded from

202.43.93.30 on Wed, 09 Aug 2023 08:25:32 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

tation. Traditional administration is held to be sluggish, the affairs of the city with integrity and efficiency and loy-

rigid, rule bound, centralized, insular, self-protective, and alty to the council, without participating in or allowing

profoundly antidemocratic. In Garvey's terms, the tradi- their work to be affected by contending programs or parti-

tional paradigm is thought to be preoccupied with capac- sans" (301).12

ity, to the almost total neglect of democratic control. Why haven't critics of orthodoxy simply taken these self-

characterizations as its authentic expression? Inadequate

Contemporaneous Views scholarship might be one reason. But such complex charac-

Interestingly, numerous paradigms or synopses of tra- terizations are obviously embedded in a wider intellectual

ditional premises and values are found in the traditional and historical context that makes ahistorical and out-of-con-

literature itself. text interpretations and "out-of-hand" pejorative dismissals

* Charles E. Merriam (1926) summarized the late Progres- plainly suspect. A caricature serves polemical ends better

sive view of the "outstanding features in the develop- than scrupulous historical scholarship. As we shall see, the

ment of institutions and the theory of the executive story that emerges from such scholarship is quite incongru-

branch of the government" as "(1) [t]he strengthening ous with the critics' caricatures.

of the prestige of the executive and the development of

the idea of executive leadership and initiative ... (2) [t]he

Traditional Thinking: A Reconsideration

development of a new tendency toward expertness and

efficiency in democratic administration ... and (3) [t]he Even if the roster of traditional authors is restricted to

tendency toward administrative consolidation and cen- those cited most often by critics, the case for a traditional

tralization" (126-7). paradigm is surprisingly shaky. Wilson's 1887 article

* In a monograph prepared for President Hoover's Re- wasn't widely read or cited until it was reprinted in 1941

search Committee on Social Trends, Leonard White (Fesler and Kettl 1991; Van Riper 1987); ' 3Weber's 1911-

(1933) summarized the "New Management" as "a con- 13 work on bureaucracy wasn't available in English trans-

temporary philosophy of administration" which had been lation or cited in the United States until after World War II.

concisely summarized in a series of principles by Gov- Weber, Taylor, and, arguably, even Wilson were not closely

ernor William T. Gardner of Maine on January 21, 1931: associated with the profession of public administration, and

consolidation and integration in departments of similar scholars have convincingly refuted interpretations of Wil-

functions; fixed and definite assignments of administra- son, Goodnow, and Gulick as advocating a politics-ad-

ministration dichotomy. Moreover, traditional authors

tive responsibility; proper coordination in the interests

whose habits of thought seem to be at issue if an entire

of harmony; executive responsibility centered in a single

individual rather than a board (144).

profession is to be denounced are simply ignored. To know

what traditional public administration really stood for re-

* Schuyler Wallace (1941) believed the thinking of the New

York Bureau of Municipal Research to be seminal, and quires a much more scrupulous look at its literature.

he identified seven essential elements: the centrality of

The Classical Period

the executive budget; an "integrated administrative sys-

tem, departmentalized and coordinated ... subject to leg- In its first century, the American state was

islative scrutiny" (15); personnel administration; a cen- prebureaucratic. Administrative officers-a great m

them elected-functioned independently of executive au-

tral purchasing system; systematic legislative review of

thority, with funds appropriated directly to their offices

the budget; a planning and advisory staff; and a scheme

of accounts and controls. (Merriam 1926).'4 According to Waldo, "The lack of a

* Both Sayre (1958) and Van Riper (1987) provided codi- strong tradition of administrative action ... contributed to

fied summaries of the traditional bureaucratic paradigm, ... public servants acting more or less in their private ca-

including some of the Weberian formulas derided by pacities" (1948, 11).15 A "spoils system" governed nine-

contemporary critics. teenth-century selection and control of administrators

Critics might also have quoted, albeit out of context, (Rosenbloom 1998; White 1954, 1965), 16 and haphazard

Frank Goodnow (1900)-"The necessity for this separa- oversight of administration was exercised by legislators,

tion of politics from administration is very marked in the political parties, and the courts (White 1933).7

case of municipal government" (84)-and White (1927), The gradual emergence of permanent government (be-

who said, "It ought to be possible in this country to sepa- ginning in the latter part of the nineteenth century) cre-

rate politics from administration. Sound administration can ated considerable confusion about the nature of adminis-

develop and continue only if this separation can be trative responsibility. As Frederick Mosher (1968) noted,

achieved. Over a century, they have been confused, with "The rise of representative democracy in the Western

evil results beyond measure.... [Tiheir job is to administer countries ... resulted in contests for political control of

The Myth of the Bureaucratic Paradigm 147

This content downloaded from

202.43.93.30 on Wed, 09 Aug 2023 08:25:32 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

administration ... and recognition of the need for a per- ity of political conditions makes it practically impossible

manent, protected and specialized civil service" (5). At for the same governmental organ to be intrusted in equal

the federal level, argued Stephen Skowronek (1982), "As degree with the discharge of both [politics and administra-

the American state was being fortified with an indepen- tion]" (10). According to Haddow, Goodnow's purpose was

dent arm of national administrative action, it was also "to show that the formal governmental system as set forth

becoming mired in operational confusion.... The national in the law is not always the same as the actual system, and

administrative apparatus was freed from the clutches of to suggest remedies to make the actual system conform to

party domination, direct court supervision, and localistic the political ideas upon which the formal system is based"

orientations only to be thrust into the center of an amor- (1939, 251).

phous new institutional politics" (286-7). Issues relating While Goodnow held that the executive function was

to control of the regulatory state divided president and subject to "the expression of the state will" (1900, 9ff, 79),

party and left administrative officials with no clear defi- he also noted that the "semi-scientific, quasi-judicial, and

nition of political responsibility (Skowronek 1982, 212).18 quasi-business or commercial" functions of administration

This practical and intellectual void encouraged scholars might be relieved from the control of political bodies (1900,

to pursue clarity. 85).22 In lieu of political control, officials charged with

executing the law concerning such functions were to be

Foundations subject to the control of judicial authorities upon the ap-

Reconciling the emerging tensions between creating plication of aggrieved parties.23 In advancing this complex

adequate administrative capacity and ensuring that it was scheme, Goodnow was prescient, perfectly expressing the

under firm democratic control became the intellectual dilemma of reconciling capacity with control:

project facing scholars concerned with defining and un-

[D]etailed legislation and judicial control over its

derstanding public administration. The most significant

execution are not sufficient to produce harmony be-

were Woodrow Wilson, Frank Goodnow, and Frederick

tween the governmental body which expresses the

Cleveland. They appeared to share the idea of assigning

will of the state, and the governmental authority

primary, but not exclusive, responsibility for establishing which executes that will.... The executive officers

collective purposes (politics) and for carrying out these may or may not enforce the law as it was intended

purposes (administration) to separate spheres: the legisla- by the legislature. Judicial officers, in exercising

ture and the administrative state, respectively. That this control over such executive officers, may or may

subtle idea would be reduced to the simplistic politics- not take the same view of the law as did the legisla-

administration dichotomy should not obscure its original ture. No provision is thus made in the governmental

intellectual subtlety and practical merit. organization for securing harmony between the ex-

Early readers of Wilson scarcely remarked upon his so- pression and the execution of the will of the state.

The people, the ultimate sovereign in a popular gov-

called dichotomy. Anna Haddow's (1939) pre-World War

ernment, must ... have a control over the officers

II assessment of "The Study of Administration" did not

who execute their will, as well as over those who

mention it; she noted instead that Wilson saw administra-

express it. (97-8)

tion as reform, a solution to the governmental problems of

the day. More recently, Walker (1990) argued that "Wil- V. 0. Key Jr. (1942) argued the notion that politics and

son never sought to erect a strong wall between politics administration are compartmentalized is "a perversion of

and administration. In his lectures and writings after 1887, Goodnow's doctrine" (146). "[Goodnow] saw that 'prac-

Wilson backtracked considerably from the strong tical political necessity makes impossible the consideration

dichotomistic expressions in the 1887 essay" (85). His pri- of the function of politics apart from that of administra-

mary influence as a scholar lay in his contributions to the tion"' (146). Goodnow expressed this view as follows:

political reform movement of his day and to the emergence "That administrative hierarchies have profound influence

of academic public administration (87).'9 on the course of legislative policy is elementary" (1900,

Frank Goodnow (1900) offered a more coherent per- 24). Merriam (1926) interpreted Goodnow this way: "[H]e

spective on the distinctive roles of politics and administra-drew a line between political officials who are properly

tion.20 Goodnow argued that politics and administration elective and the administrative officials, who are properly

constitute separate spheres of governance to preclude un- appointive. 'Politics' should supervise and control 'admin-

due political and judicial interference in the performance istration,' but should not extend this control farther than is

of administrative tasks.21 In explicating this distinction, necessary for the main purpose" (142). Merriam cites

Goodnow was careful to disavow the implication that each Goodnow and Wilson in urging us to think "less of separa-

sphere was the province of a separate branch of govern- tion of functions and more of the synthesis and action"

ment. His subtle argument was that "[t]he great complex- (142). Paul Appleby (1949) believed that "Goodnow's early

148 Public Administration Review a March/April 2001, Vol. 61, No. 2

This content downloaded from

202.43.93.30 on Wed, 09 Aug 2023 08:25:32 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

istration was given content by Frederick Taylor's (1911)

discussion drew a line less abrupt between policy and ad-

ministration than some who later quoted him" care to ac-ideas concerning scientific management, which divided

knowledge (16).24 formal responsibility for administration between a mana-

While Frederick A. Cleveland was a founder of the gerial group and a group that performed the work. This

New York Bureau of Municipal Research, he was also division of labor-that is, between those who are manag-

the author of The Growth of Democracy in the United ing ("figuring out what to do and how to do it") and those

States (1898). In that work, he advocated "studying po- who are working ("doing it")-became popular in both

litical life as a continuous process" (vi) and enumerated business and public administration practice. Organization

the problems that reformed government should address: and management came into the foreground.

"incompetency in office ... inequality in elections ... the In the profession's first textbook, published in 1926,

employment of the spoils system in appointments ... the Leonard White focused on the organization and manage-

corruption of our legislatures ... the subversion of mu- ment of the bureaucratic state. He took pains to rebuke the

nicipal government in the interest of organized spolia- public law tradition, arguing that "[t]he study of adminis-

tion" (387). To Cleveland, expansion of the civil service tration should start from the base of management rather

would lead to a government to which every citizen could, than the foundation of law, and is therefore more absorbed

in principle, aspire rather than constituting a class-based in the affairs of the American Management Association

fiefdom, as in Germany and Great Britain (see also W. than in the decisions of the courts" (White 1926, preface).25

W. Willoughby 1919). At the same time, he acknowledged the "traditional evils

Cleveland introduced his book Organized Democracy of bureaucracy," noting that "[t]he action of the adminis-

(1913) as follows: "The picture drawn [in this book] is tration has now become so important and touches such

one of the continuing evolution of the means devised by varied interests" that means must be found "to ensure that

organized citizenship for making its will effective; for the acts of administrative officers shall be consistent not

determining what the government shall be, and what theonly with the law but equally with the purposes and tem-

government shall do; for making the qualified voter an per of the mass of citizens" (1935, 420, 419). In other

efficient instrument through which the will of the people words, capacity and control go hand in hand.

may be expressed; for making officers both responsive In his 1927 textbook Principles of Public Administra-

and responsible ... government should exist for common tion, W.F. Willoughby saw the task of administrators as

welfare" (v). The contemporary problem, he argued, "is establishing an appropriate formal organization and ensur-

to provide the means whereby the acts of governmentaling adequate constraints on the administrator. Willoughby's

agents may be made known to the people-to supply thewas an "institutional" (or what we would today call a "struc-

link which is missing between the government and citi- tural") approach to administration in which "the emphasis

zenship" (454). is shifted from legal rules and cases to the formal frame-

Cleveland was undoubtedly a technocrat, but not work

the and procedures of the administrative machine"

kind derided by contemporary critics. "Technically," (Dimock

he 1936a, 7). His preface reveals his purpose: "[It

said, "the problem is to supply a procedure which will is now recognized that, if anything, a popularly controlled

enable the people to obtain information about what is government is one which is peculiarly prone to financial

being planned and how plans are being executed-infor- extravagances and administrative inefficiency" (1927, viii).

mation needed to make the sovereign will an enlightenedThus the separation of powers needed to be reconsidered,

expression on subjects of welfare" (454-5). To Cleve- administrative responsibility centralized and coordinated,

land, "a budget, a balance sheet, an operation account, a and the new, highly technical tasks of government held to

detail individual efficiency record and report, a system standards of efficiency and honesty no lower than those

operative in the business world. In other words, to

of cost accounts, and a means for obtaining a detail state-

ment of costs" were means by which government could Willoughby, efficient bureaucracy was a solution to the

be made transparent to citizens. His entire goal was "an manifold problems of democratic governance.

enlightened people" and "an informed public conscience" White and Willoughby can be understood, then, as at-

(465), as well as a government that provided service to tempting to advance the democratic project in America that

the people to counter "the threatened dominancy of a had been systematically assayed by Wilson, Goodnow, and

Cleveland. But, as Sayre (1958) noted, "In these pioneer

privileged class and of institutions inconsistent with the

spirit of democracy" (26). texts the responsibility of administrative agencies to popu-

lar control was a value taken-for-granted" (103), that is, it

Early Textbooks was paradigmatic. A new logic of democratic control that

Public administration, Wilson had argued, was a field challenged the premises of the spoils system had begun to

take form: Bureaucratic, technocratic government subject

of business. Businesslike professionalism in public admin-

The Mythl of the Bureaucratic Paradigm 149

This content downloaded from

202.43.93.30 on Wed, 09 Aug 2023 08:25:32 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

to judicial oversight was a way to ensure transparent gov- centrifugal forces of the spoils system still prevalent in

ernance that would be obedient and accountable to the con- local government.26 Owing to pressure from organizations

stitutionally expressed public will. such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, interests engaged

in foreign commerce, and the demands for administering

Consolidation relief, administrative power should be further consolidated.

From the appearance of the first textbooks until White

Sayre's noted the proliferation of [good government] orga-

"high noon of orthodoxy"-a conservative era during which pressing for efficient administration: the National

nizations

the public elected Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover to the Municipal League, the Governmental Research Associa-

presidency-Leonard White, John Dickinson, John Gaus,tion, the state Leagues of Municipalities, the American

Marshall Dimock, and Pendleton Herring, among others, Municipal Association, the National Legislators Associa-

probed issues of democratic governance more deeply. tion, and the Public Administration Clearing House (5).

Dickinson (1927) considered the proper role of the But, he warned, "We have not been deeply concerned on

courts, troublesome opponents of legislative delegation of the whole with more effective ways and means of citizen

power to administrators, in the emerging administrative participation in administration ... [or] with developing

state: "[W]ithin the field of matters which do not admit of machinery for employee participation ... [or] with the fun-

reduction to hard and fast rules, but must be trusted to the damental alteration of administrative relations between

discretion of the adjudicating body, can we say that there federal and state governments" (4-5).

is a regime of law?.... It would be unfortunate, if it were In 1936, Gaus, White, and Dimock produced a remark-

possible, for men to commit all their decisions to minds able little book that still repays careful reading, Frontiers

which run in legal grooves. The needs of the moment, the of Public Administration. In it, Dimock enunciated an ex-

circumstances of the particular case, all that we mean and pansive view of the public manager's role: "Those who

express by the word 'policy,' have an importance which view administrative action as simple commands ... fail to

professional lawyers do not always allow to them" (150- comprehend the extent to which administration is called

1). He drew a fundamental distinction between adminis- upon to help formulate policy and to fashion important

realms of discretion in our modern democracies" (1936c,

trative adjudication in regulation and in "matters as to which

the government is a direct party in interest, i.e., the distri-127). He held that "[t]he important problem is the manner

bution of pensions or public lands, collection of the rev- in which discretion is exercised and the safeguards against

enue, direct governmental performance of public services abuse of power which are provided" (1936b, 60).

and the like" (156). He asked: "If ... we ... imply that the Gaus (1936a) expatiated on his ideas concerning demo-

main purpose of the technical agency is to adjudicate ac- cratic participation: "Much of the effort of public admin-

cording to rules, will we not have abandoned the charac- istration today is rightly expended upon establishing pro-

teristic and special advantages of a system of administra- cedures and agencies whereby the general policy enacted

tive justice, which consists in a union of legislative, in the law is given precision and application with the ac-

executive, and judicial functions in the same body to se- tive collaboration of groups of citizens most affected....

cure promptness of action, and the freedom to arrive at [O]nly this process of conference, adjustment, statement

decisions based on policy?" (156). and restatement of facts and opinions will bring any wide-

John Gaus (1931) called attention to "the increasing spread conviction to a substantial group of citizens that

role of the public servant in the determination of policy,the resulting policy is their policy and that the administra-

through either the preparation of legislation or the mak-tors of it are their officials" (89). He noted "the fact of the

ing of rules under which general legislative policy is givencontemporary delegation of wide discretionary powers by

meaning and application" (123). He called for more ex- electorates, constitutions, and legislatures to the adminis-

tended inquiry into the "relationship between represen- trators. They must, of necessity, determine some part of

tatives of 'pressure groups' ... the political heads, legis- the purpose and a large part of the means whereby it will

lative committees, and permanent civil servants or be achieved in the modern state" (91). Thus, "[u]nless [the

semi-judicial administrative commissions" (124). He civil servant's] sense of responsibility is encouraged, the

noted the contributions to "the techniques of public man- responsibility of administration is incomplete, negative,

agement" (130) of extra-legal organizations, such as as- and external" (1936b, 43-4).

sociations of government professionals, functionally-ori- In Public Administration and the Public Interest, not-

ented study/advocacy organizations, and new institutions ing that "... the despised bureaus are in a sense the cre-

of governmental research. ations of their critics"(15), Herring (1936) explored the

In a monograph prepared for President Hoover's Re- tensions between administrative capacity and popular sov-

search Committee on Social Trends, White (1933) argued ereignty. "The bureaucrat ... does not suffer so much from

that strong central administration was an antidote to the an inability to execute the law unhampered as from an

150 Public Administration Review a March/April 2001, Vol. 61, No. 2

This content downloaded from

202.43.93.30 on Wed, 09 Aug 2023 08:25:32 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

uncertainty in direction. Where is the official to look for work by the over-all administrative staff and auxiliary agen-

guidance on the broad plain of public interest?"(22). On cies and by Congress. If there is the proper attention to

one hand, he argued, "the bureaucracy must be guarded these matters, the viewpoint of the civil service will differ

from domination by economic groups or social classes. from the surrogacy that one expects from the officials of a

On the other hand, it must be kept free of the abuses of pressure group" (283).

aloof, arbitrary, and irresponsible behavior to which pub- In his deeply analytical Federal Departmentalization

lic servants are so often prone.... In short, it must not de- (1941), Schuyler Wallace scorned the notions that orga-

velop a group interest within itself that will become its nization could be designed by rote application of abstract

raison d'etre" (384). To preclude such aloofness, "Consul- principles or that administration could be a true science.

tation with the persons and groups most directly concerned "That administrative hierarchies have profound influence

must ... become a regular feature of administration. This on the course of legislative policy," said V. 0. Key Jr. in

is the greatest safeguard against arbitrary or ill-considered a volume honoring Brownlow Committee member

action" (388).27 Charles Merriam, "is elementary" (1942, 146).28 In fact,

Thus, we find in the habits of thought characteristic of Key said, "The close communion of pressure group, con-

classical public administration a recognition of the policy- gressional bloc, and subordinate elements of the admin-

making role of civil servants, the inevitability of admin- istrative hierarchy obstructs central direction in the gen-

istrative discretion, the importance of persuading the eral interest" (152). The view that "administrative

courts to formally recognize the necessity for adminis- hierarchies" are "will-less instruments wielded by politi-

trative discretion, the concomitant requirement for respon- cians," said Key, is "not now widely held" (160). In the

sible conduct by managers and civil servants, and the same volume, White (1942) quoted Merriam and his col-

necessity for ensuring that citizens can somehow partici- leagues on the Brownlow Committee: "The safeguard-

pate actively in matters affecting their well-being based ing of the citizen from narrow-minded and dictatorial

on adequate information. bureaucratic interference and control is one of the pri-

mary obligations of democratic government" (212). Said

High Noon White, "A formal system of responsibility is ... essen-

It is against this background that we must assess Sayre's tial; it is unsafe to rely wholly on official codes and a

assertion that the 1937 publication of Gulick and Urwick's sense of inner responsibility; but, on the other hand, a

Papers and the Brownlow Report implied that "adminis- formal system in itself is inadequate" (215). Charles

tration was perceived as a self-contained world, with its Hyneman (1945) argued, "The essential feature of demo-

own separate values, rules, and methods" (1958, 102). As cratic government lies in the ability of the people to con-

trol the individuals who have political power" (310).

should be clear by now, it is difficult to find a justification

for this assertion in the literature. As these excerpts suggest, the literature of the "high noon"

Not long after these momentous 1937 publications, period was rife with insightful commentary about demo-

White, in the 1939 revision of his textbook, said that "[a] cratic governance. Where is Sayre's "self-contained world"?

responsible administration, cherished and strengthened by

those to whom it is responsible, is one of the principal foun-

dations of the modem democratic state" (578). Charles A.

Controversies

Beard cited as an axiom or aphorism of public administra- Skepticism that there was a close-knit "orthodoxy" in

tion that "[u]nless the members of an administrative sys- traditional thinking deepens when reviewing the period's

tem ... are subjected to internal and external criticism of a two great controversies concerning the administrative state:

constructive nature, then the public personnel will become the debate over the Walter-Logan Act and the Friedrich-

a bureaucracy dangerous to society and to popular gov- Finer debate over administrative responsibility.

ernment" (1940,234). Gaus and Wolcott (1940) asked: "At

what point in the evolution of policies in the life of the The Walter-Logan Act

community shall the process take place of transforming a The issue of executive control of administration from

specialist point of view and program, through compromise an administrative law perspective came into sharp focus

and adjustment, into a more balanced public program?" in the period surrounding the enactment and veto of the

Their answer was that "[m]uch of this process must takeWalter-Logan Bill (H.R. 6324, 76th Congress [1939]).

place in the administrative agencies through the selectionDean Roscoe Pound (1942) argued that administrative

agencies are under none of the safeguards that character-

of personnel, their continued in-service training, the con-

tent and discipline of their professions, researches, and ize judicial proceedings, especially when they are engaged

responsibilities, and attrition of inter-bureau and inter-de- in adjudication and thus acting as prosecutor and judge in

partment contact and association, and the scrutiny of their the same case. He advocated stringent procedural safe-

The Myth of the Bureaucratic Paradigm 151

This content downloaded from

202.43.93.30 on Wed, 09 Aug 2023 08:25:32 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

guards. In contrast, supporters of the New Deal urged that, Friedrich's (1940) argument had two parts. First, "Pub-

in the absence of relevant standards, narrow procedural lic policy, to put it flatly, is a continuous process, the for-

safeguards and private law values were an inadequate ba- mation of which is inseparable from its execution.... Poli-

sis for defining administrative jurisdiction and responsi- tics and administration play a continuous role in both

bility in the welfare state. formation and execution, though there is probably more

Inspired partly by anti-New Deal sentiment and partly politics in the formation of policy, more administration in

by a desire (supported by the American Bar Association) the execution of it" (6). Second, "[W]e have a right to call

to harness federal agencies and their haphazard approach ... a policy irresponsible if it can be shown that it was

to rule making, Congress enacted the Walter-Logan Bill.30 adopted without proper regard to the existing sum of hu-

According to Don K. Price (1959), the act established "a man knowledge concerning the technical issues involved"

single rigid method for the issuing of regulations" (484). or that "it was adopted without proper regard for existing

The act allowed anyone significantly affected by an ad- preferences in the community, and more particularly its

ministrative rule to challenge that rule in federal court, and prevailing majority.... Any policy which violates either

it required agencies to issue rules within a year of authori- standard, or which fails to crystallize in spite of their ur-

zation to do so. President Roosevelt vetoed it, calling it gent imperatives, renders the official responsible for it li-

the result of "repeated efforts by a combination of lawyers able to the charge of irresponsible conduct" (12).32 Spe-

who desire to have all the processes of government con- cialists with a passion for impartiality and objectivity, he

ducted through lawsuits and of interests which desire to argued, will know when to shrink from arbitrary and rash

escape regulation" (Breyer, Stewart, Sunstein, and Spitzer decisions and when to await the expression of the "will of

1998, 22). He acknowledged the legitimacy of the issue the people" (1946, 413).

by appointing the Attorney General's Committee on Ad- These controversies suggest that public administration

ministrative Procedure to study procedural reform of ad- was passionately engaged with the problems and dilem-

ministrative law. The governor of New York appointed mas of balancing capacity and control.

Robert Benjamin to do the same thing. The resulting re-

ports "agreed that the courts could not do the job the ad- Death in the Afternoon

ministrative agencies were doing, and that the administra- What happened in the immediate postwar world is surely

tive agencies themselves could not do it if anyone made the most puzzling development in the intellectual history

them imitate the court" (Price 1959, 485). The Adminis- of public administration, at least to an outsider. At a time

trative Procedure Act of 1946 was a compromise between of seemingly robust heterodoxy, when traditional thought

New Dealers, who had engineered the veto of the Walter- had identified but had hardly resolved fundamental issues

Logan Bill in 1940, and the Attorney General's commis- of democratic governance, Herbert Simon and Robert A.

sion, which had made its report in 1941.31 Dahl brought an influential profession to its knees by at-

tacking the seemingly innocuous tendency of Gulick and

Friedrich, Finer, and Administrative others to assert scientific principles of administration. Such

Responsibility principles are unscientific and inconsistent, they argued,

Within political science, Carl J. Friedrich and Herman and a public administration based on them scarcely de-

Finer were debating the nature of administrative respon- serves respect.

sibility. Finer (1940) doubted that a sense of duty, the Both Sayre and Waldo, who were thoroughly familiar

conscience of the official, "is sufficient to keep a civil with the pre-war literature, urged the intellectual redirec-

service wholesome and zealous" Thus political responsi- tion of the field, celebrating not so much the

bility must be introduced as the adamant monitor of the behavioralism of Simon as what they saw as an emergent

public service. "[T]he first commandment," he argued, heterodoxy of public administration literature following

"is Subservience" (335). Finer cited Rousseau: The people World War II. Said Sayre, "Our values ... have moved

can be unwise, but they cannot be wrong. He acknowl- from a stress upon the managerial techniques of organi-

edged the many drawbacksl] of political control" but zation and management to an emphasis upon the broad

said they could be remedied, and their consequences were sweep of public policy-its formulation, its evolution,

less ominous than those of granting administrators addi- its execution, all either within or intimately related to the

tional discretion. "[T]he result to be feared is the enhance-

frame of administration" (1958, 4).

ment of official conceit" (340). He goes on: "Moral re- Thus tradition was dead, stuffed, and mounted on the

sponsibility is likely to operate in direct proportion to the wall. Or was it? Did the contributions of the postwar lit-

strictness and efficiency of political responsibility, and erature constitute a sharp departure from traditional think-

to fall away into all sorts of perversions when the latter is ing, as Sayre and Waldo claimed?

weakly enforced" (350).

152 Public Administration Review a March/April 2001, Vol. 61, No. 2

This content downloaded from

202.43.93.30 on Wed, 09 Aug 2023 08:25:32 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Voices from the Grave of subordinate echelon of government subject in our

scheme of things to the supervision of legislature,

Surely an era of heterodoxy had ensued, although it is

chief executive, and judiciary.... The administrator

beyond the scope of this article to assay it. But the voice of

in the public service is concerned with all three, and

traditional public administration continued to be heard.33

ignores any one branch only at his peril. So it seems

Paul Appleby, Charles Hyneman, John Gaus, John Millett, to me that the politics of public administration is

Arthur Macmahon, Herbert Kaufman, Fritz Morstein Marx, concerned with how administrative agencies in our

Frederick Mosher, and Emmette Redford, among others, government are kept subject to popular direction and

continued to influence the profession's agenda in ways that restraint in the interests of a free society, through

were entirely consonant with the traditional theme of demo- the operation of three coordinate branches. (vii-viii)

cratically responsible public management, though with

In a discussion of public management that rebuked con-

perhaps less emphasis on administrative capacity.

temporary critics, Millett said that "[t]he challenge to any

Lauded by Sayre as a postorthodox thinker, Paul

administrator is to overcome obstacles, to understand and

Appleby (1949) argued the pre-war theme that "adequate

master problems, to use imagination and insight in devis-

centralization of responsibility for performance of the func-

ing new goals of public service. No able administrator can

tion agreed upon at the level agreed upon is essential to

be content to be simply a good caretaker. He seeks rather

popular control" (162). Why? "Public administration is

to review the ends of organized effort and to advance the

policy-making. But it is not autonomous, exclusive or iso-

goals of administrative endeavor toward better public ser-

lated policy-making. It is policy-making on a field where

vice" (401). But, Millett went on, "[I]n a democratic soci-

mighty forces contend, forces engendered in and by the

ety this questing is not guided solely by the administrator's

society. It is policy-making subject to still other and vari-

own personal sense of desirable social ends.... Manage-

ous policy-makers. Public administration is one of a num-

ment guided by [the value of responsible performance]

ber of basic political processes by which this people

abhors the idea of arbitrary authority present in its own

achieves and controls governance" (170).

wisdom and recognizes the reality of external direction and

In an incisively argued book, Charles Hyneman, con-

constraint" (401, 403).

cerned that bureaucracy might otherwise act in a manner

In Arthur Macmahon's view, "Our main problem lies

inimical to the public interest, argued that elected officials

where the law imposes a special purpose while it leaves

must be our primary reliance for direction and control

some leeway for judgment. What is the bearing of the

(1950, 6). There must, he said, be "a structure of govern-

public interest in such a situation?" (1955, 38). His an-

ment which enables the elected officials really to run the

swer was that "[t]he essence of rational structure for any

government" (15).34 Conceding "that the administrative

purpose frequently lies in recognizing how far adminis-

official cannot obtain from the political branches of the

tration is an argumentative as well as a deliberative pro-

government all of the guidance he needs" (52), Hyneman

cess that goes on within the frame of legislation" (40).

nonetheless argued that other methods for obtaining guid-

The safeguards against misuse of discretion or poor judg-

ance must supplement, not replace or supplant, political

ment concerning legislative intent "lie in attitudes that

direction. "The American people have authorized nobody

should be diffused throughout administration" or a "per-

except their elected officials to speak for them" (52).

spective of public interest" (50).

According to Gaus (1950), "The fact is that administra-

In reviewing the values governing administration and

tion is an aspect, a process, of every phase of government,

their interrelationships, Kaufman (1956) noted that "the

from the first diagnosis of an emerging problem by a chem-

quest for neutral competence has normally been made not

ist in a health department to the final enforcement in detail

as an alternative to representativeness, but as a fulfillment

of a resulting statute and regulation" (165). Thus, we must

of it" (1060), valued at least as much by the public as by

"steer between the extremes of a vague, general, ambigu-

civil servants themselves. But representativeness and neu-

ous comprehensiveness without savor or focus, and a re-

tral competence tended to produce fragmentation. The an-

finement and specialization that detaches us from the tang

swer was to build up the power of the chief executive to

and urgency of human action" (166). He famously con-

ensure executive leadership as the counterforce. Kaufman

cluded: "A theory of public administration means in our

stressed, however, that neutral competence and its succes-

time a theory of politics also" (168).

sor, executive leadership, nonetheless acknowledged rep-

Like Gaus, John Millett (1954) had much to say about resentativeness as their governing value.

politics and administration: In his book on the administrative state, Morstein Marx

Are administrative agencies ... to be regarded as a (1957) listed four essentials of administration: "(1) the es-

'fourth branch' of government? I believe that they sential of rationality, (2) the essential of responsibility, (3)

have no such exalted status. Rather, they are a kind the essential of competence, and (4) the essential of conti-

The Myth of the Bureaucratic Paradigm 153

This content downloaded from

202.43.93.30 on Wed, 09 Aug 2023 08:25:32 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

nuity" (34). Rationality had numerous aspects or mean- budgeting, and planning, was purely instrumental to a more

ings: the pursuit of purpose (administration as a means to humane and just society" (1992, 200-1). In a similar vein,

an end); a source of cohesion (as opposed to "countless Gary Wamsley and James Wolf (1996) argue that tradi-

clusters of personal influence" [36]); application of knowl- tional public administration incorporated such ideas as

edge; application of reason; a gatherer of intelligence. collaboration, a moral perspective on the public interest, a

Concerning responsibility, he argued that "[i]n structures concern for democratic administration, and pragmatism.35

as elaborate and hence as rich in opportunities for obstruc- My own reading of traditional literature has led me to dis-

tion as is large scale organization, control could not ac- cern, beginning with Wilson, a professional reasoning pro-

complish coordination in the interplay of human wills. cess that took for granted (and thus did not always expli-

Control requires as well "well-formed habits of deference cate) the interrelationships among the values of democracy,

sustained by reason" (43). the dangers of an uncontrolled, politically corrupted, or

The logic of administrative responsibility was summa- irresponsible bureaucracy, the instruments of popular con-

rized by Emmette Redford in his 1958 book, Ideal and trol of administration, and judicial and executive institu-

Practice in Public Administration. He argued that thoughuh

tions that can balance capacity with control in a constitu-

administration is permeated and circumscribed by law, dis-

tionally appropriate manner.

cretion is vital to its performance.... Discretion is neces- As paradigmatic thinking should, traditional perspec-

sary in administration [because] law is rigid, and policy tives raise fundamental questions: To what extent should

must be made pragmatically" (43). Integrated and hierar- powers be separated? In the exercise of administrative dis-

chical structures, he argued, are essential to ensuring that cretion, what values should guide administrative behav-

bureaucracy is subject to control from outside. In other ior? How might the public interest be identified? What are

words, exercising authority over subordinates is not anti- the sources of legitimacy for administrative action? As we

democratic, but the opposite; capacity and control are two have seen, there was hardly unanimity on the answers:

sides of the same coin. Electorally supervised hierarchy, or expertise and an "in-

"Responsibility," Mosher argued, "may well be the most ner check" on the discretionary behavior of officials? Stat-

important word in all the vocabulary of administration, utes and judicial rulings, or public opinion and group pres-

public and private" (1968, 7). The threats to objective re- sures as the expression of the public will? Technical

sponsibility are not, he said, in politics but, echoing Her- solutions or human judgment as a basis for operational

ring, in "both professionalization and unionization with decisions? Management or organization as the source of

their narrower objectives and their foci upon the welfare "good government"? "Public will" or "public interest" as

and advancement of their members" (209). As for repre- the basis of legitimacy?

sentativeness, "who represents that majority of citizens who If there are assumptions that are taken for granted, or a

are not in any [represented group or interest]?" (209). In paradigm, in traditional thought, it is that the structures

general, "The harder and infinitely more important issue and processes of the administrative state constitute an ap-

of administrative morality today attends the reaching of propriate framework for achieving balance between ad-

decisions on questions of public policy which involve com- ministrative capacity and popular control on behalf of pub-

petitions in loyalty and perspective between broad goals lic purposes defined by electoral and judicial institutions,

of the polity ... and the narrower goals of a group, bureau, which are constitutionally authorized means for the ex-

clientele, or union" (210). pression of the public will. In other words, preserving bal-