Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Transfusion C PL Icat I0 Ns

Transfusion C PL Icat I0 Ns

Uploaded by

Pritha BhuwapaksophonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Transfusion C PL Icat I0 Ns

Transfusion C PL Icat I0 Ns

Uploaded by

Pritha BhuwapaksophonCopyright:

Available Formats

T R A N S F U S I O N C O M PL I C A T I 0 N S

Predictive value of past and current screening tests for

syphilis in blood donors: changing from a rapid plasma reagin

test to an automated specific treponemal test for screening

I. Aberle-Grasse, S.L. Orton, E. Notari IV, L.P. Layug, R.G. Cable,

S. Badon, M.A. Popovsky, A,]. Grindon, B.A Lenes, and A.E. Williams

S

erologic screening tests for syphilis have been per-

BACKGROUND: This study evaluated the change from formed on the blood supply for 50 years.’ Until

a rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test to an automated spe- recently, a reagin-based test (e.g.,rapid plasma

cific treponemal test (PK-TP) in screening for syphilis in reagin [RPR]) had been used.The high rate of false-

blood donors. positive reactionsin low-riskpopulations attributable to the

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS: A cross-sectional RPR test and the inefficiency and subjectivity of manual

seroprevalenceanalysis was performed on 4,878,215 screening led to the implementation of an automated spe-

allogeneic blood donations from 19 American Red Cross cific treponemal test (PK-TT:Olympus Corp.,Lake Success,

Blood Services regions from May 1993 through Septem- NY) in most American Red Cross (ARC) blood centers over

ber 1995. Positive predictive values relative to the confir- the past 10 years. The change from the RPR to the PK-TP

matory fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test was phased in between April 1990 and October 1995 in the

(FTA-ABS) were calculated.Differences in seroprevalence 19 regions studied.

were compared in RPR and PK-TPtests for 1) uncon- Blood components from donations with repeatedly re-

firmed and confirmedtests, 2) first-time and repeat do- active results on serologic testingfor syphilis (STS) are rou-

nors, and 3) “recent” versus “past” infections. Donation tinely discarded without reference to the results of a rou-

data from three additional Red Cross regions were evaiu- tine fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS)

ated for repeat donation patterns of blood donors who had confirmatorytest. Currently,donors who do not have a con-

a donation that was positive in a serologic screening test firmed-positivedonationmay donate again,and donors with

for syphilis.The value of RPR and PK-TPtests as surro-

gate markersfor HIV infectionwas compared.

RESULTS: Reactive rates were lower but the positive pre- ABBREVIATIONS: ARC =American Red Cross;ARCBS = ARC

dictive values was higher for the PK-TP test than for the Blood Services;FTA-ABS = fluorescent treponemal antibody ab-

RPR test. Initially, donors screened by PK-TP were more sorption (test);PK-TP = trade name for an automated specific

likely to be confirmedas positivethan were donors treponemal test for syphilis; PK-TPl = PK-TP test before

screened by RPR, but these rates became comparable. diluent modification; PK-TP2 = PK-TP test after diluent modi-

It is estimated that a single HIV window-period donation fication; PPV(s) = positive predictive value(s);RPR = rapid

was removed by serologic testing for syphilis each year plasma reagin (test);STS = serologic testing for syphilis.

of this study period. From the Holland Laboratory, American Red Cross Blood Ser-

CONCLUSIONS:The change to the PK-TP test resulted vices; and the American Red Cross National Reference Labo-

in a lower repeatedly reactive rate, better prediction that ratory for Infectious Diseases, Rockville, Maryland: and Ameri-

’ a confirmed-positive test for syphilis would occur in test-

ing in the FTA-ABS, fewer donations lost, and compa-

can Red Cross Services: the Connecticut Region, Hartford,

Connecticut; New England Region, Dedham, Massachusetts;

rable deferral rates. Because of the high rate of reactivity Atlanta Region, Atlanta, Georgia; and Miami Region, Miami,

to serologic testing for syphilis among donors previously Florida.

confirmed positive for syphilis, indefinite deferral after a Supported in part by the American Red Cross Biomedical

confirmed-positive index donation may be warranted. ServicesARCNET Epidemiological Research and Surveillance

Serologic testing for syphilis is ineffective as a marker of Program.

HIV-infectiouswindow-period donations. Received for publication April 21, 1998;revision received

June 18,1998,and accepted June25,1998.

TRANSFUSION 1999;39:206-211.

206 TRANSFUSION Volume 39, February 1999

SEROLOGIC TESTING FOR SYPHILIS

a confirmed-positive donation are deferred for 1 year after Tkpowmupallidum itself.These antibodiesare also produced

completion of therapy but may then be re-entered into the in response to tissue damage from other nontreponemal dis-

donor ~ 0 0 1 . ~ ease. This type of test has been used historicallyas a screening

Onlytwo cases of transfusion-transmitted syphilishave test in blood centers. Because a reactive test in infected indi-

been reported in the literature in the past 30 years.3 How- viduals is a good indication of disease activity,it is also used

ever, a compelling reason for the continued used of STS, to follow patients’ responses to therapy.When used specifi-

according to a National Institutes of Health Consensus Con- cally to monitor for syphilis infection, this test becomes

f e r e n ~ eis, ~that the extent to which STS contributes to the nonreactive 6 to 12 months after successful treatment of

current absence of posttransfusion syphilis is unknown. A primary syphilis and up to 2 years after successfultreatment

further reason given to continue STS is its potential utility as of secondary syphilis. Specifictreponemal tests include the

a surrogate marker for other infections, such as HIY4 FTA-ABS and the ?: pallidurn hemagglutination tests. The

This study compared repeatedlyreactiveand confirmed- FTA-ABS is a standard indirect immunofluorescence anti-

positive rates in first-time and repeat donors, positive pre- body test. False-positive results are known occur; the fre-

dictive values (PPVs)of the RPR and PK-TP tests relative to quency is greater in low-riskpopulations and the elderly.The

FTA-ABS test, and differences in PK-TP testing before (PK- T pallidum hemagglutination test measures specifictrepone-

TP1) and after (PK-TP2)diluent modification bythe manu- mal antibody by using passive agglutination of red cells sen-

facturer that was designed to reduce the rate of false-posi- sitized with a ~ ~ t i g e Specific

n . ~ . ~ antitreponemal tests provide

tive reactions. Also analyzed were sex and age group the earliest positive test results and are used for detecting

differences in “recent” (RPR+)and “past”(RPR-1 infection the likelihoodof any infection,past or recent.’a8 The PK-TP is

rates in donors with positive PK-TP tests confirmed by FTA- an automated hemagglutinationtest developed primarilyfor

ABS, serologic results and return donation patterns of blood blood banking.

donors who are positive in both the RPR and the PK-TP and Our laboratory test data included the results of STS by

confirmed in the FTA-ABS, and the value of RPR and PK-TP the RPR, PK-TP1, and PK-TP2tests. The change from the RPR

to the PK-TP occurred at various times between April 1990

as surrogate markers for HI\!

and September 1995 for individual centers. Donors tested

by the PK-TPl and PK-TP2 tests had significantlydifferent

MATERIALS AND METHODS confirmatory test results and therefore were analyzed sepa-

Source population rately. All donations with reactive screeningtests underwent

confirmatory testing at the ARC National Reference Labo-

Donation and laboratory test data were collected from

ratory for Infectious Diseases using a standard method of

4,878,215allogeneic blood donations at 19ARC Blood Ser-

FTA-ABS.5

vices (ARCBS)regions from May 1993 through September

A confirmed test result was defined as RPR+ or PK-TP+

1995.The 19 study regions for which complete data from STS

and FTA-ABS+.A confirmed test result does not necessarily

were available were selected from the ARCNET data system.

mean true infection, as no gold standard for infectivitywas

These data represented about 43 percent of the total blood

used. Afalse-positivetest result was defined as RPR+or PK-

collections in the ARCBS regions during this study period.

TP+ and FTA-ABS-. To assess recent infection, the RPR test

Data comparing first-time donors to repeat donors are eco- was performed on samples with positive results in the PK-

logic; that is, comparisonsare made between different groups TP test that were confirmed with FTA-ABS. Recent infection

during the same time period. Additional data on a subset of was defined as PK-TP+,FTA-ABS+,and RPR+ (PK-TP+/FTA-

651,087 allogeneic blood donations from three ARCBS re- ABS+IRPR+).Past infection was defined as PK-TP+, FTA-

gions were used to evaluate serial donations. The following ABS+, and RPR- (PK-TP+/FTA-ABS+/RPR-).

demographic information was collected for all of the dona-

tions: the donor’sprevious donation date, the donation type Statistical calculations

(allogeneicor autologous),first-timeor repeat donation, and PPVs of the RPR and the PK-TP tests relative to the FTA-ABS

the donor’sself-exclusionstatus, as well as each donor’sdate test were calculated (note: not true positive;see above). Fre-

of birth, age, and sex. Laboratory screening and confirma- quency distributions were calculated for RPR- and PK-TP-

tory data were also collected. Donors were classified as re- unconfirmed and -confirmed seroprevalence. Differences

peat if they had donated in the previous 3 years; otherwise, in screeningmethods were assessed by the Mantel-Haenszel

theywere classified as first-time. chi-square test usingsoftware (EpiInfo,Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA) for sex and age group

Laboratory testing strata (17-24,25-39,40-64,65and older). Because of mul-

Nonspecific reagin tests for syphilis (VDRL [VeneralDisease tiple comparisons and large samples, a p value of 10.01was

Reference Laboratory],RPR) involve testing for IgG and IgM considered significant?

antibodies to cardiolipin (reagin)antigen that are generated Retum-donationpatterns and confirmation frequencies

as a result of interaction between infected host tissues and were calculatedusing data from 651,087 serial donations in a

Volume 39,February 1999 TRANSFUSION 207

ABERLE-GRASSE ET AL.

three-region subset. In this subset, donors screenedwith PK- and PK-TP2-positiveresults were more likely to be confirmed

TP1 and PK-TP2 are analyzed together because of the small by FTA-ABSthan were RPR-positiveresults, (6 and 7 times,

numbers. respectively).The highest PPV, relative to confirmatory test-

The correlation between positive results in the RPR and ing by FTA-ABS, was found by using PK-TP2 as the test of

the PK-TP tests and HIVinfection was assessed by calcula- record; it also indicated an increase in the specificityof the

tion of the odds ratio as an estimate of relative risk. To esti- PK-TP2 test. However, it can be seen in Table 2 that, when

mate the number of window-period donations removed by stratified, this confirmed rate is lower in repeat donors pre-

STS, the technique of Herrera et al.1° was applied by using viously screened by PK-TI?There was also a decrease from

previously published risk estimates for window-period do- PK-TPl to PK-TP2 in the rate of confirmed-positive results

nations and multiplying them by the proportion of donors for both first-time and repeat donors. Stratification by sex

with confirmed HIVinfections in whom STS was also posi- and age can be seen in Fig. 1. Results of PK-TP2 testing were

tive, but who were negative for other screeningtests and who significantlydifferent from those of PK-TP1 testing in all age

did not self-defer.This calculation assumes that infectious strata, regardless of sex, with the exception of the group aged

window-period donations have the same ratio of positive 17- to 24-years old and women over 65 years of age.

syphilisscreeningtest results and other test results as do con-

firmed HIV-positivedonations.The published risk estimate Recent versus past infection

used for HIV-1 window-period donations during the study A comparison of recent (PK-TP+/FTA-ABS+/RPR+ ) and past

period was 1 in 450,000donations.' The estimate of the total (PK-TP+/FTA-ABS+/RPR-)infection rates in donors tested

number of blood donations collected nationally in 1 year with PK-TP2 can be seen in Fig. 2. Estimates of recent infec-

during the study was 12 million donations.IOFor compari- tion rates are higher than past rates in 17- to 24-year-olds,

son purposes, the number of cases removed by STS in our regardless of sex. These rates reverse themselves for the age

study was multiplied by the quotient of our study popula- groups over 24.

tion divided by 12 million.

RESULTS

Repeatedly reactive and TABLE 1. PPV of study population (4,878,215 allogeneic donations from 19

confirmatory rates and PPV ARCBS regions)between Mav 1993 and SeDtember 1995

For the study population of4,878,215, Number positive Number

in STS confirmed

the results of the screening and con- (% of total (% of total

firmatory testing and the PPVs are donations tested) donations tested) PPV(%)

shown inTable 1.Thechangefrom RPR RPR (n = 1,738,331) 4,591 (0.26) 391 (0.02) 8.5

to PK-TP2 apparently decreased the PK-TP1 (n = 1,338,379) 2,800 (0.21) 1,494 (0.11) 53.4

First-time donors (0.28)

number of reactive tests by more than Repeat donors (0.08)

half. The differences in the percentage PK-TP2 (n = 1,801,505) 2,151 (0.12) 1,274 (0.07)* 59.2t

of repeatedly reactive results for PK- First-time donors (0.22)

Repeat donors (0.04)

TP1 and PK-TP2 can be seen as a de- PK-TPl vs. PK-TP2 chi-square, 145.64; p value <0.00001.

crease of 43 percent. Both PK-TP1- t PK-TP1 vs. PK-TP2 chi-square,l6.54; p value = 0.00004.

TABLE 2. Seroprevalenceof first-time and repeat allogeneic donations when tested by RPR and PK-TP'

First-time donorst Repeat donors*

Number positive in STS Number confirmea Number positive in STS Number confirmed Percentage

(Yoof total (% of number (Yoof total Percentage of number of total

donations tested) positive in STS)§ donations tested) positive in STS)§ donations tested

RPR 993 (0.31) 160 (16.1) 3,598 (0.26) 230 6.4 0.02

PK-TP 1,825 (0.35) 1,278 (70.0) 2,924 (0.11) 0.08

Previous RPR 1,550 (0.24) 998 63.8 0.16

(n = 641,239)

Previous PK-TP 1,374 (0.08) 502 31.9 0.03

(n = 1.978.029)

Data comparing first-time donors to repeat donors are ecologic; that is, comparisons are made between different groups during the same

time period.

t RPR = 323,821; PK-TP = 518,505.

+ RPR = 1,410,000; PK-TP = 2,619,268.

5 PPV.

208 TRANSFUSION Volume 39, February 1999

SEROLOGIC TESTING FOR SYPHILIS

0 18 positive and repeat donors previously

tested by PK-TPwho were confirmed

0 16

as positive.

In repeat donors, the rate of con-

-.-

0

0

4

014

firmed positives as a percentage of the

fn 012 total population tested with RPR was

-

0

0.02 percent. With the PK-TP test (do-

6 01

nors previously tested by RPR), this

-m

0

5 008 rate initiallyincreased to 0.16 percent.

h

L

a

2

0, 006

However, over time this rate de-

5P creased to 0.03percent which is almost

,f 004

as low as that with RPR.

0 02 RPR and PK-TP as a surrogate

markers for HIV infection

0

c a u m

i u)

u-) The correlation between positive re-

- N

sults in RPR and PK-TP tests and HIV

Age groups and sex infection was evaluated by calcula-

* p value ~0.01.

Fig. 1. PK-TP1 (m) versus PK-TP2 (0). tion of the odds ratio, defined as the

ratio of the probability of a confirmed

HIV-positive result given a con-

0 18 firmed-positive result in RPR and PK-

TP tests relative to the probability of a

0 16 confirmed HIV-positiveresult given a

0

m 0 14

negative or unconfirmed result in the

e

a

c RPR and the PK-TI? The odds ratios

6

I

012 were calculatedas 157(95%CI ,49-502)

for RPR and 149 (95%CI, 84-267)for

i-

-

m

e

01

008

P K - n which were not significantlydif-

ferent. The estimated number of po-

% tential infectious window-period do-

E 006 nations removed by RPR and PK-TP

0 screening nationally per year was ob-

004

tained by multiplying the window-pe-

0 02 riod risk" (1/450,000)by the percent-

age of HIV+ and RPR+ or PK-TP+

0

donations divided by all other tests

B (3.4% for RPR, 3.7%for PK-TP2) times

Age groups and sex

12 million donations. It was found to

Fig. 2. Recent (m) versus past (0)

infection in PK-TP2. be 0.9 donations for RPR and 1.0 do-

nations for PIC-TP2. These values are

not significantlydifferent.

First-time versus repeat donors, unconfirmed and Retention of donated components and deferral of

confirmed seroprevalence donors; return donation patterns

InTable 2, the data comparing first-time donors tested with As a result of the increase in specificityof PK-TP compared

RPR and those tested with PK-TP show similar, uncon- to RPR, over this studyperiod, 3140additional donationswere

firmed rates. While this rate decreased only slightly in re- availablein the study population. However,as seen in Table

peat donors tested with RPR, with PK-TR the rate in repeat 1,the greater confirmation rate associated with PK-TP2 test-

donors decreased to 0.11 percent. The PK-TP-reactiverate ing than with RPR testing resulted in 9000 more donor de-

in repeat donors was higher in those who had previouslybeen ferrals during this time period.

screened by RPR than in those who had previously been Results of tests of subsequent donations after a con-

screened by PK-TP Differencescan also be seen in the rate firmed-positivedonation in the subset of 651,087are seen in

of first-time donors tested by PK-TP who were confirmed as Table 3. Fewer donors were confirmed as positive on all sub-

Volume 39, February 1999 TRANSFUSION 209

ABERLE-GRASSE ET AL.

sequent donations when tested with RPR than with PK-TF? of automation and the elimination of the ambiguity associ-

Regardless of the screeningtest, few individualswho are con- ated with the manual reading of the RPR.

firmed as positive for syphilis on a donation return to do- The higher prevalence of past infection relative to re-

nate. cent infection in older groups is expected, because of cu-

mulative exposure and the higher incidence of syphilis in

the past. The greater number of recent infections seen in

DISCUSSION the group aged 17 to 24 screened with PK-TP2 is expected,

The low specificity of the nontreponemal RPR test in the because donors in this group have had less total lifetime ex-

blood donor population is well documented. The observed posure and more recent exposure, which is most closely

higher PPV of PK-TP for syphilis antibody (confirmed as associated with current syphilis infection. First-time donors

positive) is consistent with previously published data.3This are more likely to screen repeatedly reactive and to be con-

finding is not surprising, as the PK-TP and the FTA-ABS firmed as positive than repeat donors tested with both RPR

have the same antigenic specificity. Because the same dis- and PK-TI! This is not surprising and is consistent with pre-

ease states that cause false-positive results in reagin-based viously published studies that found that the rate of risk

tests for syphilis are known to cause false-positive results behavior meriting deferral is higher in first-time blood do-

in the other test^,^-^ the value of STS as a predictor of infec- nors,12as is the incidence rate of infectious disease mark-

tivity in the blood donor population is unknown. er~.'~

According to the manufacturer, the diluent modifica- The higher rates in donors previously tested only with

tion from PK-TP1 to PK-TP2 resulted in higher specificity the RPR than in those previously tested with the PK-TP may

and therefore a decrease in the false-positiverate. However, be a result of the detection by PK-TP of treated andlor re-

our data indicate that there is a difference in the confirma- covered infections that were not detected by RPR. From the

tory rates for PK-TP1 and PK-TP2. Factors that maycontrib- subset of 651,087,it can be seen that donors screened with

Ute to this difference in absolute rate include false-positive the PK-TP and confirmed positive by FTA-ABS are more

repeatedly reactive donations that are confirmed positive likely to remain positive on subsequent donations than

with PK-TP1,the prevalence of syphilis in each population donors screened with RPR, although the return rate for con-

group, first-time:repeat donor ratio, sex or age mix, and a firmed-positive donors is low in both groups. The data seen

decrease in sensitivity of the PK-TP2. It is not known inTable2 support the current policy of allowingSTS-repeat-

whether our data reflect a decrease in sensitivity.Initially,the edly reactive (unconfirmed) donors to return without de-

higher confirmatory rates found after testing by PK-TP than ferral. Conversely,the subset data suggest that it may be ef-

after testing by RPR will be moderated by the proportion of ficacious for PK-TP confirmed-positive donors to be

repeat donors in a given donor population and will deter- permanently deferred,as there is little evidenceof disappear-

mine any difference in the number of donors that will be ance of the antibody. This observation is related to the per-

deferred. Over time, the confirmation rate after PK-TP test- manence of the serologic test result, and not infectivity.

ing as a percentage of the total population tested appears to As a surrogate marker, PK-TP is similar to RPR as a pre-

approach that after RPR testing, although there is a net loss dictor of HIVinfection. Because of the low probability that a

of 0.01 percent of donors due to deferral. However, a sus- donor would be in the window-period for both HIV and

tained higher level of donor deferrals should not be antici- syphilis when his or her blood was collected, it is dubious

pated. Ifwe project the ARCNET data to the current nation- whether any syphilis screening test is an effective surrogate

wide collection estimate of 14 million donations," the marker for HIVinfection.Because the ratio of donations that

difference in the repeatedly reactive rate with RPR and PK- were RPR+ or PK-TP+and HIV+ to donations that were RPR-

TP2 translates to a net retention of approximately 25,000 or PK-TP- and HIV+was much higher in our study than that

more whole-blood units annually (although this is not sub- of the study by Herrera et a1.,I0we calculated that 1potential

stantiated by repeatedlyreactive rates for first-timedonors). case of HIVinfection (assuming 12 million donations annu-

The major argument for the switch to PK-TP is the capability ally)would be prevented nationallyin a year.While our study

calculated twice as many cases as the study by Herrera et al.

(0.2casesl4.5 million donations),our

TABLE 3. Subsequent donations after an STS confirmed-positivedonation results, whether for PK-TP or RPR, are

in the ARCNET group of 651.087 allogeneicdonations over a 3-year period similar to the estimate of the National

Number Number who Subsequent positive Institutes of Health Consensus Con-

confirmed" returned to donate confirmatory testing ferences of less than one HIVcase re-

Total screened (% of total) (Yoof number confirmed) (% of number-confirmed)

moved annually by STS, and they sup-

RPR (n = 228,524) 240 (0.10) 11 (4.6) 3 (27.3)

port that group's conclusion that STS

PK-TP In = 422.5631 215 (0.05) 10 (4.7) 9 (90.01 is not an effective surrogate marker

PPV for HIV i n f e ~ t i o n . ~

210 TRANSFUSION Volume 39, February 1999

SEROLOGIC TESTING FOR SYPHILIS

Many of the evaluationsusing RPR, PK-TE!and FTA-ABS 9. Walter D, Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in

results assume that confirmed-positiveresults represent true cancer research, vol 1. The analysis of case control stud-

infection, either past or recent. l’he rate of false-positivere- ies. Lyon France: IARC Scientific Publications, 1980.

sults is dependent upon the population screened and the test 10. Herrera GA, Lackritz RS, Janssen RS, et al. Serologic test for

used. False-positiveresults have been associated with hepa- syphilis as a surrogate marker for human immunodefi-

titis, mononucleosis,viral pneumonia, chicken pox, measles, ciency virus infection among United States blood donors.

other viral infections, immunizations, pregnancy, and labo- Transfusion 1997;37:836-40.

ratory error. False-positiveresults also have been associated 1 . Facts about blood and blood banking (fact sheet).

with connectivetissue diseases (systemiclupus erythemato- Bethesda: American Association of Blood Banks, 1995.

sus) or diseases associated with hypergammaglobulinemia, 2. Williams AE, Thomson RA, Schreiber GB, et al. Estimates of

narcotic addiction,aging,leprosy, and malignancy?-8In popu- infectious disease risk factors in US blood donors.

lations that are unlikely to have syphilis, false-positive test Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study. JAMA 1997;277:967-

results have been shown to occur at a high rate (0.75%).14In 72.

industrialized nations, a low prevalence in the population 3. Myhre BA, Figueroa PI. Infectious disease markers in vari-

equates to a high false-positive(noninfected) rate of 80 per- ous groups of donors. Ann Clin Lab Sci 1995;25:39-43.

cent or more in donor population^.'^ This high rate of false- 4. Jaffe HW, Larsen SA, Jones OG, Dans PE. Hemagglutination

positive results may explain our calculated rate of 30 cases tests for syphilis antibody. Am J Clin Pathol 1978;70:230-3.

per 100,000,as the estimated annual population incidence 5. Wendel S. Current concepts on the transmission of bacteria

rate of syphilis is 6.3 cases per 100,000population.I6If most and parasites by blood components. Vox Sang 1994;67

of these positive results are false, that observtion supports (SUPPI3):161-74.

the ineffectiveness of using this test as a screen for syphilis 16. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance, 1995. Division

infectivity in the United States blood donors.Consequently, of STD Prevention, US Department of Health and Hu-

further epidemiologic and laboratory study of confirmed- man Services, Public Health Service. Atlanta: Centers for

positive donors is needed to determine the relationship of Disease Control and Prevention, September 1996.

these positive test results to transmissible syphilis infection.

AUTHORS

REFERENCES John Aberle-Grasse, MPH, Project Leader, Transmissible Dis-

eases Laboratory, Jerome H. Holland Laboratory, American Red

1 . Reesink HW, Nydegger UE, Tegtmeier GE, et al. Blood

Cross, 15601 Crabbs Branch Way, Rockville, MD 20855.[Reprint

donor screening or ‘over-screening’: how far to go in requests]

avoiding transmission of infectious agents? (editorial) Vox Sharyn L. Orton, MSPH, Project Leader. Transmissible

Sang 1992;63:59-69. Diseases Laboratory, Jerome H. Holland Laboratory.

2. Menitove J, ed. Standards for blood banks and transfu- Edward Notari IV, MPH, Research Associate, Transmis-

sion services. 18th ed. Bethesda: American Association of sible Diseases Laboratory, Jerome H. Holland Laboratory.

Blood Banks, 1997. Lynne P. Layug, MPH, Director Administrative and Client

3. Cable RG. Evaluation of syphilis testing of blood donors. Services, National Reference Laboratory for Infectious Dis-

Transfus Med Rev 1996;10:296-302. eases, Rockville, MD.

4. Infectious disease testing for blood transfusions. NIH Con- Richard G. Cable, MD, Medical Director, American Red

sensus Panel on Infectious Disease Testing for Blood Cross, Connecticut Region, Hartford, CO.

Transfusions. 1995;274:1374-9.

Stanley Badon, MD, Associate Medical Director, American

5. Larsen SA, Steiner BM, Rudolph AH. Laboratory diagnosis Red Cross, Connecticut Region.

and interpretation of tests for syphilis. Clin Microbiol Rev Mark A. Popovsky, MD, Chief Executive Officer, American

1995;8:1-21.

Red Cross, New England Region, Dedham, MA.

6. Tramont EC. Treponema pallidurn (syphilis). In: Mandell

Alfred J. Grindon, MD, Medical Director, American Red

GL, Bennett JE, D o h R, eds. Mandell. Douglas, and

Cross, Southern Region, Georgia Division, Atlanta, GA.

Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. 4th Bruce A. Lenes, MD, Medical Director, American Red

ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1995:2117-33.

Cross Southern Region, South Florida Division, Miami, FL.

7. Hart G. Syphilis tests in diagnostic and therapeutic deci-

Alan E. Williams, PhD, Senior Research Scientist, Trans-

sion making. Ann Intern Med 1986;104:368-76. missible Diseases Laboratory, Jerome H. Holland Laboratory.

8. Dyckman ID, Storms S, Huber TW. Reactivity of

microhemagglutination, fluorescent treponemal antibody

absorption, and venereal disease research laboratory

tests in primary syphilis. J Clin Microbiol 1980;12:629-30.

Volume 39, February 1999 TRANSFUSION 211

You might also like

- Blood Donors and Blood CollectionDocument7 pagesBlood Donors and Blood CollectionPritha BhuwapaksophonNo ratings yet

- Palacios 1999Document6 pagesPalacios 1999awdafeagega2r3No ratings yet

- Lombriz PCRDocument3 pagesLombriz PCRNorma TamezNo ratings yet

- Natural History of Hepatitis C Virus Carriers WithDocument5 pagesNatural History of Hepatitis C Virus Carriers Withiyadshahatit80No ratings yet

- Serodiagnosis of Syphilis in The Recombinant Era: Reversal of FortuneDocument2 pagesSerodiagnosis of Syphilis in The Recombinant Era: Reversal of FortuneLalan HolalaNo ratings yet

- 1 Retrospective Review of T. Pallidum PCR and Serology Results Are Both Tests 2 NecessaryDocument20 pages1 Retrospective Review of T. Pallidum PCR and Serology Results Are Both Tests 2 NecessaryEmi PephiNo ratings yet

- Manuscript 1Document10 pagesManuscript 1mohammedsherif92No ratings yet

- Diagnostic Accuracy of Xpert MTB/RIF On Bronchoscopy Specimens in Patients With Suspected Pulmonary TuberculosisDocument6 pagesDiagnostic Accuracy of Xpert MTB/RIF On Bronchoscopy Specimens in Patients With Suspected Pulmonary TuberculosisMARTIN FRANKLIN HUAYANCA HUANCAHUARENo ratings yet

- J. Clin. Microbiol.-1984-Schalla-1171-3Document3 pagesJ. Clin. Microbiol.-1984-Schalla-1171-3Dina Saad EskandereNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Immature Platelet Fraction As An Indicator ofDocument6 pagesEvaluation of The Immature Platelet Fraction As An Indicator ofTuan NguyenNo ratings yet

- RI, Hema&immnoDocument9 pagesRI, Hema&immnoHabtamu WondifrawNo ratings yet

- Tiwari, 2017. RPR in Comparison With ImmunochromatographicDocument5 pagesTiwari, 2017. RPR in Comparison With ImmunochromatographicRima Carolina Bahsas ZakyNo ratings yet

- PCR IT RatioDocument5 pagesPCR IT RatioAgus WijayaNo ratings yet

- Alphafetoprotein: An Obituary: EditorialDocument3 pagesAlphafetoprotein: An Obituary: EditorialRaphael Moro Villas BoasNo ratings yet

- Review: ABO-identical Versus Nonidentical Platelet Transfusion: A Systematic ReviewDocument12 pagesReview: ABO-identical Versus Nonidentical Platelet Transfusion: A Systematic Reviewmy accountNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical Microbiology-1999-Schröter-233.fullDocument2 pagesJournal of Clinical Microbiology-1999-Schröter-233.fullFaisal JamshedNo ratings yet

- Artigo 02 Geneexpert TBDocument4 pagesArtigo 02 Geneexpert TBpriscila pimentel martinelliNo ratings yet

- Thrombosis Research: Full Length Article TDocument7 pagesThrombosis Research: Full Length Article TAnonymous 4XKNqMNo ratings yet

- 1 PDFDocument10 pages1 PDFArticle MakaleNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022202X1549092X MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S0022202X1549092X MainKsiaze AniolkaNo ratings yet

- Pleuralfluidbiomarkers: Beyond The Light CriteriaDocument11 pagesPleuralfluidbiomarkers: Beyond The Light CriteriaVijay KumarNo ratings yet

- Jurnal TBDocument9 pagesJurnal TBindra mendilaNo ratings yet

- Random Spot Urine Protein To Creatinine Ratio Is A Reliable Measure of Proteinuria in Lupus Nephritis in KoreansDocument5 pagesRandom Spot Urine Protein To Creatinine Ratio Is A Reliable Measure of Proteinuria in Lupus Nephritis in KoreansRajagopalNo ratings yet

- CDC 99995 DS1Document12 pagesCDC 99995 DS1Tung NguyenNo ratings yet

- Detecting Sars-Cov-2 at Point of Care: Preliminary Data Comparing Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (Lamp) To Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)Document8 pagesDetecting Sars-Cov-2 at Point of Care: Preliminary Data Comparing Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (Lamp) To Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)Prita Amira Windy AsmaraNo ratings yet

- Clinical ResearchDocument13 pagesClinical ResearchkarmilaNo ratings yet

- Yu2017 2Document11 pagesYu2017 2Mikael Reynardi SutantoNo ratings yet

- Pone 0062323Document10 pagesPone 0062323Malik IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Mak Roo 2018Document7 pagesMak Roo 2018my accountNo ratings yet

- Profile of Blood Donors With Serologic Tests Reactive For The Presence of Syphilis in São Paulo, BrazilDocument7 pagesProfile of Blood Donors With Serologic Tests Reactive For The Presence of Syphilis in São Paulo, BrazilPritha BhuwapaksophonNo ratings yet

- Paper Inggris NEWDocument21 pagesPaper Inggris NEWYolanda Edith P. NababanNo ratings yet

- Risk Analysis of Transfusion of Cryoprecipitate Without Consideration of ABO GroupDocument6 pagesRisk Analysis of Transfusion of Cryoprecipitate Without Consideration of ABO Groupmy accountNo ratings yet

- Int J Lab Hematology - 2022 - Marinov - Validation of A Single Tube 3 Colour Immature Red Blood Cell Screening Assay ForDocument7 pagesInt J Lab Hematology - 2022 - Marinov - Validation of A Single Tube 3 Colour Immature Red Blood Cell Screening Assay ForMaria SousaNo ratings yet

- The Appropriate Use of Testing For COVID-19Document4 pagesThe Appropriate Use of Testing For COVID-19newazNo ratings yet

- 1 12 Nucleic Acid Testing To Detect HBV in Blood Donors 2011Document12 pages1 12 Nucleic Acid Testing To Detect HBV in Blood Donors 2011Putri Kusuma WardaniNo ratings yet

- Kim 2020Document8 pagesKim 2020Zied FehriNo ratings yet

- 2014.factor VIII (BAY 94-9027) For Haemophilia ADocument8 pages2014.factor VIII (BAY 94-9027) For Haemophilia AVivianMagnaniLucasNo ratings yet

- Management of Blood Donors and Blood Donations From Individuals Found To Have A Positive Direct Antiglobulin TestDocument11 pagesManagement of Blood Donors and Blood Donations From Individuals Found To Have A Positive Direct Antiglobulin TestLuis Enrique Tinoco JuradoNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Assessment of Hematopoietic Chimerism After Bone MarrowDocument9 pagesQuantitative Assessment of Hematopoietic Chimerism After Bone MarrowDaoud IssaNo ratings yet

- Anti HCVDocument5 pagesAnti HCVFaisal JamshedNo ratings yet

- Advice - RAG - Interpretation PCRDocument5 pagesAdvice - RAG - Interpretation PCRHitesh MutrejaNo ratings yet

- Blood Donor Screening For Hepatitis E Virus in The European UnionDocument25 pagesBlood Donor Screening For Hepatitis E Virus in The European UnionRujukan nasionalNo ratings yet

- Presence and Short-Term Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 (Ocak 2021)Document12 pagesPresence and Short-Term Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 (Ocak 2021)azizk83No ratings yet

- Presence and Short-Term Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 (Ocak 2021)Document12 pagesPresence and Short-Term Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 (Ocak 2021)azizk83No ratings yet

- Flow Cytometric Analysis of Normal and Reactive SpleenDocument10 pagesFlow Cytometric Analysis of Normal and Reactive SpleenmisterxNo ratings yet

- Jayaram 2021Document5 pagesJayaram 2021Tuan NguyenNo ratings yet

- Early Syphilis: Serological Treatment Response To Doxycycline/tetracycline Versus Benzathine PenicillinDocument5 pagesEarly Syphilis: Serological Treatment Response To Doxycycline/tetracycline Versus Benzathine PenicillinAnnette CraigNo ratings yet

- Art:10.1186/1471 2431 9 5Document8 pagesArt:10.1186/1471 2431 9 5Pavan MulgundNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Anti JamurDocument4 pagesJurnal Anti JamurYusvinaNo ratings yet

- Anae 14636Document9 pagesAnae 14636anirban boseNo ratings yet

- A Novel Multiplex Real-Time PCR Assay For The Detection of CMV, EBV, HSVDocument8 pagesA Novel Multiplex Real-Time PCR Assay For The Detection of CMV, EBV, HSVV K kasaragodNo ratings yet

- Clinical Epidemiology SGD 1Document6 pagesClinical Epidemiology SGD 1Beatrice Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Neutrophil CD64 Expression, Manual Myeloid Immaturity Counts, and Automated Hematology Analyzer Fla...Document12 pagesComparison of Neutrophil CD64 Expression, Manual Myeloid Immaturity Counts, and Automated Hematology Analyzer Fla...Reyhan IsmNo ratings yet

- Performance of Treponemal Tests For The Diagnosis of SyphilisDocument13 pagesPerformance of Treponemal Tests For The Diagnosis of SyphilisdrirrazabalNo ratings yet

- Blood Donation and SafetyDocument24 pagesBlood Donation and SafetyVietNo ratings yet

- Chronic Allograft Nephropathy Score Before Sirolimus Rescue Predicts Allograft Function in Renal Transplant PatientsDocument10 pagesChronic Allograft Nephropathy Score Before Sirolimus Rescue Predicts Allograft Function in Renal Transplant PatientsDr. Antik BoseNo ratings yet

- Antiphospholipid Syndrome Challenges in The Laboratory Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument61 pagesAntiphospholipid Syndrome Challenges in The Laboratory Diagnosis and Treatmentbadshah007777No ratings yet

- compatibility testing pretransfusion testing:: Assigment .2 BLOOD BANK نايلع وبا يريخ داهج/ مسلاا 20162109Document6 pagescompatibility testing pretransfusion testing:: Assigment .2 BLOOD BANK نايلع وبا يريخ داهج/ مسلاا 20162109Dr. Jihad KhairyNo ratings yet

- Complementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 17: OncologyFrom EverandComplementary and Alternative Medical Lab Testing Part 17: OncologyNo ratings yet

- Respiratory SystemDocument36 pagesRespiratory SystemPritha Bhuwapaksophon100% (1)

- Viral Infection of The Respiratory TractDocument29 pagesViral Infection of The Respiratory TractPritha BhuwapaksophonNo ratings yet

- Novel Roles For Factor XII-driven Plasma Contact Activation SystemDocument6 pagesNovel Roles For Factor XII-driven Plasma Contact Activation SystemPritha BhuwapaksophonNo ratings yet

- Respiratory Tract InfectionsDocument31 pagesRespiratory Tract InfectionsPritha BhuwapaksophonNo ratings yet

- Emerging Infectious Disease Agents and Their Potential Threat To Transfusion Safety.Document29 pagesEmerging Infectious Disease Agents and Their Potential Threat To Transfusion Safety.Pritha BhuwapaksophonNo ratings yet

- Blood Surveillance and Detection On Platelet Bacterial Contamination Associated With Septic Events.Document7 pagesBlood Surveillance and Detection On Platelet Bacterial Contamination Associated With Septic Events.Pritha BhuwapaksophonNo ratings yet

- Immunological Properties of Trehalose Dimycolate (Cord Factor) and Other Mycolic Acid-Containing Glycolipids - A ReviewDocument11 pagesImmunological Properties of Trehalose Dimycolate (Cord Factor) and Other Mycolic Acid-Containing Glycolipids - A ReviewPritha BhuwapaksophonNo ratings yet

- Facing The Crisis - Improving The Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in The HIV EraDocument13 pagesFacing The Crisis - Improving The Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in The HIV EraPritha BhuwapaksophonNo ratings yet

- The Cell Surface Receptor DC-SIGN Discriminates Between Mycobacterium Species Through Selective Recognition of The Mannose Caps On LipoarabinomannanDocument4 pagesThe Cell Surface Receptor DC-SIGN Discriminates Between Mycobacterium Species Through Selective Recognition of The Mannose Caps On LipoarabinomannanPritha BhuwapaksophonNo ratings yet

- Clinical Utility of Multiparameter Flow Cytometry in The Diagnosis of 1013 Patients With Suspected Myelodysplastic SyndromeDocument15 pagesClinical Utility of Multiparameter Flow Cytometry in The Diagnosis of 1013 Patients With Suspected Myelodysplastic SyndromePritha BhuwapaksophonNo ratings yet

- Alteration in Reproductive HealthDocument139 pagesAlteration in Reproductive HealthNylia Ollirb AdenipNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study of MiasmsDocument83 pagesComparative Study of MiasmsFawad KhanNo ratings yet

- Gynecologic NursingDocument218 pagesGynecologic Nursingblacklilha100% (1)

- VDRL Test and Its InterpretationDocument11 pagesVDRL Test and Its InterpretationSauZen SalaZarNo ratings yet

- The Immune Response To Infection With Treponema Pallidum, The Stealth PathogenDocument8 pagesThe Immune Response To Infection With Treponema Pallidum, The Stealth Pathogenhazem alzedNo ratings yet

- Country Progress Report On: Hiv/AidsDocument45 pagesCountry Progress Report On: Hiv/AidsDineish MurugaiahNo ratings yet

- Syndrome: The Battered-ChildDocument8 pagesSyndrome: The Battered-ChildHARITHA H.PNo ratings yet

- Sahagon Hanna Final Paper Congenital Syphilis Order SetDocument13 pagesSahagon Hanna Final Paper Congenital Syphilis Order Setapi-648597244No ratings yet

- Written Report: Sexually Transmitted Infections (Stis)Document3 pagesWritten Report: Sexually Transmitted Infections (Stis)Paul Michael B. VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Bact Micro D&R AgamDocument124 pagesBact Micro D&R AgamS Balagopal Sivaprakasam100% (1)

- Microbial Diseases of The Urinary and Reproductive SystemsDocument139 pagesMicrobial Diseases of The Urinary and Reproductive Systemsone_nd_onlyuNo ratings yet

- Syphilis: Castro, Khristine Marie Laudencia BSNDocument8 pagesSyphilis: Castro, Khristine Marie Laudencia BSNPlan Can JoxNo ratings yet

- Mu CosaDocument222 pagesMu CosaAliImadAlKhasakiNo ratings yet

- Immunofluorescence Tests: Direct and IndirectDocument489 pagesImmunofluorescence Tests: Direct and IndirectmeskiNo ratings yet

- STDDocument69 pagesSTDPatrick DycocoNo ratings yet

- 10.0 Reproductive SystemDocument64 pages10.0 Reproductive SystemMichelle GalvanNo ratings yet

- Diagnosa Dan Kode Icd-10 Beserta Terjemahan Bahasa Indonesia Penyakit Karna BakteriDocument216 pagesDiagnosa Dan Kode Icd-10 Beserta Terjemahan Bahasa Indonesia Penyakit Karna BakteripiterNo ratings yet

- Seminar On Preventive ObstetricsDocument49 pagesSeminar On Preventive ObstetricsRini Robert100% (3)

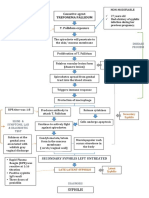

- Path o Physiology of SyphilisDocument1 pagePath o Physiology of Syphilis3S - JOCSON, DENESE NICOLE LEE M.No ratings yet

- WHO HTS Guidelines - Presentation Part 1: Who HTS: HTS Info On The Go: WHO HTS Data DashboardsDocument39 pagesWHO HTS Guidelines - Presentation Part 1: Who HTS: HTS Info On The Go: WHO HTS Data DashboardsBajram OsmaniNo ratings yet

- IuijjDocument15 pagesIuijjMarvin BundoNo ratings yet

- Botany AssignmentDocument21 pagesBotany Assignmentabdul hadiNo ratings yet

- Syphilis SlidesDocument35 pagesSyphilis SlidesBella Anggraeni LoaloaNo ratings yet

- PDF Lissa A Story About Medical Promise Friendship and Revolution Ethnographic Sherine Hamdy Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Lissa A Story About Medical Promise Friendship and Revolution Ethnographic Sherine Hamdy Ebook Full Chapterlynda.tallant662100% (3)

- Straight Talk, April 2010Document4 pagesStraight Talk, April 2010Straight Talk FoundationNo ratings yet

- Malaysian Guidelines Management of STIs 5th. Edition 2024Document136 pagesMalaysian Guidelines Management of STIs 5th. Edition 2024shafiqsulaiman2191No ratings yet

- Communicable Disease Nursing Test BankDocument11 pagesCommunicable Disease Nursing Test Bankdomingoramos685No ratings yet

- The Great Imitator A Rare Case of Lues Maligna in An Hiv Positive Patient 4Document4 pagesThe Great Imitator A Rare Case of Lues Maligna in An Hiv Positive Patient 4Talaat OmranNo ratings yet

- Signs NotesDocument22 pagesSigns NotesVaidehi guptaNo ratings yet

- Global Progress Report On HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2021Document108 pagesGlobal Progress Report On HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections, 2021Tugasbu CicikNo ratings yet