Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Altitudinal Distribution Habitat Use and Abundance of Grallaria Antpittas in The Central Andes of Colombia

Altitudinal Distribution Habitat Use and Abundance of Grallaria Antpittas in The Central Andes of Colombia

Uploaded by

Vinicio7 EscuderoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Altitudinal Distribution Habitat Use and Abundance of Grallaria Antpittas in The Central Andes of Colombia

Altitudinal Distribution Habitat Use and Abundance of Grallaria Antpittas in The Central Andes of Colombia

Uploaded by

Vinicio7 EscuderoCopyright:

Available Formats

Bird Conservation International (1999) 9:271-281.

© BirdLife International 1999

Altitudinal distribution, habitat use, and

abundance of Grallaria antpittas in the

Central Andes of Colombia

GUSTAVO H. KATTAN andj. WILLIAM BELTRAN

Summary

Grallaria antpittas are a group of little known birds from the understorey of humid forests

of the tropical Andes, with several species having very narrow distributions. At Ucumari

Regional Park, which protects the Otun River watershed in the Central Andes of

Colombia, five species occur sympatrically at 2,400 m, including the recently rediscovered

G. milleri, of which this is the only known population. We studied the patterns of

altitudinal distribution, habitat use and abundance of the five species in the park. We

found altitudinal segregation at a local scale, with two species, G. ruficapilla and G.

squamigera, found at lower elevations (1,800-2,500 m) and two other species, G. nuchalis

and G. rufocinerea, at higher elevations (2,400-3,000); G. milleri was recorded only in the

2,400-2,600 m range. The five species overlap in the range 2,400-2,600 m, where they occur

in three habitats: early regeneration, overgrown alder plantations and 30-year-old forest.

There were no differences in density among habitats for any species; the five species used

the three habitats in proportion to their occurrence in the landscape. Grallaria milleri had

the highest overall density (1.3 ind/ha) while G. squamigera had the lowest density

(0.2 ind/ha), and the other three species were intermediate. We estimated 106 individuals

of G. milleri in an area of 63 ha, and only seven individuals of G. squamigera. The Otun

River watershed concentrates an unusual number of Grallaria antpittas, including three

endemic species, and the information presented here is fundamental to any future habitat

management plans to ensure the persistence of these populations.

El genero Grallaria esta compuesto por aves muy poco conocidas del suelo de los

bosques humedos de los Andes tropicales, varias de las cuales tienen distribuciones

geograficas muy estrechas. En el Parque Regional Ucumari, el cual protege la cuenca del

rio Otun en la Cordillera Central de Colombia, existen cinco especies en simpatria a una

elevacion de 2,400 m; una de ellas es G. milleri, especie recientemente redescubierta, siendo

esta hasta ahora la unica poblacion conocida. Realizamos un estudio de los patrones de

distribution altitudinal, uso de habitat y abundancia de las cinco especies en el parque.

Encontramos segregation altitudinal a escala local, con dos especies, G. ruficapilla y G.

squamigera, distribuidas en la parte baja del parque (1,800-2,500 m) y otras dos especies,

G. rufocinerea y G. nuchalis, en la parte alta (2,400-3,000 m); G. milleri hie registrada solo

en el rango de 2,400-2,600 m. Las distribuciones de las cinco especies se superponen en el

rango de 2,400-2,600 m, en donde estan en tres tipos de habitat: rastrojos de regeneration

temprana, bosques sembrados de aliso (Alnus acuminata) y bosques secundarios de 30

afios. No encontramos diferencias en densidad entre habitats para ninguna de las especies;

las cinco especies usan los tres habitats en proportion a su cobertura en el paisaje. Grallaria

milleri tiene la densidad mas alta (1.3 ind./ha), mientras que G. squamigera tiene la mas

baja (0.2 ind./ha) y las otras tres son intermedias. Estimamos 106 individuos de G. milleri

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270900003452 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Gustavo H. Kattan and J. William Beltran 272

y solo 7 de G. squamigera en un area de 63 ha. La cuenca del rfo Otun concentra un

alto numero de especies de Grallaria, incluyendo tres especies endemicas, por lo que la

information obtenida en este estudio es fundamental para futuros planes de manejo de

habitat que aseguren la persistencia de estas poblaciones.

Introduction

The ground antbirds, family Formicariidae, are a group of little-known birds

from the understorey of humid Neotropical forests. The group reaches its max-

imum diversity in the tropical Andes, where it is represented mainly by the

genus Grallaria. Of the 30 species of Grallaria known from South America, 26 are

Andean, with altitudinal ranges that start above 800 m (Ridgely and Tudor 1994).

Grallaria antpittas are noteworthy for exhibiting high levels of endemism. Four-

teen Andean species have very restricted geographic distributions, being known

from only one or a few localities (Ridgely and Tudor 1994). This may simply

reflect poor knowledge, as antpittas are very secretive and inhabit dense under-

growth, which makes them very difficult to record. Although field work in previ-

ously unexplored regions is filling gaps in the geographical distribution of some

species (e.g. Stiles and Alvarez-Lopez 1995), antpittas remain one of the most

elusive and least-known groups of Neotropical birds. This is reflected in the fact

that several new species have been discovered in the past 30 years (e.g. Graves

1987, Schulenberg and Williams 1982), and in one case not far from a large urban

centre (Stiles 1992).

At Ucumari Regional Park, which protects the Otun River watershed in the

Central Andes of Colombia, five species of antpitta occur sympatrically at an

elevation of 2,400 m, including the recently rediscovered Brown-banded Antpitta

G. milleri (Kattan and Beltran 1997). Because this is so far the only known popula-

tion of Brown-banded Antpitta, this species is highly vulnerable. Another species

occurring at Ucumari, the Bicolored Antpitta G. rufocinerea, is also endemic to

the Central Andes and, although its status is indeterminate, it is considered in

need of attention (Collar et al. 1992). The other three species, Undulated G. squa-

migera, Chestnut-crowned G. ruficapilla, and Chestnut-naped Antpitta G. nuchalis,

are more widely distributed in the Andes from Colombia and Venezuela, south

to Peru and Bolivia. Ucumari, therefore, provides a valuable opportunity for a

comparative study of antpitta ecology.

Here we present results of a study that had the objectives of (1) determining

the altitudinal ranges of the five species in the Otun River watershed, (2) deter-

mining whether the species differed in their patterns of habitat use in the area

of overlap, and (3) comparing the local abundances of the five species. Because

the syntopy of congeners raises the possibility of competition, we examined the

degree of morphological similarity in traits that may be related to resource use.

Study area and methods

Ucumari Regional Park (4°44'N 75°36'W) is a 4,240-ha watershed protection area,

located east of the city of Pereira, on the western slope of the Central Andes of

Colombia. The park protects the slopes of the Otun River between elevations of

1,800 and 2,600 m. At this elevation the river runs through a narrow glacier valley

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270900003452 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Habitat use and abundance of antpittas 273

with very steep slopes and numerous streams. At its upper limit, Ucumari abuts

the 38,000-ha Los Nevados National Park, which protects higher elevations. Ucu-

mari is the only watershed in the Los Nevados area that provides almost continu-

ous forest cover down to 1,800 m. Below the lower limit of the park, forests are

highly fragmented.

Before the initiation of protection programmes in the 1960s, the Ucumari area

was deforested and dedicated to extensive cattle ranching (Londono 1994). For-

ests remained only on the steepest slopes and in some subsidiary canyons. Three

decades ago, regional government organizations began purchasing private lands

and initiated revegetation programmes. Some areas were planted with monos-

pecific stands of native alder Alnus acuminata at the upper elevations (2,200-

2,600 m) and exotic ash Fraxinus chinensis at lower elevations (1,800-2,000 m) but

most pasture areas were allowed to regenerate naturally. Tree plantations were

not managed and are presently overgrown with native vegetation, in particular

alder stands (Murcia 1997). Ucumari is a multiple-use management area, with

some small private holdings still included in the park. Therefore, at present,

Ucumari has a very heterogeneous landscape formed by a patchwork of small

pastures, overgrown tree plantations and different-aged forest stands (Londono

1994)-

The study was conducted between May 1996 and April 1997. To determine

altitudinal ranges of antpittas, we conducted monthly surveys along the 10-km

main park trail between 2,000 and 3,000 m elevation. This trail runs parallel to

the river and cuts across a wide variety of habitats. In these surveys we counted

singing birds and recorded the elevation, to determine the highest and lowest

elevation for each species. To obtain data on habitat use and local abundance,

we conducted detailed censuses at the site known as La Pastora, between eleva-

tions of 2,400 and 2,600 m, where the five species of antpitta co-occur. At this site

we selected three censusing routes totalling 6.3 km, that criss-crossed the study

area. These routes were censused once a month and the positions of singing birds

were located on a map. The three routes covered three major habitat types:

(1) Early regeneration: early second growth vegetation, 15 years old or less, with

a dense undergrowth of herbs, and a canopy of shrubs 2-5 m tall.

(2) Second growth forest: 30-year-old regeneration forest, with a canopy 15-20 m

tall, irregular layers of foliage stratification, and abundance of epiphytes

(Rangel and Garzon 1994, Murcia 1997).

(3) Alder stands: patches of 30-year-old alder plantations, with a rather homo-

geneous canopy 15-20 m tall, and with understorey growth typical of early

to mid-regeneration stages (Murcia 1997).

It was not possible to establish transects along a single habitat type, as these

habitats do not occur as discrete patches of appreciable size; instead, the three

habitats are interspersed in a complex mosaic. We drew maps of the censusing

routes and divided them into 10 500-m transects, separated by intervals of 50 m.

For each transect, we estimated the amount of cover of each habitat type, based

on a 100-m-wide strip. We took each transect as an independent and representat-

ive sample of the landscape in our study area.

Censuses were conducted mainly by listening for antpitta songs given spon-

taneously, or in response to tape recordings of the species' songs. We recorded

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270900003452 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Gustavo H. Kattnn and ]. Williajn Beltran 274

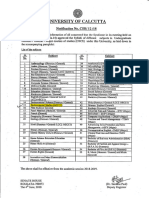

Table 1. Altitudinal ranges (in metres) of antpittas in the 2,000-3,000 m transect at Ucumari, and in

the Andes of Colombia

Species This study Hilty and Brown (1986)

G. ruficapilla 2,000-2,550 1,700-2,800

G. rufocinerea 2,400-3,000 2,100-3,100

G. nuchalis 2,350-3,000 2,200-3,000

G. milleri 2,400-2,600 2,700-3,100

G. squamigera 2,000-2,550 2,300-3,800

antpitta vocalizations with a Sony TCM-5000EV recorder, equipped with a

Sennheiser ME66 cardioid microphone. Playbacks were made at least at 100-m

intervals, to avoid drawing birds from neighbouring territories to the recording.

The position of each singing bird was marked at a point we estimated was per-

pendicular to the transect, and plotted on a map.

To complement visual and auditory records, and to obtain morphometric data,

we captured birds with mist-nets. We operated 12 to 18 nets from dawn to dusk,

in places where we had previously located singing birds. We placed nets in con-

tact with the ground and well hidden in dense vegetation, and played back

recordings to attract the birds. All captured birds were weighed, measured,

colour-banded, and released.

To analyse patterns of habitat use, we determined the habitat in which each

bird was located, and the number of individuals of each species per habitat type

per transect. Because each habitat was represented in different proportions in

each of the 10 transects, we standardized by calculating the number of indi-

viduals per 500 m for each habitat, and then averaged the 10 transects. Differ-

ences in density (number of individuals per 500 m) among habitats were ana-

lysed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for each species. We also

analysed whether the proportion of individuals of each species in each habitat

was different from the expected, based on the proportion of occurrence of each

habitat, with a chi-square test.

To obtain an estimate of population density, we used the fixed-width transect

method (Franzreb 1981). We estimated the maximum distance that we consid-

ered allowed us to locate a singing bird with reasonable precision. Area sampled

by the transects was calculated as the length of the transect multiplied by double

the detection distance. Because of differences in song intensity, we estimated a

maximum detection distance of 30 m for G. rufocinerea and G. squamigera, and

50 m for G. milleri, G. ruficapilla, and G. nuchalis. Densities are presented as the

mean for the three transects. Total densities for the three habitats combined were

compared among species with one-way ANOVA.

Results

The five antpitta species differed in their altitudinal ranges, with a replacement

of species in the 2,300-2,50011:1 range (Table 1). Grallaria ruficapilla was recorded

only in the lower half of the transect, whereas G. rufocinerea and G. nuchalis were

found in the upper half. Grallaria squamigera was recorded only during detailed

censuses at La Pastora, but it is known to occur at elevations of 1,800-2,000 m in

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270900003452 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Habitat use and abundance of antpittas

12-i

milleri rufocinerea ruficapilla nuchalis

Figure 1. Density, in number of birds per 500-m transect (n = 10 transects), of four Gralla-

ria species in three habitats in the range 2,400-2,600 m. Bars represent one standard error.

the same valley (Naranjo 1994), and we assumed that it is present along the

lower half of the transect. These four species partially overlapped in the range

2,300-2,600 m, where they completely overlapped with G. milleri, which has been

recorded only in the range 2,400-2,600 m (Table 1).

In the area of sympatry, all species used the three habitats sampled. Three lines

of evidence indicated that antpittas are territorial: (1) birds usually responded

promptly to playbacks, (2) singing birds were present at particular sites through-

out the year, and (3) some banded birds were recaptured at the same sites at

time intervals of 2 to 12 months. Therefore, we assumed that the mapping of

birds along the 10 transects represented a census of the territorial bird population

during the year of study. Densities of species (in number of birds per 500 m)

were not significantly different among the three habitats {milleri: F229 = 0.3,

P = 0.7; nuchalis: F229 - 0.5, P = 0.6; G. ruficapilla: F229 = 0.7, P = 0.5), except for

rufocinerea, which showed a tendency to be more abundant in alder and second-

growth forest than in early regeneration {F229 = 2.7, P = 0.08; Figure 1). Antpittas

used the three habitats in proportion to their occurrence in the landscape (Table

2). Grallaria sauamigera was excluded from this analysis because it was found in

Table 2. Numbers of territorial antpittas recorded in three habitats at La Pastora, Ucumari Regional

Park, 2,400-2,600 m, during May 1996-April 1997

Species Early regeneration Alder Second-growth P-value*

forest

G. milleri 33 32 >O.l

G. rufocinerea 8 11 13 >o.8

G. nificapilk 6 9 15 >0. 7

G. nuchalis 4 15 15 >o.o8

G. squnmigera 2 3 -

* Chi-square test.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270900003452 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Gustavo H. Kaftan and j . William Beltran 276

La Pastora

120 n (2,400-2,600 m)

recorded

banded

milleri nuchalis ruficap. rufocin. squam.

Total Transect (2,000-3,000 m)

120n

« 100-

:

1

I 80-

~ 60H

o

55

20:

milleri nuchalis ruficap. rufocin. squam.

Figure 2. Total number of individuals of five Grallaria species recorded in transects at

2,400-2,600 m (6.3 km) and in the whole altitudinal transect between 2,000 and 3,000 m

(10 km).

low numbers; only eight individuals were located during the year of study

(although this scarcity may be a sampling artefact, as this species is the most

difficult to detect, because it rarely sings and does not readily respond to

playbacks). There were significant differences in density among the five species

for the three habitats combined (F4,49 = 9.0 , P < 0.001, n = 3 transects). Grallaria

milleri had the highest density (1.3 ± S.E. of 0.2 individuals per hectare), while G.

squamigera had the lowest density (0.2 ±0.1 inds./ha). Densities of G. rufocinerea

(0.8 + 0.2), G. ruficapilla (0.4 ± 0.1), and G. nuchalis (0.5 ± 0.2) were not significantly

different (Fisher multiple comparison test).

To estimate local abundances, we looked separately at counts of individuals

recorded in maps at La Pastora, and along the total altitudinal transect. At La

Pastora (2,400-2,600 m), G. milleri was the most abundant species, with 106 indi-

viduals recorded along 6.3 km of trails (Figure 2). G. squamigera was the least

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270900003452 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Habitat use and abundance of antpittas 277

Table 3. Measurements of five species of Grallaria of Ucumari Regional Park (mass in grams, all other

measurements in millimetres). Numbers in the table indicate mean ± S.D. Superscripts with the same

letter indicate no significant difference

Species n Mass Tarsus Culmen Gape Wing chord

G. rufocincrca 8 44-8 + 4-7 46.2 ± 2.4s 17.1 + 1.5" 12.8 ±1.0 86.7 ±3.1'

G. milleri 18 52.5 + 3.2 46.6 ± 1.9'' 19.3 + 1.4' 14.0 ± 1.4 89.6 ±3.5'

G. ruficapilla 8 82.7 ± 3 . 6 54.2 ±2.4 2 3 .8 + l. 4 d 17.1 ± i.i c 101.6 ± 1.3

G. nuchalis 4 101.2 + 4.3 60.5 ± 2.311 23.3 + 3.1" I7.I ±2.1° 117.5 ±3.3

G. squamigcra 4 131.6 ±3.1 60.7 ± o.8b 30.0 + 2.0 17.6 ± 1.9° 143.7 ±3.1

abundant, with only eight individuals recorded in the same transects. The other

three species had intermediate abundances. Density of G. nuchalis was higher in

the upper part of its range (16.7 individuals per km of transect between 2,600

and 3,000 m) than in La Pastora (6.5 ind/km). In contrast, G. rufocinerea had a

higher density at La Pastora (5.7 ind/km) than in the 2,600-3,000 m range

(3.7 ind/km). Density of G. ruficapilla was the same at La Pastora than in the

lower part of the transect (2,000-2,400 m, 6.0 ind/km). Therefore, when con-

sidering the whole altitudinal transect (2,000-3,000 m), G. nuchalis was as abund-

ant as G. milleri (Figure 2), while abundance of G. ruficapilla doubled, and that of

G. rufocinerea increased by 50% with respect to the 2,400-2,600 m range.

Body masses of the five Grallaria spp. differed by a factor of three, and all were

significantly different (one-way ANOVA, F4 37 = 564.0, P< 0.001). Differences in

body measurements, however, were much smaller (Table 3). Tarsus length,

culmen, and wing chord did not increase proportionally to body mass. The two

smaller species, G. rufocinerea and G. milleri, did not differ significantly in any of

the three measurements, while G. nuchalis had the same tarsus length as G. squa-

migera, but the same bill length as G. ruficapilla (Table 3).

Discussion

Four or more species of Grallaria antpittas may occur along elevational gradients

in the humid Andes from Venezuela south to northern Bolivia, and the morpho-

logical distinction between sympatric species is usually clear-cut (Graves 1987).

In the case of G. rufula and G. blakei in the Peruvian Andes, in which the two

species are morphologically similar, they segregate altitudinally (Graves 1987).

At Ucumari Regional Park five species of Grallaria partially coincide in the 2,000-

3,000 m range. Two of the species, G. ruficapilla and G. squamigera, are sympatric

between 2,000 and 2,500 m (ranges of both species extend down to 1,800 m; Nar-

anjo 1994). They are replaced by another pair, G. rufocinerea and G. nuchalis, in

the upper part of the transect, between 2,400 and 3,000 m. In both pairs, species

are different in body size. However, these four species and G. milleri overlap in

the 2,400-2,600 m range, where all occur in the same habitats.

We found no statistical differences in patterns of habitat use among the five

species in the area of overlap. All species used the three habitat types, young

second-growth, 30-year-old mixed forest, and 30-year-old alder forest, in propor-

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270900003452 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Gustavo H. Kattan and j . William Beltran 278

tion to their occurrence in the landscape. Therefore, they are not only sympatric

but syntopic. It is possible that the observed patterns of habitat use are peculiar

to Ucumari, and not typical of the species along their geographical ranges. The

three habitats sampled at La Pastora are the result of relatively recent regenera-

tion, and occur in a complex mosaic of completely interspersed, small patches.

The five species of antpitta were widely distributed in this landscape, and over-

lap of species was almost total. Up to four species were frequently recorded in

the same patches, and individuals of two or three species were captured in the

same mist-nets several times.

There were, however, some subtle differences that may be biologically signi-

ficant. Grallaria ntfocinerea tended to be more abundant in closed-canopied hab-

itats with an open understorey, than in dense second growth. In contrast, G.

ruficapilla tended to be near the edges of forest and alder stands, where the under-

storey is denser, whereas nuchalis was most frequently found in patches of forest

with an open understory. Renjifo and Andrade (1987) report G. nuchalis as

"common" (recorded in more than 50% of observation clays) in primary forest

and "fairly common" (recorded on 10-50% of observation days) in secondary

growth at 2,800 m in a neighbouring watershed. We are currently (December

1998) radio-tracking birds to assess home ranges and more finely dissect the

patterns of habitat use of individuals, and degree of spatial overlap of the five

species.

The spatial overlap of the five species of antpitta raises the possibility of com-

petition for resources, such as nesting sites or food. When similar-sized con-

geners of some Andean birds occur at the same localities, they tend to segregate

altitudinally (Graves 1987, Remsen and Graves 1995a, b). Although antpittas

differ widely in body mass, there is overlap in some measures of body size in

some of the species. Grallaria milleri is about 20% heavier than G. ntfocinerea but

the two species do not differ in tarsus length, bill length, or wing chord (Table

3). Likewise, G. nuchalis has longer tarsi than G. ruficapilla but both have the same

bill length. Therefore, these pairs of species may be competing for the same food

items. It is not even clear that a difference in body size will translate into differ-

ences in prey type and the five species might be in direct competition. However,

the existence of competition depends on there being food limitation, or on one

species depressing resource availability for others (Martin 1986), factors that we

have not yet determined.

If the five species are competing for resources, this has important implications

for habitat use. Presumably, species would first select the habitat where their

fitness is maximal, and then settle on suboptimal habitats. If the five species are

selecting their habitats independently, the ideal free distribution model (Fretwell

and Lucas 1970) predicts that density in the "preferred" habitat will be highest,

and will decrease as habitat suitability decreases (Block and Brennan 1993, Wiens

1989). Thus the absence of differences in habitat use would suggest that antpittas

do not exhibit a preference for any of the three habitats. If the five species are

competing, however, intra- and inter-specific interactions may cause densities in

lower-quality habitats to increase to levels equal or higher than those in the

preferred habitat (Wiens 1989).

Another factor that may affect densities and patterns of habitat use is the altitu-

dinal distribution. At our study site (La Pastora), at least three of the species are

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270900003452 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Habitat use and abundance of antpittas 279

at their altitudinal limits and densities of two change with elevation. Numbers

of G. nuchalis were higher at higher elevations than at La Pastora, which is at its

lower elevational limit. Likewise, patterns of habitat selection of the species may

differ towards the centre of their altitudinal distribution. Therefore, patterns of

population density and habitat selection of antpittas need to be evaluated at

different locations to draw any conclusions about habitat preference.

Our population estimates indicate that in its narrow altitudinal range, G. milleri

is the most abundant species. Determining total population size and amount of

habitat available in the case of globally threatened species, such as G. milleri, is

important for predicting probability of persistence of the population. Original

records of G. milleri in its type locality, in the Quindio River watershed just south

of Ucumari, are from 2,745 to 3,140 m elevation (Collar et al. 1992). However, we

did not detect the species above 2,600 m in our surveys. The total area of habitat

available for G. milleri at Ucumari is undoubtedly larger than the small area we

sampled, but we do not know how large. We do not know how plastic the species

is in its habitat requirements either, although our data suggest the species does

well in a variety of second-growth habitats. Original reports of the habitat where

G. milleri was collected in 1911 describe it as humid forest with abundant epi-

phytes, but apparently some clearings with second-growth vegetation also

occurred; it is not clear exactly in which habitat the specimens were obtained

(Chapman 1917). Old-growth forest in our study site is restricted to inaccessible

slopes, which we did not survey.

Although G. milleri was abundant in our study site, its reduced geographical

and altitudinal range makes it extremely vulnerable (Kattan 1992). Even if the

species is distributed over all available habitats in the range 2,400-2,600 m in

Ucumari Regional Park and neighbouring watersheds, the total area is small

(probably in the range of 5,000 to 10,000 ha) and total population size is likely to

be in the range of a few thousand individuals. So far, our study population is

the only one known (Kattan and Beltran 1997). Surveys conducted in the late

1980s and early 1990s failed to find the species in its original localities (Collar et

al. 1992). However, G. milleri is difficult to record visually and its calls were

unknown. A one-year survey of the avifauna of Ucumari Regional Park con-

ducted in 1989 failed to detect this species (Naranjo 1994). Our first individual

was captured in 1994, after several months of continuous monitoring and mist-

netting (Kattan and Beltran 1997). Now that recordings of this species's calls

have been obtained, regional surveys should reveal the status of the species in

neighbouring watersheds.

Determining population size of G. rufocinerea is also of interest, as this species

is restricted to elevations of 2,400-3,150 m in the central range of the Colombian

Andes, where deforestation has removed much suitable habitat and fragmented

the species's range (Collar et al. 1992). Surveys at the Quindio River watershed

revealed a density of 1.6 to 5 individuals of this species per 10-km transect

between 2,500 and 3,150 m, with higher densities in "primary" forest at lower

altitudes (unpubl. data of L. M. Renjifo, cited in Collar et al. 1992). In our censuses

we found a density of ^.j individuals per kilometre in the 2,400-2,600 m range,

versus 3.7 ind/km in the 2,600-3,000 m range (Figure 2). Although at our site G.

rufocinerea had higher densities in forest than in early regeneration habitats, these

forests are 30 years old and far from mature. Therefore, this species exhibits some

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270900003452 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Gustavo H. Kattan and f. William Beltran 280

plasticity in habitat use and apparently has higher densities in second-

growth habitats, a characteristic that should help the species cope with the threat

of landscape transformation (Kattan 1992). The possibility exists, however, that

the species exhibits geographical variation in population density and habitat

selection, possibly in response to interactions with other species. Interestingly,

available data suggest that G. rufocinerea has higher population densities at its

lower elevational limit than at elevations closer to the centre of its altitudinal

range.

The concentration of Grallaria antpittas found in the Otun River watershed is

remarkable. Recently, G. alleni, another enigmatic species previously known from

only two specimens coming from two different localities in the Colombian

Andes, was rediscovered in the lower part of Ucumari Regional Park (1800 m;

L. M. Renjifo, pers. com.). In addition, it is likely that G. rufula and G. quitensis

are present at higher elevations (>3,ooo m) in the same watershed. Therefore, this

watershed concentrates six and possibly eight of the nine Grallaria species known

from the Central Andes of Colombia (Hilty and Brown 1986), including two

species for which these are the only known populations. Our studies have begun

to yield information on patterns of habitat use and abundance of these birds,

information that will be crucial for habitat management plans to ensure the per-

sistence of these populations.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Corporacion Autonoma Regional de Risaralda (CARDER), the gov-

ernment organization that manages Ucumari Regional Park, and in particular

Eduardo Londono, park director, and Carlos A. Carvajal, manager of La Pastora,

for logistical support at the park and for partially funding the project. Additional

funds came from the Fondo para la Protection del Medio Ambiente "Jose Celes-

tino Mutis"-FEN Colombia, the Instituto de Investigation de Recursos Biologicos

Alexander von Humboldt, and a grant from the MacArthur Foundation through

Wildlife Conservation Society. Thanks to Saulo Usma, Alexandra Aparicio,

Victor Serrano, Alberto Galindo and Monica Parada for help during different

phases of the fieldwork. Special thanks to Carolina Murcia for critical advice and

for being a source of inspiration during all phases of the project.

References

Block, W. M. and Brennan, L. A. (1993) The habitat concept in ornithology: theory and

applications. Curr. Orn. 11: 35-91.

Chapman, F. M. (1917) The distribution of bird life in Colombia: a contribution to a biolo-

gical survey of South America. Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. 36: 1-729.

Collar, N. ]., Gonzaga, L. P., Krabbe, N., Madrono Nieto, A., Naranjo, L. G., Parker, T. A.

and Wege, D. C. (1992) Threatened birds of the Americas. The ICBP/1UCN Red Data Book.

Third edition (Part 2). Cambridge, U.K.: International Council for Bird Preservation.

Franzreb, K. E. (1981) A comparative analysis of territorial mapping and variable-strip

transect censusing methods. Stud. Avian Biol. 6: 164-169.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270900003452 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Habitat use and abundance of antpittas 281

Fretwell, S. D. and Lucas, H. L. (1970) On territorial behavior and other factors influencing

habitat distribution in birds. I. Theoretical development. Ada Biotheor. 19: 16-36.

Graves, G. R. (1987) A cryptic new species of antpitta (Formicariidae: Grallaria) from the

Peruvian Andes. Wilson Bull. 99: 313-321.

Hilty, S. L. and Brown, W. L. (1986) A guide to the birds of Colombia. Princeton, N. J.:

Princeton University Press.

Kattan, G. H. (1992) Rarity and vulnerability: the birds of the Cordillera Central of Colom-

bia. Conserv. Biol. 6: 64-70.

Kattan, G. H. and Beltran, J. W. (1997) Rediscovery and status of the Brown-banded

Antpitta Grallaria milleri in the Central Andes of Colombia. Bird Conserv. Internatl. 7:

367-371.

Londono, E. (1994) Parque Regional Natural Ucumari, un vistazo historico. Pp. 13-21 in

J. O. Rangel, ed. Ucumari: un caso tipico de la diversidad biotica andina. Pereira, Colombia:

Corporation Autonoma Regional de Risaralda.

Martin, T. E. (1986) Competition in breeding birds: on the importance of considering pro-

cesses at the level of the individual. Curr. Orn. 4: 181-210.

Murcia, C. (1997) Evaluation of Andean alder as a catalyst for the recovery of tropical

cloud forests in Colombia. Forest Ecol. Mgmt. 99: 163-170.

Naranjo, L. G. (1994) Composition y estructura de la avifauna del Parque Regional Nat-

ural Ucumari. Pp. 305-325 in J. O. Rangel, ed. Ucumari: un caso tipico de la diversidad

biotica andina. Pereira, Colombia: Corporation Autonoma Regional de Risaralda.

Rangel, J. O. and Garzon, A. (1994) Aspectos de la estructura, de la diversidad y de la

dinamica de la vegetation del Parque Regional Natural Ucumari. Pp. 85-108 in J. O.

Rangel, ed. Ucumari: un caso tipico de la diversidad biotica andina. Pereira, Colombia: Cor-

poration Autonoma Regional de Risaralda.

Remsen, J. V. and Graves, W. S. (1995a) Distribution patterns and zoogeography of Atlap-

etes brush-finches (Emberizinae) of the Andes. Auk 112: 210-224.

Remsen, J. V. and Graves, W. S. (1995b) Distribution patterns of Buarremon brush-finches

(Emberizinae) and interspecific competition in Andean birds. Auk 112: 225-236.

Renjifo, L. M. and Andrade, G. I. (1987) Estudio comparativo de la avifauna entre un area

de bosque andino primario y un crecimiento secundario en el Quindio, Colombia.

Pp. 121-127 m H. Alvarez-Lopez, G. Kattan and C. Murcia, eds. Memorias del Tercer

Congreso de Ornitologia Neotropical. Cali, Colombia: Sociedad Vallecaucana de Ornitolo-

gia and Universidad del Valle.

Ridgely, R. and Tudor, G. (1994) The birds of South America, 2. The Suboscine Passerines.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schulenberg, T. S. and Williams, M. D. (1982) A new species of antpitta (Grallaria) from

northern Peru. Wilson Bull. 94: 105-113.

Stiles, F. G. (1992) A new species of antpitta (Formicariidae: Grallaria) from the Eastern

Andes of Colombia. Wilson Bull. 104: 389-399.

Stiles, F. G. and Alvarez-Lopez, H. (1995) La situation del tororoi pechicanela (Grallaria

haplonota, Formicariidae) en Colombia. Caldasia 17: 607-610.

Wiens, J. A. (1989) The ecology of bird communities, 1. Foundations and patterns. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

GUSTAVO H. KATTAN

Fundacidn EcoAndina/Wildlife Conservation Society-Colombia Program, Apartado 25527, Cali,

Colombia. E-mail: gukattan@cali.cetcol.net.co

J. WILLIAM BELTRAN

Fundacidn EcoAndina, Apartado 2552/, Cali, Colombia.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270900003452 Published online by Cambridge University Press

You might also like

- ESS - TOPIC 6 SummaryDocument7 pagesESS - TOPIC 6 SummaryMichaella SallesNo ratings yet

- 2012 APES Water Quailty TESTDocument5 pages2012 APES Water Quailty TESTKumari Small100% (1)

- Freile Et Al. 2011. Royal Sunangel in The Nangaritza ValleyDocument9 pagesFreile Et Al. 2011. Royal Sunangel in The Nangaritza ValleyOswaldo JadanNo ratings yet

- Peyton, 1980, Ecology, Distribution, and Food Habits of Spectacled Bears, Tremarctos Ornatus, in PeruDocument16 pagesPeyton, 1980, Ecology, Distribution, and Food Habits of Spectacled Bears, Tremarctos Ornatus, in PeruCesar Chavez IglesiasNo ratings yet

- Moss Types in Western GhatsDocument16 pagesMoss Types in Western GhatsgetnaniNo ratings yet

- Relox and Camino Agusan Marsh PDFDocument10 pagesRelox and Camino Agusan Marsh PDFFritzie AtesNo ratings yet

- Murree Biodiversity Park 2011Document39 pagesMurree Biodiversity Park 2011Engineering discoveryNo ratings yet

- Rco 36 2020 5Document10 pagesRco 36 2020 5dariomaciel1434No ratings yet

- Montilla 2021Document24 pagesMontilla 2021Raiza Nathaly Castañeda BonillaNo ratings yet

- Administrator, Composicion y Estructura de Quiroì Pteros de Una Localidad Piemontana de La Cordillera Nororiental de EcuadorDocument15 pagesAdministrator, Composicion y Estructura de Quiroì Pteros de Una Localidad Piemontana de La Cordillera Nororiental de EcuadorStefany CarriónNo ratings yet

- Saavedra-Rodríguez - Et - Al 2012Document9 pagesSaavedra-Rodríguez - Et - Al 2012Camilo HerreraNo ratings yet

- Pethiyagoda and Manamendra-Arachchi. 2012. Amphibians in Primary and Secondary Forest (Richness, Abundance, Species Table)Document8 pagesPethiyagoda and Manamendra-Arachchi. 2012. Amphibians in Primary and Secondary Forest (Richness, Abundance, Species Table)Alejandra CardonaNo ratings yet

- The Conifers of Chile An Overview of Their Distribution and EcologyDocument6 pagesThe Conifers of Chile An Overview of Their Distribution and EcologyjorgeNo ratings yet

- Paper Conservacion Menoreh HillsDocument9 pagesPaper Conservacion Menoreh HillsEstibaliz LopezNo ratings yet

- Herpetological ObservationsDocument21 pagesHerpetological ObservationsshettisohanNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity HotspotsDocument50 pagesBiodiversity HotspotsKaushik InamdarNo ratings yet

- Art27v56n1 PDFDocument15 pagesArt27v56n1 PDFSergio Alejandro CastroNo ratings yet

- Bonillaetal 2014Document15 pagesBonillaetal 2014biochoriNo ratings yet

- 1234 2372 2 PBDocument10 pages1234 2372 2 PBHusnah Tul KhatimahNo ratings yet

- ButterflyDocument17 pagesButterflyRizki MufidayantiNo ratings yet

- 120694-Article Text-180151-1-10-20200226 PDFDocument13 pages120694-Article Text-180151-1-10-20200226 PDFJorgePanNo ratings yet

- Kumara Et Al. 2023 WG MammalsDocument12 pagesKumara Et Al. 2023 WG Mammalslatha_ravikumarNo ratings yet

- Brightsmith and Bravo Ecology and Nesting of Ararauna 2006Document17 pagesBrightsmith and Bravo Ecology and Nesting of Ararauna 2006Jeff CremerNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity Hotspots in IndiaDocument10 pagesBiodiversity Hotspots in IndiaTapan Kumar PalNo ratings yet

- 07 - Chapter 1Document31 pages07 - Chapter 1anashwara.pillaiNo ratings yet

- Sundaland Heath Forests - Ecoregions - WWFDocument4 pagesSundaland Heath Forests - Ecoregions - WWFErna Karlinna D. YanthyNo ratings yet

- Amphibians Diversity of Beraliya Mukalana Forest (Sri Lanka)Document5 pagesAmphibians Diversity of Beraliya Mukalana Forest (Sri Lanka)D.M.S. Suranjan KarunarathnaNo ratings yet

- A Biodiversity HopspotDocument6 pagesA Biodiversity HopspotJessica DaviesNo ratings yet

- 1022-Texto Del Artículo-3581-5-10-20210831Document13 pages1022-Texto Del Artículo-3581-5-10-20210831Tony Huco GuiliNo ratings yet

- EVS Notes - Hotspots of BiodiversityDocument4 pagesEVS Notes - Hotspots of BiodiversityMax WellNo ratings yet

- JWMG 740Document9 pagesJWMG 740Diego UgarteNo ratings yet

- Dietz 1997Document17 pagesDietz 1997lassaad.el.hanafiNo ratings yet

- Proposa LDocument19 pagesProposa LLea Joy CagbabanuaNo ratings yet

- Winter Avian Population of River Brahmaputra in Dibrugarh, Assam, IndiaDocument3 pagesWinter Avian Population of River Brahmaputra in Dibrugarh, Assam, IndiaUtpal Singha RoyNo ratings yet

- Atlantic Forest - Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, UruguayDocument6 pagesAtlantic Forest - Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, Uruguaythe Kong of theNo ratings yet

- On The Ecology and Behavior of Cebus Albifrons. I. EcologyDocument16 pagesOn The Ecology and Behavior of Cebus Albifrons. I. EcologyMiguel LessaNo ratings yet

- Habitat Use, Fruit Consumption, and Population Density of The Black-Headed Night Monkey, AotusDocument7 pagesHabitat Use, Fruit Consumption, and Population Density of The Black-Headed Night Monkey, AotussdfaegwegewgNo ratings yet

- Birds of Dibru Saikhowa National Park AnDocument11 pagesBirds of Dibru Saikhowa National Park AnnabaphukanasmNo ratings yet

- The Use of Camera Traps For Estimating Jaguar Panthera Onca Abundance and Density Using Capture/recapture AnalysisDocument7 pagesThe Use of Camera Traps For Estimating Jaguar Panthera Onca Abundance and Density Using Capture/recapture AnalysisJidas20071994No ratings yet

- The Journal of Wildlife Management 78 (6) 1078-1086 2014 DOI 10.1002jwmg.740Document9 pagesThe Journal of Wildlife Management 78 (6) 1078-1086 2014 DOI 10.1002jwmg.740mean droNo ratings yet

- JACOMASSA, F. A. F. 2010. Espécies Arbóreas Nativas Da Mata Ciliar Da Bacia Hidrográfica Do Rio Lajeado Tunas, Na Região Do Alto Uruguai, RS PDFDocument6 pagesJACOMASSA, F. A. F. 2010. Espécies Arbóreas Nativas Da Mata Ciliar Da Bacia Hidrográfica Do Rio Lajeado Tunas, Na Região Do Alto Uruguai, RS PDFFábio André Facco JacomassaNo ratings yet

- Riqueza de Especies y Gremios Tróficos de CarnívorosDocument14 pagesRiqueza de Especies y Gremios Tróficos de CarnívorosDaniel Moncayo LassoNo ratings yet

- Koenig BBPA BCI 2001Document22 pagesKoenig BBPA BCI 2001Zineil BlackwoodNo ratings yet

- Global Population Decline of The Great Slaty Woodpecker (Mulleripicus Pulverulentus)Document14 pagesGlobal Population Decline of The Great Slaty Woodpecker (Mulleripicus Pulverulentus)Chitoge GremoryNo ratings yet

- 2003 Wasman IndicatorDocument6 pages2003 Wasman IndicatorMARIA FERNANDA RONDONNo ratings yet

- Horgan2002 PDFDocument12 pagesHorgan2002 PDFJosé CeaNo ratings yet

- A Comparison On The Response To Forest Fragmentation 2002 Virgos Et AlDocument18 pagesA Comparison On The Response To Forest Fragmentation 2002 Virgos Et AlLucía SolerNo ratings yet

- Biodiversity Hotspots in IndiaDocument20 pagesBiodiversity Hotspots in IndiaRajat VermaNo ratings yet

- Food Habits of Jaguars and Pumas in Jalisco, MexicoDocument7 pagesFood Habits of Jaguars and Pumas in Jalisco, MexicoNorelyNo ratings yet

- The Avifauna of The Polylepis Woodlands of The Andean Highlands The Efficiency of Basing Conservation Priorities On Patterns of EndemismDocument19 pagesThe Avifauna of The Polylepis Woodlands of The Andean Highlands The Efficiency of Basing Conservation Priorities On Patterns of EndemismANABETH SALAS CONDORINo ratings yet

- Anfibico Villavicencio LYNCH 2006Document21 pagesAnfibico Villavicencio LYNCH 2006Gestión Documental BioApNo ratings yet

- Biological Resources of The Ayuquila-Armeria RiverDocument2 pagesBiological Resources of The Ayuquila-Armeria RiverGerencia OperativaNo ratings yet

- 25 Hot SpotsDocument3 pages25 Hot Spotsx5trawb3rriNo ratings yet

- Richness of Plants Birds and Mammals UndDocument10 pagesRichness of Plants Birds and Mammals UndvivilanciaNo ratings yet

- Significant Records of Birds in Forests On Cebu Island, Central PhilippinesDocument9 pagesSignificant Records of Birds in Forests On Cebu Island, Central Philippinescarlos surigaoNo ratings yet

- Arbelaez Cortes - 2011 - FrontinoDocument8 pagesArbelaez Cortes - 2011 - FrontinoJulian David Muñoz OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Mt. ApoDocument5 pagesMt. ApoMaria ChristineNo ratings yet

- Namgail BirdsDocument3 pagesNamgail BirdsnamgailNo ratings yet

- 02cueva EtalDocument16 pages02cueva EtalLEMA HERNANDEZ ALICIA FERNANDANo ratings yet

- Peruvian Yellow-Tailed Woolly Monkey: Peru (2000, 2006, 2008)Document3 pagesPeruvian Yellow-Tailed Woolly Monkey: Peru (2000, 2006, 2008)Henry QiuNo ratings yet

- Agroecology As A Means To Transform The Food System: Position PaperDocument6 pagesAgroecology As A Means To Transform The Food System: Position PaperSebastian Clavijo BarcoNo ratings yet

- GM in Sustainable Land Management UndpDocument10 pagesGM in Sustainable Land Management UndpSimon OpolotNo ratings yet

- Debate Supporting DocumentsDocument11 pagesDebate Supporting DocumentsPace Christine Mae Anne C.No ratings yet

- Geography 2021Document2 pagesGeography 2021KhanNo ratings yet

- Climate Risks in The Agriculture Sector: Insights For Financial InstitutionsDocument60 pagesClimate Risks in The Agriculture Sector: Insights For Financial InstitutionsIdowuNo ratings yet

- Outlining An Issue You Have With Your Local AreaDocument2 pagesOutlining An Issue You Have With Your Local AreaPalliNo ratings yet

- اهم مواضيع التعبير للصف الثالث الاعدادي الترم الثانيDocument13 pagesاهم مواضيع التعبير للصف الثالث الاعدادي الترم الثانيKhaled ElgabryNo ratings yet

- What Is The Oxygen Cycle?: Human BodyDocument5 pagesWhat Is The Oxygen Cycle?: Human BodyJEANY ROSE CUEVASNo ratings yet

- Chapter-03 Hydrologic LossesDocument65 pagesChapter-03 Hydrologic LossesFendy RoynNo ratings yet

- A11 (PPO) Project ProposalDocument6 pagesA11 (PPO) Project ProposalCejesskaCushAlday100% (1)

- Assessment of Organic Farming For The Development of Agricultural Sustainability: A Case Study of Sikkim State (India)Document25 pagesAssessment of Organic Farming For The Development of Agricultural Sustainability: A Case Study of Sikkim State (India)chthakorNo ratings yet

- Salient Features of Deras M.I.P. (Reservoir) : 1 LocationDocument3 pagesSalient Features of Deras M.I.P. (Reservoir) : 1 LocationAntariksha NayakNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Rooftop Rainwater in JordanDocument103 pagesEvaluation of Rooftop Rainwater in JordanTilahun TegegneNo ratings yet

- Topic: Tourism Promotes Environmental Awareness & Sustainability Through Port Moresby Nature ParkDocument22 pagesTopic: Tourism Promotes Environmental Awareness & Sustainability Through Port Moresby Nature Parkkaam tomsonNo ratings yet

- Lesson-Plan-Carbon FootprintDocument7 pagesLesson-Plan-Carbon FootprintGisela GularteNo ratings yet

- Letter of MotivationDocument2 pagesLetter of MotivationMuhammad talha100% (2)

- Exotic, Invasive, Alien, Nonindigenous, or Nuisance Species: No Matter What You Call Them, They're A Growing ProblemDocument2 pagesExotic, Invasive, Alien, Nonindigenous, or Nuisance Species: No Matter What You Call Them, They're A Growing ProblemGreat Lakes Environmental Research LaboratoryNo ratings yet

- Hydrology PDFDocument6 pagesHydrology PDFMohan Subhashkoneti KonetiNo ratings yet

- Science 4-Week 7 S4MT-Ii-j-7: Describe The Harmful Effects of The Changes in The Materials To The EnvironmentDocument12 pagesScience 4-Week 7 S4MT-Ii-j-7: Describe The Harmful Effects of The Changes in The Materials To The Environmentsarah ventura100% (1)

- Hydrology: CHYDR0320Document12 pagesHydrology: CHYDR0320KrischanSayloGelasanNo ratings yet

- BonnDocument14 pagesBonnsaaisNo ratings yet

- 1.3.3 BBA ENVS ProjectDocument157 pages1.3.3 BBA ENVS ProjectnandanasindubijupalNo ratings yet

- Central AravaDocument31 pagesCentral Aravadonhan91No ratings yet

- Đề thi vào 10- Chuyên Anh Thái Bình năm 2021-2022Document17 pagesĐề thi vào 10- Chuyên Anh Thái Bình năm 2021-2022Đức Duy PhạmNo ratings yet

- Community and Environmental HealthDocument29 pagesCommunity and Environmental HealthKathrina Lingad100% (2)

- World Enviornment DayDocument9 pagesWorld Enviornment DayNeeraj KumarNo ratings yet

- Social Studies Junior 2020-2021 Instructional Pacing Guide Social Studies, An in Egra Ed ApproachDocument21 pagesSocial Studies Junior 2020-2021 Instructional Pacing Guide Social Studies, An in Egra Ed ApproachAbdulkadir NuhNo ratings yet

- Climate Change Essay 8 Milton English Q1 W4Document4 pagesClimate Change Essay 8 Milton English Q1 W4Shariah RicoNo ratings yet