Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tau 08 02 141bv

Tau 08 02 141bv

Uploaded by

Nidhin MathewCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Ureteric ComplicationsDocument7 pagesUreteric ComplicationstnsourceNo ratings yet

- Use of Locking-Loop Pigtail Nephrostomy Catheters in Dogs and Cats 20 Cases (2004 2009)Document10 pagesUse of Locking-Loop Pigtail Nephrostomy Catheters in Dogs and Cats 20 Cases (2004 2009)Bernardo BertoldiNo ratings yet

- Stenting in Pediatric TransplantationDocument27 pagesStenting in Pediatric TransplantationChris FrenchNo ratings yet

- Urologic Complications in Renal Transplants: Hannah R. Choate, Laura A. Mihalko, Bevan T. ChoateDocument7 pagesUrologic Complications in Renal Transplants: Hannah R. Choate, Laura A. Mihalko, Bevan T. ChoateNidhin MathewNo ratings yet

- Plication of DJ Stents WceDocument1 pagePlication of DJ Stents Wcejinsi georgeNo ratings yet

- Revisiting The Predictive Factors For Intra-Op-erative Complications of Rigid UreterosDocument8 pagesRevisiting The Predictive Factors For Intra-Op-erative Complications of Rigid UreterosTatik HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Marion 2020Document7 pagesMarion 2020hezzaNo ratings yet

- Icu 60 21Document8 pagesIcu 60 21manueljna2318No ratings yet

- Urinary Calculi in Aviation Pilots: What Is The Best Therapeutic Approach?Document3 pagesUrinary Calculi in Aviation Pilots: What Is The Best Therapeutic Approach?NaifahLuthfiyahPutriNo ratings yet

- A Novel Technique For Treatment of Distal Ureteral Calculi: Early ResultsDocument4 pagesA Novel Technique For Treatment of Distal Ureteral Calculi: Early ResultsTheQueensafa90No ratings yet

- Complications of Biliary T-Tubes After Choledochotomy: Original ArticleDocument4 pagesComplications of Biliary T-Tubes After Choledochotomy: Original ArticleBikash SahNo ratings yet

- NeurogenicbladdermanagementwithcompleteurethraldistructionDocument11 pagesNeurogenicbladdermanagementwithcompleteurethraldistructionPutri Rizky AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Transurethral Incision of Ureterocele: Does The Time of Presentation Affect The Need For Further Surgical Interventions?Document6 pagesTransurethral Incision of Ureterocele: Does The Time of Presentation Affect The Need For Further Surgical Interventions?ErikNo ratings yet

- Organ Transplantation Historial Perspective and Current PracticeDocument14 pagesOrgan Transplantation Historial Perspective and Current Practicehkdawnwong100% (1)

- Reconstruction of Late-Onset Transplant Ureteral Stricture DiseaseDocument6 pagesReconstruction of Late-Onset Transplant Ureteral Stricture DiseaseAnanda KumarNo ratings yet

- Reconstruction of Late-Onset Transplant Ureteral Stricture DiseaseDocument7 pagesReconstruction of Late-Onset Transplant Ureteral Stricture DiseasetnsourceNo ratings yet

- Yu 2013Document4 pagesYu 2013raissametasariNo ratings yet

- Chung 2004Document4 pagesChung 2004raghad.bassalNo ratings yet

- Finally Ileal Ureter Corrected (1) (1) IbjuDocument11 pagesFinally Ileal Ureter Corrected (1) (1) IbjuSheshang KamathNo ratings yet

- Tugas Urologi Long Term PostDocument11 pagesTugas Urologi Long Term PostI Gusti Ngurah Nanda PramanaNo ratings yet

- Article 39794Document4 pagesArticle 39794d.amouzou1965No ratings yet

- Multi-Tract Percutaneous NephrolithotomyDocument5 pagesMulti-Tract Percutaneous Nephrolithotomythanhtung1120002022No ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument9 pagesContent ServerenimaNo ratings yet

- SiddiqueDocument5 pagesSiddiqueAman ShabaNo ratings yet

- Surgical Techniques of Kidney Transplantation: Christopher J.E. Watson, Peter J. Friend and Lorna P. MarsonDocument16 pagesSurgical Techniques of Kidney Transplantation: Christopher J.E. Watson, Peter J. Friend and Lorna P. Marsonw5rh7kqg6pNo ratings yet

- Nephro-Urology Monthly Nephro-Urology Monthly Nephro-Urology MonthlyDocument3 pagesNephro-Urology Monthly Nephro-Urology Monthly Nephro-Urology MonthlyTheQueensafa90No ratings yet

- bien chung nieu mổ lấy thaiDocument4 pagesbien chung nieu mổ lấy thaiMint For MomsNo ratings yet

- Complications of Percutaneous Nephrostomy Tube Placement To Treat NephrolithiasisDocument4 pagesComplications of Percutaneous Nephrostomy Tube Placement To Treat NephrolithiasisPande Made FitawijamariNo ratings yet

- Management of Feline Ureteral Obstructions: An Interventionalist's ApproachDocument6 pagesManagement of Feline Ureteral Obstructions: An Interventionalist's ApproachvetgaNo ratings yet

- V34n4a05 PDFDocument10 pagesV34n4a05 PDFvictorcborgesNo ratings yet

- Ju 0000000000000840 07Document2 pagesJu 0000000000000840 07Eksa RachmadiansyahNo ratings yet

- Ureteral Stent For Ureteral Stricture: James F. Borin and Elspeth M. McdougallDocument13 pagesUreteral Stent For Ureteral Stricture: James F. Borin and Elspeth M. McdougallOoNo ratings yet

- Clinical Study: Parameters That May Be Used For Predicting Failure During Endoscopic Retrograde CholangiopancreatographyDocument6 pagesClinical Study: Parameters That May Be Used For Predicting Failure During Endoscopic Retrograde CholangiopancreatographyAkansh DattaNo ratings yet

- Wrap Plication of Megaureter Around Normal-Sized Ureter For Complete Duplex System ReimplantationsDocument5 pagesWrap Plication of Megaureter Around Normal-Sized Ureter For Complete Duplex System ReimplantationsDirga Rasyidin LNo ratings yet

- The Experience of A Tertiary Referral Center With Laparoscopic Pyelolithotomy For Large Renal Stones During 18 YearsDocument8 pagesThe Experience of A Tertiary Referral Center With Laparoscopic Pyelolithotomy For Large Renal Stones During 18 YearsDaniel StrubNo ratings yet

- Advances in Urinary Tract EndosDocument23 pagesAdvances in Urinary Tract EndosJosé Moreira Lima NetoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2667008923000253 MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S2667008923000253 Mainal malikNo ratings yet

- Adam 2017Document4 pagesAdam 2017Bandac AlexandraNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Open and Laproscopic Live Donor NephrectomyDocument7 pagesComparison of Open and Laproscopic Live Donor NephrectomyEhab Omar El HalawanyNo ratings yet

- Horshoe KidneDocument5 pagesHorshoe KidneteguhdjufriNo ratings yet

- SC 2015242Document7 pagesSC 2015242resi ciruNo ratings yet

- Endourology and Stone Diseases: Original ArticlesDocument5 pagesEndourology and Stone Diseases: Original ArticlesTatik HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Transplantation of Organs Feasible or Practical?: Wizen IsDocument32 pagesTransplantation of Organs Feasible or Practical?: Wizen IswunderfullifeNo ratings yet

- Corresponding Member of National Academy of Science Of, Academician of RussianDocument4 pagesCorresponding Member of National Academy of Science Of, Academician of RussianRavilNo ratings yet

- Open Access Journal of Urology & Nephrology: Interventional Radiology Techniques in The Genitourinary TractDocument5 pagesOpen Access Journal of Urology & Nephrology: Interventional Radiology Techniques in The Genitourinary Tractalfredo elizondoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0039606020306759 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0039606020306759 MainKar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Tecnica de Clips Nefrectomia ParcialDocument8 pagesTecnica de Clips Nefrectomia ParcialAlfredo BalcázarNo ratings yet

- Pemeriksaan IVPDocument41 pagesPemeriksaan IVPChandra Noor SatriyoNo ratings yet

- 104854-Article Text-283461-1-10-20140701Document6 pages104854-Article Text-283461-1-10-20140701Joan Marie S. FlorNo ratings yet

- Krav Chick 2005Document4 pagesKrav Chick 2005victorcborgesNo ratings yet

- Retrospective Study To Determine The Short-Term Outcomes of A Modified Pneumovesical Glenn-Anderson Procedure For Treating Primary Obstructing Megaureter. 2015Document6 pagesRetrospective Study To Determine The Short-Term Outcomes of A Modified Pneumovesical Glenn-Anderson Procedure For Treating Primary Obstructing Megaureter. 2015Paz MoncayoNo ratings yet

- Pancreatic ®stula After Pancreatic Head ResectionDocument7 pagesPancreatic ®stula After Pancreatic Head ResectionNicolas RuizNo ratings yet

- PublicationDocument7 pagesPublicationmagnusspecialityreportsNo ratings yet

- Yan 2015Document4 pagesYan 2015ELIECERNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Retrograde Intrarenal Surgery and Standard Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy For Management of Stones at Ureteropelvic Junction With High-Grade HydronephrosisDocument5 pagesComparison of Retrograde Intrarenal Surgery and Standard Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy For Management of Stones at Ureteropelvic Junction With High-Grade Hydronephrosisyicini2524No ratings yet

- Complex Case of Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction 2024 International JournaDocument3 pagesComplex Case of Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction 2024 International JournaRonald QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Review StrikturDocument13 pagesReview StrikturFryda 'buona' YantiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2405456920302133 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S2405456920302133 MainMeta ParamitaNo ratings yet

- Whole Ovary TransplantationDocument7 pagesWhole Ovary Transplantationari naNo ratings yet

- Critical Care for Potential Liver Transplant CandidatesFrom EverandCritical Care for Potential Liver Transplant CandidatesDmitri BezinoverNo ratings yet

- List of Companies With Contact Details For Global VillageDocument5 pagesList of Companies With Contact Details For Global VillagemadhutkNo ratings yet

- + Eldlife I: 170,000.00 Total Amount Total Amount Before Tax 170,000.00 170,000.00Document1 page+ Eldlife I: 170,000.00 Total Amount Total Amount Before Tax 170,000.00 170,000.00Kaifi asgarNo ratings yet

- Laura Su ResumeDocument1 pageLaura Su Resumeapi-280311314No ratings yet

- Chapter 15 - Designing and Managing Integrating Marketing CommunicationsDocument28 pagesChapter 15 - Designing and Managing Integrating Marketing CommunicationsArmanNo ratings yet

- DECAA - Letter To DC Gov't Officials Re DPW Causing Explosion in Rat PopulationDocument22 pagesDECAA - Letter To DC Gov't Officials Re DPW Causing Explosion in Rat PopulationABC7NewsNo ratings yet

- Ngá Nghä©a Unit 4Document5 pagesNgá Nghä©a Unit 4Nguyen The TranNo ratings yet

- Onkyo tx-nr737 SM Parts Rev6Document110 pagesOnkyo tx-nr737 SM Parts Rev6MiroslavNo ratings yet

- Equity ApplicationDocument3 pagesEquity ApplicationanniesachdevNo ratings yet

- Legendary RakshashaDocument24 pagesLegendary RakshashajavandarNo ratings yet

- Loans and MortgagesDocument26 pagesLoans and Mortgagesparkerroach21No ratings yet

- Amazon Invoice - Laptop Stand PDFDocument1 pageAmazon Invoice - Laptop Stand PDFAl-Harbi Pvt LtdNo ratings yet

- Pattern Recognition: Zhiming Liu, Chengjun LiuDocument9 pagesPattern Recognition: Zhiming Liu, Chengjun LiuSabha NayaghamNo ratings yet

- Zumba DLPDocument8 pagesZumba DLPJohnne Erika LarosaNo ratings yet

- NDT Basics GuideDocument29 pagesNDT Basics Guideravindra_jivaniNo ratings yet

- Part 2 Twentieth Century Naval Dockyards Devonport and Portsmouth Characterisation ReportDocument52 pagesPart 2 Twentieth Century Naval Dockyards Devonport and Portsmouth Characterisation ReportToby ChessonNo ratings yet

- Wine Enthusiast - May 2014Document124 pagesWine Enthusiast - May 2014Johanna Shin100% (1)

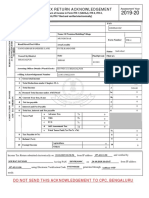

- Acknowledgement ItrDocument1 pageAcknowledgement ItrSourav KumarNo ratings yet

- Of The Abdominal Wall, Abdominal Organs, Vasculature, Spinal Nerves and DermatomesDocument11 pagesOf The Abdominal Wall, Abdominal Organs, Vasculature, Spinal Nerves and DermatomesentistdeNo ratings yet

- Dodla Dairy Hyderabad Field Visit 1Document23 pagesDodla Dairy Hyderabad Field Visit 1studartzofficialNo ratings yet

- Proprietary & Confidential: This Is A Static Sensitive Device. Handle & Store Appropriately To Prevent Esd DamageDocument2 pagesProprietary & Confidential: This Is A Static Sensitive Device. Handle & Store Appropriately To Prevent Esd DamagePawan PalNo ratings yet

- EC506 Wireless Gateway User Manual ENGDocument48 pagesEC506 Wireless Gateway User Manual ENGcy5170No ratings yet

- Mixers FinalDocument44 pagesMixers FinalDharmender KumarNo ratings yet

- 305-1-Seepage Analysis Through Zoned Anisotropic Soil by Computer, Geoffrey TomlinDocument11 pages305-1-Seepage Analysis Through Zoned Anisotropic Soil by Computer, Geoffrey Tomlinد.م. محمد الطاهرNo ratings yet

- Salt Market StructureDocument8 pagesSalt Market StructureASBMailNo ratings yet

- Apurba MazumdarDocument2 pagesApurba MazumdarDRIVECURENo ratings yet

- British Deputy High Commission in KarachiDocument1 pageBritish Deputy High Commission in KarachiRaza WazirNo ratings yet

- Prolin Termassist Operating Guide: Pax Computer Technology Shenzhen Co.,LtdDocument29 pagesProlin Termassist Operating Guide: Pax Computer Technology Shenzhen Co.,Ltdhenry diazNo ratings yet

- List of Goosebumps BooksDocument10 pagesList of Goosebumps Booksapi-398384077No ratings yet

- 510 - Sps Vega vs. SSS, 20 Sept 2010Document2 pages510 - Sps Vega vs. SSS, 20 Sept 2010anaNo ratings yet

- Seismic Sequence Stratigraphy - PresentationDocument25 pagesSeismic Sequence Stratigraphy - PresentationYatindra Dutt100% (2)

Tau 08 02 141bv

Tau 08 02 141bv

Uploaded by

Nidhin MathewOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tau 08 02 141bv

Tau 08 02 141bv

Uploaded by

Nidhin MathewCopyright:

Available Formats

Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UK

BJUBJU International1464-4096BJU International

90

3004

UROLOGICAL COMPLICATIONS OF RENAL TRANSPLANTATION

E.H. STREETER

et al.

10.1046/j.1464-4096.2002.03004.x

Original Article627634BEES SGML

BJU International (2002), 90, 627–634 doi:10.1046/j.1464-4096.2002.03004.x

The urological complications of renal transplantation: a series

of 1535 patients

E.H. STREETER*, D.M. LITTLE†, D.W. CRANSTON*† and P.J. MOR RIS†

*Department of Urology, and †Oxford Transplant Centre, Churchill Hospital, Oxford, UK

Objective To determine the incidence of urological com- were three deaths associated directly or indirectly with

plications of renal transplantation at one institution, urological complications. There was no association

and relate this to donor and recipient factors. with recipient age, cadaveric vs living-donor trans-

Patients and methods A consecutive series of 1535 renal plants, or cold ischaemic times before organ reimplan-

transplants were audited, and a database of donor and tation, although the donor age was slightly higher in

recipient characteristics created for risk-factor analy- cases of urinary leak. There was no association with

sis. An unstented Leadbetter-Politano anastomosis was kidneys imported via the UK national organ-sharing

the preferred method of ureteric reimplantation. scheme vs the use of local kidneys. The management of

Results There were 45 urinary leaks, 54 primary ureteric these complications is discussed.

obstructions, nine cases of ureteric calculi, three blad- Conclusion The incidence of urological complications in

der stones and 19 cases of bladder outlet obstruction at this series has remained essentially unchanged for

some time after transplantation. The overall incidence 20 years. The causes of these complications and tech-

of urological complications was 9.2%, with that for uri- niques for their prevention are discussed.

nary leak or primary ureteric obstruction being 6.5%. Keywords renal transplantation, complications, aeti-

One graft was lost because of complications, and there ology

unrelated donor transplants). All patients were followed

Introduction

up at the centre for at least 1 year after surgery. Data on

Major advances have been made over the last two decades the incidence and nature of urological complications were

in renal transplantation. While formal research pro- accumulated by retrospective case-note analysis.

grammes concentrate on the associated immunology Several operating surgeons were involved, of consultant

technical issues concerning the procedure have almost or specialist registrar grade. In all but three procedures

been obscured. Despite this, early graft failure is often for a Leadbetter-Politano ureteroneocystostomy was used,

technical reasons, and urological complications remain a involving the passage of the ureter through a submucosal

major source of morbidity and occasional mortality. The tunnel fashioned via a separate anterior cystostomy. Two

incidence of these complications is discussed, and causes cases required primary uretero-ureterostomy for a short

in their development evaluated. Recent advances in surgi- donor ureter. In one procedure the ureter was implanted

cal technique are noted with speculation about their into a bladder caecoplasty. Ureteric stents were used

possible effect for the future. rarely. A Foley catheter was used to drain the bladders of

all patients for at least 5 days after surgery. Daily serum

biochemistry was combined with careful clinical observa-

Patients and methods

tion to monitor graft function. In recent years it has

All cases of renal transplantation from the inception of our become standard practice to image all grafts by ultra-

unit in January 1975 to May 1998 were included in the sonography soon after surgery, usually in the first or

study; the series comprised 1535 consecutive renal trans- second day, to detect early signs of vascular or urological

plants, in 1292 patients (mean age 43.0 years at surgery, complications. This succeeds the former practice of imag-

range 11–75; male : female ratio of procedures 1.52 : 1, ing only in those with suspected graft dysfunction. All

with 1386 cadaveric transplants and 149 living-related or patients since 1982 have been treated with cyclosporin-

based immunosuppressive regimens. The 273 cases before

this were treated with a combination of azathioprine and

prednisolone, with high-dose prednisolone giving way to

Accepted for publication 26 July 2002 the current low-dose schedule in 1978.

© 2002 BJU International 627

628 E.H. STREETER et al.

For purposes of chronological comparison, data are sis. A summary of the position and timing of urinary leaks,

subdivided into 1975–86 (transplants 1–600), 1986–91 with the subsequent management, is shown in Table 1.

(transplants 601–1000), and 1991–98 (transplants Minor leaks occurred early in four cases and were

1001–1535). Data relating to the early part of the series treated with re-catheterization or with observation alone.

were published previously [1,2]. Three cases were managed initially with nephrostomy

insertion, although two of these proceeded to ureteric

reimplantation.

Results

Thirty-seven cases required surgery; two with direct

perforation of the ureter at procurement or implantation

Urinary leak

were sutured over. Three cases of vesico-ureteric leakage

There were 45 cases of urinary leak, with a further three in the absence of necrosis were treated with open stent

recurrent cases after a first operative repair. The median insertion. The degree of ureteric vascular compromise and

(range) time to onset was 29 (0–275) days, with all but necrosis dictated the use of reimplantation (eight cases),

two cases before 120 days. No grafts were lost, although uretero-ureterostomy (three), uretero-pyelostomy (15) or

one death could be directly attributed to subsequent sep- Boari flap (two). Two cases of leakage through the anterior

Table 1 Urinary leakage and obstruction; incidence and management

Location (n) Median (range) onset, days Treatment (n)

Leakage

No site identified (1) 14 Death from cardiac arrest (1)

Upper ureter/collecting system (5) 24 (0–49) Conservative (1)

Retrograde stent (1)

Open closure of defect in renal pelvis (1)

Open closure of renal pelvis and stent (1)

Uretero-ureterostomy (1)

Lower ureter (14) 21 (0–266) Nephrostomy (1)

Open drainage (1)

Open stent insertion (3)

Reimplantation (3)

Native ureteropyelostomy (2)

Uretero-ureterostomy (3)

Boari flap (1)

Bladder (6) 47 (0–357) Prolonged catheter drainage (3)

Percutaneous drainage (1)

Repair of vesical defect (2)

Ureteric necrosis (19) 35 (7–70) Reimplantation (5)

Native ureteropyelostomy (13)

Boari flap (1)

Obstruction

Upper/PUJ (10) 350 (35–1610) Antegrade stent (4)

Ureteric dilatation (1)

Pyeloplasty (1)

Division of obstructing vessel (1)

Native ureteropyelostomy (3)

Middle (10) 56 (1–1120) Antegrade stent (3)

Retrograde stent (1)

Open exploration (1) and stent (1)

Native ureteropyelostomy (2)

Uretero-ureterostomy (2)

Lower/VUJ (33) 110 (1–2800) Nephrostomy (2)

Antegrade stent (6)

Balloon dilatation (2)

Endoscopic excision of suture (1)

Native ureteropyelostomy (2)

Reimplantation (20)

© 2002 BJU International 90, 627–634

UROLOGICAL COMPLICATIONS OF RENAL TRANSPLANTATION 62 9

Table 2 The incidence of major complications with time

Transplant renal calculi

Ureteric obstruction, % There were six cases of obstructive ureteric calculi, with

Transplant Urinary Ischaemic Other three further cases not associated with obstruction.

number leak, % Total stricture causes The median (range) time to presentation was 150 (56–

1280) days. In the three unobstructive cases there was no

1–600 2.80 4.33 1.83 2.50

intervention. Of those with obstruction, one was treated

601–1000 2.00 2.50 2.25 0.25

with nephrostomy insertion followed by percutaneous

1001–1535 3.73 3.36 2.24 1.12

shock wave lithotripsy, three underwent successful percu-

Total 2.93 3.52 2.08 1.43 taneous nephrolithotomy and one proceeded to open

nephrolithotomy having failed the percutaneous

approach. In the final case both endoscopic and percuta-

neous attempts failed to remove the calculus, with graft

cystotomy required re-suturing of the bladder. Two cases function being lost, resulting in a nephrectomy.

required repeat reconstruction, with one leak persisting,

being treated with nephrostomy and antegrade stenting.

An additional operative failure was treated with ante- BOO

grade stenting. Table 2 shows the relative incidence of

urinary leakage over the study period. Seventeen patients developed significant BOO during the

course of the study, about half presenting within the first

month of transplantation. The causes were bladder neck

Primary ureteric obstruction stenosis (five), urethral strictures (four), BPH (five) and

Ureteric obstruction with no external compression undetermined (three). Patients were treated with bladder

occurred in 46 patients; there were two groups, i.e. those neck incision (five), optical urethrotomy (two) urethral

with an ischaemic origin, becoming clinically evident dilatation (two), TURP (five) or observation (three). There

usually at 1–18 months (32; median 6 months, range was one death after TURP caused by suprapubic catheter-

0.5–47), and those where anatomical or technical factors ization, urinary extravasation and sepsis.

were likely to have been more significant, evident in the

early recovery period (14; median 3 days, range 0–11).

There was no graft loss but there were two deaths, one Haematuria causing obstruction

caused by nephrostomy-related haemorrhage and the Six cases were recorded; of these, four occurred within

second with persistent stricturing, ureteric fistulation and 10 days of transplantation, causing hydronephrosis in two

sepsis. There were seven further cases of obstruction catheterized patients (days 2 and 3) and clot retention in

by lymphocoele (six) or obstructing blood vessels (one) in two patients (days 6 and 8). One patient with hydroneph-

the early part of the series. Table 2 shows the relative rosis required cystoscopic irrigation, whilst the others

incidence of ureteric obstruction over the study period. were treated conservatively.

The site and timing of obstruction again influenced There were two cases each of ureteric obstruction

management (Table 1). Antegrade stenting was used caused by haemorrhage after percutaneous needle biopsy

primarily in 19 cases, although five of these required sub- at 12 and 27 days, the latter associated with clot reten-

sequent operative procedures. Two distal strictures were tion. Both were treated with nephrostomy.

successfully percutaneously dilated, but an attempt to

remedy a pelvi-ureteric obstruction in the same way was

unsuccessful, requiring surgery. One case of a very limited

Neoplasia

stricture at the ureteric orifice was successfully managed

endoscopically via local excision. Two patients developed TCC of the bladder, both several

An open operation was required in 33 cases. The ureter years after transplantation. One had invasive disease, rap-

was unkinked in two cases and an overlying blood vessel idly metastasising and leading to death. The other had

divided in one. Proximal obstruction was treated by native superficial disease managed endoscopically. There was one

ureteropyelostomy (five) or pyeloplasty (one). Distal case of nephrogenic adenoma at 4.5 years, excised endo-

obstruction favoured ureteric reimplantation in the 20 scopically, recurring 2 years later and requiring two fur-

cases with a short segment stenosis, although one was ther cystoscopic resections. One patient who had had

later revised to a uretero-ureterostomy. Two further bilateral nephrectomies 3 and 4 years before transplanta-

uretero-ureterostomies and one uretero-pyelostomy were tion for metachronous adenocarcinomas had widespread

performed for longer or mid-ureteric stenoses. metastatic recurrence at 6 months and died.

© 2002 BJU International 90, 627–634

630 E.H. STREETER et al.

for the origin of the kidney, or cadaveric vs living donors.

Miscellaneous complications

The donors were slightly older in cases with urinary leaks

Bladder calculi were found on three occasions, at 8 than in the overall population. There was a paradoxically

months to 4 years after surgery; in all three cases the cal- shorter cold ischaemic time for ischaemic strictures.

culi were removed cystoscopically. One further patient

underwent cystoscopy for an ultrasonographically diag-

Discussion

nosed bladder mass, which was found to be a protruding

suture at the ureteric orifice, and which was excised Urological complications remain a major source of mor-

endoscopically. bidity and occasional mortality in renal transplantation,

despite a reduction in their incidence of at least half over

the last 30 years. Table 5 [3–17] shows a comparison of

Association of complications with donor factors

the present with contemporary series including > 400

The characteristics of the renal donors from the last transplants. Similarly, the graft loss and related mortality

8 years were analysed to ascertain whether causal factors has decreased, from 22% associated mortality and 54%

could be identified in the development of urological com- graft loss in 1981 [3] to 3.3% and < 1%, respectively,

plications. In particular, the origin of the kidney, i.e. reported here. The cause of these complications is of

locally retrieved vs imported via the UK organ-matching course multifactorial, and comparison of internationally

scheme, the donor’s age and the cold ischaemic time were published series shows wide variation among centres with

recorded (Table 3). There were no significant differences different practices. We consider possible causal factors

Table 3 Complications compared with donor factors

Variable Total (535) Leak (20), % Ischaemic stricture (12), %

Method of retrieval

Imported 149 4.7 3.4

Local 386 3.4 1.8

Donor

Cadaveric 55 5.4 1.8

Living-related 480 3.5 2.3

Mean (SD):

donor age, years 41.25 (14.7) 45.8 (11.0)* 40.3 (14.5)

cold ischaemic time, min 1517 (488) 1650 (598) 1064 (286)†

*P < 0.05; †P < 0.001.

Table 4 Comparative large series of renal transplants (1981–2001)

Ref. Year Number of transplants Vesico-ureteric anastomosis Ureteric stents Urinary leaks, % Ureteric obstruction, %

[3] 1981 1000 L-P No 5.6 7.5

[4] 1983 505 L-P No 2.2 1.0

[5] 1984 718 L-P No 8.9 3.3

[6] 1988 808 Extravesical No 1.4 0.9

[7] 1992 505 Transvesical nipple No 3.0 7.0

[8] 1992 1000 Extravesical No 0.9 0.3

[9] 1994 1200 Extra/transvesical N/A 4.0 2.5

[10] 1994 1298 Extravesical No N/A 3.1

[11] 1994 1016 L-P No 6.2 12.4

[12] 1996 1157 Paquin/extravesical No 1.5 1.3

[13] 1997 534 Extravesical No 5.6 6.3

[14] 1997 2084 L-P No 1.0 0.5

[15] 1998 600 Extravesical Mixed 2.5 1.7

[16] 2000 400 Extravesical Yes 0 0

[17] 2001 1200 Extravesical No 3.1 1.9

Present 2002 1535 L-P No 2.93 3.52

N/A, data not available; L-P, Leadbetter-Politano.

© 2002 BJU International 90, 627–634

UROLOGICAL COMPLICATIONS OF RENAL TRANSPLANTATION 631

and how changes in practice may reduce the rate of com- 1986–1998, although the present data showed no asso-

plications further. ciation between recipient age and complication rate.

An initial dramatic reduction in urological complica- There was no association with primary disease and

tions at our unit (16% in the first 207 cases vs 5% in the particularly no increased incidence of complications in

next 400) was attributed to the change from high- to diabetic patients.

low-dose steroid-based immunosuppressive regimens, and

the rate has changed little since then. As will be discussed,

Surgical

this may in fact mask an underlying trend towards safer

surgery. Technical considerations are of the utmost importance in

the incidence of urological complications. Disruption of

the ureteric normal blood supply at retrieval dictates that

Causal factors in urological complications

the remaining arterial and venous supply from the renal

Most urological complications are a result of technical vessels and lower polar branches must be preserved by

errors at retrieval or reimplantation, or failure of tissue minimal peri-ureteric dissection, especially in the so-

healing, influenced by ischaemia, inflammation, infec- called ‘golden triangle’ between the ureter, kidney and

tion, immunosuppression and antiproliferative agents, renal artery. Even so, the distal ureter is prone to

and the nutritional state of the recipient. Four main ischaemia. In living-related kidney donation, less aggres-

categories of factors are considered, i.e. donor, recipient, sive preservation of the blood supply may be possible. In

technical and medical. our unit 10% of transplants in this series were from living

donors, with 12.5% of potentially ischaemic complica-

tions involved this subgroup. Thus no link is confirmed.

Donor

This is in agreement with most large series of living-donor

The donor’s age and pre-existing comorbidity will influ- transplants, which report little effect on the incidence of

ence the potential function of the transplanted organs, urological complications [5,12].

and their ability to withstand the insult of ischaemia and Iatrogenic injury, the cause of two leaks in the present

reperfusion. Once a decision is made to offer organs for series, must be avoided during bench dissection. Minimiz-

transplantation, every effort must be made to preserve the ing warm ischaemic time is crucial. Dissection is carried

donor in an optimal state, with periods of hypotension, out on ice and the organ may be contained in an ice-filled

inotrope support or prolonged stay in the intensive treat- receptacle, e.g. a rubber glove, during the vascular anas-

ment unit all affecting the quality of the organs in the tomosis. This has been shown to maintain the core tem-

short- and possibly long-term. Retrieval surgery should perature of the kidney at < 10°C for protracted periods

thus proceed at the earliest appropriate opportunity. [20]. There was no association between cold ischaemic

The increasing pressure on transplant waiting lists will time or origin of the kidney (local vs from the national

undoubtedly lead to more marginal donors being consid- organ-sharing scheme) and the incidence of urological

ered. The eventual effect of this tendency has yet to be complication.

evaluated, although in the last 8 years, the donor age for Ureteric reimplantation is where most interest has been

the present cases of urinary leak is slightly higher than for focused in recent years, particularly for the type of vesico-

the whole population over the same period. Long-term ureteric anastomosis constructed and the use of prophy-

graft survival is strongly correlated with donor-recipient lactic ureteric stents. In nearly all cases in the present

HLA mismatch, e.g. in the data from the UNOS and series a Leadbetter-Politano submucosal tunnelled anas-

UKTSSA registries [18,19]. This is of course a result of a tomosis was used [21]. This has been suggested to lower

combination of acute and chronic rejection. Loughlin the incidence of ureteric reflux over conventional extra-

et al. [5] reported no correlation of urological complica- vesical procedures [21,22], particularly important if the

tions with HLA mismatch, but this series had an overall patient has recurrent UTIs. In the present series one case

rate higher (13.2%) than that of most recently published of symptomatic reflux was identified in a patient with

series. recurrent pyelonephritis, successfully treated with ure-

teric reimplantation. More recent modifications of the

extravesical approach, including a short muscular tunnel

Recipient

over the ureteric tip in an attempt to prevent reflux, have

The increasing availability of dialysis services and lead to the technique being shown in several series to pro-

improved medical management of chronic renal failure duce fewer ureteric obstructions [6,23–25]. Ischaemic

have lead to an increase in the age of recipients of renal strictures are probably reduced through the shorter

transplants in the present series, from a mean of length of ureter required, and extrinsic compression from

37.8 years in 1975–1986 to 46.7 years at operation in the submucosal tunnel is also avoided. The operating time

© 2002 BJU International 90, 627–634

632 E.H. STREETER et al.

is reduced and the need for an additional anterior cystot-

Medical management

omy, the source of six leaks in our series, is obviated. The

effect of this technique has been shown by two retrospec- Of major importance was the change to low-dose steroid

tive series comparing major complications before and after immunosuppression in the late 1970s, with the major

its adoption. Butterworth et al. [25] claimed a reduction complication rate decreasing from 16% in the first 207

from 12% to 2% in a series of 248 patients, and Thrasher cases to ≈ 7% since. Ongoing trials of immunosuppressive

et al. [24] from 9.4 to 3.7% over 320 cases. regimens are unlikely to produce this magnitude of effect.

Two retrospective series showed remarkable reductions As has been stated, no clear link has been shown between

in major urological complications by using prophylactic rejection and urological complications, and as long as the

ureteric stents (15% to 2.6%, and 13.6% to none, respec- complication is corrected, long-term function is preserved

tively) [26,27]. Several prospective randomized series Erectile dysfunction after transplantation is markedly

have since confirmed this [16,28–30]. The stents are less than in those with renal failure or dialysis, being

prone to breakage, especially if left for > 3 months, and halved from 47% to 22% between dialysis-dependent and

may also migrate. The material used in the manufacture successfully transplanted patients [33]. Ongoing problems

of the stent has been suggested to affect its lithogenicity are experienced often by patients on antihypertensive

[31], although the incidence of stent-associated calcifica- medication. The risk of erectile dysfunction after bilateral

tion may be reduced by their early removal at 2 weeks internal iliac transplant anastomoses has been estimated

after surgery [16]. The current policy in our unit (adopted at 65%, vs 10% for unilateral cases [34].

after the conclusion of this series) is to use stents in cases

where there is concern about ureteric ischaemia, com-

Urological malignancy

bined with an extravesical anastomosis; it is too early to

assess the effects of this recent change of practice. Urological malignancy, like all other forms of malignancy

In the last 535 patients the incidence of significant hae- in the transplant population, is in part a direct result of

maturia after transplantation, causing bladder outlet or immunosuppression. An incidence of 1.4% (relative risk

ureteric obstruction, is low, with four cases within the first 7–11 times) was reported by Schmidt et al. [35]. However,

10 days after surgery. Whether the source of the bleeding all but 13 of the 868 patients reported in that series

is from the cystotomy or elsewhere is unknown. All were received antilymphocyte or antithymocyte globulin at

managed conservatively with re-catheterization, one re- induction. This practice, thought to be of great impor-

quiring cystoscopic irrigation. Two cases of obstructing tance to the risk of developing malignancy, is very unusual

haematuria secondary to allograft biopsy required neph- in the present series. However, more recent data from the

rostomy insertion. All patients in our centre with cadav- Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant regis-

eric grafts undergo biopsies at 7 and 28 days, according to try confirmed a seven-fold increased risk of bladder and

protocol or at any sign of deterioration of renal function. renal cancer in transplant recipients [36].

Living-related transplant recipients do not undergo rou- There were two cases of TCC of the bladder in the

tine biopsy because of the lower incidence of acute rejec- present series; invasive bladder cancer must be treated

tion in this group. These two cases thus represent a very aggressively because of its propensity for rapid progres-

low overall rate of urological complication, but of course sion. For patients with superficial disease, management

do not include other cases of significant haemorrhage. involving transurethral tumour resection and close

The incidence of lower urinary tract obstruction requir- cystoscopic observation should be tailored according to

ing a procedure within 6 months of transplantation was standard risk factors such as the presence of high-grade

2%. Whether to evaluate the lower urinary tract of asymp- disease, multifocal invasion of the lamina propria or car-

tomatic patients before surgery, with the aim of reducing cinoma in situ. Conventional adjuvant therapy using BCG

symptomatic outlet problems afterward, is an area of con- is contraindicated in the immunosuppressed patient, thus

tention [32]. Again, whether to intervene beforehand, early aggressive surgical treatment should be considered.

with the risk of stricturing of the urethra after instrumen- A particular risk factor for RCC is acquired renal cystic

tation, without the regular passage of urine, is controver- disease, which occurs in up to half of patients on long-

sial [32]. Intermittent self-catheterization and instillation term dialysis, often causing pain through cystic haemor-

of antibiotic solution with normal voiding is suggested to rhage, haematuria and infection. It may be associated

circumvent this problem. Many investigators suggest with a 30-fold increased risk of RCC (especially of the pap-

waiting until after transplantation, with an early planned illary variant) in the pretransplant population. The cystic

urological procedure. In the case of a noncompliant blad- change often regresses after successful transplantation

der requiring reconstruction or augmentation, enterocys- but the relative risk of RCC in the transplant population is

toplasty is recommended before transplantation and the not thought to be high. There were no cases of RCC in the

risk of immunosuppression [32]. present series. Two prospective series of ultrasonography

© 2002 BJU International 90, 627–634

UROLOGICAL COMPLICATIONS OF RENAL TRANSPLANTATION 63 3

screening before transplantation reported incidences of 7 Kashi SH, Lodge JP, Giles GR, Irving HC. Ureteric complica-

occult tumours of 6% and 9% in patients with acquired tions of renal transplantation. Br J Urol 1992; 70: 139–43

renal cystic disease (1.5–2% in all patients presenting for 8 Gibbons WS, Barry JM, Hefty TR. Complications following

transplantation) [37,38], but no survival benefit has been unstented parallel incision extravesical ureteroneocys-

tostomy in 1,000 kidney transplants. J Urol 1992; 148: 38–

shown by screening. Our current practice is not to screen

40

for the condition but to investigate urological symptoms

9 Benoit G, Blanchet P, Moukarzel M et al. Surgical complica-

according to standard practice. tions in kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc 1994; 26:

The incidence of prostate cancer after renal transplan- 287–8

tation has probably been underestimated because there is 10 Keller H, Noldge G, Wilms H, Kirste G. Incidence, diagnosis,

little screening. This may be of increasing importance and treatment of ureteric stenosis in 1298 renal transplant

with an ageing transplant population and the increasing patients. Transpl Int 1994; 7: 253–7

longevity of grafts. The natural history of the disease in 11 Rigg KM, Proud G, Taylor RM. Urological complications fol-

this population is unknown, especially important as the lowing renal transplantation. A study of 1016 consecutive

low serum testosterone levels often seen with chronic transplants from a single centre. Transpl Int 1994; 7: 120–6

renal failure may be returned to normal with good renal 12 Koga S, Tanabe K, Yagisawa TT, Toma H. Urological compli-

cations in renal transplantation. Transplant Proc 1996; 28:

graft function. The relative benefits of various treatment

1472–3

methods are likely to remain uncertain amongst trans-

13 Cimic J, Meuleman EJ, Oosterhof GO, Hoitsma AJ. Urological

plant patients, and thus with no evidence to the contrary, complications in renal transplantation. A comparison

they should be treated according to standard guidelines. between living-related and cadaveric grafts. Eur Urol 1997;

Men age > 50 years, who may have no urinary symptoms 31: 433–5

if oliguric, should be considered for a DRE and serum PSA 14 Makisalo H, Eklund B, Salmela K et al. Urological complica-

test before transplantation. tions after 2084 consecutive kidney transplantations. Trans-

plant Proc 1997; 29: 152–3

15 Junjie M, Jian X, Lixin Y, Xiwen B. Urological complications

Conclusion and effects of double-J catheter in ureterovesical anastomosis

The major urological complication rate was 6.5% over the after cadaveric kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc 1998;

first 1535 cases of renal transplantation at our centre, and 30: 3013–4

has remained constant for about the last 20 years. Causal 16 Kumar A, Verma BS, Srivastava A, Bhandari M, Gupta A,

Sharma R. Evaluation of the urological complications of

factors were identified and possible changes in practice

living related renal transplantation at a single center during

suggested, the results of which will be apparent over the

the last 10 years: impact of the Double-J stent. J Urol 2000;

next decade. With increasing experience of minimally 164: 657–60

invasive endoscopic and uroradiological techniques, 17 El-Mekresh M, Osman Y, Ali-El-Dein B, El-Diasty T, Ghoneim

the management of complications may be set to change MA. Urological complications after living-donor renal trans-

simultaneously. plantation. BJU Int 2001; 87: 295–306

18 Cecka JM. The UNOS Scientific Renal Transplant Registry.

Clin Transpl 1998: 1–16

References

19 Morris PJ, Johnson RJ, Fuggle SV, Belger MA, Briggs JD.

1 Jaskowski A, Jones RM, Murie JA, Morris PJ. Urological com- Analysis of factors that affect outcome of primary cadaveric

plications in 600 consecutive renal transplants. Br J Surg renal transplantation in the UK. HLA Task Force of the

1987; 74: 922–5 Kidney Advisory Group of the United Kingdom Transplant

2 Shoskes DA, Hanbury D, Cranston D, Morris PJ. Urological Support Service Authority (UKTSSA). Lancet 1999; 354:

complications in 1,000 consecutive renal transplant recipi- 1147–52

ents. J Urol 1995; 153: 18–21 20 Roake JA, Toogood GJ, Cahill AP, Gray DW, Morris PJ. Reduc-

3 Mundy AR, Podesta ML, Bewick M, Rudge CJ, Ellis FG. The ing renal ischaemia during transplantation. Br J Surg 1991;

urological complications of 1000 renal transplants. Br J Urol 78: 121

1981; 53: 397–402 21 Politano VA, Leadbetter WF. An operative technique for the

4 Sagalowsky AI, Ransler CW, Peters PC et al. Urologic compli- correction of vesicoureteric reflux. J Urol 1958; 79: 932

cations in 505 renal transplants with early catheter removal. 22 Lich R, Howerton LW, Davis LA. Recurrent urosepsis in

J Urol 1983; 129: 929–32 children. J Urol 1961; 86: 554

5 Loughlin KR, Tilney NL, Richie JP. Urologic complications in 23 Barry JM. Unstented extravesical ureteroneocystostomy in

718 renal transplant patients. Surgery 1984; 95: 297– kidney transplantation. J Urol 1983; 129: 918–9

302 24 Thrasher JB, Temple DR, Spees EK. Extravesical versus

6 Ohl DA, Konnak JW, Campbell DA, Dafoe DC, Merion RM, Leadbetter-Politano ureteroneocystostomy. a comparison of

Turcotte JG. Extravesical ureteroneocystostomy in renal urological complications in 320 renal transplants. J Urol

transplantation. J Urol 1988; 139: 499–502 1990; 144: 1105–9

© 2002 BJU International 90, 627–634

634 E.H. STREETER et al.

25 Butterworth PC, Horsburgh T, Veitch PS, Bell PR, Nicholson 34 Gittes RF, Waters WB. Sexual impotence: the overlooked

ML. Urological complications in renal transplantation. complication of a second renal transplant. Trans Am Assoc

impact of a change of technique. Br J Urol 1997; 79: 499– Genitourin Surg 1978; 70: 110–1

502 35 Schmidt R, Stippel D, Krings F, Pollok M. Malignancies of the

26 Nicol DL, P’Ng K, Hardie DR, Wall DR, Hardie IR. Routine use genito-urinary system following renal transplantation. Br J

of indwelling ureteral stents in renal transplantation. J Urol Urol 1995; 75: 572–7

1993; 150: 1375–9 36 Sheil AGR. Cancer report of the Australia and New Zealand

27 Lin LC, Bewick M, Koffman CG. Primary use of a double J Dialysis and Transplant Registry. In Disney APS, ed. 22nd

silicone ureteric stent in renal transplantation. Br J Urol Annual Report of the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis

1993; 72: 697–701 and Transplant Registry. Adelaide, South Australia, 2000

28 Benoit G, Blanchet P, Eschwege P, Alexandre L, Bensadoun 37 Gulanikar AC, Daily PP, Kilambi NK, Hamrick-Turner JE,

H, Charpentier B. Insertion of a double pigtail ureteral stent Butkus DE. Prospective pretransplant ultrasound screening

for the prevention of urological complications in renal trans- in 206 patients for acquired renal cysts and renal cell carci-

plantation: a prospective randomized study. J Urol 1996; noma. Transplantation 1998; 66: 1669–72

156: 881–4 38 Heinz-Peer G, Schoder M, Rand T, Mayer G, Mostbeck GH.

29 Bassiri A, Amiransari B, Yazdani M, Sesavar Y, Gol S. Renal Prevalence of acquired cystic kidney disease and tumours in

transplantation using ureteral stents. Transplant Proc 1995; native kidneys of renal transplant recipients: a prospective US

27: 2593–4 study. Radiology 1995; 195: 667–71

30 Dominguez J, Clase CM, Mahalati K et al. Is routine ureteric

stenting needed in kidney transplantation? A randomized

trial. Transplantation 2000; 70: 597–601

31 Kohri K, Yamate T, Amasaki N et al. Characteristics and Authors

usage of different ureteral stent catheters. Urol Int 1991; 47: E.H. Streeter, MRCS.

131–7 D.M. Little, FRCS.

32 Reinberg Y, Bumgardner GL, Aliabadi H. Urological aspects D.W. Cranston, FRCS.

of renal transplantation. J Urol 1990; 143: 1087–92 P.J. Morris, PRCS.

33 Salvatierra O Jr, Fortmann JL, Belzer FO. Sexual function of Correspondence: E. Streeter, Department of Urology, Churchill

males before and after renal transplantation. Urology 1975; Hospital, Oxford, OX3 7LJ, UK.

5: 64–6 e-mail: edwardstreeter@hotmail.com

© 2002 BJU International 90, 627–634

You might also like

- Ureteric ComplicationsDocument7 pagesUreteric ComplicationstnsourceNo ratings yet

- Use of Locking-Loop Pigtail Nephrostomy Catheters in Dogs and Cats 20 Cases (2004 2009)Document10 pagesUse of Locking-Loop Pigtail Nephrostomy Catheters in Dogs and Cats 20 Cases (2004 2009)Bernardo BertoldiNo ratings yet

- Stenting in Pediatric TransplantationDocument27 pagesStenting in Pediatric TransplantationChris FrenchNo ratings yet

- Urologic Complications in Renal Transplants: Hannah R. Choate, Laura A. Mihalko, Bevan T. ChoateDocument7 pagesUrologic Complications in Renal Transplants: Hannah R. Choate, Laura A. Mihalko, Bevan T. ChoateNidhin MathewNo ratings yet

- Plication of DJ Stents WceDocument1 pagePlication of DJ Stents Wcejinsi georgeNo ratings yet

- Revisiting The Predictive Factors For Intra-Op-erative Complications of Rigid UreterosDocument8 pagesRevisiting The Predictive Factors For Intra-Op-erative Complications of Rigid UreterosTatik HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Marion 2020Document7 pagesMarion 2020hezzaNo ratings yet

- Icu 60 21Document8 pagesIcu 60 21manueljna2318No ratings yet

- Urinary Calculi in Aviation Pilots: What Is The Best Therapeutic Approach?Document3 pagesUrinary Calculi in Aviation Pilots: What Is The Best Therapeutic Approach?NaifahLuthfiyahPutriNo ratings yet

- A Novel Technique For Treatment of Distal Ureteral Calculi: Early ResultsDocument4 pagesA Novel Technique For Treatment of Distal Ureteral Calculi: Early ResultsTheQueensafa90No ratings yet

- Complications of Biliary T-Tubes After Choledochotomy: Original ArticleDocument4 pagesComplications of Biliary T-Tubes After Choledochotomy: Original ArticleBikash SahNo ratings yet

- NeurogenicbladdermanagementwithcompleteurethraldistructionDocument11 pagesNeurogenicbladdermanagementwithcompleteurethraldistructionPutri Rizky AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Transurethral Incision of Ureterocele: Does The Time of Presentation Affect The Need For Further Surgical Interventions?Document6 pagesTransurethral Incision of Ureterocele: Does The Time of Presentation Affect The Need For Further Surgical Interventions?ErikNo ratings yet

- Organ Transplantation Historial Perspective and Current PracticeDocument14 pagesOrgan Transplantation Historial Perspective and Current Practicehkdawnwong100% (1)

- Reconstruction of Late-Onset Transplant Ureteral Stricture DiseaseDocument6 pagesReconstruction of Late-Onset Transplant Ureteral Stricture DiseaseAnanda KumarNo ratings yet

- Reconstruction of Late-Onset Transplant Ureteral Stricture DiseaseDocument7 pagesReconstruction of Late-Onset Transplant Ureteral Stricture DiseasetnsourceNo ratings yet

- Yu 2013Document4 pagesYu 2013raissametasariNo ratings yet

- Chung 2004Document4 pagesChung 2004raghad.bassalNo ratings yet

- Finally Ileal Ureter Corrected (1) (1) IbjuDocument11 pagesFinally Ileal Ureter Corrected (1) (1) IbjuSheshang KamathNo ratings yet

- Tugas Urologi Long Term PostDocument11 pagesTugas Urologi Long Term PostI Gusti Ngurah Nanda PramanaNo ratings yet

- Article 39794Document4 pagesArticle 39794d.amouzou1965No ratings yet

- Multi-Tract Percutaneous NephrolithotomyDocument5 pagesMulti-Tract Percutaneous Nephrolithotomythanhtung1120002022No ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument9 pagesContent ServerenimaNo ratings yet

- SiddiqueDocument5 pagesSiddiqueAman ShabaNo ratings yet

- Surgical Techniques of Kidney Transplantation: Christopher J.E. Watson, Peter J. Friend and Lorna P. MarsonDocument16 pagesSurgical Techniques of Kidney Transplantation: Christopher J.E. Watson, Peter J. Friend and Lorna P. Marsonw5rh7kqg6pNo ratings yet

- Nephro-Urology Monthly Nephro-Urology Monthly Nephro-Urology MonthlyDocument3 pagesNephro-Urology Monthly Nephro-Urology Monthly Nephro-Urology MonthlyTheQueensafa90No ratings yet

- bien chung nieu mổ lấy thaiDocument4 pagesbien chung nieu mổ lấy thaiMint For MomsNo ratings yet

- Complications of Percutaneous Nephrostomy Tube Placement To Treat NephrolithiasisDocument4 pagesComplications of Percutaneous Nephrostomy Tube Placement To Treat NephrolithiasisPande Made FitawijamariNo ratings yet

- Management of Feline Ureteral Obstructions: An Interventionalist's ApproachDocument6 pagesManagement of Feline Ureteral Obstructions: An Interventionalist's ApproachvetgaNo ratings yet

- V34n4a05 PDFDocument10 pagesV34n4a05 PDFvictorcborgesNo ratings yet

- Ju 0000000000000840 07Document2 pagesJu 0000000000000840 07Eksa RachmadiansyahNo ratings yet

- Ureteral Stent For Ureteral Stricture: James F. Borin and Elspeth M. McdougallDocument13 pagesUreteral Stent For Ureteral Stricture: James F. Borin and Elspeth M. McdougallOoNo ratings yet

- Clinical Study: Parameters That May Be Used For Predicting Failure During Endoscopic Retrograde CholangiopancreatographyDocument6 pagesClinical Study: Parameters That May Be Used For Predicting Failure During Endoscopic Retrograde CholangiopancreatographyAkansh DattaNo ratings yet

- Wrap Plication of Megaureter Around Normal-Sized Ureter For Complete Duplex System ReimplantationsDocument5 pagesWrap Plication of Megaureter Around Normal-Sized Ureter For Complete Duplex System ReimplantationsDirga Rasyidin LNo ratings yet

- The Experience of A Tertiary Referral Center With Laparoscopic Pyelolithotomy For Large Renal Stones During 18 YearsDocument8 pagesThe Experience of A Tertiary Referral Center With Laparoscopic Pyelolithotomy For Large Renal Stones During 18 YearsDaniel StrubNo ratings yet

- Advances in Urinary Tract EndosDocument23 pagesAdvances in Urinary Tract EndosJosé Moreira Lima NetoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2667008923000253 MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S2667008923000253 Mainal malikNo ratings yet

- Adam 2017Document4 pagesAdam 2017Bandac AlexandraNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Open and Laproscopic Live Donor NephrectomyDocument7 pagesComparison of Open and Laproscopic Live Donor NephrectomyEhab Omar El HalawanyNo ratings yet

- Horshoe KidneDocument5 pagesHorshoe KidneteguhdjufriNo ratings yet

- SC 2015242Document7 pagesSC 2015242resi ciruNo ratings yet

- Endourology and Stone Diseases: Original ArticlesDocument5 pagesEndourology and Stone Diseases: Original ArticlesTatik HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Transplantation of Organs Feasible or Practical?: Wizen IsDocument32 pagesTransplantation of Organs Feasible or Practical?: Wizen IswunderfullifeNo ratings yet

- Corresponding Member of National Academy of Science Of, Academician of RussianDocument4 pagesCorresponding Member of National Academy of Science Of, Academician of RussianRavilNo ratings yet

- Open Access Journal of Urology & Nephrology: Interventional Radiology Techniques in The Genitourinary TractDocument5 pagesOpen Access Journal of Urology & Nephrology: Interventional Radiology Techniques in The Genitourinary Tractalfredo elizondoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0039606020306759 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0039606020306759 MainKar RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Tecnica de Clips Nefrectomia ParcialDocument8 pagesTecnica de Clips Nefrectomia ParcialAlfredo BalcázarNo ratings yet

- Pemeriksaan IVPDocument41 pagesPemeriksaan IVPChandra Noor SatriyoNo ratings yet

- 104854-Article Text-283461-1-10-20140701Document6 pages104854-Article Text-283461-1-10-20140701Joan Marie S. FlorNo ratings yet

- Krav Chick 2005Document4 pagesKrav Chick 2005victorcborgesNo ratings yet

- Retrospective Study To Determine The Short-Term Outcomes of A Modified Pneumovesical Glenn-Anderson Procedure For Treating Primary Obstructing Megaureter. 2015Document6 pagesRetrospective Study To Determine The Short-Term Outcomes of A Modified Pneumovesical Glenn-Anderson Procedure For Treating Primary Obstructing Megaureter. 2015Paz MoncayoNo ratings yet

- Pancreatic ®stula After Pancreatic Head ResectionDocument7 pagesPancreatic ®stula After Pancreatic Head ResectionNicolas RuizNo ratings yet

- PublicationDocument7 pagesPublicationmagnusspecialityreportsNo ratings yet

- Yan 2015Document4 pagesYan 2015ELIECERNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Retrograde Intrarenal Surgery and Standard Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy For Management of Stones at Ureteropelvic Junction With High-Grade HydronephrosisDocument5 pagesComparison of Retrograde Intrarenal Surgery and Standard Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy For Management of Stones at Ureteropelvic Junction With High-Grade Hydronephrosisyicini2524No ratings yet

- Complex Case of Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction 2024 International JournaDocument3 pagesComplex Case of Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction 2024 International JournaRonald QuezadaNo ratings yet

- Review StrikturDocument13 pagesReview StrikturFryda 'buona' YantiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2405456920302133 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S2405456920302133 MainMeta ParamitaNo ratings yet

- Whole Ovary TransplantationDocument7 pagesWhole Ovary Transplantationari naNo ratings yet

- Critical Care for Potential Liver Transplant CandidatesFrom EverandCritical Care for Potential Liver Transplant CandidatesDmitri BezinoverNo ratings yet

- List of Companies With Contact Details For Global VillageDocument5 pagesList of Companies With Contact Details For Global VillagemadhutkNo ratings yet

- + Eldlife I: 170,000.00 Total Amount Total Amount Before Tax 170,000.00 170,000.00Document1 page+ Eldlife I: 170,000.00 Total Amount Total Amount Before Tax 170,000.00 170,000.00Kaifi asgarNo ratings yet

- Laura Su ResumeDocument1 pageLaura Su Resumeapi-280311314No ratings yet

- Chapter 15 - Designing and Managing Integrating Marketing CommunicationsDocument28 pagesChapter 15 - Designing and Managing Integrating Marketing CommunicationsArmanNo ratings yet

- DECAA - Letter To DC Gov't Officials Re DPW Causing Explosion in Rat PopulationDocument22 pagesDECAA - Letter To DC Gov't Officials Re DPW Causing Explosion in Rat PopulationABC7NewsNo ratings yet

- Ngá Nghä©a Unit 4Document5 pagesNgá Nghä©a Unit 4Nguyen The TranNo ratings yet

- Onkyo tx-nr737 SM Parts Rev6Document110 pagesOnkyo tx-nr737 SM Parts Rev6MiroslavNo ratings yet

- Equity ApplicationDocument3 pagesEquity ApplicationanniesachdevNo ratings yet

- Legendary RakshashaDocument24 pagesLegendary RakshashajavandarNo ratings yet

- Loans and MortgagesDocument26 pagesLoans and Mortgagesparkerroach21No ratings yet

- Amazon Invoice - Laptop Stand PDFDocument1 pageAmazon Invoice - Laptop Stand PDFAl-Harbi Pvt LtdNo ratings yet

- Pattern Recognition: Zhiming Liu, Chengjun LiuDocument9 pagesPattern Recognition: Zhiming Liu, Chengjun LiuSabha NayaghamNo ratings yet

- Zumba DLPDocument8 pagesZumba DLPJohnne Erika LarosaNo ratings yet

- NDT Basics GuideDocument29 pagesNDT Basics Guideravindra_jivaniNo ratings yet

- Part 2 Twentieth Century Naval Dockyards Devonport and Portsmouth Characterisation ReportDocument52 pagesPart 2 Twentieth Century Naval Dockyards Devonport and Portsmouth Characterisation ReportToby ChessonNo ratings yet

- Wine Enthusiast - May 2014Document124 pagesWine Enthusiast - May 2014Johanna Shin100% (1)

- Acknowledgement ItrDocument1 pageAcknowledgement ItrSourav KumarNo ratings yet

- Of The Abdominal Wall, Abdominal Organs, Vasculature, Spinal Nerves and DermatomesDocument11 pagesOf The Abdominal Wall, Abdominal Organs, Vasculature, Spinal Nerves and DermatomesentistdeNo ratings yet

- Dodla Dairy Hyderabad Field Visit 1Document23 pagesDodla Dairy Hyderabad Field Visit 1studartzofficialNo ratings yet

- Proprietary & Confidential: This Is A Static Sensitive Device. Handle & Store Appropriately To Prevent Esd DamageDocument2 pagesProprietary & Confidential: This Is A Static Sensitive Device. Handle & Store Appropriately To Prevent Esd DamagePawan PalNo ratings yet

- EC506 Wireless Gateway User Manual ENGDocument48 pagesEC506 Wireless Gateway User Manual ENGcy5170No ratings yet

- Mixers FinalDocument44 pagesMixers FinalDharmender KumarNo ratings yet

- 305-1-Seepage Analysis Through Zoned Anisotropic Soil by Computer, Geoffrey TomlinDocument11 pages305-1-Seepage Analysis Through Zoned Anisotropic Soil by Computer, Geoffrey Tomlinد.م. محمد الطاهرNo ratings yet

- Salt Market StructureDocument8 pagesSalt Market StructureASBMailNo ratings yet

- Apurba MazumdarDocument2 pagesApurba MazumdarDRIVECURENo ratings yet

- British Deputy High Commission in KarachiDocument1 pageBritish Deputy High Commission in KarachiRaza WazirNo ratings yet

- Prolin Termassist Operating Guide: Pax Computer Technology Shenzhen Co.,LtdDocument29 pagesProlin Termassist Operating Guide: Pax Computer Technology Shenzhen Co.,Ltdhenry diazNo ratings yet

- List of Goosebumps BooksDocument10 pagesList of Goosebumps Booksapi-398384077No ratings yet

- 510 - Sps Vega vs. SSS, 20 Sept 2010Document2 pages510 - Sps Vega vs. SSS, 20 Sept 2010anaNo ratings yet

- Seismic Sequence Stratigraphy - PresentationDocument25 pagesSeismic Sequence Stratigraphy - PresentationYatindra Dutt100% (2)