Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hypotheses

Hypotheses

Uploaded by

Diego Gallegos lopezCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Drawing Out ImplicationsDocument2 pagesDrawing Out ImplicationsArjay LusterioNo ratings yet

- Organizing Scientific Thinking Using The Qualmri Framework: Part 1: Qualmri in DepthDocument10 pagesOrganizing Scientific Thinking Using The Qualmri Framework: Part 1: Qualmri in DepthLuisSanchezNo ratings yet

- Selenium Interview Questions - CognizantDocument20 pagesSelenium Interview Questions - CognizantJessie SokhiNo ratings yet

- CH 5 Test BankDocument75 pagesCH 5 Test BankJB50% (2)

- SAP FICO MaterialDocument24 pagesSAP FICO MaterialNeelam Singh100% (1)

- NumerologyDocument24 pagesNumerologyphani60% (5)

- Psychology Research Paper HypothesisDocument4 pagesPsychology Research Paper Hypothesisafmcifezi100% (1)

- Hypothesis in Research Paper MeaningDocument7 pagesHypothesis in Research Paper MeaningPaperWriterAtlanta100% (2)

- Hypothesis in Research MeansDocument5 pagesHypothesis in Research MeansEssayHelpEugene100% (1)

- Thesis Proposal Hypothesis SampleDocument7 pagesThesis Proposal Hypothesis SampleKaren Gomez100% (2)

- Example of Hypothesis in Research WritingDocument6 pagesExample of Hypothesis in Research Writingmichelledavisvirginiabeach100% (1)

- Where To Put The Hypothesis in A Research PaperDocument8 pagesWhere To Put The Hypothesis in A Research Paperdeniseenriquezglendale100% (2)

- Developing A Hypothesis For A Research PaperDocument5 pagesDeveloping A Hypothesis For A Research Papermindischneiderfargo100% (1)

- Psychology Research Paper HypothesisDocument6 pagesPsychology Research Paper Hypothesissharonleespringfield100% (2)

- Research QuestionDocument9 pagesResearch Questionvirendra singhNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Hypothesis FormatDocument4 pagesResearch Paper Hypothesis Formatafmcsmvbr100% (1)

- Dissertation Research Hypothesis ExamplesDocument5 pagesDissertation Research Hypothesis ExamplesCollegePaperWritingServicesUK100% (2)

- How To Write A Research Paper On A Medical ConditionDocument5 pagesHow To Write A Research Paper On A Medical ConditionafmcapeonNo ratings yet

- Purpose of ResearchDocument3 pagesPurpose of ResearchPRINTDESK by DanNo ratings yet

- Types of Hypothesis in Research PaperDocument7 pagesTypes of Hypothesis in Research PaperAndrew Molina100% (2)

- Introduction in Psychology Research PaperDocument7 pagesIntroduction in Psychology Research Papergazqaacnd100% (1)

- Psychology Research Paper Hypothesis ExamplesDocument8 pagesPsychology Research Paper Hypothesis Examplesfzpabew4100% (1)

- Where Is The Hypothesis Found in A Research PaperDocument8 pagesWhere Is The Hypothesis Found in A Research Papergzzjhsv9No ratings yet

- How To Include A Hypothesis in A Research PaperDocument5 pagesHow To Include A Hypothesis in A Research Paperafeascdcz100% (1)

- Sample Research Paper in Experimental PsychologyDocument6 pagesSample Research Paper in Experimental PsychologyzrpcnkrifNo ratings yet

- Define Hypothesis in Research PaperDocument4 pagesDefine Hypothesis in Research Paperkarennelsoncolumbia100% (2)

- The Research QuestionDocument9 pagesThe Research QuestionReyna Glorian HilarioNo ratings yet

- ANAS - First ExaminationDocument26 pagesANAS - First ExaminationRUEL ANASNo ratings yet

- What Is Hypothesis in Dissertation ProposalDocument6 pagesWhat Is Hypothesis in Dissertation ProposalCustomWritingPapersKnoxville100% (1)

- Journal Club Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesJournal Club Literature Reviewakjnbowgf100% (1)

- Lecture 2a-Research ProblemDocument31 pagesLecture 2a-Research ProblemRida Wahyuningrum Goeridno DarmantoNo ratings yet

- Basic Vs Applied ResearchDocument8 pagesBasic Vs Applied ResearchMasoom NaeemNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics About MedicineDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Topics About Medicineqmgqhjulg100% (1)

- UGML JAMA - I - How To Get StartedDocument3 pagesUGML JAMA - I - How To Get StartedAlicia WellmannNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Vs Secondary DataDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Vs Secondary Datac5t0jsyn100% (1)

- Health Science Literature Review ExampleDocument7 pagesHealth Science Literature Review Exampleafdtszfwb100% (1)

- How Do You Write A Hypothesis For A Research PaperDocument6 pagesHow Do You Write A Hypothesis For A Research Paperlucycastilloelpaso100% (2)

- Thesis Statement On Diet PillsDocument4 pagesThesis Statement On Diet PillsPaySomeoneToWriteAPaperCanada100% (2)

- Dissertation Research Question HypothesisDocument4 pagesDissertation Research Question HypothesisWriteMyPaperForMoneyTulsa100% (1)

- How To Include Hypothesis in Research PaperDocument5 pagesHow To Include Hypothesis in Research Papertiffanygrahamkansascity100% (2)

- How To Conduct Meta AnalysisDocument15 pagesHow To Conduct Meta AnalysisJuniza JubriNo ratings yet

- How To Find A Hypothesis in A Research PaperDocument8 pagesHow To Find A Hypothesis in A Research Papervstxevplg100% (1)

- Research ProcessDocument7 pagesResearch Processangelicadecipulo0828No ratings yet

- PR2 Study NotesDocument9 pagesPR2 Study NotesLayza Mea ArdienteNo ratings yet

- Ocd Thesis QuestionDocument8 pagesOcd Thesis QuestionBuyEssaysOnlineForCollegeSiouxFalls100% (1)

- Formulating The Research Problem Steps of The Scientific Process Literature ReviewDocument12 pagesFormulating The Research Problem Steps of The Scientific Process Literature ReviewIzzat RahmanNo ratings yet

- Sample Research Paper MedicineDocument6 pagesSample Research Paper Medicineclwdcbqlg100% (1)

- Hypothesis in Research Paper DefinitionDocument8 pagesHypothesis in Research Paper Definitiontrinajacksonjackson100% (1)

- Medical Research Paper ExamplesDocument4 pagesMedical Research Paper Examplesluwop1gagos3No ratings yet

- Research Paper On PsychologistDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Psychologistp0zikiwyfyb2100% (1)

- Developing Great Research QuestionsDocument5 pagesDeveloping Great Research QuestionsEduardo MirandaNo ratings yet

- Medical Research Paper ExampleDocument7 pagesMedical Research Paper Examplegvzwyd4n100% (1)

- RISSC201Document81 pagesRISSC201Vinancio ZungundeNo ratings yet

- Hypothesis and ThesisDocument5 pagesHypothesis and ThesisBuyAPaperOnlineUK100% (2)

- Good Medical Research Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesGood Medical Research Paper Topicsn1dihagavun2100% (1)

- Identifying Hypothesis in Research PaperDocument6 pagesIdentifying Hypothesis in Research PaperBuyCustomEssaysOnlineOmaha100% (3)

- Nursing Research Thesis TitlesDocument7 pagesNursing Research Thesis Titlesjuliepatenorman100% (2)

- How To Critically ReviewDocument2 pagesHow To Critically ReviewAndika SaputraNo ratings yet

- Example of Introduction in Psychology Research PaperDocument6 pagesExample of Introduction in Psychology Research Paperefjem40qNo ratings yet

- Experimental Psychology Research Paper SampleDocument7 pagesExperimental Psychology Research Paper Sampleeffbd7j4100% (1)

- 3is Q1 Module 2 - Removed - RemovedDocument6 pages3is Q1 Module 2 - Removed - RemovedDavid King AvilaNo ratings yet

- How Read Papers That Go Beyond Numbers (Qualitative Research)Document24 pagesHow Read Papers That Go Beyond Numbers (Qualitative Research)Muhammad Bilal SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Research Paper IntroductionDocument8 pagesHealthcare Research Paper Introductiontqpkpiukg100% (1)

- Redistribution and PBRDocument1 pageRedistribution and PBRdibpalNo ratings yet

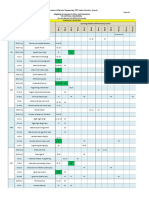

- Mapping PEC 2021-Oct-20 Annex-D Courses Vs PLO Vs TaxonomyDocument2 pagesMapping PEC 2021-Oct-20 Annex-D Courses Vs PLO Vs TaxonomyEngr.Mohsin ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Invoice: PT - Sitc IndonesiaDocument1 pageInvoice: PT - Sitc IndonesiaMuhammad SyukurNo ratings yet

- 2021 HhhhhhhterqasdwqwDocument1 page2021 HhhhhhhterqasdwqwHassan KhanNo ratings yet

- Supra AccessoryDocument7 pagesSupra AccessoryaeroglideNo ratings yet

- Stamens PDFDocument10 pagesStamens PDFAmeya KannamwarNo ratings yet

- Itcc Comm. Center Bms Io PGDocument3 pagesItcc Comm. Center Bms Io PGuddinnadeemNo ratings yet

- Skript Version30 PDFDocument90 pagesSkript Version30 PDFNguyễn TúNo ratings yet

- 1884 Journey From Heraut To Khiva Moscow and ST Petersburgh Vol 2 by Abbott S PDFDocument342 pages1884 Journey From Heraut To Khiva Moscow and ST Petersburgh Vol 2 by Abbott S PDFBilal AfridiNo ratings yet

- The Migration Industry and Future Directions For Migration PolicyDocument4 pagesThe Migration Industry and Future Directions For Migration PolicyGabriella VillaçaNo ratings yet

- TGDocument180 pagesTGavikram1984No ratings yet

- Recruitment & Selection Reliance Jio Full Report - 100 Page MANU SHARMA MBA 3rd SEMDocument102 pagesRecruitment & Selection Reliance Jio Full Report - 100 Page MANU SHARMA MBA 3rd SEMImpression Graphics100% (4)

- Curriculum Ucv SedapalDocument2 pagesCurriculum Ucv SedapalSheyler Alvarado SanchezNo ratings yet

- Compal Confidential: QIWG7 DIS M/B Schematics DocumentDocument5 pagesCompal Confidential: QIWG7 DIS M/B Schematics DocumentКирилл ГулякевичNo ratings yet

- Activation of Bacterial Spores. A Review': I G RminaDocument7 pagesActivation of Bacterial Spores. A Review': I G RminaJunegreg CualNo ratings yet

- Operation & Maintenance Manual: Diesel Vehicle EngineDocument158 pagesOperation & Maintenance Manual: Diesel Vehicle Engineالمعز محمد عبد الرحمن100% (1)

- Magazines ListDocument11 pagesMagazines ListSheshadri Kattepur NagarajNo ratings yet

- Peek - POLYETHER ETHER KETONEDocument58 pagesPeek - POLYETHER ETHER KETONEBryan Jesher Dela Cruz100% (1)

- MATHEMATICS WEEK3 2nd GRADE 4Document11 pagesMATHEMATICS WEEK3 2nd GRADE 4Jonah A. RecioNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Trajectory Model For Differential Steering Using Numerical MethodDocument6 pagesEvaluation of Trajectory Model For Differential Steering Using Numerical MethodNaufal RachmatullahNo ratings yet

- Longest Common SubstringDocument33 pagesLongest Common SubstringHelton DuarteNo ratings yet

- 5db83ef1f71e482 PDFDocument192 pages5db83ef1f71e482 PDFRajesh RoyNo ratings yet

- Project MarketingDocument88 pagesProject MarketingAnkita DhimanNo ratings yet

- EScan Corporate 360 UGDocument601 pagesEScan Corporate 360 UG11F10 RUCHITA MAARANNo ratings yet

- Dictionary View Objects: Dict - Keys Dict - Values Dict - ItemsDocument6 pagesDictionary View Objects: Dict - Keys Dict - Values Dict - Itemssudhir RathodNo ratings yet

- Eb 12Document25 pagesEb 12SrewaBenshebilNo ratings yet

Hypotheses

Hypotheses

Uploaded by

Diego Gallegos lopezOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hypotheses

Hypotheses

Uploaded by

Diego Gallegos lopezCopyright:

Available Formats

This single copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only.

For permission to reprint multiple copies or to order presentation-ready copies for distribution, contact CJHP at cjhpedit@cshp.ca

RESEARCH PRIMER

Research: Articulating Questions, Generating

Hypotheses, and Choosing Study Designs

Mary P Tully

INTRODUCTION not find a published answer to the question you were asked,

and so you want to conduct some research yourself. However,

A rticulating a clear and concise research question is funda-

mental to conducting a robust and useful research study.

Although “getting stuck into” the data collection is the exciting

just searching the literature to generate questions is not to be

recommended for novices—the volume of material can feel

totally overwhelming.

part of research, this preparation stage is crucial. Clear and Use a research notebook, where you regularly write ideas

concise research questions are needed for a number of reasons. for research questions as you think of them during your clinical

Initially, they are needed to enable you to search the literature practice or after reading other research papers. It has been said

effectively. They will allow you to write clear aims and generate that the best way to have a great idea is to have lots of ideas

hypotheses. They will also ensure that you can select the most and then choose the best. The same would apply to research

appropriate research design for your study. questions!

When you first identify your area of research interest, it is

This paper begins by describing the process of articulating

likely to be either too narrow or too broad. Narrow questions

clear and concise research questions, assuming that you have

(such as “How is drug X prescribed for patients with condition

minimal experience. It then describes how to choose research Y in my hospital?”) are usually of limited interest to anyone

questions that should be answered and how to generate study other than the researcher. Broad questions (such as “How can

aims and hypotheses from your questions. Finally, it describes pharmacists provide better patient care?”) must be broken

briefly how your question will help you to decide on the down into smaller, more manageable questions. If you are

research design and methods best suited to answering it. interested in how pharmacists can provide better care, for

example, you might start to narrow that topic down to how

TURNING CURIOSITY INTO QUESTIONS pharmacists can provide better care for one condition (such as

affective disorders) for a particular subgroup of patients (such

A research question has been described as “the uncertainty

as teenagers). Then you could focus it even further by consid-

that the investigator wants to resolve by performing her study”1

ering a specific disorder (depression) and a particular type of

or “a logical statement that progresses from what is known or

service that pharmacists could provide (improving patient

believed to be true to that which is unknown and requires val-

adherence). At this stage, you could write your research

idation”.2 Developing your question usually starts with having

question as, for example, “What role, if any, can pharmacists

some general ideas about the areas within which you want to do

play in improving adherence to fluoxetine used for depression

your research. These might flow from your clinical work, for

in teenagers?”

example. You might be interested in finding ways to improve

the pharmaceutical care of patients on your wards. Alternatively,

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS

you might be interested in identifying the best antihypertensive

agent for a particular subgroup of patients. Lipowski2 described Being able to consider the type of research question that

in detail how work as a practising pharmacist can be used to you have generated is particularly useful when deciding what

great advantage to generate interesting research questions and research methods to use. There are 3 broad categories of

hence useful research studies. Ideas could come from question- question: descriptive, relational, and causal.

ing received wisdom within your clinical area or the rationale

behind quick fixes or workarounds, or from wanting to Descriptive

improve the quality, safety, or efficiency of working practice.

Alternatively, your ideas could come from searching the One of the most basic types of question is designed to ask

literature to answer a query from a colleague. Perhaps you could systematically whether a phenomenon exists. For example, we

C J H P – Vol. 67, No. 1 – January–February 2014 J C P H – Vol. 67, no 1 – janvier–février 2014 31

This single copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only.

For permission to reprint multiple copies or to order presentation-ready copies for distribution, contact CJHP at cjhpedit@cshp.ca

could ask “Do pharmacists ‘care’ when they deliver pharma- “Does captopril treatment reduce blood pressure?” Generally,

ceutical care?” This research would initially define the key terms however, if you ask a causality question about a medication or

(i.e., describing what “pharmaceutical care” and “care” are), and any other health care intervention, it ought to be rephrased as

then the study would set out to look for the existence of care at a causality–comparative question. Without comparing what

the same time as pharmaceutical care was being delivered. happens in the presence of an intervention with what happens

When you know that a phenomenon exists, you can then in the absence of the intervention, it is impossible to attribute

ask description and/or classification questions. The answers to causality to the intervention. Although a causality question

these types of questions involve describing the characteristics of would usually be answered using a comparative research design,

the phenomenon or creating typologies of variable subtypes. In asking a causality–comparative question makes the research

the study above, for example, you could investigate the charac- design much more explicit. So the above question could be

teristics of the “care” that pharmacists provide. Classifications rephrased as, “Is captopril better than placebo at reducing

usually use mutually exclusive categories, so that various sub- blood pressure?”

types of the variable will have an unambiguous category to The acronym PICO has been used to describe the

which they can be assigned. For example, a question could be components of well-crafted causality–comparative research

asked as to “what is a pharmacist intervention” and a definition questions.3 The letters in this acronym stand for Population,

and classification system developed for use in further research. Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome. They remind the

When seeking further detail about your phenomenon, you researcher that the research question should specify the type of

might ask questions about its composition. These questions participant to be recruited, the type of exposure involved, the

necessitate deconstructing a phenomenon (such as a behaviour) type of control group with which participants are to be

into its component parts. Within hospital pharmacy practice, compared, and the type of outcome to be measured. Using the

you might be interested in asking questions about the PICO approach, the above research question could be written

composition of a new behavioural intervention to improve as “Does captopril [intervention] decrease rates of cardiovascu-

patient adherence, for example, “What is the detailed process lar events [outcome] in patients with essential hypertension

that the pharmacist implicitly follows during delivery of this [population] compared with patients receiving no treatment

new intervention?” [comparison]?”

Relational DECIDING WHETHER TO ANSWER A

RESEARCH QUESTION

After you have described your phenomena, you may then

be interested in asking questions about the relationships Just because a question can be asked does not mean that it

between several phenomena. If you work on a renal ward, for needs to be answered. Not all research questions deserve to have

example, you may be interested in looking at the relationship time spent on them. One useful set of criteria is to ask whether

your research question is feasible, interesting, novel, ethical,

between hemoglobin levels and renal function, so your

and relevant.1 The need for research to be ethical will be

question would look something like this: “Are hemoglobin

covered in a later paper in the series, so is not discussed here.

levels related to level of renal function?” Alternatively, you may

The literature review is crucial to finding out whether the

have a categorical variable such as grade of doctor and be

research question fulfils the remaining 4 criteria.

interested in the differences between them with regard to

Conducting a comprehensive literature review will allow

prescribing errors, so your research question would be “Do

you to find out what is already known about the subject and

junior doctors make more prescribing errors than senior

any gaps that need further exploration. You may find that your

doctors?” Relational questions could also be asked within

research question has already been answered. However, that

qualitative research, where a detailed understanding of the

does not mean that you should abandon the question

nature of the relationship between, for example, the gender and

altogether. It may be necessary to confirm those findings using

career aspirations of clinical pharmacists could be sought.

an alternative method or to translate them to another setting. If

your research question has no novelty, however, and is not

Causal

interesting or relevant to your peers or potential funders, you

Once you have described your phenomena and have iden- are probably better finding an alternative.

tified a relationship between them, you could ask about the The literature will also help you learn about the research

causes of that relationship. You may be interested to know designs and methods that have been used previously and hence

whether an intervention or some other activity has caused a to decide whether your potential study is feasible. As a novice

change in your variable, and your research question would be researcher, it is particularly important to ask if your planned

about causality. For example, you may be interested in asking, study is feasible for you to conduct. Do you or your collabora-

32 C J H P – Vol. 67, No. 1 – January–February 2014 J C P H – Vol. 67, no 1 – janvier–février 2014

This single copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only.

For permission to reprint multiple copies or to order presentation-ready copies for distribution, contact CJHP at cjhpedit@cshp.ca

tors have the necessary technical expertise? Do you have the Similarly, if your question was, “Is captopril better than placebo

other resources that will be needed? If you are just starting out at reducing blood pressure?”, conducting a series of in-depth

with research, it is likely that you will have a limited budget, in qualitative interviews would be equally incapable of generating

terms of both time and money. Therefore, even if the question the necessary data. However, if these designs are swapped

is novel, interesting, and relevant, it may not be one that is around, we have 2 combinations (pharmaceutical care investi-

feasible for you to answer. gated using interviews; captopril investigated using a random-

ized controlled study) that are more likely to produce robust

GENERATING AIMS AND HYPOTHESES answers to the questions.

The language of the research question can be helpful in

All research studies should have at least one research deciding what research design and methods to use. Subsequent

question, and they should also have at least one aim. As a rule papers in this series will cover these topics in detail. For

of thumb, a small research study should not have more than example, if the question starts with “how many” or “how

2 aims as an absolute maximum. The aim of the study is a often”, it is probably a descriptive question to assess the

broad statement of intention and aspiration; it is the overall prevalence or incidence of a phenomenon. An epidemiological

goal that you intend to achieve. The wording of this broad research design would be appropriate, perhaps using a postal

statement of intent is derived from the research question. If it survey or structured interviews to collect the data. If the

is a descriptive research question, the aim will be, for example, question starts with “why” or “how”, then it is a descriptive

“to investigate” or “to explore”. If it is a relational research question to gain an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon.

question, then the aim should state the phenomena being A qualitative research design, using in-depth interviews or focus

correlated, such as “to ascertain the impact of gender on career groups, would collect the data needed. Finally, the term “what

aspirations”. If it is a causal research question, then the aim is the impact of” suggests a causal question, which would

should include the direction of the relationship being tested, require comparison of data collected with and without the

such as “to investigate whether captopril decreases rates of intervention (i.e., a before–after or randomized controlled

cardiovascular events in patients with essential hypertension, study).

relative to patients receiving no treatment”.

The hypothesis is a tentative prediction of the nature and CONCLUSIONS

direction of relationships between sets of data, phrased as a This paper has briefly outlined how to articulate research

declarative statement. Therefore, hypotheses are really only questions, formulate your aims, and choose your research

required for studies that address relational or causal research methods. It is crucial to realize that articulating a good research

questions. For the study above, the hypothesis being tested question involves considerable iteration through the stages

would be “Captopril decreases rates of cardiovascular events described above. It is very common that the first research

in patients with essential hypertension, relative to patients question generated bears little resemblance to the final question

receiving no treatment”. Studies that seek to answer descriptive used in the study. The language is changed several times, for

research questions do not test hypotheses, but they can be used example, because the first question turned out not to be

for hypothesis generation. Those hypotheses would then be feasible and the second question was a descriptive question

tested in subsequent studies. when what was really wanted was a causality question. The

books listed in the “Further Reading” section provide greater

CHOOSING THE STUDY DESIGN detail on the material described here, as well as a wealth of other

information to ensure that your first foray into conducting

The research question is paramount in deciding what research is successful.

research design and methods you are going to use. There are no

inherently bad research designs. The rightness or wrongness of References

1. Hulley S, Cummings S, Browner W, Grady D, Newman T. Designing clinical

the decision about the research design is based simply on research. 4th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2013.

whether it is suitable for answering the research question that 2. Lipowski EE. Developing great research questions. Am J Health Syst Pharm.

2008;65(17):1667-70.

you have posed. 3. Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built

It is possible to select completely the wrong research design clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;

to answer a specific question. For example, you may want to 123(3):A12-3.

answer one of the research questions outlined above: “Do Further Reading

pharmacists ‘care’ when they deliver pharmaceutical care?” Cresswell J. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches.

Although a randomized controlled study is considered by many London (UK): Sage; 2009.

Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. Clinical epidemiology: how to do

as a “gold standard” research design, such a study would just clinical practice research. 3rd ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins;

not be capable of generating data to answer the question posed. 2006.

C J H P – Vol. 67, No. 1 – January–February 2014 J C P H – Vol. 67, no 1 – janvier–février 2014 33

This single copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only.

For permission to reprint multiple copies or to order presentation-ready copies for distribution, contact CJHP at cjhpedit@cshp.ca

Kumar R. Research methodology: a step-by-step guide for beginners. 3rd ed. London Address correspondence to:

(UK): Sage; 2010. Dr Mary P Tully

Smith FJ. Conducting your pharmacy practice research project. London (UK): Manchester Pharmacy School

Pharmaceutical Press; 2005. University of Manchester

Oxford Road

Manchester M13 9PT UK

e-mail: Mary.tully@manchester.ac.uk

This article is the second in the CJHP Research Primer Series, an initia-

tive of the CJHP Editorial Board and the CSHP Research Committee.

Mary P Tully, PhD, is a Clinical Reader in Pharmacy Practice,

The planned 2-year series is intended to appeal to relatively inexperi-

Manchester Pharmacy School, University of Manchester, Manchester,

enced researchers, with the goal of building research capacity among

United Kingdom.

practising pharmacists. The articles, presenting simple but rigorous

Competing interests: Mary Tully has received personal fees from the guidance to encourage and support novice researchers, are being

UK Renal Pharmacy Group to present a conference workshop on solicited from authors with appropriate expertise.

writing research questions and nonfinancial support (in the form of

Previous article in this series:

travel and accommodation) from the Dubai International Pharmaceuti-

Bond CM. The research jigsaw: how to get started. Can J Hosp Pharm.

cals and Technologies Conference and Exhibition (DUPHAT) to present

2014;67(1):28-30.

a workshop on conducting pharmacy practice research.

34 C J H P – Vol. 67, No. 1 – January–February 2014 J C P H – Vol. 67, no 1 – janvier–février 2014

You might also like

- Drawing Out ImplicationsDocument2 pagesDrawing Out ImplicationsArjay LusterioNo ratings yet

- Organizing Scientific Thinking Using The Qualmri Framework: Part 1: Qualmri in DepthDocument10 pagesOrganizing Scientific Thinking Using The Qualmri Framework: Part 1: Qualmri in DepthLuisSanchezNo ratings yet

- Selenium Interview Questions - CognizantDocument20 pagesSelenium Interview Questions - CognizantJessie SokhiNo ratings yet

- CH 5 Test BankDocument75 pagesCH 5 Test BankJB50% (2)

- SAP FICO MaterialDocument24 pagesSAP FICO MaterialNeelam Singh100% (1)

- NumerologyDocument24 pagesNumerologyphani60% (5)

- Psychology Research Paper HypothesisDocument4 pagesPsychology Research Paper Hypothesisafmcifezi100% (1)

- Hypothesis in Research Paper MeaningDocument7 pagesHypothesis in Research Paper MeaningPaperWriterAtlanta100% (2)

- Hypothesis in Research MeansDocument5 pagesHypothesis in Research MeansEssayHelpEugene100% (1)

- Thesis Proposal Hypothesis SampleDocument7 pagesThesis Proposal Hypothesis SampleKaren Gomez100% (2)

- Example of Hypothesis in Research WritingDocument6 pagesExample of Hypothesis in Research Writingmichelledavisvirginiabeach100% (1)

- Where To Put The Hypothesis in A Research PaperDocument8 pagesWhere To Put The Hypothesis in A Research Paperdeniseenriquezglendale100% (2)

- Developing A Hypothesis For A Research PaperDocument5 pagesDeveloping A Hypothesis For A Research Papermindischneiderfargo100% (1)

- Psychology Research Paper HypothesisDocument6 pagesPsychology Research Paper Hypothesissharonleespringfield100% (2)

- Research QuestionDocument9 pagesResearch Questionvirendra singhNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Hypothesis FormatDocument4 pagesResearch Paper Hypothesis Formatafmcsmvbr100% (1)

- Dissertation Research Hypothesis ExamplesDocument5 pagesDissertation Research Hypothesis ExamplesCollegePaperWritingServicesUK100% (2)

- How To Write A Research Paper On A Medical ConditionDocument5 pagesHow To Write A Research Paper On A Medical ConditionafmcapeonNo ratings yet

- Purpose of ResearchDocument3 pagesPurpose of ResearchPRINTDESK by DanNo ratings yet

- Types of Hypothesis in Research PaperDocument7 pagesTypes of Hypothesis in Research PaperAndrew Molina100% (2)

- Introduction in Psychology Research PaperDocument7 pagesIntroduction in Psychology Research Papergazqaacnd100% (1)

- Psychology Research Paper Hypothesis ExamplesDocument8 pagesPsychology Research Paper Hypothesis Examplesfzpabew4100% (1)

- Where Is The Hypothesis Found in A Research PaperDocument8 pagesWhere Is The Hypothesis Found in A Research Papergzzjhsv9No ratings yet

- How To Include A Hypothesis in A Research PaperDocument5 pagesHow To Include A Hypothesis in A Research Paperafeascdcz100% (1)

- Sample Research Paper in Experimental PsychologyDocument6 pagesSample Research Paper in Experimental PsychologyzrpcnkrifNo ratings yet

- Define Hypothesis in Research PaperDocument4 pagesDefine Hypothesis in Research Paperkarennelsoncolumbia100% (2)

- The Research QuestionDocument9 pagesThe Research QuestionReyna Glorian HilarioNo ratings yet

- ANAS - First ExaminationDocument26 pagesANAS - First ExaminationRUEL ANASNo ratings yet

- What Is Hypothesis in Dissertation ProposalDocument6 pagesWhat Is Hypothesis in Dissertation ProposalCustomWritingPapersKnoxville100% (1)

- Journal Club Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesJournal Club Literature Reviewakjnbowgf100% (1)

- Lecture 2a-Research ProblemDocument31 pagesLecture 2a-Research ProblemRida Wahyuningrum Goeridno DarmantoNo ratings yet

- Basic Vs Applied ResearchDocument8 pagesBasic Vs Applied ResearchMasoom NaeemNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics About MedicineDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Topics About Medicineqmgqhjulg100% (1)

- UGML JAMA - I - How To Get StartedDocument3 pagesUGML JAMA - I - How To Get StartedAlicia WellmannNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Vs Secondary DataDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Vs Secondary Datac5t0jsyn100% (1)

- Health Science Literature Review ExampleDocument7 pagesHealth Science Literature Review Exampleafdtszfwb100% (1)

- How Do You Write A Hypothesis For A Research PaperDocument6 pagesHow Do You Write A Hypothesis For A Research Paperlucycastilloelpaso100% (2)

- Thesis Statement On Diet PillsDocument4 pagesThesis Statement On Diet PillsPaySomeoneToWriteAPaperCanada100% (2)

- Dissertation Research Question HypothesisDocument4 pagesDissertation Research Question HypothesisWriteMyPaperForMoneyTulsa100% (1)

- How To Include Hypothesis in Research PaperDocument5 pagesHow To Include Hypothesis in Research Papertiffanygrahamkansascity100% (2)

- How To Conduct Meta AnalysisDocument15 pagesHow To Conduct Meta AnalysisJuniza JubriNo ratings yet

- How To Find A Hypothesis in A Research PaperDocument8 pagesHow To Find A Hypothesis in A Research Papervstxevplg100% (1)

- Research ProcessDocument7 pagesResearch Processangelicadecipulo0828No ratings yet

- PR2 Study NotesDocument9 pagesPR2 Study NotesLayza Mea ArdienteNo ratings yet

- Ocd Thesis QuestionDocument8 pagesOcd Thesis QuestionBuyEssaysOnlineForCollegeSiouxFalls100% (1)

- Formulating The Research Problem Steps of The Scientific Process Literature ReviewDocument12 pagesFormulating The Research Problem Steps of The Scientific Process Literature ReviewIzzat RahmanNo ratings yet

- Sample Research Paper MedicineDocument6 pagesSample Research Paper Medicineclwdcbqlg100% (1)

- Hypothesis in Research Paper DefinitionDocument8 pagesHypothesis in Research Paper Definitiontrinajacksonjackson100% (1)

- Medical Research Paper ExamplesDocument4 pagesMedical Research Paper Examplesluwop1gagos3No ratings yet

- Research Paper On PsychologistDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Psychologistp0zikiwyfyb2100% (1)

- Developing Great Research QuestionsDocument5 pagesDeveloping Great Research QuestionsEduardo MirandaNo ratings yet

- Medical Research Paper ExampleDocument7 pagesMedical Research Paper Examplegvzwyd4n100% (1)

- RISSC201Document81 pagesRISSC201Vinancio ZungundeNo ratings yet

- Hypothesis and ThesisDocument5 pagesHypothesis and ThesisBuyAPaperOnlineUK100% (2)

- Good Medical Research Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesGood Medical Research Paper Topicsn1dihagavun2100% (1)

- Identifying Hypothesis in Research PaperDocument6 pagesIdentifying Hypothesis in Research PaperBuyCustomEssaysOnlineOmaha100% (3)

- Nursing Research Thesis TitlesDocument7 pagesNursing Research Thesis Titlesjuliepatenorman100% (2)

- How To Critically ReviewDocument2 pagesHow To Critically ReviewAndika SaputraNo ratings yet

- Example of Introduction in Psychology Research PaperDocument6 pagesExample of Introduction in Psychology Research Paperefjem40qNo ratings yet

- Experimental Psychology Research Paper SampleDocument7 pagesExperimental Psychology Research Paper Sampleeffbd7j4100% (1)

- 3is Q1 Module 2 - Removed - RemovedDocument6 pages3is Q1 Module 2 - Removed - RemovedDavid King AvilaNo ratings yet

- How Read Papers That Go Beyond Numbers (Qualitative Research)Document24 pagesHow Read Papers That Go Beyond Numbers (Qualitative Research)Muhammad Bilal SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Research Paper IntroductionDocument8 pagesHealthcare Research Paper Introductiontqpkpiukg100% (1)

- Redistribution and PBRDocument1 pageRedistribution and PBRdibpalNo ratings yet

- Mapping PEC 2021-Oct-20 Annex-D Courses Vs PLO Vs TaxonomyDocument2 pagesMapping PEC 2021-Oct-20 Annex-D Courses Vs PLO Vs TaxonomyEngr.Mohsin ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Invoice: PT - Sitc IndonesiaDocument1 pageInvoice: PT - Sitc IndonesiaMuhammad SyukurNo ratings yet

- 2021 HhhhhhhterqasdwqwDocument1 page2021 HhhhhhhterqasdwqwHassan KhanNo ratings yet

- Supra AccessoryDocument7 pagesSupra AccessoryaeroglideNo ratings yet

- Stamens PDFDocument10 pagesStamens PDFAmeya KannamwarNo ratings yet

- Itcc Comm. Center Bms Io PGDocument3 pagesItcc Comm. Center Bms Io PGuddinnadeemNo ratings yet

- Skript Version30 PDFDocument90 pagesSkript Version30 PDFNguyễn TúNo ratings yet

- 1884 Journey From Heraut To Khiva Moscow and ST Petersburgh Vol 2 by Abbott S PDFDocument342 pages1884 Journey From Heraut To Khiva Moscow and ST Petersburgh Vol 2 by Abbott S PDFBilal AfridiNo ratings yet

- The Migration Industry and Future Directions For Migration PolicyDocument4 pagesThe Migration Industry and Future Directions For Migration PolicyGabriella VillaçaNo ratings yet

- TGDocument180 pagesTGavikram1984No ratings yet

- Recruitment & Selection Reliance Jio Full Report - 100 Page MANU SHARMA MBA 3rd SEMDocument102 pagesRecruitment & Selection Reliance Jio Full Report - 100 Page MANU SHARMA MBA 3rd SEMImpression Graphics100% (4)

- Curriculum Ucv SedapalDocument2 pagesCurriculum Ucv SedapalSheyler Alvarado SanchezNo ratings yet

- Compal Confidential: QIWG7 DIS M/B Schematics DocumentDocument5 pagesCompal Confidential: QIWG7 DIS M/B Schematics DocumentКирилл ГулякевичNo ratings yet

- Activation of Bacterial Spores. A Review': I G RminaDocument7 pagesActivation of Bacterial Spores. A Review': I G RminaJunegreg CualNo ratings yet

- Operation & Maintenance Manual: Diesel Vehicle EngineDocument158 pagesOperation & Maintenance Manual: Diesel Vehicle Engineالمعز محمد عبد الرحمن100% (1)

- Magazines ListDocument11 pagesMagazines ListSheshadri Kattepur NagarajNo ratings yet

- Peek - POLYETHER ETHER KETONEDocument58 pagesPeek - POLYETHER ETHER KETONEBryan Jesher Dela Cruz100% (1)

- MATHEMATICS WEEK3 2nd GRADE 4Document11 pagesMATHEMATICS WEEK3 2nd GRADE 4Jonah A. RecioNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Trajectory Model For Differential Steering Using Numerical MethodDocument6 pagesEvaluation of Trajectory Model For Differential Steering Using Numerical MethodNaufal RachmatullahNo ratings yet

- Longest Common SubstringDocument33 pagesLongest Common SubstringHelton DuarteNo ratings yet

- 5db83ef1f71e482 PDFDocument192 pages5db83ef1f71e482 PDFRajesh RoyNo ratings yet

- Project MarketingDocument88 pagesProject MarketingAnkita DhimanNo ratings yet

- EScan Corporate 360 UGDocument601 pagesEScan Corporate 360 UG11F10 RUCHITA MAARANNo ratings yet

- Dictionary View Objects: Dict - Keys Dict - Values Dict - ItemsDocument6 pagesDictionary View Objects: Dict - Keys Dict - Values Dict - Itemssudhir RathodNo ratings yet

- Eb 12Document25 pagesEb 12SrewaBenshebilNo ratings yet